Key Points

Question

Among patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis, does the combination of amoxicillin-clavulanate with prednisolone, compared with placebo with prednisolone, reduce mortality?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 284 patients, mortality at 60 days was 17.3% in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with 21.3% in the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.45-1.31).

Meaning

Among patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis receiving prednisolone, amoxicillin-clavulanate did not improve survival at 60-day follow-up compared with placebo.

Abstract

Importance

The benefits of prophylactic antibiotics for hospitalized patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis are unclear.

Objective

To determine the efficacy of amoxicillin-clavulanate, compared with placebo, on mortality in patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis and treated with prednisolone.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial among patients with biopsy-proven severe alcohol-related hepatitis (Maddrey function score ≥32 and Model for End-stage Liver Disease [MELD] score ≥21) from June 13, 2015, to May 24, 2019, in 25 centers in France and Belgium. All patients were followed up for 180 days. Final follow-up occurred on November 19, 2019.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1 allocation) to receive prednisolone combined with amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 145) or prednisolone combined with placebo (n = 147).

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 60 days. Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality at 90 and 180 days; incidence of infection, incidence of hepatorenal syndrome, and proportion of participants with a MELD score less than 17 at 60 days; and proportion of patients with a Lille score less than 0.45 at 7 days.

Results

Among 292 randomized patients (mean age, 52.8 [SD, 9.2] years; 80 [27.4%] women) 284 (97%) were analyzed. There was no significant difference in 60-day mortality between participants randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and those randomized to placebo (17.3% in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 21.3% in the placebo group [P = .33]; between-group difference, −4.7% [95% CI, −14.0% to 4.7%]; hazard ratio, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.45-1.31]). Infection rates at 60 days were significantly lower in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group (29.7% vs 41.5%; mean difference, −11.8% [95% CI, −23.0% to −0.7%]; subhazard ratio, 0.62; [95% CI, 0.41-0.91]; P = .02). There were no significant differences in any of the remaining 3 secondary outcomes. The most common serious adverse events were related to liver failure (25 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 20 in the placebo group), infections (23 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 46 in the placebo group), and gastrointestinal disorders (15 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 21 in the placebo group).

Conclusion and Relevance

In patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis, amoxicillin-clavulanate combined with prednisolone did not improve 2-month survival compared with prednisolone alone. These results do not support prophylactic antibiotics to improve survival in patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02281929

This randomized clinical trial assesses the effect of administration of prophylactic amoxicillin-clavulanate vs placebo on 60-day mortality in patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.

Introduction

Severe alcohol-related hepatitis1 is associated with a 20% to 30% mortality rate at 2-month follow-up.2 Oral prednisolone is recommended by practice guidelines to improve mortality in patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.1,3,4

Patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis are at increased risk for bacterial and fungal infection. Approximately 25% to 30% of patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis develop infection during corticosteroid treatment.1,5,6 Patients who develop infection while receiving corticosteroid therapy have higher rates of adverse outcomes, such as hepatorenal syndrome and worsening of liver insufficiency.

Bacterial compounds that enter the liver from the gut lumen contribute to liver inflammation.7 In ethanol-fed rodents, oral administration of lipopolysaccharide increased liver inflammation, while antibiotics improved alcohol-induced liver injury.8 These preliminary data suggested that antibiotics may improve outcomes in patients hospitalized for severe alcohol-related hepatitis by reducing hepatic inflammation and preventing infection.

Therefore, the AntibioCor trial was designed to test whether amoxicillin-clavulanate combined with prednisolone improved mortality in patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis compared with placebo combined with prednisolone.

Methods

Patient Selection

All patients provided written informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from relatives for patients who had severe encephalopathy. The study was approved by the French national institutional review board and ethics committee and complied with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki,9 and local laws. The study was also approved by the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament (French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products). The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2, respectively.

The trial was a 2-group, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Enrollment occurred between June 13, 2015, and May 24, 2019. Final follow-up occurred on November 19, 2019.

Patients aged 18 to 75 years who were diagnosed with severe alcohol-related hepatitis were recruited from 25 centers in France and Belgium. Patients were eligible if they met all of the following criteria: heavy drinking, defined as a daily alcohol consumption of 40 g/d or more (women) or 50 g/d or more (men), clinical diagnosis of alcohol-related hepatitis with recent onset of jaundice, histological confirmation by biopsy (via transjugular route according to routine French and Belgian practices), Maddrey score of 32 or higher, and Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 21 or higher. For more details about patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, see the eAppendix in Supplement 3.

Randomization

Assignment to a study group was based on the randomization list provided by an independent statistician who did not otherwise participate in the study. The investigator sent a fax to the sponsor for each included patient and the study randomization number was returned to the investigator as well as the number on the box of treatment to be administered to the patient. Randomization (using blocks of 4) was stratified by center. Patients were randomly assigned in a ratio of 1:1 to receive placebo or amoxicillin-clavulanate orally.

Study Interventions and Adherence Assessment

All participants received 40 mg/d of oral prednisolone for 30 days. The protocol did not provide any recommendations on the discontinuation of corticosteroids in case of a Lille score of 0.45 or greater at day 7. Participants randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate received amoxicillin, 1 g, and clavulanate, 125 mg, 3 times daily for 30 days. Participants randomized to placebo received 1 placebo packet for oral suspension 3 times daily.

After randomization, patients were evaluated in person weekly for the first 4 weeks and subsequently at day 45, day 60, and 3-month and 6-month follow-up.

Study drug adherence was assessed at each of the visits during the 30-day period. To facilitate assessment of adherence to treatment, patients received a diary and were instructed to return any unused drugs to the investigator on the last follow-up visit (Supplement 1). Based on this and on patient interview, adherence was classified as good or poor by investigators.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was 60-day all-cause mortality, defined as the time from the date of randomization to death due to any cause, censored at 60 days.

Secondary Outcomes

The protocol specified 6 secondary outcomes: all-cause mortality at 90-day follow-up, all-cause mortality at 180-day follow-up, incidence of infection at 60-day follow-up (defined as occurrence of any infectious event between randomization and 60 days after randomization), incidence of hepatorenal syndrome at 60-day follow-up (defined according to the international consensus definition at the time of writing the study protocol10), therapeutic response (defined as survival with a Lille score <0.45 at day 7), and rate of patients who had substantial improvement in liver function (defined as patients alive with a MELD score <17 at 60 days). The statistical analysis plan specified 4 secondary outcomes, which included all of the secondary outcomes in the protocol except mortality at 90- and 180-day follow-up. The Lille score ranges from 0 to 1, and a score of 0.45 or higher indicates nonresponse to medical therapy. The MELD score ranges from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis. No infection definition was prespecified in the study protocol. The diagnosis of infection was made by investigators based on clinical and biological criteria according to the site of infection. The threshold of 17 for the MELD score was selected because this threshold was associated with improved survival after liver transplant.11

Safety Outcomes

Safety was assessed for each patient at each follow-up visit by an investigator based on physical examination, patient-reported symptoms, and blood tests. Serious adverse events were assessed at 2 months (primary end point) and 6 months (end of study) after treatment initiation. Safety outcomes consisted of severe adverse events (defined as death or any event threatening life, hospitalization, prolonged hospitalization, injury, irreversible organ damage, or any additional serious health event that occurred between randomization and 6-month follow-up). The proportion of participants who experienced digestive symptoms (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain) from the date of randomization to 30-day follow-up was also assessed.

Nonserious adverse drug reactions were reported up to 2 months after treatment began.

Post Hoc Outcomes

Post hoc outcomes were transplant-free survival at 60-, 90-, and 180-day follow-up, MELD score at 60 days (continuous variable), and cumulative incidence of alcohol relapse at 180 days. We considered transplant-free survival to be a composite end point because death and transplant can both be considered medical treatment failures in severe alcohol-related hepatitis.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size of 280 patients (140 per group) was selected to attain a statistical power of 80% and a type I error of .05 to test whether combined prednisolone and amoxicillin-clavulanate was superior to prednisolone and placebo for the primary outcome of 60-day mortality using a 2-sided log-rank test considering 5% dropout. The power calculation was based on a multicenter randomized clinical trial in which patients with a MELD score greater than or equal to 21 had lower survival by 18.8% compared with patients with a MELD score of less than 21.12 In the current study, the investigators hypothesized that the amoxicillin-clavulanate would reduce mortality by 75% of this effect size compared with placebo, corresponding to an absolute reduction of 14%, given an expected mortality rate of 27% in placebo-treated patients.12

Statistical Analysis

Analyses for all primary and secondary efficacy outcomes were performed in all randomized patients regardless of protocol adherence, according to the intervention group assigned at randomization. Safety analyses were performed for patients who received at least 1 dose of study treatment (antibiotics or placebo) and according to treatment actually taken by patients independent of randomized groups.

The comparison of 60-day all-cause mortality between participants randomized to antibiotics and those randomized to placebo was performed using the log-rank test by treating patients who were lost to follow-up without vital status information and patients who underwent liver transplant as censored at the last available follow-up. The treatment effect sizes were assessed by the absolute differences in Kaplan-Meier mortality rates (amoxicillin-clavulanate vs placebo group) and by the hazard ratios of all-cause mortality estimated from the univariable Cox proportional hazards model. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals plots and the Grambsch and Therneau test. A sensitivity analysis was performed for all-cause mortality outcomes among patients treated without major deviation from study protocol (ie, received the nonallocated intervention, received steroids within the last 6 months, did not receive any treatment, failure to obtain sample with transjugular liver biopsy procedure, lack of confirmation of alcohol-related hepatis by liver biopsy, ongoing candidiasis at inclusion). A prespecified subgroup analysis according to infection status at randomization was performed (see Supplement 1 and section 5.3 of Supplement 2).

Heterogeneity of treatment effect size was evaluated by including the multiplicative interaction terms between infection status at randomization and treatment group in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

Comparison of secondary outcomes between the 2 groups was performed using the log-rank test for 90- and 180-day mortality and the Gray test (considering death as a competing event) for 60-day cumulative incidences of infection and hepatorenal syndrome considering patients who withdrew from the trial, underwent liver transplant, or were lost to follow-up before the 60-day time point as censored. For comparisons between the 2 groups of therapeutic response (Lille score <0.45 at 7 days) and substantial improvement in liver function rates (MELD score <17 at 60 days), χ2 tests were performed. Effect sizes were expressed as absolute differences in Kaplan-Meier estimates of mortality rates and in Kalbfleisch and Prentice estimates of infection, hepatorenal syndrome, therapeutic response, and improvement of liver function rates. Relative effect sizes for hazard ratios were computed for all-cause mortality outcomes, estimated by univariable Cox proportional hazards models, and by subhazard ratios for 60-day infection and incidence of hepatorenal syndrome, estimated by the univariable Fine and Gray model treating death as a competing event. For therapeutic response and liver function improvement rates, relative risks were computed.

Post Hoc Analyses

Because the proportional hazards assumption was not satisfied for the incidence of infection, the effect size in the incidence of infection was computed for 2 separate periods (0- to 30-day follow-up vs 31- to 60-day follow-up) using the Fine and Gray model with time-dependent coefficients.

In a sensitivity analysis, the analysis for mortality was repeated for the outcome of transplant-free survival. MELD scores among patients alive at 60 days were compared using the t test, and mean between-group differences are reported as effect sizes. The cumulative incidence of alcohol relapse was estimated using Kalbfleisch and Prentice estimates and compared between the 2 groups using the Gray test, considering death as a competing event. Subhazard ratios were estimated using the Fine and Gray univariable model. Comparison of mortality outcomes between the 2 groups adjusted for alcohol relapse was performed using a multivariable Cox regression model including alcohol relapse as a time-dependent covariate.

No imputation for missing data was performed. All statistical tests were 2-sided and P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Data were analyzed using SAS release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Randomization and Baseline Patient Characteristics

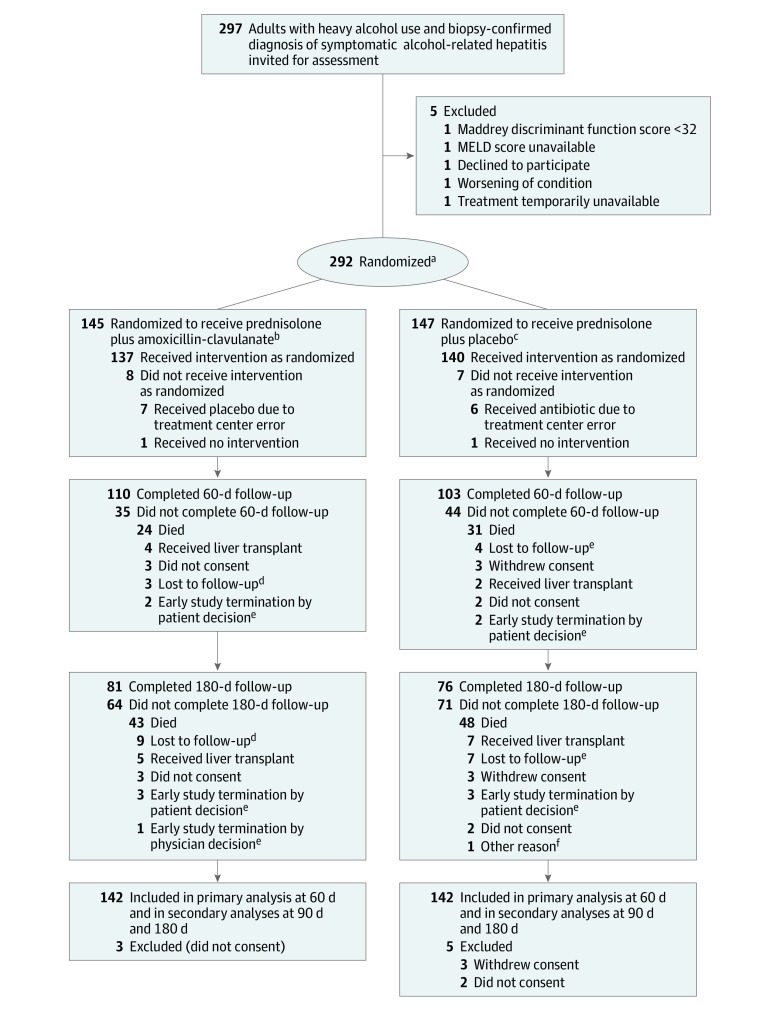

A total of 297 individuals were assessed for eligibility and 292 were enrolled from 24 centers (median number of patients per center, 9 [IQR, 2-60]); 145 patients were randomized to the prednisolone plus amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 147 were randomized to the prednisolone plus placebo group. Fifteen patients (8 patients from the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 7 patients from the placebo group) did not receive their allocated intervention. Three patients randomized to the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 5 randomized to placebo were excluded due to absence or withdrawal of consent, resulting in 142 patients assigned to each group included in the analysis (Figure 1). Ten major deviations occurred in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 8 in the placebo group; thus, 132 patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 134 in the placebo group were included in sensitivity analysis restricted to patients without major deviations from the study protocol (eTable 1 in Supplement 3).

Figure 1. Participant Flow in a Trial of Prednisolone and Amoxicillin-Clavulanate for Alcohol-Related Hepatitis.

MELD indicates Model for End-stage Liver Disease. See footnote d in Table 1 for description of MELD score calculation.

aStratified by center.

bThree patients who were randomized did not meet inclusion criteria: biopsy failure (n = 1), patient did not receive any treatment (n = 1), and patient received steroids within the last 6 months (n = 1).

cTwo patients who were randomized did not meet the inclusion criteria: biopsy did not confirm alcohol-related hepatitis (n = 1) and patient had ongoing infection (n = 1).

dVital status was unknown for 1 patient.

eAll patients had known vital status.

fThis patient was included at the beginning of the study, before the amendment to 90-day and 180-day survival was accepted.

Baseline characteristics of randomized participants are shown in Table 1. Thirty-one patients (21.8%) in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 26 (18.3%) in the placebo group had previously been treated with antibiotics for infection and were randomized after a washout period of 7 days without antibiotics (Supplement 1). Treatment adherence at each visit (days 7, 14, 21, and 28) was defined by physicians as good in 91.9%, 92.1%, 93.0%, and 86.3% of patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and in 91.9%, 88.5%, 85.6%, and 78.2% of patients in the placebo group, respectively. Adherence to corticosteroids at each visit was defined as good in 97.1%, 92.3%, 94.3%, and 89.2% of participants randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 97.9%, 88.2%, 83.5%, and 86.2% of participants randomized to placebo, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 142) | Placebo (n = 142) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 52.8 (8.7) | 52.5 (9.7) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 40 (28.2) | 38 (26.8) |

| Male | 102 (71.8) | 104 (73.2) |

| Clinical characteristics, No. (%) | ||

| Ascites | 92 (74.8) | 85 (66.9) |

| Encephalopathy | 17 (12.0) | 17 (12.0) |

| Antibiotics before randomization | 31 (21.8) | 26 (18.3) |

| Laboratory measurementsa | ||

| White blood cells, median (IQR), /μL | 9615 (7200-13 240) | 10 190 (6800-14 900) |

| Neutrophils, median (IQR), /μL | 7200 (4870-10 330) [n = 135] | 7450 (4470-11 499) [n = 135] |

| Prothrombin rate, mean (SD), % | 40.1 (11.3) | 39.3 (11.1) |

| Prothrombin time, median (IQR), s | 22.6 (19.9-26.7) | 23.9 (20.6-27.7) |

| Prothrombin time ratio, mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.5) |

| International normalized ratio, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.6) [n = 140] | 2.1 (0.6) |

| Bilirubin, median (IQR), μmol/L | 272 (156-412) | 310 (179-425) |

| Urea, median (IQR), mmol/L | 3.4 (2.4-5.8) [n = 135] | 4.3 (2.6-7.3) [n = 135] |

| Creatinine, median (IQR), μmol/L | 61.7 (47.0-79.0) | 70.5 (52.0-97.0) |

| Albumin, mean (SD), g/L | 25.9 (5.8) [n = 129] | 25.9 (5.5) [n = 131] |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, mean (SD), U/L | 117 (46) [n = 141] | 121 (53) |

| Prognostic scores | ||

| Maddrey discriminant function score, median (IQR)b | 64.1 (48.2-81.5) | 69.7 (53.7-89.4) |

| Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score, median (IQR)c | 10 (9-10) [n = 134] | 10 (9-11) [n = 135] |

| MELD score, mean (SD)d | 24.9 (3.8) [n = 141] | 25.8 (4.0) |

Reference values for laboratory studies were site dependent.

The Maddrey discriminant function is a measure of severity of alcohol-related hepatitis and was calculated as follows: 4.6 × (patient’s prothrombin time in seconds − matched control’s prothrombin time in seconds) + patient’s serum bilirubin level in milligrams per deciliter. A score of more than 32 indicates severe alcoholic hepatitis and is the threshold for initiating glucocorticoid treatment.

The Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score ranges from 5 to 12, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis.13

The Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was calculated as follows: (9.57 × log e creatinine in milligrams per deciliter) + (3.78 × log e bilirubin in milligrams per deciliter) + (11.20 × log e international normalized ratio) + 6.43. Scores range from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis.

Temporary or permanent discontinuation of study treatment occurred in 19 patients treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate and 36 patients treated with placebo (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). Causes of death are given in eTable 3 in Supplement 3. Five patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 7 in the placebo group received a liver transplant during the study period.

Primary Outcome

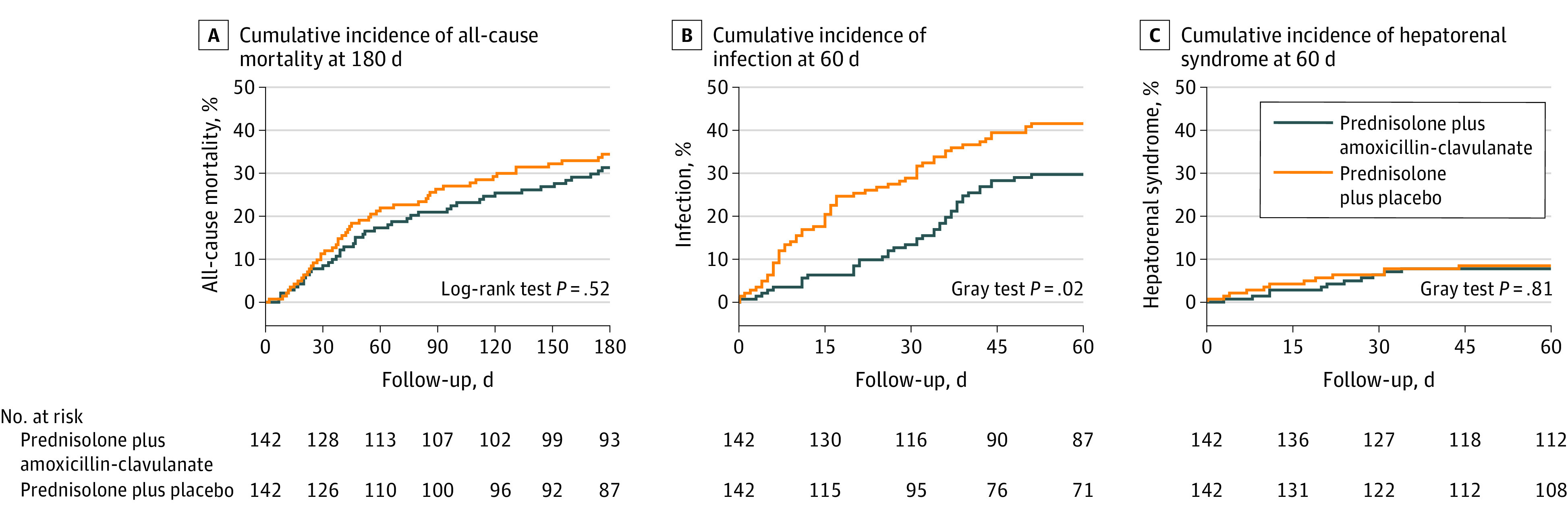

At 60-day follow-up, all-cause mortality rates were 24 of 142 (17.3%) among patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 31 of 142 (21.9%) in patients randomized to placebo (log-rank P = .33) (Table 2 and Figure 2). The absolute difference in 60-day mortality was −4.7% (95% CI, −14.0% to 4.7%), with a hazard ratio of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.45-1.31) in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with the placebo group. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated.

Table 2. Efficacy Outcomes.

| Outcomesa | Amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 142) | Placebo (n = 142) | Unadjusted absolute difference (95% CI) | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| All-cause mortality at 60 d, No./total (%) | 24/142 (17.3) | 31/142 (21.9) | −4.7 (−14.0 to 4.7) | 0.77 (0.45-1.31) | .33 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| All-cause mortality at 90 d, No./total (%) | 29/142 (21.0) | 37/142 (26.3) | −5.3 (−15.3 to 4.7) | 0.78 (0.47-1.27) | .30 |

| All-cause mortality at 180 d, No./total (%) | 43/142 (31.3) | 48/142 (34.4) | −3.1 (−14.3 to 8.0) | 0.87 (0.57-1.32) | .52 |

| Infection at 60 d, No./total (%) | 42/142 (29.7) | 59/142 (41.5) | −11.8 (−23.0 to −0.7) | 0.62 (0.41-0.91)c | .02 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome at 60 d, No./total (%) | 11/142 (7.7) | 12/142 (8.5) | −0.7 (−7.1 to 5.7) | 0.91 (0.40-2.05)c | .81 |

| Lille score <0.45 at 7 d, mean (SD)d | 80/141 (56.7) | 76/138 (55.1) | 1.7 (−10.0 to 13.4) | 1.03 (0.83-1.27)e | .78 |

| MELD score <17 at 60 d, mean (SD)f | 48/100 (48.0) | 50/91 (55.0) | −7.0 (−21.1 to 7.3) | 0.87 (0.66-1.16)e | .34 |

| Post hoc outcomes | |||||

| MELD score at 60 d, mean (SD)f | 16.9 (4.8) [n = 100] | 17.3 (6.2) [n = 91] | −0.41 (−1.98 to 1.17) | .61 | |

| Infection, No./total (%)g | |||||

| At 0-30 d | 19/142 (13.4) | 41/142 (28.9) | −15.5 (−24.9 to −6.1) | 0.41 (0.24-0.70)c | .001 |

| At 31-60 d | 23/116 (20.0) | 18/95 (18.9) | 0.01 (−9.8 to 11.9) | 1.06 (0.57-1.96)c | .86 |

For all-cause mortality, percentages are the Kaplan-Meier estimated rates, and for infection and hepatorenal syndrome, percentages are the Kalbfleisch and Prentice estimated rates of cumulative incidence treating death as a competing event. There was no prespecified definition of infection in the study protocol. The diagnosis of infection was made by investigators based on standard medical management (summarized by Louvet et al5).

Hazard ratios were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Data are subhazard ratios, calculated using the Fine and Gray model, treating death as a competing event.

Data for patients alive at 7 days without a liver transplant: a Lille score of 0.45 or higher indicates nonresponse to medical therapy. The Lille score ranges from 0 to 1 and was calculated using the following formula: exp (−R)/(1 + exp [−R]), where R = (3.19 − 0.101 × age in years) + (0.147 × albumin on day 0 in grams per liter) + ([0.0165 × change in bilirubin between day 0 and day 7 of medical therapy in micromoles per liter] − [0.206 × renal insufficiency {rated as 0 if absent and 1 if present}] − [0.0065 × bilirubin level on day 0 in micromoles per liter] − [0.0096 × prothrombin time in seconds]).

Data are relative risks.

Data for patients alive at 60 days without a liver transplant: the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was calculated as follows: (9.57 × log e creatinine in milligrams per deciliter) + (3.78 × log e bilirubin in milligrams per deciliter) + (11.20 × log e international normalized ratio) + 6.43. Scores range from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis. The cutoff value of 17 for the MELD score was chosen to define a substantial improvement in liver function because this cutoff has been shown to be associated with a survival benefit in liver transplant.11

To accommodate that the proportional hazards assumption was not satisfied for the effect of the intervention vs placebo for infection, the effect was modeled using time-dependent coefficients.

Figure 2. 180-Day Cumulative Incidence of All-Cause Mortality, 60-Day Cumulative Incidence of Infection, and 60-Day Cumulative Incidence of Hepatorenal Syndrome.

Incidence of death was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method by treating patients lost to follow-up without vital status information and patients who underwent liver transplant as censored at the last available follow-up. Median observation time was 180 (IQR, 95-180) days in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 180 (IQR, 80-180) days in the placebo group. Incidences of infection and hepatorenal syndrome were estimated using the Kalbfleisch and Prentice method by treating death as a competing event. There was no prespecified definition of infection in the study protocol. The diagnosis of infection was made by investigators based on standard medical management (summarized by Louvet et al5).

Secondary Outcomes

90-Day and 180-Day All-Cause Mortality

There was no deviation in the proportional hazards assumption at the 90-day and 180-day time points. At 90-day follow-up, mortality rates were 21.0% in patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 26.3% in patients randomized to placebo (P = .30; absolute difference, −5.3% [95% CI, −15.3% to 4.7%]; hazard ratio, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.47-1.27]). At 180-day follow-up, mortality rates were 31.3% in patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 34.4% in patients randomized to placebo (P = .52; absolute difference, −3.1% [95% CI, −14.3% to 8.0%]; hazard ratio, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.57-1.32]) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

60-Day Incidence of Infection

At 60-day follow-up, rates of infection were 29.7% (n = 42 events) in patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 41.5% (n = 59 events) in patients randomized to placebo (difference, −11.8% [95% CI, −23.0% to −0.7%]; subhazard ratio, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.41-0.91]) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Types of infections are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 3.

60-Day Incidence of Hepatorenal Syndrome

At 60-day follow-up, 7.7% of patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 8.5% of patients randomized to placebo experienced hepatorenal syndrome (difference, −0.7 [95% CI, −7.1% to 5.7%]; subhazard ratio, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.40-2.05]) (Table 2).

Therapeutic Response and Liver Function Scores

At 7-day follow-up, 56.7% of patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 55.1% of patients randomized to placebo had a Lille score less than 0.45 (difference, 1.7%;95% CI, −10.0% to 13.4%). At 60-day follow-up, 48.0% of patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 55.0% randomized to placebo had a MELD score less than 17 (difference, −7.0%; 95% CI, −21.1% to 7.3%) (Table 2).

Safety Outcomes

At 60-day follow-up, 230 adverse events were reported among 68 patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and among 77 patients in the placebo group (Table 3). The most common serious adverse events were related to liver failure (25 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 20 in the placebo group), infections (23 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 46 in the placebo group), and gastrointestinal disorders (15 in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and 21 in the placebo group). Clostridioides difficile infection occurred in 1 patient in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group and in 3 patients in the placebo group. No patients developed drug-induced liver disease. Bacteremia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, pneumonias, and Pneumocystis pneumonias were observed in 2, 2, 7, and 8 patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with 10, 9, 7, and 7 patients in the placebo group, respectively.

Table 3. Serious Adverse Events With 5 or More Occurrences During the First 60 Days of Follow-upa.

| Adverse events | No. of patients | No. of events | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate (n = 141)b | Placebo (n = 143)b | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Placebo | |

| Any serious adverse event | 68 | 77 | 105 | 125 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 31 | 24 | 34 | 27 |

| Hepatic failurec | 23 | 19 | 25 | 20 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| Liver nodule compatible with hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Drug-induced liver injury | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infectionsd | 18 | 37 | 23 | 46 |

| Pneumonia | 4 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

| Bacteremia | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 2 | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Skin and joint infection | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Septic shock | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Clostridioides difficile infection | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Fungal infection | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Other infection | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorderse | 15 | 21 | 15 | 21 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 14 | 18 | 14 | 18 |

| Metabolic and endocrine disordersf | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Acute kidney failure not related to hepatorenal syndrome | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| General disorders (eg, general physical health deterioration, fever without sepsis) | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

Seriousness criteria as defined by Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines and EU Clinical Trial Directive 2001/20/EC: any adverse event that results in death, is life-threatening, requires in-patient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, is a congenital anomaly/birth defect, or is considered as clinically significant by the investigator. Less frequent serious adverse events are reported in eTable 9 in Supplement 3. Severe adverse events occurring up to 180 days are reported in eTable 5 in Supplement 3. Adverse drug reactions occurring up to 2 months are reported in eTable 6 in Supplement 3.

Adverse events are reported according to treatment actually taken by a patient independent of randomized group. Adverse events were assessed for all patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug and had follow-up at 2 months.

Including acute hepatic failure, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, jaundice, abnormal hepatic test results, hydrothorax, and new occurrence of alcoholic hepatitis.

Two serious adverse events were potential treatment-related events: 1 case in each group of C difficile infection.

Two serious adverse events were potential treatment-related events: 2 cases of diarrhea in the placebo group.

One serious adverse event was a potential treatment-related event: 1 case of hypokalemia in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group (also deemed related to prednisolone).

Serious adverse events occurring within the first 180 days are reported in eTable 5 in Supplement 3.

Thirty-six nonserious drug reactions were reported in 35 patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 23 were reported in 22 patients randomized to placebo at 60-day follow-up (end of treatment). Diarrhea and abdominal pain were reported in 22 and 4 patients in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group, respectively, and in 16 and 2 patients in the placebo group, respectively (eTable 6 in Supplement 3).

Among 185 patients who had a rectal swab, the proportion with multidrug-resistant bacteria was higher in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with the placebo group (29/91 [31.9%] vs 8/94 [8.5%]).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses of the Primary Outcome

In sensitivity analyses restricted to patients without major deviation to study protocol, there was no significant difference in mortality at 60-day follow-up between the 2 groups (17.8% in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with 22.5% in the placebo group; absolute difference, −4.7% [95% CI, −14.4% to 5.1%]; hazard ratio, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.44-1.34])

There was no significant interaction between the presence or absence of infection treated prior to randomization and 60-day all cause mortality (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). There was no statistically significant difference in mortality rates between the amoxicillin-clavulanate and the placebo groups (16.1% vs 35.0%; hazard ratio, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.13-1.16) in patients with infection before randomization.

Post Hoc Analyses

After the first month of therapy, rates of infection were 13.4% in patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 28.9% in patients randomized to placebo (between-group difference, −15.5% [95% CI, −24.9% to −6.1%]; subhazard ratio, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.24-0.70]). Between days 31 and 60, rates of infection were 20.0% in patients randomized to amoxicillin-clavulanate and 18.9% in patients randomized to placebo (between-group difference, 0.01% [95% CI, −9.8% to 11.9%; subhazard ratio, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.57-1.96]) (Table 2).

Among patients who were alive at 60 days, the MELD score at 60 days was not significantly different between the 2 groups (mean, 16.9 [SD, 4.8] in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with 17.3 [SD, 6.2] in the placebo group; mean difference, −0.41 [95% CI, −1.98 to 1.17]). In post hoc sensitivity analyses, rates of mortality or transplant at 60 days were 19.8% in the amoxicillin-clavulanate group compared with 23.2% in the placebo group (between-group difference, −3.5% [95% CI, −13% to 6.2%]; hazard ratio, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.50-1.40]) (eTable 7 in Supplement 3).

Alcohol relapse during follow-up was not significantly different between the 2 groups (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3) and did not influence 60-, 90-, or 180-day survival (eTable 8 in Supplement 3).

Discussion

In this double-blind randomized clinical trial of 284 patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis, amoxicillin-clavulanate combined with prednisolone treatment did not significantly improve 2-month survival compared with prednisolone alone at 60-day follow-up. At 60-day follow-up, amoxicillin-clavulanate reduced the rate of infection, but none of the remaining 5 secondary outcomes were significantly different between the 2 groups. This study does not support adding amoxicillin-clavulanate to prednisolone to reduce mortality in patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.

Preclinical studies and preliminary evidence in human studies suggested that antibiotics may improve liver function in patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.14,15,16 Although animal models suggested that antibiotics may reduce liver inflammation and improve hepatic function, this trial showed no effect of amoxicillin-clavulanate combined with prednisolone on liver function compared with placebo combined with prednisolone.

Findings reported herein are consistent with prior smaller randomized clinical trials that tested the benefits of prophylactic antibiotics in patients with liver disease. For example, in a randomized clinical trial of 291 patients with Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis, prophylactic norfloxacin for 6 months reduced the incidence of infection compared with placebo, but did not improve survival.17 In a randomized clinical trial of 32 patients with alcohol-related hepatitis, prophylactic antibiotic therapy with rifaximin for 4 weeks did not significantly improve inflammatory markers and amino acid measures compared with standard medical treatment.18 A case-control study of 21 patients with alcohol-related hepatitis treated with rifaximin reported a lower incidence of infection compared with 42 control patients at 90-day follow-up, but there was no survival benefit.19

Although prophylactic antibiotics did not improve outcomes in patients with alcohol-related hepatitis in this clinical trial, patients hospitalized for alcohol-related liver disease have a high risk of infection. Clinicians should identify infections as soon as possible and implement appropriate treatment to improve outcomes in patients with alcohol-related hepatitis. The results of this study do not change the current protocol for the use of antibiotics, which should be prescribed only in patients with infection.

The study protocol for this clinical trial did not recommend the stopping rule for nonresponders that is recommended in current practice guidelines. When this clinical trial was designed, it was anticipated that antibiotics would significantly improve the outcome and the biological course based on prior experimental data showing that antibiotics reduced liver injury. Prior work showed that continuation of corticosteroids in nonresponders was neither beneficial nor harmful for survival.20 However, it is possible that the absence of a stopping rule for corticosteroids affected the results.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the study was designed based on the hypothesis that antibiotics would reduce mortality by 75% compared with placebo. The clinical trial lacked statistical power to detect smaller benefits. Second, it is possible that a longer or shorter duration of antibiotics may have been associated with a different outcome. Third, infections were not formally adjudicated and it is possible that there was misclassification of infections. Fourth, adherence to antibiotics was classified as “good” without a formal definition or criterion for good antibiotic or placebo adherence. Fifth, missing data were not accounted for in the analyses. Sixth, interruptions in study drug treatment were required during the trial as part of clinical care for the randomized patients.

Conclusions

In patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis, amoxicillin-clavulanate combined with prednisolone did not improve 2-month survival compared with prednisolone alone. These results do not support prophylactic antibiotics to improve survival in patients hospitalized with severe alcohol-related hepatitis.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Major Deviations in the Two Groups

eTable 2. Reasons for Treatment Interruption in the Two Groups

eTable 3. Causes of Death in the Two Groups During the 6-Month Follow-up

eTable 4. Distribution of Infection Occurring in the First 60 Days in the Two Groups

eTable 5. Total Number of Serious Adverse Events Reported Within the First 6 Months (End of Follow-up) in the Two Groups

eTable 6. Adverse Drug Reactions Reported in the Safety Population (n=141 in the Experimental Arm and n=143 in the Placebo Arm) up to 2 Months

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses on All-Cause Mortality at 2-, 3 and 6-Months

eTable 8. Comparison in Alcohol Relapse During the 180-Day Follow-up Between the Two Study Groups

eTable 9. Serious Adverse Events Reported in the Safety Population During the First 60 Days of Follow-up (Primary Endpoint)

eFigure 1. Treatment Effect Size on 60-Day Survival (Primary Outcome) According to Treated Infection at Baseline

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Alcohol Relapse During the 180-Day Follow-up Estimated Using Kalbfleisch and Prentice by Treating Death as Competing Event

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):154-181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louvet A, Mathurin P. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(4):231-242. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases. Hepatology. 2020;71(1):306-333. doi: 10.1002/hep.30866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louvet A, Thursz MR, Kim DJ, et al. Corticosteroids reduce risk of death within 28 days for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, compared with pentoxifylline or placebo—a meta-analysis of individual data from controlled trials. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):458-468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louvet A, Wartel F, Castel H, et al. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):541-548. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1619-1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao B, Ahmad MF, Nagy LE, Tsukamoto H. Inflammatory pathways in alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2019;70(2):249-259. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, et al. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(1):218-224. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, et al. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56(9):1310-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merion RM, Schaubel DE, Dykstra DM, et al. The survival benefit of liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(2):307-313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathurin P, Louvet A, Duhamel A, et al. Prednisolone with vs without pentoxifylline and survival of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1033-1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forrest EH, Morris AJ, Stewart S, et al. The Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score identifies patients who may benefit from corticosteroids. Gut. 2007;56(12):1743-1746. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustot T, Fernandez J, Szabo G, et al. Sepsis in alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):1031-1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathurin P, Deng QG, Keshavarzian A, et al. Exacerbation of alcoholic liver injury by enteral endotoxin in rats. Hepatology. 2000;32(5):1008-1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(6):1513-1524. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau R, Elkrief L, Bureau C, et al. Effects of long-term norfloxacin therapy in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1816-1827. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimer N, Meldgaard M, Hamberg O, et al. The impact of rifaximin on inflammation and metabolism in alcoholic hepatitis. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0264278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez C, Ventura-Cots M, Sala M, et al. Effect of rifaximin on infections, acute-on-chronic liver failure and mortality in alcoholic hepatitis. Liver Int. 2022;42(5):1109-1120. doi: 10.1111/liv.15207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathurin P, O’Grady J, Carithers RL, et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Gut. 2011;60(2):255-260. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eTable 1. Major Deviations in the Two Groups

eTable 2. Reasons for Treatment Interruption in the Two Groups

eTable 3. Causes of Death in the Two Groups During the 6-Month Follow-up

eTable 4. Distribution of Infection Occurring in the First 60 Days in the Two Groups

eTable 5. Total Number of Serious Adverse Events Reported Within the First 6 Months (End of Follow-up) in the Two Groups

eTable 6. Adverse Drug Reactions Reported in the Safety Population (n=141 in the Experimental Arm and n=143 in the Placebo Arm) up to 2 Months

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses on All-Cause Mortality at 2-, 3 and 6-Months

eTable 8. Comparison in Alcohol Relapse During the 180-Day Follow-up Between the Two Study Groups

eTable 9. Serious Adverse Events Reported in the Safety Population During the First 60 Days of Follow-up (Primary Endpoint)

eFigure 1. Treatment Effect Size on 60-Day Survival (Primary Outcome) According to Treated Infection at Baseline

eFigure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Alcohol Relapse During the 180-Day Follow-up Estimated Using Kalbfleisch and Prentice by Treating Death as Competing Event

Data Sharing Statement