Abstract

Coronaviruses (CoV), including SARS-CoV-2, modulate host proteostasis pathways during infection through activation of stress-responsive signaling pathways such as the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). The UPR regulates protein translation, increases protein folding capacity and enhances endoplasmic reticulum (ER) biogenesis to alleviate ER stress caused by accumulation of misfolded proteins. CoVs depend on host machinery to generate large amounts of viral protein and manipulate ER-derived membranes to form double-membrane vesicles (DMVs), which serve as replication sites, making the UPR a key host pathway for CoVs to hijack. Despite the importance of CoV nonstructural proteins (nsps) in mediating replication, little is known about the role of nsps in modulating the UPR. We characterized the impact of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4, which is a key driver of DMV formation, on the UPR using quantitative proteomics. We find nsp4 preferentially activates the ATF6 and PERK branches of the UPR. Previously, we found an N-terminal truncation of nsp3 (nsp3.1) can suppress pharmacological activation of the ATF6 pathway. To determine how nsp3.1 and nsp4 might tune the UPR in concert, both proteins were co-expressed demonstrating that nsp3.1 does not suppress nsp4-mediated ATF6 activation but does suppress PERK activation. A meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection proteomics data reveals a time-dependent activation of PERK protein markers early in infection, which subsequently fades. This temporal regulation suggests a role for nsps tuning the PERK pathway to attenuate host translation beneficial for viral replication while avoiding later apoptotic signaling caused by chronic PERK activation. This work furthers our understanding of CoV-host proteostasis interactions and identifies potential areas to target for anti-viral therapies.

Keywords: coronavirus, proteomics, stress response, nonstructural protein, ATF6, PERK

Introduction

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has caused the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in more than 6.8 million deaths to date1. Coronaviruses (CoV) require host cell translation machinery and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) derived membranes for replication. CoV infection is known to induce ER stress and activate the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)2–4. The UPR alleviates stress from accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen by temporarily suppressing global protein translation, increasing the production of ER chaperones, expanding ER membrane synthesis, and if stress persists, triggering apoptosis. The UPR is composed of three branches that signal downstream of their respective ER-membrane localized stress sensors: 1. protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK), 2. Inositol requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and 3. activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) pathways 5,6.

Activation of PERK leads to the phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and attenuation of global protein translation to prevent further accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER. A select group of proteins are translated under these conditions, including activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), which upregulates expression of various genes involved in protein folding, antioxidant response, and the pro-apoptotic transcription factor C/EBP Homologous Protein (CHOP)7,8. IRE1α has endoribonuclease activity which, upon ER stress, splices X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) transcripts, leading to translation of the XBP1s transcription factor and increased gene expression of ER protein chaperones, translocation and secretion factors, and components of ER-associated degradation (ERAD), as well as ER biogenesis9. Lastly, ATF6 is translocated to the Golgi upon ER stress, where it is cleaved by site-1 and site-2-proteases. The N-terminal fragment (ATF6p50) is a transcription factor which initiates upregulation of various protein folding, secretion, and degradation factors, as well as expansion of the ER5,6,10,11.

Coronavirus replication requires extensive production, folding, and modification of viral proteins12, as well as alteration of ER-derived membranes to form double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) for replication sites. These processes can trigger ER stress and activate the UPR13. Indeed, a previous study found that all three branches of the UPR are activated during SARS-CoV-2 infection and that expression of SARS-CoV-2 Spike or orf8 protein is sufficient to activate the UPR3. SARS-CoV proteins orf3a and orf8ab were also found to activate the PERK and ATF6 pathways respectively14,15. A related betacoronavirus, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), has also been found to trigger activation of XBP1 and PERK pathways while also hindering production of certain UPR-responsive genes such as CHOP4.

Surprisingly, relatively little is known about the impact of CoV nonstructural proteins (nsps) on the UPR. Nsps are the first viral proteins translated during infection, rewire the host cell, and replicate the viral genome. In particular, three transmembrane nsps (nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6) are responsible for DMV formation from ER-derived membranes16. Nsp3 contains a papain-like protease domain (PL2pro), which cleaves the orf1a/b polypeptide and also possesses deubiquination/de-ISGylation activity17,18. Nsp4 is a glycoprotein containing four transmembrane domains and plays a key role in membrane reorganization19,20.

We have previously characterized the interactomes of nsp3 and nsp4 CoV homologs and found that both proteins have evolutionary conserved interactions with several ER proteostasis factors21,22. We identified an interaction between an N-terminal fragment of SARS-CoV-2 nsp3 (nsp3.1) and ATF6 and showed that nsp3.1 can suppress pharmacologic activation of the ATF6 pathway22. Given the known role of nsp4 in host membrane alteration, we sought to understand if nsp4 activates or suppresses the UPR and whether nsp4 may act in concert with nsp3 to tune UPR activation. In particular, we leveraged a quantitative proteomics approach to characterize the upregulation of UPR targets6,23,24. A more precise understanding of the role of CoV nsps in modulating the UPR will further our knowledge of how coronavirus replication manipulates host proteostasis pathways during infection.

Results

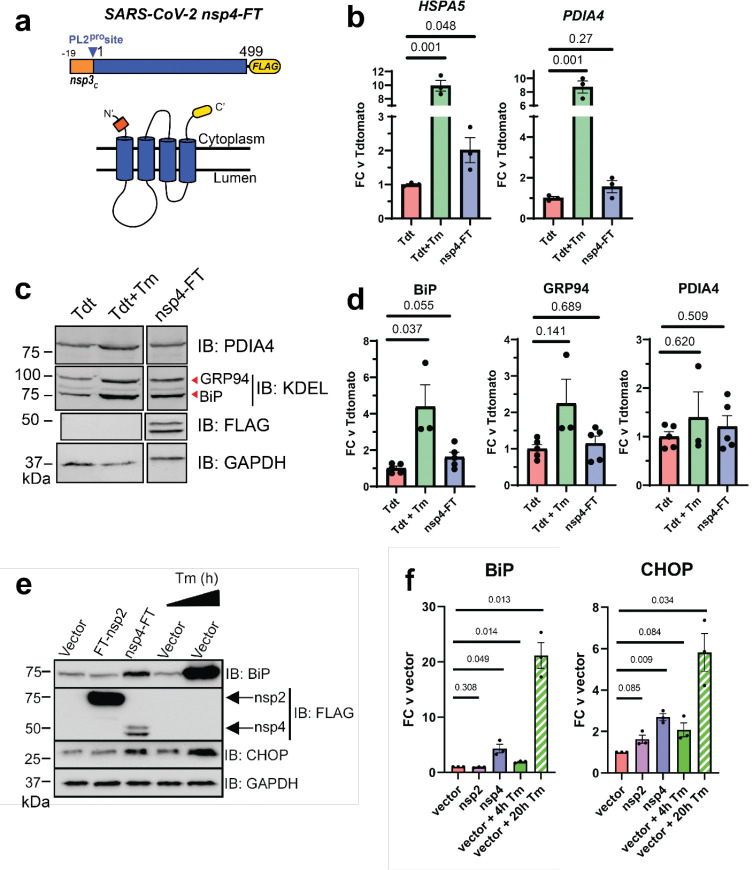

SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 upregulates expression of UPR reporter proteins

Given the role of nsp4 in modulating host ER membranes during infection, we hypothesized that nsp4 may induce ER stress and subsequently activate the UPR pathway. To test this, we exogenously expressed a C-terminally FLAG-tagged SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 construct (nsp4-FT, Fig. 1a) in HEK293T cells as previously reported21 and measured transcript and protein expression of several UPR branch markers. Tdtomato (Tdt) expression was used as a negative control and treatment with tunicamycin (Tm, 1 μg/mL, 6 h) was used as a positive control for general UPR activation. Using RT-qPCR, we found that nsp4-FT expression led to a moderate but signification upregulation of HSPA5 transcripts, a global marker for UPR induction, and upregulation of PDIA4 transcripts, an ATF6 branch-specific marker, though not significantly (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 upregulates expression of UPR reporter proteins.

a) SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 expression construct and membrane topology, containing a C-terminal FLAG-tag (nsp4-FT) and an N-terminal segment of the last 19 C-terminal amino acids in nsp3 for optimal membrane insertion21. Construct contains the native PL2pro protease cleavage site.

b) RT-qPCR of ATF6 pathway activation reporters HSPA5 and PDIA4 in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-FT, normalized to GAPDH transcripts. Treatment with 1 μg/mL Tunacimycin (Tm) for 6 h was used as a positive control. n = 3, mean ±SEM, Student’s t-test for significance.

c) Representative Western blot of ATF6 protein markers (PDIA4, GRP94, BiP) in the presence of Tdtomato (Tdt), SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-FT, or treatment with 1 μg/mL Tm (16 h), with GAPDH as a housekeeping gene for loading control. Displayed blot sections are from the same blot image and exposure settings (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for all quantified blots).

d) Quantification of Tdtomato (Tdt), and nsp4-FT in Western blots in (c), normalized to GAPDH band intensities. N = 3–5, mean ±SEM Student’s t-test for significance.

e) Representative Western blot of CHOP and BiP in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 FT-nsp2, nsp4-FT, or treatment with 5 μg/mL Tm for short (4h) or long (20h) time points. See Supplementary Fig. S2 for all quantified blots.

f) Quantification of Western blots in (e), normalized to GAPDH band intensities. N=3, mean ±SEM Student’s t-test, with Welch’s correction, and p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

To probe downstream protein expression of ATF6 UPR markers, we measured BiP, GRP94, and PDIA4 levels by Western blot in the presence of nsp4-FT (Fig. 1c,d,e,f, Supplementary Fig. S1, S2). Quantification of the control and nsp4-FT lanes show that nsp4 induces a modest upregulation of ATF6 reporter proteins (Fig. 1d,f). We also found that nsp4-FT induces strong CHOP protein upregulation (Fig. 1e,f, Supplementary Fig. S2), while expression of SARS-CoV-2 FT-nsp2 (a cytosolic viral protein) does not. These results indicate that SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 activates the UPR, but overall upregulation of gene targets is lower compared to strong ER stress induced by tunicamycin.

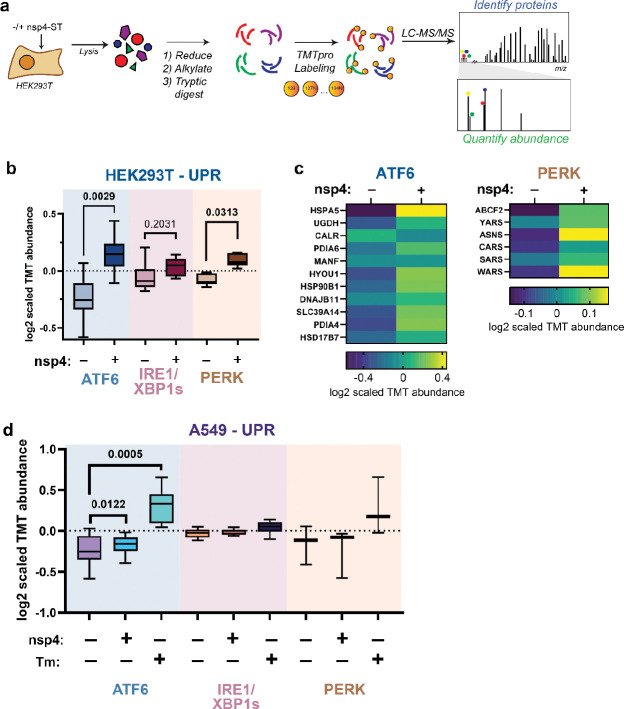

Nsp4 upregulates the ATF6 and PERK pathways as measured by quantitative proteomics

To comprehensively characterize the modulation of the UPR by nsp4, we analyzed the global proteome of HEK293T cells transfected with SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-StrepTag (nsp4-ST) using tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with TMTpro isobaric tags to quantify protein abundance (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Samples were normalized to total peptide abundance and scaled for comparisons (Supplementary Fig. S3). Using a previously defined gene grouping for ATF6, IRE1/XBP1s, and PERK pathway effector proteins6,24,25, we compared pathway upregulation in the absence or presence of nsp4 (Fig. 2b). We found that both the ATF6 and PERK pathways were significantly upregulated.

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 upregulates the ATF6 and PERK pathways as measured by quantitative proteomics.

a) Experimental schematic to measure UPR induction by SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST expression in HEK293T cells using tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS).

b) Log2 scaled TMT abundances of UPR branch protein markers in the absence or presence of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST, as outlined in (a). Box-and-whisker plot shows median, 25th and 75th quartiles, and minimum and maximum values. n = 3 biological replicates, 1 MS run, Wilcoxon test for significance, p values < 0.05 are bolded. See Supplemental Tables S1, S2 for mass spectrometry data set.

c) Heatmap of individual ATF6 and PERK protein markers’ Log2 scaled TMT abundances in the absence or presence of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST, from (b).

d) Log2 scaled TMT abundances of UPR branch protein markers in A549 lung epithelial cells the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-FT or Tunicamycin (1 μg/mL, 16 h). Box-and-whisker plot shows median, 25th and 75th quartiles, and minimum and maximum values. n = 4 biological replicates, 1 MS run, Wilcoxon test for significance, p values < 0.05 are annotated. See Supplemental Tables S3, S4 for mass spectrometry data set.

We also examined the abundances of individual proteins identified within the ATF6 and PERK pathways (Fig. 2c). There was a heterogeneous ATF6 response to nsp4 expression, with some proteins (DNAJB11 and MANF) displaying relatively small change while others (HSPA5, PDIA4, HYOU1, HSP90B1) showed much higher upregulation. Comparing to previously published proteomics dataset22, we find nsp4-ST induces higher expression of ATF6 markers over basal levels compared to a specific ATF6 pharmacological activator, compound 147, but to a lesser extent than Tm treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4). We found that the PERK pathway upregulation by nsp4 was largely dominated by changes in ASNS and WARS abundance (Fig. 2c).

To determine if this phenotype extends to disease-relevant cell models, we expressed SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-FT in A549 lung epithelial cells and measured changes in UPR markers via TMTpro LC/MS-MS (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Tables S3, S4). As a positive control for UPR activation, we included samples treated with Tm (1 μg/mL, 16 h). ATF6 protein markers are moderately but statistically significantly increased in the presence of nsp4, though to a lesser extent than in HEK293T cells, indicative of some cell-type specific effects. Together, these results indicate SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 activates an ATF6 and PERK response characterized by substantial ER chaperone upregulation, but the overall response is mutated compared to treatment with a strong ER stressor.

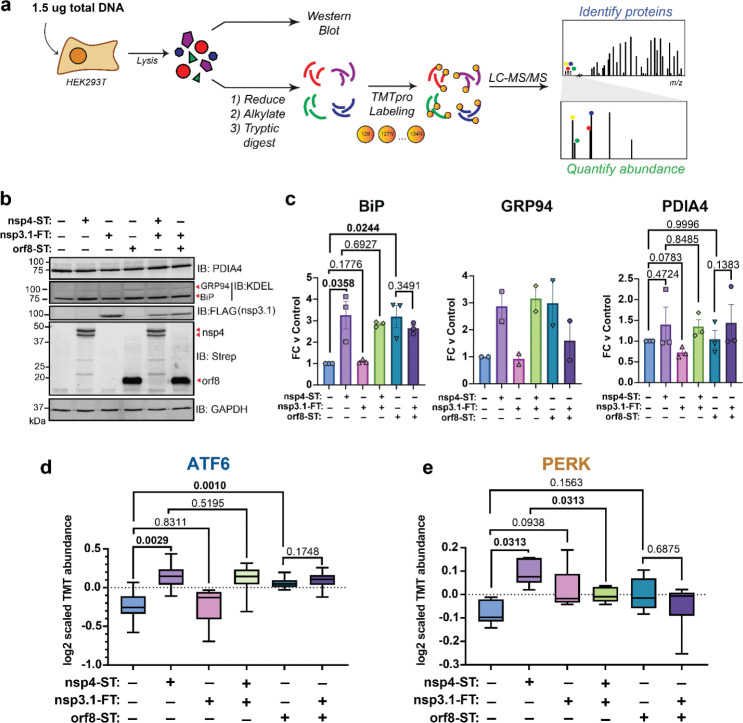

SARS-CoV-2 nsp3.1 suppresses nsp4-induced PERK activation, but not ATF6 activation

Nsp4 and nsp3 are key inducers of double-membrane vesicle (DMV) formation during CoV replication16,19, which, along with viral protein production, may induce ER stress and the UPR. We previously showed an N-terminal fragment of nsp3 (nsp3.1) suppresses pharmacological ATF6 activation22. Therefore, we sought to test whether nsp3.1 might dampen nsp4-induced UPR activation, providing a form of viral tuning of the host UPR. To this end, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST and nsp3.1-FT in equal amounts and measured the effect on ATF6 protein reporters by Western blot and UPR markers by mass spectrometry (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Co-transfections of each plasmid with a GFP-expression plasmid served as comparisons to ensure comparable protein expression amounts. A GFP transfection served as a control for basal UPR levels. In addition, we tested if nsp3.1 could suppress UPR activation induced by SARS-CoV-2 orf8-ST, another viral protein known to activate the UPR3. All transfections included the same total amount of DNA (1.5 μg).

Figure 3. SARS-CoV-2 nsp3.1 suppresses nsp4-induced PERK, but not ATF6 activation.

a) Experimental schematic to test effect of SARS-CoV-2 nsp3.1 on nsp4- or orf8-induced activation of the UPR in HEK293T cells by Western blot and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

b) Representative Western blot of ATF6 protein markers (PDIA4, BiP, GRP94) and viral proteins (SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST, nsp3.1-FT, and orf8-ST), with GAPDH as a housekeeping gene for a loading control. See Supplementary Fig. S5 for all quantified blots.

c) Quantification of Western blots in (b), normalized to GAPDH band intensities. N = 2–3, mean ±SEM, Student’s t-test was used to test significance, p-values shown.

d) Global proteomics analysis of ATF6 protein marker levels in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-ST, nsp3.1-FT, orf8-ST, or specified combinations. Box-and-whisker plot shows median, 25th and 75th quartiles, and minimum and maximum values. Wilcoxon test for significance, p values shown; 1 MS run, n = 2–3 biological replicates. See Supplemental Tables S1, S2 for mass spectrometry data set.

e) Global proteomics analysis of PERK protein marker levels, as in (d).

As expected, we found that transfection with nsp4 and orf8 individually induced higher protein expression of the ATF6 markers BiP, GRP94, and PDIA4 as measured by Western blot (Fig. 3b,c, Supplementary Fig. S5). Nsp3.1 did not lead to any notable decrease in the expression of ATF6 markers when co-expressed with nsp4 or orf8.

Using mass spectrometry to analyze a larger set of UPR protein markers in these same lysates, we found that nsp3.1 does not suppress nsp4-induced ATF6 activation (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, we found that co-expression of nsp3.1 with nsp4 significantly lowers PERK marker levels compared to nsp4 alone (Fig. 3e). IRE1/XBP1s activation was not significantly decreased with co-expression of nsp3.1 with nsp4 compared to nsp4 alone (Supplementary Fig. S6). These results demonstrate that nsp3.1 is not capable of suppressing ATF6 activation induced by other viral proteins, such as nsp4 or orf8, but can suppress PERK activation.

Curiously, we also noted nsp3.1 protein levels are lower in co-transfections with nsp4 versus GFP, as seen by both Western blotting (Fig. 3b) and proteomics (Supplementary Fig. S7). Examining global changes in the proteome with nsp4 expression showed few proteins are substantially down- or up-regulated (Supplementary Fig. S7). Therefore, it is likely that this is a specific effect on nsp3.1 protein levels.

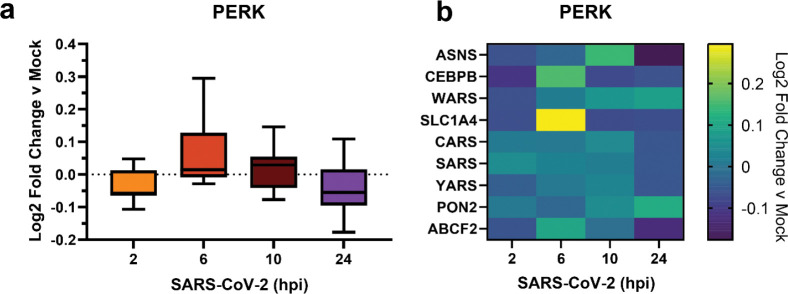

Meta-analysis shows time-dependent PERK activation during SARS-CoV-2 infection

Previous work has shown that the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway is activated during SARS-CoV-2 infection3. A meta-analysis of global proteomics during SARS-CoV-2 infection in Caco-2 cells26 shows a moderate upregulation of PERK-induced protein markers at 6 hpi that is downregulated by 24 hpi (Fig. 4). This disconnect between signaling induction and protein marker levels may be explained by nsps, such as nsp3.1, moderating the PERK pathway to interfere with host translation through eIF2α phosphorylation while avoiding ATF4/CHOP-mediated cell death.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of PERK activation in global proteomics data of Caco-2 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2.

a) Box-and-whisker plot of PERK protein markers during SARS-CoV-2 infection (2–24 hours post infection (hpi)) compared to mock infected samples. Box-and-whisker plot shows median, 25th and 75th quartiles, and minimum and maximum values.

b) Heatmap of individual PERK protein markers as in (a). Dataset published by Bojkova, et al. 202026.

Discussion

Previous studies show that SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MHV activate branches of the UPR to varying degrees2–4,14,15, however the role of nsps in this process has remained largely unexplored. Of particular interest are the nsps involved in host membrane alteration to promote infection by DMV formation, such as nsp3 and nsp4. In this work, we find that SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 activates the ATF6 and PERK branches of the UPR in HEK292T cells (Fig. 1,2). This is evident by both Western blotting for ATF6 markers such as BiP and GRP94 and the PERK marker CHOP (Fig. 1). We further harnessed the capabilities of quantitative proteomics to measure pathway changes in these branches, allowing for more comprehensive analysis of UPR branch activation (Fig. 2).

We also find that nsp4 activates the ATF6 pathway in A549 cells, though more moderately compared to HEK293T cells (Fig. 2d), indicating cell-specific effects that may be tied to variable nsp4 protein expression in different cells. In both HEK293T and A549 cells the overall degree of UPR activation by nsp4 is lower than with the ER stressor tunicamycin (Fig. 2d, Supplemental Fig. S4). This is in line with the moderate UPR activation observed in viral infection, where chronic, high UPR activation may trigger apoptosis and counter-productive effects for viral replication.

It is pertinent to further study the molecular mechanisms by which nsp4 (and other CoV proteins) trigger UPR activation. We have previously profiled a comparative interactome of nsp4 homologs21 and did not identify protein interactions with ATF6 protein as we had with nsp322, making it unlikely that signaling occurs through a direct interaction with the sensor protein. As a multi-pass transmembrane protein, nsp4 may be prone to misfolding or alternatively, may modulate host ER membranes, which can trigger ATF6 activation in some cases27. Further work will be needed to define the precise molecular mechanisms by which nsp4 activates the ATF6 and PERK branches.

We previously showed that an N-terminal fragment of SARS-CoV-2 nsp3, nsp3.1, interacts with ATF6 and can suppress pharmacological activation of the ATF6 pathway22. We hypothesized that nsp3 and nsp4 may act in concert to tune the UPR and capitalize on the increased protein folding capacity via UPR activation while minimizing apoptotic effects of chronic activation. We found that co-expression of nsp3.1 with nsp4 or orf8 does not repress ATF6 activation but does suppress nsp4-induced PERK activation (Fig. 3). Time-dependent PERK activation was evident from global proteomics data during SARS-CoV-2 infection26 showing an increase in target protein levels during the first 6 hpi, followed by a later decline (Fig. 4). This tight temporal regulation suggests a role for the nsps in moderating PERK signaling to permit the early signaling events (eIF2α-mediated host translational attenuation) that are beneficial for viral propagation while preventing ATF4/CHOP-mediated induction of apoptosis.

The precise mechanism by which nsp3.1 suppresses nsp4-induced PERK activation will require further investigation. SARS-CoV-2 nsp3.1 directly interacts with ATF3 22, a PERK protein marker which is upregulated by ATF4 and promotes pro-apoptotic signaling 28. This protein interaction may represent one avenue by which the PERK pathway is tuned by nsp3.1 to limit apoptosis in infected cells.

The absence of ATF6 suppression in co-expression is surprising, given that we previously showed nsp3.1 could suppress ATF6 activation by tunicamycin treatment, which potently activates the global UPR through inhibition of protein glycosylation. This may suggest that the mechanisms by which nsp4 activates the ATF6 pathway are distinct from a general tunicamycin stressor and can overcome the opposing effects of nsp3.1. Alternatively, nsp4-induced ATF6 activation may be too low for nsp3.1 to have any measurable effect (Supplementary Fig. S4). In the context of viral infection, there are multiple points of UPR induction by nsp4, orf8, Spike, ER membrane perturbation, etc. which in combination may require partial suppression by nsp3.1 to tune the host UPR and prevent host cell apoptosis.

Relatedly, co-expression of nsp4 with nsp3.1 leads to a noticeable decrease of nsp3.1 levels compared to control co-expression of GFP with nsp3.1 (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. S7). This drop in protein levels may in part explain the lack of ATF6 suppression by nsp3.1. It is unclear how nsp4 effects nsp3.1 levels. While ATF6 activation increases production of ERAD factors to clear misfolded proteins, nsp3.1 is a cytosolic fragment of nsp3 and should not be subject to increased ERAD.

Additional questions remain regarding nsps and the UPR, such as how conserved is UPR activation across nsp4 homologs? Does nsp6, another key protein in DMV formation16, have a similar effect on the UPR? And how might nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6 affect the UPR in concert? Using quantitative proteomics to measure changes in UPR-induced protein expression, as we have done here, should prove a powerful and efficient tool in answering these questions.

Lastly, previous work has shown that UPR inhibition can attenuate SARS-CoV-23 and MERS-CoV29 infection. Viral families beyond coronaviruses, such as flaviviruses, have been shown to rely on the UPR and can be inhibited using UPR modulators30–32. These opposing phenotypes, in which either UPR activation or inhibition can disrupt infection, highlight the important and diverse functions the UPR plays in viral replication. Continued efforts to delineate the roles of individual viral proteins in modifying the UPR will be critical to the further development of UPR-targeting anti-virals. Our work contributes to this goal by identifying a new role for SARS-CoV-2 nsp4 as a potent UPR activator and the coordination of nsp3.1 with nsp4 to tune the PERK pathway.

Materials and Methods

DNA Constructs

SARS-CoV-2 nsp4-FT, nsp3-FT, FT-nsp2, and orf8-FT (Wuhan-Hu-1 MN908947) were codon-optimized and cloned into a pcDNA-(+)-C-DYK vector (Genscript) or pcDNA-(+)-N-DYK vector for nsp2 (Genscript). An N-terminal truncation nsp3.1-FT (residues 1–749) was generated as previously described 21. Nsp4-ST and orf8-ST constructs were generated through the NEB HiFi Assembly system. In brief, the FLAG-tag from nsp4-FT was removed through amplification with primers 3 & 4 respectively. A 2xStrepTag was amplified from a SARS-CoV-2 nsp2-ST in a pLVX-EF1alpha plasmid construct (kind gift from Dr. Nevan Krogan, University of California, San Francisco) using primers 1 & 2. The linear nsp4 product were then combined with the 2xStrepTag fragment via HiFi assembly (1:2 vector to insert ratio). The orf8-ST construct was made by amplifying out the orf8 gene from the pcDNA-(+)-C-DYK vector using primers 5 & 6. A pLVX-EF1alpha-SARS-CoV-2-nsp2–2xStrepTag plasmid was linearized using primers 7 & 8, retaining the vector backbone and 2xStrepTag while removing the nsp2 gene. These were then combined via HiFi assembly (1:2 vector to insert ratio). Plasmids were verified by sequencing (Genewiz).

Primers

| ID | Primer | Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2xStrepTag_rem_F | CTCGAAGGCGGCGGGGGA | Amplification of 2xStrepTag from pLVX vector |

| 2 | 2xStrepTag_rem_R | TTACTTTTCAAACTGCGGATGTGACCATGATCCAC | Amplification of 2xStrepTag from pLVX vector |

| 3 | nsp4_Wuhan_xFT_F | ATCCGCAGTTTGAAAAGTAATAAACCCGCTGATCAGCC | Removal of FLAG tag from nsp4 |

| 4 | nsp4_Wuhan_xFT_R | CATCCCCCGCCGCCTTCGAGCAGGACTGCGGAAGTAATG | Removal of FLAG tag from nsp4 |

| 5 | Wuhan-orf8_F | CCGGTGAATTCGCCGCCACCATGAAGTTCCTGGTATTTC | Amplification of orf8 gene from pcDNA vector |

| 6 | Wuhan-orf8_R | CATCCCCCGCCGCCTTCGAGAATAAAGTCCAAGACCAC | Amplification of orf8 gene from pcDNA vector |

| 7 | pLVX_F | CTCGAAGGCGGCGGGGGA | Amplication of pLVX vector with 2xStrepTag |

| 8 | pLVX_R | GGTGGCGGCGAATTCACCG | Amplication of pLVX vector with 2xStrepTag |

| 9 | GAPDH-qPCR_F | GTCGGAGTCAACGGATT | |

| 10 | GAPDH-qPCR_R | AAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG | |

| 11 | HSPA5-qPCR_F | GCCTGTATTTCTAGACCTGCC | |

| 12 | HSPA5-qPCR_R | TTCATCTTGCCAGCCAGTTG | |

| 13 | PDIA4-qPCR_F | agtggggaggatgtcaatgc | |

| 14 | PDIA4-qPCR_R | tggctgggatttgatgactg |

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293T and A549 lung epithelial cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Growth Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (DMEM-10). Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/well. HEK293T cells were transfected drop-wise, twenty-four hours after seeding, using a calcium phosphate cocktail (1.5 μg total DNA, 0.25 M CaCl2, 1x HBS (137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, 7.5 mM D-glucose, 21 mM HEPES)). The media was changed 18 hours later with fresh DMEM-10 media. A549 cells were seeded in antibiotic-free DMEM-10 and 24 h later were transfected with FuGENE 4K transfection reagent (1.5 μg DNA with 4.5 μL FuGENE 4K) in plain Optimem media. Samples were treated with DMSO or Tunicamycin (Tm, 1 μg/mL) for 16 h (protein analysis) or 6 h (RNA analysis) prior to harvest in described experiments. Transfected cells were harvested by cell scraping in cold 1 mM EDTA in PBS over ice, 40 h post-transfection. To measure CHOP levels, HEK293T cells were transfected twenty-four hours after seeding, using 1μg cDNAs and 6 μl of 1mg/ml PEI (pre-mixed in 50 μl of serum-free culture medium). Samples were treated with Tunicamycin (Tm, 5 μg/mL) for 4h or 20h prior to harvest.

RT-qPCR

HEK293T cells were transfected and harvested as described previously. Cellular RNA was extracted using the Zymo QuickRNA miniprep kit and 500 ng total cellular RNA was synthesized into cDNA using random hexamer primers (IDT), oligo-dT primers (IDT), and Promega M-MLV reverse transcriptase. qPCR analysis was carried out using BioRad iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix, added to respective primers (primers 9–14) for target genes and reactions were run in 96-well plates on a BioRad CFX qPCR instrument. Conditions used for amplification were 95°C, 2 min, 45 repeats of 95°C, 10 s and 60°C, 30 s. A melting curve was generated in 0.5°C intervals from 65 to 95°C. Cq values were calculated by the BioRad CFX Maestro software and transcripts were normalized to a housekeeping gene (GAPDH). All measurements were performed in technical duplicate; technical duplicates were averaged to form a single biological replicate.

Western Blot Analysis

HEK293T cells were lysed on ice in TNI buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 0.5% IGEPAL-CA-630) with Roche protease inhibitor for 15 minutes and then sonicated for 10 minutes in a water bath at room temperature. A549 cells were lysed on ice in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate) with Roche protease inhibitor for 15 minutes. Lysates were spun down at 21.1k xg for 15 minutes at 4°C. Samples were added to 6x Laemelli buffer (12% SDS, 125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, bromophenol blue, 100 mM DTT) and heated at 37°C for thirty minutes. The samples were then run on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane for Western blotting. M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma Aldrich, F1804), anti-KDEL (Enzo ADI-SPA-827-F), anti-PDIA4 (ProteinTech 14712–1-AP), THE anti-Strep II tag FITC (Genescript, A01736–100), and anti-GAPDH (GeneTex, GTX627408) antibodies were used to probe Western blots at a 1:1000 dilution in TBS blocking buffer (0.1% Tween, 5% BSA, 0.1% Sodium Azide).

To measure CHOP protein levels, HEK293T cells were lysed on ice in 1% CHAPS lysis buffer (50 mM Tris H-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% CHAPS, 10 μM pepstatin, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.2 μM soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 1mM DTT; pH 8.0) for 30 minutes. Lysates were spun down at 16,000 xg for 10 minutes at 4°C. Samples were added to 4x gel-loading buffer (50mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.8), 100mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% Bromophenol Blue, 10% glycerol, 100 mM DTT) and heated at 37°C for thirty minutes. The samples were then run on an 13% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma Aldrich, F1804), anti-BiP #3177 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-CHOP #7351, and anti-GAPDH #365062 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), antibodies were used to probe Western blots in TBS blocking buffer (0.1% Tween, 4% BSA, 0.1% Sodium Azide). GAPDH signal was used to normalize band intensities. Protein expression on Western blots was quantified using ImageLab.

Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

Samples were harvested and lysed as described above. Protein concentration was quantified using 1x BioRad Protein Assay Dye and 20 μg of protein from each sample was prepared for mass spectrometry. Proteins were precipitated via mass spectrometry grade methanol:chloroform:water (in a 3:1:3 ratio) and washed three times with methanol. Each wash was followed by a 2 minute spin at 10,000×g at room temperature. Protein pellets were air dried 30–45 min and resuspended in 5 μL of 1% Rapigest SF (Waters). Resuspended proteins were diluted with 32.5 μL water and 10 μL 0.5 M HEPES (pH 8.0), then reduced with 0.5 μL of freshly made 0.5 M TCEP for 30 minutes at room temperature. Samples were then acetylated with 1 μL of fresh 0.5 M Iodoacetamide (freshly made) for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark and digested with 0.5 μg Trypsin/Lys-C (Thermo Fisher) overnight at 37°C shaking. Peptides were diluted to 60 μL with LC/MS-grade water and labeled using TMTpro labels (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. Labeling was quenched with the addition of fresh ammonium bicarbonate (0.4% v/v final) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then pooled, acidified to pH < 2.0 using formic acid, concentrated to 1/6th original volume via Speed-vac, and diluted back to the original volume with buffer A (95% water, 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid). Cleaved Rapigest products were removed by centrifugation at 17,000×g for 30 minutes and supernatant transferred to fresh tubes.

MudPIT LC-MS/MS Analysis

Alternating layers of 1.5cm C18 resin, 1.5cm SCX resin, and 1.5cm C18 resin were packed to make triphasic MudPIT columns as described previously33. TMT-labeled samples (20 μg) were loaded onto the microcapillaries via a high-pressure chamber, followed by a 30-minute wash in buffer A (95% water, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid). The MudPIT columns were installed on the LC column switching valve and followed by a 20cm fused silica microcapillary column filled with Aqua C18, 3μm resin (Phenomenex) ending in a laser-pulled tip. Columns were washed in the same way as the MudPIT capillaries prior to use. Liquid chromatography (Ultimate 3000 nanoLC system) was used to fractionate the peptides online and then analyzed via an Exploris480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). MudPIT runs were carried out by 10μL sequential injections of 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100% buffer C (500mM ammonium acetate, 94.9% water, 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid), followed by a final injection of 90% C, 10% buffer B (99.9% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid v/v). Each injection was followed by a 130 min gradient using a flow rate of 500nL/min (0–6 min: 2% buffer B, 8 min: 5% B, 100 min: 35% B, 105min: 65% B, 106–113 min: 85% B, 113–130 min: 2% B). ESI was performed directly from the tip of the microcapillary column using a spray voltage of 2.2 kV, an ion transfer tube temperature of 275°C and a RF Lens of 40%. MS1 spectra were collected using a scan range of 400–1600 m/z, 120k resolution, AGC target of 300%, and automatic injection times. Data-dependent MS2 spectra were obtained using a monoisotopic peak selection mode: peptide, including charge state 2–7, TopSpeed method (3s cycle time), isolation window 0.4 m/z, HCD fragmentation using a normalized collision energy of 36%, 45k resolution, AGC target of 200%, automatic maximum injection times, and a dynamic exclusion (20 ppm window) set to 60s.

Peptide identification and quantification

Identification and quantification of peptides were performed in Proteome Discoverer 2.4 (Thermo Fisher) using the SwissProt human database (TaxID 9606, released 11/23/2019; 42,252 entries searched) with nsp3.1, nsp4, and orf8 fragment sequences (3 entries) manually added (42,255 total entries searched). Searches were conducted with Sequest HT using the following parameters: trypsin cleavage (maximum two missed cleavages), minimum peptide length 6 AAs, precursor mass tolerance 20 ppm, fragment mass tolerance 0.02 Da, dynamic modifications of Met oxidation (+15.995 Da), protein N-terminal Met loss (−131.040 Da), and protein N-terminal acetylation (+42.011 Da), static modifications of TMTpro (+304.207 Da) at Lys, and N-termini and Cys carbamidomethylation (+57.021 Da). Peptide IDs were filtered using Percolator with an FDR target of 0.01. Proteins were filtered based on a 0.01 FDR, and protein groups were created according to a strict parsimony principle. TMT reporter ions were quantified considering unique and razor peptides, excluding peptides with co-isolation interference greater that 25%. Peptide abundances were normalized based on total peptide amounts in each channel, assuming similar levels of background. Protein abundances were also scaled and protein quantification used all quantified peptides. Post-search filtering was done to include only proteins with two identified peptides.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

HEK293T UPR analysis combined 2–3 biological replicates into 1 individual MS run (3x GFP, 3x nsp3.1-FT+GFP, 3x nsp4-ST+GFP, 3x nsp3.1-FT+nsp4-ST, 2x orf8-ST+GFP, 2x orf8-ST+nsp3.1-FT). A549 UPR analysis combined 4 biological replicates into 1 individual MS run (4x GFP, 4x GFP+Tm, 4x nsp4-FT). Pairwise ratios between conditions were calculated in Proteome Discoverer normalized to total protein abundances and scaled.

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD039797. All other necessary data are contained within the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Nevan Krogan (University of California, San Francisco) for the pLVX-EF1alpha-SARS-CoV-2-nsp2–2xStrepTag plasmid. We thank members of the Plate lab for their critical reading and feedback on this manuscript. Work was funded by R35GM133552 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences) and Vanderbilt University start-up funds. J.P.D. was supported by T32GM008554 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences). R.J.H.W was supported by R01DK107944 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) and R01GM121621 (National Institute of General Medical Sciences).

Footnotes

Additional Information

The authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.WHO. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19. World Heal. Organ. 1;4 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue M. & Feng L. The Role of Unfolded Protein Response in Coronavirus Infection and Its Implications for Drug Design. Front. Microbiol. 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Echavarría-Consuegra L. et al. Manipulation of the unfolded protein response: A pharmacological strategy against coronavirus infection. PLOS Pathog. 17, e1009644 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bechill J., Chen Z., Brewer J. W. & Baker S. C. Coronavirus Infection Modulates the Unfolded Protein Response and Mediates Sustained Translational Repression. J. Virol. 82, 4492–4501 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter P. & Ron D. The Unfolded Protein Response: From Stress Pathway to Homeostatic Regulation. Science (80-.). 334, 1081–1086 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoulders M. D. et al. Stress-Independent Activation of XBP1s and/or ATF6 Reveals Three Functionally Diverse ER Proteostasis Environments. Cell Rep. 3, 1279–1292 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szegezdi E., Logue S. E., Gorman A. M. & Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 7, 880–885 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding H. P., Zhang Y., Bertolotti A., Zeng H. & Ron D. Perk Is Essential for Translational Regulation and Cell Survival during the Unfolded Protein Response. Mol. Cell 5, 897–904 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee A.-H., Iwakoshi N. N. & Glimcher L. H. XBP-1 Regulates a Subset of Endoplasmic Reticulum Resident Chaperone Genes in the Unfolded Protein Response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7448–7459 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T. & Mori K. Mammalian Transcription Factor ATF6 Is Synthesized as a Transmembrane Protein and Activated by Proteolysis in Response to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3787–3799 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi Y. et al. ATF6 Is a Transcription Factor Specializing in the Regulation of Quality Control Proteins in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cell Struct. Funct. 33, 75–89 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aviner R. & Frydman J. Proteostasis in Viral Infection: Unfolding the Complex Virus–Chaperone Interplay. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12, a034090 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fung T. S. & Liu D. X. Coronavirus infection, ER stress, apoptosis and innate immunity. Front. Microbiol. 5, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minakshi R. et al. The SARS Coronavirus 3a Protein Causes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Induces Ligand-Independent Downregulation of the Type 1 Interferon Receptor. PLoS One 4, e8342 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung S.-C., Chao C.-Y., Jeng K.-S., Yang J.-Y. & Lai M. M. C. The 8ab protein of SARS-CoV is a luminal ER membrane-associated protein and induces the activation of ATF6. Virology 387, 402–413 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angelini M. M., Akhlaghpour M., Neuman B. W. & Buchmeier M. J. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Nonstructural Proteins 3, 4, and 6 Induce Double-Membrane Vesicles. MBio 4, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei J., Kusov Y. & Hilgenfeld R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: Structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antiviral Res. 149, 58–74 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin D. et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 587, 657–662 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oostra M. et al. Localization and Membrane Topology of Coronavirus Nonstructural Protein 4: Involvement of the Early Secretory Pathway in Replication. J. Virol. 81, 12323–12336 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beachboard D. C., Anderson-Daniels J. M. & Denison M. R. Mutations across Murine Hepatitis Virus nsp4 Alter Virus Fitness and Membrane Modifications. J. Virol. 89, 2080–2089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies J. P., Almasy K. M., McDonald E. F. & Plate L. Comparative Multiplexed Interactomics of SARS-CoV-2 and Homologous Coronavirus Nonstructural Proteins Identifies Unique and Shared Host-Cell Dependencies. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 3174–3189 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almasy K. M., Davies J. P. & Plate L. Comparative Host Interactomes of the SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 3 and Human Coronavirus Homologs. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 20, 100120 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plate L. et al. Quantitative Interactome Proteomics Reveals a Molecular Basis for ATF6-Dependent Regulation of a Destabilized Amyloidogenic Protein. Cell Chem. Biol. 26, 913–925.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plate L. et al. Small molecule proteostasis regulators that reprogram the ER to reduce extracellular protein aggregation. Elife 5, 1–26 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandjean J. M. D. et al. Deconvoluting Stress-Responsive Proteostasis Signaling Pathways for Pharmacologic Activation Using Targeted RNA Sequencing. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 784–795 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bojkova D. et al. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature 1–8 (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volmer R., van der Ploeg K. & Ron D. Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 4628–4633 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edagawa M. et al. Role of Activating Transcription Factor 3 (ATF3) in Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress-induced Sensitization of p53-deficient Human Colon Cancer Cells to Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-related Apoptosis-inducing Ligand (TRAIL)-mediated Apoptosis through Up-regulation of Death Receptor 5 (DR5) by Zerumbone and Celecoxib. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 21544–21561 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sims A. C. et al. Unfolded Protein Response Inhibition Reduces Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-Induced Acute Lung Injury. MBio 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peña J. & Harris E. Dengue virus modulates the unfolded protein response in a time-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 14226–14236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almasy K. M. et al. Small-molecule endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis regulator acts as a broad-spectrum inhibitor of dengue and Zika virus infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolpikova E. P. et al. IRE1α Promotes Zika Virus Infection via XBP1. Viruses 12, 278 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonslow B. R. et al. Single-Step Inline Hydroxyapatite Enrichment Facilitates Identification and Quantitation of Phosphopeptides from Mass-Limited Proteomes with MudPIT. J. Proteome Res. 11, 2697–2709 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD039797. All other necessary data are contained within the manuscript.