Abstract

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of cell surface receptors. Class B1 GPCRs constitute a subfamily of 15 receptors that characteristically contain large extracellular domains (ECDs) and respond to long polypeptide hormones. Class B1 GPCRs are critical regulators of homeostasis, and, as such, many are important drug targets. While most transmembrane proteins, including GPCRs, are recalcitrant to crystallization, recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have facilitated a rapid expansion of the structural understanding of membrane proteins. As a testament to this success, structures for all the class B1 receptors bound to G proteins have been determined by cryo-EM in the past 5 years. Further advances in cryo-EM have uncovered dynamics of these receptors, ligands, and signaling partners. Here, we examine the recent structural underpinnings of the class B1 GPCRs with an emphasis on structure–function relationships.

Keywords: GPCR, G protein, Class B1, cryo-EM, peptides, dynamics

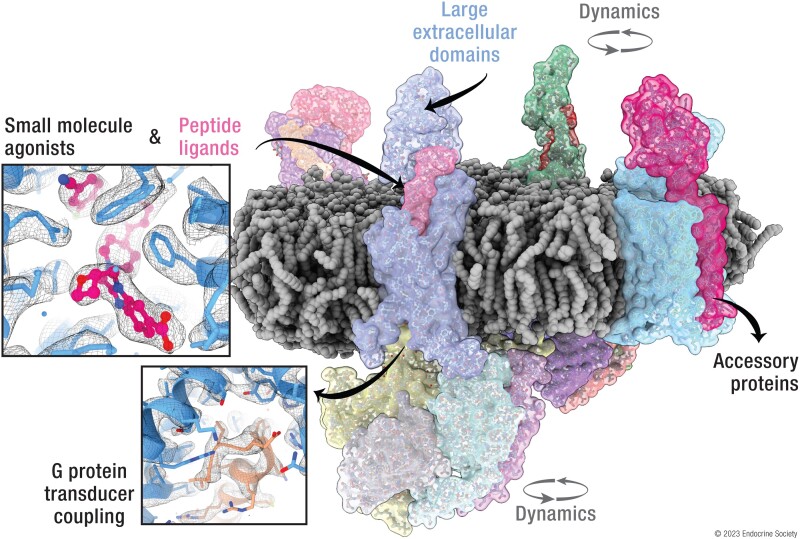

Graphical Abstract

Essential points.

Structures of all 15 members of the class B1 G protein–coupled receptor family have been solved by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) in the presence of G protein and an orthosteric peptide agonist

Cryo-EM reveals the structural basis for receptor activity-modifying protein–mediated alterations to ligand activities at the calcitonin family receptors

Receptor and peptide dynamics reveal insights into activation mechanisms

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are proteins that serve to transmit information from the outside to the inside of cells. This information transfer can result from diverse chemical and physical stimuli, including proteins, peptides, small molecules, light, or mechanical stress (1, 2), and these stimuli interact with receptors to promote conformational changes that are registered by intracellular partners. Due to their ubiquity in human tissues and their involvement in a broad range of physiological processes in the human body, GPCRs are popular targets for drug discovery, with one-third of the drugs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration targeting GPCRs (3).

GPCRs are named for their interactions with heterotrimeric G proteins, and G proteins are named for their dependence on guanine nucleotides. GPCRs signal by catalyzing the exchange of guanine diphosphate (GDP) for guanine triphosphate (GTP), leading to G protein dissociation and activation. Gα subunits possess intrinsic GTPase activity that hydrolyzes GTP to GDP terminating signaling. Subsequent to G protein recruitment, phosphorylation of the C-terminus of receptors by GPCR kinases and recruitment of β-arrestins may occur, which can lead to desensitization, internalization of the receptor, or further independent signaling outcomes (4).

Human GPCRs, of which ∼800 exist, can be categorized into 5 families: class A (Rhodopsin), class B (B1, Secretin; B2, Adhesion), class C (Glutamate), and class F (Frizzled) (5). Class B1 GPCRs (also referred to as the secretin family) comprise a relatively small group of receptors that contain moderately large extracellular domains (ECDs) of ~120 residues, heptahelical transmembrane domain (TMD) sections of ~260 residues, and C-terminal, intracellular sections of ~70 residues (6). Like other GPCRs, class B1 receptors contain 3 extracellular loops (ECLs) and 3 intracellular loops (ICLs) linking the transmembrane helices (TMs) (7). Characteristically, long polypeptide hormones activate class B1 GPCRs, and each receptor has at least 1 known endogenous agonist (ie, there are no orphaned class B1 receptors) (5).

Fifteen members of the class B1 family have been identified in humans, with high sequence homology across vertebrate species, including basal vertebrates such as hagfish and lamprey (8). Homologs of vertebrate class B1 GPCR genes are also found among invertebrate genomes, including in Caenorhabditis elegans and in Drosophila melanogaster, but the role of these and their relation to human B1 GPCR genes remains poorly understood (9). Five clusters of B1 homologs have been identified across nematode and arthropod genomes, with distinct homology between certain clusters and human homologs (eg, diuretic hormone 31 receptor [DH31-R]/Heliothis ecdysone receptor [Hec-R] cluster, and human calcitonin receptor [CTR] family) (10). These findings, along with the discovery of adhesion-like GPCRs in sea anemone (cnidarian) genomes, has led to the hypothesis that the B1 family descended from a common, adhesion-class, GPCR ancestor (11).

Among the canonical isoforms, human class B1 receptors average ~470 residues in length and range from ~47 to ~66 kDa in mass, discounting post-translational modifications (6). Several receptors, including pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide 1 receptor (PAC1R), corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRF1R), and CTR, have known alternative RNA splice isoforms, and these isoforms can have altered G protein coupling compared with canonical isoforms (12–16). Genes encoding class B1 GPCRs are not localized to any particular region in the human genome; however one-third are found on chromosome 7 (6, 17).

Class B1 GPCRs are targeted clinically for a wide range of diseases including diabetes (glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor [GLP-1R] and amylin receptors [AMYRs] (18, 19)), cardiovascular complications (GLP-1R (20)), obesity (GLP-1R and gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor [GIPR] (21)), migraine headaches (calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor [CGRPR] (22)), hypoglycemia (glucagon receptor [GCGR) (23]), osteoporosis (parathyroid hormone 1 receptor [PTH1R] (24)), and short bowel syndrome (glucagon-like peptide-2 receptor [GLP-2R] (25)). Beyond approved therapeutics, PAC1R is implicated in migraine and post-traumatic stress disorder (26) and the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptors 1 and 2 (VPAC1R, VPAC2R) are involved in inflammation (27). Parathyroid hormone 2 receptor (PTH2R) is implicated in nociception and fear response (28, 29), and the corticotropin receptors (CRF1R and CRF2R) are implicated in stress responses (30, 31). Due to their broad physiological and clinical relevance, understanding the structural underpinnings of ligand binding and receptor activation of class B1 family members is of prime interest.

Prior to 2013, high-resolution structural information on class B1 GPCRs was limited to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and x-ray crystal structures of isolated ECDs due to the lower tractability of full-length receptors (32, 33). Alone, class B1 ECDs can be induced to fold properly, are soluble, and are still competent to bind cognate hormones, albeit with decreased affinity compared with full-length receptors (34). The first crystal structure of a class B1 GPCR extracellular domain (ECD), the complex of the GIPR ECD with GIP, was reported in 2007 (33). At present, there are NMR or x-ray structures of isolated ECDs for two-thirds of the class B1 receptors (32, 35–48). These studies of isolated ECDs revealed a common fold of an N-terminal alpha helix, followed by antiparallel beta sheets with 3 conserved disulfide bonds yielding a groove-like scaffold for the C-terminus of the peptide to engage (reviewed in reference (49)).

Contemporaneous with the first ECD structures of class B1 GPCRs, seminal work from the groups of Kobilka and Stevens provided the foundation for crystallographic characterization of full-length, nonvisual system, human GPCRs (44, 50). Following in 2013, the first structures containing class B1 transmembrane domains were reported bound to nonpeptide antagonists: those of the GCGR (51) and the CRF1R (52). While these structures represented key contributions to the field, the determination of membrane proteins by crystallography is technically challenging and tedious, and, not surprisingly, the field progressed slowly until 2017.

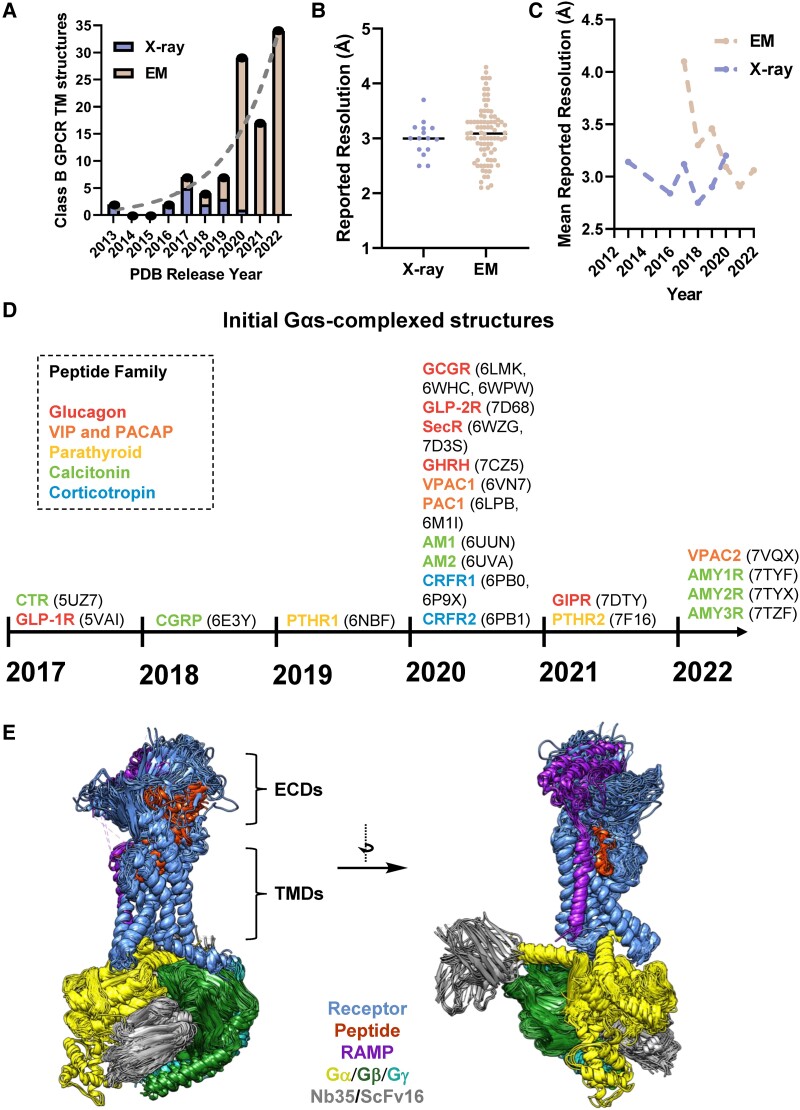

Single particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has revolutionized membrane protein structural biology (53, 54). Since 2017, cryo-EM has led to a rapid expansion in the number of available GPCR structures and largely supplanted crystallography for the determination of class B1 GPCRs (Fig. 1A). Cryo-EM does not require growth of protein crystals, which is usually challenging and can require extensive protein engineering (55). Furthermore, only small quantities (micrograms) of protein are necessary for cryo-EM, crystal-packing artifacts are not present, and some sample heterogeneity can be tolerated (56). While early reports of cryo-EM structures were generally of poor resolution compared with those determined by x-ray crystallography, parity in resolution has been achieved (Fig. 1B and 1C). More recently, resolutions by cryo-EM can achieve true atomic resolution for rigid proteins (57, 58), sub-2 Å for GPCR complexes (59), and can regularly surpass the best achieved by crystallography in practice (60).

Figure 1.

Timeline of structure determination of transmembrane domain (TMD)–containing class B1 GPCRs. (A) The number of structures containing class B1 GPCR TMs deposited in the protein data bank (PDB) each year from 2013 to October 2022. The dashed line is an exponential fit to guide the eye. (B) Reported resolutions for class B1 GPCR TM containing structures. (C) Mean reported resolutions for class B1 GPCR TM structures vs time. (D) A timeline of the first reported structures of full-length class B1 GPCRs bound to Gαs. PDB IDs for representative structures are listed. If multiple structures were released in the same year, a representative PDB from each publication is listed. Receptors have been grouped by color for subclades within the peptide/receptor family. (E) An alignment of structures from the class B1 family bound to orthosteric peptide agonists and G proteins displayed in ribbon format. Individual proteins within complexes are colored according to the key.

Purified active, agonist-bound, GPCR–transducer complexes, particularly G proteins, are currently the most tractable states for structure determination by cryo-EM. A general procedure involves coexpression of receptor and G proteins in insect cells, solubilization of membrane proteins in lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol containing detergent micelles (61), enrichment of the receptor using affinity capture, and purification by size exclusion chromatography (62). Microliter quantities of protein solution at ~1 to 10 mg/mL are applied to a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grid, and the sample is blotted and rapidly frozen in a cryogen to produce vitreous ice. TEM micrographs are collected of the protein particles embedded in thin layers of vitreous ice, and images of the particles can be aligned in silico to reconstruct 3D density maps. Despite their small size, lack of symmetry, and tendency for preferred particle orientations with respect to the TEM grid (all of which can impede cryo-EM reconstructions), structures of GPCRs bound to G proteins can be readily determined to high resolutions (<3 Å) (60): even when using microscopes operating at lower voltage (200 kV) (42, 63–65).

As of 2022, all 15 human class B1 receptors coupled to the heterotrimeric Gs protein have been solved by cryo-EM (Fig. 1D), and more than 100 structures containing TM domains of class B1 receptors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB (66)) (Table 1). As the primary driver of the rapid expanse in structural information, cryo-EM–derived structures are a focus of this review.

Table 1.

List of transmembrane domain–containing class B1 GPCR structures deposited into the protein data bank (PDB) as of June 2022

| Receptor (abbreviation, compositiona) | Structures | Ligands | Highest resolution Å (PDB) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucagon receptor (GCGR) | 4L6Rapo,1, 5EE7a-ant,1 5XEZa-ant,sm,1, 5XF1a-ant,sm,1, 5YQZo-ago,1, 6LMKo-ago 6LMLo-ago, Gi, 6WHCo-ago, 6WPWo-ago, 7V35o-ago | apo, MK-0893, NNC0640, NNC1702, Glucagon, Peptide 15, ZP3780, Peptide 20 | 2.5 (5EE7) | (51, 67–73) |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) | 5NX2o-ago, 5VEWNAM,sm,1, 5VEXNAM,sm,1, 5VAIo-ago, 6B3Jo-ago, 6KJVNAM,sm,1, 6KK1NAM,sm,1, 6KK7NAM,sm,1, 6ORVo-ago,sm, 6LN2NAM,sm,1, 6VCBo-ago,PAM,sm, 6X18o-ago, 6X19o-ago,sm, 6X1Ao-ago,sm, 6XOXo-ago,sm, 7C2Eo-ago,sm, 7LCIo-ago,sm, 7LCJo-ago,sm, 7LCKo-ago,sm, 7E14o-ago,ago-PAM,sm, 7DUQo-ago,ago-PAM,sm, 7DURago-PAM, 7EVMago-PAM, 7KI0o-ago, 7KI1o-ago, 7RTBo-ago, 7S15o-ago,sm, 7S1Mo-ago, 7S3Io-ago, 7LLLo-ago, 7LLYo-ago, 7FIMo-ago, 7VBHo-ago, 7VBIo-ago, 7RG9apo, 7RGPo-ago, 7X8So-ago,sm, 7X8Ro-ago,sm | Peptide 5, PF-06372222, NNC0640, GLP-1, ExP5, TT-OAD2, LSN3160440, CHU-128, PF-06882961, LY3502970 (OWL833), RGT1383, Compound 2, Semaglutide, Taspoglutide, Peptide 19, PF-06883365, Ex4-D-Ala, Ex4, Oxyntomodulin, Tirzepatide, Peptide 20, nonacylated Tirzepatide, WB4-24, Boc5 | 2.1 (6X18, 6X19) | (74–93) |

| Glucagon-like peptide-2 receptor (GLP-2R) | 7D86o-ago | GLP-2 | 3 (7D68) | (94) |

| Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor (GIPR) | 7DTYo-ago, 7FINo-ago, 7FIYo-ago, 7VABo-ago, 7RA3o-ago, 7RBTo-ago | GIP (1-42), Peptide 20, Tirzepatide, nonacylated Tirzepatide | 3 (7DTY) | (71, 87, 95) |

| Secretin receptor | 6WI9o-ago, 6WZGo-ago, 7D3So-ago | Secretin | 2.3 (6WZG) | (96, 97) |

| Growth hormone–releasing hormone receptor (GHRHR) | 7CZ5o-ago, 7V9Mo-ago, 7V9Lapo | apo, Growth hormone–releasing hormone | 2.6 (7CZ5, 7V9L) | (98, 99) |

| Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor 1 (VPAC1) | 6VN7o-ago | PACAP27 | 3.2 (6VN7) | (100) |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 (VPAC2) | 7VQXo-ago, 7WBJo-ago | PACAP27 | 3.4 (7WBJ) | (101) |

| Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide type 1 receptor (PAC1R) | 6LPBo-ago, 6M1Ho-ago, 6M1Io-ago, 6P9Yo-ago | PACAP38, Maxadilan | 3.0 (6P9Y) | (102–104) |

| Parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor (PTH1R) | 6FJ3o-ago,1, 6NBFo-ago, 6NBHo-ago, 6NBIo-ago, 7VVJo-ago, 7VVKo-ago, 7VVLo-ago, 7VVMo-ago, 7VVNo-ago, 7VVOo-ago, | ePTH, LA-PTH, PTHrP, PTH | 2.5 (6FJ3) | (105–107) |

| Parathyroid hormone 2 receptor (PTH2R) | 7F16o-ago | TIP39 | 2.8 (7F16) | (108) |

| Calcitonin receptor (CTR) | 5UZ7o-ago, 6NIYo-ago, 7TYLo-ago, 7TYIo-ago, 7TYNo-ago, 7TYOo-ago | Salmon calcitonin, Rat amylin, Human calcitonin | 2.6 (7TYN) | (62, 64, 109) |

| Amylin 1 receptor (AMY1R, CTR + RAMP1) | 7TYFo-ago, 7TYWo-ago | Rat amylin, Salmon calcitonin | 2.2 (7TYF) | (64) |

| Amylin 2 receptor (AMY2R, CTR + RAMP2) | 7TYHo-ago, 7TYXo-ago, 7TYYo-ago | Human calcitonin, Rat amylin, Salmon calcitonin | 2.6 (7TYX) | (64) |

| Amylin 3 receptor (AMY3R, CTR + RAMP3) | 7TZFo-ago | Rat amylin | 2.4 (7TZF) | (64) |

| Calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR) | N/A* | N/A* | N/A* | N/A* |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRP, CLR + RAMP1) | 6E3Yo-ago, 7KNTapo, 7KNUo-ago,1 | apo, Calcitonin gene-related peptide 1 | 3.2 (7KNT) | (110, 111) |

| Adrenomedullin 1 receptor (AM1, CLR + RAMP2) | 6UUNo-ago | Adrenomedullin | 3 (6UUN) | (112) |

| Adrenomedullin 2 receptor (AM2, CLR + RAMP3) | 6UUSo-ago, 6UVAo-ago | Adrenomedullin, Adrenomedullin 2 | 2.3 (6UVA) | (112) |

| Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 (CRF1R) | 4K5YNAM,1, 4Z9GNAM,1, 6P9Xo-ago, 6PB0o-ago | CP-376395, Corticotropin releasing factor, Urocortin-1 | 2.9 (6P9X) | (52, 103, 113, 114) |

| Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 (CRF2R) | 6PB1o-ago | Urocortin-1 | 2.8 (6PB1) | (114) |

N/A indicates not applicable as CLR does not traffic effectively as a monomer. Apo indicates no modulator or inhibitor ligand bound. O-ago indicates orthosteric agonist. sm indicates small-molecule modulator or inhibitor ligand bound. 1 indicates receptor not bound to G protein. Gi indicates receptor bound to Gαi. NAM indicates negative allosteric modulator bound. PAM indicates positive allosteric modulator bound. Ago-PAM indicates agonist/positive allosteric modulator bound.

Composition indicates 7-transmembrane protein and receptor activity-modifying protein (RAMP) heterodimer, if relevant. *CLR does not traffic efficiently to the cell surface in the absence of a RAMP (115).

Conserved/Distinct Motifs and Interactions

Extracellular Domains

One of the most distinguishing features of class B1 GPCRs is the presence of a moderately large ECD, also referred to as the N-terminal domain. N-linked glycosylation sites in the ECD regulate receptor trafficking and ligand binding (116–119).

The ECD primarily serves to enhance the affinity of peptide agonists and to promote selectivity among paralogous hormones (120–122). However for some receptors (including the GLP-1R and GCGR), ECD removal abolishes signal transduction, even in the presence of a covalently bound agonist (123). In the case of the GLP-1R, loss of signaling from an ECD-truncated construct can be rescued by the ECD acting in trans (124). These observations suggest that certain ECDs also play an intrinsic role in facilitating the conformational changes in the TM bundle that are sensed by intracellular effector proteins. Despite this, cryo-EM structures of the GLP-1R and GCGR show relatively limited contact between the ECD and the TMD, with predominant interactions occurring between the ECD and ECL1, and it is unclear how the ECD functions as a necessary component for activation. Other receptors, including PTH1R, PAC1R, and CRF1R, can function without their respective ECDs (123), though ECD-truncated receptor constructs typically bind full-length peptide ligands with lower affinity than wild-type receptors due the loss of interaction surface (125, 126). Furthermore, studies with the PTH1R (127) suggest that ECD binding preorganizes the hormone N-terminus to engage the TMD (128).

ECDs are tethered to the first transmembrane helix by a short polypeptide sequence known as the stalk, which differs in structure among class B1 receptors. Consequently, in agonist bound receptors, the ECDs do not adopt a common conformation relative to the receptor TMD (Fig. 1D). Agonist-dependent differences in the ECD/TMD configuration at individual receptors have been observed (102), particularly in the case of the GLP-1R (74–76), suggesting that agonists play a key role in the positioning the ECD, and vice versa. Indeed, ligand induced changes to the ECD conformation relative to the cellular membrane can be detected in cells by resonance energy transfer experiments (129).

While the structure of each class B1 GPCR has been determined in the presence of a peptide agonist, there are relatively few structures of class B1 GPCRs without bound orthosteric ligands, so the conformational landscape of the ECDs in the apo receptor form remains poorly understood. In a crystal structure of the GLP-1R, the ECD packs against the transmembrane domain (77); however, the receptor structure was determined in the presence of a Fab fragment bound to the ECD. In contrast, the ECD is completely unresolved in an unliganded, cryo-EM structure of a constitutively active, transducer-bound GHRH receptor (98), suggesting that the ECD is particularly mobile in absence of a ligand, at least in the activated G protein–bound state. Even when bound by full length peptides, the ECD is typically less well resolved compared with the TMD and G protein, suggesting relatively high flexibility/conformational dynamics, relative to the TMD core. High mobility for the ECD in both peptide bound and unliganded forms is also supported by molecular dynamics simulations (96, 127, 130, 131).

Conserved Residues and Features

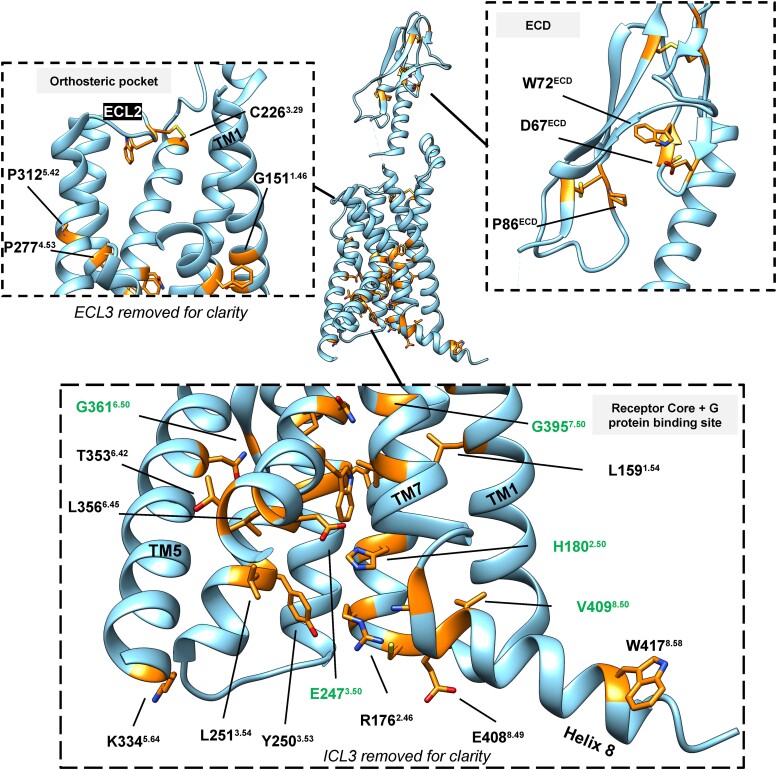

Despite the relatively small number of class B1 receptors, the conspicuous absence of conserved residues in the ligand binding pocket reflects the diversity of ligands to which these receptors bind. Discounting the conserved pairs of disulfide-bonded cysteine residues on the extracellular side, most of the conserved residues among human class B1 GPCRs are found in the receptor core and near the base of the receptor at the G protein binding interface (Fig. 2). To more easily compare conserved residues across receptors, the Wootten numbering system was established (132), which uses 2 values to indicate the transmembrane helix and position relative to a conserved residue (eg, G6.50). This numbering system is similar to the class A Ballesteros–Weinstein numbering system (133, 134), and is used throughout this review. The first digit indicates the helix number, and the second number indicates the position relative to the most highly conserved residue of that secondary structure (eg, for G6.50, transmembrane helix 6 and .50 is the most conserved residue). Generic residue numberings tables, including Wootten numbering, are available in the GPCRdb (135).

Figure 2.

Conserved residues among human class B1 GPCRs mapped onto a high-resolution EM structure of GLP-1R bound to GLP-1 and Gαs (PDB: 6X18). The carbon backbones of conserved residues are colored orange and shown as “sticks.” Superscript numbers are from the Wootten et al, class B1 GPCR numbering scheme (132), with residues at “x.50” labeled in green.

The most salient feature of activated class B1 receptors is a large outward movement of TM6 relative to inactive receptors which is associated with a substantial kink in the center of TM6 that exposes an intracellular pocket enabling binding of the Gα C-terminal helix. Class A receptors also exhibit outward TM6 movement accompanying receptor activation but with a smaller translation than Class B1 receptors (62, 78). Agonist-bound GPCRs can show small or transient displacements in TM6, relative to inactive state structures (76, 110); however, a large outward movement of TM6 is only apparent in structures with G proteins bound. This is reflected in biophysical studies of exemplar GPCRs, for instance, the fully active conformation of the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) is only evident when both an agonist and a coupling partner (G protein or nanobody G protein mimic) are bound (136, 137). These observations support the hypothesis that agonists shift the receptor's conformational ensemble toward states that favor G protein coupling, but agonists alone do not stabilize the fully outward TM6 conformations, with the fully active state requiring transducer binding. Indeed, recent spectroscopic evidence suggests that the TM6 kink for the GCGR does not form in the presence of an agonist alone; interestingly, however, once formed by agonist and G protein, the GCGR TM6 kink persists for an extended period of time after G protein dissociation, contrasting to the behavior of the prototypical class A β2AR (67). Collectively, this suggests that the activation barrier for the TM6 transition in class B1 GPCRs is larger relative to class A GPCRs.

The TM6 kink is facilitated by the P6.47xxG6.50 motif (138), which is conserved among all human class B1 receptors (apart from the PTH2R where P6.47 is replaced by a leucine residue). The residues of the P6.47xxG6.50 motif adopt a helix-like conformation in inactive structures, but in G protein–bound structures, G6.50 displays positive φ angles that helps rationalize the strong conservation for a flexible glycine at this position (139, 140). Not surprisingly, mutation of G6.50 to alanine has been shown to help thermostabilize the GLP-1R (76), and a cysteine residue replacing G6.50 to form an artificial disulfide bridge with TM5 was used to crystalize the GLP-1R (77). Highlighting the importance of P6.47, mutations to alanine at this position in the VPAC1R, CTR, and calcitonin receptor–like receptor (CLR) can also influence receptor activity (141–143).

One of the conserved motifs in both sequence and structure is the GW4.50GxP sequence in TM4. The tryptophan residue of this motif forms T-shaped aromatic interactions with the conserved tryptophan of the adjacent TM3 (W3.46). These tryptophan residues do not make direct contacts with the G protein or ligand, and there is little conformation change between agonist-bound and antagonist-bound structures (68–70, 144), suggesting that this motif supports structural stability. The indole sidechain of W4.50 faces the membrane and has been observed to recruit sterols in several structures (79, 100, 105), a feature shared by W4.50 of class A GPCRs, including the β2AR (145).

Not exclusive to class B1 GPCRs (146), the intracellular, C-terminal tail most proximal to the receptor core forms a short structured element referred to as helix-8 (H8). H8 is positioned against the intracellular face of the membrane; its axis is approximately perpendicular to the 7 transmembrane helices. In Gs bound structures, H8 is topologically similar among all members of the class B1 family. In humans, several residues are conserved in H8 (147), including a N7.61xEV8.50 sequence near the H8 N-terminus that is proximal to the G protein binding site. Additionally, the sidechain of a conserved tryptophan near the helix C-terminus inserts into detergent micelles in cryo-EM structures, suggesting that this residue aids in anchoring H8 to the membrane. Replacement of this conserved tryptophan residue within the CGRPR (W3998.58) with polar residues (either threonine or glutamic acid) led to a loss in cell surface expression, consistent with destabilization of the receptor (148).

In reported TM-containing structures, the residues of the cytoplasmic, C-terminal tails beyond H8 are not supported by EM density and are consequently unmodelled, suggesting high flexibility in the region. Despite this disorder, numerous studies have shown that the cytoplasmic tails of class B1 GPCRs are functionally relevant or are sites for post-translation modifications, including forming the primary domain for receptor phosphorylation. In particular, cytoplasmic tails are important for proper receptor trafficking, desensitization, and arrestin recruitment (149–154). Once post-translational modifications are installed or once effector proteins engage, the cytoplasmic tail might become more ordered. For instance, a crystal structure shows the interaction of sorting nexin 27 (SNX27), a protein that regulates trafficking, with an ordered fragment of the PTH1R cytoplasmic tail (155). Further studies are required to fully elucidate the function and structure of class B1 C-terminal tails.

Overview of Peptide Interactions

ECD Interactions

Class B1 GPCRs bind long polypeptide hormones that act as cognate agonists. In all cases, regions near the C-termini of the hormones interact with the receptor's ECD, and regions near N-termini of the hormones interact with the TMD to promote signal transduction. This 2-domain model (156, 157) of peptide recognition is supported by observations that truncation of hormone N-termini leads to peptides that are competent to bind but are not able to fully activate their respective receptors (158–161). Analysis of the kinetics of agonist binding to the full-length PTH1R compared with ECD-truncated constructs also supports the presence of 2 binding sites (162). Exploiting this modularity, N-terminally truncated hormones serve as scaffolds for generating orthosteric inhibitors (163, 164), including clinical candidates (163). Conversely, C-terminally truncated hormones can, in some cases such as the PTH analog M-PTH(1-14), act to selectively bind the receptor's TMD (126, 165, 166).

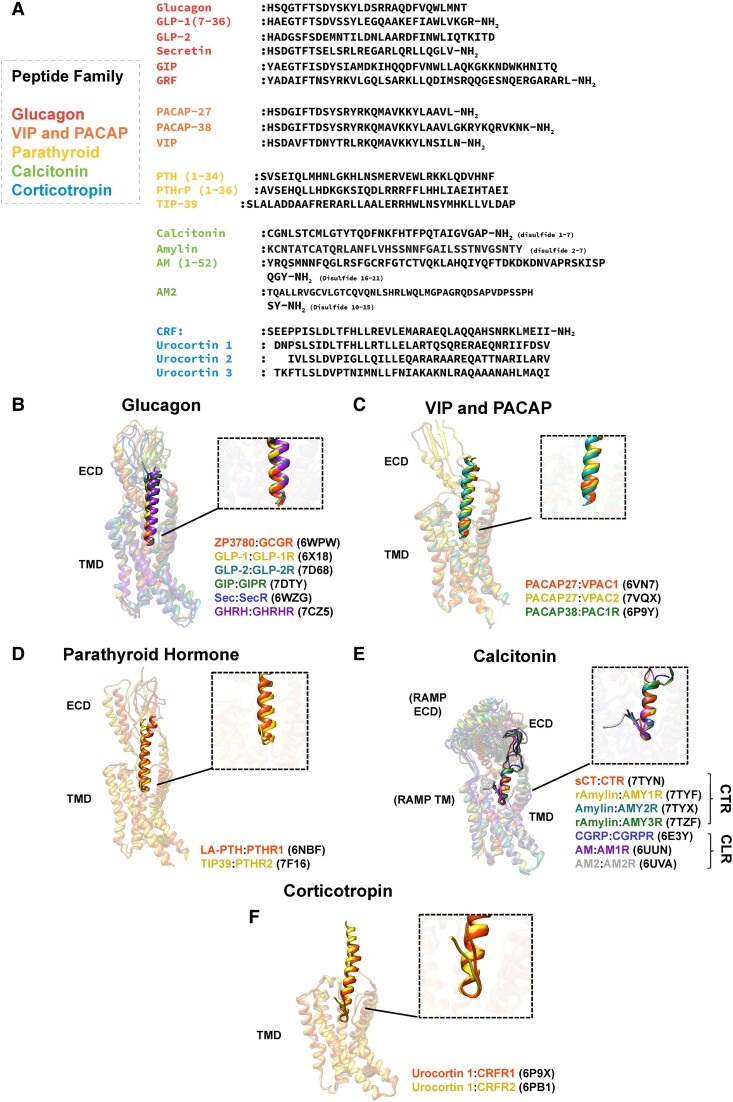

For members of the glucagon, PTH, PACAP/vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and corticotropin families, the peptide hormone C-terminal regions adopt an extended helical conformation to bind a groove in the receptor ECD. For peptides in the former 2 groups, an adjacent pair of structurally conserved hydrophobic residues (either Phe_Val, Phe_Ile, Leu_Leu, Tyr_Leu, or Trp_Leu) facing the peptide/ECD interface contributes markedly to the interaction strength (167–170). Unlike the other families, hormones of the calcitonin family adopt an irregular secondary structure to bind their cognate ECDs. Furthermore, the ECD binding site of calcitonin peptides is distinct from that of other class B1 GPCRs (41, 46).

TMD/Peptide Interactions

The 3 ECLs of class B1 GPCRs, termed ECL 1, 2 and 3 (ECL1, ECL2, and ECL3, respectively) link the transmembrane helices at the extracellular face and form facets of the orthosteric TM-binding pocket. Extensive mutagenesis campaigns across multiple receptors have delineated critical roles of ECLs for binding peptides and for receptor activation (109, 171–178). Among different receptors, ECL1 is the most variable in length, sequence, and structure. The ECL1 for members of the calcitonin receptor family adopts a short helix perpendicular to the TM helices in active structures (64, 111, 112). With the exception of Secretin receptor (96), ECL1 extends well above the TMD of all glucagon receptor family members to engage the bound peptide hormone toward its C-terminus. For the PTH2R, ECL1 is partially unstructured (108), whereas the ECL1 of PTH1R, which is longer than that of most other class B1 GPCRs, is completely unstructured (105) in the available solved structures, although residues of the PTH1R ECL1 are important for activity (179). For structures of the VPAC and PAC subfamily, ECL1 has either been unresolved or only resolved at low resolution, suggesting it has significant flexibility when peptide hormones are bound (100, 103, 104) In some PAC1R structures, ECL1 has been modelled containing a short helix (102). Interestingly, a recent structure of VPAC2R revealed the N-terminal helix 1 of the ECD wedges in between the peptide and ECL1 (101) which is, to date, a unique feature for a class B1 GPCR ECD. Ligand-dependent alterations in the ECL1 have also been observed for the GLP-1R: the agonists semaglutide and taspoglutide, 2 closely related analogs, induce divergent consensus ECL1 conformations and dynamics (80).

ECL 2 contains 2 conserved residues among human class B1 receptors: a tryptophan residue that inserts into the upper cleft between TM3 and TM4 as well as a cysteine residue that is bonded to C3.29. These 2 features rigidify ECL2, and at a backbone level, there is little conformational variability in ECL2 among the class B1 family members when bound to G proteins. It is noteworthy, however, that in the crystal structure of PTH1R absent of G protein, the conserved tryptophan (W352) is swung out of its usual TM3/TM4 pocket to make contact with the peptide ligand (106).

As mentioned above, the N-termini of class B1 hormones are crucial for inducing receptor activation. Indeed, cleavage of the first 2 amino acid residues of glucagon family peptides by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase IV serves as a mechanism of rapid hormone inactivation in serum (180, 181). The α-helical conformation that glucagon and VIP/PACAP family peptides adopt when bound to the ECD extends deep into the TM core. Conversely, peptide agonists of the calcitonin and corticotropin families form a turn motif near the N-terminus (Fig. 3), but nonetheless extend to similar depth in the TM core. Agonists of the 2 PTH receptors can adopt both helical and turn secondary structure elements in the N-terminal region; a long-acting PTH analog (LA-PTH) (182) adopts a helical conformation, whereas the PTH2R specific agonist, TIP39 (183), also contains a turn motif in its N-terminal region (108). The glucagon family peptides, as well as members of the VIP and PACAP family, all contain a critical aromatic residue (either His or Tyr) at the N-terminus. These peptides, as well as those of the PTH family, also share an acidic residue near the N-terminus that makes key electrostatic contacts with a conserved basic residue 2.53 in the core of the receptor, which forms part of what is termed the central polar network (184).

Figure 3.

Class B1 peptide hormone sequences and structure. (A) Sequences of human hormones of class B1 GPCRs. (B,C) Aligned structures of peptides when bound to class B1 GPCRs, displayed in ribbon format and colored according to the displayed keys, of the glucagon (B), VIP and PACAP (C), parathyroid hormone (D), calcitonin (E), and corticotropin (F) families for selected structures. Structure alignments were performed on the receptor residues using UCSF Chimera 1.14.

While all human hormones that serve as class B1 GPCR agonists contain receptor activation domains toward the peptide N-terminus, the peptide maxadilan (185), a potent PAC1R agonist isolated from sand fly saliva, distinctively fails to conform to the trend (102). Maxadilan is a 61 amino acid peptide with 2 antiparallel helices that are linked by a disulfide bond. The distal regions of 2 helices engage the ECD while the core of the peptide, which partially adopts a turn motif, engages the TM bundle to induce receptor activation. Supporting the hypothesis that the central region of maxadilan is important for agonist activity, Hu et al designed potent antagonists of PAC1R based on maxadilan with central residues of the peptide removed (186). The structure including maxadilan demonstrates that potent peptide agonists of class B1 GPCRs can differ markedly from that of their cognate hormones.

G Protein Interactions

The Gα C-terminal polypeptide sequence, termed the alpha-5 helix (α5H), adopts an extended helix terminated by a “hook” conformation to form extensive interactions with the intracellular face of GPCRs (187). As a testament to its large contribution to the affinity between receptor and G protein, the Gαs αH5 peptide alone can bind GPCRs (188, 189). Independent of receptor or agonist, the topology of Gs α5 is well maintained when bound to class B1 GPCRs, and this topology is similar when bound to Gs-coupled class A receptors (190). It is noteworthy, however, that a α5H “hook” conformation is not strictly required for binding as an unusual α5H conformation has been observed when Gs is bound to some class A GPCRs, including the cholecystokinin receptor (59, 191) and the prostaglandin E receptor EP4 (192).

While few structures are of sufficiently high resolution to resolve water molecules, 2.1 Å structures of the GLP-1R (74) reveal a network of rigidly bound waters that support the GPCR-Gα interface. A structural water bridges the interaction between E2473.50 and Y391 of α5. Similar structural waters were placed in high resolution structures of amylin 1 receptor (AMY1R) and GLP-2R (64, 94), suggesting that some structural waters in the G protein binding pocket are topologically conserved across the receptor family.

Though the C-terminal helix of the Gα subunit forms the key contacts with the receptor core, other contacts between the G protein heterotrimer and receptor are noteworthy. One such contact is that of the arginine–arginine stacking that occurs between ICL1 residue and Gβ. In the case of complexes containing GLP-1R and Gβ1 (74), Arg170ICL1 forms counterintuitive guanidine stacking interactions (193) with Arg50 of Gβ. This ICL1 arginine residue is conserved among all human class B1 receptor apart from CLR in which this residue is replaced by a lysine (6). ICL2 residues interact in the section between the αN helix and the β1 loop of Gαs. Though ICL2 is not well conserved among human class B1 receptors, ICL2 mediated contacts are proposed to play an important role in GDP release and consequently G protein activation; hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) studies revealed that the structure of Gαs’ β1 loop, which allosterically affects the GDP-binding P-loop, is perturbed in the presence of the β2AR (194). H8 also contacts Gβ; notably, a positively charged residue in H8, either K8.56 or R8.56, is in proximity with negatively charged residue of Gβ (Asp312 in the case of Gβ1) to form electrostatic interactions. The Gγ subunit is too far from the GPCR to interface directly, barring weak interactions with the receptor's extended cytoplasmic tail that are too transient to be detected by cryo-EM.

Currently unique among the class B1 receptors, both Gs and Gi-bound structures have been determined for the GCGR (69) (albeit using a C-terminally truncated GCGR construct with 3 mutations). Both structures exhibit a similar intracellular binding pocket to accommodate Gs and Gi, apart from some conformational differences in the ICLs that, along with the extent of the interaction interface, may be key factors for G protein selectivity. These structures, combined with mutagenesis studies, provide some unique insights into Gi binding at class B1 GPCRs and a rationale for the generally lower affinity for Gi over Gs. In these structures, the large intracellular binding pocket is able to better accommodate the bulky Gs C terminus over the smaller Gi C terminus (69). Although there are only limited structures of GPCRs solved with more than 1 G protein, to date, the conformation of the receptor bound to the G protein appears to be primarily a property of the agonist-receptor complex, rather than a pocket that is modulated by the interacting G protein.

Caveats and Stabilizing Alterations to G Proteins

It is important to mention the caveat that all the currently published structures of class B1 receptors with G proteins bound have been determined without bound guanine nucleotides (GTP, GDP or mimics), as both GDP and GTP disrupt the stable complexation of GPCRs and G proteins (190), consistent with the role of GPCRs as guanine nucleotide exchange factors. The 2 domains of the G protein, referred to as the Ras-like domain and the alpha-helical domain, sandwich the guanine nucleotide (195). However, in the absence of GDP or GTP (or stabilizing crystal contacts (190, 196)) the alpha helical domain is highly flexible compared with the rest of the complex. With data of sufficient quality, metastable states of the alpha-helical domain can be visualized using classification and local refinement of EM particle images (74, 80, 81). Ligand-dependent alterations to conformation/dynamics of the Gαs alpha-helical domain have been observed in vitro (197, 198) and in cryo-EM (74), suggesting that these alterations may contribute to observed differences in ligand efficacy. Albeit, further work is required to test this hypothesis.

In addition to the lack of bound guanine nucleotides, all class B1 GPCR/G protein complex structures have been determined with stabilizing alterations to the G protein complex such as the use of dominant negative G proteins, including mini-G proteins (199), Nanobit tethering (100), or inclusion a scaffolding protein. The overwhelming majority of these structures include the scaffold protein nanobody 35 (Nb35). Nb35 anchors the Gαs and Gβγ units together and allosterically inhibits association of GTP to Gαs (190, 200). While Nb35 stabilizes the complex and facilitates cryo-EM image alignment, the presence of Nb35 is not necessarily required for high resolution reconstructions (82).

Structural Insights into Class B1 GPCR Biased Agonism

As mentioned above, class B1 GPCRs predominantly couple to Gαs proteins to enhance the production of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). However, GPCRs, including those in the class B1 family, can couple to diverse transducer proteins, such as a wide array of G proteins, kinases, and arrestin proteins (201, 202). These proteins must distinguish an activated receptor from an inactive receptor, but they do not necessary share identical preferences for the conformational spectrum adopted by an activated receptor. Because different agonists can stabilize different receptors conformations, or at least alter the probability of adopting such conformations (203–205), biased signaling can occur. Biased agonists, those that preferentially activate a pathway over another compared with a reference compound, hold the potential for reduced on-target adverse effects for therapeutics: notably, the biased µ-opioid receptor agonist, oliceridine, shows reduced respiratory suppression (206) and is used clinically (207).

The signaling pleiotropy of class B1 GPCRs provides a versatile basis for biased signaling by different agonists. One of the earliest observations of biased agonism was reported for the class B1 GPCR, PAC1R, between the related peptides PACAP-27 and PACAP-38 (208). More recently, biased agonism has been reported for most class B1 GPCRs, including at the GLP-1R (209–219), PTH1R (220–224), GCGR (213), GIPR (213), PACAP, VIP receptors, CTR, AMYRs, CGRPR, and adrenomedullin (AM) receptors (225). These are discussed in further detail in previous review papers (201, 226–228).

While numerous biased agonists have been described, there are only limited insights available into the physiological effects and potential therapeutic utility of biased agonism for most of the class B1 family. For instance, a biased agonist of the PTH1R, with increased cAMP production capacity compared with arrestin recruitment relative to PTH, did not show increased bone building capacity in mice compared with this peptide (223). Conversely, the peptide [D-Trp12, Tyr34-PTH(7-34)], which was reported to selectively activate arrestin recruitment and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 relative to PTH (229), stimulated bone growth with decreased bone degradation in mice (221). These results point to potential superior performance for the treatment of osteoporosis by arrestin-biased PTH1R agonists, although it is noteworthy that the arrestin-biased activity of [D-Trp12, Tyr34-PTH(7-34)] could not be recapitulated in several cell types (230).

Biased Agonism at the GLP-1R

Pharmacologically and structurally, the best-studied class B1 receptor with respect to biased agonism is the GLP-1R. GLP-1R mediates the physiological functions of several endogenous peptides, including multiple forms of GLP-1 and oxyntomodulin, the latter of which is a lower potency dual agonist for GCGR and GLP-1R (215, 231). Glucagon and GLP-2 are also low potency agonists of the GLP-1R (215, 232). Numerous pharmacokinetically improved analogs of GLP-1 have been successfully developed as therapeutics for T2DM and obesity (233), and many other exploratory peptide agonists have been synthesized to interrogate GLP-1R function (210, 234). In addition, there are increasing numbers of small molecule agonists that have been identified (235–237), with 4 series undergoing clinical evaluation, including PF-06882961, PF-07081532, TTP-273 and OWL-833 (238–240). Thus, as a pleiotropically coupled receptor that can be activated by numerous ligands, the GLP-1R is disposed to biased agonism and indeed is among the best studied receptors for this phenomenon in both pharmacological and structural aspects.

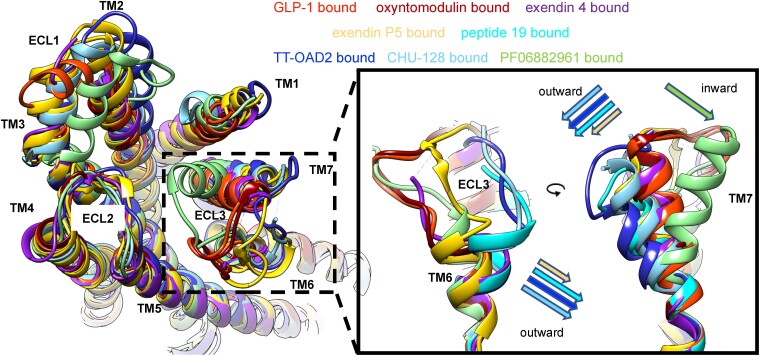

To date, more than 30 structures of GLP-1R have been solved, including both inactive crystal structures and active Gs-coupled GLP-1R cryo-EM structures (Table 1). The recently solved active structures of GLP-1R–Gs complex with different agonists, including GLP-1 (74), semaglutide, taspoglutide (80), oxyntomodulin, exendin 4 (83), exendin P5 (84), peptide 19 (85), TT-OAD2 (75), LY3502970 (OWL833) (86), tirzepatide (71, 87), Boc5 (88), peptide 20 (71), PF-06882961, and CHU-128 (74), provide important structural insights into biased agonism of this receptor. The largest structural divergence across all the GLP-1R–Gs complexes reported occurs in the conformation of the extracellular portion of TM6/7 and in ECL3 (Fig. 4). In the GLP-1–bound structure, this region forms extensive interactions with GLP-1, leading to a relatively closed binding pocket (74). PF-06882961 that has a similar pharmacological profile to GLP-1, also interacts with an ECL3 network, resulting in TM7 fully closing the TM binding cavity (74). Compared with GLP-1, the small molecular agonists CHU-128, TT-OAD2, and OWL-833 are strongly biased toward Gs-mediated cAMP production over other pathways, including β-arrestin recruitment, receptor internalization, pERK1/2, and calcium mobilization. In the GLP-1R-Gs complexes, these agonists fail to form interactions with ECL3, leading to a large outward shift of this region and a more open binding cavity that is exposed to bulk solvent (74, 75). The open conformation of TM6/7 and ECL3 of GLP-1R was also observed with peptide agonists bound, including exendin P5 (84) and peptide 19 (85) that are full agonists for activation of cAMP signaling but display varying degrees of agonism in other signaling pathways (209, 241). Taken together, this open conformation of TM6-ECL3-TM7, or at least the potential for greater dynamics within this region as discussed below, appears to be correlated with biased agonism away from regulatory pathways, such as arrestin recruitment and receptor internalization. This hypothesis is supported by mutagenesis studies demonstrating a greater importance for specific interactions in TM7 and the TM6/ECL3 boundary for G protein-mediated cAMP signaling of GLP-1 compared with those of CHU-128, TT-OAD2 or exendin-P5 (74, 84, 171). Compound 2 is also a biased agonist; however, the reported structures with compound 2 displayed closed conformations of TM6-ECL3-TM7 of GLP-1R. The ability of the ligands to support a closed conformation of the receptor in these studies is potentially due to the presence of the NanoBit tethering strategy used in the compound 2–containing structure (79), which was reportedly required to stabilize the complex.

Figure 4.

Alignment of GLP-1R bound with different biased peptide and nonpeptide agonists, illustrating differences in conformations of deposited structures. Oxyntomodulin (7LLY), exendin 4 (7LLL), exendin P5 (6B3J), peptide 19 (7RTB), TT-OAD2 (6ORV), CHU-128 (6X19), and PF 06882961 (6X1A) relative to full agonist GLP-1 (6X18). Left, extracellular side of GLP-1R; highlights the largest divergence that occurs in the TM6-ECL3-TM7 region (dashed square), although distinctions in the conformations of ECL1 are also common. Right, outward positioning of the top of TM6/7 and ECL3 is observed in exendin P5, peptide 19, TT-OAD2, and CHU-128–bound structures; the extent of these differences relative to the closed conformation of GLP-1-bound receptor is shown as arrows. In contrast, PF 06882961 promotes a significant inward movement of TM7 and ECL3, while oxyntomodulin and exendin 4 have similar receptor conformations, compared with GLP-1-bound GLP-1R. Only structures solved with equivalent stabilizing technology, and reconstitution conditions are displayed to limit potential for structural differences that are unrelated to the ligand used for structure determination.

The collective structural information provides insights into how GLP-1R biased agonism may arise and could facilitate rational design of biased agonists targeting the GLP-1R. There is emerging evidence that suggests biased agonism toward G protein signaling over β-arrestin recruitment and internalization may be advantageous in vivo (209, 210, 242). This information may also be broadly applicable within the class B1 family.

Importance of Receptor Dynamics in Peptide Pharmacology

Approaches for Study of Class B1 GPCR Dynamics

GPCRs are inherently mobile, so structural information about dynamics is desirable to understand receptor function (243–245). To this end, a battery of techniques including NMR, single-molecule fluorescence techniques, crosslinking, HDX-MS, and double electron-electron resonance has been applied to study the structure and dynamics of GPCRs (246–249). X-ray crystallography provides global structural information, but only as a snapshot within a rigid crystal lattice. Complementary to yielding high resolution, global, structural information, cryo-EM can readily provide insights into the dynamics of proteins in a near-native environment without the need for labeling (250–252). Among the most versatile tools to interrogate flexibility in cryo-EM datasets is principle component analysis (251–253), which, without prior information, can resolve conformational heterogeneity into continuous “movies” of modes of motion captured as series of EM maps. As named in the cryoSPARC image processing software (254), this technique is referred to later in this text as 3D-variability analysis (3DVA). Recently, this ability of cryo-EM to provide dynamic information has shed light on the ligand selectivity and activation pathways for GPCRs (255).

Dynamics of Peptide Agonist-Bound Receptor Gs Complexes

Cryo-EM driven insights into the conformation and conformational dynamics of bound peptide hormones, particularly for the critical, receptor-activating N-terminal region, have provided new viewpoints in light of previously inconsistent evidence. Solution structures of peptide hormones in the glucagon and PACAP families suggested a propensity for helical secondary structure in the C-terminal region (256–258), matching what was observed in crystal and cryo-EM structures (78). However, the N-terminal regions in solution and in a receptor bound structure of PACAP(1-21) (259), were observed to be unstructured (256, 257, 260), ostensibly conflicting with cryo-EM data of full-length receptors with helical N-termini when bound to receptors (78, 103). Furthermore, observations that polypeptide-binding GPCRs generally recognize turn secondary structures (261) and the presence of helix-capping motifs in class B1 hormone sequences (262) drew questions to the functional relevance of active state structures with helical N-termini (263). Oddo et al sought to resolve the conflicting data by generating GLP-1 and exendin-4 analogs with disulfide constraints between the second and fourth residues from the N-terminus (263). Constrained analogs of both high and low potency adopted a type II β-turn motif in the N-terminal region when bound to the ECD. However, molecular dynamics simulations suggested a high degree of flexibility in the N-terminus, even for constrained analogs (263). A cryo-EM structure including a potent GLP-1R agonist with a turn-favoring amino acid, D-alanine, in place of glycine 4 was observed to occupy 2 states, 1 helical and 1 unstructured; conversely, substitution of glycine 4 with a helix-promoting, cyclic β-amino acid (264) yielded an analog that potently inhibited GLP-1-mediated cAMP production, suggesting that N-terminal flexibility is important for activity (81). Further supporting this hypothesis, Deganutti et al showed, through a combination of cryo-EM data, molecular dynamics simulations, and functional studies, that the kinetics of G protein conformational changes and heterotrimer dissociation are correlated with the dynamics of peptide agonist N-termini interactions with the receptor TMD (83). A related study showed a positive correlation between the rate of peptide dissociation and the rate of cAMP production (198). Collectively, these studies point to a model in which partial dissociation of the peptide from the TM bundle is important for efficient transducer protein turnover.

Receptor and agonist dynamics might also play a role in the structural underpinnings of biased agonism. This hypothesis is tangentially supported by demonstrations that agonists can exhibit time-dependent alterations to the apparent direction and magnitude of biased agonism (265). The peptide GLP-1R agonists semaglutide and taspoglutide exhibit bias toward cAMP signaling with small but significant reductions in β-arrestin2 recruitment and receptor recycling, respectively, when compared with native GLP-1 (266), whereas the peptides exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin exhibit biased agonism toward arrestin recruitment (83). Alanine scanning mutagenesis studies across the extracellular region of the GLP-1R TMD revealed that the TM1/TM7/ECL3 region is critical for biased agonism by peptide ligands (specifically GLP-1, exendin-4, and oxyntomodulin); mutations to residues in these domains differentially affected ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which involves both noncanonical G protein– and β-arrestin–mediated signaling, but had less impact on cAMP production that is predominantly G protein mediated (171, 267). Despite similar static structures of GLP-1R bound to GLP-1, semaglutide, taspoglutide, exendin-4, and oxyntomodulin, differences in the conformational dynamics of the TM6-ECL3-TM7 region were identified by 3DVA (251). Moreover, divergent dynamics in other regions such as the receptor ECD, peptide N terminus, and G protein were observed that might be linked to the induction of biased agonism. However, the exact mechanism by which dynamics affect specific signaling or regulatory profiles of individual agonists is still unclear.

While the GLP-1R is the most well-studied class-B1 GPCR from a structural dynamics perspective, dynamics have been observed by cryo-EM for other receptors: the C-termini of PTH1R agonists, PTH, and LA-PTH were observed in multiple conformers (105, 107), and cryo-EM data of CGRPR (110) and AM receptors (112), CTR, and AMYRs (64) support the hypothesis that dynamics play a role in ligand selectivity (discussed further below). Moreover, common modes of gross flexibility between receptor and G protein, specifically twisting and rocking motions, have been observed by single-particle EM for diverse GPCRs (268). However, all current systems for structural study of GPCR-G protein complexes involve some degree of engineering to stabilize interactions, and further exploration will be needed to elucidate the functional significance of these commonly observed motions.

Structural Basis for Receptor Activity-Modifying Protein Regulation of Phenotype

Receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) are single-pass transmembrane proteins that can interact with class B1 GPCRs and modulate their pharmacology (269–271). In mammals, there are 3 RAMPs (RAMP1, RAMP2, and RAMP3), which can introduce functional diversity to GPCRs. Although sharing only ~30% sequence identity, the members of the RAMP family have a unified overall structure, consisting of a single transmembrane-spanning domain (~21 amino acids), a large N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD; with tertiary structure containing 3 α helixes, ~90-100 residues), an unstructured juxtamembrane linker (~10 amino acids), and a short intracellular C-terminal tail (~9 amino acids). While RAMP1 and RAMP3 have a high structural similarity in the ECD and a similar length signal peptide (~25 amino acids), the RAMP2 precursor has a longer signal peptide and larger ECD (6). There are conserved cysteine residues participating in disulfide bonds in the ECD among RAMPs, giving rise to a common tertiary structure of 3 α helices (41, 272). RAMP3 has multiple glycosylation sites, 1 of which is conserved in RAMP2; however, mammalian RAMP1 is not glycosylated due to the lack of glycosylation sites (273, 274).

RAMPs are best recognized for their interactions with CLR and CTR, although evidence for broader interaction of RAMPs with other class B1 GPCRs has emerged (275–280). The variations among RAMPs enable them to modify CLR or CTR to produce receptor complexes with distinct binding specificity and downstream signaling profiles. In addition, association with RAMPs can control GPCR cell surface expression, modulate receptor internalization, and alter trafficking that may affect the activation of intracellular signaling pathways. For instance, CLR by itself does not bind to any known ligand and fails to translocate to the cell surface (115). With RAMP1, it forms the canonical CGRPR, whereas coexpression of CLR with RAMP2 or RAMP3 gives AM1 and AM2 receptors, respectively, both of which respond to AM and AM2 (also named intermedin). The AM2 receptor has moderate affinity for calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP), and the CGRP receptor is also able to bind AM peptides with lower affinity (115).

Unlike the CLR, the CTR alone is expressed robustly at the cell surface where it preferentially responds to calcitonin (CT), with only low affinity for amylin (Amy) and CGRP peptides. CTR generates a family of AMYRs (AMY1-3R) upon association with 1 of the 3 corresponding RAMPs. AMY1R has a similarly high binding affinity and cAMP potency for Amy and CGRP, with lower affinity for CT. Similarly, AMY3R has high affinity/potency for Amy with lower affinity/potency for CT but possesses lower affinity for CGRP (281). In contrast, AMY2R has similar affinity and potency for CT and Amy peptides. Interestingly, unlike human CT (hCT), CT from salmon (sCT) has similar cAMP potency in cell lines expressing the CTR alone, or the CTR with each of the 3 RAMPs (282). The promiscuity in peptide interaction with distinct GPCR/RAMP heterodimers hints at subtle differences in the interaction between RAMPs and partner GPCRs. Earlier studies using chimeric RAMPs with exchanged N- or C-terminus between RAMP1 and RAMP2 revealed that the large ECD of RAMPs is a key determinant of ligand binding selectivity, however the C-terminus can also modulate signaling, at least in the case of AMYRs (283, 284).

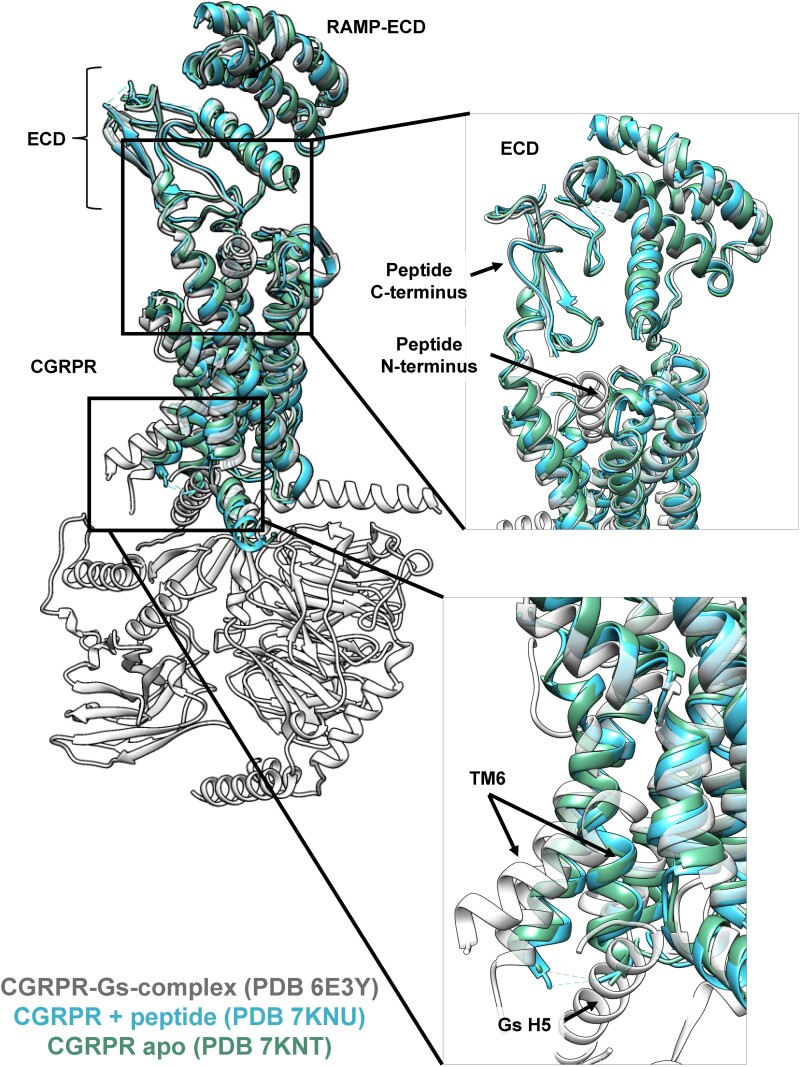

Molecular understanding of how RAMPs allosterically modulate GPCR conformation, ligand affinity and signaling has been significantly expanded by recent structural studies. A series of crystallography studies of soluble CLR/RAMP ECD complex structures in either apo or peptide/small-molecule antagonist-bound states revealed initial insights into how the ECD of the RAMP packs with the ECD of these receptors and provided some insights into how revealed how the C-termini of the peptides engage with the ECD of the receptor-RAMP complex (41, 272, 285). In 2018, the first full-length, cryo-EM structure of CGRP-bound human CGRPR complexed with the canonical transducer Gs was reported, providing a breakthrough in understanding how peptides bind the TMD and how the ECD orients relative to the receptor core (62). This structure also revealed how the RAMP engages the receptor with the TMD forming interactions along the lipid exposed face of TMs 3,4 and 5 of the CLR, and the stalk forming interactions with ECL2.

Cryo-EM structures of the AM1 and AM2 receptors (AM1R and AM2R), reported in 2020, provided substantial insights into how the CLR is differentially modulated by RAMP2 and RAMP3, respectively (112). Compared with the CGRPR, the AM receptors show a distinctive ECD orientation, and, compared with AM2R, the AM1R showed greater overall motion in the ECD, as assessed by 3DVA. Moreover, AM1R exhibited outward movement of ECL3. As with the RAMP1, the linker regions of RAMP2 and RAMP3 were observed to interact with the CLR ECL2. Studies using chimeric RAMP constructs identified that the linkers, more specifically the ECL2-binding regions (residues 108-112), are key determinants for the distinctive pharmacology of the GCRPR and AM receptors.

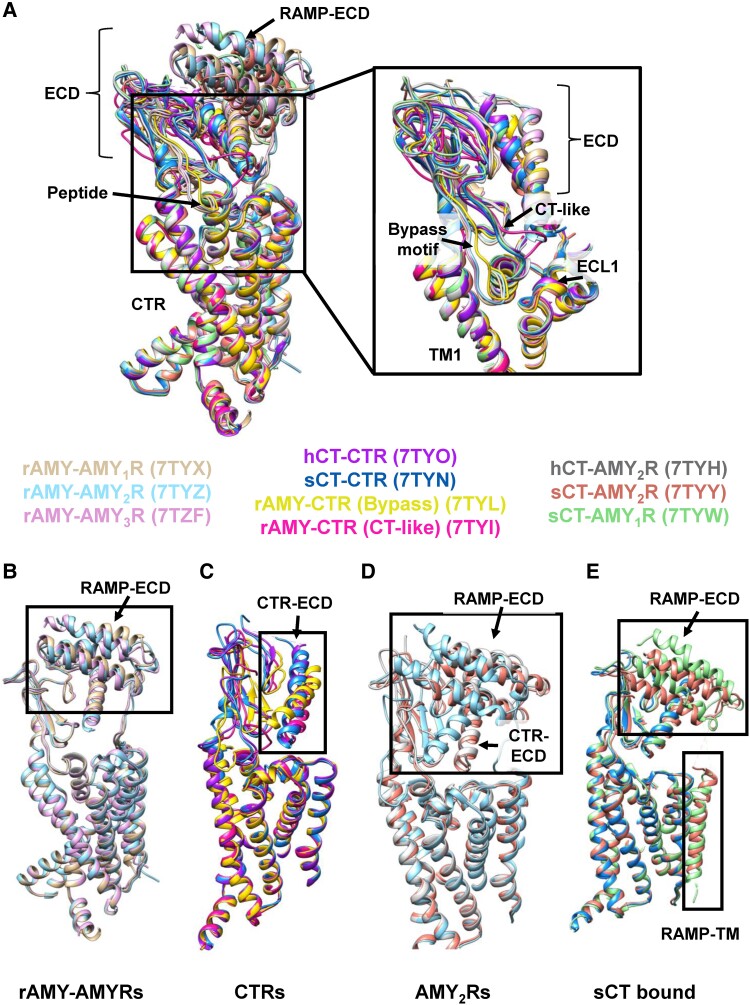

In 2022, the molecular basis for CT/Amy peptides selectivity at CTR and AMYRs was revealed by high-resolution cryo-EM structures of these receptors bound to different peptides (64), including amylin, hCT, and sCT bound structures (Fig. 5A). The resulting structures showed that the CT- and Amy-based peptides activated the AMYRs by distinct mechanisms that could account for the differences in the pharmacology of the peptides. Similar to the CLR-RAMP structure, the RAMP TM domain interacts with TM3, TM4, and TM5 of CTR with the RAMP TMD-ECD linker forming interactions with ECL2 in the presence of amylin.

Figure 5.

Alignments of deposited structures of CTR and AMYRs. (A) Left: The receptors, peptides, and RAMPs from the CTR/AMYR family overlaid and displayed as a ribbon and colored as shown in the key. PDBs are in parentheses. The primary structural differences occur on the extracellular side of the receptor. Right: A close-up view of the peptides leaving the TM bundle and interacting with the ECD with the bypass and CT-like motifs highlighted. The RAMP ECDs were removed for clarity. (B-E) Divergent conformations of the ECDs are highlighted for a subset of the structures. (B) rAmy bound to AMY1R, AMY2R, and AMY3R shows subtle differences in the positions of the RAMP ECD but high similarity in the overall architecture of the receptor. (C) CTR bound to hCT, sCT, and rAmy (adopting bypass and CT-like conformations). The largest difference in the structures occurs where rAmy adopts a bypass motif conformation causing the CTR ECD to change orientation. (D) AMY2R bound to rAmy, hCT, and sCT. The difference in the ECD position between the CT peptides and rAmy is highlighted. (E) sCT bound to CTR, AMY1R and AMY2R with changes in the RAMP ECD and TM regions highlighted.

Rat amylin (rAmy), which is used as a less aggregation-prone surrogate for human amylin, bound AMY1R-Gs, AMY2R-Gs, and AMY3R-Gs structures had a very similar overall architecture (Fig. 5B), including for the orientation of CTR and RAMP ECD (64), differing from CLR–RAMP complex structures, where the orientation of the ECD was distinct for the CGRPR compared with AM receptors (199). Likewise, the structures of CTR or AMYR bound to the calcitonin peptides (hCT and sCT) were also remarkably similar, but differences were observed in the conformation when comparing to the Amy-bound AMYRs. Nonetheless, there was similar overlap of the N-termini of the peptides bound within the CTR TM bundle for each structure. In the AMYR structures, the N-termini of the peptides did not form any interactions with the RAMPs; therefore, the ligand binding site in the receptor core was topologically conserved across all the structures. However, while both the CT and Amy peptides exhibited a disordered C-terminus, differences were observed in the position of the peptides as they exit the TM bundle extending upwards to interact with the ECD. Amy, when bound to each of the AMYRs adopts a “bypass” motif, stabilized by intramolecular interactions, where this segment of the peptide (residues 19-25) sits parallel to the plane of the membrane before forming a sharp turn extending upwards to interact with the ECD. By comparison, the C-termini of the CT peptides extend immediately upwards into the ECD-binding pocket without displaying the “bypass” motif yet the C-terminal residues of CT and Amy peptides occupy a similar site on the ECD. The shorter CT-based peptides, relative to Amy peptides, result in the ECD of the CT-bound AMYRs being constrained to a similar orientation in the CT-bound CTR structures. This constraint requires disengagement of the RAMP linker and TM from ECL2 and the top of the CTR TMD to enable repositioning of the RAMP ECD; nonetheless, the interface between the ECDs of the RAMPs and CTR is equivalent in all structures. By comparison, in the rAmy-bound AMYR structures, there is a 12 Å shift in the position of the CTR ECD relative to the CTR ECD with either no RAMP present or with RAMP and CT bound. In the Amy-bound CTR-Gs complex, the Amy peptide was observed in both a bypass and CT-like conformation, suggesting that RAMP stabilizes the bypass motif and likely underpins the higher affinity for AMYRs relative to CTR, and might therefore be a useful segment to target for the design of novel AMYR selective and nonselective peptides (64).

In the cryo-EM structures, RAMP2 has a smaller TM interface with both CTR (AMY2R) and CLR (AM1R) (64, 112) compared with those of RAMP1 and RAMP3, and this observation can rationalize the higher potency of hCT at AMY2R. As noted above, the ECD of all complexes bound to CT peptides have orientations that are constrained by the shorter length of CT. In contrast to hCT that has low affinity for the isolated ECD and requires formation of an active complex with G protein for high affinity binding, sCT has higher affinity for the ECD, and this high affinity is largely independent of G protein engagement (286). In the sCT-bound AMY2R complex, the repositioning of the RAMP ECD is enabled by destabilization of the full TM interaction of RAMP2 and decoupling of the RAMP linker from ECL2. By comparison, to form the complex with the AMY1R, the tighter TM interface of RAMP1 primarily remains stable with only the upper segment of the TM interaction becoming unstable and allowing decoupling of the linker. As such, this process would have a high energy barrier and require higher affinity with the CTR ECD to achieve. The lower affinity of the hCT C-terminus for the CTR ECD limits the ability of this peptide to disrupt tighter interactions of RAMPs with the CTR core, but it is sufficient to overcome the lower energy barrier posed by the weaker RAMP2 interaction. Pointing to a lower energy barrier for RAMP2 movement, 3DVA showed that the AMY2R ECD is more dynamic than AMY1R or AMY3R upon Amy binding, supporting this rationale for the difference in relative potencies of hCT and Amy for the different AMYRs.

Mechanisms of Receptor Activation

Like all GPCRs, class B1 GPCRs activate by altering their conformational landscape in response to a signal, and the exact mechanism of this conformational change is of significant interest. Class B1 GPCRs do not contain the canonical receptor activation motifs identified in class A GPCRs (CWxP, DRY, PIF, and NPxxY motifs) (287, 288). However, a number of polar residues and unique motifs are conserved among class B1 receptors within the transmembrane bundle that are thought to play similar roles to those motifs found in class A receptors (132, 184, 289, 290). On the other hand, evidence for fundamental differences in guanine nucleotide exchange factor behavior arises from G protein dissociation assays, which suggest that class B1 receptors generally activate G proteins more slowly than their class A counterparts (67).

The upper layers of the TM bundle and the ECLs interact with key residues of peptide agonists to initiate receptor activation. A set of polar residues that line the basal surface of the inner TMD pocket, referred to as the central polar network, helps allosterically couple agonist to transducer engagement (132, 184, 289, 291). The identities of these central polar network residues are not all conserved among class B1 GPCRs, but the relative positions are maintained (eg, position 2.60: Arg, Asn, or Lys; position 6.52: Gln, Glu, Thr, or His; position 7.49: Gln or His; Asn3.43). Notably, waters have been identified bridging interactions between central polar network residues and the peptide, such as R1902.60 of GLP-1R and Glu9 of GLP-1 (74). For CHU-128 and PF 06882961, nonpeptide agonists of the GLP-1R that do not penetrate the TM bundle deeply, an extensive network of waters was observed. These rigid waters were hypothesized to engage the central polar network in a commensurate manner as the peptide N-terminus (74).

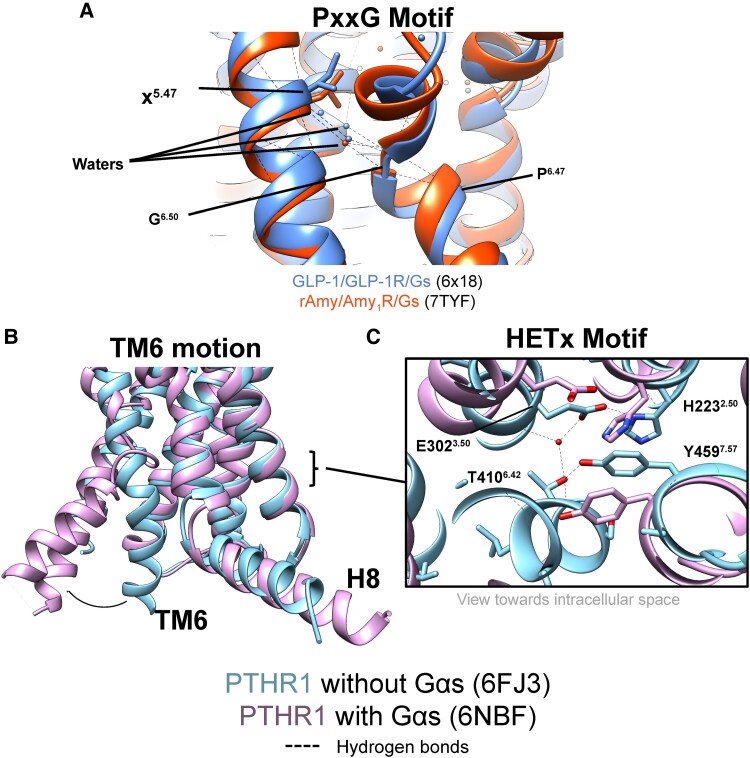

The P6.47xxG6.50 motif orchestrates outward TM6 movement and is therefore critical for receptor activation (141). While the 2 nonconserved residues in the core of the motif (x6.48x6.49) are not completely conserved, these residues are exclusively hydrophobic (either Leu_Leu, Leu_Phe, or Leu_Val in humans). During receptor activation, TM6 rotates and the x6.48x6.49 sidechains penetrate downwards to form a hydrophobic cluster near the apex of the kink together with conserved residues Leu3.54 and Leu6.45. Structural waters have also been identified in the vicinity of the P6.47xxG6.50 motif; notably, a water molecule bridges G6.50 and the backbone of TM5 (residue 5.51) in structures of the GLP-1R and CTR (Fig. 6) (64, 74). As such, structural waters likely play key roles in the formation of the TM6 kink.

Figure 6.

Critical conformational changes associated with class B1 GPCR activation. (A) Waters interacting with the PxxG motif of GLP-1R (6X18) and AMY1R (7TYF) in the active, G protein–coupled, state. (B) Comparison of the TM6 conformation in the structures of the PTHR1 with (6NBF) or without G protein (6FJ3), with the direction of change that occurs in the presence of G protein shown by the arrow. (C) HETx motif in structures of the PTHR1 with (6NBF) or without (inactive like) G protein (6FJ3). In the absence of G protein, a hydrogen bonding network is formed that stabilizes the ground state of the receptor; this is disrupted when G protein is bound.

Class B1 receptors contain an HETx (H2.50E3.50T6.42x7.57) motif that is a conserved apparatus near the cytoplasmic side that stabilizes an inactive state. Supporting this hypothesis, mutations affecting the HETx site can cause constitutive activity; the mutations H223R2.50 and T410P6.42, which are causative of Jansen's metaphyseal chondrodysplasia (292, 293), induce high basal cAMP formation downstream of the PTH1R (294). Mutations to the HETx motif in the GCGR, VPAC1R, and CRF1R also lead to constitutive activity (295). In humans, class B1 receptors contain a tyrosine residue at x7.57, except for CLR that contains a phenylalanine. The aromatic character is likely crucial for x7.57 as it makes pi–pi interactions with the imidazole of the absolutely conserved H2.50. In a high-resolution crystal structure of the PTH1R without G protein–bound (106), ground state interactions of the HETx motif are supported by this aromatic interaction as well as by a water-bridged hydrogen bond between E3.50 and T6.42 (Fig. 6). The phenol of Y4597.57 also makes polar interactions with T6.42. G protein engagement requires disruption of these ground state HETx interactions, and, indeed, disruption is observed for residues in all structures of G protein–bound class B1 receptors; most notably, T6.42 is rendered completely inaccessible for HETx interactions due to the large outward TM6 motion.

In 2021, cryo-EM structures of the CGRPR in the apo and peptide–bound states (without transducer) were published, providing significant insights into receptor activation mechanisms (110). Compared with the G protein–coupled complex (111), the CGRP-bound receptor did not exhibit the TM6 kink that is traditionally associated with class B1 receptor activation (110), with the backbone architecture of the apo and peptide-bound complexes exhibiting only minimal differences in consensus structures (Fig. 7). Additionally, EM density for the CGRP peptide was observed for C-terminus, but not the N-terminus. 3DVA and HDX-MS studies revealed enhanced dynamics at the extracellular face of the TMD upon peptide engagement with the ECD that enabled transient interactions of the CGRP N-terminus with the receptor core, consistent with the 2-domain class B1 GPCR peptide binding model. These transient interactions further destabilized the ground state interactions at the intracellular side of the receptor that help maintain an inactive state, enhancing the receptor dynamics at the intracellular face that facilitate G protein coupling enabling the receptor to adopt the fully active receptor conformation that stabilizes N-terminal peptide engagement deep in the TMD (110).

Figure 7.

Alignments of the CGRPR in peptide and Gs bound, peptide bound, and apo forms. The CGRP-binding pocket and Gs binding pocket are highlighted. The peptide agonist N-terminus is modelled in the Gs-bound structure (6E3Y) but not in the peptide-alone bound form (7KNU).

Nonpeptide Ligand Binding

Class B1 GPCRs are traditionally considered difficult targets for small, drug-like molecules (296). In particular, the orthosteric sites that peptide ligands engage are expansive and shallow, which introduces challenges akin to those of targeting protein–protein interfaces with small molecules (297). Nevertheless, numerous nonpeptide molecules targeting class B1 receptors have been developed (298–300), including some that have entered clinical trials (89, 301, 302). Structures of class B1 GPCRs have been determined with more than 10 different small molecules (Table 1). These small molecules either bind to a site overlapping with the native hormone or at a distal site (orthosteric and allosteric binding, respectively). There are at least 3 different allosteric binding sites that have been identified in class B1 GPCRs.

The extracellular interfaces between the TMs of GLP-1R are important epitopes for small molecule binding, such as for LSN3160440 (90), an allosteric potentiator of the metabolite GLP-1(9-36)NH2 which has low affinity and very week intrinsic efficacy. LSN3160440 interacts with Y1451.40 and Y205ECL2 and forms direct interactions with the GLP-1 peptide. Several other nonpeptidic GLP-1R ligands, including Boc5, WB4-24, and OWL-833, contain appendages that interface with the TM1/TM2 gap (79, 88). TT-OAD2, a nonpeptidic agonist of the GLP-1R, contains a hydrophobic moiety that instead inserts between TM2/TM3. Further investigation will be required to determine whether these interhelical epitopes of other class B1 GPCRs are amenable to small molecule targeting. Another allosteric binding site deep inside the TM bundle was observed for the CRF1R small-molecule antagonist, CP-376395 (52, 113).

The membrane facing surface around TM6 is a hotspot for allosteric modulators of the glucagon family, which is not surprising given the importance of TM6 for receptor activation. NNC0640, a negative allosteric modulator (NAM) of the GCGR, straddles the base of TM6, which presumably holds it in a closed position (72, 91, 303). MK-0893 and PF-06372222, related small-molecule GCGR and GLP-1R NAMs, respectively, adopt similar poses to NNC0640 (70, 91).

In addition to acting as a site for NAMs, the external face of TM6 is a known site for positive allosteric modulators (PAMs). BETP, an electrophilic small molecule (304), covalently modifies C3476.36 GLP-1R to potentiate receptor activation (305), particularly for low efficacy agonists. GCGR can be sensitized to the effects of BETP when cysteine is introduced at the corresponding residue (305). At present, there are no available structures containing BETP, but there are several structures containing another C3476.36 targeting electrophilic PAM, compound 2. Both BETP and compound 2 also exhibit intrinsic efficacy for Gs-mediated cAMP production (also termed, ago-PAM [agonist-PAM]), although compound 2 has substantially greater intrinsic agonist activity (306). Compound 2 and BETP likely act by destabilizing the ground state interactions of the GLP-1R's TM6.

While nonpeptide ligands are available for multiple class B1 GPCRs, only GLP-1R nonpeptidic agonists have entered clinical trials, including PF-06882961 (Pfizer) (307), PF-07081532 (Pfizer/Heptares), TTP-273 (vTv Therapeutics/Huadong Medicine), and OWL-833 (Chugai/Eli Lilly). GLP-1R-Gs structures bound to PF-06882961, RGT1383 (an analog of PF-06882961), CHU-128 (an analog of OWL-833)/OWL-833, or TT-OAD2 (an analog of TTP-273) reveal that these nonpeptidic agonists bind superficially to the extracellular side of the orthosteric pocket, adopt unique poses with respect to each other that in turn stabilize distinct receptor conformations (74, 75, 82, 86, 92). PF-06882961 binds in a vertical orientation within a completely closed cavity, overlapping the location of the mid region of bound GLP-1 (74); in contrast, CHU-128, OWL-833, and TT-OAD2 have much larger binding pockets, with more planar binding poses (parallel to the membrane) and less overlap with the peptide binding site (74, 75, 86). Of note, these structures revealed structural water-mediated networks within the large peptide binding cavity that play critical roles for GLP-1R activation by different nonpeptidic agonists (74). These findings could potentially provide a basis for further development of GLP-1R agonists with better therapeutic effects than those currently available or with better absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion/PK profiles, and it is plausible that other class B1 GPCRs could be targeted in a similar manner.

Unanswered Questions and Next Frontiers

GPCRs can couple to a variety of effectors proteins, however class B1 GPCRs have been exclusively determined in the presence of 1 group of coupling partners: G proteins. Furthermore, only a single structure of a class B1 receptor bound to a noncanonical (not Gαs) G protein has been reported (GCGR bound to Gαi (69)) despite evidence for broader pleotropic coupling (308). Conversely, structures of GPCRs of other families have been determined in complex with arrestins, regulator of G protein signaling proteins, and G protein receptor kinases (309–315). Full understanding of the molecular mechanisms underpinning biased agonism will likely require structures of class B1 GPCRs coupled to transducer proteins for both favored and less well coupled pathways. The PTH1R has been reported to form complexes with G proteins and arrestins simultaneously (316), and so it might be possible to visualize class B1 GPCRs in complex with multiple signaling partners (317). Observing large signaling complexes or clusters (150, 318) in situ in cellular membranes may become feasible with further advances in cryo-electron tomography (319).

Owing to advances in cryo-EM, structures of GPCRs bound to transducer proteins have emerged at a rapid pace. However, cryo-EM structures for inactive and apo forms of receptors have lagged far behind, partly due to their intractably small size and also their inherent structural dynamics. Additional data for apo and inactive state structures would bolster understanding of the ground state interactions and might reveal the basis for the inverse agonism that has been observed at certain class B1 receptors such as the GCGR (36), GLP-1R (320), and at PTH1R variants (321, 322). Among class-B1 GPCRs, only the CGRPR, which contains a RAMP that adds mass and constrains the ECD's mobility, has been determined by cryo-EM in apo or peptide-bound forms (110). At present, most inactive and apo structures are not within reach by cryo-EM, but molecular fiducial markers might help make apo structures of class B1 receptors accessible (323–326). While promising, these approaches might require bespoke and extensive protein engineering.

Several class B1 GPCRs can form functionally relevant homodimers or heterodimers (327–330). With the exception of an antiparallel PAC1R/Gs dimer that was useful for structure determination but of dubious physiological significance (104), no structures of class B1 receptor dimers have been reported, potentially due to their transient nature. Moreover, in at least 1 study of the CTR, the stability of the dimer interface was reduced upon G protein binding (197), suggesting that current studies focused on active-state ternary complexes may favor the monomeric form of the receptor. Compared with monomers, however, GPCR oligomers might be more amenable to cryo-EM studies of apo receptors, due to their greater size and the potential for symmetry. Resulting structures of dimers would be valuable to understand the molecular basis for (negative) ligand-binding cooperativity, which has been observed at the Secretin receptor (331). In addition, while many class B GPCRs are reported to interact with RAMPs, structures of these complexes remain elusive. Understanding the structural implications of multimerization might be challenging without a more native membrane mimetic system (eg, nanodiscs, amphipols, or saposin discs (332, 333)); however, all structures of class B1 GPCRs thus far have been reported in detergent micelles. Beyond multimerization, it is plausible that functionally relevant conformational differences may manifest in more native membrane mimetic systems compared with detergent micelles.