Abstract

Nitrosyl ruthenium complexes are promising platforms for nitric oxide (NO) and nitroxyl (HNO) release, which exert their therapeutic application. In this context, we developed two polypyridinic compounds with general formula cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(L)]n+, where L is an imidazole derivative. These species were characterized by spectroscopic and electrochemical techniques, including XANES/EXAFS experiments, and further supported by DFT calculations. Interestingly, assays using selective probes evidenced both complexes can release HNO under reaction with thiols. This finding was biologically validated by HIF-1α detection. This latter protein is related to angiogenesis and inflammation processes under hypoxic conditions, which is selectively destabilized by nitroxyl. These metal complexes also presented vasodilating properties using isolated rat aorta rings and demonstrated antioxidant properties in free radical scavenging experiments. Based on these results, the new nitrosyl ruthenium compounds showed promising characteristics as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of cardiovascular conditions such as atherosclerosis, deserving further investigation.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, nitric oxide, nitroxyl, ruthenium, metallodrugs

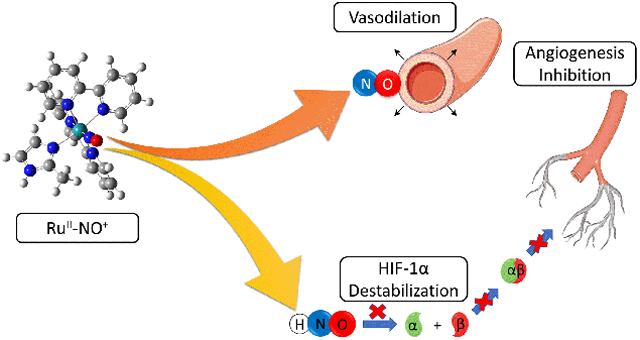

Graphical Abstract

New ruthenium nitrosyl complexes were synthetized and characterized by spectroscopic techniques, including X-ray absorption. Under selected conditions, they were able to release NO and HNO, which was demonstrated through in vitro cell assays.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a large group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels that are responsible for 31% of all global deaths, being the leading cause of death in adults worldwide.1 Among them, atherosclerosis is a relatively common condition characterized by lipid accumulation on the blood vessel walls (atheroma) due to a chronic inflammatory process.2, 3 This disease is often associated with the loss of endothelial integrity, failing in controlling vascular tonus and hypertension, which constitute significant risk factors for the occurrence of stroke and myocardial infarction. In fact, high blood pressure is the most common risk factor for CVDs and premature death globally.2, 4 Atherosclerosis development is strongly associated to endothelial dysfunction, a cascade of metabolic events that lead to the atheroma formation. Regarding the several biochemical pathways involved in this process, inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production plays a major role in the progression of the disease.5 In fact, NO is a key factor in the development of most CVDs due to its relevance in the metabolism and cell function.6, 7

Nitric oxide is an endogenous inorganic molecule that works in the signaling of several physiological and pathological pathways in mammalian organisms.8–10 It is produced by a group of enzymes denominated nitric oxide synthases, through oxidation of the amino acid arginine to L-citrulline.9 There are many processes regulated and/or influenced by NO such as platelet aggregation, vascular smooth muscle dilation, neurotransmission, inflammation and cancer development.11–14 Due to that, there is a great interest in the development of nitric oxide releasing molecules for pharmacological application.8, 15, 16 Metal-based compounds are indeed promising platforms for NO donation.8, 15 For instance, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is a nitrosyl iron coordination compound, which can fast release nitric oxide in physiological conditions (figure S1). It has been successfully used in the treatment of hypertensive emergencies, cardiac surgery and other hemodynamic applications.17 However, the side effects associated with its administration, such as cyanide intoxication, has limited its use in other applications in which NO release can be therapeutically useful. Extensive research in synthetic chemistry and materials science has been conducted to develop drugs able to replace SNP, with improved stability and better biological compatibility.8, 18, 19 Focusing on that, several nitrosyl metal-based compounds have been developed and their potential as therapeutic agents evaluated.8, 15 Among those, ruthenium complexes stand out for their unique characteristics.

The pharmacological properties of ruthenium coordination compounds have been intensively studied in the last five decades.18, 20 The first efforts in finding biologically active complexes containing this metal were focused on replacements for cisplatin, developing new cytotoxic agents. Those efforts resulted in promising compounds such as NAMI-A, KP1019, RAPTA-C and others, which were able to cause cell death through mechanisms distinct from the platinum drugs.21–23 Moreover, in the following years, several Ru-based species were synthetized exhibiting diverse therapeutic activities as antitumoral,24, 25 bactericides,26–28 anti-parasitic,29–31 anti-inflammatory32–34 agents, revealing a great potential for pharmacological application.

During the last years, our group has been working on the development of ruthenium complexes designed for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, such as arterial hypertension, stroke and heart failure.35–37 Compounds with the structure cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2L]n+, where bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine and L = imidazole, thiourea, sulfite, or a heterocyclic ligand, have shown promising results on handling those conditions, showing noticeable vasodilating and anti-inflammatory activities in vitro and in vivo models. In fact, many N-heterocyclic and sulfur-containing ligands have been successfully used in the modulation of NO releasing properties and biological reactivity of ruthenium coordination compounds.37–40 Moreover, we have demonstrated the complex cis-[Ru(bpy)2(SO3)(NO)]+ was able to release nitroxyl (HNO), a product of monoeletronic reduction of NO, expanding its pharmacological profile.41 Even though nitroxyl was first identified many years ago, its therapeutic relevance was only recognized in the beginning of 21st century. Differently from nitric oxide, HNO acts as an inotropic and lusitropic agent in the cardiovascular system,42 inhibits thiol containing enzymes such as GADPH and blocks angiogenesis through destabilization of Hypoxia Induced Factor 1 (HIF-1).15, 42 Those properties make HNO donors relevant drug candidates for the treatment of cardiovascular conditions and aggressive cancers. However, most of the HNO donors already known are organic molecules,15 which release nitroxyl under non-physiological conditions or with half-life times too short to achieve its biological target. Because of that, the development of new compounds with HNO releasing capabilities is a promising goal to be pursued in the medicinal chemistry field.

Considering the pharmacological potential of ruthenium compounds and their use as nitric oxide and nitroxyl donors, we aimed to develop novel metal complexes that can work as delivery platforms of such signaling molecules. Thus, we have selected coordination complexes with the general formula cis-[Ru(bpy)2L1L2]n+, where L1=2-methylimidazole (2MIM) or ethylenethiourea (ETU) and L2=Cl¯ or NO+ (Scheme 1), as systems for study. Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization are reported as well as the determination of their NO and HNO releasing properties followed by evaluation of their pharmacological potential.

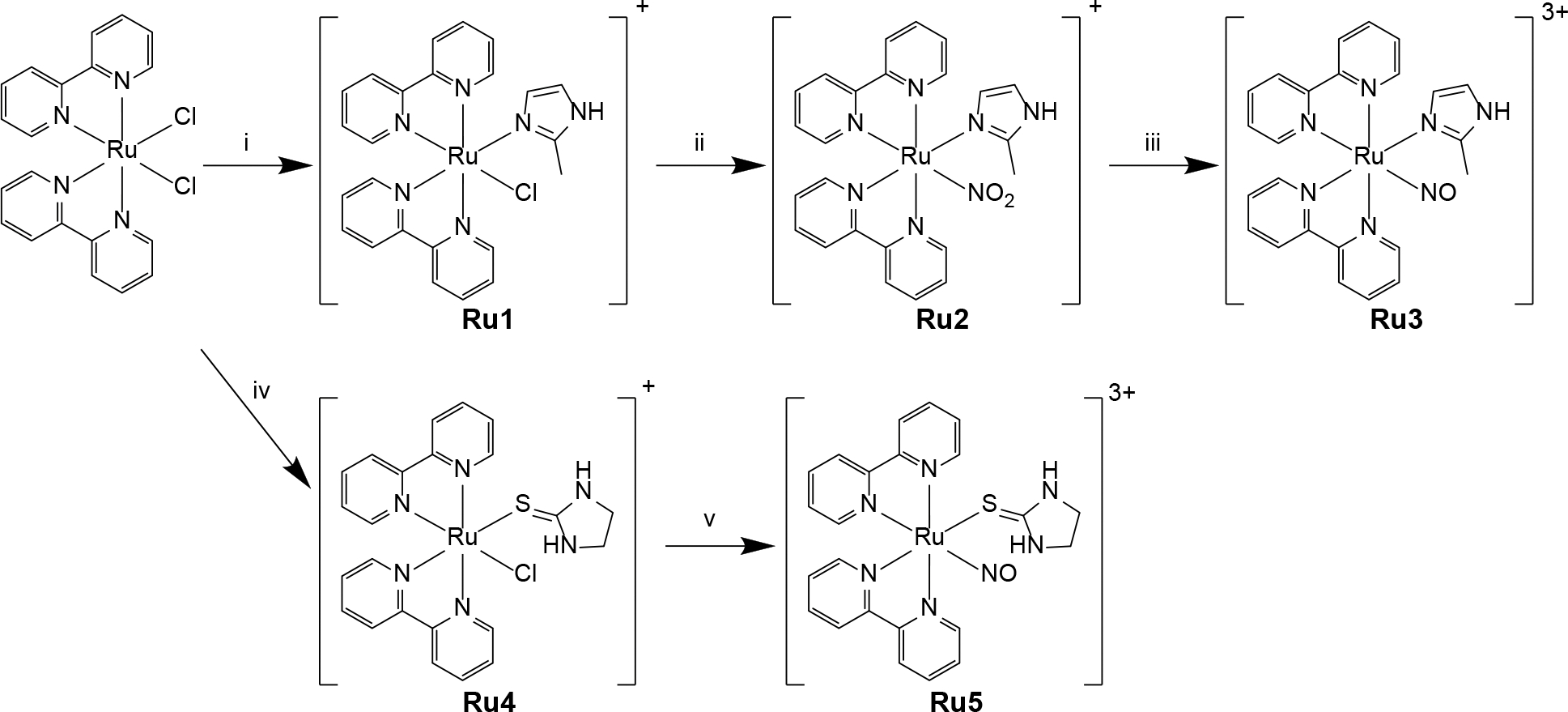

Scheme 1.

Synthetic routes for preparation of Ru3 and Ru5. i) 2MIM, EtOH reflux, 8 h; ii) NaNO2, EtOH/H2O reflux, 4 h; iii) 6 M HTFA, EtOH/H2O, 1 h; iv) ETU, EtOH/H2O reflux, 4 h; v) NO, EtOH/H2O, 3 h. EtOH = ethanol; HTFA = trifluoroacetic acid.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Complexes

The metal complexes Ru1-5 were obtained through procedures analogous to other similar compounds (see Experimental Section for details).37, 38 Nitrosyl complex Ru3 was synthetized in a three-step procedure, starting from the precursor cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2]. Substitution of one chloride anion for the ligand 2MIM generates Ru1, which was reacted with a stochiometric amount of nitrite under reflux, producing Ru2. Finally, that species was easily converted into the nitrosyl analogue with addition of trifluoroacetic acid (HTFA) in excess. The metal complex Ru5, on the other hand, was synthetized substituting a chloride moiety of cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2] (producing Ru4) and exposing that solution to a continuous stream of NO gas for the appropriate time.

These metal complexes were characterized employing spectroscopic and electrochemical techniques, supported by computational simulations. Also, elemental analysis evidenced all formulations proposed, indicating good analytical purity (> 95%). 1H NMR spectra (Figures S2A – S2E) showed signal patterns consistent with the change in symmetry upon coordination of the desired ligands as well as the retention of cis configuration in all compounds. The integral and chemical shifts values were also compatible with the proposed structures. Mass spectrometry analysis carried out in the positive mode presented peaks at m/z values (Figures S3A – S3E) related to the monovalent cations of the compounds and their respective solvolysis products, as observed for other similar species.37

Vibrational spectra for complexes Ru3 and Ru5 (Figures S4A and S4B, respectively) showed intense bands at 1940 and 1930 cm−1, respectively, which were attributed to the ν(NO) frequency. These values agreed with spectral data from analogous nitrosyl compounds containing imidazole (1944 cm−1) or thiourea (1931 cm−1) as ligands, for example.38 These findings supported the NO moiety bounded to the metal center is in fact a nitrosyl group (NO+). Besides that, several frequencies associated to aromatic C=C and C=N vibrations from the bipyridine moieties were identified between 1400 and 1600 cm−1. Two strong bands around 840 and 558 cm−1 were noticed in all metal complexes, which correlated to the stretching and deformation frequencies of the hexafluorophosphate counter-ions. DFT calculations were performed for all species and the calculated vibrational data (figures S4C and S4D) were compared to the experimental ones. Even though the theoretical spectra were simulated in the vacuum and not considering counter-ions, reasonable correlation could be observed.

Redox properties of the metal complexes were investigated by cyclic voltammetry using a glassy carbon electrode in a 0.1 M NaTFA (sodium trifluoroacetate) pH 3 solution at room temperature. In the range of potentials studied, the metal complexes Ru1 and Ru4 (Figures S5A and S5B) showed a single reversible redox process at +600 and +550 mV, respectively. This redox process is associated to the RuIII/II couple. Similar behavior was described for several polypyridinic metal complexes containing N-heterocyclic ligands.36, 37 For the nitrosyl complexes Ru3 and Ru5 (Figures S5A and S5B), their cyclic voltammograms revealed pairs of waves at 250 mV and 75 mV, respectively. These processes were associated with a NO+/0 centered redox moiety, in agreement with other similar nitrosyl ruthenium-based compounds.37, 38 Also, molecular orbital composition analysis from DFT data of Ru3 and Ru5 (figures S6B and S7B) revealed that LUMO orbitals have major contribution from the NO+ moiety, endorsing the involvement of nitrosyl group in the reduction of both complexes.

Electronic spectra for all complexes were obtained in acetonitrile. Non-nitrosyl compounds presented characteristic bands of the system cis-[RuCl(bpy)2(L)]n+ with strong absorption in the UV range around 300 nm and charge-transfer transitions in the range of 400–600 nm. The spectra of the metal complexes Ru1 and Ru4 (Figures S6A and S7A) showed bands at 521 nm and 505 nm, respectively, attributed to metal to ligand charge transfer transitions (MLCT), supported by TD-DFT calculations. On the other hand, electronic spectra for Ru3 presented bands at 299 nm and 331 nm, whereas Ru5 shows bands at 297 nm and 330 nm (Figures S6B and S7B). These poor absorption profiles are characteristic of strong π-acceptor ligands in the coordination sphere, such as nitrosyl. Theoretical data suggest those bands are associated to π-π* transitions from the bipyridine moieties, with considerable contribution from MLCT transitions.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy data analysis

X-ray-based techniques have been extensively used in the last decades for the characterization of different types of inorganic materials and coordination metal complexes.43, 44 The increasing availability of synchrotron light sources with high brightness made possible the study of structural and electronic properties until then inaccessible for heavy metal-based non-crystalline materials.45 Among the wide diversity of techniques available, X-ray absorption spectroscopy (or X-ray absorption fine structure, XAFS) is particularly useful, since it can be applied to a great number of chemical elements allowing the investigation of electronic aspects together with structural characteristics.46 In this work, ruthenium K-edge XAFS spectra were obtained in the solid state for compounds Ru1 – 5 and the retrieved information was fitted with help of data provided by theoretical calculations (DFT).

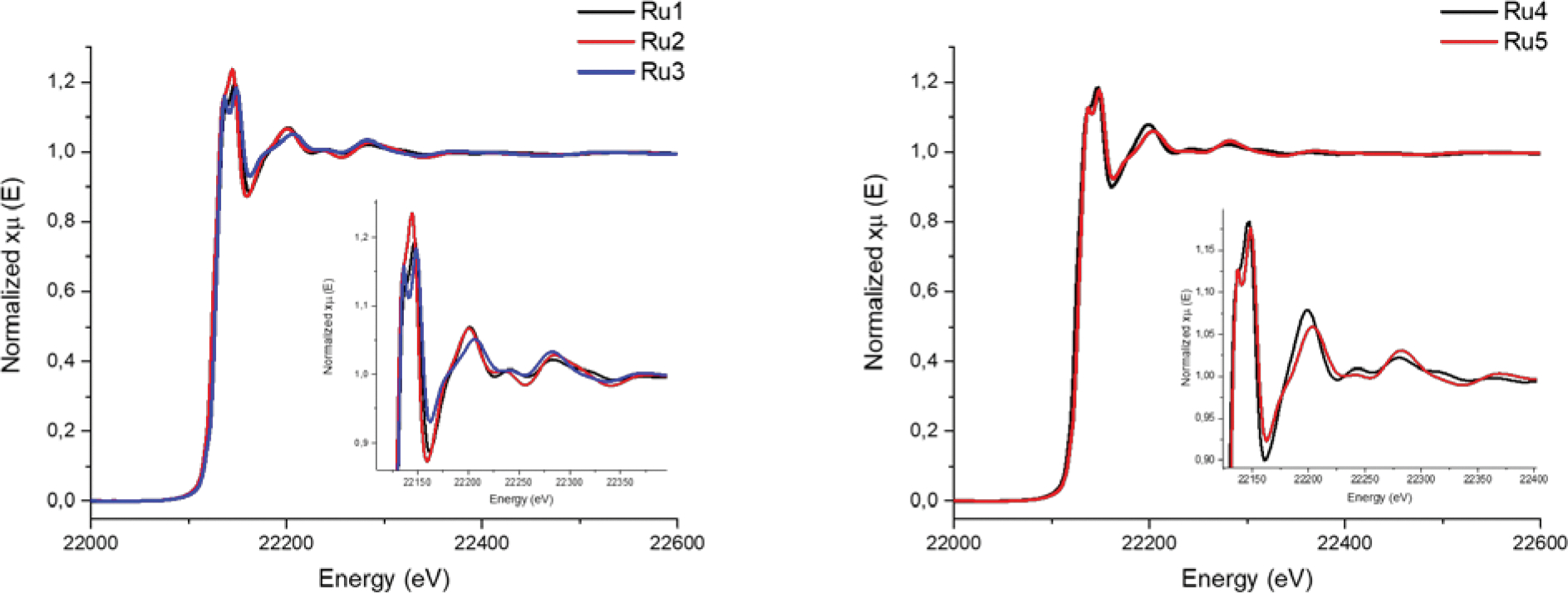

X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) can give information about geometry, oxidation state and surrounding structure of the absorber element.44 In the spectra shown in Figure 1, no pre-edges features could be identified for any of the synthetized metal complexes, evidencing there were no major change in the geometry with the substitution of the ligands. Also, compounds Ru1, Ru2 and Ru4 presented close values of edge energy (22124.7, 22123.6, 22123.7 eV, respectively), which suggests the coordinated ligands have similar effects over the ruthenium electronic density and the oxidation state (2+) was kept in all products. On the other hand, nitrosyl complexes Ru3 and Ru5 showed higher edge energy shifts (22127.5 and 22126.8 eV, respectively) when compared to their precursors, indicating the strong electron withdrawing effect of the NO+ moiety over the absorbing element.

Figure 1.

XANES and EXAFS X-ray absorption spectra of complexes Ru1–3 (left) and Ru4–5 (right). Insets show the zoomed edge region of all spectra.

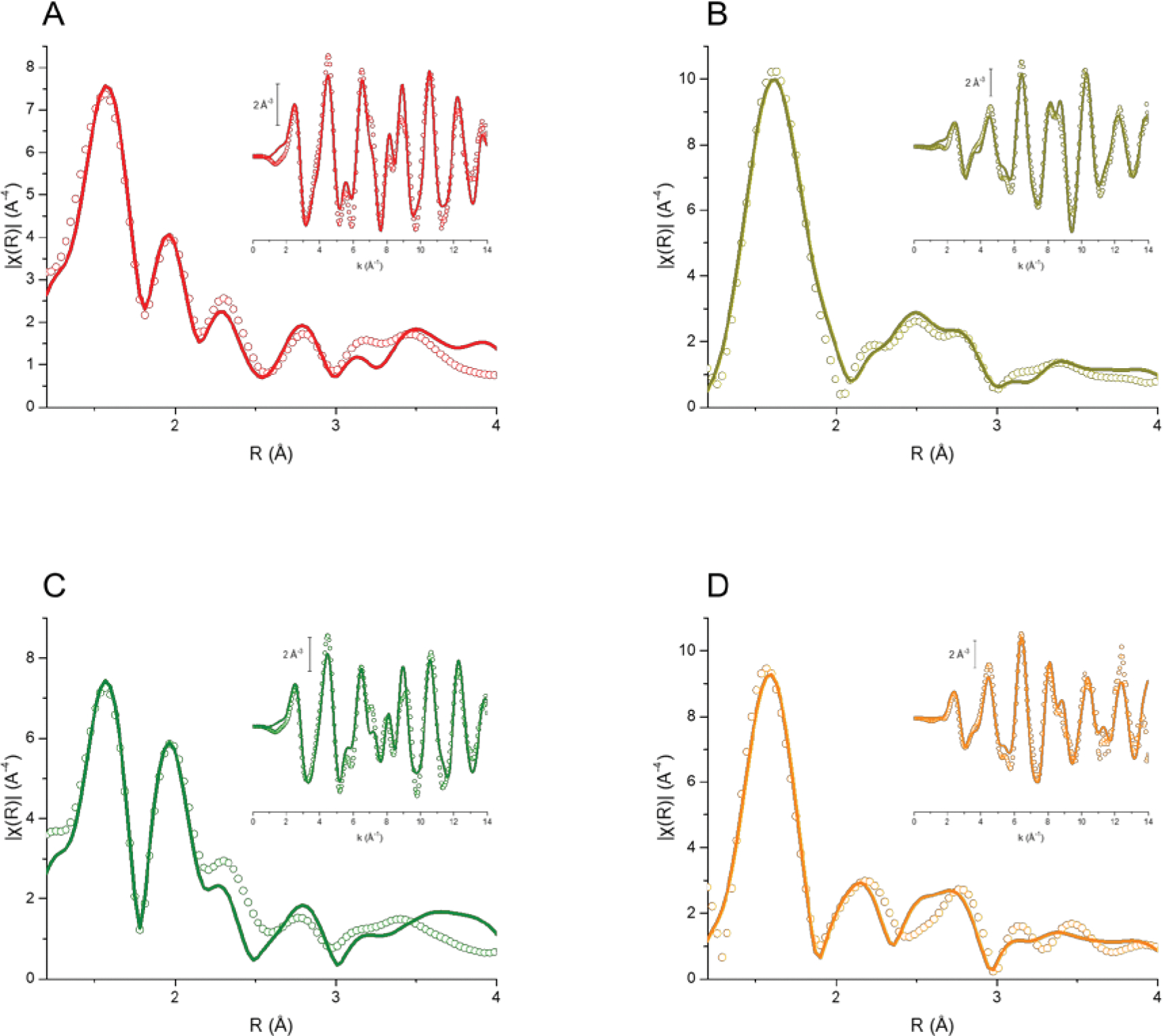

The EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure) studies provide information about coordination number, nature of the atoms around the absorber element and interatomic distances between the absorber and the other atoms.46 Figures 2 and S8 show the k3-weighted EXAFS signals and fitted curves for complexes Ru1-5 in both k and R spaces. The low r-factor obtained for all fittings suggests a good agreement between experimental and calculated values, endorsing the proposed structures. In the R-space graphs (Figure 2), it is possible to distinguish a strong peak around 1.6 Å for all species, which is related mostly to the Ru–N path. Regarding the chloride metal complexes Ru1 and Ru4, the following peak (around 2 Å) can be assigned to the Ru–Cl path. It is worth to mention, for Ru4, that signal also has considerable contribution of the Ru–S path, implying in a more intense peak. The absence of such feature in R-space spectra of Ru2, Ru3 and Ru5 confirms the substitution of this ligand for nitrite or nitrosyl. Finally, the metal complex Ru5 presents a distinguished broad signal around 2.3 Å, which can be correlated to the Ru-S path in this species.

Figure 2.

k3-weighted, phase uncorrected, Fourier transform moduli (k range 2–14 Å−1) of the experimental (circles) and best fit (solid lines) EXAFS signals for complexes Ru1 (A), Ru3 (B), Ru4 (C) and Ru5 (D). Insets: k3-weighted EXAFS signals (circles) of respective complexes and their corresponding best fits (solid lines).

DFT structural parameters were compared to EXAFS data for the first coordination shell. Selected bond lengths are described in tables 1 and S1. The found values for theoretical and experimental data are in good agreement and very close to ones determined through X-ray diffraction (XRD) in similar compounds.47, 48 For example, EXAFS spectra analysis showed that the mean length value for Ru-Nbpy bond in all complexes varied from 2.095 to 2.125 Å, while DFT simulation provided length around 2.105 Å. For the compounds Ru1 and Ru4, Ru-Cl bonds also showed excellent correlation with values differing in less than 0.1 Å. Regarding the nitrosyl complexes, the Ru-NNO+ bond lengths found through EXAFS and computational simulations presented close values around 1.75 Å, as expected for this strong π-acceptor ligand.

Table 1.

Coordination number (CN), atomic distances (R), Debye-Waller factors (σ2), fit parameters obtained from EXAFS refinement and respective DFT-simulated atomic distances (RDFT) for complexes Ru1, Ru3, Ru4 and Ru5

| Parameters | Ru1 | Ru3 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| CN | R (Å) | RDFT (Å) | σ2 (Å2) | CN | R (Å) | RDFT (Å) | σ2 (Å2) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Ru-Nbpy | 4 | 2.04(5) | 2.09(2) | 0.00205 | 4 | 2.08(1) | 2.13(4) | 0.00150 |

| Ru-N2MIM | 1 | 2.12(3) | 2.20(5) | 0.00205 | 1 | 2.12(1) | 2.16(2) | 0.00150 |

| Ru-Cl | 1 | 2.44(4) | 2.46(2) | 0.00304 | - | - | - | - |

| Ru-NNO+ | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1.75(7) | 1.79(1) | 0.00168 |

| S02 | 0.819 | 0.872 | ||||||

| ΔE (eV) | 1.12 | 1.85 | ||||||

| R-factor (%) | 3.07 | 2.29 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Parameters | Ru4 | Ru5 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| CN | R (Å) | RDFT (Å) | σ2 (Å2) | CN | R (Å) | RDFT (Å) | σ2 (Å2) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Ru-Nbpy | 4 | 2.05(8) | 2.10(2) | 0.00224 | 4 | 2.07(5) | 2.13(3) | 0.00119 |

| Ru-S | 1 | 2.43(7) | 2.51(4) | 0.00447 | 1 | 2.36(9) | 2.52(5) | 0.00151 |

| Ru-Cl | 1 | 2.41(5) | 2.49(1) | 0.00447 | - | - | - | - |

| Ru-NNO+ | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1.74(8) | 1.79(1) | 0.00484 |

| S02 | 0.860 | 0.895 | ||||||

| ΔE (eV) | 1.09 | 0.27 | ||||||

| R-factor (%) | 5.58 | 5.42 | ||||||

Partition Coefficient

The determination of the pharmacokinetic profile of a drug candidate is one of the major steps during the development of new pharmacological treatments. Lipophilicity is a key property evaluated during this process, once it is not only associated to the compatibility of the xenobiotic with biological fluids, but also indicates how well it might penetrate into the cell membrane and other barriers.49, 50 This process limits the drug absorption, distribution and excretion in the organism, which evidently impacts toxicity and efficacy of a drug candidate.51 Based on this, we measured the lipophilicity of our metal complexes using the log P model. These results are presented in Table 2, where it can be observed that all compounds are slightly hydrophilic (−1 < log P < 0), whereas Ru1 is the most lipophilic one of this small series. At the same time, a good linear correlation between partition coefficient and number of hydrogen bond donor/acceptor can be observed. According to the Lipinski’s rule of 5 states, the ideal value of log P is lower than 5 for orally available drugs,52 which matches our data, although they do not agree with the empiric ideal lipophilicity (0 < log P < 3).50 Nevertheless, it must be highlighted that several approved pharmaceuticals do not fit such parameters.53

Table 2.

Log P values, number of hydrogen bond donor and acceptor atoms for the complexes under study

| Compound | Log P | H-bond donor | H-bond acceptor |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Ru1 | −0,07 | 1 | 6 |

| Ru2 | −0,49 | 1 | 9 |

| Ru3 | −0,19 | 1 | 8 |

| Ru4 | −0,91 | 2 | 6 |

| Ru5 | −0,72 | 2 | 8 |

Nitrosyl – nitro interconversion

In aqueous solution, the nitrosyl complexes exist in an equilibrium with their respective nitro derivative, as illustrated by equation 1:

| (1) |

Since this equilibrium is dependent on the hydroxyl anion concentration, pH plays a major role controlling the equilibrium direction. Considering that our intent is to use those species as NO releasing agents in normal cytosol with pH at ca. 7.4, it is important to determine which is the predominant metal complex in such conditions.

The nitrosyl-nitro interconversion was followed by electronic spectroscopy, monitoring the absorbance changes at different pH values for the nitrosyl complexes, at the appropriate maximum wavelengths. When pH was higher than 4.0, the absorption bands at 425 nm and 440 nm were observed for aqueous solutions of Ru3 and Ru5, respectively. At higher concentrations of hydroxyl, there was a major increase in the absorbance. Then, it was determined the pH values required to achieve 50% of conversion, which were at 5.8 and 6.3 for the nitrosyl complexes containing 2MIM and ETU, respectively (Figure S9). These values indicated both compounds are majorly in the nitro form when subject to physiological conditions. However, it does not mean those species are unable to release nitric oxide in the organism. Even though the cytosol and most biological fluids are slightly basic, some organelles, like the lysosomes, have acidic contents.54 Also, cancer cells and tissues under ischemic conditions present lower pH values due to the unbalanced metabolism and poor oxygen intake.55, 56 In both situations, the nitrosyl form would be favored. Besides that, previous works demonstrated that similar compounds can react with reducing agents, such as thiols, releasing NO even when the nitro derivative is favored,37 likely due to an equilibrium shift. Indeed, we further explored this reaction in the following experiments.

Thiol-triggered NO/HNO release

Metallonitrosyl complexes have been intensively studied as platforms for controlled NO delivery.39 Chemical reduction can be used to initiate this process, which works for sodium nitroprusside (SNP), where biological thiols react with this pro-drug resulting in nitric oxide production.57, 58 In order to evaluate the nitric oxide donating properties of the compounds Ru3 and Ru5 in the presence of reducing agents, detection assays were setup employing two probes: carboxy-PTIO (cPTIO) and FeIII-myoglobin (met-Mb).

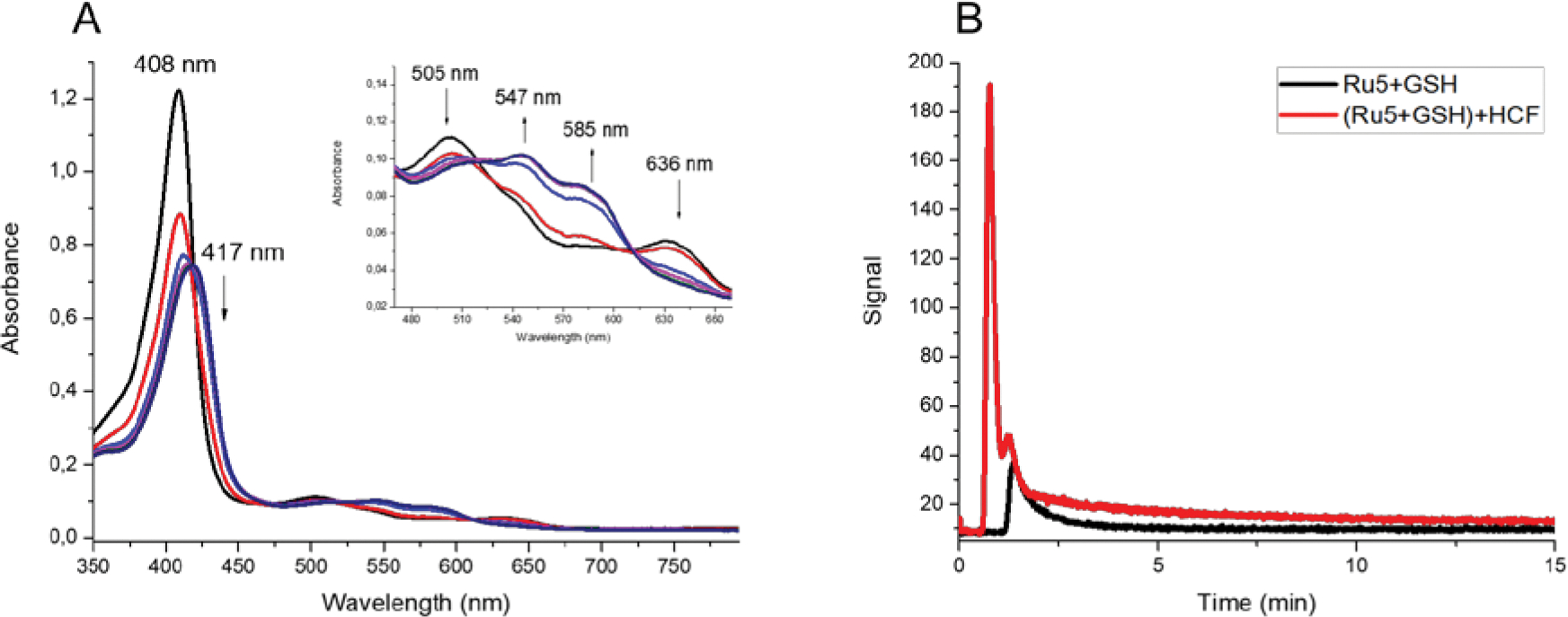

The cPTIO reagent quickly reacts with NO/HNO at stoichiometric rate leading to characteristic spectroscopic changes. In a typical experiment, the metal complexes were incubated with the probe in the appropriate assay conditions, showing no evidence of reaction. After the addition of glutathione (GSH, γ-L-Glu-L-Cys-Gly), the rapid decrease of the band in 560 nm with other changes at lower wavelengths supporting the reaction with HNO (figure S10). This spectroscopic profile suggests nitroxyl is produced after reduction of the metal complex promoted by GSH. Control experiments were performed incubating cPTIO with Angeli’s Salt, a standard HNO donor, resulting in a virtually identical spectrum (figure S11). To validate these results, a similar assay was done using met-Mb as a probe for NO/HNO detection. FeIII myoglobin reacts with HNO giving FeII-NO myoglobin, which causes significative changes in the electronic spectrum with red shift of the Soret band followed by alterations in the Q-bands. On the other hand, reaction with NO is considerably slower and the first product (FeIII-NO myoglobin) shows distinct spectroscopic features. Figures 3A and S12A present the result of the incubation of the complexes with GSH in the presence of the probe. Fast reaction can be observed, resulting in a typical spectrum consistent with the generation of FeII-NO myoglobin. These findings suggest the metal complexes can promote HNO release upon reduction. However, it is important to mention it has been demonstrated that nitrosyl ruthenium complexes are able to release both nitric oxide and nitroxyl after reaction with thiols.59–61 Mechanistic studies suggest the production of such species is conditioned by different factors, for instance pH value, nature of the reducing agent, and others.59 Considering that, we conducted other experiments to evaluate NO release directly.

Figure 3.

Measuring HNO and NO production mediated by glutathione. (A) UV-vis absorption spectra of met-Mb in the presence of Ru5 and GSH. Inset: expansion of the Q bands region; (B) NO detection curves using the chemiluminescent sensor for the reaction of Ru5 and GSH (black) and Ru5 and GSH in the presence of HCF (red).

Detection of nitric oxide released through reaction with glutathione was carried out using a chemiluminescent NO detector. These experiments were performed with higher concentration of the reducing agent (20-fold in excess) in order to promote faster reactions. Addition of the metal complexes in a solution containing GSH generated characteristic signals attributed to nitric oxide generation (Figures 3B and S12B). Once this sensor is selective for nitric oxide and being aware of the production of nitroxyl, the same procedures were employed in the presence of the oxidizing agent [FeIII(CN)]3− (HCF). This strategy works as an indirect method for nitroxyl detection, once the iron(III) complex is reduced by HNO, followed by the generation of NO. Indeed, upon addition of HCF a much more intense signal was observed, confirming that nitroxyl was in fact produced. The area below the signals were calculated, showing a two-fold increase after HCF addition. Unfortunately, quantitative measurements showed considerable deviations, probably caused by the elevated concentration of GSH that might trap those products. Nevertheless, the combined evidence strongly suggests the production of appreciable amounts of HNO, which was validated by selected biological models further described.

Cell viability

Nitric oxide plays major roles in cancer development and apoptosis triggering. Recent reports have evidenced NO donors can work activating metabolic pathways associated to tumor suppressing and chemoresistance.62, 63 Similarly, nitroxyl has been pointed as a promising cytotoxic agent, showing interesting results against aggressive tumors, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).42, 64 Because of that, nitrosyl metal complexes have been extensively studied for their potential application as anticancer drugs.18, 20 In fact, several studies have demonstrated the in vitro activity of these compounds against many different cell lines, supporting the relevance of metal-based NO donors as new platforms for cancer treatment.

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of the nitrosyl metal complexes and their respective precursors in fibroblastic lung cells (MRC5) using the Alamar Blue fluorescence assay (table S2). All compounds showed no evidence of strong cytotoxicity and both nitrosyl complexes presented IC50 values higher than 100 μmol L−1. Considering that, we decided to explore other aspects of the signaling properties of NO and their related species.

HIF-1α stabilization assay

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is an important transcription factor associated to the response to oxygen level in cells. It is composed by two subunits, denominated α and β, with different expression patterns: while HIF-1β is expressed constitutively, HIF-1α protein levels are undetectable under normoxic conditions.65 Under hypoxia, HIF-1α is stabilized, transported to the cell nucleus and dimerizes with HIF-1β originating the active HIF-1 transcription factor. This protein upregulates genes related to angiogenesis, inflammation and other major metabolic pathways.65, 66 Because of that, HIF-1α dysregulation is associated with a considerable number of diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis and pulmonary hypertension, making it a promising therapeutic target.67, 68 Besides oxygen, other signaling molecules can influence HIF-1α stabilization. Nitric oxide interacts with prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) inhibiting HIF-1α degradation process, thus leading to the expression of proteins associated to hypoxia even under normal oxygen levels. On the other hand, nitroxyl inhibits HIF-1α accumulation, disrupting free radical production and causing an antiangiogenic and antimetastatic effect in cancer cells, as already demonstrated in previous reports.64, 68 That makes HNO donors as strong candidates to pro-drugs for the treatment of pathologic conditions associated to HIF-1.

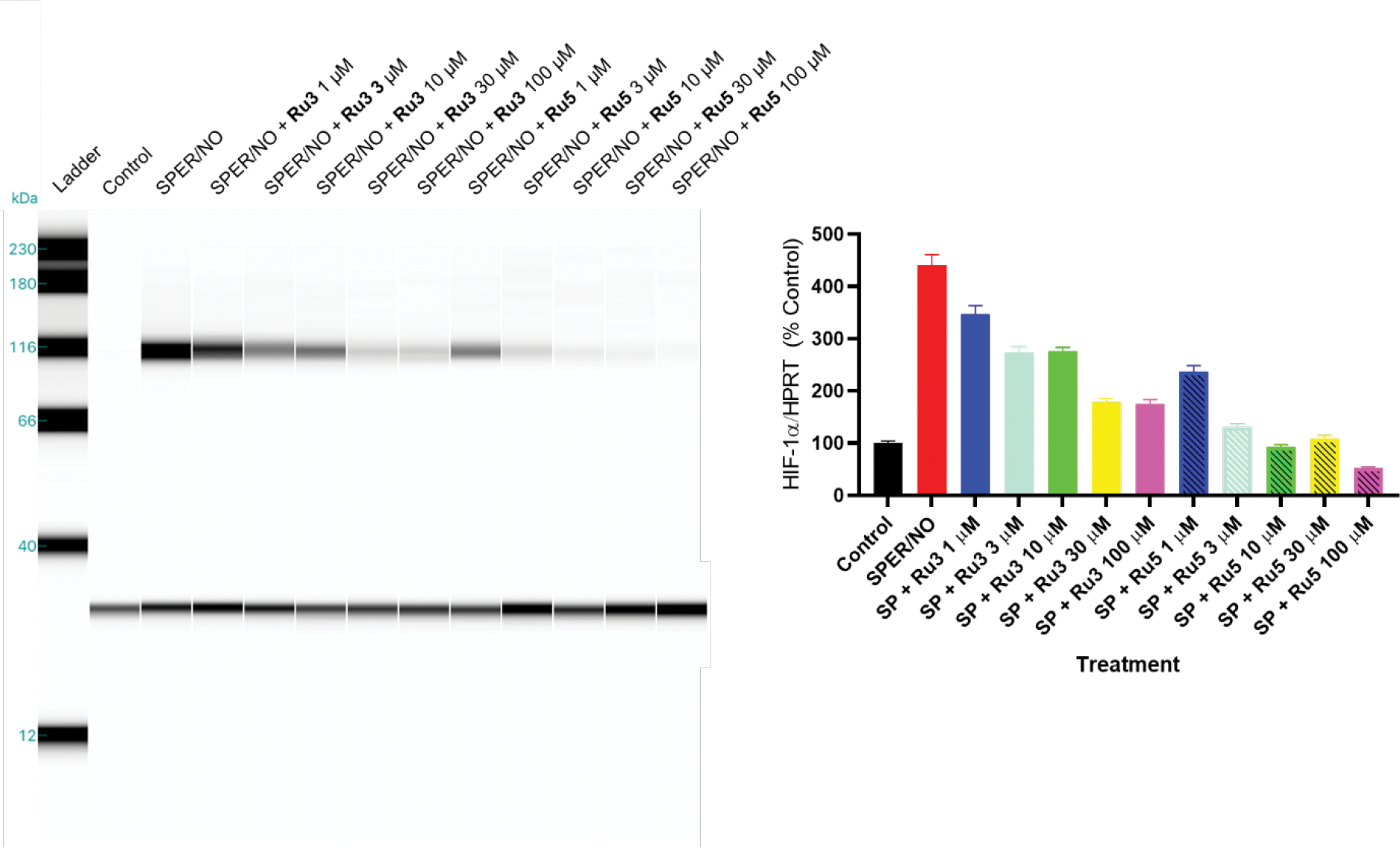

Based on that, we evaluated the activity of Ru3 and Ru5 as HNO donors in hypoxia-induced cell cultures looking at their effects in the HIF-1α stabilization. Breast cancer cells were pre-treated with the metal complexes and then exposed to the NO donor SPER/NO in order to induce HIF-1α stabilization. As shown in Figure 4, pre-treatment with our nitrosyl metal complexes significatively reduced HIF-1α protein levels. We attributed this effect to the release of nitroxyl triggered by the high concentration of GSH (up to 10 mmol L−1) in the cell cytoplasm. Also, this destabilization of HIF-1α levels are consistent with previous observations using the inorganic HNO donor Angeli’s Salt and cis-[Ru(SO3)(NO)(bpy)2]+.41 Interestingly, both compounds were able to reduce HIF-1α protein accumulation even in the presence of a 10-fold excess of a known nitric oxide donor, supporting the key role of nitroxyl. The hypoxia-induced HIF-1α inhibitor YC-1, for example, acts through inactivation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways, but it shows neglectable activity upon high NO concentration.41, 69 This result indicates that a proper HNO donor can function even under conditions stimulated by NO, where not many inhibitors can do. In order to exclude any cytotoxic effect derived from the mixture of ruthenium compound and SPERNO, cell viability assays were held using the maximum Ru-complex concentration tested. No interference in cell growth was observed in those conditions.

Figure 4.

Effect of complexes Ru3 and Ru5 and/or SPER/NO on hypoxia-induced HIF-1α stabilization in breast cancer cells. On the left, WES analysis of HIF-1α protein levels in MB-231 breast cancer cells pre-treated with 1 to 100 μmol L−1 of Ru3 and Ru5 for 30 min, followed by treatment with 100 μmol L−1 SPER/NO for 4 h. On the right, quantitation of WES analysis.

Further assays revealed estimated EC50 values of 30 and 2 μmol L−1 for compounds Ru3 and Ru5, respectively, confirming the enhanced activity of cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(ETU)]3+. The noticeable difference in HIF-1α stabilization for these metal complexes can be associated to distinct HNO donating properties. This might be influenced by the electronic characteristics of the ligands bound to the ruthenium center. It is well-established for nitrosyl metal complexes that both the central atom and ancillary ligands modulate the NO moiety electrophilicity and its reactivity.38, 39 In the case of cis-[Ru(SO3)(NO)(bpy)2]+,41 for example, the σ-donating properties of the sulfur atom of the sulfide anion grants a less electrophilic nitrosyl group (NO+/0 E1/2 = −115 mV vs Ag/AgCl), which showed remarkable nitroxyl release. In this work, the enhanced activity of Ru5 (NO+/0 E1/2 = 75 mV vs Ag/AgCl), when compared to Ru3 (NO+/0 E1/2 = 250 mV vs Ag/AgCl), agrees with that hypothesis, but additional assays need to be performed to confirm it.

Vascular reactivity

Nitrosyl ruthenium complexes have been studied as potential pharmacological alternatives to the treatment of vascular disorders.35, 70 Since NO and HNO play major roles in cellular signaling involving pathways that lead to vasodilation, these coordination compounds can work as pro-drugs in the treatment of cardiovascular conditions, such as arterial hypertension.9

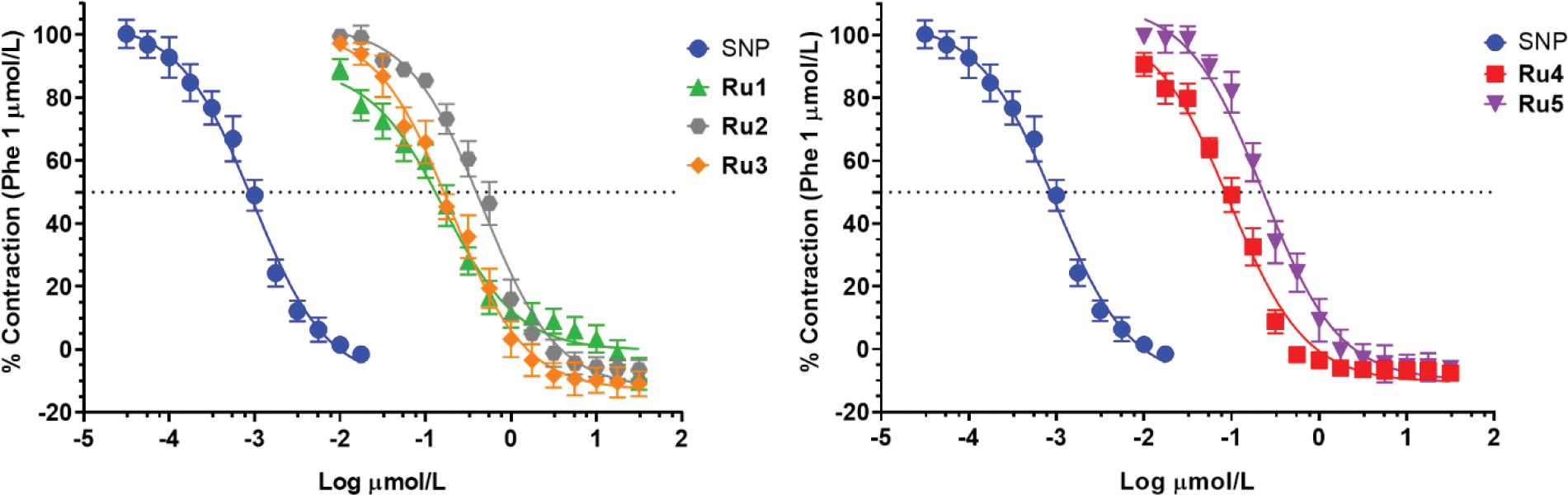

Vasodilation assays were carried out using rat aortic rings pre-contracted with phenylephrine in the presence of the synthetized ruthenium compounds in micromolar range. Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was used as a positive standard. Nitrosyl metal complexes Ru3 and Ru5 were able to cause maximum relaxation of the tissue with EC50 values around 0.198 and 0.229 μmol L−1, respectively (Figure 5). These results suggest that both compounds have almost identical vasodilation activities, but they are still less effective than the standard drug (SNP). However, if compared to other polypyridinic ruthenium complexes containing a NO moiety,37 these compounds showed an improved vasodilating activity, suggesting other factors might be related to their effectiveness, besides nitric oxide donation. Nitroxyl production and/or selective protein activation (e. g. K+ channels) are pathways under investigation that may be involved.71

Figure 5.

Dose-response curves for vasodilation assay in rat aorta using sodium nitroprusside (SNP, circles), complexes Ru1 (triangles), Ru2 (hexagons), Ru3 (prisms), Ru4 (squares) and Ru5 (inverted triangles).

Taking into account those previous data, we carried out similar assays with the precursor metal complexes and free ligands, aiming to find any relationship between the structure and vasodilation response. The precursor cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2] and the ligands 2MIM and ETU showed no appreciable activity and were unable to cause maximum vasorelaxation even at high concentrations (Figure S13). On the other hand, the non-nitrosyl metal complexes Ru1, Ru2 and Ru4 presented noticeable relaxant effect. Surprisingly, both chloride metal complexes exhibited even slightly better EC50 values than their respective analogues containing the NO+ moiety, even though their potencies were equal or inferior (Figure 5 and Table 3). It is worth to mention that, in fact, reports of non-nitrosyl ruthenium compounds with improved vasodilating properties were seen with potential in the treatment of cardiovascular conditions.36 Polypyridinic metal complexes containing N-heterocyclic ligands were able to promote vascular relaxation with high efficiency, showing EC50 as low as 55 nmol L−1. The mechanism of this activity is still unclear, but in vitro and in vivo experiments to elucidate that are in progress already.

Table 3.

EC50 and maximum relaxant effect (Emax) induced by the metal complexes Ru1–5, metal complex precursors and SNP, using isolated aortic rings preparations of rats.

| Compound | EC50 [EC95%] (μmol L−1) | Emax (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| SNP | 0.0009 [0.0007–0.0012] | 111.43±3.90% |

| RuCl2(bpy)2 | 7.5858 [6.6069–8.7096] | 56.49±1.31% |

|

| ||

| 2MIM | > 30 | 29.51±0.98% |

| ETU | > 30 | 38.85±0.85% |

|

| ||

| Ru1 | 0.1651 [0.1148–0.2363] | 98.80±1.98% |

| Ru2 | 0.4645 [0.3766–0.5723] | 112.83±2.18% |

| Ru3 | 0.1982 [0.1477–0.2651] | 112.22±2.23% |

| Ru4 | 0.0950 [0.0759–0.1187] | 110.91±1.49% |

| Ru5 | 0.2288 [0.1765–0.2964] | 111.23±2.53% |

Free radicals scavenging activity

So far, our data showed evidences of potential pharmacological use of the nitrosyl ruthenium complexes in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. It is worthy to mention the combined HIF-1α destabilization effect together with the vasorelaxation activity are strongly desirable characteristics for the treatment of atherosclerosis, one of the most common vascular pathological conditions.7, 68 Since this disorder is associated with accumulation of lipids on the endothelial wall, anomalous blood flow and arterial hypertension are common secondary conditions in patients with atheroma. Atherosclerosis is mainly caused by endothelial disfunction, which takes place when there is a damage on the inner side of the blood vessels.1 This event triggers a series of metabolic pathways, including HIF-1 upregulation, causing inflammation response, endothelial cell disfunction, ROS production and redox imbalance.68 In fact, reactive oxygen species can also cause extensive endothelial damage, creating new points of lipidic accumulation and aggravating the problem.72 Considering this context and the fact nitrosyl complexes have been successfully used as free radical scavengers,73, 74 compounds Ru3 and Ru5 were tested using in vitro models for ROS inhibition.

Cytochrome c reduction assay was employed to measure the superoxide scavenging properties of nitrosyl complexes. The IC50 values for this study are shown on table S3. Compound 3 presented better activity than 5, but both showed EC50 values compatible with other ruthenium-based NO/HNO donors.73 The greater reactivity of cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(2MIM)]3+ towards the superoxide anion is compatible with its higher electrophilic property, which was supported by its higher redox potential (E1/2= 250 mV vs Ag/AgCl). It is important to highlight that the reaction of NO donors with superoxide can favor the production of peroxynitrite, which is a reactive nitrogen-containing anion especially harmful for cell membranes. Tyrosine trapping experiment showed no detectable amounts of this species (figure S14), in accordance with previous studies using other Ru-based nitrosyl complexes.73 On the other hand, TBARS modified assay showed notorious hydroxyl scavenging properties, but no appreciable difference between the activity of these compounds was observed. This finding is coherent with the promiscuous reactivity of this radical.

In order to confirm the relevance of the NO moiety for the radical scavenging activity, the same experiments were conducted with all non-nitrosyl metal complexes. These results revealed the presence of NO is essential for this scavenging activity against superoxide, but it has minor influence in the reactivity towards hydroxyl radical. Altogether, these findings show nitrosyl complexes exhibit important in vitro anti-ROS activity, conferring additional promising properties as model compounds for pharmacological treatment of cardiovascular conditions. As evidenced on table 4, the compounds Ru3 and Ru5 are the first Ru-based nitrosyl donors with vasorelaxant, antioxidant and HIF-1α destabilization properties. Thus, such species have the potential to be used on the pharmacological treatment of cardiovascular diseases through combined therapeutic activities.

Table 4.

Pharmacological profile of ruthenium-based NO donors with vascular relaxation properties. (bpy: 2,2’-bipyridine; bqdi: benzoquinonediimine; ImN: imidazole; HEDTA: ethylenediaminetetraacetate; phen: 1,10-phenantroline; py: pyridine; tbz: thiobenzamide; tpy: 2,2’:6’,2”-terpyridine tu: thiourea)

| Compound | Vascular activity | Antioxidant/Anti-inflammatory | Other properties |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| cis-[Ru(SO3)(NO)(bpy)2]3+ | Isolated aortic rings; Corpus cavernosum75 | Gastric mucosa protection;76 Gout arthrites reduction32 | Microbicide activity;31 HIF-1α destabilization41 |

| cis-[Ru(ImN)(NO)(bpy)2]3+ | Isolated aortic rings;77 Corpora cavernosa78 | - | NO photorelease38 |

| cis-[Ru(tu)(NO)(phen)2]3+ | Isolated aortic rings37 | - | DNA photocleavage37 |

| cis-[Ru(tbz)(NO)(phen)2]3+ | Isolated aortic rings37 | - | DNA photocleavage37 |

| [Ru(NO)(HEDTA)] | Isolated aortic rings79 | - | Acute nociception inhibition80 |

| cis-[RuCl(NO)(bpy)2]+ | Isolated aortic rings81 | - | NO photorelease81 |

| cis-[Ru(NO2)(bpy)2(py)]+ | Isolated aortic rings;81 Hypertensive rats82 | - | - |

| [Ru(NO)(bqdi)(tpy)]3+ | Isolated aortic rings;81 Hypertensive rats83 | - | Bronchodilation84 |

| Ru3 | Isolated aortic rings | ROS scavenging | HIF-1α destabilization |

| Ru5 | Isolated aortic rings | ROS scavenging | HIF-1α destabilization |

Conclusions

The new complexes cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(2MIM)]3+ (Ru3) and cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(ETU)]3+ (Ru5) were synthetized and characterized through spectroscopic and electrochemical techniques, supported by DFT calculations. XANES and EXAFS spectra of these compounds and their precursors were obtained in the solid state, revealing the electronic effects of the NO moiety upon the metal as well as allowing interesting insights on the structure and geometry of these species. As far as we know, this is the first report of an X-ray absorption spectroscopy study of metal complexes with the formulation of [Ru(NO)(bpy)2(L)]n+. Besides this, reactivity assays in solution showed these species can work as HNO releasers in the presence of biological thiols, such as glutathione. This exciting result was validated in cell culture model, where no accumulation of HIF-1α was noticed, a key protein implicated in several disorders. Moreover, vascular reactivity assays showed these compounds caused vasodilation in concentrations lower than 1 μmol L−1. Finally, noticeable in vitro ROS scavenging activity was detected for both nitrosyl complexes. The HIF-1 destabilizer effect combined with the vasorelaxation and antioxidant properties makes Ru3 and Ru5 as promising potential drugs for the treatment of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular conditions. Further in vivo studies are ongoing.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Materials

The metal complex cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2].2H2O was prepared as previously reported.85 All other chemicals and solvents were commercially available with analytical grade and used as received.

Physical Measurements

The electronic absorption spectra in the UV-Vis region were measured using a Hewlett-Packard model 8453 spectrophotometer (USA). Cyclic Voltammetry measurements were held using a potentiostat Epsilon EC model EF-1031 (BAS inc.) at room temperature with a conventional three electrodes cell, where platinum, Ag/AgCl and glassy carbon were used as auxiliary, reference and working electrodes, respectively. Sodium trifluoroacetate solution (0.1 mol L−1, pH 3.0) was used as supporting electrolyte. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) measurements were done in a KBr dispersed pellet in the spectral range of 4000 to 400 cm−1, using an infrared spectrophotometer ABB Bomem FTLA 2000-102 (USA, CA). All mass spectra were recorded on a Agilent G1956B LCMS system with 1100 Series HPLC (LC-MSD) operating in the positive mode ESI(+)-MS and using a range of m/z 100 to 1000 Dalton. 1H NMR spectra were obtained in the designated deuterated solvents on a Bruker 300 or 500 MHz spectrometer (USA). Elemental analysis was performed using a Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II Elemental Analyzer (USA).

Syntheses of complexes

cis-[RuCl(bpy)2(2MIM)]PF6.H2O ([Ru1]PF6.H2O)

A 200 mg (0.413 mmol) of cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2].2H2O and 37.3 mg (0.454 mmol) of 2-methylimidazole (2MIM) were dissolved in 30 mL of anhydrous ethanol under stirring and kept under reflux for 8 hours. This solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation, and precipitation was achieved by adding some drops of saturated NH4PF6 solution. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with ethyl ether and dried under vacuum. Yield: 52% (dark red solid). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C24H22ClF6N6PRu.H2O (Mr = 693.69), %: C, 41.52; H, 3.49; N, 12.11. Found, %: C, 41.68; H, 3.23; N, 11.91%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ 11.39 (s, 1H), 10.21 (s, 1H), 8.83 (d, 1H), 8.68 (d, 1H), 8.55 (t, 2H), 8.47 (d, 1H), 8.12 (t, 3H), 7.93 – 7.80 (m, 4H), 7.78 (d, 1H), 7.67 (t, 1H), 7.24 (dt, 2H), 6.96 (s, 1H). ESI-MS-(+): (calc, found, m/z) 531.063, 531.010, [M – PF6]+. IR (KBr), cm−1: 3439, 3108, 1635, 1463, 1443, 840, 756, 554. UV-vis (MeCN), λmax, nm (ε, 104 M−1 cm−1): 242 (2.36), 295 (4.65), 357 (0.75), 521 (0.74).

cis-[Ru(NO2)(bpy)2(2MIM)]PF6.H2O ([Ru2]PF6.H2O)

A 150 mg (0.288 mmol) of cis-[RuCl(bpy)2(2MIM)]PF6.H2O and 21.9 mg (0.317 mmol) of NaNO2 were dissolved in 30 mL of a solution of ethanol/water (1:1) under stirring, and kept under reflux for 4 hours. The solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation and precipitation was achieved by adding some drops of saturated NH4PF6 solution. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with ethyl ether and dried under vacuum. Yield: 49% (orange solid). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C24H22F6N7OPRu.H2O (Mr = 705.24), %: C, 40.84; H, 3.57; N, 13.90. Found, %: C, 40.71; H, 3.30; N, 14.15%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6)) δ 11.66 (s, 1H), 10.40 (s, 1H), 8.85 (d, 1H), 8.64 (d, 1H), 8.60 (d, 1H), 8.53 (dd, Hz, 2H), 8.24 – 8.16 (m, 2H), 8.08 – 7.95 (m, 4H), 7.95 – 7.87 (m, 2H), 7.76 (t, 1H), 7.40 (t, 1H), 7.30 (dd, 1H), 7.00 (d, 1H), 1.11 (t, 3H). ESI-MS-(+): (calc, found, m/z) 542.087, 542.035, [M – PF6]+; 460.034, 459.997, [M – 2MIM – PF6]+. IR (KBr), cm−1: 3414, 3124, 1635, 1465, 1444, 844, 763, 557. UV-vis (MeCN), λmax, nm (ε, 104 M−1 cm−1): 242 (1.95), 292 (4.32), 338 (0.71), 477 (0.62).

cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(2MIM)](PF6)3 ([Ru3](PF6)3)

A 150 mg (0.212 mmol) of cis-[Ru(NO2)(bpy)2(2MIM)]PF6.H2O was dissolved in 25 mL of a solution of ethanol/water (1:1) under stirring and argon bubbling. Then, a 1 mL of 6 mol L−1 HTFA solution was added and the mixture was kept under those conditions and protected from light for 1 hour. After that, precipitation was achieved by adding some drops of saturated NH4PF6 solution. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with ethyl ether and dried under vacuum. Yield: 61% (light yellow solid). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C24H22F18N7OP3Ru (Mr = 960.15), %: C, 30.01; H, 2.31; N, 10.21. Found, %: C, 30.06; H, 2.38; N, 10.35%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6)) δ 13.39 (s, 1H), 9.56 (d, 1H), 9.14 (d, 1H), 8.99 (t, 2H), 8.92 (d, 1H), 8.85 – 8.77 (m, 1H), 8.67 (t, 1H), 8.53 (q, 4H), 8.17 (dt, 2H), 7.92 (d, 1H), 7.72 (d, 3H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 2,51 (s, 3H). ESI-MS-(+): (calc, found, m/z) 513.097, 513.030, [M – NO – 3PF6 + OH]+; 473.078, 473.020, [M – NO – 3PF6 + H2O + H3CCN]+ IR (KBr), cm−1: 3439, 3130, 1940, 1634, 1472, 1452, 840, 765, 558. UV-vis (MeCN), λmax, nm (ε, 104 M−1 cm−1): 299 (2.07), 331 (0.97).

cis-[RuCl(bpy)2(ETU)]PF6.H2O ([Ru4]PF6.H2O)

A 200 mg (0.413 mmol) of cis-[RuCl2(bpy)2].2H2O and 46.4 mg (0.454 mmol) of ethylenethiourea (ETU) were dissolved in 30 mL of a solution of ethanol/water (1:1) under stirring, and kept under reflux for 4 hours. This solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation and precipitation was achieved by adding some drops of saturated NH4PF6 solution. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with ethyl ether and dried under vacuum. Yield: 58% (dark red solid). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C23H22ClF6N6PRuS.H2O (Mr = 713.66), %: C, 38.67; H, 3.39; N, 11.77. Found, %: C, 38.46; H, 3.20; N, 12.05%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6)) δ 10.00 (d, 1H), 9.84 (d, 1H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.65 (dd, 2H), 8.54 (d, 1H), 8.50 (d, 1H), 8.16 (q, 2H), 7.90 (t, 1H), 7.86 – 7.82 (m, 2H), 7.79 (d, 1H), 7.74 (d, 1H), 7.29 (t, 1H), 7.21 (t, 1H), 3.71 (m, 4H). ESI-MS-(+): (calc, found, m/z) 556.085, 556.040, [M – Cl – PF6 + H3CCN]+; 515.059, 515.004 [M – H – PF6]+. IR (KBr), cm−1: 3406, 3074, 1636, 1462, 1441, 844, 763, 559. UV-vis (MeCN), λmax, nm (ε, 104 M−1 cm−1): 245 (2.51), 295 (5.46), 353 (0.82), 505 (0.76).

cis-[Ru(NO)(bpy)2(ETU)](PF6)3 ([Ru5](PF6)3)

A 150 mg (0.210 mmol) of cis-[RuCl(bpy)2(ETU)]PF6.H2O was dissolved in 25 mL of a solution of ethanol/water (1:1) under stirring and argon bubbling. Gaseous NO, generated through the reaction of NaNO2 with concentrated H2SO4, was bubbled into the metal complex solution for 3 hours protected from light. After that, precipitation was achieved by adding some drops of saturated NH4PF6 aqueous solution. The solid was collected by filtration, washed with ethyl ether and dried under vacuum. Yield: 63% (yellow solid). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C23H22F18N7OP3RuS (Mr = 980.12), %: C, 28.16; H, 2.26; N, 10.00. Found, %: C, 27.91; H, 2.38; N, 9.77%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6)) δ 9.76 (d, 1H), 9.53 (d, 1H), 9.12 (d, 1H), 9.08 (d, 1H), 8.97 (t, 2H), 8.90 – 8.84 (m, 1H), 8.75 (t, 1H), 8.57 – 8.51 (m, 2H), 8.40 – 8.32 (m, 2H), 8.27 (dd, 1H), 7.81 – 7.75 (m, 2H), 7.73 (t, 1H). ESI-MS-(+): (calc, found, m/z) 544.049, 544.006, [M – 2H – 3PF6]+. IR (KBr), cm−1: 3439, 3130, 1940, 1634, 1472, 1452, 840, 765, 558. UV-vis (MeCN), λmax, nm (ε, 104 M−1 cm−1): 299 (2.07), 331 (0.97).

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Ruthenium K-edge XAS measurements were performed at the XDS beamline of the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS/CNPEM). The incident energy was selected by a Si (311) double-crystal monochromator and a toroidal focusing mirror. The incoming X-ray energy was calibrated by setting the maximum of the first derivative of the K-edge of a ruthenium metal foil to 22117 eV.

Ruthenium K-edge XAS measurements of the all complexes were performed in solid state. The solid samples were finely grounded, and the powder was pressed into circular pellets (diameter of 13 mm, height of 1 mm) using a hydraulic press, placed in a customized sample holder and covered with polyimide adhesive tape (Kapton) with about 40 μm thickness. The XAS spectra of the solid samples were acquired at room temperature in transmission mode with three ionization chambers using a mixture of nitrogen and argon. Three to six scans were collected to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Inspection of fast XANES scans revealed no signs of radiation damage, and the first and last scans of each data set used in the averages were identical. Data averaging, background subtraction and normalization were done using the Athena package.86

EXAFS data analysis has been performed using the Arthemis software86 following a procedure described for similar structures.87 Phase and amplitude functions were calculated by FEFF6 code using the structures obtained from DFT calculations as the input. The fits were performed in R-space in the ΔR=1.20–4.00 Å range over k3-weighted Fourier Transform of the χ(k) functions performed in the 2.0–14.0 Å−1 interval.

Theoretical Calculations

Geometry of all complexes were optimized at the density of functional theory (DFT) level. Calculations were executed with Gaussian 09 program package, Revision A.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA)88 using B3LYP functional.89–91 The LANL2DZ92, 93 relativistic effective core potential basis set was used for the Ru atom and the 6-311G(d,p)94 basis set was used for the lighter atoms (C, N, O, S, Cl, H). The absence of imaginary frequencies in vibrational analysis calculations confirmed that all optimized structures were in minimum potential energy.

The TD-DFT (time-dependent density functional theory) approach was employed to investigate the electronic properties of the complexes. UV-vis spectra of all complexes were simulated in acetonitrile, using the polarizable continuum model (PCM).95 Molecular orbital percentual composition, UV-vis spectra and assignment of electronic transitions were extracted from output files through Multiwfn96 and GaussSum 3.097 softwares.

Measurement for the nitrosyl-nitro conversion

A 60 μmol L−1 solution of nitrosyl complex in 0.1 mol L−1 trifluoroacetic acid in water, was titrated with addition of a concentrated sodium hydroxide solution. Variations in the solution pH were followed by changes in the electronic spectrum and absorbance values at 422 and 440 nm were recorded for complexes Ru3 and Ru5, respectively. Spectroscopic changes occurred very fast, indicating that equilibrium was achieved almost immediately after the pH adjustment. A plot of absorbance at these wavelengths versus pH was prepared and fitted to an acid-base equation, to obtain the concentration at which there was 50% of the complex as the nitrosyl species, as described elsewhere.98

NO/HNO spectroscopic detection

HNO detection using ferric-myoglobin and carboxy-PTIO as probes were carried out as described elsewhere. Briefly, a 7 μmol L−1 solution of FeIII-myoglobin or 160 μmol L−1 of cPTIO were prepared in 0.1 mol L−1 phosphate buffer pH 6.2 at 298 K. Reduced glutathione was added together with the nitrosyl complex at mol ratio of 20:1 thiol:complex. UV-vis spectra were taken at regular intervals in order to follow spectral changes.

NO chemiluminescence detection

A Sievers Nitric Oxide Analyzer (NOA) model 280i (GE Analytical Instruments, USA) was used for nitric oxide quantification. The equipment was calibrated using increasing amounts of NO generated in situ by the reaction of NaNO2 with iodide in acidic media. For sample measurements, 5.0 mL of PBS buffer pH 7.4 containing diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, 50 μmol L−1) and reduced glutathione (400 μmol L−1) were placed into the reaction chamber of the equipment and sparged with argon for 10 minutes. Then, an DMSO:water (1:9) solution of the nitrosyl complex was injected into the reaction chamber and NO release was recorded. For HNO indirect detection, an aliquote of aqueous potassium hexacyanoferrate in excess was injected with the complex solution. The total amount of nitric oxide released was determined by integrating the area under the curve and applying a calibration curve. The experiments were held in triplicate.

Cell viability

Normal lung fibroblast cells (MRC5) were kindly provided by the João de Barros Barreto, University Hospital (HUJBB), located in Pará State, Brazil. The cells were kept in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DEMEM, Gibco®), with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco®) and 100 U mL−1 of penicillin and 100 mg mL−1 of streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator of 5% CO2 and 95% of O2.

Cell viability was evaluated by using the Alamar Blue method. Briefly, MRC5 cells (3.103) were seeded in 96-well plate and treated for 72 h with the ruthenium compounds in triplicate. 3 h before the end of the treatment, 20 μL of Alamar Blue™ (0.021% w/v in PBS) were added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C. The fluorescence was measured at 560 nm. Cytotoxicity was calculated using the ratio of fluorescence of treated cells to the fluorescence of control cells (untreated cells), and the data were expressed as percentage, using Prism 7 Software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA), and presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (with three replicates for each concentration tested). For each method, a control sample remained untreated and received only medium.

For the HIF-1α stabilization assay (see next section), the effect of the mixture of ruthenium complex (in the highest concentration used) and SPERNO over the MB-231 breast cancer cells was evaluated. Briefly, trypan blue exclusion was incorporated into cell counts determined by the Vi-CELL XR Viability Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Cells were plated at a density of 1.5×106 and grown overnight. The next day, the cells were pretreated with 100 μmol L−1 Ru3 or Ru5 for 30 min and then treated with 100 μmol L−1 SPERNO for 4 h. The cells were then trypsinized and counted for cell number and cell viability. Additionally, viability was also assessed using Alamarblue (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Cells were plated at 100.000 cells per well in a 96-well flat bottom plate and grown overnight. The next day the cells were treated as described above. At the end of the 4 h treatment 10 ml of 10x Alamarblue solution was added to each well and incubated overnight, then absorbance was read at 590 nm.

HIF-1α stabilization assay

MB-231 cells (2 × 106 cell mL−1) were plated into culture dishes in RPMI complete medium supplemented with 10% HI FBS and penicillin-streptomycin and incubated overnight. The next day, cells were pretreated with the complexes for 30 min in serum-free medium, then treated with 100 μmol L−1 SPER/NO for 4 h or flushed with nitrogen gas for 1.5 h. Then, cells were then rinsed with cold PBS, scrape harvested, centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended and sonicated in lysis buffer [1% Nonidet P-40 0.5% sodium deoxycholate 0.1% SDS and protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem)]. After a 10-min incubation on ice, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g, and the supernatant protein concentration was determined by the bichoncinic acid method (Pierce).

Western blots were performed using the automated capillary-based size sorting system WES (ProteinSimple, San Jose CA). All procedures were performed with manufacturer’s reagents according to their user manual. Briefly, 8 μL of diluted protein lysate was mixed with 2 μL of 5x fluorescent master mix and heated at 368 K for 5 min. The samples (1 μg), blocking reagent, wash buffer, primary antibodies, secondary antibodies, and chemiluminescent substrate were dispensed into designated wells in a manufacturer provided microplate. The plate was loaded into the instrument and protein was drawn into individual capillaries on a 25 capillary cassette provided by the manufacturer. Protein separation and immuno detection were performed automatically on the individual capillaries using default settings. The data were analyzed using Compass software (ProteinSimple, San Jose CA). Primary antibodies used were HIF-1α (diluted 1:100) and HPRT loading control (diluted 1:100). Data are representative of n = 3 individual experiments.

Vascular reactivity

The thoracic aorta of male Winstar rats were removed and treated using standard protocols (for details, see Supplementary Material). Briefly, rat aortas were segmented into 2 mm rings, mounted on a stainless-steel apparatus and immersed into 10 mL organ chambers containing Krebs-Henseleit solution. Each chamber containing an aortic ring was continuously aerated (95% O2 / 5% CO2) and kept at 37°C. These aortic rings were connected to an amplifier (Quad Bridge Amp, ML224, ADInstruments, Australia) and underwent a stabilization period of 60 min in Krebs-Henseleit solution with constant adjustment of basal tension to 1 gF (10 mN). After the stabilization period, the contractile viability was tested by exposing the aortic rings to a solution with a high concentration of KCl (60 mM). Then the vascular preparations were washed and maintained in normal Krebs-Henseleit solution and exposed to phenylephrine (1.0 μmol L−1) followed by acetylcholine (10.0 μmol L−1) to test the integrity of the endothelium. An aortic ring was considered to have intact endothelium when acetylcholine was able to induce 80% relaxation of pre-contraction induced by phenylephrine. To evaluate the potential vasorelaxant effect of ruthenium compounds, cumulative concentration-effect curves were obtained by exposing intact endothelium aorta preparations pre-contracted with phenylephrine (1.0 μmol L−1) to increasing concentrations (0.01 to 30 μmol L−1) of the compounds. The experiments were recorded by using a data acquisition system (Power Lab, ML8661P, 4130, ADInstruments, Australia) and data was analyzed through the software LabChart 8.0 (ADInstruments, Australia).

The EC50 values (i.e., compound concentration in μmol L−1 that relaxes a contraction by 50%) were calculated by interpolation from semi-logarithmic plots and are expressed as geometric mean [95% confidence interval]. The significance (p < 0.05) of results for EC50 was assessed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

All experimental procedures used with animals were previously approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Federal University of Ceará (protocol number 03/2016).

Partition coefficient (log P)

Partition coefficient was determined by the shake-flask methodology as described elsewhere.99 Briefly, the complex was dissolved in ultrapure water and the initial concentration was measured spectrophotometrically (ca. 30 μmol L−1). That solution was mixed with an equal volume of n-octanol (previously saturated with PBS for 24 h) and shaken for 1 h using an automated shaker and allowed to stand for 1 h. Aliquots from the aqueous phase were extracted and analyzed by electronic spectroscopy in order to determine the complex amount in this solution. The concentration in the n-octanol layer was calculated by the difference of the concentration found in the aqueous layer and expressed as log P, where: log P = log ([Ru]octanol/[Ru]water). All measurements were held in triplicate.

Free Radical Scavenger Assay

The superoxide generation and detection were carried out as described elsewhere.73 In a typical experiment, superoxide was generated by enzymatic oxidation of hypoxantine (200 μmol L−1) to xanthine and uric acid by xanthine oxidase (0.016 U mL−1) in PBS buffer pH 7.4. Ferricytochrome c (20 μmol L−1) was used to probe superoxide production, detected spectroscopically (λ=550 nm) by the heme group reduction. The radical scavenger effect of the complexes was tested in the range of 10 – 1000 μmol L−1.

The hydroxyl radical scavenger activity was determined by modified thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS) assay, as previously described.100, 101 Briefly, hydroxyl was generated by Fenton reaction using FeCl3 (25 μmol L−1), nitriloacetic acid (100 μmol L−1) and hydrogen peroxide (250 μmol L−1) in PBS buffer pH 7.4. 2-deoxy-D-ribose (100 μmol L−1) was used to probe hydroxyl reaction, which produces malondialdehyde (MDA) is major product. Reaction of MDA with thiobarbituric acid in excess (1 mmol L−1), followed by heating (100°C, 15 min), forms a product detectable by UV-vis spectroscopy (λ=532 nm). Scavenger activity of the compounds under study were tested in the concentration range of 10 – 500 μmol L−1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank CENAPAD-UFC for computer facilities, CENAUREM-UFC for the acquisition of NMR spectra, Chemistry Biology Laboratory – Mass Spectroscopy Core (NCI – Frederick) for the ESI-MS analysis and the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS, CNPEM) for the XANES/EXAFS experiments, under proposal XDS 20180389. Additionally, we are thankful to the Brazilian agencies CAPES (Finance code 001, PROEX 23038.000509/2020-82), CNPq (L. G. F. Lopes 303355/2018-2, E. H. S. Sousa 308383/2018-4, Edital Universal 01/2016 403866/2016-2, F.S. Gouveia Jr 206738/2017-0), FUNCAP (PPSUS12535691-9, PRONEX PR2-0101-00030.01.00/15 SPU No: 3265612/2015) and NIH Intramural Research Program for financial support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Flora GD and Nayak MK, Curr Pharm Des, 2019, 25, 4063–4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobiyama K and Ley K, Circ Res, 2018, 123, 1118–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saigusa R, Winkels H and Ley K, Nat Rev Cardiol, 2020, 17, 387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, Bu X, Kelly TN, Mills KT, He H, Chen J, Whelton PK and He J, JAMA Cardiol, 2017, 2, 775–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naseem KM, Mol Aspects Med, 2005, 26, 33–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JY, Ye ZX, Wang XF, Chang J, Yang MW, Zhong HH, Hong FF and Yang SL, Biomed Pharmacother, 2018, 97, 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie RH, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, De Silva TM and Kemp-Harper BK, Pharmacol Res, 2017, 116, 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzaga de França Lopes L, Gouveia FS Júnior, Karine Medeiros Holanda A, Maria Moreira de Carvalho I, Longhinotti E, Paulo TF, Abreu DS, Bernhardt PV, Gilles-Gonzalez M-A, Cirino Nogueira Diógenes I and Henrique Silva Sousa E, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2021, 445. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farah C, Michel LYM and Balligand JL, Nat Rev Cardiol, 2018, 15, 292–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ignarro LJ, Nitric Oxide: Biology and Pathobiology, Elsevier Science, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghimire K, Altmann HM, Straub AC and Isenberg JS, Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2017, 312, C254–C262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlstrom M, Nat Rev Nephrol, 2021, 17, 575–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picon-Pages P, Garcia-Buendia J and Munoz FJ, Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2019, 1865, 1949–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basudhar D, Bharadwaj G, Somasundaram V, Cheng RYS, Ridnour LA, Fujita M, Lockett SJ, Anderson SK, McVicar DW and Wink DA, Br J Pharmacol, 2019, 176, 155–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muniz Carvalho E, Silva Sousa EH, Bernardes-Génisson V and Gonzaga de França Lopes L, European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 2021, DOI: 10.1002/ejic.202100527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nag OK, Lee K, Stewart MH, Oh E and Delehanty JB, Ther Deliv, 2022, 13, 403–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hottinger DG, Beebe DS, Kozhimannil T, Prielipp RC and Belani KG, J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 2014, 30, 462–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anthony EJ, Bolitho EM, Bridgewater HE, Carter OWL, Donnelly JM, Imberti C, Lant EC, Lermyte F, Needham RJ, Palau M, Sadler PJ, Shi H, Wang FX, Zhang WY and Zhang Z, Chem Sci, 2020, 11, 12888–12917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.da Silva Filho PM, Andrade AL, Lopes J, Pinheiro AA, de Vasconcelos MA, Fonseca S, Lopes LGF, Sousa EHS, Teixeira EH and Longhinotti E, Int J Pharm, 2021, 610, 121220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Ballesteros MM, Mejia C and Ruiz-Azuara L, FEBS Open Bio, 2022, 12, 880–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rilak Simović A, Masnikosa R, Bratsos I and Alessio E, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2019, 398. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galczynska K, Drulis-Kawa Z and Arabski M, Molecules, 2020, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riccardi C, Musumeci D, Trifuoggi M, Irace C, Paduano L and Montesarchio D, Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2019, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva JP, Fuganti O, Kramer MG, Facchin G, Aquino LEN, Ellena J, Back DF, Gondim ACS, Sousa EHS, Lopes LGF, Machado S, Guimaraes IDL, Wohnrath K and de Araujo MP, Dalton Trans, 2020, 49, 16498–16514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Silveira Carvalho JM, de Morais Batista AH, Nogueira NAP, Holanda AKM, de Sousa JR, Zampieri D, Bezerra MJB, Stefânio Barreto F, de Moraes MO, Batista AA, Gondim ACS, de F. Paulo T, de França Lopes LG and Sousa EHS, New J. Chem, 2017, 41, 13085–13095. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li F, Collins JG and Keene FR, Chem Soc Rev, 2015, 44, 2529–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira G. d. F. S., Gouveia FS, Pinheiro A. d. A., do Nascimento Neto LG, de Vasconcelos MA, Teixeira EH, Gondim ACS, Lopes L. G. d. F., de Carvalho IMM and Sousa EHS, New Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 44, 6610–6622. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopes LGF, Carvalho EM and Sousa EHS, Dalton Trans, 2020, 49, 15988–16003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva JJ, Guedes PM, Zottis A, Balliano TL, Nascimento Silva FO, Franca Lopes LG, Ellena J, Oliva G, Andricopulo AD, Franco DW and Silva JS, Br J Pharmacol, 2010, 160, 260–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miranda MM, Panis C, Cataneo AH, da Silva SS, Kawakami NY, Lopes LG, Morey AT, Yamauchi LM, Andrade CG, Cecchini R, da Silva JJ, Sforcin JM, Conchon-Costa I and Pavanelli WR, PLoS One, 2015, 10, e0125101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcusso Orsini T, Kawakami NY, Panis C, Fortes AP, Santos Thomazelli Dos, Tomiotto-Pellissier F, Cataneo AH, Kian D, Megumi Yamauchi L, Gouveia FS Junior, de Franca Lopes LG, Cecchini R, Nazareth Costa I, Jerley Nogueira da Silva J, Conchon-Costa I and Pavanelli WR, Mediators Inflamm, 2016, 2016, 2631625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossaneis AC, Longhi-Balbinot DT, Bertozzi MM, Fattori V, Segato-Vendrameto CZ, Badaro-Garcia S, Zaninelli TH, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Borghi SM, Carvalho TT, Bussmann AJC, Gouveia FS Jr., Lopes LGF, Casagrande R and Verri WA Jr., Front Pharmacol, 2019, 10, 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasahara GL, Gouveia Junior FS, Rodrigues RO, Zampieri DS, Fonseca S, Goncalves RCR, Athaydes BR, Kitagawa RR, Santos FA, Sousa EHS, Nagao-Dias AT and Lopes LGF, J Inorg Biochem, 2020, 206, 111048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa PPC, Waller SB, Dos Santos GR, Gondim FL, Serra DS, Cavalcante FSA, Gouveia Junior FS, de Paula Junior VF, Sousa EHS, Lopes LGF, Ribeiro WLC and Monteiro HSA, PLoS One, 2021, 16, e0248394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campelo MW, Oria RB, Lopes LG, Brito GA, Santos AA, Vasconcelos RC, Silva FO, Nobrega BN, Bento-Silva MT and Vasconcelos PR, Neurochem Res, 2012, 37, 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sa DS, Fernandes AF, Silva CD, Costa PP, Fonteles MC, Nascimento NR, Lopes LG and Sousa EH, Dalton Trans, 2015, 44, 13633–13640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva CDS, Paz IA, Abreu FD, de Sousa AP, Verissimo CP, Nascimento NRF, Paulo TF, Zampieri D, Eberlin MN, Gondim ACS, Andrade LC, Carvalho IMM, Sousa EHS and Lopes LGF, J Inorg Biochem, 2018, 182, 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cândido MCL, Oliveira AM, Silva FON, Holanda AKM, Pereira WG, Sousa EHS, Carneiro ZA, Silva RS and Lopes LGF, Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 2015, DOI: 10.5935/0103-5053.20150159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva FO, Candido MC, Holanda AK, Diogenes IC, Sousa EH and Lopes LG, J Inorg Biochem, 2011, 105, 624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlowska E, Babak MV, Domotor O, Enyedy EA, Rapta P, Zalibera M, Bucinsky L, Malcek M, Govind C, Karunakaran V, Farid YCS, McDonnell TE, Luneau D, Schaniel D, Ang WH and Arion VB, Inorg Chem, 2018, 57, 10702–10717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva Sousa EH, Ridnour LA, Gouveia FS Jr., Silva da Silva CD, Wink DA, de Franca Lopes LG and Sadler PJ, ACS Chem Biol, 2016, 11, 2057–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Switzer CH, Flores-Santana W, Mancardi D, Donzelli S, Basudhar D, Ridnour LA, Miranda KM, Fukuto JM, Paolocci N and Wink DA, Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1787, 835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sedigh Rahimabadi P, Khodaei M and Koswattage KR, X-Ray Spectrometry, 2020, 49, 348–373. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coppens P, Iversen B and Larsen FK, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2005, 249, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garino C, Borfecchia E, Gobetto R, van Bokhoven JA and Lamberti C, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2014, 277–278, 130–186. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravel B, in X-Ray Absorption and X-Ray Emission Spectroscopy, 2016, DOI: 10.1002/9781118844243.ch11, pp. 281–302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labra-Vazquez P, Boce M, Tasse M, Mallet-Ladeira S, Lacroix PG, Farfan N and Malfant I, Dalton Trans, 2020, 49, 3138–3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Sousa AP, do Nascimento JS, Ayala AP, Bezerra BP, Sousa EHS, Lopes LGF and Holanda AKM, Polyhedron, 2019, 167, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vrbanac J and Slauter R, in A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development, 2017, DOI: 10.1016/b978-0-12-803620-4.00003-7, pp. 39–67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayliss MK, Butler J, Feldman PL, Green DV, Leeson PD, Palovich MR and Taylor AJ, Drug Discov Today, 2016, 21, 1719–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutkowska E, Pajak K and Jozwiak K, Acta Pol Pharm, 2013, 70, 3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipinski CA, Drug Discov Today Technol, 2004, 1, 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doak BC, Over B, Giordanetto F and Kihlberg J, Chem Biol, 2014, 21, 1115–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engin K, Leeper DB, Cater JR, Thistlethwaite AJ, Tupchong L and McFarlane JD, Int J Hyperthermia, 1995, 11, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corbet C and Feron O, Nat Rev Cancer, 2017, 17, 577–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menyhart MTO,A, Frank R, Hantosi D, Farkas E and Bari F, Biology (Basel), 2020, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szaciłowski K, Wanat A, Barbieri A, Wasielewska E, Witko M, Stochel G and Stasicka Z, New J. Chem, 2002, 26, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Souza ML, Roveda AC, Pereira JCM and Franco DW, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2016, 306, 615–627. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roncaroli F and Olabe JA, Inorg Chem, 2005, 44, 4719–4727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pereira JCM, Souza ML and Franco DW, European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 2015, 2015, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pereira JC, Carregaro V, Costa DL, da Silva JS, Cunha FQ and Franco DW, Eur J Med Chem, 2010, 45, 4180–4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bonavida B, Biochem Pharmacol, 2020, 176, 113913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li B, Ming Y, Liu Y, Xing H, Fu R, Li Z, Ni R, Li L, Duan D, Xu J, Li C, Xiang M, Song H and Chen J, Front Pharmacol, 2020, 11, 923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norris AJ, Sartippour MR, Lu M, Park T, Rao JY, Jackson MI, Fukuto JM and Brooks MN, Int J Cancer, 2008, 122, 1905–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Semenza GL, Oncogene, 2010, 29, 625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lim CS, Kiriakidis S, Sandison A, Paleolog EM and Davies AH, J Vasc Surg, 2013, 58, 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nanduri J, Peng YJ, Yuan G, Kumar GK and Prabhakar NR, J Mol Med (Berl), 2015, 93, 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jain T, Nikolopoulou EA, Xu Q and Qu A, Pharmacol Ther, 2018, 183, 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li SH, Shin DH, Chun YS, Lee MK, Kim MS and Park JW, Mol Cancer Ther, 2008, 7, 3729–3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vatanabe IP, Rodrigues C, Buzinari TC, Moraes TF, Silva RSD and Rodrigues GJ, Arq Bras Cardiol, 2017, 109, 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodrigues GJ, Pereira AC, de Moraes TF, Wang CC, da Silva RS and Bendhack LM, Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 2015, 65, 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burtenshaw D, Kitching M, Redmond EM, Megson IL and Cahill PA, Front Cardiovasc Med, 2019, 6, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Metzker G, Cardoso DR and Franco DW, Polyhedron, 2013, 50, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Metzker G, de Aguiar I, Souza ML, Cardoso DR and Franco DW, Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 2014, 92, 788–793. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cerqueira JB, Silva LF, Lopes LG, Moraes ME and Nascimento NR, Int Braz J Urol, 2008, 34, 638–645; discussion 645–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Santana AP, Tavares BM, Lucetti LT, Gouveia FS Jr., Ribeiro RA, Soares PM, Sousa EH, Lopes LG, Medeiros JV and Souza MH, Nitric Oxide, 2015, 45, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Costa PPC, Campos R, Cabral PHB, Gomes VM, Santos CF, Waller SB, de Sousa EHS, Lopes LGF, Fonteles MC and do Nascimento NRF, Res Vet Sci, 2020, 130, 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leitao Junior AS, Campos RM, Cerqueira JB, Fonteles MC, Santos CF, de Nucci G, Sousa EH, Lopes LG, Gonzaga-Silva LF and Nascimento NR, Int J Impot Res, 2016, 28, 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zanichelli PG, Miotto AM, Estrela HF, Soares FR, Grassi-Kassisse DM, Spadari-Bratfisch RC, Castellano EE, Roncaroli F, Parise AR, Olabe JA, de Brito AR and Franco DW, J Inorg Biochem, 2004, 98, 1921–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Staurengo-Ferrari L, Mizokami SS, Fattori V, Silva JJ, Zanichelli PG, Georgetti SR, Baracat MM, da Franca LG, Pavanelli WR, Casagrande R and Verri WA Jr., Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 2014, 387, 1053–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Lima RG, Silva BR, da Silva RS and Bendhack LM, Molecules, 2014, 19, 9628–9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pereira AC, Araujo AV, Paulo M, Andrade FA, Silva BR, Vercesi JA, da Silva RS and Bendhack LM, Nitric Oxide, 2017, 62, 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munhoz FC, Potje SR, Pereira AC, Daruge MG, da Silva RS, Bendhack LM and Antoniali C, Nitric Oxide, 2012, 26, 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Castro PF, de Andrade DL, Reis Cde F, Costa SH, Batista AC, da Silva RS and Rocha ML, Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, 2016, 43, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sullivan BP, Salmon DJ and Meyer TJ, Inorganic Chemistry, 2002, 17, 3334–3341. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ravel B and Newville M, J Synchrotron Radiat, 2005, 12, 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salassa L, Ruiu T, Garino C, Pizarro AM, Bardelli F, Gianolio D, Westendorf A, Bednarski PJ, Lamberti C, Gobetto R and Sadler PJ, Organometallics, 2010, 29, 6703–6710. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frisch GWTMJ, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada FDJ, Journal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF and Frisch MJ, The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 2002, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Becke AD, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee C, Yang W and Parr RG, Phys Rev B Condens Matter, 1988, 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hay PJ and Wadt WR, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1985, 82, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wadt WR and Hay PJ, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1985, 82, 284–298. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frenking G and Koch W, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1986, 84, 3224–3229. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mennucci B, Cancès E and Tomasi J, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 1997, 101, 10506–10517. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lu T and Chen F, J Comput Chem, 2012, 33, 580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O’Boyle NM, Tenderholt AL and Langner KM, J Comput Chem, 2008, 29, 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lopes LGF, Wieraszko A, El-Sherif Y and Clarke MJ, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 2001, 312, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Roy S, Colombo E, Vinck R, Mari C, Rubbiani R, Patra M and Gasser G, Chembiochem, 2020, 21, 2966–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Gajewski E and Dizdaroglu M, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1989, 264, 20509–20512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inoue S and Kawanishi S, Cancer Research, 1987, 47, 6522–6527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.