Abstract

Simultaneous prompting procedures are infrequently published in the behavior analytic literature yet represent a potential method for promoting nearly errorless learning. No research on simultaneous prompting has targeted early skill repertoires for young children with developmental disabilities. The current study compared simultaneous prompting and constant prompt delay procedures on the acquisition of simple listener responses for a 4-year-old male with Down syndrome. Simultaneous prompting produced responding at mastery levels in less than one third of the total sessions required in the prompt delay condition and substantially fewer errors.

Keywords: Constant prompt delay, Errorless learning, Simultaneous prompting

Prompt-fading procedures are ubiquitous in skill acquisition programs and may often be employed in an attempt to produce errorless (or nearly errorless) transfer of stimulus control (Etzel & LeBlanc, 1979). Several prompt-fading procedures have been described in the literature (see Cengher et al., 2018); however, reference to these procedures as errorless is often a misnomer. Simultaneous prompting (SP) has been extensively studied in the special education literature (Tekin-Iftar et al., 2019) and may be associated with fewer errors to mastery than more common prompt-fading procedures (e.g., prompt delay; Brown & Cariveau, 2022). In SP, performance is first assessed during daily probes followed by training of the target relations (Schuster et al., 1992). During training, SP procedures differ from a typical constant prompt delay procedure such that every trial is conducted at a 0-s prompt delay. In this way, only prompted correct responses are possible during training and transfer to the target discriminative conditions is assessed during daily probes.

Despite the consistent demonstration of efficacy in the educational literature, SP has not received similar attention in behavior analytic journals. In fact, SP has never appeared in the pages of Behavior Analysis in Practice. Additional research on SP is needed, particularly with young children and targeting early-to-develop skill repertoires. A recent descriptive analysis of SP by Tekin-Iftar et al. (2019) included only a single participant under the age of 5 years old and targeted relatively more advanced skill repertoires such as response chains, sight-word reading, and other academic content. The efficacy of SP when targeting early skills for young children is likely of interest to practitioners as this population may align with those enrolled in clinical programs. Moreover, the lack of explicit attempts to fade prompts during training in SP may be cause for concern among practitioners as this arrangement may be optimal for the development of prompt dependence, characterized by stimulus blocking (Vom Saal & Jenkins, 1970). The current study compared SP and prompt delay procedures on the acquisition of the first listener responses for a child with Down syndrome. Prompt delay procedures were commonly used in our practice, so this condition was intended to serve as a treatment as usual condition.

Method

Participant and Setting

Eric was a 4-year-old male with Down syndrome. The Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP; Sundberg, 2008) was conducted approximately 3 months before the current protocol was initiated. Eric’s performance on the VB-MAPP was consistent with an early level-one learner, receiving a total of one, two, and three points in the mand, listener, and tact domains, respectively. Eric showed relative strengths in the imitation and echoic domains on the VB-MAPP, receiving all five points in the first level. He was able to imitate nearly any single motor response; however, imitation with objects was not observed due to high rates of disruptive or noncompliant behavior when presented with tangible items. He received two points in the listener responding domain for attending to a speaker’s voice and looking when his name was said. He did not follow vocal directions. Notable barriers during the VB-MAPP included pervasive prompt dependence and a lack of conditional discrimination performance. The latter barrier was characterized by pervasive side biases to all stimulus arrays, including during preference assessments. Eric’s intervention goals before this study focused on mand training, increasing the duration of time spent at the table, reducing the latency to compliance (e.g., handing toys to the therapist), and expanding Eric’s echoic repertoire. The current study served as the initial training program to establish simple listener discriminations. Targets included touching a body part or emitting a brief action following an antecedent verbal stimulus. Eric was able to imitate all motor movements that were included as listener response targets (e.g., would touch his cheek when modeled, but not when vocally instructed to touch “cheek”).

All intervention sessions were conducted during tabletop instruction in an individual space in a large classroom. Eric sat diagonally from the instructor at the table and was the only child in the space during this protocol. All materials and tangible items were placed out of reach to prevent Eric from grabbing or swiping materials from the table during instruction.

Measurement, Interobserver Agreement, and Procedural Integrity

The primary dependent variables included unprompted correct responses, prompted correct responses, unprompted incorrect responses, and prompted incorrect responses. Unprompted and prompted correct responses were defined as the participant emitting the target response within 5 s of the antecedent verbal stimulus or the model prompt, respectively. Unprompted and prompted incorrect responses were defined as Eric emitting any response other than the target response or no response within 5 s of the antecedent verbal stimulus or model prompt, respectively. Percentage of unprompted correct responses was calculated by dividing the total number of unprompted correct responses by the total number of trials in a session and multiplying by 100. We also calculated the total number of errors (i.e., unprompted and prompted incorrect responses) and sessions to mastery during both training and daily probes. Sessions to mastery was calculated by summing the number of training and daily probe sessions required to produce responding at the mastery criterion in each condition.

Two independent data collectors, trained by the first author, were present for 91.9% of training and 95.8% of daily probe sessions. Trial-by-trial interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated by taking the total number of trials with an agreement divided by the total number of trials and multiplying by 100. Average agreement was 99.8% (range: 83.3%–100%) and 99.3% (range: 66.7%–100%) for training and daily probe sessions, respectively. IOA fell below 100% for a single session during daily probes.

Procedural integrity was scored on a trial-by-trial basis. Integrity was scored if the instructor implemented all trial components as indicated in the protocol. Data collectors recorded procedural integrity across 94.2% of training and 95.8% of daily probe sessions. Average procedural integrity was 99.6% (range: 83.3%–100%) during training and 100% during daily probe sessions.

Experimental Design and Procedures

An adapted alternating treatments design (Sindelar et al., 1985) with a no-treatment control condition was used to compare the effects of SP and prompt delay procedures on the acquisition of simple listener discriminations. Two targets were assigned to each condition. Targets were equated based on the number of syllables, initial sound of the antecedent verbal stimulus, and the similarity of the motor responses as recommended by Cariveau et al. (2021). Similarity of motor responses was equated by including one target in each condition that required raising at least one hand from the table or moving his head (e.g., nodding) and a second target that required his hands to be moved no more than a few inches from the tabletop (e.g., tapping the table). In alignment with the recommendation of Green (2001), the antecedent verbal stimulus was a single word, which was presented alone on each trial (e.g., “cheek” or “scratching”); that is, we excluded any additional instructions (e.g., “show me” or “can you”). Targets included scratching and wave (Set 1), tapping and cheek (Set 2), and nodding and arm (Set 3).

All conditions included two targets presented three times for a total of six trials per session. The mastery criterion was set at one daily probe with five out of six unprompted correct responses. This criterion was selected as there was no prompting or reinforcement of target responses during daily probes. As such, a single error may have been due to extinction (e.g., weakening motivating operations or incompatible behavior).

Daily Probes

Targets from each condition were presented in separate daily probe sessions. The order of conditions presented during daily probes was randomly determined each day. Each target was presented three times. No differential consequences followed correct or incorrect responses; instead, mastered demands (e.g., imitation targets) were presented after approximately every two trials. Correct responding to mastered demands produced praise, a 20-s break, and access to a preferred tangible item.

Comparison Phase

Two daily probes were conducted in each condition to serve as an initial baseline phase. Thereafter, the SP and constant prompt delay conditions were introduced for Sets 1 and 2, respectively. Each day began with a daily probe followed by an equal number of training sessions in each condition. Daily probes of the no-treatment control condition were conducted periodically throughout this phase.

Simultaneous Prompting

In this condition, the antecedent verbal stimulus was presented and immediately (i.e., 0-s prompt delay) followed by the presentation of the model prompt. Prompted correct responses resulted in praise and access to a tangible item for 20 s. Prompted incorrect responses were followed by the re-presentation of the antecedent verbal stimulus and the model prompt at a 0-s prompt delay until a prompted correct response was emitted.

Constant Prompt Delay

The first two training sessions in this condition were identical to the SP procedure (i.e., 0-s prompt delay). Thereafter, all training sessions were conducted at a 5-s prompt delay. Prompted and unprompted correct responses produced praise and 20 s of access to a preferred tangible item. Prompted incorrect responses resulted in the re-presentation of the trial at a 0-s prompt delay.

Error Correction

Eric began to show a response bias in the constant prompt delay condition (i.e., “tapping” was the only response emitted). As a result, we introduced a single-response repetition procedure (Kodak et al., 2016). In this procedure, an unprompted incorrect response resulted in the re-presentation of the antecedent verbal stimulus and an immediate prompt. Following a prompted correct response, the antecedent verbal stimulus was re-presented and the correct response was immediately prompted. Praise and 20 s of access to a tangible item were provided following the final prompted correct response. Additional 0-s prompt delay trials were added to the error-correction procedure each day unless responding increased during daily probes until the terminal number of re-presentations (i.e., five) was reached. Five re-presentations was selected as the terminal arrangement, consistent with a multiple-response repetition (MRR) procedure.

Blocked Trials

Blocked trials were introduced due to pervasive error patterns characterized by the exclusive emission of a single response topography in the constant prompt delay condition. In this modification, the target that was infrequently emitted by the participant without prompting (i.e., cheek) was presented during all six trials. The terminal MRR error-correction procedure and daily probe procedures were unchanged during this phase.

Best Treatment

After the mastery criterion was met in the SP condition, the same procedure was applied to the control set. This allowed for the extended evaluation of the constant prompt delay condition and comparison to another set of targets exposed to the SP procedure.

Results

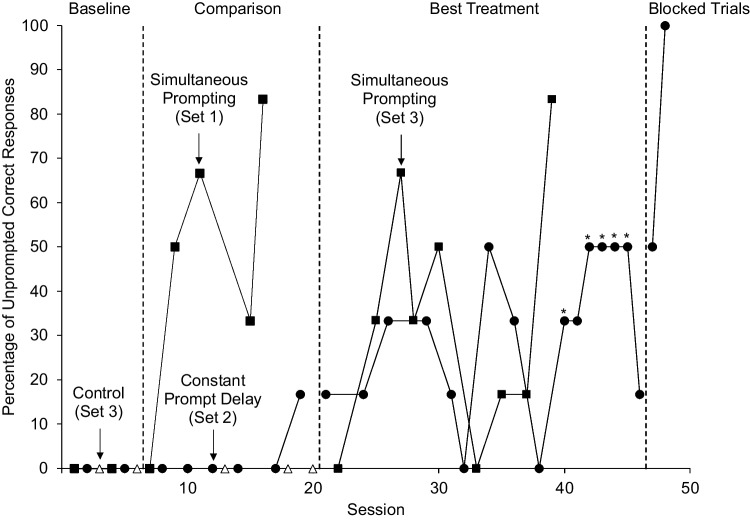

Eric’s performance during daily probes is shown in Fig. 1. During baseline, no correct responses were emitted across all conditions. Percentage of correct responses increased rapidly in the SP condition and met the mastery criterion after five daily probes; however, the constant prompt delay condition remained at near-zero levels throughout the comparison phase. Responding in the control condition remained at zero levels. The control set was then exposed to the SP procedure in the best-treatment phase and a rapid, albeit variable, increase in correct responding was observed. A similar increase was also observed in the prompt delay condition; however, performance in this phase never increased above 50% correct responses, suggesting that only a single target response was being emitted in this condition. After the mastery criterion was met for the second SP target set (i.e., Set 3), error correction was introduced in the prompt delay condition. Unprompted correct responding remained at or below 50%. During subsequent exposure to blocked trials, 100% correct responding was observed in the prompt delay condition.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Unprompted Correct Responses across Conditions during Daily Probes. Note. Control targets were exposed to the SP procedures in the Best Treatment phase (Daily Probe #9). *Indicates when the error-correction procedure was introduced or response requirement during error correction was increased

Figure 2 shows the total number of sessions to mastery. The SP conditions required 21 and 25 sessions to produce responding at mastery levels. In contrast, the prompt delay condition required 74 total sessions to reach the mastery criterion. Figure 3 shows the total number of errors to mastery across conditions. Eric emitted over six times as many errors in the prompt delay condition compared to either SP condition. Two and eight errors were emitted during training of Sets 1 and 3, respectively, compared to 218 errors during training in the prompt delay condition.

Fig. 2.

Total Number of Sessions to Mastery across Conditions

Fig. 3.

Total Number of Errors to Mastery across Conditions

Discussion

The current study serves as a preliminary demonstration of the efficacy and relative efficiency of a SP procedure on the acquisition of initial listener responses for a child with Down syndrome. Although limitations exist, the current findings extend this literature by training early skill repertoires that may align with those commonly targeted in early intervention settings. These findings may also hearten behavior analytic practitioners to consider similar procedures when they may otherwise be cautious due to concerns regarding the potential development of prompt dependence. Indeed, prompt dependence was observed in the current study, albeit only in the prompt delay condition. This finding is surprising as the SP procedure would seemingly arrange the optimal conditions for stimulus blocking to occur. Nevertheless, the current findings suggest that the SP procedure required considerably fewer sessions and errors to produce responding at mastery levels.

Additional research is needed to determine the conditions under which SP may be more effective or efficient than typical prompt-fading procedures. A recent review by Brown and Cariveau (2022) suggests that comparison studies have shown little difference in efficiency measures across SP and prompt delay conditions. In fact, the only consistent finding was that SP conditions typically resulted in fewer errors to mastery than prompt delay conditions. Researchers and clinicians might also consider optimal conditions for assessing acquisition. Research on SP has commonly employed daily probes; however, the daily probe procedures used in the current study may not exemplify those typically described in the literature. Brown and Cariveau reported that 9 of the 11 reviewed studies included reinforcement during daily probes, which was not arranged in the current study. In addition, the repeated presentation of the same targets during daily probes in this study may be unnecessary and lead to unwanted effects associated with extinction. Future research is needed to better understand the role of daily probes in SP procedures and whether direct reinforcement during these probes represents a requisite, or at least beneficial, feature of this procedure.

The current study suggests that SP may be an efficacious procedure when targeting early skill repertoires of young children with developmental disabilities. Additional replications are needed; however, practitioners should be encouraged by the current findings and those reported in the educational literature.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

All participants provided consent before participating in the current study.

Footnotes

The authors wish to thank Katelyn Hunt, Elizabeth Garcia, Jessica Sullivan, and Elizabeth Thuman for their assistance with various aspects of the study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Brown, A., & Cariveau, T. (2022). A systematic review of simultaneous prompting and prompt delay procedures. Journal of Behavioral Education. Advance online publication.

- Cariveau, T., Irwin, C., Moseley, T. K., & Hester, J. (2021). Methods to equate target sets in the adapted alternating treatments design: A review of special education journals. Remedial and Special Education. Advance online publication.

- Cengher M, Budd A, Farrell N, Fienup DM. A review of prompt-fading procedures: Implications for effective and efficient skill acquisition. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities. 2018;30:155–173. doi: 10.1007/s10882-017-9575-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etzel BC, LeBlanc JM. The simplest treatment alternative: The law of parsimony applied to choosing appropriate instructional control and errorless-learning procedures for the difficult-to-teach child. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 1979;9(4):361–382. doi: 10.1007/BF01531445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, G. (2001). Behavior analytic instruction for learners with autism: Advances in stimulus control technology. Focus On Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,16(2), 72–85. 10.1177/108835760101600203

- Kodak T, Campbell V, Bergmann S, LeBlanc B, Kurtz-Nelson E, Cariveau T, Haq S, Zemantic P, Mahon J. Examination of efficacious, efficient, and socially valid error correction procedures to teach sight words and prepositions to children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(3):532–547. doi: 10.1002/jaba.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster JW, Griffen AK, Wolery M. Comparison of simultaneous prompting and constant time delay procedures in teaching sight words to elementary students with moderate mental retardation. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1992;2:305–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00948820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar PT, Rosenberg MS, Wilson RJ. An adapted alternating treatments design for instructional research. Education and Treatment of Children. 1985;8(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program: The VB-MAPP. AVB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin-Iftar E, Olcay-Gul S, Collins BC. Descriptive analysis and meta analysis of studies investigating the effectiveness of simultaneous prompting procedure. Exceptional Children. 2019;85(3):309–328. doi: 10.1177/0014402918795702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vom Saal W, Jenkins HM. Blocking the development of stimulus control. Learning and Motivation. 1970;1:52–64. doi: 10.1016/0023-9690(70)90128-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]