Abstract

Objective

AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) has been proven to be closely related to tumors. However, the role and molecular mechanism of ALKBH5 in neuroblastomas have rarely been reported.

Methods

The potential functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ALKBH5 were identified by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dbSNP screening and SNPinfo software. TaqMan probes were used for genotyping. A multiple logistic regression model was used to evaluate the effects of different SNP loci on the risk of neuroblastoma. The expression of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma was evaluated by Western blotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), plate colony formation and 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assays were used to evaluate cell proliferation. Wound healing and Transwell assays were used to compare cell migration and invasion. Thermodynamic modelling was performed to predict the ability of miRNAs to bind to ALKBH5 with the rs8400 G/A polymorphism. RNA sequencing, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) sequencing, m6A methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) and a luciferase assay were used to identify the targeting effect of ALKBH5 on SPP1.

Results

ALKBH5 was highly expressed in neuroblastoma. Knocking down ALKBH5 inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells. miR-186-3p negatively regulates the expression of ALKBH5, and this ability is affected by the rs8400 polymorphism. When the G nucleotide was mutated to A, the ability of miR-186-3p to bind to the 3’-UTR of ALKBH5 decreased, resulting in upregulation of ALKBH5. SPP1 is the downstream target gene of the ALKBH5 oncogene. Knocking down SPP1 partially restored the inhibitory effect of ALKBH5 downregulation on neuroblastoma. Downregulation of ALKBH5 can improve the therapeutic efficacy of carboplatin and etoposide in neuroblastoma.

Conclusions

We first found that the rs8400 G>A polymorphism in the m6A demethylase-encoding gene ALKBH5 increases neuroblastoma susceptibility and determines the related mechanisms. The aberrant regulation of ALKBH5 by miR-186-3p caused by this genetic variation in ALKBH5 promotes the occurrence and development of neuroblastoma through the ALKBH5-SPP1 axis.

Keywords: Neuroblastoma, risk, ALKBH5, polymorphism, progression

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is a solid tumor of the sympathetic nervous system (1). It accounts for 7% of all childhood cancers and 15% of childhood cancer-related deaths (2). Neuroblastoma is a heterogeneous malignancy with prognoses ranging from spontaneous regression with a good outcome to metastatic disease with a poor outcome (3,4). Despite advances in the treatment of paediatric cancers, the survival rates of patients with high-risk neuroblastomas are still less than 50% (5,6).

With the development of whole-genome sequencing techniques, increasing attention has been paid to the important roles of genetic variations in neuroblastoma. Genetic markers help us to understand the genetic aetiology and guide the treatment of neuroblastoma (7-9). Neuroblastomas are frequently associated with mutations in the PHOX2B (10) and ALK (11,12) genes, amplification of the MYCN gene, and loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 1p. The oncogenic effects of mutations in PTPN11, ATRX, TERT, LMO1 and NRAS previously found in neuroblastoma have also been investigated (13-19). Multiple neuroblastoma risk-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) (20-24). Maris et al. first demonstrated that the rs9295536, rs4712653 and rs6939340 polymorphisms are associated with neuroblastoma susceptibility (25). Interestingly, Oldridge et al. demonstrated that the SNP rs2168101 polymorphism affects GATA transcription factor binding sites within enhancer elements, resulting in altered LMO1 expression that affects neuroblastoma progression (24). However, the set of currently identified genetic mutations or variants is not sufficient to predict neuroblastoma risk.

With the development of methylated transcriptome analysis approaches, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) has been proven to be the most common posttranscriptional modification of messenger RNA (mRNA) in eukaryotes (26,27). The key regulators of m6A modification include mainly the following three protein complexes: RNA methyltransferases (METTL3/14, WTAP, RBM15/15B and VIRMA, termed “writers”), demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5, termed “erasers”), and m6A-binding proteins (YTHDC1/2, YTHDF1/2/3, IGF2BP1/2/3, HNRNP and eIF3, termed “readers”) (28). Human AlkB homolog H5 (ALKBH5), a member of the ALKB family, is a critical m6A demethylase that catalyses the direct removal of m6A (29). Aberrant ALKBH5 expression affects RNA metabolism, RNA nuclear export, and gene expression (30). ALKBH5 is critically implicated in the occurrence and progression of human malignancies. ALKBH5 plays oncogenic or tumor-suppressive roles in different types of cancer (31-35). One study showed that ALKBH5 reduced PER1 degradation in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner via m6A demethylation and that posttranscriptional upregulation of PER1 resulted in inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth by activating ATM-CHK2-P53/CDC25C signalling (36). Recent studies show that ALKBH5 can promote tumor progression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting interferon-alpha production and RIG-I expression (35). Tan et al. established and validated a prognostic glucose metabolism model based on the overlap between differentially expressed genes related to ALKBH5 and glucose metabolism-related genes in an analysis based on the GSE62564 dataset, and the results suggested that ALKBH5 was related to the process of glucose metabolism (37). However, the roles of the ALKBH5 gene and its SNPs in neuroblastoma remain unclear.

Here we report the identification of the rs8400 polymorphism in the ALKBH5 gene as a new locus for susceptibility to neuroblastoma in the Chinese Han population. Biochemical analysis showed that the rs8400 polymorphism could affect the expression of the host gene ALKBH5 to promote neuroblastoma progression. Mechanistically, the rs8400 G>A SNP (located in a microRNA binding site) leads to the failure of miR-186-3p to negatively regulate ALKBH5 expression, leading to upregulation of ALKBH5. In addition, we functionally validated the oncogenic effects of the rs8400 SNP and ALKBH5 expression in neuroblastoma. Subsequently, we further identified SPP1 as the downstream target gene of ALKBH5. Therefore, our findings indicate that the miR-186-3p-ALKBH5-SPP1 axis is closely related to the occurrence and development of neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

Participants for this study were pooled from 9 hospitals across China. We defined cases as patients with a histologically verified first-time diagnosis of neuroblastoma. Controls who had no diagnosis of any cancers were randomly selected from the same hospital and individually matched to the cases in age and sex. Patients’ clinical characteristics are described in Supplementary Table S1. Participants provided written informed consent at screening. Detailed descriptions of the study participants have been published in our previous work (38,39).

Table S1. Frequency distribution of selected characteristics in neuroblastoma cases and cancer-free controls.

| Variables | Combined subjects (9 centers) [n (%)] | ||||

| Cases (N=968) | Controls (N=1,814) | Pa | |||

| INSS, International Neuroblastoma Staging System; NA, not available; a, two-sided χ2 test for distributions between neuroblastoma cases and cancer-free controls. | |||||

| Age (range) (month) | 0−176 | 0−156 | 0.536 | ||

|

32.85±28.22 | 31.67±26.40 | |||

| ≤18 | 380 (39.26) | 734 (40.46) | |||

| >18 | 588 (60.74) | 1,080 (59.54) | |||

| Gender | 0.231 | ||||

| Female | 437 (45.14) | 776 (42.78) | |||

| Male | 531 (54.86) | 1,038 (57.22) | |||

| INSS stages | |||||

| I | 344 (35.54) | − | |||

| II | 164 (16.94) | − | |||

| III | 169 (17.46) | − | |||

| IV | 253 (26.14) | − | |||

| 4s | 20 (2.07) | − | |||

| NA | 18 (1.86) | − | |||

| Sites of origin | |||||

| Adrenal gland | 260 (26.86) | − | |||

| Retroperitoneal region | 344 (35.54) | − | |||

| Mediastinum | 234 (24.17) | − | |||

| Other region | 118 (12.19) | − | |||

| NA | 12 (1.24) | − | |||

Neuroblastoma tissue samples

Frozen neuroblastoma tissue samples were collected from the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, and the neuroblastoma samples were categorized into two groups: the early-stage (stages I and II, n=10) and advanced-stage (stages III and IV, n=10) groups, based on the clinicopathological information. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before enrolment.

Polymorphism selection and genotyping

Potential functional SNPs in the ALKBH5 gene were retrieved from the dbSNP database and with SNPinfo software (40). DNA was extracted from blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, USA) and further genotyped using the standard TaqMan Genotyping Array (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). On each 384-well plate, blind duplicate samples (10% samples) were included for quality control. A concordance rate of 100% was achieved. The genotyping completion rate for all SNPs was >95%.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Neuroblastoma tissue was fixed with 10% formaldehyde by a professional pathologist, and paraffin-embedded tissue sections were generated. After 1 h of baking, the sections were sequentially dewaxed, subjected to antigen retrieval, blocked with 5% goat serum for 30 min, and then incubated with an anti-ALKBH5 rabbit primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The next day, an anti-rabbit secondary antibody was applied for 30 min after rewarming. After that, 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogenic reagent was used for color development to visualize staining. After confirming staining, the sections were incubated with haematoxylin for 5 s to stain nuclei and differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid for 10 s; finally, cover slips were mounted for observation. The whole process of immunohistochemical staining was carried out by trained professional laboratory technicians who are not familiar with experiments. In immunohistochemical staining, the ALKBH5 signals of different stages and genotypes were compared and analyzed according to the number of positive signals and the intensity of positive signals (color depth) (41).

Cell culture

The neuroblastoma cell lines SK-N-SH, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-BE(2)-C and SK-N-AS were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in EMEM, RPMI-1640 medium, and F12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. All the cells were authenticated by short-tandem repeat genetic profiling and found to be free of mycoplasma contamination by testing.

Transfection

Production of the ALKBH5 knockdown and overexpression lentiviruses was performed by OBiO (OBiO Technology Corp., China). Neuroblastoma cells were plated in 6-wells dishes at 50% confluence and infected with ALKBH5 knockdown lentivirus (termed shALKBH5-1) or scramble control lentivirus (termed shNC). The shALKBH5 sequence was 5’-GAAGCTTCAATGGTCTCCTTA-3’. The shNC sequence was 5’-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3’. Pools of stable transductants were generated by selection using puromycin (4 μg/mL) for 2 weeks. The miR-186 mimics and inhibitors used for transfection were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Transfection was performed using Opti-MEM and an IMAX kit (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell proliferation

The cell proliferation rate was determined with a cell counting kit (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 3×103 cells/well were seeded in 96-well culture plates and incubated for the indicated time. Then, CCK-8 solution (100 μL) was added, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured. A colony formation assay (plate colony formation assay) was performed to evaluate the long-term proliferation of neuroblastoma cells with knockdown of ALKBH5 expression.

Cell cycle assay

A total of 1×106 cells were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with 75% cold ethanol for 24 h at −20 °C. After being washed with PBS twice and stained with propidium iodide from a Cycletest Plus DNA Reagent Kit (BD Biosciences, USA) at room temperature for 30 min, cells were examined by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, USA), and the cell cycle distribution was analyzed by ModFit LT software (Version 4.1.7; Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA).

Wound healing assay

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 5×105 cells per well. Then, a wound was made in the cell monolayer by scratching with a 200 μL pipette tip. The detached cells were then removed by washing with PBS. Cell motility in each group was assessed by visualizing the speed of wound closure at intervals.

Cell migration assay

A Transwell (Costar, New York, NY, USA) assay was used to evaluate the migration capacity. Cells (1×105 cells/well) in a serum-free medium were placed in the upper chamber, and medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After incubation for the indicated time, cells on the upper surface of the membrane were removed. The migrated cells were fixed with formaldehyde and stained using 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma). The migrated cells were counted under a microscope.

Western blotting analysis

Protein extracts were lysed on ice with RIPA buffer containing both protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Equal amount of protein was then loaded on a gel and finally transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked using 5% BSA and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted 1:1,000. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (1:5,000) and anti-rabbit (1:2,000) secondary antibodies were used. The membrane was incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and band densities were quantified by ImageJ analysis software (Version 1.43; National Institutes of Health, USA).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using an RNA extraction kit (#RN001, ESscience, Shanghai, China) and converted to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (#RR036A-1, TAKARA, Japan). Quantitative mRNA expression levels were determined using real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (ABI Q6 System, Applied Biosystems, USA). GAPDH was used as the internal reference gene. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Specific primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Table S2. Primers used in this study.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5’−3’) | |

| RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; MeRIP-qPCR, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation quantitative polymerase chain reaction. | ||

| RT-qPCR | F | R |

| ALKBH5 | TGAGCACAGTCACGCTTCC | TCCGTGTCCTTCTTTAGCGACTC |

| SPP1 | TCTGAGGAAAAGCAGCACTAA | TGTGTGCCTTTTTGTCCAAGC |

| COL15A1 | CCGCCTTTGTTCCCTGC | CCCGTTGTTCCTCCTTGGTG |

| ADADTS12 | AGCTCTACTGCCGACCCATA | AGTCACAGCCAACCATCTTACA |

| RP11-440G9.1 | CAGCTCTCACTCCCTTCTCA | GTGCTAAGACCTTGTGCTGG |

| SYT14 | AACAGACCACCCAATGGACT | CCCTCTGCGGATGGATGTCT |

| GAPDH | AGTGCCAGCCTCGTCTCATA | GGTAACCAGGCGTCCGATA |

| MeRIP-qPCR | ||

| SPP1 | TGTTGTAACCTATGAAGATGTCAGC | GAGGCAAAAGCAAATCACTGC |

RNA sequencing

mRNA sequencing was performed on ALKBH5-knockout (KO-ALKBH5) and control BxPC cells (Vector) using the HiSeq 2000 platform to generate single-end reads with a read length of 50 bp (PE50) (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing data for each gene were then converted to FPKM (fragments per kilobase mRNA sequence per million mapped reads) values by TopHat-Cufflinks (v2.2.1). Gene Ontology (GO) and signalling pathway enrichment analyses were subsequently performed using DAVID (www.david.niaid.nih.gov) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), respectively.

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) and m6A sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from stable KO-ALKBH5 SK-N-AS cells and control cells with TRIzol (Thermo Fisher). According to the instructions of the MeRIP kit (C11051-1, Magneto, USA), RNA was fragmented, immunoprecipitated with an anti-m6A antibody, and finally eluted and purified. The concentration of m6A-modified mRNA was then analyzed by RT-qPCR or high-throughput RNA sequencing using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform, and each group was analyzed in duplicate.

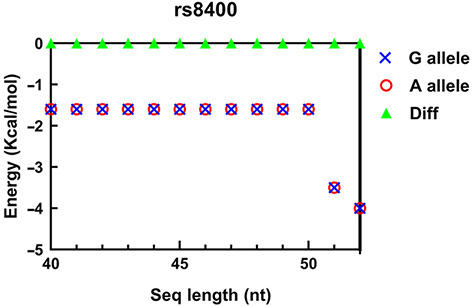

Thermodynamic modelling of miRNA-target interactions

We compared the ability of miRNA-186-3p to bind to the rs8400 G allele and A allele using a secondary structure-based nonparametric thermodynamic modelling study. ETarget represents the dissociation energy of the targeted region of the mRNA with no interaction with the microRNA. EIntermediate represents the energy required to make the target region available for microRNA binding, and EComplex represents the free energy of the final microRNA-target complex. To avoid sequence length dependence, we determined the final target sequence length by increasing number of nucleotides surrounding the region consisting of the target seed region and the SNP site (Supplementary Figure S1). We calculated the minimum free energy (MFE) of the target sequence (G or A) and the free energy of the partition function folding by RNAfold, and we took the MFE as the ETarget after considering the consistency of the centroid structure free energy and MFE. When computing EComplex, we input the miRNA and target sequences into RNAcofold. Considering the different structures (including suboptimal structures) that the miRNAs and target sequences actually form, we assigned the ensemble energies of the allocation function folding rather than just the MFE as EComplex. We calculated EIntermediate by constraining all possible binding sites of the miRNA and the target sequence to an unpaired state.

Figure S1.

Secondary structure energies of ALKBH5 3’UTR with different sequence lengths. To avoid sequence length-dependent effects, a nucleotide sequence around miR-186-3p seed binding site and SNP site was extended to a length of 40−52 nt toward the 5’ end. The final target sequence was determined to be 52 nt. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; nt, nucleotide.

Luciferase reporter assay

The ALKBH5 3’-UTR (rs8400) and SPP1 overexpression reporter plasmids (purchased from Promega) were constructed by using the pGL3 and PNL3.1 luciferase reporter plasmids, respectively. The constructed wild-type and mutant plasmids were transfected into both SK-N-AS and SK-N-BE(2)-C cells. After 48 h, the cells were treated according to the instructions of the dual luciferase reporter detection kit (E1910, N1610), and the ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase activity was determined. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data are expressed as  .

.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between the cases and controls using Student’s t-test (for continuous variables) and the Chi-square test (for categorical variables). We first applied a goodness-of-fit Chi-square test to assess whether SNPs in the controls were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). An odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated for each SNP for neuroblastoma using logistic regression models. An estimation of haplotype frequency and an analysis of the effect of haplotype on neuroblastoma risk were performed (42,43). We also applied false-positive report probability (FPRP) analysis to evaluate notable associations by a method described elsewhere (44,45). Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis using the online Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) portal (http://www.gtexportal.org/home/) was adopted to determine the correlations between the SNPs and expression levels of nearby genes (46). P<0.05 indicates statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA)

Results

ALKBH5 rs8400 is a new neuroblastoma susceptibility locus in Chinese Han population

We successfully genotyped the two ALKBH5 gene SNPs (rs1378602 and rs8400) in 967 cases and 1,813 controls (Table 1). First, we tested whether the two SNPs were in HWE in the control group by Chi-square test, and results showed that the two SNPs were not statistically significant in HWE (HWE P>0.05). We then performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to explore the relationships between the genotypes of these two ALKBH5 SNPs (rs1378602 and rs8400) and susceptibility to neuroblastoma. We then performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to explore the relationships between rs1378602 and rs8400 genotypes and susceptibility to neuroblastoma. The results showed that the relationship between rs1378602 genotype and neuroblastoma risk was not statistically significant. Notably, the rs8400 mutant A allele was significantly associated with increased susceptibility to neuroblastoma (AA vs. GG: adjusted OR=1.28, 95% CI=1.02−1.61, P=0.030; GG vs. GA vs. AA: adjusted OR=1.12, 95% CI=1.004−1.26, P=0.042; AA vs. GG/GA: adjusted OR=1.25, 95% CI=1.03−1.52, P=0.028). We further observed that participants with 1 risk genotype (adjusted OR=1.23, 95% CI=1.02−1.48, P=0.031) or 1−2 risk genotypes (adjusted OR=1.22, 95% CI=1.03−1.44, P=0.022) exhibited an increased risk of neuroblastoma in comparison to that of participants with 0 risk genotypes.

Table 1. Logistic regression analysis of associations between ALKBH5 gene polymorphisms and neuroblastoma susceptibility.

| Genotype | Cases (N=967) | Controls (N=1,813) | Pa | Crude OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | Pb |

| HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; a, χ2 test for genotype distributions between neuroblastoma cases and cancer-free controls; b, Adjusted for age and sex. Additive model was defined as GG vs. GA vs. AA (rs1378602), GG vs. GA vs. AA (rs8400). Dominant model was defined as AA/GA vs. GG (rs1378602), AA/GA vs. GG (rs8400). Recessive model was defined as AA vs. GG/GA (rs1378602), AA vs. GG/GA (rs8400). | |||||||

| rs1378602 (HWE=0.983) | |||||||

| GG | 785 (81.18) | 1,499 (82.68) | − | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| GA | 173 (17.89) | 299 (16.49) | − | 1.11 (0.90−1.36) | 0.343 | 1.11 (0.90−1.36) | 0.336 |

| AA | 9 (0.93) | 15 (0.83) | − | 1.15 (0.50−2.63) | 0.748 | 1.14 (0.50−2.62) | 0.754 |

| Additive | 0.327 | 1.10 (0.91−1.33) | 0.328 | 1.10 (0.91−1.33) | 0.323 | ||

| Dominant | 182 (18.82) | 314 (17.32) | 0.325 | 1.11 (0.90−1.36) | 0.325 | 1.11 (0.91−1.36) | 0.319 |

| Recessive | 958 (99.07) | 1,798 (99.17) | 0.779 | 1.13 (0.49−2.58) | 0.779 | 1.12 (0.49−2.58) | 0.786 |

| rs8400 (HWE=0.261) | |||||||

| GG | 290 (29.99) | 582 (32.10) | − | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| GA | 473 (48.91) | 911 (50.25) | − | 1.04 (0.87−1.25) | 0.653 | 1.05 (0.88−1.25) | 0.613 |

| AA | 204 (21.10) | 320 (17.65) | − | 1.28 (1.02−1.60) | 0.032 | 1.28 (1.02−1.61) | 0.030 |

| Additive | 0.045 | 1.12 (1.00−1.25) | 0.046 | 1.12 (1.00−1.26) | 0.042 | ||

| Dominant | 677 (70.01) | 1,231 (67.90) | 0.253 | 1.10 (0.93−1.31) | 0.253 | 1.11 (0.94−1.31) | 0.232 |

| Recessive | 763 (78.90) | 1,493 (82.35) | 0.027 | 1.25 (1.03−1.52) | 0.027 | 1.25 (1.03−1.52) | 0.028 |

| Combined risk genotypes | |||||||

| 0 | 655 (67.74) | 1,304 (71.92) | − | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 238 (24.61) | 384 (21.18) | − | 1.23 (1.02−1.49) | 0.028 | 1.23 (1.02−1.48) | 0.031 |

| 2 | 74 (7.65) | 125 (6.89) | 0.043 | 1.18 (0.87−1.60) | 0.287 | 1.19 (0.88−1.61) | 0.271 |

| 0 | 655 (67.74) | 1,304 (71.92) | − | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1−2 | 312 (32.26) | 509 (28.08) | 0.021 | 1.22 (1.03−1.45) | 0.021 | 1.22 (1.03−1.44) | 0.022 |

Stratification analysis of identified SNPs

To reduce the influence of other factors, we further explored the associations between ALKBH5 gene polymorphisms and neuroblastoma susceptibility in certain groups stratified by age, sex, sites of origin and clinical stages (Table 2). Compared with the rs8400 GG/GA genotype, the rs8400 AA genotype increased susceptibility to neuroblastoma, and this association remained statistically significant in the subgroup with mediastinal tumor origin (adjusted OR=1.43, 95% CI=1.03−1.98, P=0.034) and the subgroup with clinical stage I+II+4s (adjusted OR=1.29, 95% CI=1.01−1.64, P=0.041). The combined analysis showed that participants with 1−2 risk genotypes in the following subgroups had a significantly increased neuroblastoma risk: age >18 months (adjusted OR=1.27, 95% CI=1.02−1.58, P=0.033), males (adjusted OR=1.26, 95% CI=1.00−1.58, P=0.049), retroperitoneal tumor origin (adjusted OR=1.29, 95% CI=1.004−1.65, P=0.046), and clinical stage I+II+4s (adjusted OR=1.29, 95% CI=1.04−1.59, P=0.018).

Table 2. Stratification analysis of ALKBH5 gene polymorphisms with neuroblastoma susceptibility.

| Variables | rs1378602 (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Pa | rs8400 (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Pa | Risk genotypes (cases/controls) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | Pa | |||

| GG | GA/AA | GG/GA | AA | 0 | 1−2 | |||||||

| OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; a, Adjusted for age and gender. | ||||||||||||

| Age (month) | ||||||||||||

| ≤18 | 308/594 | 72/141 | 0.99 (0.72−1.36) | 0.946 | 299/607 | 81/128 | 1.29 (0.94−1.76) | 0.114 | 258/519 | 122/216 | 1.14 (0.87−1.49) | 0.334 |

| >18 | 477/905 | 110/173 | 1.19 (0.92−1.56) | 0.189 | 464/886 | 123/192 | 1.22 (0.95−1.57) | 0.125 | 397/785 | 190/293 | 1.27 (1.02−1.58) | 0.033 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 353/628 | 84/146 | 1.04 (0.77−1.40) | 0.797 | 346/633 | 91/141 | 1.17 (0.87−1.58) | 0.286 | 292/543 | 145/231 | 1.17 (0.91−1.50) | 0.227 |

| Male | 432/871 | 98/168 | 1.18 (0.89−1.55) | 0.251 | 417/860 | 113/179 | 1.30 (1.00−1.69) | 0.050 | 363/761 | 167/278 | 1.26 (1.00−1.58) | 0.049 |

| Sites of origin | ||||||||||||

| Adrenal gland | 212/1,499 | 48/314 | 1.10 (0.79−1.54) | 0.573 | 206/1,493 | 54/320 | 1.23 (0.89−1.69) | 0.217 | 180/1,304 | 80/509 | 1.15 (0.87−1.53) | 0.333 |

| Retroperitoneal | 279/1,499 | 64/314 | 1.12 (0.83−1.50) | 0.477 | 273/1,493 | 70/320 | 1.20 (0.90−1.60) | 0.225 | 229/1,304 | 114/509 | 1.29 (1.00−1.65) | 0.046 |

| Mediastinum | 193/1,499 | 41/314 | 0.99 (0.69−1.42) | 0.959 | 179/1,493 | 55/320 | 1.43 (1.03−1.98) | 0.034 | 160/1,304 | 74/509 | 1.17 (0.87−1.57) | 0.311 |

| Others | 90/1,499 | 28/314 | 1.45 (0.93−2.25) | 0.101 | 96/1,493 | 22/320 | 1.07 (0.66−1.72) | 0.791 | 78/1,304 | 40/509 | 1.30 (0.87−1.93) | 0.197 |

| Clinical stages | ||||||||||||

| I+II+4s | 400/1,499 | 98/314 | 1.12 (0.87−1.44) | 0.377 | 398/1,493 | 110/320 | 1.29 (1.01−1.64) | 0.041 | 337/1,304 | 171/509 | 1.29 (1.04−1.59) | 0.018 |

| III+IV | 344/1,499 | 78/314 | 1.12 (0.85−1.48) | 0.419 | 333/1,493 | 89/320 | 1.25 (0.96−1.63) | 0.097 | 290/1,304 | 132/509 | 1.18 (0.94−1.49) | 0.155 |

Characterization of ALKBH5 expression in neuroblastoma

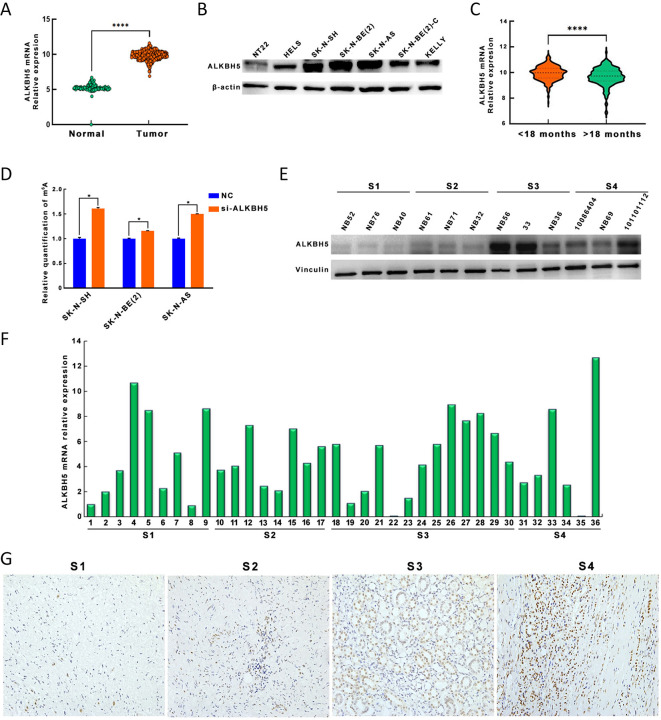

To explore the expression of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma, we first analyzed the publicly accessible data in a GEO dataset (GSE49710) and GTEx. The results showed that ALKBH5 was highly expressed in neuroblastoma tissues (P<0.0001) (Figure 1A). We then measured and compared the expression of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma cell lines [(SK-N-SH, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2)-C, and KELLY] and non-neuroblastoma cell lines (NT22 and HELS) by Western blotting. The results showed that the expression of ALKBH5 protein in neuroblastoma cells was significantly higher than that in non-neuroblastoma cells (Figure 1B). In addition, neuroblastoma occurred more frequently at 18 months of age, and clinical correlation analysis showed that ALKBH5 expression was increased in individuals younger than 18 months (P<0.0001) (Figure 1C). Additionally, m6A levels were elevated in ALKBH5 knockdown (si-ALKBH5) neuroblastoma cells compared with control cells (P<0.05) (Figure 1D). The IHC results showed that ALKBH5 expression was higher in tissues from patients with advanced neuroblastoma (stage 3 and stage 4) than in tissues from patients with early neuroblastoma (stage 1 and stage 2) (Figure 1G). These results suggest that ALKBH5 is significantly upregulated in neuroblastoma and that ALKBH5 upregulation may be related to the poor progression of neuroblastoma. The tissue samples of neuroblastoma patients were further analyzed by RT-qPCR and Western blotting (Figure 1E,F), and the results showed that the mRNA and protein expression of ALKBH5 in late neuroblastoma (stage III and IV) tissues was significantly upregulated compared with that in early neuroblastoma (stage I and II) tissues.

Figure 1.

Downregulation of m6A demethylase gene ALKBH5 represents a characterization of neuroblastoma. (A) ALKBH5 is highly expressed in neuroblastoma tissues compared to normal tissues; (B) Five neuroblastoma cell lines [(SK-N-SH, SK-N-BE(2), SK-N-AS, SK-N-BE(2)-C and KELLY] ALKBH5 protein expression was higher compared to non-neuroblastoma cell lines (NT22 and HELS); (C) ALKBH5 expression increases at less than 18 months of age; (D) m6A expression levels are elevated in ALKBH5 knockdown neuroblastoma (si-ALKBH5) cells compared to controls; (E,F) mRNA and protein expression of ALKBH5 was significantly increased in late neuroblastoma (stages III and IV) tissues compared with early neuroblastoma (stages I and II) tissues; (G) Immunohistochemistry results show that ALKBH5 expression is higher in tissues of patients with advanced neuroblastoma (Magnification 10×). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Effect of ALKBH5 on neuroblastoma cell transcriptome

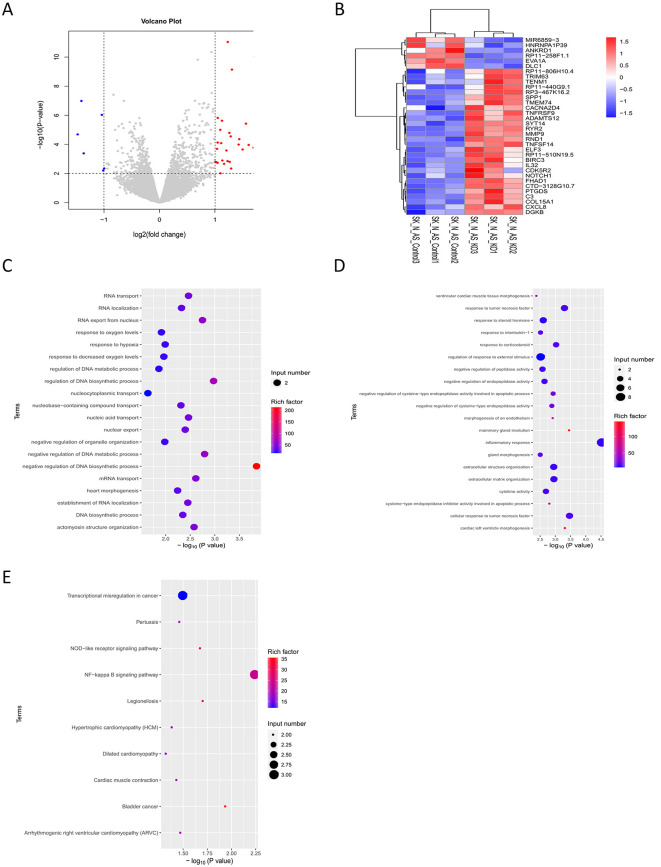

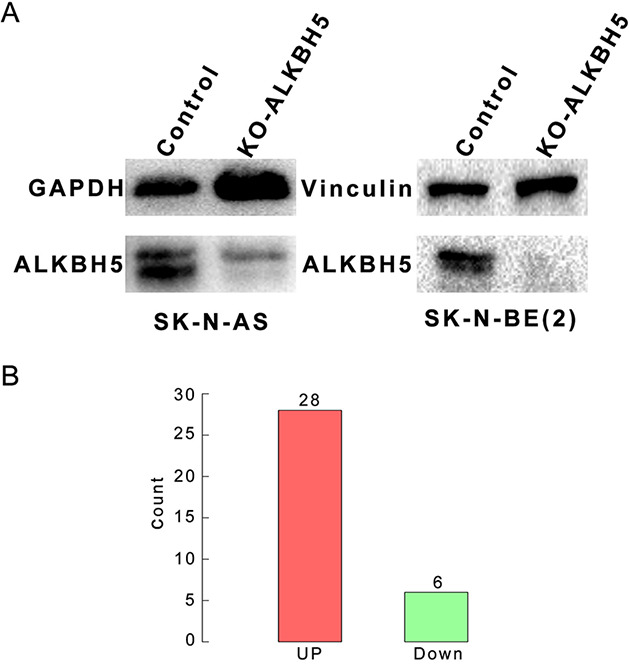

To demonstrate the oncogenic effect of ALKBH5 expression on neuroblastoma, we first investigated the effect of ALKBH5 on the transcriptome of neuroblastoma cells. We used CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to generate neuroblastoma cell lines with stable ALKBH5 knockout (Supplementary Figure S2A). The control cell line was left untreated, and the cells were collected for RNA-seq analysis. Volcano plots generated from the RNA-seq data showed that neuroblastoma cells with knockout of ALKBH5 expression exhibited 34 differentially expressed genes (28 upregulated genes and 6 downregulated genes) (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure S2B). Cluster analysis of the differentially expressed genes revealed that SPP1, MIR6859-3, ANKRD1, and ADAMTS12 were up-regulated in neuroblastoma cell lines with knockout of ALKBH5 compared to the corresponding control cells (Figure 2B). GO enrichment analysis showed that knockout of ALKBH5 resulted in significant downregulation of genes related to RNA trafficking, RNA localization, ribonucleic acid export, and DNA biosynthesis processes, and upregulation of genes related to the cell response to tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1 (Figure 2C,D). KEGG enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes indicated that the upregulated genes were involved in pathways such as transcriptional dysregulation in cancer, NOD-like receptor signalling pathway, and NF-kappa B signalling pathway (Figure 2E). In conclusion, ALKBH5 showed neuroblastoma-promoting activity based on transcriptome regulation.

Figure S2.

Stable knockout cell line construction and number of differentially expressed genes prior to transcriptome analysis. (A) We constructed neuroblastoma cell lines with stable ALKBH5 knockdown using CRISPR-Cas9 technology prior to transcriptome analysis; (B) Neuroblastoma cells with knockout of ALKBH5 expression showed 34 differentially expressed genes (28 up-regulated genes and 6 down-regulated genes).

Figure 2.

Effects of ALKBH5 on transcriptome of neuroblastoma cells. (A) Volcano plots showing up-regulated genes (red) and down-regulated genes (blue) displayed by ALKBH5 knockout neuroblastoma cells; (B) Cluster analysis shows that SPP1, MIR6859-3, ANKRD1 and ADAMTS12 genes are up-regulated in neuroblastoma cell lines with down-regulated ALKBH5 expression; (C,D) GO enrichment analysis showed that genes related to RNA trafficking, localization, ribonucleic acid export, and DNA biosynthesis processes were down-regulated in ALKBH5 knockdown neuroblastoma cells (C), and genes related to the cellular response to tumor necrosis factor are up-regulated (D); (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of differential genes revealed that up-regulated genes are involved in pathways including transcriptional dysregulation in cancer, NOD-like receptor signaling and NF-kappa B signaling. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, KyotoEncyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

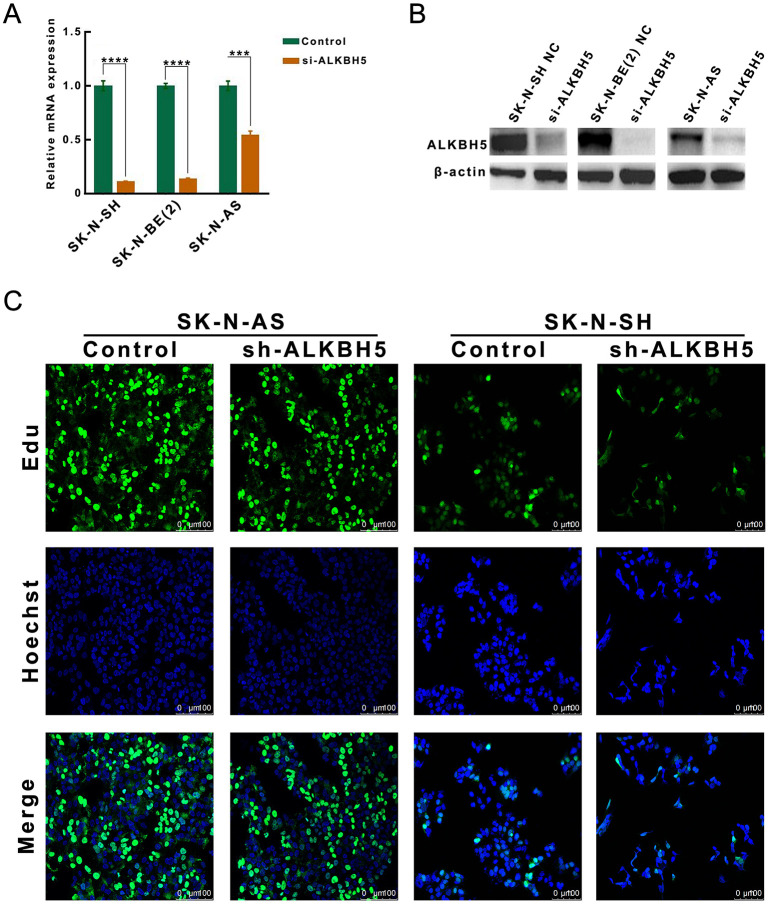

ALKBH5 promotes neuroblastoma cell proliferation and invasion

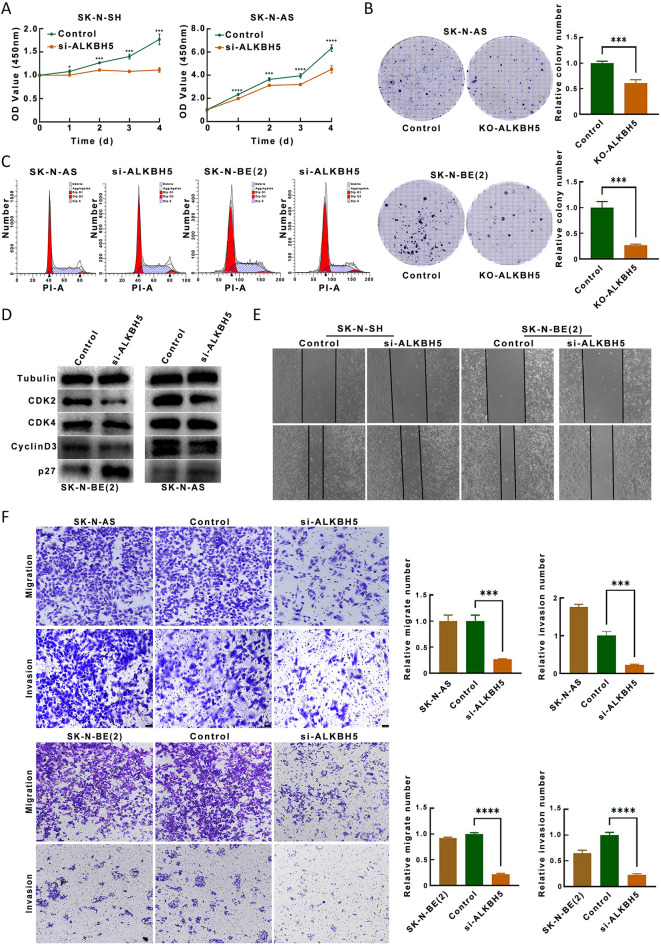

Due to the high expression of ALKBH5 in patients with advanced neuroblastoma, we investigated the relationship between ALKBH5 expression and neuroblastoma cell invasiveness. We first determined the interference efficiency of the siRNA targeting ALKBH5. The results of RT-qPCR and Western blotting analysis consistently showed that ALKBH5 mRNA and protein expression were significantly decreased in neuroblastoma cell lines with ALKBH5 knockdown compared with the corresponding control cells (Supplementary Figure S3A,B). Cell proliferation assays using the CCK-8 kit showed that two si-ALKBH5 neuroblastoma cell lines (SK-N-SH, SK-N-AS) had significantly reduced numbers of viable cells compared to the corresponding control neuroblastoma cells (Figure 3A). The effect of ALKBH5 expression on long-term neuroblastoma cell proliferation was determined by a colony formation assay. After two weeks, we observed that ALKBH5 knockdown significantly reduced the efficiency of clone formation (Figure 3B). The EdU incorporation assay also showed that the proliferation of neuroblastoma cell lines with knockdown of ALKBH5 was inhibited (Supplementary Figure S3C). Flow cytometric analysis further demonstrated that the proportion of cells in G2/M phase were increased after perturbing ALKBH5 expression (Figure 3C). Inhibition of ALKBH5 reduced the expression of CDK2, CDK4 and cyclinD3 and increased the expression of p27 (Figure 3D). The wound closure ability of the two cell lines with inhibited ALKBH expression [SK-N-SH, SK-N-BE(2)] was decreased compared to that of the corresponding control cells (Figure 3E). Consistent with these findings, these ALKBH5-knockdown neuroblastoma cells had decreased migratory and invasive abilities (Figure 3F). Taken together, these findings suggest that ALKBH5 exerts tumorigenic effects.

Figure S3.

Construction of ALKBH5 knockdown neuroblastoma cells. (A) Results of RT-qPCR analysis showed that ALKBH5 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in ALKBH5 knockdown neuroblastoma cell lines compared with the control group; (B) Western blotting data showed that ALKBH5 knockdown neuroblastoma cell lines had significantly reduced ALKBH5 protein expression; (C) EdU analysis also showed that proliferation of neuroblastoma cell lines with knockdown of ALKBH5 expression was inhibited. RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 3.

ALKBH5 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of neuroblastoma cells. (A) CCK-8 assay showed that two neuroblastoma cell lines (si-ALKBH5) that interfered with ALKBH5 expression had significantly reduced rates of viable cell proliferation; (B) Colony formation assay (plate colony formation assay) was performed to evaluate the long-term proliferation of neuroblastoma cells with knockdown of ALKBH5 expression; (C) Flow cytometric analysis revealed an increased proportion of cells in G2/M phase after the downregulation of ALKBH5 expression; (D) Inhibition of ALKBH5 increased the expression of CDK2 and CDK4 and decreased the expression of p27; (E) Two cell lines that inhibited ALKBH expression [SK-N-SH, SK-N-BE(2)] had reduced wound closure ability compared to controls (Magnification 10×); (F) Downregulation of ALKBH5 inhibits neuroblastoma cell migration and invasion (Magnification 10×). CCK-8, cell counting kit-8. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

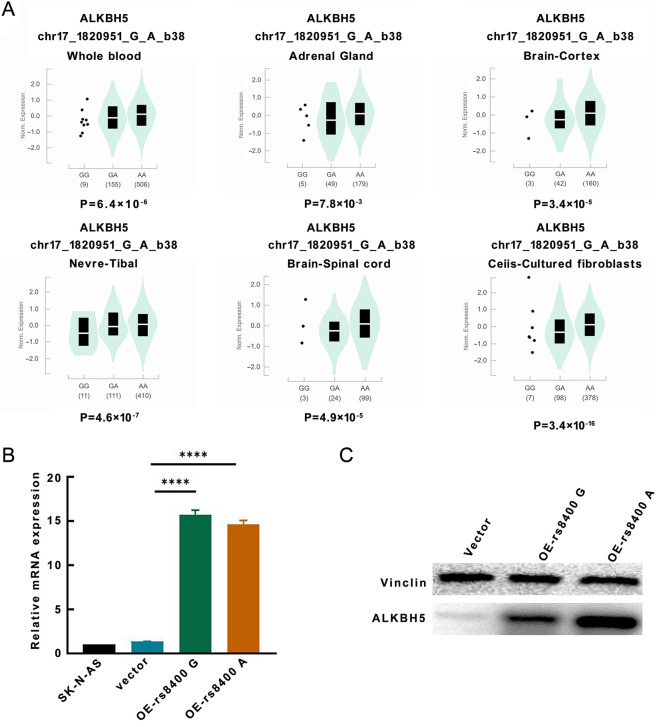

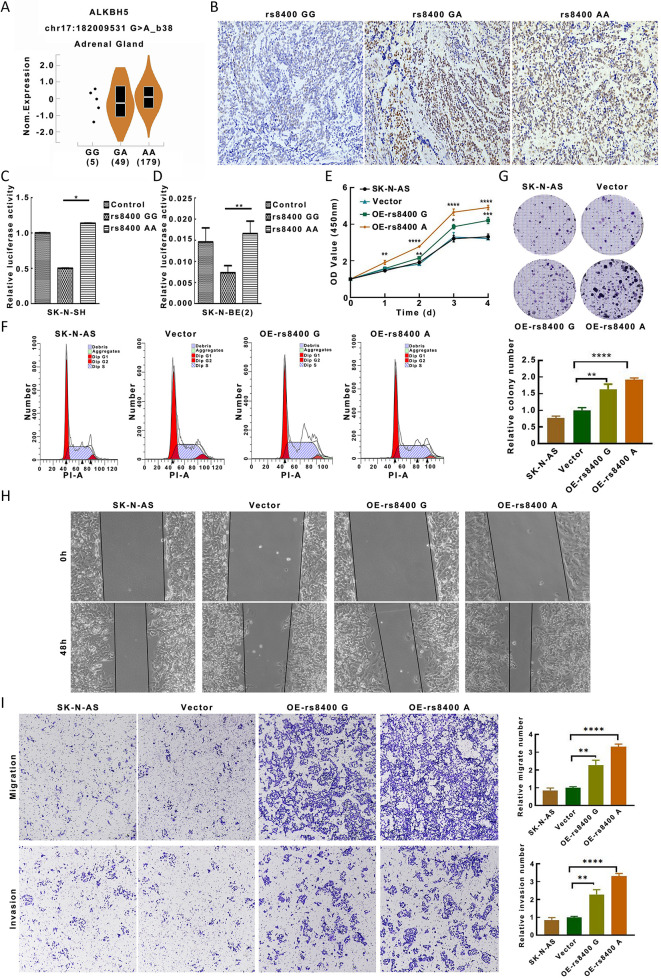

rs8400 A allele increases ALKBH5 level and is an oncogenic variant

To further investigate whether the functional polymorphism rs8400 affects ALKBH5 expression, we performed cis-eQTL analysis using newly published data from Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx). The results showed that individuals carrying the rs8400 A allele had significantly higher ALKBH5 mRNA levels in multiple tissue samples compared with individuals carrying the rs8400 G allele (Supplementary Figure S4A). The same results were found in adrenal tissues, which are often the origin of neuroblastoma (Figure 4A). The immunohistochemstry results also showed that tissue samples from individuals carrying the rs8400 A allele had higher ALKBH5 expression (Figure 4B). We then transfected the ALKBH5 3’-UTR fragment with the G or A allele into SK-N-SH and SK-N-BE(2) cells and showed that the rs8400 A allele significantly increased luciferase activity compared with the rs8400 G allele. It was proven that the rs8400 A allele resulted in enhanced expression of ALKBH5 (Figure 4C,D). To further characterize functional variants of rs8400, we first generated cell lines overexpressing rs8400 A allele and cell lines overexpressing rs8400 G allele. The expression of ALKBH5 in cell lines overexpressing rs8400 A allele and cell lines overexpressing rs8400 G allele was measured by RT-qPCR and Western blotting. The results showed that the mRNA and protein expression levels of ALKBH5 in the rs8400 A allele-overexpressing cell lines was higher than that in the rs8400 G allele-overexpressing cell lines or the control vector-transfected cell lines (Supplementary Figure S4B,C). Overexpression of rs8400 A allele significantly promoted the proliferation of neuroblastoma cells compared with overexpression of rs8400 G allele or expression of the control vector (Figure 4E). Flow cytometry revealed a higher proportion of cells in G2/M phase in neuroblastoma cells with rs8400 A allele relative to rs8400 G allele (Figure 4F). The colony formation assay further verified that rs8400 A allele-overexpressing cells formed the most colonies (Figure 4G). The wound closure ability of cells with stable overexpression of rs8400 A allele was increased compared with that of cells with stable overexpression of rs8400 G allele, cells transfected with the control vector or cells in the untreated blank group (Figure 4H). Compared with stable overexpression of rs8400 G allele or transfection of the control vector, stable overexpression of rs8400 A allele also significantly enhanced the migration and invasion abilities of SK-N-AS cells (Figure 4I). In conclusion, these findings suggest that the rs8400 G>A SNP can lead to increased expression of ALKBH5 and thus have tumorigenic effects.

Figure S4.

Relationship between rs8400 G>A and ALKBH5 expression was analyzed by cis-eQTL. (A) Compared with rs8400 G genotype, individuals with rs8400 A allele had significantly higher ALKBH5 mRNA levels in the whole blood and adrenal gland, with consistent results in other tissues (cerebral cortex, tibial nerve, cervical vertebra C1 of the spinal cord and cultured fibroblasts); (B) RT-qPCR results showed that mRNA expression of ALKBH5 in cell lines overexpressing rs8400 A allele was higher than that in cell lines overexpressing rs8400 G allele or control vector; (C) Western blotting results showed that in cell lines overexpressing rs8400 A allele, the protein expression of ALKBH5 was higher than that in the cell lines overexpressing rs8400 G or the control vector. eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci. ****, P<0.0001.

Figure 4.

rs8400 A allele increases ALKBH5 levels and promotes neuroblastoma cancer progression. (A) In adrenal tissues, individuals with rs8400 AA genotype had statistically higher levels of ALKBH5 mRNA than those with rs8400 GG or GA genotype; (B) Immunohistochemistry results show that tissue samples with the rs8400 A allele have higher ALKBH5 expression relative to rs8400 G allele (Magnification 10×); (C,D) Luciferase activity was significantly reduced in SK-N-SH (C), SK-N-BE(2) (D) cells with the rs8400 G allele construct compared with the construct with the rs8400 A allele; (E) Overexpression of rs8400 A significantly promoted neuroblastoma cell proliferation compared to overexpression of rs8400 G or the control vector; (F) Flow cytometry showed a higher proportion of cells in G2/M phase in neuroblastoma cells with rs8400 A allele relative to rs8400 G allele; (G) Colony formation experiments further demonstrated that rs8400 A-overexpressing cells had the most colonies; (H) Wound closure ability of stably overexpressed rs8400 A allele was increased compared with stably overexpressed rs8400 G allele or control vector or blank group without any treatment (Magnification 10×); (I) Stable overexpression of rs8400 A also significantly promoted the migration and invasion abilities of SK-N-AS cells compared with stably overexpressed rs8400G or control vector or blank group (Magnification 10×). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

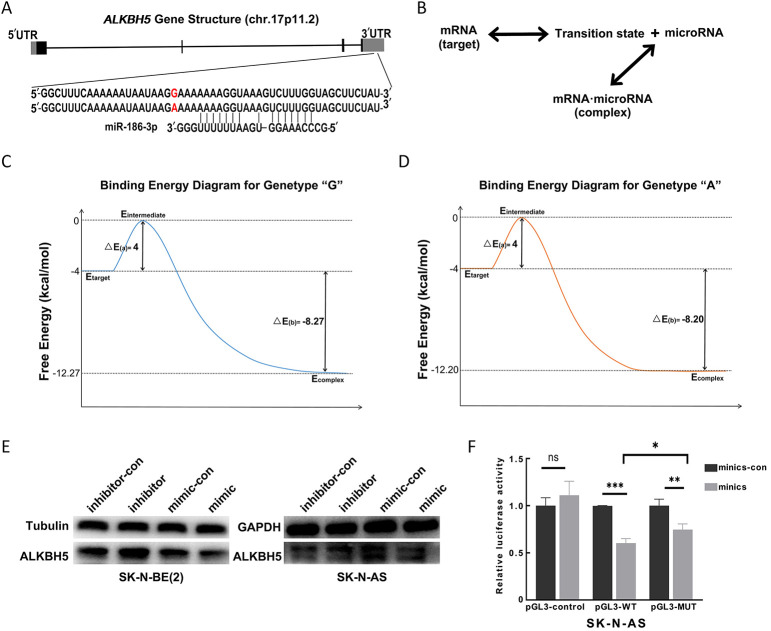

rs8400 G>A SNP, located in miR-186 binding site, is a functional regulatory site

In order to explore the reason that the G>A base substitution in rs8400 leads to a change in ALKBH5 expression, we first used the miRNA target prediction software miRanda (Version 3.3a; Memorial Sloan Kettering, USA) to find that the ALKBH5 3’-UTR contains a hypothetical binding site for miR-186-3p (47) (Figure 5A,B). Through the RNAfold and RNAcofold web servers, we found that the rs8400 G>A substitution changes the local folding structure and free energy of ALKBH5. This means that the G>A substitution in rs8400 may destroy the binding site of miR-186-3p, resulting in a decrease in the ability of miR-186-3p to bind to the 3’-UTR of ALKBH5 (Figure 5C,D). Then, we further verified the effect of miR-186-3p on the expression of ALKBH5 in vitro. MiR-186-3p mimics or inhibitors were transfected into SK-N-BE(2) and SK-N-AS cells, and the expression of the ALKBH5 protein was evaluated. The Western blotting results showed that inhibition of miR-186-3p promoted the expression of ALKBH5, while an increase in the miR-186-3p level inhibited the expression of ALKBH5 (Figure 5E). This indicates that miR-186-3p inhibits ALKBH expression.

Figure 5.

SNP rs8400 A/G causes different binding abilities of miR-186-3p to ALKBH5 3’UTR. (A) We found the binding sites for ALKBH5 3’-UTR and miR-186-3p by prediction software (Bartel, 2009); (B) When a miRNA binds to a target, the target first transitions to an intermediate state by unraveling the seed target nucleotides, and then forms a complex upon binding to the miRNA; (C,D) Using RNAfold and RNAcofold WebSever, we found that the rs8400 A allele (D) binds miR-186-3p to a reduced capacity compared with the rs8400 G allele (C); (E) Western blotting results showed that inhibiting miR-186-3p could promote expression of ALKBH5, and increasing miR-186-3p could inhibit the expression of ALKBH5; (F) Luciferase analysis showed that miR-186-3p could bind to the 3’-UTR of ALKBH5 gene, and rs8400 A allele reduced the binding ability of miR-186 to the 3’-UTR. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

We further verified the difference in the miRNA binding ability between different genotypes by a luciferase reporter assay. The reporter plasmid containing the G or A allele was transiently transfected with the miR-186 mimic or NC (or inhibitor or NC) into SK-N-AS cells, and the relative activity of firefly luciferase compared with Renilla luciferase was determined. The results showed that the luciferase activity in cells transfected with the miR-186-3p mimics was decreased, and the decrease was more obvious in cells with the G allele than in cells with the A allele (Figure 5F). This proves miR-186-3p has a weaker ability to bind to ALKBH5 with rs8400 A allele than to ALKBH5 with rs8400 G allele. This shows that the rs8400 G>A substitution reduces the inhibitory effect of miR-186-3p on ALKBH expression and increases the expression of ALKBH5.

SPP1 was identified as downstream target of ALKBH5

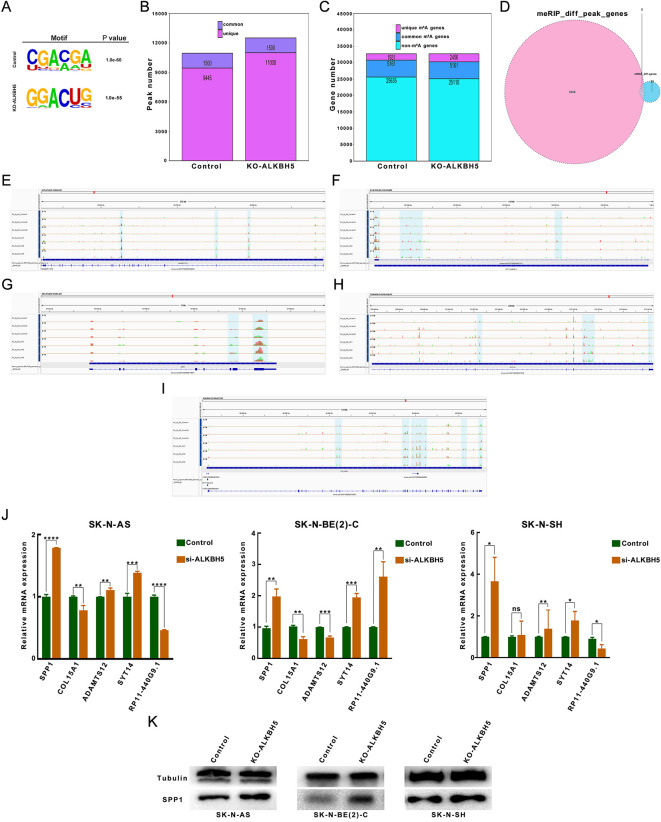

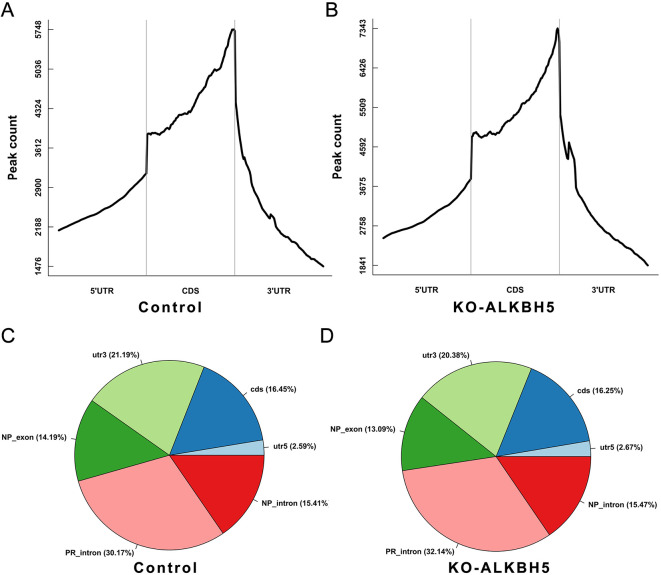

In order to comprehensively explore the methylation mode of ALKBH5, we knocked out ALKBH5 in the SK-N-AS cell line and performed MeRIP-seq analysis on the ALKBH5-knockdown group and the control group. Data analysis showed that the m6A consensus motif (GGAC) was highly abundant in SK-N-AS cells (Figure 6A) and enriched near stop codons (Supplementary Figure S5A,B). Compared with that in the control group, the m6A modification landscape in the ALKBH5 knockdown group showed slight changes in the distribution across different elements of the gene (Supplementary Figure S5C,D). Analysis of m6A peaks showed that there were 10,945 and 12,508 peaks in ALKBH5-knockdown and control cells, respectively, and that 1,500 of them overlapped (Figure 6B). In ALKBH5-knockdown and control cells, there were 7,092 and 7,617 genes associated with peaks, respectively, and 1,931 and 2,465 uniquely associated genes, respectively (Figure 6C). We focused on the genes whose methylation patterns and expression levels were regulated by ALKBH5. Therefore, we further intersected the differential peak-associated genes identified by m6A-seq with the differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-seq to obtain five genes related to the ALKBH5 effect, namely, SPP1, COL15A1, ADAMTS12, SYT14, and RP11-440G9.1 (Figure 6D). When ALKBH5 was knocked down, the m6A peaks of these target genes were significantly increased (Figure 6E−I). Moreover, these relationships were initially validated by RT-qPCR in ALKBH5 knockdown cells. We found that SPP1 was negatively regulated by ALKBH5 in the three cell types, with significant and consistent differences (Figure 6J). This was further verified by Western blotting, which showed that the expression of SPP1 increased when ALKBH5 was knockdowned (Figure 6K). In conclusion, SPP1 may be the direct downstream target of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma.

Figure 6.

SPP1 is identified as a downstream target of ALKBH5. (A) m6A consensus motif of GGAC is highly concentrated in SK-N-AS cells; (B) The study of m6A peaks showed that there were 12,508 and 10,945 in control cells and ALKBH5 knockdown, respectively, of which 1,500 were common; (C) There were 7,092 and 7,617 genes associated with the peak, with 1,931 and 2,465 uniquely associated genes, respectively; (D) Among the shared genes of differential peak-related genes of m6A-seq and differential genes of RNA-seq, there are 5 genes related to the ALKBH5 effect, namely SPP1, COL15A1, ADAMTS12, SYT14 and RP11-440G9.1; (E-I) When ALKBH5 was knocked down, m6A modification peak of the target gene was significantly increased; (J,K) RT-qPCR (J) and Western blotting (K) analysis demonstrated that SPP1 is inversely regulated by ALKBH5 in three cell types with significant differences. RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR. *, P <0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure S5.

Distribution and counts of m6A peaks in control and knockout ALKBH groups. (A,B) m6A peak counts in control (A) and knockout ALKBH5 (B) groups; (C,D) Distribution of m6A peaks in control (C) and knockout ALKBH5 (D) groups. m6A, N6-methyladenosine.

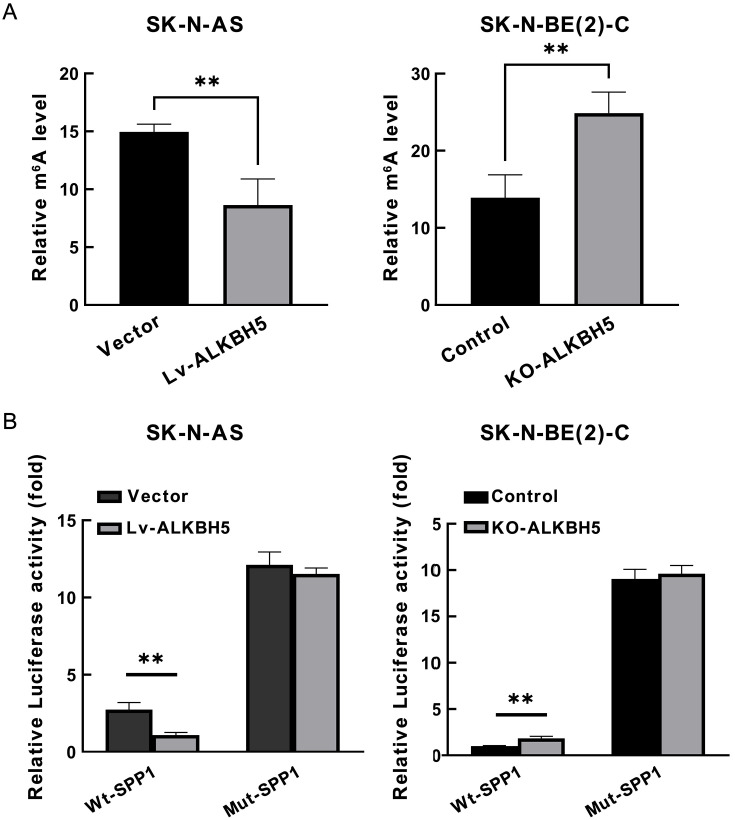

ALKBH5 downregulates SPP1 mRNA expression by m6A modification

We identified the m6A site in the SPP1 gene with significantly differential modification through MeRIP-seq. MeRIP-qPCR for this significant site confirmed the demethylation of SPP1 mRNA mediated by ALKBH5. Overexpression of ALKBH5 significantly reduced the m6A level of PER1 in the exon, while knockdown of ALKBH5 resulted in increased m6A modification of PER1 (Figure 7A). To further verify the regulatory effect of m6A modification on SPP1 expression, we substituted the adenosine (A) in the significantly differential m6A site in the SPP1 gene with cytosine (C) and constructed a mutant SPP1 fragment resistant to m6A modification. The luciferase activity of the wild-type (WT) SPP1 fragment was much lower than that of the mutant (mut) fragment. In addition, luciferase activity was decreased in ALKBH5 overexpressing cells and increased in cells with knockdown of ALKBH5 expression relative to controls (Figure 7B). Therefore, the mRNA level of SPP1 is regulated by m6A modification mediated by ALKBH5.

Figure 7.

ALKBH5 decreases SPP1 mRNA levels in an m6A manner. (A) MeRIP-qPCR detected m6A modification of SPP1. Compared with the control group, the overexpression of ALKBH5 inhibited m6A abundance of SPP1 mRNA, and increased m6A abundance of SPP1 mRNA after ALKBH5 was knocked out; (B) Detected the luciferase activity of SPP1 wild type and mutant type in overexpressed or knockdown ALKBH5 cells, respectively. MeRIP-qPCR, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation quantitative polymerase chain reaction; **, P<0.01.

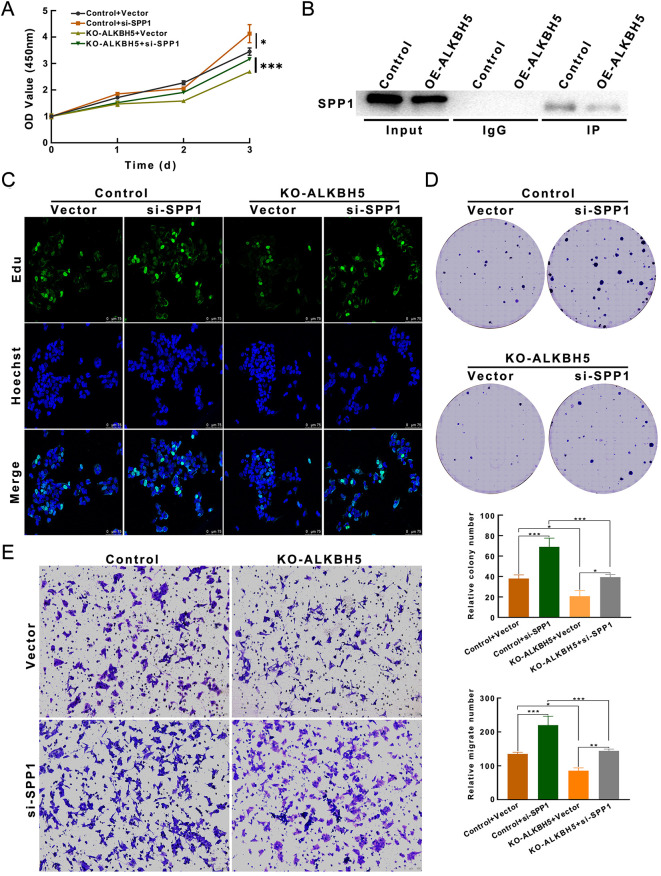

Oncogenic effect of ALKBH5 is reversed by overexpression of SPP1

To confirm that the observed phenotype is mediated by dysregulation of the ALKBH5-SPP1 axis, we performed several functional rescue assays. CCK-8, EdU, and colony formation assays showed that SPP1 silencing promoted the malignant progression of neuroblastoma cells and partially reversed the reduction in neuroblastoma cell proliferation induced by ALKBH5 knockdown (Figure 8A,C,D). Knockdown of SPP1 also significantly abolished the attenuation of motility and invasion induced by ALKBH5 loss (Figure 8E). In addition, the coprecipitation of ALKBH5 and SPP1 in coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments fully demonstrated their interaction (Figure 8B). In conclusion, abnormal SPP1 expression may be responsible for ALKBH5-mediated proliferation or migration of neuroblastoma cells.

Figure 8.

Oncogenic effects of ALKBH5 were reversed by overexpression of SPP1. (A) CCK-8 showed that SPP1 expression inhibition promoted neuroblastoma cell progression and partially reversed ALKBH5 knockdown-induced reduction in neuroblastoma proliferation; (B) Co-precipitation results in Co-IP experiments indicated that ALKBH5 interacts with SPP1; (C,D) EdU (C) and colony (D) assays showed that inhibition of SPP1 expression promoted neuroblastoma cell proliferation and could partially reverse the decreased proliferation of neuroblastoma cells caused by ALKBH5 knockdown; (E) Knockdown of SPP1 also significantly abolished the reduced invasiveness caused by ALKBH5 deletion (Magnification 20×). CCK-8, cellcounting kit-8; Co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

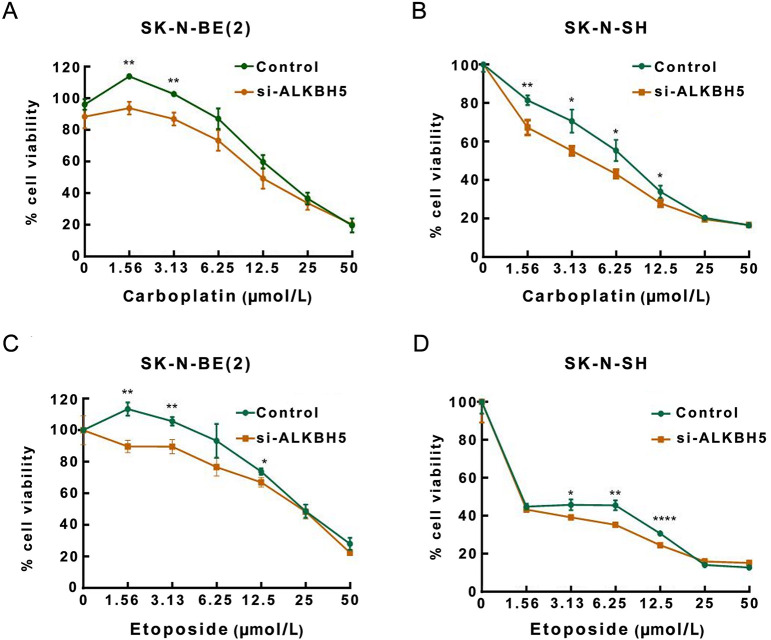

ALKBH5 inhibition potentiates effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on neuroblastoma cells

To further investigate the clinical significance of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma treatment, we explored whether ALKBH5 inhibition affects the therapeutic effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on neuroblastoma cells. We hypothesized that inhibition of ALKBH5 expression would affect the sensitivity of neuroblastoma cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. We studied six chemotherapeutic drugs (cyclophosphamide, carboplatin, etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) commonly used in patients with neuroblastoma (5,47,48). We performed in vitro drug susceptibility experiments for verification. We added different concentrations of the chemotherapeutic drugs to the experimental group of neuroblastoma cells with knockdown of ALKBH5 expression and the untreated control group of neuroblastoma cells, respectively. Cell viability was measured by a CCK-8 assay after 72 h of incubation. It was observed that the number of viable cells decreased significantly in all neuroblastoma cell groups with increasing concentrations of the chemotherapeutic drugs. Compared with the control groups, the number of viable cells in the ALKBH5 knockout groups was significantly reduced after incubation with the same low concentration of two chemotherapeutic drugs (carboplatin and etoposide) (Figure 9). That is, the sensitivity of ALKBH5 knockout neuroblastoma cells to carboplatin and etoposide was significantly increased. These results suggest that ALKBH5 inhibition can enhance the anticancer effects of some chemotherapeutic drugs.

Figure 9.

ALKBH5 inhibition promotes therapeutic effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on neuroblastoma cells. (A,B) SK-N-BE(2) (A) and SK-N-SH (B) neuroblastoma cell lines with ALKBH5 knockdown were significantly more sensitive to low doses of carboplatin compared to controls; (C,D) SK-N-BE(2) (C) and SK-N-SH (D) cell lines with ALKBH5 knockdown were significantly more sensitive to low doses of etoposide compared to control. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ****, P<0.0001.

Discussion

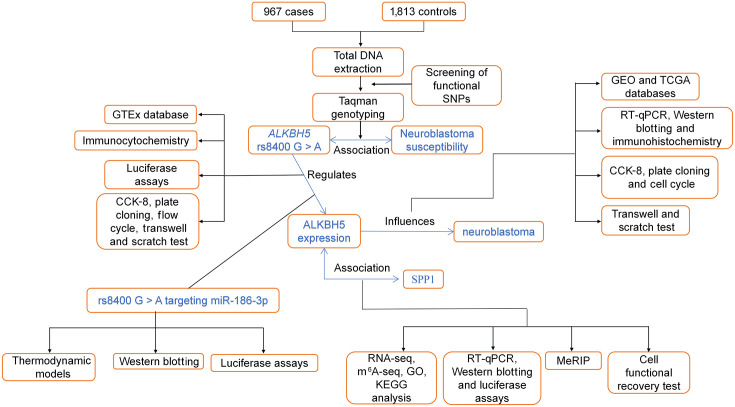

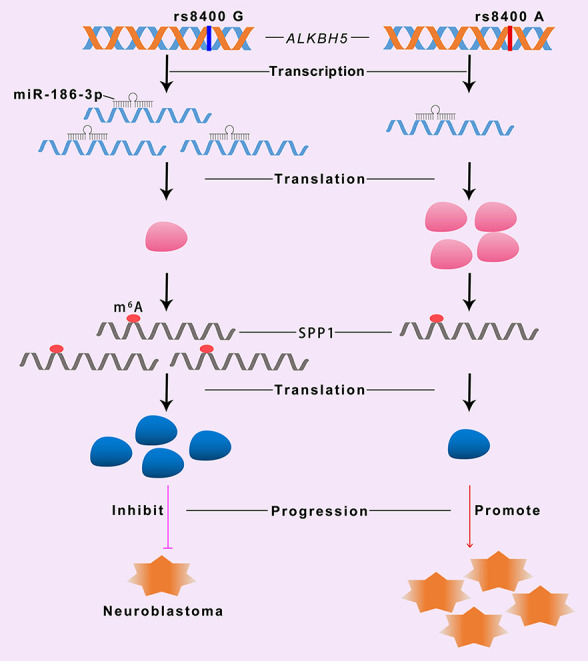

Neuroblastoma is the most common tumor in infants and young children, accounting for about 15% of all childhood cancers (49). In recent years, with the in-depth study of neuroblastoma, the prognosis of patients has improved to some extent, and the five-year survival rate has increased from 52% to 74% (1). However, this has been attributed to increased cure rates for patients with benign neuroblastoma. However, there has been little effect on the cure rate of patients with high-risk neuroblastoma. Therefore, understanding the molecular features and genetic variants involved in the pathogenesis of neuroblastoma is essential for the development of tools for early diagnosis and precision treatment. In our study, we identified an ALKBH5 SNP, rs8400, associated with neuroblastoma risk. It is in the microRNA-binding region on chromosome 17q11.2, and the risk of rs8400 A allele corresponds to higher ALKBH5 gene expression. We proved that the rs8400 G>A SNP resulted in decreased binding of a microRNA to ALKBH5 and promoted its expression, leading to accumulation of ALKBH5. ALKBH5 upregulation resulted in enhancement of the proliferation, migration and invasion of cancer cells. SPP1 was selected as the downstream target gene by RNA-seq combined with MeRIP-seq, and downregulation of SPP1 was found to restore the tumor-suppressive effect of ALKBH5 downregulation. In addition, we further investigated the therapeutic effect of ALKBH5 knockdown combined with common chemotherapeutic drugs on neuroblastoma in vitro, and the results showed that the effects of carboplatin and etoposide were enhanced in ALKBH5 knockdown cells. Our workflow is shown in Supplementary Figure S6. This study has greatly expanded the understanding of neuroblastoma mechanisms by revealing that genetic variants located in microRNA binding sites contribute to neuroblastoma-associated phenotypes by affecting the expression of their host genes. ALKBH5 gene may also be a potential new therapeutic target for neuroblastoma (Figure 10).

Figure S6.

Workflow of current study. GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; ALKBH5, AlkB homolog 5; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; MeRIP, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation.

Figure 10.

rs8400 G>A of ALKBH5 gene affects binding of miR-186-3p to the ALKBH5 binding site, making miR-186-3p unable to inhibit expression of ALKBH5, resulting in upregulation of its mRNA and protein levels. Upregulation of ALKBH5 further inhibited downregulation of tumor suppressor gene SPP1 and promoted progression of neuroblastoma.

m6A modification regulates a variety of cellular processes, including RNA stability, splicing, translation and biogenesis (50,51). Accumulating evidence suggests that aberrant m6A modification is closely related to the pathogenesis of many cancers (52-54). Although the importance of m6A modification-related genes in cancer is highly appreciated, the study of SNPs in m6A modification-related genes is a newly emerging field. However, the information regarding the SNPs in ALKBH5 gene is still limited. Only recently has it been recognized that SNPs in the ALKBH5 gene contribute to genetic susceptibility to cancer. In 2019, Meng et al. published the first case-control study on SNPs in m6A modification-related genes and colorectal cancer risk. They comprehensively genotyped 240 SNPs in 20 m6A modification-related genes in the Chinese population. However, all the analyzed ALKBH5 SNPs (rs2124370, rs8400, rs9899249, rs9913266 and rs2925137) could not predispose individuals to colorectal cancer (55). We previously genotyped two SNPs (rs1378602 and rs8400) in the ALKBH5 gene to determine whether they are associated with Wilms tumor susceptibility in a large multi-center case-control study. No SNP contributed to Wilms tumor susceptibility. Stratification analysis did reveal some significant relationships between these SNPs and Wilms tumor risk in certain subgroups, indicating a weak influence of ALKBH5 gene SNPs on susceptibility to Wilms tumor (56). In this study, we identified rs8400 A allele as being significantly associated with the risk of neuroblastoma and as the first ALKBH5 locus robustly associated with the risk of neuroblastoma in individuals of Chinese ancestry, and we further explored the biological significance and molecular mechanism of the SNP rs8400.

miRNAs have crucial effects on mRNA deadenylation, mRNA decay, and mRNA translation inhibition by binding to the 3’-UTRs of most protein-coding genes (57). Previous studies have demonstrated that miRNAs are involved in tumorigenesis and tumor development by affecting tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion and angiogenesis (58). Neviani et al. previously demonstrated that natural killer cell-derived exosomal miR-186 is downregulated in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma and that its low expression is a poor prognostic factor. They further demonstrated that miR-186 could inhibit the growth of neuroblastoma by targeting MYCN and AURKA (59). miR-186 also exerts inhibitory effects on neuroblastoma by targeting the 3’-UTR of Eg5 (60) and MAP3K2 (61). As predicted by miRBase and TargetScan, miR-186-3p was identified as a potential miRNA targeting rs8400 of ALKBH5. miR-186-3p negatively regulated the expression of the ALKBH5 gene, but this regulatory effect disappeared when the G nucleotide in rs8400 was mutated to A. We describe a possible mechanism of abnormal oncogene expression caused by genetic variation.

ALKHB5 is a key m6A demethylase that can remove m6A (30). A decreased ALKBH5 level was detected in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and associated with worse survival in HCC patients. ALKBH5 functions as a tumor suppressor in HCC cells by inhibiting LY6/PLAUR Domain Containing 1 (LYPD1) via an m6A-dependent mechanism (62). ALKBH5 was found to impair the progression of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by reducing YAP expression and activity (63). ALKBH5 also functions as an oncogene in other specific types of cancer. ALKBH5 can upregulate FOXM1 gene expression and promote the self-renewal and proliferation of glioblastoma stem-like cells (GSCs) (33). Increased ALKBH5 expression serves as a marker for poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patients. Mechanistically, ALKBH5 plays a tumorigenic role in AML by posttranscriptional regulation of critical targets such as TACC3 (64). The dual role of ALKBH5, which has different effects in different tumors, depends on tissue specificity and different downstream molecular mechanisms. In our study, we found that the ALKBH5 gene was frequently amplified and upregulated in high-grade neuroblastoma and that ALKBH5 promoted the malignant progression of neuroblastoma by inhibiting the expression of SPP1, suggesting that ALKBH5 is an important oncogene in neuroblastoma.

Although the downstream target genes of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma have been explored, the detailed mechanism by which SPP1 inhibits the occurrence and development of neuroblastoma remains unknown. We have provided a large amount of evidence on the function of ALKBH5 in tumorigenesis, but our work still has some limitations. For example, ALKBH5 is a methyltransferase; whether it acts through m6A modification, and if so, which reader proteins are involved, are unknown and need further study.

To investigate the clinical significance of ALKBH5 in neuroblastoma, we conducted a preliminary drug sensitivity test to study the therapeutic effects of six common chemotherapeutic drugs on neuroblastoma. Our study found that carboplatin and etoposide combined with ALKBH5 inhibition had a good therapeutic effect on neuroblastoma cells, suggesting that ALKBH5 could be used as a clinical therapeutic target for neuroblastoma. The clinical significance of ALKBH5 needs further study.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that a SNP in ALKBH5 gene (rs8400 G>A) was significantly associated with the risk of neuroblastoma. The rs8400 G>A SNP causes an imbalance in the negative regulatory effect of miR-186-3p and further causes abnormal expression of ALKBH5. Dysregulation of the ALKBH5-SPP1 axis can promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of neuroblastoma cells. The role of the miR-186-ALKBH5-SPP1 axis in neuroblastoma was revealed.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82002635, 82002636 and 82173593); Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (No. 202102021227 and 202102020421); the Science Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen (No. JCYJ20220531093213030); and Guangzhou Municipal Basic Research Program Joint Funding of City and Hospitals (No. 202201020622).

Contributor Information

Jing He, Email: hejing198374@gmail.com.

Zhenjian Zhuo, Email: zhenjianzhuo@163.com.

References

- 1.Maris JM Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tas ML, Reedijk AMJ, Karim-Kos HE, et al Neuroblastoma between 1990 and 2014 in the Netherlands: Increased incidence and improved survival of high-risk neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;124:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman EA, Abdessalam S, Aldrink JH, et al Update on neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung NK, Dyer MA Neuroblastoma: developmental biology, cancer genomics and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrc3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almstedt E, Elgendy R, Hekmati N, et al Integrative discovery of treatments for high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Commun. 2020;11:71. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13817-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito MR, Aveic S, Seydel A, et al Neuroblastoma treatment in the post-genomic era. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:14. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0319-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barr EK, Applebaum MA. Genetic predisposition to neuroblastoma. Children (Basel) 2018;5:119.

- 8.Zhong X, Liu Y, Liu H, et al Identification of potential prognostic genes for neuroblastoma. Front Genet. 2018;9:589. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonini GP, Capasso M Genetic predisposition and chromosome instability in neuroblastoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39:275–85. doi: 10.1007/s10555-020-09843-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trochet D, Bourdeaut F, Janoueix-Lerosey I, et al Germline mutations of the paired-like homeobox 2B (PHOX2B) gene in neuroblastoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:761–4. doi: 10.1086/383253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa S, Takita J, Sanada M, et al Oncogenic mutations of ALK in neuroblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:302–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aygün Z, Batur Ş, Emre Ş, et al Frequency of ALK and GD2 expression in neuroblastoma. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2019;38:326–34. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2019.1588439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pugh TJ, Morozova O, Attiyeh EF, et al The genetic landscape of high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:279–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qadeer ZA, Valle-Garcia D, Hasson D, et al ATRX in-frame fusion neuroblastoma is sensitive to EZH2 inhibition via modulation of neuronal gene signatures. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:512–27.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady SW, Liu Y, Ma X, et al Pan-neuroblastoma analysis reveals age- and signature-associated driver alterations. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5183. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18987-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peifer M, Hertwig F, Roels F, et al Telomerase activation by genomic rearrangements in high-risk neuroblastoma. Nature. 2015;526:700–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valencia-Sama I, Ladumor Y, Kee L, et al NRAS status determines sensitivity to SHP2 inhibitor combination therapies targeting the RAS-MAPK pathway in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2020;80:3413–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YN, LaMarche MJ, Chan HM, et al Allosteric inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase inhibits cancers driven by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature. 2016;535:148–52. doi: 10.1038/nature18621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung IY, Cheung NV, Modak S, et al Survival impact of anti-GD2 Antibody Response in a Phase II ganglioside vaccine trial among patients with high-risk neuroblastoma with prior disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:215–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capasso M, Diskin S, Cimmino F, et al Common genetic variants in NEFL influence gene expression and neuroblastoma risk. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6913–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capasso M, McDaniel LD, Cimmino F, et al The functional variant rs34330 of CDKN1B is associated with risk of neuroblastoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3224–30. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diskin SJ, Capasso M, Schnepp RW, et al Common variation at 6q16 within HACE1 and LIN28B influences susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1126–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDaniel LD, Conkrite KL, Chang X, et al Common variants upstream of MLF1 at 3q25 and within CPZ at 4p16 associated with neuroblastoma. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oldridge DA, Wood AC, Weichert-Leahey N, et al Genetic predisposition to neuroblastoma mediated by a LMO1 super-enhancer polymorphism. Nature. 2015;528:418–21. doi: 10.1038/nature15540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maris JM, Mosse YP, Bradfield JP, et al Chromosome 6p22 locus associated with clinically aggressive neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2585–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao G, Li HB, Yin Z, et al Recent advances in dynamic m6A RNA modification. Open Biol. 2016;6:160003. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:313–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Weng H, Chen J The biogenesis and precise control of RNA m(6)A methylation. Trends Genet. 2020;36:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Zhang L, Zheng G, et al Crystal structure of the RNA demethylase ALKBH5 from zebrafish. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:892–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang B, Yang Y, Kang M, et al m6A demethylase ALKBH5 inhibits pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis by decreasing WIF-1 RNA methylation and mediating Wnt signaling. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:3. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1128-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Zhang C, Samanta D, Lu H, et al Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m6A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E2047–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602883113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, et al m6A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:591–606.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Y, Gong C, Li Z, et al Demethylase ALKBH5 suppresses invasion of gastric cancer via PKMYT1 m6A modification. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:34. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01522-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin S, Li M, Chang H, et al The m6A demethylase ALKBH5 promotes tumor progression by inhibiting RIG-I expression and interferon alpha production through the IKKε/TBK1/IRF3 pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:97. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01572-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo X, Li K, Jiang W, et al RNA demethylase ALKBH5 prevents pancreatic cancer progression by posttranscriptional activation of PER1 in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:91. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01158-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan K, Wu W, Zhu K, et al Identification and characterization of a glucometabolic prognostic gene signature in neuroblastoma based on N6-methyladenosine eraser ALKBH5. J Cancer. 2022;13:2105–25. doi: 10.7150/jca.69408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bian J, Zhuo Z, Zhu J, et al Association between METTL3 gene polymorphisms and neuroblastoma susceptibility: A nine-centre case-control study. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:9280–6. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuo Z, Lu H, Zhu J, et al METTL14 gene polymorphisms confer neuroblastoma susceptibility: An eight-center case-control study. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhuo ZJ, Liu W, Zhang J, et al Functional polymorphisms at ERCC1/XPF genes confer neuroblastoma risk in Chinese children. EBioMedicine. 2018;30:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing C, Lu XX, Guo PD, et al Ubiquitin-specific protease 4-mediated deubiquitination and stabilization of PRL-3 is required for potentiating colorectal oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:83–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin DY, Zeng D, Millikan R Maximum likelihood estimation of haplotype effects and haplotype-environment interactions in association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;29:299–312. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hua RX, Zhuo Z, Ge L, et al LIN28A gene polymorphisms modify neuroblastoma susceptibility: A four-centre case-control study. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:1059–66. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J, Wang MY, Qiu LX, et al. Genetic variations of mTORC1 genes and risk of gastric cancer in an Eastern Chinese population. Mol Carcinog 2013;52 Suppl 1:E70-9.

- 45.Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, et al Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carithers LJ, Moore HM The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13:307–8. doi: 10.1089/bio.2015.29031.hmm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearson AD, Pinkerton CR, Lewis IJ, et al High-dose rapid and standard induction chemotherapy for patients aged over 1 year with stage 4 neuroblastoma: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:247–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Pearson ADJ, et al Busulfan and melphalan versus carboplatin, etoposide, and melphalan as high-dose chemotherapy for high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NBL1/SIOPEN): an international, randomised, multi-arm, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:500–14. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zafar A, Wang W, Liu G, et al Molecular targeting therapies for neuroblastoma: Progress and challenges. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:961–1021. doi: 10.1002/med.21750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, et al N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560–4. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–20. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao BS, Wang X, Beadell AV, et al m6A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature. 2017;542:475–8. doi: 10.1038/nature21355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, et al METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65:529–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choe J, Lin S, Zhang W, et al mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature. 2018;561:556–60. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng Y, Li S, Gu D, et al Genetic variants in m6A modification genes are associated with colorectal cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:8–17. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hua RX, Liu J, Fu W, et al ALKBH5 gene polymorphisms and Wilms tumor risk in Chinese children: A five-center case-control study. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23251. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ha M, Kim VN Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Wang L, Chen C, et al New insights into the regulatory role of microRNA in tumor angiogenesis and clinical implications. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:22. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0766-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmittgen TD Exosomal miRNA cargo as mediator of immune escape mechanisms in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1293–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-19-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu K, Su Y, Xu B, et al MicroRNA-186-5p represses neuroblastoma cell growth via downregulation of Eg5. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:2245–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu K, Wang L, Zhang X, et al LncRNA HCP5 promotes neuroblastoma proliferation by regulating miR-186-5p/MAP3K2 signal axis. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56:778–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y, Zhao Y, Chen J, et al ALKBH5 suppresses malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-guided epigenetic inhibition of LYPD1. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:123. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01239-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin D, Guo J, Wu Y, et al m6A demethylase ALKBH5 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by reducing YTHDFs-mediated YAP expression and inhibiting miR-107/LATS2-mediated YAP activity in NSCLC. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:40. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen C, Sheng Y, Zhu AC, et al. RNA demethylase ALKBH5 selectively promotes tumorigenesis and cancer stem cell self-renewal in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Stem Cell 2020;27:64-80.e9.