Abstract

Context

Obesity and mental health issues increasingly affect children and adolescents, but whether obesity is a risk factor for mental health issues is unclear.

Objective

To systematically review the association between obesity and mental health issues (ie, anxiety and/or depression) among Mexican children and adolescents.

Data sourcing, extraction, and synthesis

A literature search of 13 databases and 1 search engine was conducted. Population, exposure, comparison, outcomes, and study design data were extracted, analyzed, and narratively synthesized. The JBI critical appraisal tool was used to evaluate evidence quality.

Results

A total of 16 studies with 12 103 participants between 8 and 18 years old were included. Four studies focused on anxiety outcomes, 10 on depression, and 2 on both (ie, anxiety and depression). Evidence is unclear about the association of obesity with anxiety. However, most evidence shows that Mexican children and adolescents with overweight or obesity are more likely to have depression or report a higher number of depressive symptoms than normal-weight participants. Such likelihood is greater for females.

Conclusion

Health promotion interventions to treat or prevent obesity could also consider mental health outcomes.

Systematic Review Registration

PROSPERO registration no. CRD42019154132

Keywords: adolescents, anxiety, children, depression, Mexico, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Mental health problems and emotional disorders are increasingly prevalent, disabling, and recurrent among young people.1 The prevalence of anxiety has been reported to be higher for children and depression higher for adolescents. However, as individuals grow, it is more common to find both conditions (ie, anxiety and depression).2 Untreated mental health issues among children and adolescents are associated with poor school performance, social functioning, and substance misuse.3 Additionally, recurring anxiety or depression can be maintained until adulthood, increasing suicide risk, which is the second leading cause of preventable death among young people.4

Like mental health issues, obesity is also a condition that increasingly affects children and adolescents, which can also be prolonged until adulthood and leads to various clinical conditions.5 Obesity and mental health disorders are closely related, and a bidirectional association between conditions has been suggested.6,7 Likewise, these conditions share a common etiology (eg, sedentary behaviors, altered sleep patterns, altered dietary behaviors or appetite, negative self-image) and environmental, physiological, and/or genetic factors.7,8 Although obesity is frequently accompanied by mental disorders, whether obesity is a risk factor for mental health issues remains unclear.4,6,8

The prevalence of obesity and mental health issues has been increasing among Mexican children and adolescents in the past decades.9,10 It has been estimated that in Mexico, approximately 8% of infants (aged 0–4 years), 35% of children (aged 5–11 years), and almost 40% of adolescents (aged 12–19 years) have overweight or obesity.9 Additionally, nearly 40% of Mexican adolescents (aged 12–17 years) have 1 or more mental health disorders, with anxiety disorders most frequently reported.11 There is increased recognition of a potential relationship between obesity and mental health disorders among the pediatric population.12,13 Several reviews evaluating the association between obesity and mental health disorders have been conducted.4,14–16 Nevertheless, most include only English publications, excluding valuable information from non-English–speaking low- or middle-income countries such as Mexico. Considering that both conditions (ie, obesity and mental health disorders) are highly prevalent among Mexican childhood or adolescents and the short- and long-term impact on an individual’s well-being and quality of life,13 it is essential to acknowledge the possible associations between these conditions within the Mexican context. Furthermore, most of the current interventions to treat17 or prevent18 obesity among Mexican children or adolescents are focused merely on changing weight outcomes, overlooking the potential effect these can have on other health outcomes, such as mental health.

The “Childhood and adolescent Obesity in MexicO: evidence, challenges and opportunities” (COMO) Project17–21 intends to synthesize and use data to comprehend the extent, nature, effects, and costs of childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico. This article is part of the COMO project, and in it, we aimed to systematically review the association between obesity and mental health issues (ie, anxiety and/or depression) among Mexican children and adolescents.

METHODS

The project’s systematic review is registered in The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO Registration number CRD42019154132).22 This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.23

Literature search

The databases searched included AGRICOLA, CAB Abstracts, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, ERIC, LILACS, MEDLINE, Global Health Library PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and SciELO Citation Index. Also, relevant material was searched in Google Scholar. A sensitive search strategy included index terms, free-text words, abbreviations, and synonyms to combine the key concepts for this review. Terms such as “overweight,” “obesity,” “child,” “adolescent,” “depression,” “depressive disorders,” “depressive symptoms,” “anxiety,” “anxiety disorder,” and “anxiety symptoms” were included in the strategy (see Supplemental Material 1 in the Supporting Information online). Whenever possible, searches were also done in Spanish to capture relevant references. In addition, the COMO project database was revised. This database comprises >950 scientific references relevant to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico.19 Full reports of studies and conference abstracts were included if these met the inclusion criteria. Also, reference lists of included studies were scrutinized for additional publications. English-, Spanish-, or Portuguese-language publications were considered. Reports from 1995 onward were included in this review. The original searches were done in January 2020 and updated in February 2022.

The research question and inclusion/exclusion criteria were established following the Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Design (PECOS) framework (Table 1). These are described in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

PECOS criteria for inclusion of studies

| Population | Children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years of any ethnicity or sex living in Mexico were included. Participants with diagnosed eating disorders, severe conditions, or pregnant adolescents were excluded. |

| Exposure | Studies reporting overweight or obesity of participants' body mass index or another anthropometric measurement related to adiposity were considered. |

| Comparison | Any or none |

| Outcomes | Studies reporting any measurement of anxiety and/or depression and/or depressive symptoms were considered. |

| Study design | Observational (cross-sectional or longitudinal) studies |

Population.

Studies including participants from ages 0 to 18 years (mean age at the start of the study) of any ethnicity or sex living in Mexico were considered in this review. Studies that analyzed participants with diagnosed eating disorders, severe conditions (eg, HIV, cancer, Down syndrome), or pregnant adolescents were excluded.

Intervention/exposure.

Studies reporting body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2) or another anthropometric measurement related to adiposity, overweight, or obesity were considered in this review. For those studies reporting BMI, data had to be categorized with national or international references (eg, World Health Organization, International Obesity Task Force, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to be eligible.

Outcomes.

Anxiety and/or depression outcomes were considered in this review. Any tool for measuring anxiety and/or depression were considered (eg, single- or multiple-item questions in a questionnaire or rating scales, standardized psychiatric interview, physician-reported diagnosis).

Study design.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are relevant when studying the association between childhood obesity and anxiety or depression.6 For this reason, human observational (cross-sectional and longitudinal) studies were considered in this review.

Data selection and extraction.

After conducting the searches, titles and abstracts were examined by 3 reviewers (M.A.-M., M.G.-B., and L.L.-C.). The abstracts identified as potentially relevant for full-text review were assessed by 2 reviewers (N.L.G.-F. and M.A.-M.), and they independently extracted data from the included studies and agreed to the information retrieved. In case of any disagreement, a third author was contacted to reach an agreement (Y.Y.G.-G.).

A data extraction form was designed and constructed following the PECOS framework to obtain relevant information from the included studies. The form included population characteristics (ie, population characteristics, age, sex, socioeconomic or demographic characteristics); study design and setting characteristics (eg, city, Mexican state, recruitment location); exposure (ie, BMI, BMI categorization, and references); outcomes: anxiety or depression outcomes and the scale used to measure such outcomes.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The JBI (formerly the Joanna Briggs Institute) critical appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies was used to assess the quality of the included studies.24 The tool evaluates 8 key methodological items (eg, inclusion and exclusion criteria; validity and reliability of measurement used; confounding factors and strategies to deal with them). “High quality” studies were those that provided sufficient detail for all items evaluated. “Unclear quality” studies had 1 or more “unclear” appreciation in the items. “Low quality” studies failed to report 1 or more items. Two reviewers (N.L.G.-F. and M.A.-M.) performed this evaluation independently and agreed on the results. A third reviewer was consulted (Y.Y.G.-G.) if there was any disagreement.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was conducted because of the heterogeneity of tools used to measure mental health outcomes across the studies and the lack of similar effect measurements. Textual descriptions of studies and reported statistical analysis were recorded and tabulated. Overall, reported outcomes presented in the studies were reported narratively. The critical appraisal of the quality of each study was also considered in the synthesis.

RESULTS

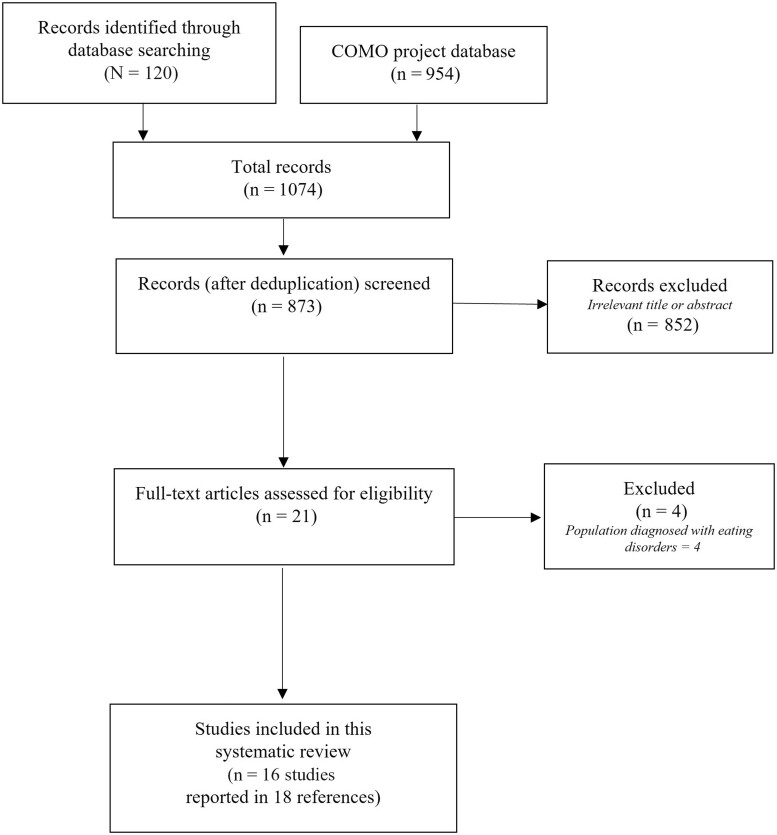

Our searches identified 1074 references, and after screening titles and abstracts of these references,20 were retrieved for full-text review. From these, 16 studies (reported in 18 references),25–42 were included in this review (Figure 1). The included studies were implemented in 12 of 32 states in Mexico (Figure 2), and 1 included a national representative sample.42 In these studies, participants were interviewed at a household level, whereas 9 studies recruited participants in a school setting and 6 in a clinical setting.25,26,30,33,34 All the included studies had a cross-sectional design.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Abbreviation: COMO, Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in Mexico: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities.

Figure 2.

Map of the evidence.

The number of participants ranged from 60 to 5670, totaling 12 103 participants across the 16 studies. The age of the population ranged from 8 to 18 years. All studies included male and female participants, except 1, which only included female participants.28 Most studies included children with different BMI categories (overall, 43.8% average prevalence of obesity), but 2 studies included only participants with obesity (Table 225–42).31,36

Table 2.

General characteristics of included studies

| Reference and study design | Settinga | Participants: total (% female); age (mean [SD], y | Prevalence of OW or OB; reference used | Outcome measurement | Overall result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

406 (50.7); age: 10.4 (1.2) | OW: 24.6, OB: 18.7, OW+OB: 43.3; CDC | Anxiety measured through a validated test toward anxiety in the presence of food (validated in Latin population) | Significative association between nutritional status with anxiety (P = 0.01). Also, there was a significant association between anxiety with socioeconomic level (P = 0.01), remaining unclear in this relationship. |

|

|

74 (52.7); age: 13 (NR) | OW: NA, OB: 100, OW+OB: NA; WHO | Depression measured with Birleson Scale | 40.5% of the sample had depression. The level of depression increased when the BMI was higher, but this trend was not significant (P = 0.393) |

|

|

102 (52.94); age: 18 (1.5) | OW: 15.7, OB: 11.8, OW+OB: 27.5; WHO | Depression measured with CESD-10 (validated) | No significant association between BMI and depression (P > 0.05) was found. However, when related to sex, there was a marginally significant association between BMI and depression among female participants (P < 0.05). There was also a significant negative association between family support and depression (P < 0.05) that was more significantly pronounced among female participants (P < 0.05). |

|

|

231 (100%); age: 11.3 (0.72) | OW: 24.7, OB: 16.9, OW+OB: 41.6; WHO | Depression measured with CESD (validated) | No significant differences among the level of depression and BMI groups (P = 0.68). However, girls with overweight and obesity and with body dissatisfaction had lower self-esteem levels (P < 0.01) compared with other BMI groups. Overall, participants with obesity and overweight showed a greater body dissatisfaction level than normal-weight participants (P < 0.01, P = 0.04, respectively). |

|

|

585 (49.23%); age: 9 (1.32) | OW: 29.7, OB: 26.0, OW+OB: 55.7; WHO | Anxiety measured with CMAS-R (validated) | No significant association between anxiety and BMI status (P > 0.05). However, there was a positive and significant association between waist size and anxiety (P = 0.015). |

|

|

164 (49); age: 14.7 (2.3) | OW: 38.4, OB: 40.2, OW+OB: 78.5; WHO | Depressive symptoms were assessed was with Children's Depression Inventory: Short Version | Overall, participants with obesity were significantly (P < 0.05) more likely to have depressive symptoms, and as BMI increased, more depressive symptoms were reported (P = 0.04). The adjusted odds for those participants with overweight and obesity were 1.9 (95%CI 0.6–6.4) and 2.7 (95%CI 0.9–9.2) to be more likely to have depression; however, these were not significant. Nevertheless, those participants with a greater waist circumference (>90th percentile) were significantly more likely to have depression OR 4.4 (95%CI 1.4–19.5). |

|

|

332 (46.1); age: NR | OW: NR, OB: NR, OW+OB: 100.0; NR |

|

|

|

|

165 (55.2); age: NR | OW: 38.4, OB: 40.2, OW+OB: 78.5; CDC | Depression measured with CDI (validated) | 20.6% of the participants had depression, and a significantly higher proportion of these had obesity (64.7; P = 0.001); 35.3% had average weight. Also, the prevalence of depression was significantly (P < 0.001) higher among females (70.5%) than males (26.5%). Those participants with obesity were more likely to report depression (OR,2.4; 95%CI, 1.1–5.3; P = 0.025), and that likelihood was higher among females (r = 2.5; 95%CI, 1.1–5.6; P = 0.021) |

|

|

238 (50%); age: 10.8 (NR) | OW: NR, OB: NR, OW+OB: 37.8; WHO | Depression measured with CDI (validated) | 5.9% of the sample had depression. The prevalence was higher among females (7.5%) than males (4.2%). Having overweight or obesity was associated with a higher likelihood of depression (OR, 4.5; 95%CI, 1.3-14.8; P > 0.008) |

|

|

101 (60.4); age: 9.89 (NR) | OW: 21.8, OB: 23.8, OW+OB: 45.5; CDC | Depression measured with CDI (validated) | 28.7% of the sample had depression; of these, 65.5% of children had overweight or obesity (P value not reported). |

|

|

616 (50.33); age: 14 (NR) | OW: NR, OB: NR, OW+OB: 37.8; WHO | Depression measured with Zung Scale (validated) | BMI, self perception of body image, and waist size were higher in adolescents with higher depressive symptoms (P < 0.05). Frequency of depressive symptoms was greater in girls but unclearly related to BMI (P value not reported). There was a positive association between BMI and self perception of body image (P = 0.0001). |

|

|

60 (65%); age: NR. School children | OW: NA, OB : 100, OW+OB: NA; WHO | Depression measured with Beck's tool (validated) | A nonsignificant relationship between depression and obesity was found (P = 0.572). However, female participants reported depression more frequently than males, but a relationship to BMI was unclear (P value not reported). |

|

849 (53.7); age: 13.17 (NR) | OW: 29.7, OB: 28.6, OW+OB: 58.3; WHO |

|

|

|

|

142 (50.7); age: NR School children | OW: 27.5, OB: 13.4, OW+OB: 40.9; WHO | Anxiety and depression measured with HAD (validated) | No significant association was found between anxiety and nutritional status (P > 0.05), as well as between depression and nutritional status (P > 0.05). | |

|

|

2368 (49.75); age: 12.1 (0.5) | OW: NR, OB: NR, OW+OB: NR; WHO | Anxiety and measured with HAD (validated) | No significant association was found between anxiety and nutritional status (P > 0.05). Girls had higher anxiety levels (P < 0.01) than boys. However, it is unclear if there was a relation with their BMI. Children attending school in the evening had higher anxiety than in those attending during the morning (P < 0.05). |

|

|

5670 adolescents (49.8); age: 15.3 (NR) | OW: 23.8, OB: 14.7, OW+OB: 38.5; WHO | Depression symptoms were measured with CESD-7 (validated) | 3.5% of the sample had depression. The likelihood of depression increased with obesity (OR, 1.46; P = 0.035) and was reported to be greater in females (OR, 2.07; P < 0.001) and to increase with age (OR, 1.21; P < 0.001). In addition, the probability of having depression was reported to be greater than the medium wellness index (based on household conditions) (OR, 1.59; P = 0.006), although it seemed to be greater in the high wellness index, but not significantly so (OR, 1.39; P = 0.071) (both compared with the lower wellness index). |

City or municipality, state in Mexico.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CDI, Depression Inventory for Children; CDS, Depression Scale for Children; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-7 is the short version); CMAS-R, Child Manifest Anxiety Scale-Revised; ENSANUT, Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey; HAD, Hamilton Anxiety Questionnaire; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; OB, obesity; OW, overweight; WHO, World Health Organization.

Of all the included studies, 325,29,41 focused on anxiety outcomes, 1026–28,30,32–36,42 focused on depression outcomes, and the rest31,37–40 focused on both (ie, anxiety and depression analysis).

Of those studies measuring anxiety, 3 used the Child Manifest Anxiety Scale-Revised,29,31,37 2 used the Hamilton Anxiety Questionnaire,40,41 and 1 used a “test towards anxiety in the presence of food.”25 All the tools were reported as validated in the Mexican population, Latin infant population, or adolescents in general. Although some studies used the same measurement tools, these were used (or results were presented) heterogeneously (Table 2). Overall, 1 study25 found a significant positive association between nutritional status and anxiety levels (P = 0.01). One other37 reported that participants with overweight or obesity had more likelihood (odds ratio [OR], 1.8) of presenting high anxiety levels, but no statistical test was presented to support this result. The rest of the studies did not find a significant association between anxiety and nutritional status (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Some studies analyzed the presence of anxiety, along with other potential confounding factors. For instance, 2 studies37,39 analyzed this association by sex. The researchers found that female participants had a higher likelihood (OR, 1.4; P < 0.001) of manifesting anxiety or having higher levels of anxiety (P < 0.01) compared with male participants.37,41 However, it was unclear if the BMI of participants in both studies affected the association. One study25 found a significant association (P < 0.05) between anxiety and socioeconomic level. Also, the associations between anxiety and obesity varied according to the anthropometric variable used. For instance, 1 study29 found an association between greater waist circumference and anxiety (P = 0.015), but not BMI. Additionally, 1 study31 found a significant association (P < 0.05) between higher anxiety levels among those children with overweight and obesity who reported eating less fruit.

Of those studies that measured depression, the measurement tools also varied across studies. For instance, 3 studies27,28,42 used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in its original or shorter (10 or 7 items, respectively) version; 231,38 used the Depression Scale for Children, 134 used the Depression Inventory for Children, 135 used the Zung Scale, 136 used Beck's depression inventory, and 139 used the Depression Hamilton Anxiety Questionnaire Scale. All these tools were reported as validated among children and adolescents.

In 6 studies, the prevalence of depression was higher among children or adolescents with greater BMIs.30,32–35,38,42 It was reported that children with overweight or obesity were up to 4.5 times (OR, 4.5; 95%CI, 1.3–14.8; P > 0.008) more likely to report depression.33 Two studies reported that depression increased when BMI was higher, but such trends were not statistically significant.26 Females reported significantly higher rates of depression compared with males across different studies.27,32,33,35,36,38,42 One study27 found a significant association between BMI and depression only in female participants (P < 0.05) and also reported a significant negative association between family support and depression (P < 0.05). Another study31 found an association between higher levels of depression and greater amounts of fat consumption in children with overweight and obesity (P < 0.05). One study30 found no significant association between obesity (estimated through the BMI of participants) and depression. Nonetheless, those participants with a larger waist circumference (>90th percentile) were significantly more likely to have depression (OR, 4.4; 95%CI, 1.4–19.5).

Quality of the included studies

Most of the studies were of low (n = 10 of 16) or unclear (n = 1 of 16) quality, and only 430,32,37,42 had a higher quality. Overall, some studies (n = 5 of 16)25,31,35,36 did not clearly define the criteria to include participants in the study, and in 1 study,39 the inclusion criteria were unclear. All studies but 411 described the study participants and setting in detail.41 Most of the studies used reliable and valid tools to measure the exposure (ie, nutritional status) or the outcomes (ie, anxiety or depression). However, the identification and strategies to deal with confounding factors in the analysis were unclear in 5 studies.26,28,29,34,39 Finally, the statistical analysis was unclear in 3 studies26,34,39 (Table 325–42).

Table 3.

The JBI critical appraisal tool: quality appreciation

| Reference | Criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined | Study participants and the setting described in detail | Exposure measured in a valid and reliable way | Standard criteria used for measurement of the condition | Confounding factors identified | Strategies to deal with confounding factors stated | Outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way | Appropriate statistical analysis used | Overall critical appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Álvarez-Villaseñor 202025 | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ✓ | Low |

| Angulo-Valenzuela 201626 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ? | Low |

| Caetano-Anolles 201327 | × | ✓ | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Contreras-Valdez 201528 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Escalante-Izeta 201623 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ? | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Flores 201530 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

| Garcia-Falconi 201631 | × | ✓ | ? | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Gonzalez-Toche 201732 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

| Hernández Nava 202033 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear |

| Lopez-Morales 201434 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ? | Low |

| Merino-Zeferino 201835 | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Moreno-Martínez 201836 | × | ✓ | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Pompa-Guajardo 201737 and Pena 201738 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

| Radilla 201339,40 (abstracts) | ? | ✓ | ? | ✓ | ? | × | ? | ? | Low |

| Radilla-Vazquez 201541 | ✓ | × | ? | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Shamah-Levy 202042 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

Key: ✓, yes; ×, no; ?, unclear.

DISCUSSION

Overall, we identified 16 studies (presented in 18 references) analyzing the association between obesity and anxiety and/or depression in Mexican children and adolescents. Of all the included studies, 325,29,41 focused on anxiety outcomes, 1026–28,30,32–36,42 on depression outcomes, and the rest31,37–40 focused on both (ie, anxiety and depression analysis). The minority of the studies (25%) were considered high quality. Although the evidence is unclear on the association of obesity with anxiety, most evidence suggests that Mexican children and adolescents with higher BMIs (or other anthropometric measurements suggesting obesity) are more likely to present depression or higher depressive symptoms than those with a normal weight. Such likelihood is greater for females with higher BMIs than for males. In addition, evidence from Mexico suggests that such an association can be influenced by other sociodemographic factors, socioeconomic status, family support, and lifestyles (eg, dietary).

The associations between obesity and depression have been found in cross-sectional and longitudinal research.43 However, longitudinal studies are essential to quantify the bidirectional relationship between obesity and depression.6,16 Previous results have shown that cross-sectional studies identify associations between childhood obesity and depression or anxiety more frequently than longitudinal studies.6 Unfortunately, no longitudinal studies were identified among Mexican children and adolescents regarding obesity and mental health issues. Hence, the bidirectionality of this association was not evaluated among the Mexican pediatric population. Nonetheless, evidence from high-income countries has suggested a 70% increased risk of obesity among adolescents with depression. Conversely, adolescents with obesity had a 40% greater risk of having depression.16

Several possible mechanisms have been hypothesized to be implicated in the etiology of obesity and depression and their bidirectional association. For instance, a shared genetic or biological mechanism including inflammation,44,45 neuroendocrine mechanisms,46 or dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis has been suggested.47 Lifestyles might also be linked to obesity and depression, especially among young people, whereby changes in appetite and dietary patterns might result in altered weight, sedentary activity, or sleeping.16 Some dietary patterns (eg, overconsumption of savory food, usually high in fat, salt, or sugar) have been associated with depression and are also linked to obesity.48 However, there is also evidence suggesting that depressive symptoms might be associated with a reduced likelihood of eating a healthy diet among Latino populations.49

In Mexico, it has been documented that emotional and behavioral difficulties among children are linked to soda consumption.50 Emotional and behavioral difficulties are also linked to sleep problems in children and adolescents,51 and a poor sleeping quality is also associated with greater amount of soda consumption. This dietary behavior could lead to obesity.50 In this same line, other emotional and behavioral difficulties (eg, binge eating, lower self-esteem, altered self-concept) have also been strongly correlated with BMI among a pediatric population.52,53 Nevertheless, several emotional short- and long-term emotional tolls have also been reported among children and adolescents with obesity (eg, stigmatization, bullying, mood disorders, altered self-esteem and self-image).54

A recent review of the COMO project reported that Mexican children and adolescents with obesity are highly exposed to stigmatization by peers and even family members.21 Such stigmatization might also lead to depression or anxiety,55 affecting their general well-being and other outcomes (eg, school performance),56 although, it has also been described that stigmatization, depressive symptoms, lack of physical appearance, and low self-esteem in adolescents with obesity entailed greater than average weight gain.57 However, it is still unclear whether higher BMIs entail high depression scores because of stigmatization, bullying, lower self-esteem, or other psychological mediators.6

The results of this review suggest that females are more vulnerable to depression and anxiety, especially if their BMIs are higher. Such a result aligns with previous international evidence suggesting that adolescent females with obesity are more likely to develop depression or report a higher number of depressive symptoms than normal-weight adolescents or males.6,14–16,57,58 This is relevant considering that obesity seems to be distinguished as an issue in Mexican culture only in females by children, adolescents, or even family members.21 Overall, there is consistent evidence for a sex effect in bidirectional associations of obesity and depression with a stronger relationship in females than males.6 Body satisfaction has been suggested to be a key factor when considering sex in this association.4 Obesity has been related to body dissatisfaction and decreased self-esteem, which both are considered risk factors for depression.45 Females might be more susceptible to present body dissatisfaction or be more aware of weight-related issues than males. One of the included studies28 found that females with overweight and obesity had significantly greater body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem levels than normal-weight adolescents. The perception of being overweight might also increase psychological distress because of beauty or thinness ideals among females. Evidence from longitudinal studies conducted in high-income countries suggested that the longer a female child or adolescent has obesity or depression, the more likely it is that lifestyle and environmental factors may enhance this association.59,60

Almost none of the current interventions to treat17 or prevent18 obesity among Mexican children and adolescents contemplates mental health outcomes. Romero et al61 implemented a randomized controlled trial to measure the effectiveness of a physical activity program over anthropometric indicators and levels of anxiety and depression in Mexican school-aged children with obesity. The experimental group received 2 weekly 50-minute sessions for 20 consecutive weeks. Overall, the researchers found that the physical exercise program favored the appearance of positive thoughts, with improvements in the participants' emotional well-being, self-perception, and self-concept. However, it did not produce significant weight changes, height, Z-score, level of anxiety, or depressive thoughts.61 Such intervention was evaluated in the short term (<12 mo); hence, longer interventions and evaluations are needed to estimate the effect on anthropometric and mental health outcomes.

The findings in this review need to be interpreted in light of its limitations and strengths. One of the main limitations of this study was the limited number of high-quality studies and the high heterogeneity of the included studies. For example, included studies used various scales and tools to measure anxiety or depression. Also, studies varied in their methods and analysis, thus hindering a solid comparison. Hence, effect measurements made unfeasible a more consistent synthesis or quantitative analysis (ie, meta-analysis). There was also a variation in the obesity diagnosis, influencing the results. Moreover, retrieved evidence came from 12 of 32 states in Mexico and mainly from urban areas. Consequently, the results might not show a nationwide picture and overlook vulnerable populations. Finally, not all the included studies reported thoughtfully sociodemographic or economic characteristics of the participants, which might also affect both depression and obesity.

This work's strengths include an extensive and comprehensive search for evidence, performed in 2 languages, which helped us capture relevant publications. In addition, an extensive search for grey literature was conducted as part of the COMO project.19 However, no related information about mental health (including depression or anxiety) was identified among Mexican children or adolescents.

Current efforts to treat17 or prevent18 obesity in Mexico focus on weight-related outcomes only, overlooking the impact such interventions could have on mental health outcomes. Evidence suggests that a multicomponent and multidisciplinary intervention that includes dietary modifications, physical activity practice, psychological accompaniment (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy), and active parental involvement can effectively tackle obesity among Mexican children.17 Similar approaches are also recommended for treating anxiety62,63 or depression among children and adolescents.63 Likewise, it has been reported that children with obesity are more likely to have mental health issues and complicate obesity treatment or prevention efforts. Hence, obesity and mental health treatment strategies share many common elements. Therefore, various strategies are needed within an intervention to influence both obesity and mental health issues.64

Obesity and mental health problems have health and well-being implications in the short and long term, and they can carry both until adulthood. Although obesity, anxiety, and depression are associated with a child's negative performance and risky lifestyles in the short and long term, these conditions tend to be chronic and recurring.65 Furthermore, health promotion and prevention should address common risk factors and broader risk social determinants shared between noncommunicable diseases.

CONCLUSION

In Mexico, children and adolescents with obesity are more likely to report depression or depressive symptoms. Such likelihood is greater and more evident for females. Unfortunately, the lack of longitudinal data and high-quality studies makes it difficult to establish causation or the bidirectionality of the association between conditions (ie, obesity and mental health issues), and no accurate conclusion can be drawn. Nevertheless, both conditions are highly prevalent among Mexican children and adolescents. Moreover, obesity and mental health issues treatment and prevention strategies share many common elements that can be considered in future health promotion interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Author contributions. M.A.-M. and C.F.M.G. conceptualized and currently lead the COMO project. N.L.G.-F., Y.Y.G.-G., L.L.-C., M.G.-B., C.F.M.-G., and M.A.-M. contributed significantly to the data collection, data interpretation, and analysis; took part in the critical writing and revision of the article; and read and approved the versions submitted to the journal.

Funding. No funding was received to do this work. M.A.-M. is currently funded by the Scottish Government's Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division.

Declaration of interest. Y.Y.G.-G. received funding from Bonafont for a presentation at a congress in 2016 and funding from Abbott to write 2 book chapters in 2020. The other authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Supporting Information

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

Supplemental Material 1. Search strategy for Medline and Embase

Contributor Information

Naara L Godina-Flores, are with the Nutrition Department, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City, Mexico.

Yareni Yunuen Gutierrez-Gómez, are with the Nutrition Department, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City, Mexico.

Marcela García-Botello, is with the Universidad de Monterrey, San Pedro Garza García, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Lizet López-Cruz, is with the Universidad Europea del Atlantico, Parque Científico y Tecnologico de Cantabria, Santander, Spain.

Carlos Francisco Moreno-García, is with the School of Computing, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK.

Magaly Aceves-Martins, is with the The Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK.

References

- 1. Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, et al. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garber J, Brunwasser SM, Zerr AA, et al. Treatment and prevention of depression and anxiety in youth: test of cross-over effects. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:939–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Witt KG, et al. ; Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), third‐wave CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) based interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sutaria S, Devakumar D, Yasuda SS, et al. Is obesity associated with depression in children? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weihrauch-Blüher S, Wiegand S.. Risk factors and implications of childhood obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mühlig Y, Antel J, Föcker M, et al. Are bidirectional associations of obesity and depression already apparent in childhood and adolescence as based on high-quality studies? A systematic review. Obesity Rev. 2016;17:235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reeves GM, Postolache TT, Snitker S.. Childhood obesity and depression: connection between these growing problems in growing children. Int J Child Health Hum Dev. 2008;1:103–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindberg L, Hagman E, Danielsson P, et al. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with obesity: a nationwide study in Sweden. BMC Med. 2020;18:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT) 2018. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI); July 2019. 2018. Available at: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2018/doctos/informes/ensanut_2018_presentacion_resultados.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- 10. Aceves-Martins M, Llauradó E, Tarro L, et al. Obesity-promoting factors in Mexican children and adolescents: challenges and opportunities. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:29625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, et al. Youth mental health in a populous city of the developing world: results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:386–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whitaker BN, Fisher PL, Jambhekar S, et al. Impact of degree of obesity on sleep, quality of life, and depression in youth. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32:e37–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morrison KM, Shin S, Tarnopolsky M, et al. Association of depression & health related quality of life with body composition in children and youth with obesity. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rao W-W, Zong Q-Q, Zhang J-W, et al. Obesity increases the risk of depression in children and adolescents: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;267:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoare E, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. Associations between obesogenic risk factors and depression among adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mannan M, Mamun A, Doi S, et al. Prospective associations between depression and obesity for adolescent males and females- a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aceves-Martins M, López-Cruz L, García-Botello M, et al. Interventions to treat obesity in Mexican children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2022;80:544–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aceves-Martins M, López-Cruz L, García-Botello M, et al. Interventions to prevent obesity in Mexican children and adolescents: systematic review. Prev Sci. 2022;23:563–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aceves-Martins M, Childhood and adolescent Obesity in MexicO: Evidence, challenges and opportunities (COMO) Project. Available at: https://www.comoprojectmx.com/. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- 20. Aceves-Martins M, Godina-Flores NL, Gutierrez-Gómez YY, et al. Obesity and oral health in Mexican children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2022;80:544–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aceves-Martins M, López-Cruz L, García-Botello M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. 2021. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. Accessed February 2, 2020.

- 23. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. ; the PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. 2017. Available at: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017_0.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- 25.Álvarez-Villaseñor AS, Osuna UF, Barrera JS, et al. Anxiety in the presence of food in schoolchildren of Baja California Sur. Nutr Hosp. 2020;37:692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Angulo-Valenzuela RA, Delgado-Quiñones EG, Urióstegui-Espíritu LC, et al. Prevalencia de depresión y dislipidemia en un grupo de adolescentes obesos Mexicanos. Atención Familiar. 2016;23:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caetano-Anolles KT-G, Raffaelli M, Sanchez BA, et al. Depression, family support, and body mass index in Mexican adolescents. Rev Interam Psicol 2013;47:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Contreras-Valdez JA, Hernández-Guzmán L, Freyre M-Á.. Body dissatisfaction, self-esteem, and depression in girls with obesity. Rev Mex de Trastor Aliment. 2016;7:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Escalante-Izeta EI, Haua-Navarro K, Moreno-Landa LI, et al. ; Departamento de Salud, Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de México. Variables nutricias asociadas con la ansiedad y la autopercepción corporal en niñas y niños mexicanos de acuerdo con la presencia de sobrepeso/obesidad. Salud Mental. 2016;39:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Flores YN, Shaibi GQ, Morales LS, et al. Perceived health status and cardiometabolic risk among a sample of youth in Mexico. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1887–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. García-Falconi RA, Sanchez JE, Barjau HG, et al. Ansiedad, depresión, hábitos alimentarios y actividad en niños con sobrepeso y obesidad. Horizonte Sanitario. 2016;15:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 32. González-Toche J, Gómez-García A, Gómez-Alonso C, et al. Association between obesity and childhood depression in school children of a family medicine unit in Morelia. Michoacán Atención Familiar. 2017;24:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nava JPH, Morales BJ, Morales GJ, et al. Depresión y factores asociados en niños y adolescentes de 7 a 14 años de edad. Atención Familiar. 2020;27:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34. López-Morales CP-O, Gonzalez-Heredia R, Brito-Zurita OR, et al. Depresión y estado de nutrición en escolares de Sonora. Rev Méd Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2014;52:S64–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Merino-Zeferino BG-V, Márquez-González H, Guarneros-Soto N, et al. Asociación de síntomas depresivos por tamizaje con el estado nutricional y autopercepción de la imagen corporal en un grupo de adolescentes del estado de México. Rev Mex Endocrinol Metabol Nutr. 2018;5:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moreno Martínez MA, Martínez Aguilar MD, Ávila Alpirez H, et al. Relación entre obesidad y depresión en adolescentes. Cult de los Cuidados 2018;22:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pompa Guajardo EG, Meza Peña C.. Ansiedad, estrés y obesidad en una muestra de adolescentes de México. Univ Psychol. 2017;16:1. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peña CM, Guajardo EGP.. An approach to the study of obesity and depression in a sample of mexican adolescents in northern Mexico Cecilia Meza Peña. Cienc Ergo Sum. 2018;25:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Radilla C, Vega S, Gutierrez R. et al. Relation between the depression and the nutritious condition in adolescents of middle schools in Mexico City: Ann Nutr Metabol 2013;63:674–674. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radilla CV, Gutierrez R, Radilla M, et al. Association of the anxiety with the nutritious condition in adolescents, ages 11 to 13 years in Mexico City: PO283. Ann Nutr Metabol 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vázquez CCR, Vega S, Tolentino RG, et al. Prevalencia de conductas alimentarias de Riesgo y su asociación con ansiedad y estado nutricio en adolescentes de escuelas secundarias técnicas del Distrito Federal, México . Revista Española de Nutrición Comunitaria= Spanish Journal of Community Nutrition 2015;21:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shamah-Levy T, Cuevas-Nasu L, Humarán IM-G, et al. Prevalencia y predisposición a la obesidad en una muestra nacional de niños y adolescentes en México. Salud Publica Mex. 2020;62:725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vittengl JR. Mediation of the bidirectional relations between obesity and depression among women. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kivimäki M, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, et al. Long-term inflammation increases risk of common mental disorder: a cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:149–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luppino FS, De Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Su S-C, Sun M-T, Wen M-J, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, adiponectin, and proinflammatory markers in various subtypes of depression in young men. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;42:211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bornstein SR, Schuppenies A, Wong ML, et al. Approaching the shared biology of obesity and depression: the stress axis as the locus of gene–environment interactions. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O'Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:175–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pagoto SL, Ma Y, Bodenlos JS, et al. Association of depressive symptoms and lifestyle behaviors among Latinos at risk of type 2 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1246–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang Z, Jansen EC, Miller AL, et al. Childhood emotional and behavioral characteristics are associated with soda intake: a prospective study in Mexico City. Pediatr Obes. 2020;15:e12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sadeh A, Tikotzky L, Kahn M.. Sleep in infancy and childhood: implications for emotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence and beyond. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bosch J, Stradmeijer M, Seidell J.. Psychosocial characteristics of obese children/youngsters and their families: implications for preventive and curative interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pasold TL, McCracken A, Ward-Begnoche WL.. Binge eating in obese adolescents: emotional and behavioral characteristics and impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;19:299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cornette RE. Chapter 24 - The Emotional Impact of Obesity on Children. In: Bagchi D, ed. Global Perspectives on Childhood Obesity. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2011:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sweeting H, Wright C, Minnis H.. Psychosocial correlates of adolescent obesity, ‘slimming down’ and ‘becoming obese’. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:409.e9–409.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Levasseur P, Ortiz-Hernandez L.. Comment l'obésité infantile affecte-t-elle la réussite scolaire? Contributions d'une analyse qualitative mise en place à Mexico. [How does childhood obesity affect school achievement? Contributions from a qualitative analysis implemented in Mexico City]. Autrepart.2017;83:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Korczak DJ, Lipman E, Morrison K, et al. Are children and adolescents with psychiatric illness at risk for increased future body weight? A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Quek Y-H, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, et al. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18:742–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Anderson SE, Murray DM, Johnson CC, et al. Obesity and depressed mood associations differ by race/ethnicity in adolescent girls. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, et al. The association between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Romero-Pérez EM, González-Bernal JJ, Soto-Cámara R, et al. Influence of a physical exercise program in the anxiety and depression in children with obesity. IJERPH. 2020;17:4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Öst L-G, Ollendick TH.. Brief, intensive and concentrated cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2017;97:134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dale LP, Vanderloo L, Moore S, et al. Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: an umbrella systematic review. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019;16:66–79. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Small L, Aplasca A.. Child obesity and mental health: a complex interaction. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, et al. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.