Abstract

HER2-positive breast cancer patients carrying the germline TSC2 nonsynonymous variant c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) are resistant to anti-HER2 therapy. Multi-predictor in silico analysis reveals that this variant is deleterious. We explore the potential mechanism of this TSC2 variant and investigate methods for overcoming anti-HER2 resistance. TSC2 c.4349 C > G reverses the inhibitory effect on mTOR and downstream signaling by increasing TSC2 phosphorylation at Thr1462 and confers significant lapatinib resistance in vitro and in vivo. The combination of lapatinib and the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib inhibits cyclin D1/CDK4/Rb alternative pathway and TSC2 phosphorylation, thereby partially attenuating mTOR activity and inducing TSC2-mutant cell blockage at G1/G0. In in vitro and xenograft models, palbociclib+lapatinib shows higher anti-tumor activity than monotherapy and overcomes the resistance of the TSC2 c.4349 C > G-related variant to anti-HER2 therapy. We reveal a new mechanism of resistance to anti-HER2 therapy and provide a strategy to increase the efficiency of anti-HER2 therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Cancer therapeutic resistance

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer, with the highest incidence rates, among women1,2. Estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) are important biological markers of breast cancer3. Currently, several HER2-targeted therapies are used to treat HER2-positive breast cancer. Trastuzumab is a humanized anti-HER2 antibody targeting the extracellular domain of HER24. Lapatinib is an oral reversible tyrosine kinase inhibitor that specifically inhibits HER1 and HER2 and the activity of their downstream signaling pathways5. Mutations in the genes involved in the HER2 pathway are the driving forces underlying resistance to anti-HER2 therapy6. The HER2/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signal node is one of the most extensive signaling pathways involved in human cancers7 and participates in the control of cell metabolism, movement, proliferation, growth, survival, and other cellular processes8.

Germline pathogenic mutations in tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1) or TSC2 causes tuberous sclerosis, an autosomal dominant genetic disease characterized by the development of hamartomas in multiple organs or tissues, including the skin, brain, eyes, lungs, heart, and kidneys9. TSC1 and TSC2 exist in the cells as the TSC1/TSC2 complex, which acts as a GTPase-activating protein for the GTPase homolog enriched in the brain (Rheb)10. TSC2 can convert the GTP form of Rheb into the GDP form, thereby inhibiting the activity of Rheb and blocking the mTOR pathway. Functional loss of TSC2 results in constitutive activation of Rheb and its downstream mTOR signaling11. Palbociclib, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, can inhibit the cyclin D1/CDK4/Retinoblastoma (Rb) alternative pathway and indirectly reduce the phosphorylation level of Thr1462 in TSC2, thereby suppressing the activity of mTOR and alleviating feedback inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family kinases12. This process improves the sensitivity of the cells to the effects of anti-HER2 therapy. Thus, targeted therapy (trastuzumab or lapatinib) combined with CDK4/6 inhibitors is a promising strategy for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer.

In our clinical practice, a HER2-positive patient with the TSC2 (NM_000548) c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) germline nonsynonymous variant was found to be resistant to trastuzumab (administered as part of a neoadjuvant therapy). Thus, in this study, we aimed to construct stable TSC2 mutant and wild-type cell lines to investigate the mechanism of action of this anti-HER2-resistant variant. We also verified our results using cell-derived xenografts and clinical specimens and identified a novel strategy to improve the efficacy of anti-HER2 therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer.

Results

Resistance to anti-HER2 therapy in a breast cancer patient with TSC2 c.4349 C > G (p. Pro1450Arg) germline variant

The patient, diagnosed with Luminal B (HER2 positive) breast cancer, showed progress after anti-HER2 neoadjuvant treatment (including trastuzumab) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 guidelines (Fig. 1a). TSC2 germline nonsynonymous variant (NM_000548.5, rs45517338) c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) was identified in the patient by a 98-gene panel sequencing assay (genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1), which was demonstrated conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity (either “likely benign” or “of uncertain significance”). The highest-population minor allele frequency of guanine (G) was lower than 0.01, as determined by 1000 Genomes Phase 3, ESP, and gnomAD. The variant was predicted as being damaging and probably damaging by SFIT and PolyPhen-2 in silico analysis, respectively. Whole-exome sequencing suggested that none of the other somatic alterations were associated with resistance to anti-HER2 treatment (Supplementary Table 2).

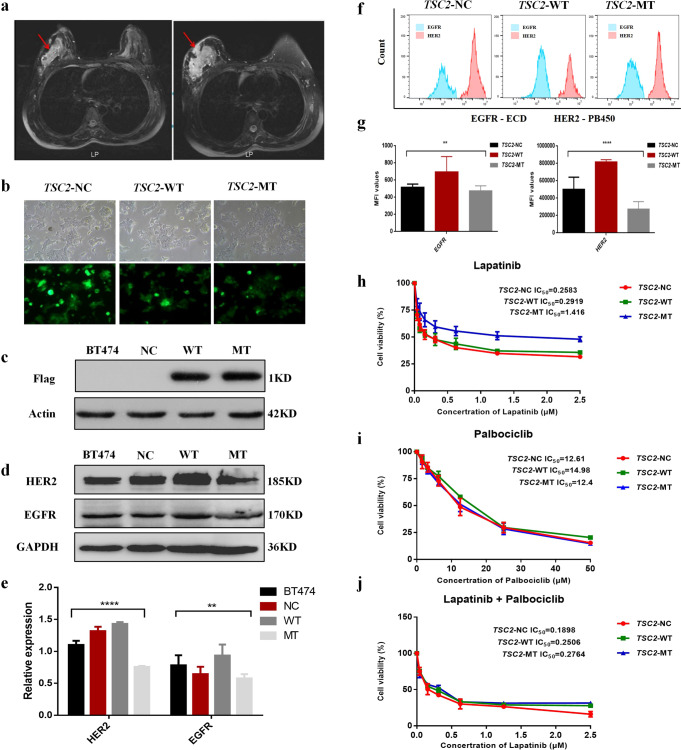

Fig. 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals a clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy containing trastuzumab in a breast cancer patient with the TSC2 c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) variant and mutant TSC2 conferring resistance to lapatinib.

a Left: Breast MRI scan captured before trastuzumab treatment initiation. Right: Follow-up image captured after trastuzumab treatment initiation, showing considerable tumor enlargement after four treatment cycles. b Three groups of lentiviruses were added to the BT474 culture to validate the transfection efficacy using fluorescence microscopy. Images in b are at ×20 magnification. Scale bar for each image is 1 cm. c Expression of the FLAG tag in the TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT groups was determined via western blotting. d Expression of EGFR and HER2 in BT474, TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT cells was determined via western blotting. e Relative expression of EGFR and HER2 in BT474, TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT. (f) Expression of EGFR and HER2 in TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT cells was determined by flow cytometry. g Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of EGFR and HER2 in TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT cells. h IC50 values of lapatinib for the TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT groups are 0.2503 μM, 0.2919 μM, and 1.416 μM, respectively. Overexpression of TSC2-MT enhanced lapatinib resistance compared with that of TSC2-WT (P < 0.001). i Inhibition curve of the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib. j Under combined treatment with palbociclib and lapatinib, palbociclib concentration was fixed (IC20 = 5 μM). IC50 values of lapatinib for the TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT groups are 0.1838 μM, 0.2506 μM, and 0.2764 μM, respectively. Data are shown as mean± (Standard Deviation) SD; Data in (E, G, H, I, J) were analyzed with one-way ANOVA. Error bars are standard error of mean (SEM). **P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001.

Mutant TSC2 confers resistance to lapatinib

As the patient carrying the TSC2 c.4349 C > G variant was resistant to trastuzumab, we constructed plasmids to investigate the role of the variant in mediating resistance to anti-HER2 therapy using the BT474 cell line. We first observed transfection efficiency using a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1b). The expression of FLAG-tagged target protein was verified using western blotting (Fig. 1c). EGFR and HER2 expression were detected by western blotting in four groups of cells: BT474, TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT (Fig. 1d). As shown in Fig. 1e, the expression of HER2 was significantly higher than that of EGFR in all four groups of cells, and the expression levels of HER2 and EGFR were significantly lower in the MT group than in the other three groups (n = 4, F = 107.7, P = 0.0001 and F = 4.21, P = 0.046, respectively; one-way ANOVA). To differentiate the expression of EGFR and HER2 in the NC, WT, and MT groups, we quantified the expression of these growth factor receptors in the different cell lines, using flow cytometry (Fig. 1f). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of EGFR in the NC, WT, and MT groups were 516.7 ± 15.3, 695 ± 72.5, and 476 ± 22.5, respectively. There were significant differences in the MFIs among these three groups (n = 3, F = 20.28, P = 0.0021; one-way ANOVA). The MFI values of HER2 were 5.02 × 105 ± 55770, 8.32 × 105 ± 15620, and 2.76 × 105 ± 34100, respectively (Fig. 1g). The MFI was significantly different among the three groups (n = 3, F = 151.8, P = 0.0001; one-way ANOVA). The inhibitory effect of the drugs on cell growth was dependent on the drug concentration. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of lapatinib in the NC, WT, and MT groups were 0.2583, 0.2919, and 1.416 μM, respectively. Compared with the WT and NC groups, the MT group showed a significantly higher drug resistance (n = 3, F = 36.25, P = 0.0001; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 1h). However, no significant difference was noted with respect to palbociclib monotherapy in these three groups of cells (n = 3, P > 0.05; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 1i). When lapatinib was combined with palbociclib, the concentration of palbociclib was fixed (IC20 = 5 μM). The IC50 values of lapatinib in the WT and MT groups were 0.2506 and 0.2764 μM, respectively. Furthermore, there was no significant difference among the three groups of cells in the combination group (n = 3, P > 0.05; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 1j).

Finally, we compared the effects of the two drugs as a function of the concentrations of lapatinib, palbociclib, and lapatinib+palbociclib. The drug combination index (CI) was calculated for the WT and MT groups when the two drugs were combined. The CI of lapatinib+palbociclib in both groups was <1, indicating a synergistic effect. Lapatinib demonstrated a synergistic sensitization effect at concentrations lower than 0.25 μmol/L. The CI values at IC50 for the WT and MT groups under the two-drug combination condition (for lapatinib alone, WT was 0.2608 μM and MT was 0.2764 μM) were 0.502 and 0.312, respectively. The synergistic sensitization effect of the two drugs was more evident in the MT group than in the WT group.

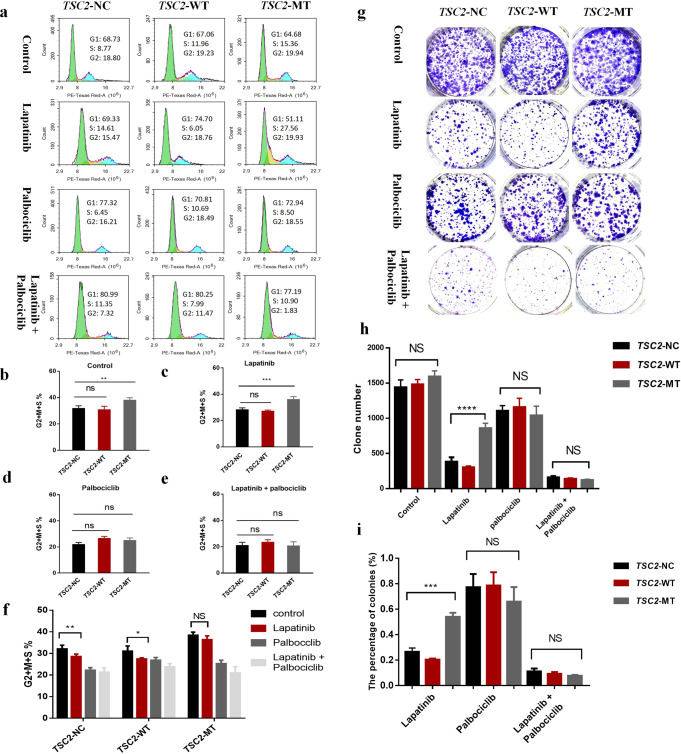

Palbociclib induces G1 arrest in HER2-amplified BT474 cells

The results of the cell cycle assay are shown in Fig. 2a. In the untreated group, the proportion of cells in the G2 + S + M phase of the TSC2-MT group (38.33 ± 1.53) was significantly higher than that of the other two groups (NC: 32.10 ± 1.71, WT: 31.07 ± 2.41; n = 3, F = 12.58, P = 0.0071; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 2b). When exposed to lapatinib, the MT group (36.34 ± 1.82) showed a significantly higher proportion of cells in the G2 + M + S stages than that in the WT and NC groups (WT: 27.43 ± 0.57, NC: 28.51 ± 0.57; n = 3, F = 42.19, P = 0.0003; one-way ANOVA). Collectively, TSC2-MT was more resistant to lapatinib than TSC2-WT, demonstrated by an increase in cell proliferation (Fig. 2c). The proportion of G2 + M + S cells in the MT group was significantly lower after palbociclib monotherapy (25.27 ± 1.60) than after lapatinib monotherapy (36.34 ± 1.82, n = 2, t = 7.93, P = 0.0014; T test). After incubation with palbociclib, no significant difference was observed among the three groups (Fig. 2d). Moreover, when compared to the results observed after the use of lapatinib, the proportion of cells in the G2 + M + S proliferation phase was significantly reduced upon combined treatment with lapatinib and palbociclib (Fig. 2e). Compared with that in the control group, lapatinib treatment could reduce the proportion of G2 + M + S phase cells in the NC and WT groups (n = 2, t = 2.9, P = 0.004; t = 2.78, P = 0.049; T test; Fig. 2f), although the inhibition of the cell cycle by lapatinib was not significant in the MT group. However, there was no difference in the proportions of G2 + S + M phase cells in all three groups after treatment with palbociclib (Fig. 2d). These results indicated that the combination of the two drugs could induce blockage of most cells at G1/G0, thereby slowing down cell proliferation.

Fig. 2. Cell cycle and colony-forming ability of BT474 cell lines treated with lapatinib and/or palbociclib.

a Cell cycle analysis of BT474 cell lines treated with lapatinib and/or palbociclib. b Proportion of G2 + M + S cells in the TSC2-MT group increased compared with that in the TSC2-WT and TSC2-NC groups without treatment (n = 3, F = 12.58, P = 0.0071; one-way ANOVA). c TSC2-MT group showed an increased proportion of cells in the G2 + M + S stages compared to the other two groups on lapatinib treatment (n = 3, F = 42.19, P = 0.0003; one-way ANOVA). d Three groups of cells showed a similar proportion of cells in the G2 + M + S stages upon palbociclib treatment. e Under the lapatinib + palbociclib treatment, the proportion of cells in the G2 + M + S stages was not significantly different among the three groups. f Cell cycle comparison under control, lapatinib, palbociclib, or lapatinib+palbociclib treatments within the same cell line. g Representative images of colony staining for the three BT474 cell lines treated with control, lapatinib, palbociclib, and lapatinib+palbociclib. h Colony count comparison in the three groups treated with lapatinib and/or palbociclib. The TSC2-MT group showed significantly higher colony counts than the TSC2-WT and TSC2-NC groups on lapatinib treatment (n = 3, F = 85.54, P = 0.0001; one-way ANOVA). However, under conditions involving stress induced by both lapatinib and palbociclib, the colony-forming ability of the three groups did not significantly differ (n = 3, F = 3.5, P = 0.098; one-way ANOVA). i Clone number rate comparisons relative to the control after lapatinib and/or palbociclib treatment. In the lapatinib group, the clone number rate in the TSC2-MT group was higher than that in the other two groups (n = 3, F = 92.83, P = 0.0004; one-way ANOVA). Data are shown as mean ± SD; data in b, c, d, e, f and I were analyzed with two-tailed T test and one-way ANOVA. Error bars are SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Combination of lapatinib and palbociclib effectively reduces the ability of cells to form colonies in vitro

We conducted colony formation assays to determine the antitumorigenic effect of lapatinib, palbociclib, and a combination of the two drugs on the three groups of cells (Fig. 2g). There was no significant difference in the number of clones among the three control groups. We then explored the colony-forming ability of the cells under conditions involving lapatinib-induced stress. No significant difference was observed in the number of clones between the TSC2-WT (301.7 ± 20.79) and TSC2-NC (382.3 ± 63.2) groups (t = 2.1, P = 0.078; T test). However, the number of colonies was higher in the TSC2-MT (625.3 ± 31.5) group than in the other two groups (n = 3, F = 85.54, P = 0.0001; one-way ANOVA), indicating that the MT group showed significant resistance to lapatinib compared to the WT and NC groups. In the case of palbociclib treatment, no significant difference was observed among the three cell groups. In the case of combination treatment, no significant difference was observed among the NC, WT, and MT groups (129 ± 5.77, 152 ± 18.1, and 137.3 ± 35.9.4, respectively; n = 3, F = 3.5, P = 0.098; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 2h). Owing to the difference in the transfection efficiency of the three groups of cells, the number of clones treated with lapatinib, palbociclib, and the two-drug combination was compared with that of the control group. The percentage of colonies relative to the control in lapatinib-treated cells for the MT group was significantly higher than that for the other two groups (n = 3, F = 92.83, P = 0.0004; one-way ANOVA). However, there was no significant difference in the percentage of cells after palbociclib treatment (n = 3, F = 1.24, P = 0.3347; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 2i). These results indicate that palbociclib increased sensitivity to lapatinib.

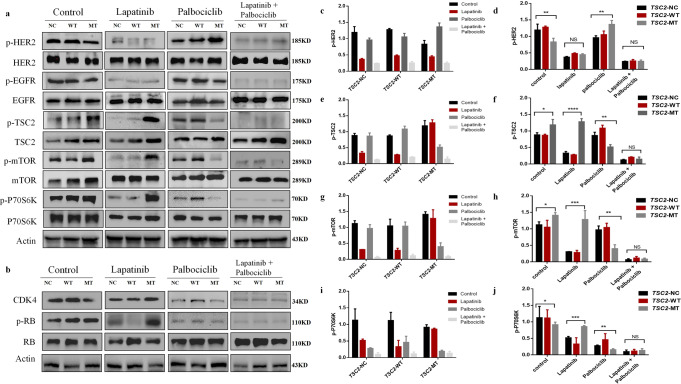

The HER2 pathway is associated with the phosphorylation levels of TSC2

We examined potential associated carcinogenic signaling pathways (Fig. 3a, b). In the untreated group, the total expression and phosphorylation levels of HER2 in the TSC2-MT group were significantly lower than those in the TSC2-NC and TSC2-WT groups (n = 3; F = 11.09, P = 0.0097; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3c, d). Under conditions of lapatinib treatment, the phosphorylation levels of HER2 in the NC, WT, and MT groups were all significantly lower than those without treatment. Palbociclib treatment increased the phosphorylation of EGFR and HER2 in all three groups, particularly the phosphorylation of HER2 in the MT group (n = 3; F = 13.13, P = 0.0064; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3d). The inhibition of HER2 became more pronounced after combination treatment. Western blotting results showed that in the untreated group, Thr1462 phosphorylation of TSC2 was higher in the MT group than in the other two groups (n = 3; F = 8.982, P = 0.016; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3e, f). Phosphorylation of mTOR and P70S6K was also significantly higher in the MT group than in the NC and WT groups (n = 3; F = 5.638, P = 0.0419 and F = 9.897, P = 0.0126, respectively; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3h, i, j). Regarding the TSC2 mutation, the phosphorylation levels of TSC2 and mTOR in the MT group were not inhibited by lapatinib, although they were inhibited in the NC and WT groups (n = 3; F = 244.1, P < 0.0001 and F = 37.06, P = 0.0004, respectively; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3g, h). These results show that the TSC2 c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) variant upregulated signaling pathways and enhanced lapatinib resistance with an increase in the phosphorylation level of TSC2.

Fig. 3. Expression of proteins involved in the HER2/AKT/mTOR and cyclinD1/CDK4 signaling pathways in BT474 cell lines treated with lapatinib and/or palbociclib.

a Western blot analysis of proteins involved in the HER2/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway after treatment with lapatinib and/or palbociclib for 48 h. b Western blot analysis of proteins involved in the cyclinD1/CDK4 signaling pathway after treatment with lapatinib and/or palbociclib for 48 h. c p-HER2 expression levels under treatment with different drugs in the same cell. d p-HER2 expression levels in TSC2-NC, WT, and MT groups treated with the same drugs. e p-TSC2 expression levels under treatment with different drugs in the same cell. f p-TSC2 expression levels in TSC2-NC, WT, and MT groups treated with the same drugs. g p-mTOR expression levels under treatment with different drugs in the same cell. h p-mTOR expression levels in TSC2-NC, WT, and MT groups treated with the same drugs. i p-P70S6K expression levels under treatment with different drugs in the same cell. j p-P70S6K expression levels in TSC2-NC, WT, and MT groups treated with the same drugs. Data are shown as mean ± SD; One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data in (d, f, h, j). Error bars are SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005, ****P < 0.0001.

Next, we sought to determine how palbociclib suppressed P70S6K activity and relieved feedback inhibition on EGFR and HER2 in the MT group. Cyclin D1/CDK4 binds to and regulates the phosphorylation level of TSC213, and palbociclib is a CDK4/6 inhibitor. In the MT group, the levels of p-TSC2, p-mTOR, and p-P70S6K were significantly lower than those in the NC and WT groups under palbociclib treatment (n = 3; F = 32.23, P = 0.001, F = 24.52, P = 0.0013, and F = 32.23, P = 0.0006, respectively; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3f, h, j). Increased P70S6K activity is known to enhance the feedback inhibition of EGFR family kinase signaling13. After treatment with palbociclib, the phosphorylation levels of HER2 in the MT group were higher than those in the other two groups (Fig. 3d).

After lapatinib treatment, the expression of CDK4 and p-Rb was higher in the MT group than in the other two groups (Fig. 3b). Palbociclib was able to downregulate the expression of CDK4 and p-Rb in all three groups (Fig. 3b). The lapatinib + palbociclib combination completely inhibited the phosphorylation of the proteins involved in the TSC2, EGFR, HER2, and Rb pathways, with no significant differences observed among the three groups. Thus, palbociclib may have enhanced the effect of lapatinib on cells by inhibiting CDK4/6 and TSC2/mTOR signaling pathways.

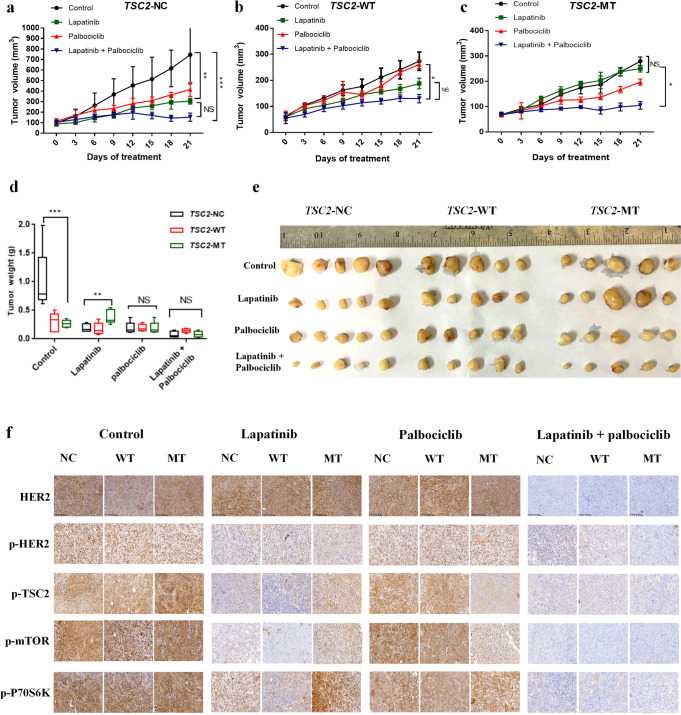

Lapatinib and palbociclib suppress the growth of HER2-positive breast cancer cells in xenograft models

Based on the tumor growth curve, the increase in tumor volume in the TSC2-NC group was significantly different in the control and lapatinib groups (F = 8.187, P = 0.0005; one-way ANOVA). A significant difference was also observed between the control and combination therapy groups (F = 22.33, P = 0.0001; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 4a). Moreover, in the TSC2-WT group, a significant difference was observed in the tumor volume between the palbociclib and combination treatments (F = 1.809, P = 0.001; one-way ANOVA); however, combination therapy showed no significant inhibitory effect over lapatinib monotherapy in this group (F = 2.529, P = 0.0776; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 4b). In the TSC2-MT group, no significant difference was observed between the growth curves for the lapatinib and control treatments, indicating that lapatinib had no significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth in this group. However, when compared with the lapatinib group, the combination group showed significantly inhibited tumor growth (F = 3.531, P = 0.0275; one-way ANOVA Fig. 4c). The combination of lapatinib and palbociclib exerted a stronger inhibitory effect on the growth of xenografts than either drug alone.

Fig. 4. Tumor volume and weight in mice harboring BT474 cell lines treated with lapatinib and/or palbociclib.

a, b, and c Cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice and continuously observed for 21 days. Tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into four groups: control, lapatinib treatment (80 mg/kg/d), palbociclib treatment (100 mg/kg/d), and combination treatment (80 mg/kg/d + 100 mg/kg/d) for 21 days. Relationship between in vivo tumor growth rate and days after drug treatment for TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT cells. Tumor volumes were measured every 3 days after drug treatment. d After day 21 treatment, the tumors from the control, lapatinib, palbociclib, and combination groups were dissected and weighed. Box plots indicate median and interquartile range. The lower and upper hinges correspond to the first (25th percentile) and third (75th percentile) quartiles, respectively. e Images of the tumors captured after 21 days of continuous drug administration. The first tumor of the TSC2-NC group in the control was too large, so only half of it is shown in the figure for representative purposes. Scale bar for each image is 1 cm. f Representative IHC results showing HER2, p-HER2, p-TSC2, p-mTOR, and p-P70S6K expression in BT474 tumors after different drug treatments in the xenograft models. IHC images in (f) are at ×20 magnification, scale bar: 100 μm. Data are shown as mean ± SD; one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data in (a, b, c, d). Error bars are SEM. **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

In the absence of treatment, tumor growth in the NC group was significantly higher than that in the other two groups (NC = 0.99 ± 0.56 g, WT = 0.29 ± 0.07 g, and MT = 0.26 ± 0.06 g; n = 3, F = 7.60, P = 0.0074; one-way ANOVA). With lapatinib alone, tumor weight in the MT (0.385 ± 0.121 g) group was significantly higher than that in the NC and WT groups (NC: 0.195 ± 0.07 g, WT: 0.177 ± 0.108 g; n = 3, F = 6.45, P = 0.0125; one-way ANOVA). These results showed that for the MT group, tumor weight was significantly lower in mice injected with a combination of the two drugs (0.086 ± 0.052) than in mice injected with lapatinib alone (0.385 ± 0.121, n = 2, t = 5.09, P = 0.0009; T test). In the case of combination treatment, no significant difference was observed in tumor weight among the three groups (n = 3, F = 0.462, P = 0.147; one-way ANOVA). In summary, the in vivo experiment results revealed that the MT group showed resistance to lapatinib. The combination of lapatinib and palbociclib was shown to markedly inhibit the relative growth of tumors and enhance anticancer activity, compared with lapatinib monotherapy (Fig. 4d).

Immunohistochemistry

We verified that the two drugs (either alone or in combination) inhibited tumor growth in a HER2-amplified breast cancer xenograft mouse model. Given that the first tumor of the TSC2-NC control group treatment was too large, the image of half of the tumor is presented in Fig. 4e. To support these results, we performed immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis using mouse tumor tissues (Fig. 4f). In three groups of xenografts, lapatinib significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of HER2, while palbociclib increased the phosphorylation of HER2. The lapatinib-treated tumor tissues showed reduced expression of p-mTOR, p-TSC2, and p-P70S6K in the TSC-NC and TSC2-WT groups. However, the expression of these proteins was not significantly reduced in the TSC2-MT group. The combination of lapatinib and palbociclib resulted in a greater reduction in the phosphorylation of TSC2, mTOR, and P70S6K. These results are consistent with those obtained at the cellular level and confirm the benefits of the combined approach targeting CDK4/6 and HER2 and their downstream pathways.

Discussion

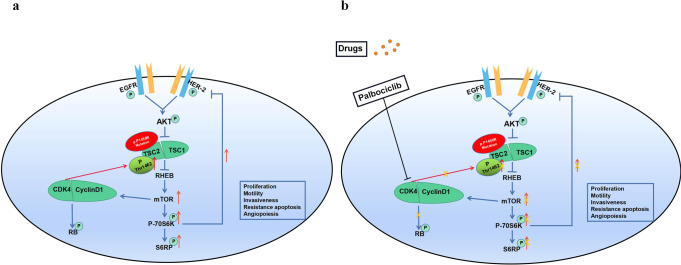

Approximately 6000 variants of TSC2 are registered in ClinVar (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ClinVar/), including over 700 pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations leading to TSC. TSC2 c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) was classified as a variant demonstrating conflicting interpretations of pathogenicity. This variant has been mentioned in previous studies; however, its function has not been analyzed and its clinical significance remains unknown14. The HER2-positive breast cancer patient harboring the TSC2 germline nonsynonymous variant c.4349 C > G was resistant to trastuzumab administered during neoadjuvant therapy. The present study found that this variant promoted the phosphorylation of Thr1462 in TSC2, which enhanced the activation of mTOR and its downstream signals and increased the number of cells in the G2 + M + S phase of the cell cycle, leading to the development of resistance to lapatinib (Fig. 5a). However, palbociclib also inhibited the cyclinD1/CDK4-Rb alternative pathway, indirectly reducing the phosphorylation of Thr1462 in TSC2 by inhibiting the binding between CDK4 and TSC2 (Fig. 5b). A previous study found that pathogenic mutations in TSC2 and TSC1 disrupt the functional complex formed by the protein products of these two genes that influence mTOR signaling, leading to constitutive mTORC1 activation15. The in vivo targeting effect of rapamycin can eliminate TSC2-null xenograft tumor model growth, induce apoptosis, increase the survival rate of tumor-bearing mice, and prevent tumor regeneration after treatment16. Thus, the TSC2 c.4349 C > G variant was found to be related to anti-HER2 treatment resistance.

Fig. 5. Palbociclib reverses anti-HER2 resistance induced by the TSC2 c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) variant.

a Phosphorylation level of TSC2 p.Pro1450Arg mutant on Thr1462 increased, which led to activation of the mTOR pathway. In addition, phosphorylation levels of mTOR and P70S6K increased. P70S6K partially suppresses the RTK signal of EGFR family members via negative feedback. The potential mechanism of increased phosphorylation in the TSC2 p.Pro1450Arg variant on Thr1462 might be caused by cyclin D1/CDK4 binding to and regulating the phosphorylation level of TSC2. b After palbociclib treatment, the activation of CDK4 was inhibited, leading to decreased phosphorylation of TSC2, mTOR, and P70S6K. As a result, the feedback inhibition of the EGFR family by P70S6K was attenuated. Moreover, palbociclib effectively inhibited Rb phosphorylation, resulting in some cells stagnating in the G1 phase. (p: phosphorylation).

Our results showed that the combination of lapatinib and palbociclib could block the cell cycle in the G1 phase and that palbociclib could re-sensitize TSC2-mutant cells to anti-HER2 therapy. Zhang et al.17 also found that a combination of palbociclib and pyrotinib induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and strongly inhibited tumor cell proliferation and colony formation. In this study, the combined treatment significantly reduced p-mTOR activation and increased tumor cell apoptosis. Goels et al.18 revealed that dual inhibition of HER2 and CDK4/6 induces a highly potent suppression of TSC2 phosphorylation, thereby markedly blocking mTORC1/S6K/S6RP activity. Consequently, CDK4/6 inhibition could restore the sensitivity of drug-resistant tumor cells to the effects of HER2 inhibitors. These studies demonstrate a possible mechanism underlying these synergistic effects. The cyclinD1/CDK4 pathway promotes cell proliferation via phosphorylation of Rb19. Zacharek et al.13 reported that cyclinD1/CDK4 could bind to TSC2 and upregulate its phosphorylation, thereby negatively affecting the stability of the TSC1/TSC2 complex. A related study20 has shown that the expression of wild-type TSC2 could reduce mTORC1 activity, which is further downregulated after treatment with CDK4 inhibitors. In our study, inhibition of CDK4/6 led to the downregulation of mTOR signaling with a reduction in the phosphorylation of the Thr1462 residue of TSC2 in TSC2-mutant cells. As expected, the phosphorylation levels of both mTOR and P70S6K were decreased, indicating that CDK4/6 inhibitors could inhibit the binding of CDK4 and TSC2. This led to a reduction in the phosphorylation of TSC2 (p1462) and inhibition of the mTOR pathway11.

In our study, the lapatinib + palbociclib combination treatment, targeting the HER2/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and inhibiting the CDK4/6-Rb bypass pathway, significantly inhibited the survival of tumor cells and induced apoptosis. These findings were also supported by the results of the xenograft model experiments. A recent study21 demonstrated that dysregulation of the CCND1–CDK4/6‐Rb axis contributes to pyrotinib resistance, and that CDK4/6 inhibitor (SHR6390) sensitizes pyrotinib in a HER2‐positive advanced gastric cancer mouse model. Our data confirmed the sensitizing effect of a CDK4/6 inhibitor on lapatinib and suggested mechanisms by which lapatinib and palbociclib synergistically work against HER2 therapy-resistant breast cancer in a nude mouse model. The combination of a CDK4/6 inhibitor and anti-HER2 treatment has demonstrated a high response rate and is well-tolerated in patients.

Our study has shortcomings that should be noted. We used lapatinib, and not trastuzumab, to investigate the resistance of anti-HER2 treatment in the BT474 cell line overexpressing the TSC2 mutant, as trastuzumab and lapatinib can both inhibit HER2. Additionally, lapatinib can inhibit HER1, and trastuzumab induces apoptosis of cancer cells by blocking the HER2 signal pathway and the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity effect, which could lead to different anti-cancer effects and mechanisms of resistance. The patient carrying the TSC2 c.4349 C > G variant was resistant to trastuzumab in neoadjuvant treatment, making it more meaningful to test trastuzumab rather than lapatinib in this study. We also employed two-dimensional (2D) culture in this study, which could impose some limitations. Cells grown in a 2D culture environment are generally flatter and more extended than those grown in vivo. Moreover, the abnormal cell morphology in 2D cultures affects cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and gene expression. These limitations could be avoided by using three-dimensional (3D) culture, which is capable of modeling normal cell growth in vivo. Pickl et al.22 found that a 3D culture system might better reflect HER signaling than 2D culture. Rodríguez et al.23 suggested that 3D architecture could modify breast cancer cell response to trastuzumab by modulating stem cell population and HER2 distribution. Tatara et al.24 reported increased expression of cleaved PARP and a decreased ratio of p-AKT to AKT in 3D-cultured PIK3CA-WT HER2-positive cell lines in response to trastuzumab, but not in 2D-cultured PIK3CA-WT lines. As 3D culture could better reflect HER signaling conditions and trastuzumab action in vivo, it will be employed in future studies to further assess the trastuzumab resistance mechanism in TSC2-MT and HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify that the TSC2 (NM_000548) c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg) variant could activate the HER2/AKT/mTOR pathway. This variant is related to anti-HER2 resistance and could be controlled by CDK4/6 inhibition. We demonstrate a new mechanism underlying anti-HER2 resistance and provide the rationale for using a combination of anti-HER2 and CDK4/6 inhibitors in HER2-positive breast cancer.

Methods

Patient and next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the use of samples and information, as well as for the publication of results. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, China (IRB-2017-199).

A 33-year-old female patient was diagnosed with stage IIIA (cT3N1M0) breast cancer in August 2016. IHC demonstrated the following results: HER2 (3+), ER (+, 20%), PR (−), and Ki-67 (+, 70%). The molecular type was luminal B (HER2 positive). From August 22, 2016, to January 10, 2017, the patient underwent neoadjuvant treatment as follows: AC*4 regimen (doxorubicin+cyclophosphamide) followed by PH*4 regimen (paclitaxel+trastuzumab). Treatment efficacy was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 guidelines25.

Genomic DNA was prepared using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN, catalog number 51104, Hamburg, Germany) from peripheral blood samples. A 98-gene panel sequencing assay was employed to analyze the germline mutations in HiSeq X-Ten (Illumina, catalog number 56404, San Diego, CA, USA), as the patient was diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer for hereditary screening (the 98 genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1). The total DNA was extracted using an FFPE DNA extraction kit (QIAGEN, catalog number 51104). Whole-exome capture was performed using SureSelect Human All Exon V6 Kit (Agilent Technologies, catalog number 5190-8863, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed using the Illumina Novaseq 6000. Somatic SNVs and InDels were jointly called by Mutect226. Annovar was utilized to add biological information to a set of variants (https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/).

Cell culture

The breast cancer cell lines BT474 (NICR, Procell, catalog number CL-0040) and HEK293T (NICR, Procell, catalog number CL-0005) were purchased from the Chinese National Infrastructure of Cell Line Resource (NICR) and tested for mycoplasma contamination. The cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Jinuo Biomedical Technology, Hangzhou, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Jinuo Biomedical). The cells were grown at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide with saturated humidity. Only cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested for subcutaneous inoculation.

Overexpression of mutant TSC2

The cells were divided into three groups, i.e., negative control (NC), wild-type TSC2 overexpression (TSC2-WT), and mutant TSC2 overexpression (TSC2-MT). The TSC2-WT sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction at the restriction site (BamHI/AgeI) and recombined into the vector GV492_Ubi-MCS-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin. (catalogue number GV492). The variant site of TSC2 was c.4349 C > G (p.Pro1450Arg), and the corresponding specific primers are as follows: F, 5’-CGCTATGTGGATACGCTGCTTTA-3’ and R, 5’-GCAACCAGGATTTATACAAGGAGGA-3’. Similarly, TSC2-MT was amplified at the BamHI/AgeI site and recombined into the vector GV492_Ubi-MCS-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin. The recombinant construct was verified by sequencing and then packaged with lentivirus. The virus was collected after 48 h to determine the concentration and titer. This lentivirus was used to transduct 293 T cells, and transduction efficiency was determined under a fluorescence microscope. After screening with puromycin (1 µg/mL), the expression of the target protein was determined via Western blotting.

Western blotting

The cells were collected and homogenized in a lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 30 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 12000 g at 4 °C for 10 min and supernatants were collected. Before blotting, protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (HyClone-Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). For each group, protein samples were separated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were first blocked in milk and then probed with different antibodies, such as rabbit anti-TSC2 (catalog number 24601-1-AP, 1:1000 dilution, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), rabbit anti-mTOR (catalog number 28273-1-AP, 1:1000 dilution, Proteintech), rabbit anti-P70S6K (catalog number 14485-1-AP, 1:1000 dilution, Proteintech), mouse anti-GAPDH (catalog number 60004-1-Ig, 1:2000 dilution, Proteintech) and mouse anti-actin (catalog number 66009-1-Ig, 1:2000 dilution, Proteintech) antibodies. Additionally, rabbit anti-p-mTOR (Ser2448, catalog number 5536, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), rabbit anti-p-P70S6K (Thr389, catalog number 9234, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-CDK4 (catalog number 12790, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-Rb (catalog number 9309, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-p-Rb (Ser807/811, catalog number 8516, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology) as well as rabbit anti-p-TSC2 (Thr1462, catalog number AF3334, 1:1000 dilution, Affinity Biosciences, Cincinnati, OH, USA), rabbit anti-HER2 (catalog number AF7681, 1:1000 dilution, Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-p-HER2/ERBB2 (Tyr1248, catalog number AF3069, 1:1000 dilution, Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-EGFR (catalog number AF6043, 1:1000 dilution, Affinity Biosciences), and anti-p-HER1/EGFR (Tyr1173, catalog number AF3048, 1:1000 dilution, Affinity Biosciences) antibodies were used. After washing thrice with Tris-buffered saline and Tween, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit antibodies; Proteintech). The bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime).

Flow cytometry

TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT cells were suspended in a flow buffer which was phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum and were fixed with paraformaldehyde for 10 min; the membrane was then broken with a membrane-breaking solution for 20 min. After a subsequent wash in the flow PBS, cells were centrifuged at 3000 × g and again suspended in PBS and incubated with anti-EGFR (CB2 0AX, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-HER2 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) in the dark for 2 h at 4 °C, with a subsequent wash in the flow buffer, centrifuged at 3000 g and again suspended in PBS. The cells were stained with the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluro 405 anti-rabbit IgG (ab175651, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and Alexa Fluor 594 anti-mouse (ab150108, Abcam) in the dark for 30 min at 4 °C. After staining, the cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (BD CantoII, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cell viability assessment

Cell viability was determined using Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8; Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, to determine the IC50 values of different treatments. First, the different groups of BT474 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well as six replicates in 0.2 mL of the culture medium; medium containing no cells was used as control. After attachment, the cells were incubated with different concentrations of lapatinib (1.5–25 µM) and palbociclib (1–30 µM) for 48 h. CCK8 reagent was added; after 2 h, the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and the IC50 of the drug was calculated based on the OD value. Cell cytotoxicity was calculated according to the following formula: inhibition ratio (%) = (OD (drug − OD (blank))/(OD (drug control) − OD (blank)) × 100%. Finally, using the same method as above, lapatinib (1–30 µM) was added at a 20% inhibitory concentration (IC20) with palbociclib. The growth rate was evaluated in the same manner for 48 h by measuring absorbance at 450 nm. The CI values were calculated using CompuSyn (ComboSyn Inc., New York, NY, USA)12. The fraction affected was determined according to the following formula: 100 – growth inhibition/100. The CI value was used to determine whether the effects of the two drugs were synergistic (<1), additive (1–1.2), or antagonistic (>1.2) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommended symbol table for describing synergy or antagonism in drug combination studies analyzed by the combination index (CI) method.

| Range of CI | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| <0.1 | +++++ | Very strong synergism |

| 0.1–0.3 | ++++ | Strong synergism |

| 0.3–0.7 | +++ | Synergism |

| 0.7–0.85 | ++ | Moderate synergism |

| 0.85–0.90 | + | Slight synergism |

| 0.90–1.10 | ± | Nearly additive |

| 1.10–1.20 | – | Slight antagonism |

| 1.20–1.45 | – – | Moderate antagonism |

| 1.45–3.3 | – – – | Antagonism |

| 3.3–10 | – – – – | Strong antagonism |

| >10 | – – – – – | Very strong antagonism |

Cell cycle analysis

The three groups of cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded in a 6-well plate (105 cells/well) and were starved for 24 h before processing. The different groups of BT474 cells were treated with lapatinib, palbociclib, or a combination of the two drugs for 48 h. The cells were washed with cold PBS and treated with 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight, and the cell solution was adjusted to obtain 5 × 105 cells/mL. The cells were then stained with propidium iodide (50 µg/mL, MultiSciences, Hangzhou, China) in the presence of RNase A (100 µg/mL). A flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter flow cytometer, Brea, CA, USA) was used to evaluate cell cycle distribution. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Colony formation assay

The three groups of cells (TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT) were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells/well and treated with different concentrations of lapatinib, palbociclib, or a combination of the two drugs for 2 days. The cells were cultured for an additional 2 weeks. Colonies (>50 cells) were stained with crystal violet, and each well was photographed before the colonies were counted under an inverted microscope.

Xenograft studies

This study was approved by the Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Committee of Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China (20190708-08). Female nude mice (BALB/c: female thymus free, age: 4–6 weeks, weight: approximately 30 grams) were purchased from the Shanghai Slack laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and raised in a pathogen-free animal facility at the Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The investigators showed no bias in the processing of animal experiments. Experiments complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research. The sample size of mice was determined using the degree of freedom (E) of variance analysis, and E was calculated as follows: total number of mice in each group − total number of groups. The range of E was 10–20. A total of 60 mice were used. The laboratory technician randomly divided the mice into TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT groups (20 mice/group) using the simple randomization method with a random number table. Three groups of TSC2-NC, TSC2-WT, and TSC2-MT xenografts were suspended in 1:4 matrix gel at 107 cells/100 μL and injected subcutaneously into the right side of the dorsal surface of each mouse. As the tumor formation rates were 100% in all three groups, no mice were excluded. When the tumor volume was close to 100 mm3, all mice in each group were randomly divided into control, lapatinib, palbociclib, and combination of two drugs groups (5 mice/group/cage) using the same randomization method. Group 1, the control group, received vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose, 0.4% Tween-80); group 2 received lapatinib (80 mg/kg/d); group 3 received palbociclib (100 mg/kg/d); and group 4 received lapatinib (80 mg/kg/d) and palbociclib (100 mg/kg/d). As all drugs are water-soluble and absorbed through the intestine, they were administered once daily via oral gavage at the same time for 21 consecutive days. All mice were maintained under the same controlled feeding and housing conditions. Tumors were measured twice/week using a caliper in the same order every time, and their volumes (mm3) were calculated using the formula (width)2 × length/2. After 21 days, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation without anesthesia, and tumors were harvested after the last treatment for tumor weight measurement. Tumor tissues were preserved in liquid nitrogen, or formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) for analysis of associated biomarkers (HER2, p-HER2, p-TSC2, mTOR, and p-P70S6K).

Immunohistochemistry

We performed IHC to evaluate the clinical and animal tumor samples. Paraffin sections with a thickness of 5 µm were deparaffinized with xylene and absolute ethanol. Antigen recovery was performed after washing with distilled water. The paraffin sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature (22 °C) for half an hour and blocked with bovine serum albumin for the same duration followed by overnight probing with the primary antibody. anti-HER2 (catalog number AF7681, 1:100 dilution, Affinity Biosciences), rabbit anti-p-HER2/ERBB2 (Tyr1248, catalog number AF3069, 1:100 dilution, Affinity Biosciences). anti-p-TSC2 (Thr1462, catalog number AF3334, 1:50 dilution, Affinity Biosciences). anti-p-mTOR (Ser2448, catalog number 5536, 1:100 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-p-P70S6K (Thr389, catalog number AF3228, 1:100 dilution, Affinity Biosciences). Finally, the sections were washed thrice with PBS. The sample was then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody from the immunohistochemistry kit (Dako, catalog number K5007, Copenhagen, Denmark). After incubating for 1 h and washing thrice, diaminobenzidine solution was added. The sections were then stained and counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analyses

Continuous quantitative data were compared using the independent-sample Student’s t-test (between two groups) or one-way ANOVA (more than two groups). Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), and data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. For all data, P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient who participated in the investigations. This study was funded by grants from the Key Research-Development Program of Zhejiang Province, China (grant numbers: 2019C04001 and 2020C04012) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (grant number: LY21H160005).

Author contributions

W.C. and X.W. conceived the study. Z.Y. and J.F. carried out the experiments. Y.H., W.Y., and L.L. collected clinical samples and information. Z.Y., J.J., J.F., W.C., and X.W. contributed to the interpretation of the results. W.C. and Z.Y. led the writing of this manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped to form research, analysis and manuscript.

Data availability

The raw data of whole-exome sequencing from the breast cancer patient with TSC2 c.4349 C > G variant can be accessed here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA924228. Other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). The complete version of the data is accessed from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15 or GraphPad Prism v7.0. Open-source software was employed for bioinformatic analyses in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Jia Wang, Email: wxiaojia0803@163.com.

Wen-Ming Cao, Email: caowm@zjcc.org.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41523-023-00542-1.

References

- 1.Chen W, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan L, et al. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e279–e289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runowicz CD, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:43–73. doi: 10.3322/caac.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, et al. A new anti-HER2 antibody that enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of trastuzumab and pertuzumab with a distinct mechanism of action. Mol. Immunol. 2020;119:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez-Martin A, et al. Lapatinib, a dual HER1/HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, augments basal cleavage of HER2 extracellular domain (ECD) to inhibit HER2-driven cancer cell growth. J. Cell Physiol. 2011;226:52–57. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, et al. HER2-L755S mutation induces hyperactive MAPK and PI3K-mTOR signaling, leading to resistance to HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Cell Cycle. 2019;18:1513–1522. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2019.1624113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porta C, et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:64. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracho-Valdés I, et al. mTORC1- and mTORC2-interacting proteins keep their multifunctional partners focused. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:896–914. doi: 10.1002/iub.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uysal SP, Şahin M. Tuberous sclerosis: A review of the past, present, and future. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020;50:1665–1676. doi: 10.3906/sag-2002-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansmann P, et al. Structure of the TSC2 GAP domain: Mechanistic insight into catalysis and pathogenic mutations. Structure. 2020;28:933–942.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, et al. Structural insights into TSC complex assembly and GAP activity on Rheb. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:339. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20522-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero-Pozuelo J, et al. Cdk4 and Cdk6 couple the cell-cycle machinery to cell growth via mTORC1. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107504. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zacharek SJ, et al. Negative regulation of TSC1-TSC2 by mammalian D-type cyclins. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Hassouni B, et al. EORTC PAMM Group. To combine or not combine: Drug interactions and tools for their analysis. Reflections from the EORTC-PAMM Course on Preclinical and Early-phase Clinical Pharmacology. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:3303–3309. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacKeigan JP, Krueger DA. Differentiating the mTOR inhibitors everolimus and sirolimus in the treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neuro. Oncol. 2015;17:1550–1559. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alayev A, et al. Effects of combining rapamycin and resveratrol on apoptosis and growth of TSC2-deficient xenograft tumors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015;53:637–646. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0022OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K, et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib enhances the effect of pyrotinib in HER92-positive breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;447:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel S, et al. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in HER2-positive breast cancers with CDK4/6 inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Topacio BR, et al. Cyclin D-Cdk4,6 drives cell-cycle progression via the retinoblastoma protein’s C-terminal helix. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:758–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin Z, et al. Tsc1 deficiency impairs mammary development in mice by suppression of AKT, nuclear ERα, and cell-cycle-driving proteins. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19587. doi: 10.1038/srep19587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor-SHR6390 exerts potent antitumor activity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting phosphorylated Rb and inducing G1 cell cycle arrest. J. Transl. Med. 2017;15:127. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickl M, et al. Comparison of 3D and 2D tumor models reveals enhanced HER2 activation in 3D associated with an increased response to trastuzumab. Oncogene. 2009;28:461–468. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez CE, et al. Breast cancer stem cells are involved in Trastuzumab resistance through the HER2 modulation in 3D culture. J. Cell Biochem. 2018;119:1381–1391. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatara T, et al. 3D Culture Represents Apoptosis Induced by Trastuzumab Better than 2D Monolayer Culture. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2831–2839. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data of whole-exome sequencing from the breast cancer patient with TSC2 c.4349 C > G variant can be accessed here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA924228. Other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). The complete version of the data is accessed from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15 or GraphPad Prism v7.0. Open-source software was employed for bioinformatic analyses in this study.