Abstract

A wide portfolio of advanced programmable materials and structures has been developed for biological applications in the last two decades. Particularly, due to their unique properties, semiconducting materials have been utilized in areas of biocomputing, implantable electronics, and healthcare. As a new concept of such programmable material design, biointerfaces based on inorganic semiconducting materials as substrates introduce unconventional paths for bioinformatics and biosensing. In particular, understanding how the properties of a substrate can alter microbial biofilm behavior enables researchers to better characterize and thus create programmable biointerfaces with necessary characteristics on demand. Herein, the current status of advanced microorganism–inorganic biointerfaces is summarized along with types of responses that can be observed in such hybrid systems. This work identifies promising inorganic material types along with target microorganisms that will be critical for future research on programmable biointerfacial structures.

Keywords: advanced programmable materials, biointerfaces, microorganisms, semiconductors

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, novel approaches and new types of inorganic and organic polymers, various composites, micro- and nanomaterials, and their implementations have become a prolific and broad research direction for the field of materials engineering. Importantly, smart materials with programmable characteristics and abilities to change their parameters upon certain conditions have received a lot of attention by scientists with different interests and research backgrounds.[1–4] Furthermore, unique properties and opportunities associated with nanoscale size of materials open paths for multiple applications in electronics, aerospace and automotive fields, as well as in chemical and bio engineering, healthcare and food processing.[5–8] In particular, the last three areas have benefited tremendously from novel approaches, since new nanomaterials have enabled scientists to develop various biosensing complexes,[9,10] drug delivery systems,[11–13] implants with improved capabilities and performance,[14,15] effective antibacterial coatings,[16,17] and additional advanced inventions taking over consumer products by making them simpler, safer, and more comfortable.

Advanced materials with programmable characteristics for bioapplications have to possess stable structure and need to be biocompatible.[18,19] Thus, interactions between inorganic materials and living organisms play a key role in the research related to programmable materials in bioengineering and healthcare. The development of the aforementioned tools and systems (i.e., implants, biosensors, antibacterial coatings), depends on a clear understanding of how the properties of a particular material and its derivatives affect its interactions with cells, bacteria, or fungi.[20b] Such bioorganic interfacial structures are extensively researched by scientists working in the area of electrobiotics.[21–23] For example, Sakimoto et al.[23] enables a self-photosensitization of a nonphotosynthetic bacterium, Moorella thermoacetica, by interfacing it with cadmium sulfide nanoparticles thus enabling the photosynthesis of acetic acid from carbon dioxide. Furthermore, in Figure 1 Patolsky et al.[22] demonstrates how an inorganic substrate that reacts to the presence of viruses can change its electrostatic properties enabling its utilization as a single-cell detector. Additionally, by characterizing parameters such as cell survivability, cell attachment and cell growth rate, it has been possible to quantify the biocompatibility of specific materials of interest. There is an impressive amount of literature on the interactions of a variety of cell types and microorganisms with biocompatible polymers and composites,[24,25] nanocolloids, and nanoparticles.[11,26–31] For instance, ZnO has been used for drug delivery[32,33] and as a biocide.[34,35] Ag nanoparticles are an effective bactericide.[36,37] TiO2 has also shown promise for various bioapplications[14,26] and as a material that suppresses the growth of unwanted microbial biofilms.[17,38] These well-studied examples of materials and applications provide great opportunities for their adaptation in novel applications that require predictable outcomes and programmable characteristics.

Figure 1.

Nanowire-based detection of single viruses. The schematic shows two nanowire devices, where the nanowires are modified with different antibody receptors and produce reactions to the presence of viruses accordingly. Reproduced with permission.[22] Copyright 2004, National Academy of Sciences.

While formulating programmable biointerfacial structures researchers need to understand the interactions of living species with 2D/planar/interfacial abiotic materials, whether they possess nanostructured features or not. However, in a number of cases, the inorganic material does not need to be in a colloidal formulation. Planar/2D materials, nanotextured, or patterned (but not nanosized) serve as a substrate for the colonization of a microorganism and the subsequent formation of a biofilm. These planar/2D materials do not penetrate the cell, and many cellular responses can be linked to the properties of the created biointerface. In these cases the biointerface is defined as an advanced closed system or a region of contact between a living cell and a substrate, which can be either organic or inorganic.[39] The biointerfacial properties of the substrate, biolayer, and external stimuli coexist, and are interdependent.[40] Therefore, it is critical not only to characterize the individual components of this biointerface, but also how its components program and develop potentially new and unexpected emergent properties from their interactions.

Different applications require certain materials with specific characteristics. Inorganic biofunctional material systems whether they are insulators, metals and semiconductors need to be nontoxic, biotissue-compatible, and often biodegradable as well.[41] For example, Ti-alloy implants have been tailored for good tissue attachment and high antibacterial capabilities,[42] whereas bacterial biofilm biosensors should not suppress bacterial cell growth and be highly sensitive to any changes in the surrounding environment.[43,44] Furthermore, doping of semiconducting substrates with noble metals provides high conductivity, which is crucial in bioelectronics, however some noble metals have considerable biological effects, such as Ag, while others like Au are neutral. Therefore, even minor components of a biointerface need to be considered as sub-biointerfaces because they are broadly used in biosensors and bioimplants.[41,45–47] With these caveats in mind, any work on developing advanced materials for biosensors and bioimplantable electronic devices needs to quantify and tailor the properties of these “living organism–inorganic semiconducting substrate” programmable systems.

The scope here is to highlight the common trends in programmable or “smart” biomaterials development and cover current progress in the research of planar/2D inorganic biointerfaces: materials and their interactions with microorganisms. Additionally, the discussion on the future directions of this field helps to better oversee the role of biointerfaces as adaptable materials or structures that can be employed in a range of different environments. We will also summarize possible ways of advancing the understanding of processes occurring in these multicomponent systems and identify the most promising candidates for future research in the field of bioelectronics. In this review paper, we emphasize the recognition of the major challenges associated with determining and defining physiological and genetic responses in biofilms to abiotic interfacial materials. We have identified the organic and inorganic programmable materials that are developed for practical and potential bioapplications to better understand the tendencies in this research field; the inorganic materials that are currently utilized as substrates for biointerfaces with microbes; the species of microbe that are targeted and may be utilized as a part of a programmable biointerfacial structure. Table 1 summarizes our representative findings on advanced programmable materials that typically change their properties or express reactions under certain conditions, usage, or stimuli. Table 2 compiles the planar semiconductor substrates in/for biosystems, the types of microorganisms that have been used to study biological responses to these substrates and their applications. Table 3 classifies the types of physiological responses that may be observed in certain microorganisms due to substrate characteristics and (or) external stimuli applied. Table 4 summarizes the genetic responses of microorganisms to inorganic materials. The tables also include references that comment on response mechanisms associated with specific target organisms. The goal of this organization is to define the cellular mechanisms and processes involved at a functional biointerfaces, correlate surface properties with these cellular behaviors, and perhaps be able to use the correlation to predict the behavior and responses that are associated with specific materials to develop new “smart” interfacial biosystems with programmable characteristics.

Table 1.

Representative examples of smart materials and their potential application areas.

| Type of materiala,b) | Material featuresb) | Stimulib) | Projected applicationsb) | Ref. #b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au nanorods | DOX toxicity, fluorescence | Photothermal excitation | Bioimaging, drug delivery | [65] |

| (Dextran, DMAEMA*, Si†) MPs | Selective release of agents | Glucose, ROS (O2−, H2O2), pH change*, PBS† | Drug delivery | [49,50*,51†] |

| (BN*, WS2†) QDs | Photoluminescence | Visible, UV light | Bioimaging | [52*,53†] |

| MoS2 + WS2 QDs | Catalytic abilities, fluorescence | H2SO4 | Bioimaging | [54] |

| Au electrodes + NPs | Biomolecule release | Electric current, water | Drug delivery | [48] |

| Polymer (PDMS*, polyolefin†) | Flexibility (folding, contraction) | Magnetic field, visible light | Soft robotics, fluid transport† | [55*,56†] |

| (α*, β†)-keratin biopolymer | Shape memory effect | Water | Shape memory materials | [57*,58†] |

| TixTa1−xSyOz nanosheets | Photothermal properties | NIR irradiation | Drug delivery, bioimaging | [82] |

| Polymer (PCL/HDI/BD)*, polymer + (C†, Ga‡, Pt†) nanofiber | Shape memory effect | Temperature change*,‡,†, electric current† | Sensors, actuators, bioelectronics, soft robotics‡ | [66†,69*,70†,71 ‡,72†] |

| Copolymer-based hydrogels | Swelling | Temperature change | Drug-delivery, bioimaging* | [59*,60] |

| PEG-based hydrogels, chondroitin sulfate hydrogel* | Disintegration/self-healing | Ultrasound, Water*,† | Biomaterials, drug delivery | [61,62*,64] |

| Salt-PEG hydrogels | Electrical activity (conductivity) | Mechanical stress | Soft robotics, bioelectronics | [80] |

| Chitosan/copolymer hydrogel | Self-folding | Water | Drug delivery | [63] |

| Polymer + silica/Fe3O4 NPs composite | Shape memory effect | Magnetic field, temperature change | Soft robotics, bioelectronics | [73] |

| (MoS2*, MoS2/CN†) composite | Catalytic abilities | Visible light, H2SO4 | Renewable energy storage | [74†,75*,76*] |

| TiO2/WS2 composite | Photocatalytic abilities | Visible light | Catalysis systems | [81] |

| Resin-Fe composite | Flexibility (curving, bending) | Magnetic field | Soft robotics, drug delivery | [67] |

| PGMA/Au composite | 2D folds into 3D | Solvent (CH4O), salts | Soft robotics, sensors | [78] |

| PCBs/Rh composite | Shape memory effect | Ultrasound cavitation (in liquid) | Sensing/switching systems | [68] |

| pNIPAM/CN composite | Self-folding, tunable response | NIR irradiation, temperature change | Bioelectronics, tissue engineering | [83] |

| Polymer (PMDS) + bio. cells hybrid | Bending, change of curvature | Electric current | Soft robotic systems | [79] |

| DNA-based hydrogels | Shape-memory effect*, swelling | pH change*, enzymes† | Drug delivery | [77*,88†] |

NPs, nanoparticles; MPs, microparticles; QDs, quantum dots;

Reference sources marked with *, †,‡, and † primarily utilize materials, stimuli and/or have potential applications marked with these special characters.

Table 2.

Semiconducting materials used for bioapplications.

| Material | Surface type | Target microorganisma) | Stimulia) | Targeted response | Ref. #a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | Thin film | E. coli | UV light | Antibacterial, properties characterization | [98,124] |

| ZnO | Thin film | S. aureus | UV light | Antibacterial | [125] |

| ZnO | Thin film | E. coli, S. aureus, S. putrefaciens * | No | Antibacterial | [99,126,133*] |

| ZnO | Thin film (functionalized) | E. coli, S. aureus, P. vulgaris, K. pneumoniae | No | Antibacterial | [101] |

| ZnO | Thin film | B. subtilis, A. niger | UV light | Antibacterial, properties characterization | [95] |

| ZnO | Thin film (doped) | S. aureus, P. vulgaris, S. haemolyticus | No | Antibacterial | [127] |

| ZnO | Patterned nanorods | E. coli | UV light | Antibacterial | [139,140] |

| ZnO | Patterned nanocomposite (doped) | E. coli, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, P. vulgaris | visible light | Antibacterial | [134] |

| TiO2 | Thin film | E. coli | UV, visible light* | Antibacterial | [100,103,128–(130,131)*] |

| TiO2 | Thin film (functionalized) | E. coli | UV, no* | Antibacterial | [102,141,(142,143)*] |

| TiO2 | Thin film (functionalized) | M. lylae | UV light | Antibacterial | [144] |

| TiO2 | Nanomembrane (functionalized) | E. coli, P. aeruginosa * | No | Biosensing | [135*,136] |

| TiO2 | Thin film | P. aeruginosa, S. mutans * | UV light | Antibacterial | [103,104,132*] |

| TiO2 | Nanopowder coating | E. coli*, B. megaterium | UV light | Antibacterial | [137,138*] |

| TiO2 | Thin film (functionalized) | S. aureus | No, UV* | Antifouling | [146*,152] |

| GaN | Thin film (functionalized) | D. radiodurans | No | Biosensing | [163] |

| GaN | Thin film (functionalized) | E. coli | No | Biosensing, selective functionalization | [96] |

| GaN | Thin film (functionalized) | S. cerevisiae | No | Biocompatibility | [94] |

| GaN | Thin film | P. aeruginosa, E. coli * | UV light | Biocompatibility | [92,93*,123] |

| AlGaN, GaN | Thin film (functionalized) | S. avidinii | No | Biosensing | [147] |

| Ti–6Al–4V | Alloy | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | UV light | Adhesion profile, cell behavior | [109,110] |

| Ti/Ti–Ag/Ti–Ga | Alloy | A. baumannii | No | Antibacterial | [117] |

| PdO/TiON | Composite fiber | E. coli | Visible light | Antifouling, antibacterial | [149] |

| Zn/TiO2 | Composite | E. coli, S. aurelis | No | Antibacterial | [153] |

| Si | Wafer | E. coli, S. aureus*, B. subtilis† | No | Adhesion profile | [111*,150,151†] |

Reference sources marked with *, † utilize primarily (only) target microorganisms and/or stimuli marked with these special characters.

Table 3.

Classification of physiological responses expressed in biointerfacial structures.

| Study type | Target microorganisma) | Substrate materiala) | Surface treatmenta) | Response observed | Ref. #a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion | E. coli†, S. aureus, S. epidermidis | Polymers (LDPE, AC), silicone* | Opsonization, antibiotic* | Cell attachment profile | [165†,173*] |

| Adhesion | E. coli*, S. aureus†, P. aeruginosa‡ | Si*,†, TiO2‡ | – | Growth, attachment profile | [111†,(150,166)*,184‡] |

| Adhesion | E. coli, C. reinhardtii | TO | UV, high temperature | Antifouling, attachment profile | [102] |

| Adhesion | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | Alloy (Ti6Al4V) | UV | Cell attachment profile | [109,110] |

| Adhesion | S. thermophilus, S. waiu | Metals (steel, Al, Zn, Cu) | – | Growth, attachment profile | [119] |

| Adhesion | P. aeruginosa | Polymer (PVC) | Surface plasma | Cell attachment profile | [183] |

| Adhesion | S. aureus, E. coli * | TiO2, silicone* | Monomolecular coatings | Antifouling profile | [145,152,(174,175)*] |

| Adhesion | P. fluorescens | Ni–P–TiO2–PTFE | – | Antifouling, antibacterial | [185] |

| Proliferation | E. coli | Polymers (PU, PDMS*, polylysine†) | – | Antibacterial, antifouling | [113†,114,(116,169)*,170†] |

| Proliferation | E. coli | ZnO, ZnO + Ag, steel* | – | Growth profile, antibacterial | [124,171*] |

| Proliferation | E. coli, S. aureus, P. mirabilis | Polymers (pSBMA, PS*) | – | Antibacterial, antifouling | [172] |

| Proliferation | S. aureus, S. epidermidis*,†, E. colix | VO2/W, CS + Ga*, TiO2 + Zn† | – | Antibacterial | [153†,x,176*,†,178] |

| Proliferation | S. aureus*, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa | Polymers (PEO, PPO, PEG-b-PC*) | – | Antibacterial, antifouling | [179,180*] |

| Proliferation | S. aureus, S. mutans * | TiO2 | Low temperature, UV* | Antibacterial, growth profile | [132*,146,184] |

| Proliferation | A. baumannii, S. aureus * | Ti, Ti + Ag, Ti + Ga | – | Antibacterial properties | [117,181*] |

| Morphology | E. coli, B. subtilis * | PDMS, polymer SAMS†, Si* | – | Growth, morphology profile | [151*,167,168†] |

| Morphology | S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa * | TiO2 | UV | Antibacterial properties | [103,104*] |

| Morphology | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | CS + Ga | – | Biofilm degradation profile | [176] |

| Morphology | P. aeruginosa | Steel, Al, rubber | – | Antifouling, altered structure | [118] |

| Morphology | S. putrefaciens | ZnO | – | Morphology, attachment prof. | [133] |

| Secretion | E. coli, S. aureus, B. anthracis, P. aeruginosa | Pb(Ac)2-soaked paper strip | Metal salts, antibiotic | H2S concentration alterations | [182] |

| Secretion | P. fluorescens | Steel | Surfactants | Biofilm growth and secretion | [186] |

| Secretion | S. putrefaciens | Fe(III) | – | Fe-based Ss operation change | [112] |

| Secretion | P. aeruginosa | Polymers (PTFE) | –* | Virulence, signaling operation | [115*] |

References marked with *, †, ‡ utilize primarily (only) target microorganisms/substrate materials/surface treatments marked with these special characters. References noted as †, x have all listed and include target microorganisms/substrate materials/surface treatments marked accordingly.

Table 4.

Genetic response studies performed on microorganisms.

| Study focusa) | Type of stress | Target microorganisma) | Stress agenta) | Response type | Ref. #a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | Environmental | E. coli | Temperature fluctuations, pH* | Secretion profile/viability | [189,214,215,216*] |

| Stress | Environmental | E. coli | Aerobic/anaerobic | Gene activity profile | [217] |

| Stress | Environmental | B. subtilis, S. aureus, S. pneumonia | Biofilm density | Gene activity profile | [213] |

| Stress | Environmental | H. pylori | Aerobic/anaerobic, starvation | Lipid concentration, morphology profile | [229] |

| Stress | Oxidative | E. coli | O2-*, H2O2 | Gene upregulation | [208,218,219*] |

| Stress | Oxidative | S. aureus, E. coli, B. subtilis*, M. marinum† | H2O2 | Gene induction/upregulation | [198,224,239*,246†] |

| Stress | Oxidative | P. aeruginosa | H2O2, temperature fluctuations | Gene activity profile | [204,231,233] |

| Stress | Osmotic | E. coli | NaCl | Gene activity profile | [209,221,222] |

| Stress | Osmotic | E. coli | NaCl | Turgor pressure profile | [206] |

| Stress | Osmotic | P. aeruginosa | NaCl | Ss for survivability | [247] |

| Stress | Heavy metals | E. coli | Cu | Gene activity profile | [200,210,220] |

| Stress | Heavy metals | E. coli*, B. subtilis | Mg | Ss for survivability | [238,248*] |

| Stress | Heavy metals | P. putida, P. aeruginosa * | Cd, (Zn, Co, Cu, Ni)† | Ss for survivability | [204*,†,207] |

| Stress | Ionizing | D. radiodurans, E. coli * | γ-radiation | Ss for survivability | [105,106,223*] |

| Stress | Ionizing | E. coli | THz*, α-radiation | Ss for survivability | [107*,108] |

| Stress | Cell envelope | E. coli, P. aeruginosa * | Membrane-active agents | Gene up/downregulation | [234*,248] |

| Stress | Cell envelope | P. aeruginosa | Antibiotic | Ss for survivability | [232] |

| Stress* | – | E. coli, P. aeruginosa * | Gene disruption/insertion | Morphology, viability profile | [199,(212,235–237)*,225] |

| TCSs | – | E. coli | Gene disruption/insertion | Ss identification/survivability | [120,203,226–230] |

| TCSs | – | B. subtilis, M. tuberculosis * | Gene inactivation | Ss identification | [202*,240] |

| TCSs | – | C. crescentus, S. sonnei * | Gene disruption/insertion | Ss identification | [241,242,243*] |

| TCSs | – | S. pneumoniae, S. suis*, C. caviae† | Gene inactivation | Ss for virulence/survivability | [211,244*,245†] |

| TCSs | – | A. baumannii | Gene disruption/insertion | Ss for survivability | [205] |

Reference sources marked with *, †, utilize primarily (only) target microorganisms, and/or stress agents marked with these special characters. Reference sources marked with † utilize all listed target microorganisms and stress agents including stress agents marked with this special character.

2. Interactions of Microorganisms with Planar Inorganic Matter and Their Importance for a Programmable Biointerface

In this section, we provide a definition for a “smart” material and then formulate possible requirements for typical biointerfacial structure that may be considered programmable. We envision novel types of biointerfaces as promising candidates with wide portfolio of potential applications. In general sense such materials may be completely organic, but the main focus will be on materials and approaches that may be used in the areas of bioelectronics and biosensing.

2.1. Advanced Programmable Materials

Typically, advanced programmable materials are material compositions that possess a set of highly adaptable physical, chemical, electrical or even biological characteristics responding accordingly to changes in external conditions or stresses.[3,4] Specifically, these are materials that may change parameters in a predictable fashion and the degree of certain responses will be based on the independent sensing abilities of the developed structure. Furthermore, the alterations of characteristics for programmable materials are reversible in many cases, thus allowing to restore the original shape, color, potential, pH as example parameters.[4] Currently there are multiple technologies that allow to fabricate structures with programmable behavior, and the more or less sophisticated concepts typically involve a combination of approaches and techniques. Such materials can be applied in various spheres of modern science and engineering and have a wide range of potential applications of design means. Particularly, our focus is on bioapplications of “smart” materials. This is important for proposing a concept of biointerfacial structure as a programmable system and for its further discussion. One has to understand whether the biointerface aligns with an idea of “smart” or, in other words, programmable material. To do such, first one has to define whether reviewed structures and compounds can be considered programmable and to identify the most common types of materials, approaches, and stimuli or conditions that trigger a response. Furthermore, the areas of potential applications or prototype systems that utilize the invented smart-material structures are of a particular focus.

2.2. Current Trends in Programmable Materials

Table 1 summarizes our findings on research results available and allows to make some general conclusions regarding the current trends in programmable materials for bioapplications. In column 1, the materials that serve as a main base for introduced concepts are listed and classified accordingly. Particularly, many papers use several types of nanoparticles[48] and microparticles[49–51] (denoted as NPs and MPs in Table 1, respectively), quantum dots (QDs),[52–54] polymers,[55–58] or hydrogels,[59–63] and in such cases the generalized descriptions were applied.

Column 2 comments on unique “smart” features of reviewed materials and structures that may distinguish the programmable materials from conventional metals, alloys, or polymers. These features range from material disintegration[61,62,64] or swelling[59,60] under certain external conditions, to various types of luminescence[52,53] or fluorescence,[54,65] release of chemical agents[49–51] or toxins (like doxorubicin or DOX-toxicity),[65] and many forms of flexibility or motion (such as triggered folding, bending, returning to its original shape—shape-memory effect).[55,56,63,66–72] As for stimuli (Table 1, column 3) applied to achieve desired response from reviewed programmable materials, they are very diverse and can be generally classified as the following: 1) temperature fluctuations,[59,60,69,71–73] 2) aqueous solutions of solvents or water,[51,54,62–64,74–76] 3) pH level-associated changes,[50,64,77] 4) chemically triggering agents,[49,50,78] 5) influence of magnetic field,[55,73] electrical,[48,66,70,79] or mechanical[61,80] stimulation, and 6) various types of irradiation (near-infrared (NIR) or visible light).[55,56,74–76,81–83] Finally, the potential applications of the programmable materials are listed in column 4. The concepts and materials are used or to be used in bioimaging,[53,54,58,60–62,64,65,82] drug delivery,[48–51,60,63,65,82] soft robotics,[55,67,71–73,79,80] and biosensing[66,68–70,78] or bioelectronic[73,80,83] systems.

Taking a closer look at the variety of materials utilized in programmable systems and listed in Table 1, it is possible to classify them according to their form or structure as 1) particles (top sector of Table 1), 2) layers or fibers: layers of polymers and hydrogels (middle sector in the table), 3) composites (bottom part of the table), and even hybrid structures where inorganic layers are interfaced with tissue. It is important to note that the most utilized groups of materials in programmable compounds development are hydrogels and polymers. For example, poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS),[55,79] polyolefin,[56] polycaprolactone (PCL)/hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI)/butadiene (BD) compound,[69] poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG),[61,80] chondroitin sulfate,[62] poly(glycidyl methacrylate) (PGMA),[78] polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB),[68] poly-N-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAM)[83] are among the polymers used to create nanofibers, composites, hydrogels, and other hybrid structures. Additionally, some organic compounds such as dextran[49] or 2-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA),[50] keratin,[57,58] and resin[67] serve to accomplish similar aims.

For the purposes of bioelectronics one often needs to examine the use of inorganic entities such as metals and semiconductors. Thus, gold (Au),[48,65] iron (Fe),[67,73] platinum (Pt),[72] rhodium (Rh),[68] gallium (Ga),[71] silicon (Si),[51] tungsten disulfide (WS2),[52,53] molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), titanium dioxide (TiO2),[81] boron nitride (BN),[53] and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)[74,83] are common representatives in materials systems we have reviewed. In addition, there are examples of review papers on inorganic substrates utilizing them as smart materials, and reviews on interfacing such materials with different biological entities. For instance, Jeong et al.[84] discuss the development of hybrid gold nanoparticles for diagnostics, tumor treatment purposes, and Ping et al.[25] comment on approaches and benefits of transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) nanosheets for biosensors. Apart from that, some studies[25] discuss the importance of developing the inorganic substrates as systems that react to the presence of certain types of organic matter, which renders them programmable interfaces serving as sensor devices. Additionally, another example by Liu et al.[85] discusses how inorganic substrates can accommodate living cells and form a stable structure.

Studying the examples from the Table 1, it is possible to conclude the fabrication methods are very different in its nature and there is a wide range of technologies that render the materials with “smart” behavior. For example, polymer contraction or casting, novel fabrication methods and solution formulation approaches along with creating mixtures and substances that respond to various stimuli allow to obtain “smart” structures with a controllable way and degree of response.[4] Here it is also necessary to acknowledge that the stability of a substrate in specific environments can play a crucial role in its biointerface functioning. The fabricated structures should have stable parameters over time under the designed conditions, thus making their behavior reliable and predictable.

Typically there are several available paths toward the creation of programmable materials: 1) as one-layer structure consisting of one or several materials and providing the reaction to external stimuli (an example can be seen in the work of Ionov et al.[86] which is incorporated into Figure 2); 2) as a structure with two, three, or even more layers, which is usually a combination of materials with different abilities. The structures consisting of several materials offer more ways to define their structure: the contents can be mixed, patterned, assembled layer-by-layer, and many other combinations. A drug-releasing shape-memory polymer offered by Wischke and co-workers[87] (Figure 3) serves as an example of such mixture of responsive and active materials. In addition, this second approach allows to design very complex systems that may respond to a set of external stresses separately or simultaneously.

Figure 2.

Types of simple deformations in shape-memory smart materials. Different scenarios of deformation of thin films: wrinkling, creasing and folding. Reproduced with permission.[86] Copyright 2012, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Figure 3.

Concept of programming, shape recovery, and drug release of drug loaded SMP devices for biomedical applications. Reproduced with permission.[87] Copyright 2009, Elsevier.

It is important to discuss the potential biological performance of the reviewed materials since it will dictate any possible bio-technological applicability. This aspect can also be reviewed from two different angles. First, the strength of the external stimuli required to trigger the material’s response (i.e., current,[70,79] magnetic field,[55,56,67] and various irradiations[52,53,82]) can cause some unpreferable or even irreversible reactions observed in biological entities involved in the interactions with the “smart” structures. Second, the degree of response from a programmable material may affect the cell attachment or cell survivability on the surfaces made of this material. For example, high surface potential, extreme surface contact angles, significant changes in surface chemistry may bring a high degree of stress in the influenced bio systems. At the same time, changing some material’s parameters (for example, pH[50,77]) from unpreferable to neutral or less severe will allow the bioentity to prosper and express more stable behavior.

Taking a look at the examples from Table 1, we can note that the modalities, materials, and conceptions offered by various research groups may serve as promising candidates in the areas of biorobotics, biosensing, in tissue engineering, and bioimplantable devices.[49,55,67,73,80] Thus, one can conclude that organic and inorganic “smart” materials play a significant role in modern biotechnologies and expanding the portfolio of technologies and approaches allowing to formulate new types of such materials will be highly beneficial.

3. Interactions of Microorganisms with Planar Inorganic Matter and Their Importance for a Programmable Biointerface Conception

The following section and its subsections will describe and discuss the biointerfacial structures and their importance for developing new types of materials. Organic matter interfaced with various surfaces may express a set of responses typically triggered by the properties of organic or inorganic substrates used. Particularly, interactions of microorganisms with inorganic surfaces is in of interest. Based on published studies inorganic substrate/microorganism biointerfaces can serve as materials with programmable properties and numerous potential applications.

3.1. A Biointerface as a Programmable Structure

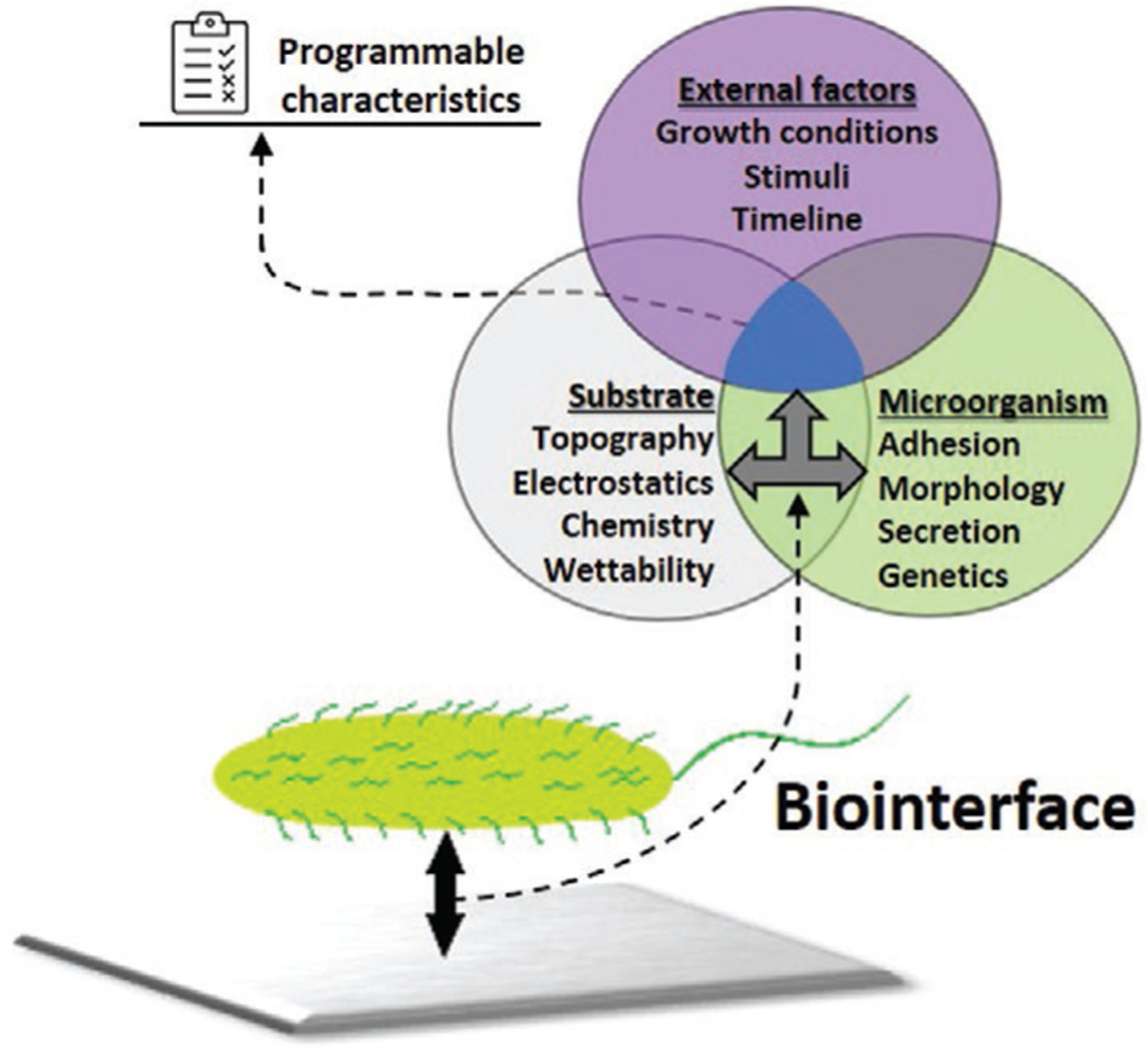

The most generalized and basic definition of a biointerface available elsewhere[89] denotes it as a region of contact between a biological matter and a substrate. Important to add is that the substrate can be also organic or inorganic, and by biological matter one can assume any living organism or organic material. The Figure 4 serves a pictorial representation of the conception of a biointerface. In terms of using it a “smart” material, we define a biointerface as a structure where an inorganic (or organic) surface makes a stable contact with a biological entity. As it was stated before, the biological matter in this structure (biointerface) can be represented by a list of candidates, and they can make a contact with a surface in several forms. For example, a biomolecule or living cell,[90,91] virus,[22] bacteria,[92,93] yeast,[94] fungi,[95] and others[96,97] may be represented as a single entity (left side of the figure), as well as in a form of a tissue or a mature biofilm (right side).

Figure 4.

General conception of a biointerfacial structure.

In general sense one can assume that the contact occurs between a biological object and a substrate, but there are multiple cases (as it can be seen further in the manuscript) when substrates can be functionalized.[96,98–102] This scenario brings additional aspects in the interactions happening within the biointerface. Some agents may be used to provide better cell attachment, others express biocidal properties or, conversely, make the substrate neutral and protect the bio tissue from potential harmful behavior of some materials.

The substrate-bio entity interactions may have different origins and each particular case should be considered. For example, a microorganism may experience direct interactions of its cell membrane and chemical agents released from the surface of a substrate material.[103,104] Furthermore, the bulk of a substrate material may provide some effects triggering a slow passivation effect in a studied biointerface.[93] Apart from that, stimulations (such as electro, radio, and magnetic) applied to the substrate material (or provided by it) can serve as factors influencing the properties of cells or biofilms.[105–108] Furthermore, the reaction of a single cell may be different from a reaction of a resilient biofilm due to group sensing and stress response mechanisms typically developed in such communities. Additionally, the responses observed in different types of microbes (like Gram-positive[109–116] or Gram-negative[117–119]) or even among different strains of the same microorganism[93,120] can vary significantly allowing virtually infinite set of “substrate/biocell” combinations to be used for particular applications and conditions.

The biointerface as a whole (as a structure) can be denoted as a type of novel material with a wide set of characteristics and potentially programmable behavior. The control over this behavior and stability of the entire system is governed by the characteristics of the substrate as well as by the reactions (morphological, physiological, genetical) produced by the biolayer. Quantifying all these factors in conjugation with each other, can permit to treat the inorganic substrate–microorganism biointerface as a “smart” material responsive to possible changes in external conditions. As stated, a typical biointerface consists of at least two layers where the substrate can react to stimuli and can influence the biolayer.[89,94,121–123] Thus, a combined eaction of the entire structure is observed, and this system becomes another layer of sophistication among next generation of responsive biomaterials. Taking this into account, one can view the “inorganic substrate–microorganism” biointerface as an advanced programmable material that can be used in bioelectronic or biosensing applications. Furthermore, the findings from the Table 1 on conductive and semiconducting materials that may be formulated as micro- or nanostructures support the idea of using them for bioapplications. This brings us to the next step which is to identify the components and possible programmable parameters of “smart” biointerfaces.

3.2. Inorganic Materials Interacting with Microorganisms

Following the logic described in the construction of Table 1, first we try to identify the common trends and the set of most popular materials in the area of interfacing inorganic matter with different microorganisms. Table 2 presents a summary of representative findings of common inorganic substrate material interactions with microorganisms. These materials are not considered as “smart,” however their use and proper modification, and subsequent interfacing with microorganisms can lead to the creation of programmable biointerfaces.

The physical parameters of a substrate as well as long-term stability of its structure define the behavior and even overall survivability of a biointerface. For example, the degradation of hydrogel-based structures or some polymers in physiological conditions as well as dissipation of certain silicon-based nanomaterials in biologic fluids compromises the development of their nonconventional applications. Supporting the idea of a stability importance, the majority of reviewed studies focus on bio and biomedical applications that are used to improve the durability and stability of implants or other devices in the context of human or animal tissue as well as the antibacterial and antifouling properties of these materials. Column 1 identifies the material(s) studied from a reference source. Column 2 comments on the type of the surface that was created. For example, the materials are commonly used in the form of thin films[98,99,129–133,100,103,104,124–128] nanopatterned fiber,[134–136] nanopowder,[137,138] or nanorod[139,140] coatings on various test substrates (i.e., glass, steel, and specific polymers). It is important to note, that in many cases thin films can experience further functionalization with antibacterial or chemical agents altering adherence, roughness or other properties of utilized substrate.[94,96,144–147,101,102,127,135,136,141–143] The typical fabrication methods used are: sol–gel coating,[98–100,130,137,141–143] atomic layer deposition,[95,125] sputtering,[126,136] successive ionic layer adsorption reaction (SILAR),[101,127] and metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD).[94,147,148] Column 3 summarizes the types of microorganisms deposited on the substrates. Furthermore, additional factors like external stimuli (i.e., UV[92,93,123–125,128,129,132,137–140,95,141,144,146,98,100,102–104,109,110] or visible light[130,131,134,149]) may be introduced for the purpose of cleaning, changing material’s characteristics or boosting reactions happening within the biointerfaces. Column 4 summarizes applications and use of such external stimuli. Finally, column 5 represents a brief summary of the general purpose or reported potential application(s) based on the studies performed.

The primary goal of most of the research in the area of inorganic material/bacterial cell interfaces is to characterize materials with particular capabilities, such as antifouling or antibacterial properties (Table 2). At the same time, in certain cases the summary was broader, and a wide set of biointerface or microorganism characteristics were obtained.[98,109–111,124,150,151] The most common inorganic materials used in biointerfacial structures are metal oxides such as ZnO,[95,98,139,140,99,101,124–127,133,134] TiO2.[100,102,136–138,141–146,103,104,128–132,135] These materials have been demonstrated as effective antibacterial coatings. For example, as it was shown in studies of Park et al.,[125] or Sunada and coworkers,[129] thin films of ZnO or TiO2 express antimicrobial behavior. Such materials, are being applied in implants, such as hip or knee replacements, medical devices or hospital surfaces reduce the risk of contamination. The success of the coatings was verified by testing a range of microorganisms both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, which also represent a broad range of pathogenicity, biofilm formation capabilities, and cellular structure. The species tested include microbes associated with human infections from gram negative bacteria such as: Escherichia coli (E. coli),[43,98,129,130,134,137,139–143,99–103,124,126,128] Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa),[92,103,104,123,134,135] Proteus vulgaris (P. vulgaris),[95,101,127,134] Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii),[117] Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae);[101] and gram positive bacteria such as: Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis),[95,134,151] Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus),[99,101,111,125–127,146,152,153] and members of the same family Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis)[109,110] and Staphylococcus haemolyticus (S. haemolyticus),[127] the tooth decay causing bacterium, Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans).[132] Other examples that can be found in the table include such bacteria as the gram negative mineralizing bacteria Shewanella putrefaciens (S. putrefaciens),[98] the skin microbiome gram positive bacterium Micrococcus lylae (M. lylae),[144] the industrially relevant gram negative bacterium, Streptomyces avidinii (S. avidinii),[147] the large gram positive soil bacterium, Bacillus megaterium (B. megaterium),[138] and the extremophile, radiation resistant gram-positive bacterium, Deinococcus radiodurans (D. radiodurans).[105,106] Eukaryotic fungal microbes included in these studies were the agriculturally important “black mold” filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger fungi (A. niger)[95] and the fermentation industry cellular yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae).[94] This range of microbes represents not only a diversity of species and genomes but also other cellular properties such as the composition and mechanical properties of the cell wall. Microbial cell walls are structural and sensory components of these cells and play significant roles in the interfacial interactions.

Furthermore, the characterization of the interactions between a substrate and microorganisms requires one to define the specific material properties of the surface and the microbial response to these properties. As it was reviewed by Tuson et al.,[20b] there are many ways in which the substrate may influence the mechanism of bacterial attachment(adapted representative scheme can be seen in the Figure 5). For example, a direct correlation between surface roughness and cell attachment will play a key role in the development of new “smart” materials or devices that will interact with living tissues or biofilms. High degree of roughness allows bacterial strains such as S. aureus and P. aeruginosa to increase their adhesion rate in orders of magnitude.[154] Surface wettability, which is also related to roughness or functionalization of a surface, is also known to regulate bacterial cell attachment and influence antifouling properties of substrata.[102,155–157] In contrast, surfaces possessing suppressed electrostatic interactions, weaker van der Waals forces, and short-range interactions (e.g., hydrogen-bonding) that were altered due to chemical composition changes and were harder to colonize and to form a mature biofilm.[118,158–160]

Figure 5.

Substrate properties and their potential effect on cellular attachment. The image here is reproduced from an image in ref. [20b] that was adapted from a figure originally published in ref. [20a]. Adapted with permission.[20a] Copyright 2011, The Materials Research Society, published by Springer. Reproduced with permission.[20b] Copyright 2013, Royal Society of Chemistry.

In some cases, the application of a surface coating plays two roles, one being antimicrobial. As an example, Charville et al.[90] discusses nitrogen oxide (NO)-releasing surfaces that disrupt normal operation of cellular machinery. Such coatings may significantly enhance certain abilities while being applied to various inorganic substrates. Furthermore, Ti-based alloys with additions of silver (Ag) and gallium (Ga),[117] or aluminum (Al) and vanadium (V) (denoted as Ti–6Al–4V)[110] provided enhanced tissue adhesion and compatibility with mammalian cells, while demonstrated improved biocidal and mechanical properties due to their unique crystallographic and chemical structure.[109] This duality is challenging in that at a fundamental level all cells share the same components (i.e., lipids, protein, and carbohydrate) and the interface needs to deal with particular aspects of two different cell types.

As it was briefly discussed in Sections 2.1 and 2.2 (Table 1), an alternative strategy is to use a set of materials that will be possessing a set of diverse characteristics that originate from contributing components. When two or more materials are combined in one structure, they may be assembled in many different ways that all can obviously have potential pros and cons. They will depend on particular method and configuration. Specifically, a biointerface consisting of several patterned materials having an optimum crosstalk with biological matter can express a diverse set of reactions and unique or untypical behavior. At the same time, having two materials in layer-by-layer configuration may sometimes cause the shielding effect and some expected responses may not be observed in the formulated biointerfacial structures. Thus, paying special attention to such aspects of the biointerface development, it is possible to create novel types of “smart” materials with an impressive set of characteristics.

Most notable example of the already existing multimaterial substrates is the material composites class. Composites are getting more attention in biointerface applications because of the ability to incorporate interfacial properties more easily and directly. Composite materials such as zinc-based titanium dioxide (Zn/TiO2)[153] and palladium oxide/nitrogen-doped titanium dioxide composite fiber (PdO/TiON)[149] are being used in many application which require catalytic or dynamic activation via light.

An additional group of materials that show promise in programmable biointerfaces due to their utilization in bioelectronics and nascent biocompatibility are groups III–V semiconductors, such as gallium nitride (GaN). GaN, AlGaN, and InGaN, have shown to be biocompatible with a wide range of molecules and cell types including proteins,[147] peptides,[96] or even neural cells.[161,162] Recent work has provided considerable evidence that these III–V semiconductor materials such as GaN/AlGaN, interface with bacteria and yeast and have great potential applications in biosensing and bioelectronics.[43,94,147,163] Moreover, certain works like an article by Li et al.[164] discuss how the surface properties (texture and particle arrangement) of materials like GaN under various surface treatments may potentially alter cellular attachment onto the substrate surfaces. Lastly, work with semiconducting materials such as silicon (Si)[111,150,151] has provided information on their biocompatibility, adhesion profiles, and bactericidal capabilities. Such studies complete the gap in the fundamental knowledge necessary to build and utilize “smart” bioelectronic devices. The focus of the remainder this review is to define a set of surface properties in inorganic substrates that may program and control the microbial behavior. By moving away from the current trend in biointerfaces that only examine biocompatible materials, we can identify more substrate-based material properties that stimulate microorganisms using the same response pathways that enable reactions to various external conditions and functionalizations.

3.3. Physiological Responses within Biointerfacial Structures

As analyzed thus far, the characteristics of a biointerface are formed by properties of a substrate, possible influence of external factors, and responses produced by a biofilm (this scheme can be seen in Figure 6). To work at higher level of complexity and to better identify factors influencing the programmable behavior of biointerfacial structures, we have classified the response of microbes to surface mediated external stimuli on biointerfaces into two categories: physiological responses (Table 3) and genetic responses (Table 4). These two response types are related, and their differences may be debated, but we wanted to distinguish between whole cell responses such as adhesion, proliferation or viability, which may involve multiple responses to a stimulus, or the culmination of the final output of a response to a stimulus. In contrast, a genetic response involves the activation of a singular signal transduction pathway or gene. Much of the work in this area has involved the former types of biological characterization, while we predict in the future with the large availability of genomic and proteomic tools more work in biointerfaces will involve characterizing the latter.

Figure 6.

Schematics of a biointerface characteristics formation. Properties of a substrate along with stimuli and external conditions cause further response from microorganisms on the surface.

We have identified four types of physiological responses that have been observed in studies of microbial biointerfaces: 1) adhesion or adsorption to a substrate, 2) cell proliferation, 3) alteration to cell morphology or biofilm organization, and 4) transformations occurring in cellular secretion processes (Table 3, column 1). As with the studies in semiconductor/interfaces, a large collection of microbes has been examined, some of which are associated with human disease, while others are important for synthetic or industrial processing. As it can be seen, E. coli,[103,113,168–172,114,116,124,150,153,165–167] S. aureus,[103,104,174–182,109–111,132,145,146,165,173] B. subtilis,[151] P. aeruginosa,[104,118,179,180,182–184] and S. epidermidis[109,110,173,176,179] are the representatives of pathogens and monosomal contaminants that serve as perfect model microorganisms for research purposes. Other examples include cultures of A. baumannii,[117] S. putrefaciens,[112,133] Pseudomonas fluorescens (P. fluorescens),[185,186] Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans),[132] Streptococcus thermophilus (S. thermophilus), and Streptoccocus waiu (S. waiu),[119] Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis)[177] and, finally, Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis).[182] Furthermore, some scientists focus on fungi,[95] yeast[94] or algae,[102] thus expanding the portfolio of studied species. In particular, one of these examples from Table 3 is Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (C. reinhardtii)[102]—a freshwater alga that was used as one of the representative organisms attaching to tungstite oxide (TO).

In these studies, a diverse portfolio of the substrate materials has been used (Table 3, column 3). It includes polymers that have been applied in various forms: thin film coatings,[113,165,176,183] brush-coatings,[179] and self-assembled monolayers.[168] Notable polymers reported are: silicone,[173,175,180] rubber,[118] fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP),[165] polystyrene (PS),[115,165] acetal resin (AC), polyethylene (PE) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE),[165] poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS),[169] poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC),[90,183] polyurethane (PU),[114] poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (pSBMA),[114,172] poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE),[115] poly(ethylene glycol) with b-cationic polycarbonate (PEG-b-PC),[180] poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), and poly(propylene oxide) (PPO),[179] poly-l-lysine.[170] Important to notice, that even though polymers like FEP, PP, PS are considered organic compounds, but may still be used in compound materials as functionalization agents providing better cell attachment or suppressing some reactive behavior of inorganic substrates discussed further. For example, some seminal works like Absolom et al.[165] develop a basic understanding of how these and similar polymers affect microorganism attachment and growth. Metals, oxides and semiconductors have been used as planar, flat surfaces, or in complex composition either doped with nanoparticles, or formulated as alloys. The examples from the table include Al,[118,119] Zn,[119] Cu,[119] Ti,[117,181] Fe,[112]Si,[111,150,151] and glass,[166] stainless steel,[118,119,171,186] TiO2, [132,146,152,184] ZnO,[124,133] tungstite oxide (WO3 ·H2O) (denoted as TO),[102] Ti doped with Ag or Ga,[117] TiO2 doped with Zn nanoparticles,[153] ZnO doped with Ag nanoparticles,[124] and Ti6Al4V alloy.[109,110] Composites are represented by Ni–P–TiO2–PTFE,[185] VO2/W.[178] Lastly, some less common examples are represented by lead-acetatesoaked paper strips (Pb(Ac)2) for testing a reaction of bacteria to stress conditions,[182] or biopolymer chitosan (CS) doped with Ga,[176] used as a coating material.

Accessing substrate surface properties and correlating them with physiological parameters of biofilms can serve as a starting point for the development of novel types of materials with “smart” characteristics or responses. For example, surface roughness and wettability may significantly alter the cell attachment rate. According to Balazs et al.,[183] surface treatments decreasing a water contact angle of PVC substrate at 75–90% allows to achieve a 70% reduction in bacterial adhesion of four different strains of P. aeruginosa bacteria. In addition the nature and the magnitude of surface charge also alter bacterial adhesion and even influence the morphological structure of a biofilm: bacteria may form mushroom-like structures on antibiotic substrates possessing negative charge opposing to flat structures on positively charged substrates.[118] Thus the initial characterization of substrates plays a significant role and needs to be considered while performing research activities.

Another aspect of the reviewed studies that is overlooked and critical for compatibility, is the mode of delivery to a surface as any environmental/external condition may influence behavior, even after incubation on the surface. In most of these experiments, the microbial cells were delivered to the surface substrate via either direct contact with a droplet of cell suspension,[145,146,149,150,171,175,181] or with solid nutrient media (such as agar), which is followed by a period of incubation[92,93,123,146,172,173] in order to provide a standardized and simple system for the application of microbes to an interface. However, these methods are in most cases a less than realistic presentation of microbial cells interactions with a substrate. Foremost, the number of cells per unit volume are extremely high and, in many cases, may display different behavior through mechanisms such as quorum sensing when compared to smaller groups of cells or even single cells. In deference to this, some studies have begun examining formation of a biofilm in a flow-chamber[109,113,179,186,187] or exposure of low levels of microorganisms dissolved in liquid media to the material in a culture tube.[124,169,176,180,183,188] These types of procedures are often performed in an incubator at optimal growth temperature, typically 36–38 °C (for human related microbes, such as E. coli), to maximize the proliferation rate.[124,150,152,169,173,180,181] However, some groups are beginning to consider alternative culture conditions such as culturing microbe at room temperature to test biointerfacial response under particular conditions.[95,98,130,174,175,188] The challenge of these endeavors is to design experiments that enable proper and careful characterization of the interfacial properties while not compromising the growth and viability of the microorganism. Furthermore, it is necessary to follow-up these experiments by treating a biointerface with cell viability assays followed by microscope examination and cell counting (quantifying the bactericidal properties of the material).[109,117,150,152,176,179,181] Other approaches to maintaining this consistency involve the removal of cells from the material and amplify clonally,[98,153,171,173,180,189] thus multiplying the quantity of cells that were influenced by intrinsic properties of utilized substrates. The above mentioned freshly grown cells can be isolated for further characterization and used in other experiments.

Most of these examinations of physiological activities of microbes at interfaces involve surface modifications or an additional step of substrate preparation. Different surface treatments have been applied during performed experiments to change, activate, or add specific properties to the surfaces (Table 3, column 4). Utilized surface treatments include opsonization, in which a surface is functionalized with immunoproteins or antibodies. For instance, treating biofilms with immunoglobulin G resulted in multiple reactions including increased phagocytic ingestion and increased hydrophobicity.[165] Other modifications include: surface plasma treatment (which alters surface chemical composition, wettability, and roughness),[183] antibiotic treatment (with antibiotics such as gentamicin, ampicillin, and nalidixic acid,[182] heparin and hyaluronan,[175] rifampicin, triclosan and trimethoprim[173]), and irradiation with UV light.[103,104,109,110,132] Also, polymeric coatings: PLL-g-PEG, PLL-g-PEG/PEG-RGD, PLL-g-PEG/PEG-RDG,[152] octadecyltrichlorosilane (ODTS)[175] that offer antifouling capabilities were implemented by researchers. Important to note, that some treatments may be used for routine surface preparation, while others change the initial material significantly and, sometimes, irreversibly. In these cases, the biological entity will be interacting with the modified materials and will express new (or additional) reactions. Such situations should be carefully considered by the researchers since they add another degree of freedom (and, obviously, bring some sophistication) into biointerfacial studies. Additionally, most of the work that involves physiological alteration of microbial behavior has not been used in studies of biointerfaces with semiconductor materials, which often have unique surface properties such as charge and compositional differences.

The predominant type of materials used in reviewed studies are various polymer films, glass, steels, and alloys. Investigating adhesion, proliferation, secretion, and morphology of biofilms formed on semiconducting materials (such as described in Table 2) becomes a very important research topic for scientists who tailor inorganic materials and their potential biological implementations. At the same time, the portfolio of substrates is diverse, and areas of their possible applications are very broad, so it is hard to simply correlate surface parameters with physiological properties of microorganisms adhered. For example, hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces may express opposite trends in colony proliferation under different environments[190] However, it is possible to identify some trends of using surface treatments of various substrates to form zwitterionic coatings that will suppress a bacterial adhesion and at the same time allow attachment of certain necessary cells like osteoblasts or fibroblasts. Also, a perfect example of programmable substrate for biointerfaces is combining several materials as a single compound and activating the generation of reactive oxygen species. This can be achieved via various types of photocatalysts that alter morphology and adhesion of biofilms and can be classified as another popular way of substrate formulation for biological applications.

In some studies, external stimuli have been used to directly influence the biofilm on the interface, thus exploring the reaction of microorganisms placed on a substrate under changing external conditions. For example, a set of studies uses low or high temperature,[102,146] visible light,[131] metal salts (like Ga(NO3)3 and FeCl [182,189] or chemicals and surfactants (glutaraldehyde, ortho-phthalaldehyde, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, benzalkonium chloride, sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium hydroxide, sodium hypochlorite)[186] dissolved in the media, as factors activating processes of biofilm morphology and growth rate alterations. The goal of these surface treatments is to develop new ways to control cells and specifically microbial behavior. Toward these ends, surface treatments have led to the development of novel materials (Table 3, column 5). In many cases changing the abiotic component of the interface resulted in some sort of physiological response from the microbe, i.e., changes to adhesion, proliferation, degradation profiles, antibacterial behavior, or changes in morphological structure of biofilms. Particularly, authors quantified attachment and growth rate of biofilms on various materials,[102,109,151,165–168,171,173,183,184,186,110,111,119,124,132,133,146,150] antifouling and antibacterial capabilities of substrates and surface treatments, [102,103,152,153,169,170,175,176,178–181,104,185,113,114,116–118,132,146] and biofilm morphology alterations.[118,133,151,167,168,176] As for internal changes in microorganisms, researchers have been able to access secretion modifications: decreased or increased production of metal ions in signaling systems (Ss),[112,115] or even ability to produce gas (H2S) to resist antibiotic treatment.[182] Furthermore, some sources from the secretion group[112,115] also comment on the operation of signaling systems, which are related to the topic discussed later in the Table 4 (genetic responses produced by microorganisms).

3.4. Genetic Responses in Biological Systems

The area that holds the most promise for characterizing the microbe/substrate interaction at the cellular levels is the identification of specific genetic responses of a microorganism to a particular material property (Table 4). Microbes have evolved a complex network of signal transduction and transcriptional responses to many environmental stimulus and new material properties of a substrate will be obviated by the identification of specific cellular responses that are activated by these properties.

All microbes use signal transduction systems that are based on several protein/enzyme based cellular components: a membrane-based receptor, intracellular transduction enzymes, and transcription factor that triggers modification of gene expression.[191–193] Genetic response of microorganisms works with cellular regulatory systems to alter and control cellular and physiological processes. In bacteria, many of the stress response mechanisms involve a two-component signaling system (TCSs) in which specific external factors (e.g., ROS, heavy metals, pH) activate a membrane-bound receptor which triggers an intracellular enzymatic pathway that results in the expression of specific response target genes. Figure 7 adapted from Gómez-Mejia et al.[194] serves as schematic representation of the operation of such TCSs in a microbial pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae).

Figure 7.

Graphical illustration of stress-reactions via TCS in Streptococcus pneumoniae. The figure depicts potential activation conditions and responses of TCSs system (by specific protein activation). Adapted with permission.[194] Copyright 2018, Elsevier.

Crosstalk between various TCSs coordinate stress responses from multiple stresses which provides the cell an internal mechanism to adapt to constantly changing variety of environmental conditions.[191,195,196] In addition to responses to environmental stimuli such as pH or ROS, bacteria and other microbes have evolved intercellular signaling mechanisms that enable communication and coordination of individual cells within a population of microbes or biofilm. This group-developed cell behavior in biofilms is called quorum sensing. In the context of biointerfaces as programmable materials, this can be considered another external stimulus that indirectly arises from a substrate/cell interaction. Microorganisms utilize the secretion of small analytes to share information of external stress conditions with a large group of cells thereby coordinating a collective biofilm response. In particular, gram-negative bacteria use autoinducer agents and genes alteration to initiate the reaction across neighboring cells.[192,193] How this impacts biointerfaces is unclear, but given that quorum sensing is a function of cell number and density, during the characterization of material/bacteria interaction the cell culturing conditions and age must be considered as an external factor when examining microbial reactions at biointerfaces.

In addition to the acute responses via signal transduction, long-term adaptation to chronic environmental stresses will result in permanent changes to microbe genomes and the accumulation and selection of advantageous mutations that can significantly change concentration or structure of master regulators within a cell and start a population of new, modified generations of cells.[191,197] The genetic response to biointerfaces provides the highest resolution tool for defining the microbe/substrate interaction and will bring biointerface research to the next level because one will be examining specific gene/properties interactions. This information is predictive and allows controlled design of materials that elicit specific and desirable microbial responses to a surface. It will allow one to coordinate external stresses or continuous use of certain operating conditions that may affect the populations of cells forming a biofilm, which will finally provide information critical for a number of industries from biomedical device design to fermentation. This knowledge has the potential to aid in the development of more advanced types of “smart” biointerfaces and improve their potential long-term performance.

Table 4 summarizes our findings from papers related to a genetic response that is caused by external stress (denoted as “stress” in the table) and from research related to a two-component signaling system in microorganisms (“TCSs,” as it is abbreviated in the table). The first column identifies the main purpose (or focus) of the studies, which can be stress-related study, or TCSs study, as it was stated before. General trends are such, that stress papers utilize various agents to see the changes in gene expressions, growth or morphology profiles. The majority of TCSs papers do multiple genetic modifications within a cell to record how these perturbations can cause further gene concentration reactions, thus allowing to identify particular genetic components of analyzed signaling systems.

All genetic/stress responses to a surface interaction will have some connection to a change in physiology. Many microbial cells will respond genetically to environmental stress by changing their overall morphological appearance, such as presence or absence of pili, fimbria, shape, or attachment rate alterations. We have grouped the papers in the table according to the type of stress. As with the physiological examination of microbial interfacial reactions, genetic responses, target microorganisms are either grown in a liquid media (nutrient broth) and incubated in cell culture tubes, flasks or culturing chambers,[198,199,208,200–207] or grown in Petri dishes on solid nutrient media like agar.[106,107,209–213] Given the sensitivity of genetic stress responses, the diversity of these culturing conditions could be a cause for concern for consistency. Based on our literature analysis, relatively small amount of published papers have examined the microbial response to metallic, semiconducting or polymeric substrates and in many cases, cells do not interact with inorganic materials at all, since external stresses may be represented by temperature, pH changes or by gene removal or implantation. Some experiments of genetic responses conducted in homogeneous solutions do not involve the creation of biointerfaces. However, they are important for understanding the processes occurring within the cell and thus can be considered as additional parameters and conditions that should be controlled while formulating the biointerfaces. These types of work are still valid for the purpose of our review since they give an overview of the toolset available for genetic studies in microorganisms. Such tools may be used in multiple manipulations with external structure of cells in various interdisciplinary studies. Six general classes of stresses were identified in these studies (Table 4, column 2). The types of stresses include: 1) environmental stresses, i.e., change in pH, temperature, and similar factors, 2) oxidative stresses, i.e., disbalance between free radical concentration and organism’s ability to neutralize them; 3) osmotic stresses, i.e., intracellular solute imbalance; 4) ionizing stress, i.e., stresses caused by various types of radiation; 5) a stress-response to heavy metal salts dissolved in media; and 6) mechanical or chemical stress disturbing or disrupting the microbial cell wall and affecting a cell membrane, denoted as cell envelope stress in the table. The primary tools for genetic analysis involve direct manipulation of the genome through either deletion, insertion, or mutation of specific genes to access the signaling systems operation.

Similar to previous sections of this review, a wide range of microorganisms has been studied, and, matching the previous tables, E. coli,[107,108,208–210,214–220,120,221–230,157,189,198–200,203,206] P. aeruginosa,[204,212,231–237] B. subtilis,[213,238–240] and S. aurelis[198,213,224] are the most occurring bacterial species (Table 4, column 3), which provides both the identification of novel stress mechanisms that are associated with specific microbes as well as helping decipher ancient stress response mechanisms that are shared by many related microbes. Furthermore, Pseudomonas putida (P. putida),[207] D. radiodurans,[105,106] S. pneumoniae,[211,213] Caulobacter crescentus (C. crescentus),[241,242] and A. baumannii,[205] Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis),[202] Shigella sonnei (S. sonnei),[243] Streptococcus suis (S. suis),[244] Chlamydia caviae (C. caviae),[245] Mycobacterium marinum (M. marinum),[246] and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)[229] were among other microorganisms used for studying the TCSs and mapping their genetic responses.

The generation of the stress is also critical for characterizing these TCS based stress response (Table 4, column 4). The stress agents or factors used to induce stress were diverse. Environmental manipulations such as simple temperature increase or decrease and variations in pH-level,[204,214–216,233] forced aerobic or anaerobic conditions for culture growing in media,[217,229] or media lacking nutrients and causing microorganisms to enter a starvation mode.[229] To introduce the changes in external parameters (temperature, pH level, and respiration conditions), the researchers were tweaking parameters of biofilm incubation in liquid media thus mimicking changes that could happen with cultures in the real-life conditions. By simply increasing incubation temperature or pH level, it is possible to observe an increase in concentration of enzymes and compounds closely associated with TCSs and intercellular salt overly sensitive (SOS) signaling systems in biofilms.[214,216] For example, E. coli expressed a large production and accumulation of indole (intercellular signaling compound) at temperatures around 50 °C and at pH levels of 5–9.[215] Changing growth conditions from aerobic to anaerobic, it is possible to observe an increased concentration of certain membrane lipids in H. pylori, which suggests an activation of particular regulatory systems associated with cell metabolism and growth.[229] Additionally, biofilm density can also cause stress to the culture grown, according to findings reported in this mini review.[213] Thus, even variation of environmental conditions may trigger intercellular signaling and regulatory systems that are associated with further physiological reactions and significantly affect properties of the biointerfaces created. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS), as oxidative stress-agents, while being generated on a substrate or dissolved in media, may cause toxic effects significantly affecting the signaling processes in a cell, be a source of severe damage to its structure, and cause mutations in both growing and stationary-phase cells.[196] To induce an oxidative stress, researchers utilize hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[198,204,218,224,231,233,239,246] or superoxide (O2 ¯), that may be generated on CdSe or CdTe quantum dots under illumination with light,[208] or by using chemical compounds like paraquat—N,N′-dimethyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dichloride.[219] No less important is an osmoregulation within a cell envelope. By varying the concentrations of salts in the surrounding environment, it is possible to control the amount of water that goes out or in the cell which will ultimately affect the production of proteins associated with signaling systems and the secretion processes related to cell survival. Typically, salts like NaCl[206,209,221,222,247] cause substantial changes in osmosis of microorganisms and serve as an agent of osmotic stress. Another stress-factor commonly applied in the microorganism studies are ions of heavy metals: cadmium, zinc, cobalt, copper, nickel, and others, that can be found in the test media or, for example, in soil.[204] The heavy metals accumulated in cells affect the intracellular processes which result in irreversible damage to DNA, disrupt the signaling within a cell and other effects that can be considered genetic response or, in other words, mutation. In many cases to release ions such as Cu+, Cd2+, Zn2+, Mg2+ into the biological systems, the protocols require adding salts to the media where cells are going to be incubated. The reagents used in reviewed papers were CuSO4, [200,210] CuCl2 [220] 2, CdSO4, [204,207] ZnCl2, [204] and MgSO4 [238,248] An alternative way to cause some direct or indirect influence on genetic structure of an organism is ionizing radiation. The radiation can affect the cell directly, by altering the proteins forming a genetic structure, or indirectly, when clusters of reactive species formed and, by interacting with the cell, cause the further genetic reactions.[108] The ionizing stress can occur by various types of radiation: α-waves,[108] γ-waves,[105,106,223] and terahertz (THz)-frequency radiation.[107] To protect the stability of the molecular structure and ensure successful survival of a microorganism, a significant amount of resources is spent to form and maintain the integrity of the cell envelope.[249] Thus, any means compromising rigidness of outer cell wall and disturbing or disrupting the stability of the cell membrane will carry cell-envelope stresses, triggering a cascade of severe physiological, morphological and genetic reactions that can even affect cell viability, virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility.[193,249,250] The cell-envelope stress factors are membrane-active agents: antibiotics (like polymyxin B),[232] disinfectants (such as biocide chlorhexidine, ethanol, sodium dodecyl sulfate, chemicals compounds (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, p-xylene, n-hexane), and various cationic antimicrobial peptides (like melittin, alexidine, poly(hexamethylenebiguanide) hydrochloride, and cetrimide).[234,248] Moreover, apart from adaptive mutations mainly caused by stress factors (so called stress-induced mutation mechanism[196]) discussed previously, many researchers take an approach of direct genetic manipulation.[251–254]

As stated above, the connection between the physiological response and the genetic response needs to be made, and genetic analysis enables this through the direct or indirect examination of genes that have been affected by the processes occurring within a cell. In particular, authors correlate genetic mutations under external stress or genetic modifications (like gene knockouts, implantation of foreign genes) with physiological parameters such as activity of secretion systems and cell viability,[199,212,214–216,225,235,236] lipid concentrations,[229] turgor pressure (a force within a cell pushing against the cell wall) profile[206] and, lastly, morphological changes[199,212,225,229,235,236] observed in studied microorganisms. Furthermore, the purpose of many studies was to identify what TCSs are responsible for microorganisms’ ability to survive.[105,106,229,230,232,238,244,255,107,108,204,205,207,211,223,228] In this case genetic reactions were correlated with viability, cell attachment rate and other important parameters. However, for many TCSs studies a slightly different approach was employed: by performing genetic manipulations and modifications, researchers were identifying the components of signaling systems, trying to find a correlation between damage to one gene and potentially affected activity of another gene.[202,203,226,227,240–243] Also, a significant portion of reviewed papers retrieve activity profiles of genes under external stresses, which can be a set of lowered or increased concentrations of proteins associated with studied genes.[200,204,209,210,213,217,220,221,233] Similarly, some works comment on particular results of genes experiencing downregulation (decrease in activity),[120,234,248] upregulation (increased genetic activity under external stress),[198,208,218,219,224,239,246] or process of stimulation of gene activity (induction).[198,224]