Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Ion channel mutations in calcium regulating genes strongly associate with AngII (angiotensin II)-independent aldosterone production. Here, we used an established mouse model of in vivo aldosterone autonomy, Cyp11b2-driven deletion of TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channels (TASK-1 and TASK-3, termed zona glomerulosa [zG]-TASK-loss-of-function), and selective pharmacological TASK channel inhibition to determine whether channel dysfunction in native, electrically excitable zG cell rosette-assemblies: (1) produces spontaneous calcium oscillatory activity and (2) is sufficient to drive substantial aldosterone autonomy.

METHODS:

We imaged calcium activity in adrenal slices expressing a zG-specific calcium reporter (GCaMP3), an in vitro experimental approach that preserves the native rosette assembly and removes potentially confounding extra-adrenal contributions. In parallel experiments, we measured acute aldosterone production from adrenal slice cultures.

RESULTS:

Absent from untreated WT slices, we find that either adrenal-specific genetic deletion or acute pharmacological TASK channel inhibition produces spontaneous oscillatory bursting behavior and steroidogenic activity (2.4-fold) that are robust, sustained, and equivalent to activities evoked by 3 nM AngII in WT slices. Moreover, spontaneous activity in zG-TASK-loss-of-function slices and inhibitor-evoked activity in WT slices are unresponsive to AngII regulation over a wide range of concentrations (50 pM to 3 μM).

CONCLUSIONS:

We provide proof of principle that spontaneous activity of zG cells within classic rosette assemblies evoked solely by a change in an intrinsic, dominant resting-state conductance can be a significant source of AngII-independent aldosterone production from native tissue.

Keywords: aldosterone, primary hyperaldosteronism, renin-angiotensin system, TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel, zona glomerulosa

Aldosterone production that is not fully suppressed by sodium loading, AngII (angiotensin II) receptor (AT1R) blockade, or mineralocorticoid receptor activation1,2 is recognized as dysregulated and independent of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). This RAS-independent (autonomous) component of aldosterone production occurs within a spectrum of disorders that range from subclinical disease to overt primary aldosteronism (PA). Recently, in acknowledgment of this continuum, the term PA syndrome has been proposed.3,4 Importantly, aldosterone production that is inappropriate for sodium status induces hypertension, increased risk of renal impairment and cardiovascular disease.3,5–9 Although estimates of RAS-independent hyperaldosteronism are high, aldosterone autonomy remains under-diagnosed.10–12

A strong association exists between aldosterone autonomy and genetic variation in calcium regulating genes (Channels: KCNJ5, CACNA1D, KCNK3, KCNK5, CLCN2, CACNA1H and Pumps: ATP2B3, ATP1A1) in adrenal cortical adenomas and micronodules,13–24 underscoring the importance of plasma membrane conductances to the activity-state of aldosterone-producing-CYP11B2-positive adrenal cells.25 Whereas these observations highlight the fundamental biochemical complexity of PA, they also have advanced the unifying hypothesis that disruption of intracellular calcium homeostasis in aldosterone producing cells is essential for—and may be sufficient to cause—the disease state.22,26,27 However, whether intrinsic ion channel dysfunction in zona glomerulosa (zG) cells organized in native rosettes assemblies is sufficient to drive significant RAS-independent, autonomous aldosterone production remains unconfirmed.

In mice, several aldosterone-associated hypertensive models generated by ion channel gain-of-function (GOF, eg, ClC-2 Cl− channels [Clcn2R180Q/+, Clcn2op/op],19,21 Cav3.2 calcium channels [Cacna1hM1560V/+]28) or loss-of-function (LOF, eg, TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium [TASK] channels [Kcnk3, Kcnk9, alone and together]16,29–32) replicate many of the defining features of human PA. Collectively, these mouse models indicate that genetically altered cells, including Cyp11b2-positive cells, can produce mild to severe RAS-independent hyperaldosteronism in vivo. However, this evidence does not exclude possible contributions to the RAS-decoupled phenotype from circulating regulators or extra-adrenal channel dysfunction caused by germ-line genetic engineering of resting state conductances. Indeed, TASK-1, TASK-3, ClC-2, and Cav3.2 are expressed in many tissues, and in the only comparative example published to date, germ-line deletion of TASK-1/−3 channels produces an exaggerated hyperaldosteronism phenotype compared with mice with zG-specific channel deletion.29,33 This difference in aldosterone production between these disease models highlights important amplification caused by extra-adrenal channel dysfunction. In addition, there is accumulating evidence in humans that RAS-decoupled hyperaldosteronism may arise in vivo, in part from an exaggerated response to other stimulators (eg, ACTH34,35). Thus, the question remains: can zG-specific channel dysfunction alone, within an activity-correlated cellular network independent of extra-adrenal contributions and changes in zG-layer architecture, elevate intracellular calcium and evoke autonomous, RAS-independent hyperaldosteronism consistent with that observed clinically in humans? Here, we determine if TASK-1/−3 LOF in mouse zG rosettes, either by zG-specific channel deletion or pharmacological inhibition, can evoke and sustain robust spontaneous calcium and steroidogenic activities in vitro that are independent of extra-adrenal influences and are Ang II-unresponsive.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data and detailed methods are available in the Supplemental Material.

Mice

Adrenal slices from wild-type TASK-1/−3 (WT, AS [aldosterone synthase]+/Cre:: TASK-1+/+::TASK-3+/+) and zG-TASK-LOF (AS+/Cre::TASK-1fl/fl::TASK-3fl/fl) mice with (Calcium imaging), or without (aldosterone secretion), Cre-dependent expression of GCaMP3 were used in all experiments, as previously described.47

Calcium Imaging

Adrenal slices were perfused with PIPES buffer, designed to approximate plasma ion concentrations (in mmol/L: 20 PIPES, 119 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 D-Glucose, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.3 [adjusted with 10 N NaOH]) for 90s (baseline) before application of 0 (basal)-3 μM AngII (angiotensin II). For TASK inhibitor imaging studies, slices were preincubated in PIPES buffer with 200 nM A1899 and 200 nM PK-THPP for 10 min before imaging.

Aldosterone Secretion

Adrenal slices were incubated on polytetrafluoroethylene membranes (Millicell, PICM03050) in 6-well plates (2–3 slices per well) for 2 hours in DMEM/F12 at 37 °C and 5%CO2. Media was sampled from a 30-minute baseline period and then transferred to wells containing either 0-(control), 50-, 100-, 300-, 1000-pM AngII, or TASK inhibitors (200 nM A1899+200 nM PK-THPP) for an additional 30 minutes (drug-treatment period).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Statistics

Unless otherwise noted, data were presented as mean±SEM (scatter plots and point-and-line plots) or median followed by 25–75 percentile values (box and violin plots), calculated from either pooled data from all slices within an experimental group (Figures 2A, 2C, 2E, 3C, 4D, 5C; Figures S3A and S4B), or aggregate data per mouse (Figures 1C, 1D, 2B, 2D, 2F, 3B, 3D, 3E, 3F, 4E, 4F, 5D, 6A, 6B; Figures S3B and S4C). Hypotheses were tested using linear mixed model analysis (see Supplemental Material). Differences among group means were considered significant at P<0.05 using Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. IBM SPSS Statistics software (v28.0.1.1) was used for all statistical analysis.

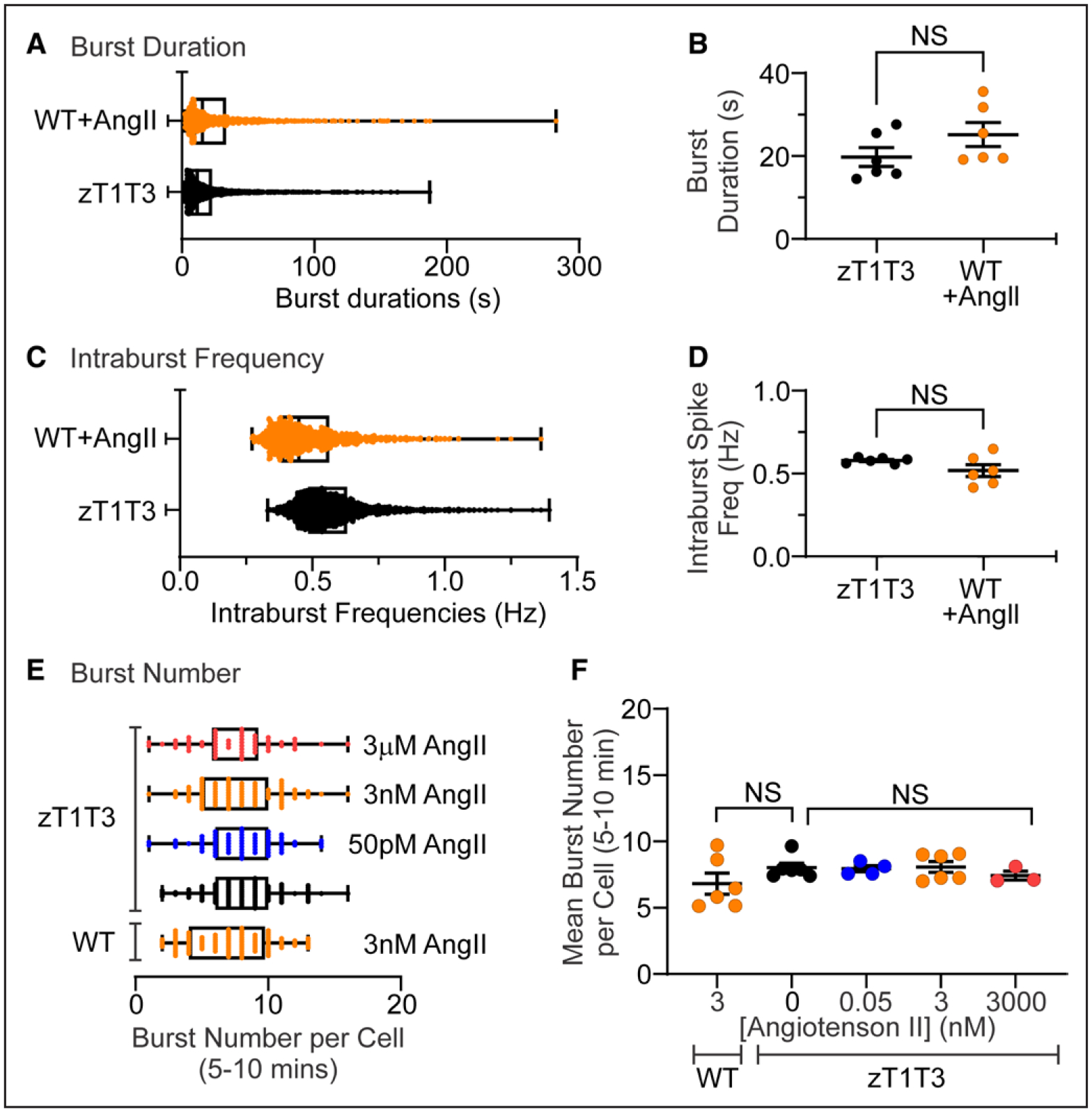

Figure 2. Properties and number of calcium bursts are equivalent between zona glomerulosa (zG)-TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK)-loss-of-function (LOF) and AngII (angiotensin II)-stimulated zG cells.

Distribution and mean duration (A and B) and intraburst frequency (C and D) of calcium bursts in zG cells from zG-TASK-LOF (zT1T3; n=103 cells from 6 mice; black symbols) and 3 nM AngII-stimulated WT (n=102 cells from 6 mice; orange symbols) slices. The distribution (E) and mean (F) number of bursts in the late phase (last 5 minutes of each recording) was invariant across genotype (WT vs zG-TASK-LOF) and AngII concentrations. zG-TASK-LOF+0 pM (n=102 cells from 6 mice; black symbols), 50 pM (n=52 cells from 4 mice; blue symbols), 3 nM (n=101 cells from 6 mice; orange symbols, top), or 3 μM AngII (red; E, n=67 cells from 3 mice, red symbols), and WT slices+3 nM AngII n=100 cells from 6 mice, orange symbols, bottom). Data are expressed as median+25–75 percentile (A, C, E) or mean±SEM (B, D, F); ***P<0.001 or nonsignificant (NS) by linear mixed model with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

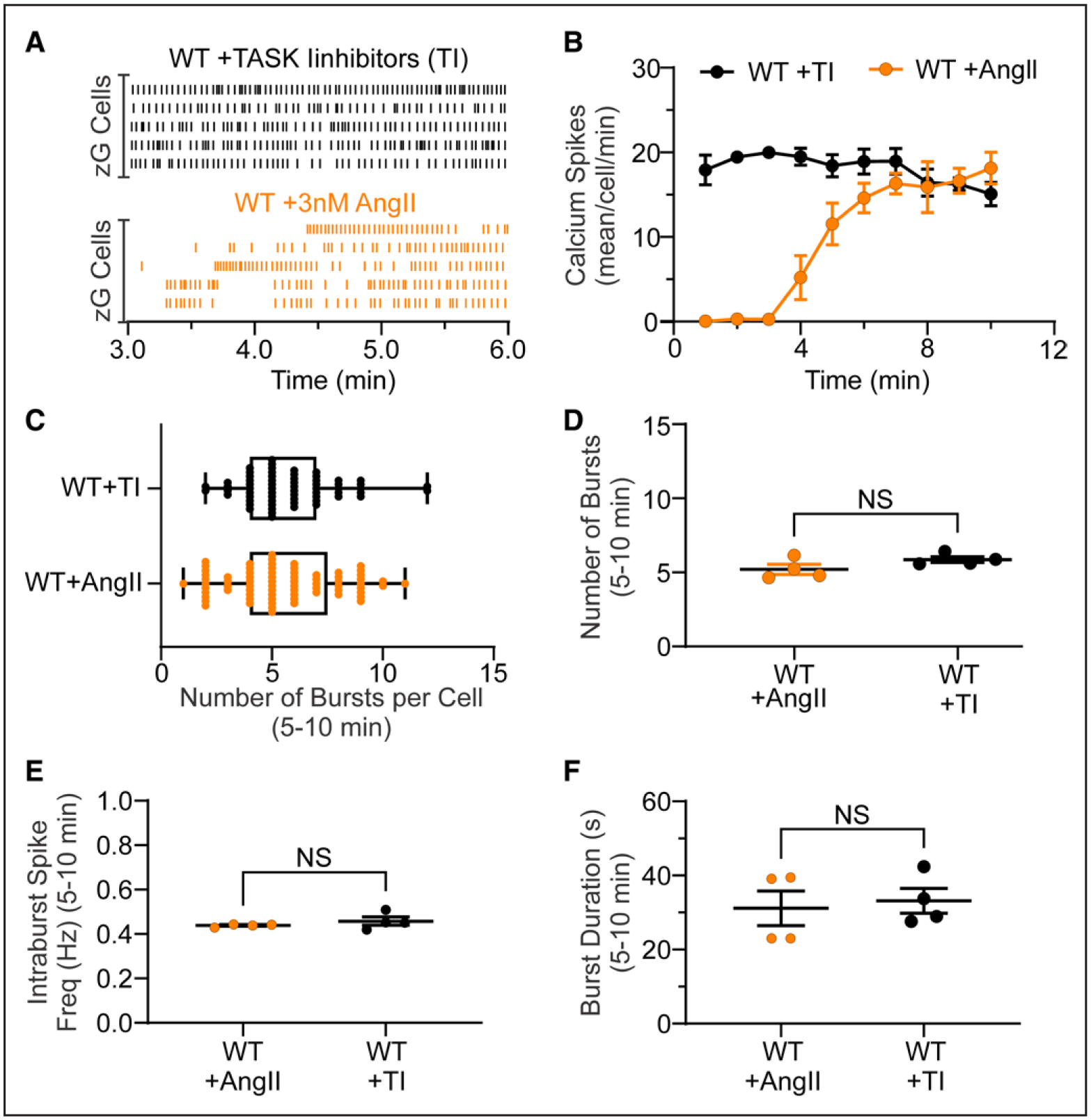

Figure 3. Pharmacological blockade of TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK) channels in WT slices recapitulates calcium responses in genetic zona glomerulosa (zG)-TASK-loss-of-function zG cells.

A, Two representative raster plots of calcium spikes from 5 different cells within a WT slice incubated with TASK inhibitors (TI) for 10 minutes before imaging (A, top; black lines; TASK inhibitors: 200 nM A1899 and 200 nM PK-THPP) or a WT slice stimulated with AngII (angiotensin II; A, bottom; orange lines; 3 nM AngII added after 1.5 minutes). B, Number of calcium spikes per cell in 1 minute bins (Task Inhibitors: n=73 cells from 4 mice, black symbols; AngII: n=66 cells from 4 mice, orange symbols). Number of calcium bursts (C, per cell; D, mean per slice), mean intraburst spike frequency (E), and mean burst duration (F) in TI- and AngII-treated WT slices. D–F, Data are expressed as median+25–75th percentile (C) or mean±SEM (B, D, E, F). Black symbols: TI-treated slices, orange symbols: AngII-treated slices; NS (nonsignificant) by linear mixed model with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

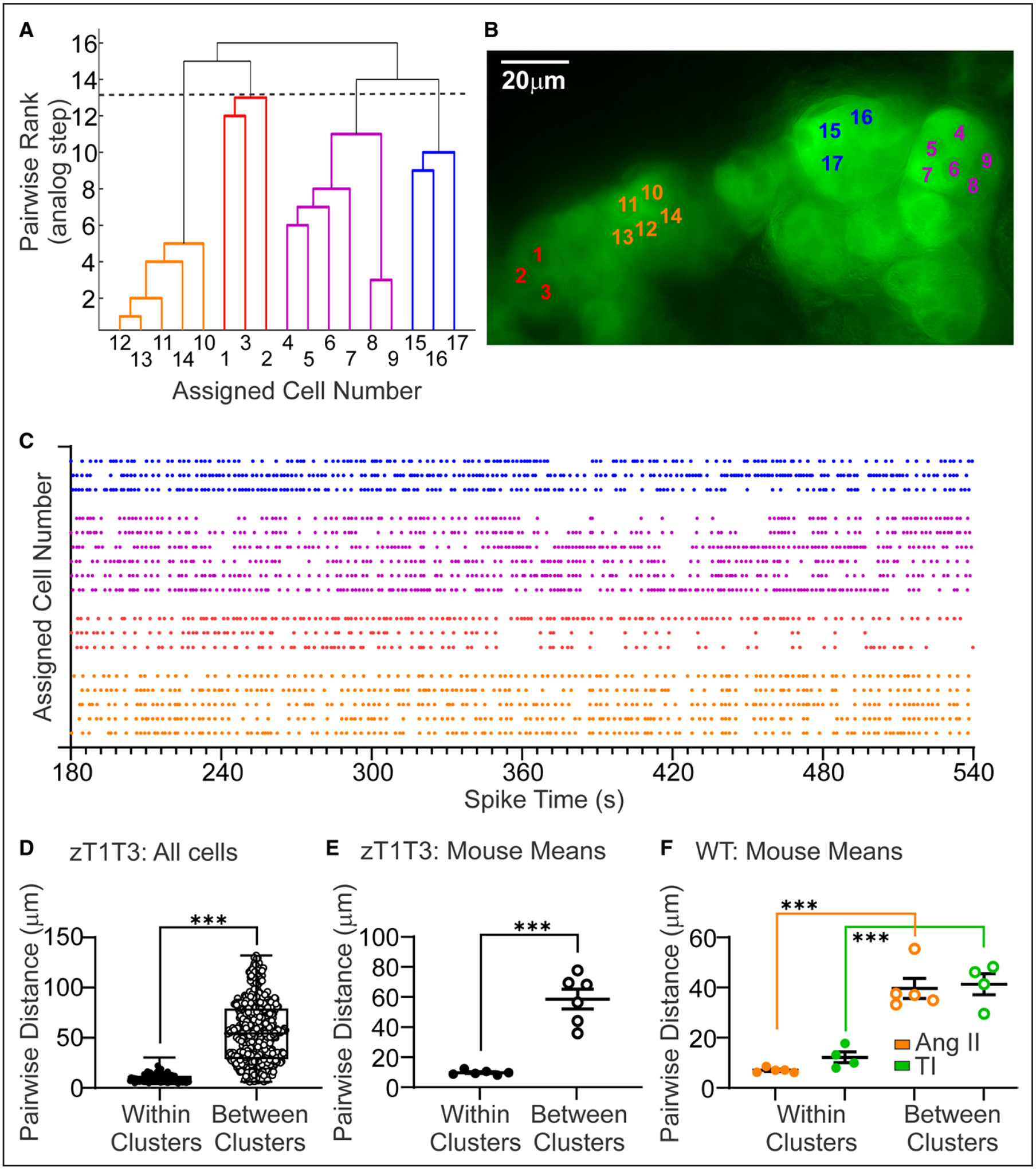

Figure 4. Adrenal zona glomerulosa (zG)-TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK)-loss-of-function (LOF) cells sort into rosette-specific, functional clusters of calcium activity.

A functional clustering algorithm (FCA) applied to calcium activity of zG cells across an adrenal slice grouped cells into functional clusters based on the temporal correlation of spikes between cell-pairings. Dendrogram (A), micrograph (B), and raster (C) of a representative FCA analysis of spontaneous calcium activity among zG cells within a zG-TASK-LOF slice, with each functional cluster color-coded. Distribution (D) and mean (E) of within- (closed symbols) and between- (open symbols) cluster cell-pair distances in zG-TASK-LOF slices (n=720 cell-pairs from 6 mice). F, Mean pairwise distances of within- (closed symbols) and between- (open symbols) cluster cell-pair distances after incubation with TASK channel inhibitors (200 nM A1899 and 200 nM PK-THPP; n=479 cell-pairs from 5 mice, green symbols) or 3 nmol/L AngII (n=825 cell-pairs from 5 mice, orange symbols). Data are expressed as median+25–75th percentile values (D) or mean±SEM (E and F); ***P<0.001 by linear mixed model with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

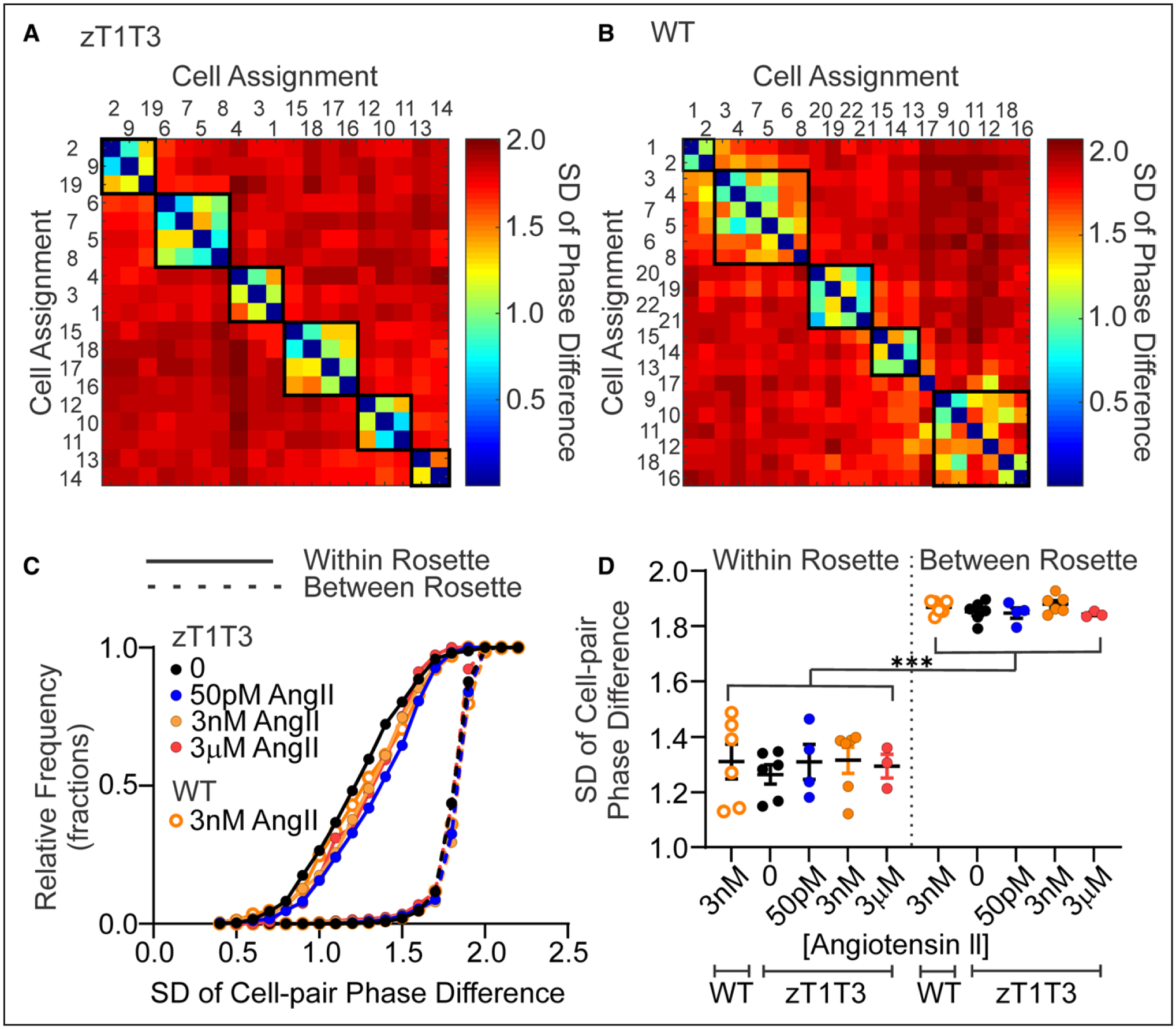

Figure 5. Phase-locking of spike trains from zona glomerulosa (zG)-TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK)-loss-of-function (LOF) cells is independent of AngII (angiotensin II) concentration.

Representative matrix plot of pair-wise SD of the phase difference of calcium spikes within a zG-TASK-LOF (A, zT1T3, spontaneous activity) or WT (B, 3 nM AngII-evoked activity) adrenal slice. Cells are numbered arbitrarily and arranged on the x- and y-axis according to assumed rosette assignment. The intersection of row (Cell x) and column (Cell y) indicates the SD of the cell-pair phase-difference and is color coded to reflect the degree of phase-locking, ranging from red (high SD of phase-difference, little activity coupling) to blue (low SD of phase-difference, phase-locked, high-degree of coupling). Darkest blue results when a cell is paired with itself (eg, Cell 1 on x-axis vs Cell 1 on y-axis) and therefore SD=0, accounting for the continuous diagonal of blue squares on each matrix. C, Superimposed cumulative fractional distributions of phase difference SDs of all cell-pairs and (D) corresponding mean SD per slice, sorted into within- and between-rosettes cell-pairs; from zG-TASK-LOF slices: +0 pM AngII (black, closed symbols; n=1142 cell-pairs from 6 mice), 50 pM AngII (blue, closed symbols; n=1079 cell-pairs from 4 mice), 3 nM AngII (orange, closed symbols; n=618 cell-pairs from 6 mice), 3 μM AngII (red, closed symbols; n=784 cell-pairs from 3 mice), or WT slices: +3 nM AngII (orange, open symbols; n=622 cell-pairs from 6 mice). ***P<0.001 (within- vs between- rosette SD for each concentration of AngII) by mixed model ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

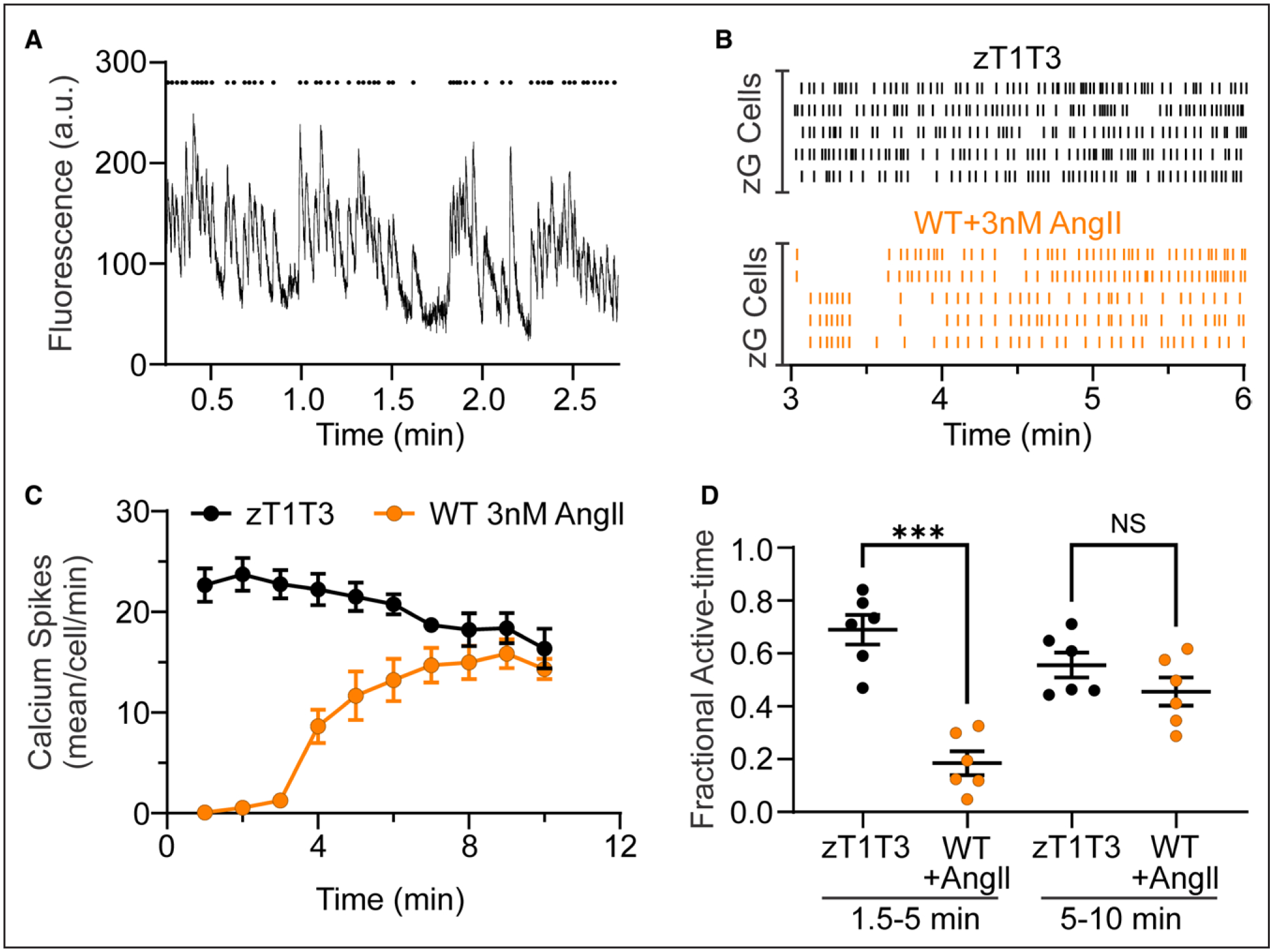

Figure 1. TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK) channel LOF results in robust, spontaneous calcium oscillations, comparable to that elicited by AngII in WT slices.

A, A representative trace (A, bottom) of GCaMP3 florescent intensity over time. Mean pixel intensity of each region of interest (ROI) from a zG-TASK-LOF (zT1T3) adrenal slice, and the corresponding raster plot (A, top) highlighting the timing of each individual calcium spike. B, Representative raster plots of zG calcium spikes in zG-TASK-LOF (B, top; black lines; spontaneous activity) and WT slices (B, bottom; orange lines, evoked-activity, 3 nM AngII [angiotensin II] added at 1.5 minutes). C, Number of calcium events per cell in 1 minute bins from WT (3 nM AngII at 1.5 minutes, n=6 mice) and zG-TASK-LOF (spontaneous activity, n=6 mice) slices. D, Fraction of time in which zG cells were active is significantly less early in the recording (1.5–5 minutes, ie, during baseline and early AngII-stimulation) in WT (n=102 cells from mice) compared with spontaneous activity in zG-TASK-LOF slices (n=103 cells from 6 mice). WT activity attains that of zG-TASK-LOF in the second half of the recording (5–10 minutes), as AngII-elicited activity reaches maximal response. Data are expressed as mean±SEM; black symbols: zG-TASK-LOF slices, orange symbols: WT slices; ***P<0.001 or NS (nonsignificant) by linear mixed model with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

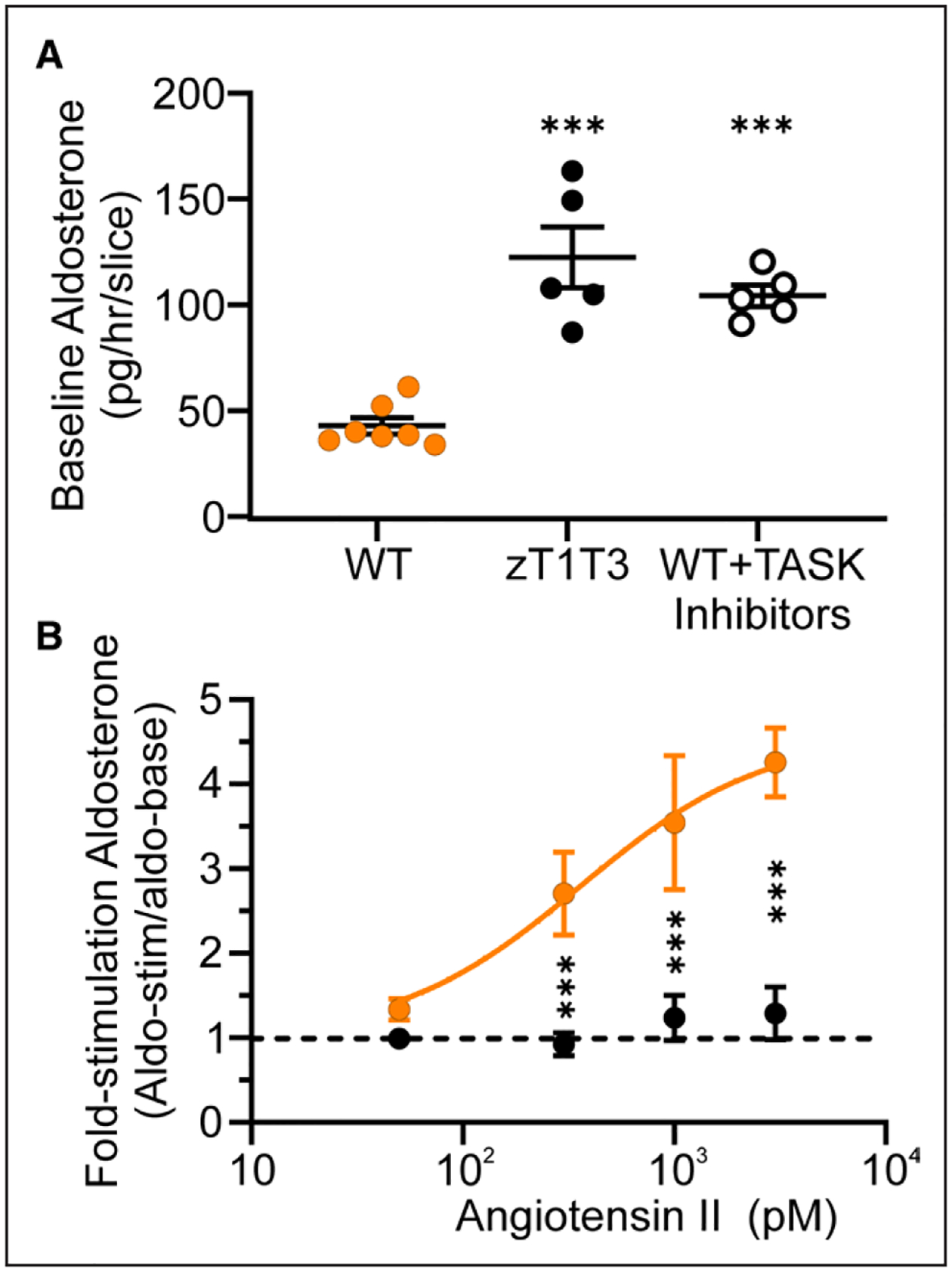

Figure 6. Aldosterone production in elevated and AngII (angiotensin II)-insensitive in zona glomerulosa (zG)-TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel (TASK)-loss-of-function (LOF) compared with WT slices.

A, Aldosterone production pg/slice/h from WT (n=13 wells from 7 mice, orange symbols), zG-TASK-LOF (zT1T3, n=13 wells from 4 mice, black solid symbols), and WT+TASK inhibitors (200 nM A1899 and 200 nM PK-THPP, n=11 wells from 5 mice, black open symbols) slices. B, Ratio of aldosterone production after 30 minutes AngII stimulation (0 [basal], 50 pM, 300 pM, 1 nM, or 3 nM AngII) over baseline secretion (previous 30 minutes) in zG-TASK-LOF (black symbols) or WT (orange symbols) adrenal slices (n=6–12 wells/dose from 4 zG-TASK-LOF and 6 WT mice). Data are expressed as mean±SEM; ***P<0.001 by linear mixed model with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

Study Approval

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

In the outer zone of the adrenal gland, zG cells self-organize into rosette assemblies.36,37 These assemblies consist of 10 to 15 cells that form a central contact site containing adherens junction aggregates. A laminin β1-rich basement membrane encircles, on average, 1 rosette to form interconnected glomeruli, although some larger glomeruli contain more than 1 rosette. Rosette assemblies impart an electrical excitability to zG cells that is not evident following tissue disruption and cell dispersion.38 In these assemblies, zG cells behave as conditional oscillators that generate slow, periodic (0.5–2 Hz) voltage spikes when provoked.38 In turn, these evoked voltage-oscillations drive large oscillatory changes in zG cell cytosolic calcium that principally derive from extracellular calcium entry.39

Here, we targeted GCaMP3, a genetically encoded calcium indicator, to zG cells in WT and tissue-specific TASK-1/−3 deletion (zG-TASK-LOF) mouse-lines, thereby enabling the study of intracellular calcium signals produced by zG cells within their native rosette structure.39 Wide-field microscopy captured calcium-dependent fluorescence signals from individual cells within rosettes.39 The deletion of TASK-1/−3 from zG cells elicited robust, spontaneous, and periodic (~0.5 Hz) intracellular calcium signals immediately from the onset of the recording period (Figure 1A), in contrast to unstimulated WT zG cells that are largely quiescent until provoked by AngII39 (Figure S1). To determine the degree of cell activation evoked by zG-TASK-LOF, we plotted fluorescence intensity over time and identified the peak of each oscillatory calcium signal (ie, each calcium spike). Figure 1B shows spontaneous and AngII-evoked calcium spikes of representative zG cells from WT and zG-TASK-LOF adrenal slices. TASK-LOF zG cells generated highly reproducible spontaneous calcium oscillations within a narrow frequency range (<2 Hz) that were time-invariant (Figure 1C), having a mean fractional active time of 0.59±0.04. By contrast, the addition of 3 nM AngII at 90s of recording, elicited robust, time-dependent activity from WT slices (Figure 1C) equal to that of zG-TASK-LOF activity in the last-half of the experiment (Figure 1D). Thus, zG-TASK-LOF was sufficient to initiate and sustain calcium oscillatory activity in zG cells equivalent to activity attained by 3 nM AngII.

We noted that spontaneous zG-TASK-LOF spiking activity was organized into bursts separated by quiescent intervals similar to AngII-evoked activity previously described in WT zG cells.39 To compare spontaneous and AngII-evoked bursts, we first assessed burst structure. An inter-calcium spike interval histogram revealed 2 populations of calcium spike intervals (Figure S2), as was observed for WT activity.39 Fitting the histogram to the sum of a Gaussian and an exponential function yielded a threshold value that was used to objectively identify intraburst intervals that segregated three or more individual calcium spikes into distinct bursts. The identification of discrete bursts of calcium spikes enabled the analysis of zG cell burst properties (eg, duration, spike frequency, number). Neither the mean duration of individual bursts within a slice (Figure 2A and 2B) nor the mean frequency of calcium spikes within a burst (intraburst frequency, Figure 2C and 2D) differed between spontaneous bursts generated in TASK-LOF zG cells and AngII-evoked bursts in WT zG cells. Notably, these properties in WT slices also remain invariant across various doses of AngII as reported previously.39 Because AngII-evoked activity increases with time, and spontaneous activity is time invariant, we compared the degree of bursting in both the early (1.5–5.0 minutes) and late phases (5–10 minutes) of the recording period. During the early phase of the recording period, the mean number of spontaneous bursts observed in zG-TASK-LOF slices (14.5±0.4) greatly exceeded that in WT slices evoked by AngIl (7.5±0.3; Figure S3A and S2B). By contrast, during the late phase of the recording period, when the level of Angll-evoked activity in WT slices achieves a steady-state, the degree of bursting between genotypes was indistinguishable (Figure 2E and 2F). Therefore, spontaneous bursts evoked by zG-TASK-LOF are highly stereotypic and phenocopy AngII-evoked bursts observed in WT slices, with comparable degrees of calcium activity.

Next, we evaluated if the spontaneous calcium activity produced by zG-TASK-LOF cells is sensitive to AngII application (ie, autonomous activity). Stimulation with AngII over a large range of doses (50 pM to 3 μM) failed to alter the burst activity of zG-TASK-LOF cells. The mean number of bursts per zG cell in either the early (Figure S3A and S3B) or late phase of the recording period (Figure 2E and 2F) remained constant, indicating that spontaneous bursting activity produced by zG-TASK-LOF cells is unresponsive to AngII.

An inherent short-coming of gene deletion approaches used to interrogate biological processes, whether at a systems or cellular level, is the inability to draw conclusions that exclude unintended effects of gene editing. To eliminate potential secondary effects produced by TASK deletion, we determined if acute pharmacological inhibition of TASK channels could replicate RAS-independent calcium activity in WT mice. Pretreatment of WT adrenal slices (10 minutes) with a combination of TASK-1 channel (A1899, 200 nM, IC50 35 nmol/L)40 and TASK-3 channel (PK-THPP, 200 nM, IC50 35 nM)41 inhibitors evoked calcium oscillations that were indistinguishable from the spontaneous activity of zG-TASK-LOF slices and steady-state hormone-evoked activity (3 nM AngII) in WT slices. TASK inhibitor-evoked activity was time-invariant (Figure 3A and 3B) and organized into bursts (Figure 3C and 3D) with features typical of spontaneous and hormone-evoked bursts in TASK-LOF and WT slices, respectively (Figure 3E and 3F).

Employing a functional clustering algorithm (FCA),42 we previously observed that zG cells residing in rosettes produce temporally related calcium oscillations, suggesting that the rosette serves as a functional unit within the zG layer.39 Yet, it remained unresolved whether the rosette assembly itself was the basis for correlated activity, or whether additional AT1R-generated signals were required to dynamically coordinate asynchronous cellular oscillatory behavior. We gained insight into these alternatives by applying the FCA to spontaneous spike trains evoked by zG-TASK-LOF. The unbiased FCA-assignment of zG cells into functional clusters indeed revealed groups with distinctive spontaneous activity patterns (Figure 4A, clusters are color-coded for clarity), seemingly corresponding to rosette-like anatomic groupings of zG cells (Figure 4B). Figure 4C presents the corresponding raster plot of calcium activity for each cell. Thus, AT1R activation is not required to produce correlated activity among zG cells.

Next, we aimed to impartially determine if members of a zG cell functional cluster identified in zG-TASK-LOF slices are indeed located within the same rosette. Accordingly, we determined the anatomic location of zG cells within a functional cluster by first identifying the X-Y coordinates of each cell within the slice. From these coordinates, we calculated the centroid distances between all identifiable zG cells within the slice and then sorted and compared pairwise distances between cell-pairs that were assigned to the same activity cluster (ie, Within Clusters) or different activity clusters (ie, Between Clusters). Figure 4D shows all pairwise-distances, whereas Figure 4E shows the corresponding means from each experiment. Cells within functional clusters are in close proximity to each other, in contrast to cells in different functional clusters. Notably, the mean pairwise-distance of Within Clusters pairs (9.8±1.5 microns) approximates the distance between the centers of 2 neighboring zG cells within a rosette. Comparable distances are derived from WT cell activity evoked either by TASK inhibition or by 3 nM AngII (Figure 4F). Thus, TASK-LOF-evoked oscillatory activity generated within the rosette assembly appears sufficient to produce activity-correlated networks of zG cells that do not require additional AT1R generated signals.

To corroborate our findings that the zG layer in TASK-LOF slices is comprised of rosette-based functional networks of zG cells, we analyzed activity rasters using a phase analysis algorithm that evaluates the temporal relationships between 2 spiking zG cells. Unlike the FCA, an algorithm that evaluates calcium spiking synchronicity between cell-pairs, phase analysis can identify calcium spiking patterns that are fixed in time but not necessarily synchronous. That is, the spiking activity of 2 coordinated and phase-locked cells can be either synchronous (in phase; 0° phase-difference) or asynchronous (out of phase; 1 to 359° phase-difference). Regardless of the degree of synchrony between cell-pairs, phase relationships between spike trains that remain invariant across time are indicative of functionally coupled cell-pairs, and the SD of their phase relationships serves as a measure of invariance.

A matrix plot of color-coded standard deviations across all zG cell-pairs (ie, cell1 versus cell1: synchronous, invariant, blue; cell1 versus all other cells: asynchronous, with varying degrees of variance, blue to red) arranged according to rosette membership provides a visual map of the extent of phase-locked activity among zG-TASK-LOF cells (Figure 5A). Within the same rosette (circumscribed by black boxes) zG-TASK-LOF cell-pairs produced more invariant phase-locked behavior (blue/green hues, smaller SD), relative to zG cell-pairs located in different rosettes (red/yellow hues, larger SD). As with AngII-evoked WT activity,39 phase analysis of spontaneous, zG-TASK-LOF calcium spikes revealed highly coupled activity among cells within a rosette, in contrast to cells located in different rosettes wherein oscillatory patterns were distinct, uncoupled and divergent with time.

In addition, a comparison of the representative matrix plots (Figure 5A and 5B) suggests that the extent of phase-locked activity observed in zG-TASK-LOF and AngII-evoked WT slices were remarkably similar. To objectively evaluate phase-locking equivalency between these 2 conditions, we plotted the cumulative distribution of phase-difference standard deviations derived from cell-pairs residing in the same (ie, Within) or different (Between) rosettes, under different stimulation paradigms. All Within-Rosette phase-difference SD distributions markedly diverged from Between-Rosette distributions. Within-Rosette activity distributions measured in zG-TASK-LOF or AngII-evoked WT slices were super-imposable (Figure 5C). Notably, coordinated zG-TASK-LOF cell activity also remained unresponsive to AngII modulation (50 pM to 3 μM). Calculation of the respective SD of the cell-pair phase-difference means from each experiment yielded similar conclusions (Figure 5D), and all findings were replicated by the TASK channel inhibitor (Figure S4). Thus, by 2 independent analyses, FCA and phase analysis, TASK-LOF and its sequelae, produced by either genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition, is sufficient to evoke and couple calcium oscillatory activity of zG cells within a rosette and render the network activity AngII-unresponsive.

AngII-unresponsive hyperaldosteronism was demonstrated in early seminal studies in patients with PA. In patients with aldosterone-producing adenoma, plasma aldosterone was greatly elevated at baseline and AngII infusion at pressor doses failed to stimulate production, in contrast to normal subjects in whom a time- and dose-dependent increase in plasma aldosterone was elicited.43,44 The extension of these findings in subsequent studies has revealed a broader range of responses within PA that embraces a varied mixture of 2 response components: AngII-hypersensitivity (responsive) and AngII-independence (unresponsive), the latter of which increases with disease severity.3,45–48 Because calcium signaling in zG-TASK-LOF cells is unresponsive to AngII, we queried whether aldosterone production from zG-TASK-LOF slices may also be AngII-unresponsive. Following a period of adrenal slice stabilization, aldosterone secreted into the media was measured at baseline (30 minutes) and then 30 minutes after stimulation with a single dose of AngII (50 pM to 3 nM). As anticipated, production from zG-TASK-LOF slices at baseline was ~3-fold greater than WT (Figure 6A) and did not significantly differ from WT slices incubated with TASK inhibitor (122±14 versus 104±5 pg/mL per hour). To control for unequal zG cell numbers across slices, we normalized the AngII-evoked aldosterone response of each slice to its baseline level of production and then compared fold-responses to AngII across genotypes. Comparison of the mean fold-values shows that in WT slices, AngII dose-dependently increases aldosterone production ≈3-fold with a threshold value of > 50 pM (Figure 6B). By contrast, AngII failed to further stimulate aldosterone production from zG-TASK-LOF. Therefore, in the absence of contributions from extra-adrenal dysfunction, loss of TASK activity in mouse zG cells assembled in rosettes is sufficient to drive aldosterone overproduction that is AngII-unresponsive.

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate that zG cells studied in their native rosette assembly can be provoked to produce robust calcium oscillations and aldosterone overproduction in the absence of secretagogues, resulting solely from TASK channel dysfunction. First, we show that either tissue-specific TASK-1/−3-LOF, or their pharmacological inhibition, is sufficient to evoke bursts of calcium spikes with stereotypic burst properties (ie, burst duration, spike intraburst frequency) indistinguishable from those evoked by AngII. In WT rosettes, Angll dose-dependently stimulates zG cells by increasing the number of calcium bursts.39 By contrast, the number of bursts produced by rosettes of zG cells with dysfunctional TASK channels was AngII-dose invariant, indicating calcium signaling autonomy evoked by TASK-LOF. Next, we measured acute aldosterone secretion in adrenal slices to determine if the observed calcium signaling autonomy evoked comparable changes in steroidogenesis in native tissue. TASK-LOF (by genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition) produced more aldosterone than untreated WT slices, and TASK-LOF imparted an AngII-insensitivity to aldosterone production. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that TASK channel dysfunction, in the absence of extra-adrenal contributions to zG cell function, is sufficient to drive autonomous, AngII-unresponsive calcium activity and aldosterone production in native, fully differentiated tissue. Although our studies were not designed to evaluate the participation of transcriptional and translational events in the mechanism by which channel dysfunction produces signaling and steroidogenic autonomy, the recapitulation of the genetic phenotype by acute pharmacological channel inhibition makes these possibilities unlikely.

These studies support and extend findings previously reported by other laboratories. The germ-line deletion of TASK-3 channels produces a 25mV depolarization of zG cells and generates spontaneous zG cell calcium oscillatory activity in many rosettes.31 Yet, in contrast to our findings reported here, some TASK-3-LOF zG cells in rosettes maintain responsiveness to AngII (normal, or weaker and transient responses). Similarly, rosettes assembled with zG cells expressing gain-of-function ClC-2 channels produced by germ-line genetic engineering display diverse behaviors. Clcn2R180Q/+ mutations generate zG cells that are conditional oscillators and hypersensitive to AngII,21 whereas constitutively open channels (Clcn2op/op) evoke extreme depolarization (−40 mV resting voltage), spontaneous oscillatory activity, and unresponsiveness to 1 nM AngII.20 Taken together, it is intriguing to speculate that the degree of depolarization produced by either TASK-LOF or ClC-2-GOF determines a response continuum from zG cells that produces heightened sensitivity and then autonomy and unresponsiveness to AngII with escalating depolarization.

Within PA, a response continuum of aldosterone production from hypersensitivity to autonomy is also evident.3 AngII infusion has been shown to elicit amplified steroidogenic responses in patients with bilateral adrenal hyperplasia compared with patients with normal-renin hypertension. However, patients harboring aldosterone-producing adenomas are either responsive or unresponsive to AngII infusion.46–48 This dichotomy of responses is currently under intense investigation and has been suggested to reflect the cellular composition of the tumor,46,49 the mutational status of aldosterone driver genes,50 and/or ectopic/heterogeneous receptor expression.51–53 In vivo zG-TASK-LOF mice display a mild-hyperaldosteronism with a component of aldosterone autonomy. In this disease model, AT1R antagonism or high sodium dietary intake reduces aldosterone production yet neither treatment normalizes elevated urinary aldosterone excretion to that of WT mice.33 In fact, each treatment magnifies the differences in aldosterone production between WT and zG-TASK-LOF genotypes, revealing a larger RAS-uncoupled component of aldosterone output that drives the elevation in blood pressure. Therefore, we were surprised to find full RAS uncoupling of calcium signaling and complete steroidogenic autonomy of zG-TASK-LOF rosettes in vitro.

How then can partial autonomy arise in vivo? While this question remains untested, it is intriguing to again consider membrane voltage as a possible modifier. In a layer marked by zG cell turnover and continuous zG to zona fasciculata cell transdifferentiation,54 zG cells are likely heterogeneous. When exposed to the interstitial milieu that contains a variety of peptides that regulate zG function (see Lenzini et al51 for review), the exact expression pattern of receptors and conductances would be expected to differentially alter zG cell resting membrane voltage and consequently evoke a diversity of responses to AngII, from hypersenstivity to autonomous/unresponsive. Accordingly, it is formally possible that in the complex environment of the adrenal interstitium, a robust cell-autonomous hyperaldosteronism phenotype of TASK-LOF may be partially offset by circulating factors that are absent in vitro.

Finally, it is noteworthy that spontaneous or inhibitor-evoked zG cell oscillations revealed rosette-based activity-groupings, similar to AngII-induced rosette-based activity in WT mice.39 Acute inhibition of TASK channels evokes calcium oscillatory activity and the activation of the calcium messenger system. By contrast, AT1R stimulates many signaling pathways through its direct interaction with heterotrimeric G-proteins (Gi, Gq, G12/13) and other proteins not part of the G-protein family (eg, calmodulin, JAK2, PLC-g1, etc)56. Surprisingly, our data indicate that activation of the calcium messenger system is sufficient to generate rosette-based networks of interacting zG cells. Whether the calcium dependence of coordination depends on the strength of cadherin and/or cytoskeletal interactions and whether activity-coupling functions as an amplification mechanism in the zG-layer, as it does in many systems, awaits investigation.

Our studies provide proof-of-principle that intrinsic channel dysfunction of a dominant resting-state conductance within native zG rosettes can induce robust, autonomous calcium and steroidogenic activities, independent of extra-adrenal amplification. In rosette assemblies, the electrical excitability of zG cells enables large voltage excursions that recruit the participation of many conductances, and imparts functional plasticity to the network. As such, genetic perturbations of resting state-conductances that produce a phenotype in a rosette must result in a depolarization that cannot be offset by compensating conductances and correlated network activity. To demonstrate this principle in the mouse, we chose to disrupt dominant resting state conductances in mouse zG cells, TASK-1 and TASK-3 channels. Notably, the KCNK3 gene (TASK1) is also one of the most abundantly expressed genes in the human adrenal cortex (KCNK3 > KCNK2 > KCNK5 > KCNK9),15,57–60 and KCNK3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been associated with hypertension and aldosterone production16,61,62 across large multiethnic human cohorts. Yet, in aldosterone producing-adenomas and micronodules, pathogenic mutations most frequently occur in the KCNJ5 and CACNA1D genes, respectively. Thus, although it is doubtful that TASK-3 dysfunction contributes to PA in humans, it remains to be determined if genetic variation in the KCNK3 gene could potentially contribute to autonomous aldosterone production in normotensive or mildly hypertensive younger patient cohorts, when CP11B2 is expressed normally in zG-layer rosettes.

PERSPECTIVES

Recent evidence suggests that RAS-independent aldosterone production is highly prevalent and contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular and renal disease.3 Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are partially effective at mitigating the pathological consequences of aldosterone overproduction, but they are not as effective as adrenalectomy.63 Genetic variation in ion channels that disrupt intracellular calcium homeostasis and strongly associate with RAS-independent aldosterone production have been identified, introducing the exciting potential for novel channel-targeted pharmacological therapies. However, the extent to which an inherent alteration in an ion channel conductance within a zG cell rosette assembly can evoke autonomous aldosterone production independent of extra-adrenal circulating factors or additional genetic alterations, was previously untested. Here, we used a background potassium channel (TASK-1/−3) loss-of-function model to study in vitro steroidogenic and calcium activities of zG cells natively assembled. We demonstrate that within native adrenal slices, both genetic and pharmacological disruption of TASK channels elicits spontaneous, RAS-independent calcium oscillations that organize into rosette-based electrical networks driving autonomous aldosterone production. Thus, we provide proof-of-principle that channel dysfunction of a dominant resting-state conductance alone, in the context of a rosette, can produce aldosterone autonomy. These data support and extend the targeting of ion channels as a pharmacological strategy to restore calcium homeostasis and mitigate PA.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND RELEVANCE.

What Is New?

Dysfunction of a dominant resting-state conductance by zG-specific genetic deletion or acute pharmacological blockade is sufficient to drive robust renin-angiotensin system-independent aldosterone production from zG cells within native rosette assemblies, and does not require amplification by extra-adrenal factors.

What Is Relevant?

Pathogenic ion channel mutations in PA are well-documented. Yet, whether channel dysfunction in zG-layer rosettes can be an ample source of autonomous aldosterone production remained untested.

Clinical/Pathophysiological Implications?

Renin-angiotensin system-independent hyperaldosteronism is now recognized as a prevalent risk factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular and kidney disease; yet, current nonsurgical treatment strategies are limited. These findings support the targeting of ion channels as a pharmacological strategy to restore calcium homeostasis and correct autonomous hyperaldosteronism in RAS-independent hyperaldosteronism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert M. Carey for his very helpful discussions. Graphical abstract created with www.BioRender.com.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants to P.Q. Barrett (HL138241 and HL089717) and to D.T. Breault (DK123694).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Angll

angiotensin II

- AT1R

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- FCA

functional clustering algorithm

- LOF

loss-of-function

- PA

primary aldosteronism

- RAS

renin-angiotensin system

- TASK

TWIK-related acid-sensitive potassium channel

- zG

zona glomerulosa

Footnotes

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19557.

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Mulatero P, Monticone S, Deinum J, Amar L, Prejbisz A, Zennaro MC, Beuschlein F, Rossi GP, Nishikawa T, Morganti A, et al. Genetics, prevalence, screening and confirmation of primary aldosteronism: a position statement and consensus of the Working Group on Endocrine Hypertension of The European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2020;38:1919–1928. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kmieć P, Sworczak K. Autonomous aldosterone secretion as a subclinical form of primary aldosteronism: pathogenesis and clinical significance. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022;130:7–16. doi: 10.1055/a-1556-7784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaidya A, Carey RM. Evolution of the primary aldosteronism syndrome: updating the approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgaa606. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JM, Siddiqui M, Calhoun DA, Carey RM, Hopkins PN, Williams GH, Vaidya A. The unrecognized prevalence of primary aldosteronism: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:10–20. doi: 10.7326/M20-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohn JN, Colucci W. Cardiovascular effects of aldosterone and post-acute myocardial infarction pathophysiology. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(10A):4F–12F. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milliez P, Girerd X, Plouin PF, Blacher J, Safar ME, Mourad JJ. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno Y, Sone M, Inagaki N, Yamasaki T, Ogawa O, Takeda Y, Kurihara I, Itoh H, Umakoshi H, Tsuiki M, et al. ; Nagahama Study; JPAS Study Group. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in primary aldosteronism: a multicenter study in Japan. Hypertension. 2018;71:530–537. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiffrin EL. Effects of aldosterone on the vasculature. Hypertension. 2006;47:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000201443.63240.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaidya A, Mulatero P, Baudrand R, Adler GK. The expanding spectrum of primary aldosteronism: implications for diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Endocr Rev. 2018;39:1057–1088. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaidya A, Brown JM, Carey RM, Siddiqui M, Williams GH. The unrecognized prevalence of primary aldosteronism. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:683. doi: 10.7326/L20-1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monticone S, Burrello J, Tizzani D, Bertello C, Viola A, Buffolo F, Gabetti L, Mengozzi G, Williams TA, Rabbia F, et al. Prevalence and clinical manifestations of primary aldosteronism encountered in primary care practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1811–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funder JW. Aldosterone in advancing age: don’t shoot the messenger. Circulation. 2017;136:356–358. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, Zhou J, Clausen MV, Lieb A, Maniero C, Garg S, Bochukova EG, Zhao W, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1055–1060. doi: 10.1038/ng.2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, Wieland T, Nielsen HN, Lichtenauer UD, Penton D, Schack VR, Amar L, Fischer E, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:440–4, 444e1. doi: 10.1038/ng.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, Björklund P, Zhao B, Nelson-Williams C, Ji W, Cho Y, Patel A, Men CJ, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–772. doi: 10.1126/science.1198785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manichaikul A, Rich SS, Allison MA, Guagliardo NA, Bayliss DA, Carey RM, Barrett PQ. KCNK3 variants are associated with hyperaldosteronism and hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:356–364. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholl UI, Goh G, Stölting G, de Oliveira RC, Choi M, Overton JD, Fonseca AL, Korah R, Starker LF, Kunstman JW, et al. Somatic and germ-line CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1050–1054. doi: 10.1038/ng.2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zennaro MC, Boulkroun S, Fernandes-Rosa F. An update on novel mechanisms of primary aldosteronism. J Endocrinol. 2015;224:R63–R77. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes-Rosa FL, Daniil G, Orozco IJ, Göppner C, El Zein R, Jain V, Boulkroun S, Jeunemaitre X, Amar L, Lefebvre H, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in the CLCN2 chloride channel gene causes primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2018;50:355–361. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0053-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Göppner C, Orozco IJ, Hoegg-Beiler MB, Soria AH, Hübner CA, Fernandes-Rosa FL, Boulkroun S, Zennaro MC, Jentsch TJ. Pathogenesis of hypertension in a mouse model for human CLCN2 related hyperaldosteronism. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4678. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12113-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schewe J, Seidel E, Forslund S, Marko L, Peters J, Muller DN, Fahlke C, Stölting G, Scholl U. Elevated aldosterone and blood pressure in a mouse model of familial hyperaldosteronism with ClC-2 mutation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5155. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13033-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenzini L, Rossi GP. The molecular basis of primary aldosteronism: from chimeric gene to channelopathy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;21:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenzini L, Caroccia B, Campos AG, Fassina A, Belloni AS, Seccia TM, Kuppusamy M, Ferraro S, Skander G, Bader M, et al. Lower expression of the TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel 2 (TASK-2) gene is a hallmark of aldosterone-producing adenoma causing human primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E674–E682. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenzini L, Prisco S, Gallina M, Kuppusamy M, Rossi GP. Mutations of the twik-related acid-sensitive K+ channel 2 promoter in human primary aldosteronism. Endocrinology. 2018;159:1352–1359. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-03119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett PQ, Guagliardo NA, Bayliss DA. Ion channel function and electrical excitability in the zona glomerulosa: a network perspective on aldosterone regulation. Annu Rev Physiol. 2021;83:451–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030220-113038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aragao-Santiago L, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Mulatero P, Spyroglou A, Reincke M, Williams TA. Mouse models of primary aldosteronism: from physiology to pathophysiology. Endocrinology. 2017;158:4129–4138. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes-Rosa FL, Boulkroun S, Zennaro MC. Genetic and genomic mechanisms of primary aldosteronism. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26:819–832. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidel E, Schewe J, Zhang J, Dinh HA, Forslund SK, Markó L, Hellmig N, Peters J, Muller DN, Lifton RP, et al. Enhanced Ca2+ signaling, mild primary aldosteronism, and hypertension in a familial hyperaldosteronism mouse model (Cacna1h M1560V/+). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2014876118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014876118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies LA, Hu C, Guagliardo NA, Sen N, Chen X, Talley EM, Carey RM, Bayliss DA, Barrett PQ. TASK channel deletion in mice causes primary hyperaldosteronism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2203–2208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guagliardo NA, Yao J, Hu C, Schertz EM, Tyson DA, Carey RM, Bayliss DA, Barrett PQ. TASK-3 channel deletion in mice recapitulates low-renin essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penton D, Bandulik S, Schweda F, Haubs S, Tauber P, Reichold M, Cong LD, El Wakil A, Budde T, Lesage F, et al. Task3 potassium channel gene invalidation causes low renin and salt-sensitive arterial hypertension. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4740–4748. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heitzmann D, Derand R, Jungbauer S, Bandulik S, Sterner C, Schweda F, El Wakil A, Lalli E, Guy N, Mengual R, et al. Invalidation of TASK1 potassium channels disrupts adrenal gland zonation and mineralocorticoid homeostasis. EMBO J. 2008;27:179–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guagliardo NA, Yao J, Stipes EJ, Cechova S, Le TH, Bayliss DA, Breault DT, Barrett PQ. Adrenal Tissue-Specific Deletion of TASK Channels Causes Aldosterone-Driven Angiotensin II-Independent Hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73:407–414. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao CX, Yang XC, Gao YX, Zhuang M, Wang KP, Sun LJ, Wang XS. Expression of aldosterone synthase and adrenocorticotropic hormone receptor in adrenal incidentalomas from normotensive and hypertensive patients: distinguishing subclinical or atypical primary aldosteronism from adrenal incidentaloma. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:1396–1402. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Ghorayeb N, Bourdeau I, Lacroix A. Role of ACTH and other hormones in the regulation of aldosterone production in primary aldosteronism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2016;7:72. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2016.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leng S, Carlone DL, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ, Breault DT. Rosette morphology in zona glomerulosa formation and function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;530:111287. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leng S, Pignatti E, Khetani RS, Shah MS, Xu S, Miao J, Taketo MM, Beuschlein F, Barrett PQ, Carlone DL, et al. β-Catenin and FGFR2 regulate postnatal rosette-based adrenocortical morphogenesis. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1680. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15332-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu C, Rusin CG, Tan Z, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ. Zona glomerulosa cells of the mouse adrenal cortex are intrinsic electrical oscillators. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2046–2053. doi: 10.1172/JCI61996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guagliardo NA, Klein PM, Gancayco CA, Lu A, Leng S, Makarem RR, Cho C, Rusin CG, Breault DT, Barrett PQ, et al. Angiotensin II induces coordinated calcium bursts in aldosterone-producing adrenal rosettes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1679. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15408-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Streit AK, Netter MF, Kempf F, Walecki M, Rinné S, Bollepalli MK, Preisig-Müller R, Renigunta V, Daut J, Baukrowitz T, et al. A specific two-pore domain potassium channel blocker defines the structure of the TASK-1 open pore. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13977–13984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coburn CA, Luo Y, Cui M, Wang J, Soll R, Dong J, Hu B, Lyon MA, Santarelli VP, Kraus RL, et al. Discovery of a pharmacologically active antagonist of the two-pore-domain potassium channel K2P9.1 (TASK-3). ChemMedChem. 2012;7:123–133. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldt S, Waddell J, Hetrick VL, Berke JD, Zochowski M. Functional clustering algorithm for the analysis of dynamic network data. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2009;79(5 Pt 2):056104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.056104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horton R Stimulation and suppression of aldosterone in plasma of normal man and in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:1230–1236. doi: 10.1172/JCI106087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wisgerhof M, Brown RD, Hogan MJ, Carpenter PC, Edis AJ. The plasma aldosterone response to angiotensin II infusion in aldosterone-producing adenoma and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52:195–198. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-2-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baudrand R, Guarda FJ, Fardella C, Hundemer G, Brown J, Williams G, Vaidya A. Continuum of Renin-Independent Aldosteronism in Normotension. Hypertension. 2017;69:950–956. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tunny TJ, Gordon RD, Klemm SA, Cohn D. Histological and biochemical distinctiveness of atypical aldosterone-producing adenomas responsive to upright posture and angiotensin. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1991;34:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1991.tb00306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tunny TJ, Klemm SA, Stowasser M, Gordon RD. Angiotensin-responsive aldosterone-producing adenomas: postoperative disappearance of aldosterone response to angiotensin. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1993;20:306–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1993.tb01690.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nomura K, Toraya S, Horiba N, Ujihara M, Aiba M, Demura H. Plasma aldosterone response to upright posture and angiotensin II infusion in aldosterone-producing adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:323–327. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1619026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon RD, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Hamlet SM, Tunny TJ, Klemm SA. Angiotensin-responsive aldosterone-producing adenoma masquerades as idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA: adrenal hyperplasia) or low-renin essential hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1987;5:S103–S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo Z, Nanba K, Udager A, McWhinney BC, Ungerer JPJ, Wolley M, Thuzar M, Gordon RD, Rainey WE, Stowasser M. Biochemical, Histo-pathological, and Genetic Characterization of Posture-Responsive and Unresponsive APAs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgaa367. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenzini L, Caroccia B, Seccia TM, Rossi GP. Peptidergic G protein–coupled receptor regulation of adrenal function: bench to bedside and back. Endocr Rev. 2022. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnac011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim JS, Plaska SW, Rege J, Rainey WE, Turcu AF. Aldosterone-regulating receptors and aldosterone-driver somatic mutations. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:644382. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.644382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen YM, Wu KD, Hu-Tsai MI, Chu JS, Lai MK, Hsieh BS. Differential expression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor mRNA and aldosterone responsiveness to angiotensin in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;152:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00059-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freedman BD, Kempna PB, Carlone DL, Shah M, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Majzoub JA, Breault DT. Adrenocortical zonation results from lineage conversion of differentiated zona glomerulosa cells. Dev Cell. 2013;26:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganz MB, Nee JJ, Isales CM, Barrett PQ. Atrial natriuretic peptide enhances activity of potassium conductance in adrenal glomerulosa cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(5 Pt 1):C1357–C1365. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:953–970. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen AX, Nishimoto K, Nanba K, Rainey WE. Potassium channels related to primary aldosteronism: Expression similarities and differences between human and rat adrenals. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;417:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nogueira EF, Gerry D, Mantero F, Mariniello B, Rainey WE. The role of TASK1 in aldosterone production and its expression in normal adrenal and aldosterone-producing adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;73:22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03738.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gomez-Sanchez CE, Oki K. Minireview: potassium channels and aldosterone dysregulation: is primary aldosteronism a potassium channelopathy? Endocrinology. 2014;155:47–55. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enyeart JJ, Enyeart JA. Human adrenal glomerulosa cells express K2P and GIRK potassium channels that are inhibited by ANG II and ACTH. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;321:C158–C175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00118.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganesh SK, Chasman DI, Larson MG, Guo X, Verwoert G, Bis JC, Gu X, Smith AV, Yang ML, Zhang Y, et al. ; Global Blood Pressure Genetics Consortium. Effects of long-term averaging of quantitative blood pressure traits on the detection of genetic associations. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kato N, Loh M, Takeuchi F, Verweij N, Wang X, Zhang W, Kelly TN, Saleheen D, Lehne B, Leach IM, et al. ; BIOS-consortium; CARDIo GRAM-plusCD; LifeLines Cohort Study; InterAct Consortium. Trans-ancestry genome-wide association study identifies 12 genetic loci influencing blood pressure and implicates a role for DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1282–1293. doi: 10.1038/ng.3405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hundemer GL, Curhan GC, Yozamp N, Wang M, Vaidya A. Cardiometabolic outcomes and mortality in medically treated primary aldosteronism: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30367-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.