Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is common in adults, and often has a detrimental impact upon physical ability, well‐being, and quality of life. Previous reviews have shown that certain antidepressants may be effective in reducing pain with some benefit in improving patients’ global impression of change for certain chronic pain conditions. However, there has not been a network meta‐analysis (NMA) examining all antidepressants across all chronic pain conditions.

Objectives

To assess the comparative efficacy and safety of antidepressants for adults with chronic pain (except headache).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, AMED and PsycINFO databases, and clinical trials registries, for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of antidepressants for chronic pain conditions in January 2022.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs that examined antidepressants for chronic pain against any comparator. If the comparator was placebo, another medication, another antidepressant, or the same antidepressant at different doses, then we required the study to be double‐blind. We included RCTs with active comparators that were unable to be double‐blinded (e.g. psychotherapy) but rated them as high risk of bias. We excluded RCTs where the follow‐up was less than two weeks and those with fewer than 10 participants in each arm.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors separately screened, data extracted, and judged risk of bias. We synthesised the data using Bayesian NMA and pairwise meta‐analyses for each outcome and ranked the antidepressants in terms of their effectiveness using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA). We primarily used Confidence in Meta‐Analysis (CINeMA) and Risk of Bias due to Missing Evidence in Network meta‐analysis (ROB‐MEN) to assess the certainty of the evidence. Where it was not possible to use CINeMA and ROB‐MEN due to the complexity of the networks, we used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Our primary outcomes were substantial (50%) pain relief, pain intensity, mood, and adverse events. Our secondary outcomes were moderate pain relief (30%), physical function, sleep, quality of life, Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), serious adverse events, and withdrawal.

Main results

This review and NMA included 176 studies with a total of 28,664 participants. The majority of studies were placebo‐controlled (83), and parallel−armed (141). The most common pain conditions examined were fibromyalgia (59 studies); neuropathic pain (49 studies) and musculoskeletal pain (40 studies). The average length of RCTs was 10 weeks. Seven studies provided no useable data and were omitted from the NMA. The majority of studies measured short‐term outcomes only and excluded people with low mood and other mental health conditions.

Across efficacy outcomes, duloxetine was consistently the highest‐ranked antidepressant with moderate‐ to high‐certainty evidence. In duloxetine studies, standard dose was equally efficacious as high dose for the majority of outcomes. Milnacipran was often ranked as the next most efficacious antidepressant, although the certainty of evidence was lower than that of duloxetine. There was insufficient evidence to draw robust conclusions for the efficacy and safety of any other antidepressant for chronic pain.

Primary efficacy outcomes

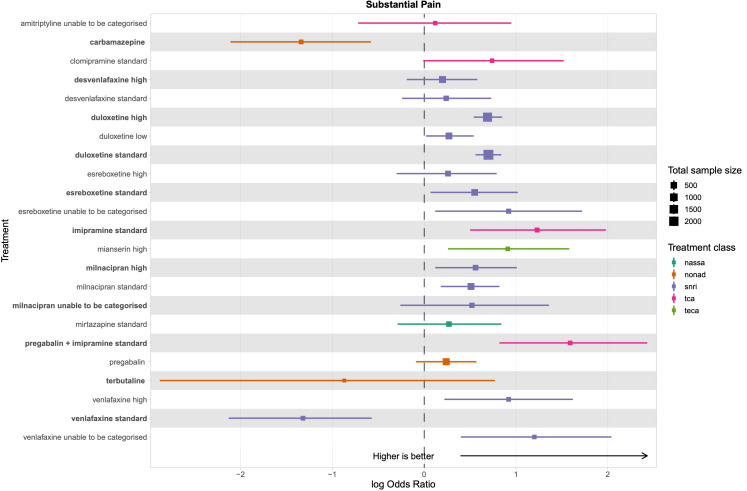

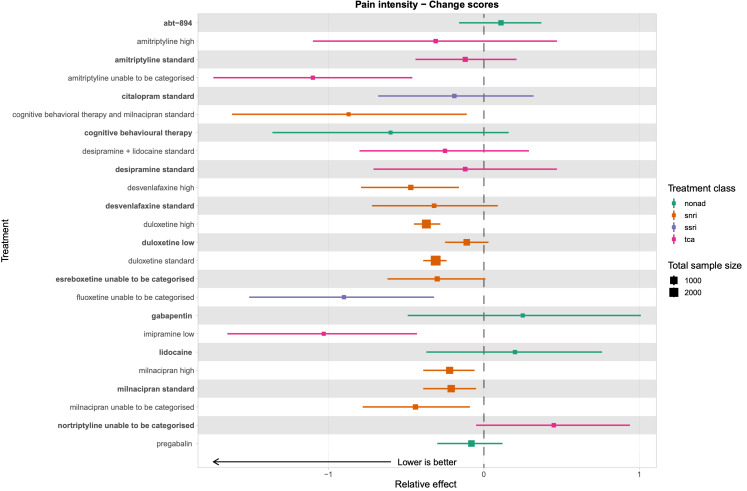

Duloxetine standard dose (60 mg) showed a small to moderate effect for substantial pain relief (odds ratio (OR) 1.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.69 to 2.17; 16 studies, 4490 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and continuous pain intensity (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.31, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.24; 18 studies, 4959 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). For pain intensity, milnacipran standard dose (100 mg) also showed a small effect (SMD −0.22, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.06; 4 studies, 1866 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). Mirtazapine (30 mg) had a moderate effect on mood (SMD −0.5, 95% CI −0.78 to −0.22; 1 study, 406 participants; low‐certainty evidence), while duloxetine showed a small effect (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.1; 26 studies, 7952 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence); however it is important to note that most studies excluded participants with mental health conditions, and so average anxiety and depression scores tended to be in the 'normal' or 'subclinical' ranges at baseline already.

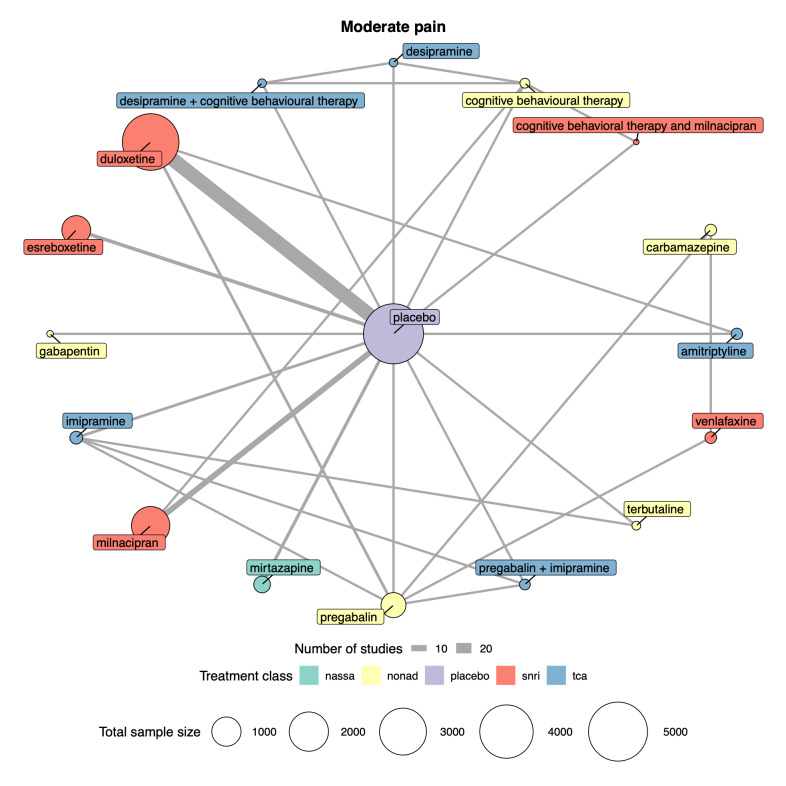

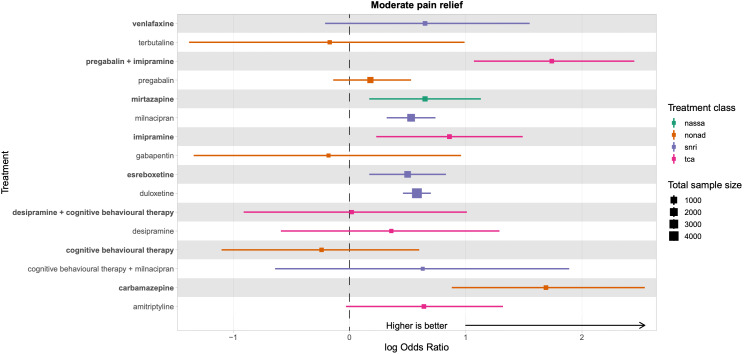

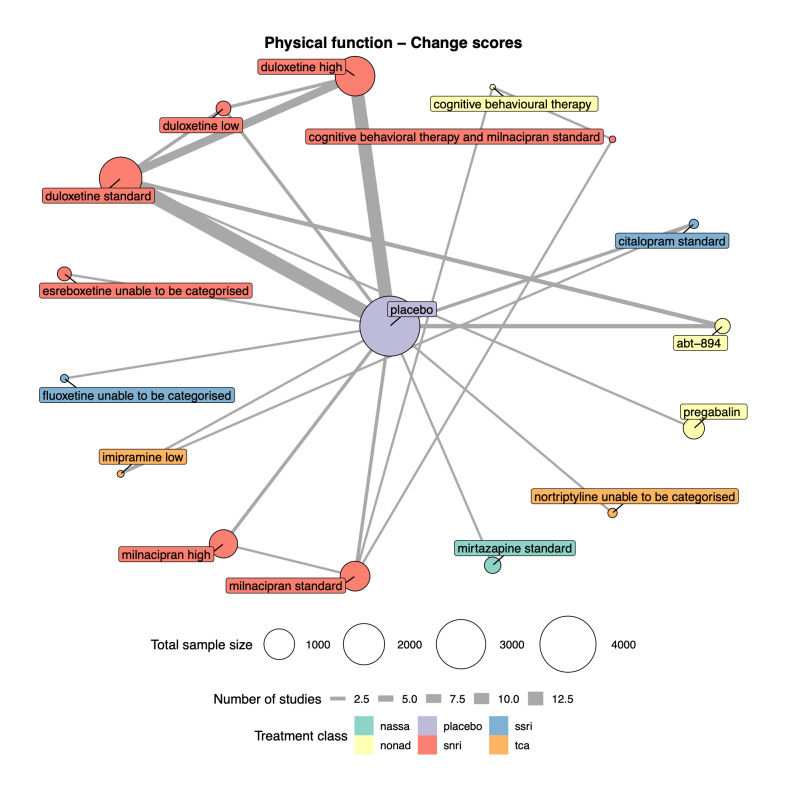

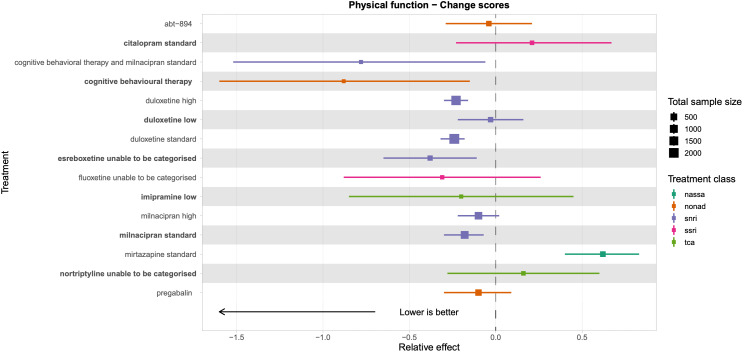

Secondary efficacy outcomes

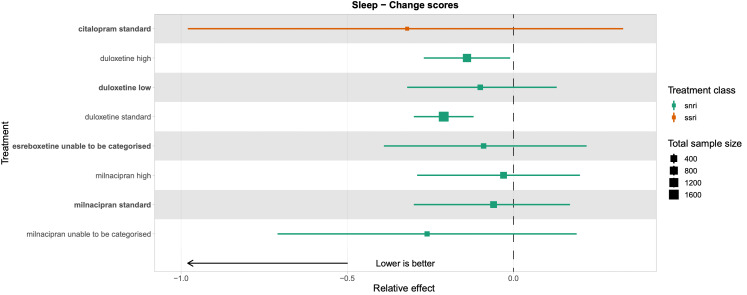

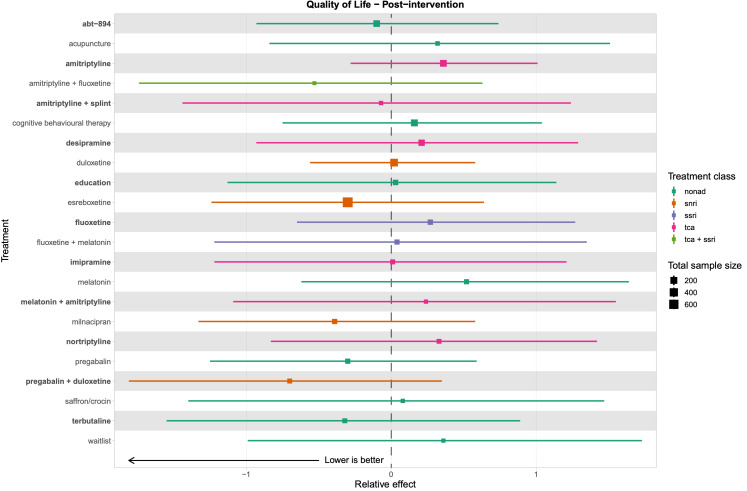

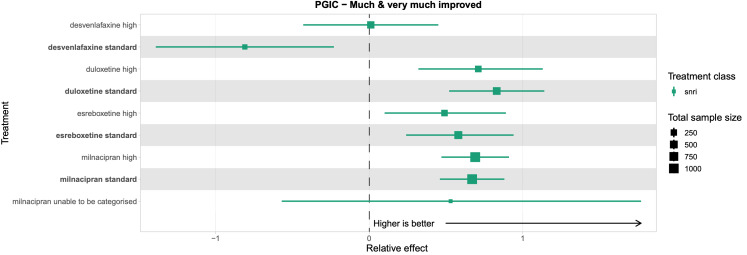

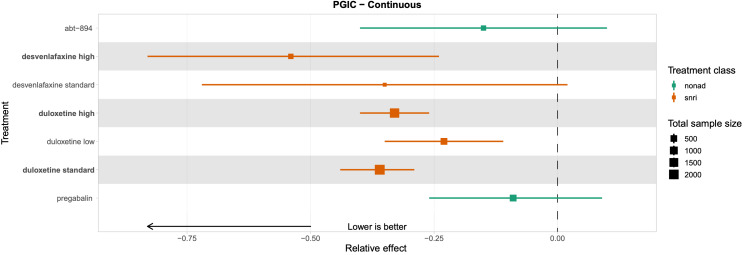

Across all secondary efficacy outcomes (moderate pain relief, physical function, sleep, quality of life, and PGIC), duloxetine and milnacipran were the highest‐ranked antidepressants with moderate‐certainty evidence, although effects were small. For both duloxetine and milnacipran, standard doses were as efficacious as high doses.

Safety

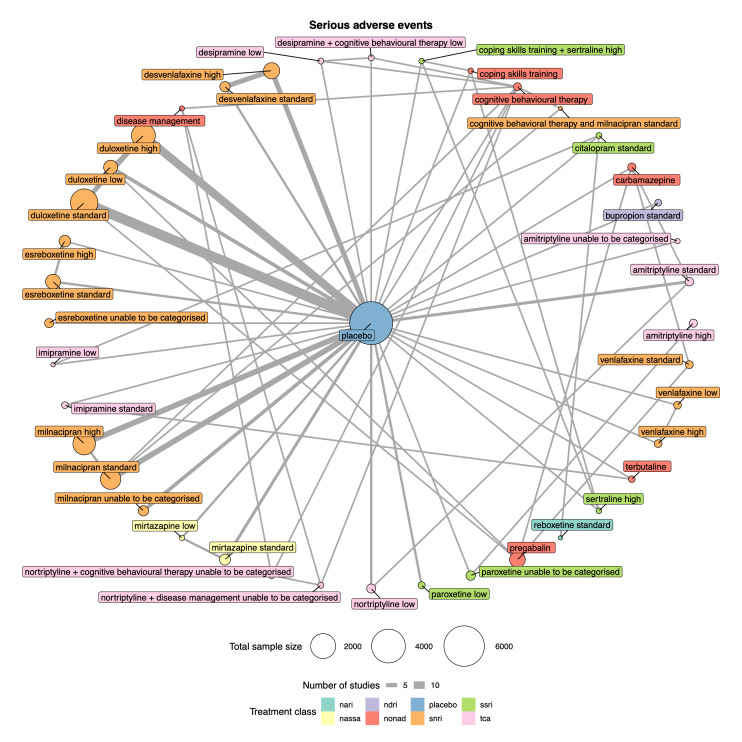

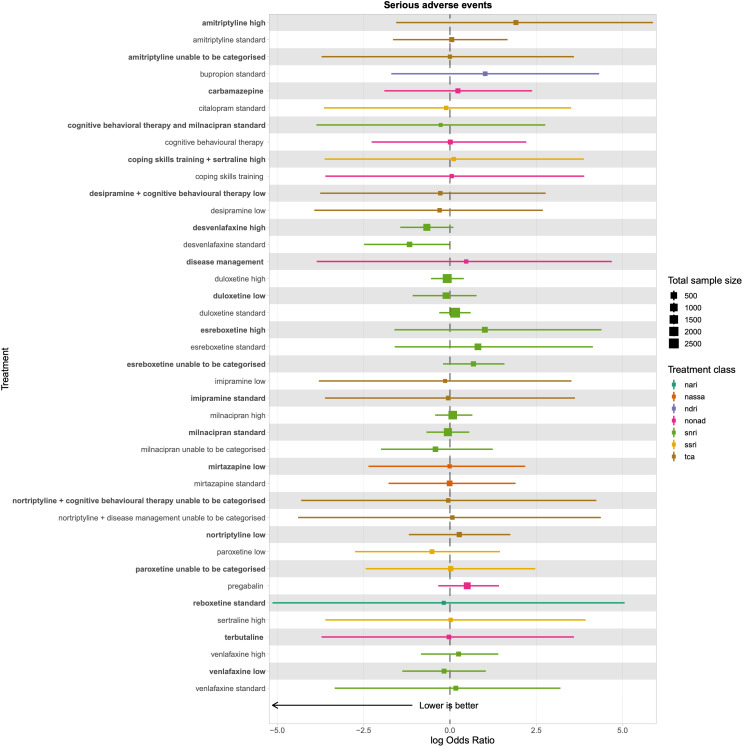

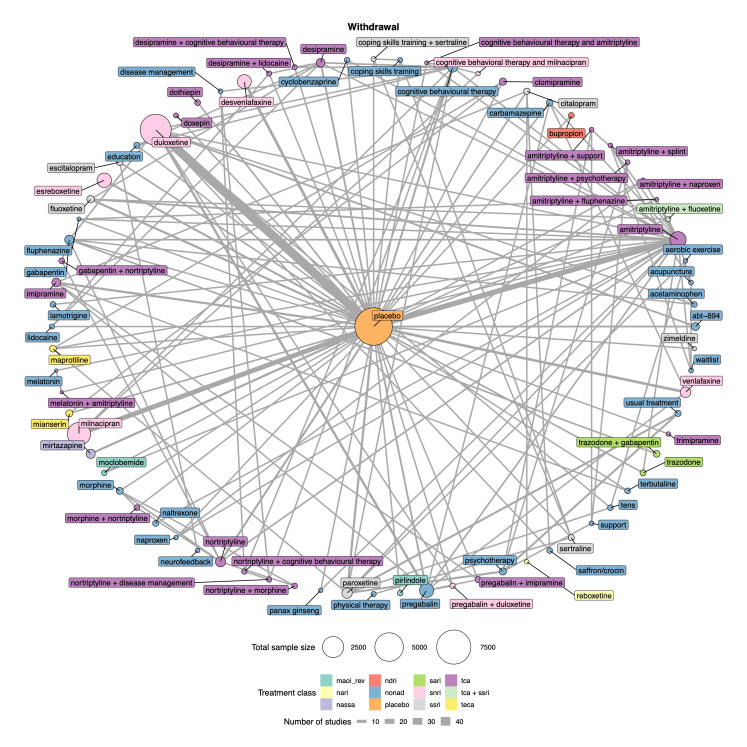

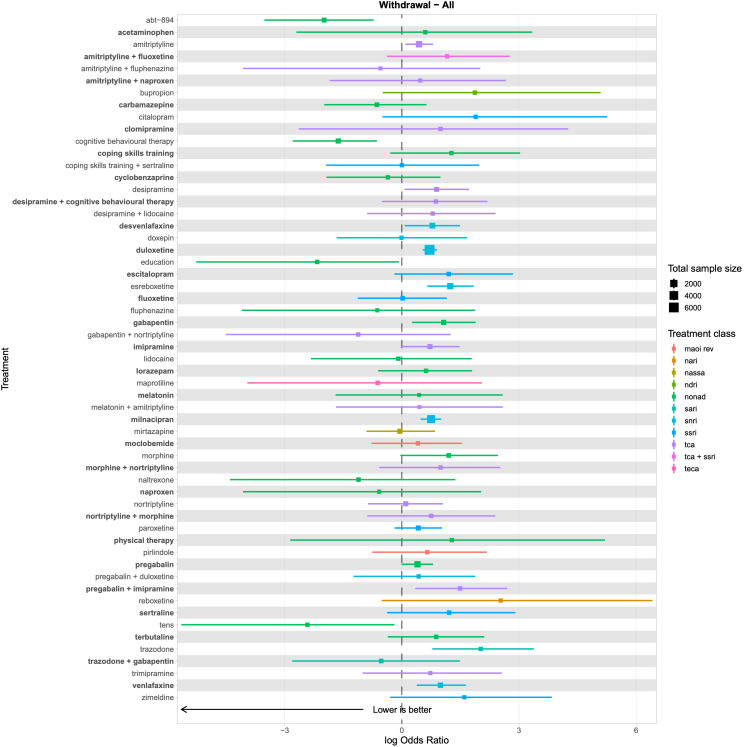

There was very low‐certainty evidence for all safety outcomes (adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal) across all antidepressants. We cannot draw any reliable conclusions from the NMAs for these outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Our review and NMAs show that despite studies investigating 25 different antidepressants, the only antidepressant we are certain about for the treatment of chronic pain is duloxetine. Duloxetine was moderately efficacious across all outcomes at standard dose. There is also promising evidence for milnacipran, although further high‐quality research is needed to be confident in these conclusions. Evidence for all other antidepressants was low certainty. As RCTs excluded people with low mood, we were unable to establish the effects of antidepressants for people with chronic pain and depression. There is currently no reliable evidence for the long‐term efficacy of any antidepressant, and no reliable evidence for the safety of antidepressants for chronic pain at any time point.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Chronic Pain, Chronic Pain/drug therapy, Duloxetine Hydrochloride, Milnacipran, Network Meta-Analysis, Pain Management, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

How effective are antidepressants used to treat chronic pain and do they cause unwanted effects?

Key messages

• We are only confident in the effectiveness of one antidepressant: duloxetine. We found that a standard dose (60 mg) was effective, and that there is no benefit to using a higher dose.

• We are uncertain about unwanted effects for any antidepressant as the data for this were very poor. Future research should address this.

• In clinical practice for chronic pain, a standard dose of duloxetine may be considered before trying other antidepressants.

• Adopting a person‐centred approach is critical. Pain is a very individual experience and certain medications may work for people even while the research evidence is inconclusive or unavailable. Future studies should last longer and focus on unwanted effects of antidepressants.

What is chronic pain?

Chronic pain is pain of any kind that lasts for more than three months. Over one‐third of people across the world experience chronic pain. This often affects people's mood and well‐being, and their ability to work and carry out daily tasks.

How do antidepressants treat chronic pain?

Antidepressants are medications originally developed to treat depression. Different types of antidepressants work in different ways. Antidepressants that work in the same way are grouped into classes. The most common classes are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and serotonin‐noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Research suggests that antidepressants may be effective for pain because the same chemicals that affect mood might also affect pain.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if antidepressants were effective for managing chronic pain and whether they cause unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that compared any antidepressant with any other treatment for any type of chronic pain (except headache). We compared all the treatments against each other using a statistical method called network meta‐analysis. This method allows us to rank the effectiveness of the different antidepressants from best to worst.

What did we find?

We found 176 studies including 28,664 people with chronic pain. These studies investigated 89 different types or combinations of treatment. Studies mainly investigated the effect of antidepressants on three different types of pain: fibromyalgia (59 studies), nerve pain (49 studies), and musculoskeletal pain (e.g. osteoarthritis or low back pain; 40 studies). The most common antidepressant classes investigated were SNRIs (74 studies), TCAs (72 studies), and SSRIs (34 studies). The most common antidepressants investigated were: amitriptyline (a TCA; 43 studies); duloxetine (an SNRI; 43 studies), and milnacipran (an SNRI; 18 studies). Of the 146 studies that reported where their funding came from, pharmaceutical companies funded 72 studies. The average study lasted 10 weeks.

Most of the studies compared an antidepressant with a placebo (which looks like the real medicine but doesn’t have any medicine in it), but some studies compared an antidepressant against a different type of medicine, a different antidepressant, a different type of treatment (like physiotherapy), or different doses of the same antidepressant.

Most of the studies in this review reported information on pain relief and unwanted effects. Fewer studies reported on quality of life, sleep, and physical function.

Main results

• Duloxetine probably has a moderate effect on reducing pain and improving physical function. It was the antidepressant that we have the most confidence in. Higher doses of duloxetine probably provided no extra benefits than standard doses. For every 1000 people taking standard‐dose duloxetine, 435 will experience 50% pain relief compared with 287 who will experience 50% pain relief taking placebo.

• Milnacipran may reduce pain, but we are not as confident in this result as duloxetine because there were fewer studies with fewer people involved.

• Most studies excluded people with mental health conditions, meaning that participants were already in the 'normal' ranges for anxiety and depression at the beginning of studies. This limited our analysis for mood. Mirtazapine and duloxetine may improve mood, but we are very uncertain about the results.

• We do not know about unwanted effects of using antidepressants for chronic pain; there are not enough data to be certain about the results.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

There are still a number of questions that we were unable to answer:

• Aside from duloxetine and milnacipran, we do not have confidence in the results from any other antidepressant included in this review because there are not enough studies.

• We do not know whether antidepressants are effective at treating pain in the long term. The average length of studies was 10 weeks.

• There was no reliable evidence on the safety of taking antidepressants for chronic pain, both short‐ and long‐term.

• We do not know how effective antidepressants are for people with both chronic pain and depression as the most studies excluded participants with depression and anxiety.

How up to date is this evidence?

This review is up to date to January 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Substantial pain relief summary of findings.

| Estimates of effects, credible intervals, and certainty of the evidence for substantial pain relief in people with chronic pain | |||||||

| Bayesian network meta‐analysis summary of findings table | |||||||

|

Patient or population: people with chronic pain Interventions: desvenlafaxine high dose (≥ 50 mg); duloxetine low dose (< 60 mg), standard dose (60 mg), and high dose (> 60 mg); esreboxetine standard dose (4‐8 mg) and high dose (≥ 8 mg); milnacipran standard dose (100 mg) and high dose (> 100 mg); mirtazapine standard dose (30 mg) Comparator (reference): placebo Outcome: substantial pain relief (≥ 50% reduction in pain intensity from baseline) as measured on various scales including 0‐10 VAS, 0‐100 VAS, and the Brief Pain Inventory Direction: higher is better (i.e. more people reporting substantial pain relief) | |||||||

|

Total studies: 42 Total participants: 14,626 |

Relative effect (OR and 95% CI) |

Anticipated absolute effect (event rate)* | Certainty of the evidence (CINeMA) |

Ranking** (2.5% to 97.5% credible interval) |

Interpretation of findings | ||

| With placebo | With intervention | Difference | |||||

|

Duloxetine standard dose RCTs: 16 Participants: 4490 |

1.91 (1.69 to 2.17) |

592/2061 287 per 1000 |

1058/2429 435 per 1000 |

148 more per 1000 | Moderatea | 8 (5 to 12) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 7.1 |

|

Duloxetine high dose RCTs: 14 Participants: 3692 |

1.91 (1.66 to 2.21) |

431/1855 232 per 1000 |

674/1837 366 per 1000 |

134 more per 1000 | Moderatea | 8 (5 to 12) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 7.4 |

|

Milnacipran high dose RCTs: 1 Participants: 384 |

1.64 (1.04 to 2.58) |

38/145 262 per 1000 |

88/239 368 per 1000 |

106 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 11 (4 to 19) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 9.4 |

|

Esreboxetine standard dose RCTs: 1 Participants: 828 |

1.72 (1.13 to 2.62) |

33/275 120 per 1000 |

105/553 190 per 1000 |

70 more per 1000 | Lowa | 11 (4 to 19) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 14 |

|

Milnacipran standard dose RCTs: 2 Participants: 1298 |

1.65 (1.28 to 2.13) |

130/654 199 per 1000 |

187/644 290 per 1000 |

91 more per 1000 | Lowa,c | 12 (6 to 18) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 11 |

|

Mirtazapine standard dose RCTs: 1 Participants: 422 |

1.30 (0.79 to 2.15) |

33/211 156 per 1000 |

41/211 194 per 1000 |

39 more per 1000 | Lowe | 15 (6 to 21) |

Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Duloxetine low dose RCTs: 6 Participants: 1116 |

1.71 (1.36 to 2.20) |

150/523 287 per 1000 |

242/593 407 per 1000 |

120 more per 1000 | Moderatea,b,c | 16 (11 to 20) |

Equivalent to NNTB of 8.3 |

|

Esreboxetine high dose RCTs: 1 Participants: 555 |

1.29 (0.79 to 2.11) |

33/275 120 per 1000 |

42/280 150 per 1000 |

30 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 16 (7 to 22) |

Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Desvenlafaxine high dose RCTs: 2 Participants: 870 |

1.19 (0.83 to 1.70) |

51/215 237 per 1000 |

177/655 270 per 1000 |

33 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 17 (11 to 21) |

Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Network meta‐analysis‐summary of findings table definitions *Anticipated absolute effect. Anticipated absolute effect compares 2 risks by calculating the difference between the risk of the intervention group with the risk of the control group. ** Mean rank and credible intervals are presented. CI: confidence interval; CINeMA: Confidence in Network Meta‐Analysis; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; VAS: visual analogue scale The number of participants for each antidepressant reflects the total number of participants taking the antidepressant or placebo from the studies in the network meta‐analysis. | |||||||

|

CINeMA grades of confidence in the evidence High: further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

aDowngraded due to within‐study bias. bDowngraded due to imprecision in the estimate. cDowngraded due to heterogeneity in the estimate. dDowngraded due to incoherence in the network. eDowngraded due to a small number of trials and participants; we cannot draw reliable conclusions.

Summary of findings 2. Pain intensity summary of findings.

| Estimates of effects, credible intervals, and certainty of the evidence for pain intensity in people with chronic pain | |||||||

| Bayesian network meta‐analysis summary of findings table | |||||||

|

Patient or population: people with chronic pain Interventions: duloxetine low dose (< 60 mg), standard dose (60 mg), and high dose (> 60 mg); milnacipran standard dose (100 mg) and high dose (> 100 mg) Comparator (reference): placebo Outcome: change in pain intensity, as measured on multiple scales including 0‐10 VAS, 0‐100 VAS, Brief Pain Inventory, and the Short‐form McGill Pain Questionnaire Direction: lower is better (i.e. a greater reduction in pain intensity) | |||||||

|

Total studies: 50 Total participants: 14,926 |

Relative effect | Anticipated absolute effect (event rate) | Certainty of the evidence (CINeMA) |

Ranking* (2.5% to 97.5% credible interval) |

Interpretation of findings** | ||

| With placebo | With intervention | Difference | |||||

|

Duloxetine high dose RCTs: 14 Participants: 3683 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.37 (−0.45 to −0.28) |

Lowa,b | 9 (8 to 13) |

Small to moderate effect |

|

Duloxetine standard dose RCTs: 18 Participants: 4959 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.31 (−0.39 to −0.24) |

Moderateb | 11 (10 to 15) |

Small to moderate effect |

|

Milnacipran high dose RCTs: 2 Participants: 1670 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.22 (−0.40 to −0.05) |

Lowa,c | 14 (12 to 19) |

Small effect |

|

Milnacipran standard dose RCTs: 4 Participants: 1866 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.22 (−0.39 to −0.06) |

Moderatea,b | 14 (12 to 20) |

Small effect |

|

Duloxetine low dose RCTs: 6 Participants: 1104 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.11 (−0.25 to 0.03) |

Moderatea,c | 17 (12 to 21) |

Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Network meta‐analysis‐summary of findings table definitions *Mean rank and credible intervals are presented. **SMD interpretation based on clinical judgement and in line with Cohen 1988 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2022) as small (0.2), moderate (0.5) and large (0.8). CI: confidence interval; CINeMA: Confidence in Network Meta‐Analysis; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SMD: standardised mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale The number of participants for each antidepressant reflects the total number of participants taking the antidepressant or placebo from the studies in the network meta‐analysis. | |||||||

|

CINeMA grades of confidence in the evidence High: further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

aDowngraded due to within‐study bias. bDowngraded due to imprecision in the estimate. cDowngraded due to heterogeneity in the estimate. dDowngraded due to incoherence in the network. eDowngraded due to a small number of trials and participants; we cannot draw reliable conclusions.

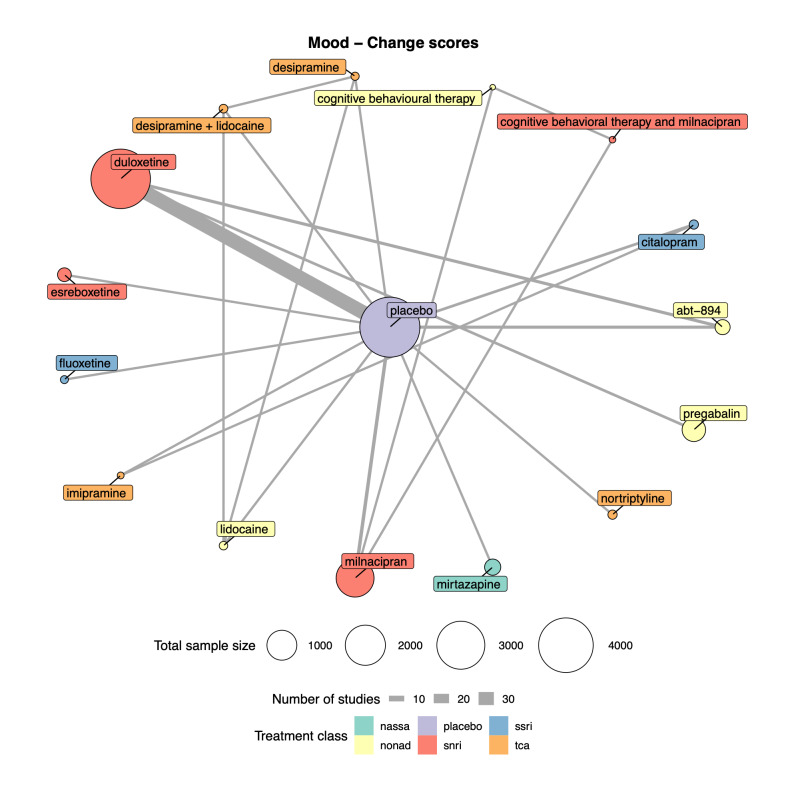

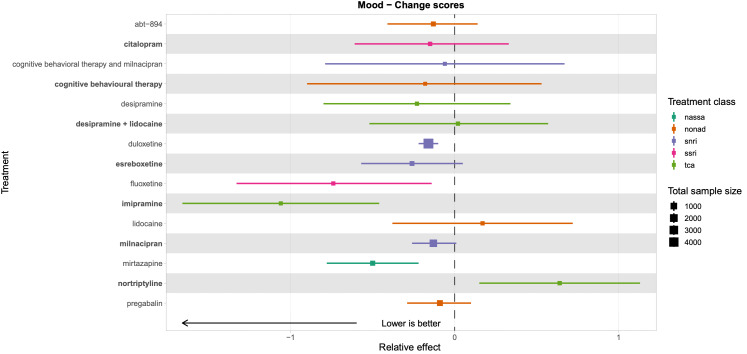

Summary of findings 3. Mood summary of findings.

| Estimates of effects, credible intervals, and certainty of the evidence of antidepressants on mood in people with chronic pain | |||||||

| Bayesian network meta‐analysis summary of findings table | |||||||

|

Patient or population: people with chronic pain Interventions: duloxetine (all doses combined), milnacipran (all doses combined), mirtazapine (all doses combined) Comparator (reference): placebo Outcome: change in mood (depression, anxiety, distress) scores as measured on various scales including the Beck Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, SF‐36 Mental Component Score, and the SF‐36 Mental Health Subscale Direction: lower is better (i.e. a greater reduction of distress, depression, or anxiety) | |||||||

|

Total studies: 38 Total participants: 12,985 |

Relative effect | Anticipated absolute effect (event rate) | Certainty of the evidence (CINeMA) |

Ranking* (2.5% to 97.5% credible interval) |

Interpretation of findings** | ||

| With placebo | With intervention | Difference | |||||

|

Mirtazapine RCTs: 1 Participants: 406 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.5 (−0.78 to −0.22) |

Lowe | 4 (2 to 7) | Moderate effect |

|

Duloxetine RCTs: 26 Participants: 7952 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.16 (−0.22 to −0.1) |

Moderatea | 8 (5 to 11) | Small effect |

|

Milnacipran RCTs: 5 Participants: 3109 |

‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

SMD −0.13 (−0.26 to 0.01) |

Moderatea,c | 9 (5 to 13) | Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Network meta‐analysis‐summary of findings table definitions *Mean rank and credible intervals are presented. **SMD interpretation based on clinical judgement and in line with Cohen 1988 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2022) as small (0.2), moderate (0.5) and large (0.8). CI: confidence interval; CINeMA: Confidence in Network Meta‐Analysis; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SMD: standardised mean difference The number of participants for each antidepressant reflects the total number of participants taking the antidepressant or placebo from the studies in the network meta‐analysis. | |||||||

|

CINeMA grades of confidence in the evidence High: further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

aDowngraded due to within‐study bias. bDowngraded due to imprecision in the estimate. cDowngraded due to heterogeneity in the estimate. dDowngraded due to incoherence in the network. eDowngraded due to a small number of trials and participants; we cannot draw reliable conclusions.

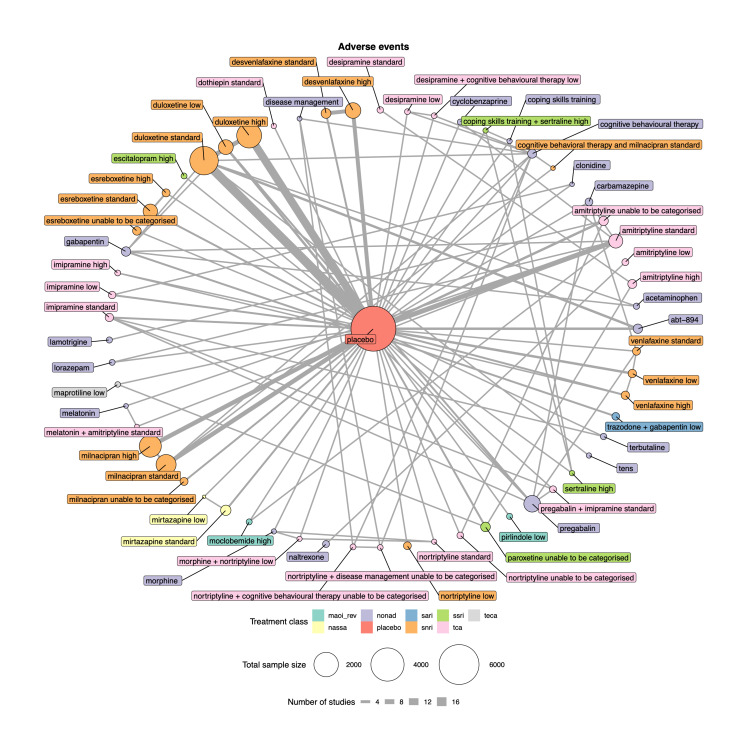

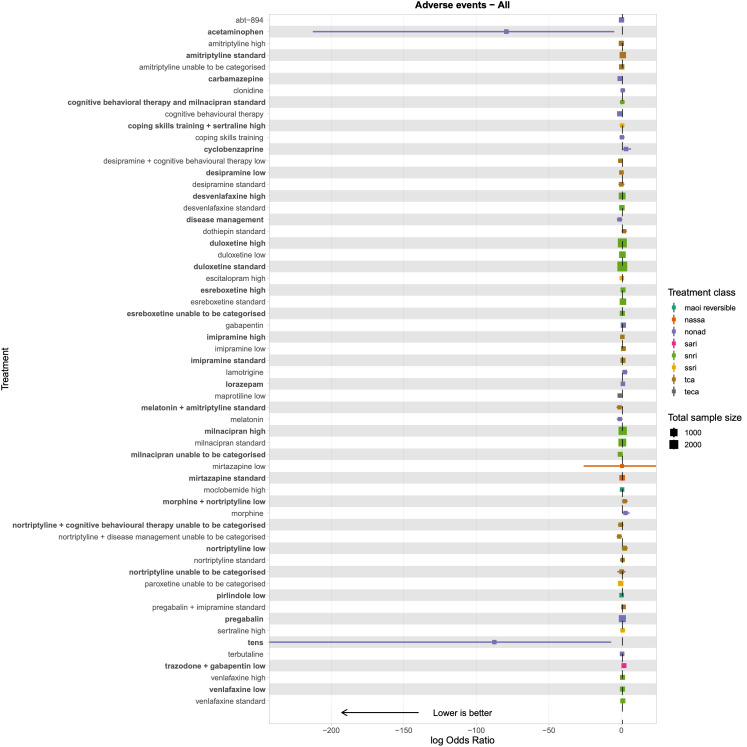

Summary of findings 4. Adverse events summary of findings.

| Estimates of effects, credible intervals, and certainty of the evidence for adverse events with antidepressants in people with chronic pain | |||||||

| Bayesian network meta‐analysis summary of findings table | |||||||

|

Patient or population: people with chronic pain Interventions: amitriptyline standard dose (25‐75 mg); desvenlafaxine high dose (> 50 mg); duloxetine low dose (< 60 mg), standard dose (60 mg), and high dose (> 60 mg); milnacipran standard dose (100 mg) and high dose (> 100 mg); mirtazapine standard dose (30 mg) Comparator (reference): placebo Outcome: adverse events (as reported per study) Direction: lower is better (i.e. fewer people reporting adverse events) | |||||||

|

Total studies: 93 Total participants: 22,558 |

Relative effect (OR and 95% CI) |

Anticipated absolute effect (event rate)* | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Ranking** (2.5% to 97.5% credible interval) |

Interpretation of findings | ||

| With placebo | With intervention | Difference | |||||

|

Desvenlafaxine high dose RCTs: 2 Participants: 905 |

1.67 (0.92 to 2.41) |

174/220 791 per 1000 |

590/685 863 per 1000 |

72 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b,c | 30 (16 to 48) | Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Mirtazapine standard dose RCTs: 2 Participants: 457 |

1.70 (0.48 to 2.91) |

135/228 592 per 1000 |

162/229 712 per 1000 |

120 more per 1000 | Very lowb,c | 31 (11 to 52) | Not significantly different from placebo |

|

Duloxetine standard dose RCTs: 20 Participants: 4998 |

1.88 (1.58 to 2.17) |

1259/2164 582 per 1000 |

1883/2834 723 per 1000 |

142 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 33 (24 to 42) | Equivalent NNTH is 7.0 |

|

Milnacipran standard dose RCTs: 8 Participants: 2491 |

1.92 (1.37 to 2.46) |

930/1235 753 per 1000 |

1039/1256 854 per 1000 |

101 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b,c | 33 (20 to 45) | Equivalent NNTH is 10 |

|

Duloxetine high dose RCTs: 10 Participants: 4000 |

1.93 (1.64 to 2.23) |

1199/1912 627 per 1000 |

1587/2088 764 per 1000 |

137 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 34 (24 to 43) | Equivalent NNTH is 7.03 |

|

Duloxetine low dose RCTs: 6 Participants: 1031 |

2.03 (1.45 to 2.62) |

271/437 620 per 1000 |

325/594 768 per 1000 |

148 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 35 (21 to 47) | Equivalent NNTH is 7.0 |

|

Milnacipran high dose RCTs: 7 Participants: 2837 |

2.44 (1.89 to 2.98) |

930/1264 736 per 1000 |

1294/1573 872 per 1000 |

136 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b | 39 (25 to 50) | Equivalent NNTH is 6.8 |

|

Amitriptyline standard dose RCTs: 10 Participants: 997 |

2.66 (2.14 to 3.19) |

250/479 522 per 1000 |

351/518 744 per 1000 |

222 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b,e | 41 (28 to 51) | Equivalent NNTH is 4.5 |

|

Esreboxetine standard dose RCTs: 1 Participants: 783 |

2.92 (1.90 to 3.93) |

85/227 374 per 1000 |

315/556 636 per 1000 |

262 more per 1000 | Very lowa,b,c,e | 42 (21 to 56) | Equivalent NNTH is 3.8 |

|

Network meta‐analysis‐summary of findings table definitions * Anticipated absolute effect. Anticipated absolute effect compares two risks by calculating the difference between the risk of the intervention group with the risk of the control group. ** Mean ranks and credible intervals are presented. CI: confidence interval; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial The number of participants for each antidepressant reflects the total number of participants taking the antidepressant or placebo from the studies in the network meta‐analysis. | |||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded due to within‐study bias. bDowngraded due to imprecision in the estimate. cDowngraded due to heterogeneity in the estimate. dDowngraded due to incoherence in the network. eDowngraded due to a small number of trials and participants; we cannot draw reliable conclusions.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic pain is common in adults internationally, and is defined as pain lasting or recurring for three months or longer (IASP 2019). Chronic pain can be a primary condition or can occur in the context of a disease (Treede 2019).

Chronic pain and its impact on an individual is generally assessed via self‐report. It is estimated that about one in five adults worldwide experience pain that is moderate or severe in its intensity and lasts three months or more (Moore 2014), however estimates vary and may be higher. For example, reviews of chronic pain in the UK suggest that between a third and a half of the population experience chronic pain (Fayaz 2016); and a review of chronic low back pain in Africa reported the annual prevalence as 57% (Morris 2018). Some populations are more likely to experience chronic pain: older adults, women, people not in employment due to ill health and disability, and people with comorbidities (Mills 2019). Social circumstances are particularly influential; people in low socio‐economic circumstances are not only more likely to experience chronic pain, but also report higher levels of severity and disability (Mills 2019).

The impact of chronic pain is similar across conditions, despite the different aetiologies. Globally, chronic pain accounts for the highest number of years lived with disability, and affects individuals’ daily lives, society and healthcare services (Breivik 2006; Rice 2016). Chronic pain accounts for up to one in five general practice consultations each year in Europe, Africa and Asia (European Pain Federation 2016; Jordan 2010; Morris 2018). Chronic pain is also one of the global leading causes for sickness absence and people being unable to work (Bevan 2012; Office for National Statistics 2019).

On an individual level, chronic pain can severely impair a person's quality of life, including physical functioning, mood, sleep, and ability to work outside the home (Breivik 2006). It has also been long‐established that chronic pain influences a person's mood; depression is estimated to be three to four times more prevalent in people with chronic pain than those without (Gureje 1998; Sullivan 1992; Tunks 2008). Depression is characterised by persistent feelings of sadness or low mood, loss of pleasure in activities, fatigue, loss of motivation, changes in appetite and having thoughts of suicide or self‐harm (American Psychiatric Association 2013). People have reported that experiencing only a few depressive symptoms can be both distressing and disabling; therefore, it is important to address these as effectively as possible (NICE 2009a). Depression and chronic pain are complex to address in both research and clinical practice, as many of the symptoms of chronic pain can overlap with those of depression (for example, fatigue and loss of motivation or pleasure in activities). Furthermore, the content of depressive thoughts and the antecedents of feelings of sadness experienced by people in chronic pain may differ to those experienced in people with depression but without pain. It is important to identify differences in pain‐related distress (i.e. individuals with chronic pain experiencing low mood because of their pain) and clinical depression, which may reflect on the prevalence statistics reported above.

Successful treatment of chronic pain can result in significant improvements in quality of life, including anxiety and depression (Goesling 2013; Moore 2010a; Moore 2014). A systematic review identified that for people with fibromyalgia, reductions in pain intensity of 50% or more is associated with self‐reports of sleep, fatigue and depression reverting to normative values (Moore 2014). Therefore, efficacious treatment of the pain condition is essential for improvement of both pain and mood, in addition to potential improvements in sleep, physical function and quality of life. There are many different treatments aimed at reducing and managing chronic pain, including analgesic medication, physiotherapy, self‐management guidance, exercise, psychological therapy, antidepressants, pain management clinics and surgery. The use of these depends upon the pain condition, severity of pain, individual characteristics, availability of services and national policy and guidelines.

Description of the intervention

Antidepressants are medicines developed and used primarily for the treatment of clinical depression. A network meta‐analysis (NMA) of the 21 most common antidepressants has shown that they are efficacious in the treatment of acute major depression, particularly severe depression (Cipriani 2018).

Antidepressants are grouped into different classes based on their chemical structure and presumed mechanism of action. The most common classes are:

tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, nortriptyline, and others;

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): citalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine, and others;

serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): duloxetine, levomilnacipran, milnacipran, venlafaxine, and others;

-

monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs):

irreversible: phenelzine, tranylcipromine, izocarboxazid, and others;

reversible: brofaramine, moclobemide, tyrima, and others.

Antidepressants are recommended for first‐line treatment of depression, but can also be used 'off‐label' in clinical practice to treat other conditions, including chronic pain (British National Formulary 2022a). Prescriptions of antidepressants are relatively common in patients with chronic pain internationally; for example, 12.3% of people with chronic low back pain in Portugal report taking antidepressants for pain relief (Gouveia 2017; Kurita 2012). Recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of duloxetine, amitriptyline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram and sertraline in the management of chronic primary pain (NICE 2020). Amitriptyline and duloxetine are also recommended as first‐line treatments for neuropathic pain in primary care (NICE 2019). Both of these guidelines recommend these antidepressants regardless of a person's mood. However, other guidelines contradict this, for example antidepressants can be prescribed for people with a chronic physical health condition only if they are also experiencing moderate to severe depression (NICE 2009b), but they are not recommended at all for the treatment of chronic low back pain (without sciatica; NICE 2017). The NICE guidelines for chronic primary pain recommend antidepressants as the only pharmacological intervention to manage chronic primary pain (NICE 2021).

These guidelines only reviewed the evidence from head‐to‐head trials, and subsequently recommend six antidepressants with no hierarchy: amitriptyline, citalopram, duloxetine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, or sertraline. Therefore, guidance for clinicians is mixed and unclear. Furthermore, as antidepressants can be prescribed for treating mood or pain, the proportions of antidepressants prescribed to people with chronic pain for the primary aim to reduce pain or improve mood is unknown.

There are also risks in the prescription of antidepressants. Adverse events such as dizziness, headache, nausea, ejaculation disorder, weight loss, tremor, sweating and insomnia, have been found by randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to be more common in people taking antidepressants compared with those taking placebo (Riediger 2017; Sinyor 2020). Use of antidepressants is associated with an increased risk of falls, fractures, all‐cause mortality, and stroke in older adults (aged 65 and over), and self‐harm and suicide in both younger adults (aged 20 to 64) and older adults (Coupland 2011; Coupland 2015). Antidepressants also increase the risk of onset of seizures (Hill 2015); and the potential for gastrointestinal bleeding with SSRIs is widely recognised (Jiang 2015). Therefore, long‐term use of antidepressants for people with chronic pain is expected to be associated with potential for harms at the population level.

How the intervention might work

Antidepressants were originally developed to treat depression. Most antidepressants work by targeting monoamine neurotransmitters associated with mood and emotion and their receptors in the nervous system. These receptors, such as 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptors, are activated by many neurotransmitters including serotonin, dopamine, adrenaline and noradrenaline (Harmer 2017). Antidepressants prevent the neurotransmitters from being absorbed into neurons, which prolongs their activity in synapses. The process by which this relieves depression is not fully understood, but research currently focuses on theories of neurochemical changes and neuroplasticity (Harmer 2017). Additionally, depending upon the class, the effect of antidepressants may be delayed, with reported clinical improvement often taking weeks to occur (Harmer 2017; Tylee 2007).

Antidepressants are also often used to manage chronic pain. Antidepressants are reported to offer an analgesic response in people with pain without depression, particularly for neuropathic pain, but also for some people with fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, and back pain. It is theorised that the body's pain response systems travelling to and from the brainstem involve the noradrenergic neurotransmitters (Taylor 2017). Therefore, by increasing the amount of serotonin and noradrenaline in the nervous system, this may subsequently block pain signals at the peripheral, spinal, and supraspinal levels, reducing perceived pain; particularly in neuropathic pain (Finnerup 2021; Kremer 2018).

Additionally, a part of the brain called the locus coeruleus may have an analgesic effect on pain in the body (Llorca‐Torralba 2016). Signals from this part of the brain are sent when the body reacts to a stimulus, such as pain, and noradrenaline is released into the dorsal horn in the spine to block receptors. Animal studies have shown that when pain signals are continuously received, as is the case in chronic pain, this analgesic response lessens over time, and noradrenaline is then not released (Llorca‐Torralba 2016; Obata 2017). However, when antidepressants are given, the analgesic response from the locus coeruleus is restored (Alba‐Delgado 2012; Llorca‐Torralba 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

To date, there have been no NMAs investigating all antidepressants for all chronic pain conditions. There is no evidence comparing classes of antidepressants to each other in the management of chronic pain, as identified by the recent NICE guidelines (NICE 2020). Therefore, in the absence of any one RCT comparing the efficacy and safety of all antidepressants for chronic pain, a NMA is required to assess their relative effectiveness.

Previous Cochrane Reviews have investigated the efficacy of individual antidepressants in improving individual chronic pain conditions, and where possible by dose. There is no high‐quality evidence to support or refute the use of amitriptyline, milnacipran, nortriptyline, venlafaxine, desipramine or imipramine for management of neuropathic pain (Derry 2015a; Derry 2015b; Gallagher 2015; Hearn 2014a; Hearn 2014b; Moore 2015), principally because of limited numbers of small studies with some high risks of bias. This is despite amitriptyline being recommended as a first‐line treatment for neuropathic pain in primary care in guidelines for the UK, Canada and the International Association for the Study of Pain (Bates 2019; Finnerup 2015; Moulin 2014; NICE 2019). However, there is moderate‐quality evidence that duloxetine is efficacious for diabetic peripheral neuropathy at doses of 60 mg and 120 mg (Lunn 2014).

For fibromyalgia, Cochrane Reviews of antidepressants show that there is no unbiased evidence that amitriptyline, desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine or SSRIs are superior to placebo (Walitt 2015; Welsch 2018). There is low‐quality evidence that duloxetine and milnacipran have some benefit in improving patients’ global impression of change (PGIC) and providing an improvement in pain relief of 30% or more, but no clinical benefit over placebo for improvement in pain relief of 50% or more, health‐related quality of life or fatigue (Welsch 2018). Similarly, for mirtazapine, there is evidence for improvement in pain relief of 30% or more, and reduction of mean pain intensity and sleep problems, but this evidence is of low to medium quality, and there is no benefit for improvement in pain relief of 50% or more, PGIC, 20% improvement of health‐related quality of life, reduction of fatigue or reduction in negative mood (Welsch 2015).

Only one Cochrane Review has investigated the use of antidepressants for low back pain, and it found no clear evidence to support the use of any antidepressants (Urquhart 2008). A more recent systematic review supports these conclusions (Koes 2018). However, when analysed using the baseline observation carried forward imputation method for missing data, pooled individual patient data analyses of RCTs have shown duloxetine and etoricoxib to be effective in reducing pain for pain conditions including chronic low back pain (Moore 2010b; Moore 2014). These distributions were bimodal; participants generally responded very well or very poorly, with few in between (Moore 2014).

These previous reviews have shown that there is no evidence comparing the data across all antidepressants and pain conditions. Through our review and network meta‐analysis, we intend to compare all these antidepressants across pain conditions, and identify whether certain classes or doses of antidepressants are useful in the management of pain and mood for people with chronic pain, and for certain chronic pain conditions. As antidepressants are also associated with a number of side effects, we will compare the proportion of adverse events occurring with the use of different antidepressants (including different classes of antidepressants, different types of antidepressants, and different dose regimes) within populations living with chronic pain.

There is evidence that people with chronic pain may be experiencing pain‐related distress rather than clinical depression, although both conditions can present with similar symptoms (Rusu 2016). The distinction between pain‐related distress and depression is particularly important as primary care practitioners are often given contradictory guidance: they are encouraged to better detect depression (Mitchell 2009; Nuyen 2005), whilst avoiding over‐medicalisation of distress and thus over‐treatment (Dowrick 2013; Mulder 2008). This is important as antidepressants can be prescribed for both the management of pain and mood (e.g. clinical depression) in people with chronic pain. This review aimed to clarify this guidance as, unlike previous reviews in this area, we intended to investigate whether there were differences dependent upon whether the antidepressants were prescribed to primarily treat mood or pain.

Objectives

To assess the comparative efficacy and safety of antidepressants for adults with chronic pain (except headache) by:

assessing the efficacy of antidepressants by type, class and dose in improving pain, mood, physical function, sleep, quality of life and PGIC;

assessing the number of adverse events and serious adverse events for antidepressants by type, class and dose;

ranking antidepressants for efficacy of treating pain, mood and adverse events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs that compared any antidepressant with any comparator. RCTs are the best design to minimise bias when evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. We followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions for the inclusion of cross‐over RCTs, which requires inclusion of this type of study unless there is a justifiable reason not to (McKenzie 2020). The risk in this review was that washout periods between the periods of the study would not be long enough for carry‐over effects from the antidepressants or comparators to be sufficiently minimised. Therefore, we only included cross‐over trials with washout periods of at least five times the length of the antidepressant half‐life (this was calculated individually for each antidepressant).

The most common comparators we anticipated finding in the literature were: the same antidepressant at a different dose; a different antidepressant; placebo (both active and inert); other medications for pain management purposes (e.g. pregabalin, gabapentin); analgesics; psychological therapy (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy); exercise; physiotherapy; multidisciplinary pain programmes; herbal medicines and nutraceuticals (e.g. St John’s Wort); and acupuncture. Where the comparator was a placebo, antidepressant, analgesic or other medication for pain management purposes, these studies were required to be double‐blind. We included studies that examined any dose of antidepressants, with a study duration of at least two weeks and minimum of 10 participants per arm. We excluded non‐randomised studies, case reports, experimental studies, clinical observations and prevention studies.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years or older) reporting primary or secondary pain in any part of their body (except headache) as their primary complaint, that matched the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition of chronic pain (i.e. at least three months' duration; IASP 2019). We included all studies regardless of the severity of participants' chronic pain, although we extracted whether severity was part of the inclusion criteria of the individual studies. We excluded studies where the participants' primary complaint was headache or migraine, as this had been covered in previous Cochrane Reviews (Williams 2020). Although this condition does fit within the IASP criteria, the diagnosis, classification and treatment of primary and secondary headache are often different from that of other pain conditions; and clinical trials are primarily aimed at prevention of further headaches or migraines rather than symptomatic treatment. We included participants with multiple health conditions as long as the chronic pain condition was the focus of the trial.

Types of interventions

Decision set

We included any antidepressant at any dose, for any indication, but used primarily for treatment of people with chronic pain and compared to placebo or active intervention. We included antidepressants grouped into the following classes.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine, trimipramine, doxepin, desipramine, protriptyline, nortriptyline, dothiepin, lofepramine, and others

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, zimelidine and others

Serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): venlafaxine, milnacipran, duloxetine, and others

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs):

irreversible: phenelzine, tranylcipromine, izocarboxazid, and others;

reversible: brofaramine, moclobemide, tyrima, and others

-

Other antidepressants

Noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NARIs): reboxetine, atomoxetine, and others

Noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): amineptine, bupropion, and others

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs) including tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCA) such as: mirtazapine, mianserin, maprotiline, and others

Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs): trazodone, and others

Unclassified: agomelatine, vilazodone, and others

We categorised doses of included antidepressants into low, standard, and high doses. These are displayed in Table 5. As the majority of antidepressants are not licensed for pain, we based our judgements on the recommendations of daily doses for clinical depression in the British National Formulary (British National Formulary 2022a). The judgements were made by clinical authors of the review; initially by the clinical pharmacist and then approved by discussion with a psychiatrist and anaesthetist.

1. Antidepressant dose categorisation.

| Antidepressant | Total daily dosage | ||

| Low | Standard | High | |

| Amitriptyline | < 25 mg | 25‐75 mg | > 75 mg |

| Bupropion | n/aa | 150‐300 mg | > 300 mg |

| Citalopram | < 20 mg | 20 mg | 40 mg |

| Clomipramine | < 30 mg | 30‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Desipramine | < 100 mg | 100‐200 mg | > 200 mg |

| Desvenlafaxine | n/ab | 50 mg | > 50 mg |

| Dothiepin (dosulepin) | < 75 mg | 75‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Doxepin | < 75 mg | 75‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Duloxetine | < 60 mg | 60 mg | > 60 mg |

| Escitalopram | < 10 mg | 10 mg | 20 mg |

| Esreboxetine | n/ac | 4‐8 mg | > 8 mg |

| Fluoxetine | < 20 mg | 20‐40 mg | > 40 mg |

| Imipramine | < 75 mg | 75‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Nortriptyline | < 75 mg | 75‐100 mg | > 100 mg |

| Maprotiline | 150 mg | 300 mg | > 300 mg |

| Mianserin | < 30 mg | 30‐40 mg | > 40 mg |

| Milnacipran | < 100 mg | 100 mg | > 100 mg |

| Mirtazapine | < 30 mg | 30 mg | > 30 mg |

| Moclobemide | 150 mg | 300 mg | 600 mg |

| Paroxetine | < 20 mg | 20 mg | 50 mg |

| Pirlindole | < 225 mg | 225‐300 mg | > 300 mg |

| Reboxetine | < 8 mg | 8 mg | > 8 mg |

| Sertraline | n/ad | 50 mg | > 50 mg |

| Trazodone | < 150 mg | 150‐300 mg | > 300 mg |

| Trimipramine | < 75 mg | 75‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Venlafaxine | < 75 mg | 75‐150 mg | > 150 mg |

| Zimelidine | < 300 mg | 300 mg | > 300 mg |

aLowest dose form is 150 mg.

bDesvenlafaxine is not available in UK, lowest dose form is 50 mg.

cEsreboxetine is not available in UK, and no doses lower than 4 mg have been used in trials.

d50 mg is both the initial and standard dose, no recommendations of lower doses in the British National Formulary.

Standard doses were the recommended doses for depression in adults. Low doses were those listed as initial doses (where a standard range is specified), the dose for elderly patients, or any dose below the standard dose (where no range was specified). High doses were those listed at the upper range of standard dose ranges, or above the standard dose where no range is specified. Where studies included flexible dosing across multiple categories and did not report mean dose, we labelled them as ‘unable to be categorised’.

Supplementary sets

We included studies with any active comparator. We included studies where the antidepressant is combined with another intervention, as long as there was an arm solely for the other intervention, so we were able to isolate the effects of the antidepressant (e.g. antidepressant + drug versus drug). We did not include combination studies where there was no way to isolate the effects of an antidepressant (e.g. antidepressant A + drug versus antidepressant B). For this review we assumed that any participant who met the inclusion criteria was, in principle, equally likely to be randomised to any of the eligible antidepressants; however, we acknowledge there may have been differences in patients’ expectations of treatment and outcomes depending upon which antidepressant was studied.

Types of outcome measures

We anticipated that there would be a variety of outcome measures used throughout the literature. Due to the distinction between distress and depression discussed above, this review used the term 'mood' as an outcome, to include depression that is diagnosed, mood that is measured via self‐report, and distress.

For pain and mood, where applicable we also dichotomised outcomes into pain relief or improvement of 50% or greater, in line with the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) guidance, to indicate substantial improvement (Dworkin 2008). Where possible, we planned separate NMAs to compare antidepressants to the comparators immediately post‐intervention, at short‐term follow‐up (12 weeks or less post‐treatment) and long‐term follow up (over 12 weeks post‐treatment). Where studies included multiple follow‐up time points, we took the most recent time point within each period. If multiple measures were used for the same outcome (e.g. for continuous pain intensity both a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack 1975) were reported), then we extracted from the most valid, reliable, and widely used measure in the field.

Primary outcomes

Substantial pain relief: proportion of participants (number and percentage of total and per arm) reporting at least 50% reduction in pain intensity from baseline, irrespective of pain measurement method (e.g. visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale)

Pain intensity: continuous data from any measures of pain intensity or severity (e.g. visual analogue scale or validated measures such as Brief Pain Inventory)

Mood: continuous data from any measures of mood (e.g. visual analogue scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale)

Adverse events: the proportion of participants (number of percentage of total and per arm) reporting adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Moderate pain relief: the proportion of participants (number and percentage of total and per arm) reporting at least 30% reduction in pain intensity from baseline, irrespective of pain measurement method (e.g. visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale).

Physical function: continuous data from any measures of physical movement and disability, e.g. numerical rating scale, SF‐36 Physical Component Score)

Sleep: continuous data from any measures of quality of sleep, including insomnia, restfulness, etc. (e.g. Brief Pain Inventory, Jenkins Sleep Scale)

Quality of life: continuous data from any measure of quality of life (e.g. numerical rating scale, EQ‐5D)

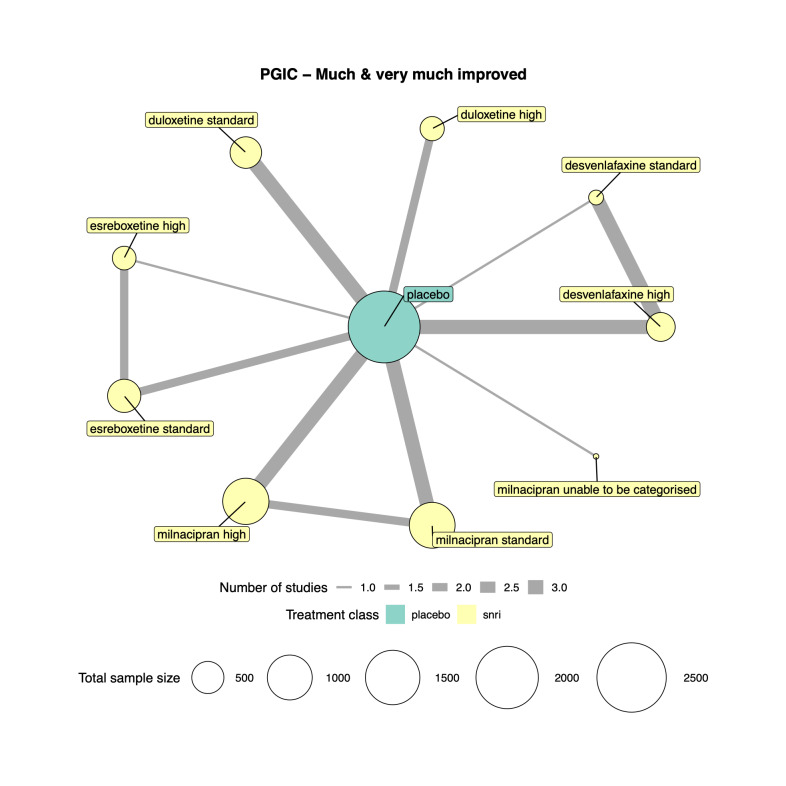

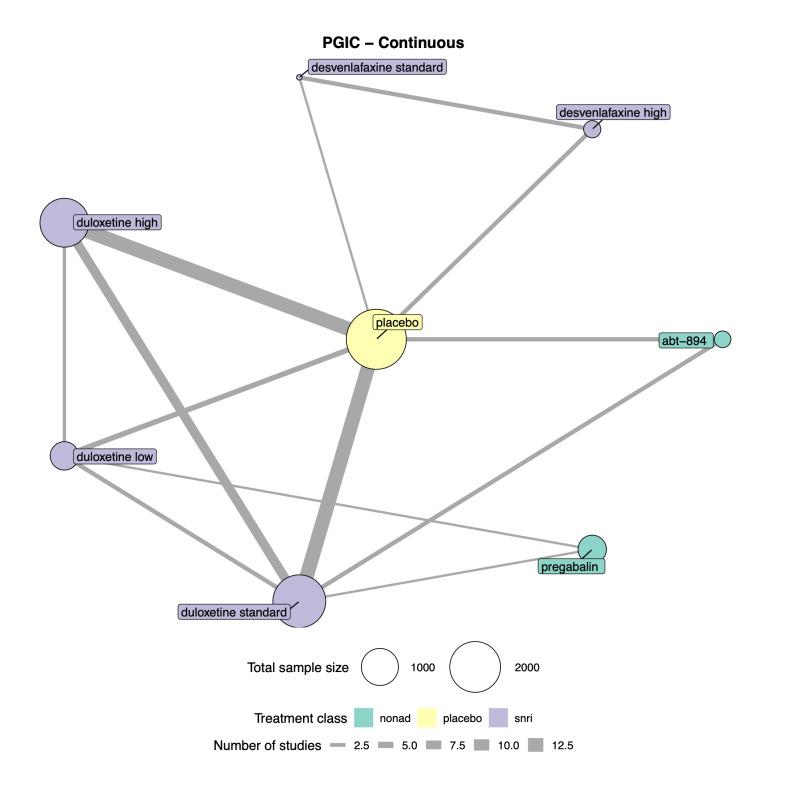

Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC): the proportion of participants (number and percentage of total and per arm) reporting "much" and "very much" improved on the PGIC scale, and continuous data from the PGIC scale.

Serious adverse events: the proportion of participants (number of percentage of total and per arm) reporting serious adverse events).

Withdrawal: the proportion of participants (number and percentage of total and per arm) withdrawing for any reason.

Search methods for identification of studies

This search was last run on 4 January 2022.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases, without language restrictions.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 12) via the Cochrane Library (searched 4 January 2022)

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In‐Process (via OVID) ‐ 1946 to 4 January 2022

Embase (via OVID) ‐ 1974 to 4 January 2022

CINAHL (via EBSCO) ‐ 1981 to December 2021

LILACS (via Birme ‐ 1982 to Dec 2021)

PsycINFO (via EBSCO)) ‐ 1872 to 4 January 2022

AMED (via OVID) ‐ 1985 to December 2021

We tailored searches to individual databases. The search strategies used can be found in Appendix 1. The search strategy was developed by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care (PaPaS) Review Group’s Information Specialist and was independently peer‐reviewed. The PaPaS Information Specialist performed the searches.

Searching other resources

We searched ClinicalTrials.govand the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for unpublished and ongoing studies. In addition, we searched grey literature, checked reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies, and performed citation searches on key articles. We contacted study authors for additional information where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HB and CF) independently determined eligibility of each study identified by the search. Review authors independently eliminated studies that clearly did not satisfy inclusion criteria, and obtained full copies of the remaining studies. HB and CF read these studies independently to select relevant studies, and in the event of a disagreement, third and fourth authors adjudicated (TP and CE). We did not anonymise the studies in any way before assessment. We have included a PRISMA flow chart that shows the status of identified studies (Moher 2009), as recommended in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2022). We included studies in the review irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported in a 'useable' way. We recorded reasons for exclusion of any ineligible studies at the full‐text stage.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (HB and CF) independently extracted data using a standard piloted form and checked for agreement before entry into Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2023). In the event of disagreement, third and fourth authors (TP and CE) adjudicated. We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We collected characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate the table of 'Characteristics of included studies'. We extracted the following information.

Study design: authors, publication year and journal, duration, sponsorship, conflicts of interest, aim (pain or emotional functioning), design, number of treatment arms, setting, missing data methods, power calculation used, definition of chronic pain, minimum level of pain for entry, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Setting

Participant characteristics: overall number, number in each arm, withdrawal (total, per arm and by sex), type of participant, chronic pain conditions, sex, age, baseline differences

Intervention: type of antidepressant, class, dose (freeform and dichotomised), route of administration, duration

Comparator(s): type (e.g. placebo, psychological therapy), description (if placebo medication: active or inert, appearance, taste, smell, titration, number of tablets), type and class (if other antidepressant), doses, route of administration, length, intensity (if physical or psychological comparator)

Outcomes (data from all time points reported in the study): domain (e.g. pain, physical functioning), measure, measure validation, baseline data, results for each time point, effect sizes

Adverse events and withdrawals (proportion overall and per arm): any, serious, withdrawal due to adverse event, withdrawal due to lack of efficacy

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (HB and CF) independently assessed risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), with any disagreements resolved by discussion. We completed a risk of bias table for each included study using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 1) in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020).

We assessed the following for each study.

-

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence as being at:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator); or

unclear risk of bias (method used to generate sequence not clearly stated).

We excluded studies using a non‐random process (e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

-

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). The method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment determines whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes); or

unclear risk of bias (method not clearly stated).

We will exclude studies that do not conceal allocation (e.g. open list).

-

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). Due to the inclusion of studies using any comparator, our review will contain both double‐blinded RCTs and those studies in which double‐blinding is not possible (i.e. RCTs of psychological therapy or acupuncture). In the RCTs that are double‐blinded, we assessed the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received in the double‐blind trials. We assessed methods as being at:

low risk of bias (the study states that it was blinded and describes the method used to achieve blinding, such as identical tablets matched in appearance or smell, or a double‐dummy technique); or

unclear risk of bias (the study states that it was blinded but does not provide an adequate description of how this was achieved).

Studies in which double‐blinding was not possible due to the comparator will be considered to have high risk of bias.

-

Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias). We assessed the methods used to blind study participants and outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (the study has a clear statement that outcome assessors were unaware of treatment allocation, and ideally describes how this was achieved);

unclear risk of bias (the study states that outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation but it lacks a clear statement on how this was achieved); or

high risk of bias (the outcome assessment was not blinded).

-

Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias). We assessed whether primary and secondary outcome measures were pre‐specified and whether these were consistent with those reported. We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (study protocol is available with pre‐specified measures);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient information available to permit a judgement of high or low risk of bias); or

high risk of bias (not all of the study’s prespecified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes have been reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not prespecified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review have been reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report failed to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study).

-

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data). We assessed the methods used to deal with incomplete data as being at:

low risk of bias (no missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data are unlikely to be related to the true outcome; missing outcome data are balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; missing data have been imputed using 'baseline observation carried forward’ (BOCF) analysis);

unclear risk of bias (insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias (e.g. number randomised not stated; no reasons for missing data provided; or the study did not address this outcome)); or

high risk of bias (the reason for missing outcome data is likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; ‘as‐treated’ analysis was done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation; use of 'last observation carried forward’ (LOCF) without the addition of any other low risk of bias methods).

Other bias. We assessed any other potential sources of bias that were not included in the other domains.

We considered studies to be at high risk of bias overall if they met the criteria for high risk of bias in any of the above domains.

Measures of treatment effect

For the outcomes measuring continuous data (pain intensity, mood, physical function, sleep, quality of life, and PGIC continuous), studies reported data as either post‐intervention scores (the mean scores at the end of the intervention period) or change scores (mean change from baseline score). We conducted separate analyses for these. As is common in pain management studies, for all outcomes (apart from PGIC) studies used a broad range of scales to measure the outcomes. Therefore, once data were extracted, we converted them into standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We interpreted SMD as small (0.2), moderate (0.5) and large (0.8), in line with Cohen 1988 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022a). For outcomes with dichotomous data (substantial pain relief, adverse events, moderate pain relief, PGIC much/very much improved, serious adverse events, and withdrawal), we used odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

For most RCTs, we did not encounter any unit of analysis complexities as participants were randomised to different study arms, allowing direct analysis. For cross‐over RCTs, if the results for the first period (prior to cross‐over) were reported, we extracted these in an attempt to avoid cross‐over effects. If the results from the first period were not reported then we extracted the final study results, provided there was a sufficient washout period of at least five times the length of the antidepressant half‐life (minimum washout period length calculated separately for each antidepressant). The majority of cross‐over trials reported the combined effects of both periods (only one study reported first period and second period effects separately), therefore we analysed cross‐over trials using these combined effects. Our search did not return any cluster‐RCTs that met our inclusion criteria.

Dealing with missing data

For all missing study‐level statistical data relevant to our outcomes we first tried to contact the authors of the study. If we could not get the data from the authors, then we followed the guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2022). If standard deviations were missing then we used the Review Manager calculator (RevMan Web 2023) to calculate these from other data reported in the study. We did not impute any data, but assessed each study’s risk of bias due to missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity within the network meta‐analyses using the Tau statistic, in line with the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2022). We assessed heterogeneity using Confidence in Meta‐Analysis (CINeMA) software, which calculated the Chi² test and the I² statistic for each pairwise comparison on each outcome (Nikolakopoulou 2020). As outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we interpreted the I² statistic as follows (Deeks 2022).

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 50%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

We took into account the magnitude and strength of effects when assessing heterogeneity.

Assessment of the transitivity assumption

We carefully scrutinised transitivity, which is the key underlying assumption of NMA. Transitivity requires studies to be similar on average across all factors that might alter treatment effects other than the intervention comparison being made (Chaimani 2022). To address this, we only included studies with similar clinical populations (i.e. participants reporting pain lasting at least three months; Furukawa 2016). Previous research, combined with review authors' clinical experience and knowledge, identified variables that could potentially influence our primary outcome:

pain condition;

age;

pain intensity at baseline;

depressive severity at baseline;

treatment duration; and

dosing schedule.

We explored the impact of these factors by assessing the indirectness of the network.

The inclusion of placebo and concerns about its potential to violate the transitivity assumption have been highlighted in general (Cipriani 2013), and particularly in depression studies (Rutherford 2009). Therefore, we explicitly compared placebo‐controlled studies with those that provide head‐to‐head evidence as a form of validation of the network.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting biases using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 1) in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020), by checking for study protocols and pre‐specified outcomes (as detailed in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section). We also used funnel plots for pairwise analyses for antidepressants where more than 10 studies were available, as advised in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Page 2022). Funnel plots were drawn using ROB‐MEN, which is part of CINeMA, and used to assess the significant small study effects via funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We undertook separate NMAs for each outcome. NMAs combine information (evidence) from both direct comparisons of interventions within RCTs, and indirect comparisons across studies based on a common placebo comparator (Caldwell 2005; Jansen 2011). Direct comparisons (direct evidence) occur when two or more interventions are compared head to head in a study; in the absence of head‐to‐head comparisons, interventions can be indirectly compared (indirect evidence).

We analysed the data for all primary and secondary outcomes using Bayesian random‐effects NMAs implemented using the R (r-project.org) package multinma (Phillippo 2022). Where dose was included in the network, we categorised them (low, standard, high) and incorporated them as separate nodes. Where a study had multiple arms investigating different doses of the same antidepressant that fall into in the same category (e.g. two different low doses), we did not combine them; by using the multinma package we were able to keep these as separate arms in the analysis.

We fitted random‐effects models using broad normal prior distributions for the treatment effects, and study‐specific intercepts and a half‐normal prior for the heterogeneity standard deviation. We used four chains, each with 2000 iterations and 1000 post‐warm up draws per chain.

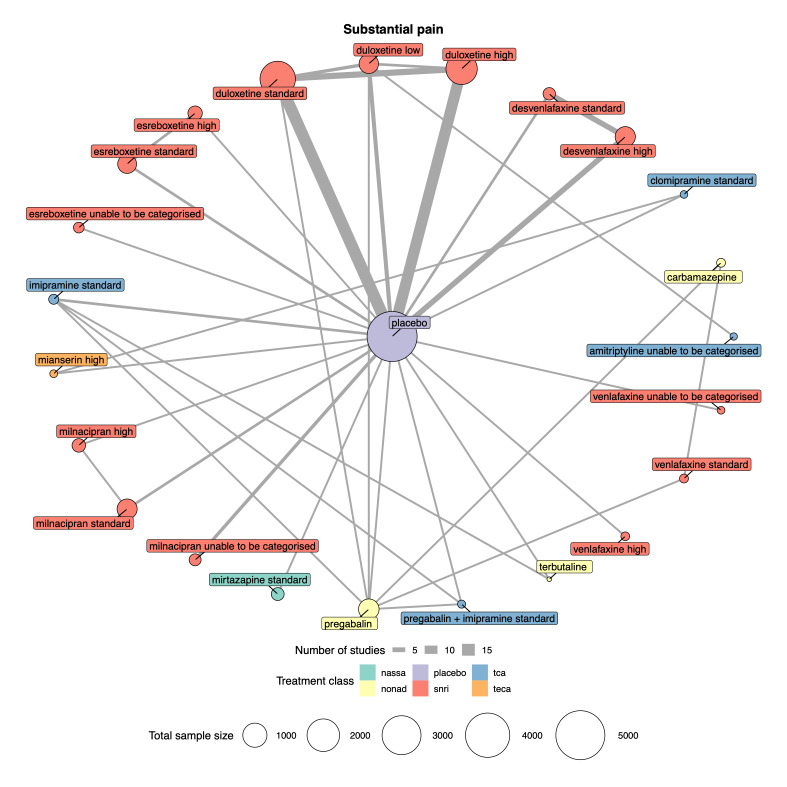

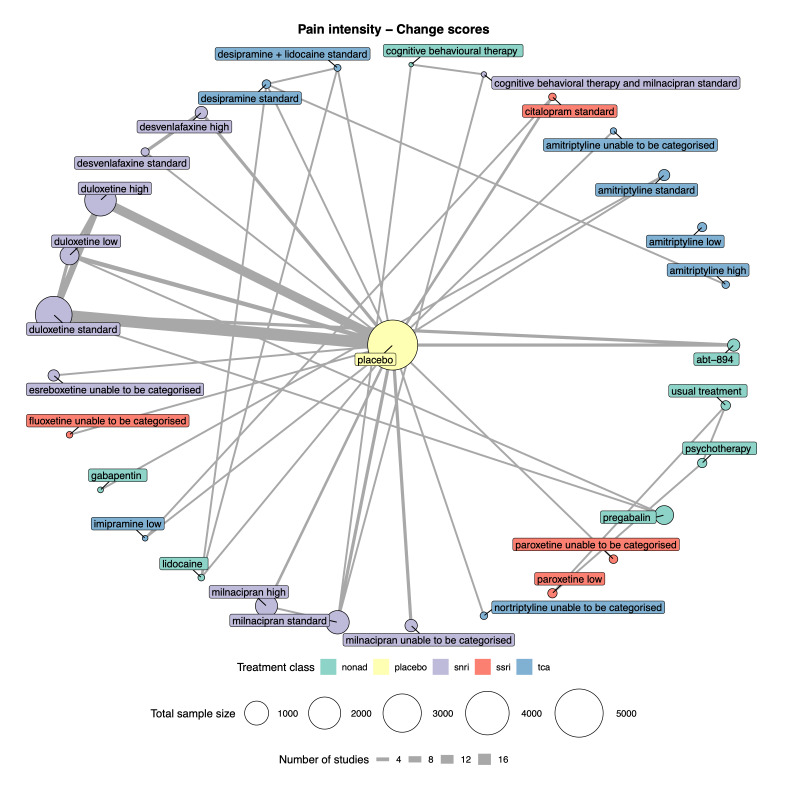

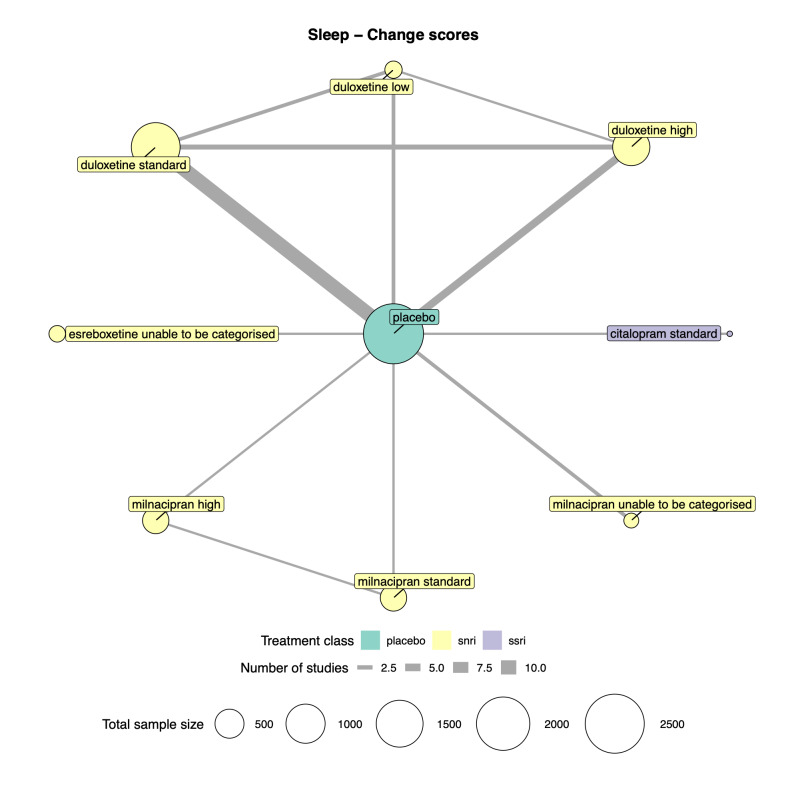

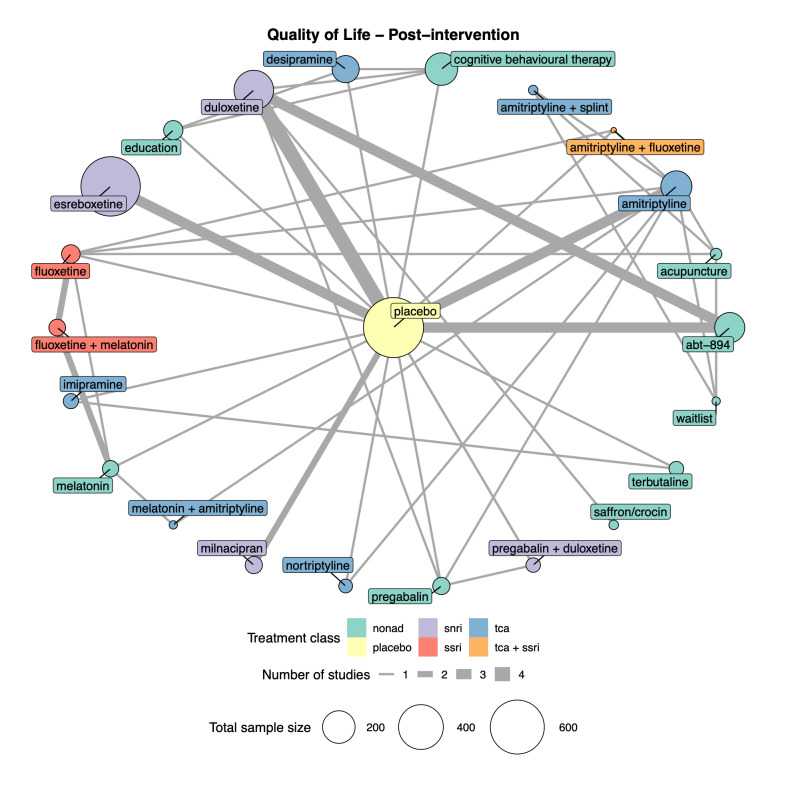

We explored network connectivity via network plots. In the network plot, for treatment‐only models, the nodes represent each intervention. In treatment‐dose models, the antidepressant nodes represent the antidepressant and dose (low, standard, high). The colour of the node represents the antidepressant class, and the "nonad" label refers to all interventions that were not an antidepressant. The size of each node represents the combined sample size of participants from all studies investigating that intervention, and the thickness of the lines represents the number of studies for that comparison. The forest plots present the estimates and credible intervals for each intervention in the network, with reference to placebo.

We assessed convergence using the potential scale reduction factor for each parameter, ensured that effective sample sizes were sufficiently large (Vehtari 2021), and verified that there were no divergent transitions (Betancourt 2015). We explored heterogeneity by fitting connected networks for treatment, treatment‐dose, class, risk of bias, and condition where network geometry allowed sufficient connectivity (Dias 2013).

We assessed model fit using mean residual deviance, and explored inconsistency through unrelated mean‐effect models (UME) and node‐splitting where network geometry allowed (Dias 2013a). We used dev‐dev plots, which compare residual deviance contributions from each model, to explore inconsistency. The data points are plotted against a line of equality; points on the line fit equally well under either model, whereas points above or below the line indicate better fits for one of the two models (Phillippo 2022). Node‐splitting plots present the evidence of direct, indirect, and combined evidence on the same plot to allow comparisons.

We reported effect estimates and cumulative posterior ranks of effect alongside strength of evidence assessment using GRADE (Schünemann 2013).

To rank the treatments for each outcome by probability of best treatment, we used the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and the mean ranks. We reported relative effects and mean rank of treatments and plotted cumulative rankograms showing the range of rankings of different treatments for each outcome.

We used the deviance information criterion (DIC) to compare the different models for reporting (treatment only, treatment‐dose, class and, change score and post‐intervention studies for contrast‐based models) to assess their parsimony. Substantive differences in DIC (> 5) or models with marginally lower DIC but lower Tau and fewer studies with residual deviance greater than 3 in combination were deemed superior. We selected models to report on the basis of parsimony, minimisation of inconsistency (identified via UME and node‐splitting models), residual deviance and heterogeneity (measured as Tau). This approach balanced clinical exploration of results and the risk of overfitting (Dias 2013).

NMA, UME and node‐splitting models were implemented in multinma in R (version 4·1.3). Further details of the modelling framework are described by Phillippo 2018; Phillippo 2022.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where data allowed, we performed subgroup analyses for the following factors.

Class of antidepressant (SSRI, SNRI, TCA, MAOI, etc.)

Type of pain condition

We used a Bayesian random‐effects NMA to account for expected heterogeneity and variation in the data. These methods allowed the uncertainty inherent in the between‐study variance component to be reflected in effect estimate precision. We performed these subgroup analyses by building separate models, however this was dependent on the geometry and connectedness of the networks.

Due to sparsity of data, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses for the following factors for any outcome.

-

Aim of the study (i.e. whether the intervention is aimed at pain or mood)

Only one study had a main aim of addressing mood (Richards 2015)

-

Baseline level of depression (none, mild, moderate, severe, as defined by the individual measure criteria)

Upon examination, the average scores for the five most commonly used scales (Beck Depression Inventory, Brief Pain Inventory Mood Item, SF‐36 Mental Component Score, SF‐36 Mental Health Subscale, and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) were all in the none/minimal ranges.

Sensitivity analysis

We could only undertake analysis by risk of bias judgement (high and not high) for substantial pain relief. We were unable to perform sensitivity analyses for any outcome that compared active placebo to inert placebo, as in total only nine studies used an active placebo.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

To assess the certainty of the NMA, we primarily used the CINeMA framework (Nikolakopoulou 2020). In contrast to the NMAs in this review, which were conducted within a Bayesian framework, CINeMA operates within a frequentist framework using the netmeta package in R (Rücker 2017). The CINeMA framework considers the impact of certain issues within NMAs on clinical decision making made from the results. This framework is based on GRADE, and considers the following six domains specific to NMA (Nikolakopoulou 2020).

-

Within‐study bias (impact of risk of bias in the included studies)

CINeMA assesses the impact of risk of bias by combining the study's risk of bias (as judged by the review authors using a risk of bias tool) with its contribution to the network meta‐analysis.

-

Reporting bias (publication and other reporting biases)

Reporting bias in CINeMA is categorised as either 'suspected' or 'undetected'. Suspected reporting bias is when the review methods do not take into account unpublished data, the meta‐analysis is based on a small number of positive early findings, or treatments are exclusively studied in industry‐funded studies. Undetected reporting bias is when data from unpublished studies has been identified and findings agree, when prospective trial registration has been completed and there are no deviations from protocols, and comparisons of estimates between small and large studies agree.

-

Indirectness (relevance to the research question, addressing transitivity)

Each study in the NMA is evaluated according to its relevance to the research question. Study‐level judgements are combined with the percentage contribution of the study to the network. This approach assesses potential transitivity issues in the NMA.

-

Imprecision (the precision of the NMA, by combining direct with indirect evidence)

Relevant treatment effects that represent a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) are defined and the range of clinical equivalence is produced (the value of the MCID either side of the line of no effect). CINeMA then compares the treatment effects included in the 95% CI to the range of clinical equivalence. If the 95% CI of a treatment effect crosses the range of clinical equivalence, then it is considered to have major concerns of imprecision. If the 95% CI of a treatment effect only crosses one side of the range of equivalence then there are no concerns of imprecision.

-

Heterogeneity (variability in the results of studies)

CINeMA accounts for both heterogeneity between studies by comparing the confidence and prediction intervals of a treatment effect. When confidence and prediction intervals indicate the same effect, then there is no evidence of heterogeneity; conversely if a prediction interval leads to a different conclusion than the CIs then there is evidence of heterogeneity.

-

Incoherence (agreement between the results of direct and indirect evidence)

This is the variation between direct and indirect evidence in the network and also an assessment of transitivity. CINeMA compares the 95% CIs of the estimates of the direct and indirect estimates. If both of these estimates lie on the same side of the range of clinical equivalence, then there are no concerns about incoherence.