Abstract

This study evaluates sales revenue earned in the first 5 years for newly marketed brand-name drugs with and without an initial orphan drug designation.

In 1983, the Orphan Drug Act was enacted to provide incentives for pharmaceutical companies to invest in developing prescription drugs targeting rare diseases, later defined as those affecting fewer than 200 000 US individuals. Congress justified providing extra market exclusivity and tax credits for orphan-designated drugs because small patient populations may produce insufficient sales to attract pharmaceutical investment.

In the last 4 decades, the number of orphan-designated drugs has increased, including many high-earning products.1,2 Consequently, the continued need for the statutory incentives has been debated. We evaluated sales revenue earned in the first 5 years for drugs with and without an initial orphan designation.

Methods

We identified newly marketed brand-name drugs using SSR Health, which contains data on more than 1200 brand-name drugs made by public companies. We included drugs first marketed from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2016, with 5 years of follow-up through December 31, 2021.3 Based on the US Food and Drug Administration’s Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals database, we categorized whether each drug’s initial approval was exclusively for an orphan-designated condition. Drugs initially approved for an orphan-designated indication and subsequently approved for a nonorphan indication were included as orphan-designated, and drugs that were granted an orphan designation for a subsequent indication were included as nonorphan. In a sensitivity analysis, we stratified orphan-designated drugs into those with 1 vs multiple indications within 5 years (eAppendix in Supplement 1).

We tabulated cumulative US sales net of discounts and rebates during the first 5 years after marketing, using SSR Health data in 2021 US dollars (eAppendix in Supplement 1). We used linear regression to compare log-transformed sales of orphan-designated vs nonorphan drugs, adjusting for year marketed and drug characteristics (new active ingredient or reformulation, biologic or small molecule, traditional or accelerated approval, oncologic or nononcologic indications, and route of administration). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and considered significant with a 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Among 315 drugs, 83 (26%) were initially indicated for orphan-designated conditions (Table). Median 5-year net sales were $719 million (IQR, $298 million to $1.8 billion) for orphan-designated drugs and $812 million (IQR, $228 million to $2.4 billion) for nonorphan drugs (adjusted mean ratio, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.1; P = .09).

Table. Five-Year Net Sales for Newly Marketed Prescription Drugs, 2008-2016.

| Drug characteristics | Drugs, No. (%) | Sales, median (IQR), $, in millionsa | Adjusted mean ratio (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All drugs | 315 | 806 (252-2012) | ||

| Orphan designation for first approved indication | ||||

| No | 232 (74) | 812 (228-2351) | [Reference] | |

| Yes | 83 (26) | 719 (298-1771) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | .09 |

| Novelty | ||||

| Reformulation | 116 (37) | 459 (105-1108) | [Reference] | |

| Novel active ingredient | 199 (63) | 1184 (427-2934) | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) | .001 |

| Ingredient type | ||||

| Biologic | 73 (23) | 1122 (247-2525) | [Reference] | |

| Small molecule | 242 (77) | 733 (265-1908) | 1.4 (0.7-2.9) | .40 |

| Approval pathway | ||||

| Traditional approval | 283 (90) | 723 (216-1939) | [Reference] | |

| Accelerated approval | 32 (10) | 1368 (622-3910) | 2.1 (0.8-5.5) | .11 |

| Indication | ||||

| Nononcology | 260 (83) | 706 (210-1911) | [Reference] | |

| Oncology | 55 (17) | 1322 (590-2956) | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | .33 |

| Route of administration | ||||

| Oral | 175 (55) | 905 (343-2591) | [Reference] | |

| Injected | 103 (33) | 1048 (273-2333) | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) | .66 |

| Other | 37 (12) | 241 (48-728) | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | .001 |

| Year first marketed (per year)c | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .63 |

Sales were obtained from SSR Health, which collects these data from public Securities and Exchange Commission filings. We verified missing values by directly searching these filings. Four drugs had no publicly reported net sales, in which case 0 was rounded to $0.1 for the log-transformed model. All sales were converted to 2021 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.

Adjusted mean ratios are derived from the exponentiated estimate from the linear regression model of log-transformed net sales. This can be interpreted as a ratio of mean sales between each group and the reference. For example, mean net sales were 2.3 times higher for drugs containing novel active ingredients compared with reformulated drugs.

Year first marketed was included as a continuous variable in the model. The date of market entry was determined based on the first year a price was listed in SSR Health.

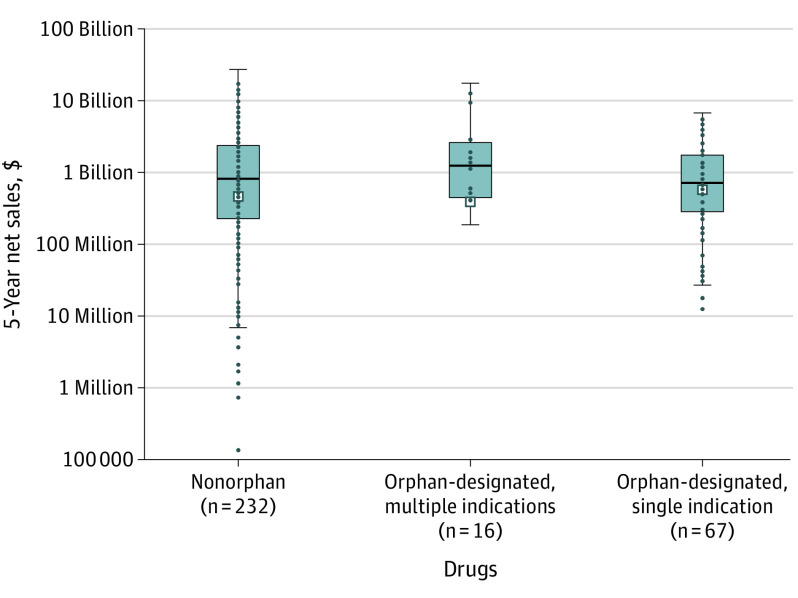

Among orphan-designated drugs, 67 (81%) had a single indication and 16 (19%) had multiple indications within 5 years, including 6 (7%) with a secondary nonorphan indication. Compared with nonorphan drugs, revenue was not significantly different for orphan-designated drugs with 1 indication (median, $717 million [IQR, $284 million to $1.7 billion]; adjusted mean ratio, 0.6 [95% CI, 0.3-1.1]; P = .12) or multiple indications (median, $1.2 billion [IQR, $471 million to $2.4 billion]; adjusted mean ratio, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.1-1.5]; P = .20) (Figure).

Figure. Five-Year Net Sales, Stratified by Orphan Drug Designation.

Box-and-whisker plot for the first 5-year net sales after drug launch of drugs marketed between 2008 and 2016. Net sales are in 2021 US dollars and are shown on a logarithmic scale. Boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentiles; horizontal lines, medians; Xs, means. Whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR; each dot represents an individual drug’s net sales. Drugs were stratified by whether they were initially approved for orphan-designated or nonorphan indications. Orphan-designated drugs were further stratified by whether they had multiple indications during the first 5 years after marketing, including multiple orphan-designated indications (n = 10) or the addition of at least 1 nonorphan indication (n = 6). Not shown are 4 drugs with no reported sales (3 nonorphan and 1 orphan-designated with multiple indications).

Discussion

In this study, drugs initially approved for an orphan-designated condition were just as lucrative for their manufacturers as drugs developed for more common conditions. In 6 cases, indications for orphan-designated drugs were expanded to nonorphan indications within 5 years; in such cases, drug manufacturers benefit from Orphan Drug Act incentives and can extend to all uses the high prices set for the first indication.4 The study was limited to drugs made by public companies, excluded sales in non-US markets, and lacked data on sales volume.

Manufacturers offset smaller volumes of orphan drugs with higher prices; from 2008 to 2018, launch prices for orphan-designated drugs were 7 times higher than prices for nonorphan drugs.3 Congress could reform the statutory incentives in the Orphan Drug Act, such as by requiring manufacturers to repay tax credits when orphan-designated products are commercial successes.5

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Chua KP, Kimmel LE, Conti RM. Spending for orphan indications among top-selling orphan drugs approved to treat common diseases. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):453-460. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darrow JJ, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. FDA approval and regulation of pharmaceuticals, 1983-2018. JAMA. 2020;323(2):164-176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rome BN, Egilman AC, Kesselheim AS. Trends in prescription drug launch prices, 2008-2021. JAMA. 2022;327(21):2145-2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson SD, Dreitlein WB, Henshall C. Indication-Specific Pricing of Pharmaceuticals in the United States Health Care System. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Published March 2016. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://icerorg.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Final-Report-2015-ICER-Policy-Summit-on-Indication-specific-Pricing-March-2016_revised-icons-002.pdf

- 5.Sarpatwari A, Kesselheim AS. Reforming the Orphan Drug Act for the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(2):106-108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1902943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

Data Sharing Statement