Abstract

Sargassum are brown algae belonging to the class Phaeophyceae. Brown algae are rich in nutrients and widely used in food. Most previous experiments have focused on the functional evaluation of organic solvent extracts of Sargassum. Considering food safety, this study investigated the antioxidant and antiobesity activities of Sargassum hemiphyllum water extract (SE). The antioxidant activity of SE (500–4000 mg/mL) was determined in vitro. The results indicated that SE has good DPPH radical scavenging activity (14–74%), reducing power (20–78%), ABTS+ radical scavenging activity (8–91%), and Fe2+ chelating ability (5–25%). Furthermore, the antiobesity activity of SE (50–300 mg/mL) was analysed in a 3T3-L1 adipocyte model. SE effectively inhibited lipid accumulation (determined by methods including measuring the absorbance of Oil red O after staining and the triglyceride content, which were decreased by 10% and 20%, respectively) by reducing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) protein expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. This study suggested that SE has good antioxidant and antiobesity properties.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13197-023-05707-1.

Keywords: Brown algae, Antioxidant, Antiobesity, Adipogenesis

Introduction

Seaweeds are macroalgae that grow in the intertidal and subintertidal zones. A previous study showed the biological activity and potential medicinal value of different kinds of seaweed (including brown algae, green algae, and red algae). These plants have been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer properties (Raghavendran et al. 2011). Sargassum hemiphyllum (S. hemiphyllum) is the largest known seaweed (algae can grow to approximately 1 to 2 m) and the most dominant, and it grows year-round in Penghu, Taiwan. It is the most abundant Sargassum in Taiwan. S. hemiphyllum consists of 87.7% water, 5.7% dietary fibre, 3.4% ash, 1% protein, and 0.1% lipids (Murakami et al. 2016). Previous studies have found that extracts of Sargassum extracted with different solvents have many functions. The acetone extract of S. hemiphyllum can inhibit AGS and HT-29 cell growth (Choi et al. 2007). Methanol extracts of S. hemiphyllum have neuronal cytoprotective effects by reducing the reactive oxygen species (ROS) contents in HT-22 cells (Shin et al. 2014). The S. hemiphyllum ethanol extract and acetone extract both have antidiabetes effects by increasing α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (Hwang et al. 2015). Organic solvents are currently employed for extraction and negatively impact health, safety, and the environment. The greenest solvent is water. It is not only affordable and ecologically safe but also nontoxic for use in food development (Chemat et al. 2019). Therefore, this study evaluated the function of the water extract of S. hemiphyllum.

Free radicals are generated in biological systems and can also be acquired from external factors. Free radicals are known to cause various degenerative diseases and conditions, such as mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, cardiovascular disease, and ageing (Singh and Singh 2008). Compounds that fight free radicals are antioxidants. Antioxidants are not only produced by biological systems but also present in many natural foods. The balance between oxidants and antioxidants determines the health and vitality of organisms. Therefore, it is important to know the amounts of antioxidants in foods and their effectiveness, which can be measured in many ways. For example, DPPH and ABTS+ radical scavenging activity, ferrous ion chelation, reducing power, etc. are used to confirm the potential antioxidant capacity of foods (Halliwell 1996).

Dietary fat intake is generally thought to contribute to increased obesity, and high-fat diets (≥ 30% of energy from fat) predispose individuals to obesity. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that excess fat accumulation contributes to obesity (WHO 2021). Obesity causes many complications, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic diseases, which can be life-threatening in severe cases (Meskin et al. 2002). Lipid metabolism in the human body is an interesting and complex process. Adipogenic factors regulate the expression of various proteins. The major transcription factors regulating adipocyte differentiation are PPARγ, C/EBPα, and SREBP-1c. In the absence of other transcription factors, activation of PPARγ can start the differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes, leading to the accumulation of large amounts of fat. A common treatment for obesity is the use of weight loss drugs, which are not only expensive but can also cause many complications, such as kidney toxicity, respiratory tract infection, indigestion, abdominal pain, oily stool, flatulence, and mental and menstrual disorders (Krentz et al. 2016). Therefore, finding natural compounds to treat or even prevent obesity is extremely important.

Previous studies have evaluated the functions of Sargassum organic solvent extracts. Considering food safety, this study reports the antioxidant and antiobesity properties of Sargassum hemiphyllum water extracts (SE).

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Uni-onward (Taipei, Taiwan). DPPH, Vitamin C, ABTS, peroxidase, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), trolox, K3Fe(CN)6, dexamethasone (Dex), 3-[4,5-Dimethyl thiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 3-isobutyl-methylxanthine (IBMX), N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl ethylenediamine (TEMED), insulin, formalin, Oil red O, and ammonium persulfate (APS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Isopropanol, methanol, FeCl2·4H2O, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), KH2PO4, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) were purchased from J.T Baker (Pennsylvania, USA). FeCl3, NaH2PO4, Na2HPO4, and KCl were purchased from SHOWA Cao. (Osaka, Japan). 30% Acrylamide, and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, USA). Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco (New York, USA).

Preparation of SE

Sargassum hemiphyllum was procured from Everyone Excellent Algae, BIO-TEC CO., LTD. (Penghu, Taiwan). The method of extraction used was that described by Tsai et al. (Tsai et al. 2022) with modifications. First, the sample was washed with clean water to remove the sand and dust impurities and then dried at 40 °C to a moisture content of less than 10%. The sample was then ground into a powder with a pulveriser to prepare Sargassum powder. Next, 10 g of Sargassum powder was mixed with 100 mL of sterilized water and then put in a 40 °C water bath. Next, the sample was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was mixed with 3 volumes of ethanol and centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 30 min. The precipitate was lyophilized after centrifugation to complete Sargassum hemiphyllum water extract (SE) sample preparation.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

One hundred microlitres of different concentrations of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) and vitamin C (1 mg/mL) were mixed with 400 μL of ethanol solution (95%) and 500 μL of DPPH solution (250 μM). Then, the mixtures were placed at 25 °C for 20 min. The optical density (OD) was measured at 517 nm, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

Relative reducing power

One hundred microlitres of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) or vitamin C (1 mg/mL) were mixed with 150 μL of K3[Fe(CN)6] (1%) and 150 μL of PBS (pH 6.6, 0.2 M). The mixtures were kept in a 50 °C water bath for 20 min and then cooled quickly. After mixing 600 μL of distilled water with 150 μL of TCA (10%) and 120 μL of FeCl2·4H2O (0.1%), the samples were shaken for 10 min in the dark. The optical density was measured at 700 nm, and the relative reducing power was calculated as follows:

ABTS+radical scavenging activity

ABTS+ was generated by reacting ABTS+ reagent (2 mM) with K2S2O8 (70 mM). The mixtures were kept in the dark for 16 h at 25 °C before use. The ABTS+ reagent was diluted with pH 6.6 PBS to produce an absorbance of 0.70–0.83 at 734 nm. Then, 990 μL of diluted ABTS+ reagent and 10 μL of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) and Trolox (1 mg/mL, as the control group) were mixed with the samples for 6 min in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm, and the ABTS+ radical scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

Ferrous ion chelating activity

Briefly, SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) and EDTA (1 mg/mL, the control group) were added to FeCl2 solution (0.05 mL, 2 mM). The samples were then mixed with 0.2 mL of ferrozine (5 mM), shaken vigorously, and left at 25 °C for 10 min. The absorbance of each solution was measured at 562 nm, and the Fe2+ chelating activity was calculated as follows:

Cell culture and preadipocyte differentiation

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were cultured in 35 mm dishes (1 × 104 cells/mL) for 2 days (starting on Day 0) with DMEM and then treated with different concentrations (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL) of SE for 8 days. The cells were stimulated with MDI medium [containing IBMX (0.5 mM), DEX (1 μM), and insulin (10 μg/mL)] for two days. Two days after MDI medium stimulation (Day 2), the cells were grown in insulin medium (10 μg/mL) for four days. After this period, the cells were grown in DMEM for an additional 2 days. Full differentiation was achieved in eight days. 3T3-L1 cells that have not undergone differentiation are called preadipocytes, and those that have undergone differentiation are called adipocytes.

MTT assay

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were treated with different concentrations (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL) of SE and grown in MDI medium for 10 days. MTT (0.1 mg/mL) was then added, and the optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm. Inhibition (%) is expressed as the percentage of viable cells when compared to the control. The cell viability results are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Lipid accumulation assays

Oil red O staining assay

Cells were stained on the 10th day using Oil Red O. The cells were washed with PBS twice. Then, formalin (1 mL, 10%) was added to fix the cells with incubation for 10 min. The sections were stained with Oil Red O for 30 min. After the Oil Red O staining solution was removed, the cells in the plates were washed in water. The stained lipid droplets were observed under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Isopropanol was added, and each mixture was shaken. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm, and the proportion of Oil Red O-stained cells (%) was determined compared to the untreated group (control).

Triglyceride deposition assay

To determine the content of triglycerides, cells were first rinsed twice with PBS. Next, 70 μL of Triton X-100 in PBS (0.5%) was used to scrape the cells into a tube before sonication (Qsonica, Connecticut, USA) for 30 s. The preset parameters were 20 kHz, 125 watts of power, and an amplitude of 80%. The samples were examined for triglyceride (TG) content with assay kits (TR212, RANDOX) and protein content. The TG contents are reported as mg TG/mg cellular protein.

Western blot analysis

The cell medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. After adding 70 μL of PBS (containing PMSF (1 mM), pH 7.4), the cells were scraped into a 1.7 mL tube. Then, the cells were disrupted by sonication for 30 s. Using Lowry’s assay, the protein content in the cell samples were analysed, using 35 μg of total protein from each sample. The protein samples were loaded onto an SDS gel (separated by 10% SDS‒PAGE) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Anti-PPARγ (1:1,000) and anti-β-actin (1:1,000) antibodies were then incubated with these membranes at 4 °C for 12 h. After that, the membranes were treated for 1 h at 37 °C with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (1:10,000). Using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (GE Healthcare), the PVDF signals were observed. The chemiluminescence in each sample was increased (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) to perform densitometry analysis and expose the blots using a ChemiDoc XRS+ system.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis program SPSS for Windows, version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to examine the data. The significance of the variation between two mean values was assessed by Duncan’s test. If the p value was < 0.05, the results were declared statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Antioxidant ability of SE

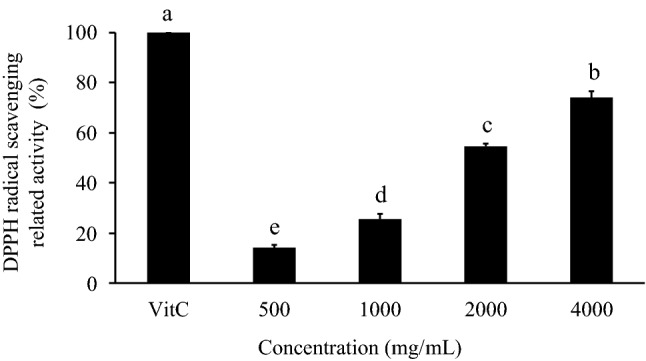

Effect of SE on DPPH free radical scavenging activity

DPPH is a stable free radical and accepts an electron or hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule (Oyaizu 1986). In the DPPH free radical scavenging activity test, the scavenging abilities of different concentrations of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) were 14.19 ± 1.16%, 25.64 ± 2.24%, 54.70 ± 1.12%, and 74.21 ± 2.22%, respectively. In the vitamin C-treated group, the observed scavenging ability was 100% (Fig. 1). Although the SE groups' ability to reduce DPPH radicals was less than that of vitamin C, the effects of SE were dose-dependent.

Fig. 1.

Effect of SE on DPPH free radical scavenging activity. The DPPH free radical scavenging effects were compared with those of vitamin C (1 mg/mL; set to 100%).The significance of the differences in activities of the different doses was evaluated by Duncan’s test. Data are the means ± SDs (n = 3). Different superscript letters (a–e) indicate significantly different DPPH free radical scavenging activities (p < 0.05)

Effect of SE on the relative reducing power

The reducing capacity of a compound may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity (Yıldırım et al. 2000). The reducing powers of different concentrations of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) were 20.20 ± 3.31%, 31.23 ± 2.46%, 55.15 ± 3.06%, and 78.31 ± 2.40%, respectively. The observed reducing power of vitamin C was 100% (Fig. 2). SE displayed a dose-dependent increase in reducing power.

Fig. 2.

Effect of SE on the relative reducing power. The free radical scavenging effects were compared with those of vitamin C (1 mg/mL; set to 100%). The significance of the differences in activities of the different doses were evaluated by Duncan’s test. Data are the means ± SDs (n = 3). Different superscript letters (a–e) indicate significantly different relative reducing power values (p < 0.05)

Effect of SE on ABTS+cation radical scavenging activity

The ABTS+ cation radical decolorization test is a spectrophotometric method widely used for the assessment of the antioxidant activity of various substances (Re et al. 1999). The scavenging abilities of different concentrations of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) were 8.00 ± 2.59%, 20.99 ± 1.18%, 42.30 ± 3.71%, and 91.41 ± 5.85%, respectively. In the Trolox-treated group, the observed scavenging ability was 100% (Fig. 3). SE showed a dose-dependent increase in ABTS+ cation radical scavenging ability. The scavenging ability of 300 mg/mL SE was close to that of 1 mg/mL Trolox.

Fig. 3.

Effect of SE on ABTS+ radical scavenging activity. The ABTS + radical scavenging effects were compared with those of Trolox (1 mg/mL; set to 100%). Duncan’s test was used to determine the significance of the differences between the activities at the various doses. Data are expressed as the means ± SDs (n = 3). Different superscript letters (a–d) indicate significant differences in ABTS+ radical scavenging activities (p < 0.05)

Effect of SE on Fe2+chelation

Since compounds that interfere with the catalytic activity of metal ions could affect the peroxidation process, measuring the chelating ability of a compound is important for evaluating its antioxidant activity (Xie et al. 2008). The Fe2+ chelating ability was determined by spectrophotometric methods. The chelating abilities of different concentrations of SE (500, 1000, 2000, 4000 mg/mL) were approximately 4.75%, 14.93%, 20.50%, and 24.72%, respectively. In the EDTA-treated group, the observed chelating ability was 100% (Fig. 4). SE displayed a dose-dependent increase in chelating ability.

Fig. 4.

Effect of SE on Fe2+ chelating power. The Fe2+ chelating power was compared with that of EDTA (1 mg/mL; set to 100%). Duncan’s test was used to determine the significance of the differences between the activities at the various doses. Data are expressed as the means ± SDs (n = 3). Different superscript letters (a–d) indicate significant differences in the Fe2+ chelating powers (p < 0.05)

Because free radicals are highly reactive molecules that come from oxygen, they are bad for organisms (Lobo et al. 2010). The antioxidant properties of the ethanol extract of S. hemiphyllum have been confirmed. The ethanol extract of S. hemiphyllum exhibited increases in DPPH radical scavenging ability, reducing power, and Fe2+ chelating power. In addition, both the ethanol and water extracts had total phenolic content values of 17.91 and 13.44 mg gallic acid equivalents/g, respectively (Park et al. 2016). Hwang et al. (2015) found that the total phenolic contents in the water and ethanol extracts of S. hemiphyllum were 17.35 ± 0.93 and 22.35 ± 1.41, respectively, and both extracts had antidiabetic properties. Previous studies have shown that the ethanol and water extracts of S. hemiphyllum have similar total phenolic contents. In this study, the results also showed that SE antioxidant effects, as displays increases in DPPH and ABTS+ radical scavenging abilities, reducing power, and Fe2+ chelating power. Moreover, organic solvent extraction is efficient and simple but also expensive. Large amounts of organic solvents are needed, which is not good for human use due to the presence of trace amounts of organic solvents in the polyphenol extracts (Shi et al. 2007). Based on the above data, the water extract also has good antioxidant activity and better safety for food development.

Antiobesity effects of SE

Effect of SE on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes

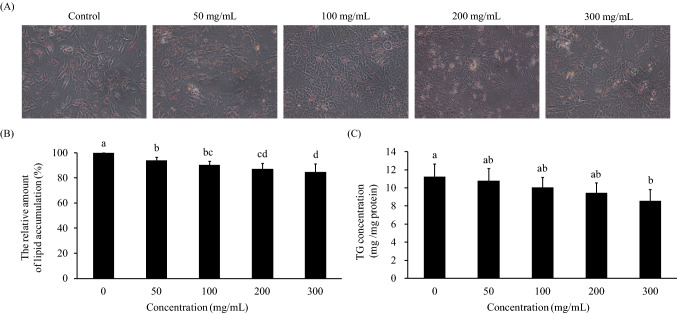

Obesity is caused by an increase in the number of preadipocytes (hyperplasia) and the hypertrophy of adipocytes (hypertrophy). When the number of preadipocytes and the content of TGs in adipocytes increase, the accumulation of body fat will lead to the occurrence of obesity. Therefore, preventing the proliferation of preadipocytes and the accumulation of TGs are important keys to preventing obesity (Jo et al. 2009). Cell viability was evaluated by MTT assays. Cells were cultured for 24 h and treated with SE (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL). The results demonstrated that cell viability did not decrease after 24 h of incubation with any concentration of SE (Supplementary Fig. S1). Then, to evaluate the amount of intracellular lipids, cells were cultured for 10 days with different concentrations of SE (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL). After 10 days, there was a change in adipocyte differentiation and a significant reduction in intracellular lipid levels (p < 0.05). SE at 300 mg/mL can reduce the TG content (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of SE on lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated by IBMX, insulin, and Dex and treated with different concentrations of SE (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL) for 10 days. Nontreated adipocytes were used as the control. A Observation of cell lipid accumulation by staining with Oil Red O (× 200). B 3T3-L1 adipocyte relative amount of lipid accumulation compared to the control (%). C Calculations were performed as follows: TG concentration (mg TG/mg protein) = mg TG/mg protein. Duncan’s test was used to determine the significance of the differences between the lipid accumulation values at the various doses. Data are expressed as the means ± SDs (n = 4). Different letters (a–c) indicate significant differences among the different SE concentrations (p < 0.05)

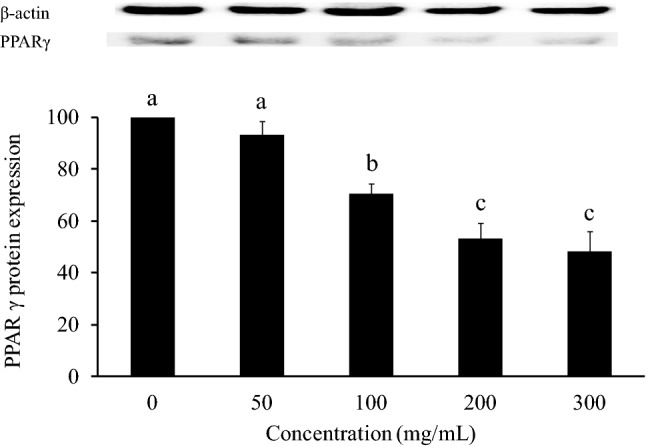

Effect of SE on PPARγ protein expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes

PPARγ is a well-known antiadipogenic marker that leads to the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation (Grun and Blumberg 2006). The antiobesity mechanism of SE can be determined by detecting the performance of PPARγ. The level of PPARγ was measured to establish whether PPARγ activation was related to the SE-mediated reduction in adipogenesis. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg/mL SE and analysed by western blotting on the 10th day (Fig. 6). SE at 100, 200, and 300 mg/mL reduced PPARγ protein expression (p < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Effect of SE on PPARγ protein expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated by IBMX, insulin, and Dex and treated with different concentrations of SE (50, 100, 200, 300 mg/mL) for 10 days. Nontreated adipocytes were used as the control. Duncan’s test was used to determine the significance of the differences in PPARγ protein expression at the various doses. Data are expressed as the means ± SDs (n = 4). Different letters (a–c) indicate significant differences among the different SE concentrations (p < 0.05)

3T3-L1 cells are widely used as a reliable cellular model to study obesity. A previous study confirmed that different concentrations of seaweed extracts have no effect on the cell viability of 3T3-L1 cells (Kim and Lee 2012a, b). The results of this study are the same as those of the previous study, confirming that SE has no effect on cell viability. To study the application of Sargassum extracts in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, the expression of adipocyte differentiation-related transcription factors was analysed. The ethanol extract of Sargassum thunbergii (EES) can inhibit the observed increase in animal body weight by regulating adipogenesis-related genes (such as PPARγ) (Kang et al. 2020). Kwon et al. found that the ethanolic extract of Sargassum serratifolium had antiobesity activity by regulating the gene expression of PPARγ, sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (Kwon et al. 2018). The Sargassum macrocarpum ethanolic extract was confirmed to inhibit lipid accumulation by 29.75 ± 2.35% (Kim 2021). However, the organic solvents used in conventional extraction techniques are harmful to human health as well as the environment (Wang and Weller 2006). Thus, considering food safety, extraction with water is safer and more environmentally friendly. There have been no previous studies on the antiobesity effect of S. hemiphyllum water extract. This study showed that SE inhibits lipid accumulation by 20% by regulating the protein expression of PPARγ. SE is an effective and safe material, and it can be applied in food development in the future.

Antioxidant and antiobesity activities of fucoidan in SE

Seaweed is known to have various biological activities. Fucoidan is one of the key polysaccharides in brown seaweeds. Sargassum hemiphyllum was extracted with hot water, and the yield of fucoidan was estimated at approximately 13.5% (Chen et al. 2022). Palanisamy et al. (2017) found that fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum had antioxidant and anticancer activities. Fucoidan from different seaweeds has antioxidant activity and antiobesity activity and improves hepatic oxidative stress (Zhang et al. 2022). Therefore, the presence of fucoidan may be one of the reasons for the antioxidant and antiobesity effects of SE.

Conclusion

This study suggested that the Sargassum hemiphyllum water extract (SE) has the ability to scavenge free DPPH and ABTS+ radicals, reducing power and Fe2+ chelating properties. In addition, SE can reduce lipid accumulation and TG deposition by regulating the protein expression of PPARγ. SE is a natural and safe food with potential antioxidant and antiobesity functions. In the future, more research can confirm the physiological function of SE for its application in the development of functional foods.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- SE

Sargassum hemiphyllum Water extract

- WHO

World Health Organization

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- C/EBPα

CCAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha

- SREBP-1c

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- DPPH

α, α-Diphenyl-β-picrylhydrazyl

- ABTS

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- Dex

Dexamethasone

- MTT

3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- IBMX

3-Isobutyl-methylxanthine

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- TG

Triglyceride

Author contributions

Conceptualization, C-CW, J-JW and S-LH; Methodology, C-CW and J-JW; Validation, Y-TC and Y-WH; Formal analysis, Y-TC; Investigation, Y-WH, T-YS and Y-TC; Data curation, Y-WH and T-YS; Writing-original draft preparation, Y-TC and Y-WH; Writing-review and editing, J-JW; Supervision, S-LH; Project administration, S-LH. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Ethics approval

The work has not been published before and it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Consent to participate

The MS has been approved by all authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ya-Ting Chen, Email: melodyyu.chen@gmail.com.

Yu-Wen Huang, Email: may2377234@gmail.com.

Tsai-Ying Shen, Email: emily0503520@gmail.com.

Chih-Chung Wu, Email: wuccmail@gmail.com.

Jyh-Jye Wang, Email: ft054@fy.edu.tw.

Shu-Ling Hsieh, Email: slhsieh@nkust.edu.tw.

References

- Chemat F, Abert Vian M, Ravi HK, Khadhraoui B, Hilai S, Perino S, Anne-Sylvie FT. Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products: panorama, principles, applications and prospects. Molecules. 2019;24(16):3007. doi: 10.3390/molecules24163007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BR, Li WM, Li TL, Chan YL, Wu CJ. Fucoidan from Sargassum hemiphyllum inhibits infection and inflammation of Helicobacter pylori. Sci Rep. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Seo YW, Lim SY. Effect of solvent extracts from Sargassum hemiphyllum on inhibition of growth of human cancer cell lines and antioxidant activity. J Life Sci. 2007;17(11):1533–1538. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2007.17.11.1533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grün F, Blumberg B. Environmental obesogens: organotins and endocrine disruption via nuclear receptor signalling. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):S50–S55. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Oxidative stress, nutrition and health. Experimental strategies for optimization of nutritional antioxidant intake in humans. Free Radic Res. 1996;25(1):57–74. doi: 10.3109/10715769609145656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang PA, Hung YL, Tsai YK, Chien SY, Kong ZL. The brown seaweed Sargassum hemiphyllum exhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity and enhances insulin release in vitro. Cytotechnology. 2015;67(4):653–660. doi: 10.3390/molecules24163007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Mullen S, Sumner AE, Cushman SW, Periwal V. Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia: dynamics of adipose tissue growth. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(3):e1000324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MC, Lee HG, Kim HS, Song KM, Chun YG, Lee MH, Kim BK, Jeon YH. Anti-obesity effects of Sargassum thunbergii via downregulation of adipogenesis gene and upregulation of thermogenic genes in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3325. doi: 10.3390/nu12113325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Antioxidant activity and cell bioactivity of Sargassum macrocarpum extract. J Korean Chem Soc. 2021;12(8):301–308. doi: 10.15207/JKCS.2021.12.8.301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Lee BY. Fucoidan from the sporophyll of Undaria pinnatifida suppresses adipocyte differentiation by inhibition of inflammation-related cytokines in 3T3-L1 cells. Nutri Res. 2012;32(6):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Lee BY. Fucoidan from the sporophyll of Undaria pinnatifida suppresses adipocyte differentiation by inhibition of inflammation-related cytokines in 3T3-L1 cells. Nutr Res. 2012;32(6):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentz AJ, Fujioka K, Hompesch M. Evolution of pharmacological obesity treatments: focus on adverse side-effect profiles. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(6):558–570. doi: 10.1111/dom.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Lim SJ, Joung EJ, Lee B, Oh CW, Kim HR. Meroterpenoid-rich fraction of an ethanolic extract from Sargassum serratifolium alleviates obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high fat-fed C57BL/6J mice. J Funct Foods. 2018;47:288–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4(8):118–126. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskin MS, Bidlack WR, Davies A, Omaye ST. Phytochemicals in nutrition and health. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2002. pp. 1–221. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Yamaguchi Y, Sugawa-Katayama Y, Katayama M. Effect of water depth on seasonal variation in the chemical composition of Akamoku, Sargassum horneri (Turner) C. Agardh Nat Resour. 2016;7(4):147–156. doi: 10.4236/nr.2016.74015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu M. Studies on product of browning reaction prepared from glucose amine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44(6):307–315. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pak WM, Kim KBWR, Kim MJ, Park JH, Bae NY, Park SH, Ahn DH. Anti-melanogenesis and anti-wrinkle effects of Sargassum micracanthum extracts. KMB. 2016;44(1):19–25. doi: 10.4014/mbl.1510.10002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy S, Vinosha M, Marudhupandi T, Rajasekar P, Prabhu NM. Isolation of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum brown algae: Structural characterization, in vitro antioxidant and anticancer activity. J Biol Macromol. 2017;102:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendran HR, Srinivasan P, Rekha S. Immunomodulatory activity of fucoidan against aspirin-induced gastric mucosal damage in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(9–10):1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Nawaz H, Pohorly J, Mittal G, Kakuda Y, Jiang Y. Extraction of polyphenolics from plant material for functional foods-Engineering and technology. Food Rev Int. 2007;21(1):139–166. doi: 10.1081/FRI-200040606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DB, Han EH, Park SS. Cytoprotective effects of phaeophyta extracts from the coast of Jeju Island in HT-22 mouse neuronal cells. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2014;43(2):224–230. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2014.43.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Singh RP. In vitro methods of assay of antioxidants: an overview. Food Rev Int. 2008;24(4):392–415. doi: 10.1080/87559120802304269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SC, Huang YW, Wu CC, Wang JJ, Chen YT, Singhania RR, Chen CW, Dong CD, Hsieh SL. Anti-obesity effect of Nostoc commune ethanol extract in vitro and in vivo. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):968. doi: 10.3390/nu14050968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Weller CL. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2006;6(1):300–312. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2005.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2021) Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 15 Aug 2022

- Xie ZJ, Huang JR, Xu XM, Jin ZY. Antioxidant activity of peptides isolated from alfalfa leaf protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2008;111(2):370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım A, Mavi A, Oktay M, Kara AA, Algur F, Bilaloglu V. Comparison of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Tilia (Tilia Argentea Desf Ex DC), Sage (Salvia triloba L.), and Black Tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:5030–5034. doi: 10.1021/jf000590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, You Y, Wang L, Ai C, Huang L, Wang S, Wang Z, Song S, Zhu B. Anti-obesity effects of Laminaria japonica fucoidan in high-fat diet-fed mice vary with the gut microbiota structure. Food Funct. 2022;13:6259–6270. doi: 10.1039/D2FO00480A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

Not applicable.