Abstract

A multivalent live oral vaccine against both Shigella spp. and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is being developed based on the hypothesis that protection can be achieved if attenuated shigellae express ETEC fimbrial colonization factors and genetically detoxified heat-labile toxin from a human ETEC isolate (LTh). Two detoxified derivatives of LTh, LThK63 and LThR72, were engineered by substitution—serine to lysine at residue 63, or lysine to arginine at residue 72. The genes encoding these two derivatives were cloned separately on expression plasmids downstream from the CFA/I operon. Following electroporation into S. flexneri 2a vaccine strain CVD 1204, coexpression of CFA/I and LThK63 or LThR72 was demonstrated by Western blot analysis, GM1 binding assays, and agglutination with anti-CFA/I antiserum. Hemagglutination and electron microscopy confirmed surface expression of CFA/I. Guinea pigs immunized intranasally on days 0 and 15 with CVD 1204 expressing CFA/I and LThK63 or LThR72 exhibited high titers of both serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and mucosal secretory IgA anti-CFA/I; 40% of the animals produced antibodies directed against LTh. All immunized guinea pigs also produced mucosal IgA (in tears) and serum IgG anti-S. flexneri 2a O antibodies. Furthermore, all immunized animals were protected from challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a. This prototype Shigella-ETEC hybrid vaccine demonstrates the feasibility of expressing multiple ETEC antigens on a single plasmid in an attenuated Shigella vaccine strain and engendering immune responses against both the heterologous antigens and vector strain.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) and Shigella spp. are important causes of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries and are two major etiologic agents of traveler's diarrhea that are targeted for prevention (5, 13, 17, 24, 30, 47). The pathogenesis of ETEC involves fimbria-mediated colonization of the proximal small intestine followed by the elaboration of heat-labile toxin (LT) and/or heat-stable toxin that leads to net intestinal secretion (29, 33). An array of antigenically distinct fimbriae elaborated by ETEC strains associated with human disease, referred to as colonization factor antigens (CFAs) or coli surface antigens (CSs), have been described, of which CFA/I is the prototype (29, 32, 59). Considerable evidence indicates that immune responses, particularly intestinal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), directed against these fimbriae, mediate protective immunity against ETEC diarrheal disease (6, 10, 15, 34). Protection, however, is limited to the homologous fimbrial type, and therefore an ETEC vaccine will require the inclusion of multiple fimbrial antigens to confer broad-spectrum protection.

Neutralizing anti-LT is detected in the sera of patients convalescing from diarrhea caused by LT-producing ETEC and cross-reacting antitoxin elicited by cholera toxin (CT) B subunit has provided short-term protection against diarrhea caused by LT-producing ETEC (7, 45). Therefore, an ETEC vaccine should also include an appropriate nontoxic antigen to elicit neutralizing LT-antitoxin.

Rappuoli and coworkers constructed K63 and R72 mutants from the wild-type LT of a porcine ETEC strain (20, 46). LTK63 is totally devoid of enzymatic activity, whereas LTR72 shows only 0.6% of LT enzymatic activity (20). These mutant LTs stimulated LT antitoxin in mice and function as adjuvants when coadministered intranasally or orally to mice along with other protein antigens (11, 12, 49). The amino acid sequence of the LT found in human ETEC isolates (LTh) varies from the porcine LT by only 3 amino acids in the A subunit and 4 amino acids in the B subunit (60). Nevertheless, LTh and porcine LT exhibit distinct epitopes, and each functions differently as an immunogen and as an antigen in binding LT antibodies (3, 36, 56). To develop a vaccine more relevant for humans, we constructed two nontoxic LTh derivatives with the mutation K63 or R72.

Attenuated strains of Shigella are being investigated as mucosal vaccines to prevent shigellosis (8, 26–28, 57). Moreover, we demonstrated the utility of attenuated Shigella as live vectors to coexpress CFA/I and CS3 fimbriae of ETEC and elicit immune responses to those antigens (43). Building on these encouraging preliminary results, we are now constructing, in a stepwise fashion, a multivalent Shigella-ETEC vaccine that, ultimately, will contain five attenuated Shigella serotype strains, each expressing two different ETEC fimbriae and mutant LT (28, 31, 41).

In another logical step in this program, we utilized an improved Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain, CVD 1204, which harbors a deletion in the guanine nucleotide biosynthesis pathway (ΔguaBA) rendering the strain auxotrophic for guanine and highly attenuated in animal models (42) as a live vector to assess refined expression plasmids encoding CFA/I and LThK63 or LThR72. The level of expression of the ETEC antigens was documented prior to investigating the immunogenicity of the live vector constructs. We also explored whether expression of the ETEC antigens altered the ability of the live vector to protect mucosally immunized guinea pigs against challenge with wild-type Shigella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. Shigella was grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) with Congo red and guanine and E. coli was grown on LB agar. Carbenicillin and kanamycin were used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml, and guanine was added to a final concentration of 0.001%.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| H10407 | ETEC clinical isolate | CVD collection |

| S2457T | S. flexneri 2a clinical isolate | CVD collection |

| CVD 1204 | S2457T derivative containing a deletion in the guanine nucleotide biosynthesis pathway (ΔguaBA) | 42 |

| pGEN9 | Medium-copy-number plasmid (15/cell) with E. coli ompC promoter | 18 |

| pKG9 | pGEN9 derivative with Tn5 aph gene in place of bla | This work |

| pKC | pKG9 derivative with cfaABCE genes downstream from the ompC promoter | This work |

| pKCL63 | pKC derivative with the operon encoding LThK63 downstream from cfaABCE genes | This work |

| pKCLR72 | pKC derivative with the operon encoding LThR72 downstream from cfaABCE genes | This work |

Molecular genetic techniques.

Restriction enzymes, ligase, and polymerase were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. All transformations were performed in E. coli DH5α made chemically competent following the rubidium chloride method. S. flexneri 2a CVD 1204 cells were made electrocompetent by growing cells to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5 to 0.8) at 30°C. Cells were then washed twice with sterile, cold 10% glycerol in distilled H2O and resuspended in 1/75 the original culture volume in sterile, cold 10% glycerol in distilled H2O. Electroporation conditions were 1.75 kV, 600 Ω, and 25 μF.

Construction of pKC.

The aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene (aph) from Tn5, which confers kanamycin resistance, was amplified by PCR from the template pIB279 using the primers 5′-GCTCTAGAGCACAGCAAGCGAACCGGAATTGC-3′ and 5′-GGACTAGTCGCTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAG-3′. This fragment was cloned into pGEN9 (18) as an XbaI-SpeI fragment replacing the bla gene, resulting in pKG9.

The construction of pJGX15 harboring the cfaABCE genes from ETEC strain H10407 has previously been described (19). The 5′ end of the CFA/I operon was modified to include restriction endonuclease sites SstI-EcoRV-SstII by PCR using the primers 5′-TCCGAGCTCGATATCCCCGCGGAAGCTCAGGAGGAAATATGCAT-3′ and 5′-CTTTAACGCCTGCTCTAACATT-3′ and ligated into the SstI and BglII sites of pJGX15. These primers leave 18 bp upstream from the ATG start codon of cfaA intact. The modified cfaABCE genes were then cloned into pKG9 as an EcoRV-XhoI fragment to result in pKC. The plasmid was transformed into DH5α, and colonies were screened by agglutination with CFA/I antiserum. The plasmids from agglutinating DH5α were purified and electroporated into CVD 1204 and screened again by agglutination with CFA/I antiserum.

Construction of LThK63 and LThR72.

The plasmid from ETEC strain H10407 that encodes LTh was extracted using a modified Birnboim and Doly preparation (4). Primers modified to include restriction endonuclease sites EcoRV-SalI-BamHI at the 5′ end, 5′-CGGATATCCGTCGACGGGATCCCGATCCTCGCATGGATGTTTTATAAAAAACATCA-3′, and BglII-NheI sites at the 3′ end, 5′-CGGCTAGCGAAGATCTTCTAGTTTTCCATACTGATTGCCGCAATTGA-3′, were used to amplify, by PCR, the wild-type eltAB genes plus the native promoter. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) cloning vector. Colonies were screened by colony immunoblot with anti-LT subunit A (anti-LTA) and anti-LT subunit B (anti-LTB) antibodies (Biogenesis, Sandown, N.H.). Clones with high affinity for both antibodies were sequenced. The resulting eltAB operon was moved from pGEM-T as an SstII-PstI fragment into pBluescript KS.

From plasmids carrying porcine mutant eltA with the K63 or R72 modifications, a XbaI-NdeI fragment containing the mutated regions was exchanged into our plasmids containing eltA from H10407. In this manner, two new plasmids, pLThK63 and pLThR72, were derived. The sequence of the eltAB regions of these plasmids was confirmed.

Construction of pKCL63 and pKCL72.

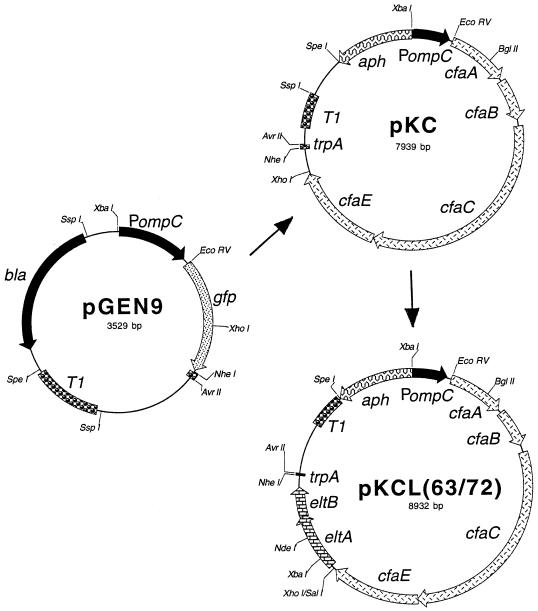

To construct plasmids coexpressing CFA/I and each of the mutant LThs, the modified operons encoding LTh were cloned as XhoI-NheI fragments downstream from the cfaABCE genes in pKC, resulting in two new constructs named pKCL63 and pKCL72 (Fig. 1). These constructions were electroporated into CVD 1204. A relevant feature of pKCL63 and pKCL72 is that the selection marker that they encode is for kanamycin resistance, which is permissible in vaccines for human use. The CFA/I operon is under the control of the ompC promoter that is selectively activated by increased osmolarity and the LTh operons are under control of the native LT promoter.

FIG. 1.

Plasmid maps of pGEN9 derivatives. pGEN9 was modified by the replacement of the bla gene with the aph gene followed by insertion of the CFA/I operon to create pKC. Insertion of the operons encoding LThK63 or LThR72 downstream from CFA/I created the plasmids pKCL63 and pKCL72.

Hemagglutination.

The ability of CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) to hemagglutinate human type A erythrocytes was used as one measure to confirm the surface expression of CFA/I (35). Citrated, type A human erythrocytes (0.5-ml volume) were washed three times with 5 ml of 0.15 M NaCl and resuspended in the same solution to a final concentration of 3% (vol/vol). Bacteria were harvested from a plate and suspended in 1 ml of 0.15 M NaCl to an OD600 of >1.0. On a glass slide 20 μl of 0.1 M d-(+)-mannose in 0.15 M NaCl, 20 μl of the bacterial suspension, and 20 μl of the washed erythrocytes were mixed with a sterile wooden stick.

Electron microscopy (EM).

Bacterial cells harvested from overnight broth cultures of CVD 1204, CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed onto 300-mesh copper grids coated with carbon Formvar for 2 min. The grids were then stained for 45 s with 1% phosphotungstic acid, pH 7.2, and examined in a JEOL JEM 1200 EXII transmission electron microscope at 80 kV.

Western immunoblot analysis.

Bacterial broth cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 1.0 and then concentrated 10-fold. Purified, commercial LTh (Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute, Berne, Switzerland) was diluted to a concentration of 50 ng/ml, and purified CFA/I was diluted to a concentration of 200 ng/ml. Bacterial and purified protein samples were mixed 1:1 (vol/vol) with Laemmli sample buffer and 5% β-mercaptoethanol and then boiled for 7 min. Aliquots of 5 μl of each sample were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were stained with Gelcode Blue Stain Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) for visualization of protein bands or transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) for Western immunoblot analysis. Membranes were probed with either absorbed polyclonal rabbit anti-CFA/I (22) or monoclonal mouse anti-LTA (Biogenesis). Western immunoblots were developed using BCIP/NBT membrane phosphatase substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Monoganglioside GM1 binding assay.

Periplasmic protein eluates were prepared from all strains by polymyxin B release as previously described (16, 50). Immunolon 2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with 0.1 μg of GM1 per well. Plates were washed three times with PBS and then blocked with 5% fetal bovine serum in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed thrice with PBS-Tween. Periplasmic eluates, 100 μl, were added to the plates and serially diluted twofold after an initial dilution of 1 in 10. Purified LTh (Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute) was used to generate a standard curve by twofold serial dilution, starting at a concentration of 200 ng/ml. Plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and then washed thrice with PBS-Tween. Rabbit anti-CT antiserum diluted 1:3,200 in PBS-Tween–1% fetal bovine serum was added. Plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed three times with PBS-Tween. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (GIBCO BRL)-alkaline phosphatase conjugate diluted 1:5,000 in PBS was added at a concentration of 100 μl/well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After washing three times with PBS-Tween, 100 μl of alkaline phosphatase substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 3 N NaOH (50 μl/well). Plates were read at 405 nm with a Titertek Multiskan Multisoft ELISA reader (ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.). Regression analysis (R2 > 0.9) was used to generate a standard curve for determination of LT concentrations in each sample.

Growth studies.

Overnight 5-ml LB broth cultures (37°C) were subcultured 1:100 in fresh broth and grown again at 37°C, and the absorbances were measured at 600 nm at 30-min intervals.

Immunizations and sample collection.

Overnight cultures of the immunizing strains were harvested from TSA-guanine plates (with kanamycin as required) with PBS to a concentration of 1010 CFU/ml. After sedation with a 1:1 solution of ketamine-xylazine, randomized, female, Hartley guinea pigs (8 weeks old) were immunized intranasally with 100 μl of the bacterial suspension. An identical booster dose was administered 14 days later. Tears, elicited from guinea pigs as previously described (44), were collected in 50-μl capillary tubes. Blood was obtained from anesthetized guinea pigs by cardiac puncture on days 0, 14, and 28 postimmunization.

ELISA.

Antigens used in ELISA included hot water-phenol-extracted S. flexneri 2a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from strain 2457T (44, 58), purified CFA/I fimbriae from strain H10407 (22), and LTh (Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute). IgA antibodies against S. flexneri 2a LPS, CFA/I, and LTh in tears were measured by ELISA using rabbit anti-guinea pig IgA α-chain-specific antibody (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, Tex.). Specific IgG LPS, CFA/I, and LTh antibodies in sera of guinea pigs were determined by ELISA using goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) conjugate. The initial dilutions were 1:25 for sera and 1:40 for tears. The end point titer was determined to be the highest dilution giving an A405 value of >0.1. This cutoff value was determined as the mean ± 2 standard deviations above the mean OD value of 20 normal guinea pig samples run at a 1:20 dilution. Data were analyzed by Student's t test (one tailed).

Protection assay.

Wild-type S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T was harvested from TSA plates into PBS to a concentration of 5.5 × 109 CFU/ml. Groups of vaccinated and sham-immunized guinea pigs (n = 5 per group) were challenged by the Sereny keratoconjunctivitis test by administering 10 μl of the bacterial suspension into the conjunctival sac of one eye (54). Guinea pigs were examined for 5 days by an observer who was unaware of the immunization status of the animals, and the degree of inflammatory response, if any, was graded as previously described (44).

RESULTS

ETEC antigen expression in attenuated S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204.

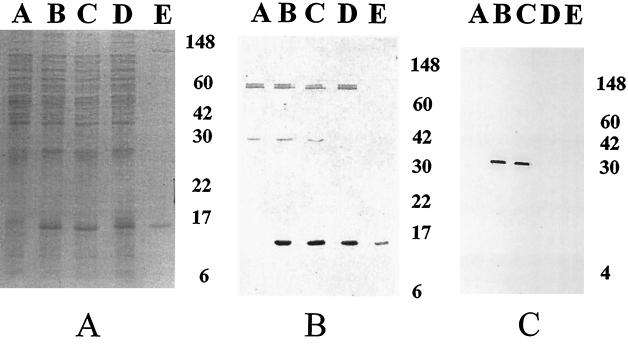

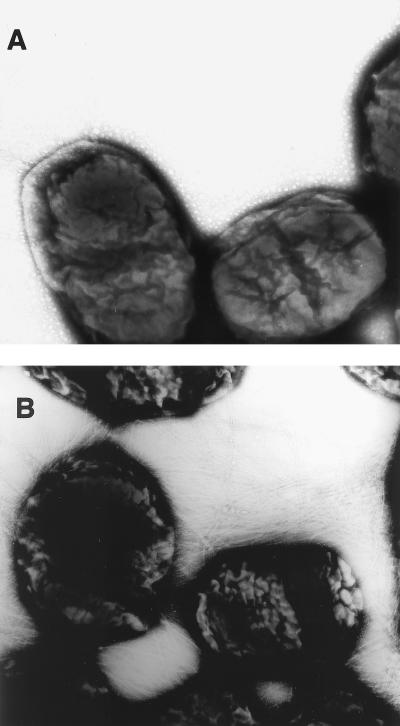

The expression plasmids (Fig. 1) encoding nontoxic LThs and/or CFA/I were electroporated into S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204. A 15-kDa polypeptide was detected in whole-cell lysates of CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) but not of CVD 1204 (Fig. 2A). Immunoblotting with specific CFA/I antiserum confirmed that this was the 15-kDa CfaB subunit (Fig. 2B), the major structural component of CFA/I fimbriae. Although CfaB is the main component of CFA/I fimbriae, effective export and surface assembly of the fimbriae are dependent on appropriate expression of all the genes encoded in the CFA/I operon. CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) were all agglutinated with rabbit anti-CFA/I. In addition, these strains agglutinated type A human erythrocytes in the presence of d-mannose, providing strong evidence that the CFA/I fimbriae were assembled in a functional conformation on the surface of the CVD 1204 derivatives. Surface expression and typical fimbrial morphology were confirmed by EM (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Expression of CFA/I and LTh in CVD 1204. Whole-cell lysates of CVD 1204 and derivatives were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by staining with Gelcode Blue (A) or were transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes and probed with anti-CFA/I antibody (B) or anti-LTA monoclonal antibody (C). Lanes A, S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204; lanes B, CVD 1204(pKCL63); lanes C, CVD 1204(pKCL72); lanes D, CVD 1204(pKC); lanes E, purified CFA/I. Numbers to the right of each panel are molecular masses (in kilodaltons).

FIG. 3.

Electron micrographs of CVD 1204 vector strain alone (A) and CVD 1204(pKCL63) expressing CFA/I (B). Bacteria were stained with phosphotungstic acid and viewed by direct transmission EM. Magnification, ×30,000.

In order to demonstrate that mutant LTh was coexpressed with CFA/I in CVD 1204, the same whole-cell lysate samples were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a protein binding membrane. Western immunoblot analysis of the membrane with mouse monoclonal anti-LTA antibodies detected the 30-kDa A subunit of LT in whole-cell lysates of CVD 1204(pKCL63) and CVD 1204(pKCL72) (Fig. 2C). No band of this molecular mass was detected in the immunoblots of the control strains that carry plasmids lacking the elt operon (Fig. 2C, lanes A, D, and E).

Periplasmic eluates were prepared from H10407, CVD 1204, CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) and subjected to a monoganglioside GM1 binding assay to determine if the B subunits of the detoxified LTh would assemble into ganglioside-binding pentamers (21). No GM1 binding was detected in periplasmic eluates of CVD 1204 or CVD 1204(pKC), the strain expressing CFA/I alone (Table 2). In contrast, GM1 binding was detected in the periplasmic eluates of H10407, CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72) (Table 2). The mutant LTh-expressing CVD 1204 strains produced more LTh than the wild-type ETEC H10407 under laboratory growth conditions, presumably because of the multiple plasmid copies carrying the LTh operon.

TABLE 2.

GM1 binding of periplasmic eluates

| Strain | Mean amount of LTh binding GM1 ± SD (ng/OD600) |

|---|---|

| CVD 1204 | 0 |

| CVD 1204(pKC) | 0 |

| H10407 | 7 ± 1 |

| CVD 1204(pKCL63) | 138 ± 58 |

| CVD 1204(pKCL72) | 185 ± 44 |

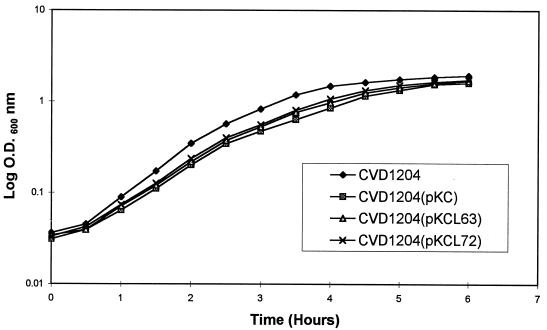

Since expression of foreign antigens can impose a metabolic burden on a vector strain, we performed a growth study on S. flexneri 2a strains CVD 1204, CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), and CVD 1204(pKCL72). Figure 4 shows that although there was a visible but small difference in growth rates between CVD 1204 alone and CVD 1204 expressing CFA/I and/or LTh, the difference was not considered important in terms of overall growth time.

FIG. 4.

Growth analysis of CVD 1204 derivatives. Broth cultures of CVD 1204 and derivatives were sampled at 30-min intervals, and OD recorded as a measure of bacterial growth.

Immunization studies.

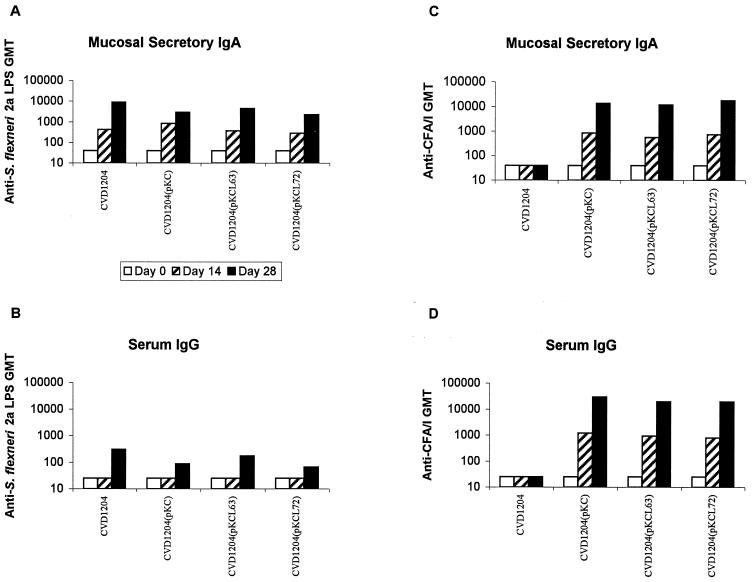

Guinea pigs were immunized intranasally with two doses, 14 days apart, of CVD 1204, CVD 1204(pKC), CVD 1204(pKCL63), or CVD 1204(pKCL72). Mucosal IgA antibodies against S. flexneri 2a LPS were detected in tears of all vaccinated animals following the primary immunization with each of the vaccine strains (Fig. 5A). Serum IgG against S. flexneri 2a LPS was not detected until two doses of the vaccine strains had been administered. The postvaccination geometric mean titers of sIgA (in tears) and serum IgG anti-S. flexneri 2a O antibody were similar among the groups of animals immunized with the various live strains (P > 0.05).

FIG. 5.

Serum and mucosal immune responses to Shigella and CFA/I in guinea pigs immunized with CVD 1204 or derivatives. Geometric mean titers of mucosal anti-S. flexneri 2a LPS (A), serum anti-S. flexneri 2a LPS (B), mucosal anti-CFA/I (C), or serum anti-CFA/I antibodies (D) were measured in serum and tears of immunized guinea pigs. Immunizing strains are indicated on the x axis. Geometric mean titers are shown for preimmune samples (open bars), samples following one intranasal inoculation (hatched bars), or samples following two doses (solid bars).

All animals receiving a CVD 1204 derivative expressing CFA/I responded with high titers of sIgA and serum IgG antibodies against CFA/I following the primary immunization (Fig. 5C and D). These titers were boosted to very high levels following a second dose. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in either sIgA or serum IgG titers between groups immunized with strains expressing LThR72 or LThK63 and CFA/I compared with the group expressing CFA/I alone. Thus, in these experiments there was no evidence that coexpression of mutant LTh adjuvanted the immune responses to CFA/I.

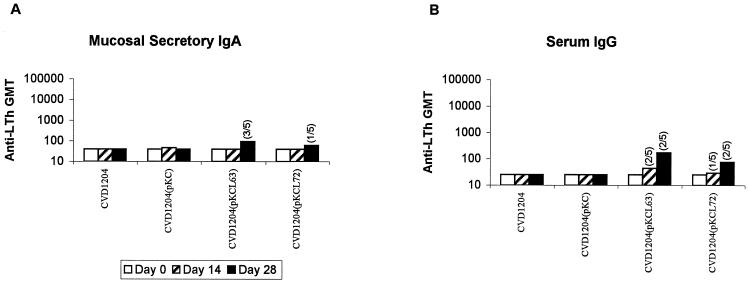

Within the groups of guinea pigs immunized with CVD 1204 strains expressing LThK63 or LThR72, 40% of the guinea pigs exhibited sIgA or serum IgG responses against LTh after boosting (Fig. 6). There were no significant differences in titers between the groups immunized with strains expressing LThK63 or LThR72.

FIG. 6.

Serum and mucosal immune responses to LT in guinea pigs immunized with CVD 1204 or derivatives. Geometric mean titers are shown for mucosal anti-LTh IgA measured in tears (A) or serum anti-LTh IgG (B). Immunizing strains are indicated on the x axis. Geometric mean titers are shown for preimmune samples (open bars), samples following one intranasal inoculation (hatched bars), or samples following two doses (solid bars). The number of animals responding per total number of animals in a group is indicated in parentheses above some bars.

Challenge assay.

In order to verify that coexpression of ETEC antigens did not alter the ability of the live vector strain CVD 1204 to confer protection against Shigella, immunized animals were challenged with wild-type S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T in the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model. All nonimmunized control guinea pigs developed purulent keratoconjunctivitis following Sereny test challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a (Table 3). None of the guinea pigs immunized with CVD 1204 or CVD 1204 expressing any ETEC antigen developed purulent keratoconjunctivitis during the course of observation.

TABLE 3.

Protection following challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a strain S2457T

| Strain | No. of guinea pigs | No. of animals with purulent keratoconjunctivitis |

|---|---|---|

| CVD 1204 | 5 | 0 |

| CVD 1204(pKC) | 5 | 0 |

| CVD 1204(pKCL63) | 5 | 0 |

| CVD 1204(pKCL72) | 5 | 0 |

| Sham-immunized | 5 | 5 |

DISCUSSION

Several years ago we first demonstrated that Shigella could be used as a live vector to deliver ETEC antigens to the mucosal immune system. In attenuated ΔaroA ΔvirG S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1203, we successfully coexpressed from two separate plasmids the ETEC fimbriae CFA/I and fibrillae CS3 (43). Following mucosal immunization of guinea pigs with the live vector, strong immune responses to both ETEC fimbrial antigens were demonstrated (43). In the current study, we refined a prototype Shigella-ETEC vaccine to one more suitable for use in humans. We expressed in ΔguaBA S. flexneri 2a vaccine strain CVD 1204 two ETEC antigens, mutant LTh and CFA/I fimbriae, from a single plasmid also encoding kanamycin resistance, a selection marker suitable for human vaccines.

CVD 1204 is one of a new generation of attenuated Shigella vector strains based on deletions in guaBA (42). Our previous constructions utilized ΔaroA ΔvirG S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1203, which in volunteer studies was found to be highly immunogenic and well tolerated at low (106 PFU) dosage levels but unacceptably reactogenic at high (108 to 109 PFU) dosages (27, 44). Shigella vaccine strains with a deletion in guaBA are highly attenuated in animal models (2, 42). Moreover, CVD 1207, a ΔguaBA ΔvirG Δset Δsen S. flexneri 2a strain, was recently found in a phase 1 clinical trial to be the most attenuated derivative of wild-type strain 2457T that we or others have so far been able to achieve (28).

We found that the expression of CFA/I alone or CFA/I coexpressed with mutant LTh in ΔguaBA S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204 did not diminish in the guinea pig model the immune response elicited against the protective O antigen of the vector strain itself. Indeed, following the priming immunization, all immunized animals produced sIgA antibodies against S. flexneri 2a O antigen. We then confirmed that expression of ETEC fimbriae and mutant LT did not diminish the capacity of the vector strain to protect against challenge with Shigella in the Sereny test in guinea pigs.

Modern approaches to ETEC oral vaccine development involve various strategies to elicit antifimbrial and antitoxic immunity, including the use of formalin-killed whole-cell ETEC in combination with recombinant CTB (1, 25, 52, 53) and encapsulated fimbrial antigens (14, 55). An attraction of the approach that we are pursuing is that it is directed jointly against two diarrheal pathogens that cause disease in the same target populations, namely, young children in developing countries and travelers.

It is highly encouraging to observe that attenuated S. flexneri 2a strain 1204 expressing CFA/I elicited high titers of sIgA and serum IgG anti-CFA/I antibodies following mucosal immunization of guinea pigs. The fact that this was accomplished with a plasmid carrying a selection marker (kanamycin resistance) that is compatible with use in humans brings us a step closer to a clinical trial. On the other hand, these preclinical studies identified a problem with the LTh component of the double expression plasmids. Only 40% of the immunized animals exhibited anti-LTh responses, and the level of responses were similar for both the LThK63 and the LThR72 constructs. Based on preliminary experiments carried out after these observations, we hypothesize that the reason for the modest immunogenicity of the mutant LTh constructs relates to insufficient expression driven by the native LT promoter. Accordingly, different promoters have been introduced that markedly increase the level of expression. We expect to test this hypothesis in the near future through immunogenicity studies with constructs having higher expression levels of mutant LTh.

There have been multiple reports that LTK63 and LTR72 manifest an adjuvant effect when they are coadministered intranasally with bystander antigens (11, 12, 20, 37, 49). Ryan et al. (51) demonstrated that a nontoxic LT derivative, LTR192G, augmented vibriocidal responses in mice vaccinated with Vibrio cholerae expressing the mutant LT. Covone et al. (9) noted an enhanced anti-Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium O antibody response in mice immunized with serovar Typhimurium expressing mutant LT. Finally, Hartman et al. (23) demonstrated adjuvant activity of detoxified LT in increasing immune responses to Shigella vaccine strains when coadministered in purified form. In contrast to these reports, we failed to detect an adjuvant effect against either Shigella LPS or CFA/I in groups immunized with constructs expressing both nontoxic LTh and CFA/I. This lack of adjuvant effect could be due to the periplasmic location of LTh in Shigella or the level of LTh expression in our constructs. Future work will involve increasing nontoxic LTh expression with the use of stronger promoters in our Shigella derivatives which coexpress fimbriae and nontoxic LTh constructs.

In addition to nontoxic LTh, a comprehensive vaccine against ETEC will have to include the several fimbrial types most commonly associated with human ETEC infection, at the least CFA/I and CS1 through CS6 (32, 48, 59). Although antibody cross-reactivity has been demonstrated among some of the fimbrial types, cross-protection is not believed to occur between ETEC strains of different fimbrial types (30). That immune responses against multiple fimbrial types can be elicited when multiple ETEC strains are used in a vaccine formulation has been reported with the formalin-killed cholera B subunit vaccine (1, 25, 52, 53). Similarly, Mel et al. (38–40) were able to confer immunity against several Shigella serotypes using a combination live oral vaccine containing several different serotypes of attenuated streptomycin-dependent Shigella strains. These reports are encouraging for our approach to develop a multivalent hybrid live Shigella-ETEC vaccine which will ultimately contain five attenuated Shigella strains (serotypes Shigella dysenteriae 1, S. flexneri 2a, S. flexneri 3a, S. flexneri 6, and Shigella sonnei), each expressing ETEC fimbrial antigens and a mutant LTh. This S. flexneri trio shares a group or type antigen with the other 12 S. flexneri serotypes and subtypes, and cross-protection was demonstrable in the guinea pig model (41). The abilities of a prototype attenuated Shigella live vector to coexpress CFA/I and mutant LTh from a single plasmid encoding kanamycin resistance, to stimulate anti-CFA/I responses in all immunized animals and anti-LT in 40% of the animals, and to retain the capacity to protect against wild-type Shigella constitute additional landmarks of progress in this ambitious project.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were supported by grant RO1 AI 29471 from the NIAID and grants from the Chiron Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation (M. M. Levine, principal investigator).

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of John Czeczulin in the EM studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahren C, Jertborn M, Svennerholm A M. Intestinal immune responses to an inactivated oral enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine and associated immunoglobulin A responses in blood. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3311–3316. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3311-3316.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson R, Pasetti M F, Sztein M B, Levine M M, Noriega F N. ΔguaBA attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204 as a Shigella vaccine and as a live mucosal delivery system for fragment C of tetanus toxin. Vaccine. 2000;18:2193–2202. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belisle B W, Twiddy E M, Holmes R K. Monoclonal antibodies with an expanded repertoire of specificities and potent neutralizing activity for Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1984;46:759–764. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.3.759-764.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black R E, Merson M H, Huq I, Alim A R M A, Yunus M. Incidence and severity of rotavirus and Escherichia coli diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Lancet. 1981;i:141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black R E, Merson M H, Rowe B, Taylor P R, Abdul Alim A R, Gross R J, Sack D A. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea: acquired immunity and transmission in an endemic area. Bull W H O. 1981;59:263–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens J D, Sack D A, Harris J R, Chakraborty J, Neogy P K, Stanton B, Huda N, Khan M U, Kay B A, Khan M R, Ansaruzzaman M, Yunus M, Rao M R, Svennerholm A-M, Holmgren J. Cross-protection by B subunit-whole cell cholera vaccine against diarrhea associated with heat-labile toxin-producing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: results of a large-scale field trial. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:372–377. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coster T S, Hoge C W, VanDeVerg L L, Hartman A B, Oaks E V, Venkatesan M M, Cohen D, Robin G, Fontaine-Thompson A, Sansonetti P J, Hale T L. Vaccination against shigellosis with attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain SC602. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3437–3443. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3437-3443.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covone M G, Brocchi M, Palla E, da Silveira W D, Rappuoli R, Galeotti C L. Levels of expression and immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains expressing Escherichia coli mutant heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:224–231. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.224-231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cravioto A, Reyes R E, Ortega R, Fernandez G, Hernandez R, Lopez D. Prospective study of diarrhoeal disease in a cohort of rural Mexican children: incidence and isolated pathogens during the first two years of life. Epidemiol Infect. 1988;101:123–134. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800029289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douce G, Giannelli V, Pizza M, Lewis D, Everest P, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Genetically detoxified mutants of heat-labile toxin from Escherichia coli are able to act as oral adjuvants. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4400–4406. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4400-4406.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douce G, Turcotte C, Cropley I, Roberts M, Pizza M, Domenighini M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin lacking ADP-ribosyltransferase activity act as nontoxic, mucosal adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1644–1648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DuPont H L, Olarte J, Evans D G, Pickering L K, Galindo E, Evans D J. Comparative susceptibility of Latin American and United States students to enteric pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1976;285:1520–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197612302952707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman R, Russel R G, Losonsky G A, Tall B D, Tacket C O, Levine M M, Lewis D H. Immunization of rabbits with enterotoxigenic E. coli colonization factor antigen (CFA/I) encapsulated in biodegradable microspheres of poly (lactide-co-glycolide) Vaccine. 1993;11:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90012-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans D G, Satterwhite T K, Evans D J, Jr, DuPont H L. Differences in serological responses and excretion patterns of volunteers challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli with and without the colonization factor antigen. Infect Immun. 1978;19:883–888. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.3.883-888.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans D J, Jr, Evans D G, Gorbach S L. Polymyxin B-induced release of low-molecular-weight, heat-labile enterotoxin from Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1974;10:1010–1017. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.5.1010-1017.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreccio C, Prado V, Ojeda A, Cayazzo M, Abrego P, Guers L, Levine M M. Epidemiologic patterns of acute diarrhea and endemic Shigella infections in a poor periurban setting in Santiago, Chile. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:614–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galen J E, Nair J, Wang J Y, Wasserman S S, Tanner M K, Sztein M B, Levine M M. Optimization of plasmid maintenance in the attenuated live vector vaccine strain Salmonella typhi CVD 908-htrA. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6424. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6424-6433.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giron J A, Xu J-G, Gonzalez C R, Hone D M, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Simultaneous constitutive expression of CFA/I and CS3 colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by aroC, aroD Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 908. Vaccine. 1995;10:939–946. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00003-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuliani M M, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, Dougan G, Douce G, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1123–1132. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guidry J J, Cardenas L, Cheng E, Clements J D. Role of receptor binding in toxicity, immunogenicity, and adjuvanticity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4943–4950. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4943-4950.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall R H, Maneval D R, Collins J H, Theibert J L, Levine M M. Purification and analysis of colonization factor antigen I, coli surface antigen 1, and coli surface antigen 3 fimbriae from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6372–6374. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6372-6374.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartman A B, Van de Verg L L, Venkatesan M M. Native and mutant forms of cholera toxin and heat-labile enterotoxin effectively enhance protective efficacy of live attenuated and heat-killed Shigella vaccines. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5841–5847. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5841-5847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyams K C, Bourgeois A L, Merrell B R, Rozmahel R, Escamilla J, Thornton S A, Wasserman G M, Burke A, Echeverria P, Green K Y, Kapikian A Z, Woody J N. Diarrheal disease during Operation Desert Shield. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1423–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jertborn M, Ahren C, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A M. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral inactivated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vaccine. Vaccine. 1998;16:255–260. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karnell A, Li A, Zhao C R, Karlsson K, Minh N B, Lindberg A A. Safety and immunogenicity study of the auxotrophic Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine SFL1070 with a deleted aroD gene in adult Swedish volunteers. Vaccine. 1995;13:88–89. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)80017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotloff K L, Noriega F, Losonsky G A, Sztein M B, Wasserman S S, Nataro J P, Levine M M. Safety, immunogenicity, and transmissibility in humans of CVD 1203, a live oral Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine candidate attenuated by deletions in aroA and virG. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4542–4548. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4542-4548.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotloff K L, Noriega F R, Samandari T, Sztein M B, Losonsky G A, Nataro J P, Picking W D, Barry E M, Levine M M. Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1207, with specific deletions in virG, sen, set, and guaBA, is highly attenuated in humans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1034–1039. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1034-1039.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine M M. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine M M, Ferreccio C, Prado V, Cayazzo M, Abrego P, Martinez J, Maggi L, Baldini M, Martin W, Maneval D, Kay B, Guers L, Lior H, Wasserman S S, Nataro J P. Epidemiologic studies of Escherichia coli infections in a low socioeconomic level periurban community in Santiago, Chile. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:849–869. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine M M, Galen J, Barry E, Noriega F, Tacket C, Sztein M, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Losonsky G, Kotloff K. Attenuated Salmonella typhi and Shigella as live oral vaccines and as live vectors. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine M M, Giron J A, Noriega F. Fimbrial vaccines. In: Klemm P, editor. Fimbriae: adhesion, biogenics, genetics and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine M M, Kaper J B, Black R E, Clements M L. New knowledge on pathogenesis of bacterial enteric infections as applied to vaccine development. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:510–550. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.510-550.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine M M, Nalin D R, Hoover D L, Bergquist E J, Hornick R B, Young C R. Immunity to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1979;23:729–736. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.729-736.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine M M, Rennels M B, Daya V, Hughes T P. Hemagglutination and colonization factors in enterotoxigenic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea. J Infect Dis. 1980;141:733–737. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine M M, Young C R, Black R E, Takeda Y, Finkelstein R A. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to measure antibodies to purified heat-labile enterotoxins from human and porcine strains of Escherichia coli and to cholera toxin: application in serodiagnosis and seroepidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:174–179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.2.174-179.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchetti M, Rossi M, Giannelli V, Giuliani M M, Pizza M, Censini S, Covacci A, Massari P, Pagliaccia C, Manetti R, Telford J L, Douce G, Dougan G, Rappuoli R, Ghiara P. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in mice by intragastric vaccination with H. pylori antigens is achieved using a non-toxic mutant of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) as adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mel D M, Arsic B L, Nikolic B D, Radovanovic M L. Studies on vaccination against bacillary dysentery. 4. Oral immunization with live monotypic and combined vaccines. Bull W H O. 1968;39:375–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mel D M, Arsic B L, Radovanovic M L, Litvinjenko S. Live oral Shigella vaccine: vaccination schedule and the effect of booster dose. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1974;21:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mel D M, Gangarosa E J, Radovanovic M L, Arsic B L, Litvinjenko S. Studies on vaccination against bacillary dysentery. 6. Protection of children by oral immunization with streptomycin-dependent Shigella strains. Bull W H O. 1971;45:457–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noriega F R, Liao F M, Maneval D R, Ren S, Formal S B, Levine M M. Strategy for cross-protection among Shigella flexneri serotypes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:782–788. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.782-788.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noriega F R, Losonsky G, Lauderbaugh C, Liao F M, Wang M S, Levine M M. Engineered ΔguaB-A, ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1205: construction, safety, immunogenicity and potential efficacy as a mucosal vaccine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3055–3061. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3055-3061.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noriega F R, Losonsky G, Wang J Y, Formal S B, Levine M M. Further characterization of ΔaroA, ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1203 as a mucosal Shigella vaccine and as a live vector vaccine for delivering antigens of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:23–27. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.23-27.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noriega F R, Wang J Y, Losonsky G, Maneval D R, Hone D M, Levine M M. Construction and characterization of attenuated ΔaroA ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1203, a prototype live oral vaccine. Infect Immun. 1995;65:5168–5172. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5168-5172.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peltola H, Siitonen A, Kyrönseppä H, Simula I, Mattila L, Oksanen P, Kataja M J, Cadoz M. Prevention of travellers' diarrhoea by oral B-subunit/whole-cell cholera vaccine. Lancet. 1991;338:1285–1289. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pizza M, Domenighini M, Hol W, Giannelli V, Fontana M R, Giuliani M M, Magagnoli C, Peppoloni S, Manetti R, Rappuoli R. Probing the structure-activity relationship of Escherichia coli LT-A by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prado, V., R. Lagos, J. P. Nataro, O. San Martin, C. Arellano, J. Y. Wang, A. A. Borczyk, and M. M. Levine. A population-based study of the incidence of Shigella diarrhea and causative serotypes in Santiago, Chile. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Qadri, F., S. K. Das, A. S. G. Faruque, G. J. Fuchs, M. J. Albert, R. B. Sack, and A. M. Svennerholm. Prevalence of toxin types and colonization factors in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated during a 2-year period from diarrheal patients in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Douce G, Dougan G. Structure and mucosal adjuvanticity of cholera and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins. Immunol Today. 1999;20:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ristaino P A, Levine M M, Young C R. Improved GM1-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:808–815. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.4.808-815.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan E T, Crean T I, John M, Butterton J R, Clements J D, Calderwood S B. In vivo expression and immunoadjuvancy of a mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli in vaccine and vector strains of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1694–1701. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1694-1701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savarino S J, Brown F M, Hall E, Bassily S, Youssef F, Wierzba T, Peruski L, El-Masry N A, Safwat M, Rao M, Jertborn M, Svennerholm A M, Lee Y J, Clemens J D. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral, killed enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-cholera toxin B subunit vaccine in Egyptian adults. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:796–799. doi: 10.1086/517812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Savarino S J, Hall E R, Bassily S, Brown F M, Youssef F, Wierzba T F, Peruski L, El-Masry N A, Safwat M, Rao M, El Mohamady H, Abu-Elyazeed R, Naficy A, Svennerholm A M, Jertborn M, Lee Y J, Clemens J D. Oral, inactivated, whole cell enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli plus cholera toxin B subunit vaccine: results of the initial evaluation in children. PRIDE Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:107–114. doi: 10.1086/314543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sereny B. Experimental keratoconjunctivitis shigellosa. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1957;4:367–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacket C O, Reid R H, Boedeker E C, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Bhagat H, Edelman R. Enteral immunization and challenge of volunteers given enterotoxigenic E. coli CFA/II encapsulated in biodegradable microspheres. Vaccine. 1994;12:1270–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(94)80038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeda Y, Honda T, Sima H, Tsuji T, Miwatani T. Analysis of antigenic determinants in cholera enterotoxin and heat-labile enterotoxins from human and porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1983;41:50–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.1.50-53.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teska J D, Coster T, Byrne W R, Colbert J R, Taylor D, Venkatesan M, Hale T L. Novel self-sampling culture method to monitor excretion of live, oral Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine SC602 during a community-based phase 1 trial. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;134:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: extraction with phenol-water and further application of procedures. Methods Carbohydr Chem. 1965;5:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolf M K. Occurrence, distribution, and associations of O and H serogroups, colonization factor antigens, and toxins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:569–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamamoto T, Gojobori T, Yokota T. Evolutionary origin of pathogenic determinants in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae O1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1352–1357. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1352-1357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]