Abstract

The distribution of the two isotypes of tbpB in a collection of 108 serogroup B meningococcal strains belonging to the four major clonal groups associated with epidemic and hyperendemic disease (the ET-37 complex, the ET-5 complex, lineage III, and cluster A4) was determined. Isotype I strains (with a 1.8-kb tbpB gene) was less represented than isotype II strains (19.4 versus 80.6%). Isotype I was restricted to the ET-37 complex strains, while isotype II was found in all four clonal complexes. The extent of the allelic diversity of tbpB in these two groups was studied by PCR restriction analysis and sequencing of 10 new tbpB genes. Four major tbpB gene variants were characterized: B16B6 (representative of isotype I) and M982, BZ83, and 8680 (representative of isotype II). The relevance of these variants was assessed at the antigenic level by the determination of cross-bactericidal activity of purified immunoglobulin G preparations raised to the corresponding recombinant TbpB (rTbpB) protein against a panel of 27 strains (5 of isotype I and 22 of isotype II). The results indicated that rTbpB corresponding to each variant was able to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies. However, the number of strains killed with an anti-rTbpB serum was slightly lower than that obtained with an anti-TbpA+B complex. None of the sera tested raised against an isotype I strain was able to kill an isotype II strain and vice versa. None of the specific antisera tested (anti-rTbpB or anti-TbpA+B complex) was able to kill all of the 22 isotype II strains tested. Moreover, using sera raised against the C-terminus domain of TbpB M982 (amino acids 352 to 691) or BZ83 (amino acids 329 to 669) fused to the maltose-binding protein, cross-bactericidal activity was detected against 12 and 7 isotype II strains, respectively, of the 22 tested. These results suggest surface accessibility of the C-terminal end of TbpB. Altogether, these results show that although more than one rTbpB will be required in the composition of a TbpB-based vaccine to achieve a fully cross-bactericidal activity, rTbpB and its C terminus were able by themselves to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies.

Meningococcal disease is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity throughout the world. Neisseria meningitidis strains of serogroup B are the most common cause of sporadic meningococcal diseases in developed countries (31). Within serogroup B, most disease is caused by a limited number of groups of genetically related bacteria that have been referred to as complexes, clusters, or lineages. These are the ET-5 complex, the ET-37 complex, lineage III, and cluster A4 (7). These clonal groups have been associated with an increased rate of disease and reinforce the need for a serogroup B vaccine. A serogroup B polysaccharide-based vaccine is not yet available. Some issues related to its structure identity with host cell molecules, such as neural cell adhesion molecule (13), has led research to focus on other bacterial components. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis studies have shown that lineages of serogroup B meningococci diversify during spread and that their members often change antigenically (28, 30, 46), raising real concerns for the development of a vaccine (46) and reinforcing the need to study antigenic and genetic variation of vaccine target antigens among members of these lineages.

Among antigens considered for inclusion in a future meningococcal vaccine is the human transferrin receptor, which is composed of two subunits, TbpA and TbpB (43). TbpB has several attributes of a good vaccine candidate: it is a surface-exposed molecule, expressed in vivo during infection (1, 2, 3, 6, 16, 23), and it elicits protective and bactericidal antibodies in laboratory animals (3, 10, 24) and opsonic antibodies in humans (23). Moreover, a phase I clinical trial has shown that a recombinant TbpB (rTbpB) purified from Escherichia coli was safe and immunogenic in humans (B. Danve, F. Guinet, E. Boutry, D. Speck, M. Cadoz, L. Lissolo, X. Nassif, and M. J. Quentin-Millet, presented at the 11th Int. Pathogenic Neisseria Conf., 1998). Besides the meningococcal TbpB, native TbpB and rTbpB from other bacterial pathogens were shown to confer protection or induce bactericidal antibodies against the corresponding homologous strain. This protective role of the antibodies has been shown with native TbpB (initially named TfbA) from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (41) or rTbpB from Haemophilus influenzae (25), Moraxella catarrhalis (29) and, more recently, Pasteurella haemolytica (34).

The variability observed in the TbpB protein from N. meningitidis (12, 17) has raised questions about its capacity to be used as a broadly cross-reactive antigen. However, we have shown that while TbpB varied among strains, antigenic and genomic features of TbpB and tbpB allowed the meningococcal strains to be classified into two major families: isotype I (tbpB gene of 1.8 kb and TbpB protein with a mass of approximately 68 kDa) or isotype II (tbpB gene of 2.1 kb and TbpB protein with a mass of approximately 80 to 90 kDa) (38).

Protection against meningococcal disease has been correlated with the persistence of bactericidal antibodies, and various lines of evidence have highlighted the importance of humoral bactericidal activity in host defense against N. meningitidis (14). In this context, several studies on Tbp molecules have investigated the induction of cross-bactericidal antibodies, and the specific role of TbpB in regard to this induction was investigated (1, 10, 15, 24, 29, 34, 39, 40). Our previous work with rTbpB molecules purified from strain M982 (representative of isotype II strains) showed that it was possible to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies against isotype II strains, but no cross-bactericidal activity was seen with strain B16B6, a representative of isotype I (40). However, to date, total cross-bactericidal activity has not been reached with any anti-TbpB or rTbpB tested. Major TbpB variants have been identified among isotype II strains, suggesting that more than one TbpB protein may be required to raise fully cross-bactericidal sera within this isotype (39, 40). The variability of tbpB gene and the TbpB protein has not yet been assessed on a representative collection of serogroup B strains. The distribution of the two isotypes, I and II, is not known among strains belonging to the different clonal complexes implicated in serogroup B meningococcal disease.

The aim of the present study was to assess the distribution of the two isotypes of tbpB among serogroup B strains belonging to the four major clonal complexes responsible for meningococcal B disease and to characterize the extent of the allelic diversity of the two isotypes. A collection of 108 isolates was analyzed by PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism and analysis and sequencing of representative tbpB genes. A panel of 27 strains representative of the diversity of the tbpB gene was then selected to assess the number of rTbpB variants necessary to induce the broadest possible cross-bactericidal activity. Moreover, using rTbpB produced in fusion with the maltose-binding protein (MBP) corresponding to different parts of the TbpB molecule, we investigated which part of the TbpB molecule was involved in the induction of cross-reacting antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and E. coli constructions.

The 108 meningococcal isolates examined here are listed in Table 1. The collection included 30 strains belonging to the ET-5 complex previously described (39), 29 strains belonging to lineage III (the 17 isolates from New Zealand were kindly provided by D. R. Martin), 27 strains belong to cluster A4, and 22 isolates of the ET-37 complex. Five reference strains belonging to other clonal complexes, B16B6, M982, M978, S3032, and 6940 (21, 27), were also included. The isolates were characterized by their combination of alleles at 14 enzyme loci as described previously (8) and then serotyped and subtyped with monoclonal antibodies (33). For DNA extraction, N. meningitidis strains were grown on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates (Difco).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of serogroup B strains and determination of their tbpB gene isotype

| Straina | Clonal group | Serogroup type:subtype(s) | Origin | Yr | tbpB gene sizeb (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106* | ET-37 | B:NT:P1.5 | Japan | 1988 | 1.8 |

| 316 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1986 | 1.8 |

| 331 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1985 | 1.8 |

| 2713 | ET-37 | B:NT:P1.2 | China | 1974 | 1.8 |

| 2717* | ET-37 | B:NT:P1.2 | China | 1974 | 1.8 |

| 8108 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1979 | 1.8 |

| 8732 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.15 | United States | 1987 | 1.8 |

| 901256* | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | The Netherlands | 1990 | 2.1 |

| 910053 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1985 | 1.8 |

| 35/92 | ET-37 | B:2b:NST | Argentina | 1992 | 1.8 |

| 64/92* | ET-37 | B:2b:NST | Argentina | 1992 | 1.8 |

| B16B6* | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | 1.8 | ||

| HF106 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Canada | 1970 | 1.8 |

| HF173 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Canada | 1970 | 1.8 |

| HF197 | ET-37 | B:2a:NST | South Africa | 1970 | 1.8 |

| HF69 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1970 | 1.8 |

| HF76 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | South Africa | 1970 | 1.8 |

| M986* | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.5,2 | 1.8 | ||

| P2 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Norway | 1969 | 1.8 |

| P20 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Norway | 1969 | 1.8 |

| P229 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Norway | 1975 | 1.8 |

| P95 | ET-37 | B:2a:P1.2 | Norway | 1973 | 1.8 |

| 44* | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Finland | 1993 | 2.1 |

| 52* | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Finland | 1993 | 2.1 |

| 8679 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chile | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 8680* | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chili | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 8694 | ET-5 | B:15:− | Chile | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 8696 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chile | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 8710* | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chile | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 8726 | ET-5 | B:4:P1.3 | Chili | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 230/89 | ET-5 | B:4:P1.15 | Cuba | 1989 | 2.1 |

| 28I | ET-5 | B:4:P1.15 | Spain | 1992 | 2.1 |

| 32/94 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 504/91 | ET-5 | B:4:− | Argentina | 1991 | 2.1 |

| 58/94 | ET-5 | B:15:12,13a | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 92/94 | ET-5 | B:15:7,16 | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| AO15 | ET-5 | B:4:P1.12 | South Africa | 1988 | 2.1 |

| AO20 | ET-5 | B:4:P1.15 | South Africa | 1989 | 2.1 |

| BB393 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chile | 1986 | 2.1 |

| BB396 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3 | Chile | 1986 | 2.1 |

| BZ169 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.16 | The Netherlands | 1985 | 2.1 |

| BZ83* | ET-5 | B:15:− | The Netherlands | 1984 | 2.1 |

| G111/91 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3,15 | Iceland | 1991 | 2.1 |

| M359/91 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.3,15 | Iceland | 1991 | 2.1 |

| M871 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Israel | 1992 | 2.1 |

| MA-5850 | ET-5 | B:4:P1.15 | Spain | 1985 | 2.1 |

| NG080 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.16 | Norway | 1981 | 2.1 |

| NG1/84 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.16 | Norway | 1985 | 2.1 |

| NG144/82 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.16 | Norway | 1982 | 2.1 |

| NG3/83 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.16 | Norway | 1984 | 2.1 |

| NGP355 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.15 | Norway | 1975 | 2.1 |

| NGPB24 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Norway | 1984 | 2.1 |

| NGPB37 | ET-5 | B:15:P1.7,16 | Norway | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 400* | Lineage III | B | Austria | 1991 | 2.1 |

| 931905 | Lineage III | B | The Netherlands | 1993 | 2.1 |

| 45/96 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.7,4,14 | Norway | 1996 | 2.1 |

| 88/03415 | Lineage III | B:−:P1.15 | Scotland | 1988 | 2.1 |

| 90/94* | Lineage III | B:4:NST | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 91/40 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1991 | 2.1 |

| 91/58 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1991 | 2.1 |

| 92/123* | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1992 | 2.1 |

| 92/18 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1992 | 2.1 |

| 92/81 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1992 | 2.1 |

| 93/146 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1993 | 2.1 |

| 93/8 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1993 | 2.1 |

| 94/115 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/124 | Lineage III | B:4:− | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/154 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/163 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/167 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/209* | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/29 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 94/3 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 95/46* | Lineage III | B:4:P1.4 | New Zealand | 1995 | 2.1 |

| AK50 | Lineage III | B:15:P1.16 | Greece | 1992 | 2.1 |

| BZ138 | Lineage III | B:15:− | The Netherlands | 1982 | 2.1 |

| BZ198 | Lineage III | B:15:− | The Netherlands | 1986 | 2.1 |

| M101/93* | Lineage III | B:4:P1.14 | Iceland | 1993 | 2.1 |

| M211/93 | Lineage III | B:4:P1.14 | Iceland | 1993 | 2.1 |

| M40/94* | Lineage III | B | Chile | 1994 | 2.1 |

| N50/96* | Lineage III | B:19:P1.4,14 | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| 32 | Cluster A4 | Finland | 2.1 | ||

| 3906 | Cluster A4 | B:4:NST | China | 1977 | 2.1 |

| 8442 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | 2.1 | ||

| 13763 | Cluster A4 | B:ND | United States | 1987 | 2.1 |

| 11.93 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.10 | Argentina | 2.1 | |

| 280/94 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:NST | Argentina | 2.1 | |

| 502/91 | Cluster A4 | Cuba | 2.1 | ||

| 55/92 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.10 | Argentina | 2.1 | |

| 80/94 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.5,2 | Norway | 1994 | 2.1 |

| A021* | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | South Africa | 1989 | 2.1 |

| A040 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | South Africa | 1981 | 2.1 |

| AK15 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.10 | Greece | 2.1 | |

| AK2 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.10 | Greece | 2.1 | |

| B3843/79 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | Iceland | 2.1 | |

| B6116/77 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | Iceland | 2.1 | |

| BZ157* | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | The Netherlands | 1973 | 2.1 |

| BZ159 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | The Netherlands | 1975 | 2.1 |

| BZ163* | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.16 | The Netherlands | 1979 | 2.1 |

| G2136 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:NST | England | 1986 | 2.1 |

| M2* | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | Morocco | 2.1 | |

| M883 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | Israel | 1993 | 2.1 |

| M907 | Cluster A4 | B:2b:P1.2 | Israel | 1993 | 2.1 |

| M908* | Cluster A4 | B:2b:NST | Israel | 1993 | 2.1 |

| NG4/88 | Cluster A4 | B:4:NST | Norway | 1988 | 2.1 |

| NGE30 | Cluster A4 | B:4:P1.16 | Norway | 1988 | 2.1 |

| NGH41* | Cluster A4 | B:NT:NST | Norway | 1988 | 2.1 |

| SB22* | Cluster A4 | B | South Africa | 1990 | 2.1 |

Strains are ordered according to their genetic similarities based on the analysis of 14 gene loci encoding metabolic enzymes and by increasing number. The strains used in the bactericidal assay are indicated by an asterisk. Strains belonging to the ET-5 complex have been studied previously (39) and are reported here in order to compare them to strains belonging to other clonal complexes.

The size of tbpB gene was determined after PCR amplification on genomic DNA using OTG667 and OTG6689 primers. Strains presenting a tbpB gene of 1.8 or 2.1 kb are said to be of isotype I or isotype II, respectively.

E. coli constructs.

Antibiotic-resistant E. coli bacteria were selected on Luria broth plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. The different MBP translational fusions of TbpB used in this study are described in Table 2: the fusion proteins corresponding to the N terminus and the C terminus from N. meningitidis BZ83 were obtained after PCR amplification using primers 5′-CGGGATCCCTGGGCGGAGGCGGCAG-3′ and 5′-AAAACTGCAGATTATTCCAGTTTGTCTTTGGTTTTCG-3′ for the N-terminus construct and primers 5′-CGGGATCCAATGGCGCGGCGGCTTCAG-3′ and 5′-AAAACTGCAGATTATTGCACAGGCTTTTGGCG-3′ for the C-terminus construct. Convenient restriction sites were introduced (italicized letters) in order to clone these fragments in pMal-C2 (BamHI and PstI).

TABLE 2.

rTbpB regions from the four N. meningitidis prototype strains produced in fusion with MBP (42 kDa)

| Strain | Clonal group | rTbpB region | aa region in TbpBa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16B6 | ET-37 | Full length | 2–579 | 38 |

| M982 | NDb | Full length | 2–691 | 39 |

| N terminus | 2–351 | 39 | ||

| C terminus | 352–691 | 39 | ||

| BZ83 | ET-5 | Full length | 2–669 | 38 |

| N terminus | 2–328 | This study | ||

| C terminus | 329–669 | This study | ||

| 8680 | ET-5 | Full length | 2–677 | 38 |

aa, amino acid.

ND, not determined.

Characterization of tbpB genes by PCR amplification and restriction analysis of the amplified fragment.

N. meningitidis strains were grown on MHA plates (Difco). Extraction of DNA from each strain was performed with a rapid method using guanidium isothiocyanate (32). PCR amplifications of the tbpB genes were performed on genomic DNA using two primers, OTG 6687 and OTG 6689, described by Legrain et al. (22), under the following conditions: 25 cycles of denaturation of DNA at 94°C for 1 min, with annealing at 58°C for 2 min, and with extension at 72°C for 3 min. Each PCR was analyzed on 1% agarose gel, and the size of the tbpB gene was determined using a molecular weight marker, λHindIII (New England Biolabs). The amplified fragment was purified on a Qiaquick column (Qiagen) and then digested by using the enzymes HincII, AvaII, VspI, XhoI, and/or BamHI and MluI in six separate reactions according to the protocols specified by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). The restriction products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed, and the patterns were visually compared. A second PCR was carried out on genomic DNA primers P3 and P4 (39). Reactions were performed in a 100-μl volume containing 200 μM concentrations (each) of dCTP, dGTP, dATP, and dTTP (Pharmacia-LKB); 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Appligene). Amplifications were performed in a DNA thermocycler (Biometra; Trio-Thermobloc) programmed as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of consecutive denaturation (30 s, 95°C), annealing (30 s at 58°C), and DNA chain extension (1 min at 72°C). The size of the amplified fragment was determined after electrophoresis of PCR product on a 3% agarose gel.

Characterization of new tbpB genes by sequence analysis.

Fragments obtained after PCR with primers OTG6687 and OTG6689) were cloned in a pCR-Topo vector (Invitrogen) and automated cyclo-sequenced (Genome Express, Grenoble, France). When results were questionable or unexpected, the nucleotide sequence was confirmed by sequencing another clone obtained during another PCR. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were compared using the CLUSTAL W multialignment software from the Infobiogen package. A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (42) using the Grow Tree software from the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package.

Purification of meningococcal Tbp complexes, TbpB subunits, and recombinant TbpB or MBP-TbpB fusions.

The TbpA+B complexes were prepared as previously described from N. meningitidis B16B6 (B:2a:P1.2 with a TbpB with a mass of ca. 68 kDa), M982 (B:9:P1.9 with a TbpB with a mass of ca. 88 kDa), 8680 (B:15:P1.3 with a TbpB with a mass of ca. 82 kDa), and BZ83 (B:15:− with a TbpB with a mass of ca. 81 kDa) (10). Strains B16B6 and M982 were chosen as representative of the two major isotypes, I and II (38). Strains BZ83 and 8680 were chosen as representative of the two major variants of isotype II (39). Purified TbpB from strains B16B6 and M982 were obtained as previously described (24). The MBP-TbpB fusion molecules were produced by induction of recombinant E. coli cultures at log phase for 3 h with 0.3 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Appligene) and purified by using an amylose affinity column (36). The nonfusion rTbpB of strain B16B6 was purified from the membrane fraction of E. coli after cell disruption and centrifugation. Briefly, the membrane fraction was solubilized in buffer containing Zwittergent 3-14 (Calbiochem) and was chromatographed on Q-Sepharose columns. Fractions containing rTbpB were concentrated and loaded on an S-300 column for final polishing to remove endotoxins and degradation products. The purified protein was renatured and stored at <−45°C.

Preparation and characterization of mouse and rabbit antisera.

New Zealand White rabbits were immunized by the subcutaneous and intramuscular routes with three injections of native TbpB protein from strain B16B6 or TbpA+B complex from the four meningococcal strains (B16B6, M982, 8680, and BZ83) or with the eight MBP fusions. Briefly, 100 μg of protein were emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant and injected on days 0, 21, and 42. On day 57, the animals were sacrificed and the blood was collected. For bactericidal assays, rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were affinity purified on protein G-Sepharose 4FF columns (Pharmacia). The protein concentration of each IgG preparation was determined by a MicroBCA assay (Pierce).

Outbred CD1 mice (eight animals per group) were immunized by subcutaneous injections of 25 μg of B16B6 rTbpB purified from E. coli on days 1, 22, and 36 and were bled on day 43.

For characterization of the cross-reactivity of the different antisera used in this study, 1 μg of purified TbpA+B complex from strains B16B6, M982, BZ83, and 8680 was loaded onto an 8% acrylamide gel. After electrophoresis and electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes (44), the nitrocellulose strips obtained were incubated with specific antisera (1/500 or 1/1,000 dilution), followed by detection with a goat anti-rabbit serum conjugated to peroxidase (Zymed). For characterization of the specificity of sera raised to recombinant MBP-TbpB fusions, the same protocol was followed except that 10 μg of membrane fraction purified from N. meningitidis strains as described previously (40) was loaded onto a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel. The reaction was detected with a colorimetric (4-chloro-1-naphthol) substrate for peroxidase.

Serum bactericidal assay.

The bactericidal activity of purified rabbit IgG and mouse sera was tested as described earlier with slight modifications (40). Briefly, 50 μl of twofold serial dilutions of IgG solutions or serum were added to 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc) and incubated with 25 μl of an iron-starved meningococci suspension adjusted to 2 × 104 CFU/ml and 25 μl of baby rabbit complement. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, 20 μl of the mixture from each well was plated onto MHA plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in 10% CO2. The bactericidal titer of each serum or IgG preparation was expressed as the inverse of the last dilution of serum at which ≥50% killing was observed compared to the complement control. For complement-sensitive strains, the complement was adsorbed on formaldehyde-fixed bacteria (1010 CFU [3 ml of complement]) before being used.

RESULTS

Characterization of tbpB gene from serogroup B strains.

The 108 N. meningitidis strains of serogroup B analyzed were assigned to four major epidemiological complexes: ET-37 complex (22 strains); lineage III (29 strains), cluster A4 (27 strains), and ET-5 complex (30 strains). They corresponded to 6 different serotypes and 15 different serosubtypes and were recovered from 21 countries in various part of the world between 1966 and 1996 (Table 1). After PCR amplification with primers OTG6687 and OTG6689 of the tbpB gene of each isolate, a unique PCR product with an apparent size of approximately 1.8 kb (isotype I) or 2.1 kb (isotype II) was obtained (Table 1). Isotype I was exclusively found among the ET-37 complex strains. Of the 22 strains of the ET-37 complex strain, 1 displayed a tbpB gene corresponding to isotype II. In the three other clone complexes, all strains had a tbpB gene corresponding to isotype II (2.1 kb). Overall, 80.6% of the strains analyzed corresponded to isotype II and 19.4% were of isotype I.

To determine the presence of major tbpB gene variants previously identified (39), a PCR amplification with primers P3 and P4 was performed that allowed the production of a 5′ fragment corresponding to the first 850 nucleotides (nt) of the 2.1-kb tbpB gene. The size of the amplified product from each isolate was determined by comparison to those amplified from the known control strains M982, 8680, and BZ83 (Table 3). Among isotype II, the three major variants, M982, BZ83, and 8680, characterized by PCR products of 844, 772, and 805 nt, respectively, were represented by 43, 19, and 5 strains (Table 3). Among the ET-5 complex strains, a majority of BZ83-like strains were found (56%). Among the cluster A4 and lineage III strains, the M982 type was the most prevalent (89 and 96%, respectively), but BZ83-like strains were also found. Two 8680-like strains were also present in the cluster A4 collection. The only strain of the ET-37 complex that has been found to be of isotype II was M982-like.

TABLE 3.

Characterization of tbpB gene from serogroup B strains by PCR and restriction analysis

| Major type |

tbpB gene characteristics

|

No. of strainse (n)

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene sizea (kb) | Fragment sizeb (kb) | Restriction profilesc

|

Alleled | ET-5 (31) | LIII (29) | A4 (27) | ET-37 (22) | Total (108) | ||||||

| AvaII | HincII | VspI | XhoI | MluI | BamHI | |||||||||

| M982 | 2.1 | 844 | N | 3 | 2 | N | ND | ND | a-1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| N | 2 | N | N | ND | ND | a-2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 2 | N | ND | ND | a-3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| N | 8 | 2 | N | ND | ND | a-4 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 11 | |||

| N | 6 | N | N | ND | ND | a-5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 8 | |||

| N | 5 | N | N | ND | ND | a-6 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 0 | 30 | |||

| N | 7 | 2 | N | ND | ND | a-7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

| BZ83 | 2.1 | 772 | 1 | 3 | N | N | ND | ND | a-8 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 19 |

| 8680 | 2.1 | 805 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ND | ND | a-9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| N | 6 | 1 | 1 | ND | ND | a-10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ND | ND | a-11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| B16B6 | 1.8 | NF | 4 | 1 | N | N | 2 | 1 | a-12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| 5 | 1 | N | N | N | N | a-13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 4 | N | N | N | 1 | a-14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||

Determined as described in Table 1 (footnote b).

The fragment sizes indicated are those of the amplified fragment from genomic DNA using primers P3 and P4. The strains for which the tbpB nucleotide sequence were available have the exact size given. For the other strains, the sizes were determined after migration on a 3% agarose gel by comparison to the fragment of a prototype strain of each group (B16B6, M982, BZ83, and 8680). NF, no fragment.

Restriction patterns of the tbpB gene amplified by PCR on genomic DNA from the different strains with primers OTG6687 and OTG6689 were determined with AvaII, VspI, XhoI, HincII, MluI, and BamHI in separate reactions. The numbers 1 to 8 designate profiles, and the letter “N” designates a nondigested fragment. ND, not determined. The sizes (in nucleotides) of the fragments corresponding to each profile number are as follows: for AvaII, 1 (415, 477, and 1118), 2 (961 and 1109), 3 (445, 1507, and 82), 4 (1310 and 430), 5 (442, 839, and 471), and 6 (339, 577, 955, and 142); for HincII, 1 (110 and 630), 2 (1179 and 834), 3 (1224, 260, 273, and 319), 4 (1371 and 378), 5 (1191, 527, and 316), 6 (1242, 204, 276, and 80), 7 (1155, 260, 276, and 319), and 8 (1239, 186, 344, and 319); for VspI, 1 (263, 464, and 1286) and 2 (769 and 1307); for XhoI, 1 (474 and 1539); for MluI, 1 (474 and 1539) and 2 (110 and 630); and for BamHI, 1 (1417 and 593).

A name was given to each allele on the basis of its restriction pattern (a-1 to a-14).

The number of strains for which tbpB gene corresponds to each pattern is indicated for each clonal group studied for the total number of strains of the corresponding complex. Results for the ET-5 complex have been previously determined (39) and are included here for comparison with other clonal complexes. The total number of strains associated with each allele is also indicated.

To further characterize the tbpB gene of all the isolates tested, a restriction enzyme analysis was performed on the 2.1-kb PCR product by using the four enzymes AvaII, VspI, HincII, and XhoI. For isotype I, MluI and BamHI were also used. These enzymes were used since they have been shown to lead to specific patterns for the major variant strains described thus far (39). Table 3 shows that among all of the 108 strains studied, 14 different restriction patterns, referred to as alleles, were found (a-1 to a-14). Among the isotype I strains, three different patterns were found (a-12 to a-14), with 85.7% of the strains displaying the allele a-12 as the prototype strain B16B6. The M982-like tbpB genes were heterogeneous with seven different patterns (a-1 to a-7). Among all the isotype II strains studied, 72.7% corresponded to one of these seven alleles, 19% presented a unique pattern found among BZ83-like strains (allele a-8), and 5.6% displayed one of the three profiles found among 8680-like strains (a-9 to a-11). Overall, these results clearly demonstrated that the tbpB gene is not conserved among isotype I and isotype II of serogroup B strains. This was true for all four clonal complexes studied.

Sequence analyses of tbpB genes from serogroup B strains.

In order to precisely determine the degree of heterogeneity of the tbpB alleles of serogroup B strains corresponding to the two isotypes, the complete nucleotide sequences of tbpB of 10 new serogroup B strains were determined. The sequences were compared to each other and to all other known sequences of serogroup B tbpB alleles by multialignment using the CLUSTAL W program. In all, 24 full-length tbpB sequences (corresponding to 5 isotype I strains and 19 isotype II strains) were compared. The percentage of nucleotide divergence among isotype I strains varied from 1 to 33% (1 to 42% for the deduced amino acid sequences). Among isotype II strains, the level of heterogeneity of tbpB nucleotide sequences varied between 1 to 24% (1 to 33% for the corresponding amino acid sequences). The three major variant types among the isotype II strains were confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis. Strains belonging to the BZ83-like and 8680-like groups presented a low level of heterogeneity of tbpB nucleotide sequences. The BZ83-like strains differed from one another at 1 to 4% of their tbpB nucleotide sequences, confirming the PCR typing results and providing additional evidence that the BZ83 subtype is well conserved even among strains belonging to different complexes.

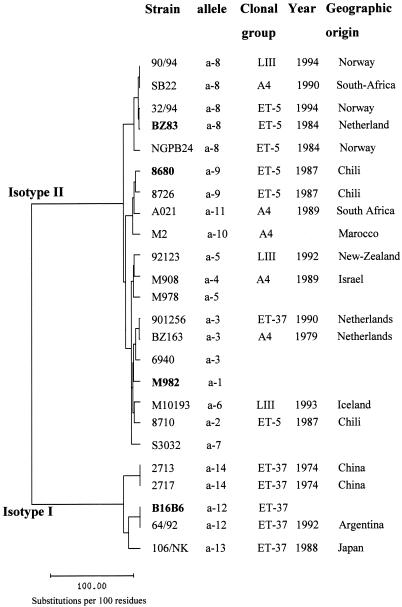

A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (45) (Fig. 1). In this figure, the segregation of the two isotypes appeared clearly. Among isotype II strains, the three major variants (M982, BZ83, and 8680) were also clearly separated. Strains belonging to different clonal groups can display the same allele; for example, strains belonging to three different clonal groups displayed allele a-8. However, alleles found among isotype I strains (alleles a-12, a-13, and a-14) were exclusively associated with strains belonging to the ET-37 complex. For some alleles, there seemed to be an association with the geographic origin of the strains: it was the case of allele a-9 (Chilean strains), a-3 (strains from The Netherlands), a-14 (Chinese strains), and a-8 (three of the five strains were isolated in Norway).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of tbpB nucleotide sequences of 24 strains of different clonal groups and geographic origins. The name of the strain, its tbpB allele, its geographic origin, and its clonal group are indicated, as is the year of its isolation. The prototype strain for each major variant is indicated in boldface. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (42). The EMBL accession numbers of the 10 new tbpB nucleotide sequences are AJ279554 (strain 2717), AJ279555 (strain 901256), AJ279556 (strain 64/92), AJ279557 (strain 90/94), AJ279558 (strain 92123), AJ279559 (strain M101/93), AJ279560 (strain AO21), AJ279561 (strain M2), and AJ279563 (SB22). The names and sources of other tbpB nucleotide sequences referred to in this study are strains B16B6 and M982 (21), strains BZ163 and BZ83 (20), strains 106, 2713, and NGPB24 (22), strains 6940, M978, and S3032 (27), and strains 8680, 8710, 32/94 and 8726 (39).

Antigenic relevance of the four major genetic tbpB variants.

The antigenic relevance of the four major variants was investigated. For this purpose, rabbit sera raised against the MBP fusion of the full-length TbpB from four meningococcal strains were produced (Table 2). Their cross-reactivities against the TbpB protein of the four strains B16B6, M982, BZ83, and 8680 were assessed by Western blotting, and their bactericidal activities against the four strains were determined (Table 4). The anti-MBP control sera did not react with any of the strains as expected. The four rTbpB fusions were shown to be immunogenic and induced TbpB-specific antibodies. All individual sera specifically recognized their homologous TbpB on the basis of a Western blotting on purified Tbp complex. TbpB-specific IgG purified from these sera displayed a bactericidal activity against their homologous strain. Cross-reactivity was detected for all sera when tested in a Western blot against the TbpB of the four strains. However, no cross-bactericidal activity was detected with an IgG preparation raised against an isotype I strain (B16B6) or isotype II strains (M982, BZ83, and 8680). Reciprocally, sera raised against rTbpB fusions from the three isotype II variants were not bactericidal against the isotype I strain B16B6. Sera raised against the rTbpB from isotype II strains displayed full cross-reactivity against the three isotype II strains on the basis of Western blot analysis. However, their cross-bactericidal activity toward the three nonhomologous strains was variable. For example, IgG raised to rTbpB-M982 killed preferentially strain BZ83 (titer of 64), while IgG raised to rTbpB-BZ83 killed only M982 (titer of 16). IgG raised to rTbpB from strain 8680 killed only the homologous strain, and an incomplete killing was observed with the other ET-5 complex strain (BZ83). In all cases, the level of killing was higher with the homologous strain. These results clearly showed that cross-reactivity of sera based on Western blot analysis was not predictive of their cross-bactericidal activity. Moreover, the M982 variant seemed to be antigenically closer to BZ83 than 8680.

TABLE 4.

Cross-bactericidal and Western blot reactivities of IgG raised against the MBP-TbpB fusions against the corresponding four meningococcal tbpB variants

| Protein used to raise antiserum | Tbp Western blot reactivitya

|

Bactericidal titerb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16B6 | M982 | BZ83 | 8680 | B16B6 | M982 | BZ83 | 8680 | |

| MBP alone | − | − | − | − | <4 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

| MBP-TbpB B16B6 (full length) | ++ | + | + | + | 128 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

| MBP-TbpB M982 (full length) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | <4 | 512 | 64 | 8 |

| MBP-TbpB BZ83 (full length) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | <4 | 16 | 512 | <4 |

| MBP-TbpB 8680 (full length) | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | <4 | <4 | [8] | 32 |

The TbpB Western blot reactivity was detected on purified Tbp complex prepared from strain B16B6, M982, BZ83, or 8680 (−, negative; + weak; ++, strong).

The bactericidal titer against homologous (in boldface) and heterologous strains was expressed as the reciprocal of the last IgG dilution in the presence of which 50% of the initial bacterial load had been killed. Brackets indicate incomplete killing, meaning that whatever the dilution of serum used, the bactericidal effect was not complete: that is, a few colonies remained with lower serum dilutions.

Contribution of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of TbpB in the induction of cross-reacting antibodies.

In an attempt to identify which part of the TbpB molecule was able to induce cross-reacting antibodies, rabbit sera were raised against the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of TbpB from strains M982 and BZ83 produced in fusion with MBP (Table 2). The corresponding IgG preparations were analyzed for their ability to induce cross-reacting antibodies by Western blot and bactericidal assays (Table 5). The results show that both TbpB domains from these two strains were immunogenic by themselves. As already observed with the anti-MBP-TbpB (FL), both domains induced antibodies that were cross-reactive in the Western blot assay with the heterologous TbpB from the Tbp complex purified from the three isotype II strains, even with the TbpB from isotype I strain B16B6. Again, however, no bactericidal activity was detected against this latter strain. Antibodies raised against the C-terminal domain of TbpB of strain M982 and strain BZ83 displayed a higher bactericidal activity than those raised against the corresponding N-terminal part of the protein. The antibodies raised to the C-terminal domain of TbpB from strain M982 were able to kill the strain BZ83, but the reverse was not observed. These results showed that both N- and C-terminal domains individually expressed from variant M982 in fusion with MBP presented epitopes commonly accessible on the surface of strains M982 and BZ83.

TABLE 5.

Contribution of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of TbpB in the induction of cross-reactive antibodies against the four meningococcal genetic tbpB variants

| Protein used to raise antiserum | Tbp Western blot reactivitya

|

Bactericidal titerb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16B6 | M982 | BZ83 | 8680 | B16B6 | M982 | BZ83 | 8680 | |

| MBP alone | − | − | − | − | <4 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

| MBP-N terminus from TbpB M982 | + | ++ | + | + | <4 | 32 | 8 | <4 |

| MBP-C terminus from TbpB M982 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | <4 | 512 | 256 | <4 |

| MBP-N terminus from TbpB BZ83 | + | ++ | ++ | + | <4 | <4 | 128 | <4 |

| MBP-C terminus from TbpB BZ83 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | <4 | <4 | 512 | <4 |

The TbpB Western blot reactivity was detected on purified Tbp complex prepared from strain B16B6, M982, BZ83, or 8680 (−, negative; +, weak; ++, strong).

The bactericidal titer against homologous (in boldface) and heterologous strains was expressed as the reciprocal of the last IgG dilution in the presence of which 50% of the initial bacterial load had been killed.

Complement-mediated bactericidal activity of specific antisera against a panel of 27 meningococcal strains.

A panel of 27 strains was chosen to represent the diversity observed in tbpB alleles. These strains are indicated by an asterisk in Table 1. The four major variants, B16B6, M982, 8680, and BZ83, and similar strains were all represented in the selected panel in the same proportion as in the complete collection (chi-square test, χ2 = 1.76, P = 0.62). All strains were able to bind horseradish peroxidase-hTf and expressed TbpB, and all of the strains can be killed by a rabbit antiserum raised against meningococcus whole cells, indicating that all of the tested strains were not resistant to killing (data not shown).

Table 6 summarizes complement-mediated bactericidal activities of the different IgG preparations. None of the sera raised against the TbpB protein or the Tbp complex from isotype I strain (B16B6) were able to kill any of the isotype II strains. The reverse was also true, confirming the segregation of the two isotypes on the basis of bacteridal activity of anti-Tbp sera. For strains belonging to the isotype I family, an IgG preparation raised against MBP-TbpB of strain B16B6 was able to kill three of the five isotype I strains tested. IgG raised against the native TbpB from this same strain was able to kill all five strains tested, as had the IgG raised to the Tbp complex. A pool of mouse anti-rTbpB serum alone killed four of the five strains. These results indicated that TbpB by itself was able to induce a high level of cross-bactericidal activity among the isotype I strains despite the heterogeneity observed in the TbpB amino acid sequences of two strains (106 and 2717) compared to the prototype TbpB from strain B16B6 and independently from the animal model used.

TABLE 6.

Bactericidal activity of anti-Tbp complex, native TbpB, and recombinant TbpB corresponding to the four major TbpB variants against a panel of 27 serogroup B strains in relation to the diversity of tbpB gene

| Type of strain tested (n)a | No. of strains killed by IgG preparations raised to Tbp complex, TbpB, or rTbpB from strainb:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B16B6

|

M982

|

BZ83

|

8680

|

|||||||||||

| Tbpc | TbpBd | MBP-TbpBe (FL) | rTbpBf | Tbpc | MBP-TbpBe

|

Tbpc | MBP-TbpBe

|

Tbpc | MBP-TbpBe (FL) | |||||

| FL | NT | CT | FL | NT | CT | |||||||||

| B16B6-like (5) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M982-like (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| BZ83-like (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 8680-like (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Total (27) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 |

The type of strain was defined according to the characteristics of the tbpB gene (see Table 3).

The results are expressed as the number of strains killed. A fourfold increase in the bactericidal titer, compared to preimmune serum or anti-MBP serum, was considered positive.

Tbp complex (TbpA+B) was purified from N. meningitidis strain B16B6, M982, BZ83, or 8680 and used to raise rabbit sera.

TbpB was purified from N. meningitidis B16B6 and used to raise rabbit serum.

rTbpB corresponding either to the full-length (FL) TbpB from strain B16B6, M982, BZ83, or 8680 or to the N-terminus (NT) or C-terminus (CT) part of TbpB from strains BZ83 and M982 were produced in fusion to MBP as described in Table 2 and were used to raise rabbit sera.

rTbpB from strain B16B6 was produced and purified from E. coli without MBP and used to raise eight mouse sera which were then pooled.

For strains belonging to the isotype II family, IgG preparations raised against MBP-TbpB full-length fusions of strains, M982, and BZ83 were able to kill, respectively, 10, 11, and 3 isotype II strains of the 22 tested. The corresponding killing scores obtained with the anti-Tbp complex were slightly higher (15, 14, and 6 strains killed, respectively). Three M982-like strains (BZ157, N50/96, and 901256) were not killed by any of the specific sera used in this study. However, their Tbp expression was demonstrated by a dot blot assay on whole cells, and their TbpB protein was detected by Western blotting. Moreover, they were killed by an anti-whole-cell control serum (data not shown). The strains classified as M982-like on the basis of genetic analysis were preferentially killed by anti-rTbpB or Tbp complex from strain M982, but some of them were also killed by anti-rTbpB or Tbp complex from strain BZ83. All of the BZ83-like strains were killed by anti-Tbp or rTbpB from the BZ83 strain but were also broadly killed by the corresponding M982 sera. 8680-like strains were preferentially killed by anti-Tbp complex or rTbpB from strain 8680. These results indicate that more than one TbpB protein is required to induce the broadest cross-bactericidal activity among isotype II strains. The TbpB from strains M982 and 8680 induced antibodies able to kill different type of strains, thus confirming the antigenic relevance of these genetic variants. However, the antigenic relevance of the BZ83 genetic variant was not demonstrated by these results.

The induction of cross-bactericidal antibodies by antisera raised against MBP-TbpB N- or C-domain fusions of strains M982 and BZ83 was also assessed (Table 6). The results indicated that the C-terminal part of rTbpB from strains M982 and BZ83 was able to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies among isotype II strains. Antibodies raised against the MBP-TbpB N domain from strain BZ83 were able to kill all five BZ83-like strains, as did the antibodies raised against the corresponding full-length molecule or against the Tbp complex. This result demonstrates that the N-terminal part of TbpB from strain BZ83 is highly immunogenic and able to induce by itself fully cross-bactericidal antibodies against BZ83-like strains. The level of cross-bactericidal activity obtained with an IgG preparation raised to the C-terminal part of TbpB from strain M982 was equivalent or higher than the one obtained with the corresponding full-length preparation (12 versus 10 strains killed of the 22 isotype II strains tested). These results demonstrate that the C-terminal part of TbpB protein was also able by itself to induce a large cross-bactericidal activity.

DISCUSSION

Ever since the identification of the two isotypes of the tbpB gene (38), their distribution among strains of N. meningitidis responsible for meningococcal disease has remained unclear. In this study, the distribution of the two tbpB isotypes was determined by analyzing 108 strains of the four major clonal complexes responsible for serogroup B disease. Isotype I strains were less represented than isotype II strains (19.4 versus 80.6%). This distribution is specific to the present collection corresponding exclusively to serogroup B strains, and one could expect that the proportions of the two isotypes would be different if serogroup A or C strains were included.

The extent of the diversity within the two isotypes was characterized, and 14 different alleles were identified based on restriction analysis of the tbpB gene. We demonstrated here that variability of tbpB was not restricted to isotype II, in contrast to what was thought previously on the basis of a study of a limited number of serogroup B strains (39). Among isotype I strains, the prevalent tbpB allele was a-12 and corresponded to the prototype strain B16B6, but two other alleles were identified (a-13 and a-14) for which the levels of nucleotide homology compared to a-12 were 58 and 75%, respectively. Despite this nucleotide sequence variability, antibodies raised against different preparations of TbpB from the prototype strain B16B6 showed cross-bactericidal activity (Table 6). In the present study, isotype I appears to be strictly associated with the ET-37 complex. This result is in agreement with the study of Brieske et al., who showed that all of the 19 ET-37 complex serogroup C strains studied belonged to isotype I, but in that study no variation of tbpB gene was detected (6). Despite the fact that the ET-37 complex has been described as a quite-homogeneous complex that comprises a limited number of variant clones (9, 45), it has been shown that strains from this complex were extremely variable with regard to their Opa proteins; 26 Opa proteins were identified by using monoclonal antibodies (45). This variation was described as resulting from recombinational reassortment, including duplication and import by horizontal genetic exchange (18). In the case of the tbpB allele, it is likely that recombination and/or horizontal genetic exchange events led to the appearance of the new variants described. Such events have been suggested in two previous studies of the tbpB gene of isotype II (20, 22). Horizontal and genetic exchange could result in identical or almost identical genes in unrelated meningococci; for example, strain 901256 from The Netherlands, which belongs to ET-37 complex, had the same tbpB allele as strain BZ163, also from The Netherlands, which belongs to cluster A4. Such an observation illustrates the concept of the global gene pool described by Maiden et al. (26).

This study demonstrates that the three major nucleotide tbpB gene variants (M982, BZ83, and 8680) initially detected among ET-5 complex strains (39) also exist among strains of isotype II belonging to other clonal complexes. Type M982-tbpB variants were largely represented among cluster A4 and lineage III strains and were variable at the nucleotide sequence level. Type BZ83-tbpB variants were preferentially represented among ET-5 complex strains but were also found in cluster A4 and lineage III and seemed to be very conserved. 8680-tbpB variants were not restricted to the ET-5 complex and were also found in cluster A4. The relevance of these variants was also shown on the basis of the ability of sera raised to the corresponding rTbpB to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies (Tables 4 and 5), since the number and the identities of the strains killed by the four anti-rTbpB sera were not the same (Table 6).

The results presented here provide further evidence that a recombinant TbpB is able to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies. This was previously shown with rTbpB from strain M982 against a smaller collection of isotype II strains (40). The present study allows us to extend the observation to isotype I strains by using rTbpB from strain B16B6. We also showed that the C-terminal part of the molecule was able to induce by itself cross-bactericidal antibodies against a large panel of strains, in addition to its ability to induce bactericidal antibodies against the homologous strain that has been previously reported (36). The TbpB C-terminal domain corresponds to the most conserved part of TbpB molecules (according to multialignment analysis performed with the CLUSTAL program, data not shown), and common C-terminal epitopes are most likely surface exposed on N. meningitidis strains.

This study highlights the caution with which cross-reacting antibodies need to be studied and analyzed; in this work, both Western blot and bactericidal assays were used, and they led to different results. It has been shown that antibodies to meningococcal Tbp complexes and to isolated proteins have been detected in both patients and carriers and that these antibodies were able to cross-react with TbpA or TbpB isolated from different meningococci (3, 11, 16, 19). However, in all cases, these conclusions were based on Western blot analysis or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) performed on purified Tbp complexes. Under these conditions, the cross-reactivity observed with antibodies by these techniques could not be predictive of their cross-functional activity. This is clearly shown in the present study, where cross-reactivity between the two proteins of the Tbp complex from isotype I strains and from isotype II strains was detected by Western blotting with specific antiserum, but antibodies raised to one or the other Tbp complex failed to induce bactericidal activity against the heterologous isotype strain. Using a different technique, Lehmann et al. showed that human serum from an N. meningitidis-infected patient was able to induce cross-opsonins against Tbp complex independently of the isotype of the strains. This conclusion was based on the use of beads coated with purified Tbp complex corresponding to the two isotypes, and under such conditions the epitopes may be distinct or may present different accessibilities than those exposed on live, viable meningococci (23).

The extent of cross-bactericidal activity observed with antisera raised to the rTbpB molecules was slightly lower than that observed with antisera raised to the TbpA+B complex (Table 6). At least three nonmutually exclusive hypotheses may explain this result: (i) TbpB retains a more native conformation when it is present within the complex rather than isolated, (ii) the presence of hTf in the purification scheme may help TbpB to adopt a conformation closer to the native one, or (iii) anti-TbpA antibodies directly contribute to the bactericidal activity of the antiserum. That hTf contact may help TbpB in refolding is indirectly supported by several studies which demonstrated that meningococcal transferrin binding is determined by independent specific recognition sites in hTf localized primarily in the C lobe but also in the N lobe (4, 5, 36, 37). The results of killing scores of isotype I strains with antisera to native TbpB from strain B16B6 purified on hTf (five strains killed out of five total) compared to the score obtained with the corresponding MBP fusion (three of five strains) (Table 6) may confirm this hypothesis. However, for pharmaceutical considerations, we chose not to purify the clinical-grade rTbpB on an hTf affinity column, and we developed an alternative scheme which gave intermediate results (four of five strains killed). The role of TbpA in the induction of protective antibodies is difficult to define, since no functional studies with separate TbpA and TbpB molecules as target antigens are available to date to give a definitive answer on the role of TbpA of N. meningitidis. However, a study of the protective capacity of P. haemolytica TbpA and TbpB in cattle showed that the best protection was observed in the group of animals immunized with both TbpA and TbpB. There was a high antibody response against TbpB and not against TbpA; no protection was detected in the group immunized with TbpA alone, and no antibody-mediated response was observed in this group. This led the authors of that study to suggest that TbpA contributed to protection through the induction of a non-antibody-mediated response (34).

Among isotype II strains, no single TbpB molecule was able to induce an antiserum displaying complete cross-bactericidal activity against all the strains. At least two of the three tbpB variants (M982 and 8680) seemed to be required to extend the level of cross-bactericidal activity, since different strains were killed depending on the variant of TbpB used to induce the antibodies.

Overall, using a large panel of strains, we demonstrated here that the two isotypes of tbpB are not equally represented among strains representative of serogroup B disease. We showed that four major variants of tbpB gene characterized at the nucleotide level are represented in the collection. The rTbpB proteins corresponding to these four variants were able to induce cross-bactericidal antibodies reacting with different strains from the panel studied. Since the data presented here were obtained with a collection of strains deliberately chosen to represent the largest possible diversity of TbpB and were carried out under stringent conditions, only four major variants were found. With this encouraging finding, we believe that an efficient, broadly cross-reactive rTbpB-based vaccine is feasible. Based on the results presented here, this vaccine should include at least two TbpB variants (B16B6 and M982); the addition of a third variant, if necessary, should preferably be variant 8680. Formulations and adjuvants are important aspects which will impact the immunogenicity of rTbpB. One could expect that these would modify the immunogenicity and potentially increase the cross-reactivity of rTbpB molecules. Our laboratory is currently investigating these issues in order to define the exact number of rTbpB molecules in the final product.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to D. R. Martin for kindly providing N. meningitidis strains from New Zealand, L. Lissolo for her constant support and critical reading of the manuscript, and F. Guinet and her team for providing rTbpB from strain B16B6. We also thank P. Lheritier and M. Dupuy for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ala'Aldeen D A, Borriello S P. The meningococcal transferrin-binding proteins 1 and 2 are both surface exposed and generate bactericidal antibodies capable of killing homologous and heterologous strains. Vaccine. 1996;14:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00136-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ala'Aldeen D A, Powell N B, Wall R A, Borriello S P. Localization of the meningococcal receptors for human transferrin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:751–759. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.751-759.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ala'Aldeen D A A, Stevenson P, Griffiths E, Gorringe A R, Irons L I, Robinson A, Hyde S, Borriello S P. Immune responses in humans and animals to meningococcal transferrin-binding proteins: implications for vaccine design. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2984–2990. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2984-2990.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcantara J, Schryvers A B. Transferrin binding protein two interacts with both the N-lobe and C-lobe of ovotransferrin. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:73–85. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton I C, Gorringe A R, Gorinsky B, Retzer M D, Schryvers A B, Joannou C L, Evans R W. Purified meningococcal transferrin-binding protein B interacts with a secondary, strain-specific, binding site in the N-terminal lobe of human transferrin. Biochem J. 1999;339(Pt. 1):143–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brieske N, Schenker M, Schnibbe T, Quentin-Millet M J, Achtman M. Human antibody responses to A and C capsular polysaccharides, IgA1 protease and transferrin-binding protein complex stimulated by infection with Neisseria meningitidis of subgroup IV-1 or ET-37 complex. Vaccine. 1999;17:731–744. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caugant D A. Population genetics and molecular epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis. APMIS. 1998;106:505–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caugant D A, Bovre K, Gaustad P, Bryn K, Holten E, Hoiby E A, Froholm L O. Multilocus genotypes determined by enzyme electrophoresis of Neisseria meningitidis isolated from patients with systemic disease. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:641–652. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-3-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caugant D A, Mocca L F, Frasch C E, Froholm L O, Zollinger W D, Selander R K. Genetic structure of Neisseria meningitidis populations in relation to serogroup, serotype, and outer membrane protein pattern. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2781–2792. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2781-2792.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danve B, Lissolo L, Mignon M, Dumas P, Colombani S, Schryvers A B, Quentin-Millet M J. Transferrin-binding proteins isolated from Neisseria meningitidis elicit protective and bactericidal antibodies in laboratory animals. Vaccine. 1993;11:1214–1220. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreiros C M, Ferron L, Criado M T. In vivo human immune response to transferrin-binding protein 2 and other iron-regulated proteins of Neisseria meningitidis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;8:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferron L, Ferreiros C M, Criado M T, Pintor M. Immunogenicity and antigenic heterogeneity of a human transferrin-binding protein in Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2887–2892. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2887-2892.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finne J, Leinonen M, Makela P H. Antigenic similarities between brain components and bacteria causing meningitis. Implications for vaccine development and pathogenesis. Lancet. 1983;ii:355–357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldschneider I, Gotschlich E C, Artenstein M S. Human immunity to the meningococcus. II. Development of natural immunity. J Exp Med. 1969;129:1327–1348. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.6.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez J A, Hernandez E, Criado M T, Ferreiros C M. Effect of adjuvants in the isotypes and bactericidal activity of antibodies against the transferrin-binding proteins of Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccine. 1998;16:1633–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorringe A R, Borrow R, Fox A J, Robinson A. Human antibody response to meningococcal transferrin binding proteins: evidence for vaccine potential. Vaccine. 1995;13:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths E, Stevenson P, Ray A. Antigenic and molecular heterogeneity of the transferrin-binding protein of Neisseria meningitidis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;57:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90408-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobbs M M, Malorny B, Prasad P, Morelli G, Kusecek B, Heckels J E, Cannon J G, Achtman M. Recombinational reassortment among opa genes from ET-37 complex Neisseria meningitidis isolates of diverse geographical origins. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt. 1):157–166. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson A S, Gorringe A R, Fox A J, Borrow R, Robinson A. Analysis of the human Ig isotype response to individual transferrin binding proteins A and B from Neisseria meningitidis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;19:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legrain M, Findeli A, Villeval D, Quentin-Millet M J, Jacobs E. Molecular characterization of hybrid Tbp2 proteins from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:159–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.364891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legrain M, Mazarin V, Irwin S W, Bouchon B, Quentin-Millet M J, Jacobs E, Schryvers A B. Cloning and characterization of Neisseria meningitidis genes encoding the transferrin-binding proteins Tbp1 and Tbp2. Gene. 1993;130:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legrain M, Rokbi B, Villeval D, Jacobs E. Characterization of genetic exchanges between various highly divergent tbpBs having occurred in Neisseria meningitidis. Gene. 1998;208:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann A K, Gorringe A R, Reddin K M, West K, Smith I, Halstensen A. Human opsonins induced during meningococcal disease recognize transferrin binding protein complexes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6526–6532. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6526-6532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lissolo L, Maitre-Wilmotte G, Dumas P, Mignon M, Danve B, Quentin-Millet M J. Evaluation of transferrin-binding protein 2 within the transferrin-binding protein complex as a potential antigen for future meningococcal vaccines. Infect Immun. 1995;63:884–890. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.884-890.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loosmore S M, Yang Y P, Coleman D C, Shortreed J M, England D M, Harkness R E, Chong P S, Klein M H. Cloning and expression of the Haemophilus influenzae transferrin receptor genes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:575–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.406943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maiden M C, Malorny B, Achtman M. A global gene pool in the neisseriae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1297–1298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.981457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazarin V, Rokbi B, Quentin-Millet M J. Diversity of the transferrin-binding protein Tbp2 of Neisseria meningitidis. Gene. 1995;158:145–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00151-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morelli G, Malorny B, Muller K, Seiler A, Wang J F, del Valle J, Achtman M. Clonal descent and microevolution of Neisseria meningitidis during 30 years of epidemic spread. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1047–1064. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5211882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers L E, Yang Y P, Du R P, Wang Q, Harkness R E, Schryvers A B, Klein M H, Loosmore S M. The transferrin binding protein B of Moraxella catarrhalis elicits bactericidal antibodies and is a potential vaccine antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4183–4192. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4183-4192.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olyhoek T, Crowe B A, Achtman M. Clonal population structure of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A isolated from epidemics and pandemics between 1915 and 1983. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:665–692. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peltola H. Meningococcal disease: still with us. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:71–91. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen J R. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poolman J T, Abdillahi H. Outer membrane protein serosubtyping of Neisseria meningitidis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7:291–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01963104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter A A, Schryvers A B, Ogunnariwo J A, Hutchins W A, Lo R Y, Watts T. Protective capacity of the Pasteurella haemolytica transferrin-binding proteins TbpA and TbpB in cattle. Microb Pathog. 1999;27:197–206. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renauld-Mongenie G, Latour M, Poncet D, Naville S, Quentin-Millet M J. Both the full-length and the N-terminal domain of the meningococcal transferrin-binding protein B discriminate between human iron-loaded and apo-transferrin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:171–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renauld-Mongenie G, Poncet D, von Olleschik-Elbheim L, Cournez T, Mignon M, Schmidt M A, Quentin-Millet M J. Identification of human transferrin-binding sites within meningococcal transferrin-binding protein B. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6400–6407. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6400-6407.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Retzer M D, Yu R H, Schryvers A B. Identification of sequences in human transferrin that bind to the bacterial receptor protein, transferrin-binding protein B. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:111–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokbi B, Mazarin V, Maitre-Wilmotte G, Quentin-Millet M J. Identification of two major families of transferrin receptors among Neisseria meningitidis strains based on antigenic and genomic features. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;110:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rokbi B, Mignon M, Caugant D A, Quentin-Millet M J. Heterogeneity of tbpB, the transferrin-binding protein B gene, among serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis strains of the ET-5 complex. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:522–529. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.522-529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rokbi B, Mignon M, Maitre-Wilmotte G, Lissolo L, Danve B, Caugant D A, Quentin-Millet M J. Evaluation of recombinant transferrin-binding protein B variants from Neisseria meningitidis for their ability to induce cross-reactive and bactericidal antibodies against a genetically diverse collection of serogroup B strains. Infect Immun. 1997;65:55–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.55-63.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossi-Campos A, Anderson C, Gerlach G F, Klashinsky S, Potter A A, Willson P J. Immunization of pigs against Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae with two recombinant protein preparations. Vaccine. 1992;10:512–518. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90349-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schryvers A B, Morris L J. Identification and characterization of the transferrin receptor from Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Bio/Technology. 1992;24:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J F, Caugant D A, Morelli G, Koumare B, Achtman M. Antigenic and epidemiologic properties of the ET-37 complex of Neisseria meningitidis. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1320–1329. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wedege E, Kolberg J, Delvig A, Hoiby E A, Holten E, Rosenqvist E, Caugant D A. Emergence of a new virulent clone within the electrophoretic type 5 complex of serogroup B meningococci in Norway. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:314–321. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.3.314-321.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]