Abstract

Almost one-third of the world population today harbors the tubercle bacillus asymptomatically. It is postulated that the morphology and staining pattern of the long-term persistors are different from those of actively growing culture. Interestingly, it has been found that the morphology and staining pattern of the starved in vitro population of mycobacteria is similar to the persistors obtained from the lung lesions. In order to delineate the biochemical characteristics of starved mycobacteria, Mycobacteria smegmatis was grown in 0.2% glucose as a sole carbon source along with an enriched culture in 2% glucose. Accumulation of the stringent factor guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) with a concomitant change in morphology was observed for M. smegmatis under carbon-deprived conditions. In addition, M. smegmatis assumed a coccoid morphology when ppGpp was ectopically produced by overexpressing Escherichia coli relA, even in an enriched medium. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis relA and spoT homologue, when induced in M. smegmatis, also resulted in the overproduction of ppGpp with a change in the bacterium's growth characteristics.

Mycobacteria have emerged as a major threat to humankind, for as many as one-third of the world's population (1.7 billion) harbors the tubercle bacillus asymptomatically (18). The latent bacilli can persist in a somewhat ill-defined physiological state in pulmonary and extrapulmonary lesions for years after infection (30). These bacilli are opportunistic and can reactivate themselves when the host is immunocompromised. To add to the misery, persistors require prolonged therapy, and Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination has little effect in blocking reactivation of the bacteria. Hence, for improved control of tuberculosis, it is imperative to develop effective drugs to cease the propagation and persistence of these latent bacilli. This will be greatly facilitated by a better understanding of the physiological state of these latent bacteria. Although several in vitro models suggest low extracellular concentrations of oxygen to be an important cause for mycobacterial dormancy (8, 10, 42), the effect of this state on cellular metabolism is not clear.

It has been shown that the morphology and staining pattern of an in vitro culture of mycobacteria differ from those of persistors which are obtained from the lung lesion and are chromophobic to the conventional acid-fast staining (25, 26). The former is an acid-fast and long rod-shaped bacillus, as opposed to the latter, which is non-acid fast and granular. However, these persistors can be stained after oxidizing the cell surface with periodic acid. In yet another important observation, it has been shown that the morphology and staining pattern of such persistors can be obtained in vitro by starving the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium kansasii, or Mycobacterium pheli cultures on agar plates without any nutrients (26). This key observation suggests that the natural persistors may be physiologically similar to bacteria in nutritionally starved cultures. Thus, studying the physiology and morphology of such starved cultures could provide some important clues towards understanding the mechanism of latency. This hypothesis prompted us to take up the study of starving mycobacteria.

Bacteria adapt to nutritional stress for their survival, predominantly through a mechanism termed the stringent response. The hallmark of the stringent response is the accumulation of guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), also called the stringent factor, and downregulation of stable RNA (rRNA and tRNA) synthesis (3). It appears that RNA polymerase is the ultimate target of ppGpp (6), although the exact mode of selective downregulation of the gene expression is not clear.

Many bacteria can assume a well-defined physiological state under starvation conditions, which facilitates their survival (23, 27, 38). The role of ppGpp in the developmental process of these physiological states has been a subject of interest for many researchers over the years. It has been extensively studied in Myxococcus xanthus, in which accumulation of ppGpp has been observed to be an important requirement for the formation of the fruiting body (16). In Streptomyces coelicolor, ppGpp has been implicated in the synthesis of antibiotics in the stationary phase of the bacteria (5). Though ppGpp has been detected in various other prokaryotes during starvation, e.g., Bacillus subtilis (28), Bacillus stearothermophilus (12), Staphylococcus spp. (4), Streptococcus equisimilis (24), and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (20, 35), its function in these organisms is yet to be assigned.

Although Mycobacterium smegmatis is nonpathogenic, it shares many biosynthetic pathways with M. tuberculosis and may serve as a good model system. In addition, its higher growth rate makes it a suitable candidate for starvation studies. In this study we have shown that ppGpp accumulation is accompanied by morphological change in M. smegmatis under carbon starvation conditions. Furthermore, we have shown that M. smegmatis assumes the coccoid morphology (similar to the persistors) when ppGpp is ectopically produced by overexpression of Escherichia coli relA in an enriched nutritional medium. We have also characterized the in vivo function of the M. tuberculosis relA/spoT homologue in M. smegmatis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth.

M. smegmatis, strain mc2155, was grown in MB7H9 (Difco) with 2% glucose and 0.05% Tween 80 for enriched culture. In the carbon-starved medium the glucose concentration was reduced to 0.2% without any Tween 80 in the medium. For comparative studies of pMatt1 and pMatt2, samples of the culture stock from −70°C were subcultured once before being inoculated in the experimental culture. For acetamide-induced expression, bacteria were grown in MB7H9 having 2% succinate with 0.05% Tween 80 and the culture was induced with 2% acetamide. For the plate culture the same composition was used with 1.5% agar. The growth kinetics of the culture was studied by measuring the culture's optical density (OD) at 600 nm. E. coli strain CF3120 is relA-overexpressing strain which bears relA under the control of the Ptac-lacIq promoter-operator system on a multicopy plasmid, pALS10. The gene is induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to Luria-Bertani medium.

Plasmids.

For overexpression of E. coli relA, pMV261 (40) bearing Phsp60 was converted into an integrative vector, pMatt1, by removing its NotI fragment containing oriM and ligating the backbone with the SalI fragment of pDK20 (9), which consists of the integrating signal of mycobacteriophage L5. Then the EcoRI-HindIII relA fragment from pALS10 (a gift from Mike Cashel) was subcloned into the EcoRI-HindIII site of pMatt1 to generate pMatt2, thus generating a transcriptional fusion of relA with Phsp60.

The M. tuberculosis relA/spoT homologue (Rv2583c) along with its ribosome binding site (RBS) was obtained from the KpnI-EcoRV fragment of the cosmid pY227 (7) and subcloned into the KpnI-XbaI (end-filled with Klenow fragment) ends of pAGAN90 (29). The recombinant plasmid, pMtrel2, has an acetamide-inducible 2.2-kb transcriptional apparatus fused to the RBS and open reading frame (ORF) of the gene.

ppGpp detection.

A 25-ml M. smegmatis culture was grown to an OD of 0.2, and then [32P]H3PO4 (BRIT, Hyderabad, India) was added to it to a final concentration of 100 μCi/ml. The labeled cells were harvested at an OD of 0.8, washed once with 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), resuspended in 50 μl of buffer, treated with 1 mg of lysozyme per ml on ice for 20 min, and lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and ppGpp was extracted with an equal volume of 2 M formic acid. After centrifugation at a high speed at a cold temperature for 10 min, 5 μl of the supernatant was loaded on a polyethyleneimine (PEI)-coated thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Merck). The plate was developed in 1.5 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.4) in one dimension. It was air dried and exposed to X-ray film (Konika) for 18 to 24 h at −70°C for autoradiography. For alkaline hydrolysis of ppGpp, the formic acid extract was immediately neutralized with NH4OH, treated with 0.3 M KOH, and then treated with 0.1 M BaCl2 at 37°C for 1 h.

In order to detect ppGpp in a relA or relA/spoT-overexpressing system, the 32P-labeled culture was induced at an OD of 0.4 and harvested at an OD of 0.8.

Microscopy.

The heat-fixed smear of the culture was stained with carbol-fucshin (Loba Chemicals, Mumbai, India), washed with 20% H2SO4, counterstained with methylene blue (Loba Chemicals), and observed under a light microscope (Olympus) (magnification, ×1,000) in either phase-contrast or bright-field mode.

Complementation analysis.

For functional complementation of M. tuberculosis relA/spoT in E. coli, the relA strain of E. coli (MC4100) was transformed with pMtrel2 and selected on Luria-Bertani agar containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml). The transformants were streaked on glucose M9 minimal agar plus 100 μg of serine, methionine, and glycine (SMG) per ml or glucose M9 minimal agar. The reversion of the relA strain to relA+ strain was observed by the loss of sensitivity to SMG.

Miscellaneous.

All the cloning experiments and immunodetection were carried out as described earlier (32). The immunoblot was analyzed by a densitometer (Bio-Rad). DNA was electroporated into M. smegmatis using a Bio-Rad electroporator at 1.5 kV/mm (17), and transformants were selected on MB7H9 agar containing 20 μg of kanamycin per ml.

RESULTS

Growth kinetics, ppGpp accumulation, and morphology.

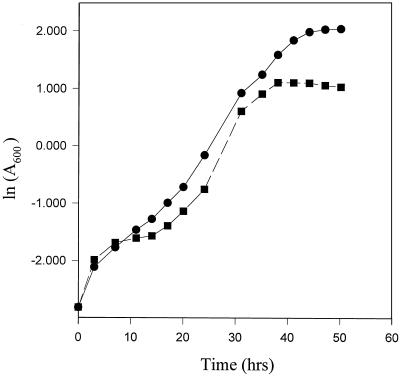

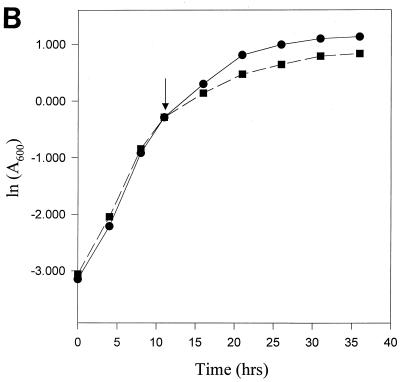

M. smegmatis, strain mc2155, was grown in an enriched (2% glucose) and carbon-deficient (0.2% glucose) medium. The MB7H9 medium contains l-glutamic acid, which can be used as a carbon source for M. smegmatis, albeit inefficiently. However, the total carbon coming from 0.2% glucose and glutamic acid was much less in comparison to that from an enriched medium. The bacteria followed altered growth kinetics when grown in carbon-deficient medium. The carbon-deficient culture showed earlier entry into stationary phase at a lower cell density, with an average generation time of 2.8 h, whereas the normal culture, which doubled every 2.0 h, had a very high cell density in the stationary phase (Fig. 1). This observation is consistent with an earlier report on growth kinetics and stationary phase entry of M. smegmatis in carbon-limited medium (37). Based in this observation we termed the 0.2% glucose medium as carbon-starved medium for the bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Comparative growth kinetics of normal (●) and carbon-starved (■) cultures of M. smegmatis. The generation time of a normal culture grown in enriched medium (2% glucose) is 2.0 h, whereas that of a carbon-starved culture (0.2% glucose) is 2.8 h. An early entry into the stationary phase at low cell density of the latter is evident from the profile.

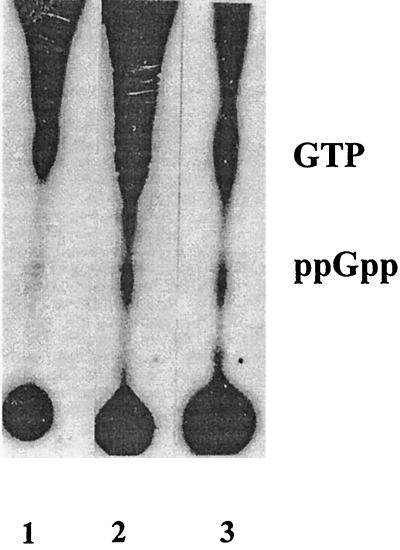

Following the observation of the growth kinetics the question of whether mycobacteria accumulate ppGpp upon carbon starvation was raised. This question stems from the fact that ppGpp is almost a universal growth regulator in starved prokaryotes. In order to detect the ppGpp accumulation in M. smegmatis, 32P-labeled mid-log-phase cells of equal OD (0.8) in enriched and carbon-starved medium were subjected to the extraction procedure (see Materials and Methods). It can be seen from Fig. 2 and comparing lanes 1 and 2 that the formic acid extracts from the cells grown in carbon-deficient medium clearly showed accumulation of ppGpp, in contrast to the cellular extract from enriched medium. The authenticity of ppGpp was demonstrated by its comigration with ppGpp from the 32P-labeled formic acid extract of E. coli overexpressing relA (CF3120) (Fig. 2, lane 3). The alkaline hydrolysis of ppGpp, as reported earlier (2, 31), was carried out to further confirm the existence of the nucleotide.

FIG. 2.

Accumulation of ppGpp in carbon-starved M. smegmatis. Five microliters of 32P-labeled formic acid extract of normal culture grown in MB7H9–2% glucose–0.05% Tween 80 (lane 1) and carbon-starved culture grown in MB7H9–0.2% glucose (lane 2) were loaded on a PEI-coated TLC plate and resolved as mentioned in the text. To confirm the authenticity of the spot, a 32P-labeled formic acid extract of E. coli strain (CF3120, overexpressing the ppGpp synthase gene, relA, was loaded as a control (lane 3).

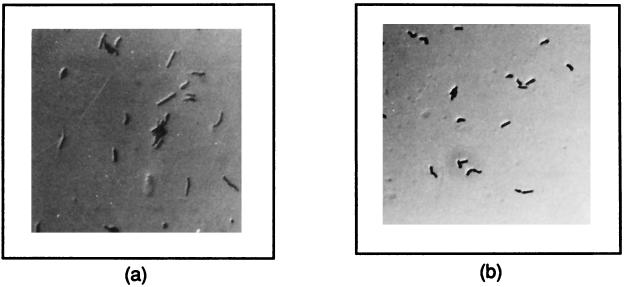

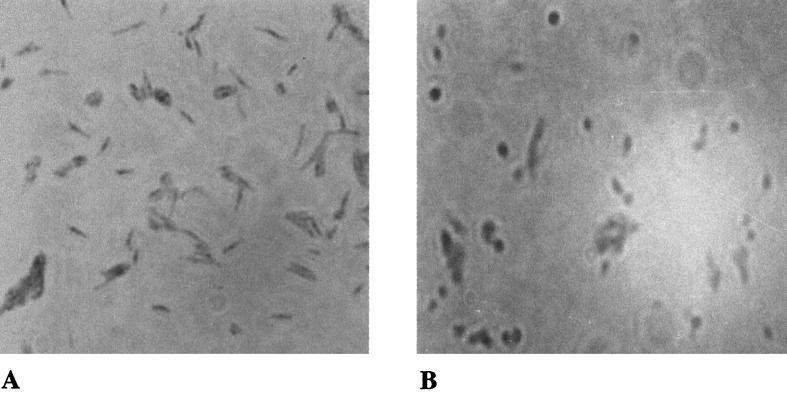

In order to compare the morphologies of the normal and carbon-starved bacteria, the acid-fast stains of the two cultures at an OD of 0.8 were prepared and observed under phase-contrast microscope at a magnification of ×1,000. It was observed that the cells under carbon starvation showed reduction in length (almost like a coccoid) in comparison to the normal bacilli (Fig. 3). In order to rule out any effect of Tween 80 on the growth kinetics and morphological changes, the carbon-deficient medium was supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, and the observations were repeated (not shown). Moreover, the morphology of the bacteria was also observed from the plate culture that was devoid of Tween 80.

FIG. 3.

Morphological difference between normal (a) and carbon-starved (b) cultures of M. smegmatis. The two cultures were grown in the same way as mentioned in the legend for Fig. 2. The heat-fixed smear of the cells was stained with carbol-fuchsin and observed under a light microscope in the phase-contrast mode at ×1,000 magnification.

Such a morphological change has been reported previously in late-stationary-phase cultures of M. smegmatis (37), in which the length of the stationary-phase bacterium is reduced to half. There is indirect evidence to suggest that ppGpp regulates the cell division through FtsZ (a protein required for septum formation) in E. coli (41). Overexpression of relA in E. coli leads to enhanced septum formation and reduced cell size (33). The reduced cell size with concomitant accumulation of ppGpp in M. smegmatis suggests a possible role of ppGpp in the morphological changes in mycobacteria.

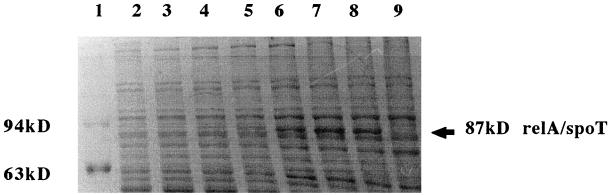

Overexpression of E. coli relA.

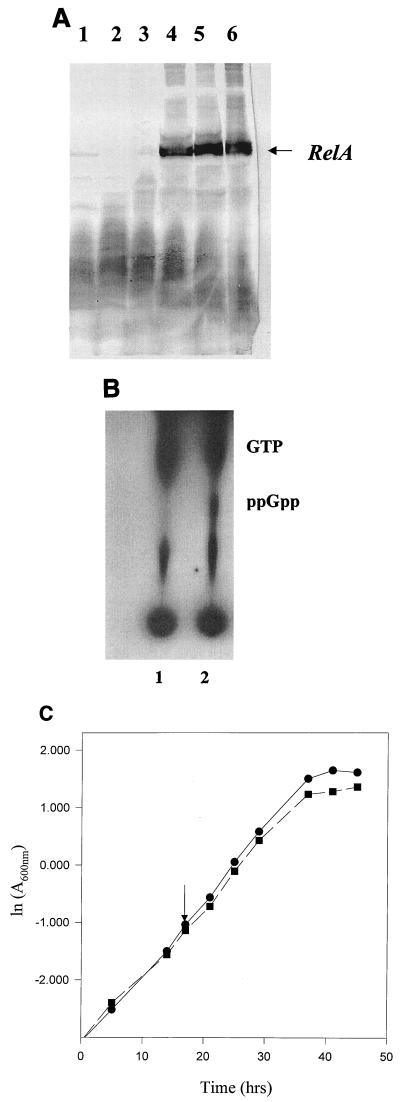

In order to understand the correlation between morphological changes and accumulation of ppGpp, we tried to overexpress relA (ppGpp synthase) from E. coli in M. smegmatis. An attempt to overexpress relA from a multicopy plasmid (pMV261) containing the BCG Phsp60 promoter was not successful. This could be explained by the fact that the gene driven by Phsp60 from a multicopy vector would produce a high level of ppGpp, which would perhaps be toxic for the organism. Since cellular response to ppGpp is dose dependent, a single-copy vector was chosen. An integrative vector (pMatt1) was constructed by replacing oriM from pMV261 with att-int (the attachment site and integrase protein, from mycobacteriophage L5). A transcriptional fusion of E. coli relA and Phsp60 was constructed by subcloning the gene along with its translational signal downstream of Phsp60 in pMatt1 to generate pMatt2. Both pMatt1 and pMatt2 were electroporated into M. smegmatis. The expression of relA at the translational level was confirmed by immunoblotting against anti-E. coli relA antibody (Fig. 4A), and the bands were quantitated using a densitometer. Although the basal level of protein at 30° was high, the expression was temperature dependent. There was an almost 2.5-fold increase in expression upon shifting the culture from 30 to 44°C. However, there was only a 30% increase in protein level when the culture was shifted from 30 to 37°C. Hence, for all the subsequent experiments on pMatt1 and pMatt2 strains the cultures were maintained at 30°C and induced by shifting to 44°C. The intracellular levels of ppGpp in the strains containing pMatt1 and pMatt2 were compared in mid-log phase. As can be seen from Fig. 4B, the strain containing pMatt2 showed accumulation of ppGpp in contrast to the strain containing pMatt1, in which there was no such accumulation. It confirmed the expression and function of E. coli relA in M. smegmatis.

FIG. 4.

(A) Expression of E. coli relA in M. smegmatis. Equal amounts of protein from whole-cell lysate of pMatt1 (lanes 1 to 3) and pMatt2 (lanes 4 to 6) grown at 30°C (lanes 1 and 4), 37°C (lanes 2 and 5), and 44°C (lanes 3 and 6) were subjected to SDS–8% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-E. coli relA antibody. (B) Accumulation of ppGpp upon overexpression of E. coli relA in M. smegmatis. The strain overexpressing relA, pMatt2, was induced along with the control strain, pMatt1, by shifting the culture (at an OD of 0.4) from 30 to 44°C. Five-microliter aliquots of 32P-labeled formic acid extract of pMatt1 (lane 1) and pMatt2 (lane 2) were loaded on PEI-coated TLC plates, and spots were resolved as mentioned in the legend for Fig. 2. Comigration of purified cold ppGpp (not in picture) confirmed the labeled ppGpp spot. (C) Effect of high intracellular levels of ppGpp on growth kinetics of M. smegmatis. The generation time of the strain overexpressing E. coli relA, pMatt2 (■), was 2.6 h, compared to 2.1 h for the control, pMatt1 (●). Both the cultures were grown in MB7H9–2% glucose–0.05% Tween 80 at 30°C till mid-log phase and were induced by shifting to 44°C. The arrow indicates the time of induction.

Since ppGpp is known to be a growth regulator in various prokaryotes, the effect of ppGpp accumulation on the growth kinetics of M. smegmatis was studied. As expected, we observed a slow growth rate for the strain harboring pMatt2 in comparison to the one with pMatt1 (Fig. 4C). Although the time of entry into stationary phase for the two cultures was the same, the OD of the pMatt2 culture was lower than that of the pMatt1 culture. This observation has been reported previously in other organisms (34, 36). The observed growth kinetics, as expected, suggest that ppGpp is likely to have a mechanism of operation in mycobacteria similar to that in other prokaryotes. However, the overall change in growth kinetics in this case is quantitatively different (the generation time of pMatt1 and pMatt2 are 2.1 and 2.6 h, respectively) from the one noticed under carbon starvation (Fig. 1). This can be explained by the fact that global metabolism of the cell would be affected more by nutritional depletion than by accumulation of one regulatory factor. Furthermore, poor regulation of expression and subsequent outgrowth of suppressor variants would further reduce the effect of the regulatory molecule on the growth rate of the bacterial population.

In order to observe the morphological change as a consequence of ppGpp accumulation, the two strains (pMatt1 and pMatt2) were grown at 30°C in enriched medium to an OD of 0.4 and then were shifted to 44°C. Then heat-fixed smears were stained with carbol-fuchsin. The slides were observed under a bright-field microscope (×1,000 magnification). The strain carrying pMatt2 appeared as short cocci, in contrast to the pMatt1 strain, which appeared as long, thin, rod-shaped bacilli (Fig. 5). These microscopic observations again indicate that ppGpp plays a crucial role in the morphological changes in M. smegmatis.

FIG. 5.

Morphological difference as a consequence of ppGpp accumulation in M. smegmatis. The strain harboring pMatt2 (overexpressing E. coli relA) has a spherical morphology (B) compared to the elongated rod shape morphology of the strain carrying pMatt1 (empty vector) (A). The two cultures were grown at 30°C till an OD of 0.4 was reached and then was induced by incubating at 44°C. After 4 h of induction the carbol-fuchsin-stained bacteria were observed with a light microscope in the bright-field mode at ×1,000 magnification.

Functional Characterization of M. tuberculosis relA/spoT in vivo (i) Overexpression of M. tuberculosis relA/spoT homologue in M. smegmatis.

Upon analyzing the genome sequences, a putative ppGpp synthase has been identified in M. tuberculosis (7) and Mycobacterium leprae (11). Interestingly, the single gene identified has almost 50% homology to both relA and spoT (encoding ppGpp hydrolase) of E. coli. Hence, it is possible that mycobacteria have only one gene for both synthetic as well as hydrolytic activity of ppGpp. Furthermore, the relA/spoT homologues from the two species of mycobacteria are 97% identical in their amino acid sequence, which suggests that the gene is functionally conserved across the species in mycobacteria. Since the relA/spoT homologue of M. smegmatis is not yet identified, we decided to characterize the function of M. tuberculosis relA/spoT using M. smegmatis as a surrogate host. In order to achieve this, another widely used mycobacterial promoter, Pamidase, was chosen. This promoter cassette is a 2.2-kb sequence with three ORFs and several consensus promoter sequences and is induced by addition of actamide to a medium having a poor carbon source (succinate) (29). However, the exact mechanism of induction is unknown. The EcoRV-KpnI fragment (ORF Rv2583c, cosmid MTCY227) consisting of the relA/spoT ORF with its RBS was subcloned downstream of the 2.2-kb acetamide-inducible region of pAGAN90 (29), resulting in a transcriptional fusion of relA/spoT with an acetamide-inducible promoter.

The recombinant plasmid (pMtrel2) thus obtained was electroporated into M. smegmatis, and transformants were selected on MB7H9 agar containing kanamycin. The induction of the gene was seen when the strain bearing pMtrel2 was grown in MB7H9 broth containing 2% succinate till mid-log phase, with a subsequent addition of 2% acetamide. The Coomassie blue-stained gel used for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) showed induced expression of one 89-kDa protein after 2 h of addition of the inducer (acetamide) (Fig. 6). The cellular content of the protein increased even after 20 h of induction, which indicates a long half-life of the protein.

FIG. 6.

Coomassie-blue stained polyacrylamide gel showing acetamide-induced expression of M. tuberculosis relA/spoT in M. smegmatis. The mid-log phase of the culture harboring pMtrel2 was induced with 2% acetamide. A 1-ml aliquot was taken out at the indicated time interval after induction. Equal amounts of the total cellular proteins were resolved by SDS–8% PAGE. Lane 1, marker; lanes 2 to 8, 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 20 h, respectively, after induction; lane 9, total cellular protein of a saturated culture of a strain harboring empty vector, pAGAN90.

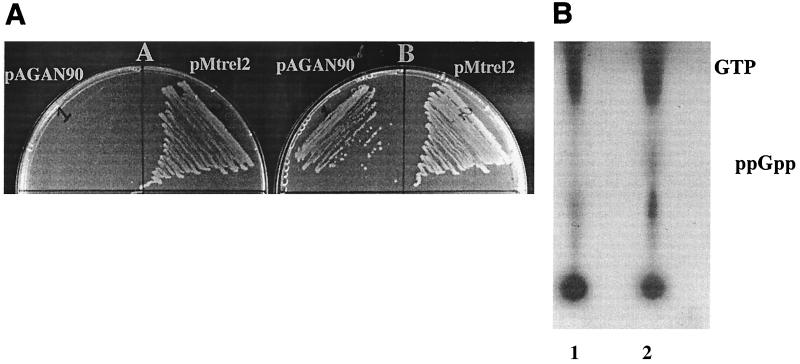

(ii) Complementation of E. coli relA by M. tuberculosis relA/spoT.

Since the 2.2-kb inducible region of pMtrel2 has appropriately placed E. coli consensus −35 and −10 sequences (21), it was assumed to be transcriptionally active in E. coli. Hence, the upstream regulatory region of pMtrel2 was thought to be sufficient for complementation in E. coli. Thus, the plasmid pMtrel2 containing M. tuberculosis relA/spoT was transformed into a relA strain of E. coli (MC4100). The transformant was checked for the relA+ phenotype on a minimal medium plate with SMG. Since relA strains of E. coli are defective in derepression of the amino acid biosynthetic genes in amino acid-limiting medium, the cells are rendered sensitive to the presence of amino acids (through end product inhibition) in minimal medium (3). As can be seen in Fig. 7A, MC4100, which is sensitive to SMG, could form colonies on SMG plates when transformed with pMtrel2. This indicates that the gene coding for the 89-kDa protein can complement the RelA phenotype in E. coli and thus is a relA homologue.

FIG. 7.

(A) complementation of relA E. coli (MC4100) by the M. tuberculosis relA/spoT homologue. The reversion of relA to relA+ was assayed by loss of SMG sensitivity. The transformant harboring empty vector (pAGAN90) was streaked on the left sector, whereas the one harboring vector with the gene (pMtrel2) was streaked on the right sector. Panel (A) Minimal medium plus SMG; panel (B) minimal medium. (B) ppGpp synthetic activity of the M. tuberculosis relA/spoT homologue in M. smegmatis. The 32P-labeled cells were grown in MB7H9–2% succinate till mid-log phase and then induced for 4 h with 2% acetamide. Five-microliter aliquots of the formic acid extract of strains pAGAN90 (lane 1) and pMtrel2 (lane 2) were loaded on PEI-coated TLC plates and the spots were developed as described in the text.

(iii) ppGpp accumulation and its effect on cell growth upon induction of relA/spoT homologue.

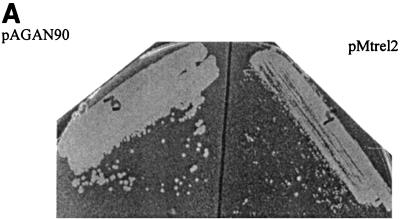

In the next experiment relA/spoT in pMtrel2 was induced in M. smegmatis as described above. The elevated intracellular level of ppGpp as a consequence of induction was observed (Fig. 7B). There was no detectable level of ppGpp either in the uninduced state of pMtrel2 or the empty vector, pAGAN90 (data not shown). The result indicates the ppGpp synthetic activity of the relA/spoT homologue. Although the synthesis of pppGpp by the same gene has been reported in an in vitro experiment (1), such a product could not be detected unambiguously in the formic acid extract because of comigration of some unknown spot. The growth kinetics of the strains having pMtrel2 and pAGAN90 were compared in culture as well as on plates (Fig. 8). The generation time of pMtrel2 was 4.1 h, compared to 2.5 h for pAGAN90, after induction. An enhanced reduction in growth rate compared to that in the pMatt1-pMatt2 system can be attributed to the controlled regulation of Pamidase. The slow growth of the strain having pMtrel2 upon induction is consistent with our previous observation that ppGpp downregulates the growth rate in M. smegmatis. The morphology of the two strains could not be compared because of severe clumping of the cells in the medium containing succinate and acetamide.

FIG. 8.

Effect of ectopic expression of the M. tuberculosis relA/spoT on growth of M. smegmatis. (A) Reduction in colony size of the strain overexpressing relA/spoT (pMtrel2) as compared to the control (pAGAN90) when grown on MB7H9–2% succinate–2% acetamide. (B) Comparison of growth kinetics in liquid culture. The arrow indicates the time at which the inducer (2% acetamide) was added.

DISCUSSION

The experimental observation reported here indicates that morphological changes, from an elongated rod to a spherical coccus, in carbon-starved M. smegmatis may be due to elevated intracellular levels of ppGpp. It has been observed that other bacteria, like S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (13), Vibrio vulnificus (22), Arthrobacteria crystallopoietes (39), and Pseudomonas putida (14), undergo similar changes in low-nutrient medium, although the concomitant change in the ppGpp pool has not been established. It appears that such morphological change substitutes for a programmed differentiation (as seen in sporulating bacteria) in nondifferentiating bacteria. Although the molecular mechanism of bacterial size reduction is far from being clear, it is held that rapid cell division without an increase in cell mass results in the short spherical shape (19). Probably, the increase in cell number improves the strain survival during starvation. The fact that M. smegmatis undergoes a similar morphological change during the period of starvation shows a fundamentally common mechanism of bacterial survival under extreme growth conditions.

The involvement of ppGpp in cellular differentiation in M. smegmatis may provide an important clue towards understanding the survival of the organism. It can be perceived that M. smegmatis adopts a stringent physiology during starvation which results in a concomitant increase in the ppGpp pool. However, detailed studies on kinetics of macromolecular synthesis and degradation in a starved culture are required before a clear picture can be conceived.

The complementation study of the relA/spoT of M. tuberculosis in E. coli suggests a functionally conserved pathway in prokaryotes. However, the reason for the presence of a bifunctional (ppGpp synthase and hydrolase) gene in mycobacteria and related organisms, streptomyces, remains unanswered. Nevertheless, a possible role of stringent pathways in the developmental processes of even evolutionarily divergent species of bacteria cannot be ruled out.

The studies on starvation in mycobacteria bear relevance to the physiological state of latent tubercle bacilli. Because of similarities in morphology between starved cultures and natural persistors, the two can be argued to have the same metabolic activity. The change in bacterial shape as a consequence of ppGpp accumulation suggests an important role of the stringent factor in transformation of active bacilli into latent bacilli.

The role of ppGpp in pathogenesis appears to be interesting, based on a recent report showing that the nucleotide is a key switch in transformation of an avirulent to virulent form of Legionella pneumophila (15). Upon correlating the mechanisms of infection and natures of persistence between L. pneumophila and M. tuberculosis, we suggest an important role for ppGpp in the latency of the mycobacterium, and thus, studies on the stringent pathways would answer some important questions pertaining to the physiological transformation in this pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our deep sense of gratitude to Bill Bishai (The Johns Hopkins University) and Mike Cashel (NIH) for their generous help at various stages of this work. We are also thankful to Anil K. Tyagi for the kind gift of pDK20, Tanya Parish for the gift of pAGAN90, and S. T. Cole for the cosmid MTCY227. We thank Faaizah Khan and Saket Verma for performing control experiments. We also acknowledge anonymous reviewers for their help in improving the manuscript.

A.K.O. is the recipient of a CSIR fellowship. This work was funded by the CSIR and the Department of Biotechnology of the government of India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avarbock D, Salem J, Li L, Wang Z, Rubin H. Cloning and characterisation of a bifunctional Rel A/spoT homologue from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Gene. 1999;233:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cashel M, Kalbacher B. The control of ribonucleic acid synthesis in E. coli. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:2309–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cashel M, Gentry D R, Hernandez V J, Vinella D. The stringent response. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbargar H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1458–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassels R, Oliva B, Knowles D. Occurrence of regulatory nucleotides ppGpp and pppGpp following induction of the stringent response in staphylococci. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5161–5165. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.5161-5165.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraburty R, Bibb M. The ppGpp synthetase gene (relA) of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) plays a conditional role in antibiotic production and morphological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5854–5861. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5854-5861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterji D, Fujita N, Ishihama A. The mediator for stringent control, ppGpp, binds to the β-subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Genes Cells. 1998;3:279–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, Mclean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajendram M A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barell B G. Deciphering the biology of M. tuberculosis from complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham A F, Spreadbury C L. Mycobacterial stationary phase induced by low oxygen tension: cell wall thickening and localization of 16-kilodalton α-crystalline homolog. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:801–808. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.801-808.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta S K, Jain S, Kaushal D, Tyagi A K. Expression systems for study of Mycobacterial gene regulation and development for recombinant BCG vaccines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:797–804. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dick T, Lee B H, Murugasu-Oei B. Oxygen depletion induced dormancy in Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eigelmeier K, Honore N, Woods S A, Caudron B, Cole S T. Use of an ordered cosmid library to deduce the genomic organization of Mycobacterium leprae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehr S, Richter D. Stringent response of Bacillus stearothermophilus: evidence for the existence of two distinct guanosine 3′-5′-polyphosphate synthetase. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:68–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.68-73.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galdiereo E, Donnarumma G, de Martino L, Marcatili A, de l'Ero G C, Merone A. Effect of low-nutrient seawater on morphology, chemical composition, and virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00264371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givskov M, Eberl L, Moller S, Poulsen L K, Molin S. Responses to nutrient starvation in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: analysis of general cross-protection cell shape and macromolecular content. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.7-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer B K, Swanson M S. Co-ordination of Legionella pneumophila virulence with entry into stationary phase by ppGpp. Mol Microbiol. 1999;4:721–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris B Z, Kaiser D, Singer M. The guanosine nucleotide (p) ppGpp initiates development and A-factor production in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1022–1035. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs W R, Jr, Kalpana G V, Cirillo J D, Pascopella L, Snapper S B, Udani R A, Jones W, Barletta R G, Bloom B R. Genetic system for Mycobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kochi A. TB, a global emergency. World Health Organization report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolter R, Siegele D A, Tormo A. The stationary phase of bacterial cell cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:855–874. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer G F, Baker J C, Ames B N. New UV stress in Salmonella typhimurium: 4-thiouridine in t-RNA, ppGpp, and pppGpp as components of an adaptive response. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2344–2351. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2344-2351.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahenthiralingam E, Draper P, Davis E O, Colston J. Cloning and sequencing of the gene which encodes the highly inducible acetamidase of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology. 1993;139:575–583. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-3-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marco-Noales E, Biosca E G, Amaro C. Effects of salinity and temperature on long-term survival of the eel pathogen Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 (serovar E) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1117–1126. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1117-1126.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matin A. The molecular basis of carbon-starved induced general resistance in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mechold U, Cashel M, Steiner K, Gentry D, Malke H. Functional analysis of a relA/spoT gene homologue from Streptococcus equisimilus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1401–1411. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1401-1411.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyka W. Method for acid fast and chromophobic tubercle bacilli with carbol fuchsin. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:1458–1460. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.4.1458-1460.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyka W. Studies on the effect of starvation on mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1974;9:843–850. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.5.843-850.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nystrome T, Kjelleberg S. Role of protein synthesis in the cell division and starvation induced resistance to autolysis of marine vibrio during the initial phase of starvation. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1599–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochi K, Kandala T, Freese E. Evidence that Bacillus subtilis sporulation induced by stringent response is caused by decrease in GTP or GDP. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1062–1065. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.1062-1065.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parish T, Stoker N G. Development and use of a conditional antisense mutagenesis system in mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parrish M N, Dick D J, Bishai R W. Mechanism of latency of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy P S, Raghavan A, Chatterji D. Evidence for ppGpp binding site on E. coli RNA polymerase: proximity relationship with rifampicin binding domain. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiber G, Ron E Z, Glaser G. ppGpp-mediated regulation of DNA replication and cell division in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 1995;30:27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00294520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schreiber G, Metzger S, Aizenman E, Roza S, Cashel M, Glaser G. Overexpression of the relA gene in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3760–3767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shand R F, Blum P H, Mueller R D, Riggs D L, Artz S W. Correlation between histidine operon expression and guanosine 5′-diphosphate-3′-diphosphate levels during amino acid downshifts in stringent and relaxed strains of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:737–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.737-743.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singer M, Kaiser D. Ectopic production of guanosine penta- and tetraphosphate can initiate early developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1633–1644. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smeulders M J, Keer J, Speight A R, Williams H D. Adaptation of Mycobacterium smegmatis to stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:270–283. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.270-283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spector M P, Park Y K, Tirgari S, Gonzalez T, Foster J W. Identification and characterization of starvation-regulated genetic loci in Salmonella typhimurium by using Mud-directed lacZ operon fusion. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:345–351. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.345-351.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.St. John A C, Ensign J C. Macromolecular synthesis and cell division during morphogenesis of Arthrobacter crystallopoietes. Arch Microbiol. 1976;111:51–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00446549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoker C K, de la Cruz V F, Fuerst T R, Burlein J E, Benson L A, Bennett L T, Bansal G P, Young J F, Lee M H, Hatfull G F, Snapper S B, Barletta R G, Jacobs W R, Jr, Bloom B R. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature. 1991;351:456–460. doi: 10.1038/351456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinella D, Joselean-Petit D, Thevenet D, Boulone P, D'Ari R. Penicillin-binding protein 2 inactivation in Escherichia coli results in cell division inhibition, which is relieved by FtsZ overexpression. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6704–6710. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6704-6710.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wayne G L, Hayes L G. An in vitro model for sequential study of shiftdown of mycobacterial tuberculosis through two stages of nonreplicating persistance. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2062–2069. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2062-2069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]