Abstract

Purpose: To report a case of multifocal central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) mimicking Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease. Methods: A 42-year-old man was evaluated for an exudative retinal detachment (RD) with a presumptive diagnosis of VKH while being treated with corticosteroids. The examination showed subretinal fibrin deposition with a bullous, exudative, macula-involved RD in the left eye and a progressive decline in visual acuity (VA) to hand motions. Multimodal imaging showed multifocal hyperfluorescent leaks bilaterally by angiography, highly suggestive of CSCR exacerbated by corticosteroids. Results: After the multifocal CSCR diagnosis, the systemic corticosteroids were tapered and eventually discontinued. The patient was then managed with focal laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, and acetazolamide. The VA improved to 20/30 with complete resolution of the bullous RD at the 12-month follow-up. Conclusions: Extensive bullous RD with subretinal fibrin deposition is an infrequent manifestation of CSCR commonly associated with corticosteroid use that can mimic VKH. Thus, it is important to distinguish CSCR from VKH and the potential of combination therapy in managing chronic multifocal CSCR with a bullous RD.

Keywords: central serous chorioretinopathy, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada, corticosteroids, retinal detachment

Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR) is the fourth most common retinopathy after age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and branch retinal vein occlusion. 1 CSCR is a chorioretinal disorder characterized by the accumulation of fluid between the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Subretinal fibrin deposition is a rare manifestation of CSCR, and it is often considered an important indicator of severe/chronic CSCR. 2

Patients with CSCR are occasionally misdiagnosed as having Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH) or choroiditis given the similar clinical and imaging findings.2–6 Although the clinical presentation of the 2 diseases has some overlapping characteristics, CSCR and VKH vary in their pathophysiology. The pathogenesis of VKH is attributed to choroidal inflammation, while the pathogenesis of CSCR is attributed to a cortisol imbalance leading to choroidal hyperpermeability. 3 Failure to differentiate between CSCR and VKH can lead to the use of high-dose corticosteroids and progressive vision loss given that corticosteroids can exacerbate the progression of CSCR and contribute to the formation of subretinal fibrin.2,5

We present a case of atypical multifocal CSCR mimicking VKH. The patient’s symptoms worsened after being treated with corticosteroids for a presumptive diagnosis of VKH.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man was referred to our ophthalmology clinic for evaluation of an extensive retinal detachment (RD) suggestive of chronic CSCR or VKH syndrome. The patient was initially evaluated in November 2020 and was diagnosed with CSCR. At that time, examination showed moderate to marked subretinal fluid with bilateral RPE detachments (PEDs). The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 OD and 20/25 OS. At that time, the patient denied having headaches, tinnitus, or pain. He also denied hair or skin changes consistent with VKH.

Three months after his initial symptoms, the left eye was noted to have a moderate increase in subretinal fluid with increasing fibrin. Fluorescein angiography (FA) showed focal areas of late leakage without evidence of choroidal neovascularization. Eplerenone was started; however, the VA in the left eye continued to decrease with the development of an inferior RD. Because of the significant deterioration of the symptoms, the etiology was suspected to be inflammatory and a presumptive diagnosis of VKH disease was made. The patient was started on 60 mg prednisone daily. Despite being treated with corticosteroids, the inferior subretinal fluid continued to worsen. At that time, the patient was referred to our clinic for further evaluation.

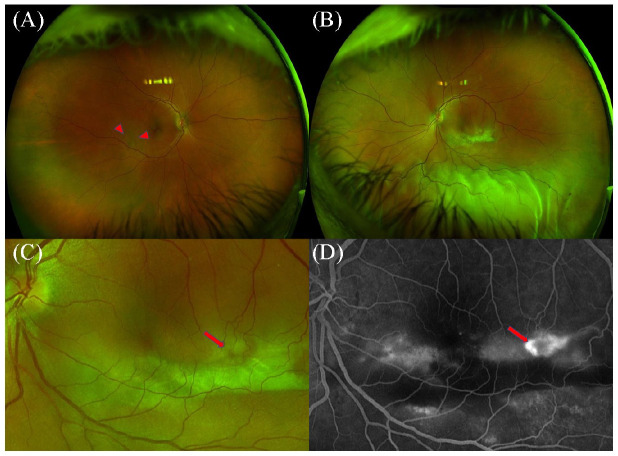

After referral, an additional detailed medical history was unremarkable for headache, hearing changes, tinnitus, and skin or hair changes consistent with VKH over the previous 6 months. On examination, the BCVA was 20/20 OD and 20/70 OS. No evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect was seen. A slitlamp examination showed a normal anterior chamber and vitreous in the right eye; the left eye had trace flare and pigment in the anterior chamber as well as trace pigment cell in the anterior vitreous. A fundus examination of the right eye showed PED with pigmentary changes descending inferiorly (Figure 1A). The left eye had a region of subretinal fibrosis inferior to the macula as well as an exudative inferior RD (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Ultra-widefield fundus photography of the right eye shows retinal pigment epithelium detachment with pigmentary changes (arrowheads) descending inferiorly (A). A large subretinal fibrinous lesion is noted inferior to the macula along with inferior bullous retinal detachment in the left eye (B). Arrow points to the dark spot within the subretinal lesion (C), which corresponds to a focal area of hyperfluorescence on fluorescein angiography (arrow) (D).

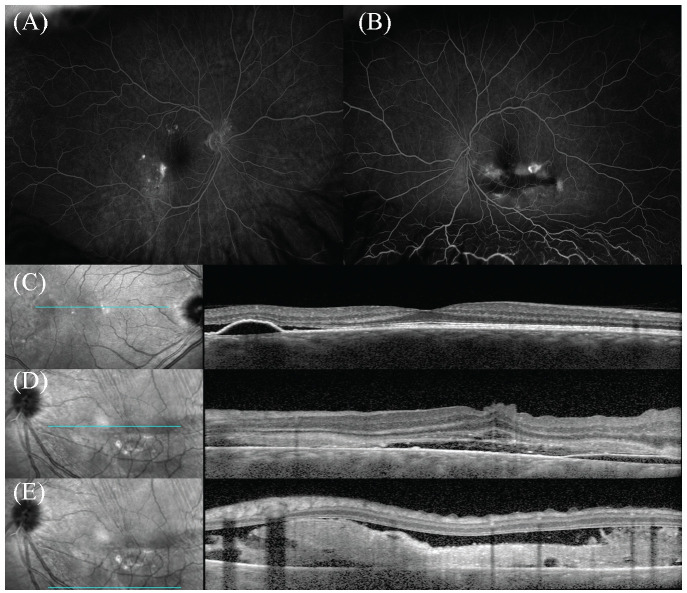

FA of the right eye showed multiple areas of hyperfluorescence with surrounding leakage temporal and superior to the macula (Figure 2A). FA of the left eye showed multiple pinpoint hyperfluorescent leakages with pooling in the late phase descending inferiorly (Figure 2B). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye showed serous PED with associated subretinal fluid (Figure 2C). The left eye showed serous PED with significant fluid and internal limiting membrane folds (Figure 2D). An inferior B-scan also showed significant fibrin deposits associated with significant subretinal fluid (Figure 2D). Laboratory testing, which included angiotensin-converting enzyme, lysozyme, antinuclear antibody, Treponema pallidum immunoglobulin-G antibody, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and QuantiFERON-TB Gold, was unremarkable.

Figure 2.

(A) Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye shows multiple late staining lesions with surrounding leakage temporal and superior to the macula. (B) FA of the left eye shows multiple pinpoint leakage with pooling inferiorly. (C) Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye shows serous retinal pigment epithelium detachment (PED) with associated subretinal fluid. (D) Left eye shows internal limiting membrane folds and serous PED with significant subretinal fluid. (E) Inferior B-scan of the left eye OCT shows significant fibrin deposit associated with significant subretinal fluid.

Because of the worsening symptoms and absence of clear evidence of intraocular inflammation, the prednisone was tapered and eventually discontinued over a 3-week period while the RD was closely monitored. During this time, the VA worsened to finger counting with continued fluid in the macula. Given the worsening VA and multiple pinpoint areas of hyperfluorescence with leakage into the macula, focal laser photocoagulation was initiated and the patient was started on acetazolamide (Diamox extended-release capsules, Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc) 500 mg twice a day.

In the subsequent 2 weeks, the patient had another focal laser photocoagulation session and 1 photodynamic therapy (PDT) session. For the PDT, the patient received intravenous infusion of verteporfin (6 mg/m2); the PDT settings were 50 J/cm2, 83 seconds, and 600 mW/cm2 with a spot size of 5000 µm. At subsequent visits, the subretinal fluid and VA gradually improved and the acetazolamide was decreased to 500 mg once a day and subsequently discontinued.

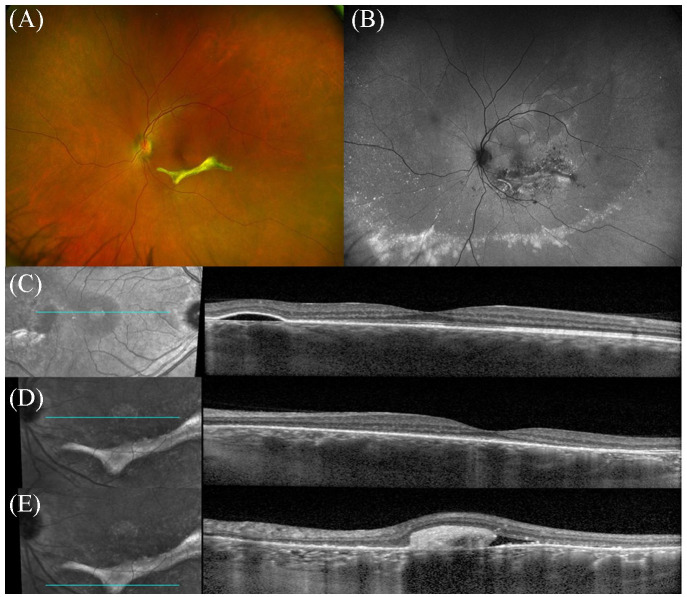

Seven months after the initiation of laser photocoagulation, the VA remained 20/20 OD and improved to 20/30 OS. A fundus examination of the left eye showed resolution of the exudative RD with a region of subretinal fibrosis in the inferior macula (Figure 3A). The right eye remained unchanged. Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye showed hypoautofluorescence surrounding the curvilinear area of subretinal fibrosis, indicative of pigment epithelium changes. A hyperautofluorescent band was also observed peripherally (Figure 3B). OCT of the right eye showed PED without the associated subretinal fluid (Figure 3C). OCT of the left eye showed resolution of central subretinal fluid (Figure 3D) with subretinal fibrosis inferior to the fovea (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

(A) Ultra-widefield fundus photography of the left eye still shows a well-demarcated area of subretinal fibrosis inferior the fovea with resolution of the exudative retinal. (B) Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye shows significant pigmentary changes around the fibrinous lesion as well as inferior hyperfluorescent deposits. (D and E) OCT of the left eye shows resolution of central subretinal fluid, although mild subretinal fluid associated with the subretinal fibrosis can be observed. (C) OCT of the right eye shows pigment epithelium detachment without associated subretinal fluid.

Twelve months after the patient’s initial evaluation, the VA remained 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. The examination and multimodal imaging findings were stable.

Conclusions

Extensive, bullous RD with subretinal fibrin deposition in the macula is a rare manifestation of CSCR. Because CSCR has features similar to those of severe VKH syndrome, these patients are occasionally misdiagnosed as having posterior uveitis, leading to corticosteroid initiation or escalation with subsequent exacerbation of symptoms.

Parchand et al 2 and Yannuzzi et al 7 reported that the presence of a dark spot in the subretinal fibrinous lesion might be helpful in differentiating the severe/chronic form of CSCR from VKH and other forms of posterior uveitis. These dark spots were hyperfluorescent on the corresponding FA and correlated with a well-demarcated hyperreflective subretinal lesion on the corresponding OCT. Our patient had a similar finding on fundus photography and fluorescein angiography. This suggests the importance of this characteristic in differentiating severe fibrinous CSCR from VKH and other forms of posterior uveitis. Furthermore, a history of constitutional symptoms, including headache, meningeal symptoms, and ocular symptoms suggestive of uveitis (eg, photophobia, redness), would be suggestive of VKH rather than CSCR.

Chronic CSCR is defined as having persistent subretinal fluid for at least 3 to 6 months. 8 Although most cases of acute CSCR resolve without intervention, chronic CSCR has been suggested to lead to irreversible vision loss resulting from the persistent subretinal fluid.

In the management of chronic CSCR, half-dose PDT has been shown to be effective for VA improvement and resolution of subretinal fluid over the short term and long term.9–12 Focal laser photocoagulation was also found to be effective in managing chronic CSCR; however, because of the potential for CNV development and scotomata, focal laser photocoagulation may be less desirable for chronic CSCR. 8

Mineralocorticoid antagonism has been shown to be an effective treatment for chronic CSCR. Spironolactone, which has a high affinity for the aldosterone receptor, is reported to be effective in managing chronic CSCR, while eplerenone, also a mineralocorticoid antagonist, has shown inconsistent efficacy in treating chronic CSCR.13–19 A recent randomized clinical trial, the VICI study, did not show eplerenone to be effective when compared with a placebo in treating patients with chronic CSCR. 17

Our patient was initially treated with eplerenone; however, his symptoms did not improve significantly. Subsequently, he was treated with a combination of focal laser photocoagulation, PDT, and acetazolamide, with gradual improvement over time. Although acetazolamide has not consistently shown to be effective in clinical trials, it has been used off-label to treat CSCR by inhibiting carbonic anhydrase IV in the RPE, with improved resorption of subretinal fluid. 20

Given that individual therapies including, acetazolamide, photocoagulation, and PDT, have shown benefits in previous studies, it is possible that the patient could have improved with monotherapy. However, the patient’s severe vision loss and extensive fluid led to our consideration of a combination approach given the different mechanisms of therapeutic action. Our patient’s course suggests that this combination of treatment modalities was effective in this case of severe/chronic CSCR, leading to a substantial improvement in VA from a nadir of hand motions to the 20/30 level.

In conclusion, we describe a patient who presented with an atypical case of CSCR with subretinal fibrinous deposition and bullous RD, likely exacerbated by high-dose systemic corticosteroid for a presumptive diagnosis of VKH. The case underlines the potential importance of recognizing severe multifocal CSCR and distinguishing the condition from posterior uveitis as well as the potential role for combination therapy in treating chronic/severe CSCR.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection and evaluation of all protected patient health information was performed in a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant manner.

Statement of Informed Consent: The written informed consent for patient information was not sought for the case report because all patient identifier information was not reported.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 EY029594 (SY). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Funding support is also provided by the Macula Society Retina Research Foundation Cox Family Grant, Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Mallinckrodt Foundation Young Investigator Award, and the Stanley M. Truhlsen Family Foundation, Inc.

References

- 1.Wang M, Munch IC, Hasler PW, Prunte C, Larsen M.Central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(2):126-145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parchand S, Gupta V, Gupta A, Dogra MR, Singh R, Sharma A.Dark spot in fibrinous central serous chorioretinopathy masquerading choroiditis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(3):201-206. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2013.765015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal K, Agarwal A, Deokar A, et al. Distinguishing features of acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and acute central serous chorioretinopathy on optical coherence tomography angiography and en face optical coherence tomography imaging. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2017;7(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12348-016-0122-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cebeci Z, Oray M, Bayraktar S, Tugal-Tutkun I, Kir N.Atypical central serous chorioretinopathy. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017;47(4):238-242. doi: 10.4274/tjo.38039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papadia M, Herbort CP.Central serous chorioretinopathy mistaken for tuberculous choroiditis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6(4):334-337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin WB, Kim MK, Lee CS, Lee SC, Kim H.Comparison of the clinical manifestations between acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and acute bilateral central serous chorioretinopathy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2015;29(6):389-395. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2015.29.6.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yannuzzi NA, Mrejen S, Capuano V, Bhavsar KV, Querques G, Freund KB.A central hyporeflective subretinal lucency correlates with a region of focal leakage on fluorescein angiography in eyes with central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46(8):832-836. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20150909-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanumunthadu D, Tan ACS, Singh SR, Sahu NK, Chhablani J.Management of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(12):1704-1714. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1077_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan WM, Lai TY, Lai RY, Liu DT, Lam DS.Half-dose verteporfin photodynamic therapy for acute central serous chorioretinopathy: one-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(10):1756-1765. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle J, Gupta B, Tahir I.Long term outcomes for patients treated with half-fluence photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a case series. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(2):333-336. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2018.02.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hua L, Lin B, Hong J, et al. Clinical research on one-third dose verteporfin photodynamic therapy in the treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(2):278-284. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201801_14169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim JI, Glassman AR, Aiello LP, et al. Collaborative retrospective macula society study of photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1073-1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet E, Beydoun T, Rothschild PR, et al. Spironolactone for nonresolving central serous chorioretinopathy: a randomized controlled crossover study. Retina. 2015;35(12):2505-2515. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herold TR, Rist K, Priglinger SG, Ulbig MW, Wolf A.Long-term results and recurrence rates after spironolactone treatment in non-resolving central serous chorio-retinopathy (CSCR). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255(2):221-229. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3436-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DY, Lee JY, Lee EK, Kim JY.Comparison of visual/anatomical outcomes and recurrence rate between oral spironolactone and photodynamic therapy for nonresolving central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2020;40(6):1191-1199. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Lee SC, Kim H, Lee CS.Comparison of short-term efficacy between oral spironolactone treatment and photodynamic therapy for the treatment of nonresolving central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2019;39(1):127-133. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotery A, Sivaprasad S, O’Connell A, et al. Eplerenone for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy in patients with active, previously untreated disease for more than 4 months (VICI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10220):294-303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32981-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahimy E, Pitcher JD, 3rd, Hsu J, et al. A randomized double-blind placebo-control pilot study of eplerenone for the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy (ecselsior). Retina. 2018;38(5):962-969. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz R, Habot-Wilner Z, Martinez MR, et al. Eplerenone for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy-a randomized controlled prospective study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(7):e610-e618. doi: 10.1111/aos.13491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fusi-Rubiano W, Saedon H, Patel V, Yang YC.Oral medications for central serous chorioretinopathy: a literature review. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(5):809-824. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0568-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]