Abstract

The clinical usefulness MRI biomarkers for aging and dementia studies relies on precise brain morphological measurements; however, scanner and/or protocol variations may introduce noise or bias. One approach to address this is post-acquisition scan harmonization. In this work, we evaluate deep learning (neural style transfer, CycleGAN and CGAN), histogram matching, and statistical (ComBat and LongComBat) methods. Participants who had been scanned on both GE and Siemens scanners (cross-sectional participants, known as Crossover (), and longitudinally scanned participants on both scanners ()) were used. The goal was to match GE MPRAGE (T1-weighted) scans to Siemens improved resolution MPRAGE scans. Harmonization was performed on raw native and preprocessed (resampled, affine transformed to template space) scans. Cortical thicknesses were measured using FreeSurfer (v.7.1.1). Distributions were checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Intra-class correlation (ICC) was used to assess the degree of agreement in the Crossover datasets and annualized percent change in cor tical thickness was calculated to evaluate the Longitudinal datasets. Prior to harmonization, the least agreement was found at the frontal pole () for the raw native scans, and at caudal anterior cingulate (0.76) and frontal pole (0.54) for the preprocessed scans. Harmonization with NST, CycleGAN, and HM improved the ICCs of the preprocessed scans at the caudal anterior cingulate (> 0.81) and frontal poles (> 0.67). In the Longitudina raw native scans, over- and under-estimations of cortical thickness were observed due to the changing of the scanners. ComBat matched the cortical thickness distributions throughout but was not able to increase the ICCs or remove the effects of scanner changeover in the Longitudinal datasets. CycleGAN and NST performed slightly better to address the cortical thickness variations between scanner change. However, none of the methods succeeded in harmonizing the Longitudinal dataset. CGAN was the worst performer for both datasets. In conclusion the performance of the methods was overall similar and region dependent. Future research is needed to improve the existing approaches since none of them outperformed each other in terms of harmonizing the datasets at al ROIs. The findings of this study establish framework for future research into the scan harmonization problem.

Keywords: Deep learning, Structural MRI, Scan harmonization

1. Introduction

Biomarkers measured from structural magnetic resonance images (MRI) in aging and dementia studies provide clinically relevant information. The repeatability and accuracy of these biomarkers can be negatively affected by differences in acquisition protocols in multicenter studies, due to variation in vendor, scanner hardware or software within cross-sectional research studies, or any of the aforementioned changes in longitudinal studies (Hedges et al., 2022). As technology advances, newer and improved scanner hardware and software from various vendors continually replace older methods, further increasing data heterogeneity. Although careful acquisition protocol design, referred to as “standardization ”, can minimize the effects of scanner variation on brain measures, the effect of the scan acquisition (due to scanner hardware/software and protocol change) introduces significant variability across quantitative measurements in both cross-sectional multi-center comparison and longitudinal disease progression studies (Hedges et al., 2022; Wittens et al., 2021). Therefore, post-acquisition harmonization methods are important to ensure that biomarkers are repeatable and reliable for accurate disease diagnosis and prognosis.

Harmonization is a broad term used to describe the process of translating, removing, adapting, and/or altering domain-specific features of either source scan and/or target or reference scan to match each other. A source scan refers to the scan that we aim to harmonize while the reference scan is the one whose properties are extracted and applied onto the source scan. Reference scans are sometimes called target scans. There are two broad classes of harmonization methods. First, harmonization can be applied to source scans by using image translation techniques (i.e., learning the mapping between the source to target image) such as histogram matching and deep learning-based methods. Second, harmonization can be applied to biomarkers extracted from both source and reference scans where scanner-related effects are removed either from both measurements (Johnson et al., 2007) or just from the source scan measurements (Luo et al., 2010). The latter type of harmonization most commonly employs statistics-based methods (Johnson et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2015). After performing a harmonization task, the resulting images or biomarkers should ideally be indistinguishable to that of the reference scans in terms of image quality, signal-to-noise ratio, contrast, texture, and resolution.

From the first class of methods that are mainly focused on deep learning (DL), scan data harmonization can be considered a domain adaptation (DA) image-to-image translation (IIT) problem (Isola et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2017). In DA IIT methods, the training data can be either paired (Isola et al., 2016), i.e., the reference and source scans are obtained from the same participant which are then co-registered, or the training data can be unpaired (Zhu et al., 2017), i.e., the source and reference scans are obtained from different participants and do not need to be co-registered. Previous deep learning-based studies on translation of structural MRIs leveraged some form of generative adversarial computation in their methods (Bashyam et al., 2021; Dinsdale et al., 2021; Liu Mengting and Maiti, 2021). For instance, a study by Dinsdale et al. implemented a DA technique in order to perform tasks such as segmentation or prediction tasks by adversarial removing of the domain specific features (Dinsdale et al., 2021). Another study by Liu et al. implemented a style-encoding generative adversarial network (GAN) architecture whereby they trained a single generator to translate a source scan in the style of a reference scan and then validated the translated style using an encoder network on the generated images (Liu Mengting and Maiti, 2021). Histogram matching or normalization, which has been traditionally used to harmonize the image intensities between two scans, is often used as the control technique against which the performance of newer techniques is compared (Choi et al., 2018; He et al., 2021, 2020; Zuo et al., 2021). Notably, most studies trained their models using 2-D slice inputs due to the high computational cost of feeding a network full-sized 3-D MRI stacks per thousands of scans (Choi et al., 2018; He et al., 2021, 2020; Zuo et al., 2021).

Among the second class of methods presented in this study, the most commonly used statistical harmonization method for brain imaging is ComBat, which was initially designed for removing batch effects in genomics (Johnson et al., 2007), and was recently adapted for harmonizing structural MRIs (Fortin et al., 2018). There has been an increased interest in applying ComBat or its variants, primarily due to its post-acquisition advantages of working only on the extracted features. However, given the availability of multiple methods for scanner harmonization, the optimal method for imaging biomarker measurements across scanners has not been straightforward. Our overall goal was to evaluate the performances of state-of-the art scan harmonization methods. Specifically, our aims were (1) to compare the performances of neural style transfer (NST), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and statistics-based cross-scanner harmonization techniques, and (2) to evaluate the effect of scanner change on quantitative measurements before and after harmonization by each of the methods using scans from the same participants who were scanned cross-sectionally or longitudinally.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of participants

In this study, we selected participants who had undergone 3T MRI scans with GE (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) and Siemens (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) scanners in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) and Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). The MCSA is an epidemiological cohort designed to investigate the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia among the residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota (Petersen et al., 2010). The ADRC is a longitudinal study of a clinical sample. Age, sex, and clinical diagnoses at the time of the MRI scan were utilized as covariates in this study. These studies were reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center institutional review boards. All participants were provided with written information, and written consent was collected from all participants/caregivers.

All the sMRI scans used in this study were collected from MCSA and ADRC studies between August 2015 and September 2021. Both studies utilized GE HDx and DISCOVERY scanners with identical protocols from 2015 to Nov 2017 and then switched to Siemens Prisma scanners in December 2017. We divided all available data from MCSA and ADRC scans into three datasets, namely Cross-sectional, Longitudinal, and Crossover. The first and largest Cross-sectional dataset () included participants who at one time had undergone either GE or Siemens scanning (Table 1). The second dataset was the Longitudinal dataset () where each participant had both GE and Siemens scans at different time points (TPs) (Table 1). The inclusion criteria for the longitudinal dataset were all participants from MCSA and ADRC who had at least two scans with GE followed by at least two scans with Siemens. The third, which we refer to as the “Crossover cohort ” consisted of participants who were recruited specifically to investigate the GE to Siemens scanner change. This cohort was made up of a cross-sectional dataset where the Crossover scans of the same participants () taken with GE and Siemens scanners close in time, typically on the same day.

Table 1.

A summary of the data presented in this study. The data was partitioned into training/validation and test sets for neural style transfer (NST), Conditional generative adversarial networks (CGANs), and CycleGANs. Histogram matching, ComBat and LongComBat only used the testing data for the scan harmonization.

| Methods | Training data |

Testing data |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE | Siemens | GE | Siemens | GE | Siemens | |

| Histogram matching | – | – | 227 | 227 | 113 | 113 |

| Neural style transfer | 925, 231 ‡ | 925, 231 ‡ | 227 | 227 | 113 | 113 |

| CGAN-1 † | 227 | 227 | – | – | 113 | 113 |

| CGAN-2 † | 113 | 113 | 227 | 227 | – | – |

| CycleGAN | 1156 | 1156 | 227 | 227 | 113 | 113 |

| ComBat | – | – | 227 | 227 | 113 | 113 |

| LongComBat | – | – | 227 | 227 | 113 | 113 |

Crossover subjects (n = 113): age (68 ± 17 years), 56% male, 66% cognitively unimpaired (CU).

Longitudinal subjects (n = 227): age on GE scans (67 ± 8 years), 64% male, 48% CU, follow-up time (1.6 ± 0.9 years); age on Siemens scans (73 ± 9 years), 64% male, 35% CU, follow-up time (1.5 ± 0.5 years); transition follow-up time (4.3 ± 2.8 years).

Cross-sectional Training Dataset (n = 1156): GE scans - age (72 ± 12 years), 54% male, 69% CU; Siemens scans - age (69 ± 12 years), 56% male, 65% CU.

Train, validate partitions of the cross-sectional training data split to 70%, 30% respectively.

CGAN was trained twice varying the training and testing data between the longitudinal and crossover datasets.

2.1.1. MRI acquisition and preprocessing

The T1-weighted MRI from both scanners were acquired using standard structural magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequences as published previously (Schwarz et al., 2016). The raw native GE and Siemens scans had resolutions of and , respectively. For the deep learning methods, preprocessing was conducted to resample the scans to the same voxel size of with a matrix size of using B-spline interpolation, B1 bias correction, affine transformation to the same template space. While CycleGAN, CGAN, NST and HM were evaluated on the preprocessed scans, ComBat and LongComBat were assessed on both the raw native and preprocessed scans.

2.1.2. Training and test datasets

The training set consisted of 2312 Cross-sectional participants (GE: , 72 (12) years, Siemens: , 69 (12) years) scans where 56% were male and 65% were cognitively unimpaired (CU). Equal number of participants were chosen to have a class balanced dataset for training our models. The neural style transfer’s classifier model (detailed below in Section 2.3.3) and the CycleGAN were trained using this training set (Table 1). The test sets were used as training sets for CGAN since it is a paired IIT DA method (detailed below in Section 2.3.3) (Table 1).

The test set consisted of the Crossover and Longitudinal datasets (Table 1). The Crossover dataset consisted of scans of the same participants that had undergone Siemens (, 68 (17) years, 44% Female) and GE (, 68 (17) years) scans where 66% were CU.

The Longitudinal dataset (GE (, 67 (8) years, 36% Female) and Siemens (, 73 (9) years, 36% Female) and 30% were CU) consisted of the same participants who had at least 2 visits follow-up visits where 79, 19 and 3 participants had 4, 6 and 8 followup respectively. The GE MRI scanners were the older scanners used earlier in the MCSA and ADRC studies; hence, all the baseline time points were always scanned by GE, while the subsequent time points were always scanned by the Siemens MRI scanners. The average followup time between the GE scanners, the scanner change, and the Siemens scanners was 1.6 years, 4.3 years, and 1.5 years, respectively.

2.2. Measuring regional cortical thickness using FreeSurfer

Cortical thickness and surface area were measured by FreeSurfer (version 7.1.1) for 34 regions of interest (ROIs) using the Desikan-Killiany atlas (Supplementary Figure 1). FreeSurfer was applied as a cross-sectional pipeline when running it for the Crossover dataset and as longitudinal pipeline when the Longitudinal dataset was used. Then, the CTh was first weighted by its surface area and then the average of the right and left hemispheres was taken to give the final ROI. We also grouped the individual ROIs into six meta-ROIs by taking their averages: Medial Temporal, Temporal, Frontal, Occipital, Parietal and Cingulate (Supplementary Figure 1). The meta-ROIs for the image-based methods presented in this study were grouped after harmonization, whereas for the statistics-based methods, averaging was performed both before and after harmonization to assess their robustness in removing scanner effects from the meta-ROIs.

2.2.1. Annualized percent change in cortical thickness for the longitudinal dataset

We calculated the annualized percent change in cortical thickness between two time points ( and ) as the percent change in CTh divided by , which is the difference between the two time points normalized by the total number of days in a year (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

The annualized percent change in CTh was determined between baseline (TP 1) to time point 2 (TP 2) and between TP 2 to TP 3, i.e., between the scanner change. Before the scanner change, the unharmonized data at TP1 and TP2 were either the preprocessed or raw native GE scans, while TP3 and TP4 were the corresponding Siemens scans. After harmonization, TP1 and TP2 were the harmonized GE scans by the various methods while the later time points were always the unharmonized Siemens scans. Four time points were chosen due to the majority of the participants having exactly 4 visits (2 GE and 2 Siemens) and to be able to have a fair comparison of the annualized percent change in CTh without biasing the number of participants towards a time point ( participants per TP).

2.3. Scanner harmonization methods

The harmonization methods presented in this study can be divided into three: statistics-based, basic image processing, and deep learning-based. The first category includes ComBat and LongComBat which are statistics-based harmonization method, and the second group is histogram matching which represents basic image processing. The last category consists of NST, CGAN and CycleGAN.

2.3.1. Statistics-based scanner harmonization methods

2.3.1.1. ComBat.

ComBat is a linear regression method which performs scale adjustment to remove batch effects on measured data collected from different sources but describing the same physical property (Johnson et al., 2007). Unlike its predecessors, such as the location/scaling (L/S) method, it uses empirical Bayes estimation for smaller sized data (Johnson et al., 2007). Fortin et al. adapted the original implementation by Johnson et al. for cortical thickness harmonization (Fortin et al., 2018). In this study, ComBat was tasked with harmonizing the FreeSurfer cortical thickness values that were measured from scans of participants using GE and Siemens where from each participant cortical thickness was extracted from 34 ROIs . ComBat models the additive and multiplicative effects caused by the scanner differences affecting the feature values (Fortin et al., 2018) (Eq. (2)). In Eq. (2), represents the error term, which is assumed to be have Normal distribution with mean 0 and variance (Fortin et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2007).

| (2) |

The harmonized variable is then calculated by estimating the mean cortical thickness from the reference scanner, as well as the additive and multiplicative scanner related effects where the term is a matrix of covariates (Fortin et al., 2018) (Eq. (3)). For more details please refer to (Fortin et al., 2018).

| (3) |

There are several implementations of ComBat; however, here we tested its original version as adapted by Fortin et al., called neuroCombat (Fortin et al., 2018). Additionally, we also implemented a version called LongComBat on our Longitudinal dataset (Beer et al., 2020). Unlike the original implementation, LongComBat considers the followup time points between scans for each batch in the error estimation. In our study we used age, sex, and diagnosis as covariates in both ComBat and LongComBat. We applied the original ComBat version on both the Crossover and Longitudinal datasets, while LongComBat was applied only to the Longitudinal dataset. Pre- and post-harmonization grouping of meta-ROIs on the raw native and preprocessed scans were also tested in both versions. The GitHub repositories used in this study to run ComBat and LongComBat are https://github.com/Jfortin1/ComBatHarmonization.git, https://github.com/jcbeer/longCombat.git, respectively.

2.3.2. Basic image processing

2.3.2.1. Histogram matching (HM).

Several MR image intensity normalization methods have been introduced (Reinhold et al., 2019). Most commonly the piecewise linear histogram matching method (Nyú and Udupa, 1999; Reinhold et al., 2019) has been applied for scan harmonization (Bashyam et al., 2021). In this study, we matched the cumulative density function (CDF) of a participant with GE scans with the CDF of the same participant’s scan with Siemens as our test set included paired scans, which made it possible to directly match the intensity values between these two scans. This method is a straightforward algorithm where the CDF of an intensity value from a source image is mapped to the CDF of a reference image to match the intensities between the two scan types. The same procedure was followed for the Crossover and Longitudinal test sets. We used the SciKit-image histogram matching package in Python (van der Walt et al., 2014).

2.3.3. Deep learning-based scan translation methods

2.3.3.1. Neural style transfer.

Neural style transfer (NST) extracts the texture styling of a reference (style) image and then transfers it to a source (content) image (Gatys et al., 2015). In this study, the content images were the GE scans, and Siemens scans were used as style images. The transferred style is constructed from different layers of a pretrained convolutional neural network. The key to capturing style is the construction of a Gram matrix from the activation feature values of the different layers of the network (Eq. (4)):

| (4) |

where is the feature response to the input image, and is the feature activation of filter found at position in layer (Gatys et al., 2015). The Gram matrix is the dot product of the layer’s feature maps of depth (Eq. (4)) (Gatys et al., 2015). Then gradient descent is used to find the scan that matches the style of the Siemens by minimizing the mean-squared distance between the Gram matrix and Siemens, and between the Gram matrix and the stylized GE scans (Gatys et al., 2015). The total loss, , is the sum of the content and style losses which are calculated between the and Siemens scans and the stylized representation at layer (Eq. (5)). The hyperparameters and determine the style and content weights that are applied to the image to determine the degree of stylization.

| (5) |

We first trained 3-D ResNet18 model as a binary classifier with GE () and Siemens () scans as inputs. The 3-D input data () was split into training and validation sets at a ratio of 80% () to 20% (). Minimal data augmentation such as random contrast variations was performed only on the training set while the network was trained with an initial learning rate of 10 −4 and optimized using Adam (Kingma and Ba, 2014). The final model performed at loss values of 0.035 for both the training and validation sets. Then using the classifier model, the NST model was trained using adaptive gradient (ADAGRAD) (Duchi et al., 2011) optimizer for 100 steps per epoch. The stylization was applied by setting the hyperparameters . The creators (Gatys et al., 2015) recommend increasing the training steps and adjusting for the hyperparameters for maximum artistic stylization. However, since we do not want to lose any relevant information from the scans, the minimum transformation was preferred. Hence, the stylization was inspected visually by experimenting with different number of steps per epoch and hyperparameters to finally select the settings that produced the least amount of deformation.

2.3.3.2. Conditional generative adversarial networks (CGAN).

Conditional GANs were introduced by (Mirza and Osindero, 2014) as an improvement to GANs (Goodfellow et al., 2014) where instead of a generator’s input being only random noise , the inputs were conditioned with other information (e.g., class label) allowing control over what is being synthesized. In this study, we adapted the work of (Isola et al., 2016) where they were able to generalize the applicability of CGANs by conditioning the generator using the target image instead of random noise. To keep stochasticity in the synthesized images, Isola et al. added random noise in the dropout layer of the generator (Isola et al., 2016). Hence, the target image is mapped by both networks where the discriminator learns to classify the target vs the generated images ( as fake, and the source vs target images as real (Isola et al., 2016). Here, the target images are the Siemens scans, and the source images are the GE scans. The objective function of the CGAN by Isola et al. is given below (Eq. (6)).

| (6) |

Where is the -loss function for the discriminator (Eq. (7)) and is the conditional loss for the CGAN (Isola et al., 2016) (Eq. (8)).

| (7) |

| (8) |

We trained two models ( and ) alternating between the Longitudinal and Crossover test sets as training sets, i.e., when the Longitudinal set was used for training, the Crossover was assigned as the test set and vice versa (Table 1). This was done for assessing the model generalizability by maintaining data variability between the training and test sets. Training was conducted with a 64-layer U-Net as a generator and a 32-layer PatchGAN as a discriminator. A stride of one was used for in-plane and cross-plane directions. The network was run for approximately 300,000 iterations with an initial learning rate set at 10 −4 for the generator and 10 −6 for the discriminator. Lastly, the final models and performed at generator and discriminator losses of 2.96 and 0.69, and 2.92 and 0.67, respectively.

2.3.3.3. Cycle ‐consistent adversarial network (CycleGAN).

CycleGAN was introduced as an extension to CGANs and eliminates the need for pairing target and source images (Zhu et al., 2017). It consists of two generators ( and ) and two discriminators ( and ) where S1 and S2 are the GE and Siemens scanner domains. The model learns two mapping of and , and will discriminate from using and will discriminate from using . The CycleGAN objective function is the sum of two losses: adversarial loss (Eq. (9)) and cycle-consistency loss (Eq. (10)), .

| (9) |

The adversarial loss consists of the forward and backward losses defined by and where the forward network generates in the style of Siemens and the backward network synthesizes Siemens * in the style of GE. Here, we only concentrate on since our aim is to stylize GE into Siemens. Similarly, the cycle-consistency loss is the sum of the forward and backward cycle losses (Eq. (10)).

| (10) |

We used an encoder (3-layer and 64 filters in the first layer), a 9-block Resnet transformer as a generator, and a decoder (a PatchGAN with 2-layer and 16 filters in the first layer) as a discriminator (Zhu et al., 2017). We used Adam optimizer (Kingma and Ba, 2014) with initial learning rate of , moment of 0.90 and learning decay factor of 50. A stride of one was used for in-plane and cross-plane directions. The network was run for approximately 380,000 iterations. The final model performed at forward adversarial and cycle losses of 0.71 and 0.14, and backward adversarial and cycle losses of 0.68 and 0.12, respectively.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The distribution of mean and standard deviation of each feature before and after scan harmonization for all the methods was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests where significance () implies features come from different samples. Normality was checked by Anderson-Darling tests. The KS test was used to check the feature level comparisons of mean and SD distributions between the CTh measures for each of the individual ROIs or meta-ROIs. Intra-class correlation (ICC) was also used to assess degree of agreement for the Crossover dataset.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the harmonization techniques applied to the Longitudinal dataset, the mean differences of the annualized percent change in CTh were calculated for before vs between scanner change using either two-sided independent t -test or Mann-Whitney test, depending on the normality of the data. Any outliers that may have been introduced due to the scanner change or errors caused by the harmonization methods in the FreeSurfer segmentations process were identified and removed using the interquartile range rule, which considers values below Q1 − 1.5 IQR or above Q3 + 1.5 IQR (where IQR = Q3 − Q1) to be outliers.

3. Results

3.1. Before harmonization, the impact of changing scanners on cortical thickness

3.1.1. Crossover dataset

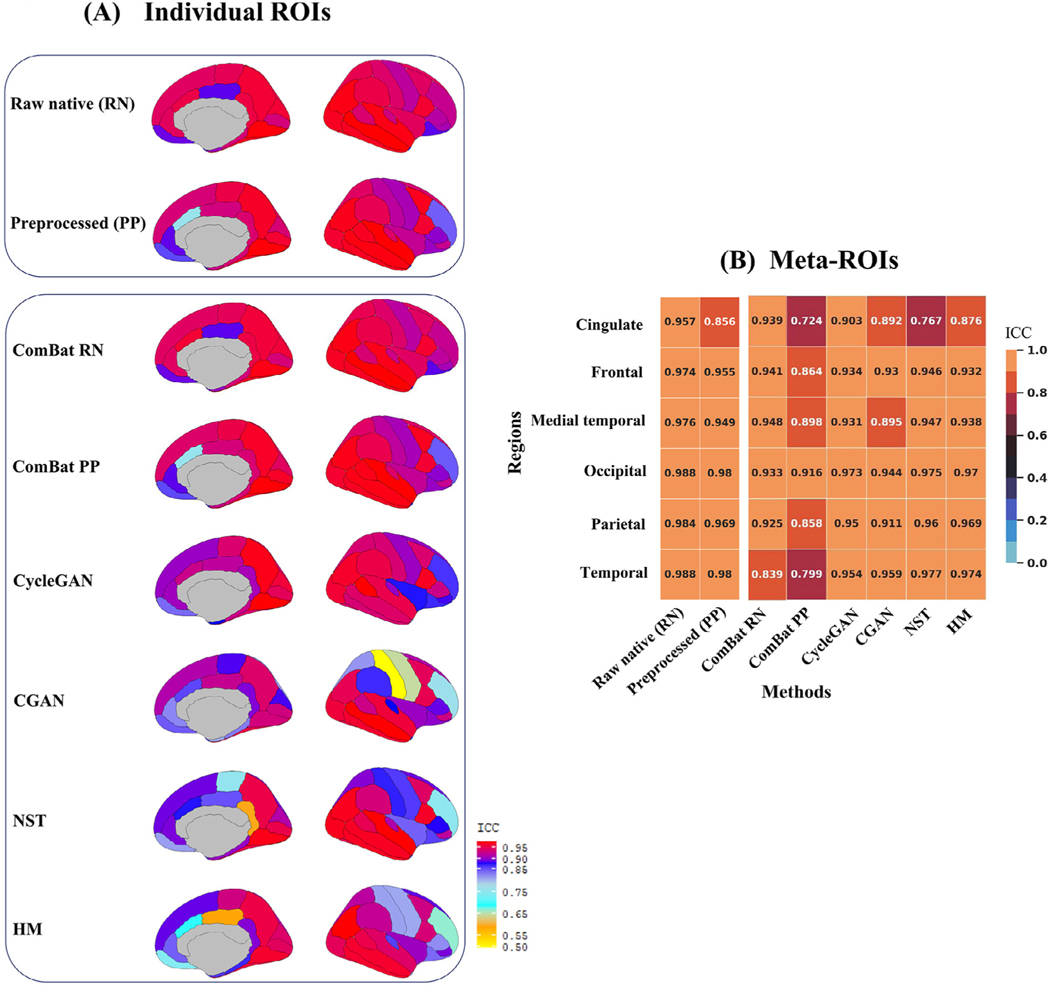

The agreement between CTh values across the ROIs was strong (ICC > 0.90) for most regions except for the frontal pole (ICC [95% CI]: 0.54 [0.33 – 0.69]) and caudal anterior cingulate (0.76 [0.65 – 0.84]) when using the preprocessed scans and was less than 0.90 at the frontal pole (0.72 [0.59 – 0.81]) for the raw native scans (Fig. 1 A). Across the meta-ROIs, regardless of the scan types, the ICC was greater than 0.95 with the lowest ICC for the cingulate region (0.86 [0.79 – 0.90]) only for the preprocessed scans (Fig. 1 B).

Fig. 1.

Heatmaps of the Intra-class correlations (ICC) shown for the Crossover dataset. (A) shows the ICC for the individual regions of interest (ROIs) and (B) the meta-ROIs. The ICCs were obtained by comparing the unharmonized Siemens to the unharmonized GE, and the preprocessed (PP) or raw native (RN) Siemens to each of the harmonized GE scans processed by ComBat, histogram matching (HM), neural style transfer (NST), Conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) and CycleGAN. The ComBat ICCs for meta-ROIs was the same regardless of the order of ROI grouping before or after harmonization.

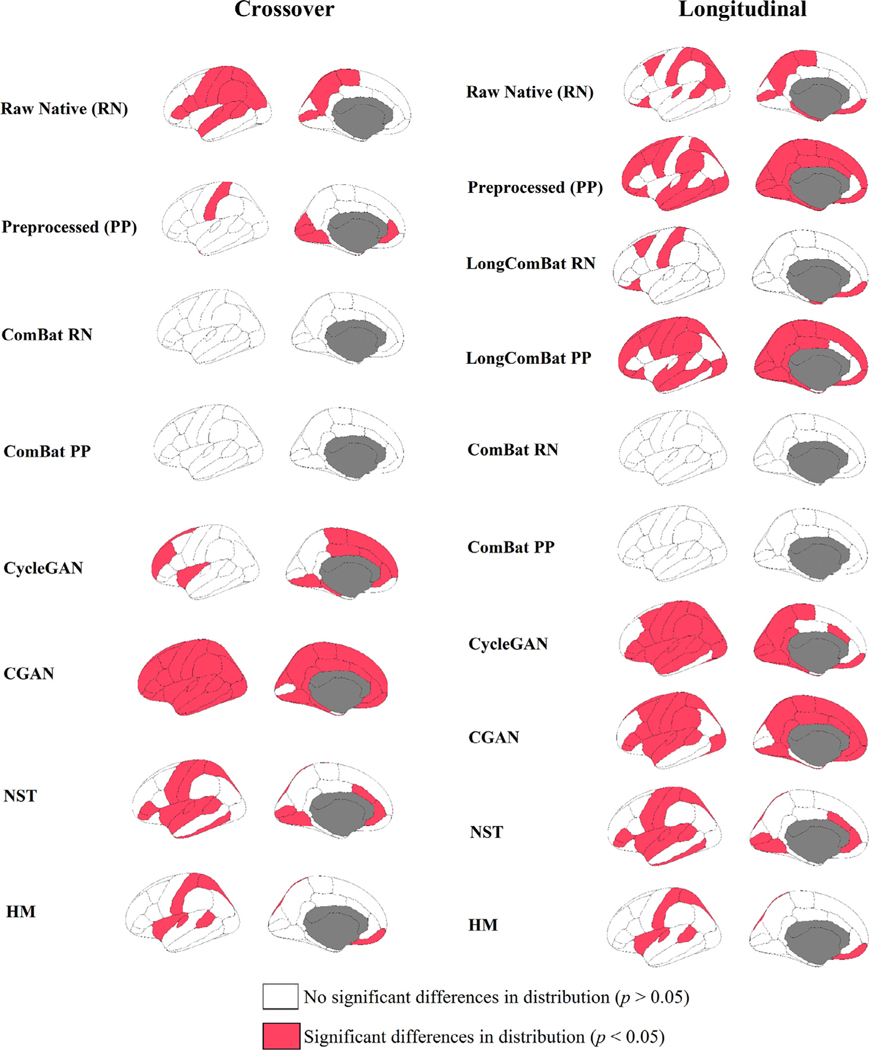

When comparing the distribution of CTh values across the ROIs, 41% (14 out of 34) and 18% (6 out of 34) of the raw native and preprocessed scans, respectively, showed significant differences between the GE and Siemens scans () (Fig. 2). Similarly, the KS test revealed a significant difference in distribution at the frontal and parietal meta-ROIs for the raw native scans and at the occipital meta-ROI for the preprocessed scans () (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test comparing the distribution between the unharmonized Siemens scans and harmonized GE scans that were processed by the different harmonization methods. The red regions indicate areas where significant difference in distribution were found.

3.1.2. Longitudinal dataset

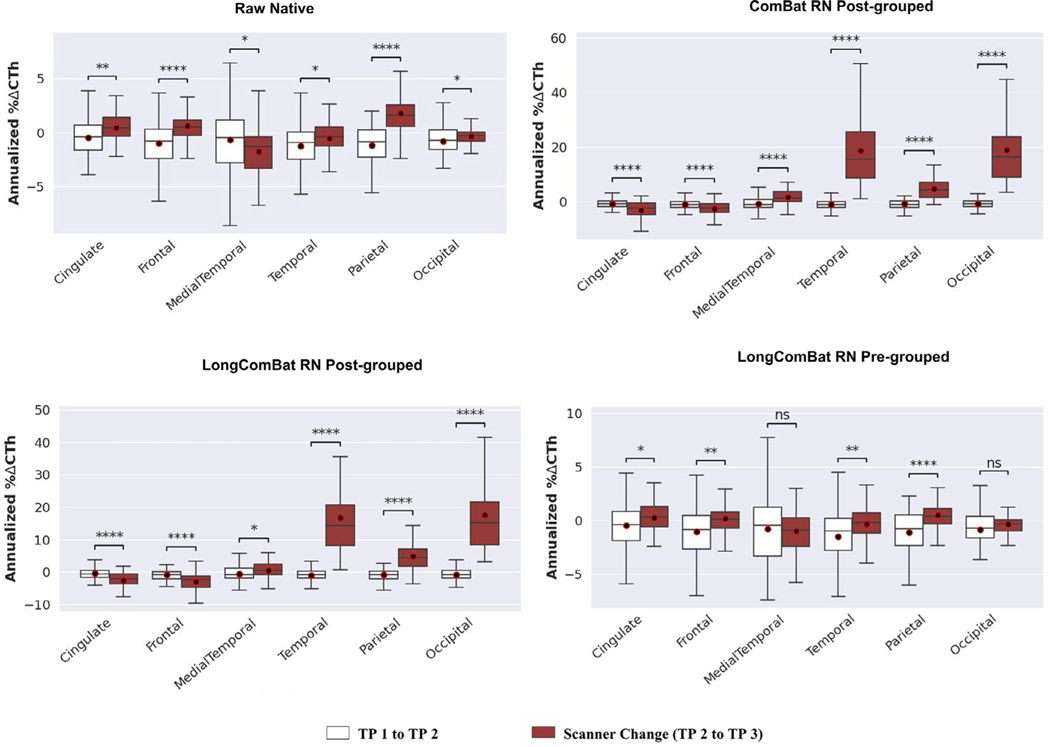

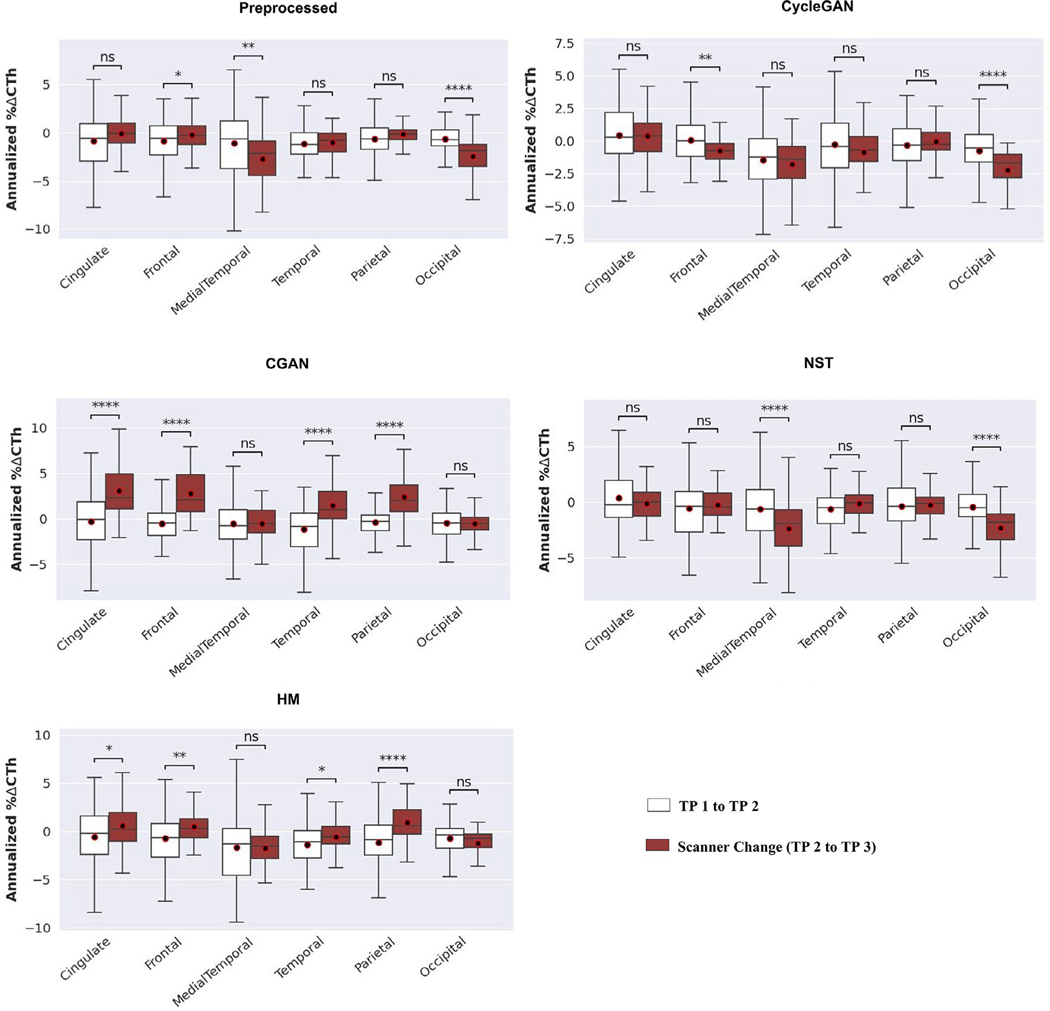

The annualized percent change in CTh showed a significant increase before vs between scanner change for 74% (25 out of 34) and 35% (12 out of 34) of the individual ROIs for the raw native and preprocessed scans, respectively () (Supplementary Fig. 2). Across the meta-ROIs, for the raw native scans, the annualized percent change in CTh significantly increased between scanner change except for the medial temporal and occipital regions where there was a significant decrease () (Fig. 3). For the preprocessed scans, the medial temporal and occipital regions showed a significant decrease while the frontal region showed a significant increase in annualized percent change in CTh between scanner change () (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Boxplots showing annualized percent change in cortical thickness (% ΔCTh) at each meta-ROI in the Longitudinal dataset from time point (TP) 1 to TP 2 and from TP 2 to TP 3. The scanner change was between TP 2 and TP 3 and is shown by the brown color boxplots. The plots for LongComBat on the raw native (RN) scans are shown for both pre-grouping of ROIs before harmonization and post-grouping of ROIs after harmonization while for ComBat only a single plot of post-grouping is shown because the results are the same regardless of the order of grouping.

Fig. 4.

Boxplots showing annualized percent change in cortical thickness (% ΔCTh) at each meta-ROI in the Longitudinal dataset from time point (TP) 1 to TP 2 and from TP 2 to TP 3. The scanner change was between TP 2 and TP 3 and is shown by the brown color boxplots. The plots are shown for the preprocessed scans and the image-based translation methods, CycleGAN, CGAN, neural style transfer (NST), and histogram matching (HM) that were implemented on the preprocessed scans as inputs.

The KS tests across the individual ROIs showed a significant difference in distribution for 41% and 76% of the regions for the raw native and preprocessed scans respectively () (Fig. 2). Across the meta-ROIs, 50% and 67% of the regions showed significant differences in distribution for the for the raw native and preprocessed scans respectively () (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2. Performance of the scan harmonization methods to remove scanner effects

3.2.1. Crossover dataset

When accessing the degree of agreement between harmonized GE and the unharmonized preprocessed Siemens scans using ICC, all the harmonization methods except ComBat were able to increase the ICC for the frontal pole and caudal anterior cingulate regions (Fig. 1 A). In these regions, the highest increase in ICC on the preprocessed scans was measured for the caudal anterior cingulate using NST (ICC [95% CI]: 0.91 [0.87 – 0.94]) and CycleGAN (0.94 [0.91 – 0.96]), and for the frontal pole using NST (0.67 [0.52 – 0.77]), HM (0.69 [0.55 – 0.79]), and CycleGAN (0.67 [0.52 – 0.77]) (Fig. 1 A). Moreover, ComBat on the raw native scans did not improve the ICC between the harmonized and the raw native Siemens scans (Fig. 1 A).

Across the meta-ROIs, the CycleGAN, CGAN and HM methods on the preprocessed scans improved the ICC for the cingulate region with the largest improvement for CycleGAN (0.90 [0.86 – 0.93]) (Fig. 1 B). In addition, except for the cingulate region, none of the methods improved the ICCs between the preprocessed GE and Siemens scans with ComBat performing the worst, regardless of the order of grouping and having ICCs lower than 0.90 for all the regions except for the occipital lobes (Fig. 1 B). Furthermore, at the occipital, parietal, and temporal regions, the CycleGAN, NST and HM that were run on the preprocessed scans, showed better ICCs than the ComBat that was run on the raw native scans with the temporal region showing the lowest ICC (0.84 [0.76 – 0.89]) regardless of the order of grouping the regions (Fig. 1 B).

ComBat successfully matched the distributions, for both the preprocessed and raw native scans, across the individual ROIs (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2). However, regardless of the order meta-ROI grouping or scan type, ComBat only matched the distributions at the medial temporal region across the meta-ROIs —except for the post-grouped medial temporal region of the preprocessed scans (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, CycleGAN and HM were able to match the CTh distribution for 70% and 79% of the regions across the individual ROIs, respectively, and for 67% and 100% of the regions across the meta-ROIs, respectively (Fig. 2).

3.2.2. Longitudinal dataset

Between scanner change more than 60% of the individual ROIs showed significant increase in annualized percent change in CTh when harmonized by most of the methods () (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, CycleGAN and NST showed significant decrease between scanner change compared to before for only 12% (4 out of 34) and 35% (12 out of 34) of the ROIs, respectively () (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly, across the meta-ROIs, CycleGAN and NST showed a significant decrease in annualized percent change in CTh at the frontal and occipital regions, and at the medial temporal and occipital regions, respectively () (Fig. 4). On the other hand, CGAN, HM, ComBat and LongComBat performed similarly and did not improve the annualized percent change in CTh between scanner change (Fig. 4).

ComBat successfully matched the distributions of the mean CTh values between the harmonized GE and unharmonized Siemens scans across the individual ROIs for both scan types while HM outperformed CycleGAN, CGAN and NST by matching 67% of the regions (Fig. 2). LongComBat was only able to match the CTh distributions for 29% and 82% of the individual ROIs for the preprocessed and raw native scans respectively (Fig. 2). For the meta-ROIs, ComBat was able to match the distributions only for the medial temporal region regardless of the scan types or the order of grouping the meta-ROIs (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, LongComBat was only able to match the distributions for 33% and 50% of the regions when the meta-ROIs were post-grouped for the preprocessed and raw scans respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

4. Discussions

In our study, we compared six different T1 MRI scan harmonization methods (histogram matching, neural style transfer, cycle-consistent and conditional generative adversarial networks, ComBat and LongComBat) to evaluate their usefulness in harmonizing brain cortical thickness in an aging and dementia sample. We found that: (1) differences in cortical thickness were observed due to scanner change for the same participants scanned on two different scanners in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, even when the participants were scanned close in time and with similar protocols, highlighting the need for scan harmonization. (2) The performances of the six methods were dependent on the region being analyzed. (3) CycleGAN was the top performing deep learning method based on the intra-class correlations from the preprocessed Crossover dataset. (4) In the Longitudinal dataset, significant variations in cortical thickness were observed due to the scanner change, but none of the methods were able to completely harmonize the observed variations. (5) ComBat did not improve the ICC in the regions of least agreement in the raw native scans and did not perform well when applied to the meta-ROIs of the Longitudinal dataset, while LongComBat had better performance when the ROIs were initially converted to meta-ROIs before harmonization.

The effect of scanner change was clearly visible in the Longitudinal raw native scans indicated by the significant increase and decrease of annualized percent change in CTh due to the changeover. Compared to the other methods, CycleGAN and NST were able to better correct for the significant over- and/or under-estimation of the CTh values, however, none of the methods corrected this effect for all the regions. The preprocessed scans, where the raw native scans were resampled and standardized, performed better than some of the other methods. Previous studies have shown that CTh is more affected to a greater extent than cortical volume as a result of scanner or protocol changes (Hedges et al., 2022; Wittens et al., 2021). A study by Hedges et al., investigated effect of protocol change (ADNI-2 vs ADNI-3), FreeSurfer version and pipeline, test-retest, head positioning and scan sequences on cortical and subcortical thickness, area and volume measurements (Hedges et al., 2022). They found changes in protocol had the least effect and head tilting had the highest effect on all the measures but tilting especially affected CTh values (Hedges et al., 2022). The study also found the reliability of the measures improved with v7.1.0 and longitudinal pipeline showing the highest reliability and outperformed the cross-sectional pipeline (Hedges et al., 2022).

We can divide the methods presented in this study into two categories: statistics-based and image-based. Our results show that, ComBat, the statistics-based method, performs well in aligning feature distributions in both datasets, similar to previous works on cortical thickness harmonization (Da-ano et al., 2020; Fortin et al., 2018). LongComBat also successfully matched 82% of the distributions in the Longitudinal dataset. However, the order of meta-ROI formation affected the performances of the statistics-based methods. Further investigation is needed to understand the differences in behavior between ComBat and LongComBat. In addition to the statistical methods evaluated in this study, there are also other methods such as the work by Zhou et al., where they developed a subsampling technique to identify and correct distribution shifts (Zhou et al., 2018). Furthermore, a recent multicenter data harmonization study by Pagani et al. compared this subsampling method with ComBat and other statistical methods, and they report the subsampling method performed best and produced the least average residuals compared to the other methods including ComBat (Pagani et al., 2022).

The image-based methods can be categorized into deep-learning based and basic image processing. Deep learning (DL)-based methods include domain adaptation (DA) techniques that are rapidly evolving current research areas. In this study, three DL methods were chosen: NST, CGAN and CycleGAN. These methods were chosen due to their established status, 3-D implementations and (3) unique coverage of various DA techniques (NST is texture-based, CGANs are supervised and paired IITs, and CycleGANs are unsupervised and unpaired IITs). However, there are other DA methods that were not included here due to scope and manageability of the study. Some notable examples are the self-domain adaptation (SDA) methods by Y. He et al. who developing an autoencoder based model to adapt between inference (He et al., 2021). Another test-time approach is CALAMITI (Contrast Anatomy Learning and Analysis for MR Intensity Translation and Integration) by Zuo et al. where they introduced a technique for maintaining anatomical and contrast information when performing adaptation (Zuo et al., 2021). A recent study by Bashyam et al. adapted a StarGAN (Choi et al., 2018) to harmonize multicenter scans and perform brain age prediction (Bashyam et al., 2021).

Our results show histogram matching, the most simplistic of the image-based methods, was one of the best performers in terms of improving ICCs for the Crossover dataset. HM has previously been used to harmonize MR scanners (Bashyam et al., 2021; Nyú and Udupa, 1999; Wrobel et al., 2020). One such example is the work by Wrobel et al., for multisite scan harmonization where they introduced a method called mica (multisite image harmonization by CDF alignment) that creates a template CDF from a group of same participants and then performs a non-linear monotonic transformation for removing scanner effects (Wrobel et al., 2020). Another application of histogram manipulation is by He et al. in their SDA methods that made use of pixel level histogram adaptors during test time (He et al., 2021).

To further investigate the performances of the image-based methods, we also conducted voxel-based analysis in FreeSurfer where we performed grouped mean comparisons (t -test) between unharmonized Siemens and GE or translated GE scans. The statistics-based methods were not included in this test because voxel values are required to perform this test, while our implementation of ComBat and LongComBat operate on the extracted morphological measures. The results showed that there were regions both in raw native and preprocessed scans that showed significant difference in CTh, justifying the need for scanner harmonization (Supplementary Figure 4). Amongst all the image-based methods, HM and NST were the best performers in terms of showing no mean differences between the voxel-wise CTh values (Supplementary Figure 3). These results, along with the outcomes of the ICC values, imply that region-based applications, where only the regions initially impacted by the scanner change should be harmonized, may be a viable choice to consider when harmonizing.

The image-based methods apply the scan properties of the reference scan onto the GEs without removing the source scanner effects. The statistics-based methods, on the other hand, remove the scanner effects from either the reference, source, or both scans. In this study, we had the advantage of our test sets containing matched participants with the Siemens serving as the “gold-standard ” reference scans which allowed us to directly quantify the level of harmonization and evaluate the performance of the various methods. However, previous studies quantified the success of their harmonization method using clinically relevant features measured from the harmonized and raw unharmonized scans. For instance, Fortin et al. applied ComBat for removing both scanner and site effects by combining 98 regional CTh measurements collected from 11 sites and validated their results by evaluating the percentage of the variation in CTh explained by age and also predicting age separately on the harmonized and unharmonized values (Fortin et al., 2018). They found a combination of ComBat and Adjusted Residuals methods were able to better explain the percent of variation in CTh with age (R 2 = 33% from the raw R 2 = 23%) and also found that ComBat did not predict age better than the unharmonized raw data (Fortin et al., 2018). Another study by Dan-ano et al. compared the performances of ComBat and its modified versions, M-ComBat (Stein et al., 2015), B-ComBat and BM-ComBat on multisite MRI, PET and CT scans collected from 2 different studies (Da-ano et al., 2020). They validated the methods by evaluating feature distribution and using machine learning to predict clinical outcomes (Da-ano et al., 2020). They report ComBat and the other variants were able to align distributions, however, although they state the harmonized results are “systematically” better, the actual predictive performances were quantitatively similar when using the unharmonized or harmonized values (Da-ano et al., 2020).

This study has some strengths and limitations. We presented a comprehensive framework for evaluating statistical, deep learning-based, and basic image processing scan harmonization methods using participants scanned on two different scanners (which is often seen in longitudinal studies). Specifically, the Crossover cohort created for this purpose was a key strength allowing us to compare MRI scans on two different scanners obtained on the same participants, typically on the same day. Another strength is that we compared functionally distinct post-processing methods that are currently being investigated to address the multi-site and cross-scanner heterogeneity problems. There are some limitations as well. First, the CGAN was trained on a smaller number of inputs compared to the other methods. This was mainly because CGAN is a paired IIT DA method and finding large number of matched and paired scans was a challenge. Second, the down sampling to 1.5 mm 3 could have affected the FreeSurfer CTh measurements. However, this was done due to hardware memory constraints associated with training the deep learning methods on the full 3-D MRI scans of higher resolution. Nevertheless, since resampling can be considered a weaker form of harmonization, it is possible that a resampling-based harmonization could have shown better performance if higher resolution had been used. Third, we only investigated scanner change from one site (i.e., Mayo Clinic), which may have reduced the bias in the data but also could have limited the variance compared to other multi-site harmonization studies. Further experiments are needed to validate our results for the same participants from multiple sites scanned close in time. Fourth, different diagnoses were not considered in this study. Although the participants were matched between the GE and Siemens scans for both datasets, which could have minimized the effect of diagnosis, it is critical to investigate and answer how different disease states respond to scanner change and whether harmonization can address the issue of data heterogeneity differently. In addition, implementation of the harmonizations in the longitudinal dataset could be considered cross-sectional except for LongComBat which nevertheless was not superior in performance to the others. Lastly, we investigated the effects of scanner harmonization on FreeSurfer measurements because it is the most widely used research software for MRI volumetric measurements. It is possible that other types of MRI measurements, or volumetric measurements from other software, may be more affected by scanner differences than FreeSurfer is, and thus may have more potential to benefit from these harmonization approaches.

In conclusion, we found that the choice of a harmonization method should be made based on the clinical application – specifically the region of interest, study type, and data distribution. We assessed longitudinal and cross-sectional study types where the scanner and population differences were considered in the longitudinal study, whereas the scanner effect was the dominant factor to be removed in the cross-sectional study. Although ComBat is currently the widely accepted method, we found that it did not improve the intra-class correlations for either the individual ROIs or the meta-ROIs. We also observed simpler methods such as histogram matching and resampling performed comparably and, in some cases, superior to the advanced methods for the Crossover dataset. CycleGAN was the best performing method for the Crossover datasets. In terms of addressing the over- and/or under-estimation of the cortical thickness values between scanner change, CycleGAN and NST were able to perform slightly better compared to the other methods. Lastly, future research could benefit from combining the statistics-based and image-based methods as well as exploring the effects of scanner change for scans having different AD and dementia diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Mayo Clinic Radiology Research Fellowship, NIH grants R01 NS097495 (PI: Vemuri), R01 AG056366 (PI: Vemuri), U01 AG006786 (PI: Petersen), P50 AG016574 (PI: Petersen), R01 AG034676 (PI: Rocca), R37 AG011378 (PI: Jack), R01 AG041851 (PIs: Jack and Knopman), AG062677, NS100620, AG063911 (PI: Kantarci); the GHR Foundation grant, the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Foundation, the Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum Family Foundation, U.S.A. and Opus building NIH grant C06 RR018898. The funding sources were not involved in the manuscript review or approval.

Footnotes

Credit authorship contribution statement

Robel K. Gebre: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Matthew L. Senjem: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Sheelakumari Raghavan: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Christopher G. Schwarz: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Jeffery L. Gunter: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Ekaterina I. Hofrenning: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Robert I. Reid: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Kejal Kantarci: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Jonathan Graff-Radford: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. David S. Knopman: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ronald C. Petersen: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Clifford R. Jack Jr: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Prashanthi Vemuri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.119912.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bashyam VM, Doshi J, Erus G, Srinivasan D, Abdulkadir A, Singh A, Habes M, Fan Y, Masters CL, Maruff P, Zhuo C, Völzke H, Johnson SC, Fripp J, Koutsouleris N, Satterthwaite TD, Wolf DH, Gur RE, Gur RC, Morris JC, Albert MS, Grabe HJ, Resnick SM, Bryan NR, Wittfeld K, Bülow R, Wolk DA, Shou H, Nasrallah IM, Davatzikos C, 2021. Deep generative medical image harmonization for improving cross-site generalization in deep learning predictors. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging doi: 10.1002/jmri.27908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beer JC, Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Davatzikos C, Sheline YI, Shinohara RT, Linn KA, 2020. Longitudinal ComBat: a method for harmonizing longitudinal multi-scanner imaging data. Neuroimage 220, 117129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Choi M, Kim M, Ha JW, Kim S, Choo J, 2018. StarGAN: unified generative adversarial networks for multi-domain image-to-image translation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE Computer Society, pp. 8789–8797. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2018.00916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da-ano R, Masson I, Lucia F, Doré M, Robin P, Alfieri J, Rousseau C, Mervoyer A, Reinhold C, Castelli J, De Crevoisier R, Rameé JF, Pradier O, Schick U, Visvikis D, Hatt M, 2020. Performance comparison of modified ComBat for harmonization of radiomic features for multicenter studies. Sci. Rep 10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66110-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dinsdale NK, Jenkinson M, Namburete AIL, 2021. Deep learning-based unlearning of dataset bias for MRI harmonisation and confound removal. Neuroimage 228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchi J, Hazan E, Singer Y, 2011. Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res 12, 2121–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin J−P, Cullen N, Sheline YI, Taylor WD, Aselcioglu I, Cook PA, Adams P, Cooper C, Fava M, McGrath PJ, McInnis M, Phillips ML, Trivedi MH, Weissman MM, Shinohara RT, 2018. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. Neuroimage 167, 104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatys LA, Ecker AS, Bethge M, 2015. A neural algorithm of artistic style.

- Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, Courville A, Bengio Y, 2014. Generative adversarial networks.

- He Y, Carass A, Zuo L, Dewey BE, Prince JL, 2021. Autoencoder based self-supervised test-time adaptation for medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal 72. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2021.102136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Carass A, Zuo L, Dewey BE, Prince JL, 2020. Self domain adapted network.

- Hedges EP, Dimitrov M, Zahid U, Brito B, Si S, Dickson H, Mcguire P, Williams S, Barker GJ, Kempton MJ, 2022. NeuroImage Reliability of structural MRI measurements : the effects of scan session, head tilt, inter-scan interval, acquisition sequence, FreeSurfer version and processing stream. Neuroimage 246, 118751. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isola P, Zhu J-Y, Zhou T, Efros AA, 2016. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks.

- Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A, 2007. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8, 118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma DP, Ba J, 2014. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization.

- Liu Mengtingand Maiti P, TS ZA, CY KH JN, 2021. Style transfer using generative adversarial networks for multi-site MRI harmonization. In: de Bruijne Marleenand Cattin PC,CS,PN,SS,ZY,EC (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2021. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Schumacher M, Scherer A, Sanoudou D, Megherbi D, Davison T, Shi T, Tong W, Shi L, Hong H, Zhao C, Elloumi F, Shi W, Thomas R, Lin S, Tillinghast G, Liu G, Zhou Y, Herman D, Li Y, Deng Y, Fang H, Bushel P, Woods M, Zhang J, 2010. A comparison of batch effect removal methods for enhancement of prediction performance using MAQC-II microarray gene expression data. Pharmacogenomics J. 10, 278–291. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza M, Osindero S, 2014. Conditional generative adversarial nets.

- Nyú LG, Udupa JK, 1999. On standardizing the MR im age intensity scale. Magn. Reson. Med 42, 1072–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani E, Storelli L, Pantano P, Petsas N, Tedeschi G, Gallo A, Stefano N De Battaglini M, Rocca MA, Filippi M, 2022. Multicenter data harmonization for regional brain atrophy and application in multiple sclerosis. 10.1007/s00415-022-11387-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Rocca WA, 2010. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. Neurology 75, 889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold JC, Dewey BE, Carass A, Prince JL, 2019. Evaluating the impact of intensity normalization on MR image synthesis. Proc. SPIE–the Int. Soc. Opt. Eng 10949, 109493H. doi: 10.1117/12.2513089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz CG, Gunter JL, Wiste HJ, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Ward CP, Senjem ML, Vemuri P, Murray ME, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Kantarci K, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Jack CR, 2016. A large-scale comparison of cortical thickness and volume methods for measuring Alzheimer’s disease severity. NeuroImage Clin. 11, 802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CK, Qu P, Epstein J, Buros A, Rosenthal A, Crowley J, Morgan G, Barlogie B, 2015. Removing batch effects from purified plasma cell gene expression microarrays with modified ComBat. BMC Bioinformatics 16. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Walt S, Schönberger JL, Nunez-Iglesias J, Boulogne F, Warner JD, Yager N, Gouillart E, Yu T the scikit-image contributors, 2014. scikit-image: image processing in {P}ython. PeerJ 2, e453. doi: 10.7717/peerj.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittens MMJ, Allemeersch GJ, Sima DM, Naeyaert M, Vanderhasselt T, Vanbinst AM, Buls N, De Brucker Y, Raeymaekers H, Fransen E, Smeets D, van Hecke W, Nagels G, Bjerke M, de Mey J, Engelborghs S, 2021. Inter- and intra-scanner variability of automated brain volumetry on three magnetic resonance imaging systems in Alzheimer’s disease and controls. Front. Aging Neurosci 13. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.746982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wrobel J, Martin ML, Bakshi R, Calabresi PA, Elliot M, Roalf D, Gur RC, Gur RE, Henry RG, Nair G, Oh J, Papinutto N, Pelletier D, Reich DS, Rooney WD, Satterthwaite TD, Stern W, Prabhakaran K, Sicotte NL, Shinohara RT, Goldsmith J, 2020. Intensity warping for multisite MRI harmonization. Neuroimage 223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HH, Singh V, Johnson SC, Wahba G, 2018. Statistical tests and identifiability conditions for pooling and analyzing multisite datasets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, 1481–1486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719747115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-Y, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA, 2017. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks.

- Zuo L, Dewey BE, Liu Y, He Y, Newsome SD, Mowry EM, Resnick SM, Prince JL, Carass A, 2021. Unsupervised MR harmonization by learning disentangled representations using information bottleneck theory. Neuroimage 243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.