Abstract

The experience of prolonged stress changes how the individual interacts with its environment and processes interoceptive cues, with the end goal of optimizing survival and well-being in the face of a now-hostile world. The chronic stress response includes numerous changes consistent with limiting further damage to the organism, including development of passive or active behavioral strategies and metabolic adjustments to alter energy mobilization. These changes are consistent with symptoms of pathology in humans, and as a result chronic stress has been employed as a translational ‘model’ for diseases such as depression. While of heuristic value to understand symptoms of pathology, we argue that the chronic stress response represents a defense mechanism that is at its core adaptive in nature. Transition to pathology occurs only after the adaptive capacity of the organism is exhausted. We offer this perspective as a means of framing interpretations of chronic stress studies in animal models and how these data relate to adaptation as opposed to pathology.

Keywords: Chronic social defeat, chronic unpredictable stress, animal model, stress resilience, stress inoculation, allostasis

Stress is part of everyday life. It is hard to imagine a life without regular challenges, be they externally imposed or generated by our own perceptions of threat or adversity. Most individuals can effectively handle life’s stressors, as we have highly evolved adaptive mechanisms to limit their physiological or psychological impact. However, in a minority of the population, traumatic or cumulative stressors can contribute materially to the development of psychiatric disease. The presumptive relationship between stress and disease is often the core premise driving stress research. We feel that the disease-focused approach to stress research does not give due consideration to the possibility that many if not all laboratory animal stress models better represent adaptation than pathology (1-4). In this review, we discuss the importance of considering chronic stress responses as attempts of the organism to adapt to a now-threatening world, rather than a prima facie manifestation of a pathological process.

I. What is chronic stress?

Stress is an inferred state and is thus hard to unambiguously define. For the purposes of our discussion, we consider stress as a multi-system response to any challenge that exceeds or is perceived to exceed the regulatory capacity of the individual. Stressors are stimuli usually associated with unpredictable and/or uncontrollable environmental or internal conditions that evoke this response. The physiological stress response involves the co-opting of metabolic regulators (e.g., sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal, or HPA, axis) to prepare the organism for flight or fight and redistribute resources in the event of prolonged adversity. The brain is the key organ in the orchestration of these responses, processing multi-modal sensory information to coordinate behavioral and metabolic changes accordingly. All these responses (if appropriately deployed) are critical for adaptation and survival.

It has been known since the time of Selye that chronic stress is not acute stress writ large. Indeed, Selye described a recovery phase as part of his General Adaptation Syndrome, where persistent (chronic) stress does not continuously engage responses observed in the initial, acute phase (5). McEwen and Stellar applied the concept of allostasis to describe an inherent underlying drive of effector systems that occurs in the face of chronic stress as a means of adaptation (6, 7). Under stressed conditions the organism can alter set points for homeostatic parameters to meet emergent or anticipated demands, constituting ‘allostatic load’. In each of these formulations of chronic stress, the outcomes have direct pathological consequences and can elicit symptoms of psychiatric and systemic diseases. Nevertheless, in both models there is a large intermediate area where the individual’s adaptive capacity can meet the environmental conditions without manifesting dire physical pathology. It is this space where the organism adapts appropriately to meet environmental demand.

Consider the myriad changes that occur during prolonged stress exposure. In rats and mice, chronic stress causes physiological changes that reflect readiness for subsequent challenge in a now-hostile world: improved glucose metabolism (8-10), faster and more pronounced glucocorticoid and autonomic responses to new stressors (see 11, 12), and diminished engagement in metabolically expensive processes such as growth or reproduction (13-15). Chronic stress-induced behavioral changes include enhanced risk aversion (e.g., anxiety related behaviors) (16, 17), increased passive coping (18, 19), and reliance on habitual behaviors that have predictable outcomes (20, 21), all of value in a newly unpredictable environment. Recovery from chronic stress is dependent on the organism’s new perception of the world, involving learning that the environmental threat is gone while also retaining memory of the stress experience, i.e., being prepared for future adversity. Such would likely entail prolonged absence of stress or reminder cues and depend on stressor severity, frequency, and duration.

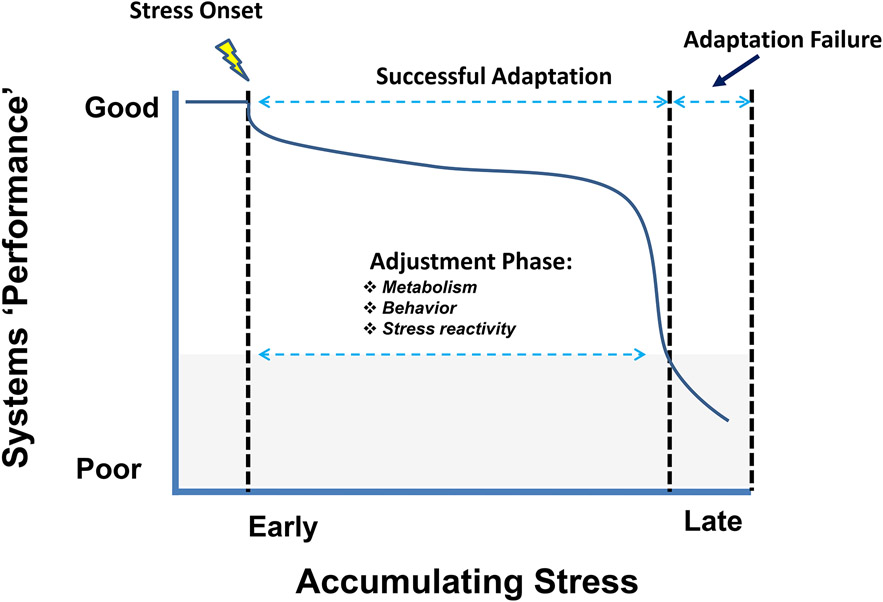

Our conceptual framework for progression of chronic stress is illustrated in Figure 1. Chronic stress initiates adjustments that are designed to minimize potential future threats to physical or psychological security. Whereas initial responses to stress enlist systems that mobilize and redistribute metabolic resources, the period thereafter involves an adjustment phase, where physiology and behaviors are modified to react to real or predicted challenges accompanying repeated stress. Long-term adaptive responses are clearly observed in most paradigms: habituation occurs with repeated and predictable exposure to the same (homotypic) stressor, and response sensitization occurs upon exposure to new (heterotypic) stressors.

Figure 1.

From adaptation to pathology: progression of chronic stress. The y-axis reflects systems performance of the organism as a whole, and x-axis reflects net stress exposure (a product of stressor severity and/or chronicity of exposure). Following initiation of chronic stress, the organism enters into an adjustment period where behavior and physiology are modified in an attempt to meet the continuing challenge. For example, switching to conservative behavioral choices to limit exposure to danger and energy expenditure. Prolonged or intense stress exposure may eventually degrade systems performance and drive development of pathology, resulting in an adaptation failure which can be defined as a situationally inappropriate behavioral or physiological response (denoted by the gray shaded area)

Pathology can result when stress exposure(s) exceed the capacity for behavioral and physiological reactive mechanisms to engage, causing situationally inappropriate responses that place the individual in danger of physiological decline or psychological duress. Nevertheless, chronic stress responses in rodents are often equated with pathology, with the constellation of reactions interpreted as underlying maladaptive physiology and/or behavior. In this article, we challenge this assumption by arguing that such changes are largely adaptive for the organism. Equating stress with pathology ignores the potential survival benefit of these responses, and obscures how we interpret behavioral and physiological findings with respect to disease processes. We follow with several considerations in order to stimulate thinking about how to better translate what we can learn from chronic stress models to an understanding of human disease.

II. Chronic stress models: relationship to disease phenotypes

Chronic stress models typically involve repeated exposure to one or multiple challenges over many days, or involve a single, prolonged sequence of challenges that produce protracted behavioral or physiological responses (18, 22-25). Often chronic stress studies are designed with a specific disease-related endpoint in mind, invoking direct comparison with features of human psychiatric illnesses, or they focus on the extent to which drugs (antidepressants) can reverse the incipient phenotypes that develop throughout the course of exposure. Great strides have been made in demonstrating that various chronic stress models produce behavioral similarities to common psychiatric diseases (e.g., 26, 27, 28). Nevertheless, they still rest on the assumption that such responses in the laboratory are maladaptive, or contribute to the development of pathology in humans. While the utilization of chronic stress in rodents remains a necessary and invaluable approach to model features of psychiatric diseases, the field has not yet come to grips with the likelihood that responses following chronic stress are in fact adaptative. Below, we consider two of the more prevalent chronic stress models in the field, and discuss the relevance of their features in the context of adaptation and pathology.

One prominent example is chronic unpredictable stress (CUS; a.k.a., chronic variable stress, chronic unpredictable mild stress) (21-24, 29). In this model, rodents are subjected to a number of different stressors once or twice daily over a period of weeks. The CUS model produces a range of behavioral, endocrine, and physiological features that can parallel symptoms of psychiatric disorders. These effects include, but are not limited to, anhedonic-like impairments in tests of reward, weight loss/reduced weight gain, disrupted sleep patterns, decreased locomotor activity, increases in HPA and some cardiovascular indices, diminished interaction with conspecifics, increased anxiety-like behavior, tendency toward passive coping, a bias toward habit-based versus goal-directed learning, greater threat generalization (e.g., 18, 21, 22, 29-33). Antidepressants may alleviate or rescue many of the features produced following CUS, further suggesting relevance of stress-induced behavioral changes to symptoms of psychiatric diseases.

It can be argued that these physiological reactions represent adaptive responses and are situationally appropriate (are in the adjustment phase of stress reactivity), rather than indicating the development of pathology (Fig. 1) (34, 35). For example, many of the chronic stress-induced behavioral changes exhibited by rodents represent a broad strategy toward minimizing risk and reducing threat exposure (11, 36). These occur as one of many adjustments that are necessary to limit potential threats to homeostasis or well being that are associated with stress exposure(s). Moreover, responsiveness to antidepressant drugs may not reflect only their ability to reverse chronic stress outcomes, they also may reduce reactivity to the chronic stress exposure regimen itself (e.g., 37, 38, 39). Antidepressants may increase hippocampal neurogenesis in the absence of chronic stress (40), and some evidence even suggests that responses designated as “antidepressant” in humans may be recapitulated in the absence of depressive illness (41-43).

In parallel with the growing appreciation that many experiencing chronic stress do not necessarily go on to develop psychiatric disease (44, 45), animal models have been cultivated to better understand individual variability in stress responsiveness (46, 47). Strain, behavioral, genomic, and naturally occurring phenotypes have been identified as factors confering differential responsiveness to chronic stress exposure (46, 48-51). In perhaps the most widely used behavioral model, chronic social defeat (CSD), mice are subjected to physical subordination by exposure to an aggressive resident several minutes daily for 7-10 days (46, 52). In each of the intervening periods throughout the duration of the paradigm, mice are housed with the aggressive male through a clear perforated divider shared in the home cage. Thereafter, a large enough cohort of mice display a bimodal shift in a social interaction task, whereby “resilient” and “susceptible” mice are distinguished by interaction scores higher or lower than those of previously unstressed mice. This selection method recapitulates a number of symptoms seen in CUS and related models, with greater anhedonic- and habit-like responses, and weight decreases, in susceptible versus resilient animals. Post-CSD phenotypes also exhibit a profound array of changes in the CNS, in terms of transcriptional profiles, neuroimmune, and vascular alterations (53-56). That brain tissue from susceptible mice and post-mortem psychiatric patients display similar neurobiological features lends support for the CSD model in recapitulating aspects of human pathology (26-28).

One lingering issue with the CSD model concerns the lack of verification of whether differences exist in the engagement of metabolic regulatory systems between resilient and susceptible mice. For example, the existing data indicates that HPA features of the stress response remain similar in susceptible and resilient mice (e.g., see 46, 57), and autonomic profiles have yet to be carefully considered (46, 57-59, cf. 60). These biological systems provide an index for how efficiently the animal is utilizing metabolic resources under basal conditions and also in responding to subsequent challenges (36), and they provide additional insight into the animal’s interoceptive state (61, 62). As the field has seen a renewed interest in understanding how dysregulation of internal bodily systems contribute to the pathophysiology or pathogenesis in stress-related psychiatric diseases (e.g., 61, 62, 63, 64-67), it will be helpful to give more careful consideration of the constellation of physiological and neuroendocrine features in susceptible and resilient phenotypes.

The vast majority of work on chronic stress has been performed in male rodents. Nevertheless, given that there are sex differences in vulnerability to psychiatric disease in humans, there has been greater interest in validating models in female rodents (68). Work using chronic unpredictable stress models indicate that females are relatively resistant, requiring longer stress exposures to manifest physiological and behavioral changes observed in males (69, 70). Social defeat is difficult to test in females, as inter-individual aggression is not normally observed. Some manipulations have been used to drive aggression in females that allow testing of the impact of social defeat, but generally this has not revealed as strong behavioral phenotypes typical of susceptible and resilient males (71, 72). Difficulties with establishing robust chronic stress models in female rodents suggest that either females are generally more resistant to chronic stress, or that we lack an understanding of what is sufficient to drive chronic stress responses in females. We believe the latter is most likely, as females occupy a very different ethological niche than males ( priority on reproduction and maternal behavior), females have a very different physiology in terms of a smaller body size and negligible body fat, and as a rule engage more in nonaggressive same-sex social interaction. Indeed, social isolation may differentially promote the development of clearer stress phenotypes in females vs. males (73-75), suggesting that females show greater stress reactivity to social instability. Moving forward, there is a clear need for standardization and adoption of validated behavioral tests sensitive to chronic effects in females.

Another perspective on utilizing chronic social defeat stress models involves broadening the scope to consider the possibility that both types of response variability may differentially inform disease susceptibility (64). The underlying principle is that susceptibility and resilience would be operational as based upon how well the particular phenotype expressed after chronic stress matches with the perceived environmental demands. Past work examining a variety of species has differentiated individuals based on active/ proactive and passive/ reactive patterns that encompass distinct behavioral, endocrine, and physiological features of stress responses (48, 76-79). Active and passive subtypes are typified by differences in aggressiveness, exploration, avoidance, and behavioral flexibility (34, 80, 81). Thus, the interpreration of passive/ susceptible phenotypes for modeling psychiatric disorders may only be telling half of the story. Rodents exhibiting active strategies may undergo cardiac and hypertensive changes that could translate to increased susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases (48, 64, 82-84). Additional evidence suggests that the active subtypes demonstrate higher rates of aggressive and perseverative behavior that may provide a basis for modeling other types of psychiatric disorders (85-88).

We emphasize that behavioral changes occurring in response to chronic stress have relevance to disease symptoms in humans, even if they reflect an adaptive response in the animal model. For example, it is not a stretch to consider that behaviors observed following CUS or social defeat (e.g., threat avoidance, passive coping) may mimic mechanisms underlying behavioral symptoms of affective disorders in humans— similar circuits are engaged, and similar neurotransmitters are implicated. The key distinction is the context of the behaviors being observed; rodent models do not reflect underlying pathology or ‘maladaptation’ yet do afford glimpses into mechanisms that may be engaged in pathological processes. Along these lines, characterization of chronic stress models has done well to highlight the constellation of features – behavioral, physiological, and endocrine- that typify stress-related diseases. However, with few exceptions (e.g., 33, 89), the field has been slow to address the neurobiological bases for how the constellation of response features are dysregulated after chronic stress exposure. Moving forward, it will be important to use combinatorial approaches to elucidate the neural intergration across behavioral, physiological, and endocrine alterations produced by chronic stress. This perspective will offer deeper insight into understanding stress-related psychiatric diseases that may be typified by varying degrees of autonomic or hormonal dysregulation whereas behavioral phenotypes may otherwise appear similar.

III. Chronic stress models: evolutionary considerations

The chronic stress response is a highly conserved process enabling organisms to cope with a range of environmental challenges involving exposure to predators, competition with other conspecifics, infections, climate, and resource availability (76, 90-92). The danger here is to assume that a change in a specific behavior is maladaptive on the basis of similarities with a particular translational endpoint, rather than considering their implications for the health and vitality of the individual. Such interpretations that equate behavioral outcomes (symptoms) following chronic stress in one species with a pathology in another, risks confirmation bias and disregards the implications if they are in fact adaptive responses.

It is of value to consider the significance of response variability following chronic stress exposure from an evolutionary perspective. There is an extensive amount of neurobiological information available regarding resilient and susceptible phenotypes. We posit that divergent phenotypes may confer differential fitness depending on specific environmental demands (1, 80, 85). The assumption that one type of response is pathological for a significant cross-section of individuals raises the quandary of how such a fitness disadvantage would not impact fitness at the population level. indeed, It is likely that response variability is built into the species to confer overall fitness, as changing environmental conditions may yield different selection pressures over time, favoring one behavioral extreme over another (e.g., see 76, 90, 91). For example, an avoidant phenotype may be better suited to environments with high predator desnity, whereas exploratory phenotypes may be favored in when resources are scarce. Some studies suggestthat divergent phenotypes in the CSD model are not resultant of the stressor per se, but reflective of different underlying tendencies toward exploratory and avoidance learning behaviors (3, 93). Other studies note that subtypes classified as resilient following social defeat perform better in social interaction and tests of anhedonia (46), yet have slower rates of acquisition and extinction in learning paradigms (94, 95), display higher aggression (85), and are prone to cardiac arrhythmias (81, 96). Indeed, studies housing rats in a colony environment (visible burrow system) demonstrated that individuals that engage the dominant fare worse than submissive individuals, exhibiting more wounding, loss of lean body mass, HPA axis hypoactivity and enhanced passive coping in the forced swim test. This indicates that interactive tendencies of an individual may have different consequences when interactions occur over a more protracted time frame (97). In a series of classic studies, Henry and Stephens (34) recognized two distinct physiological response patterns in mice on the basis of their social conflict behaviors, whereby the tendency to win or lose agonistic encounters was associated with respective higher levels of sympathetic activation or HPA responses, respectively. This partitioning yields behavioral coping phenotypes typified as active or passive and each considered to have adaptive value for the species at the population level (76, 80).

Consideration of trait or phenotypic variability in chronic stress models will help to better inform disease relevance for humans. It is important that investigators take caution in distinguishing between homologous and analogous features when making comparisons between rodents and humans, especially in determining the criteria for designating resilience. Indeed, chronic stress models remain a vital tool for elucidating the behavioral and physiological features that are prevalent or are associated with vulnerability for a specific disease. Nevertheless, our ability to distinguish adaptation from pathology relies on a more careful accounting of the teleological context in which they occur.

IV. Chronic stress, adaptation and pathology

We take the position that pathology in human (or in experimental animals) relates to engagement of stress responses, or a lack thereof, in the absence of an appropriately strong stress signal. The types of behaviors observed in human disease may reflect normally ‘adaptive’ behaviors occurring without precipitant causes. Social withdrawal behavior may be critical for survival during times of challenge but is less appropriate for safe environments. For example, social aversion seen in PTSD (DSM5) can occur in the absence of a discrete causal event, resulting in a misplaced behavior that would be considered maladaptive or pathological. In rodents, stress models generally produce in-context responses, e.g., the environmental challenge is real and thus the response is appropriately expressed.

There is a relationship between chronic stress and pathology, keyed mainly to factors related to intensity and/or duration. Nonetheless, individuals can adapt successfully across a wide range of stress intensity and duration, while undergoing physiological and behavioral changes that adjust to the prolonged or intermittent stressor exposure. We argue that the majority of changes seen during most chronic stress regimens represent attempts to adapt to an adverse environment, and fall with in the range of adjustment (Fig. 1). For example, rats undergoing chronic variable stress evince enduring decrements in body weight gain, increased stress hormone release and expression of cautious behaviors (reduced threat assessment, increased passive coping responses), but do not show frank morbidity/mortality and exhibit the capacity to normalize physiological adjustments following stress removal. Nonetheless, prolonged severe stress exposure can lead to adaptation failure, e.g., adrenal exhaustion, severe weight loss (98, 99), learned helplessness (100, 101), where the adjustments made by the organism are insufficient to maintain homeostasis or psychological integrity.

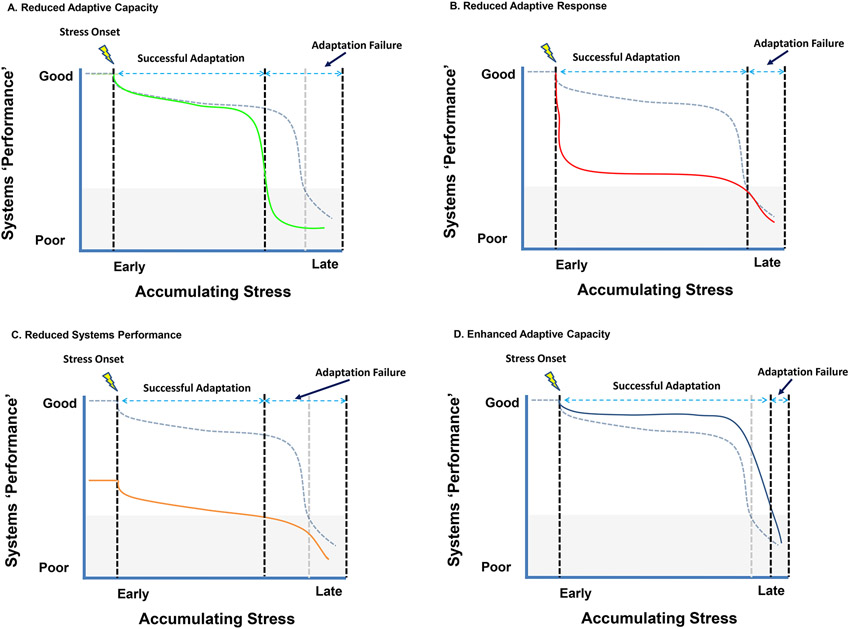

The ability (or inability) of an organism to elicit adaptive responses (defined as a situationally appropriate physiological or behavioral reaction) is likely a product of genetic predispositions and experiences. A predispotion toward stress susceptibility (e.g., an ‘anxiety’ bias driven by early-life stress) may limit the ability to appropriately adapt to stress, resulting in an inappropriately low adaptive capacity and manifestation of ‘pathological’ responses (Fig. 2A). A similar case may be made when appropriate physiological or behavioral recovery from the initial stress is not expressed, again resulting in inappropriately pronounced stress reactivity even in the adaptive phase (Fig. 2B). Enhanced transition to pathological responding may also be associated with conditions that diminished the adaptive reserves of the organism, as may occur with aging or physical disease (Fig. 2C). In these cases, behavioral or physiological dysregulation occurs at levels of stimulation that are normally insufficient to do so, creating responses that exceed (or undershoot) those required for efficient coping.

Figure 2.

Individual differences in stress adaptation likely dictate the amount of stress exposure that can be tolerated. Reduced adaptative capacity (A) may be associated with early exhaustion of stress coping mechanisms, likely a product of gene X environment interactions. A reduced adaptive response (B) would cause more severe reactions fo stressors exposure, resulting in degraded systems performance but not frank pathology. Factors such as age or disease may effectively reduce the total reserve capacity of the organism (C), also resulting in enhanced pathological responses. Finally, in some cases response capacity may be enhanced (D), for example by exposure to stressors earlier in life.

It is important to also consider whether aberrant behavioral or physiological responses are truly pathological or represent a reinterpretation of the context in which behaviors are tested (i.e., with the salience of the testing situation determined by memory of past stressors). The key here is understanding that the behavioral and physiological responses seen as evidence of ‘pathology’ are in fact part of the adjustment process. We posit that pathology occurs when the adjustments being made during stress exposure are insufficient to meet the demands placed on the organism. Some individuals may be less well suited for adaptation than others, driven by reduced capacity to make effective adjustments and/or more rapid exhaustion of resources.

Chronic stress may also be beneficial, paradoxically promoting health benefits as opposed to pathology (Fig. 2D). The positive value of chronic stress is supported by substantial evidence that exposure to certain types of stress, particularly in sensitive periods of life, may have lasting benefits. For example, limited nesting and bedding during the juvenile period in mice blocks stress-induced increases in HPA axis activation and anxiety-related behaviors following exposure to chronic social defeat or social isolation measured during adulthood (102, 103). Similarly, rats experiencing CUS in adolescence are resistant to a later ‘second hit’ of stress exposure during adulthood, reversing the negative effects of the second stress exposure on emotional memory (104, 105). Intermittent maternal deprivation also has beneficial effects in primates (squirrel monkeys), reducing the cortisol rise and object avoidance following exposure to novelty (106). The benefits of early life stress in primates are dependent on the intensity of the stressful experience, with milder stress exposures producing resilience (91). These data are congruent with studies in human, showing links between pathology and multiple adverse childhood experiences. Thus, positive effects of stress on resilience likely depend on the severity and frequency of exposures and when they occur.

While early life stress exposures can cause lasting changes in physiology and behavior in the face of subsequent stress later in life (107, 108), there appear to be health benefits to chronic stress exposure during adulthood (93, 109-112). Clinical-based approaches involving intermittent exposure to mild stressors are consistent with evidence that spontaneously occurring stress may have beneficial consequences. For example, stress inoculation is a therapy- or training-based approach that has been widely used in occupations where functioning under adversity is necessary, such as law enforcement, military, and medical fields (e.g., 113, 114-117). Analogous regimens have been recently applied in the laboratory in adult squirrel monkeys and mice (93, 110, 111). The development of stress inoculation assays in laboratory animals provides a strong scientific premise that may be more viable for modeling features of stress resilience than what is currently used in the field.

V. Consideration for future studies

Our analysis of the chronic stress literature suggests that chronic stress responses are physiological and behavioral adjustments designed to help the organism effectively adapt, and that are subject to trait or state variations in strategy that confer fitness for the individual. We emphasize that a key feature distinguishing adaptation and pathology is the context in which they occur. Adaptive responses occur in the context of stimuli that signal challenge or threat, which is the case in most laboratory animal models. In pathological states, the same (or closely related) responses occur in the absence of appropriate evocative stimuli, generated by either aberrant drive of response under unstressed conditions or misinterpretation of the significance or valence of environmental cues (118-120). Importantly, the mobilization of stress responses in pathological conditions supports use of laboratory animal stress models to understand pathways and mechanisms controlling responses measured (but NOT the disease itself). This allows translation of, e.g., neurobiological findings into understanding the basis of inappropriate response, which can (and are) being leveraged to advancement of treating disease symptoms or presumptive causes.

Based on our reading of the literature, we recommend re-centering interpretations of laboratory chronic stress responses to encompass the distinction between adaptation and pathology. Attribution of pathology following chronic stress in rodents contributes to the disconnect between human and laboratory animal research, and perfroms a disservice to efforts to use preclinical approaches to understand symptoms and processes underlying human disease conditions. Specific considerations include:

Behavioral extremes (active/proactive vs. passive/reactive styles) seen under chronic stress may be best thought of as alternative strategies for adaptation. Whereas proactive strategies provide resilience under some conditions (e.g., during social conflict/defeat), they may be detrimental in others (e.g., high predator density).

In come circumstances chronic stress can actually improve long-term adaptation, by limiting responses of the organism to stimuli that engendered successful adaption in the past.

Chronic stress and pathology recruit similar neural and behavioral processes. In the case of stress, the processes engaged are appropriate for adapting to adverse conditions. In the case of pathology, circuits and systems normally responsive to stress are inappropriately triggered, resulting in ‘ectopic’ responses that are ill-suited for survival or well-being.

The ability to effectively manage stress is likely a product of a combination of genetic predispositions and the organism’s prior experience, and requires active engagement of mnemonic processing to match environmental/physical adversity and context.

And finally, commonalities between animal studies and humans can be used to inform basic mechanisms of disease. The processes underlying withdrawal behavior during adaptation may very well mimic the out-of-context responses seen in human disease, and thus serve as a springboard toward developing approaches to address correction of the behavior.

Overall, chronic stress models can provide valuable information regarding processes that drive both adaptation and pathology. Understanding the importance of context is critical for differentiating the two. Rather than driving pathology, chronic stress responses are engaged under conditions where pathology exists. Realizing that most stress models represent normal adaptation processes is important for framing our understanding of behavioral and physiological consequences of stress and provides perspective on how these responses contribute to pathology when inappropriately engaged.

Acknowledgments:

Supported by MH119814 (JPH), MH127835 (JPH), BX005923 (JPH), and MH119106 (JJR).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt MV (2011): Animal models for depression and the mismatch hypothesis of disease. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 36:330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, de Boer SF, Flugge G, Korte SM, et al. (2011): Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 35:1291–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milic M, Schmitt U, Lutz B, Muller MB (2021): Individual baseline behavioral traits predict the resilience phenotype after chronic social defeat. Neurobiol Stress. 14:100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayash S, Schmitt U, Muller MB (2020): Chronic social defeat-induced social avoidance as a proxy of stress resilience in mice involves conditioned learning. J Psychiatr Res. 120:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selye H (1950): Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. Br Med J. 1:1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McEwen BS (1998): Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 840:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McEwen BS, Stellar E (1993): Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 153:2093–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packard AE, Ghosal S, Herman JP, Woods SC, Ulrich-Lai YM (2014): Chronic variable stress improves glucose tolerance in rats with sucrose-induced prediabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 47:178–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatton-Jones K, Cox AJ, Peart JN, Headrick JP, du Toit EF (2022): Stress-induced body weight loss and improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors do not translate to improved myocardial ischemic tolerance in western diet-fed mice. Physiol Rep. 10:e15170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jene T, Ruiz de Azua I, Hasch A, Klupfel J, Deuster J, Maas M, et al. (2021): Chronic social stress lessens the metabolic effects induced by a high-fat diet. J Endocrinol. 249:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman JP (2013): Neural control of chronic stress adaptation. Front Behav Neurosci. 7:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, et al. (2016): Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol. 6:603–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy MP, Sottas CM, Ge R, McKittrick CR, Tamashiro KL, McEwen BS, et al. (2002): Trends of reproductive hormones in male rats during psychosocial stress: role of glucocorticoid metabolism in behavioral dominance. Biol Reprod. 67:1750–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair BB, Khant Aung Z, Porteous R, Prescott M, Glendining KA, Jenkins DE, et al. (2021): Impact of chronic variable stress on neuroendocrine hypothalamus and pituitary in male and female C57BL/6J mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 33:e12972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marti O, Gavalda A, Jolin T, Armario A (1993): Effect of regularity of exposure to chronic immobilization stress on the circadian pattern of pituitary adrenal hormones, growth hormone, and thyroid stimulating hormone in the adult male rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 18:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pace SA, Christensen C, Schackmuth MK, Wallace T, McKlveen JM, Beischel W, et al. (2020): Infralimbic cortical glutamate output is necessary for the neural and behavioral consequences of chronic stress. Neurobiol Stress. 13:100274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba S, Numakawa T, Ninomiya M, Richards MC, Wakabayashi C, Kunugi H (2012): Chronic restraint stress causes anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, downregulates glucocorticoid receptor expression, and attenuates glutamate release induced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 39:112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willner P (2017): The chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression: History, evaluation and usage. Neurobiol Stress. 6:78–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Kloet ER, Molendijk ML (2016): Coping with the Forced Swim Stressor: Towards Understanding an Adaptive Mechanism. Neural Plast. 2016:6503162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwabe L, Wolf OT (2013): Stress and multiple memory systems: from 'thinking' to 'doing'. Trends Cogn Sci. 17:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dias-Ferreira E, Sousa JC, Melo I, Morgado P, Mesquita AR, Cerqueira JJ, et al. (2009): Chronic stress causes frontostriatal reorganization and affects decision-making. Science. 325:621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herman JP, Adams D, Prewitt C (1995): Regulatory changes in neuroendocrine stress-integrative circuitry produced by a variable stress paradigm. Neuroendocrinology. 61:180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willner P (1997): Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 134:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortiz J, Fitzgerald LW, Lane S, Terwilliger R, Nestler EJ (1996): Biochemical adaptations in the mesolimbic dopamine system in response to repeated stress. Neuropsychopharmacol. 14:443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe Y, Gould E, McEwen BS (1992): Stress induces atrophy of apical dendrites of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons. Brain Res. 588:341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dias C, Feng J, Sun H, Shao NY, Mazei-Robison MS, Damez-Werno D, et al. (2014): beta-catenin mediates stress resilience through Dicer1/microRNA regulation. Nature. 516:51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez JP, Fiori LM, Cruceanu C, Lin R, Labonte B, Cates HM, et al. (2017): MicroRNAs 146a/b-5 and 425-3p and 24-3p are markers of antidepressant response and regulate MAPK/Wnt-system genes. Nat Commun. 8:15497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torres-Berrio A, Lopez JP, Bagot RC, Nouel D, Dal Bo G, Cuesta S, et al. (2017): DCC Confers Susceptibility to Depression-like Behaviors in Humans and Mice and Is Regulated by miR-218. Biol Psychiatry. 81:306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK (2002): Cardiovascular alterations and autonomic imbalance in an experimental model of depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 282:R1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radley JJ, Sawchenko PE (2015): Evidence for involvement of a limbic paraventricular hypothalamic inhibitory network in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptations to repeated stress. J Comp Neurol. 523:2769–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheeta S, Ruigt G, van Proosdij J, Willner P (1997): Changes in sleep architecture following chronic mild stress. Biol Psychiatry. 41:419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iniguez SD, Vialou V, Warren BL, Cao JL, Alcantara LF, Davis LC, et al. (2010): Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-2 within the ventral tegmental area regulates responses to stress. J Neurosci. 30:7652–7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaeuble D, Packard AEB, McKlveen JM, Morano R, Fourman S, Smith BL, et al. (2019): Prefrontal Cortex Regulates Chronic Stress-Induced Cardiovascular Susceptibility. J Am Heart Assoc. 8:e014451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry J, Stephens P (1977): Stress, Health and the Social Environment: Sociobiological Approaches to Medicine. New York: Springer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Buwalda B, van Reenen K (2007): Individual variation in coping with stress: A multidimensional approach of ultimate and proximate mechanisms. Brain Behavior and Evolution. 70:218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman JP (2022): The neuroendocrinology of stress: Glucocorticoid signaling mechanisms. Psychoneuroendocrino. 137:105641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magarinos AM, Deslandes A, McEwen BS (1999): Effects of antidepressants and benzodiazepine treatments on the dendritic structure of CA3 pyramidal neurons after chronic stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 371:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rygula R, Abumaria N, Domenici E, Hiemke C, Fuchs E (2006): Effects of fluoxetine on behavioral deficits evoked by chronic social stress in rats. Behav Brain Res. 174:188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt MV, Czisch M, Sterlemann V, Reinel C, Samann P, Muller MB (2009): Chronic social stress during adolescence in mice alters fat distribution in late life: prevention by antidepressant treatment. Stress. 12:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS (2000): Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 20:9104–9110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serretti A, Calati R, Goracci A, Di Simplicio M, Castrogiovanni P, De Ronchi D (2010): Antidepressants in healthy subjects: what are the psychotropic/psychological effects? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 20:433–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knutson B, Wolkowitz OM, Cole SW, Chan T, Moore EA, Johnson RC, et al. (1998): Selective alteration of personality and social behavior by serotonergic intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 155:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young SN, Moskowitz DS, aan het Rot M (2014): Possible role of more positive social behaviour in the clinical effect of antidepressant drugs. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 39:60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feder A, Haglund M, Wu G, Southwick S, Charney DS (2013): The Neurobiology of Resilience. In: Charney DS, Buxbaum J, Sklar P, Nestler E, editors. Neurobiology of Mental Illness (4 edn): Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horn SR, Charney DS, Feder A (2016): Understanding resilience: New approaches for preventing and treating PTSD. Exp Neurol. 284:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. (2007): Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 131:391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2010): Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 13:1161–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koolhaas JM, Korte SM, De Boer SF, Van Der Vegt BJ, Van Reenen CG, Hopster H, et al. (1999): Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 23:925–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sluyter F, Korte SM, Bohus B, Van Oortmerssen GA (1996): Behavioral stress response of genetically selected aggressive and nonaggressive wild house mice in the shock-probe/defensive burying test. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 54:113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veenema AH, Koolhaas JM, De Kloet ER (2004): Basal and stress-induced differences in HPA axis, 5-HT responsiveness, and hippocampal cell proliferation in two mouse lines. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 1018:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veenema AH, Meijer OC, de Kloet ER, Koolhaas JM, Bohus BG (2003): Differences in basal and stress-induced HPA regulation of wild house mice selected for high and low aggression. Horm Behav. 43:197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnan V (2014): Defeating the fear: new insights into the neurobiology of stress susceptibility. Exp Neurol. 261:412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lehmann ML, Weigel TK, Cooper HA, Elkahloun AG, Kigar SL, Herkenham M (2018): Decoding microglia responses to psychosocial stress reveals blood-brain barrier breakdown that may drive stress susceptibility. Sci Rep. 8:11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee S, Lee C, Woo C, Kang SJ, Shin KS (2019): Chronic social defeat stress increases burst firing of nucleus accumbens-projecting ventral subicular neurons in stress-susceptible mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 515:468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorsch ZS, Loh YE, Purushothaman I, Walker DM, Parise EM, Salery M, et al. (2018): Estrogen receptor alpha drives pro-resilient transcription in mouse models of depression. Nat Commun. 9:1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dudek KA, Dion-Albert L, Lebel M, LeClair K, Labrecque S, Tuck E, et al. (2020): Molecular adaptations of the blood-brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117:3326–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Golden SA, Covington HE 3rd, Berton O, Russo SJ (2011): A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat Protoc. 6:1183–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Russo SJ (2017): Immune and Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of Stress Vulnerability and Resilience. Neuropsychopharmacol. 42:62–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ebner K, Singewald N (2017): Individual differences in stress susceptibility and stress inhibitory mechanisms. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 14:54–64. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morais-Silva G, Costa-Ferreira W, Gomes-de-Souza L, Pavan JC, Crestani CC, Marin MT (2019): Cardiovascular outcomes related to social defeat stress: New insights from resilient and susceptible rats. Neurobiol Stress. 11:100181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seligowski AV, Lebois LAM, Hill SB, Kahhale I, Wolff JD, Jovanovic T, et al. (2019): Autonomic responses to fear conditioning among women with PTSD and dissociation. Depress Anxiety. 36:625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paulus MP, Stein MB (2006): An insular view of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 60:383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fink G (2017): Stress neuroendocrinology: Highlights and Controversies. London: Eslevier. [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Boer SF, Buwalda B, Koolhaas JM (2016): Untangling the neurobiology of coping styles in rodents: Towards neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in disease susceptibility. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seligowski AV, Harnett NG, Merker JB, Ressler KJ (2020): Nervous and Endocrine System Dysfunction in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Overview and Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 5:381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hinrichs R, van Rooij SJ, Michopoulos V, Schultebraucks K, Winters S, Maples-Keller J, et al. (2019): Increased Skin Conductance Response in the Immediate Aftermath of Trauma Predicts PTSD Risk. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klein AS, Dolensek N, Weiand C, Gogolla N (2021): Fear balance is maintained by bodily feedback to the insular cortex in mice. Science. 374:1010–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez J, Bagot RC (2021): Defining Valid Chronic Stress Models for Depression With Female Rodents. Biol Psychiatry. 90:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wohleb ES, Terwilliger R, Duman CH, Duman RS (2018): Stress-Induced Neuronal Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Provokes Microglia-Mediated Neuronal Remodeling and Depressive-like Behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 83:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bulin SE, Hohl KM, Paredes D, Silva JD, Morilak DA (2020): Bidirectional Optogenetically-Induced Plasticity of Evoked Responses in the Rat Medial Prefrontal Cortex Can Impair or Enhance Cognitive Set-Shifting. eNeuro. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi A, Chung JR, Zhang S, Zhang H, Grossman Y, Aleyasin H, et al. (2017): Establishment of a repeated social defeat stress model in female mice. Sci Rep. 7:12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ver Hoeve ES, Kelly G, Luz S, Ghanshani S, Bhatnagar S (2013): Short-term and long-term effects of repeated social defeat during adolescence or adulthood in female rats. Neuroscience. 249:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Westenbroek C, Ter Horst GJ, Roos MH, Kuipers SD, Trentani A, den Boer JA (2003): Gender-specific effects of social housing in rats after chronic mild stress exposure. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 27:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Westenbroek C, Den Boer JA, Ter Horst GJ (2003): Gender-specific effects of social housing on chronic stress-induced limbic Fos expression. Neuroscience. 121:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarkar A, Kabbaj M (2016): Sex Differences in Effects of Ketamine on Behavior, Spine Density, and Synaptic Proteins in Socially Isolated Rats. Biol Psychiatry. 80:448–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carere C, Caramaschi D, Fawcett TW (2010): Covariation between personalities and individual differences in coping with stress: Converging evidence and hypotheses. Current Zoology. 56:728–740. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raulo A, Dantzer B (2018): Associations between glucocorticoids and sociality across a continuum of vertebrate social behavior. Ecol Evol. 8:7697–7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sih A (2011): Effects of early stress on behavioral syndromes: an integrated adaptive perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 35:1452–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hau M, Casagrande S, Ouyang J, Baugh A (2016): Glucocorticoid-mediated phenotypes in vertebrates: Mulitlevel variation and evolution. Advances in the Study of Behavior. 48:41–115. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koolhaas JM (2008): Coping style and immunity in animals: Making sense of individual variation. Brain Behav Immun. 22:662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sgoifo A, de Boer SF, Haller J, Koolhaas JM (1996): Individual differences in plasma catecholamine and corticosterone stress responses of wild-type rats: relationship with aggression. Physiol Behav. 60:1403–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sgoifo A, Carnevali L, Grippo AJ (2014): The socially stressed heart. Insights from studies in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 39:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carnevali L, Trombini M, Porta A, Montano N, de Boer SF, Sgoifo A (2013): Vagal withdrawal and susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias in rats with high trait aggressiveness. PLoS One. 8:e68316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, Tennekes R, Bruggink JE, Koolhaas JM (1999): Individual behavioral characteristics of wild-type rats predict susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Behav Immun. 13:279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huhman KL (2006): Social conflict models: can they inform us about human psychopathology? Horm Behav. 50:640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Boer SF, de Beun R, Slangen JL, van der Gugten J (1990): Dynamics of plasma catecholamine and corticosterone concentrations during reinforced and extinguished operant behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 47:691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dantzer R, Terlouw C, Tazi A, Koolhaas JM, Bohus B, Koob GF, et al. (1988): The propensity for schedule-induced polydipsia is related to differences in conditioned avoidance behaviour and in defense reactions in a defeat test. Physiol Behav. 43:269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moal ML (2016): Individual vulnerabilities relative for potential pathological conditions. Brain Res. 1645:65–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Myers B, McKlveen JM, Morano R, Ulrich-Lai YM, Solomon MB, Wilson SP, et al. (2017): Vesicular Glutamate Transporter 1 Knockdown in Infralimbic Prefrontal Cortex Augments Neuroendocrine Responses to Chronic Stress in Male Rats. Endocrinology. 158:3579–3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guindre-Parker S, McAdam AG, van Kesteren F, Palme R, Boonstra R, Boutin S, et al. (2019): Individual variation in phenotypic plasticity of the stress axis. Biol Lett. 15:20190260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krebs CJ, Boonstra R, Boutin S (2018): Using experimentation to understand the 10-year snowshoe hare cycle in the boreal forest of North America. J Anim Ecol. 87:87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taborsky B, English S, Fawcett TW, Kuijper B, Leimar O, McNamara JM, et al. (2021): Towards an Evolutionary Theory of Stress Responses. Trends Ecol Evol. 36:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ayash S, Schmitt U, Lyons DM, Muller MB (2020): Stress inoculation in mice induces global resilience. Transl Psychiatry. 10:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meduri JD, Farnbauch LA, Jasnow AM (2013): Paradoxical enhancement of fear expression and extinction deficits in mice resilient to social defeat. Behav Brain Res. 256:580–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dulka BN, Lynch JF 3rd, Latsko MS, Mulvany JL, Jasnow AM (2015): Phenotypic responses to social defeat are associated with differences in cued and contextual fear discrimination. Behav Processes. 118:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sgoifo A, Costoli T, Meerlo P, Buwalda B, Pico'-Alfonso MA, De Boer S, et al. (2005): Individual differences in cardiovascular response to social challenge. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 29:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Melhorn SJ, Askren MK, Chung WK, Kratz M, Bosch TA, Tyagi V, et al. (2018): FTO genotype impacts food intake and corticolimbic activation. Am J Clin Nutr. 107:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Langgartner D, Marks J, Nguyen TC, Reber SO (2020): Changes in adrenal functioning induced by chronic psychosocial stress in male mice: A time course study. Psychoneuroendocrino. 122:104880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nyuyki KD, Beiderbeck DI, Lukas M, Neumann ID, Reber SO (2012): Chronic subordinate colony housing (CSC) as a model of chronic psychosocial stress in male rats. PLoS One. 7:e52371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maier SF, Seligman ME (2016): Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychol Rev. 123:349–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF (2005): Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nat Neurosci. 8:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Santarelli S, Zimmermann C, Kalideris G, Lesuis SL, Arloth J, Uribe A, et al. (2017): An adverse early life environment can enhance stress resilience in adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 78:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Santarelli S, Lesuis SL, Wang XD, Wagner KV, Hartmann J, Labermaier C, et al. (2014): Evidence supporting the match/mismatch hypothesis of psychiatric disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 24:907–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cotella EM, Morano RL, Wulsin AC, Martelle SM, Lemen P, Fitzgerald M, et al. (2020): Lasting Impact of Chronic Adolescent Stress and Glucocorticoid Receptor Selective Modulation in Male and Female Rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 112:104490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chaby LE, Sadik N, Burson NA, Lloyd S, O'Donnel K, Winters J, et al. (2020): Repeated stress exposure in mid-adolescence attenuates behavioral, noradrenergic, and epigenetic effects of trauma-like stress in early adult male rats. Sci Rep. 10:17935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parker KJ, Buckmaster CL, Hyde SA, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM (2019): Nonlinear relationship between early life stress exposure and subsequent resilience in monkeys. Sci Rep. 9:16232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Walker CD, Bath KG, Joels M, Korosi A, Larauche M, Lucassen PJ, et al. (2017): Chronic early life stress induced by limited bedding and nesting (LBN) material in rodents: critical considerations of methodology, outcomes and translational potential. Stress. 20:421–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Maccari S, Krugers HJ, Morley-Fletcher S, Szyf M, Brunton PJ (2014): The consequences of early-life adversity: neurobiological, behavioural and epigenetic adaptations. J Neuroendocrinol. 26:707–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kalisch R, Muller MB, Tuscher O (2015): A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. Behav Brain Sci. 38:e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brockhurst J, Cheleuitte-Nieves C, Buckmaster CL, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM (2015): Stress inoculation modeled in mice. Transl Psychiatry. 5:e537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee AG, Buckmaster CL, Yi E, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM (2014): Coping and glucocorticoid receptor regulation by stress inoculation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 49:272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Scott KA, de Kloet AD, Smeltzer MD, Krause EG, Flak JN, Melhorn SJ, et al. (2017): Susceptibility or resilience? Prenatal stress predisposes male rats to social subordination, but facilitates adaptation to subordinate status. Physiol Behav. 178:117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stetz MC, Thomas ML, Russo MB, Stetz TA, Wildzunas RM, McDonald JJ, et al. (2007): Stress, mental health, and cognition: a brief review of relationships and countermeasures. Aviat Space Environ Med. 78:B252–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Meichenbaum D, Novaco R (1985): Stress inoculation: a preventative approach. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 7:419–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Saunders T, Driskell JE, Johnston JH, Salas E (1996): The effect of stress inoculation training on anxiety and performance. J Occup Health Psychol. 1:170–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A (2008): Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behav Res Ther. 46:5–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McNally RJ (2007): Mechanisms of exposure therapy: how neuroscience can improve psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 27:750–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Habes I, Krall SC, Johnston SJ, Yuen KS, Healy D, Goebel R, et al. (2013): Pattern classification of valence in depression. Neuroimage Clin. 2:675–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rosenblau G, Sterzer P, Stoy M, Park S, Friedel E, Heinz A, et al. (2012): Functional neuroanatomy of emotion processing in major depressive disorder is altered after successful antidepressant therapy. J Psychopharmacol. 26:1424–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Greening SG, Osuch EA, Williamson PC, Mitchell DG (2013): Emotion-related brain activity to conflicting socio-emotional cues in unmedicated depression. J Affect Disord. 150:1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]