Abstract

Background

Developing accurate and reliable methods to estimate vaccine protection is a key goal in immunology and public health. While several statistical methods have been proposed, their potential inaccuracy in capturing fast intraseasonal waning of vaccine-induced protection needs to be rigorously investigated.

Methods

To compare statistical methods for estimating vaccine effectiveness (VE), we generated simulated data using a multiscale, agent-based model of an epidemic with an acute viral infection and differing extents of VE waning. We apply a previously proposed framework for VE measures based on the observational data richness to assess changes of vaccine-induced protection over time.

Results

While VE measures based on hard-to-collect information (eg, the exact timing of exposures) were accurate, usually VE studies rely on time-to-infection data and the Cox proportional hazards model. We found that its extension using scaled Schoenfeld residuals, previously proposed for capturing VE waning, was unreliable in capturing both the degree of waning and its functional form and identified the mathematical factors contributing to this unreliability. We showed that partitioning time and including a time-vaccine interaction term in the Cox model significantly improved estimation of VE waning, even in the case of dramatic, rapid waning. We also proposed how to optimize the partitioning scheme.

Conclusions

While appropriate for rejecting the null hypothesis of no waning, scaled Schoenfeld residuals are unreliable for estimating the degree of waning. We propose a Cox-model–based method with a time-vaccine interaction term and further optimization of partitioning time. These findings may guide future analysis of VE waning data.

Keywords: estimating waning of vaccine effectiveness, vaccine efficacy, multiscale modeling, Cox proportional hazards model, scaled Schoenfeld residuals

Using simulated data, we compared different measures of vaccine effectiveness for capturing the intraseasonal waning of vaccine-induced protection. We propose an extension of the Cox model based on including a time-vaccine interaction term with further optimization of partitioning time.

Accurate estimation of the extent of waning of vaccine-induced protection over time is an important public health need. Epidemiological data shows that protection from the influenza and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines could wane intraseasonally [1–4]. While vaccine effectiveness (VE) measured a month after the second dose for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) messenger RNA vaccines was >90% [5–7], a resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vaccinated people occurred approximately 6 months after vaccination [3], indicating relatively fast waning of vaccine-induced protection and raising questions about the necessity for single or potentially multiple booster shots. Similarly, data show that influenza vaccine protection may wane intraseasonally [1, 2, 4, 8–10] with the odds ratio of testing positive for influenza in one study increasing linearly by approximately 16% for each additional 28 days since vaccination [4].

We note that for both influenza and COVID-19 vaccines, the decline in VE is associated with declining levels of antibody and antigenic evolution away from the vaccine strain. While antibody decline is a general phenomenon, for many other pathogens, such as diphtheria and tetanus, antibody titers may be far above the threshold of protection for decades after immunization [11]. For coronaviruses, in contrast, natural infection, which usually gives stronger and longer lasting protection relative to vaccines [12, 13], still allows individuals to be reinfected even with the same strain after 12 months [12, 14], indicating inherently short-lived protection.

In the current study, we use multiscale, agent-based models (rather than ordinary differential equations models, see Supplementary Figure 1) to compare different methods for estimating waning of VE. Although multiple methods for estimating waning of VE have been proposed and used [10, 15–20], relatively few simulation studies have compared the accuracy of these methods [21, 22]. We find that a commonly used method using scaled Schoenfeld residuals [23] (see the Supplementary Materials for description of Schoenfeld residuals) is reasonably accurate in detecting the presence or absence of waning but may be unreliable in estimating the degree of waning. This unreliability arises because the method actually estimates an approximation of an approximation of the time-varying hazard ratio, with both approximations potentially introducing substantial error. In contrast, we show that a relatively straightforward method, creating an optimized time-vaccine interaction, performed much better and can be easily implemented.

METHODS

We considered measures for VE based off the established framework [24, 25], where estimators are grouped into levels based on degree of information needed. Here, we focus on the direct effect of vaccination on susceptibility to infection, excluding indirect effects such as herd immunity.

Level 1 measures of VE require the most detailed information: the number of infections and exposures in both the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. Except in controlled challenge experiments, such data are typically unavailable but may sometimes be extrapolated from known household exposures [26, 27].

Easier to obtain, level 2 measures use infection data from both groups along with the person-time at risk for each group. Instead of knowing exact exposures, this assumes that contact rates with infectious individuals are approximately equivalent in both groups.

Level 3 measures use proportional hazards, with the Cox proportional hazards model named specifically by the established framework [24, 25]. The difference between levels 2 and 3 is relatively subtle. Level 3 needs the order in which infections occurred but not the actual timing. A comparison of these three levels is shown in Table 1. In practice, level 3 estimates are frequently used, as the Cox proportional hazards model is conveniently implemented in statistics software and can easily handle censoring and multiple, even time-varying, covariates. In addition, a convenient test for waning using the Schoenfeld residuals is available for this class of models.

Table 1.

Vaccine Effectiveness Measures for Susceptibility

| Measure | Formula | Required Data |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Time of exposures, vaccinations, and infections | |

| Level 2 | Time of vaccination and infection | |

| Level 3 | VE = 1 − Hazard ratio | Order of vaccination and infection |

Abbreviations: U, unvaccinated group; V, vaccinated group; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

In order to observe waning, we consider time-varying measures at all three levels. Time-varying level 1 and 2 estimates can be calculated over specified time periods or with moving averages to create a smoother appearance. There exists a standard method to extend the level 3 Cox model to be time varying for VE studies using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals [21]. Taking a local average of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals at a given time gives an estimate of the log of the hazard ratio (in this case comparing vaccinated with unvaccinated individuals) at that time and, hence, also an estimate of VE at that time.

While this local average is typically calculated using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) or natural splines, both of which give estimates that are continuous over time, for analytical tractability and to aid in direct comparison between all levels we derive local averages by creating bins (time categories) with a minimum of 100 events each, example in Supplementary Figure 2. We note that binning, local regression, and splines are all nonparametric methods that should converge to each other so long as model complexity is increased appropriately as sample size increases. As is shown in Supplementary Figure 3, our method of smoothing does not differ substantially from LOESS in this context. We use these same bins to derive estimates for all three levels. In addition to the level 3 method already described, we also consider another level 3 method, in which an interaction between vaccination and the time categories is used as the independent variable of the Cox regression.

RESULTS

To compare how the levels perform under different potential vaccine study circumstances, we modeled 4 separate epidemic scenarios, each with 100 000 individuals with 40% vaccine coverage per [28]. We consider a “leaky” vaccine that gives constant 80% protection, meaning that per exposure a vaccinated individual has 20% of the chance of being infected compared with an unvaccinated individual, in a study in which either all vaccinated individuals receive their vaccine on the same day or vaccination occurs over 30 days. We contrast this with a hypothetical leaky vaccine with waning protection decreasing from 100% to 0% protection over 60 days, where, again, vaccination occurs either on a single day or spread over 30 days. We intentionally model dramatic waning to test the limits of the methods. This setup is shown in Figure 1, giving both the VE value over time for a vaccinated individual and the average VE over time for not-yet-infected vaccinees.

Figure 1.

Comparing the true vaccine effectiveness (VE) values at the individual and population levels for 4 scenarios. A, Four scenarios, where either the vaccine protection remains constant at 80% or protection wanes from 100% to 0% over 60 days, with or without spread of vaccination. B, Individual level of protection. C, The population average equals the individual level of protection if vaccination occurs on a single day. D, Average protection in the susceptible vaccinated population when vaccination is spread over 30 days. (See Equation SM 1 in the Supplementary Materials).

For each scenario, we ran 100 simulations in which contacts are randomly generated, the probability of infection is based on vaccination status, and reinfection cannot occur in the short intraseasonal window. Owing to the stochastic nature of our simulations, a representative simulation was chosen for each scenario based on average infection numbers and epidemic peak timing. All simulations used previously estimated parameters for influenza (Supplementary Table 1) and were created with Julia software, version 1.3.1 [29]. All analysis was completed using R software, version 3.6.1 [30]. Other initial conditions, disease parameters, and forms of waning were considered but did not substantially change the results. These results, along with further modeling details, can be found in the Supplement (Supplementary Figures 1 and 6–13 and Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Estimating VE for Constant and Waning Protection

For constant 80% protection, all levels behave reasonably accurately (Figure 2A and 2B). The spread of vaccination understandably affects the dynamics of infection but shows little effect on the estimation. Visually, the effect of the vaccine appears to be constant for all levels except for some outliers when infection rates are low.

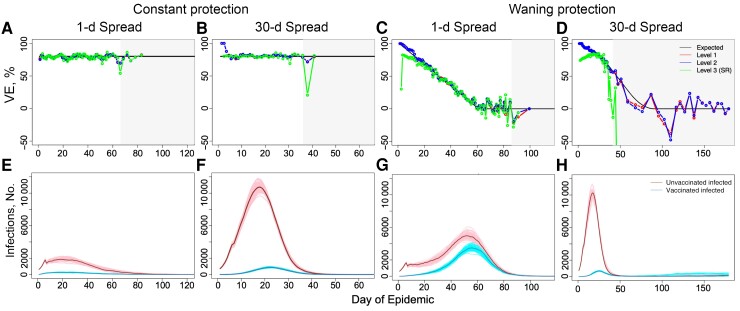

Figure 2.

Estimating vaccine effectiveness (VE) for constant (A, B, E, F) and waning (C, D, G, H) protection. When vaccine protection is constant at 80% for 1-day and 30-day spread of vaccination (A and B, respectively), all levels are reasonably accurate when infection numbers are high, as can be seen in their corresponding epidemic dynamics in E and F. If vaccination is spread, early results should be considered with caution owing to the extremely small relative size of the vaccinated group, which can lead to lack of infections and exposures in that group. C, D, When vaccine protection is waning, complications arise especially for level 3, which underestimates early season behavior. This is especially clear when vaccination is spread, as in D, with the level 3 scaled Schoenfeld residuals method (SR method) estimating accurately only at the very peak of infection. In A–D, light gray boxes display the region where total daily infections are low (<60 infections as suggested in [23]), and the x-axis ends on the day of the last infection.

However, as vaccine protection wanes, differences between the levels emerge and become more dramatic as vaccination is spread, as seen in Figure 2C and 2D. Levels 1 and 2 both capture early season behavior and remain similar until infection numbers become low. When considering a single day of vaccination, the level 3 scaled Schoenfeld residuals method (SR method) underestimates early season behavior and generally behaves less accurately than either level 1 or 2 estimates, with all three behaving more erratically as infection numbers decrease. When vaccination is spread over time, the SR method loses all accuracy except at the very peak of infection.

We especially focus on the scenario where vaccination is spread, as many real-world studies are based on observation or rolling enrollments. While VE studies often use the SR method [10, 18, 31], other fields using the Cox model for survival analysis have considered including a time-covariate interaction instead [32, 33]. In addition to the level 3 method already described, we also consider another level 3 method in which an interaction between vaccination and the time categories is used as the independent variable of the Cox regression. This method (TVI method), as seen in Figure 3, can improve accuracy in the VE estimate. In the next section, we explore the mathematical differences between the 2 methods, emphasizing the approximations that can lead to inaccurate results in the SR method.

Figure 3.

Inaccuracy not due to insufficient information for level 3. While the scaled Schoenfeld residuals method (SR method) for calculating level 3 values may fail in certain circumstances, level 3 estimates of vaccine effectiveness (VE) are not inherently inaccurate. With use of a time-vaccine interaction method (TVI method), as defined in the section Mathematical Factors Contributing to Inaccuracy of the SR Method, estimates for level 3 are quite similar to level 1 and 2 estimates.

Mathematical Factors Contributing to Inaccuracy of the SR Method

Given a study period j (time bin j), we consider the following equation,

| (1) |

where nj is the number of events in the time period j, Vj,i is an indicator variable for whether the ith infection (in time period j) is in a vaccinated individual, Zj,i is the proportion of the never-infected population that is vaccinated at the time of that ith infection, and is the coefficient, estimating the natural log of the hazard ratio, to be calculated. Here, the left-hand side of the equation is the observed fraction of infections that occurred in vaccinated individuals during the time period j, and the right-hand side is the fraction expected by the Cox model. Solving this equation exactly corresponds to implementing the TVI method. We note that this value of also corresponds to maximizing the partial likelihood function for the Cox model. For ease of legibility, we drop the 1/nj from both sides of the equation in the following steps.

Taking a first-order Taylor series expansion centered at of the right-hand side of the equation yields the following:

| (2) |

Here is the coefficient estimated by the simple Cox model without a time-vaccine interaction. If we introduce a weighting term,

| (3) |

the previous equation can be modified as shown here:

| (4) |

The above corresponds to the scaled Schoenfeld residuals method if the residuals are standardized using “event specific variance” as derived in [23]; henceforth, we called this the SRTV method. We note that the above weighting is algebraically necessary to easily extract residuals but further removes this equation from Equation 1. The reciprocal of this weighting term is often referred to as the “variance,” as it roughly corresponds to the variance of Vj,i and, in this case, it changes over time. Commonly, this time-varying “variance” is replaced by a constant average “variance” in the manner shown here,

| (5) |

where n is the total number of events observed across all time categories. This equation corresponds to the SR method using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals as implemented in R's survival package (the first of 2 “average variance” standardizations in [23]). We note that Equation 5 can be derived directly from Equation 2, so, any imprecision introduced by the weighting in Equation 4 is removed but at the cost of another assumption. Hence, both Equations 4 and 5 can be viewed as approximations of Equation 2, which is itself an approximation of Equation 1.

We find that simply taking the Taylor series expansion (Equation 2, TS method) introduces substantial error, shown in Figure 4. In this situation, the weighting introduced in Equation 4 has practically no effect. However, we cannot rule out that in other studies, such as those with much smaller samples, this weighting may be influential. Notably, by far the largest source of error was introduced by replacing the time-varying “variance” with a constant (Equation 5).

Figure 4.

Approximations of level 3 methods can lead to substantial error in estimates of vaccine effectiveness (VE). With each approximation from the time-vaccine interaction (TVI) method, error is compounded. With the first approximation coming from the Taylor series (TS) and its weighted version, the Schoenfeld residuals method with time-dependent variance (SRTV), error increases, especially when the number of events is low. This error increases further under the additional assumption that variance is fixed, giving the standard SR method. This error is obvious qualitatively and also when quantified by the root mean square error (RMSE).

Accuracy of Waning Detection Using the Schoenfeld residuals Test

As previously stated, level 3 has a statistical test for constant versus time-varying protection, which uses the correlation between the Schoenfeld residuals and time. When applied to simulations without waning, this test erroneously detected waning in 7% of cases for simulations with 1-day spread and 6% for simulations with 30-day spread. This is near the expected false-positive rate of 5%, and the overall p-value distribution falls near the expected uniform distribution (Supplementary Figure 4). The test correctly detects waning in 100% of the simulations that wane, which is not surprising given the large sample size and intentionally dramatic waning. Hence, this test performs appropriately in our simulations, even as the degree of waning is sometimes very poorly estimated by the scaled version of the Schoenfeld residuals.

Optimization of VE Estimation

While the level 3 TVI method was reasonably accurate, we used an arbitrary, though not unreasonable, number of events to partition time for the calculation of each method. To find optimized partitions for the TVI method, we considered various combinations of minimum number of days per bin and minimum number of events per bin to create partitions for several R0 values as shown in Figure 5. Specifics on bin creation can be found in Supplementary Materials. All simulations have the same waning of 100% to 0% with vaccination spread over 30 days.

Figure 5.

Rather than using simple 100-event bins, the time-vaccine interaction method can be further improved. Because we know the expected value for VE(t) (vaccine effectiveness over time) for each simulation, we can calculate the root mean square error (RMSE) for the time-stratified model against the expected value, but in a real-world study this would not be the case. However, over a variety of R0 values, we find that the minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC), shown as x’s in A–C, corresponds well to where low RMSE is found. Thus, despite the very different dynamics in each of these systems, a simple check over multiple minimums for events and days for minimum AIC should yield a good result.

Because we know the true value of protection, we can calculate the root mean square error (RMSE) for each combination; however, an analyst using a real-world data set would not have such knowledge. We found that the combination with the minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC), which requires no prior knowledge, generally corresponds to low RMSE and therefore can be used to create an optimal or near optimal estimate. The difference between our arbitrarily chosen 100-event minimum binned TVI model and the optimal AIC binned model is shown in Figure 6. This optimized level 3 TVI estimate avoids the underestimates of early season behavior that other level 3 methods display, closely follows the functional form of vaccine protection even as infection numbers diminish, and is also easy to compute.

Figure 6.

Optimizing the time categories gives an excellent visualization of the true form. In (A) simple 100-event partitions are used; in (B) partitions are a minimum of 6 days with 700 events, per the minimum Akaike information criterion for this simulation. This offers an improvement to the estimate even in such an extreme case using a relatively simple method. Optimizing the partitioning lowered the root mean square error from 4.33% to 2.85%. Abbreviations: SR, Schoenfeld residuals method; TVI, time-vaccine interaction method; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

Linear Interpolation Versus Step Function

For figures showing VE estimates, we used simple linear interpolations to connect the bins, but the underlying models are actually piecewise constant step functions, a biologically implausible pattern that may confuse certain readers. Hence, we considered the effect of replacing the underlying step function of the optimized TVI method with linear interpolation using the mean event time and VE estimate for each bin and then connecting those points. Linear interpolation performs both qualitatively and quantitatively better than the step function in this circumstance, improving RMSE from 2.85% to 1.55% with use of the optimized bins (Supplementary Figure 5). As such, we recommend linear interpolation to gain continuity and additional accuracy.

DISCUSSION

Correctly estimating VE and the extent to which it wanes is a key goal in immunology and public health, and several different methods for capturing the extent and form of waning have been proposed. We compared methods from a framework described elsewhere [24, 25], using a simulated seasonal epidemic of an acute viral infection. The level 1 and 2 methods performed reasonably well. However, we found that the level 3 scaled Schoenfeld residuals method (SR method), commonly used and recommended for VE studies, while potentially quite accurate in some circumstances, has difficulty capturing waning in some other scenarios. Moreover, the statistical justification for the SR method is questionable since the local average of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals, in general, is not and does not asymptotically approach the maximum partial likelihood value (Equation 1 vs Equation 5).

In stark contrast, in our simulations the Schoenfeld residuals test performed appropriately with regard to rejecting the null hypothesis of no waning. This discrepancy possibly arises because the null hypothesis of no waning is a special case in which the previously noted inconsistency, between the local average of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and the maximum partial likelihood value, vanishes asymptotically. We show that a straightforward approach, creating time categories and adding a time-vaccine interaction term as a predictor variable, the TVI method, performs accurately in all scenarios considered and sometimes much better than the SR method. Optimizing the time categories and adding linear interpolation further increases accuracy, yielding estimates that closely follow the functional form of vaccine protection in the population. Because this method uses only standard statistical techniques, it should be easy to implement in any statistical programming language that includes Cox regression. The most computationally difficult step, optimizing the time categories, can potentially be avoided or simplified by using prior knowledge to fix minimum number of days or minimum number of events or by optimizing only on the minimum number of events per bin.

Articles on VE have continued to recommend the scaled Schoenfeld residuals as a method to estimate VE over time [10, 16–20, 22]. For example, a recent article comparing statistical methods [22] concludes that this method is the best of the ones they tested. On this note, it makes sense to consider why our conclusions differ from those of previous studies. First, because the approximations inherent in the SR and SRTV methods are sometimes very accurate and at other times result in larger errors, it seems likely that other studies considered only scenarios in which the approximations are accurate. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, some of the other studies did not consider the full potential of the TVI method. One, for example, considers only a highly parametric interaction, vaccination by log(time) [22].

Finally, we examine some of the limitations of our study. We do not consider the thorny issues of heterogeneity in exposures, heterogeneity in VE, and unmeasured confounders. If there is substantial heterogeneity in exposures (beyond what is explained by covariates in the model), it is likely that the TVI method will overestimate waning, as is generally the case with level 2 and 3 methods [34]. We deliberately used a large sample size in our simulations, and smaller samples would have a different bias variance tradeoff. However, reducing the sample to 1000 infections gave similar results. In addition, we intentionally focused on relatively standard methods. We did not consider innovative and newer methods (eg, those used in [35] or [36]). It is likely that some of these methods may have superior performance, especially with smaller samples. Instead, we provide a baseline for what can be achieved using established statistical methods while avoiding the unreliability of the SR method.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author. The source code is available on GitHub: github.com/ZarnitsynaLab/ArielNikas-VEWaning.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ariel Nikas, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Hasan Ahmed, Department of Biology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Veronika I Zarnitsyna, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grants U01 HL139483, U01 AI150747, and U01 AI144616).

References

- 1. Belongia EA, Sundaram ME, McClure DL, Meece JK, Ferdinands J, VanWormer JJ. Waning vaccine protection against influenza A (H3N2) illness in children and older adults during a single season. Vaccine 2015; 33:246–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferdinands JM, Fry AM, Reynolds S, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine protection: evidence from the US influenza vaccine effectiveness network, 2011–2012 through 2014–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keehner J, Horton LE, Binkin NJ, et al. Resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a highly vaccinated health system workforce. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1330–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ray GT, Lewis N, Klein NP, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1623–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernal J L, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, et al. Waning of BNT162b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—eight US locations, December 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kissling E, Nunes B, Robertson C, et al. I-MOVE multicentre case-control study 2010/11 to 2014/15: is there within-season waning of influenza type/subtype vaccine effectiveness with increasing time since vaccination? Eurosurveillance 2016; 21:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kissling E, Valenciano M, Larrauri A, et al. Low and decreasing vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3) in 2011/12 among vaccination target groups in Europe: results from the I-MOVE multicentre case-control study. Eurosurveillance 2013; 18:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Truscon R, et al. Modest waning of influenza vaccine efficacy and antibody titers during the 2007–2008 influenza season. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Antia A, Ahmed H, Handel A, et al. Heterogeneity and longevity of antibody memory to viruses and vaccines. PLoS Biol 2018; 16:e2006601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Callow KA, Parry HF, Sergeant M, Tyrrell DA. The time course of the immune response to experimental coronavirus infection of man. Epidemiol Infect 1990; 105:435–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wright PF, Ross KB, Thompson J, Karzon DT. Influenza A infections in young children: primary natural infection and protective efficacy of live-vaccine-induced or naturally acquired immunity. N Engl J Med 1977; 296:829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edridge AWD, Kaczorowska J, Hoste ACR, et al. Seasonal coronavirus protective immunity is short-lasting. Nat Med 2020; 26:1691–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipsitch M. Challenges of vaccine effectiveness and waning studies. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1631–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alonso PL, Sacarlal J, Aponte JJ, et al. Efficacy of the RTS, S/AS02A vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum infection and disease in young African children: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364:1411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Durham LK, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME, Clemens JD, Nizam A, Rao M. Estimation of vaccine efficacy in the presence of waning: application to cholera vaccines. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147:948–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fong YY, Halloran ME, Park JK, Marks F, Clemens JD, Chao DL. Efficacy of a bivalent killed whole-cell cholera vaccine over five years: a re-analysis of a cluster-randomized trial. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Olotu A, Lusingu J, Leach A, et al. Efficacy of RTS, S/AS01E malaria vaccine and exploratory analysis on anti-circumsporozoite antibody titres and protection in children aged 5–17 months in Kenya and Tanzania: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:102–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Minsoko PA, Lell B, Fernandes JF, et al. Efficacy and safety of the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine during 18 months after vaccination: a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in children and young infants at 11 African sites. PLoS Med 2014; 11:e1001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Durham LK. Nonparametric exploration of waning vaccine effects using survival data. Atlanta, GA: Emory University, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haber M, Tate JE, Lopman BA, Qi W, Ainslie KEC, Parashar UD. Comparing statistical methods for detecting and estimating waning efficacy of rotavirus vaccines in developing countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17:4632–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994; 81:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halloran ME, Struchiner CJ, Longini IM Jr. Study designs for evaluating different efficacy and effectiveness aspects of vaccines. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 146:789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halloran ME, Longini IM, Struchiner CJ. Design and interpretation of vaccine field studies. Epidemiol Rev 1999; 21:73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fine PEM, Clarkson JA, Miller E. The efficacy of pertussis vaccines under conditions of household exposure. Further analysis of the 1978–80 PHLS-ERL study in 21 area health authorities in England. Int J Epidemiol 1988; 17:635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis XM, Haber M. Estimating vaccine efficacy from household data observed over time. Stat Med 2004; 23:2961–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- 29. Bezanson J, Edelman A, Karpinski S, Shah VB. Julia: a fresh approach to numerical computing. Siam Rev 2017; 59:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rane MS, Rohani P, Halloran ME. Durability of protection after 5 doses of acellular pertussis vaccine among 5–9 year old children in King County, Washington. Vaccine 2021; 39:6144–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Therneau TM, Crowson C, Atkinson E. Using time dependent covariates and time dependent coefficients in the Cox model. R Survival Package Vignette. 2021. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/timedep.pdf. Accessed 5 November 2021.

- 33. Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York, NY: Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Hagan JJ, Hernan MA, Walensky RP, Lipsitch M. Apparent declining efficacy in randomized trials: examples of the Thai RV144 HIV vaccine and South African CAPRISA 004 microbicide trials. AIDS 2012; 26:123–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tian L, Zucker D, Wei LJ. On the Cox model with time-varying regression coefficients. J Am Stat Assoc 2005; 100:172–83. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fintzi J, Follmann D. Assessing vaccine durability in randomized trials following placebo crossover. Stat Med 2021; 40:5983–6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.