Abstract

At visit 3 (1993-95) of the ARIC Study, 1.5T brain MRI was completed in 1881 stroke-free participants (Mean age=62.9±4.9, 50% Black). Cox regression examined associations between infarct group [infarct-free(referent; n=1611), smaller only(<3 mm; n=50), larger only(≥3mm but <20mm; n=185), both(n=35)] and up to 25-year incident dementia (n=539). Participants with both infarcts were over 2.5 times more likely to develop dementia [HR=2.61; 95%CI=1.44, 4.72]. Smaller only (HR=1.22; 95%CI=0.70, 2.13) and larger only (HR=1.27; 95%CI=0.92, 1.74) groups showed associations with wide confidence intervals, unsupported statistically. A late midlife infarct profile including smaller and larger infarcts may represent particular vulnerability to dementia risk.

Keywords: infarct, dementia, cognition, epidemiology, cerebrovascular disease

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral small vessel diseases (CSVD), including subclinical infarcts, are increasingly recognized as risk factors for dementia, although most studies investigating this relationship have done so in older adult samples.[1–3] Prevalence of CSVD increases with age,[4] but is not entirely absent in midlife individuals, which is now recognized as a critical early period in the decades-long pathogenesis of dementia, whether attributed to Alzheimer’s or vascular etiology.[5, 6] Earlier markers of subtle cerebrovascular changes, including those seemingly minor enough to not warrant immediate clinical recognition, may be key to tracking dementia-related neuropathology early and longitudinally.

Previous investigations in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort suggest that smaller infarcts alone and especially in combination with larger infarcts were associated with higher risk of stroke and stroke mortality.[7] ARIC participants with coexisting smaller and larger subclinical infarcts in midlife also had worse trajectories of cognitive function with age.[8] These studies suggest that the unmeasured presence of smaller infarcts may influence the findings from the existing literature of relations of larger infarcts to adverse outcomes, and that presence of both infarct sizes may represent a particularly ubiquitous cerebrovascular disease threat. Following these previous reports, our objective was to examine associations of late midlife subclinical infarct burden with risk of incident dementia over 25 years in the ARIC study. We hypothesized that participants with both smaller and larger subclinical infarcts at midlife would be at higher risk of dementia compared to those with no infarcts or either infarct size alone.

METHODS

Participants

The ARIC study began in 1987 with 15,792 men and women aged 45-64 recruited from four US communities: Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Jackson, Mississippi. Further details of the study sampling and design have been previously reported.[9] At the third in-person examination (visit 3, 1993-95), ≥55 years old participants at two study sites (Forsyth County, North Carolina and Jackson, Mississippi) were invited to be screened for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study. Of the 2892 participants who were screened, 654 declined to participate, 122 agreed to participate but did not undergo an MRI, 103 were ineligible, 79 did not complete the MRI. Of the 1934 participants with complete MRI data, 46 were excluded from this analysis for prevalent stroke, 4 self-reported race as Asian or American Indian and were excluded due to small numbers, and 3 were excluded for missing infarct data, resulting in an analysis sample of 1881 participants (mean age 62.9±4.9, 40% Male, 50% Black). Characteristics of the analysis sample and all non-included participants at the Forsyth County and Jackson sites at this study visit are presented in eTable 1. Institutional review boards approved the ARIC study at all study sites, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Infarcts

All MRI scans were obtained using 1.5T scanners (General Electric or Picker) producing 5-mm contiguous axial T1, T2, and proton density-weighted images. Infarcts were identified and defined by size and location on T2 and proton density-weighted images. Consistent with recent CSVD research recommendations [10] and previous ARIC investigations [7, 8], “smaller infarcts” were defined as those <3mm on right-to-left or anterior-to-posterior size and “larger infarcts” were defined as those ≥3mm but <20mm. Care was taken to distinguish smaller infarcts from perivascular spaces by considering absence of mass effect and hyperintensity to gray matter. Late midlife infarct burden was categorized as presence of smaller infarcts only (n=50), presence of larger infarcts only (n=185), presence of both (n=35), or infarct-free (n=1611). Consideration of count of infarcts was only possible for “larger infarcts” and was tabulated as either “Single Larger Infarct” or “Multiple Larger Infarcts” (≥2). In a sensitivity model to consider multi-infarct burden, we used six infarct exposure groups: [infarct-free (referent; n=1611), smaller only (n=50), single larger (n=129), multiple larger (n=56), smaller + single larger (n=17), and smaller + multiple larger (n=18)]. All infarcts were considered subclinical as no participant in the current study had a prevalent stroke history.

Dementia Classification

Details of the ARIC dementia classification protocol have been described previously.[6, 11] All participants were followed prospectively from visit 3 (1993-95; the index visit for this analysis) for incident dementia. From in-person visits 5 to 7 of the study (2011-2019), dementia cases were adjudicated by an expert panel considering their concurrent cognitive performance on a neuropsychological test battery, cognitive measures at previous visits, the Clinical Dementia Rating sum of boxes,[12] and the Functional Activities Questionnaire.[13] Classification was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition).[14] Additional dementia cases were identified between in-person examinations from visit 5 onwards using phone-based assessments. Following visit 5 (2011-13), participants were contacted annually by phone and administered the Six-Item Screener,[15] with informants of low scorers completing the Ascertain Dementia 8-item Informant Questionnaire.[16] Participants who did not attend visits were classified using informant completed CDR and FAQ, and surveillance using hospital discharge codes and death certificate codes retrospectively assessed since the study began.

Covariates

Participant sex, race, and education were self-reported at ARIC visit 1 (1987-89). Covariates measured at visit 3 (1993-95), the index visit for this analysis, included age, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg, or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medication), diabetes (fasting glucose >126 mg/dL, nonfasting glucose > 200 mg/dL, use of diabetes medications, or self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes), smoking status (self-reported current, former, never), alcohol drinking (self-reported current, former, never), total cholesterol (mg/dL). APOE genotyping (TaqMan assay; Applied Biosystems) was done using stored blood samples from visit 1.

Statistical Analysis

The association of infarct burden group [infarct-free (referent), smaller only, larger only, both] with dementia incidence was tested using Cox-proportional hazards regression and reported as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Follow-up time was from the visit 3 MRI scan until dementia, censoring at death, loss to follow-up, or current endpoint of dementia ascertainment (Dec, 31st, 2019). An additional Cox-proportional hazards regression model to examine potential influence of infarct count considered six infarct burden groups [infarct-free (referent), smaller only, single larger, multiple larger, smaller + single larger, and smaller + multiple larger]. All models were adjusted for age, sex, site-race, education, and APOE E4 carrier status. A larger adjuster set additionally included cardiovascular risk factors: BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hypertension, and total cholesterol. All models were repeated including weighting for selection into the V3 MRI sample (see eTable 1) using inverse probability weighting (IPW). Proportional hazards assumptions were examined and not violated.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics at the time of scanning are displayed by infarct group in Table 1. Compared to infarct-free participants, those with infarcts tended to be slightly older, more likely to self-report race as Black, had lower education, and were more likely to smoke, have hypertension, have diabetes, and be APOE E4 carriers. eTable 2 displays the frequency counts of participants in each infarct group who went on to develop dementia, die, drop out of the study, or remain dementia-free through follow-up. Over a mean follow-up of 18.03±7.05 years, 539 dementia cases were identified in the follow-up period.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Infarct Group at ARIC Visit 3 (1993-95)

| Total (N=1881) | Infarct-Free (N=1611) | Smaller Only (N=50) | Larger Only (N=185) | Both (N=35) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), years | 62.8 (4.85) | 62.6 (4.9) | 64.1 (4.3) | 64.6 (4.4) | 64.6 (4.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 748 (40%) | 642 (40%) | 20 (40%) | 70 (38%) | 16 (46%) |

| Black, n (%) | 934 (50%) | 761 (47%) | 33 (66%) | 111 (60%) | 29 (83%) |

| Education, n (%) | |||||

| < High School | 508 (27%) | 408 (25%) | 19 (38%) | 61 (33%) | 20 (61%) |

| High School or equivalent | 639 (34%) | 558 (35%) | 15 (30%) | 58 (31%) | 8 (24%) |

| > High School | 731 (39%) | 644 (40%) | 16 (32%) | 66 (36%) | 5 (15%) |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | |||||

| Current | 341 (18%) | 277 (17%) | 7 (14%) | 44 (24%) | 13 (38%) |

| Former | 693 (37%) | 600 (37%) | 15 (30%) | 67 (37%) | 11 (32%) |

| Never | 835 (45%) | 725 (45%) | 28 (56%) | 72 (39%) | 10 (29%) |

| Alcohol drinking status, n (%) | |||||

| Current | 705 (38%) | 628 (39%) | 11 (22%) | 56 (31%) | 10 (29%) |

| Former | 442 (24%) | 354 (22%) | 16 (32%) | 58 (32%) | 14 (41%) |

| Never | 723 (39%) | 621 (39%) | 23 (46%) | 69 (38%) | 10 (29%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 326 (18%) | 264 (17%) | 12 (24%) | 39 (22%) | 11 (32%) |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) | 27.99 (5.21) | 27.96 (5.20) | 28.05 (4.19) | 28.13 (5.63) | 28.18 (5.01) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 209.2 (38.2) | 209.6 (38.0) | 207.4 (36.9) | 208.7 (40.3) | 193.0 (36.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 899 (48%) | 722 (45%) | 34 (68%) | 114 (63%) | 29 (85%) |

| APOE4 allele, n (%) | 609 (33%) | 505 (32%) | 16 (34%) | 72 (39%) | 16 (47%) |

ARIC=Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study

Infarcts and Risk of Dementia

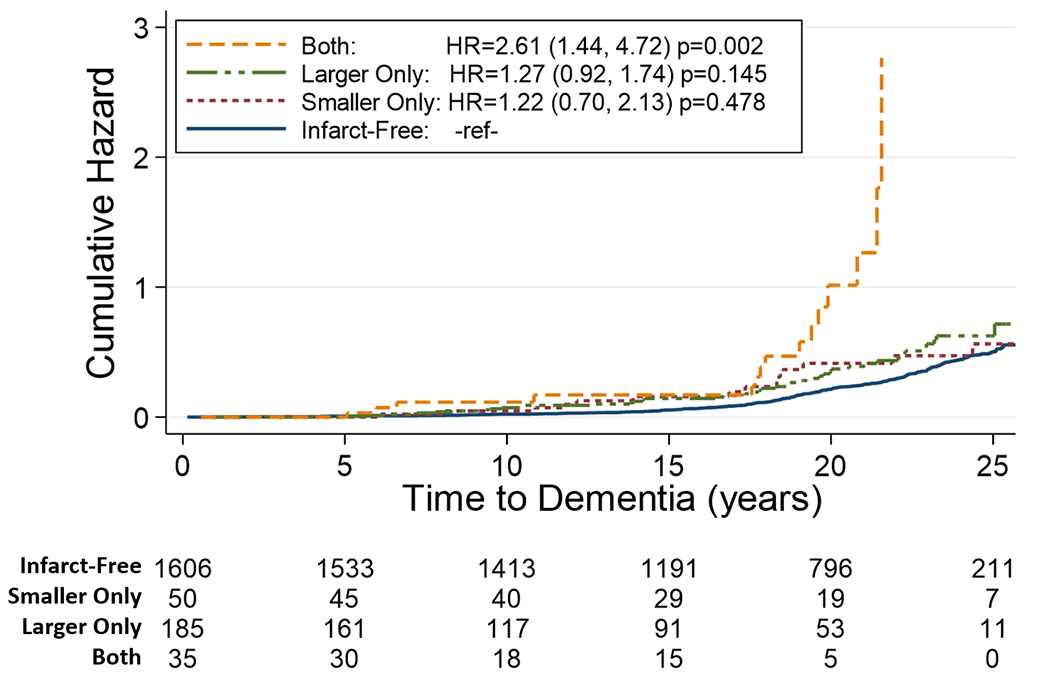

Figure 1 displays cumulative hazard estimates for incident dementia and a survival table by infarct group. Compared to infarct-free, having both smaller and larger infarcts was associated with a 2.5-fold higher risk of incident dementia (HR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.44, 4.72; p=0.002). Associations for the smaller only infarct group (HR: 1.22, 95% CI: 0.70, 2.13; p=0.478) and the larger only infarct group (HR: 1.27, 95% CI: 0.92, 1.74; p=0.145) were similar, and neither was statistically different from the no infarct group. Table 2 displays model results considering additional infarct categories incorporating count of larger infarcts. The greatest increased risk of incident dementia in this model was observed in the combined smaller+larger infarct categories, regardless of count of larger infarcts: smaller + single larger infarcts (HR: 2.60; 95% CI: 1.31, 5.17; p=0.01), smaller + multiple larger infarcts (HR: 2.62; 95% CI:0.83, 8.21; p=0.100). Model estimates with additional adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors and sample selection IPW were similar (eTable 3).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier cumulative hazard estimates for incident dementia by late midlife infarct group (referent = Infarct-free) through 25 years follow-up. Survivable table reports the number remaining at risk at each five-year time point. Hazard estimates adjusted for age, sex, ARIC site-race, education, APOE4 carrier status.

Table 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model Results for 25-year Incident Dementia by Infarct Group (Six-category)

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infarct-Free (n=1611) | - | - | - |

| Smaller Infarcts Only (n=50) | 1.22 | 0.70, 2.13 | 0.479 |

| Single Larger Infarct (n=129) | 1.22 | 0.84, 1.77 | 0.306 |

| Multiple Larger Infarcts (n=56) | 1.40 | 0.80, 2.45 | 0.232 |

| Smaller Infarcts + Single Larger Infarcts (n=17) | 2.60 | 1.31, 5.17 | 0.006 |

| Smaller Infarcts + Multiple Larger Infarcts (n=18) | 2.62 | 0.83, 8.21 | 0.099 |

Note: HR=Hazard Ratio, CI= Confidence Interval. Estimates adjusted for age, sex, ARIC site-race, education, APOE4 carrier status.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the hypotheses, we observed a significant increase in incident dementia risk associated with the coinciding presence of larger and smaller subclinical infarcts at midlife, adjusting for demographics and cardiovascular risk factors. Participants with both sized lesions had over 2.5 times higher hazard of dementia than those with neither, comparable to risk conferred by about 13 years of older age in the same model. Additionally, risk for dementia was similar for only smaller and only larger infarcts; although elevated dementia risk was not statistically different in participants with only smaller or larger infarcts compared to those with no infarcts. The similarity in associations of either infarct size with dementia risks along with previous reports of associations with other important clinical outcomes suggest that smaller infarcts are not benign and may merit clinical attention. Notably, of the 35 participants presenting with both infarct sizes, all but two had developed dementia or died through the duration of follow-up.

Our findings provide further evidence that smaller-sized infarcts, traditionally ignored in clinical and, until recent years, in research settings, may be useful subclinical markers of risk when considered with other factors of brain health, including larger infarcts. Dementia risk in the smaller only and larger only infract groups was relatively similar, in agreement with previous ARIC investigations that demonstrated similar rates of cognitive decline and stroke mortality in these groups. [7, 8] Across these investigations, participants in the “both” infarct sizes group had the highest risk of adverse outcomes. Individuals presenting with early signs of both smaller and larger infarcts may represent a particularly pervasive cerebrovascular disease threat to brain integrity compared to those with only one infarct size. This may partially be explained by evidence suggesting larger and smaller-sized infarcts result from distinct etiologic pathways and are not necessarily present on the same progressive disease continuum (i.e., small infarcts lead to larger infarcts). Smaller lesions are thought to result primarily from endothelial failures, among other proposed mechanisms.[17] In contrast, slightly larger infarcts may be more likely to result from microatheromatous disease,[18] although shared disease mechanisms when comparing subclinical infarcts less than 3mm in size with those less than 20mm in size are probable. Previous studies have demonstrated that aggregation of both cerebral small vessel disease and larger cerebral vascular insults result in poorer cognitive outcomes.[19, 20] The increased risk of dementia conferred by even a single strategically located infarct can be considerable, but location, size, and the number of lesions are important considerations in determining risk.[21, 22]. The “both” infarcts exposure category is inherently a multi-infarct classification, but our results suggest the most robust associations with increased dementia risk were in individuals with both sized infarcts, regardless of count of larger infarcts. These results lend support to the hypothesis that the combination of multiple distinct cerebrovascular pathologies confers a greater risk of dementia compared to having evidence of either pathology in isolation. The impact of microvascular disease is particularly recognized in dementia risk, perhaps even more so than macrovascular diseases,[23–25] and may play a role in the intersection of vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology in relation to dementia.[26, 27] Potentially, even smaller-sized infarcts detected at midlife could be informative regarding long-term dementia risk, especially when considered as part of a broader profile of cerebrovascular disease burden.

Comparisons to other studies examining “microinfarcts” are difficult because of the range of size definitions used. Microinfarcts are typically smaller in size than the definition used here for “smaller infarcts”, and mostly cannot be detected on 1.5T MRI as was used in this study.[28–30] Nevertheless, a multitude of investigations have reported associations between microinfarcts and dementia.[28, 30] Data from the Religious Orders Study indicated that a combination of microinfarcts (defined as 0.2 to 3.0 mm in length) and macroinfarct pathology had an additive contribution to increased dementia risk in an older sample.[29] The Chicago Health and Aging Project reported lower memory function and perceptual speed in participants with concurrent “larger” and “smaller” infarcts, although these were defined as greater than or less than 10mm respectively.[31]

Our study has some limitations to consider. Not many participants had smaller infarcts, and even fewer participants had both smaller and larger infarcts, which may have contributed to imprecision in our estimates for these exposure groups. Additionally, exact count of smaller infarcts was not ascertained. However, our observations linking smaller infarcts to dementia, stroke, and mortality, particularly in combination with larger infarcts, support an essential role of subtle changes in the vascular system on neurological and brain health outcomes. Characterization of infarcts used an older imaging technology and protocol but was careful to exclude perivascular spaces. Although we censored death as a competing risk of dementia, survival bias could be further considered. However, it would likely contribute to underestimated effect sizes considering participants with a greater degree of cerebrovascular disease had both higher dementia risk and higher mortality risk; therefore, deaths may have occurred before cognitive impairment could be detected. Lastly, although we describe this overall sample as “midlife” at the index visit, approximately a quarter would be considered young-old.

In conclusion, the simultaneous presence of larger and smaller subclinical infarcts at late midlife was associated with an increased risk of dementia over decades of follow-up. The multiplicative risk conferred by the presence of both lesion types may indicate a particularly pervasive cerebrovascular disease threat to brain health and merit characterization in future research with brain imaging assessments. These participants may represent a high-risk population identifiable by routine imaging protocol and warrant further study concerning the pathogenesis of dementia and cognitive impairment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

FUNDING

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts (75N92022D00001, 75N92022D00002, 75N92022D00003, 75N92022D00004, 75N92022D00005). The ARIC Neurocognitive Study is supported by U01HL096812, U01HL096814, U01HL096899, U01HL096902, and U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD). Additional imaging dating was collected from R01 AG040282, and K24 AG052573 from the NIA.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

RF Gottesman reports being a former associate editor for the journal Neurology. D.S. Knopman served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the DIAN study. He served on a Data Safety monitoring Board for a tau therapeutic for Biogen but received no personal compensation. He is a site investigator in Biogen aducanumab trials. He is an investigator in a clinical trials sponsored by Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the University of Southern California. He serves as a consultant for Samus Therapeutics, Roche, Magellan Health and Alzeca Biosciences but receives no personal compensation. All other authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C, et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke. Apr 2010;41(4):600–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. Mar 27 2003;348(13):1215–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos D, Wolters FJ, Darweesh SKL, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based evidence. Alzheimers Dement. Nov 2018;14(11):1482–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith EE, O’Donnell M, Dagenais G, et al. Early cerebral small vessel disease and brain volume, cognition, and gait. Ann Neurol. Feb 2015;77(2):251–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.24320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. Feb 2013;12(2):207–16. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, et al. Associations Between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and 25-Year Incident Dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort. JAMA Neurol. Oct 1 2017;74(10):1246–1254. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windham BG, Deere B, Griswold ME, et al. Small Brain Lesions and Incident Stroke and Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. Jul 7 2015;163(1):22–31. doi: 10.7326/M14-2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Windham BG, Griswold ME, Wilkening SR, et al. Midlife Smaller and Larger Infarctions, White Matter Hyperintensities, and 20-Year Cognitive Decline: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 17 2019;171(6):389–396. doi: 10.7326/M18-0295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright JD, Folsom AR, Coresh J, et al. The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study: JACC Focus Seminar 3/8. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jun 15 2021;77(23):2939–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. Aug 2013;12(8):822–38. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Prevalence: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;2:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. Nov 1993;43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr., Chance JM, Filos S Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. May 1982;37(3):323–9. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. Sep 2002;40(9):771–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. Aug 23 2005;65(4):559–64. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. May 2013;12(5):483–97. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70060-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher CM. Lacunar strokes and infarcts: a review. Neurology. Aug 1982;32(8):871–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.8.871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang Y, Chen YK, Liu YL, et al. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden Is Associated With Accelerated Poststroke Cognitive Decline: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. Nov 2019;32(6):336–343. doi: 10.1177/0891988719862630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X, Hilal S, Collinson SL, et al. Association of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Markers of Cerebrovascular Disease Burden and Cognition. Stroke. Oct 2015;46(10):2808–14. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saczynski JS, Sigurdsson S, Jonsdottir MK, et al. Cerebral infarcts and cognitive performance: importance of location and number of infarcts. Stroke. Mar 2009;40(3):677–82. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.530212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Cochran EJ, et al. Relation of cerebral infarctions to dementia and cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. Apr 8 2003;60(7):1082–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055863.87435.b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knopman DS. Cerebrovascular disease and dementia. Br J Radiol. Dec 2007;80 Spec No 2:S121–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/75681080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Nov 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. Mar 12 1997;277(10):813–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalaria RN. Small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s dementia: pathological considerations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13 Suppl 2:48–52. doi: 10.1159/000049150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai Z, Wang C, He W, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1695–704. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S90871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith EE, Schneider JA, Wardlaw JM, Greenberg SM. Cerebral microinfarcts: the invisible lesions. Lancet Neurol. Mar 2012;11(3):272–82. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70307-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke. Mar 2011;42(3):722–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrada MM, Sonnen JA, Kim RC, Kawas CH. Microinfarcts are common and strongly related to dementia in the oldest-old: The 90+ study. Alzheimers Dement. Aug 2016;12(8):900–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aggarwal NT, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Evans DA, Carli CD. Characteristics of MR infarcts associated with dementia and cognitive function in the elderly. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38(1):41–7. doi: 10.1159/000334438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.