Abstract

Precision medicine has been advanced as a potential solution to the problem of alcohol use disorder heterogeneity and modest alcohol use disorder treatment efficacy. The success of precision medicine lies in our ability to first identify the etiologic and maintenance mechanisms at play for a given person and then choose the treatment that is most likely to address such mechanisms. There exist several frameworks that describe empirically supported substance use disorder etiologic and maintenance mechanisms (e.g., the Etiologic, Theory-based, Ontogenetic, Hierarchical [ETOH] Framework). There also exists a large literature on mechanisms of behavior change in alcohol use disorder treatment. However, the mechanism of behavior change literature on alcohol use disorder treatments has focused broadly on mechanisms of change rather than more specifically on core alcohol use disorder etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. Thus, the two types of mechanisms have never been integrated or systematically evaluated for their overlap. As such, the aim of the current brief review is to demonstrate how commonly used alcohol use disorder treatments may overlap with and directly target certain alcohol use disorder etiologic and maintenance mechanisms (specifically those described by the ETOH Framework). We delineate empirically plausible overlapping mechanisms and theoretically plausible overlapping mechanisms that warrant more research. Last, based on the identification of empirically and theoretically plausible overlapping mechanisms, we elaborate on how ongoing work related to alcohol use disorder precision medicine may test specific hypotheses regarding which treatments work best for whom.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, etiology, treatment, mechanisms of behavior change, precision medicine

Approximately 14.8 million United States citizens aged 12 and older met criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 2018 (Lipari & Park-Lee, 2019). Despite the prevalence of AUD, treatments demonstrate only modest efficacy (Witkiewitz, Litten, et al., 2019). This is likely a result of the profound heterogeneity of AUD. There are 2,048 possible combinations of the 11 DSM-5 criteria that are sufficient for an AUD diagnosis (i.e., two or more criteria) (Lane & Sher, 2015), such that two individuals could receive an AUD diagnosis despite having no or few overlapping symptoms. Further, those diagnosed with AUD exhibit considerable heterogeneity in terms of clinical presentation, alcohol use patterns, risk profiles, alcohol-related consequences, and patterns of comorbid psychopathology (Litten et al., 2015). Thus, just because individuals meet the same AUD criteria does not necessarily mean their AUD was caused or has been maintained by the same mechanisms or processes (Boness et al., 2021). Consequently, a “one size fits all” approach to AUD treatment may not be effective.

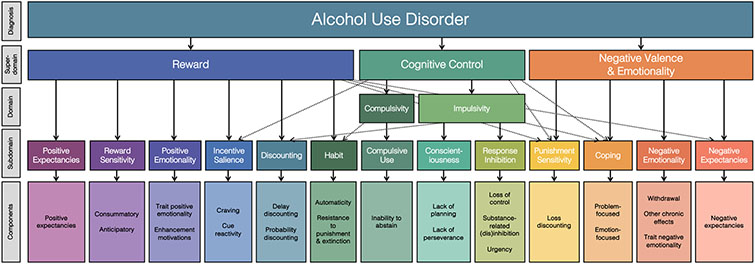

Precision medicine has been advanced as a potential solution to the problem of heterogeneity (Litten et al., 2012). Precision medicine is an approach that aims to match treatments to an individual’s unique profile of mechanistic dysfunction – or the failure of some process to perform a biologically designed function (Wakefield, 1992) – with the goal of improving treatment outcomes. In the service of precision medicine for substance use disorders, several frameworks have been developed with the aim of identifying etiologic mechanisms (i.e., how substance use disorders develop) and maintenance mechanisms (i.e., how substance use disorders are maintained across time) and clarifying sources of heterogeneity. For example, the Etiologic, Theory-based, Ontogenetic, Hierarchical (ETOH) Framework (Boness et al., 2021), which was developed from a systematic review of the AUD literature, integrates theoretical and empirical AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms into a dimensional and hierarchical framework (see Figure 1). The ETOH articulates 13 subdomains encompassing dimensional mechanisms, which include a range of processes that lead to the development or sustainment of alcohol use and AUD, including those processes that are psychological and cognitive in nature. The 13 subdomains fall into the broader domains of reward, cognitive control, and negative valence and emotionality. The mechanistic subdomains describe dimensional processes that cause or maintain AUD (see Appendix A for a glossary of ETOH terms). Although the ETOH structural model still requires empirical validation, it provides a useful framework for conceptualizing the key etiologic and maintenance mechanisms implicated in AUD. If a given person’s profile of functioning can be characterized using the ETOH Framework mechanisms, treatments that best address such mechanisms can be recommended. Thus, identifying the etiologic and maintenance mechanisms at play in AUD for a given person, or set of people, is vital for successful precision medicine efforts.

Figure 1. The Etiologic, Ontogenetic, Theory-based, Hierarchical (ETOH) Framework of Alcohol Use Disorder.

This figure depicts a visual of the ETOH Framework derived as a result of a systematic review of reviews on alcohol use disorder etiology (this figure is reproduced from Boness et al., 2021 under APA’s fair use criteria). It is intended to be iterative in nature and is, therefore, subject to updates as the literature develops further. The dashed lines indicate possible cross-loadings between domains. In some cases, components incorporate fine-grained facets that are described in text.

A key component of precision medicine is choosing the right treatment for a given person. Part of treatment selection in this effort requires an understanding of the mechanisms of behavior change for a particular treatment. Mechanisms of behavior change describe a process that occurs within a person, or a specific behavior a person engages in, that is associated with a subsequent change in the outcome of interest (e.g., alcohol use; Magill et al., 2015). Said differently, mechanisms of behavior change are those psychological, social, or neurophysiologic processes, that drive or cause changes in behavior – often in the context of specific therapeutic components or environmental factors (Kazdin, 2007; Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Magill et al., 2015). This stands in comparison to etiologic and maintenance mechanisms of AUD which are processes or behaviors that lead to AUD’s development or sustainment. However, it is important to point out that in many cases mechanisms of behavior change for AUD treatments are still not fully understood and efforts to clarify mechanisms of behavior change for several AUD treatments are still ongoing (Magill et al., 2020; McCrady, 2017). Further, testing for mechanisms of behavior change is not as simple as testing for statistical mediation, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a mechanism of behavior change.1 Mechanisms of behavior change must also demonstrate (a) strong associations; (b) specificity; (c) a gradient (i.e., dose response); (d) temporal relations; (e) consistency, or replication, of associations; (f) experimental control of the independent variable; and (g) plausibility and coherence of proposed mechanism(s) (Hill, 1965; Kazdin, 2007; Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Longabaugh et al., 2013; Longabaugh & Magill, 2011; Nock, 2007). Given efforts to identify mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatments is ongoing, it is imperative to identify mechanisms of behavior change that can be empirically tested according to these criteria and to prioritize treatments that evoke the mechanisms of behavior change that may be most beneficial in improving outcomes for those with AUD and related problems.

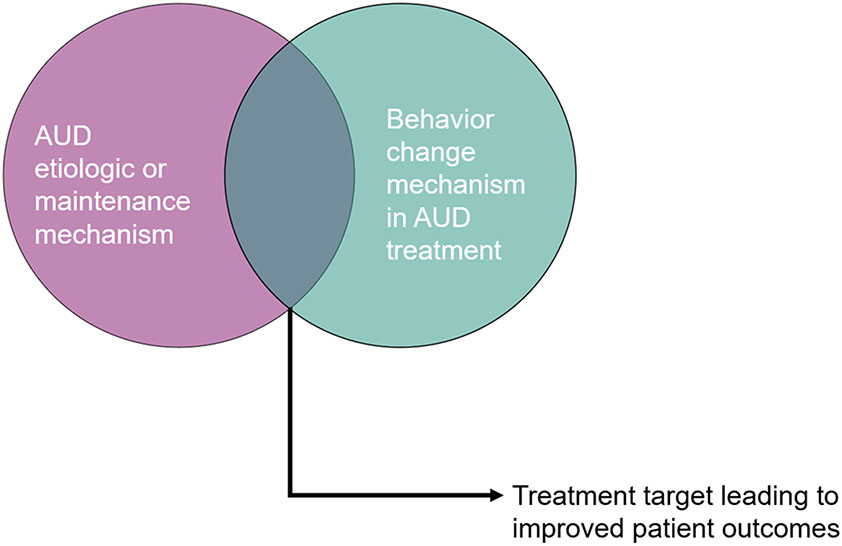

This brief review will focus on the overlap between etiologic and maintenance mechanisms in AUD2 and mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatments, to inform AUD precision medicine. In the sections that follow, we describe common AUD treatments with a particular focus on their specific mechanisms of behavior change and how these likely overlap with common AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms, using the ETOH Framework as a guide. Examining the overlap between mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatments and AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms using an empirically informed framework, such as ETOH, is key because most research on mechanisms of behavior change to date has focused broadly on mechanisms of change rather than more specifically on AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms (McCrady, 2017). As such, the aim of the current review is to demonstrate how commonly used AUD treatments’ mechanisms of behavior change may directly impact certain AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms and, thus, how ongoing work related to AUD precision medicine may test specific hypotheses regarding which treatments work best for whom (see Figure 2)3. Although we aim to highlight the etiologic, maintenance, and behavior change mechanisms implicated in AUD and AUD treatments with robust empirical support (per the previously described criteria on what constitutes a mechanism), we also call attention to a) empirically plausible mechanisms (e.g., mechanisms supported in mediation models), and b) theoretically plausible mechanisms that warrant more research (with “a” and “b” indicated as hypothesized mechanisms [H] in Table 1). We conclude with a discussion of practical implications and next steps for the field in the pursuit of precision medicine efforts for AUD. This brief review was not preregistered.

Figure 2.

Leveraging the overlap between etiologic and maintenance mechanisms in alcohol use disorder and behavior change mechanisms in alcohol use disorder treatment to improve patient outcomes. AUD = alcohol use disorder.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of behavior change for AUD treatments mapped onto ETOH AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms

| AUD Treatments |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETOH AUD Mechanisms | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for AUD |

Mindfulness- Based Addiction Treatments |

Contingency Management |

Motivational Interviewing |

Disulfiram | Naltrexone | Acamprosate | ||

| Superdomain | Subdomain | Components | |||||||

| Reward | Positive expectancies | Positive expectancies | H | H | H | H | |||

| Reward sensitivity | Consummatory reward sensitivity | ||||||||

| Anticipatory reward sensitivity | |||||||||

| Positive emotionality | Trait positive emotionality | H | |||||||

| Enhancement motivations | H | H | H | ||||||

| Incentive salience | Craving | H | H | H | H | ||||

| Cue reactivity | H | H | H | H | |||||

| Reward Discounting | Delay discounting | H | H | H | H | ||||

| Probability discounting | H | H | H | H | |||||

| Habit | Automaticity | H | H | H | H | ||||

| Resistance to punishment and extinction | |||||||||

| Cognitive Control | Compulsive use | Inability to abstain | H | H | H | H | |||

| Conscientiousness | Lack of planning | H | H | H | H | ||||

| Lack of perseverance | H | H | H | H | |||||

| Response inhibition | Loss of control | H | H | ||||||

| Substance-related dis(inhibition) | |||||||||

| Urgency | H | H | H | H | |||||

| Negative Valence & Emotionality | Punishment sensitivity | Loss discounting | |||||||

| Coping | Problem-focused coping | E * | H | H | |||||

| Emotion-focused coping | E * | H | H | ||||||

| Negative emotionality | Withdrawal-related negative emotionality | H | H | ||||||

| Other chronic effects | |||||||||

| Trait negative emotionality | H | H | H | ||||||

| Negative expectancies | Negative expectancies | H | H | H | H | H | |||

Note. AUD = alcohol use disorder; E = empirical support as mechanism of behavior change in the treatment; H = hypothesized mechanism requiring empirical support'

= some mixed findings, calling into question consistency or replicability of empirical support.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for AUD

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a psychosocial treatment premised on learning principles, has been classified as an efficacious, evidence-based treatment for AUD (Boness et al., 2022; Magill et al., 2019). CBT aims to reduce symptoms and improve functioning through targeting behavioral and cognitive processes that underlie or contribute to psychological disorders. CBT for AUD, and substance use disorders more broadly, frames the use of alcohol as a behavior that can be both positively and negatively reinforced and is influenced by social and other environmental contexts. CBT for AUD therefore focuses on intervening upon these processes through increasing awareness of antecedents and consequences of use, building skills that address internal or external antecedents, and leveraging behavior change principles to reduce or eliminate alcohol use (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017; McHugh et al., 2010).

The CBT mechanism of behavior change with the most support that also overlaps with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms, per the ETOH framework, includes improved coping skills (negative valence & emotionality: coping in Table 1; Kiluk, 2019; Kiluk et al., 2010; Roos et al., 2020). However, it’s important to note that there has been some mixed evidence in support of coping skills as a mechanism of behavior change in CBT (Longabaugh & Magill, 2011; Magill et al., 2020; Morgenstern & Longabaugh, 2000) which may be partially due to the quality and breadth of coping skills in a given study (Kiluk et al., 2010; Witkiewitz et al., 2018). Decreased craving (reward: incentive salience) also appears promising as mechanisms of behavior change in CBT for AUD but requires more empirical support (Magill et al., 2015).

Based on the core processes of CBT for AUD, including identifying antecedents to use through approaches such as functional analysis, skills training focused on developing alternative cognitive interpretations and behavioral responses to alcohol use, and tools to address craving, drink-refusal, affect regulation, and social skills, we also propose that CBT for AUD’s mechanisms of behavior change may overlap with several AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. Table 1 provides an overview of mechanisms of behavior change in CBT for AUD and overlapping ETOH AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. For example, coping skills would be encompassed by the ETOH negative valence and emotionality domain which includes coping, and specifically problem- and emotion-focused coping. Thus, for an individual with AUD whose profile is characterized by challenges in coping, CBT for AUD may lead to better outcomes for that person when compared to a treatment that does not target coping (Roos, Maisto, et al., 2017; Roos & Witkiewitz, 2016). Still, more research is required to empirically evaluate these mechanisms before conclusive statements can be made.

Mindfulness-Based Addiction Treatments

Mindfulness-based addiction treatments, encompassed more generally by mindfulness-based interventions, include treatments such as mindfulness-based relapse prevention (Witkiewitz et al., 2005) and mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (Garland et al., 2016). Mindfulness-based interventions and mindfulness-based addiction treatments engage current psychological treatment approaches alongside Buddhist traditions and training in mindfulness meditation practices (Witkiewitz et al., 2014). The practice of mindfulness meditation is a focused, purposeful, and non-judgmental attention to oneself, including thoughts and behavioral urges (Korecki et al., 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2014). Mindfulness thus often involves processes similar to those engaged by other psychological treatment modalities to improve self-regulation such as evaluating how thoughts are related to cravings and alcohol use, reframing experiences with acceptance, and observing and learning to tolerate discomfort (Witkiewitz et al., 2014). These interventions have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of AUD (Korecki et al., 2020).

Research on mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based interventions is still very much developing and replicable mechanisms have yet to be identified. The major proposed mechanisms of behavior change in mindfulness-based addiction treatments that a) overlap with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms and b) are supported through statistical mediation include processes that cut across all three ETOH superdomains. As shown in Table 1, mechanisms of decreased automaticity (reward: habit) and impulsivity (e.g., decreased urgency), and improved planning and perseverance (cognitive control: response inhibition, conscientiousness) may occur through improvements in awareness (Korecki et al., 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2014). Further, decreased craving and cue reactivity (Korecki et al., 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2013; reward: incentive salience), reductions in reactivity (Brewer et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2018; negative valence & emotionality: trait negative emotionality), and improved emotion- and problem-focused coping (negative valence & emotionality: coping), may potentially occur through reductions in avoidance (Bowen et al., 2006; Garland et al., 2010; Witkiewitz et al., 2014). Based on mediation models suggesting that mindfulness-based addiction treatments likely improve components of cognitive control (Hölzel et al., 2011), we also propose reduced delay and probability discounting (reward: reward discounting), increased ability to abstain (cognitive control: compulsive use), and decreased loss of control (reward: response inhibition) as potential mechanisms of behavior change that may be especially important given their role in AUD etiology and maintenance.

Contingency Management

Contingency management is a behavioral treatment that engages operant learning principles, specifically reinforcement and punishment, in the treatment of AUD and other substance use disorders as a way to encourage positive behavior change (e.g., moderation or abstinence) (Higgins & Petry, 1999). In practice, when patients engage in the target behavior, they are provided with rewards, such as prizes or vouchers that can be exchanged for money, goods, or services. When the target behavior is not met, or the patient engages in the undesired behavior, the reward is withheld. Target behaviors may include moderation or abstinence (which may be verified with lab tests), treatment attendance, engaging in activities consistent with treatment goals, or taking medication as prescribed (Petry, 2000). This type of reinforcement is thought to increase the response cost of the target behavior and the availability of other alternatives to the target behavior (Murphy et al., 2021). Although contingency management has been the most widely used and evaluated in the treatment of drug use (Pfund et al., 2021; Pfund et al., 2022), contingency management is also efficacious in reducing alcohol use (Barnett et al., 2011; Higgins & Petry, 1999; Petry et al., 2000).

Other than operant learning, additional mechanisms of behavior change in contingency management are largely unknown and the few studies that do aim to examine mechanisms have focused primarily on drugs other than alcohol (see Witkiewitz et al., 2022 for an overview). One additional plausible mechanism of behavior change in contingency management is discounting, including delay and probability discounting (reward: reward discounting in Table 1). Contingency management’s focus on reinforcing alternative behaviors to substance use may directly address steep delay and probability discounting by reducing the reinforcing value of alcohol (with respect to immediacy and certainty, especially) and increasing enjoyment of future-oriented, positive alternatives to alcohol use, even if less immediate or certain (Murphy et al., 2021; Stanger et al., 2013). Thus, modification of delay and probability discounting are proposed as potential mechanisms of behavior change in contingency management, but these require more research (Stanger et al., 2013). Finally, as a result of ongoing monitoring of behavior and modification of choices related to substance use, contingency management may also lead to change in substance use through reduced automaticity (reward: habit) and urgency (cognitive control: response inhibition), improvements in planning and perseverance (cognitive control: conscientiousness) and coping (negative valence & emotionality: coping), enhanced ability to abstain from alcohol use (cognitive control: compulsive use), and increased negative expectancies (negative valence & emotionality: negative expectancies) related to use.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a brief, directive, and patient-centered approach intended to engage people in conversations about change. Research generally finds that MI is effective in the treatment of heavy or harmful substance use for adolescents and adults across a variety of treatment settings (Barnett et al., 2012; Jensen et al., 2011; VanBuskirk & Wetherell, 2014), but effect sizes vary and therapist characteristics can have large effects (Miller & Moyers, 2015). MI has several core components that are thought to be important to behavior change. These include the “spirit” and specific skills and processes which are engaged to help move people towards change. The “spirit” is the relational component and is characterized by partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation of the patient’s experiences and perspectives. The specific skills, or technical component of MI, include open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries. The four possible processes engaged during MI, include engaging the patient, focusing the conversation, evoking a person’s motivations and arguments in favor of change, and planning for change (e.g., creating a change plan and anticipating obstacles to change; Miller & Rollnick, 2013).

MI has been often studied in the mechanisms of behavior change research literature. There is evidence for therapist-guided changes of in-session patient language (e.g., using language that upholds the status quo [“sustain talk”] versus language focused on behavior change [“change talk”]) and therapist relational skills as hypothesized mechanisms of behavior change, but these do not map onto established AUD etiologic or maintenance mechanisms (Hartzler et al., 2011; Longabaugh et al., 2013; Magill et al., 2019; Magill & Hallgren, 2019; Maisto et al., 2015; Villarosa-Hurlocker et al., 2019).4 Despite this, we have several hypotheses about which mechanisms of behavior change in MI might overlap with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. As described by Ladd and colleagues (2021), MI may target delay and probability discounting (reward: reward discounting in Table 1) by guiding patients to consider the costs and benefits of drinking and whether the choice to drink is aligned with their long term goals. MI may also help patients consider whether their behaviors are consistent with their values, which may help patients choose substance-free alternatives, even if delayed or uncertain. Like other treatments described here, these features of MI may serve to improve self-awareness. Additionally, MI may modify mechanisms such as positive (reward: positive expectancies) and negative expectancies (negative valence & emotionality: negative expectancies), automaticity (reward: habit), inability to abstain (cognitive control: compulsive use), lack of planning (cognitive control: conscientiousness), and lack of perseverance (cognitive control: conscientiousness). MI, although frequently evaluated in isolation for the purposes of clinical trials, is often combined with other therapeutic modalities including those previously discussed. In such instances, MI may be used as a tool to engage the patient in a collaborative discussion and increase their readiness to change prior to engaging in another intervention such as medication or behavioral interventions (Bien et al., 1993; Douaihy et al., 2014; Miller, 2004). When MI is joined with other skills and intervention targets, it may cover a broader range of AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms.

Pharmacological Treatments

The primary Food and Drug Administration approved pharmacological treatments for alcohol use and AUD are disulfiram, naltrexone (injectable and oral formulations), and acamprosate (Litten et al., 2005; Ray et al., 2019).5 Disulfiram (Antabuse) impacts the metabolism of alcohol and results in a buildup of acetaldehyde, causing a rapid onset of symptoms such as flushing, nausea, and heart palpitations when one consumes alcohol. Although generally considered effective in supporting abstinence among those who are highly motivated to abstain or who are supported in abstinence, disulfiram is less often prescribed given its potentially serious side effects coupled with data to suggest that the best outcomes require supervised administration, the goal of abstinence, and high adherence (Allen & Litten, 1992; Seneviratne & Johnson, 2015; Skinner et al., 2014). Disulfiram results in associative pairing of alcohol use and adverse reactions likely engages operant learning processes, potentially impacting the several AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. For example, disulfiram may decrease positive (reward: positive expectancies) and increase negative expectancies (negative valence & emotionality: negative expectancies) about use as well as impact the likelihood or strength of enhancement motivations (reward: positive emotionality).

Naltrexone is an antagonist that works by inhibiting mu-opioid receptors. When a person drinks alcohol while taking naltrexone, they do not experience (or experience less) positive effects from alcohol, making alcohol less rewarding and thus resulting in decreases in drinking (Maisel et al., 2013). In general, naltrexone is more efficacious in reducing heavy drinking than promoting abstinence when compared to placebo, but effect sizes vary considerably (Del Re et al., 2013; Feinn & Kranzler, 2005; Litten et al., 2005; Maisel et al., 2013; Witkiewitz, Litten, et al., 2019). The proposed mechanisms of change for naltrexone that overlap with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms include incentive salience/craving (reward: incentive salience), positive (reward: positive expectancies) and negative expectancies (negative valence & emotionality: negative expectancies), and enhancement motivations (reward: positive emotionality). Indeed, naltrexone reduces craving (Maisel et al., 2013), potentially by decreasing cue reactivity via extinction (Ooteman et al., 2007; Sinclair, 2001). Craving has also been a well-studied mechanism through which naltrexone works to reduce alcohol use. Additional research shows that naltrexone may be more effective for those who drink alcohol for the rewarding effects (and less so for relief of negative affect) (Votaw et al., 2022; Witkiewitz, Roos, et al., 2019). Although this work suggests reward drinking is a moderator, it may also be true that those high in reward drinking exhibit mechanistic dysfunction related to positive and negative expectancies (e.g., expecting drinking to be very rewarding and not at all punishing) and enhancement motivations (e.g., drinking to feel more sociable) that may be regulated with naltrexone use, thus decreasing use.

Acamprosate is most effective for preventing a return to heavy drinking among people who are abstinent, rather than helping people to reduce their drinking (Maisel et al., 2013; Witkiewitz, Litten, et al., 2019). Heavy drinking and withdrawal are thought to cause disruptions to the balance between neuronal excitation (glutamergic) and inhibition (GABAergic). Although acamprosate’s pharmacological mechanism is unclear, some experts suggest that it restores homeostasis by stabilizing NMDA-mediated glutamergic neurotransmission (Akbar et al., 2018). Research shows that acamprosate may be more effective in reducing heavy drinking for those who drink for relief purposes (e.g., to relieve negative affect) (Roos, Mann, et al., 2017). Although this work suggests relief drinking is a moderator, acamprosate may result in behavior change by reducing negative emotionality (negative valence & emotionality: negative emotionality) at the trait level (negative valence & emotionality: negative emotionality) and during withdrawal (negative valence & emotionality: withdrawal-related negative emotionality), which may serve as an associative cue for alcohol use among those high in relief drinking. Theoretically, acamprosate my also then reduce negative affect-related urgency (cognitive control: response inhibition). There is mixed evidence regarding whether acamprosate impacts drinking by reducing craving (reward: incentive salience; see Seneviratne & Johnson, 2015 for a discussion) and cue reactivity (reward: incentive salience; Kiefer & Mann, 2010; Ooteman et al., 2007) and future research is needed on potential mechanisms.

Discussion

This brief review suggests there is mixed empirical support for mechanisms of behavior change in common AUD treatments that overlap with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms identified by the ETOH Framework. The review identified many areas of potential overlap between the two types of mechanisms, although much of the overlap identified was hypothesized rather than supported by empirical data. Nonetheless, the available empirical findings and theoretical hypotheses offer several important future directions and highlight the need for continued research on how to strengthen AUD interventions.

This brief review suggests that treatments differ in their coverage of AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. For example, CBT for AUD is hypothesized to overlap with many, if not most, of the ETOH etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. In comparison, contingency management, and most of the medications for AUD, overlap with fewer mechanisms. It is possible that treatments are being incorrectly applied to all people (perhaps for practical purposes like therapist training or insurance billing), when we know there are likely individual differences that drive effectiveness for a given person. For example, a person whose AUD is driven by negative valence and emotionality may not benefit as much from contingency management as from a mindfulness-based treatment whose mechanisms of behavior change largely overlap with negative valence and emotionality. Such hypotheses can and should be tested and the current review provides guidance on potential mechanisms to further explore in the pursuit of advancing precision medicine efforts in AUD. In the absence of such data, it may be possible (although perhaps not always feasible or cost/time effective) to combine treatment approaches to ensure more coverage of possible etiologic and maintenance mechanisms in the treatment of AUD. However, combining treatments as a way to improve efficacy may not be this straightforward given some research to suggest that combined psychosocial and pharmacological treatments (which may provide more coverage of mechanisms) is not superior to either treatment alone for various treatment outcomes (e.g., Anton et al., 2006). It is also the case that combination treatments may tend to cover largely overlapping etiologic and maintenance mechanisms, offering little incremental coverage of mechanisms when used in combination.

Some etiologic and maintenance mechanisms are targeted by similar treatments. For example, both CBT for AUD and mindfulness-based addiction treatments are thought to target AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms related to cognitive control (e.g., urgency, lack of planning). If empirical support for overlapping mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatments and AUD etiology and maintenance can be established for specific treatments, this overlap may help identify potentially efficacious treatments for people with AUD who have dysregulation in such mechanisms. For example, if CBT for AUD and mindfulness-based addiction treatments both decrease urgency, this suggests that the two treatments may have common mechanisms of behavior change. Assuming these two treatments are equivalent in reducing urgency, patients with an AUD characterized primarily by urgency may benefit from either treatment. Perhaps more practically, the treatment that is the briefest, most cost effective, or available in the clinic may be chosen for that patient without concerns about jeopardizing outcomes.

Identifying common components across treatments, both within and across different forms of psychopathology, is consistent with efforts to advance individualized modular treatment approaches within and across specific diagnoses (e.g., Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders). Although modules tend to be selected based on pre-treatment factors like presenting symptoms (often based on DSM diagnostic criteria which have important limitations) or treatment moderators like individual sociodemographic characteristics (Lorenzo-Luaces et al., 2021), this approach might easily be extended to etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. Especially as we improve our ability to measure such mechanisms. In practice, this would look like choosing a given treatment module based on a person’s profile of dysfunction (i.e., the primary etiologic and maintenance mechanisms implicated in their AUD), perhaps through the use of intensive repeated measure data collection prior to therapy combined with person-specific factor analysis and dynamic factor modeling to select a treatment (Fisher et al., 2019). Such a modular and data-driven approach to treatment, if it could be implemented easily in clinical practice, could increase the effectiveness of AUD treatment.

The current brief review fails to include many other types of AUD treatments (e.g., substance-free activity sessions) and mutual help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous)6. However, there may not be clearly identified mechanisms of behavior change in these approaches, either (e.g., Witkiewitz et al., 2022). Thus, we call for continued attention to mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatment, especially those that may be implicated in the etiology or maintenance of AUD. Additional research should move beyond mediation to evaluate the other features of a mechanism as outlined by Kazdin and Nock (2003), for example, or the approaches outlined by Witkiewitz and colleagues (2022), such as time-varying effect or mixture modeling. An important future direction may be to target individual components of a treatment rather than the whole treatment itself when evaluating possible mechanisms of behavior change. This may help further identify which components demonstrate which mechanisms of change, providing a more specific test of mechanisms (Magill et al., 2020).

We are aware that this discussion fails to consider the role of the social or environmental contexts in which AUDs develop (or are maintained) and in which treatments occur. It surely is not as straightforward as targeting specific AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms with treatments that have overlapping mechanisms of behavior change because of social and environmental influences (e.g., social support, systemic racism, economic resources). For example, although a person’s profile of dysregulation related to AUD may consist of elevated negative affect and poor coping skills, traditional treatment components that lead to particular mechanisms of behavior change, such as coping skills training in CBT, may only be effective in specific contexts. If an individual whose alcohol use is primarily driven by negative affect also experiences associated with chronic housing instability and food insecurity, then focusing on coping skills training, alone, may be insufficient for changing alcohol use (Collins et al., 2015). Such an individual may not benefit in the absence of other supports for decreasing negative affect-driven alcohol use (e.g., stable housing and nutritional support) even though coping skills as a mechanism of behavior change overlaps with the main AUD maintenance mechanism driving their use (i.e., negative affect). Relatedly, the salience of a particular etiologic or maintenance mechanism in AUD may differ across people based on individual, social, or environmental factors. In this case, although two people with AUD may have dysfunction in the same etiologic mechanisms, which is most important to address may vary by person. We refer interested readers to Roos and Witkiewitz (2017) which provides an example of how contextual factors may impact mechanisms of behavior change.

This brief review discusses overlapping mechanisms of behavior change in AUD treatment and AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms; an overlap that has been largely neglected to date. Still, this review is relatively broad and the research in this area is lacking. Thus, we call for more in-depth and systematic empirical investigations of such overlap, potentially within a given treatment or within ETOH levels (e.g., subdomain level). Many challenges exist in rigorously testing mechanisms of behavior change, including practical and methodological challenges. Yet, some mechanisms of behavior change, although not related to AUD etiologic or maintenance mechanisms, have been successfully identified in SUD treatment (Witkiewitz et al., 2022). Thus, we call for mechanism of behavior change researchers and funding agencies to increase their attention to those behavior change mechanisms that overlap with AUD etiologic and maintenance mechanisms as one potential way make progress in improving AUD treatment outcomes.

Public Significance Statement:

This review highlights the overlap between processes that a) cause and maintain an alcohol use disorder and b) cause behavior change in alcohol use disorder treatment. By leveraging this overlap between processes, we may be able to better identify treatment targets and improve the efficacy of existing treatments.

Acknowledgments

Investigator effort was partially supported by K08AA030301 (PI: Boness) and R01AA022328 (PI: Witkiewitz).

Appendix A: Glossary of ETOH Superdomain, Domain, and Subdomain Definitions per Boness et al., 2021

ETOH Framework:

The Etiologic, Theory-based, Ontogenetic, Hierarchical Framework of Alcohol Use Disorder is a framework that organizes key alcohol use disorder etiologic and maintenance mechanisms. The mechanisms are organized by broader superdomains at the highest level (reward, cognitive control, and negative valence & emotionality) which then become increasingly more specific at their lower levels, including the domain, subdomain, and components levels (see Boness et al. 2021 for more detail).

Reward Superdomain:

Includes processes primarily responsible for responses to positive motivational situations or contexts, such as reward expectancies, consummatory behavior, and reward/habit learning.

Positive expectancies: The expectation regarding how positive a given outcome or behavior, such as alcohol use, will be.

Reward sensitivity: The tendency to detect, pursue, learn from, and experience pleasure from positive stimuli.

Positive emotionality: A tendency towards experiencing positive emotions.

Incentive salience: A motivational property whereby alcohol- and drug-related cues (i.e., conditioned stimuli), such as being in a bar in the case of AUD, become increasingly rewarding with repeated exposure.

(Reward) Discounting: A broad concept that has sometimes been described as how much value a given reinforcer loses as a function of a manipulated variable, such as size or probability of the reward and time.

Habit: A consequence of reward learning whereby alcohol or drug use becomes more ingrained and automatic as well as less susceptible to voluntary control and decision making.

Cognitive Control Superdomain:

Broadly represents mechanisms traditionally considered a part of executive functioning.

Compulsivity: Perseveration in responding despite adverse consequences.

Compulsive use: Using alcohol or other substances despite adverse consequences.

Impulsivity: A tendency to act without forethought or effortful control. Conceptualized as a precursor to compulsivity.

Conscientiousness: A broad, hierarchically organized personality trait that reflects tendencies towards cautiousness, dutifulness, and planfulness, and contains narrower components such as self-control, deliberation, and order, among others

Response inhibition: The ability to suppress dominant, automatic, or prepotent responses or a tendency toward immediate action that occurs with diminished forethought and is out of context with the current demands of one’s environment.

Negative Valence & Emotionality Superdomain:

Encompasses systems responsible for responses to aversive situations or context, such as fear, anxiety, and loss.

Punishment sensitivity: A reduced sensitivity to the aversive effects of alcohol (e.g., flushing or hangover)

Coping: The ways in which individuals manage negative emotions and involves complex cognitive processes (e.g., appraisal) and behaviors in response to stress or problems.

Negative emotionality: a negative mood state that includes alexithymia, anxiety, irritability, and depression.

Negative expectancies: beliefs people hold about the likelihood of experiencing negative effects from alcohol.

Footnotes

None of these ideas have been disseminated to date. This work was not preregistered.

Assuming mediators are akin to mechanisms is an often made mistake in the literature (Huebner & Tonigan, 2007; Longabaugh & Magill, 2011; Witkiewitz et al., 2022).

Although we focus on AUD specifically, many of these mechanisms are also implicated in other substance use disorders.

There may be mechanisms of behavior change through which AUD treatments work that are not in the ETOH model (e.g., self-efficacy, motivation to change) and these are not included in the current discussion. For those readers interested in a more general overview of mechanisms of behavior change in substance use disorder treatments we refer them to Witkiewitz and colleagues (2022). Further, it is important to acknowledge that treatments intended to address other forms of psychopathology may also be relevant and useful for targeting specific etiologic and maintenance mechanisms in AUD. However, this is not the focus of the current review.

There may be some additional mechanisms of change in MI that are especially relevant to underage young adult heavy drinkers (Magill et al., 2017), but such mechanisms are not implicated in the etiology or maintenance of AUD per the ETOH Framework.

Although there exist other medications that are used specifically to treat alcohol withdrawal or are used off-label to treat AUD (e.g., ondansetron, topiramate), we do not cover those here due to the scope of our brief review (see Witkiewitz et al., 2022, Ray et al. 2019, and Akbar et al., 2018 for discussions).

See Ray and colleagues (2019) for a more comprehensive overview of treatments.

References

- Akbar M, Egli M, Cho Y-E, Song B-J, & Noronha A (2018). Medications for Alcohol Use Disorders: An Overview. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 185, 64–85. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Litten RZ (1992). Techniques to Enhance Compliance with Disulfiram. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(6), 1035–1041. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, COMBINE Study Research Group, for the. (2006). Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence: The COMBINE Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 295(17), 2003. 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E, Sussman S, Smith C, Rohrbach LA, & Spruijt-Metz D (2012). Motivational Interviewing for adolescent substance use: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 37(12), 1325–1334. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Tidey J, Murphy JG, Swift R, & Colby SM (2011). Contingency management for alcohol use reduction: A pilot study using a transdermal alcohol sensor. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 391–399. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, & Tonigan JS (1993). Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction, 88(3), 315–336. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00820.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Votaw V, Schwebel FJ, Moniz-Lewis DIK, McHugh RK, & Witkiewitz K (2022). An Evaluation of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use: An Application of Tolin’s Criteria for Empirically Supported Treatments [Preprint]. Open Science Framework. 10.31219/osf.io/rbx8s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Watts AL, Moeller KN, & Sher KJ (2021). The Etiologic, Theory-Based, Ontogenetic Hierarchical Framework of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Translational Systematic Review of Reviews. Psychological Bulletin. 10.31219/osf.io/bscuh [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Dillworth TM, Chawla N, Simpson TL, Ostafin BD, Larimer ME, Blume AW, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (2006). Mindfulness meditation and substance use in an incarcerated population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 343–347. 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 847–861. 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Jones CB, Hoffmann G, Nelson LA, Hawes SM, Grazioli VS, Mackelprang JL, Holttum J, Kaese G, Lenert J, Herndon P, & Clifasefi SL (2015). In their own words: Content analysis of pathways to recovery among individuals with the lived experience of homelessness and alcohol use disorders. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 27, 89–96. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re A, Maisel N, Blodgett J, & Finney J (2013). The declining efficacy of naltrexone pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders over time: A multivariate meta-analysis. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(6), 1064–1068. 10.1111/acer.12067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaihy AB, Kelly TM, & Gold MA (Eds.). (2014). Motivational interviewing: A guide for medical trainees. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feinn R, & Kranzler HR (2005). Does effect size in naltrexone trials for alcohol dependence differ for single-site vs. Multi-center studies? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(6), 983–988. 10.1097/01.alc.0000171061.03686.bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AJ, Bosley HG, Fernandez KC, Reeves JW, Soyster PD, Diamond AE, & Barkin J (2019). Open trial of a personalized modular treatment for mood and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 69–79. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Boettiger CA, & Howard MO (2010). Mindfulness Training Modifies Cognitive, Affective, and Physiological Mechanisms Implicated in Alcohol Dependence: Results of a Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 42(2), 177–192. 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Roberts-Lewis A, Tronnier CD, Graves R, & Kelley K (2016). Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement versus CBT for co-occurring substance dependence, traumatic stress, and psychiatric disorders: Proximal outcomes from a pragmatic randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 7–16. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Witkiewitz K, Villarroel N, & Donovan D (2011). Self-Efficacy Change as a Mediator of Associations between Therapeutic Bond and One-Year Outcomes in Treatments for Alcohol Dependence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 269–278. 10.1037/a0022869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, & Petry NM (1999). Contingency Management. 23(2), 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AB (1965). The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 58(5), 295–300. 10.1177/003591576505800503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, & Ott U (2011). How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner RB, & Tonigan JS (2007). The Search for Mechanisms of Behavior Change in Evidence-Based Behavioral Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorders: Overview. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(s3), 1s–3s. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Aylward BS, Craig JT, Sorell DM, & Steele RG (2011). Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 433–440. 10.1037/a0023992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (2007). Mediators and Mechanisms of Change in Psychotherapy Research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 1–27. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Nock MK (2003). Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations: Delineating mechanisms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(8), 1116–1129. 10.1111/1469-7610.00195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, & Mann K (2010). Acamprosate: How, Where, and for Whom Does it Work? Mechanism of Action, Treatment Targets, and Individualized Therapy. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 16(19), 2098–2102. 10.2174/138161210791516341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD (2019). Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders: A Summary of the Evidence and Potential Mechanisms of Behavior Change. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 42(3), 465–478. 10.1007/s40614-019-00205-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Babuscio T, & Carroll KM (2010). Quality versus quantity: Acquisition of coping skills following computerized cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders: Quality versus quantity of coping skills. Addiction, 105(12), 2120–2127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03076.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korecki JR, Schwebel FJ, Votaw VR, & Witkiewitz K (2020). Mindfulness-based programs for substance use disorders: A systematic review of manualized treatments. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 51. 10.1186/s13011-020-00293-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd BO, Murphy JG, & Borsari B (2021). Integration of Motivational Interviewing and Behavioral Economic Theories to Enhance Brief Alcohol Interventions: Rationale and Preliminary Examination of Client Language. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(1), 90–98. 10.1037/pha0000363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SP, & Sher KJ (2015). Limits of Current Approaches to Diagnosis Severity Based on Criterion Counts: An Example With DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 819–835. 10.1177/2167702614553026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, & Park-Lee E (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Egli M, Heilig M, Cui C, Fertig JB, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Moss H, Huebner R, & Noronha A (2012). Medications development to treat alcohol dependence: A vision for the next decade: Medications development. Addiction Biology, 17(3), 513–527. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00454.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Fertig J, Mattson M, & Egli M (2005). Development of medications for alcohol use disorders: Recent advances and ongoing challenges. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs, 10(2), 323–343. 10.1517/14728214.10.2.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Falk DE, Reilly M, Fertig JB, & Koob GF (2015). Heterogeneity of Alcohol Use Disorder: Understanding Mechanisms to Advance Personalized Treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(4), 579–584. 10.1111/acer.12669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, & Magill M (2011). Recent Advances in Behavioral Addiction Treatments: Focusing on Mechanisms of Change. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(5), 382–389. 10.1007/s11920-011-0220-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M, Morgenstern J, & Huebner R (2013). Mechanisms of Behavior Change in Treatment for Alcohol and Other Drug Use Disorders. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Luaces L, Peipert A, De Jesús Romero R, Rutter LA, & Rodriguez-Quintana N (2021). Personalized Medicine and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for Depression: Small Effects, Big Problems, and Bigger Data. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 14(1), 59–85. 10.1007/s41811-020-00094-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Colby SM, Orchowski L, Murphy JG, Hoadley A, Brazil LA, & Barnett NP (2017). How Does Brief Motivational Intervention Change Heavy Drinking and Harm Among Underage Young Adult Drinkers? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(5), 447–458. 10.1037/ccp0000200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Hallgren KA (2019). Mechanisms of behavior change in motivational interviewing: Do we understand how MI works? Current Opinion in Psychology, 30, 1–5. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Kiluk BD, McCrady BS, Tonigan JS, & Longabaugh R (2015). Active Ingredients of Treatment and Client Mechanisms of Change in Behavioral Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorders: Progress 10 Years Later. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(10), 1852–1862. 10.1111/acer.12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk B, Hoadley A, Bernstein M, Tonigan JS, & Carroll K (2019). A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders: Treatment Efficacy by Contrast Condition. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 87(12), 1093–1105. aph. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Tonigan JS, Kiluk B, Ray L, Walthers J, & Carroll K (2020). The search for mechanisms of cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: A systematic review. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 131, 103648. 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, & Finney JW (2013). Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: When are these medications most helpful?: Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate. Addiction, 108(2), 275–293. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Roos CR, O’Sickey AJ, Kirouac M, Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, & Witkiewitz K (2015). The Indirect Effect of the Therapeutic Alliance and Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy on Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Problems in Project MATCH. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(3), 504–513. 10.1111/acer.12649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS (2017). Alcohol Use Disorders: Treatment and Mechanisms of Change. In McKay D, Abramowitz JS, & Storch EA (Eds.), Treatments for Psychological Problems and Syndromes (pp. 235–247). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9781118877142.ch16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, & Otto MW (2010). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 511–525. 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (2004). Combined Behavioral Intervention: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. [COMBINE Monograph Series, (Vol.1) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Public Health Service, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services.]. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Moyers TB (2015). The forest and the trees: Relational and specific factors in addiction treatment: Forest and trees. Addiction, 110(3), 401–413. 10.1111/add.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, & Longabaugh R (2000). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: A review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction, 95(10), 1475–1490. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951014753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, & Gex KS (2021). Individual Behavioral Interventions to Incentivize Sobriety and Enrich the Natural Environment with Appealing Alternatives to Drinking. In Tucker JA & Witkiewitz K (Eds.), Dynamic Pathways to Recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder (1st ed., pp. 179–199). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781108976213.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK (2007). Conceptual and Design Essentials for Evaluating Mechanisms of Change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(s3), 4s–12s. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooteman W, Koeter MWJ, Verheul R, Schippers GM, & van den Brink W (2007). The effect of naltrexone and acamprosate on cue-induced craving, autonomic nervous system and neuroendocrine reactions to alcohol-related cues in alcoholics. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(8), 558–566. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2000). A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58(1–2), 9–25. 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00071-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, & Kranzler HR (2000). Give them prizes and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 250–257. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfund RA, Ginley MK, Rash CJ, & Zajac K (2022). Contingency management for treatment attendance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 133, 108556. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfund R, Ginley MK, Boness CL, Zajac K, Rash C, & Witkiewitz K (2021). Evaluation of Contingency Management (CM) for Substance Use Disorder (SUD) [Preprint]. Open Science Framework. 10.31219/osf.io/zme9n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Bujarski S, Grodin E, Hartwell E, Green R, Venegas A, Lim AC, Gillis A, & Miotto K (2019). State-of-the-art behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(2), 124–140. 10.1080/00952990.2018.1528265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Carroll KM, Nich C, Frankforter T, & Kiluk BD (2020). Short- and long-term changes in substance-related coping as mediators of in-person and computerized CBT for alcohol and drug use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 212, 108044. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Maisto SA, & Witkiewitz K (2017). Coping mediates the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol use disorder among out-patient clients in Project MATCH when dependence severity is high. Addiction, 112(9), 1547–1557. 10.1111/add.13841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Mann K, & Witkiewitz K (2017). Reward and relief dimensions of temptation to drink: Construct validity and role in predicting differential benefit from acamprosate and naltrexone: Reward and relief temptation. Addiction Biology, 22(6), 1528–1539. 10.1111/adb.12427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, & Witkiewitz K (2016). Adding tools to the toolbox: The role of coping repertoire in alcohol treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(7), 599–611. 10.1037/ccp0000102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, & Witkiewitz K (2017). A contextual model of self-regulation change mechanisms among individuals with addictive disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 117–128. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne C, & Johnson BA (2015). Advances in Medications and Tailoring Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 37(1), 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair JD (2001). Evidence about the use of naltrexone and for different ways of using it in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36(1), 2–10. 10.1093/alcalc/36.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, & Aubin H-J (2014). Disulfiram Efficacy in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e87366. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Budney AJ, & Bickel WK (2013). A Developmental Perspective on Neuroeconomic Mechanisms of Contingency Management. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 27(2), 403–415. 10.1037/a0028748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuskirk KA, & Wetherell JL (2014). Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(4), 768–780. 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, O’Sickey AJ, Houck JM, & Moyers TB (2019). Examining the influence of active ingredients of motivational interviewing on client change talk. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 96, 39–45. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Mann K, Kranzler HR, Roos CR, Nakovics H, & Witkiewitz K (2022). Examining a brief measure and observed cutoff scores to identify reward and relief drinking profiles: Psychometric properties and pharmacotherapy response. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 232, 109257. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield J. c. (1992). The Concept of Mental Disorder: On the Boundary Between Biological Facts and Social Values. American Psychologist, 47(3), 373–388. 10.1037/0003-066X.47.3.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S, Douglas H, & Hsu SH (2013). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance craving. Addictive Behaviors, 38(2), 1563–1571. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S, Harrop EN, Douglas H, Enkema M, & Sedgwick C (2014). Mindfulness-Based Treatment to Prevent Addictive Behavior Relapse: Theoretical Models and Hypothesized Mechanisms of Change. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(5), 513–524. 10.3109/10826084.2014.891845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Litten RZ, & Leggio L (2019). Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Science Advances, 5(9), eaax4043. 10.1126/sciadv.aax4043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, & Walker D (2005). Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19(3), 211–228. 10.1891/jcop.2005.19.3.211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Pfund RA, & Tucker JA (2022). Mechanisms of Behavior Change in Substance Use Disorder With and Without Formal Treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18(1), annurev-clinpsy-072720–014802. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072720-014802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Mann K, & Kranzler HR (2019). Advancing Precision Medicine for Alcohol Use Disorder: Replication and Extension of Reward Drinking as a Predictor of Naltrexone Response. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(11), 2395–2405. 10.1111/acer.14183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Roos CR, Tofighi D, & Van Horn ML (2018). Broad Coping Repertoire Mediates the Effect of the Combined Behavioral Intervention on Alcohol Outcomes in the COMBINE Study: An Application of Latent Class Mediation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 199–207. 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]