Abstract

Neuropathic pain is a leading cause of high-impact pain, is often disabling and is poorly managed by current therapeutics. Here we focused on a unique group of neuropathic pain patients undergoing thoracic vertebrectomy where the dorsal root ganglia is removed as part of the surgery allowing for molecular characterization and identification of mechanistic drivers of neuropathic pain independently of preclinical models. Our goal was to quantify whole transcriptome RNA abundances using RNA-seq in pain-associated human dorsal root ganglia from these patients, allowing comprehensive identification of molecular changes in these samples by contrasting them with non-pain-associated dorsal root ganglia.

We sequenced 70 human dorsal root ganglia, and among these 50 met inclusion criteria for sufficient neuronal mRNA signal for downstream analysis.

Our expression analysis revealed profound sex differences in differentially expressed genes including increase of IL1B, TNF, CXCL14 and OSM in male and CCL1, CCL21, PENK and TLR3 in female dorsal root ganglia associated with neuropathic pain. Coexpression modules revealed enrichment in members of JUN-FOS signalling in males and centromere protein coding genes in females. Neuro-immune signalling pathways revealed distinct cytokine signalling pathways associated with neuropathic pain in males (OSM, LIF, SOCS1) and females (CCL1, CCL19, CCL21). We validated cellular expression profiles of a subset of these findings using RNAscope in situ hybridization.

Our findings give direct support for sex differences in underlying mechanisms of neuropathic pain in patient populations.

Keywords: pain, neuropathy, dorsal root ganglia, pain transcriptomics, transcriptome-wide association study

Using RNA sequencing on DRG samples from more than 50 patients undergoing thoracic vertebrectomy, Ray et al. uncover sex differences in mechanistic drivers of neuropathic pain. Pain was associated with changes in gene expression in inflammatory cytokine signalling pathways in males and interferon signalling pathways in females.

Introduction

Neuropathic pain affects millions of US adults, is a primary cause of high-impact chronic pain and is poorly treated by available therapeutics.1–3 Preclinical studies in rodents have identified important roles of neuronal plasticity4,5 and neuro-immune interactions6,7 in neuropathic pain, but molecular and anatomical differences between rodent models and humans8–14 suggest that the (diverse) biological processes involved in the chronification and maintenance of human pain remain ill-understood, and therapeutics based on rodent models have faced serious translational challenges.15,16 Molecular mechanisms of neuropathic pain in patients need to be understood and putative drug targets identified in order to develop the therapeutics that can meet this medical challenge.

Here we have built upon our work with patients undergoing thoracic vertebrectomy surgery, which often involves removal of dorsal root ganglia (DRGs).17 This provides an opportunity to identify neuropathic pain in specific dermatomes prior to surgery, allowing comparison of DRGs associated with neuropathic pain to those without. Our goal was to quantify whole-transcriptome RNA abundances using RNA-seq in pain-associated DRGs to comprehensively identify differences in RNA profiles linked to the presence of neuropathic pain in male and female patients. Our previous work demonstrated transcriptomic differences in human DRG (hDRG) associated with neuropathic pain, but our sample size was insufficient to reach direct conclusions about sex differences in underlying neuropathic pain mechanisms.17 Given the overwhelming evidence for such differences in preclinical neuropathic pain models,18–23 we hypothesized that an increased sample size would give us the ability to detect clear differential expression of neuro-immune drivers of neuropathic pain in this patient population.

In this study, we conducted a sex-stratified transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS), followed by coexpression module analysis of neuropathic pain-associated genes on 50 hDRGs from neuropathic pain patients. Our analysis reveals clear sex differences in sets of genes associated with neuropathic pain in men and women. These gene products are prominently involved in neuro-immune signalling and neuronal plasticity. We validated the cell type expression for a subset of these genes in males and females with RNAscope in situ hybridization, finding changes in neurons and putative macrophages in both sexes. Our findings paint a picture of neuro-immune signalling that likely drives neuropathic pain in this patient population, giving insight into future therapeutic development for neuropathic pain.

Materials and methods

Consent, tissue and patient data collection

All protocols were reviewed and approved by the UT Dallas (UTD) and MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) Institutional Review Boards. All protocols and experiments conform to relevant guidelines and regulations, in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients undergoing thoracic vertebrectomy at MDACC for malignant tumours involving the spine were recruited as part of the study. Informed consent for participation was obtained for each patient during study enrolment.

All donors were undergoing surgery which required ligation of spinal nerve roots for spinal reconstruction or tumour resection. Tissue extraction and patient data collection was performed as described in North et al.17 The DRG were partitioned into three or four sections (typically quartered) immediately outside the operating room. In short, spinal roots were cut, the ganglia immediately transferred to cold (∼4°C) and Earle’s sterile balanced salt solution (Thermo Fisher Cat. No. 14155-063), taken to the laboratory and cleaned. One section, usually a quarter of the DRG, was frozen in RNA later and shipped on dry ice to UTD for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

Data (including demographics, clinical symptoms and medical history) were obtained from consented patients at MDACC through retrospective review of medical records and prospective data collection during study enrolment. Neuropathic pain was defined as a binary clinical variable for purposes of reporting consistency. The presence or absence of neuropathic or radicular pain for each dermatome was performed in a manner consistent with the guidelines for (definite or probable) neuropathic pain from Assessment Committee of the Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group of International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).24,25 A harvested hDRG was determined to be associated with neuropathic or radicular pain if the patient had documented spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia or allodynia in a region at or within two classically defined dermatomes of the harvested ganglion in question and was considered not to be associated with neuropathic pain if not (or if the harvested ganglion was from the side contralateral to reported pain in a patient with only unilateral symptoms). Remaining scenarios were categorized as inconclusive. All pain reports dated back at least 1 month, with one exception (66T12R). Most subjects were cancer patients treated with chemotherapeutics, but the DRGs collected and analysed did not have any signs of tumour and only a few were associated with dermatomes affected by length-dependent neuropathy. De-identified patient data, including demographics, nature of pain, spinal level of the DRG and usage of drug treatment history, for the entire cohort can be found in Table 1 (with additional details in Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Relevant demographic, clinical and medical history variables of de-identified patients

| Patient ID: sample ID/spinal level (pain state)a | Age, race (sex)b | Primary tumour (prior chemotherapy/systemic treatments) | Neuropathic/radicular symptom length (VAS at maximal intensity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21: T3L (P), T6L (P) | 59, W (M) | Metastatic chordoma (N) | >1 mo, <6 mo (6.0) |

| 22: T10L (N), T10R(P) | 61, O (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (N) | >6 mo, <12 mo (6.0) |

| 23: T2L (P), T2R (P) | 57, W (F) | Non-small cell lung carcinoma (N) | >1 mo, <6 mo (NA) |

| 24: T2R (P) | 70, B (M) | Adenoid cystic carcinoma (N) | >12 mo (8.1) |

| 25: T12R (N) | 60, W (F) | Endometrial carcinoma (Y: carboplatin/doxorubicin, cisplatin/gemcitabine) | NA (6.7) |

| 26: T3R (P), T4R (P) | 55, W (M) | Non-small cell lung carcinoma (Y: cisplatin/taxol) | >6 mo, <12 mo (8.4) |

| 29: T8R (N) | 79, B (M) | Dedifferentiated sarcoma (N) | >12 mo (1.9) |

| 30: T3R (P) | 70, O (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (Y: sunitinib) | >12 mo (6.5) |

| 31: T7L (P), T7R (P) | 66, W (M) | Chondrosarcoma (N) | >12 mo (9.7) |

| 32: T5R (P) | 66, B (F) | Non-small cell lung carcinoma (N) | >1 mo, <6 mo (8.6) |

| 33: T3R (U), T4R (U) | 42, W (F) | Breast carcinoma (Y: docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab, adotrastuzumab emtansine, alpelisib) | >1 mo (6.9) |

| 34: T5R (P), T6R (P) | 41, AI (M) | Fibrous dysplasia (N) | >12 mo (6.2) |

| 35: T10L (P), T10R(N) | 64, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (N) | >6 mo, <12 mo (4.7) |

| 37: T2R (P) | 73, O (F) | Renal cell carcinoma (Y: pazopanib, nivolumab) | >1 mo, <6 mo (9.4) |

| 38: T7L (P), T7R (P) | 63, U (F) | Metastatic melanoma (N) | >1 mo, <6 mo (8.6) |

| 39: T8L (N), T8R (P) | 59, AI (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (N) | >1 mo, <6 mo (8.7) |

| 40: T4L (P) | 59, W (M) | Non-small cell lung carcinoma (N) | NA (10) |

| 41: T7R (P) | 55, W (F) | Adenocarcinoma (N) | >6 mo, <12 mo (10) |

| 42: T7L (P), T7R (P) | 64, W (F) | Leiomyosarcoma (Y: docetaxel, gemcitabine) | NA (4.5) |

| 44: T10R (N), T11L (N), T11R (N) | 56, W (M) | Metastatic melanoma (Y: TIP-287 (taxane), cisplatin, ipilumumab, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, pazopanib) | NA (7.1) |

| 45: T10L (N), T11R (P) | 68, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (Y: nivolumab, cabozanitinib) | NA (9.7) |

| 46: T8R (P) | 60, W (F) | Renal cell carcinoma (Y: pazopanib) | NA (8.8) |

| 47: T7L (P), T7R (P) | 65, W (M) | Multiple myeloma (Y: bortezomib, Cyp, pamlid/thalid/lenalidomide) | >1 mo, <6 mo (8.2) |

| 61: T5L (N), T5R (N) | 37, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma (Y: pazopanib, nivolumab, everlimus, tremelimumab) | NA (7.3) |

| 64: T7L (P), T7R (U), T8R (U) | 71, W (M) | Prostate carcinoma (Y: cabazitaxel, abiraterone, docetaxel/carboplatin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel) | >6 mo, <12 mo (9.9) |

| 66: T12L (N), T12R (P) | 50, W (M) | Colon carcinoma (Y: FOLFOX, iriniteca/erbitux, vectibix) | <1 mo (9.9) |

| 67: T4L (N), T4R (N) | 65, W (F) | Breast carcinoma (N) | NA (8.6) |

| 69: T10L (N) | 65, A (F) | Hepatocellular carcinoma (N) | NA (8.2) |

| 71: T7L (P), T7R (P) | 65, O (F) | Cholangiocarcinoma (gemcitabine/cisplatin) | >3 mo (9.7) |

| 80: T2R (N) | 68, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma pazopanib, nivolumab/ipilimumab | NA (9.9) |

| 81: T5R (P), T6R (P) | 33, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma: pembolizumab | >3 mo (8.1) |

| 83: T8R (P) | 58, W (M) | Malignant melanoma:immunotherapy | 3 mo (9.4) |

| 84: T4L (P), T5L (P) | 56, W (M) | Renal cell carcinoma:immunotherapy | 3 mo (6.8) |

| 85: T3L (P), T3R (P), T5L (P), T5R (P) | 39, W (F) | Colon carcinoma (NA) | 3 mo (9.5) |

| 86: T6R (P), T7R (P) | 40, B (F) | Chondrosarcoma (N) | 24 mo (8.6) |

| 87: T5L (N) | 55, B (M) | Colon carcinoma (Y: irinotecan/cetuximab) | NA (8.9) |

| 88: T10R (P) | 72,W (M) | Hurthle cell thyroid carcinoma (Y: radio-iodine 200) | 1 mo (8.7) |

| 89: T6L (N), T6R (N) | 63, W (F) | Unknown (N) | NA (5.8) |

| 90: T8R (N) | 59, W (M) | Ewing’s sarcoma (vincristine, doxirubicin, ifosfamide; etopisde, ifosfamide) | >3 mo (7.9) |

| 91: T4L (P), T4R (P), T5L (P) | 77, W (M) | Prostate carcinoma (bicalutamide, leuprolide) | >3 mo (9.1) |

| AIDC-291: T12U (N) | 34, W (M) | Cause of death: CVA/stroke (N) | NA (NA) |

mo = months; VAS = visual analogue scale.

Level: L = left; R = right; T = thoracic; U = unknown. Pain state: N = no pain; P = pain; U = undetermined—in sample-associated dermatome.

Race: A = Asian; AI = American Indian; B = Black; O = Other; W = White. Sex: F = female; M = male.

RNA-seq library preparation, mapping and abundance quantification

Total RNA from each DRG sample were purified using TRIzol™ and depleted of ribosomal RNA. RNA integrity was assessed and Illumina Tru-seq library preparation protocol was used to generate cDNA libraries according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Single-end sequencing of each library was performed in multiplexed fashion across several batches as samples became available on the Illumina Hi-Seq sequencing platform. Sequenced reads were trimmed to avoid compositional bias and lower sequencing quality at either end and to ensure all quantified libraries were mapped with the same read length (38 bp), and mapped to the GENCODE reference transcriptome (v27)26 in a strand-aware and splicing-aware fashion using the STAR alignment tool.27 Stringtie28 was used to generate relative abundances in transcripts per million (TPM) and non-mitochondrial coding gene abundances were extracted and renormalized to a million to generate coding TPMs for each sample (Supplementary Table 2A).

In our previous study,17 we noted variation in the proportion of neuronal mRNA content per sample, likely caused primarily by technical factors (what proportion of the neuronal cell bodies and axon, as opposed to myelin, perineurium and epineurium are sampled in each quartered DRG, and the amount of viable mRNA extracted from these). With the number of samples increasing almost 4-fold in our present study, we identified a greater spread in neuronal mRNA content across samples. Irrespective of whether such variation is due to biological or technical causes, TWAS would be confounded by decreased neuronal mRNA proportion in a subset of samples (which would likely contribute to both within-group and between-group variation, when grouped by pain state). Thus, samples that show moderate or strong reduction in neuronal mRNA proportion were excluded from downstream analysis.

Based on a panel of 32 genes that are known neuronal markers (like RBFOX3) or DRG-enriched in human gene expression,13 and further validated to be enriched in neuron-proximal barcodes in Visium spatial sequencing for hDRG,11 we tabulated the relative abundance (in TPM) of these genes in each of our samples (Supplementary Table 2B). Quantiles were calculated across samples for each gene, and a subset of the samples showed low quantiles for the vast majority of the genes in the gene panel, suggesting that the low gene expression was not the result of downregulation but systematic reduction in the proportion of neuronal mRNAs. The neuronally enriched mRNA panel index for each sample was calculated as a median of the per-gene quantile value (median calculated across genes in the gene panel). Based on the neuronally enriched mRNA panel index (ranges for the index for each group shown in Supplementary Table 2B), we grouped the samples into two groups: samples with moderately or strongly reduced proportion of neuronal mRNA and samples with a higher proportion of neuronal mRNA. Of 70 samples, 51 RNA abundance profiles with higher neuronal mRNA content were retained for downstream analysis. We also found that the neuronally enriched mRNA panel index was correlated with the expression profile of 1239 genes (Pearson’s R > 0.55, uncorrected P-value < 0.00005), many of which are known to be neuronally enriched in the hDRG (Supplementary Table 2C). Gene TPMs for these 51 samples are presented in Supplementary Table 2D. Of these, the dermatome of one sample (64T8R) could not be conclusively placed into pain or no pain categories, so this sample was also not used for downstream analysis. All of our samples used for downstream analysis had an adequate (>40 million) number of uniquely mapped reads, as shown in Supplementary Table 1, and have adequate library complexity (>12 000 genes detected; Supplementary Table 2D).

Finally, in order to standardize TPM distributions across samples, we performed two quantile normalizations—for samples with >15 500 genes detected and for samples with 13 400–14 100 genes detected (25T12R and 30T3R). We reset the abundances for genes with zero counts to zero after quantile normalization. Quantile normalization caused the TPM distribution across samples to be similar to each other, reducing variance from technical factors like sequencing depth, especially for higher quantiles (0.33 or higher). Quantile-normalized TPMs are presented in Supplementary Table 2E.

TWAS with neuropathic pain

We stratified the sample set by sex. Our analysis identifies sample-level TWAS between the digital readouts of relative abundances of coding genes, with the binary variable representing dermatome-associated pain. In experiments on rodent models with identical genetic landscapes, and consistent insult or injury models defining groups, a straightforward way to perform TWAS is to directly perform differential expression analysis (with sex as a batch or partitioning variable).29 Such a straightforward approach is unlikely to work in real-world human transcriptome data sets for a variety of reasons. Gene expression of pain-associated genes are likely to occupy a spectrum, due to the fact that there are some differences in pathologies and cell type proportions from sample to sample, as well as differences in genetic landscape and variations in medical and clinical history from patient to patient. The heterogeneous nature of neuropathic pain suggests multiple molecular mechanisms, some of which may be post-transcriptional and thus not be detectable by sampling steady-state transcriptomes. Further, a few of the DRGs not associated with pain could also show pain-like molecular signatures due to the fact that proximal mammalian dermatomes can overlap.30

Thus, instead of a traditional differential expression (DE) analysis, we identify distributional shifts in abundance between pain and non-pain samples, in a sex-stratified fashion. For each of the sexes, we contrasted gene expression between the pain and non-pain subcohorts. Such an approach accounts not just for changes in the mean or median, but also for changes in variance in the disease state,31 a potential confounding effect in such studies.

As our libraries were constructed from total RNA, we removed from downstream analysis genes that did not have a validated peptide sequence, fusion genes or families that have large numbers of pseudogenes like olfactory receptors,32 even though they may be predicted as coding genes in the reference annotation. To ensure consistently detectable genes with lower sampling variance, we constrained our analysis to genes with TPMs >0.5 qnTPM (quantile-normalized TPM) at the median (50th percentile), and >1.0 qnTPM at the upper quartile (75th percentile) for the subcohort that was tested for increased gene expression (rounded to one decimal place).

In our previous experience in analysing sex-differential RNA-seq expression in large human cohorts,33 we found that the most distinct differences occurred between the median and upper quartile (75th percentile). Here, we identified distributional shifts in gene abundance between the pain and non-pain subcohorts in each sex by comparing order statistics between the 20th and 80th percentiles (to partially mitigate the effects of outliers). We constrained that the directionality of change in abundance (increase or decrease in pain versus non-pain subcohorts) had to be consistent between the median, upper quartile and the maximum analyaed quantile (80th percentile)—which might suggest consistency with a phenotype or degree of pathology. We then selected for genes with the largest changes in abundance between pain states by filtering out genes with median fold change <1.5, or with a maximum fold change in the top two quartiles <2.0 (up to a rounding error in the fold change of one decimal point). A smoothing factor of 0.1 TPM was added to both the numerator and denominator to calculate fold changes. Finally, to identify genes with maximal distributional shift, we filtered based on two metrics. First, to identify genes with the largest difference in values for the same quantiles, we constrained the gene set to genes with area between the quantiles of the distributions (between the pain and non-pain subcohorts of one sex) >5% of the total area of the quantile plot. The approximate normalized signed area between the quantile curves was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where Q−1 is the inverse quantile function, FP, s and FNP, s are the empirically estimated distributions for the pain and non-pain subcohorts, respectively, for the sex s in question, and q changes from qmin (0.2) to qmax (0.8) in steps of 0.025 (qstep). Then, to identify genes with the largest difference in quantiles for the same values, we calculated the shift in quantiles for each of the three quartiles in the distribution of a subcohort and summed them, and filtered out genes with a negative sum:

| (2) |

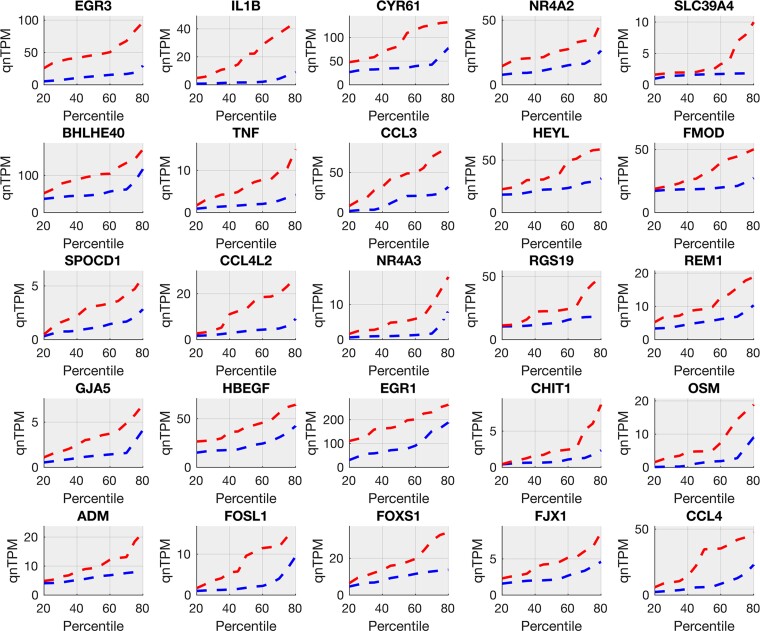

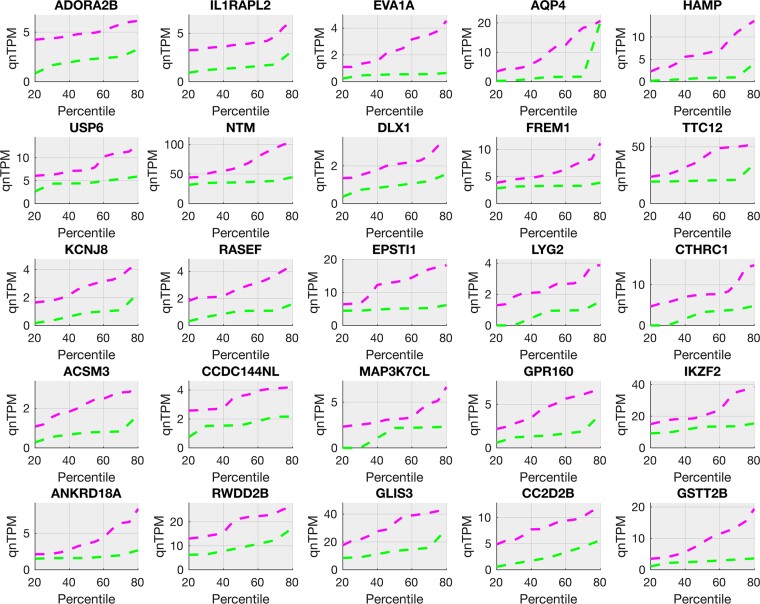

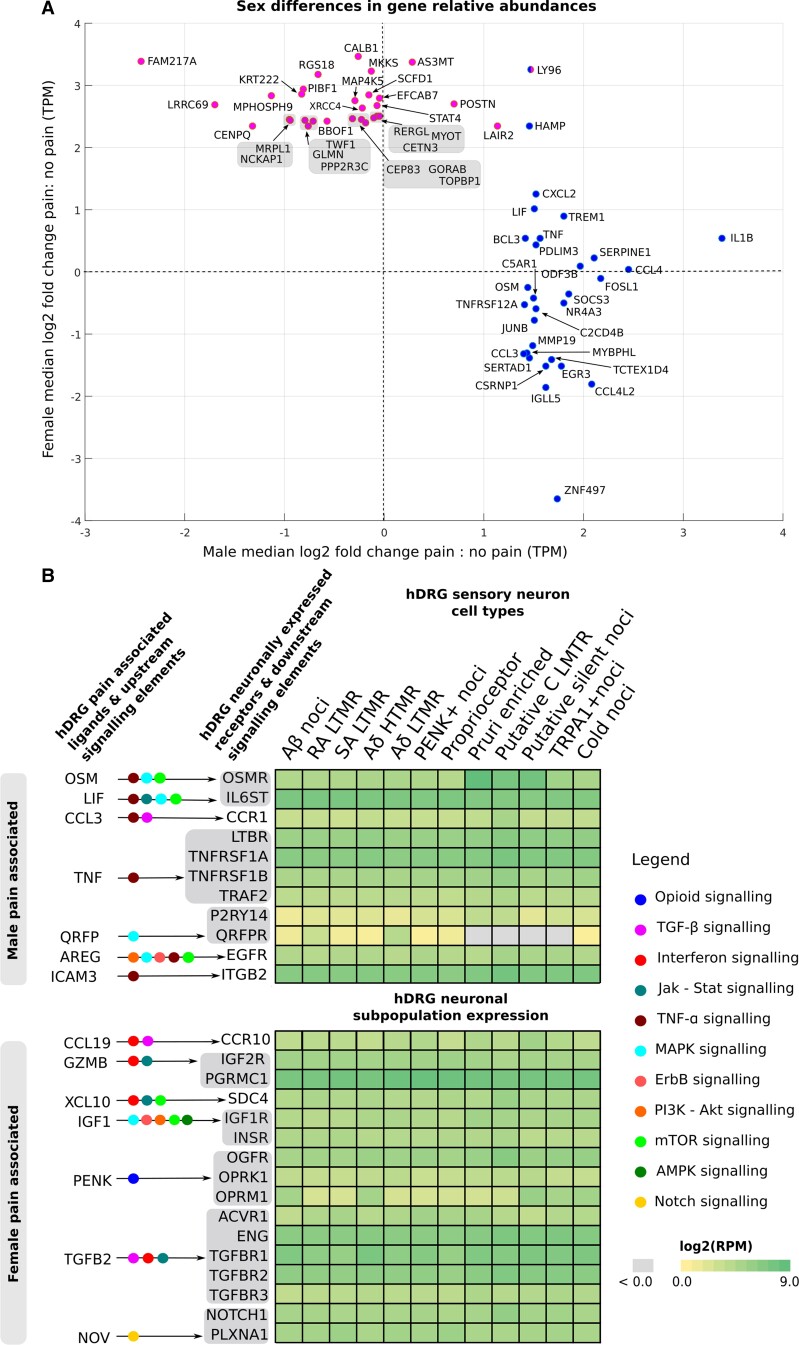

where Q is the quantile function, Q−1 is the inverse quantile function, FP, s and FNP, s are the empirically estimated distributions for the pain and non-pain subcohorts, respectively, for the sex s in question. For the filtering criteria in genes that are increased in non-pain cohorts with respect to pain cohorts for males or females, FP, s and FNP, s are interchanged in the formulae. The genes that were increased in the pain and non-pain cohorts for each sex are presented in Supplementary Table 3A–D. We refer to the genes that are increased or decreased in abundance in the pain cohorts as pain-associated genes. Quantile curves (quantile versus value) were plotted for each of the top 25 pain-associated genes increased in the pain state (ranked by the area between the quantile curves of each pain state) in males and females are shown in Figs 1 and 2, respectively. Median fold changes in TPM (between pain and no-pain states) of the top 25 pain-associated genes in males and females are compared in Fig. 3A, and pain-associated ligands that signal to neuronal gene products are displayed in Fig. 3B. Protein interaction networks based on male and female pain-associated genes are shown in Supplementary Figs 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Top 25 pain-associated genes in the male cohort (increased in pain). Pain-associated genes in male samples (Supplementary Table 3A) show systematic increases in pain. Quantile plots (quantile versus value) for gene relative abundances (in TPMs) for the top 25 genes are shown in male pain samples (in red, upper line) and male no-pain samples (in blue, lower line). These include multiple members of AP-1 signalling (EGR3, FOSL1), pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL1B, CCL3, CCL4), TNF signalling (TNF, IL1B) and other transcriptional regulators (NR4A2, FOXS1, HBEGF) relevant to the peripheral nervous system and pain.

Figure 2.

Top 25 pain-associated genes in the female cohort (increased in pain). Pain-associated genes in female samples (Supplementary Table 3C) show systematic increases in pain. Quantile plots (quantile versus value) for gene relative abundances (in TPMs) in the top 25 genes are shown in female pain samples (in magenta, upper line) and female no-pain samples (in green, lower line). These include multiple members of receptor genes (ADORA2B, IL1RAPL2, GPR160), pro-inflammatory and proliferation-related genes (HAMP, FREM1), vesicular trafficking genes (LYG2, RASEF) and interferon-response genes (USP6, TTC12).

Figure 3.

Sex differential aspects of the pain-associated transcriptome. (A) The top 25 pain-associated genes (Supplementary Table 3A and C) increased in pain (with a median fold change of 2-fold or higher) for each sex show a remarkably sex-differential signal, with only HAMP showing 2-fold or greater change in the median in both sexes among the top 25. Log2 fold changes in the median between pain and no-pain subcohorts are shown for males and females as a scatter plot, with male pain-associated genes shown in blue (right cluster) and female pain-associated genes shown in pink (left cluster). LY96 is present in both male and female lists. (B) Pain-associated ligands in each sex signal to hDRG-expressed receptors that are enriched in sensory neuronal subpopulations,11 but have little overlap across sexes. Based on our interactome analysis, we show such ligand–receptor pairs, alongside receptor expression in human DRG neuronal subtypes11 as a heatmap. Overlap with relevant signalling pathways are also shown. Male signalling is enriched in TNF-alpha pathway, while female signalling is enriched in interferon signalling. Although ICAM3 (in males) and TGFB2 or NOV (in females) are not in the pain-associated gene lists, they are increased in pain for the corresponding sex at the median or upper quartile levels and are thus shown here.

Additionally, for four male patients with unilateral pain (22, 35, 39 and 66), we have ipsilateral and contralateral DRG samples. These samples lend themselves to a classical paired DE analysis with paired fold changes, as medical and clinical history as well as genetic background is consistent across each pair and were found to be consistent in terms of the genes upregulated in the pain samples. Genes whose median log fold change across the four pairs were 2-fold or greater are presented in Supplementary Table 3E and F. We limited our analysis to highly expressed genes—more than two (of four) of the samples in the group being tested for increased gene expression were required to have qnTPM >2.0.

Analogous analysis was also performed to identify gene expression changes in male pain samples from patients using length-dependent peripheral neuropathy (LDPN)-causing chemotherapeutic agents versus patients who were not (Supplementary Table 3G and Supplementary Fig. 3). As with oncologic disease type, preoperative medication use may influence pathways that promote neuropathic pain generation and propagation. Short- and long-term use of opiates and neuropathic pain agents can influence patients’ neuropathic pain phenotype, and certain chemotherapeutic agents (platinum agents, taxanes, vinca alkaloids) can contribute to the development of LDPN. To address this question, we attempted sex-stratified subanalyses to identify differential gene expression profiles in patients with neuropathic pain according to preoperative medical therapy. While insufficient treatment information was available for suitably analysing opiate use, we were able to evaluate the impact of LDPN-inducing chemotherapeutic agents on gene expression in a small subcohort. We identified patients with neuropathic pain and preoperative use of taxanes, vinca-alkaloids and platinum agents. Of note, we excluded patients with a documented history of distal symmetric ascending peripheral neuropathy (including diabetic peripheral neuropathy or unspecified aetiology). We identified three male samples that fit these criteria, and we performed a DE analysis comparing them to the cohort of males with neuropathic pain who did not use LDPN-inducing chemotherapeutic agents preoperatively (15 samples). We did not perform an analogous comparison in females due to sample size limitations.

Coexpression module analysis

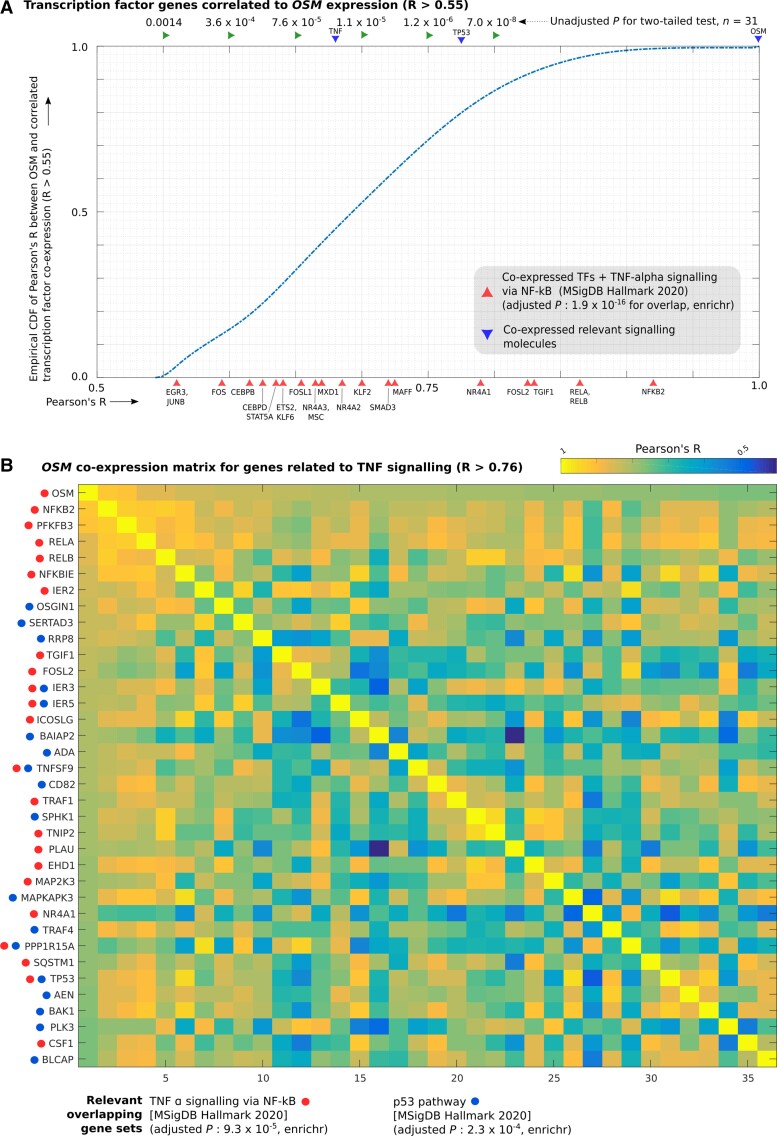

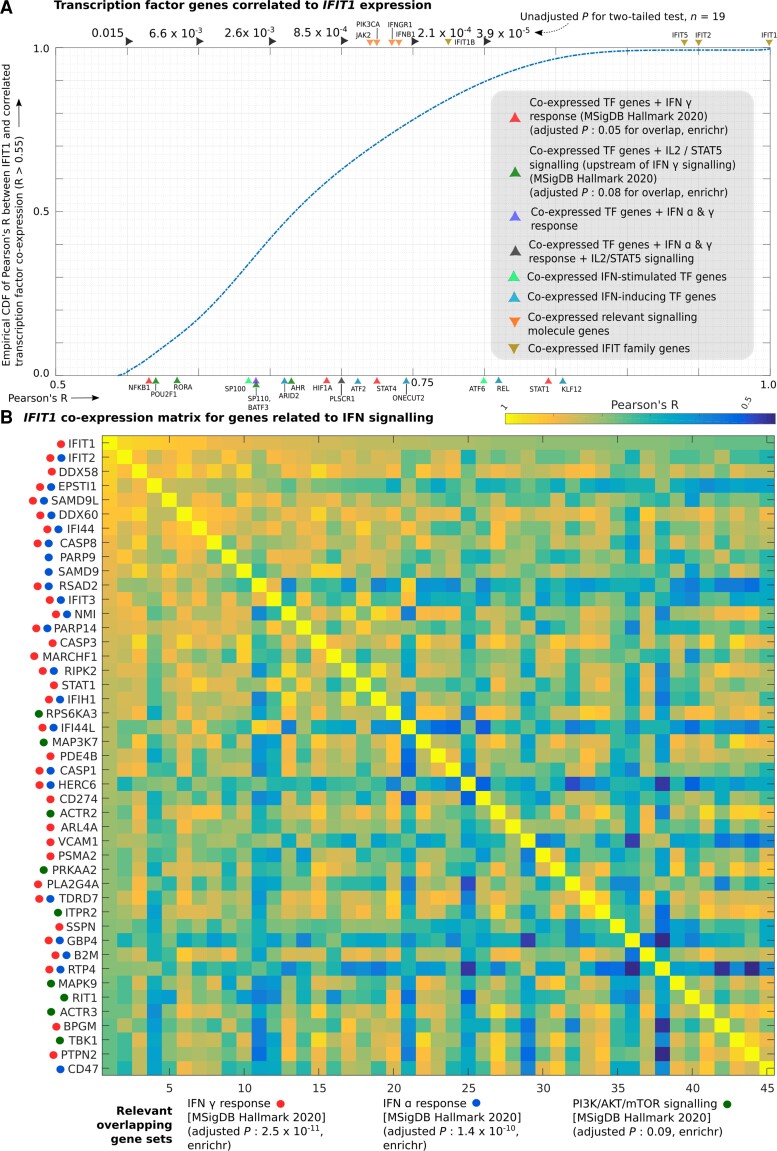

In order to identify transcriptional programmes that may drive changes in gene abundance or identity of cell types where these pain-associated genes were expressed, we identified coexpression modules (based on qnTPM) for genes that were increased in pain or no-pain cohorts, for each sex. Pearson’s R was calculated for each pain-associated gene in the relevant sex, and genes with a statistically significant Pearson’s R that were highly expressed (median qnTPM > 2.0) in the sex-stratified subcohort where the coexpression module was increased in abundance were retained as members of the module. There were several coexpression modules with >100 genes, but in our study, we focused on two large coexpression modules (gene coexpressing with OSM in males and with IFIT1 in females) that showed statistically significant Pearson’s R and enrichment for well-known signalling pathways. Further, transcriptional regulators that are part of these modules were also profiled in order to better understand the transcriptional identity of the cells where these genes were expressed and the potential regulatory cascades that may be implicated. Figure 4A and B and Supplementary Table 3H and I show transcription factor genes (R > 0.55) and all genes (R > 0.76) that were coexpressed with OSM, respectively. Fig. 5A and B and Supplementary Table 3J and K show transcription factor genes (R > 0.55) and all genes (R > 0.76) that were coexpressed with IFIT1, respectively.

Figure 4.

OSM coexpression module. Coexpression of individual genes with OSM in male samples was quantified using Pearson’s correlation (Pearson’s R). (A) Empirical cumulative distribution function (CDF) of Pearson’s R (with OSM expression) for transcription factor genes with Pearson’s R > 0.55, overlaid with Pearson’s R for genes of key signalling molecules in the TNF-alpha pathway (TNF, TP53 and OSM) and IL32 (another pro-inflammatory cytokine) and members of enriched gene sets that overlap with the coexpressed TF genes are also shown. (B) Heatmap of correlation matrix (Pearson’s R) between members of OSM coexpression module in enriched gene sets (TNF signalling via NFKB, p53 signalling) that overlap with it. Rows and columns of the correlation matrix have the same genes, with the diagonal showing perfect correlation (R = 1).

Figure 5.

IFIT1 coexpression module. Coexpression of individual genes with IFIT1 in female samples was quantified using Pearson’s correlation (Pearson’s R). (A) Empirical cumulative distribution function (CDF) of Pearson’s R (with IFIT1 expression) for transcription factor genes with Pearson’s R > 0.55, overlaid with Pearson’s R for genes of key signalling molecules in the interferon signalling pathways and members of enriched gene sets that overlap with the coexpressed TF genes are also shown. (B) Heatmap of correlation matrix (Pearson’s R) between members of IFIT1 coexpression module in enriched gene sets (interferon alpha and gamma response, respectively; PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling) that overlap with it. Rows and columns of the matrix have the same genes, with the diagonal showing perfect correlation (Pearson’s R = 1).

The thresholds for Pearson’s R chosen in the male and female cohorts were as follows: R > 0.76 for whole-transcriptome correlation corresponds to P-value < 7.1 × 10−7 in males (n = 31) and to P-value < 1.6 × 10−4 in females (n = 19) for a two-tailed test. We chose a less-stringent threshold for identifying coexpressed transcription factor (TF) genes, as <1000 TFs are expressed in most cell types (as opposed to ∼10 000 coding genes for the whole transcriptome). R > 0.55 for TF coexpression analysis corresponds to P-value < 6.7 × 10−4 in males (n = 31) and to P-value < 7.3 × 10−3 in females (n = 19) for a two-tailed test. For each gene in the coexpression module, 80% of the samples were randomly sampled repeatedly (n = 20), and small (0.01) values were randomly added or subtracted to each element of the vector to ensure that randomly detected low expression or outlier samples were not driving the correlation.

Functional annotation and overlap analysis

The list of transcription factors was obtained from literature34 and signalling pathway gene sets were obtained from the MSigDB Hallmark database.35 Gene set enrichment analysis was performed with Enrichr.36 We identified potential protein interaction using STRINGdb.37 We used products of pain-associated genes that were increased in pain, genes of the profiled coexpression modules and hDRG-expressed genes13 that are known to interact with them to seed the network, using only linkages with medium or higher confidence, for gene product pairs with known molecular interaction or coexpression.

RNAscope assay

Based on our findings from the RNA-seq analysis, we decided to validate the gene expression of identified pain-associated genes and putatively identify their cell types of expression using RNAscope in situ hybridization assay. We chose two pain-associated samples and one non-pain sample for each sex for performing RNAscope. Because RNA-seq is a destructive method, RNAscope was performed on a different piece of the same harvested DRG sample (from which the RNA-seq was conducted) that had been previously banked.

Given the limited availability of banked fresh-frozen hDRG sections, we used the following tissues in our RNAscope experiments: Male 84T4L (pain; thoracic 4 left), male 91T5L (pain; thoracic 5 left), female 85T3L (pain; thoracic 3 left), female 86T6R (pain; thoracic 6 right), female 89T6R (non-pain; thoracic 6 right). We identified the banked tissues for pain samples where one or more of these genes were significantly increased with respect to the non-pain samples (using our RNA-seq analysis). We had no banked fresh frozen non-pain thoracic hDRG samples collected from vertebrectomy patients, so we used a thoracic-12 hDRG from a non-pain organ donor (AIDC291) acquired through our collaboration with the Southwest Transplant Alliance, recovered from an organ donor with no history of neuropathic pain (Table 1). Thus, this sample does not have a corresponding RNA-seq assay.

RNAscope in situ hybridization multiplex version 2 on fresh frozen tissue was performed as instructed by Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD). A 2-min protease IV digestion was used for all experiments and fluorescin β, Cy3 and Cy5 dyes (Akoya) were used in lieu of Opal dyes. The probes used were: OSM (ACD Cat. 456381), IL1B (ACD Cat. 310361), TNF (ACD Cat. 310421), IL32 (ACD Cat. 541431-C2), IFIT1 (ACD Cat. 415551), AIF1 (ACD Cat. 433121-C3), HLA-DQB1-O1 (ACD Cat. 527021-C2), TRPV1 (ACD Cat. 415381-C1, C2) (Figs 6 and7). All tissues were checked for RNA quality by using a positive control probe cocktail (ACD Cat. 320861), which contains probes for high-, medium- and low-expressing mRNAs that are present in all cells (ubiquitin C > peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase B > DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB1). All tissues showed robust signal for all three positive control probes. A negative control probe (ACD Cat. 320871) against the bacterial DapB gene (ACD) was used to check for non-specific/background label (Supplementary Figs 4 and 5 for female and male controls respectively). Images (×40) were acquired on an FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus). The acquisition parameters were set based on guidelines for the FV3000 provided by Olympus.

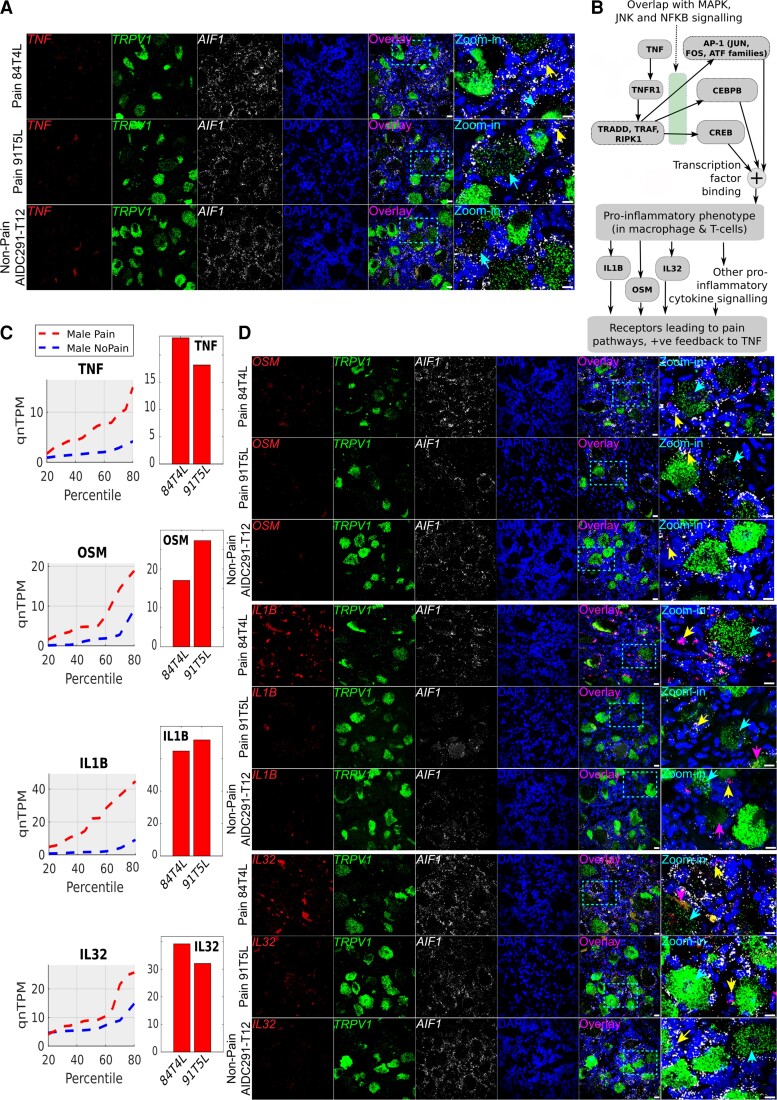

Figure 6.

RNAscope for male pain-associated genes TNF, OSM, IL1B and IL32. (A) RNAscope TNF expression (red) overlaid with TRPV1 expression (green), AIF1 (white) and DAPI (blue) in pseudocolour. (B) Schema showing how TNF-alpha signalling cascades overlap with other signalling pathways, based on existing literature (icons from BioRender). (C) TNF, OSM, IL1B and IL32 quantile plots show the shift in abundance between male pain and non-pain subcohorts, while the bar plots show the RNA-seq abundance for the patient DRGs that were queried by RNAscope assay. (D) RNAscope OSM, IL1B and IL32 expression (red) overlaid with TRPV1 expression (green), AIF1 (white) and DAPI (blue) in pseudocolour. Scale bar = 20 μm, large globular structures are considered to be lipofuscin. Yellow arrows point out cells with overlap of expression between the gene of interest (red) and AIF1 (white), cyan arrows point out overlap of expression between the gene of interest (red) and TRPV1 (green), respectively, in the zoomed-in images, and pink arrows point to lipofuscin. (A and D) In all micrographs, wide field views and zoomed-in views on single neurons and surrounding cells are shown to display overall signal distribution, and colocalization of signal with specific neuronal and macrophage cell markers for each RNAscope probe.

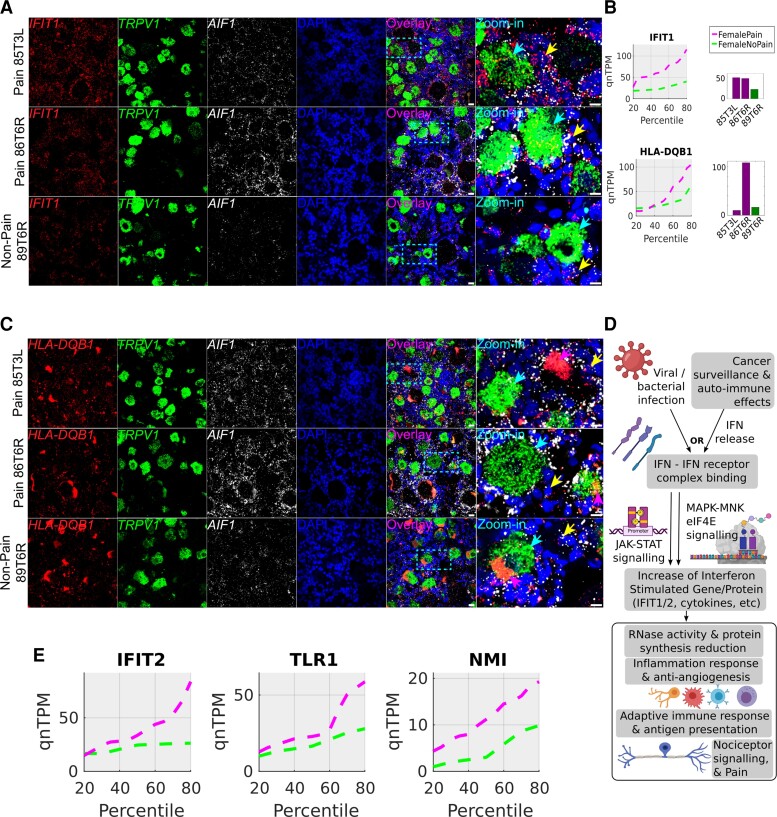

Figure 7.

RNAscope for female pain-associated genes IFIT1 and HLA-DQB1. (A) RNAscope IFIT1 expression (red) overlaid with TRPV1 expression (green), AIF1 (white) and DAPI (blue) in pseudocolour. (B) IFIT1 and HLA-DQB1 quantile plots show the shift in abundance between female pain and non-pain subcohorts, while the bar plots show the RNA-seq abundance for the patient DRGs that were queried by RNAscope assay. (C) RNAscope HLA-DQB1 expression (red) overlaid with TRPV1 expression (green), AIF1 (white) and DAPI (blue) in pseudocolour. (D) Schema showing how interferons are typically activated and drive a signalling programme, based on existing literature (icons from BioRender). (E) Quantile plots in the female cohort for other IFIT1-correlated interferon signalling pathway genes—IFIT2, TLR1, NMI—show increase in gene abundance in pain. Scale bar = 20 μm, large globular structures are considered to be lipofuscin. Yellow arrows point out cells with overlap of expression between the gene of interest (red) and AIF1 (white), cyan arrows point out overlap of expression between the gene of interest (red) and TRPV1 (green), respectively, in the zoomed in images, and pink arrows point to lipofuscin (A and C). In all micrographs, wide field views and zoomed-in views on single neurons and surrounding cells are shown to display overall signal distribution, and colocalization of signal with specific neuronal and macrophage cell markers for each RNAscope probe.

Data availability

Raw RNA sequencing and processed RNA sequencing data are available in dbGaP under accession number phs001158.v2.p1.

Results

We analysed abundance of neuronally enriched genes in 70 DRGs collected from thoracic vertebrectomy patients (patient information shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We tabulated relative abundance of all non-mitochondrial coding genes in the hDRG for each sample (Supplementary Table 2A) and based on the abundance of neuronally enriched genes, calculated the neuronally enriched mRNA panel index for each sample (Supplementary Table 2B). We grouped the samples in two: samples with low or moderate neuronal mRNA proportion and samples with a higher proportion of neuronal mRNA (Supplementary Table 2B). We found 1239 genes to be strongly correlated to the neuronally enriched mRNA panel index, including most known sensory neuron-enriched genes (including P2RX3, SCN9A, SCN10A, SCN11A, CALCA and CALCB; Supplementary Table 2C). We identified 51 samples with higher proportions of neuronal mRNA and these RNA abundance profiles were retained for downstream analysis (Supplementary Table 2D). All samples had sufficient library complexity (>12 000 coding genes detected). Quantile-normalization was performed on all samples to account for sample-to-sample differences in library complexity and sequencing depth (qnTPMs for retained samples provided in Supplementary Table 2E).

Transcriptome-wide association of gene expression with neuropathic pain

Based on our association analysis of gene abundances, we found that 195 genes were increased (pain-associated) and 70 genes were decreased in male DRG samples with dermatomes associated with neuropathic pain (Supplementary Table 3A and B), while 576 genes were increased (pain-associated) and 254 genes decreased in pain-associated female DRG samples (Supplementary Table 3C and D). The higher number of female pain-associated genes is likely due to using consistent thresholds for effect sizes across sexes, while the ratio of the number of samples to the number of subjects in the female pain subcohort (12:9 = 1.33) is higher than the corresponding ratio in the male pain subcohort (19:15 = 1.26), leading to lower within-group variability.

Both male (including IL1B, TNF, CXCL14, OSM, EGRB, TRPV4, LIF, CCL3/4) and female (including CCL1, CCL19, CCL21, PENK, TRPA1, ADORA2B, GLRA3) pain-associated genes showed a strong enrichment of genes that are well known to be pain-, nociception- or inflammation-related.38 The top pain-associated genes (ranked by the area between the quantile curves of each pain state) that are increased in the pain state in males and females are shown in Figs 1 and2, respectively. Strikingly, at the same effect size, only a handful of the male and female genes with pain-associated increases overlapped, including ACAN, CPXM1, DIO2, FNDC1, HAMP, IQGAP3, LAIR2, LILRA5, LMNB1, LRRC24, LY6G5C, SIGLEC7 and TGM, with only HAMP among the top 25 pain-associated genes for either sex to have a median fold change of >2.0 for both sexes (Fig. 3A). This suggests that the enriched immune cell types and regulatory pathways in these sex-stratified subcohorts are strikingly different and raises the possibility that neuronal changes driven by neuro-immune interaction may be sex differential too.

Intersectional analysis showed overlap in upstream and downstream signalling components for OSM, AP-1, IL-5, IL-1, TNF-alpha and NFKB pathways in the male pain-associated genes (Supplementary Table 3A). The TNF-alpha pathway activates the JUN-FOS family of TFs that were also pain-associated in our male data. In turn, multiple pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (including IL1B, OSM) as well as TNF, known to be upregulated by the JUN-FOS regulatory cascade, were increased in male pain samples. JUN-FOS and TP53 regulatory signalling was analysed in more detail in the coexpression module analysis. Other factors known to upregulate JUN/FOS signalling such as LIF39 were also increased in mRNA abundance for male pain samples, suggesting redundant upstream signalling through this important transcriptional regulatory pathway. For genes decreasing in male pain samples, we identify several immune cell surface markers (CD2, CD96), suggesting that immune cell types that decrease in proportion are represented in this list (Supplementary Table 3B).

For female pain-associated genes, we found overlap with PIK3C, Interferon signalling, JAK-STAT, TLR and IL-5 pathways (Supplementary Table 3C). While IL5 itself is de-enriched in female pain samples, IL-5 is typically upstream of interferon pathways, and there is likely overlap in IL-5 and interferon signalling pathways. JAK-STAT signalling is also a primary driver of interferon signalling. We found enrichment of both Type I (alpha) and Type II (gamma) interferon signalling pathway genes (both interferon stimulating like TLR3 and interferon response like IFIT1), which are profiled in more detail in the coexpression module analysis. Female pain-associated genes that decrease in the pain state also have some immune cell markers (CD300LB, CCL4L2), again suggesting that some immune cells increase in frequency at the expense of others (Supplementary Table 3D).

The overlap of some signalling pathways in males and females (TGF-beta and IL-5 pathways) but relatively few overlaps in the gene set suggests that the pain-associated signalling can use common pathways in males and females. However, our findings show that transcriptome enrichment is seen in different parts of the pathway in each sex, similar to our findings in rodent models. This could occur due to sex-specific factors like sex hormone regulation and X-linked gene expression. Additionally, such sex-dimorphic gene expression is likely to drive sex-differential signalling (shown in Fig. 3B), as detailed in the following sections.

Gene expression changes specific to preoperative medication

We identified 127 genes that increased with LDPN-inducing chemotherapeutic agent use in male pain samples (Supplementary Table 3G). Supplementary Fig. 3 visualizes expression profiles of a select list of genes within the top 30 upregulated genes in male patients with neuropathic pain who used LDPN-inducing chemotherapy agents. Of note, SFRP2 and MRC1 have roles in macrophage proliferation after neurological injury.40,41 Other genes are implicated in inflammatory and demyelinating neurologic disease (IL7R42), recovery after neurological injury (ARPP2143) and osteoarthritis development (ITGA844). Even though the number (3) of male chemotherapy pain patients that satisfied the criteria for analysis was small, these findings suggest that further transcriptomic changes driven by chemotherapeutic agents can be detected in hDRG samples with larger sample sizes.

Differential expression analysis of paired samples in patients experiencing unilateral pain

We expanded paired analysis for DRGs taken from both sides in male patients with unilateral pain based on our original study.17 We reanalysed our data with the paired samples from the additional patient and were able to identify 216 genes that increase and 154 genes that decrease in the pain-associated DRGs. These are in close agreement with the distributional analysis-based gene sets identified for the male subcohort in the previous section. For instance, we again found a strong enrichment for JUN-FOS signalling in the gene set increased with pain with multiple members of the transcriptional regulatory cascade being increased in abundance (FOS, FOSB, FOSL1, FOSL2, JUNB, ATF3, EGR1, EGR3). While JUN-FOS signalling is involved in cellular plasticity in many cell types, it has been implicated in pain since the 1990s45 and has recently been implicated as a key regulator of long-term neuropathic pain in mice.46 A complete list of the genes increased or decreased in pain samples of matched pairs is presented in Supplementary Table 3E and F. We did not have patient-matched pairs of pain and no-pain DRGs from female patients to complete a similar analysis.

Mining large coexpressional modules in male and female data for functional annotation

We identified many coexpression modules where gene expression changes were correlated in a sex-stratified subcohort. Our work identifies several large coexpression modules—two of which we profiled here: one in males and one in females. The coexpression module members are listed in Supplementary Table 3H–K and visualized in Figs 4 and 5. We chose to highlight the OSM coexpression module in males and the IFIT1 coexpression module in females because they have a large number of coexpressed genes (>500), well-known connection to pain pathways and clear evidence of transcriptional regulation (JUN-FOS-based regulation in OSM module, JAK-STAT signalling in IFIT1 module). Oncostatin M (OSM) belongs to the IL6 family of cytokines and signals via OMSR and the signal transducer protein GP130. OSM has been shown to sensitize sensory neurons and promotes inflammatory pain and itch in rodents.47–50IFIT1 is an interferon-stimulated gene that binds to the translation initiation complex eIF3.51 Like many interferon-stimulated genes, IFITs have been shown to play a role in host antiviral defences and in cancer.52

We identified 209 TF genes that were correlated in expression to OSM (Supplementary Table 3H) including several that are well known to be implicated in the TNF and OSM pathways (several members of the JUN-FOS family, RELA, RELB, NFKB2, CEBPB, TP53 shown in Fig. 4A). We found that the OSM coexpression module included 697 genes, including pro-inflammatory cytokines such as OSM and CXCL16, MAPK signalling genes (MAP2K3, MAPKAPK3), TP53 pathway (TP53, PLK3, TRAF4) and TNF-signalling (PLAU, TNFSF9, CSF1) pathway molecules and was the largest pain-associated coexpression module in males (Supplementary Table 3I and Fig. 4B). Multiple members of the JUN-FOS signalling cascade (FOS, FOSB, JUNB, EGR3) that are regulated by the JUN-FOS (AP-1) transcriptional regulation and TNF signalling were present in this module. TNF itself and pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL32 were coexpressed with OSM, although with a correlation coefficient between 0.55 and 0.76, likely because they are upstream of OSM or co-regulated (Fig. 4A). This finding suggests a key role for active transcriptional programs in pro-inflammatory cytokine signalling within the DRG in neuropathic pain. In rodent models, importin α3 has been shown to be crucial for nuclear import of FOS, known to be important in maintenance of chronic pain,46,53 suggesting that a similar mechanism may be at work in humans.

We found 130 TF genes to be coexpressed with IFIT1, including multiple TF genes that are interferon-inducing (KLF12, REL, ONECUT2) or interferon-stimulated (STAT1, STAT4, RORA, NFKB1), suggesting a role for interferon signalling in this pathway (Supplementary Table 3J and Fig. 5A). Also, we found 743 genes to be coexpressed with IFIT1 across the whole transcriptome including IFIT1 and IFIT2, interferon-induced proteins that are involved in autoimmune disorders like lupus54 (Supplementary Table 3K and Fig. 5B). Other genes of the same family IFIT1B, IFIT3 and IFIT5 were part of the same module. STAT1, a transcription factor that is part of the JAK-STAT signalling pathway, a key component of interferon signalling,55 is present. Multiple other interferon-induced genes like IFI44, TLR1, CASP3 and CASP8 suggest increased interferon signalling in females with neuropathic pain, possibly in immune cells. Genes like KLF12 and REL suggest a role of T cells in the identified interferon signalling pathway.

Protein interaction networks

Many of the pain-associated genes we identified were immune signalling or immune response genes, consistent with a neuro-immune signalling complex in neuropathic pain DRGs that may be driving changes in nociceptor excitability. We found multiple ligand genes with increased abundance in pain that can signal to neuronally expressed receptors56 (Fig. 3B) enriched or expressed in hDRG neuronal subpopulations (which we described previously using spatial transcriptomics11). An example is QRFP, which is increased in male pain, coexpressed with OSM and signals to the hDRG-specific QRFPR that encodes a receptor signalling through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway,57 a pathway that is critical for regulation of nociceptor excitability.58–61 While multiple pathways are possibly involved in signalling from immune cells with pro-inflammatory phenotypes to sensory neurons, we found that TNF-alpha signalling components were present in multiple putative ligand–receptor interactions, where the ligand was male pain-associated (OSM, LIF, CCL3, TNF, AREG, ICAM3) and the receptor was known to be expressed in hDRG sensory neurons. In female samples, multiple interferon signalling related ligand–receptor interactions were identified where the ligand was female pain-associated and the receptor was expressed in human sensory neurons (CCL19, GZMB, CXCL10, IGF1).

StringDB-based protein interaction networks for the male and female pain-associated genes are presented in Supplementary Figs 1 and 2. In the male signalling network (Supplementary Fig. 1) is a densely connected network of nine genes (including TNF), which are expressed in the hDRG interact with pain-associated gene products. More importantly, members of this network, as well as IL1B and CCL4, are part of multiple, interwoven signalling networks (TNF, TLR, growth factor and cytokine-based signalling) associated with neuropathic pain in males.

In the female signalling network (Supplementary Fig. 2), we identified multiple type I and II interferon-stimulated genes (IFIT1/2, GBP2/3/7, CD2, HLA-DQB1, CXCL10). This again supports a prominent role of interferon signalling in neuropathic pain in females. The role of genes like IFIT1 and IFIT2 in diseases like lupus and sickle cell disease54,62 and the role of female sex hormones in interferon signalling in autoimmune diseases63 suggest the possibility of autoimmune signalling in a subset of the female pain samples.

Additionally, densely connected subgraphs for centromeric proteins (Supplementary Fig. 2), and proteins involved in cell cycle and proliferation suggest that a significant part of the bulk RNA-seq transcriptomes are driven by proliferating cell types in both sexes. These cells are likely pro-inflammatory because in both the male and female signalling networks inflammatory cytokine signalling was identified.

It is evident from our pain-associated gene sets that a significant number of these genes are immune signalling and immune response genes. It is also well known that a wide range of immune responses are sex-differential in nature and at least partially evolutionarily conserved in mammals. While there are likely many reasons for this, one potential reason is sex hormones (oestrogen/androgen). Supplementary Table 3L tabulates products of pain-associated genes we identified that are known to interact with or be regulated by sex hormonal pathways in mammals (including IFIT1 and OSM).

RNAscope analysis

Based on our findings from the RNA-seq analysis, we performed RNAscope in situ hybridization on a subset of pain and non-pain samples to assess the cellular distribution of DE genes. We used a qualitative approach due to the limited availability of banked fresh-frozen tissue samples. For RNAscope, besides our genes of interest, we used the additional channels for marker genes to label specific cell types. We used TRPV1 to label all nociceptors9–11; AIF1, which is expressed by the monocyte/macrophage lineages in the nervous system64; as well as some T cells65 and DAPI to label all nuclei.

RNAscope for male samples

For the male samples, we examined cellular expression profiles of several genes that were well correlated with OSM expression (all with Pearson’s R ≥ 0.54, uncorrected P-value ≤ 0.0017): TNF, IL32, IL1B and OSM itself. OSM signals through the GP-130 complex, using OSMR as a co-receptor.66 OSM is known to promote nociceptor sensitization in rodents,47,49 suggesting that it may be a key signalling molecule for neuropathic pain in humans, in particular males. Our RNAscope imaging showed TNF expression in both nociceptors (TRPV1+ cells) and some TRPV1− sensory neurons, AIF+ immune cells and some AIF− non-neuronal cells, suggesting that immune cell-driven TNF signalling could promote TNF expression in nociceptors, or vice versa, in a feedback loop (Fig. 6A and B). Additionally, we found OSM, IL32 and IL1B primarily expressed in AIF1+ immune cells, likely macrophages, but we additionally note some expression in AIF– non-neuronal cells (Fig. 6C and D).

RNAscope for female samples

Among the female pain-associated genes we found several (IFIT1, IFIT2, HLA-DQB1, TLR1, CXCL10, NMI) that could be type I or II interferon-stimulated and had a high dynamic range of 10-fold or higher variance across female pain samples (Fig. 7A–E). This supports the conclusion that a subset of female pain samples had activated interferon signalling pathways (Fig. 7D). Consistent with this, we found qualitatively more IFIT1 expression in the female pain samples. The gene was found in TRPV1-positive and TRPV1-negative neurons but showed the highest abundance in non-neuronal cells that were both AIF1-positive and AIF1-negative (Fig. 7A and B). HLA-DQB1 was highly expressed ubiquitously, although the very high expression of HLA-DQB1 in 86T6R RNA-seq was not qualitatively observed in the RNAscope assay (Fig. 7B and C).

A consistent observation from the female RNAscope assays was the high abundance of AIF1-signal in the female pain samples (85T3L and 86T6R), suggesting either macrophage infiltration into the hDRG or an increase in AIF1 transcription due to macrophage activation (Fig. 7A and C). Our images suggest the latter as we observe no visible difference in cell numbers; however, a formal analysis with more biological replicates would be needed to confirm this observation.

These cell-type specific expression studies provide consistent evidence of increased AIF1+ cell expression in pain-associated samples in males and females. However, these macrophages or T cells likely have different expression patterns in men and women given the upregulation of specific gene sets that we found to be enriched in this cell population using RNAscope. Our findings are consistent with emerging literature using rodents where macrophages and T cells are key players in neuropathic pain but with different signalling molecules from these cells promoting pain depending on sex.21,67,68

Discussion

We reach several conclusions based on the data presented here. First, we observed major sex differences in changes in gene expression in the hDRG associated with neuropathic pain. This difference is consistent with a growing number of findings from rodent models (reviewed in20), but our findings highlight different sets of genes as potential drivers of neuropathic pain, in particular in females. Second, our work highlights the important role that neuro-immune interactions likely play in causing neuropathic pain.6 These cell types may differ between men and women,18,21,68 and the ligand–receptor interactions that allow these cells to communicate with nociceptors in the DRG almost certainly differ between men and women, even if cell types are consistent between sexes. Finally, our work points to therapeutic targets for neuropathic pain based on molecular neuroscience insight in patients. Again, these targets are sex dimorphic with a FOS/JUN-driven cytokine profile a dominant feature in males and type I and II interferon signalling playing a key role in females. Additional work will be needed to evaluate the clinical translatability of these findings.

One potential shortcoming of our work is the use of bulk rather than single-cell or spatial transcriptomics. These single-cell69 and spatial11 technologies have now been used successfully on hDRG, hence these technologies will be valuable for future studies on hDRG samples from thoracic vertebrectomy patients. We chose to focus on bulk sequencing because we did not have an a priori notion of which cell types to focus on and hence were unable to do targeted sequencing of specific cell types, and we were concerned about financial constraints on the large sample size required to thoroughly assess sex differences in this patient population. In that regard, this study builds upon our previously published work where we speculated on sex differences in neuropathic pain-associated expression changes in the DRGs of thoracic vertebrectomy patients,17 but we did not have a sufficient sample size to make such a direct comparison in that study. We have now achieved a sufficient sample size and observed robust changes in gene expression associated with neuropathic pain in both sexes. This justifies the choice of bulk sequencing and shows that it gives a unique insight into overall changes in gene expression that can now be exploited more thoroughly using single-cell and spatial techniques. Our work also generates a set of testable hypotheses, e.g. the effect of interferons on female DRG neurons, which can be tested in physiological experiments. RNAscope examines cellular expression patterns and shows that changes in gene expression can be observed across multiple cell types demonstrating that spatial transcriptomics approaches may be the most suitable for understanding the complex interactions that likely occur between non-neuronal and neuronal cells in the neuropathic DRG. Our future work will employ this technology to better understand neuro-immune interactions and the immune and neuronal subpopulations involved, as we have already demonstrated its utility in identifying sensory neuron subtypes in DRGs from organ donors.11 Finally, our work assesses relative RNA abundances and not the actual protein abundances. While RNA abundance is often representative of protein abundance, translational and post-translational regulation can further modulate the response we observe here, and we aim to follow-up our studies with targeted proteomic and phospho-proteomic assays.

Spontaneous or ectopic activity in DRG neurons is a likely cause of neuropathic pain8,17,70,71 and may be a driver of pain in other diseases, like fibromyalgia.72 This ectopic activity generates an aberrant signal that is conveyed through the spinal cord to the brain to cause pain sensations in people who suffer from neuropathic pain. Ectopic activity can originate from axons, in particular early after injury, but it can also emerge from the DRG soma.73 This likely happens due to changes in expression of ion channels in the DRG neuronal soma74 or due to signalling events that cause the neuron to generate ectopic action potentials and instability in the resting membrane potential.75–79 Our previous work clearly showed that hDRG neuron somata from neuropathic pain patients could display ectopic activity, even after surgical removal and culturing.17 Our current work gives important clues to what might drive these changes in patients. Moreover, our findings suggest that although the resultant DRG neuronal phenotype in males and females is the same, ectopic activity, it is likely driven by unique intercellular mechanisms. In males those mechanisms appear to involve cytokines like TNFα, IL1β and OSM that likely originate from macrophages, but may also be released from neurons themselves. These findings in males are supported by findings from animal models where macrophages have been implicated in development of chronic pain.21,68 In females the picture is much different. We discovered a network of genes associated with type I and II interferons that are positively correlated with neuropathic pain in women undergoing thoracic vertebrectomy. Interferons have been linked to pain sensitization80 and also to analgesia81 by previous studies, but their sex-specific role in neuropathic pain has not been studied. Examining the effect of type I and II interferons on female hDRG neurons should be a priority for future work.

While our work gives unique insight into mechanisms of neuropathic pain, it is not feasible to sample the DRG of the vast majority of pain patients. How can this work be used to facilitate precision medicine that can address underlying pain mechanisms in individual patients? Our findings demonstrate that immune cells in the DRG take on a proliferative role in neuropathic pain and these cells may be infiltrating the DRG from the peripheral circulation. It is also possible that the cytokines generated within the DRG may have an influence on peripheral immune cells. Both scenarios raise the possibility that specific cell types in the blood could be sampled to gain insight into molecular changes in the DRG without actually accessing the DRG. Animal studies have demonstrated that brain transcriptome changes in neuropathic pain models can be represented in immune cells transcriptomes in the periphery.82 Likewise, clinical studies have shown blood transcriptomic differences that predict chronic low back pain susceptibility.83 A key question is which cells to sample to gain the greatest insight into underlying mechanisms. From our work we propose that the candidate cell types may differ by sex. In males, monocytes would be a clear candidate cell type given the changes observed in male neuropathic pain DRGs. In females this is less clear, but T cells and monocytes would be good candidates. One possibility is that monocytes are key players in both sexes, but these cells simply have fundamentally different repertoires of ligands that they express that then communicate with unique receptors expressed by DRG neurons. They may also have unique honing mechanisms that drive cells from the peripheral circulation into the DRG.

In closing, our findings make a strong case for important sex differences in neuropathic pain mechanisms in the hDRG. Male mechanisms are closely tied to inflammatory cytokines that have been studied widely in preclinical models for decades. Female mechanisms appear to involve interferon-stimulated genes and represent signalling mechanisms that are not widely studied in preclinical models. This highlights the importance of considering sex as a biological variable, not only for basic science insight, but also in developing therapeutic strategies to treat neuropathic pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the tissue donor patients and their families and the surgical and medical staff, without whose assistance this work would not be possible. The authors would also like to thank all members of the genome sequencing core at UT Dallas, and Andi Wangzhou for help with the sequencing and mapping protocols. We would like to acknowledge the Southwest Transplant Alliance for recovery of sample AIDC291.

Contributor Information

Pradipta R Ray, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Stephanie Shiers, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

James P Caruso, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA; Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Diana Tavares-Ferreira, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Ishwarya Sankaranarayanan, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Megan L Uhelski, Department of Pain Medicine, Division of Anesthesiology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Yan Li, Department of Pain Medicine, Division of Anesthesiology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Robert Y North, Department of Neurosurgery, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Claudio Tatsui, Department of Neurosurgery, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Gregory Dussor, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Michael D Burton, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Patrick M Dougherty, Department of Pain Medicine, Division of Anesthesiology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Theodore J Price, Department of Neuroscience and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, USA.

Funding

NS111929 (to P.M.D. and T.J.P.), NS102161 (to T.J.P.).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests. T.J.P., G.D. and P.R.R. are co-founders of Doloromics.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

References

- 1. Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. . Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell MC, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain. 2019;20:146–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. . Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Price TJ, Gold MS. From mechanism to cure: renewing the goal to eliminate the disease of pain. Pain Med. 2018;19:1525–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Price TJ, Ray PR. Recent advances toward understanding the mysteries of the acute to chronic pain transition. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019;11:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ji RR, Chamessian A, Zhang YQ. Pain regulation by non-neuronal cells and inflammation. Science. 2016;354:572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sommer C, Leinders M, Üceyler N. Inflammation in the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2018;159:595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Middleton SJ, Barry AM, Comini M, et al. . Studying human nociceptors: From fundamentals to clinic. Brain. 2021;144:1312–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shiers S, Klein RM, Price TJ. Quantitative differences in neuronal subpopulations between mouse and human dorsal root ganglia demonstrated with RNAscope in situ hybridization. Pain. 2020;161:2410–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shiers SI, Sankaranarayanan I, Jeevakumar V, Cervantes A, Reese JC, Price TJ. Convergence of peptidergic and non-peptidergic protein markers in the human dorsal root ganglion and spinal dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol. 2021;529:2771–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tavares-Ferreira D, Shiers S, Ray PR, et al. . Spatial transcriptomics reveals unique molecular fingerprints of human nociceptors. bioRxiv., preprint: not peer reviewed. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidson S, Golden JP, Copits BA, et al. . Group II mGluRs suppress hyperexcitability in mouse and human nociceptors. Pain. 2016;157:2081–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ray P, Torck A, Quigley L, et al. . Comparative transcriptome profiling of the human and mouse dorsal root ganglia: An RNA-seq-based resource for pain and sensory neuroscience research. Pain. 2018;159:1325–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rostock C, Schrenk-Siemens K, Pohle J, Siemens J. Human vs. mouse nociceptors—Similarities and differences. Neuroscience. 2018;387:13–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Price TJ, Basbaum AI, Bresnahan J, et al. . Transition to chronic pain: opportunities for novel therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:383–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Renthal W, Chamessian A, Curatolo M, et al. . Human cells and networks of pain: Transforming pain target identification and therapeutic development. Neuron. 2021;109:1426–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. North RY, Li Y, Ray P, et al. . Electrophysiological and transcriptomic correlates of neuropathic pain in human dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain. 2019;142:1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sorge RE, Mapplebeck JC, Rosen S, et al. . Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1081–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosen S, Ham B, Mogil JS. Sex differences in neuroimmunity and pain. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1-2):500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mogil JS. Qualitative sex differences in pain processing: Emerging evidence of a biased literature. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020;21:353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu X, Liu H, Hamel KA, et al. . Dorsal root ganglion macrophages contribute to both the initiation and persistence of neuropathic pain. Nat Commun. 2020;11:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inyang KE, Szabo-Pardi T, Wentworth E, et al. . The antidiabetic drug metformin prevents and reverses neuropathic pain and spinal cord microglial activation in male but not female mice. Pharmacol Res. 2019;139:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agalave NM, Rudjito R, Farinotti AB, et al. . Sex-dependent role of microglia in disulfide high mobility group box 1 protein-mediated mechanical hypersensitivity. Pain. 2021;162:446–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, et al. . NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. PAIN®. 2011;152:14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, et al. . A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2204–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira A-M, et al. . GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D766–D773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. . STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang T-C, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. Stringtie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Nat Prec. 2010. doi: 10.1038/npre.2010.4282.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rigaud M, Gemes G, Barabas M-E, et al. . Species and strain differences in rodent sciatic nerve anatomy: Implications for studies of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;136:188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ho JW, Stefani M, Dos Remedios CG, Charleston MA. Differential variability analysis of gene expression and its application to human diseases. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i390–i398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Menashe I, Aloni R, Lancet D. A probabilistic classifier for olfactory receptor pseudogenes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ray PR, Khan J, Wangzhou A, et al. . Transcriptome analysis of the human tibial nerve identifies sexually dimorphic expression of genes involved in pain, inflammation, and neuro-immunity. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, et al. . The human transcription factors. Cell. 2018;172:650–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. . Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–W97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeanquartier F, Jean-Quartier C, Holzinger A. Integrated web visualizations for protein–protein interaction databases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. LaCroix-Fralish ML, Austin J-S, Zheng FY, Levitin DJ, Mogil JS. Patterns of pain: Meta-analysis of microarray studies of pain. PAIN®. 2011;152:1888–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, et al. . KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;36(suppl_1):D480–D484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Niehaus JK, Taylor-Blake B, Loo L, Simon JM, Zylka MJ. Spinal macrophages resolve nociceptive hypersensitivity after peripheral injury. Neuron. 2021;109:1274–1282.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mei J, Zhou F, Qiao H, Li H, Tang T. Nerve modulation therapy in gouty arthritis: Targeting increased sFRP2 expression in dorsal root ganglion regulates macrophage polarization and alleviates endothelial damage. Theranostics. 2019;9:3707–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim JY, Cheong HS, Kim HJ, Kim LH, Namgoong S, Shin HD. Association analysis of IL7R polymorphisms with inflammatory demyelinating diseases. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chai Z, Zheng P, Zheng J. Mechanism of ARPP21 antagonistic intron miR-128 on neurological function repair after stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8:1408–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44. Li HZ, Lu HD. Transcriptome analyses identify key genes and potential mechanisms in a rat model of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naranjo J, Mellström B, Achaval M, Sassone-Corsit P. Molecular pathways of pain: Fos/Jun-mediated activation of a noncanonical AP-1 site in the prodynorphin gene. Neuron. 1991;6:607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marvaldi L, Panayotis N, Alber S, et al. . Importin α3 regulates chronic pain pathways in peripheral sensory neurons. Science. 2020;369:842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Langeslag M, Constantin CE, Andratsch M, Quarta S, Mair N, Kress M. Oncostatin M induces heat hypersensitivity by gp130-dependent sensitization of TRPV1 in sensory neurons. Mol Pain. 2011;7:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. . A sensory neuron-expressed IL-31 receptor mediates T helper cell-dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:448–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Garza Carbajal A, Ebersberger A, Thiel A, et al. . Oncostatin M induces hyperalgesic priming and amplifies signalling of cAMP to ERK by RapGEF2 and PKA. J Neurochem. 2021;157:1821–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tseng PY, Hoon MA. Oncostatin M can sensitize sensory neurons in inflammatory pruritus. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabe3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hui DJ, Bhasker CR, Merrick WC, Sen GC. Viral stress-inducible protein p56 inhibits translation by blocking the interaction of eIF3 with the ternary complex eIF2.GTP.Met-tRNAi. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39477–39482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fensterl V, Sen GC. Interferon-induced IFIT proteins: Their role in viral pathogenesis. J Virol. 2015;89:2462–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yousuf MS, Price TJ. The importins of pain. Science. 2020;369:774–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ye S, Pang H, Gu Y-Y, et al. . Protein interaction for an interferon-inducible systemic lupus associated gene, IFIT1. Rheumatology. 2003;42:1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signalling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20059–20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wangzhou A, Paige C, Neerukonda SV, et al. . A ligand–receptor interactome platform for discovery of pain mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Sci Signal. 2021;14: eabe1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li H, Lou R, Xu X, et al. . The variations in human orphan G protein-coupled receptor QRFPR affect PI3K-AKT-mTOR signalling. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e23822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Geranton SM, Jimenez-Diaz L, Torsney C, et al. . A rapamycin-sensitive signalling pathway is essential for the full expression of persistent pain states. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15017–15027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jimenez-Diaz L, Geranton SM, Passmore GM, et al. . Local translation in primary afferent fibers regulates nociception. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]