Abstract

Background

Lingering symptoms have been reported by survivors of Ebola virus disease (EVD). There are few data describing the persistence and severity of these symptoms over time.

Methods

Symptoms of headache, fatigue, joint pain, muscle pain, hearing loss, visual loss, numbness of hands or feet were longitudinally assessed among participants in the Liberian Ebola Survivors Cohort study. Generalized linear mixed effects models, adjusted for sex and age, were used to calculate the odds of reporting a symptom and it being rated as highly interfering with life.

Results

From June 2015 to June 2016, 326 survivors were enrolled a median of 389 days (range 51–614) from acute EVD. At baseline 75.2% reported at least 1 symptom; 85.8% were highly interfering with life. Over a median follow-up of 5.9 years, reporting of any symptom declined (odds ratio for each 90 days of follow-up = 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI]: .95, .97; P < .0001) with all symptoms declining except for numbness of hands or feet. Rating of any symptom as highly interfering decreased over time. Among 311 with 5 years of follow-up, 52% (n = 161) reported a symptom and 29% (n = 47) of these as highly interfering with their lives.

Conclusions

Major post-EVD symptoms are common early during convalescence and decline over time along with severity. However, even 5 years after acute infection, a majority continue to have symptoms and, for many, these continue to greatly impact their lives. These findings call for investigations to identify the mechanisms of post-EVD sequelae and therapeutic interventions to benefit the thousands of effected EVD survivors.

Keywords: Ebola, Post-Ebola syndrome, symptoms

Post-Ebola symptoms declined over a median of 6 years from acute infection, but at 5 years more than half of survivors report 1 or more [post-Ebola symptoms, with 1 in 3 describing symptoms as highly interfering with life.

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a multi-system illness with a case fatality rate between 30% and 70% [1–3]. The clinical manifestations of acute EVD have been well described; however, less is known about the longer-term clinical sequelae experienced by EVD survivors. Of the approximately 28 000 persons diagnosed with EVD during the 2014–15 outbreak in West Africa, an estimated 17 000 survived and persistent musculoskeletal, neurologic, and ocular symptoms, as well as menstrual irregularities and chronic fatigue during the months following acute infection have been reported to occur in as many as 70% survivors [4–15].

Observations of post-Ebola symptomatology have largely been cross-sectional. An exception is a report from the National Institute of Health (NIH) PREVAIL-III study, a longitudinal cohort of Liberian EVD survivors that assessed participants for post-EVD symptoms at 6 and 12 months following study entry, which was approximately 1 year following acute EVD [15]. Multiple symptoms were prevalent at study entry and declined during the year-long follow-up although, some such as headache and joint pain remained present in up to a third of participants. Furthermore, the prevalence of uveitis on ophthalmologic examination increased between the 2 study time points. Follow-up in this study was limited to approximately 2 years following acute EVD. Longer term data on post-EVD symptomatology has not been reported by any other cohorts of survivors.

As the duration and severity of the health issues experienced by EVD survivors remains unknown, we aimed to characterize longer-term post-EVD symptoms among participants in the Liberian Ebola Survivors Study, an ongoing observational cohort of EVD survivors [16]. The persistence of symptoms that developed following acute EVD were assessed for up to 6 years after infection. As medical countermeasures such as vaccines and therapeutics were not available in Liberia, the symptoms assessed reflect those that occur in the absence of such measures.

METHODS

Study Participants and Setting

The Liberian Ebola Survivor Study is a longitudinal observational cohort study based at the Eternal Love Winning Africa (ELWA) Hospital, outside Monrovia, Liberia [16]. Individuals who are at least 5 years of age with a history of prior EVD as evidenced by a discharge certificate from an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU) verified by photo identification and willing and able to consent were enrolled between June 2015 through June 2016. All participants 18 years of age and older provided written informed consent. Verbal assent was obtained from minors younger than age 18 years along with written consent from their parent/guardian following the reading of the consent document to both. Institutional review board approvals were obtained from the University of North Carolina and the University of Liberia.

Symptoms Assessments

Study visits were scheduled every 3 months from the study launch in June 2015 until October 2019 when the visit frequency was modified to every 6 months. Data collected through 8 March 2022 are presented. At each study visit participants were surveyed in Liberian English by trained research staff. Surveys included a symptom assessment which is an expansion of the Wahler Physical Symptoms Inventory [11] with cardinal symptoms described by survivors from earlier outbreaks of Ebola. Participants were asked if they experienced a listed symptom (at baseline visit: since discharge from the ETU, at follow-up: since last study visit) and whether the symptom existed before acute EVD. Only symptoms that emerged since ETU discharge were further characterized, including if present at the time of the interview and, if so, the severity. The severity of a symptom was assessed by the degree that it interfered in the participant's life. Originally, the response options included a 4-choice Likert scale: (1) Does not interfere at all, (2) Interferes very little, (3) Interferes somewhat, (4) Interferes very much. However, in August 2017, the survey was modified as it was evident some participants struggled to differentiate between the middle 2 options. Following discussion among the Liberian research staff, the Likert scale was reduced to three options and rephrased using more commonly used terms for the same concepts of severity to: (1) Does not interfere at all, (2) Interferes small, (3) Interferes plenty. For the purposes of the analyses, in the coding of the original four options, the middle 2 choices were collapsed.

Statistical Analyses

To understand symptoms persistence in participants since their ETU discharge, time was calculated using the participant ETU discharge date and visit date. Since the enrollment (baseline) dates for the participants vary from 51 days to 614 days, a new ordinal variable time was created such that each value is a 3-month period. For example, time = 1 when a participant had a visit between 51 and 140 days, time = 2 when a participant has a visit between 141 and 230 days, and so on; 51 days was used as the starting date since this was the shortest number of days from ETU discharge. From study launch in June 2015 to September 2019, participants were scheduled to attend study visits every 3 months with a visit window of 2 weeks on either side of the target visit date. After September 2019, visits were scheduled every 6 months with a window of 2 weeks on either side of the target visit date. When more than 1 study visit occurred within a time group data from the later visit were used. As a result, a total of 343 out of 6102 study visits were dropped due to duplicated visits in the same time group.

For the analysis of determining the persistence of having at least one cardinal symptom or a specific cardinal symptom, generalized linear mixed effects models with a logit link and an autoregressive error were used. The autoregressive error matrix was used to capture the correlation among the responses between visits for the same individual. The covariate time is defined in the above paragraph. The models are adjusted for covariates sex and age.

To understand the group of individuals who experienced highly interfering symptoms, the aforementioned generalized linear mixed effects models were utilized. Participants who did not have any highly interfering symptoms were excluded from this analysis. Participants who did not experience a symptom during their baseline visit or 1st follow-up visit were also excluded from this analysis. The models are used to determine the persistence of highly interfering symptoms, thus individuals with no interfering and little interfering symptoms were categorized in the same group.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

From June 2015 to June 2016, 326 participants were recruited; their median age at study entry was 31.5 years (range 5.1–68.6), and 44.8% were female. The median time from ETU discharge to study entry was 389 days (range 51–614). Median participant study follow-up from study entry is 5.9 years (range 0.8–6.1). Of the 326 participants initially enrolled, 20 have relocated beyond travel distance to the research site and were considered lost to follow-up, 3 died (hypertensive disease, sepsis, sudden death), and 1 withdrew consent.

Post-EVD Symptoms at Entry

At baseline, 245 (75.2%) reported experiencing at least one cardinal symptom that developed after acute EVD and was present at the time of the assessment (Table 1). The most common of these symptoms were 1 or more of the following: joint pain, headache, and fatigue and 34.0%, 26.7%, and 23.4% of the participants with these symptoms rated them as highly interfering with life, respectively. For 85.8% of those with any cardinal symptom at baseline, the participant rated at least 1 symptom as highly interfering.

Table 1.

Cardinal Post-EVD Symptoms and Interference With Life Reported by Survivors at Cohort Study Entry

| Symptom | Presence/Severity | N = 326 (%) | Presence/Severity | N = 311 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Study Entry Median Time From ETU Discharge = 389 d (range 51–614 d) | At 5 y From ETU Discharge | |||

| Have ≥1 symptom | No | 81 (24.8) | No | 150 (48.2) |

| Yes | 245 (75.2) | Yes | 161 (51.8) | |

| Fatigue | Not present | 226 (69.3) | Not present | 273 (87.8) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 24 (7.4) | ȃNo interference | 2 (0.6) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 63 (19.3) | ȃInterferes some | 27 (8.7) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 13 (3.9) | ȃInterferes a lot | 9 (2.9) | |

| Numbness in feet | Not present | 274 (84.0) | Not present | 270 (86.8) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 10 (3.1) | ȃNo interference | 3 (1.0) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 25 (7.7) | ȃInterferes some | 27 (8.7) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 17 (5.2) | ȃInterferes a lot | 11 (3.5) | |

| Numbness in hands | Not present | 286 (87.7) | Not present | 273 (87.8) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 9 (2.7) | ȃNo interference | 1 (0.3) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 21 (6.4) | ȃInterferes some | 26 (8.4) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 10 (3.1) | ȃInterferes a lot | 11 (3.5) | |

| Headache | Not present | 220 (67.5) | Not present | 248 (79.7) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 19 (5.8) | ȃNo interference | 4 (1.3) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 69 (21.2) | ȃInterferes some | 46 (14.8) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 18 (5.5) | ȃInterferes a lot | 13 (4.2) | |

| Hearing loss | Not present | 314 (96.3) | Not present | 302 (97.1) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 3 (0.9) | ȃNo interference | 1 (0.3) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 6 (1.9) | ȃInterferes some | 6 (1.93) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 3 (0.9) | ȃInterferes a lot | 2 (0.6) | |

| Joint pain | Not present | 198 (60.7) | Not present | 262 (84.2) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 17 (5.2) | ȃNo interference | 1 (0.3) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 70 (21.5) | ȃInterferes some | 35 (11.3) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 41 (12.6) | ȃInterferes a lot | 13 (4.2) | |

| Muscle pain | Not present | 282 (86.8) | Not present | 311 (100) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 2 (0.6) | ȃNo interference | 0 (0.0) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 30 (0.9) | ȃInterferes some | 0 (0.0) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 11 (3.4) | ȃInterferes a lot | 0 (0.0) | |

| Vision problems | Not present | 267 (81.9) | Not present | 257 (82.6) |

| Present | … | Present | … | |

| ȃNo interference | 4 (1.2) | ȃNo interference | 0 (0.0) | |

| ȃInterferes some | 39 (12.0) | ȃInterferes some | 47 (15.1) | |

| ȃInterferes a lot | 16 (4.9) | ȃInterferes a lot | 7 (2.3) | |

Abbreviations: ETU, Ebola Treatment Unit; EVD, Ebola virus disease.

Post-EVD Symptoms Prevalence and Severity During Follow-Up

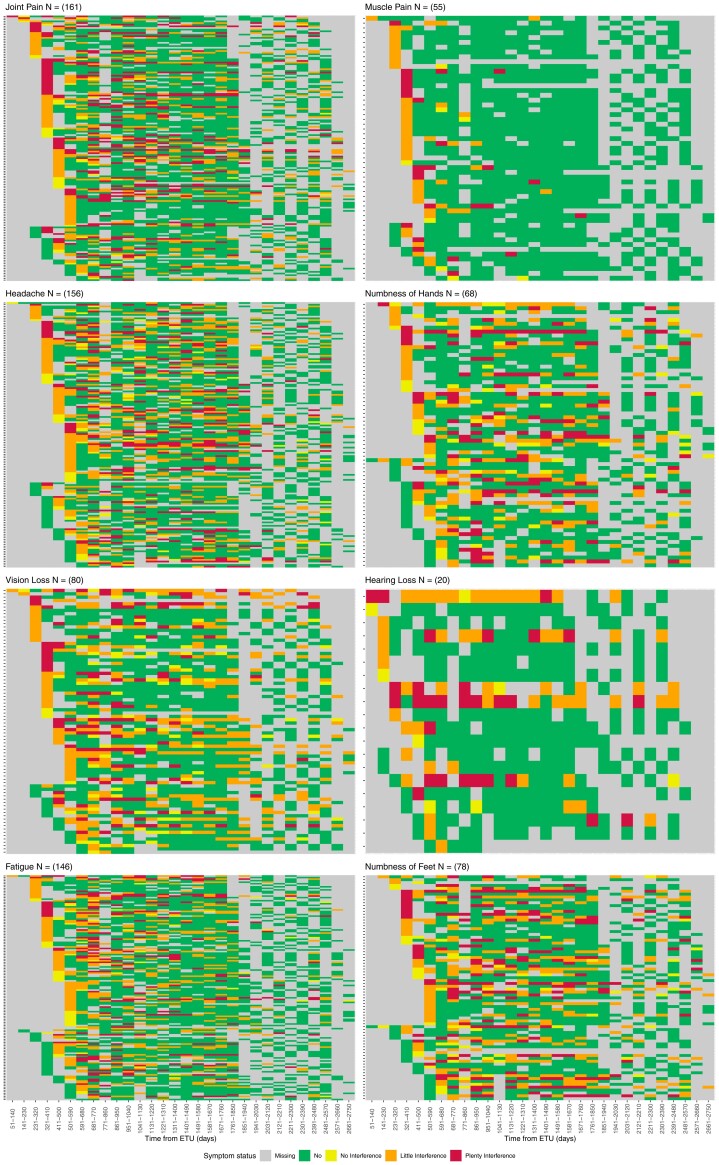

After adjusting for age and sex, the odds of reporting any cardinal symptom significantly decreased for every 3-month follow-up period (odds ratio [OR] = 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI]: (.95, .97); P < .001) (Table 2). Of the 8 cardinal symptoms (headache, fatigue, hearing loss, joint pain, muscle pain, and vision loss), each significantly decreased during follow-up (Figure 1). In contrast, numbness in feet and numbness in hands did not significantly decline over the study period. Symptom severity significant decreased with reports of symptoms highly interfering with life becoming less likely for each individual cardinal symptom (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds of Post-Ebola Symptoms Being Present and Highly Interfering Over Time

| Symptom | Presence (N = 326) | Severitya (N = 277) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value | |

| Any symptom | 0.96 | (.95, .97) | <.0001 | 0.94 | (.93, .95) | <.0001 |

| Fatigue | 0.94 | (.93, .95) | <.0001 | 0.94 | (.92, .96) | <.0001 |

| Numbness of feet | 0.99 | (.98, 1.01) | .3642 | 0.95 | (.93, .97) | .0081 |

| Numbness of hands | 0.99 | (.99, 1.01) | .9916 | 0.96 | (.94, .99) | <.0001 |

| Headache | 0.96 | (.95, .97) | <.0001 | 0.95 | (.94, .97) | <.0001 |

| Hearing loss | 0.96 | (.92, .99) | .0071 | 0.81 | (.77, .87) | <.0001 |

| Joint pain | 0.95 | (.94, .97) | <.0001 | 0.92 | (.91, .94) | <.0001 |

| Muscle pain | 0.80 | (.77, .84) | <.0001 | 0.77 | (.70, .85) | <.0001 |

| Visual loss | 0.98 | (.97, .99) | .0113 | 0.90 | (.87, .94) | <.0001 |

Adjusted for year, age, and sex.

Severity among those reporting symptom at study entry and/or subsequent study visit.

Figure 1.

Heat maps of cardinal post-EVD symptoms indicating symptom presence and severity among those who reported a symptom at entry and/or first follow-up study visit. Abbreviation: EVD, Ebola virus disease.

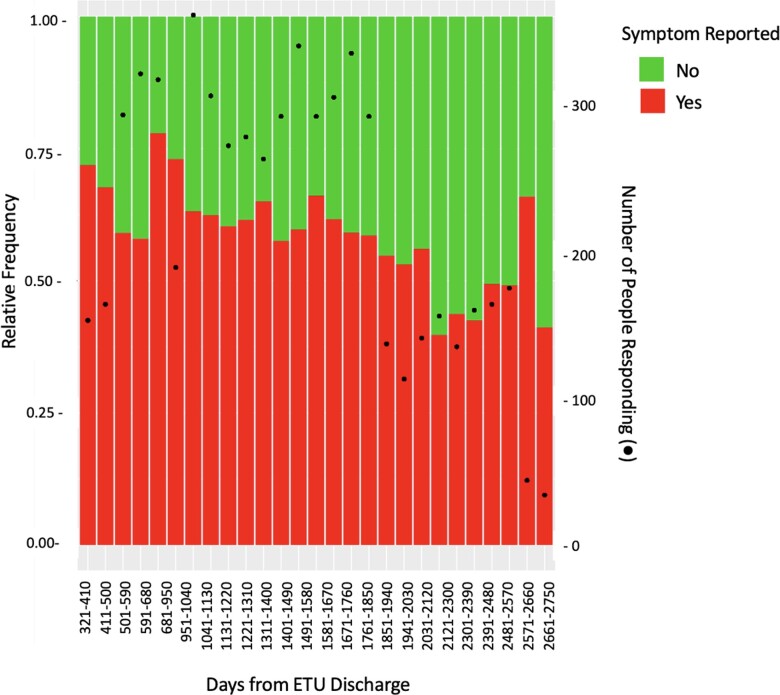

Among the 311 participants with at least 5 years (1825 days) of study follow-up, 52% (n = 161) reported a cardinal symptom at the visit closest to this timepoint (Figure 2) and 29% (n = 47) rated a symptom as highly interfering with their lives. Table 1 lists the frequencies of symptoms and severity at study entry and the 5-year visit are compared.

Figure 2.

Frequency of report of any cardinal post-EVD symptom following ETU discharge. Abbreviations: ETU, Ebola Treatment Unit; EVD, Ebola virus disease.

DISCUSSION

The large scale of the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa revealed that many, if not most, EVD survivors experience persistent health issues. In this cohort of Liberian EVD survivors, over three-quarters reported a post-EVD emergent symptom a median of 1 year following acute EVD and for more than 85%, the symptom highly interfered with life. Over a median of greater than 6 years of follow-up since acute EVD, there was a decline in self-report of most major post-EVD symptoms including fatigue, headache, hearing loss, visual disturbance, and musculoskeletal pain but not the neurologic complaints of numbness of the extremities. Although headache, fatigue, and joint pain were the most common post-EVD symptoms reported by survivors, more than half stated they had experienced numbness of the hands and/or feet. The trajectory of symptom severity largely mirrored symptom prevalence with a decrease in the odds of a symptom being rated as highly interfering with life, including for extremity numbness.

Although there was a decline in most, but not all cardinal symptoms, the burden of these post-EVD health problems persisted for many with over 50% reporting a symptom at 5 years of follow-up—almost a third with those that they reported highly interfered with their lives.

Several other studies conducted in this region in the aftermath of the outbreak have also characterized post-EVD symptomatology, as well as the persistence of these sequelae out to two years following initial infection [4–16]. Our findings are consistent with and build on those, including data from the PREVAIL-III study group, who reported reduced symptom burden including headache, fatigue, muscle pain, and joint pain in Liberian EVD survivors 1–2 years from infection [15].

Our observation of the persistence of peripheral neurological symptoms among EVD survivors, in contrast to the improvement seen in other symptoms, suggests differential pathogenesis of post-EVD sequelae. The etiology of post-EVD health issues remains unclear. Our group and others have assessed markers of inflammation and immune activation among Liberian EVD survivors and found no association between these and post-EVD symptoms [11, 16]. The persistence of Ebola virus RNA in the urogenital tract, central nervous system, and the eye support compartmentalization of virus following acute EVD [17–20]. It is posited that these reservoirs can be a source of antigen that can stimulate immune responses, perhaps triggering post-EVD symptoms [21]. The detection of EBOV RNA in semen of Liberian survivors was found to be associated with ocular symptoms or findings in our cohort and PREVAIL III [16, 17]. Recently, post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2) infection (PASC), or long-COVID, has been recognized as a common complication of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and there are data to support viral mediated neurological damage leading to lingering symptoms such as loss of smell and cognitive impairment [21–23]. The overlap between PASC and some post-EVD symptomatology raises the possibility of shared pathogenic mechanisms.

Our study has several strengths including long-term follow-up of over 300 EVD survivors with very low rates of loss to follow-up, careful inclusion of symptoms that developed following acute EVD (ie, were not pre-existing), and consistently applied measures of symptom assessment. Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. The cohort does not include controls without prior EVD; therefore, the prevalence of reported symptoms cannot be compared to background rates. Research we have conducted in Sierra Leone and that undertaken by the PREVAIL-III group in Liberia finds that EVD survivors are more likely than controls to experience these and related health issues [7, 16]. Furthermore, symptoms that have been most commonly reported in the literature as experienced by EVD survivors were targeted. We found most were prevalent in this cohort and although disturbances in vision and hearing were less common, they were highly consequential. Limited data detailing the symptoms that were prevalent earlier in the course of recovery from acute EVD were collected, as the median time from ETU discharge to study entry just over a year. This lag in symptom surveillance is found in most studies of EVD survivors, given the challenges in standing-up research during the outbreak. However, the longitudinal nature of this study and focus on symptoms that were not present prior to EVD provide an assessment of longer-term post-EVD symptomatology. Our assessments focused on physical symptoms and not those related to psychological distress. We previously described the burden of stigma cohort participants reported [24] and additional study of longer-term psychosocial stress is warranted and planned. Finally, the study relied on self-reported symptoms and self-rated severity, and we did not conduct formal assessments of functional impairment or objective examinations.

In conclusion, longer term observation of EVD survivors reveals a decline in the presence and severity of most of the common post-EVD symptoms. However, peripheral neurologic symptoms persist, and over half of survivors continue to experience symptoms years after their acute infection, often with significant impact on their lives. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the pathogenic mechanism of post-EVD symptoms so to develop therapeutic interventions to benefit current and future survivors.

Contributor Information

David Alain Wohl, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

William A Fischer, II, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Wenwen Mei, Department of Biostatistics, Gillings School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Fei Zou, Department of Biostatistics, Gillings School of Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Samuel Tozay, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Edwin Reeves, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Korto Pewu, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Jean Demarco, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

John Schieffelin, Section of Infectious Disease, Department of Pediatrics, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Henrietta Johnson, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Tonia Conneh, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Gerald Williams, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Darrius McMillian, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Jerry Brown, John F. Kennedy Memorial Medical Center, Monrovia, Liberia.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The research team is indebted to the staff at ELWA and Phebe hospitals including Drs John Fankhauser, Rick Sacra, Jefferson Sibley, and Uriah Glaybo for their support and dedicated care during and after the Ebola outbreak. They are also grateful to the many EVD survivors who are generously participating in this research and those who thoughtfully represent them.

Financial support. This study was supported by funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant number R01AI123535).

References

- 1. Malvy D, McElroy AK, de Clerck H, et al. Ebola virus disease. Lancet 2019; 393:936–48. Epub 2019 Feb 15. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 May 18; 393(10185):2038. PMID: 30777297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wing K, Oza S, Houlihan C, et al. Surviving Ebola: a historical cohort study of Ebola mortality and survival in Sierra Leone 2014–2015. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0209655. PMID: 30589913; PMCID: PMC6307710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leligdowicz A, Fischer WA 2nd, Uyeki TM, et al. Ebola virus disease and critical illness. Crit Care 2016; 20:217. PMID: 27468829; PMCID: PMC4965892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clark DV, Kibuuka H, Millard M, et al. Long-term sequelae after Ebola virus disease in Bundibugyo, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Epstein L, Wong KK, Kallen AJ, Uyeki TM. Post-Ebola signs and symptoms in U.S. Survivors. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2484–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Group PIS, Sneller MC, Reilly C, et al. A longitudinal study of Ebola sequelae in Liberia. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:924–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bond NG, Grant DS, Himmelfarb ST, et al. Post-Ebola syndrome presents with multiple overlapping symptom clusters: evidence from an ongoing cohort study in Eastern Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:1046–54. PMID: 33822010; PMCID: PMC8442780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mohammed H, Vandy AO, Stretch R, et al. Sequelae and other conditions in Ebola virus disease survivors, Sierra Leone, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nanyonga M, Saidu J, Ramsay A, Shindo N, Bausch DG. Sequelae of Ebola virus disease, Kenema District, Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:125–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qureshi AI, Chughtai M, Loua TO, et al. Study of Ebola virus disease survivors in Guinea. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1035–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rowe AK, Bertolli J, Khan AS, et al. Clinical, virologic, and immunologic follow-up of convalescent Ebola hemorrhagic fever patients and their household contacts, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Commission de Lutte contre les Epid.mies. Kikwit. J Infect Dis 1999; 179:S28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tiffany A, Vetter P, Mattia J, et al. Ebola virus disease complications as experienced by survivors in Sierra Leone. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1360–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson HW, Amo-Addae M, Kenu E, Ilesanmi OS, Ameme DK, Sackey SO. Post-Ebola syndrome among Ebola virus disease survivors in Montserrado County, Liberia 2016. Biomed Res Int 2018; 2018:1909410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de St. Maurice A, Ervin E, Orone R, et al. Care of Ebola survivors and factors associated with clinical sequelae–Monrovia, Liberia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. PREVAIL III Study Group, Sneller MC, Reilly C, et al. A longitudinal study of Ebola sequelae in Liberia. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:924–34. PMID: 30855742; PMCID: PMC6478393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tozay S, Fischer WA, Wohl DA, et al. Long-term complications of Ebola virus disease: prevalence and predictors of major symptoms and the role of inflammation. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1749–55. PMID: 31693114; PMCID: PMC7755089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varkey JB, Shantha JG, Crozier I, et al. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2423–7. Epub 2015/05/08. PubMed PMID: 25950269; PMCID: PMC4547451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jacobs M, Rodger A, Bell DJ, et al. Late Ebola virus relapse causing meningoencephalitis: a case report. Lancet 2016; 388:498–503. Epub 2016/05/23. PubMed PMID: 27209148; PMCID: PMC4967715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adaken C, Scott JT, Sharma R, et al. Ebola virus antibody decay-stimulation in a high proportion of survivors. Nature 2021; 590:468–72. Epub 2021/01/29. PubMed PMID: 33505020; PMCID: PMC7839293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischer WA, Brown J, Wohl DA, et al. Ebola virus ribonucleic acid detection in semen more than two years after resolution of acute Ebola virus infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4:ofx155. Epub 2018/04/20. PubMed PMID: 29670927; PMCID: PMC5897835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022; 185:881–895.e20. Epub 2022 Jan 25. PMID: 35216672; PMCID: PMC8786632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mehandru S, Merad M. Pathological sequelae of long-haul COVID. Nat Immunol 2022; 23:194–202. Epub 2022 Feb 1. PMID: 35105985; PMCID: PMC9127978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moghimi N, Di Napoli M, Biller J, et al. The neurological manifestations of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2021; 21:44. PMID: 34181102; PMCID: PMC8237541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Overholt L, Wohl DA, Fischer WA 2nd, et al. Stigma and Ebola survivorship in Liberia: results from a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0206595. PMID: 30485311; PMCID: PMC6261413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]