Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, pathologically characterized by senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), resulting in neurodegeneration. Neuroinflammation, defined as the activation of glial cells such as microglia and astrocytes, is observed surrounding senile plaques and affected neurons in AD. Recently conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) indicate that a large section of identified AD risk genes are involved in immune responses and are enriched in microglia. Microglia are innate immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS), which are involved in immune surveillance and maintenance of homeostasis in the CNS. Recently, a novel subpopulation of activated microglia named as disease-associated microglia (DAM), also known as activated response microglia (ARM) or microglial neurodegenerative phenotype (MGnD), was identified in AD model mice. These microglia closely associate with β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and exhibit characteristic gene expression profiles accompanied with reduced expressions of homeostatic microglial genes. However, it remains unclear whether decreased homeostatic microglia functions or increased DAM/ARM/MGnD functions correlate with the degree of neuronal loss in AD. To translate the results of rodent studies to human AD, precuneus, the brain region vulnerable to β-amyloid accumulation in preclinical AD, is of high interest, as it can provide novel insights into the mechanisms of microglia response to Aβ in early AD. In this study, we performed comparative analyses of gene expression profiles of microglia among three representative neurodegenerative mouse models and the human precunei with early AD pathology. We proceeded to evaluate the identified genes as potential therapeutic targets for AD. We believe that our findings will provide important resources to better understand the role of glial dysfunction in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Disease-associated microglia, Homeostatic microglia, Neuroinflammation, Precuneus

Background

Neuroinflammation and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

AD is the most common cause of dementia and is associated with a progressive neurodegeneration. Globally, the number of patients with dementia is predicted to reach 139 million in 2050 [1]. AD is pathologically characterized by senile plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), consisting of β-amyloid (Aβ) aggregates and hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated protein Tau, respectively, resulting in neuronal dystrophy and loss, respectively [2]. Neuroinflammation, defined as activation of glial cells, such as microglia and astrocytes, and subsequent production of inflammatory factors such as cytokines and chemokines surrounding senile plaques and affected neurons in the brains, is observed in AD patients [3]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of AD risk genetic variants revealed that a large proportion of identified genes were closely related to immune responses, and that their expressions were enriched in microglia and macrophages [4–7].

Microglia, one of the resident innate immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS), originate from erythromyeloid progenitor cells in the embryonic yolk sac [8]. Microglia play an important role in immune surveillance, by phagocytotic clearance of pathogens, dead cells, cellular debris, and protein aggregates like those of Aβ, and help maintain homeostasis in the CNS [9]. Microglia also contribute to brain development and its maintenance by participating in synaptic pruning and myelination [10]. Meanwhile, once microglia respond to their stimuli, their gene expression profiles undergo distinct alterations, with an immediate production of various inflammatory cytokines and mediators and a change in their morphology to an amoeboid shape [11]. It is suggested that long-lasting neuroinflammation causes a decline in homeostatic functions of microglia, resulting in neuronal loss and neurodegenerative diseases. However, it is unknown whether the loss of homeostatic functions of microglia can be correlated with the degree of neurodegeneration and neuronal loss.

Recent advanced single-cell technologies have revealed that microglia intrinsically are a heterogeneous population. One group identified a novel subpopulation of activated microglia named as disease-associated microglia (DAM) or activated response microglia (ARM) in AD model mice [12, 13]. Another group also identified a similar microglia subpopulation, namely microglial neurodegenerative phenotype (MGnD) by RNA sequence (RNA-seq) analysis of isolated microglia from the AD model mice [14]. These microglial populations were observed to be associated with Aβ plaques, displayed characteristic gene expression profiles, and were accompanied with decreased expressions of homeostatic microglia marker genes. Moreover, these microglia were also identified in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a selective loss of motor neurons. They expressed an ALS-linked mutant form of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) [12, 14]. Intriguingly, whereas TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2) and APOE (apolipoprotein E) are major AD risk genes [15–17], the expressions of TREM2 and APOE in microglia were found to be necessary for the induction of DAM/ARM/MGnD in both AD and ALS model mice [12–14]. However, it is still not clear whether the contribution is either positive or negative of DAM/ARM/MGnD in AD and ALS.

Precuneus is vulnerable to early Aβ accumulation in preclinical AD

Several studies have earlier examined the expression of neuroinflammatory genes in the prefrontal or entorhinal cortex of the patients with AD using single nucleus transcriptome analysis [18–20]. However, there are only a few transcriptomic studies focusing on the precuneus [21, 22], the region of the brain, where Aβ accumulation is observed in preclinical AD patients [23, 24]. Therefore, the transcriptomic analysis of precuneus is of particular interest, as it can provide novel insights into the response of microglia to Aβ in early AD. Hence, we performed a gene expression analysis using RNA-seq in the precuneus of early AD patients, in parallel with AD model mice.

Main text

The reduced expression of microglial homeostatic genes was correlated with the degree of neuronal cell loss

To examine the correlation between the loss of homeostatic microglia functions and the degree of neuronal cell loss, we analyzed the expression levels of 68 homeostatic microglial genes in microglia isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting from three representative mouse models exhibiting different severities of neurodegeneration.

First model was an AD model, homozygous AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F knock-in mouse carrying App gene with humanized Aβ sequence having three familial AD mutations: Swedish (KM670/671NL), Beyreuther/Iberian (I716F), and Arctic (E693G), exhibiting amyloid pathology and neuroinflammation in an age-dependent manner without neuronal cell loss or NFTs [25].

Second model was a tauopathy model, rTg4510 mouse overexpressing a mutant form of human Tau carrying the P301L mutation of familial frontotemporal dementia, resulting in brain atrophy with neuronal loss and neuroinflammation [26].

The third model was an ALS model, SOD1G93A mouse expressing a mutant form of human SOD1 carrying the G93A mutation of familial ALS, displaying motor neuron loss and neuroinflammation [27].

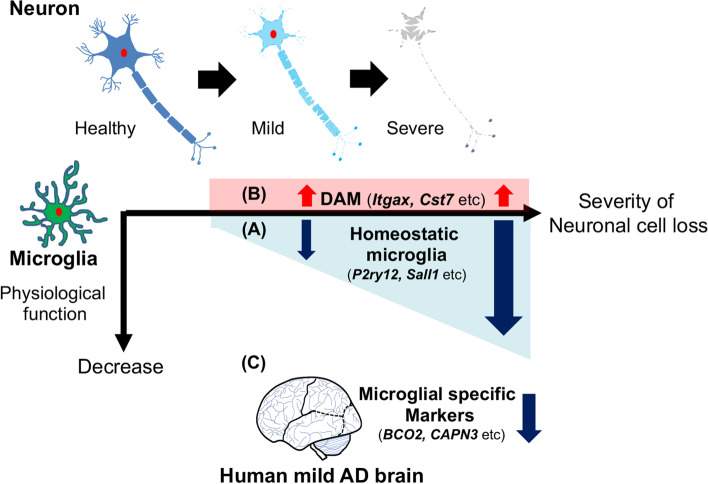

In this study, we used AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mouse as a model of mild disease and rTg4510 and SOD1G93A mice as severe models of neurodegenerative diseases. We found that microglia isolated from rTg4510 cortices and SOD1G93A spinal cords distinctly showed reduced expressions of homeostatic microglial genes, whereas these reductions were not observed in microglia from AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F cortices. Moreover, the decrease in their expressions in SOD1G93A spinal microglia was more obvious than those in rTg4510 cortical microglia. Since SOD1G93A mice exhibit faster progression of neurodegeneration than rTg4510 mice, this reduced expression might be attributed to the severity of neuronal loss. A combination of these two observations suggests that the reduced expression levels of homeostatic microglial genes could be related to the degree of neuronal loss. In particular, we found that P2ry12 and Sall1 expressions were strongly associated with the degree of neuronal loss [28]. Previous reports indicate that P2RY12 is essential for regulating microglial activation via extracellular nucleotides derived from dead cells [29, 30], and that SALL1 encoding a transcriptional regulator inhibits a reactive microglia phenotype and promotes a physiological surveilling phenotype [31]. These reports indicate that these proteins influence the maintenance of the CNS homeostasis. Intriguingly, the reduction of homeostatic microglial gene expressions was also observed in both model mice of cuprizone-induced demyelination and the patients with multiple sclerosis, implying that the demyelination may act as a trigger for it perhaps prior to the neuronal loss [32]. Therefore, the loss of microglial homeostatic functions may be one of the primary hallmarks of progressive neurodegeneration, and their maintenance is presumably beneficial and might be a potential target for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1A) [28].

Fig. 1.

A schematic illustration for the microglial signature and their relevance to the severity of neurodegeneration in AD. A Microglial gene signature in mice revealed that a loss of homeostatic microglial function is associated with the degree of neuronal cell loss. B Most of the DAM genes were uniformly upregulated in each model. C In humans, a gene expression analysis of the precuneus of mild AD pathology also indicates a loss of microglial function induced by mild amyloid pathology

No association between the expression levels of DAM genes and the severity of neurodegeneration

In order to examine the expressions of DAM genes and the correlation between their expression levels and severities of neuronal cell loss in these mouse models, we compared the expression profiles of the162 DAM genes in the microglia of each model (fold change > 1.5, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05) [12]. While almost all of the DAM genes, including Itgax and Csf1, were uniformly upregulated in the microglia of each model, the expression levels of twelve genes including Apoe, Axl, and Cybb seemed to have a correlation with the severity of neuronal cell loss [28]. These results indicate that increased expressions of DAM genes were not correlated with the degree of neuronal cell loss. Among the twelve identified genes, previous studies have indicated that Apoe, known as a major risk factor for AD, is essential for inducing DAM [14, 33]. We found that the expression level of Apoe negatively correlated with both homeostatic microglial genes and the neuronal survival. However, our results did not indicate any overall correlations between the expression levels of majority of the DAM genes, homeostatic microglial genes, and the degree of neuronal loss. Therefore, these findings suggest that the progression of neurodegeneration is not directly linked to DAM genes, but a few molecules including APOE may be involved in both homeostatic microglial dysfunctions as well as the progression of neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1B) [28].

Transcriptomic analysis revealed moderate dysfunctions of microglia and oligodendrocytes in human precuneus with AD pathology

To uncover the changes in gene expression in the human brain with an early amyloid pathology, we performed RNA-seq analysis on the precuneus region derived from brains of deceased individuals. The subjects were either neuropathologically diagnosed with mild AD or controls. These samples were selected based on the Braak neuropathological staging [34] as follows:

Fourteen non-AD brains (Braak stage: 0-A for senile plaque (SP) and 0–2 for NFT)

Eleven early AD brains (Braak stage: C for SP and 3–4 for NFT)

All subjects with mild AD pathology had no apparent family history of dementia, implying that they were sporadic cases. We identified 643 deregulated genes, consisting of 127 upregulated and 516 downregulated genes in AD precunei (|fold change|> 1.5, q < 0.05). We compared the gene expression profiles of each precuneus with lists of neuron-, microglia-, astrocyte-, and oligodendrocyte-specific marker genes. Although the expressions of the representative microglial activation marker genes, such as AIF1, CD68, and LGALS3, were not altered, those of microglial-specific genes such as BCO2, CAPN3, small G-protein-associated genes (RASGRP3 and RAPGEF5), PACC1, also known as TMEM206, and P2RX7, were significantly decreased in AD precunei compared with controls. Moreover, the expressions of oligodendrocyte marker genes such as MBP, MAG, CLDN11, MOG, and CNP were also significantly decreased in AD precunei. However, there were no differences in the expressions of representative neuron and astrocyte marker genes. Our analyses revealed that the early amyloid pathology induces moderate dysfunctions of microglia and oligodendrocytes in the AD precuneus. Of note, the pathogenic role of deregulated oligodendrocytes is an open question. Our data suggest that both microglia and oligodendrocyte dysfunction may contribute to brain dysfunction induced by early AD pathology (Fig. 1C) [28].

There were subtle alterations in DAM gene expressions in the AD precuneus

Although reactive microgliosis with neuroinflammation is one of the neuropathological characteristics of the AD brain [3, 35–37], it is not fully clear whether DAM gene expressions are deregulated in human precunei with early AD pathology. Our expression analysis revealed that only eight DAM genes (APBB2, ARAP2, DHCR7, ENPP2, MYO1E, CD22, KCNJ2, and SLC44A1) out of 162 DAM genes were deregulated in the AD precuneus, and unexpectedly, all of them were downregulated. In addition, the expression levels of representative DAM genes including ITGAX, CST7, APOE, CSF1, and AXL were marginally altered in these samples. Contrary to the prominent upregulation of DAM marker genes in the cortices of AD model mice, these expressions were hardly induced in human sporadic AD precunei [28]. Similar to our result, the previous transcriptomics studies have shown that few DAM genes were induced in human AD brains [19, 20, 38, 39]. The difference in reactivities to Aβ between human and mouse microglia was also reported [40]. These pieces of evidence suggest the discordance in microglial transcriptome signature between humans and mice in AD conditions. In addition, recent studies pointed out the low sensitivity of single nucleus RNA-seq to detect DAM genes in human postmortem brains [38, 41]. This low sensitivity may be attributed to the redistribution of DAM mRNAs to the cytosol or instability of DAM mRNAs. Alternatively, there is a possibility that microglial functions may be suppressed at the early stage of amyloid pathology in humans. Thus, to elucidate the significance of homeostatic microglia and DAM in human AD, further comparative transcriptomic analyses using the brain samples with early and advanced AD will be required.

Identification of common altered genes in human AD precuneus and microglia of the mouse models of AD pathology

To understand the neuroinflammatory nature of early amyloid pathology in AD, we compared gene expression profiles among deregulated genes of AD precunei (|fold change| > 1.2, q < 0.05), those of AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F cortical microglia, and those of rTg4510 cortical microglia (|fold change| > 1.5, q < 0.05, cut-off TPM > 5). We identified eight upregulated genes and twenty-four downregulated genes in common among them. These upregulated genes include a chemokine (CXCL10) and interferon-induced genes (STAT1, IFIT3, ISG15), implying neuroinflammatory responses in AD precunei and AD mice. In addition, AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice shared forty-four deregulated genes (three upregulated and forty-one downregulated) with AD precunei. On the other hand, rTg4510 mice shared deregulated thirteen genes (two upregulated and eleven downregulated) with AD precuneus in common. Our data suggests that AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F and rTg4510 cortical microglia may represent distinct neuroinflammatory aspects relevant to AD pathologies [28]. Indeed, a previous study showed that microglia reactivities were different between amyloid and Tau pathologies [42]. In-depth analyses of molecular mechanisms in the identified molecules will lead to a better understanding of glial dysfunctions and identification of novel therapeutic targets.

Conclusions

In the present review, we have discussed the microglial subtypes and molecular pathogenesis of microglia in AD. The results from our study indicate a correlation between glial phenotypes and the severity of neurodegeneration. Loss of microglial homeostatic functions might have a significant impact on the progression of neurodegeneration. Therefore, maintenance of homeostatic microglial functions is thought to be important in early AD. Although a validation of deregulated microglial genes at the protein level will be required, this review will provide important resources to better understand the role of glial dysfunction in AD. Further understanding of the molecular pathology and function of microglia during AD progression will contribute to development of AD therapies targeting neuroinflammation.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

β-Amyloid

- ACHE

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALDH1L1

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- APBB2

Amyloid-beta precursor protein-binding family B member 2

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- App

Amyloid precursor protein

- ARAP2

ArfGAP with RhoGAP domain, ankyrin repeat, and PH domain 2

- ARM

Activated response microglia

- AXL

AXL receptor tyrosine kinase

- CSF1

Colony-stimulating factor 1

- CST7

Cystatin F

- Cxcl10

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10

- Cybb

Cytochrome b-245 beta chain

- DAM

Disease-associated microglia

- DHCR7

7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- ENPP2

Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 2

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GRIN1

Glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 1

- GRIN2B

Glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2B

- IFIT3

Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3

- ISG15

ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier

- ITGAX

Integrin subunit alpha X

- KCNJ2

Potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 2

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated protein 2

- MGnD

Microglial neurodegenerative phenotype

- MYO1E

Myosin IE

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangle

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- P2RY12

Purinergic receptor P2Y12

- PTPRD

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D

- S100B

S100 calcium-binding protein B

- SALL1

Spalt-like transcription factor 1

- SLC44A1

Solute carrier family 44 member 1

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- SP

Senile plaque

- STAT1

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- SYP

Synaptophysin

- TNFSF10

TNF superfamily member 10

- Trem2

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2

Authors’ contributions

AS and OK wrote the manuscript’s initial draft. KY revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research JP20K16488 (A. S.), JP21K07273 (O. K.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), JST (Moonshot R&D; Grant Number JPMJMS2024), AMED (Grant Number, JP22wm0425014h0002), Takeda Science Foundation (K. O., K. Y.), and the Hori Sciences & Arts Foundation (A. S., K. Y.).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Akira Sobue, Email: a-sobue@riem.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Okiru Komine, Email: okomine@riem.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Koji Yamanaka, Email: koji.yamanaka@riem.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Shin JH. Dementia Epidemiology Fact Sheet 2022. Ann Rehabil Med. 2022;46(2):53–59. doi: 10.5535/arm.22027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. New England J Med. 2010;362(4):329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL, Jacobs AH, Wyss-Coray T, Vitorica J, Ransohoff RM, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bis JC, Jian X, Kunkle BW, Chen Y, Hamilton-Nelson KL, Bush WS, Salerno WJ, Lancour D, Ma Y, Renton AE, et al. Whole exome sequencing study identifies novel rare and common Alzheimer’s-associated variants involved in immune response and transcriptional regulation. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(8):1859–1875. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost GR, Jonas LA, Li YM. Friend, foe or both? Immune activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:337. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimenova AA, Raj T, Goate AM. Untangling genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(4):300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wightman DP, Jansen IE, Savage JE, Shadrin AA, Bahrami S, Holland D, Rongve A, Borte S, Winsvold BS, Drange OK, et al. A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2021;53(9):1276–1282. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00921-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butovsky O, Weiner HL. Microglial signatures and their role in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(10):622–635. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spittau B. Aging microglia-phenotypes, functions and implications for age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:194. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar E, Barak B. Microglia roles in synaptic plasticity and myelination in homeostatic conditions and neurodevelopmental disorders. Glia. 2019;67(11):2125–2141. doi: 10.1002/glia.23637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodburn SC, Bollinger JL, Wohleb ES. The semantics of microglia activation: neuroinflammation, homeostasis, and stress. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):258. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keren-Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, Matcovitch-Natan O, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Ulland TK, David E, Baruch K, Lara-Astaiso D, Toth B et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276-1290 e1217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Sala Frigerio C, Wolfs L, Fattorelli N, Thrupp N, Voytyuk I, Schmidt I, Mancuso R, Chen WT, Woodbury ME, Srivastava G et al. The major risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: age, sex, and genes modulate the microglia response to abeta plaques. Cell Rep. 2019;27(4):1293-1306 e1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, Beckers L, O'Loughlin E, Xu Y, Fanek Z et al: The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity. 2017;47(3):566-581 e569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, Bjornsson S, Huttenlocher J, Levey AI, Lah JJ, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):107–116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu CC, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(9):501–518. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grubman A, Chew G, Ouyang JF, Sun G, Choo XY, McLean C, Simmons RK, Buckberry S, Vargas-Landin DB, Poppe D, et al. A single-cell atlas of entorhinal cortex from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease reveals cell-type-specific gene expression regulation. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(12):2087–2097. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathys H, Davila-Velderrain J, Peng Z, Gao F, Mohammadi S, Young JZ, Menon M, He L, Abdurrob F, Jiang X, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2019;570(7761):332–337. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Song WM, Andhey PS, Swain A, Levy T, Miller KR, Poliani PL, Cominelli M, Grover S, Gilfillan S, et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):131–142. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0695-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guennewig B, Lim J, Marshall L, McCorkindale AN, Paasila PJ, Patrick E, Kril JJ, Halliday GM, Cooper AA, Sutherland GT. Defining early changes in Alzheimer’s disease from RNA sequencing of brain regions differentially affected by pathology. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4865. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83872-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He B, Perez SE, Lee SH, Ginsberg SD, Malek-Ahmadi M, Mufson EJ. Expression profiling of precuneus layer III cathepsin D-immunopositive pyramidal neurons in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for neuronal signaling vulnerability. J Comp Neurol. 2020;528(16):2748–2766. doi: 10.1002/cne.24929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmqvist S, Scholl M, Strandberg O, Mattsson N, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Landau S, Jagust W, Hansson O. Earliest accumulation of beta-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolk DA, Price JC, Saxton JA, Snitz BE, James JA, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Cohen AD, Weissfeld LA, Mathis CA, et al. Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(5):557–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, Iwata N, Saido TC. Single app knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(5):661–663. doi: 10.1038/nn.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, Paulson J, Kotilinek L, Ingelsson M, Guimaraes A, DeTure M, Ramsden M, McGowan E, et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309(5733):476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, Kwon YW, Deng HX. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobue A, Komine O, Hara Y, Endo F, Mizoguchi H, Watanabe S, Murayama S, Saito T, Saido TC, Sahara N, et al. Microglial gene signature reveals loss of homeostatic microglia associated with neurodegeneration of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-01099-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, Koeglsperger T, Dake B, Wu PM, Doykan CE, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(1):131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynes SE, Hollopeter G, Yang G, Kurpius D, Dailey ME, Gan WB, Julius D. The P2Y12 receptor regulates microglial activation by extracellular nucleotides. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(12):1512–1519. doi: 10.1038/nn1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holtman IR, Skola D, Glass CK. Transcriptional control of microglia phenotypes in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(9):3220–3229. doi: 10.1172/JCI90604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Böttcher C, Amann L, Sagar, Scheiwe C, Nessler S, Kunz P, van Loo G et al: Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of mouse and human microglia at single-cell resolution. Nature 2019, 566(7744):388-392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Shi Y, Yamada K, Liddelow SA, Smith ST, Zhao L, Luo W, Tsai RM, Spina S, Grinberg LT, Rojas JC, et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature. 2017;549(7673):523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature24016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braak HBE. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Strooper B, Karran E. The cellular phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2016;164(4):603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skokowa J, Cario G, Uenalan M, Schambach A, Germeshausen M, Battmer K, Zeidler C, Lehmann U, Eder M, Baum C, et al. LEF-1 is crucial for neutrophil granulocytopoiesis and its expression is severely reduced in congenital neutropenia. Nat Med. 2006;12(10):1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/nm1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Streit WJ, Mrak RE, Griffin WS. Microglia and neuroinflammation: a pathological perspective. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Del-Aguila JL, Li Z, Dube U, Mihindukulasuriya KA, Budde JP, Fernandez MV, Ibanez L, Bradley J, Wang F, Bergmann K, et al. A single-nuclei RNA sequencing study of Mendelian and sporadic AD in the human brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):71. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivasan K, Friedman BA, Etxeberria A, Huntley MA, van der Brug MP, Foreman O, Paw JS, Modrusan Z, Beach TG, Serrano GE, et al. Alzheimer’s patient microglia exhibit enhanced aging and unique transcriptional activation. Cell Rep. 2020;31(13):107843. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mancuso R, Van Den Daele J, Fattorelli N, Wolfs L, Balusu S, Burton O, Liston A, Sierksma A, Fourne Y, Poovathingal S, et al. Stem-cell-derived human microglia transplanted in mouse brain to study human disease. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(12):2111–2116. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0525-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thrupp N, Sala Frigerio C, Wolfs L, Skene NG, Fattorelli N, Poovathingal S, Fourne Y, Matthews PM, Theys T, Mancuso R, et al. Single-nucleus RNA-Seq is not suitable for detection of microglial activation genes in humans. Cell Rep. 2020;32(13):108189. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito TST. Neuroinflammation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9:211–218. doi: 10.1111/cen3.12475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.