Abstract

Cellular senescence has been identified as a pathological mechanism linked to tau and amyloid beta (Aβ) accumulation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Clearance of senescent cells using the senolytic compounds dasatinib (D) and quercetin (Q) reduced neuropathological burden and improved clinically relevant outcomes in the mice. Herein, we conducted a vanguard open-label clinical trial of senolytic therapy for AD with the primary aim of evaluating central nervous system (CNS) penetrance, as well as exploratory data collection relevant to safety, feasibility, and efficacy. Participants with early-stage symptomatic AD were enrolled in an open-label, 12-week pilot study of intermittent orally-delivered D+Q. CNS penetrance was assessed by evaluating drug levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Safety was continuously monitored with adverse event reporting, vitals, and laboratory work. Cognition, neuroimaging, and plasma and CSF biomarkers were assessed at baseline and post-treatment. Five participants (mean age: 76±5 years; 40% female) completed the trial. The treatment increased D and Q levels in the blood of all participants ranging from 12.7 to 73.5 ng/ml for D and 3.29–26.30 ng/ml for Q. D levels were detected in the CSF of four participants ranging from 0.281 to 0.536 ng/ml (t(4)=3.123, p=0.035); Q was not detected. Treatment was well-tolerated with no early discontinuation and six mild to moderate adverse events occurring across the study. Cognitive and neuroimaging endpoints did not significantly differ from baseline to post-treatment. CNS levels of IL-6 and GFAP increased from baseline to post-treatment (t(4)=3.913, p=008 and t(4)=3.354, p=0.028, respectively) concomitant with decreased levels of several cytokines and chemokines associated with senescence, and a trend toward higher levels of Aβ42 (t(4)=−2.338, p=0.079). Collectively the data indicate the CNS penetrance of D and provide preliminary support for the safety, tolerability, and feasibility of the intervention and suggest that astrocytes and Aβ may be particularly responsive to the treatment. While early results are promising, fully powered, placebo-controlled studies are needed to evaluate the potential of AD modification with the novel approach of targeting cellular senescence.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia, a devastating condition that affects over 35 million individuals worldwide1. Historically, drug development for the indication of AD has been among the slowest, most expensive, and least successful with a failure rate of over 99%2. Fortunately, recent years have seen the development of disease modifying drugs capable of removing abnormal aggregations of amyloid beta (Aβ) from the brain3. Despite these successes, the anti-amyloid drugs have only yielded modest clinical results, spurring consideration of new drug targets and combination treatments3,4.

The majority of individuals with AD present with multiple etiological contributors to dementia5, suggesting that therapeutic targets beyond Aβ and tau deposition may have a role in treatment. Towards this end, our preclinical research has highlighted cellular senescence as a mechanism that may underlie pathological tau accumulation6,7. Cellular senescence is a complex stress response triggered by various stimuli, including macromolecular damage (such as DNA damage), proteotoxic stress, oncogene activation, reactive metabolites, mitochondrial dysfunction, and infections, among others8. The stress response leads to a change in cell fate whereby senescent cells enter a near-permanent cell cycle arrest mediated through tumor suppressive pathways9. Senescent cells also acquire a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)10,11. The SASP is comprised of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix re-modeling components, which can spread in a paracrine manner and propagate the senescent phenotype to neighboring cells8,12. In the context of aging and neurodegenerative disease, senescent cell accumulation has been identified in multiple cell types within the central nervous system, including neurons6,7,13,14, astrocytes15,16, microglia17,18, oligodendrocyte precursor cells19, and endothelial cells20.

Experimental evidence to support the role of cellular senescence in AD neuropathology has been provided by preclinical trials employing senolytics. Senolytics are pharmacological agents which selectively ablate senescent cells and were first identified through interrogation of the senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathways (SCAPs)21. At present, dasatinib (D), a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor that is FDA-approved for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)22, and quercetin (Q), a natural plant-based flavonoid with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antineoplastic properties23, are the best characterized senolytics8. When combined, D+Q has been shown to selectively clear senescent cells in culture in both humans and animal models8,24,25. In preclinical trials of murine models, D+Q has ameliorated multiple chronic age-related conditions; we previously reported the first evidence to support the potential therapeutic efficacy of D+Q for neurodegenerative disease. Within four tau transgenic mouse models, we found that biweekly administration of D+Q relative to placebo resulted in a 35% reduction in cortical NFT accumulation, which correlated with reduced cortical brain atrophy and restored aberrant cerebral blood flow6. Other research teams confirmed the association between tau and senescence18 and the effective clearance of senescent cells using D+Q in an Aβ producing mouse model19.

Given the compelling evidence provided by preclinical research6,19, coupled with the encouraging safety profiles reported in human studies of D+Q for other disease indications26,27, we conducted the first clinical trial of senolytic therapy for AD. The aim of the study was to evaluate penetration of D and Q in the central nervous system by performing mass spectrometry on cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) collected prior to treatment and within 80 to 150 minutes of the final study drug dose. We further aimed to collect data on secondary outcomes including safety and feasibility, target engagement of the senolytic compounds, AD CSF and plasma biomarkers, and cognition, neuroimaging, and functional status. We enrolled five participants with early-stage symptomatic AD in an open-label 12-week intervention of intermittent senolytic therapy and provide the first report of the trial outcomes.

Methods

The study is an open-label single-site pilot study of 12-week intermittent senolytic therapy in older adults with early-stage AD with the primary aim of evaluating the central nervous system penetrance of D and Q (NCT04063124)28. Secondary trial aims were to 1) evaluate target engagement of D+Q by examining changes markers associated with cellular senescence and the SASP; 2) assess the safety and tolerability of the intervention; 3) examine pre- to post-treatment changes in cognition and functional status; and 4) assess changes in neuroimaging and biofluid markers of AD and related dementias (ADRD). The study was conducted in adherence with the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the protocol was approved by the local institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent with appropriate legal representation for individuals lacking capacity to consent.

Participants:

Eligibility for the study included adults aged 65 years and over with a diagnosis of AD based on the criteria for the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association29 and a Global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale score of 130. Anticholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine use were allowed following a minimum of a three-month stabilization period. Full eligibility criteria were applied as described in Gonzales et al28.

Study Design:

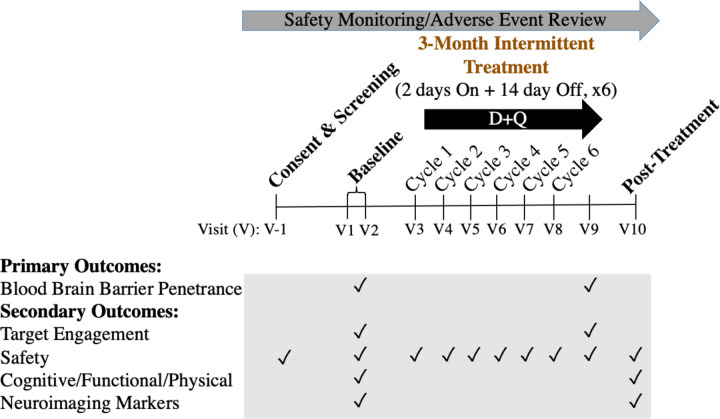

As previously described28, the study protocol included completion of 11 study visits over a period of 20 to 24 weeks (Figure 1). Following obtainment of written informed consent, study candidates completed an in-person screening visit consisting of a blood draw, vital signs, anthropomorphic measurements, physical and neurological examination, medical history and concomitant medication reviews, cognitive screening assessments (CDR30 and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)31), and electrocardiogram (ECG). Following confirmation of study eligibility, participants completed two baseline assessment visits consisting of a fasting blood draw and lumbar puncture (Baseline Visit 1) and assessments of cognition, functional status, and an optional brain MRI (Baseline Visit 2). In response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the protocol was modified to include confirmation of a negative real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test within 72 hours of the first study drug administration, and COVID-19 symptom and exposure screenings were conducted across the study. The first study drug administration visit occurred within 3 to 10 days of the second baseline visit. Study drugs, 100mg of D (one 100mg capsule, Sprycel, Bristol Meyers Squibb) and 1000mg of Q (four 250 mg capsules, Thorne Research) were administered consecutively for two days followed by a 13- to 15-day study drug holiday across a total of six cycles (IND #143945). On the first day of each cycle, participants reported to the study site for safety assessments and drug dispensing. Within 80 to 150 minutes of the administration of final study drug dose, participants underwent a fasting blood draw and lumbar puncture. The assessment procedures administered at Baseline Visit 2 were repeated within 3–10 days of the final study drug dose. D+Q were administered under IND # 143945–0006 (to N.M).

Figure 1:

Study Design and Timeline. Modified from Gonzales et al., 202128. Primary outcomes were to assess blood-brain barrier penetrance of the senolytic drugs Dasatinib (D) and Quercetin (Q) (D+Q). Secondary outcomes explored target engagement, safety, functional outcomes and neuroimaging markers.

Safety and Adherence:

Vital signs, concomitant medications, and adverse events were reviewed at each study visit. Safety labs, including complete blood count (CBC) with differentials and comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) with liver and lipid panels, were conducted at Visits 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 9. Prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time/international normalized ratio (PT/PTT/INR) was assessed at Visits 1 and 8 and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was evaluated at Visits 1 and 9. Electrocardiogram was conducted at Visits 1, 4, 6, 8, and 11. The study was monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board, who reviewed the safety data on an annual basis. Adherence was assessed by the total number of doses completed, counted by administrations in clinic, home diary records, and pill bottle review.

Cognitive and Functional Outcomes:

The pre-specified cognitive outcomes of interest were pre-to post-treatment changes on the MoCA31 and CDR Sum of Boxes (SOB)30. Additional cognitive assessments included the Weschler Memory Scale Fourth Edition (WMS-IV) Logical Memory32, Benson Figure33, Trail Making Test Parts A&B33, Number Span Test33, Category Fluency34, Phonemic Fluency34, Boston Naming Test35, and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised (HVLT-R)36. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were assessed using the self-reported Geriatric Depression Scale 15-Item (GDS-15) and informant-reported Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)33. Functional status was evaluated using the informant-reported Lawton IADL form37 and as part of the CDR.

Brain MRI:

Brain MRI was conducted at the UTHSCSA Research Imaging Institute on a 3-Tesla Siemens Trio scanner. The imaging protocol consisted of a localizer scan, high-resolution 3-dimensional T1-weighted structural series scan, a T2-weighted fluid attention inversion recovery (FLAIR) scan, a diffusion-weighted scan, and a gradient echo scan. Pre- and post-treatment structural scans were spatially coregistered using rigid-body registration, followed by nonlinear registration and multi-atlas based neuroanatomic parcellation, 38–40 to quantify total brain and hippocampal volume and grey and white matter density normalized to intracerebroventricular volume (ICV) from four of the five study participants.

Blood Draws and Lumbar Punctures:

Blood plasma and CSF samples for research purposes were collected according to established procedures41. Briefly, blood was collected under fasting conditions via venipuncture in a plasma EDTA vacutainer tube (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ), inverted 5–10 times, and centrifuged at 2000 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80°C within 2 hours of collection. CSF was also collected under fasting conditions using a 24-gauge atraumatic Sprotte spinal needle under gravity flow (Teleflex, Morrisville, NC). CSF was collected into a sterile polypropylene tube (Rose Scientific, Alberta, CA), which was centrifuged at 2000 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature. CSF was aliquoted and stored at −80°C within 2 hours of collection.

Assays

Drug Concentrations:

Pre- and post-treatment D and Q concentrations in blood and CSF were quantified via High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Tandem Mass Spectrometry detection (MS/MS) method (HPLC/MS/MS) at the UTHSCSA Biological Psychiatry Analytical Lab. Analytical solutions were prepared with Milli-Q Plus water (Millipore Sigma, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). D and Q analytical standards were obtained from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) and their metabolites (dasatinib n-oxide and 4-o-methyl quercetin) and internal standards (IS) from Cayman (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). All other chemicals were HPLC analytical grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Tandem mass spectrometry was performed using a Shimadzu 8045 Triple Quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc., Houston, TX). The lower limit of detection (LOD) was estimated to be 0.3 ng/ml for D, Q, and their metabolites in plasma and CSF, except for D in CSF, which was estimated to be 0.025 ng.ml. The lower limit of quantitation (LOQ) for D, Q and their metabolites was estimated to be 1.0 ng.ml, except for D in CSF which was estimated to be 0.2 ng/ml.

Markers of Cellular Senescence and SASP:

The Mesoscale Discovery U-Plex Biomarker Group 1 (hu) 71-plex panel (MesoScale Discovery, Natickm MA) was used to measure IL-6, a prespecified secondary outcome, and additional cytokines and chemokines in CSF and plasma. Samples were diluted and measured in duplicate, as per the manufacturer’s protocol. A MESO QuickPlex SQ 120MM instrument was used to measure the concentration of each marker.

ADRD Biomarkers:

A Simoa HD-X analyzer (Quanterix, Lexington, MA) was used to measure phosphorylated tau (p-Tau) 181 (SIMOA pTau-181 Advantage V2 kit, Quanterix, Lexington, MA), Aβ40, Aβ42, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light (NFL) (SIMOA Neuro 4-Plex E Advantage kit, Quanterix, Lexington, MA) concentrations in plasma and CSF. The SIMOA pTau-231 Advantage kit (Quanterix, Lexington, MA) was used to measure pTau 231 concentration in CSF. Prior to loading the samples onto the Simoa analyzer, plasma and CSF samples were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 x g for 10 minutes. All samples were run in duplicate. In addition, a Fujirebio G1200 (Malvern, PA) was used to measure total tau (lumipulse G total tau, Malvern, PA), pTau-181 (lumipulse G pTau-181, Malvern, PA) Aβ40 (lumipulse G B-Amyloid 1–40, Malvern, PA), and Aβ42 (lumipulse G B-Amyloid 1–42, Malvern, PA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive analyses were performed on baseline demographic and broader sample characteristics. Baseline to post-treatment changes in safety labs, vitals and body mass index (BMI), cognitive and functional assessment, neuroimaging outcomes, and biofluid markers were assessed using paired samples t-tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0. Statistical tests were 2-sided and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Given the exploratory nature of the pilot study, p-values were not corrected for multiple comparisons unless otherwise noted in the text.

Results:

Participants:

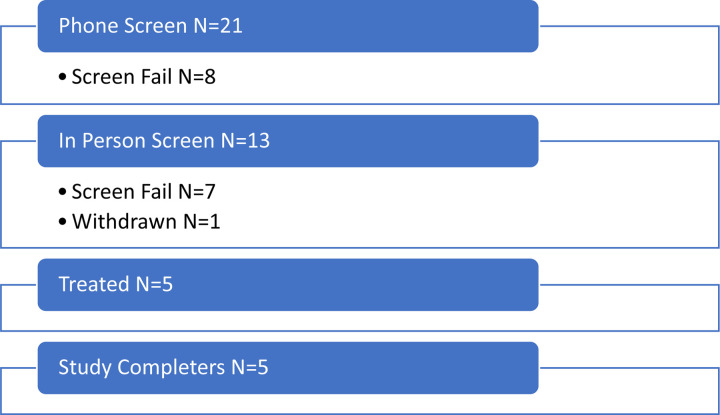

A total of 21 participants were screened over the phone, eight of whom did not meet the eligibility criteria (Figure 2). Thirteen participants completed the in-person screening visit and of those, seven were screen failures and one withdrew. Five participants (aged 70–82 years; median 76; 40% female; 80% Non-Hispanic White; 20% Hispanic) enrolled in the intervention. Regarding highest level of educational attainment, two participants (40%) had high school diplomas, one (20%) had some college, and two participants (40%) had college degrees or higher.

Figure 2:

CONSORT Flow Diagram. Participant allocation in the open-label pilot study.

Safety and Adherence:

A total of six adverse events (AEs) occurred during the course of the study, of which three (two mild: diarrhea and emesis, urinary tract infection, one moderate: hypoglycemia) occurred following the start of the intervention. The two mild AEs were deemed unlikely related to the study and the one moderate AE, hypoglycemia, was deemed possibly related to the intervention. Prior to the start of the intervention, there was one moderate severity AE (fall resulting in hematoma) and two mild AEs (hematuria, diarrhea). All AEs fully resolved within one to 16 days.

There were no significant changes in BMI (pre-treatment: 23.0±4.3 mg/k2; post-treatment: 22.7±4.2 mg/kg2, t(4)=−1.12, p=0.32), systolic blood pressure (pre-treatment: 114.4±11.8 mmHg; post-treatment: 120.4±16.7 mmHg, t(4)=0.56, p=0.61) or diastolic blood pressure (pre-treatment: 63.8±14.3 mmHg; post-treatment: 67.4±9.2 mmHg, t(4)=0.96, p=0.39).

There was a statistically significant, but not clinically significant, increase in total cholesterol from pre- to post-treatment (pre-treatment: 169.2±35.5 mg/dl; post-treatment: 179.4±40.0 mg/dl, t(4)=2.904, p=0.044). No other significant changes in safety lab parameters were observed (Supplementary Table 1).

All five participants who enrolled in the intervention completed the trial with a 100% study drug adherence rate.

Study Drug Concentrations:

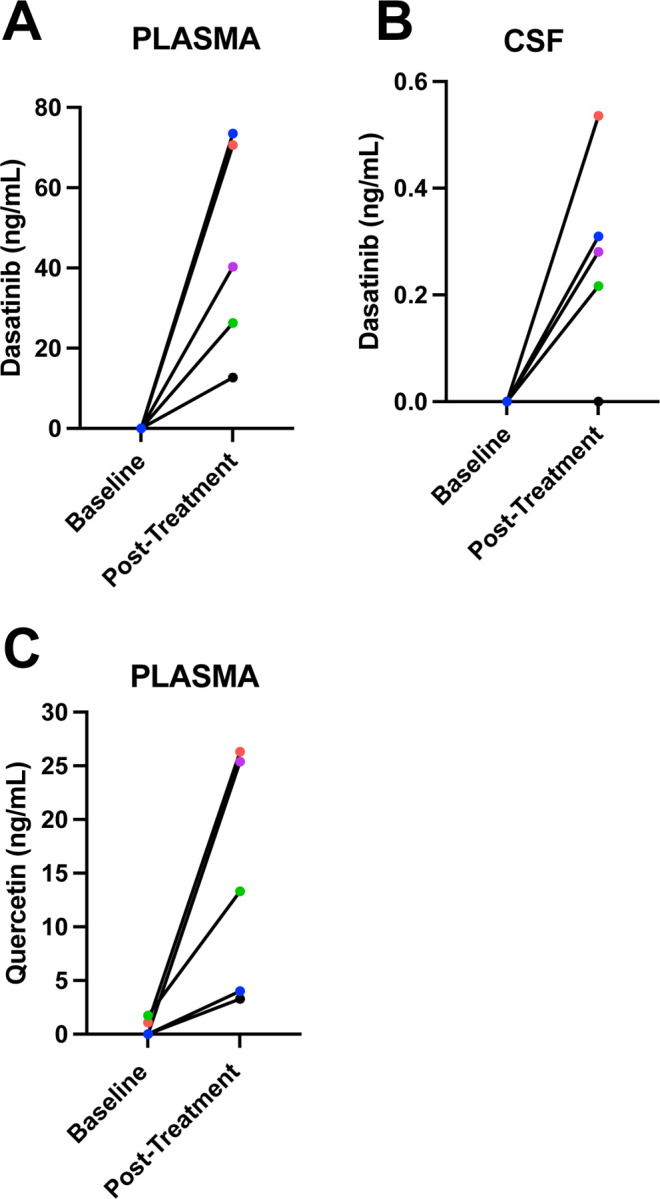

As expected, D was not present in plasma or CSF prior to treatment (Figure 3A-B). After the intervention, D was detected in plasma in all five participants, ranging from 12.7 to 73.5 ng/ml. In CSF, post-treatment D levels were slightly above the LOQ (0.2 ng/ml) in four out of five participants, ranging from 0.281 to 0.536 ng/ml, and the fifth had no detectable levels. In the four participants with detection of D in CSF, the CSF to plasma ratio of D concentrations ranged from 0.004 to 0.008. D metabolites were undetected in both plasma and CSF with the exception of one post-treatment plasma specimen, 1.94 ng/ml (LOQ 1.0 ng/ml; metabolite data not shown).

Figure 3:

Concentration of D (Post-Treatment) and Q (Pre- and Post-Treatment) concentrations in blood and CSF quantified by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Tandem Mass Spectrometry detection (MS/MS) method (HPLC/MS/MS).

Q is found in many fruits and vegetables42,43. In plasma at baseline, three participants had no detectable Q levels and the other two had concentrations of 1.09 and 1.73 ng/ml (LOQ 1.0 ng/ml). However, the two participants that had Q levels just above the LOQ at baseline had Q concentrations of 26.3 and 13.3 ng/ml post-treatment. Following treatment, Q was detected in plasma across participants, ranging from 3.29–26.30 ng/ml (Figure 3C). Within CSF, Q was not detected either before or after treatment across participants. Q metabolites were detected only in two post-treatment plasma specimens, 2.92 and 3.80 ng/ml (LOQ 1.0 ng/ml) and one post-treatment CSF sample, 1.23 ng/ml (LOQ 1.0 ng/ml; metabolite data not shown). Within CSF, Q was not detected either before or after treatment across participants.

Cognitive and functional outcomes:

Baseline to post-treatment changes in the pre-specified cognitive outcomes, MoCA and CDR SOB, were not significant (Table 1). There was a statistically significant decrease on HVLT-R Immediate Recall. All other cognitive tests, as well as questionnaires assessing neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional status, did not demonstrate any significant changes.

Table 1:

Baseline and Post-Treatment Cognitive and Functional Status Assessments

| Cognitive Test | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post-Treatment Mean (SD) | T-test(df), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoCA | 16.2 (2.9) | 16.0 (1.1) | t(4)=−0.196, p=0.85 |

| CDR Sum of Boxes | 5.30 (2.2) | 5.60 (2.0) | t(4)=2.449, p=0.070 |

| HVLT-R Immediate Total Recall | 13.80 (4.4) | 10.20 (4.6) | t(4)=−3.674, p=0.021* |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 0.60 (0.9) | 0.40 (0.9) | t(4)=−1.000, p=0.37 |

| WMS Logical Memory Immediate Recall | 12.6 (6.5) | 13.2 (1.9) | t(4)=0.220, p=0.84 |

| WMS Logical Memory Delayed Recall | 14.2 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.8) | t(4)=−1.633, p=0.18 |

| Benson Figure Copy | 8.60 (6.2) | 14.6 (2.5) | t(4)=2.390, p=0.075 |

| Benson Figure Delayed Recall | 0.80 (1.5) | 2.50 (3.1) | t(4)=2.049, p=0.13 |

| Number Span Forward | 6.40 (1.8) | 6.80 (1.6) | t(4)=0.784, p=0.48 |

| Number Span Backward | 4.60 (1.7) | 4.80 (1.3) | t(4)=0.343, p=0.75 |

| Trails A, Time to Completion (Seconds) | 76.0 (35) | 99.0 (71) | t(4)=1.137, p=0.32 |

| Trails B, Time to Completion (Seconds) | 208 (86) | 212 (84) | t(4)=0.829, p=0.45 |

| Phonemic Fluency (F,A,S) | 32.0 (5.8) | 31.4 (5.5) | t(4)=−0.187, p=0.86 |

| Semantic Fluency (Animals) | 9.80 (1.3) | 11.0 (3.2) | t(4)=1.124, p=0.32 |

| Lawton IADL | 11.0 (4.9) | 10.4 (5.3) | t(4)=−0.612, p=0.57 |

| GDS-15 | 4.00 (3.1) | 3.60 (2.4) | t(4)=−0.459, p=0.67 |

| NPI | 5.40 (7.7) | 3.80 (4.8) | t(4)=−0.758, p=0.49 |

Note: Baseline to post-treatment changes were assessed using paired samples t-tests. MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment, CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale, HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised, WMS = Weschler Memory Scales, Trails = Trail Making Test, IADL = Independent Activities of Daily Living, ADL = Activities of Daily Living, GDS-15 = Geriatric Depression Scale 15-Item, NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory,

p<0.05

Neuroimaging:

Paired t-tests of pre- versus post-treatment MRIs revealed no significant differences in total brain volume, gray matter or white matter density, or right or left hippocampal volume, indicative of stable brain morphology over the three-month assessment period (Table 2).

Table 2:

Baseline and Post-Treatment Neuroimaging Outcomes

| Brain Region (voxels) | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post-Treatment Mean (SD) | T-test(df), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracerebroventricular Volume (ICV) | 1393962.33 (151287.55) | 1393461.27 (149379.55) | t(3)=0.150, p=0.89 |

| Total Brain Volume/ICV | 0.856 (0.005) | 0.851 (0.009) | t(3)=1.732, p=0.18 |

| Grey Matter Volume/ICV | 0.359 (0.021) | 0.359 (0.015) | t(3)=0.522, p=0.64 |

| White Matter Volume/ICV | 0.452 (0.006) | 0.446 (0.009) | t(3)=1.192, p=0.32 |

| Right Hippocampus Volume/ICV | 0.002 (0.00016) | 0.0002 (0.00013) | t(3)=0.472, p=0.67 |

| Left Hippocampus Volume/ICV | 0.002 (0.00008) | 0.002 (0.00012) | t(3)=0.313, p=0.77 |

Note: Baseline to post-treatment changes were assessed using paired samples t-tests. Brain regions normalized to intracerebroventricular volume (IVC) measured in voxels, p<0.05.

Markers of Cellular Senescence and SASP:

Applying the unadjusted p<0.05 cut-off, plasma levels of IL-17E, IL-21, IL-23, IL-17A/F, IL-17D, IL-10, VEGF, IL-31, MCP-2, MIP-1β and MIP-1α decreased from pre- to post-treatment, whereas YKL-40 levels increased. In CSF, TARC, IL-17A, I-TAC, Eotaxin-2, Eotaxin, and MIP-1α levels decreased, and IL-6 levels increased from pre- to post-treatment (Table 3

Table 3:

Significantly Differentially Expressed Proteins in Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid from Baseline to Post-Treatment

| Protein (pg/mL) | Baseline Mean (SD) | Post-Treatment Mean (SD) | Fold Change | T-test(df), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ||||

| *IL6 | 1.30 (0.54) | 1.58 (0.81) | 1.22 | t(4)= 1.651, p=0.145 |

| IL-17E | 25.2 (20.3) | 17.0 (14.5) | 0.67 | t(4)= −5.216, p=0.0014 |

| IL-21 | 166 (96.7) | 102 (72.1) | 0.62 | t(4)=−4.714, p=0.002 |

| IL-23 | 53.4 (29.5) | 34.0 (25.4) | 0.64 | t(4)=−4.345, p=0.003 |

| IL-17A/F | 35.4 (12.8) | 23.1 (12.7) | 0.65 | t(4)=−3.870, p=0.007 |

| IL-17D | 67.7 (25.5) | 49.0 (17.9) | 0.72 | t(4)=−3.384, p=0.013 |

| IL-10 | 0.31 (1.0) | 0.21 (0.20) | 0.66 | t(4)=−3.347, p=0.013 |

| VEGF | 20.8 (6.0) | 12.5 (3.4) | 0.60 | t(4)=−3.238, p=0.015 |

| YKL-40 | 58047 (60143) | 105444 (127256) | 1.82 | t(4)=3.017, p=0.020 |

| IL-31 | 67.5 (27.9) | 54.8 (28.9) | 0.81 | t(4)=−2.914, p=0.024 |

| MCP-2 | 23.5 (5.1) | 18.5 (4.5) | 0.79 | t(4)=−2.806, p=0.028 |

| MIP-1β | 48.5 (16.1) | 36.9 (25.8) | 0.76 | t(4)=−2.515, p=0.042 |

| MIP-1α | 24.3 (1.6) | 19.6 (4.7) | 0.81 | t(4)=−2.433, p=0.047 |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid | ||||

| *IL-6 | 1.16 (0.32) | 1.55 (0.23) | 1.34 | t(4)=3.913, p=0.008 |

| TARC | 1.42 (0.42) | 1.25 (0.38) | 0.87 | t(4)=−3.099, p=0.021 |

| IL-17A | 0.54 (0.13) | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.60 | t(4)=−2.753, p=0.033 |

| I-TAC | 4.15 (1.2) | 3.36 (1.1) | 0.81 | t(4)=−2.736, p=0.033 |

| Eotaxin-2 | 14.5 (6.5) | 12.8 (5.3) | 0.89 | t(4)=−2.630, p=0.038 |

| Eotaxin | 16.9 (4.9) | 14.7 (4.3) | 0.87 | t(4)=−2.534, p=0.044 |

| MIP-1α | 19.0 (2.4) | 14.3 (4.8) | 0.75 | t(4)=−2.471, p= 0.048 |

Note: Differential expression analysis was carried out by the moderated t-test

Prespecified secondary outcome

IL = interleukin, MIP = Macrophage Inflammatory Protein, G-CSF = Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor, TRAIL = Tumor Necrosis Factor Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand, TARC = Thymus- and Activation-Regulated Chemokine, p<0.05

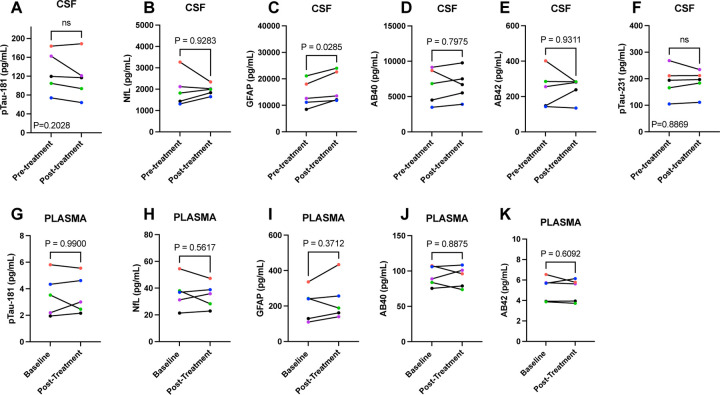

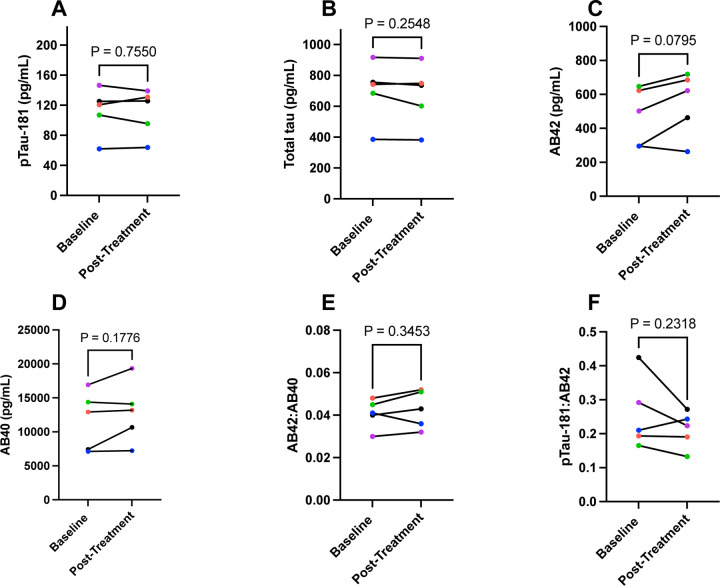

ADRD Biomarkers:

Using the SIMOA assays, there were no pre- to post-treatment changes in plasma or CSF protein levels with the exception of a significant increase of GFAP levels in CSF (Figure 4A-K). For the Lumipulse assays, no significant treatment changes were observed in CSF; however, there was a trend (p=0.0795) towards higher Aβ42 levels post-treatment (Figure 5A-F).

Figure 4:

Baseline and Post-Treatment Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers Assessed Using the Simoa HD-X Analyzer. Values derived from paired samples t-test and p-value of 0.05.

Figure 5:

Baseline and Post-Treatment Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers Assessed Using the Lumipulse. Values derived from paired samples t-test and p-value of 0.05

Discussion

Cellular senescence has been associated with neurodegenerative disease in human pathology studies and preclinical models6,7,18,19. Herein, we present the results of the first-in-human trial of senolytic therapy for AD28. The primary aim of our open-label pilot study was to evaluate the CNS penetrance of first-generation senolytics, D and Q. Our results confirmed the presence of D in CSF following treatment. In addition, the intervention was well-tolerated with no premature discontinuation and only three AEs occurring following treatment initiation. Our study was not designed or powered to detect efficacy. However, our preliminary data suggests the potential of baseline to post-treatment changes in markers of cellular senescence and ADRD, which will require further exploration and validation in randomized placebo-controlled trials that are presently underway (NCT04685590).

A primary challenge to conducting trials for AD and other neurological diseases is the determination of the appropriate drug dosing as assessing pharmacokinetics in the CNS is highly invasive. In our study, we selected the combination of D and Q as they are among the best characterized senolytic agents, target multiple SCAP pathways, and are repurposed8,25, expediting clinical testing. The doses and intermittent scheduling regimen were selected based on prior research demonstrating safety and early indications of efficacy for other disease indications8,26. The intermittent dosing regimen was implemented because senescent cells across organ systems, including the brain, typically accumulate over a period of weeks, suggesting that drugs do not continually need to be present to be effective6,21. Intermittent dosing further reduces potential toxicity. Our study design of in-clinic administrations on the first day of each drug cycle enabled us to carefully monitor participant safety and was likely supportive of our 100% study drug adherence rate. In plasma, D has been shown to reach peak concentrations within two hours of administration44; however, the absorption in the CNS is less well established. Following oral ingestion of D in mice, a prior study reported D in brain homogenates using HPLC/MS at concentrations that were 12- to 31-fold lower than in plasma44. In humans, D has demonstrated efficacy for treating ALL and CML with CNS involvement and responses can be maintained for months to years44, suggesting a robust CNS treatment effect. However, HPLC/MS studies conducted in CSF taken from D-treated individuals with CML or ALL have reported low CSF concentrations and high variability across individuals44,45. Gong et al. examined plasma and CSF concentrations of D among individuals with ALL approximately two hours after a single dose of 100 mg of D45. Detectable D levels in CSF were only observed in 16% of participants (4/25 individuals) with ranges between 0.23 to 0.68 ng/ml. In our study, we observed a similar range of D concentrations in CSF. However, the detectable levels were more readily observed in our population, occurring in 80% (4/5 individuals) of participants. More consistent CSF concentrations may have been observed in our study of individuals with AD due to the disease’s impact on blood brain barrier integrity46. Future pharmacokinetic studies will be helpful for informing on the optimal dosing for desired CNS effects. However, our study demonstrated that D penetrated the CNS and prior research in oncology has shown that the medication can demonstrate CNS efficacy at low or even subnanomolar concentrations44,47.

In our study, Q was consistently detected in plasma across participants. However, unlike D, Q was not detectable in CSF within our sample. In animal model research, oral administration of Q has been shown to reduce oxidative stress in the brain48,49, suggesting a therapeutic effect in the CNS. In a preclinical study of mice that ingested 21.3 grams of Q per day, Q was detectable in brain homogenates assessed using HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry, plateauing after one-week of administration49. In culture, Q has been shown to permeate primary brain microvessel endothelial cells and primary astroglia cells50, suggesting blood brain barrier penetrance. However, confirmatory studies in humans are lacking. Q is rapidly metabolized in the human intestinal mucosa and liver and it has low bioavailability51, which may explain why it was not detectable in CSF within our study. There are ongoing efforts to improve the CNS permeability with the use of nanoparticles and/or chemical modification49. Further pharmacokinetic studies of Q in humans are warranted.

As the first-in-human clinical trial of senolytic therapy for AD, our study also provides important preliminary data on safety, tolerability, and feasibility. Throughout the study, a total of six AEs occurred, of which three emerged after treatment initiation. Two of these AEs were mild and highly common in the study population. Hypoglycemia was observed in one participant. D has been associated with changes in glucose regulation with reports of both hyper- and hypoglycemia emerging52,53. It has been hypothesized that the responses may differ depending on age, genetics, and comorbidity burden53. Without larger sample sizes and a placebo group, we are unable to determine if hypoglycemia occurred more frequently in the active treatment arm. Regular assessments of glucose levels in future trials may be helpful for further clarification. Clinical safety labs were generally stable from baseline to post-treatment. Only one statistically significant change emerged, which was an increase in total cholesterol levels. However, cholesterol levels remained in the normative range. A prior retrospective study conducted in adults with CML and normal baseline glucose-lipid levels suggested that D may cause mild increases in glucose, triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol levels53. In contrast to the typical treatment of CML, the intermittent dosing approach used in this trial may have helped to attenuate metabolic changes.

Our study was not powered to examine target engagement, but instead designed to collect exploratory data on baseline to post-treatment changes in markers of cellular senescence and SASP both in CSF and blood. Change in IL-6 was a prespecified secondary outcome. The analyses revealed a statistically significant elevation of IL-6 in CSF after treatment. Plasma levels modestly increased, but did not reach statistical significance. The treatment-induced changes in IL-6 may reflect senescent cell apoptosis whereby IL-6 was directly released from senescent cells upon their lysis; alternatively, apoptosis may have initiated an immune response to clear the cellular debris. Recognizing that IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine, we simultaneously performed a broader evaluation of cytokines and chemokines to better infer the treatment effect. CSF analyses indicated baseline to post-treatment decreases in adaptive immunity markers, TARC, IL-17A, I-TAC, Eotaxin and Eotaxin-2; and chemokine, MIP-1α. A similar pattern was observed in plasma whereby treatment was associated with a decrease in adaptive immunity markers IL-23, IL-21, IL-17, IL-31, and VEGF54; and chemokines, MIP-1α and MIP-1β. Given that senescent cells secrete these molecules as SASP factors, the observed reduction support a decrease in senescent cell burden post-treatment. While the majority of markers displayed reductions from pre- to post-treatment, there was variability. It is important to highlight that none of the markers would have withstood multiple comparisons correction, and the preliminary findings require further replication in studies designed to assess this endpoint.

Consistent with AD trials, our study also acquired cognitive and neuroimaging measures. Baseline to post-treatment changes were not observed for our pre-specified cognitive endpoints, the MoCA and CDR SOB. The null findings are not surprising as our trial was not designed to evaluate efficacy and included a small sample size and short duration of treatment. Prior studies in AD suggest that study durations of 18-months are required to observe decline in placebo groups55, providing a framework for trial lengths to assess efficacy. In our exploratory assessment of the broader cognitive battery, baseline to post-treatment performances were stable. There was a statistically significant decrease on a verbal learning measure (HVLT-R), however, without a control group, we are unable to compare the findings relative to the natural neurodegenerative disease course. Regarding neuroimaging outcomes, there were not significant changes in total brain volume, hippocampal volume, or gray matter or white matter density from baseline to post-treatment. While our study was underpowered and of insufficient duration to provide a comprehensive evaluation of neuroimaging outcomes, we consider the absence of changes to indicate a favorable safety profile of senolytic treatment. The data further underscore the need for randomized clinical trials designed to evaluate these metrics.

As a secondary outcome, our study also evaluated key ADRD biomarkers in both plasma and CSF at baseline and post-treatment. There were no significant changes in plasma biomarkers, which was anticipated given the small sample size and short follow-up period. In CSF, we observed a significant increase in GFAP levels from baseline to post-treatment. CSF GFAP levels are presumed to reflect reactive astrogliosis56 and demonstrate elevations early in the neurodegenerative disease process57. In our study, it is unclear if increases in GFAP reflect or an acute response to treatment. Coupled with the elevated CSF IL-6 data, it is tempting to speculate that the concomitant increase in GFAP may reflect apoptosis of senescent astrocytes. Supporting evidence for this would require additional blood and CSF collections, weeks or months after the end of treatment, to determine if increased GFAP and IL-6 were transient or sustained responses to senolytic treatment. Our preclinical trial of D+Q reported 35% fewer insoluble NFTs in the treatment arm relative to placebo6, which may have reflected a reduction in tangle formation and/or an increase in tau clearance. In our study, we did not observe changes in total tau, p-tau-181, or p-tau-231, however, the study was not powered to assess these outcomes. On-going efforts by our team are focused on a more comprehensive analyses of phospho-tau in CSF and post-mortem human brain to identify which tau species best reflect senescence. The results from the Lumipulse assay, but not from the SIMOA assay showed a trend towards increased post-treatment Aβ42 levels. If replicated in well-powered studies designed to assess efficacy, the findings could suggest the possibility of disease modification with senolytic treatment.

While our study provides the first report of senolytic treatment in humans with AD, there are several important limitations that must be considered. First, our study was designed to evaluate the CNS penetrance of D and Q. Therefore, it was not powered to assess outcomes related to target engagement, cognition, or disease modification. The short trial duration and lack of a placebo group place further restrictions on interpreting these outcomes. Another limitation is the lack of established senescence and SASP markers related to AD. Prior studies have reported that biomarkers of cellular senescence vary significantly across cell types and inducers58,59. Therefore, further work is necessary to identify clinically meaningful markers of cellular senescence in AD across specimen types, and is under investigation by our team. Our exploratory findings provide initial data on changes in protein levels following senolytic treatment in older adults with AD, but validation and replication in well-powered randomized controlled studies are critical for advancing therapeutic discovery in the field.

In summary, we report findings from the first clinical trial of senolytic therapy for AD. In alignment with our primary study aim, we identified support for the CNS penetrance of D, although Q was not detectable in CSF. In our study, the treatment was well-tolerated with excellent adherence to the study drug regimen. Broader assessments of target engagement and treatment-related outcomes were assessed to provide early feasibility data. While our study was not designed to evaluate efficacy, the data suggests the potential of treatment-related changes in markers of cellular senescence and AD pathology. Our vanguard study provides initial data on the safety, tolerability, and feasibility of senolytic therapy for AD. While early results are promising, fully powered, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies are needed to evaluate the safety and potential for disease modification with the novel approach of targeting cellular senescence in AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments/Funding:

We thank the volunteers in this study and the research staff who conducted recruitment and assessments. This work was made possible by grants through the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, GC-201908–2019443 (PI: Orr), the Coordinating Center for Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers, U24AG059624; the Translational Geroscience Network (R33AG061456); and the Institute for Integration of Medicine & Science and the Center for Biomedical Neurosciences at UT Health Science Center in San Antonio (UTHSCSA). Dr. Gonzales was supported as an RL5 Scholar in the San Antonio Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG044271) and is also supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG077472 and P30AG066546). Dr. Garbarino is supported by T32AG021890 and TR002647. Dr. Palavicini is supported by the San Antonio Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (RL5 Scholar, P30AG044271), the American Federation of Aging Research, and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund. Dr. Zhang was supported by National Institute on Aging (U01AG046170, R01AG068030). Dr. Musi also is supported by P30AG044271 and the San Antonio Nathan Shock Center (P30AG013319). Dr. Seshadri is supported by the National Institute on Aging (AG054076 and AG059421). Dr. Orr is supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (I01BX005717), National Institute on Aging (R01AG068293, R01AG065839, U54AG079754, R24AG073199), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21NS125171) and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional Declarations: Yes is potential Competing Interest. Dr. Gonzales reports personal stock in Abbvie. Dr. Petersen reports personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Biogen, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Genentech, outside the submitted work. Drs. Kirkland and Tchknoia have a patent Killing Senescent Cells and Treating Senescence-Associated Conditions Using a SRC Inhibitor and a Flavonoid with royalties paid to Unity Biotechnologies, and a patent Treating Cognitive Decline and Other Neurodegenerative Conditions by Selectively Removing Senescent Cells from Neurological Tissue with royalties paid to Unity Biotechnologies. Dr. Craft reports other from vTv Therapeutics, other from Cylcerion, other from T3D Therapeutics, from Cognito Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Dr. Orr has a patent Biosignature and therapeutic approach for neuronal senescence pending.

References

- 1.Prince M. J. et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015-The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. (2015).

- 2.Cummings J., Ritter A. & Zhong K. Clinical trials for disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a primer, lessons learned, and a blueprint for the future. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 64, S3–S22 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aisen P. S. et al. The future of anti-amyloid trials. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 7, 146–151 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haass C. & Selkoe D. If amyloid drives Alzheimer disease, why have anti-amyloid therapies not yet slowed cognitive decline? PLoS biology 20, e3001694 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korczyn A. D. Mixed dementia—the most common cause of dementia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 977, 129–134 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musi N. et al. Tau protein aggregation is associated with cellular senescence in the brain. Aging cell 17, e12840 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehkordi S. K. et al. Profiling senescent cells in human brains reveals neurons with CDKN2D/p19 and tau neuropathology. Nature Aging 1, 1107–1116 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkland J. L. & Tchkonia T. Cellular senescence: a translational perspective. EBioMedicine 21, 21–28 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Deursen J. M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 509, 439–446, doi: 10.1038/nature13193 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kritsilis M. et al. Ageing, cellular senescence and neurodegenerative disease. International journal of molecular sciences 19, 2937 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma V., Gilhotra R., Dhingra D. & Gilhotra N. Possible underlying influence of p38MAPK and NF-κB in the diminished anti-anxiety effect of diazepam in stressed mice. Journal of pharmacological sciences 116, 257–263 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acosta J. C. et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nature cell biology 15, 978–990 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurk D. et al. Postmitotic neurons develop a p21-dependent senescence-like phenotype driven by a DNA damage response. Aging Cell 11, 996–1004, doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00870.x (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riessland M. et al. Loss of SATB1 Induces p21-Dependent Cellular Senescence in Post-mitotic Dopaminergic Neurons. Cell Stem Cell 25, 514–530 e518, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.013 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhat R. et al. Astrocyte senescence as a component of Alzheimer’s disease. (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chinta S. J. et al. Cellular Senescence Is Induced by the Environmental Neurotoxin Paraquat and Contributes to Neuropathology Linked to Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Rep 22, 930–940, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.092 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streit W. J. & Xue Q.-S. Human CNS immune senescence and neurodegeneration. Current opinion in immunology 29, 93–96 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bussian T. J. et al. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature 562, 578–582 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang P. et al. Senolytic therapy alleviates Aβ-associated oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nature neuroscience 22, 719–728 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant A. G. et al. Cerebrovascular senescence is associated with tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in neurology 11, 575953 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y. I. et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging cell 14, 644–658 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindauer M. & Hochhaus A. Dasatinib. Small Molecules in Oncology, 27–65 (2014).

- 23.Boots A. W., Haenen G. R. M. M. & Bast A. Health effects of quercetin: from antioxidant to nutraceutical. European journal of pharmacology 585, 325–337 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogrodnik M. et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat Commun 8, 15691, doi: 10.1038/ncomms15691 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tchkonia T. & Kirkland J. L. Aging, cell senescence, and chronic disease: emerging therapeutic strategies. Jama 320, 1319–1320 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Justice J. N. et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine 40, 554–563 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickson L. J. et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 47, 446–456 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzales M. M. et al. Senolytic Therapy to Modulate the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease (SToMP-AD): A Pilot Clinical Trial. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 9, 22–29, doi: 10.14283/jpad.2021.62 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jack C. R. Jr et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia 7, 257–262 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris J. C. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International psychogeriatrics 9, 173–176 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasreddine Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53, 695–699 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corporation, P. WMS-IV: Wechsler Memory Scale 4th Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual. (Harcourt, Brace, & Company, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub S. et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23, 91–101, doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tombaugh T. N., Kozak J. & Rees L. Normative data stratified by age and education for two measures of verbal fluency: FAS and animal naming. Archives of clinical neuropsychology 14, 167–177 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan E., Goodglass H. & Weintraub S. Boston naming test. (2001).

- 36.Benedict R. H. B., Schretlen D., Groninger L. & Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 12, 43–55 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graf C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale. The gerontologist 9, 179–186 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doshi J. et al. MUSE: MUlti-atlas region Segmentation utilizing Ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters, and locally optimal atlas selection. Neuroimage 127, 186–195, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.073 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivasan D. et al. A comparison of Freesurfer and multi-atlas MUSE for brain anatomy segmentation: Findings about size and age bias, and inter-scanner stability in multi-site aging studies. Neuroimage 223, 117248, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117248 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Habes M. et al. The Brain Chart of Aging: Machine-learning analytics reveals links between brain aging, white matter disease, amyloid burden, and cognition in the iSTAGING consortium of 10,216 harmonized MR scans. Alzheimers Dement 17, 89–102, doi: 10.1002/alz.12178 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcock D. et al. MarkVCID cerebral small vessel consortium: I. Enrollment, clinical, fluid protocols. Alzheimers Dement 17, 704–715, doi: 10.1002/alz.12215 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scalbert A. & Williamson G. Dietary Intake and Bioavailability of Polyphenols. The Journal of Nutrition 130, 2073S–2085S, doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.2073S (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwashina T. Flavonoid properties of five families newly incorporated into the order Caryophyllales. Bull Natl Mus Nat Sci 39, 25–51 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porkka K. et al. Dasatinib crosses the blood-brain barrier and is an efficient therapy for central nervous system Philadelphia chromosome–positive leukemia. Blood 112, 1005–1012, doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140665 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gong X. et al. A Higher Dose of Dasatinib May Increase the Possibility of Crossing the Blood–brain Barrier in the Treatment of Patients With Philadelphia Chromosome–positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clinical Therapeutics 43, 1265–1271.e1261, doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.05.009 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erickson M. A. & Banks W. A. Blood–brain barrier dysfunction as a cause and consequence of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 33, 1500–1513 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Hare T. et al. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistant Abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer research 65, 4500–4505 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun S. W. et al. Quercetin attenuates spontaneous behavior and spatial memory impairment in d-galactose–treated mice by increasing brain antioxidant capacity. Nutrition Research 27, 169–175 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishisaka A. et al. Accumulation of orally administered quercetin in brain tissue and its antioxidative effects in rats. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 51, 1329–1336, doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.017 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren S. C. et al. [Quercetin permeability across blood-brain barrier and its effect on the viability of U251 cells]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 41, 751–754, 759 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wróbel-Biedrawa D., Grabowska K., Galanty A., Sobolewska D. & Podolak I. A Flavonoid on the Brain: Quercetin as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Central Nervous System Disorders. Life 12 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundholm M. D. & Charnogursky G. A. Dasatinib-induced hypoglycemia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clinical Case Reports 8, 1238–1240, doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2901 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu L., Liu J., Huang X. & Jiang Q. Adverse effects of dasatinib on glucose-lipid metabolism in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in the chronic phase. Scientific Reports 9, 17601, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54033-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banyer J. L., Hamilton N. H., Ramshaw I. A. & Ramsay A. J. Cytokines in innate and adaptive immunity. Reviews in immunogenetics 2, 359–373 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ito K. et al. Understanding placebo responses in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials from the literature meta-data and CAMD database. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 37, 173–183 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamers K. J. B. et al. Protein S-100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), myelin basic protein (MBP) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood of neurological patients. Brain Research Bulletin 61, 261–264, doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(03)00089-3 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benedet A. L. et al. Differences Between Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Levels Across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurology 78, 1471–1483, doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3671 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tuttle C. S. L. et al. Cellular senescence and chronological age in various human tissues: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Cell 19, e13083, doi: 10.1111/acel.13083 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiley C. D. et al. Analysis of individual cells identifies cell-to-cell variability following induction of cellular senescence. Aging Cell 16, 1043–1050, doi: 10.1111/acel.12632 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.