Abstract

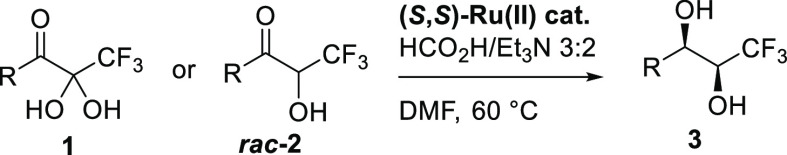

Stereopure CF3-substituted syn-1,2-diols were prepared via the reductive dynamic kinetic resolution of the corresponding racemic α-hydroxyketones in HCO2H/Et3N. (Het)aryl, benzyl, vinyl, and alkyl ketones are tolerated, delivering products with ≥95% ee and ≥87:13 syn/anti. This methodology offers rapid access to stereopure bioactive molecules. Furthermore, DFT calculations for three types of Noyori–Ikariya ruthenium catalysts were performed to show their general ability of directing stereoselectivity via the hydrogen bond acceptor SO2 region and CH/π interactions.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, DFT, drug design, fluorine, hydrogenation, kinetic resolution, ruthenium

Dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) is a powerful synthetic method for the conversion of stereoisomeric mixtures to valuable enantiomerically pure products. Efficient DKR relies on a fast dynamic interconversion of the starting material’s enantiomers and on a highly enantio-discriminating asymmetric transformation.1,2 Noyori–Ikariya type ruthenium catalysts for asymmetric transfer hydrogenation (ATH), for example C1–C8 (Figure 1a),3−8 were used in efficient DKR of several classes of complex ketones.9−11 Traditionally, the origin of enantioselectivity for the reduction of ketones with this type of catalyst has been associated with the CH/π interaction between an electron-deficient η6-arene ligand and π electrons of the ketone substrate.12 Configuration at the α-stereocenter during DKR-ATH was deemed to be controlled by the steric repulsion (Figure 1b),13−20 although this assertion was rarely supported by computational analysis.21,22

Figure 1.

(a) Representative Noyori–Ikariya precatalysts used in this work; (b) Traditional model of DKR-ATH stereoselectivity; and (c) Hydrogen bonding ability of the Noyori–Ikariya catalysts.

In 2019, we highlighted another region of the Noyori–Ikaria type ruthenium catalysts that can be involved in stereochemical control at the α-stereocenter during DKR-ATH, i.e., the SO2 moiety.8 Indeed, the two-point catalyst–substrate attraction between catalyst C8 and 2-acetamido-1-indanone was involved in the stabilization of the most favorable transition state: the commonly encountered CH/π interaction controlled the configuration at carbon-1 and configuration at carbon-2 was controlled by additional SO2/NHAc hydrogen bonding, delivering the unexpected trans product (Figure 1c, TS-I).8 This goes hand in hand with computational evidence that the SO2 region of the Noyori–Ikariya complexes contributes to enantioselectivity of acetophenone reduction by destabilization of the transition state leading to the minor stereomer via SO2/π repulsion.23,24

The rather niche ruthenium catalyst C8 based on the syn-ULTAM ligand25 outperformed the more common anti-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine-based catalysts for the reduction of α-acetamido benzo-fused ketones. Therefore, we wondered whether the hydrogen bonding ability during DKR-ATH is limited to C8 or is it a general feature of the Noyori–Ikariya family of ruthenium catalysts. Retrospectively, the hydrogen-bond-driven catalyst–substrate recognition might have been involved in DKR-ATH of other ketones with a hydrogen-bond donor α-substituent. In particular, DKR-ATH of linear α-(BocNH) arylketones afforded the unexpected enantiomer of omarigliptin intermediate,26,27 where the aromatic ring of the substrate was not involved in stabilization of the most favorable transition state (Figure 1c, TS-II). Furthermore, DKR-ATH of cyclic α-sulfonylamino ketones to the corresponding stereopure benzosultams employing C7′ exhibited exceptional diastereo- and enantioselectivity and turnover number, which points to the energetically favorable catalyst–substrate interaction (Figure 1c, TS-III).28

To verify the general ability of the Noyori–Ikaria-type ruthenium catalysts to control the stereochemical outcome during DKR-ATH via hydrogen bonding to the SO2 moiety, the transition state geometries TS-II and TS-III were calculated for the aforementioned literature reductions involving structurally distinct C5 and C7′ (Figure 1c). DFT calculations in Gaussian 1629 were performed at the M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p)+LANL2DZ level.30−32 In both cases, a strong hydrogen bond was confirmed (2.36 and 2.01 Å, respectively) in the most favorable configuration. Interestingly, for the reaction in Figure 1c, TS-II, three attractive interactions were identified: SO/NH, CH/π, and SO/(difluorophenyl). Also, in TS-III, a third attractive interaction was identified between η6-arene ligand of the catalyst C7′ and SO2 of the substrate. The coordinates and visualizations of TS-II and TS-III are reported in the Supporting Information (SI).

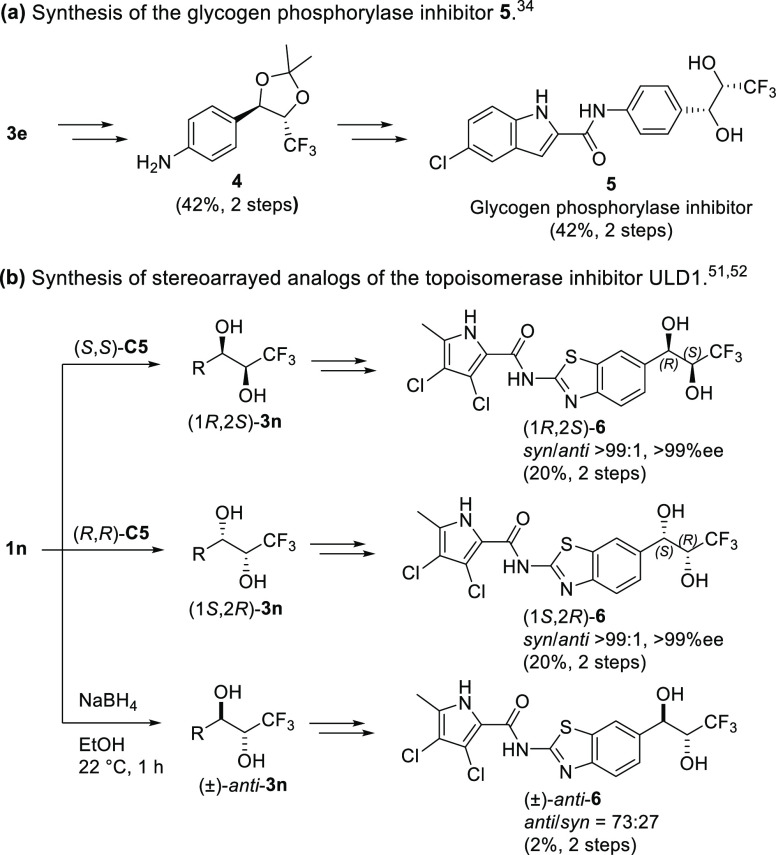

Hereafter we report an efficient asymmetric reduction of CF3-substituted 1,2-diketones 1 via DKR-ATH of intermediate α-hydroxy-α-CF3-ketones 2. The latter are another example of ketones with a hydrogen-bond donor α substituent that might interact with the SO2 region of the catalyst. The resulting diols syn-3 are valuable motifs in medicinal chemistry,33−36 but the literature reports on their asymmetric synthesis are limited to a few sporadic examples. Stereoselective synthesis of syn-3a (98% ee) was achieved via Sharpless dihydroxylation.37anti-1-(2-Naphthyl)-2-CF3-1,2-ethandiol (89% ee) was prepared in three steps from the asymmetric diazo-aldol reaction product.38 Asymmetric aldol reaction was employed for the synthesis of trifluoromethylated sugar analogues.39 The pegylated 1-vinyl-2-CF3-glycol (96% ee) was prepared via alkoxyallylboration of fluoral with “ate” complex.40

The model 1-phenyl-2-trifluoromethylethandione 1a in the form of a monohydrate was prepared from benzaldehyde via umpolung, acylation with trifluoroacetic anhydride, and hydrolysis.41 It was subjected to DKR-ATH using a range of Noyori–Ikariya-type ruthenium catalysts C1–C8, HCO2H/Et3N 3:2 as a source of hydrogen, and DMF as a cosolvent at 60 °C (Table 1). At a substrate/catalyst (S/C) ratio 1000, the reaction reached full conversion with tethered catalysts C4, C5, C7, and C8. The best stereoselectivity was achieved using HCO2H/Et3N in a 3:2 molar ratio, compared to 5:2 (azeotrope) and 3.4:2 (optimal for the reduction of benzils);42 see Table S1. The results with the most stereoselective catalysts C4 and C5 were back-to-back (Table S1), both achieving full conversion after 2 h (S/C = 1000) or 4 h (S/C = 2000). C5 displayed marginally better stereoselectivity, but both catalysts were considered in further studies. Apart from excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivity, the catalysts displayed an outstanding turnover frequency for the double reduction of 1a. As a comparison, the C5-catalyzed reduction of acetophenone (S/C = 1000, 60 °C) reached full conversion only after 3 h.5 And the C7-catalyzed stepwise double reduction of the homologous 1-phenyl-3-CF3-propan-1,3-dione (S/C = 1000, 60 °C) was finished in 20 h.13

Table 1. Catalyst Screening for Ru(II)-Catalyzed DKR-ATH of 1aa.

| Ru-cat. | Time | 1a:2a:3a | syn-3a/anti-3a | ee (syn) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (R,R)-C1 | 2 | 4:60:36 | 98:2 | |

| 18 | 0:41:59 | 95:5 | –91.3 | ||

| 2 | (S,S)-C2 | 2 | 0:44:56 | 87:13 | |

| 18 | 0:13:87 | 87:13 | 97.7 | ||

| 3 | (S,S)-C3 | 2 | 0:1:99 | 96:4 | |

| 18 | 0:1:99 | 96:4 | 99.1 | ||

| 4 | (S,S)-C4 | 1 | 0:25:75 | 96:4 | |

| 2 | 0:0:100 | 96:4 | 99.5 | ||

| 5 | (S,S)-C5 | 1 | 0:17:83 | 97:3 | |

| 2 | 0:0:100 | 97:3 | 99.8 | ||

| 6 | (R,R)-C6 | 2 | 0:18:82 | 98:2 | |

| 18 | 0:7:93 | 98:2 | –97.3 | ||

| 7 | (S,S)-C7 | 1 | 0:19:81 | 96:4 | |

| 2 | 0:0:100 | 96:4 | 98.5 | ||

| 8 | (3R,1′S)-C8 | 1 | 0:0:100 | 64:36 | –74.9 |

DKR-ATH of 1a (110 mg, 0.5 mmol) was carried out using the active hydride Ru(II) cat. (S/C = 1000, 0.5 μmol) prepared in situ from the corresponding monomeric (C1–C6) or μ-Cl dimeric (C7, C8) chloride precatalysts in HCO2H/Et3N (0.5 mL); with DMF (1 mL) as a cosolvent. 1a:2a:3a and syn-3a/anti-3a ratios were determined by 1H and 19F NMR analysis of reaction mixture aliquots, and ee of syn-3a by GC analysis using chiral stationary phase after extraction. For additional results, see Table S1.

We hypothesized that the efficient double reduction of 1a is driven by a favorable substrate–catalyst interaction involving hydrogen bonding between the OH group of the intermediate rac-2a and the SO2 group of the catalyst. Indeed, a kinetic study (Table S2) revealed that during the double reduction of diketone 1a, catalyzed by C4 at 40 °C, the first reduction is rate-determining; i.e., the intermediate monoalcohol 2a is reduced preferentially in the presence of 1a. To prove that dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of the intermediate stereochemically labile 2a is involved in the reduction process, the racemic 2a was subjected to transfer hydrogenation, and its reduction gave similar stereoselectivity to that of the reduction of 1a (SI, page S6). The enantiomeric ratio of 2a was essentially 1:1 during the course of the reaction starting from either 1a or 2a which points to its fast epimerization in the reaction medium. Rather surprisingly, the monoreduction of 1a to 2a is a noncatalyzed and reversible process: stirring 1a or 2a in the reaction medium without the catalyst at 60 °C resulted in a mixture of 1a and 2a in 5:95 and 1:99 ratio, respectively (see SI page S5). We computed a barrier of 18.0 kcal mol–1 for the HCO2H catalyzed dehydration of hydrate (geminal diol) 1a to diketone 1a′. Its further reduction to 2a by HCO2H without a catalyst was shown by DFT calculation to be strongly exothermic and entropically favored because of the formation of CO2 (ΔG = −29.8 kcal mol–1). This makes the overall dehydration of 1a and its reduction to 2a favorable (ΔG = −19.5 kcal mol–1). The 1a–2a redox equilibrium and keto–enol equilibrium21 of 2a contribute to DKR-enabling fast epimerization of 2a in the reaction medium. The enol form of 2a is only 4.8 kcal mol–1 less stable than the keto form when hydrogen bonding to HCO2H and Et3N is considered. The keto–enol tautomerization, where the hydrogen atom is transferred between the sp3-C atom and the adjacent carbonyl group, is kinetically inaccessible due to a high activation barrier of 57.6 kcal mol–1. However, the barrier is lowered to 18.2 kcal mol–1 when the reaction is catalyzed by HCO2H/Et3N. This guarantees a quick conversion between (R)-2a and (S)-2a.

Next, we wanted to prove the origin of enantioselectivity and reaction kinetics during DKR-ATH of rac-2a, catalyzed by the catalyst (S,S)-C4, by elucidating the structures of plausible transition state (TS) geometries and ascertaining the energetics of the reactions. In the reaction between rac-2a and the active form of Ru(II) catalyst (S,S)-C4, Cat–H2, four diastereomeric TS can exist, depending on the substrate enantiomer and the side of the attack. Moreover, a different prereaction complex (PrC) corresponds to each TS. Selectivity is thus governed by the stability of both TS and PrC. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Gibbs free energies for the reaction between rac-2a and the Ru(II) catalyst C4 active form and for catalyst regeneration with HCO2H, at 298.15 K and 1 atm, showing that the Si-face attack on the (S) enantiomer is most favorable. PrC = prereaction complex; TS = transition state.

First, we analyzed the relative stabilities of individual PrC. Leading up to the (1R,2S)-3a, (1R,2R)-3a, (1S,2S)-3a, and (1S,2R)-3a, their stabilities (calculated as Gibbs free energies relative to infinitely separated catalyst and substrate) are −7.0, −9.2, −5.2, and −0.9 kcal mol–1, respectively, at 298.15 K and 1 atm. Hence, the lower stability of their PrC alone can explain why (1S,2R)-3a is detected in traces (below 0.2%) and (1S,2S)-3a forms only in minute quantities (below 1.0%). Only (1R,2S)-3a and (1R,2R)-3a are expected to form in noticeable amounts.

The energies of the TS are 12.7, 17.1, 13.6, and 12.9 kcal mol–1 (relative to each corresponding PrC) for the formation of (1R,2S)-3a, (1R,2R)-3a, (1S,2S)-3a, and (1S,2R)-3a, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. A large difference in the energy of the TS en route to (1R,2S)-3a and (1R,1R)-3a explains why, despite having a slightly less stable PrC, the former will form much faster, which is consistent with experimentally observed syn-selectivity. The product ratio is estimated on the basis of the absolute energies of the TS only, and the following ratio is expected: 96.5:2.3:1.1:0.003 at 298.15 K (Figure 3), which is in reasonable agreement with the experimental data. The overall catalytic cycle for the reduction of both enantiomers of 2a to respective stereoisomers of 3a is energetically favored, as shown in Figure 2, due to the hydrogen transfer from HCO2H to the oxidized form of the catalyst. This hydrogen transfer is a quick step with a low barrier of 5 kcal mol–1 and a downhill Gibbs free energy (−18.2 kcal mol–1), because both contributions are favorable: the energy change is negative and the entropy is increased due to the formation of CO2. The overall catalytic cycle of (S)-2a + HCO2H → (1R,2S)-3a + CO2 is thus energetically downhill (−13.3 kcal mol–1).

Figure 3.

Optimized transition state (TS) geometries leading to the four stereomeric products of 3a via (a) Si-face attack of (S,S)-C4 active form on (S)-2a, (b) Si-face attack on (R)-2a, (c) Re-face attack on (S)-2a, and (d) Re-face attack on (R)-2a. The enantioselectivity determining attractive and repulsive interactions are highlighted by green and red symbols, respectively. Nonessential H atoms are omitted for clarity. Calculated yields are estimated from the relative Gibbs free energies of the TS at 298.15 K and 1 atm.

The stabilization of the particular TS leading to formation of the major stereoisomer (1R,2S)-3a, is brought about by an attractive hydrogen bonding (1.92 Å) interaction between the catalyst’s SO2 region and ketone’s α-substituent (O=S=O···H–O–CH), and CH/π interaction between the aromatic rings of the catalyst η6-arene ligand and substrate (Figure 3a). When (R)-2a is attacked from the Si-face (Figure 3b), the hydrogen bond was confirmed as well (1.75 Å), but the CH/π interaction appears to be weaker due to orientation of the aromatic rings. During the Re-face attack of the catalyst (S,S)-C4 to either enantiomer of 2a (Figure 3c and 3d), no hydrogen bond can form, and there is even an SO/π repulsive interaction, making both products disfavored. Rather unexpectedly, the CF3 group does not stabilize the Re-face attack via an attractive interaction with η6-arene. Note that ketones with electron-donating α-substituents studied herein engage in hydrogen bonding with the catalyst via heteroatom-bound β-hydrogen of the ketone, whereas the ketones with electron-withdrawing α-substituents were shown computationally to form an attractive interaction with the SO2 group of the Noyori–Ikariya-type ruthenium21 and the related rhodium43,44 catalysts via the acidic ketone’s α-hydrogen.

With the optimal conditions in hand, we explored the substrate scope.45 Because the double reduction of 1a to 3a involved DKR of the intermediate racemic 2a, diketones, as well as acyloins, would be appropriate starting materials. The required CF3-substituted 1,2-diketones 1b, 1e, 1f, 1h–1l, and 1n were prepared from the corresponding (het)aryl aldehydes, similarly to 1a.41 The racemic monoalcohols 2c, 2d, 2g, 2m, and 2o–2q were prepared via acylation-rearrangement of the corresponding α-hydroxy- or α-amino acids with trifluoroacetic anhydride,46 and 2r was prepared via N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed crossed acyloin condensation.47 The two best performing catalysts, C4 and C5 were used for DKR-ATH of the substrates. For comprehensive results, see Table S3 in the SI, and Table 2 contains the optimal conditions for each substrate in terms of diastereo- and enantioselectivity. The reaction gives good stereoselectivities for the reduction of aryl ketones with electron acceptor or donor substituents. For the latter, higher catalyst loading was required to achieve full conversion. During the reduction of the formyl-substituted 1l, the aldehyde group was reduced as well, and the corresponding triol 3l was isolated. Heterocyclic examples 2m and 1n were reduced to the corresponding syn-diols with excellent stereoselectivity. DKR-ATH of the α,β-unsaturated ketone 2r under our standard reaction conditions afforded the major product 3r with a preserved double bond, along with 16% of the saturated side products. The absolute configuration of the (het)aryl-substituted diols 3a–3n was assigned on the basis of the single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of 3e. Remarkably, the dialkylketones 2o–2q were reduced to the corresponding syn-diols with >95% ee using C4 or C5; the first one was more diastereoselective for the synthesis of the benzyl substituted 3o, and C5 was optimal for the synthesis of 3p and 3q. In the case of dialkylketone reduction, the stereoselectivity could (in the absence of appropriately positioned aromatic ring on the substrate) rely either on hydrogen bonding of CF3CH(OH) moiety to SO2 of the catalyst or on CF3–η6-arene attractive interaction.13,48 The two hydrogenation modes would deliver the opposite enantioselectivity, which is often the case for the Noyori–Ikariya reduction of dialkyl vs alkyl aryl ketones.49−51 Based on the SCXRD analysis of 3o, the order of elution in chiral chromatographic analysis, and computational analysis of the transition states during the reduction of the model substrate, where no CF3–η6-arene attractive interaction has been identified during Re-face attack (Figure 3c and 3d), we assigned to the alkyl-substituted diols 3o, 3p, and 3q the same absolute configuration as to the (het)aryl-substituted 3a–3n.

Table 2. Scope of the CF3-Subsituted 1,2-Diols syn-3 Available via Ru(II)-Catalyzed DKR-ATHa.

The reactions were carried out using 1 or 2 (0.5 mmol) and (S,S)-diphenylethylenediamine-based ruthenium catalyst in HCO2H/Et3N 3:2 (0.5 mL) and DMF (1 mL) at 60 °C.

Isolated yield of stereopure syn-3e on a gram-scale.

88% conversion.

16% of double bond reduction products.

Racemic diols 3 to be used as standards for the determination of stereoisomeric ratios were prepared by NaBH4 reduction in ethanol. It is noteworthy that using this approach, the alternative diastereomers anti-3 were the major products (anti/syn ratios between 65:35 and 97:3); for details, see Table S3.

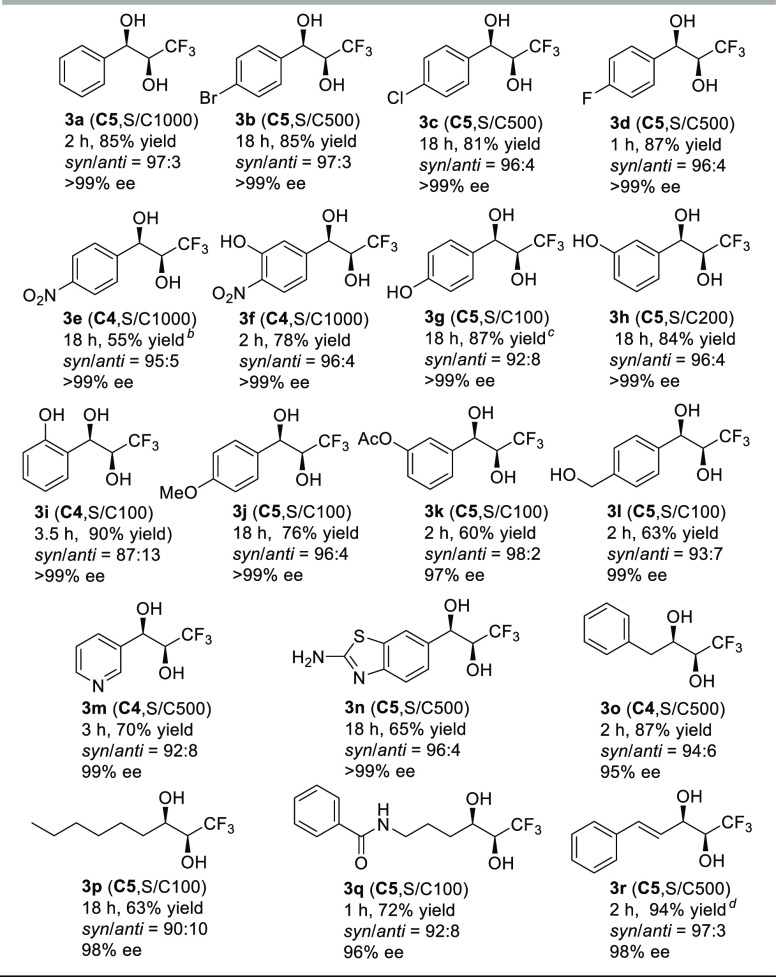

To demonstrate synthetic usefulness of the developed method, the p-nitro derivative 1e was reduced on a gram scale using a S/C = 1000. The diol 3e was acetonide-protected, and then the nitro group was reduced to the corresponding amine building block 4 using iron in acetic acid. After straightforward coupling to 5-chloroindole-2-carboxylic acid and deprotection, compound 5 was prepared. Compound 5 is a glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor, previously reported as racemic syn diastereomer (Scheme 1a).33 Furthermore, as a support to the hit-to-lead optimization campaign of our in-house antibacterial topoisomerase inhibitor ULD1,52,53 its analogues with carboxylic acid-to-CF3-diol replacement were prepared.35 The stereochemical array of compounds 6 was accessed from the diketone 1n by employing respective enantiomers of C5 to access homochiral syn-6, or NaBH4 reduction to target the racemic anti-6 (Scheme 1b).

Scheme 1. Further Synthetic Transformations of Stereopure DKR-ATH Products 3.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed syn-selective reductive access to homochiral CF3-substituted-1,2-diols by employing dynamic kinetic resolution during the Noyori–Ikariya asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of the corresponding α-hydroxyketones. The origin of stereoselectivity was investigated by using DFT calculations and was attributed to the hydrogen bonding between the ketone’s H-bond donor α-substituent and the catalyst’s SO2 moiety. High stereoselectivity (syn/anti ≥87:13, ≥95% ee) was achieved for the reduction of (het)aryl, vinyl, benzyl, and alkyl ketones. Furthermore, elaboration of the stereopure diols to molecules relevant for medicinal chemistry was demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency ARRS core funding P1-0208, P2-0421, P1-0045 infrastructure funding I0-0039 and project funding Z1-2635, N1-0303. M.L. gratefully acknowledges the funding by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (950625). The authors gratefully acknowledge the HPC RIVR consortium and EuroHPC JU for funding this research by providing computing resources of the HPC system Vega at the Institute of Information Science, Maribor, Slovenia. Maja Frelih and Prof. Stane Pajk are acknowledged for acquisition of HRMS spectra. We are grateful to Prof. Martin Wills from the University of Warwick for a gift of catalyst C6.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c00980.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pellissier H.Chirality from Dynamic Kinetic Resolution; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011; pp XV–XVIII. [Google Scholar]

- Noyori R.; Ikeda T.; Ohkuma T.; Widhalm M.; Kitamura M.; Takaya H.; Akutagawa S.; Sayo N.; Saito T.; Taketomi T.; Kumobayashi H. Stereoselective Hydrogenation via Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111 (25), 9134–9135. 10.1021/ja00207a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi S.; Fujii A.; Takehara J.; Ikariya T.; Noyori R. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Aromatic Ketones Catalyzed by Chiral Ruthenium(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117 (28), 7562–7563. 10.1021/ja00133a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. M.; Morris D. J.; Clarkson G. J.; Wills M. A Class of Ruthenium(II) Catalyst for Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenations of Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127 (20), 7318–7319. 10.1021/ja051486s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touge T.; Hakamata T.; Nara H.; Kobayashi T.; Sayo N.; Saito T.; Kayaki Y.; Ikariya T. Oxo-Tethered Ruthenium(II) Complex as a Bifunctional Catalyst for Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation and H2 Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (38), 14960–14963. 10.1021/ja207283t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni R.; Jolley K. E.; Clarkson G. J.; Wills M. Direct Formation of Tethered Ru(II) Catalysts Using Arene Exchange. Org. Lett. 2013, 15 (19), 5110–5113. 10.1021/ol4024979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kišić A.; Stephan M.; Mohar B. Ansa-Ruthenium(II) Complexes of R2NSO2DPEN-(CH2)n(η6-Aryl) Conjugate Ligands for Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357 (11), 2540–2546. 10.1002/adsc.201500288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E.; Lozinšek M.; Wang B.; Stephan M.; Mohar B. trans-Diastereoselective Ru(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of α-Acetamido Benzocyclic Ketones via Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (10), 3644–3648. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E. Escaping from Flatland: Stereoconvergent Synthesis of Three-Dimensional Scaffolds via Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Noyori–Ikariya Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27 (1), 39–53. 10.1002/chem.202002779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker P. D.; Hou X.; Dong V. M. Reducing Challenges in Organic Synthesis with Stereoselective Hydrogenation and Tandem Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (18), 6724–6745. 10.1021/jacs.1c00750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt R. M.; Echeverria P.-G.; Ayad T.; Phansavath P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V. Recent Progress and Applications of Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation and Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones and Imines through Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Synthesis 2021, 53 (1), 30–50. 10.1055/s-0040-1705918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa M.; Yamada I.; Noyori R. CH/π Attraction: The Origin of Enantioselectivity in Transfer Hydrogenation of Aromatic Carbonyl Compounds Catalyzed by Chiral η6-Arene-Ruthenium(II) Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40 (15), 2818–2821. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E.; Cahard D.; Mohar B. Stereoarrayed CF3-Substituted 1,3-Diols by Dynamic Kinetic Resolution: Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (17), 5294–5298. 10.1002/anie.201600812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E.; Modec B.; Mohar B. Stereoarrayed 2,3-Disubstituted 1-Indanols via Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Resolution–Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2018, 20 (10), 2921–2924. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q.-X.; Liu L.-X.; Zhu Z.-H.; Yu C.-B.; Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of 2,3-Disubstituted Flavanones through Dynamic Kinetic Resolution Enabled by Retro-Oxa-Michael Addition: Construction of Three Contiguous Stereogenic Centers. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87 (11), 7521–7530. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c00418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touge T.; Sakaguchi K.; Tamaki N.; Nara H.; Yokozawa T.; Matsumura K.; Kayaki Y. Multiple Absolute Stereocontrol in Cascade Lactone Formation via Dynamic Kinetic Resolution Driven by the Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Keto Acids with Oxo-Tethered Ruthenium Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (41), 16354–16361. 10.1021/jacs.9b07297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt R. M.; Phansavath P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V. Ru(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of 3-Fluorochromanone Derivatives to Access Enantioenriched cis-3-Fluorochroman-4-ols through Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86 (17), 12054–12063. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.; Sun G.; Wu S.; Chen Y.; Lin Y.; Zhang L.; Wang Z. η6-Arene CH–O Interaction Directed Dynamic Kinetic Resolution – Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation (DKR-ATH) of α-Keto/Enol-Lactams. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363 (12), 3030–3034. 10.1002/adsc.202100288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touge T.; Nara H.; Kida M.; Matsumura K.; Kayaki Y. Convincing Catalytic Performance of Oxo-Tethered Ruthenium Complexes for Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Cyclic α-Halogenated Ketones through Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Org. Lett. 2021, 23 (8), 3070–3075. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z.-Q.; Li X.; Liu L.-X.; Yu C.-B.; Zhou Y.-G. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of β-Substituted α-Oxobutyrolactones. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86 (23), 17453–17461. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E.; Dub P. A.; Sterle M.; Lozinšek M.; Dernovšek J.; Zajec Ž.; Zega A.; Tomašič T.; Cahard D. Catalytic Stereoconvergent Synthesis of Homochiral β-CF3, β-SCF3, and β-OCF3 Benzylic Alcohols. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2022, 2 (5), 396–404. 10.1021/acsorginorgau.2c00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley E. R.; Sherer E. C.; Pio B.; Orr R. K.; Ruck R. T. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Resolution Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of β-Chromanones by an Elimination-Induced Racemization Mechanism. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (2), 1446–1451. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dub P. A.; Tkachenko N. V.; Vyas V. K.; Wills M.; Smith J. S.; Tretiak S. Enantioselectivity in the Noyori–Ikariya Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones. Organometallics 2021, 40 (9), 1402–1410. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dub P. A.; Ikariya T. Quantum Chemical Calculations with the Inclusion of Nonspecific and Specific Solvation: Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation with Bifunctional Ruthenium Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (7), 2604–2619. 10.1021/ja3097674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rast S.; Modec B.; Stephan M.; Mohar B. γ-Sultam-Cored N,N-Ligands in the Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Aryl Ketones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14 (6), 2112–2120. 10.1039/C5OB02352A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J. Y. L.; Scott J. P.; Anderson C.; Bishop B.; Bremeyer N.; Cao Y.; Chen Q.; Dunn R.; Kassim A.; Lieberman D.; Moment A. J.; Sheen F.; Zacuto M. Evolution of a Manufacturing Route to Omarigliptin, A Long-Acting DPP-4 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19 (11), 1760–1768. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gediya S. K.; Clarkson G. J.; Wills M. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation: Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of α-Amino Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85 (17), 11309–11330. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeran M.; Cotman A. E.; Stephan M.; Mohar B. Stereopure Functionalized Benzosultams via Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Resolution–Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (8), 2042–2045. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Li X.; Caricato M.; Marenich A. V.; Bloino J.; Janesko B. G.; Gomperts R.; Mennucci B.; Hratchian H. P.; Ortiz J. V.; Izmaylov A. F.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Williams-Young D.; Ding F.; Lipparini F.; Egidi F.; Goings J.; Peng B.; Petrone A.; Henderson T.; Ranasinghe D.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Gao J.; Rega N.; Zheng G.; Liang W.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Throssell K.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M. J.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E. N.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T. A.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A. P.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Adamo C.; Cammi R.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016.

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120 (1), 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson G. A.; Bennett A.; Tensfeldt T. G.; Al-Laham M. A.; Shirley W. A.; Mantzaris J. A Complete Basis Set Model Chemistry. I. The Total Energies of Closed-shell Atoms and Hydrides of the First-row Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89 (4), 2193–2218. 10.1063/1.455064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson G. A.; Al-Laham M. A. A Complete Basis Set Model Chemistry. II. Open-shell Systems and the Total Energies of the First-row Atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 94 (9), 6081–6090. 10.1063/1.460447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onda K.; Suzuki T.; Shiraki R.; Yonetoku Y.; Ogiyama T.; Maruyama T.; Momose K.. Derives d’amide ou sels de ces derives. WO2003091213A1, November 6, 2003. https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2003091213A1/en?oq=WO2003091213 (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

- Hirano M.; Kawaminami E.; Kinoyama I.; Matsumoto S.; Ohnuki K.; Obitsu K.; Kusayama T.. Benzimidazolylidene Propane-1,3-Dione Derivative or Salt Thereof. US8076367B2, December 13, 2011. https://patents.google.com/patent/US8076367B2/en?oq=WO2005118556 (accessed Oct. 13, 2022).

- Palmer J. T.; Axford L. C.; Barker S.; Bennett J. M.; Blair M.; Collins I.; Davies D. T.; Ford L.; Gannon C. T.; Lancett P.; Logan A.; Lunniss C. J.; Morton C. J.; Offermann D. A.; Pitt G. R. W.; Rao B. N.; Singh A. K.; Shukla T.; Srivastava A.; Stokes N. R.; Thomaides-Brears H. B.; Yadav A.; Haydon D. J. Discovery and in Vivo Evaluation of Alcohol-Containing Benzothiazoles as Potent Dual-Targeting Bacterial DNA Supercoiling Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24 (17), 4215–4222. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister L. A.; Butler C. R.; Mente S.; O’Neil S. V.; Fonseca K. R.; Piro J. R.; Cianfrogna J. A.; Foley T. L.; Gilbert A. M.; Harris A. R.; Helal C. J.; Johnson D. S.; Montgomery J. I.; Nason D. M.; Noell S.; Pandit J.; Rogers B. N.; Samad T. A.; Shaffer C. L.; da Silva R. G.; Uccello D. P.; Webb D.; Brodney M. A. Discovery of Trifluoromethyl Glycol Carbamates as Potent and Selective Covalent Monoacylglycerol Lipase (MAGL) Inhibitors for Treatment of Neuroinflammation. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (7), 3008–3026. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.-S.; Delcourt M.-L.; Pannecoucke X.; Charette A. B.; Poisson T.; Jubault P. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of α,α-Difluoromethylated and α-Fluoromethylated Tertiary Alcohols. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (18), 7509–7513. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong M.-Y.; Yang L.; Nie J.; Zhang F.-G.; Ma J.-A. Construction of Chiral β-Trifluoromethyl Alcohols Enabled by Catalytic Enantioselective Aldol-Type Reaction of CF3CHN2. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (11), 4280–4283. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki K.; Gotoh T.; Kani R.; Inuzuka T.; Kubota Y. Highly Diastereo- and Enantioselective Organocatalytic Synthesis of Trifluoromethylated Erythritols Based on the in Situ Generation of Unstable Trifluoroacetaldehyde. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19 (6), 1296–1304. 10.1039/D0OB02067B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran P. V.; Padiya K. J.; Reddy M. V. R.; Brown H. C. An Efficient Enantioselective Total Synthesis of a Trifluoromethyl Analog of Blastmycinolactol. J. Fluorine Chem. 2004, 125 (4), 579–583. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2004.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitori Y.; Hojo M.; Masuda R.; Fujitani T.; Ohara S.; Yokoyama T. Electrophilic Substitution at Azomethine Carbon Atoms. Reaction of Aromatic Aldehyde Hydrazones with Trifluoroacetic Anhydride. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53 (1), 129–135. 10.1021/jo00236a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K.; Okano K.; Miyagi M.; Iwane H.; Noyori R.; Ikariya T. A Practical Stereoselective Synthesis of Chiral Hydrobenzoins via Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Benzils. Org. Lett. 1999, 1 (7), 1119–1121. 10.1021/ol990226a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Yang T.; Wu T.; Zheng L.-S.; Yin C.; Shi Y.; Ye X.-Y.; Chen G.-Q.; Zhang X. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of α-Substituted-β-Keto Carbonitriles via Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (6), 2477–2483. 10.1021/jacs.0c13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Zhang Z.; Chen Y.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V.; Yu P.; Chen G.-Q.; Zhang X. Stereodivergent Synthesis of Chiral Succinimides via Rh-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 7794. 10.1038/s41467-022-35124-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski M. C. On the Topic of Substrate Scope. Org. Lett. 2022, 24 (40), 7247–7249. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase M.; Saito S.; Kurihara T. Convenient Synthesis of α-Trifluoromethylated Acyloins from α-Hydroxy or α-Amino Acids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48 (9), 1338–1343. 10.1248/cpb.48.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanjaneyulu B. T.; Mahesh S.; Vijaya Anand R. N -Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyzed Highly Chemoselective Intermolecular Crossed Acyloin Condensation of Aromatic Aldehydes with Trifluoroacetaldehyde Ethyl Hemiacetal. Org. Lett. 2015, 17 (1), 6–9. 10.1021/ol502581b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šterk D.; Stephan M.; Mohar B. Highly Enantioselective Transfer Hydrogenation of Fluoroalkyl Ketones. Org. Lett. 2006, 8 (26), 5935–5938. 10.1021/ol062358r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Bagdi P. R.; Yang S.; Liu J.; Cotman A. E.; Xu W.; Fang X. Correction to Stereodivergent Access to Enantioenriched Epoxy Alcohols with Three Stereogenic Centers via Ruthenium-Catalyzed Transfer Hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2020, 22 (11), 4582–4582. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Liu W.; Gu W.; Niu S.; Lan S.; Zhao Z.; Gong F.; Liu J.; Yang S.; Cotman A. E.; Song J.; Fang X. Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of β-Substituted α-Diketones via Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (1), 585–599. 10.1021/jacs.2c11149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šterman A.; Sosič I.; Časar Z. Primary Trifluoroborate-Iminiums Enable Facile Access to Chiral α-Aminoboronic Acids via Ru-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation and Simple Hydrolysis of the Trifluoroborate Moiety. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13 (10), 2946–2953. 10.1039/D1SC07065G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyerges A.; Tomašič T.; Durcik M.; Revesz T.; Szili P.; Draskovits G.; Bogar F.; Skok Ž.; Zidar N.; Ilaš J.; Zega A.; Kikelj D.; Daruka L.; Kintses B.; Vasarhelyi B.; Foldesi I.; Kata D.; Welin M.; Kimbung R.; Focht D.; Mašič L. P.; Pal C. Rational Design of Balanced Dual-Targeting Antibiotics with Limited Resistance. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18 (10), e3000819. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman A. E.; Durcik M.; Benedetto Tiz D.; Fulgheri F.; Secci D.; Sterle M.; Možina Š.; Skok Ž.; Zidar N.; Zega A.; Ilaš J.; Peterlin Mašič L.; Tomašič T.; Hughes D.; Huseby D. L.; Cao S.; Garoff L.; Berruga Fernández T.; Giachou P.; Crone L.; Simoff I.; Svensson R.; Birnir B.; Korol S. V.; Jin Z.; Vicente F.; Ramos M. C.; de la Cruz M.; Glinghammar B.; Lenhammar L.; Henderson S. R.; Mundy J. E. A.; Maxwell A.; Stevenson C. E. M.; Lawson D. M.; Janssen G. V.; Sterk G. J.; Kikelj D. Discovery and Hit-to-Lead Optimization of Benzothiazole Scaffold-Based DNA Gyrase Inhibitors with Potent Activity against Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66 (2), 1380–1425. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.