Abstract

Rates of tau accumulation in cognitively unimpaired older adults are subtle, with magnitude and spatial patterns varying in recent reports. Regional accumulation also likely varies in the degree to which accumulation is amyloid-β-dependent. Thus, there is a need to evaluate the pattern and consistency of tau accumulation across multiple cognitively unimpaired cohorts and how these patterns relate to amyloid burden, in order to design optimal tau end points for clinical trials.

Using three large cohorts of cognitively unimpaired older adults, the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s and companion study, Longitudinal Evaluation of Amyloid Risk and Neurodegeneration (n = 447), the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (n = 420) and the Harvard Aging Brain Study (n = 190), we attempted to identify regions with high rates of tau accumulation and estimate how these rates evolve over a continuous spectrum of baseline amyloid deposition. Optimal combinations of regions, tailored to multiple ranges of baseline amyloid burden as hypothetical clinical trial inclusion criteria, were tested and validated.

The inferior temporal cortex, fusiform gyrus and middle temporal cortex had the largest effect sizes of accumulation in both longitudinal cohorts when considered individually. When tau regions of interest were combined to find composite weights to maximize the effect size of tau change over time, both longitudinal studies exhibited a similar pattern—inferior temporal cortex, almost exclusively, was optimal for participants with mildly elevated amyloid β levels. For participants with highly elevated baseline amyloid β levels, combined optimal composite weights were 53% inferior temporal cortex, 31% amygdala and 16% fusiform. At mildly elevated levels of baseline amyloid β, a sample size of 200/group required a treatment effect of 0.40–0.45 (40–45% slowing of tau accumulation) to power an 18-month trial using the optimized composite. Neither a temporal lobe composite nor a global composite reached 80% power with 200/group with an effect size under 0.5.

The focus of early tau accumulation on the medial temporal lobe has resulted from the observation that the entorhinal cortex is the initial site to show abnormal levels of tau with age. However, these abnormal levels do not appear to be the result of a high rate of accumulation in the short term, but possibly a more moderate rate occurring early with respect to age. While the entorhinal cortex plays a central role in the early appearance of tau, it may be the inferior temporal cortex that is the critical region for rapid tau accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: tau, amyloid β, preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, clinical trial

Insel et al. examine the regional accumulation of tau in three large cohorts of cognitively unimpaired older adults. They show that while the entorhinal cortex plays a central role in the early appearance of tau, it may be the inferior temporal cortex that is the critical region for rapid tau accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

For the podcast associated with this article, please visit https://academic.oup.com/brain/pages/podcast

Introduction

Aberrant accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau proteins into plaques and tangles begins decades before the onset of clinical signs of dementia. Numerous prevention trials are currently underway to test the hypothesis that anti-amyloid approaches, if implemented early, will delay future dementia onset.1 The long delay between initial amyloid accumulation and clinically meaningful decline makes demonstrating drug efficacy on clinical outcomes while treating early particularly difficult.2,3 Although removal of amyloid may be one indicator of disease modification, amyloid removal alone may not be well-correlated with clinical benefit in clinically symptomatic individuals.4 Another approach to assess disease modification is to determine whether a slowing of subtle, early cognitive decline will impact longer-term clinical indicators.1 However, assessing subtle short-term cognitive change in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease is subject to measurement error, test version effects, regression to the mean and likely influenced by a number of age-related changes not specific to Alzheimer’s disease pathology, such as vascular changes, TDP-43 accumulation, neurotransmitter dysfunction, mood and sleep disturbances. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify and integrate biomarkers of disease progression that demonstrate changes during the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Given that tangle deposition occurs early, and spread beyond the medial temporal lobe is thought to occur downstream of initial amyloid accumulation,5,6 tau PET may hold promise as a measure of disease progression in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Tau PET’s close association with clinically meaningful measures such as cognitive function7 demonstrate the potential for tau PET to be used as a surrogate outcome for a clinical end point. If amyloid abnormalities are prevented, and amyloid is a key catalyst of tau accumulation, then therapeutics targeting amyloid should show a downstream effect mitigating further tau accumulation, as has been reported in trials of amyloid immunotherapy in symptomatic populations.8,9

Studies from multiple independent ageing cohorts have identified several sites where tau is elevated in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, including the medial temporal lobe (entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus and amygdala), ventral and lateral temporal cortices, along with precuneus, posterior cingulate and lateral parietal lobe.10–14 Although longitudinal tau PET studies in cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals have been limited by smaller sample sizes and short follow-up time, many studies to date show significant accumulation in CU samples in many of the same regions showing cross-sectional differences. However, these rates of accumulation in CU are subtle and the precise spatial pattern and the magnitude of rates vary across studies. Further, the degree to which regional tau accumulation is stronger in Aβ+ CU compared to Aβ− CU has varied across studies. These inconsistencies may be influenced by cohort demographics and PET processing methodologies, selection of target regions for examination, along with reference region.15 It is also expected that tau accumulation across different regions likely varies in the degree to which accumulation is amyloid-dependent. Thus, there is a need to evaluate the pattern and consistency of tau accumulation across multiple CU cohorts, and how these patterns relate to amyloid burden, in order to design optimal tau end points for clinical trials.

The goal of this work was to identify a collection of regions that would optimally capture early tau accumulation for use in a tau PET composite outcome in clinical trials for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. In three large cohorts of cognitively unimpaired older adults, we attempt to identify and validate regions with high rates of tau accumulation and estimate how these rates evolve over a continuous spectrum of baseline amyloid deposition. Optimal combinations of regions, tailored to varying ranges of baseline amyloid burden as hypothetical clinical trial inclusion criteria, were tested and validated.

Materials and methods

Participants

Data were obtained from three independent cohorts: the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s (A4) and companion study, Longitudinal Evaluation of Amyloid Risk and Neurodegeneration (LEARN),1 the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)16 and the Harvard Aging Brain study (HABS).17 All three studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants at each site. The population in this study included A4/LEARN, ADNI and HABS participants with measurements of both Aβ and tau PET and were cognitively unimpaired at the time of their baseline tau scan.

PET imaging

Amyloid data were processed using previously published cohort-specific processing streams. A4/LEARN (18F-florbetapir): amyloid PET data was processed using a PET-only pipeline, using an average across six cortical regions from the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas (anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, lateral parietal, precuneus, lateral temporal and medial orbital frontal) and was normalized to a whole-cerebellum reference region to create standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs).18 ADNI (18F-florbetapir): a global amyloid target region was calculated using four FreeSurfer defined regions on each subject’s corresponding structural T1 MRI (frontal, cingulate, lateral parietal and lateral temporal)19 and was normalized to a whole cerebellum reference region to create SUVRs. HABS (11C-PIB): a global amyloid target region was defined using three FreeSurfer defined regions on each subject’s corresponding structural T1 MRI (frontal, lateral temporal and retrosplenial) and was normalized using a cerebellar grey matter reference region to create SUVRs.20 Aβ positivity was defined using previously established thresholds—A4/LEARN: SUVR = 1.15 or an SUVR between 1.10 and 1.15 with a positive visual read,18 ADNI = 1.1021 for 18F-florbetapir measures and HABS: SUVR = 1.28 for 11C-PIB.17

Methods to acquire and process tau (18F-flortaucipir) PET image data in A4/LEARN,22 ADNI23 and HABS24 have been described previously. Thirty-five bilateral tau regions of interest from the FreeSurfer cortical Aparc atlas25 and subcortical Aseg atlas26 were analysed: the amygdala, entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, fusiform, banks of the superior temporal sulcus (bankssts), transverse temporal lobe, temporal pole and the inferior/middle/superior temporal lobes; the isthmus cingulate, insula, postcentral, rostral/caudal anterior cingulate, precuneus, posterior cingulate, supramarginal gyrus and the inferior/superior parietal lobe; the pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, pars opercularis, lateral/medial orbitofrontal, pre- and paracentral, rostral/caudal middle frontal, frontal pole and superior frontal lobe; and the cuneus, lingual, pericalcarine and lateral occipital lobe. A cerebellar grey matter reference region was used for all three cohorts. All analyses were repeated using a cerebral white matter reference region for comparison.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were done in each of the three cohorts, separately. First, the cross-sectional (A4/LEARN) associations between all 35 tau regions of interest and global Aβ were characterized, as well as the longitudinal (ADNI, HABS) changes over time in the same 35 regions of interest. To form the flortaucipir (FTP) PET composites, the A4/LEARN cohort was used for discovery—tau regions of interest were selected based on their strength of association with Aβ and then optimized and validated in the longitudinal cohorts, as detailed below.

In A4/LEARN, cross-sectional associations between global Aβ SUVR and each of the tau regions of interest were estimated using ordinary least-squares regression. FTP PET SUVRs from each of the 35 regions of interest were regressed on age, sex and Aβ SUVR. Natural cubic splines were used to capture any non-linear relationships between tau and Aβ. One internal spline knot, placed at the median Aβ SUVR, resulted in two estimated parameters for the relationship between tau and Aβ. An F-test was done to compare model fits with and without the two spline parameters for Aβ. The F statistic and residual degrees of freedom were used to approximate a correlation-like effect size (scale –1 to 1) and a 95% confidence interval for the relationship between Aβ and tau.

Longitudinal uptake in the FTP PET regions of interest in ADNI and HABS was modelled using mixed-effects regression assuming an independent correlation structure, conditional on a random intercept. FTP PET models included age, sex and time since baseline scan. Annual rates of change, 95% confidence intervals and effect sizes (−1 to 1 scale) were reported.

A second set of analyses was done to evaluate whether combinations of tau regions of interest into a composite could maximize the relationship between FTP PET and global Aβ PET as well as the longitudinal change of FTP PET. For these analyses, A4/LEARN was used for tau region of interest selection and ADNI and HABS were used for optimization and validation. In a first step using the A4/LEARN cohort, global Aβ PET SUVR was regressed on all 35 tau regions of interest simultaneously using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)27 to select a sparse group of tau regions of interest that maximized the joint association with global Aβ PET. In a second step, this group of tau regions of interest was then used in ADNI to find optimal region of interest weights to form a FTP PET composite that would maximize the effect size of change over time. In a third step, the HABS cohort was used to validate the optimized tau composite. The second and third steps were then repeated using HABS to optimize and ADNI to validate.

The optimization procedure was done using quasi-Newton constrained optimization28 to identify the weighted linear combination of tau regions of interest that would maximize the effect size of change over time. Weights were constrained to the interval [0, 1].

The accumulation rates of the tau regions of interest are likely to evolve over the course of Aβ accumulation with one set of tau regions having the highest rates in participants with low or medium levels of Aβ deposition and a different set of tau regions having the highest accumulation rates in participants with highly elevated levels of Aβ. To identify these different groups of tau regions of interest and assess their evolving importance, local regression was used to estimate each region of interest’s continuously changing weight throughout the spectrum of global Aβ PET. The optimization procedure was repeated within a moving window over global Aβ PET at baseline. At each iteration, optimization weights for the tau regions of interest were estimated giving the most importance to the participants with baseline Aβ PET levels in the centre of the window, resulting in continuously changing weights across the spectrum of baseline Aβ PET. This optimization procedure was done in ADNI and validated in HABS and vice versa.

To assess and validate the performance of the optimized FTP PET composites, sample size calculations were done for various clinical trial scenarios using the optimized composite, a temporal lobe composite and a global tau composite as outcome measures. The required sample size to achieve 80% power using (i) the optimized composite; (ii) a temporal lobe composite comprising an equal weight combination of the entorhinal cortex, amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, fusiform, and inferior and middle temporal lobe29; and (iii) a global composite comprising an equal weight combination of all 35 regions of interest were compared. Sample size estimates are shown for 18- and 24-month trials, with tau scans done every 12 months (every 9 months for 18-month trials), over a range of assumed treatment effect sizes (20–50%), an assumed 25% dropout rate and at three levels of baseline Aβ PET: 20–40 centiloids (CLs; 1.1–1.23 SUVR in ADNI; 1.22–1.40 in HABS), 30–50 CLs (1.16–1.28 SUVR in ADNI; 1.31–1.50 in HABS) and 40+ CLs (>1.22 SUVR in ADNI; >1.40 SUVR in HABS).20 These CL levels were selected given the current design of prevention trials, with some approaches geared toward the selection of clearly elevated Aβ+ CU18 and others geared toward CU with intermediate levels of amyloid PET values (AHEAD3–45, NCT04468659). FTP PET accumulation in participants with low Aβ levels (<10 CLs) was also evaluated. In ADNI, <10 CLs corresponded to Aβ PET SUVR <1.05 and in HABS, Aβ PET SUVR <1.13. Sample size calculations were done using lmmpower from the longpower R package.

Missingness was assessed by regressing a missing indicator for FTP PET on interactions between demographics and Aβ positivity with time, using logistic mixed-effects regression. Cohort characteristic associations with baseline Aβ status were assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All analyses were done in R v4.1.1 (www.r-project.org).

Data availability

All data are publicly available.

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 1057 participants were included, with 447 from A4/LEARN (392 Aβ+, 55 Aβ−), 420 from ADNI (149 Aβ+, 271 Aβ−) and 190 from HABS (59 Aβ+, 131 Aβ−). The Aβ+ groups were older, had a higher frequency of APOE ɛ4-positivity and performed significantly worse on several cognitive tests at baseline, compared to Aβ− groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Aβ+ | Aβ− | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A4 | n = 392 | n = 55 | |

| Age | 72.1 (4.8) | 69.7 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 225 (57.4) | 32 (58.2) | >0.99 |

| Education, years | 16.2 (2.9) | 16.6 (2.8) | 0.29 |

| APOE ɛ4+, n (%) | 220 (57.1) | 14 (25.5) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 28.6 (1.4) | 29.0 (1.0) | 0.05 |

| Logical memory delayed recall | 11.4 (3.4) | 13.0 (3.1) | 0.002 |

| ADNI | n = 149 | n = 271 | |

| Age | 75.1 (7.4) | 71.9 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 92 (61.7) | 158 (58.3) | 0.53 |

| Education, years | 16.6 (2.4) | 16.9 (2.3) | 0.22 |

| APOE ɛ4+, n (%) | 74 (52.1) | 64 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 28.9 (1.4) | 29.2 (1.1) | 0.03 |

| Logical memory delayed recall | 13.4 (3.7) | 13.5 (3.7) | 0.82 |

| HABS | n = 59 | n = 131 | |

| Age | 77.9 (6.0) | 75.7 (6.4) | 0.01 |

| Female, n (%) | 35 (59.3) | 77 (58.8) | >0.99 |

| Education, years | 16.4 (2.8) | 16.0 (3.2) | 0.57 |

| APOE ɛ4+, n (%) | 35 (61.4) | 18 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 29.0 (1.1) | 29.3 (1.0) | 0.04 |

| Logical memory delayed recall | 15.6 (3.6) | 16.4 (3.7) | 0.15 |

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Regional 18F-flortaucipir in A4/LEARN

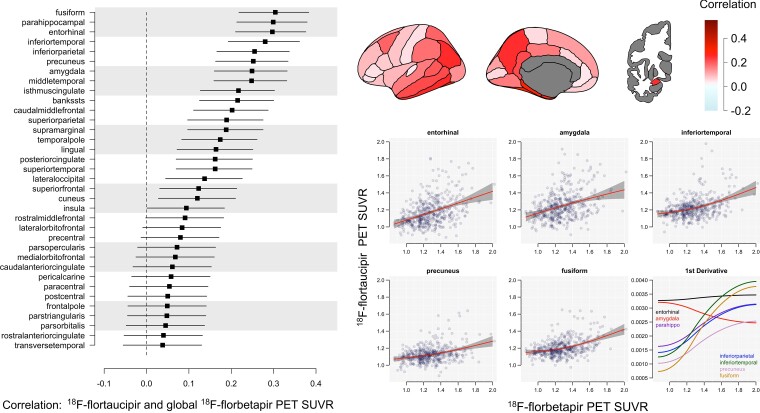

Effect sizes for the relationship between global Aβ and each tau PET region of interest are shown in Fig. 1. Fusiform gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus and entorhinal cortex showed the strongest correlation with Aβ, followed closely by inferior temporal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, precuneus, amygdala and middle temporal cortex. Plots of regional FTP PET SUVR by global Aβ PET SUVR are also shown in Fig. 1, lower right, as well as the first derivative of these curves—showing the change in slope of the FTP PET curves for incremental increases of Aβ. Note the high increase in the slope for FTP PET in the entorhinal cortex and amygdala compared with all other regions (Fig. 1, lower right).

Figure 1.

Regional FTP in A4/LEARN. Effect sizes on a correlation scale (−1 to 1) and 95% confidence intervals for the relationship between regional tau PET and global Aβ are shown on the left. The same effect sizes are depicted in the top right. Plots of tau PET SUVR by global Aβ with 95% confidence intervals in shaded grey are shown for several regions of interest on the lower right. The first derivatives of the tau PET curves showing the change in slope of the tau curves for incremental increases of Aβ are plotted on the bottom right.

Penalized regression with the LASSO was then used to select a sparse set of FTP PET regions of interest that would jointly maximize the association between tau PET and Aβ. Seven regions of interest were selected: entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, fusiform, inferior parietal cortex, precuneus, inferior temporal cortex and amygdala. These seven selected regions were then assessed further in ADNI and HABS to find and optimize composite weights.

Regional 18F-flortaucipir in ADNI and HABS

In ADNI, 284 participants had one FTP PET scan, 88 had two scans, 42 had three scans and six had four or more scans. Among the 136 participants with multiple scans, Aβ− participants were followed for 1.73 years on average (range 0.59–3.70), which was comparable to Aβ+ participants, followed for 1.61 years (range 0.77–3.62, P = 0.28). Demographics were not associated with missing tau PET over time, age [odds ratio (OR) = 0.98, P = 0.11], sex (OR = 0.90, P = 0.53) or education (OR = 1.00, P = 0.95). Aβ positivity was associated with a lower likelihood of missing a tau scan (OR = 0.52, P < 0.001).

In HABS, 62 participants had one FTP PET scan, 108 had two scans, and 20 had three scans. Among the 128 participants with multiple scans, Aβ− participants were followed for 2.52 years on average (range 1.25–5.56), which was comparable to Aβ+ participants, followed for 2.32 years (range 1.20–4.90, P = 0.67). Neither sex (OR = 1.09, P = 0.14), education (OR = 1.03, P = 0.11) nor Aβ positivity (OR = 1.05, P = 0.71) were associated with missing tau PET over time. A 1 SD increase in age at baseline was associated with a higher likelihood of missing tau PET over time (OR = 1.14, P = 0.04).

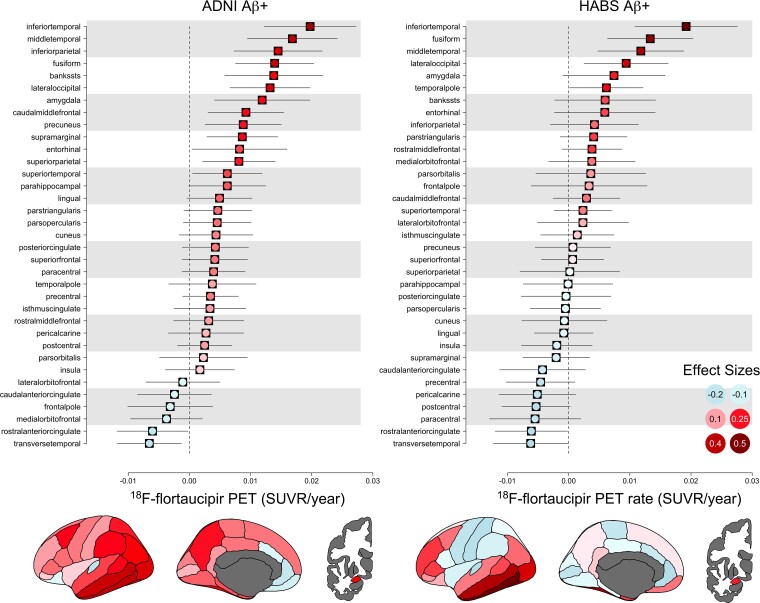

Annual rates and effect sizes of longitudinal change in FTP PET in ADNI and HABS Aβ+ participants are shown in Fig. 2. The largest effect sizes in both cohorts were in the inferior temporal cortex, middle temporal cortex and fusiform gyrus, with the inferior temporal cortex a clear standout. Of the top 10 highest rated regions of interest, the cohorts had seven in common: inferior and middle temporal cortex, fusiform gyrus, amygdala, inferior parietal lobe, banks of the superior temporal sulcus and the lateral occipital lobe.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal FTP PET in ADNI and HABS Aβ+ participants. Annual rates and effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for all 35 regions of interest are shown. Effect sizes (−1 to 1 scale) are colour-coded.

Locally optimized composite weights

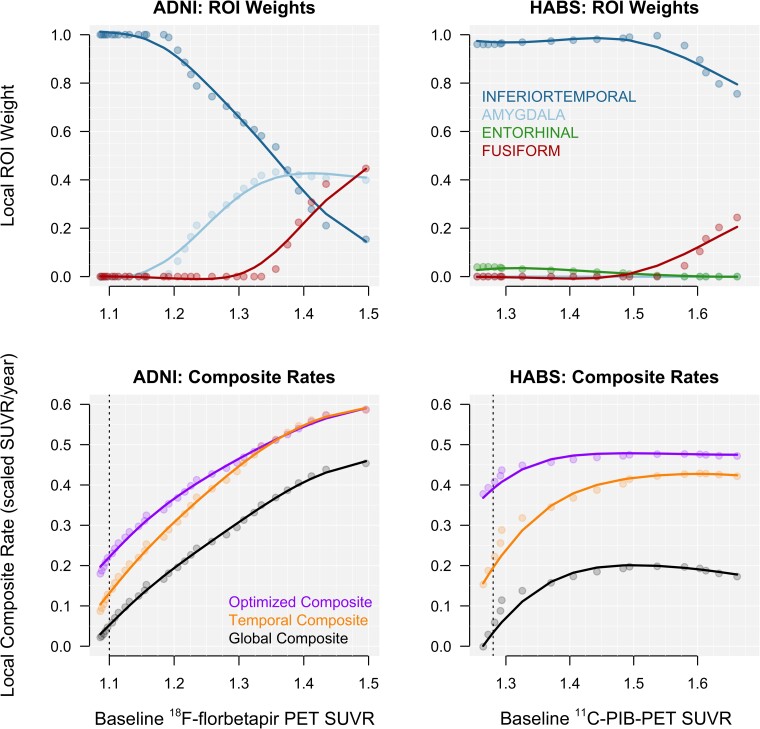

To assess how the joint importance of each region of interest changes with continuously increasing baseline global Aβ PET, local composite weights were estimated. Local weights for the seven regions of interest selected from A4/LEARN that optimize the effect size of longitudinal change are plotted against baseline Aβ for ADNI and HABS in the top row of Fig. 3. Four regions had non-zero weights: the inferior temporal cortex, amygdala, fusiform gyrus and the entorhinal cortex. Note the dominance of the inferior temporal cortex in both cohorts, as well as the increasing weight of the fusiform gyrus at higher levels of baseline Aβ in both cohorts.

Figure 3.

Locally estimated composite weights and corresponding rates. Locally estimated composite weights for each of the seven regions of interest selected in A4/LEARN with non-zero weights are plotted in the top row. The corresponding longitudinal rates for the weighted composites are plotted in the bottom row. Rates were scaled to the mean and standard deviation of the composite in the Aβ− group. The threshold for Aβ positivity is represented by the vertical, dotted line for each cohort.

The combined composite weights across ADNI and HABS were 99% inferior temporal cortex and 1% entorhinal cortex for 20–40 CL; 95% inferior temporal cortex and 5% amygdala for 30–50 CL; and 53% inferior temporal cortex, 31% amygdala and 16% fusiform for 40+ CL. The composite rates using the corresponding local weights are plotted against baseline Aβ in the bottom row of Fig. 3.

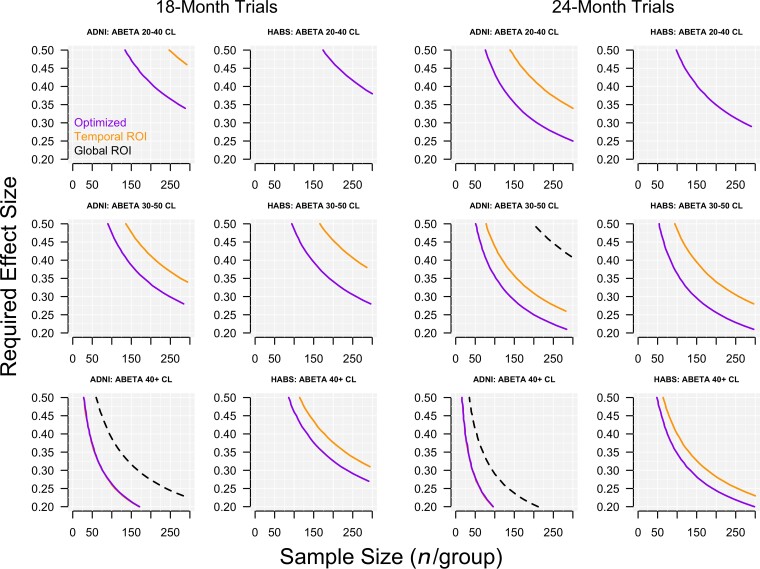

Required effect size and sample size for clinical trials

The effect sizes required to achieve 80% power with a given sample size for 18- and 24-month trials are plotted in Fig. 4. Optimized composites using local weights are compared to a temporal lobe composite and a global tau composite in three ranges of baseline Aβ PET (20–40 CLs, 30–50 CLs and 40+ CLs). At levels of baseline Aβ in the 20–40 CL range, a sample size of 200 per group required a drug effect of just below 0.40 (40% slowing of tau accumulation compared with placebo) in ADNI and just below 0.45 in HABS for an 18-month trial using the optimized composite. Neither the temporal nor global composite reached 80% with 200 per group with an effect size under 0.5. In the low and intermediate baseline Aβ CL ranges (20–40, 30–50), the temporal composite required a 50–100% larger sample size compared with the optimized composite. In the highest baseline Aβ CL range (40+), the advantage of the optimized composite over the temporal lobe composite diminished with the temporal composite requiring an additional 30% in sample size compared with the optimized composite in HABS and no difference between the two composites in ADNI.

Figure 4.

Required treatment effect and sample size calculations. Required treatment effect sizes are plotted against sample sizes in 18- and 24-month trials at three levels of baseline Aβ. The plotted curves show the combinations of required treatment effect and sample size to achieve 80% power for the three composites—the optimized composite, the temporal composite, and the global composite. In the bottom row, the temporal composite is barely visible, but is plotted underneath the optimized composite for ADNI.

Inferior temporal cortex

With the observation that the inferior temporal cortex was the strongest accumulating region in both cohorts and dominated the weight of the composite, post hoc analyses of sample size and required treatment effect using the inferior temporal cortex alone were done. The required effect size and sample size estimates to achieve 80% power were similar when using the optimized composite and the inferior temporal cortex alone. Slight differences of 0.01–0.02 in required effect size for a given sample size were seen in the 40+ CL range. In ADNI, there was a slight advantage with the optimized composite and in HABS there was a slight advantage with the inferior temporal cortex.

Tau accumulation in participants with Aβ < 10 CLs

In ADNI, 122 participants had low baseline Aβ PET levels (<1.05 florbetapir SUVR, or approximately <10 CLs). There were no regions of interest with significant accumulation (P-values > 0.21). The largest effect sizes, although not significant, were in the inferior temporal cortex [β = 0.005 SUVR/year, P = 0.21, effect size (ES) = 0.15], middle temporal cortex (β = 0.005, P = 0.23, ES = 0.15), entorhinal cortex (β = 0.005, P = 0.25, ES = 0.14), lateral occipital cortex (β = 0.005, P = 0.27, ES = 0.13) and banks of the superior temporal sulcus (β = 0.006, P = 0.29, ES = 0.12).

In HABS, 44 participants had low baseline Aβ PET levels (<1.13 PIB SUVR, or approximately <10 CLs). There were no regions of interest with significant accumulation (P-values > 0.21). The largest effect sizes, although not significant, were in the inferior temporal cortex (β = 0.004, P = 0.18, ES = 0.24), pars orbitalis (β = 0.005, P = 0.20, ES = 0.22), pars triangularis (β = 0.004, P = 0.26, ES = 0.20), middle temporal cortex (β = 0.003, P = 0.31, ES = 0.18) and caudal anterior cingulate (β = 0.003, P = 0.41, ES = 0.15).

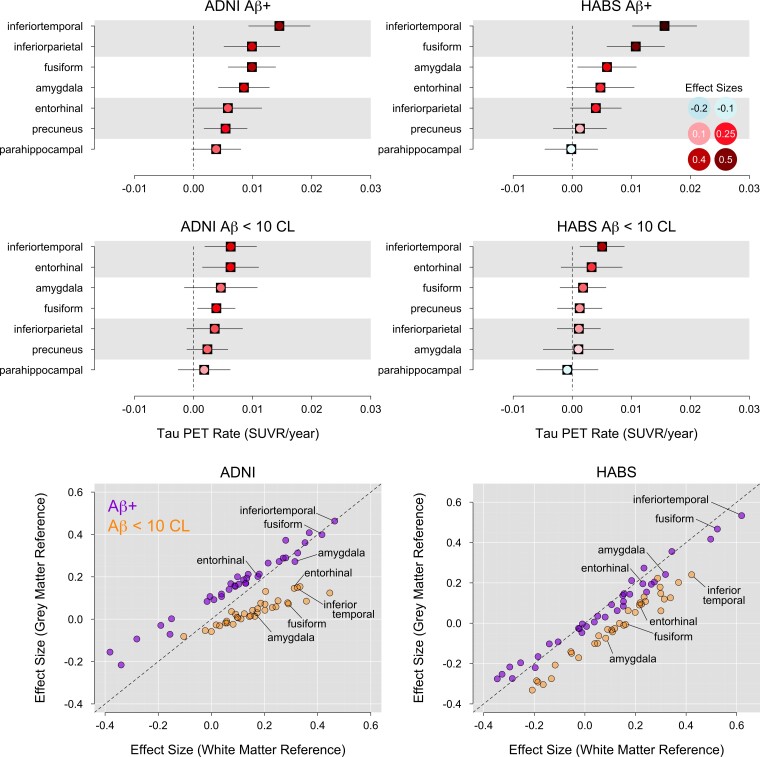

Cerebral white matter reference region

Effect sizes of longitudinal change in the seven regions of interest selected from A4/LEARN were similar when using a grey or white matter reference region in Aβ+ participants (Fig. 5). However, effect sizes of change in FTP PET among participants with low baseline Aβ levels (<10 CLs) were larger and significantly greater than zero in several regions of interest when using the white matter reference region (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

White matter reference region. Accumulation rates and effect sizes of longitudinal change in the seven regions of interest selected from A4 using the cerebral white matter reference region are shown for Aβ+ participants in the top row and low Aβ (<10 CLs) participants in the middle row. Effect sizes using the grey matter reference region are plotted against the effect sizes using the white matter reference region in the bottom row, in Aβ+ and low Aβ participants, separately. The dashed line is the identity line.

In ADNI, participants with low baseline Aβ levels showed significant accumulation in the inferior temporal cortex (β = 0.006, P = 0.007, ES = 0.33), entorhinal cortex (β = 0.006, P = 0.01, ES = 0.31) and fusiform gyrus (β = 0.004, P = 0.02, ES = 0.28), but not in the amygdala (β = 0.004, P = 0.18, ES = 0.15). This is in contrast to the lack of significant results when using the grey matter reference region in participants with low baseline Aβ levels.

In HABS, participants with low baseline Aβ levels showed significant accumulation in the inferior temporal cortex (β = 0.005, P = 0.01, ES = 0.42), but not in the entorhinal cortex (β = 0.003, P = 0.22, ES = 0.22), fusiform gyrus (β = 0.002, P = 0.36, ES = 0.16) or amygdala (β = 0.001, P = 0.73, ES = 0.06).

Discussion

There was consensus across the three cohorts regarding sites of the strongest associations of FTP PET with baseline Aβ levels (A4/LEARN) and high rates of tau accumulation over time (ADNI, HABS). The inferior temporal cortex, fusiform gyrus and middle temporal cortex had the largest effect sizes of accumulation in both ADNI and HABS, when considered individually. When tau regions of interest were combined to find weights to maximize the effect size of tau change over time, both ADNI and HABS exhibited a similar pattern—inferior temporal cortex, almost exclusively, was optimal for participants with mildly elevated Aβ levels. In participants with intermediate and high levels of Aβ, the composite weight for the inferior temporal cortex decreased as the weight for the fusiform gyrus increased, in both longitudinal cohorts. Specific to ADNI, the composite weight for the amygdala also increased in participants with higher Aβ levels. However, the increased weights for the fusiform and amygdala made only a negligible difference on the magnitude of the effect size compared with inferior temporal cortex alone. In the validation samples, the optimized composites had higher rates and effect sizes of change compared with the temporal and global composites in all cases except in ADNI participants with the highest Aβ levels, in which the optimized and temporal composites performed similarly. The increased effect sizes captured by the optimized composite, driven by the inferior temporal cortex, resulted in decreased required treatment effect sizes and sample sizes in all three Aβ groups (20–40 CLs, 30–50 CLs, 40+ CLs) in HABS and in the 20–40 and 30–50 CL groups in ADNI.

At high baseline levels of Aβ, the temporal and optimized composite approached the same effect size, indicating that the combination of regions in the temporal composite had converged to the same magnitude of effect. The largest effect size of FTP PET accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease may be captured by the inferior temporal cortex alone, although the increasing weights of additional regions suggest that as participants progress, accumulation may further accelerate, starting with the fusiform gyrus and possibly the amygdala.

Rate and effect size estimates in high-accumulation regions of interest were similar whether using a grey matter or white matter reference region in Aβ+ participants. In low Aβ participants (<10 CLs), significant accumulation was only observed when using a white matter reference, while none of the regions of interest showed significant accumulation when using a grey matter reference region.

The regions of interest selected in A4/LEARN for their joint cross-sectional association with global Aβ were among the highest longitudinally accumulating regions for both ADNI and HABS. The inferior temporal cortex, fusiform gyrus and entorhinal cortex have been consistently identified as potential sites of early and rapid tau accumulation, although to varying degrees.15 In addition, Jack et al.,30 Harrison et al.32 and Pontecorvo et al.33 reported strong posterior and isthmus cingulate tau accumulation. Posterior cingulate and isthmus cingulate tau accumulation was less consistent in ADNI and HABS, with little accumulation in these regions observed in HABS and intermediate levels of accumulation observed in ADNI (Fig. 2). Harrison et al.32 also reported high accumulation rates in the isthmus cingulate and inferior frontal gyrus, in addition to the inferior temporal cortex, and entorhinal cortex in both PIB-positive and -negative older cognitively unimpaired adults.

Post-mortem studies identify the medial temporal lobe, specifically the transentorhinal region, as the first site of neurofibrillary tangles.37 Cross-sectional PET studies have also shown the entorhinal cortex to be one of the earliest sites of tau accumulation38 as well as a strong predictor of cognitive impairment.7 Although the entorhinal cortex was among the most strongly correlated regions with global Aβ in the cross-sectional setting of A4/LEARN, it was not among the highest accumulating regions longitudinally in either ADNI or HABS and contributed minimally to the composites (0–5% of the composite weight in HABS). This low weighting of the entorhinal cortex when combining tau signal across multiple regions of interest coincides with Jack et al.,30 where despite differences in accumulation rates between Aβ+ and Aβ− groups, only the fusiform gyrus and posterior cingulate were selected as the optimal joint classifier of Aβ status. This was somewhat unexpected given the role of the entorhinal cortex in early tau accumulation, although large differences in entorhinal tau between Aβ+ and Aβ− groups observed cross-sectionally may represent a lifetime of moderate accumulation rather than a high rate of accumulation over a short period of two or three years. Sanchez et al.35 used mixture models to estimate the frequency of regions with elevated tau in CU participants with low and high Aβ, separately. In a region capturing Brodmann area (BA) 35 as well as portions of BA36 and lateral entorhinal cortex, termed the ‘rhinal cortex’, elevated tau occurred more frequently compared to all other regions of interest in high Aβ participants. The parahippocampal gyrus was the second most frequent region of interest with elevated tau, with only a handful of participants with elevated tau in inferior temporal cortex and fusiform gyrus. However, in these same participants, the inferior temporal cortex had a higher accumulation rate than both the rhinal cortex and the parahippocampal gyrus, highlighting the difference between the rate of accumulation over time and the frequency of elevated levels beyond a threshold. The pattern in low Aβ participants was similar, with the highest frequency of elevated tau in the rhinal cortex and second highest in the parahippocampal gyrus and no participants with elevated inferior temporal cortex tau levels. In these same low Aβ participants, inferior temporal cortex and rhinal cortex showed the same, strongly significant rate of accumulation. The fusiform gyrus also showed significant accumulation, while accumulation in the parahippocampal gyrus was not significant. Despite frequently elevated levels of tau in the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus, these elevations do not necessarily translate to rapid rates of accumulation in participants with either low or high Aβ. This early accumulation of tau in medial temporal regions such as the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus may represent a different process compared with the later, more rapid accumulation in the inferior temporal cortex. The former may or may not lead to Alzheimer’s dementia, limited temporal lobe tau accumulation, symptomatic primary age-related tauopathy or another tauopathy altogether.39

In A4/LEARN cross-sectional data, the immediate increase in entorhinal cortex tau levels with incremental increases of global Aβ starting from the lowest Aβ levels appear in contrast to other regions, except the amygdala (Fig. 1). The entorhinal cortex and amygdala appear systematically different with early linear increases whereas other regions show a more gradual increase until well into the Aβ+ range. This pattern is clear in the plot of first derivatives (Fig. 1). However, the amygdala had a higher accumulation rate compared with the entorhinal cortex in both ADNI and HABS, and was heavily weighted in the ADNI FTP PET composite at intermediate to high levels of baseline Aβ. The weights for the amygdala remained near zero at all levels of Aβ in HABS, despite the amygdala being among the five fastest accumulating regions in Aβ+ participants (Fig. 2). However, the ADNI-optimized composite, with 40% of the signal coming from the amygdala at intermediate/high levels of Aβ, performed well in HABS. Tau accumulation in the amygdala has not been well characterized, despite evidence of increased rates occurring early and prior to cognitive impairment.34,36,40,41

In hypothetical clinical trial scenarios, the temporal composite required a larger sample size for a given treatment effect to achieve 80% power compared to the optimized composite, in all scenarios except the highest Aβ participants in ADNI. While the temporal composite included the highest accumulating regions in both cohorts (inferior and middle temporal cortex, fusiform, amygdala), it also included the entorhinal cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus, reducing the rate and effect size, particularly in participants with only mildly elevated or intermediate levels of Aβ. The temporal composite required a 50–80% larger sample size compared with the optimized composite in the 20–40 and 30–50 CL groups in both cohorts. In the 40+ CL groups, the temporal composite required a 35% increase in sample size compared to the optimized composite in HABS, while there was no difference between the temporal and optimized composites in ADNI. The global composite failed to reach 80% power for most scenarios and require larger sample sizes and treatment effects than either the temporal or optimized composite.

In participants with the lowest Aβ levels (<10 CLs), the only region observed to significantly accumulate tau in both longitudinal cohorts was the inferior temporal cortex, and was only significant when using the white matter reference region. Entorhinal cortex and fusiform gyrus were also significant in ADNI, but again only with the white matter reference region. The rate of inferior temporal cortex tau accumulation was 0.005 SUVR/year (P = 0.21) when using the grey matter reference region and 0.006 SUVR/year (P = 0.007) when using the white matter reference region. While there is a 20% rate increase with the white matter reference, the main difference appears to be the effect size, due to decreased variance with the white matter reference region. Although non-significant, the estimate of accumulation with the grey matter reference is not negligible, and along with the significant estimates using the white matter reference region, supports the notion of accumulating tau in participants with low Aβ, and in some cases may be related to primary age-related tauopathy39 or suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathology.42

A limitation of this study is the difficulty in assessing hippocampal tau due to the known off-target binding that occurs with the 18F-flortaucipir ligand. It is possible that the hippocampus is an important contributor to a composite of early tau accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. It is also unknown whether off-target binding plays a role in the significant estimates of tau accumulation in participants with low Aβ. Although accumulation in the same regions in participants with elevated Aβ is supported by neuropathology studies, less is known about tau accumulation in participants without significant Aβ deposition. It is also possible that age-related mineralization inflates the estimates of accumulation.15,43 FTP PET values are relatively low in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. It is possible that with further follow-up, additional sites of tau accumulation beyond the temporal lobe may become important to consider for a composite end point, especially in participants with highly elevated Aβ and an increasing likelihood of cognitive impairment.

CSF tau has been proposed as an earlier marker of tau pathology compared with tau PET.44 By showing that a higher proportion of individuals were CSF tau-positive compared to the proportion that were tau PET-positive, at a selected threshold cross-sectionally, observable changes in CSF tau were argued to precede observable changes in tau PET. With similar methods,35 the entorhinal cortex was shown to have a higher proportion of participants with abnormal levels of tau compared to other regions, despite having a slower accumulation rate (compared to inferior temporal cortex, for example) during follow-up. Thus, the high proportion of biomarker-positive individuals suggesting early change does not necessarily translate to a rapid short-term accumulation rate that would provide the effect size to power a clinical trial. A head-to-head comparison between longitudinal CSF and longitudinal tau PET will be important to evaluate the comparative power for a clinical trial application. Additionally, spatial information may be important to evaluate a treatment effect, which would need to be done via tau PET.

The focus of early tau accumulation has been on the medial temporal lobe, resulting from the repeated observation that the entorhinal cortex is the first region to show abnormal levels of tau with age. However, these abnormal levels do not appear to be the result of a high rate of accumulation in the short term, but possibly a more moderate rate occurring early with respect to age. The inferior temporal cortex, a site of both Aβ deposition as well as tau accumulation, may act as a central hub for rapid, widespread tau propagation due to local Aβ–tau interaction.45 In both ADNI and HABS, the inferior temporal cortex showed a 2- to 3-fold rate and effect size increase compared with both the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus in participants with elevated Aβ. While the entorhinal cortex plays a central role in the early appearance of tau, it may be the inferior temporal cortex that is the critical region for rapid tau accumulation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgements

The A4 study is a secondary prevention trial in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, aiming to slow cognitive decline associated with brain amyloid accumulation in clinically normal older individuals. The A4 study is funded by a public–private philanthropic partnership, including funding from the National Institutes of Health–National Institute on Aging (U19AG010483; R01AG063689), Eli Lilly and Company, Alzheimer’s Association, Accelerating Medicines Partnership, GHR Foundation, an anonymous foundation and additional private donors, with in-kind support from Avid, Cogstate, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, US Against Alzheimer’s disease and Foundation for Neurologic Diseases. The companion observational Longitudinal Evaluation of Amyloid Risk and Neurodegeneration (LEARN) study is funded by the Alzheimer’s Association and GHR Foundation. The A4 and LEARN Studies are led by Reisa Sperling at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School and Paul Aisen at the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute (ATRI), University of Southern California. The A4 and LEARN Studies are coordinated by ATRI at the University of Southern California, and the data are made available through the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. The participants screening for the A4 study provided permission to share their de-identified data in order to advance the quest to find a successful treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. We would like to acknowledge the dedication of all the participants, the site personnel, and all of the partnership team members who continue to make the A4 and LEARN Studies possible. The complete A4 study team list is available on: a4study.org/a4-study-team.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; IXICO Ltd; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private-sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. This research was also supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P30 AG010129, K01 AG030514 and R01 AG049750. Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf (also available as supplemental material).

Contributor Information

Philip S Insel, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Christina B Young, Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Paul S Aisen, Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Keith A Johnson, Department of Neurology, Harvard Aging Brain Study, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Reisa A Sperling, Department of Neurology, Harvard Aging Brain Study, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Neurology, Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Elizabeth C Mormino, Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Michael C Donohue, Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, San Diego, CA, USA.

Funding

This research was also supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P30 AG010129, K01 AG030514 and R01 AG049750.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1. Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, et al. The A4 study: Stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:228fs13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Insel PS, Weiner M, Mackin RS, et al. Determining clinically meaningful decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2019;93:e322–e333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karran E, De Strooper B. The amyloid hypothesis in Alzheimer disease: New insights from new therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:306–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knopman DS, Jones DT, Greicius MD. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Selkoe DJ. Toward a comprehensive theory for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;924:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, et al. Predicting diagnosis and cognition with 18 F-AV-1451 tau PET and structural MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:570–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, et al. Donanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1691–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sperling RA, Mormino EC, Schultz AP, et al. The impact of amyloid-beta and tau on prospective cognitive decline in older individuals. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lockhart SN, Schöll M, Baker SL, et al. Amyloid and tau PET demonstrate region-specific associations in normal older people. Neuroimage. 2017;150:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, et al. Tau-PET uptake: Regional variation in average SUVR and impact of amyloid deposition. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;6:21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Betthauser TJ, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, et al. Amyloid and tau imaging biomarkers explain cognitive decline from late middle-age. Brain. 2020;143:320–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schöll M, Lockhart SN, Schonhaut DR, et al. PET Imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron. 2016;89:971–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young CB, Landau SM, Harrison TM, Poston KL, Mormino EC. Influence of common reference regions on regional tau patterns in cross-sectional and longitudinal [18F]-AV-1451 PET data. Neuroimage. 2021;243:118553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mueller SG, Weiner MW, Thal LJ, et al. Ways toward an early diagnosis in Alzheimer ‘s disease: The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI). Alzheimers Dement. 2005;1:55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dagley A, LaPoint M, Huijbers W, et al. Harvard aging brain study: Dataset and accessibility. Neuroimage. 2017;144:255–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sperling R, Donohue M, Raman R, et al. Association of factors with elevated amyloid burden in clinically normal older individuals. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, et al. Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:578–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farrell ME, Jiang S, Schultz AP, et al. Defining the lowest threshold for amyloid-PET to predict future cognitive decline and amyloid accumulation. Neurology. 2021;96:e619–e631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joshi AD, Pontecorvo MJ, Clark CM, et al. Performance characteristics of amyloid PET with florbetapir F 18 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal subjects. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young CB, Winer JR, Younes K, et al. Divergent cortical tau positron emission tomography patterns among patients with preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79:592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maass A, Landau S, Baker SL et al. Comparison of multiple tau-PET measures as biomarkers in aging and Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage 2017;157:448–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: Neurotechnique automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc B. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Byrd R, Lu P, Nocedal J, Zhu C. A limited memory algorithm for bound constrained optimization. SIAM J Sci Comput. 1995;16:1190–1208. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Schwarz CG, et al. Longitudinal tau PET in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2018;141:1517–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adams JN, Harrison TM, Maass A, Baker SL, Jagust WJ. Distinct factors drive the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology in older adults. J Neurosci. 2022;42:1352–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harrison TM, La Joie R, Maass A, et al. Longitudinal tau accumulation and atrophy in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2018;85:229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD, Kennedy I, et al. A multicentre longitudinal study of flortaucipir (18F) in normal ageing, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Brain. 2019;142:1723–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Insel PS, Mormino EC, Aisen PS, Thompson WK, Donohue MC. Neuroanatomical spread of amyloid β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for primary prevention. Brain Commun. 2020;2:fcaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanchez JS, Becker JA, Jacobs HIL, et al. The cortical origin and initial spread of medial temporal tauopathy in Alzheimer’s disease assessed with positron emission tomography. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabc0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leuzy A, Smith R, Cullen NC, et al. Biomarker-based prediction of longitudinal tau positron emission tomography in Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021;79:149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berron D, Vogel JW, Insel PS, et al. Early stages of tau pathology and its associations with functional connectivity, atrophy and memory. Brain. 2021;144:2771–2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, et al. PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: A complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krishnadas N, Bozinovski S, Villemagne VL, et al. 18 F-MK6240 longitudinal tau PET in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:e053185. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jack CR, Knopman DS, Chételat G, et al. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology—Concept and controversy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lowe VJ, Curran G, Fang P, et al. An autoradiographic evaluation of AV-1451 tau PET in dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mattsson-Carlgren N, Andersson E, Janelidze S, et al. Aβ deposition is associated with increases in soluble and phosphorylated tau that precede a positive tau PET in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee WJ, Brown JA, Kim HR, et al. Regional aβ–tau interactions promote onset and acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease tau spreading. Neuron. 2022;110:1932–1943.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are publicly available.