Abstract

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) protect against invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among vaccinees. However, at population level, this protection is driven by indirect effects. PCVs prevent nasopharyngeal acquisition of vaccine-serotype (VT) pneumococci, reducing onward transmission. Each disease episode is preceded by infection from a carrier, so vaccine impacts on carriage provide a minimum estimate of disease reduction in settings lacking expensive IPD surveillance. We documented carriage prevalence and vaccine coverage in two settings in Nigeria annually (2016–2020) following PCV10 introduction in 2016. Among 4,684 rural participants, VT carriage prevalence fell from 21 to 12% as childhood (<5 years) vaccine coverage rose from 7 to 84%. Among 2,135 urban participants, VT carriage prevalence fell from 16 to 9% as uptake rose from 15 to 94%. Within these ranges, carriage prevalence declined with uptake. Increasing PCV10 coverage reduced pneumococcal infection at all ages, implying at least a comparable reduction in IPD.

Subject terms: Bacterial infection, Preventive medicine, Epidemiology, Vaccines

Nigeria has the highest incidence of pneumococcal disease in Africa and introduced the 10-valent pneumococcal vaccine for infants between 2014 and 2016. Here, the authors conduct repeated cross-sectional surveys to analyse the impact of the vaccination campaign on pneumococcal carriage and serotype distribution.

Introduction

In 2015, pneumococcal disease was estimated to cause ~300,000 deaths globally among children aged 1–59 months. Over 50% of these deaths occurred in Africa, and Nigeria alone accounted for nearly 50,000 of these pneumococcal deaths1. Between 2014 and 2016, in three geographically distinct phases, Nigeria introduced the 10-valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV10) in a three-dose schedule for infants aged 6, 10 and 14 weeks, without a catch-up campaign. Although PCV is the most expensive vaccine programme in the Nigerian portfolio, the country could not evaluate the impact of the vaccine programme on invasive disease or pneumonia due to lack of surveillance data.

Every episode of pneumococcal disease is preceded by infection from another infected person, normally a nasopharyngeal carrier2. Young children are the main reservoirs for carriage and have the highest number of effective contacts3,4. Consequently, a reduction in carriage prevalence among young children is likely to reduce onward transmission and the incidence of disease proportionately across the population. Among vaccinated children, PCVs provide direct protection against both acquiring carriage and progressing to invasive disease following carriage of vaccine-serotypes (VTs)2. At the population level, PCVs provide indirect protection, regardless of vaccine status, by reducing everyone’s exposure to new infections from VTs. This indirect effect is driven by the direct protection against carriage among vaccinees5,6. As vaccine coverage increases, VT carriage prevalence declines linearly due to direct protection among vaccinees and non-linearly due to indirect protection from the consequences of reduced VT transmission in the whole population2,5.

In real-world settings, the indirect effects of PCVs account for most of the vaccine programme impact2,7. Consequently, some countries have tailored their PCV schedules to maximise indirect effects of a booster dose at the expense of marginal direct effects of additional primary doses in infancy. For example, in the UK, population protection is being achieved with only a single dose in infancy and a booster dose at 12 months8. A disadvantage of PCV introduction is replacement carriage by non-vaccine serotypes (NVTs) leading, to a varying extent, to serotype replacement disease9,10. However, in most settings, any increase in serotype replacement disease is small compared to the reduction in vaccine-type disease because non-vaccine types are generally less invasive10.

In the absence of robust IPD surveillance and given the strong anticipation of indirect protection following PCV10 introduction, we set out to evaluate the impact of the Nigerian PCV programme using carriage prevalence as an endpoint11. In Nigeria, among children aged <5 years who were studied immediately after PCV10 introduction, from a rural and an urban setting, VT pneumococci accounted for 52 and 64% of all carriage, respectively12. We conducted annual carriage and vaccination coverage surveys in these same two sites, for 4 years following PCV10 introduction. We assessed changes in the prevalence of overall carriage (i.e. all pneumococci), and VT and NVT carriage separately and explored the relationship between changes in vaccination uptake and changes in VT carriage prevalence.

Results

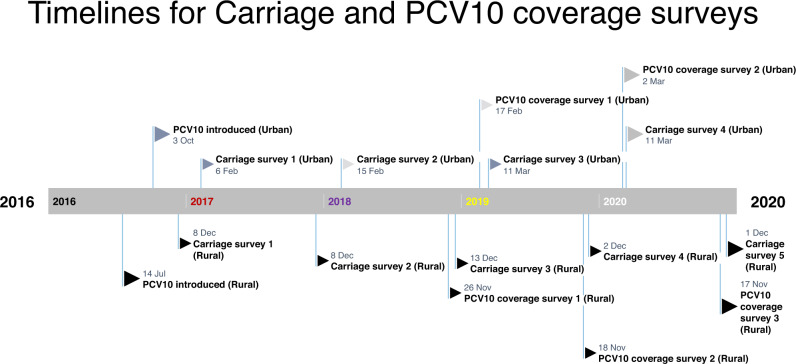

Including the baseline survey, reported above12, we conducted five annual carriage surveys in the rural and four in the urban sites (Fig. 1) and recruited 4684 and 3653 participants, respectively. In the rural and urban sites, the proportion of eligible residents who consented to participate varied from 60–98% and 63–99%, respectively, across the sampling age groups and surveys (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1. Timelines for surveys in the two sites.

For each site, surveys were conducted around the same time. Note PCV10 coverage surveys started from 2018 onwards.

Participants in the rural site resided in larger households and more commonly reported living with ≥2 children aged <5 years, using solid fuel for cooking, and having a cough or runny nose in the preceding two weeks compared to their counterparts in the urban site (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of study participants of the carriage surveys

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey 1 (2016) | Survey 2 (2017) | Survey 3 (2018) | Survey 4 (2019) | Survey 5 (2020) | |

| Kumbotso (rural) | |||||

| Total sample | 878 | 879 | 999 | 973 | 954 |

| Clinical historya | |||||

| Runny nose (%) | 714 (81) | 681 (77) | 900 (90) | 843 (87) | 727 (76) |

| Cough (%) | 450 (51) | 551 (63) | 687 (69) | 558 (57) | 487 (51) |

| Antibiotic use (%) | 65 (7) | 431 (49) | 510 (51) | 233 (24) | 202 (21) |

| Household composition | |||||

| Living with ≥2 aged <5 years (%) | 645 (73) | 469 (53) | 555 (56) | 619 (64) | 748 (78) |

| Sharing bed with ≥2 persons (%) | 729 (83) | 704 (80) | 882 (88) | 795 (82) | 857 (90) |

| Household cooking fuel | |||||

| Solid fuel (%) | 833 (95%) | 795 (90) | 959 (96) | 892 (92) | 850 (89) |

| Gas (%) | 12 (1%) | 19 (2) | 18 (2) | 38 (4) | 51 (5) |

| Kerosene (%) | 16 (2%) | 18 (2) | 5 (0.5) | 66 (0.6) | 3 (0.3) |

| Others (%) | 17 (2%) | 47 (5) | 17 (2) | 40 (4) | 46 (5) |

| Household sizeb | |||||

| All persons, median (IQR) | 9 (7–13) | 6 (3–10) | 6 (4–9) | 8 (6–10) | 9 (7–12) |

| Survey 1 (2017) | Survey 2 (2018) | Survey 3 (2019) | Survey 4 (2020) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakoto (urban) | |||||

| Total sample | 924 | 943 | 932 | 854 | N/A |

| Clinical historya | |||||

| Runny nose (%) | 238 (26) | 163 (17) | 106 (11) | 51 (6) | N/A |

| Cough (%) | 216 (23) | 122 (13) | 75 (8) | 32 (4) | N/A |

| Antibiotic use (%) | 145 (16) | 76 (8) | 39 (4) | 10 (1%) | N/A |

| Household composition | |||||

| Living with ≥2 aged <5 years (%) | 95 (10) | 81 (9) | 69 (7) | 53 (6) | N/A |

| Sharing bed with ≥2 persons (%) | 185 (20) | 212 (23) | 121 (13) | 121 (14) | N/A |

| Household cooking fuel | |||||

| Solid fuel (%) | 58 (6) | 38 (4) | 35 (4) | 11 (1) | N/A |

| Gas (%) | 326 (35) | 584 (62) | 713 (76) | 775 (91) | N/A |

| Kerosene (%) | 515 (56) | 238 (25) | 155 (17) | 29 (3) | N/A |

| Others (%) | 25 (3) | 83 (8) | 29 (3) | 39(5) | N/A |

| Household sizeb | |||||

| All persons, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | N/A |

aHistory of any of the symptoms in the 2 weeks preceding the interview date.

bIncluding the participant.

Carriage prevalence

Table 2 shows the crude and age-standardised carriage prevalence stratified by survey. Among the age-standardised results, overall pneumococcal carriage prevalence was consistently high across all ages in all surveys at the rural site. At both sites, overall pneumococcal carriage prevalence and NVT carriage prevalence were higher in children aged <5 years compared to persons aged ≥5 years; VT carriage prevalence was also higher in children aged <5 years in the baseline surveys at both sites. The crude carriage prevalence (by sampled ages) is also illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Crude and age-standardiseda prevalence (and 95% CI) of overall, non-vaccine serotype (NVT) and vaccine serotype (VT) pneumococcal carriage stratified by age group and survey in the rural site

| Overall carriage | VT carriage | NVT carriage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | N | Crude | Age-standardised | Crude | Age-standardised | Crude | Age-standardised |

| Kumbotso (rural) | |||||||

| All ages | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2016) | 872 | 74 (71–77) | 68 (65–71) | 26 (22–28) | 21 (18–24) | 48 (45–52) | 47 (43–51) |

| Survey 2 (2017) | 879 | 74 (71–77) | 71 (67–74) | 18 (16–21) | 16 (14–19) | 55 (52–59) | 54 (51–58) |

| Survey 3 (2018) | 999 | 77 (74–80) | 77 (74–79) | 16 (14–19) | 16 (13–18) | 60 (57–64) | 61 (58–64) |

| Survey 4 (2019) | 976 | 77 (74–79) | 74 (71–77) | 15 (13–17) | 13 (11–15) | 61 (59–65) | 60 (57–64) |

| Survey 5 (2020) | 953 | 78 (75–80) | 74 (71–77) | 14 (12–17) | 12 (10–14) | 63 (61–67) | 61 (58–65) |

| <5 years | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2016) | 296 | 92 (88–94) | 91 (88–94) | 42 (37–48) | 41 (35–46) | 50 (44–56) | 50 (45–56) |

| Survey 2 (2017) | 264 | 93 (89–95) | 92 (89–96) | 30 (25–36) | 30 (25–36) | 63 (57–68) | 62 (56–68) |

| Survey 3 (2018) | 304 | 93 (89–95) | 92 (90–95) | 25 (21–30) | 25 (20–30) | 68 (62–73) | 67 (62–72) |

| Survey 4 (2019) | 365 | 91 (88–94) | 91 (88–94) | 21 (17–26) | 22 (17–26) | 70 (65–75) | 69 (64–74) |

| Survey 5 (2020) | 333 | 89 (85–92) | 88 (84–91) | 22 (18–27) | 22 (18–27) | 67 (61–72) | 65 (60–71) |

| >5 years | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2016) | 576 | 65 (60–68) | 62 (58–66) | 17 (14–20) | 16 (13–19) | 48 (43–52) | 46 (42–50) |

| Survey 2 (2017) | 615 | 66 (62–64) | 65 (61–69) | 13 (11–16) | 13 (10–16) | 53 (49–56) | 52 (48–56) |

| Survey 3 (2018) | 695 | 70 (67–74) | 73 (69–76) | 13 (10–15) | 13 (11–16) | 57 (54–61) | 59 (55–63) |

| Survey 4 (2019) | 611 | 68 (64–71) | 69 (66–73) | 11 (9–14) | 11 (9–14) | 57 (53–61) | 58 (54–62) |

| Survey 5 (2020) | 620 | 72 (69–76) | 70 (66–74) | 10 (8–13) | 9 (7–11) | 62 (58–66) | 61 (57–64) |

aStandardised using the respective population structures of the two study sites taken from population models of the Nigerian census37.

Changes in carriage prevalence

Overall carriage prevalence in the total population (all ages combined) remained unchanged across the surveys, in both settings (Tables 2 and 3). However, in the rural site (Table 2), overall carriage prevalence increased significantly among persons aged ≥5 years (χ2 test for trend, p = 0.004), and in the urban site (Table 3), overall carriage prevalence declined significantly among children <5 years (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Crude and age-standardiseda prevalence of overall, non-vaccine serotype (NVT) and vaccine serotype (VT) pneumococcal carriage stratified by age group and survey in the urban site

| Overall carriage | VT carriage | NVT carriage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | N | Crude | Age-standardised | Crude | Age-standardised | Crude | Age-standardised |

| Pakoto (urban) | |||||||

| All ages | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2017) | 919 | 50 (47–53) | 40 (36–43) | 22 (19–24) | 16 (13–18) | 29 (25–31) | 24 (21–27) |

| Survey 2 (2018) | 941 | 52 (49–55) | 51 (47–54) | 15 (13–18) | 14 (12–17) | 37 (34–40) | 36 (33–39) |

| Survey 3 (2019) | 932 | 47 (44–50) | 44 (41–48) | 12 (10–14) | 11 (9–14) | 35 (32–38) | 33 (30–36) |

| Survey 4 (2020) | 851 | 40 (36–43) | 39 (36–42) | 9 (7–11) | 9 (6–10) | 31 (28–34) | 31 (28–34) |

| <5 years | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2017) | 335 | 78 (73–82) | 77 (72–81) | 38 (33–43) | 36 (31–42) | 40 (35–45) | 40 (35–45) |

| Survey 2 (2018) | 244 | 70 (64–76) | 70 (65–76) | 23 (18–29) | 23 (18–29) | 47 (41–53) | 47 (41–54) |

| Survey 3 (2019) | 243 | 70 (64–75) | 69 (63–75) | 19 (15–25) | 19 (14–24) | 51 (44–57) | 50 (43–56) |

| Survey 4 (2020) | 185 | 52 (45–59) | 53 (46–61) | 12 (8–17) | 12 (7–17) | 40 (33–47) | 41 (34–49) |

| ≥5 years | |||||||

| Survey 1 (2017) | 584 | 34 (31–38) | 32 (28–36) | 13 (10–15) | 12 (9–15) | 22 (19–25) | 20 (17–24) |

| Survey 2 (2018) | 697 | 46 (42–50) | 47 (43–50) | 12 (10–15) | 13 (10–15) | 34 (30–37) | 34 (30–38) |

| Survey 3 (2019) | 689 | 39 (36–43) | 40 (36–43) | 9 (7–12) | 10 (8–12) | 30 (26–33) | 29 (26–33) |

| Survey 4 (2020) | 666 | 36 (33–40) | 36 (33–39) | 8 (6–10) | 7 (5–9) | 29 (25–32) | 29 (25–32) |

aStandardised using the respective population structures of the two study sites taken from population models of the Nigerian census37.

In the total population VT carriage prevalence steadily declined from 21 to 12% (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001) in the rural site and from 16 to 9% (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001) in the urban site. In the total population VT carriage prevalence steadily declined from 21 to 12% (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001) in the rural site and from 16 to 9% (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001) in the urban site. Among the total population sample, there was a significant trend for an increase in NVT carriage over the survey years in the rural site (Chi squared test for trend p < 0.001) and but not in the urban site (Chi squared test for trend p = 0.36).

For both age groups, VT carriage declined significantly across surveys in at each site (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001 for all 4 trends). NVT carriage prevalence increased significantly in both age groups across surveys but only at the rural site (χ2 test for trend, p < 0.001).

Compared to the baseline survey, the adjusted age-standardised PR for VT carriage prevalence in the final survey was 0.52 and 0.53 (Table 4) among children <5 years and older persons, respectively, in Kumbotso (rural). The adjusted PRs were 0.31 and 0.60 among children <5 years and older persons, respectively, in Pakoto (urban). NVT carriage increased significantly in both age groups in Kumbotso, with adjusted PRs of 1.34 and 1.26 in children aged <5 years and persons ≥5 years, respectively. In Pakoto, serotype replacement carriage was significant only in those aged ≥5 years (adjusted PR 1.36, Table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence ratios (PR), and 95% CI, showing changes in overall, non-vaccine serotype (NVT), and vaccine serotype (VT) carriage stratified by age and site

| Overall carriage | VT carriage | NVT carriage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude PR | Adjusted age-standardised PRa | Crude PR | Adjusted age-standardised PRa | Crude PR | Adjusted age-standardised PRa | |

| PR for carriage in the final survey compared to the baseline surveyb | ||||||

| Kumbotso (rural)c | ||||||

| All ages | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.55 (0.45–0.67) | 0.52 (0.43–0.64) | 1.32 (1.22–1.44) | 1.30 (1.19–1.42) |

| <5 years | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | 1.34 (1.17–1.54) | 1.34 (1.17–1.54) |

| ≥5 years | 1.12 (0.97–1.28) | 1.06 (0.97–1.14) | 0.58 (0.43–0.78) | 0.53 (0.39–0.72) | 1.31 (1.18–1.46) | 1.26 (1.12–1.40) |

| Pakoto (urban)d | ||||||

| All ages | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) | 0.72 (0.65–0.80) | 0.40 (0.31–0.51) | 0.34 (0.26–0.45) | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) |

| <5 years | 0.67 (0.58–0.78) | 0.68 (0.58–0.79) | 0.32 (0.21–0.48) | 0.31 (0.20–0.48) | 1.01 (0.81–1.25) | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) |

| ≥5 years | 1.05 (0.91–1.22) | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) | 0.61 (0.44–0.86) | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) | 1.30 (1.07–1.58) | 1.36 (1.10–1.69) |

aAdjusted for symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in past 2 weeks, living with ≥2 children aged <5 years, and age-standardised to the respective age distribution of study sites.

bPR = prevalence ratios comparing each survey compared to the baseline (first) survey.

cFive surveys (2016–2020).

dFour surveys (2017–2020).

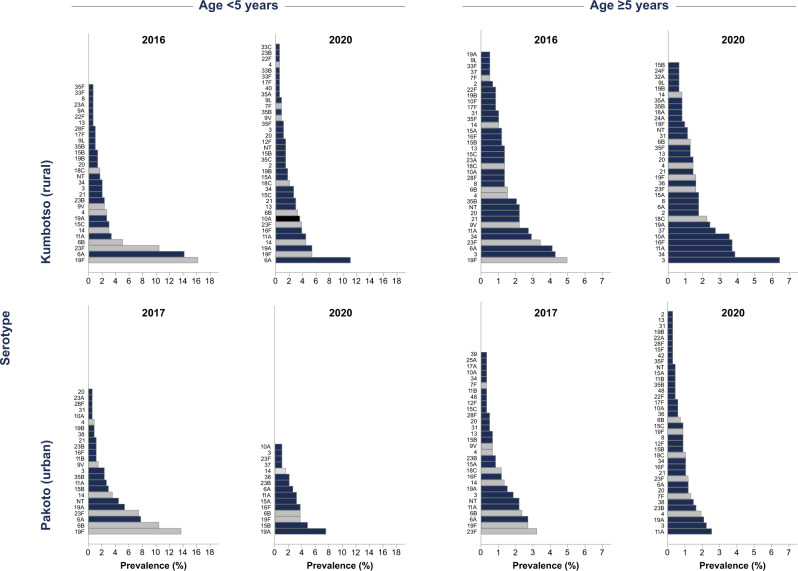

For children aged <5 years, the individual serotypes with the highest age-standardised prevalence in the final surveys were 6A (11.4%), 19F (5.5%) and 19A (5.4%), 11A (4.7%), 14, (4.4%) 16F (4.4%) and 23F (3.7%) in the rural site (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2); and 19A (7.4%), 15B (4.6%), 6B (4.0%), 19F (3.9%), and 16F (3.7%) in the urban site (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Among persons aged ≥5 years, in the rural site (Supplementary Table 4), the most prevalent serotypes in the final surveys were 3, 34, 11A, 16F and 10A; in the urban site, the most prevalent serotypes were 11A, 3, 19A, 4, 23B and 38 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5).

Fig. 2. Serotype-specific carriage prevalence per survey stratified by age group.

Distribution and ranking of serotypes in carriage (serotypes with >1 isolate) among children aged <5 years and persons ≥5 years by vaccine-type (greyscale bars – vaccine-serotypes, navy blue bars – non-vaccine serotypes) in the baseline and final surveys. Note the differences in scale in graphs by age.

In the rural site(Supplementary Tables 2 and 4), significantly increased prevalence odds (final vs baseline survey) were observed for serotypes 16F (OR 12.6) and 10A (11.6), among children aged <5 years, and for serotypes 19A (4.4), 16F (2.9), 10A (2.4), and 37(5.0) for persons aged ≥5 years. In the urban site (Supplementary Tables 3 and 5), NVT replacement was significant for serotypes 19A (OR 2.3), 15B (2.6) and 16F (5.0) in children aged <5 years; there was no significant increases in individual NVTs among persons aged ≥5 years.

We compared the carriage prevalence of serotypes included in different PCV formulations (Supplementary Table 7) in the final survey among children <5 years old. The total carriage prevalences of all serotypes contained in the Serum Institute of India 10-valent PCV (SII-PCV), 13-valent PCV (PCV13), 15-valent PCV (PCV15) and 20-valent PCV (PCV20) were 54%, 61%, 62% and 68%, respectively, in the rural site and 50%, 53%, 53% and 60%, respectively, in the urban site.

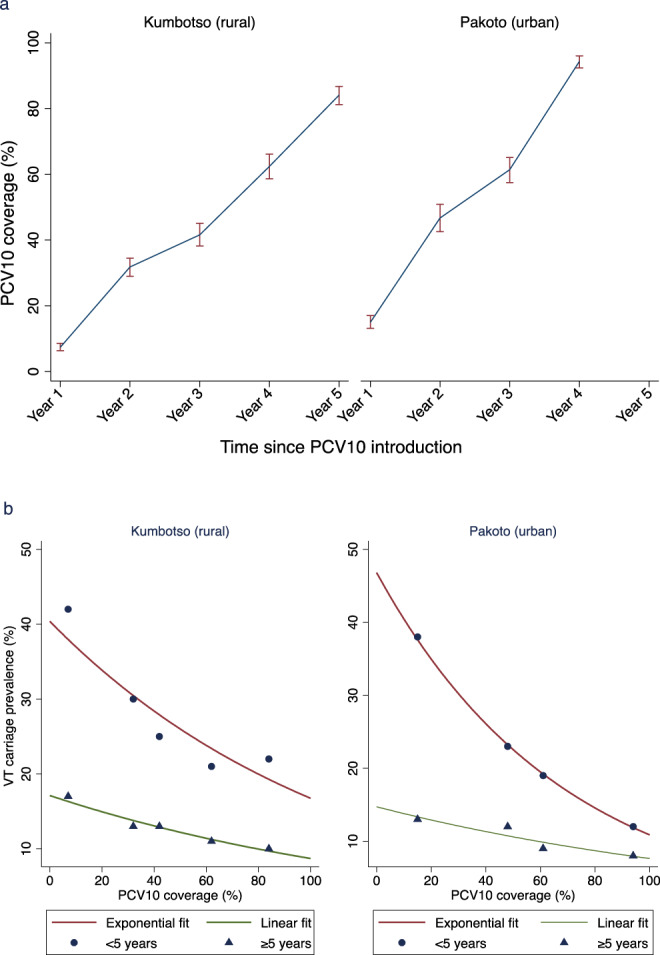

PCV10 vaccine coverage

We assessed the PCV10 vaccination status of 2165 children (aged <5 years) in the rural site and 1313 children in the urban site. We accepted either written evidence of vaccination or the caregiver’s recall. The average proportion of children for whom the caregivers had retained their vaccination card was 70% in the rural site (52% in 2018; 77% in 2019; and 90% in 2020) and 80% in the urban site (70% in 2019 and 91% in 2020). Figure 3A shows the annual proportions of children aged <5 years who had received at least two doses of PCV10. PCV10 coverage (≥2 doses) increased steadily from 7% in 2016 to 84% in 2020, in the rural site; and from 15% in 2017 to 94% in 2020, in the urban site.

Fig. 3. Coverage of PCV10 and its relationship to VT carriage.

a (top) Annual Coverage of two doses of PCV10 among children aged < 5 years. Year 1 represents the year of PCV10 introduction. PCV10 coverage values for Year 3 to Year 5 were assessed directly among 817, 655 and 693 children in Kumbotso, and for Year 3 and 4 among 652 and 661 children in Pakoto. PCV10 coverage values for Year 1 and Year 2 were estimated using a birth-cohort analysis of children observed during Years 3–5 (among 2165 and 1140 children in Kumbotso, and 1,313 and 568 children in Pakoto). Error bar = 95% confidence interval CI). b (bottom). Relationship between Vaccine serotype (VT) carriage prevalence and PCV10 coverage. Scatter graph of log-linear regression among children aged <5 years and linear regression among persons ≥5 years of VT carriage prevalence against PCV10 coverage for each of the 9 surveys, stratified by age of carrier and shown separately for the Kumbotso (rural) site and Pakoto (urban) site. The lines for children (aged <5 years) are exponential fits (log-linear regression) and the lines for the older persons (age ≥5 years) are arithmetic (linear regression). Values from the log-linear regression among children are exponentiated and shown here on the non-log (arithmetic) scale.

Relationship between PCV10 coverage and VT carriage

Within the range of PCV10 coverage observed in children, the ecological relationship between PCV10 coverage and the prevalence of VT carriage (Fig. 3B) shows a linear decline for older persons aged ≥5 years in both settings (gradient −0.09 (95% CI −0.13 to −0.04) in Kumbotso; −0.07 (95% CI −0.10 to −0.04) in Pakoto. For children aged <5 years, a log-linear model had a better fit to the data (Supplementary Fig. 3) which show a steep decline in VT carriage prevalence associated with a small increase in PCV coverage towards 20% followed by slower gains as coverage increases further.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the introduction of a new, expensive vaccine programme in Nigeria using an inexpensive proxy measure of impact, vaccine-type nasopharyngeal carriage. Over five years, in a rural setting (Kumbotso) in northern Nigeria, the proportion of children aged <5 years who were vaccinated increased from 7 to 84%. During the same period, the age-standardised population prevalence of VT carriage fell from 21 to 12%, giving an adjusted prevalence ratio of 0.52 or a VT carriage reduction of 48%. Over three years, in an urban setting (Pakoto) in southern Nigeria, the proportion of children vaccinated increased from 15 to 94%. During the same period, the age-standardised population prevalence of VT carriage fell from 16 to 9%, giving an adjusted PR of 0.34 or a reduction in carriage of 66%. In both settings, we observed a decrease in VT carriage prevalence among children and older persons as vaccine coverage among children <5 years accumulated over time. For older persons (aged ≥5 years) this relationship was approximately linear representing a reduction in VT carriage prevalence of 1.4–1.5% for every 20% increase in vaccine coverage among children in the same setting.

Although carriage is only a proxy, we can use it to infer the impact of PCV10 on disease rates in these settings. A reduction in carriage prevalence will produce a proportionate reduction in the number of carriers each person contacts, reducing the incidence of carriage acquisition and the incidence of all pneumococcal diseases commensurately. A reduction in VT carriage prevalence of 66% at all ages in Pakoto is likely to translate into a reduction in the incidence of all VT pneumococcal disease of at least 66% at all ages. This estimate considers only the indirect effect of the programme, but it is, in itself, a very significant public health gain. Direct effects cannot be estimated from these surveys, but in an individually-randomised controlled trial of PCV9 in The Gambia, vaccine efficacy against VT IPD was 77%13. Therefore, even among the 34% of new pneumococcal infections that have not been potentially averted by indirect effects in Pakoto, the risk of developing disease will still be attenuated (by 77%) if the infected child has been vaccinated with PCV10, as most have.

This concept of additional gains from indirect vaccine effects is substantiated by the results from other settings. In Kilifi, Kenya, for example, a 74% decline in VT carriage prevalence among children aged <5 years was associated with a 92% decline in VT IPD in this age group14. In Sao Paulo, Brazil, a 91% decline in VT carriage prevalence among toddlers aged 12–23 months was associated with an 83–87% decline in VT IPD in children across the whole age range <5 years15,16.

The decline in VT carriage prevalence in Nigeria was accompanied by an increase in NVT carriage prevalence among children in Kumbotso (rural) and among older persons in both settings, with adjusted prevalence ratios of 1.26–1.34. In Kenya, the 74% decline in VT carriage prevalence was accompanied by a 1.71-fold increase in NVT carriage prevalence, though there was no significant rise in serotype replacement disease14. Non-vaccine serotypes with high frequency in the final surveys in children <5 years were 6A, 19A, 11A, 15B, and 16F. The first two are contained in the alternative PCV10 manufactured by Serum Institute of India, and 11A and 15B are contained in the PCV20 recently licensed for adult use17,18. This NVT distribution suggests that if serotype replacement disease becomes problematic, it may be controlled by wider valency vaccines. However, the relevance of serotype replacement carriage is dependent on the inherent invasiveness of the serotypes increasing in prevalence19–21 which can only be ascertained from linked studies of carriage and IPD14,20,22.

The study findings need to be interpreted in light of several practical constraints. The study began more than four months after PCV10 introduction, and at the baseline survey, an estimated 7–15% of children aged <5 years had already been vaccinated. Had the baseline survey pre-dated PCV10 introduction, the measured impact may have been larger. The evaluation is a ‘before-after’ study which is susceptible to confounding by secular trends in VT carriage prevalence. It is difficult to control for this possibility in retrospect. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that secular trends alone could account for so large an effect size on VT carriage. The study design did, however, control for seasonal variation in pneumococcal carriage23, as the surveys were done at the same time each year.

Vaccination coverage surveys were only introduced in 2018, and we inferred the coverage estimates for young children prior to 2018 from the coverage results among older children. Despite random selection and a study of adequate size, the coverage data contain internal inconsistencies; for example, in Pakoto, the rise in coverage in Year 3 (2019) was >40% and yet only ~20% of children aged <5 years were eligible to be vaccinated in that year. This may implicate poor recall of vaccination among caregivers of older children sampled in 2019. Vaccination coverage is notoriously difficult to ascertain24. Therefore, the ecological relationship we observe between coverage and VT carriage in older persons should be interpreted with some caution.

For practical reasons we selected two markedly different sites to represent the broad environmental and socio-demographic differences in Nigeria. However, we do not consider these sites to be wholly representative of all settings in Nigeria. Households in the rural site (Kumbotso) from northern Nigeria were larger, had more children and generally used solid cooking fuel. Households in the urban site (Pakoto) from southern Nigeria were smaller, had substantially fewer children and generally used gas and kerosene for cooking. At baseline, VT carriage prevalence was higher in the rural setting at all ages but, paradoxically, vaccine impact was greater in the urban setting, at least among children <5 years old; adjusted prevalence ratios were 0.52 in Kumbotso and 0.31 in Pakoto. This differential impact may be attributable to the steeper rise in PCV10 coverage among children aged <5 years in Pakoto. Alternatively, the lower density of children in urban households may imply a lower force of infection. A high force of infection has been proposed as an important cause of residual VT carriage in mature vaccine programmes in Africa25, and in Kumbotso, VT carriage prevalence reaches its nadir at 22% in years 2019/2020, compared to 9% in Pakoto in 2020.

Hence, the impact of the vaccine on carriage prevalence is likely to be affected by several additional factors; the baseline serotype distribution, age-specific carriage prevalence, demography, the contact patterns of the community, the probability of transmission at each contact and the duration of carriage and of vaccine-induced immunity26–28. The age structure of the vaccinated population is also influential; for example, a catch-up campaign for children aged <5 years in Kenya elicited a 64–66% reduction in VT carriage prevalence at all ages within six months of PCV10 introduction29. The full interaction of these effects can only be understood within a formal framework, such as a dynamic transmission model. Even here, the accuracy of predicting disease depends on a clear understanding of the risk of disease per episode of carriage for both VTs and NVTs30,31. The full spectrum of data required to parameterise such a model is not currently available for Nigeria.

Among children, we found that VT carriage declines exponentially with a large reduction in VT carriage prevalence observed at low levels of increasing PCV10 uptake. In an ecological analysis in Australia, 73% of VT-IPD cases were estimated to have been prevented by approximately 50% vaccine uptake of PCV7 [32], which lends credence to the hypothesis that indirect effects may begin at relatively low levels of uptake. It is also possible that our data are capturing the dynamic stage of a complex polynomial effect, and the exponential fit works only within the coverage range we explored. Although both direct and indirect effects are expected in children, changes are mostly driven by the latter, which supports the non-linear effect observed. Given that the impact on adult carriage is entirely attributable to indirect effects, we would expect the same function should be observed in older people. The arithmetic decline we observed in this population is, therefore, difficult to explain.

We restricted our study to detect a single serotype in each swab despite abundant evidence supporting multiple serotype colonisation in children32. The dynamics and clinical importance of multiple serotypes in nasopharyngeal carriage are not fully understood19,33. Nonetheless, sampling a single strain per child provides a valid estimate of the distribution of serotypes colonising the population of children in these areas.

The measurable impact on VT carriage reported here should reassure immunisation policymakers and service providers in Nigeria that, in settings with similar baseline epidemiology and comparable vaccine coverage across the country, PCV10 is bringing about population protection through its indirect effect. This protection is likely to have reduced the incidence of pneumococcal disease among all ages by 48–66%, depending on the setting. Among the majority of children aged <5 years who have now received a course of PCV10, this indirect effect will have been augmented by direct effects that are likely to be very strong. The decline in VT carriage prevalence as PCV10 coverage increases among children <5 years suggests that, in settings with sub-optimal coverage, efforts to improve coverage will yield significant reductions in carriage and transmission and, therefore, disease incidence.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted annual cross-sectional carriage surveys in Kumbotso, Kano State and Pakoto, Ogun State (Fig. 1). The sites were purposively selected to represent a rural and urban setting, respectively. We did four surveys (2017–2020) in the rural site and three (2018–2020) in the urban site. PCV10 was introduced in Kumbotso in July 2016 and in Pakoto in October 2016 with a schedule of three primary doses (3p + 0) at ages 6, 10 and 14 weeks and no booster. There was no formal catch-up campaign for children aged ≥12 months. From 2018 onwards, we conducted annual vaccine coverage surveys in both sites simultaneously with all carriage surveys. The target population for the carriage and vaccine coverage surveys was defined as residents living within 10 km of the Kumbotso and Pakoto Comprehensive Primary Health Care Centres, respectively. Baseline carriage surveys were conducted in December 2016 (rural) and February 2017 (urban), four to five months after PCV10 was introduced, and have already been published12. They are included in this analysis as the reference baseline.

Carriage surveys were seasonally restricted at each site; November/December for four years (2017–2020) in the rural site and February/March for three years (2018–2020) in the urban site (Fig. 1). Carriage surveys targeted all ages, and each annual sample was independent of all other samples. PCV10 coverage surveys targeted children aged <5 years who were age-eligible to have received PCV10 at the date of the baseline carriage survey. Each annual PCV10 coverage sample was selected independently of prior samples.

Having selected representative study areas, we used a two-stage sampling design. In the first stage, we selected households using simple random sampling. To obtain a sampling frame, we conducted a census of all households in the catchment area before each survey. We selected separate samples of households for the carriage and PCV10 coverage surveys. If the household was known to be occupied, but there was no one at home, we revisited it later. If the house was non-residential, unoccupied, or empty, we chose the next household on the list.

In the second stage of sampling for the carriage surveys, we randomly selected one participant per household drawn from a specific age-stratum. We recruited participants in ten age strata (<1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years), starting with the lowest and moving upwards, from household to household, until we had recruited one participant per age group and then we restarted the process. If there was no participant in a particular age group in the household or if the targeted individual declined to participate, we selected the next age group in sequence and then looked for the missed age group in the next household.

The baseline surveys sampled the same defined catchment areas at all ages using a convenience sample of volunteers, recruited at the two health centres, recruited by community outreach12. For the baseline carriage surveys (2016/2017)12, the sample size was set at 1000 participants to achieve a desired precision; given a VT carriage prevalence of 22–26% in this survey, we estimated a prevalence reduction of 50% could be detected with a power of 0.90 if the follow-up surveys were also 1000 in size. Therefore, we targeted to recruit 100 participants in each of the ten age groups.

In the second stage of sampling for the PCV10 coverage survey, we recruited all eligible children per selected household. A sample size of at least 639 children per site per survey was sufficient to estimate coverage of the second dose of PCV of 50% with a 5% precision (i.e., a coverage of 45–55%), assuming at least two eligible children per household, an intra-class coefficient (ICC) of 0.33 (as recommended by WHO34) and an 80% probability of response or participation35. Targeting a vaccination coverage of 50% allowed the estimation of the largest possible sample size required.

Procedure

Sociodemographic and clinical information was obtained from carriage survey participants using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Nasopharyngeal swabbing, transport, storage and culture were done according to WHO-recommended standards36. We collected one swab specimen per participant from the posterior wall of the nasopharynx using nylon-tipped flexible flocked swabs (FloQSwabs®). Swabs were transported to the laboratory within 8 h of collection in skimmed milk-tryptone-glucose-glycerine (STGG) on ice packs in a cold box and were stored at −80 °C to −55 °C before shipping on dry ice to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme (KWTRP), Kilifi, Kenya. In Kilifi, swabs were stored at −80 °C until they were thawed and cultured on blood agar with 5 μg/ml gentamicin.

We identified pneumococci by α-haemolysis and optochin sensitivity testing. For optochin-resistant isolates (zone of inhibition <14 mm diameter), we used bile solubility testing to confirm S. pneumoniae. For serotyping, we selected one colony per plate from the dominant colony morphology. We identified serotypes using latex agglutination confirmed by Quellung Reaction. For isolates with inconclusive serotyping, we confirmed species and serotype by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for autolysin (lytA) and capsular locus genes, respectively36.

For the PCV10 coverage survey, we obtained the PCV10 vaccination status of each child in the household, including doses and dates received from the vaccination cards or caregiver recall, through household interviews of caregivers.

Statistical analysis

Carriage surveys

We calculated the total (all ages) and age-stratified prevalence of overall carriage (all pneumococci), VT pneumococci, and NVT pneumococci for each survey year. Vaccine serotypes (VT) were those contained in the vaccine introduced locally (PCV10 – serotypes 1, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F). Any other serotype, including non-typeable isolates, was classified as NVT. We recalculated VT prevalence for four other commercially licensed PCVs (Supplementary Table 8). We standardised crude prevalence estimates to the population age structure of Kumbotso (for rural) and Ifo and Ado-Ota (for urban) Local Government Areas (LGAs). These were obtained from 2019 population models of the 2016 Nigerian census data37.

We assessed changes in carriage prevalence across the survey years using Chi-square test for trend. To derive prevalence ratios (PRs) comparing the last survey with the first, we modelled carriage prevalence using log-binomial regression or Poisson regression with robust standard errors when the models failed to converge. We adjusted PRs for exposure variables independently associated with carriage and survey year at p < 0.1 which included: living with children aged <5 years and a history of cough and runny nose in the preceding two weeks. We also adjusted for the stratified sampling method by (probability) weighting age-specific PRs by the local population age structure, as above, obtained from the Nigerian census data37. We calculated PRs for the total population (all ages), for children aged <5 years and for persons aged ≥5 years.

Vaccination coverage surveys

The purpose of the coverage survey was to infer population immunity, not to evaluate programme effectiveness. Therefore, we estimated PCV10 coverage in each survey year (2018–2020) as the proportion of children aged <5 years (regardless of age-eligibility) who received two doses of PCV10 irrespective of timing and age of receipt. In addition, because we did not conduct PCV10 coverage surveys in the early period (2016–2017), we used a birth cohort analysis to estimate the PCV10 coverage of children aged <5 years retrospectively from the data collected in 2018–2020.

Relationship between PCV10 coverage and VT carriage

Within the range of vaccine coverage observed, we analysed a simple ecological association between population-level PCV10 coverage in children aged <5 years and VT carriage, in both children aged <5 years and persons aged ≥5 years, using linear regression. We considered a non-linear relationship between PCV10 coverage and VT carriage using a log-linear model and compared the fit of linear to the log-linear model graphically. We also examined this non-linear relationship by comparing the models using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A lower value of AIC is a better fit model. To allow direct comparison of AIC values from the linear and log-transformed model, we adjusted the AIC of the log-linear model by adding the following quantity38:

| 1 |

We did all the analysis separately for each site with Stata® version 15.1(College Station, TX, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Wellcome Trust [214320 - JAGS] and NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Mucosal Pathogens [2268427 - IMOA]. A.L.A. is funded by the DELTAS Africa Initiative [DEL-15-003]. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)‘s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust [107769/Z/10/Z] and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust or the UK government. I.M.O.A. is funded by the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council and Department For International Development through the African Research Leader Fellowship (MR/S005293/1) and by the NIHR-MPRU at UCL (grant 2268427 LSHTM). J.A.G.S. is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (214320) and the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Immunisation. J.O. is funded by the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Mucosal Pathogens (16/136/46).

Author contributions

A.L.A., I.M.O.A., J.A.G.S. and J.O. contributed to study concept and design. A.L.A. led the fieldwork with input from D.A., A.K., M.M.B., I.A.A., C.A.N.O., V.I. and K.O.; A.K. led the laboratory work. B.A. oversaw the curation and management of data. A.L.A. performed all statistical analyses with input from J.O., I.M.O.A. and J.A.G.S.; A.L.A. wrote the first draft. A.L.A., B.K., I.M.O.A. and J.O. had direct access to and have verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Todd Swarthout and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files (Supplementary Data). Additional data requests can be made to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme Data Governance Committee (dgc@kemri-wellcome.org).

Code availability

Data were analysed using Stata® version 15.1 (College Station, Texas, USA).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for study was granted by the Research Ethics Committees of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (NHREC/21/08/2008/AKTH/EC/2165), Kano State Ministry of Health (MOH/OFF/797/T.I/596), Lagos University Teaching Hospital (ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/10300); the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Scientific and Ethical Review Unit (SERU 3350); and by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Observational/Interventions Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 11670).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from participants/guardians.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: J. Anthony G. Scott, Ifedayo M. O. Adetifa.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-38277-z.

References

- 1.Wahl B, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob. Health. 2018;6:e744–e757. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simell B, et al. The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2012;11:841–855. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.le Polain de Waroux O, et al. Characteristics of human encounters and social mixing patterns relevant to infectious diseases spread by close contact: a survey in Southwest Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18:172. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3073-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neal EFG, et al. Associations between ethnicity, social contact, and pneumococcal carriage three years post-PCV10 in Fiji. Vaccine. 2020;38:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SM, Deloria-Knoll M, Kassa HT, O’Brien KL. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on nasopharyngeal carriage and invasive disease among unvaccinated people: review of evidence on indirect effects. Vaccine. 2013;32:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dagan, R. Relationship between immune response to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and indirect protection after vaccine implementation. Expert Rev. Vaccines10.1080/14760584.2019.1627207 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shiri T, et al. Indirect effects of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2017;5:e51–e59. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladhani SN, Andrews N, Ramsay ME. Summary of evidence to reduce the two-dose infant priming schedule to a single dose of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the national immunisation programme in the UK. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21:e93–e102. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecrenier N, et al. Ten years of experience with the pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D-conjugate vaccine (Synflorix) in children. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2020;19:247–265. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1738226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feikin DR, et al. Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan J, et al. Using pneumococcal carriage studies to monitor vaccine impact in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2019;37:6299–6309. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adetifa IMO, et al. Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage in Nigeria: a two-site, population-based survey. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:3509. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutts FT, et al. Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammitt LL, et al. Effect of ten-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease and nasopharyngeal carriage in Kenya: a longitudinal surveillance study. Lancet. 2019;393:2146–2154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33005-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de C Brandileone M-C, et al. Effect of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae among children in São Paulo, Brazil. Vaccine. 2016;34:5604–5611. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandileone M-CC, Almeida SCG, Minamisava R, Andrade A-L. Distribution of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes before and 5 years after the introduction of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Brazil. Vaccine. 2018;36:2559–2566. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PNEUMOSIL® | WHO - Prequalification of Medical Products (IVDs, Medicines, Vaccines and Immunization Devices, Vector Control). https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/content/pneumosil%C2%AE-0.

- 18.Kobayashi M, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among U.S. adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2022;71:109–117. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet. 2011;378:1962–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62225-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yildirim I, et al. Surveillance of pneumococcal colonization and invasive pneumococcal disease reveals shift in prevalent carriage serotypes in Massachusetts’ children to relatively low invasiveness. Vaccine. 2017;35:4002–4009. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yildirim I, et al. Serotype specific invasive capacity and persistent reduction in invasive pneumococcal disease. Vaccine. 2010;29:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flasche S, et al. Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on serotype-specific carriage and invasive disease in England: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bojang A, et al. Seasonality of Pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in rural gambia determined within the context of a cluster randomized pneumococcal vaccine trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adetifa IMO, et al. Coverage and timeliness of vaccination and the validity of routine estimates: Insights from a vaccine registry in Kenya. Vaccine. 2018;36:7965–7974. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lourenço J, et al. Determinants of high residual post-PCV13 pneumococcal vaccine-type carriage in Blantyre, Malawi: a modelling study. BMC Med. 2019;17:219. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.le Polain de Waroux O, et al. Identifying human encounters that shape the transmission of Streptococcus pneumoniae and other acute respiratory infections. Epidemics. 2018;25:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swarthout TD, et al. High residual carriage of vaccine-serotype Streptococcus pneumoniae after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Malawi. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2222. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15786-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Althouse BM, et al. Identifying transmission routes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and sources of acquisitions in high transmission communities. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017;145:2750–2758. doi: 10.1017/S095026881700125X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammitt LL, et al. Population effect of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae in Kilifi, Kenya: findings from cross-sectional carriage studies. Lancet Glob. Health. 2014;2:e397–e405. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shea KM, Weycker D, Stevenson AE, Strutton DR, Pelton SI. Modeling the decline in pneumococcal acute otitis media following the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in the US. Vaccine. 2011;29:8042–8048. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojal J, et al. Sustained reduction in vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease despite waning effects of a catch-up campaign in Kilifi, Kenya: A mathematical model based on pre-vaccination data. Vaccine. 2017;35:4561–4568. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamng’ona AW, et al. High multiple carriage and emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccine serotype variants in Malawian children. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15:234. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0980-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hausdorff WP, Hanage WP. Interim results of an ecological experiment - Conjugate vaccination against the pneumococcus and serotype replacement. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016;12:358–374. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1118593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. World Health Organization Vaccination Coverage Cluster Surveys: Reference Manual.https://healthcluster.who.int/publications/m/item/who-vaccinationcoverage-cluster-surveys-reference-manual (2015).

- 35.Dhand, N. K. & Khatkar, M. S. Statulator: an online statistical calculator. Sample Size Calculator for Estimating a Mean. https://statulator.com/SampleSize/ss2P.html (2014).

- 36.Satzke C, et al. Standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: updated recommendations from the World Health Organization Pneumococcal Carriage Working Group. Vaccine. 2013;32:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.GRID3 Nigeria. National Population Estimates. https://grid3.gov.ng/datasets?§or=%5B%22population%22%5D (2019).

- 38.Akaike H. On the likelihood of a time series model. Statistician. 1978;27:217. doi: 10.2307/2988185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files (Supplementary Data). Additional data requests can be made to the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme Data Governance Committee (dgc@kemri-wellcome.org).

Data were analysed using Stata® version 15.1 (College Station, Texas, USA).