Abstract

Background

Postnatal depression is a medical condition that affects many women and the development of their infants. There is a lack of evidence for treatment and prevention strategies that are safe for mothers and infants. Certain dietary deficiencies in a pregnant or postnatal woman's diet may cause postnatal depression. By correcting these deficiencies postnatal depression could be prevented in some women. Specific examples of dietary supplements aimed at preventing postnatal depression include: omega‐3 fatty acids, iron, folate, s‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine, cobalamin, pyridoxine, riboflavin, vitamin D and calcium.

Objectives

To assess the benefits of dietary supplements for preventing postnatal depression either in the antenatal period, postnatal period, or both.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 April 2013).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, involving women who were pregnant or who had given birth in the previous six weeks, who were not depressed or taking antidepressants at the commencement of the trials. The trials could use as intervention any dietary supplementation alone or in combination with another treatment compared with any other preventive treatment, or placebo, or standard clinical care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and assessed the risk of bias for the two included studies. Two review authors extracted data and the data were checked for accuracy.

Main results

We included two randomised controlled trials.

One trial compared oral 100 microgram (µg) selenium yeast tablets with placebo, taken from the first trimester until birth. The trial randomised 179 women but outcome data were only provided for 85 women. Eighty‐three women were randomised to each arm of the trial. Sixty‐one women completed the selenium arm, 44 of whom completed an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). In the placebo arm, 64 women completed the trial, 41 of whom completed an EPDS. This included study (n = 85) found selenium had an effect on EPDS scores but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). There was a mean difference (MD) of ‐1.90 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.92 to 0.12) of the self‐reported EPDS completed by participants within eight weeks of delivery. There was a high risk of attrition bias due to a large proportion of women withdrawing from the study or not completing an EPDS. This included study did not report on any of the secondary outcomes of this review.

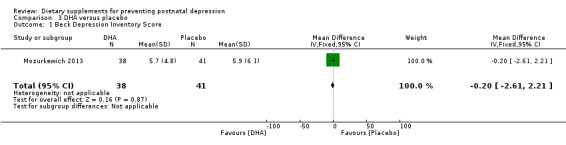

The other trial compared docosahexanoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) with placebo. The trial randomised 126 women at risk of postpartum depression to three arms: 42 were allocated to EPA, 42 to DHA, and 42 to placebo. Three women in the EPA arm, four in the DHA arm, and one woman in the placebo arm were lost to follow‐up. Women who were found to have major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, current substance abuse or dependence, suicidal ideation or schizophrenia at recruitment were excluded from the study. The women who discontinued the intervention (five in the EPA arm, four in the DHA arm and seven in the placebo arm) were included in the intention‐to‐treat analysis, while those who were lost to follow‐up were not. Women received supplements or placebo from recruitment at a gestational age of 12 to 20 weeks until their final review visit six to eight weeks postpartum. The primary outcome measure was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score at the fifth visit (six to eight weeks postpartum). No benefit was found for EPA‐rich fish oil (MD 0.70, 95% CI ‐1.78 to 3.18) or DHA‐rich fish oil supplementation (MD 0.90, 95% CI ‐1.33 to 3.13) in preventing postpartum depression. No difference was found in the effect on postnatal depression comparing EPA with DHA (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐2.61 to 2.21). No benefit or significant effect was found in terms of the secondary outcomes of the presence of major depressive disorder at six to eight weeks postpartum, the number of women who commenced antidepressants, maternal estimated blood loss at delivery or admission of neonates to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to conclude that selenium, DHA or EPA prevent postnatal depression. There is currently no evidence to recommend any other dietary supplement for prevention of postnatal depression.

Plain language summary

Dietary supplements for preventing postnatal depression

Postnatal depression is a common condition that affects women and may impact on their babies. Common symptoms of postnatal depression include fluctuations in mood, mood changes, suicidal ideation and preoccupation with infant well‐being ranging from over‐concern to frank delusions. There is currently not much evidence regarding interventions that might prevent or treat postnatal depression. A diet lacking in certain vitamins, minerals or other nutrients may cause postnatal depression in some women. Correcting this deficiency with dietary supplements might therefore prevent postnatal depression. Examples of possible dietary supplements aimed at preventing postnatal depression include omega‐3 fatty acids, iron, folate, s‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine, vitamin B12 (cobalamin), B6 (pyridoxine), B2 (riboflavin), vitamin D and calcium.

This review identified two randomised controlled studies. One study examined the effect of selenium supplements taken by women from the first trimester to birth in preventing postnatal depression. This study had a high risk of bias because of women withdrawing or not completing their self‐scoring system for depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale). It may also have been difficult to ensure that the women took their supplements because of concerns that exist about taking supplements during pregnancy. More high‐quality studies would be required to confirm any benefit in preventing postnatal depression using selenium.

This review also identified one randomised controlled study that compared docosahexanoic and eicosapentaenoic acid to placebo in women at risk of postpartum depression. This study found that neither docosahexanoic acid nor eicosapentaenoic acid prevented postpartum depression.

Overall, there is not enough evidence at this stage to recommend selenium, docosahexanoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid or any other dietary supplement for the prevention of postnatal depression. Unfortunately there were no other studies of other dietary supplements that met our selection criteria. Other dietary supplements need to be studied in trials where depressed women are excluded from entry to determine if supplements prevent postnatal depression.

Background

Description of the condition

Postnatal mood disorders are heterogeneous (Brockington 2004) and range from postnatal blues that affect 15% to 80% of postnatal women (Beck 2006; Pitt 1973), to postpartum psychosis that affects one in 2000 women (Kendell 1987). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (APA 2000) defines postnatal depression as a major depressive episode with postpartum onset if the onset is within four weeks postpartum. It distinguishes postpartum depressive episodes from the 'baby blues', which affect up to 80% of women during the first 10 days postpartum, but are transient and do not impair functioning (APA 2000; Cox 2003). The DSM IV and International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) criteria concur that postnatal depression can last for any length of time between two weeks and one year postpartum, and is differentiated from normal postpartum emotional adjustment by the pattern of symptoms, and the severity and consistency with which they occur (Cox 1987a; Cox 2003; Gibbon 2004). The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and provides a common language and standards for classification of mental disorders. It is used mostly in the United States. The ICD‐10, produced by the World Health Organization, is another standard of classification and is mainly used in Europe. Symptoms of postnatal depression include mood lability, sleep disturbances such as waking at night or early rising not related to the baby, appetite disturbances and weight loss, ‘thought blocking’ and mental sluggishness, suicidal ideation, and preoccupation with infant well‐being ranging from over‐concern to frank delusions. Delusions are associated with an increased risk of harm to the infant (Austin 2008; Brockington 2004). Although not classified as a distinct syndrome, the ICD10 classifies depression after childbirth as “mild (four symptoms), moderate (five symptoms) or severe (five symptoms or more, plus agitation, feelings of worthlessness or guilt or suicidal thoughts or acts)” (Fisher 2009).

Whether postnatal depression is distinct from major depression, or just coincidental timing of a major depressive episode with the postnatal period is an area of speculation (Brockington 1996; Steiner 1990). The major life changes associated with the transition to motherhood are an obvious potential stressor, and cause emotional disruption in even the most resilient of women (Beck 2006). However, it is unlikely that the most important precipitating factors of an episode of postnatal depression are particular to pregnancy and its aftermath (Brockington 1996; Hanley 2009). Whilst the prevalence of depression in postnatal women is similar to the incidence in the general female population, there is a three‐fold increase in the incidence of depression in the first five weeks postpartum (Cox 1993). Approximately one‐third of women who develop postnatal depression may experience symptoms in the first four weeks; two‐thirds will develop them between 10 and 14 weeks; and cases who present later are often misdiagnosed or missed altogether (Hanley 2009). Three longitudinal studies from both high‐income countries (US and UK) and low‐ and middle‐income countries (Brazil) have found an increase in the incidence and symptoms of postnatal depression around three months postpartum, with a second peak occurring around nine months postpartum (Gjerdingen 2011; Lobato 2011; Nott 1987). Nott 1987 even suggests that the incidence of new cases of postnatal depression was highest three to nine months postpartum, which is outside of the period when women would have regular contact with postpartum clinical services and depression screening.

The problem for prevention and treatment lies in the lack of consensus regarding the aetiology, definition, and tools for detection of this condition. Consequently, the study and management of women with "melancholia" after childbirth (Brockington 1996) has fallen between several disciplines ‐ that of primary care, obstetrics, and psychiatry. Also, there are multiple pathways towards an episode of postnatal depression, and different women will find alternative modes of treatment and/or support to be effective (Austin 2008; NHMRC 1999).

Description of the intervention

The overall hypothesis of this review is that certain dietary deficiencies in a pregnant or postnatal woman's diet may cause postnatal depression. Hence, correcting these deficiencies with dietary supplements could prevent postnatal depression.

The intervention considered was dietary supplements given before the onset or diagnosis of postnatal depression. Examples include omega‐3 fatty acids, iron, calcium, vitamin B12 (cobalamin), riboflavin (B2), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), folate, S‐adenosyl‐methionine (SAMe) and vitamin D (Freeman 2009). Dietary supplements were defined as any vitamin, mineral or compound that exists naturally and could be reasonably expected to be part of the normal human diet. Intervention with supplementation would be expected to correct a current or potential deficit in these vitamins, minerals or other compounds.

Omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are found in oily fish and seafood as docosahexanoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). During the last century, the diets of industrialised societies have contained significantly lower amounts of omega‐3 fatty acids, and relatively higher levels of omega‐6 polyunsaturated fatty acids Simopoulos 2008). There also appears to be a correlation between fish consumption rates and depression, with lower reported incidence of depression in people from Hong Kong, China, and Japan compared with Western countries (Hibbeln 2002). Lower rates of fish consumption have also been correlated with higher rates of postnatal depression (Rees 2005). Women have been found to be depleted in omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids during gestation and breastfeeding as there is preferential diversion of omega‐3 fats to the baby (Huang 2013). It has been hypothesised that if low omega‐3 levels are associated with depression, one reason women are more vulnerable to depression postnatally is due to depletion of their omega‐3 fatty acids (Rees 2005). A previous non‐Cochrane systematic review (Wojcicki 2011) looked at the association between omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation and the risk of perinatal depression. It reviewed 10 articles and found that six found no association, two found mixed results and two found a positive association between omega‐3 supplementation and reduced risk of perinatal depression. This review included longitudinal cohort studies, randomised controlled trials and pilot trials. All of the randomised controlled trials included mixed populations of depressed and non‐depressed women on entry into the studies so none of these studies could be classified as purely investigating a prevention effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on postnatal depression. One of the pilot studies in which women were excluded at entry if they were depressed showed no preventive effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on perinatal depression (Marangell 2004).

Other dietary deficiencies may play a part in postnatal depression. In one study, iron treatment resulted in a 25% improvement in previously iron‐deficient mothers’ depression and stress scales, whereas anaemic mothers who received placebo did not improve (Beard 2005). Anaemia is a risk factor for postnatal depression (Corwin 2003), hence postpartum haemorrhage may also be a cause of postnatal depression. Albacar (Albacar 2011) found an association between low ferritin 48 hours after delivery and postpartum depression. S‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine, alone or in combination with pharmacologic antidepressants, has been effective in the treatment of major depression (Mischoulon 2002). One prospective study examined the relationship of dietary consumption of folate and B vitamins during pregnancy with the risk of postpartum depression (Miyake 2006). There was no measurable association between intake of folate, cobalamin, or pyridoxine and the risk of postpartum depression. Compared with riboflavin intake in the first quartile, only riboflavin consumption in the third quartile was independently related to a decreased risk of postpartum depression. In another study, nulliparous women, between 11 and 21 weeks' gestation, were randomised to receive either placebo or 2000 mg elemental calcium per day as participants in the NIH‐sponsored Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) trial. The study found there was a trend toward less depression in calcium‐supplemented women (Harrison‐Hohner 2001). An association has been found between low vitamin D serum levels and depression in older persons (Hoogendijk 2008). If reduced vitamin D levels are linked to depression then it is not unreasonable that correcting a deficiency may be helpful for postnatally depression women.

Hence, certain nutritional deficiencies such as low levels of DHA found in seafood, calcium, B vitamins, vitamin D, and iron have been investigated in relation to postnatal depression but so far this research has been inconclusive (Hanley 2009; Miller 2002). Further research into the biological aetiology of postnatal depression is required, as studies to date have been quasi‐experimental, or randomised controlled trials with small sample sizes of varying methodological quality (Dennis 2009; Miller 2002).

How the intervention might work

Dietary supplementation individually or in combination could be shown to indicate a significant effect in preventing postnatal depression.

Specific hypotheses for how each intervention works are related to the particular intervention. For instance, iron supplements may prevent iron deficiency anaemia, hence preventing maternal lethargy and concomitant depression. But iron deficiency also affects electrophysiological recordings and neurotransmitter metabolism with no direct association to anaemia (Beard 2005). Correcting iron deficiency may normalise neural functioning through direct electrochemical mechanisms. S‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine is involved in methylation of biological proteins which are integral to neural functioning of neurotransmitters, phospholipids, and cellular receptors and channels (Mischoulon 2002). Folate also is involved in methylation of homocysteine and a deficiency may have a similar effect biochemically to a deficiency of S‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine (Freeman 2009). Omega‐3 fatty acids are known to affect neurotransmitters, peptides, releasing factors, hormones, and a variety of physiological and cognitive processes. Fatty acids also may exert a controlling function in the modulation of neuronal membrane fluidity (Yehuda 1999). Nuclear receptors for vitamin D exist in neurons and glial cells. Vitamin D is involved in the biosynthesis of neurotrophic factors, and at least one enzyme involved in neurotransmitter synthesis. Vitamin D can also inhibit the synthesis of inducible nitric oxide synthase and increase glutathione levels, suggesting a role for the hormone in brain detoxification pathways (Garcion 2002).

The hypothesis upon which this review is based is that postnatal depression can be linked to, or contributed to by a dietary deficiency in one or more compounds, and that replacement of these compounds can prevent postnatal depression. It is also likely that women undergoing pregnancy and childbirth require increased amounts of these compounds compared with non‐pregnant women. What is regarded as normal intake outside of pregnancy and childbirth would be insufficient for the extra dietary requirements of pregnancy and childbirth.

Why it is important to do this review

Postnatal depression is the most common complication of childbirth, which not only impacts maternal well‐being, but also infant and child development, and family cohesion (Fisher 2009; Harpham 2005). A large systematic review of postnatal depression in low‐ and middle‐income countries identified a pooled prevalence of common postnatal mental disorders of 19.8% (Fisher 2012). Prevalence of postnatal depression has been estimated to be between 10% and 20% worldwide, although rates vary within and between countries (Affonso 2000; O'Hara 1996). Furthermore, the recurrence rate of postnatal depression is significant (25% to 68%) (Dalton 1982; Wisner 2004). Women who have suffered from postnatal depression are also twice as likely to suffer from further episodes of depression over a five‐year period (Cooper 1995).

Postnatal depression can cause impaired maternal‐infant interactions (Cooper 1998; Murray 1996) and negative perceptions of infant behaviour (Mayberry 1993) that have been linked to attachment insecurity (Hipwell 2000; Murray 1992). Other effects on the infant include cognitive developmental delay (Deave 2008; Hipwell 2000), social/interaction difficulties (Cummings 1994; Murray 1999), impaired expressive language development (Cox 1987), attention‐ (Breznitz 1988), and long‐term behavioural problems (Beck 1999). Infants of depressed mothers have been shown to have a statistically significant poorer growth than infants of non‐depressed mothers at the third month postpartum (Adewuya 2008). Child abuse/neglect (Buist 1998) and marital stress resulting in separation or divorce (Boyce 1994; Holden 1991) are other reported outcomes. Effective treatment for postnatal depression may not be sufficient to improve the developing mother‐child relationship (Forman 2007). Hence in this aspect, prevention is better than treatment.

Several Cochrane reviews have considered various strategies for the prevention and treatment of postnatal depression. However, to date there appears to be no effective strategy for the prevention of postnatal depression among these reviews. One intervention that might be effective in preventing postnatal depression is telephone‐based peer support among women at high risk (Dennis 2009).

Intensive, professionally‐based postpartum support for at‐risk women appears promising (Dennis 2004); however, antenatal interventions do not appear to be effective (Austin 2008). One review reported that synthetic progestogens could double the incidence of postnatal depression (Dennis 2008a). Oestrogens and natural progesterone have not been tested in a randomised trial. In terms of other alternative therapies, massage and/or acupuncture have not been demonstrated to improve antenatal depression immediately after treatment or prevent postnatal depression (Dennis 2008b). One systematic review found that some psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression appear to be effective in reducing Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores; however, the methodological quality of the included trials was not strong, and the long‐term effectiveness is unclear (Dennis 2007a). There is not enough evidence to demonstrate that these interventions can treat antenatal depression (Dennis 2007b). This is despite the fact that women prefer to have counselling with someone who was non‐judgmental, rather than receive pharmacological interventions (Dennis 2006).

Antidepressants given postpartum cannot be recommended for prevention of postnatal depression as there is a lack of clear evidence (Howard 2005). There is also little evidence for using antidepressants for the treatment of postnatal depression (Hoffbrand 2001), although this is certainly the current standard accepted practice among clinicians. Another issue regarding the acceptability of antidepressants as a treatment for postnatal depression is their transfer from mother to infant through breastfeeding, although most antidepressants are believed to be safe with breastfeeding (Kendall‐Tackett 2007). Antidepressants given in the third trimester have been associated with transient neonatal withdrawal syndrome, which includes jitteriness, muscle weakness, and respiratory difficulties (Oberlander 2004). There are concerns regarding unknown effects of antidepressants on the fetus and infant as well. There is a paucity of information on the concentrations of different drugs that are excreted in breast milk and their associated toxicity profiles (Fortinguerra 2009; Hanley 2009). Some significant areas of concern exist with antidepressant use in pregnancy, particularly some evidence of higher risk of preterm birth, neonatal adaptation difficulties, and congenital cardiac malformations with paroxetine (Udechuku 2010).

Compared to other treatments, dietary supplements are an inexpensive, readily available form of intervention and are generally free of side effects. Furthermore, there is marketing of over‐the‐counter dietary supplements in pharmacies and supermarkets for the purpose of preventing postnatal depression, without clear evidence of benefit. On examining the literature there appear to be no concerns mentioned with regard to micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy where it is recommended to correct specific deficiencies (Shah 2009). Concerns have been raised concerning excessive consumption of vitamin A. However, excessive dietary intake of vitamin A has been associated with teratogenicity in humans in less than 20 reported cases over 30 years (Azaïs‐Braesco 2000). This review is not intended to address the effects of excessive or supra‐physiological doses of dietary supplements. It is intended only to address the effects of correcting dietary deficiencies.

Postnatal depression has a high recurrence rate and treatments may not improve the mother‐infant relationship. The symptoms of postnatal depression are generally assumed to have a deleterious effect on mother‐infant interaction, as mothers experience low energy levels and ambivalence towards the baby. This in turn inhibits their ability to provide a nurturing, responsive environment for their infants and children (Hanley 2009; Pedros‐Rosello 2007). Hence the focus of this review will be on interventions that may prevent this condition.

Objectives

To assess the effects of dietary supplements used either alone or in combination with pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions on the incidence of postnatal depression up to 12 months postpartum.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised trials of dietary supplements given to women in the antenatal period or postnatal period, or both antenatal and postnatal period for the prevention of postpartum depression. There were no language restrictions. We planned to consider studies presented only as abstracts. Quasi‐randomised trials were not eligible for inclusion. Trials using a cross‐over design were also not eligible for inclusion, as they would not be appropriate for the short antenatal and postnatal periods of time being studied.

Types of participants

Women who were pregnant or had given birth in the previous six weeks, who were not taking any antidepressant medication at the start of the trial. Trials could include only women with a history of depression and/or postnatal depression, or offer the intervention to all pregnant women, but women must not have been depressed at the beginning of the trial. Trials including women already taking dietary supplements before trial commencement were eligible. We excluded trials involving women who already had antenatal depression.

Types of interventions

Any dietary supplementation alone or in combination with another treatment compared with any other preventive treatment, or placebo, or standard clinical care.

Specific examples of dietary supplements aimed at preventing postnatal depression include: omega‐3 fatty acids, iron, folate, s‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine, cobalamin, pyridoxine, riboflavin, vitamin D and calcium.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Postnatal depression

Postnatal depression can be measured using any of the scales mentioned below:

an estimate of depression as measured by investigators using any of the following: screening instruments such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox 1987a), Hamilton or Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961; Hamilton 1960), the Montgomery‐Asberg scale (Montgomery 1979); or

use of standard observer‐rated depression symptom scales by a recognised diagnostic scheme, e.g. DSM IV‐TR (APA 2000), ICD10,(WHO/DIMDI 2006) or by other standardised criteria such as the Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978).

We used the threshold scores used by the trial investigators for the respective scales.

Secondary outcomes

A. Maternal outcomes

Postpartum psychosis

Postpartum anxiety

Postpartum haemorrhage/bleeding

Maternal mortality and serious morbidity including self‐harm, suicide attempts

Health service utilisation including outpatient and inpatient use of psychiatric unit

Use of anxiolytic or antidepressant medication or electroconvulsive therapy

Maternal‐infant attachment

Maternal confidence (as defined using a scale such as the Maternal Confidence Questionnaire (MCQ) or similar)

Self‐esteem (as defined by the self‐esteem psychometric instrument used by trial investigators)

Maternal satisfaction with intervention (including dropout rates)

B. Neonatal outcome

Breastfeeding continuation at three months

Infant developmental assessments (as defined in trials, i.e. cognitive, emotional, social or behavioural)

Neurodevelopment at childhood follow‐up at two years

Child abuse and/or neglect

Neonatal/infant mortality

Serious neonatal/infant morbidities such as failure to thrive

Infant health parameters including immunisation, accidental injury, non‐accidental injury

C. Family outcomes

Serious marital discord, and/or separation/divorce

Family violence

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (30 April 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (B Miller and T Kent) independently assessed for inclusion all studies identified as eligible by our search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion and, if required, we consulted a review author (M Beckman).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. Two review authors (B Miller and T Kent) extracted the data from the included studies using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion and, if required, we consulted a third review author (M Beckman). We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (B Miller and T Kent) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor (L Murray).

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at a low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. In future updates where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we will re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. 20% or less missing data);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether this study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

Dichotomous data were presented as a summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference. In future updates of this review, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this version of the review. However, if we identify cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in a subsequent update of this review, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

We noted levels of attrition in both included studies. In future updates, we plan to explore the impact of high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial is the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In future updates of this review, if we pool data in meta‐analyses, we will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if the T² is greater than zero and either an I² is greater than 30% or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If in future updates of the review there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). If in future updates of this review it becomes possible to pool data, we will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if we detect substantial statistical heterogeneity, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. We will treat the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, we will present the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates of this review, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Population: women at increased risk of postnatal depression versus those not at increased risk.

Intervention: type of supplementation ‐ omega‐3 versus other supplements.

Intervention: usual diet of the population (specifically high fish consumption versus average or low consumption).

Intervention: combinations of treatments ‐ dietary supplementation alone versus additional pharmacological agents; and versus hormonal supplements; and versus psychological and/or social support.

Measurement of outcome: outcome assessed within the first two weeks postpartum versus the outcome assessed from two weeks or more postpartum.

We will restrict subgroup analysis to the primary outcome (postnatal depression).

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2011). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and p‐value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

In future updates we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of date of publication, sample size, method of diagnosing depression, duration of follow‐up, high drop‐out rates (more than 20%), and blinded versus unblinded outcome assessors on the primary outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

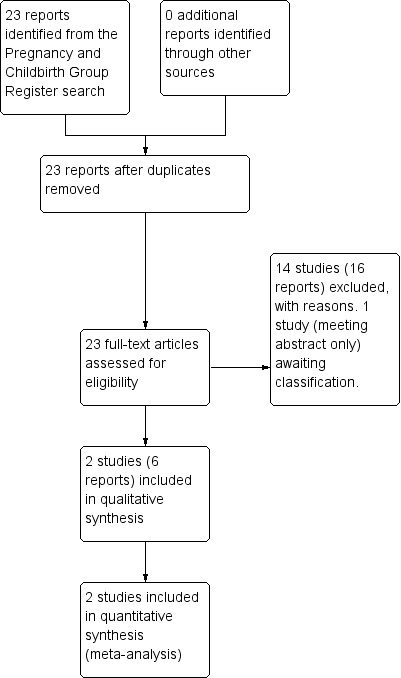

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register retrieved 23 trial reports. Of these, we included six reports (relating to two studies) and excluded 16 reports (relating to 14 studies). One report is awaiting classification. (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two trials fulfilled our eligibility criteria (Mokhber 2011; Mozurkewich 2013).

The first randomised controlled study (Mokhber 2011) involved 179 Iranian pregnant primigravid women who were randomised to either 100 µg selenium yeast tablets or placebo tablets. Women were screened at recruitment with a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) test, and those with results indicative of moderate to severe depression were excluded from the study and referred to a psychiatrist. The tablets were given from the first trimester of pregnancy until delivery. Eighty‐three were randomised to each arm of the trial. Sixty‐one women completed the selenium arm, 44 of whom completed an EPDS test. Sixty‐four women completed the placebo arm of the trial, 41 of whom completed an EPDS test.

The second randomised controlled study (Mozurkewich 2013) compared docosahexanoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) with placebo. The trial randomised 126 women at risk of postpartum depression to three arms of the trial: 42 were allocated to EPA, 42 to DHA and 42 to placebo. Three women in the EPA arm, four in the DHA arm, and one woman in the placebo arm were lost to follow‐up. Women who were found to have major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, current substance abuse or dependence, suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, coagulation disorders, or known to have a multiple gestation at recruitment were excluded from the study. The women who discontinued the intervention (five in the EPA arm, four in the DHA arm and seven in the placebo arm) were included in the intention‐to‐treat analysis, while those who were lost to follow‐up were not. Women received supplements or placebo from recruitment at gestational age of 12 to 20 weeks until their final review visit at six to eight weeks postpartum. The primary outcome measure was the BDI score at the fifth visit (six to eight weeks postpartum).

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 studies. We have described reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We excluded some studies because they included only participants who were depressed at recruitment and hence were looking at treatment rather than prevention. We also excluded studies if at time of recruitment they did not exclude depressed women and hence had a mixed population of depressed and non‐depressed women. Furthermore, the proportion of women with depression at recruitment was high in these studies. It was the opinion of the review authors that including a mixed population of depressed and non‐depressed women would confuse the issue of prevention and treatment of postnatal depression.

Risk of bias in included studies

We described the risk of bias of the included studies in the ’Risk of bias tables’ attached to the Characteristics of included studies.

It was ascertained that the study Mokhber 2011 had a high risk of incomplete outcome data due to attrition of participants in the trial. Despite emailing the study authors for more information there was also unclear risk of bias with regard to allocation concealment. Risk of bias was deemed to be low in the areas of random sequence generation, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment and selective reporting. Another potential area of unclear risk of bias lies in the timing of the administration of the EPDS since true postnatal depression might be confounded with "baby blues" if one arm of the study had a larger proportion of women completing the EPDS during the first 10 days postpartum.

Mozurkewich 2013 had a low risk of bias in the areas of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, attrition, blinding of outcome assessment and selective reporting.

Effects of interventions

One included trial in this review (Mokhber 2011) compared daily supplementation with selenium tablets (100 µg) versus a placebo control.

The other included trial (Mozurkewich 2013) compared daily supplementation with EPA capsules with both supplementation with DHA capsules and placebo.

Selenium versus control

Primary outcome

Postnatal depression

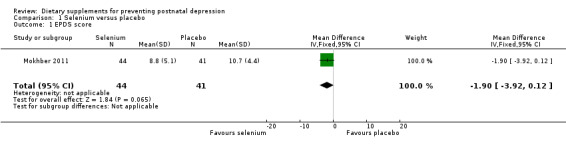

Self‐reported Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

In Mokhber 2011, selenium tablets had an effect compared with placebo on self‐reported EPDS scores in favour of a lower risk of postnatal depression among those women who completed their EPDS (mean difference (MD) ‐1.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.92 to 0.12), see Analysis 1.1. This effect has a P value of 0.07 and hence does not reach statistical significance.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Selenium versus placebo, Outcome 1 EPDS score.

Secondary outcomes

Mokhber 2011 did not report on any of our secondary outcome measures.

EPA versus control

Primary outcome

Postnatal depression

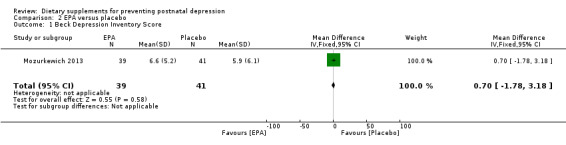

Beck Depression Inventory Score (BDI)

In Mozurkewich 2013, EPA had no significant effect on BDI scores compared with placebo on prevention of postnatal depression at six to eight weeks postpartum (MD 0.70, 95% CI ‐1.78 to 3.18) see Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 EPA versus placebo, Outcome 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score.

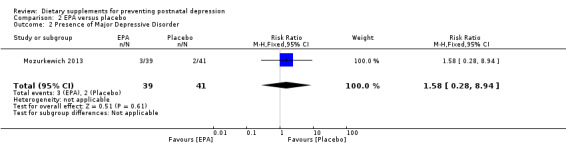

Secondary outcomes

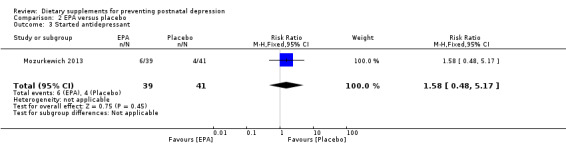

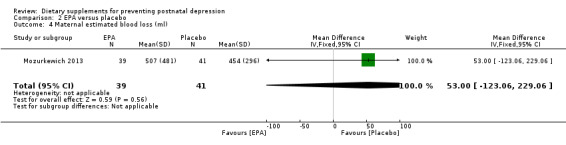

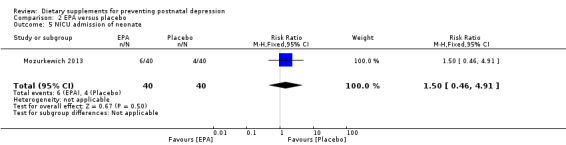

Mozurkewich 2013 looked at a number of secondary outcomes. Of the outcomes that are the subject of this review, in Mozurkewich 2013, none of the secondary outcomes showed a significant effect of EPA compared with placebo. In terms of rates of development of major depressive disorder (risk ratio (RR) 1.58, 95% CI 0.28 to 8.94) (Analysis 2.2); rates of commencement of antidepressants (RR 1.58, 95% CI 0.48 to 5.71) (Analysis 2.3); and estimated maternal blood loss at delivery (MD 53.00, 95% CI ‐123.06 to 229.06) (Analysis 2.4). For rates of neonatal intensive care admissions of the neonates (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.91) see Analysis 2.5.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 EPA versus placebo, Outcome 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 EPA versus placebo, Outcome 3 Started antidepressant.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 EPA versus placebo, Outcome 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 EPA versus placebo, Outcome 5 NICU admission of neonate.

DHA versus control

Primary outcome

Postnatal depression

Beck Depression Inventory Score (BDI)

In Mozurkewich 2013, DHA has no significant effect on BDI scores compared with placebo on prevention of postnatal depression at six to eight weeks postpartum (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐2.61 to 2.21) see Analysis 3.1.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DHA versus placebo, Outcome 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score.

Secondary outcomes

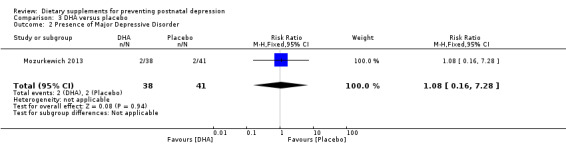

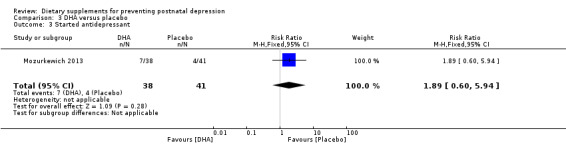

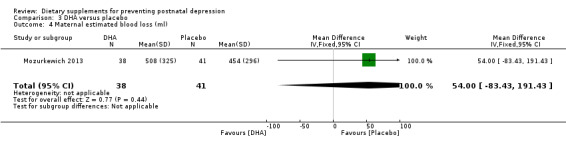

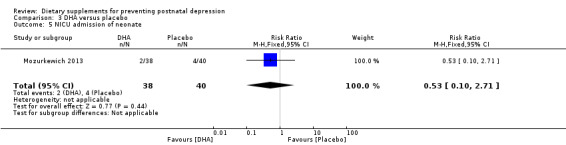

In Mozurkewich 2013, of the outcomes that are the subject of this review, none of the secondary outcomes showed a significant effect of DHA compared with placebo. In terms of rates of development of major depressive disorder (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.16 to 7.28) (Analysis 3.2); rates of commencement of antidepressants (RR 1.89, 95% CI 0.60 to 5.94) (Analysis 3.3); and estimated maternal blood loss at delivery (MD 54.00, 95% CI ‐83.43 to 191.43) (Analysis 3.4). For rates of neonatal intensive care admissions of neonates (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.10 to 2.71) see Analysis 3.5.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DHA versus placebo, Outcome 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DHA versus placebo, Outcome 3 Started antidepressant.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DHA versus placebo, Outcome 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DHA versus placebo, Outcome 5 NICU admission of neonate.

EPA versus DHA

Primary outcome

Postnatal depression

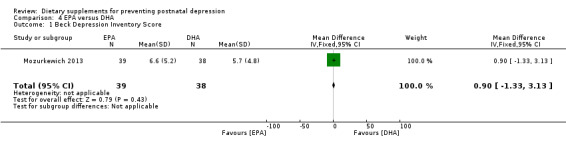

Beck Depression Inventory Score (BDI)

In Mozurkewich 2013, EPA has no significant effect on BDI scores compared with DHA on prevention of postnatal depression at six to eight weeks postpartum (MD 0.90, 95% CI ‐1.33 to 3.13) see Analysis 4.1.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 EPA versus DHA, Outcome 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score.

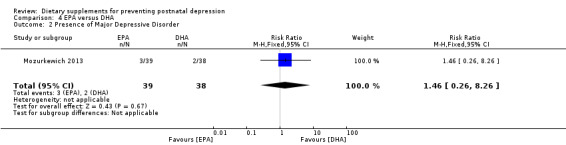

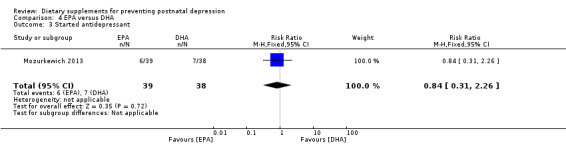

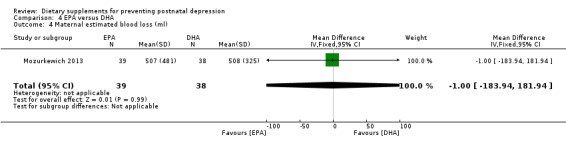

Secondary outcome

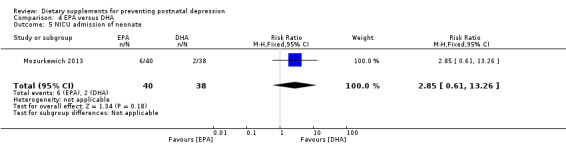

In Mozurkewich 2013, of the outcomes that are the subject of this review, none of the secondary outcomes showed a significant effect of EPA compared with DHA. In terms of rates of development of major depressive disorder (RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.26) (Analysis 4.2); rates of commencement of antidepressants (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.26) (Analysis 4.3); and estimated maternal blood loss at delivery (MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐183.94 to 181.94) (Analysis 4.4). For rates of neonatal intensive care admissions of the neonates (RR 2.85, 95% CI 0.61 to 13.26) see Analysis 4.5.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 EPA versus DHA, Outcome 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 EPA versus DHA, Outcome 3 Started antidepressant.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 EPA versus DHA, Outcome 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 EPA versus DHA, Outcome 5 NICU admission of neonate.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The study by Mokhber et al (Mokhber 2011), showed a favourable effect on mean EPDS scores in women in taking selenium 100 µg daily tablets compared with placebo for the prevention of postnatal depression. However this effect did not reach statistical significance.

Mozurkewich 2013 showed no significant effect of EPA or DHA on BDI scores compared with placebo. It also showed no significant effect of EPA or DHA compared with placebo on the secondary outcomes of rates of diagnosis of major depressive disorder, initiation of antidepressants, maternal estimated blood loss at delivery or neonatal intensive care admissions of neonates.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Mokhber 2011 does not provide enough evidence to meet the objectives of this review. As well as not giving a result that reached statistical significance, it also did not report on any of the secondary outcomes of this review.

A number of trials of omega‐3 fatty acids have now been performed but all have been excluded from this review because they included depressed women at recruitment. Mozurkewich 2013 is the first published study of omega‐3 fatty acids where depressed women are clearly excluded from recruitment. Its results have important implications for practice, even though no effect on postnatal depression was found. Given that the population of women being investigated was a group at risk of depression, it is surprising that the actual rates of women diagnosed with major depressive disorder across the three arms of the study (EPA 8%, DHA 5% and placebo 5%) or the number of women commenced on antidepressants (EPA 15%, DHA 18% and placebo 10% ) are lower than previously published rates in a population at risk of depression (25% to 68%, Dalton 1982; Wisner 2004). Perhaps if this study had continued further into the postpartum period higher rates would have been detected. It is possible a significant effect of the intervention could have been detected with more follow‐up visits into the postpartum period.

Many other potential interventions need to be studied. Among the excluded trials calcium (Harrison‐Hohner 2001) and iron for iron‐deficient anaemic mothers (Beard 2005) seemed promising but included both depressed and non‐depressed women at recruitment. Trials where women who are depressed at entry are excluded from recruitment would be needed for more evidence of a preventive effect. Many other dietary supplements are worthy of testing to see if they can prevent postnatal depression.

Quality of the evidence

Mokhber 2011 has a high risk of bias due to large numbers of attrition, both in the numbers that withdrew from the study prior to completion, and in those that completed the study but failed to complete their Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) test. It is also unclear how randomisation or allocation concealment was performed, or when in the postnatal period the majority of EPDS questionnaires were completed.

In addition, the report for this study suggests there was difficulty in ensuring participants were compliant with taking their supplements because of concerns that exist about taking supplements during pregnancy. Conversely, the report states that there was a statistically significant higher selenium concentration in the selenium‐supplemented group than the control group and this may imply that compliance was satisfactory.

Another strength and weakness of Mokhber 2011 is that it recruited a homogeneous population of women in Iran. While making the results more reliable they are less likely to be generalisable to other locations. The authors of this study recommend a larger multicentre trial.

Given the issues with this study, a robust conclusion regarding the efficacy of selenium for prevention of postnatal depression cannot be made.

Overall, Mozurkewich 2013 had a low risk of bias. It was a well‐designed study that followed its previously published protocol and there were low numbers of women who were lost to follow‐up. As postnatal depression can take up to 12 months postpartum to appear, one criticism of this study is that six to eight weeks postpartum may be too early to detect an effect of omega‐3 supplementation. Perhaps looking for the presence of depression at the time‐points of three‐ and six‐month postpartum may show more of an effect, particularly if the population being studied is breastfeeding. Another weakness of this study was that it had the statistical power to detect differences in depressive symptoms, but not in the diagnoses of major depressive disorder.

Potential biases in the review process

A potential source of bias of this review may originate from the search strategy. The search strategy utilised is more likely to detect English language publications. Efforts have been made to identify publications in languages other than English, however, it is possible that relevant publications have not been identified.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

No other studies of selenium for prevention of postnatal depression have been found.

The results of Mozurkewich 2013 are consistent with the findings of the study by Makrides et al (Makrides 2010), which found no benefit for DHA‐rich fish oil for prevention of depressive symptoms among women who were not selected based on predisposition for depression. They are also consistent with the study by Freeman et al (Freeman 2008), which found no additional benefit for EPA‐predominant fish oil compared with interpersonal psychotherapy alone. The findings of this study disagree with those of Su et al (Su 2008) and earlier studies by Freeman et al (Freeman 2006), which were suggestive of benefit. It has been suggested by Mozurkewich et al (Mozurkewich 2013) that one possible reason that the results differ from Freeman 2006 and Su 2008 is that lower doses of EPA and DHA were used in this study compared with the earlier studies. However, Freeman's dose‐ranging trial found that higher doses of EPA plus DHA were not more effective than lower doses (Freeman 2006)

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Only two studies were found that met our inclusion criteria.

One study looked at the effect of selenium supplementation for preventing postnatal depression (Mokhber 2011). However, there is insufficient evidence to make strong recommendations for or against the use of selenium in this population and there is no evidence regarding the use of any other dietary supplements in this population. The study also did not report on any of the secondary outcomes outlined in this review.

The other study comparing EPA and DHA to placebo showed no significant preventive impact on the presence of postnatal depression (Mozurkewich 2013). As a result of this study, omega‐3 fatty acids EPA and DHA cannot be recommended for prevention of postnatal depression. This is an important finding as there is considerable community interest regarding omega‐3 fatty acids.

Implications for research.

More randomised controlled trials are required to look at different dietary supplements for the prevention of postnatal depression. Selenium appears promising but more studies are required to confirm it has a clinically significant effect. Other dietary supplements need to be studied in trials where depressed women are excluded from entry to see if these trials prevent postnatal depression. In addition, the included study Mokhber 2011 reported mean EPDS scores of 8.8 (± 5.1) and 10.7 (± 4.4). This gives us an average number of reported depressive symptoms across a population rather than the actual number of women who have a diagnosis of depression. The literature suggests a range of cut‐offs for EPDS scores, most commonly, greater than 12 for probable depression and nine to 12 for possible depression (Gibson 2009). Dichotomous data of numbers in each group who meet the EPDS criteria for risk of depression would give a better indication of the clinical significance of an intervention.

Studies of omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation looking further into the postnatal period, particularly in breastfeeding women, would be useful since postnatal depression can take up to a year postpartum to present. Studies should aim to have the statistical power to detect differences in the number of women diagnosed with a major depressive disorder.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr Vicky Flenady and the Mater Research Support Centre (Mater Health Services Brisbane) in the initial development of this research question.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team) and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Selenium versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 EPDS score | 1 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.90 [‐3.92, 0.12] |

Comparison 2. EPA versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score | 1 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [‐1.78, 3.18] |

| 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.28, 8.94] |

| 3 Started antidepressant | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.48, 5.17] |

| 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml) | 1 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 53.0 [‐123.06, 229.06] |

| 5 NICU admission of neonate | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.46, 4.91] |

Comparison 3. DHA versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score | 1 | 79 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐2.61, 2.21] |

| 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder | 1 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.16, 7.28] |

| 3 Started antidepressant | 1 | 79 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [0.60, 5.94] |

| 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml) | 1 | 79 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 54.0 [‐83.43, 191.43] |

| 5 NICU admission of neonate | 1 | 78 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.10, 2.71] |

Comparison 4. EPA versus DHA.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Beck Depression Inventory Score | 1 | 77 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [‐1.33, 3.13] |

| 2 Presence of Major Depressive Disorder | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.26, 8.26] |

| 3 Started antidepressant | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.31, 2.26] |

| 4 Maternal estimated blood loss (ml) | 1 | 77 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐183.94, 181.94] |

| 5 NICU admission of neonate | 1 | 78 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.85 [0.61, 13.26] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Mokhber 2011.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Method of randomisation not described. Method of allocation concealment was not described. 218 assessed for eligibility. 39 were excluded or refused to participate in the trial. 179 were randomised to either 100 µg selenium tablets or matched placebo tablets. 13 were excluded after the first consumption of tablets due to intolerance to selenium tablets or bad smell of selenium tablets. 22 withdrew from selenium arm. 19 withdrew from the placebo arm. 61 completed the selenium arm of the trial. 64 completed the placebo arm of the trial. 44 from the selenium arm completed the EPDS test. 41 from the placebo arm of the study completed the EPDS test. Outcomes were serum selenium tests at baseline and at end of trial, and self‐reported EPDS after the end of the trial. |

|

| Participants | Iranian primigravid women aged 16‐35 years attending the Obstetrics and Gynaecology department of OM‐Albanin Hospital (Mashhad, Iran) between June 2006 and August 2008. Inclusion criteria were women gestational age up to 12 weeks with a live fetus, and with no serious physical or mental disease and no indications for terminating the pregnancy. Exclusion criteria were use of any drugs, but not routine supplementation of folic acid and ferrous sulphate, and occurrence of any severe disease or stressful life events according to the Holmes and Rahe stress scale. Also excluded were those women with intolerance to the tablets or the unpleasant aroma associated with the tablets and women with a BDI score greater than or equal to 31, indicating moderate to severe depression. |

|

| Interventions | 100 µg selenium yeast tablets or matched placebo yeast tablets were given daily. Selenium yeast tablets were provided by Pharma Nord, Vejle (Denmark). Tablets were given from the first trimester of pregnancy until delivery (approximately 6 months). |

|

| Outcomes | The mean serum selenium level (µg/dL ± SD) was measured pretrial and post‐trial. The self reported mean EPDS score (± SD) post‐trial for the selenium group was 8.8 ± 5.1 and for the placebo group post‐trial was 10.7 ± 4.4. |

|

| Notes | No power calculation reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Study authors were emailed. They replied that block randomisation was performed from a table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study authors were emailed. They replied that a person not involved in the trial placed and labelled the treatment and placebo boxes. However, no specific information regarding allocation concealment was given. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Personnel | Low risk | Study authors were emailed. They replied that both personnel having contact with participants and participants were blinded as to treatment and placebo. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Participants | Low risk | Participants received either selenium yeast tablets or matched placebo yeast tablets in identical packaging as this is a double‐blind design. Provided the taste of the tablets was the same and there are no obvious side‐effects to this dosage of selenium then there would be a low risk of unblinding. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Outcome of Self reported EPDS | Low risk | If women were aware they received the intervention (selenium) rather than placebo this might introduce a significant risk of bias on the outcome assessment (self‐reported EPDS). However, it is our judgement that this would be unlikely and hence there is a low risk of bias for this outcome assessment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Self‐reported EPDS | High risk | Missing outcome data are balanced across intervention groups. Similar numbers of women withdrew from treatment for similar reasons. Reasons are given for why women withdrew from treatment. However, no reasons are specified for why so many women failed to complete their EPDS test, although similar numbers failed to complete the EPDS in each treatment group. No mention is made regarding whether an attempt was made to impute data for the women who failed to complete the EPDS but had completed the trial into the EPDS mean calculation. The numbers of women that failed to complete their EPDS is such a high proportion of the participants that this could have a high risk of introducing bias. Approximately half of the women either withdrew from the study or failed to complete their EPDS in both arms of the study. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | With regard to postnatal depression, this article only provides continuous data with a comparison between the mean score for EPDS between selenium and control group as a primary outcome measure. It would have been possible for dichotomous data to be presented with for example numbers of women with an EPDS ≥ 13 (indicating they were at risk of depression). This may have given an indication of whether selenium has a clinically significant effect as well as a statistically significant effect on postnatal depression. At this time these data are not yet available from the study authors, but we are seeking it. Otherwise, this appears to have a very simple trial design and it is our judgement that the published report includes all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified, even though the study protocol is not available. The study authors have stated in an email that the trial did not deviate from outcomes listed in the original University ethics application. |

Mozurkewich 2013.

| Methods | This was a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomised controlled trial to assess whether omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation prevents antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among pregnant women at risk for depression. The plan was to recruit 126 pregnant women at less than 20 weeks' gestation from prenatal clinics at 2 health systems in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the surrounding communities. They were followed prospectively over the course of their pregnancies and up to 6 weeks postpartum. | |

| Participants | The women participating in this study were receiving prenatal care at 2 health systems in southeastern Michigan, the University of Michigan Hospitals and Clinics and St Joseph Mercy Health System/Integrated Health Associates. These health systems are located in Ann Arbor, Michigan and Ypsilanti, Michigan and the surrounding communities. Women were 18 years of age or older, have a confirmed, live, intrauterine pregnancy of greater than 12 weeks' gestation but less than 20 weeks' gestation, and be enrolled in prenatal care at 1 of the 2 participating health systems. They must have been planning to deliver at 1 of the 2 participating hospitals and plan to remain in the southeastern Michigan area through 6 weeks after delivery. To qualify for the study, women must be at risk for depression, based on (i) a history of MDD, (ii) a history of postpartum depression, or (iii) an EPDS score between 9 and 19. Women were excluded from participating in the study if they were currently taking an omega‐3 fatty acid supplement; taking antidepressant or other psychiatric medications; using therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulation medication; or consuming more than 2 fish meals per week. In addition, pregnant women with a diagnosis of current major depressive disorder, or other psychiatric diagnoses, including current substance abuse, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder were excluded from study. Pregnant women with known multiple gestation or a history of bleeding disorder such as von Willebrand’s Disease were also to be excluded. |

|

| Interventions | Enrolled participants were randomised to 1 of 3 groups: a) EPA‐rich fish oil supplement (1060 mg EPA plus 274 mg DHA); b) DHA‐rich fish oil supplement (900 mg DHA plus 180 mg EPA; or c) a placebo. | |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome for this study was the BDI score at 6 weeks postpartum. Secondary outcome measures include: omega‐3 fatty acid concentrations in maternal plasma and cord blood, pro‐inflammatory cytokine levels (IL‐1b, IL‐6, and TNF‐a) in maternal and cord blood, need for and dosage of antidepressant medications, and obstetrical outcomes. | |

| Notes | Plan was to randomise 126 women to have 80% power to detect a 50% reduction in participants’ mean BDI scores with EPA or DHA supplementation compared with placebo. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was carried out using a random number table maintained in the University of Michigan investigational drug service. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The research team provided the investigational drug service staff with a list of unique identifying numbers prior to the start of recruitment. At the time of randomisation the research team informed the investigational drug service staff of the study identification number of each participant to be randomised. The investigational drug service staff then randomised participants to 1 of 3 study arms using a random number table: intervention #1, intervention #2 or placebo and will maintain randomisation records until the last participant has completed the protocol. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Personnel | Low risk | The research team was blinded to the results of randomisation. The supplements or placebo were dispensed by the investigational drug service and hence the research team had no way of knowing which participants received intervention or placebo. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Participants | Low risk | Placebos were formulated to be identical in appearance to both DHA and EPA rich supplements, and contained 98% soybean oil and 1% each of lemon and fish oil. A double‐dummy design was used to maintain blinding as EPA and DHA containing capsules were different sizes. Hence each participant received 4 small capsules and 2 large capsules, regardless of which arm they were randomised to. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Outcome of Self reported EPDS | Low risk | The research team was blinded to the results of randomisation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Self‐reported EPDS | Low risk | Small numbers were lost to follow‐up in each arm: EPA n = 3, DHA n = 4, placebo n = 1. These were not included in the intention to treat analysis. There were no significant differences between randomised groups in measures of adherence. Results of participants who discontinued the intervention but were not lost to follow‐up were included in the intention to treat analysis (EPA n = 5, DHA n = 4, placebo n = 7). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The outcomes discussed in the protocol appear to be addressed in the final paper. |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid IL: interleukin µg: microgram TNF: tumour necrosis factor

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Beard 2005 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Doornbos 2009 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Dunstan 2003 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Freeman 2004 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Freeman 2006 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Freeman 2007 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Freeman 2008 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Freeman 2010 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Harrison‐Hohner 2001 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Llorente 2003 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Makrides 2010 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded from the study. |

| Rees 2008 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

| Smith 2007 | Participants with depression at time of recruitment were not excluded. |

| Su 2008 | All participants had depression at time of recruitment. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Judge 2011.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | 52 women between 24 and 40 weeks of pregnancy. |

| Interventions | Placebo (corn oil capsule) or DHA (300 mg DHA fish oil capsule). 26 women were assigned to each group for consumption 5 days per week between 24 and 40 weeks of pregnancy. |

| Outcomes | Postpartum depression symptoms were assessed at 2 and 6 weeks, and at 3 and 6 months with the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. There was a significant group difference (P = 0.0057) for the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale between the 2 groups. Compared with controls DHA was associated with a consistent 6‐point lower mean depression score across all time points. |

| Notes | This was a meeting abstract only. Have made contact with study authors and emailed study authors seeking more information but have not received all the required information to classify this study. |

DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid

Contributions of authors

Brendan Miller was the main author of this protocol and is the guarantor of the review. Bonnie Macfarlane assisted with the initial registration of the title and defining of the question being addressed. Linda Murray, Michael Beckmann and Terry Kent provided assistance with the main body of the protocol and with editing the protocol.

Brendan Miller and Terry Kent selected eligible studies from those identified in the search strategy and they completed the 'Risk of bias' assessment. Michael Beckmann and Linda Murray provided advice on the inclusion of eligible studies. Brendan Miller and Terry Kent performed data extraction from the one included study. Brendan Miller and Linda Murray performed the data analysis. Linda Murray provided Brendan Miller assistance with editing the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

RANZCOG research foundation, Australia.

The contact author (Brendan Miller) of this Cochrane review received a grant of $500 from the RANZCOG research foundation which he used to partly fund his attendance at a Cochrane review completion workshop in Melbourne, Australia in May 2012

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Mokhber 2011 {published data only}

- Mokhber N, Namjoo M, Tara F, Boskabadi H, Rayman MP, Ghayour‐Mobarhan M, et al. Effect of supplementation with selenium on postpartum depression: a randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2011;24(1):104‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mozurkewich 2013 {published data only}

- Mozurkewich E, Chilimigras J, Klemens C, Keeton K, Allbaugh L, Hamilton S, et al. The mothers, Omega‐3 and mental health study protocol. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2011;11:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozurkewich E, Clinton C, Chilimigras J, Hamilton S, Allbaugh L, Berman D, et al. The Mothers, Omega‐3 & Mental Health Study: a double‐blind, randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013;208(1 Suppl):S19‐S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]