PURPOSE

Digital technologies create opportunities for improving consenting processes in cancer care and research. Yet, little is known about the prevalence of electronic consenting, or e-consent, at US cancer care institutions.

METHODS

We surveyed institutions in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network about their capabilities for clinical, research, and administrative e-consents; technologies used; telemedicine consents; multilingual support; evaluations; and opportunities and challenges in moving from paper-based to electronic processes. Responses were summarized across responding institutions.

RESULTS

Twenty-five institutions completed the survey (81% response rate). Respondents were from all census regions and included freestanding and matrix cancer centers. Twenty (80%) had e-consent capabilities, with variability in the extent of adoption: One (5%) had implemented e-consent for all clinical, research, and administrative needs while 19 (95%) had a mix of paper and electronic consenting. Among those with e-consent capabilities, the majority (14 of 20, 70%) were using features embedded in their electronic health record. Most had a combination of paper and e-consenting for clinical purposes (18, 72%). About two-thirds relied entirely on paper for research consents (16, 64%) but had at least some electronic processes for administrative consents (15, 60%). Obstacles to e-consenting included challenges with procuring or maintaining hardware, content management, workflow integration, and digital literacy of patients. Successes included positive user experiences, workflow improvements, and better record-keeping. Only two of 20 (10%) respondents with e-consent capabilities had evaluated the impact of automating consent processes.

CONCLUSION

E-consent was prevalent in our sample, with 80% of institutions reporting at least some capabilities. Further progress is needed for the benefits of e-consenting to be realized broadly.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of consenting processes in health care is to assure that patients are fully informed about the risks, benefits, and other provisions of research, clinical, and administrative procedures.1,2 Consenting processes in health care institutions currently are often paper-based, which creates limitations and inefficiencies.3,4 For example, paper forms may be illegible, inaccurate, incomplete, or lost. They require scanning for inclusion in electronic records, and they cannot be easily completed in a remote care environment. These limitations frequently lead to quality problems and patient and provider dissatisfaction.4,5

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To what extent have leading US cancer centers implemented electronic consenting processes, and what benefits, challenges, and other lessons learned have they experienced?

Knowledge Generated

Most of the surveyed institutions have some electronic consent capabilities, but practices and future plans vary widely. Evaluation efforts are urgently needed to spur further progress.

Relevance

Electronic consenting offers many potential benefits, but institutions' experiences indicate that implementation can be highly complex. Cancer centers' early efforts suggest key strategies for realizing e-consent's benefits for providers and patients alike.

The emergence of digital technologies creates opportunities for improvement of consenting processes.5-7 Electronic consent (e-consent), where documentation of the consent process is captured in an interactive application, benefits both patients and providers by, for example, eliminating legibility issues and lost forms, assuring completeness and remote access, and eliminating the need for scanning. These characteristics also reduce dependency on paper, improve compliance with guidelines, reduce the risk of perioperative delays, and augment efficiency and satisfaction. Additionally, with the rise in telemedicine, e-consent can support remote care models.

Although there have been characterizations of research e-consent, little is known about the prevalence of e-consent at US health care institutions.7,8 A nascent literature reveals assorted clinical, research, and administrative applications at various hospitals and medical centers, but no systematic data exist across consent types.7,8 Similarly, there are no standards of practice, leaving institutions to develop their e-consent procedures in isolation. We, therefore, sought to map the landscape of e-consent practices among leading US cancer care centers. Oncology offers a unique window into e-consent, given the diversity of institutions that provide care, the frequency and range of clinical procedures, and the volume and variety of ongoing research trials. To help understand the current state of e-consent prevalence and characteristics, we conducted a national survey of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Member Institutions, exploring the extent to which they use e-consent and for what purposes. We hypothesized that substantial heterogeneity would exist, with some institutions still relying primarily on paper and others having advanced e-consent applications for clinical, research, and administrative functions.

METHODS

This research was determined to be exempt from review by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review Board. Our methods are reported according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (Data Supplement).

Study Participants

Our survey aimed to probe the current and future state of electronic consent adoption at the cancer centers that are members of NCCN. A not-for-profit organization promoting accessible, high-quality cancer care, NCCN develops clinical guidelines and other resources to inform clinicians, patients, and other health care stakeholders.8-12 NCCN administered the survey through its Electronic Health Record (EHR) Oncology Advisory Group, which has a representative from each of 32 member institutions (31 at the time of this survey).

Approach

The survey was pilot tested by two NCCN Member Institutions to ensure clarity and relevance. The remaining NCCN Member Institutions then received an email inviting them to participate via an electronic survey tool.13 The email also included a PDF copy of the survey instrument. Participants were able to share the PDF and the link to the online survey with other colleagues as needed, but each institution was instructed to submit a single response. No incentives were offered for participation. The survey launched on January 26, 2022, and closed on February 25, 2022.

Survey Content

Respondents were asked to report the extent to which their consents could be captured electronically for a variety of clinical, research, and administrative consents. Clinical consents were defined as consents for operating room procedures, office-based procedures, blood transfusions, systemic therapies, radiation therapy, and other clinical services. Research consents were defined as consents for therapeutical clinical trials, nontherapeutic clinical trials, observational studies, registry trials, and other research protocols.12 Administrative consents were defined as nonresearch, nonclinical consents, for example consents for release of information, for participation in health information exchanges, and for other administrative purposes. We asked respondents for details such as what technology was being used, whether consents could be captured via telemedicine, if languages other than English were supported, whether evaluations had been performed, if witness workflows were supported, and whether they had future plans for electronic consenting. For each survey answer, participants were invited to share more details in free-text boxes. Respondents were also asked to describe opportunities and challenges in moving from paper-based to electronic consent processes (see Data Supplement for survey instrument).

Adaptive questioning and skip logic were used to streamline participant experience. To ensure completeness, we provided do not know/not sure options, and all questions were required to be completed before proceeding. All participating institutions provided complete responses.

Analysis

Responses were summarized across member institutions. Adoption of e-consent was stratified by institutional characteristics including: Prospective Payment System exemption, National Cancer Institute designation, structure (freestanding or matrix), funding model (public or private not-for-profit), and US Census region. The results from the survey were presented to the NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group on April 18, 2022, and approved for publication by the NCCN.

RESULTS

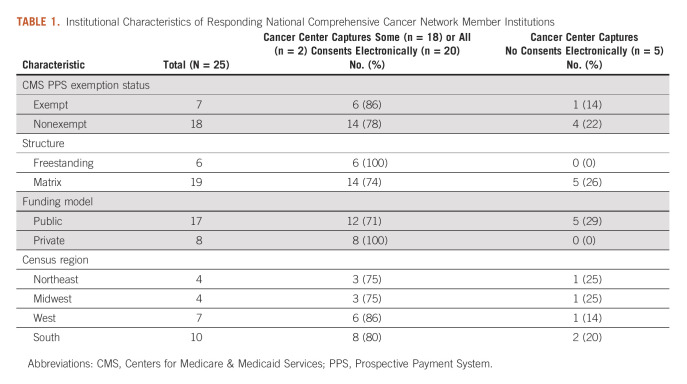

Of the 31 NCCN Member Institutions, 25 completed the survey, for a response rate of 81%. Responding organizations were similar to nonresponders (Data Supplement). Respondents were from all census regions and included freestanding as well as matrix cancer centers (Table 1). Among the individuals submitting responses, 14 (56%) were informatics leaders at their institutions, eight (32%) were medical directors, two (8%) were operations directors, and one (4%) was a director of quality improvement.

TABLE 1.

Institutional Characteristics of Responding National Comprehensive Cancer Network Member Institutions

Frequency and Correlates of Adoption

Five of 25 cancer centers responding to our survey (20%) still relied exclusively on paper for all consenting purposes. Twenty (80%) reported having e-consent capabilities, with wide variability in the extent and duration of adoption, ranging from months to 10+ years. One (5%) had implemented e-consent for all clinical, research, and administrative needs while 19 (95%) had a mix of paper and electronic consenting. A higher proportion of private and freestanding cancer centers had adopted at least some e-consent capabilities compared with public and matrix organizations (100% private versus 71% public; 100% freestanding versus 75% matrix, Table 1).

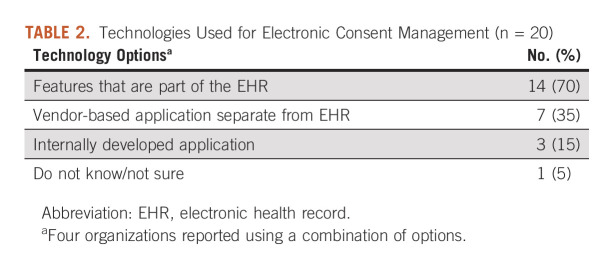

Technology, Logistics, and Evaluation

Among the 20 cancer centers with e-consent capabilities, the majority (14, 70%) were using features embedded in the EHR. Some were using separate vendor-based or internally-developed applications (seven, 35%). Four (20%) were using a combination of technology options (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Technologies Used for Electronic Consent Management (n = 20)

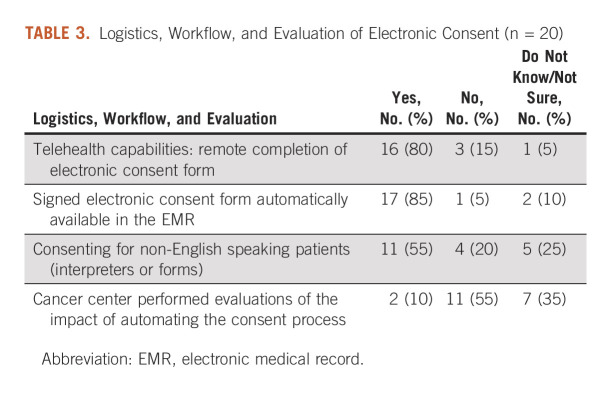

Among cancer centers with e-consent, the majority (16, 80%) had systems which allowed for remote completion of the e-consent form (eg, via a telehealth encounter). Likewise, 17 (85%) had made the signed e-consent form automatically available in the electronic medical record. About half (11, 55%) could support e-consenting for non-English-speaking patients, either through translated forms or interpreters. Few with e-consent capabilities (two, 10%) had performed evaluations of automating their processes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Logistics, Workflow, and Evaluation of Electronic Consent (n = 20)

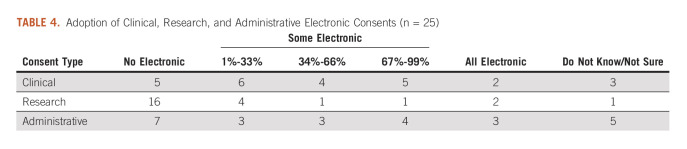

Clinical Consents

A large majority of cancer centers in our sample reported having a combination of paper and e-consenting for clinical purposes (18, 72%), with the percentage captured electronically ranging from 2% to 90%. Two (8%) had shifted fully to e-consent for clinical needs while five (20%) still relied entirely on paper (Table 4). Half of the cancer centers with e-consent capabilities required a witness electronic signature for some (seven, 35%) or all (three, 15%) clinical e-consents. E-consent was somewhat more common for blood transfusions and operating room and office-based procedures (12-13, 48%-52%) than for radiation and systemic therapies (9-10, 36%-40%; Data Supplement).

TABLE 4.

Adoption of Clinical, Research, and Administrative Electronic Consents (n = 25)

Research Consents

About two thirds of our sample still relied entirely on paper consenting for research purposes (16, 64%). Another quarter reported having a mix of paper and electronic consenting (seven, 28%), with the percentage captured electronically ranging from 1% to 95%. Two (8%) had shifted fully to e-consent for research (Table 4). E-consent was more frequently available for nontherapeutic clinical trials, observational studies/registry trials, and health care delivery studies (seven to nine, 28%-36%) than for therapeutic clinical trials (four, 16%; Data Supplement).

Administrative Consents

Nearly two thirds of our sample (15, 60%) had at least some electronic processes for administrative consents, with three (12%) having shifted completely to e-consent. For those with partial adoption, estimates for the percentage of administrative consents captured electronically ranged from 15% to 90% (Table 4). Seven cancer centers (28%) still relied exclusively on paper.

Obstacles

Twenty (80%) respondents provided free-text descriptions of the obstacles their cancer centers face around e-consent. A range of key themes emerged from their comments, which are verbatim below:

-

Many described technological difficulties or limited ability to customize or configure vendor software:

"Occasional technical problems with internally developed application."

"Vendor = less control."

-

Several reported challenges with procuring or maintaining specialized hardware:

"Equipment malfunction or lack of availability (signature pads, iPads)."

"Availability of signature pads in all locations (eg, not currently available inpatient)."

-

Others described tensions around content management of e-consent forms:

"Inability to amend and keep a history is an issue as well, particularly when plans or risks change, then a new one needs to be done which leads to multiple consents for the same treatment."

"Research consents are all different and always changing, which makes implementation more difficult."

-

Some described workflow problems:

"If [e-consents] are incorrect, they are difficult to delete or change once they are signed."

"Workflow in clinical environments is heterogeneous. COVID/work from home and organizational growth and reorganization has challenged administrative roll out."

"Inertia with current paper-based processes…High expectations for functionality in some settings."

"In some situations, [e-consent requires] transfer of administrative tasks from staff to [physicians]."

-

Several faced challenges making e-consent accessible to patients:

"Use of iPads, patient's health [literacy] [are problems]."

"How to obtain remote electronic consent for patients not using patient portal."

-

A few pointed to concerns about compliance and other policy challenges:

"Regulatory hurdles, that is, 21 CFR Part 11 compliance and validation."

"Institution policy about privacy/authentication/etc."

-

And others identified the main obstacle as a fundamental lack of resources or prioritization:

"No resources have been allocated or formal needs assessment has been completed."

"The cancer center does not have an informatics team and the university does not support any central e-consent system."

Success Stories

Eight (32%) respondents provided free-text descriptions of accomplishments implementing e-consent at their cancer centers. Again, a variety of themes emerged:

-

Some reported having made good progress overall:

"A vast majority of our clinical/surgical procedures are now done electronically as well as most administrative consents are done via the patient portal. All good stuff."

-

Others provided more specific success stories, such as positive user experiences:

"Many enthusiastic pilot users, both [physicians] and staff. Good acceptance by patients."

"Remote signing is easier."

-

Several mentioned workflow improvements:

"We were able to implement multiparty consents in Epic that mirror our paper workflow very well. For instance, a resident, fellow, or pharmacist can sign chemotherapy consent and the attending will sign second. If the attending signs first, no other signatures are required."

"Improved staff efficiency."

-

Better record-keeping and access were also noted:

"Consents are not lost."

"E-consents has allowed [the forms] to be easily found by our teams and live within the patients chart for easy access."

Future Plans

Nearly all cancer centers in our sample provided free-text descriptions around future plans to implement or expand e-consents (19, 76%). Their aspirations ranged widely across four broad themes:

-

A few reported having no concrete goals:

"[In the] distant future would like to move to electronic consents."

"At this point, [e-consent] is nothing more than a topic of conversation."

-

Some were focused on one or two specific goals:

"Chemotherapy consent is our next step."

"Improving ability to collect consent asynchronously and to file directly to EHR."

-

Many others were aiming to ramp up e-consent across two or more domains:

"Increase percentage of clinical consents captured electronically, including systemic therapy consents, and add research consents into application."

"[We are planning] deployment of clinical consents to additional settings, especially procedural consents. Continued efforts to advance adoption of research consents. Support for multiple languages. Support for proxy signatures."

-

Several had ambitious plans for 100% electronic availability:

"We are rolling out e-consent to all consents, in cancer and noncancer."

"[In] October 2022…will move to having almost all consents performed electronically."

DISCUSSION

Consent is an important process in health care to ensure that patients are fully informed of the risks and benefits of clinical procedures, research studies, and administrative processes. Increasingly, care processes are being digitally-enabled and remote care is being utilized. Enabling a fully digital experience for patients and providers demands that consenting processes, too, be automated. Electronic consents can lead to improvements in quality (complete and never lost documents), efficiency (immediate availability, decreased delays because of missing forms), patient experience (no resigning necessary), support for telehealth care models, and improved regulatory compliance (data and time stamps, completeness, and secure confidentiality procedures). Electronic consents in complex scenarios—for example, consent for genomic data sharing—can support researcher awareness of data that are permissible to access and support regulatory processes to assure that data are accessed only when permitted.

In our sample, electronic consenting is not yet ubiquitous, with 80% of institutions reporting at least some e-consent capabilities, and the organizations that do have it have variable adoption and anywhere from 1 to 10 years of experience. There is also variability in the technology that is being used to achieve the capability as well. Many organizations in our sample reported benefits from the use of electronic consents. For example, among organizations with e-consent capabilities, a large majority (16 of 20, 80%) reported some capability to support e-consenting via telemedicine. Multiple methods were described for achieving e-consent via telehealth, and future research could explore the relative effectiveness of these varied approaches. Many complex consent-related workflows, for example, addressing multiple providers on a single consent and the incorporation of witness signatures, have been solved by some organizations. In addition, at least some organizations reported administrative efficiencies and stakeholder satisfaction as a result of electronic consenting.

When compared with clinical and administrative consents, research consents had the lowest adoption of electronic consenting. There are several reasons why research e-consents may be difficult to implement. First, the high number of research protocols that may be in place at a cancer center—along with the amendments that often occur to such protocols—demands processes for managing the diverse electronic content of these kinds of consent forms. Second, clinical trial sponsors often expect participating organizations to use the sponsors' consenting solutions. This creates additional disincentives and complexities to the adoption of e-consent. Third, workflow for clinical trials research may be spread across multiple applications, for example, the EHR and a clinical trial management system. Adding yet another electronic application to this environment could create demands for data integration and possibly workflow challenges. Since there are substantial potential benefits of automation of research consents, more work is needed to understand how these hurdles can be addressed. Additionally, at academic medical centers, information technology support for clinical processes often can take precedence over support for research processes.

On the whole, we found that some organizations had already solved many of the obstacles and challenges mentioned by others. For example, some organizations reported workflow issues, but others said complex workflows could be successfully managed. This suggests the need to define best practices which can be broadly shared.

Organizations seeking to adopt e-consent face challenges and opportunities. From a technology point of view, several options are available. Leading EHR vendors offer such capabilities, as do third-party vendors. Extant paper-based workflows may vary widely among providers, whereas electronic workflows are much more standardized. Institutional leadership is required to achieve such change. Additionally, institutional consent policies may need to be amended to include details related to electronic consent. Organizations need to assure that their policies for capturing electronic signatures are compliant with local, state, and federal regulations. Most (16 of 20, 80%) cancer centers in our sample that are performing electronic consent indicated they have the capability to capture consents in a telehealth context, so hybrid workflows can be supported. As with all patient-facing technology, additional research is required to assure that disparities are not created as technology-based consenting solutions are introduced.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample size was small and limited to a group of leading cancer centers in the United States (NCCN Member Institutions). Our findings may not be representative of practices at other institutions that provide cancer care. Second, our methods relied on self-reporting, so our findings reflect the institutional knowledge of those responding to our survey. Actual practices may differ. Third, although we obtained an initial understanding of how organizations address such issues as remote care, multilingual, and witness-related workflows, we are left with many unanswered questions. This suggests the need for future research to explore these in greater detail and track progress over time. Fourth, our study broadly examined research, clinical, and administrative consent practices at diverse institutions. It would be worthwhile to explore these in greater depth.

As the need to accommodate hybrid care delivery models increases, successful development and implementation of e-consent processes will be crucial. Our study offers insight into the extent to which leading cancer centers have adopted e-consent processes. Although development of best practices for adoption of e-consent was outside the scope of this study, a better understanding of what works, and does not, could help accelerate the broad transition to guiding organizations in the transition to electronic consenting processes. It is notable that few organizations in our study have begun an evaluation process. More understanding of the range of organizations' experiences and outcomes is needed. In addition, more research is needed to understand if the potential quality and efficiency benefits of e-consenting are realized in practice. These data can inform the development and sharing of best practices around strategy, technology, implementation, content management, workflow integration, and other key issues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Jessica Sugalski, MPPA, and Tricia Heinrichs, MSM, of the NCCN for their help in the implementation of the survey. We would also like to thank the members of the NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group for completing the survey and providing thoughtful comments on the aggregate responses.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by a grant to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Susan Chimonas, Allison Lipitz-Snyderman, Gilad J. Kuperman

Collection and assembly of data: Susan Chimonas, Allison Lipitz-Snyderman, Gilad J. Kuperman

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/cci/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hall DE, Prochazka AV, Fink AS. Informed consent for clinical treatment. CMAJ. 2012;184:533–540. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.112120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bottrell MM, Alpert H, Fischbach RL, et al. Hospital informed consent for procedure forms: Facilitating quality patient-physician interaction. Arch Surg. 2000;135:26–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. St John ER, Scott A, Irvine T, et al. Completion of hand-written surgical consent forms is frequently suboptimal and could be improved by using electronically generated, procedure-specific forms. Surgeon. 2017;15:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siracuse JJ, Benoit E, Burke J, et al. Development of a Web-based surgical booking and informed consent system to reduce the potential for error and improve communication. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40:126–133. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reeves JJ, Mekeel KL, Waterman RS, et al. Association of electronic surgical consent forms with entry error rates. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:777–778. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chhin V, Roussos J, Michaelson T, et al. Leveraging mobile technology to improve efficiency of the consent-to-treatment process. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1–8. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skelton E, Drey N, Rutherford M, et al. Electronic consenting for conducting research remotely: A review of current practice and key recommendations for using e-consenting. Int J Med Inform. 2020;143:104271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen C, Lee PI, Pain KJ, et al. Replacing paper informed consent with electronic informed consent for research in academic medical centers: A scoping review. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2020;2020:80–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2022. https://www.nccn.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stetson PD, McCleary NJ, Osterman T, et al. Adoption of patient-generated health data in Oncology: A report from the NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2022:1–6. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tevaarwerk AJ, Chandereng T, Osterman T, et al. Oncologist perspectives on telemedicine for patients with cancer: A national comprehensive cancer Network survey. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e1318–e1326. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buckley MT, Lengfellner JM, Koch MJ, et al. The Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) electronic informed consent (eIC) platform for clinical trials: An operational model and suite of tools for obtaining informed consent, and managing consent documents. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15 suppl):e18577. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Survey Monkey. 2022. https://www.surveymonkey.com/ [Google Scholar]