Abstract

Introduction

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) following high-dose chemotherapy is applied as salvage therapy in patients with relapsed disease or as first-line consolidation in high-risk DLBCL with chemo-sensitive disease. However, the prognosis of relapsing DLBCL post-ASCT remained poor until the availability of CAR-T cell treatment. To appreciate this development, understanding the outcome of these patients in the pre-CAR-T era is essential.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 125 consecutive DLBCL patients who underwent HDCT/ASCT.

Results

After a median follow-up of 26 months, OS and PFS were 65% and 55%. Fifty-three patients (42%) had a relapse (32 patients, 60%) or refractory disease (21 patients, 40%) after a median of 3 months post-ASCT. 81% of relapses occurred within the first year post-ASCT with an OS of 19% versus 40% at the last follow-up in patients with later relapses (p=0.0022). Patients with r/r disease after ASCT had inferior OS compared to patients in ongoing remission (23% versus 96%; p<0.0001). Patients relapsing post-ASCT without salvage therapy (n=22) had worse OS than patients with 1–4 subsequent treatment lines (n=31) (OS 0% versus 39%; median OS 3 versus 25 months; p<0.0001). Forty-one (77%) of patients relapsing after ASCT died, 35 of which due to progression.

Conclusions

Additional therapies can extend OS but mostly cannot prevent death in DLBCL relapsing/refractory post-ASCT. This study may serve as a reference to emerging results after CAR-T treatment in this population.

Keywords: Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T)

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS) responds effectively to immunochemotherapy, with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) being the first-line standard.1–6 In up to 60% of patients, this treatment provides definite complete remission.7,8 Nevertheless, 30–50% of patients will suffer from relapsed or progressive disease, mostly within the first two years. The current treatment of choice for this patient population is salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with peripheral autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT).9–12 The most widely used HDCT regimens are BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan)11,13, or BeEAM with bendamustine replacing BCNU.14,15

Although HDCT followed by ASCT is a successful treatment option for many patients with relapsed DLBCL or high-risk presentation, this treatment is associated with relevant toxicity; importantly, up to 50% of these patients will still relapse or are refractory to this treatment.16–19 Prognosis of these patients is dismal, and treatment options have been limited so far. Some r/r patients may not receive further interventions after HDCT/ASCT due to lack of response to salvage chemotherapy, poor general condition, or the patient’s request, and they undergo palliative treatment. For patients eligible for further therapies, options comprise chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, or combinations of these, in selected cases, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a second ASCT, or, more recently, CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) T-cell therapy.11,20 CAR T-cell therapy is a promising new option for patients with DLBCL after two or more therapy lines fail. Recent studies have shown remarkable CR rates of between 40% to 58%.21–26 On the other hand, CAR T-cell therapy can be associated with relevant specific complications, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or CAR T-cell-related encephalopathy syndrome (CRES/ICANS).21–25,27–29 We performed a retrospective study to describe the outcome of patients with DLBCL after HDCT/ASCT and to determine how high-risk or relapsed DLBCL was managed in clinical practice before the availability of CAR-T cell treatment.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This single-center, non-interventional, retrospective study analyzed the outcome of all consecutive patients with relapsed DLBCL or patients with high-risk presentation who underwent HDCT/ASCT between May 2005 and February 2019 at the University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland. Treatment for DLBCL prior to HDCT/ASCT was applied in various referring centers in Switzerland. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of either high-risk DLBCL or relapsed DLBCL (with the subtypes shown in Table 1), age of at least 18 years at first diagnosis, and sufficient information on remission status after HDCT with ASCT. Patients with high-risk presentation who were consolidated with ACST after first-line therapy had to have a chemo-sensitive disease and had to achieve partial or complete remission before consolidation.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, lymphoma subtypes, stage and international prognostic index, B-symptoms, CNS infiltration and infiltration of bone marrow at first diagnosis in patients with or without relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT.

| Parameter | All patients n (%) | Relapsed patients n (%) | Non-relapsed patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 125 (100) | 53 (42) | 72 (58) |

| Gender | |||

| Male/female (ratio) | 79/46 (1.7:1) | 32/21 (1.5:1) | 47/25 (1.9:1) |

| Age, years, median (range) | |||

| At first diagnosis | 58 (23–76) | 58 (24–75) | 58 (23–76) |

| > 60 years | 54 (43) | 24 (45) | 30 (42) |

| < 60 years | 71 (57) | 29 (55) | 42 (58) |

| Interval first diagnosis – ASCT, months, median (range) | 8 (2–224) | 9 (2–81) | 7 (2–224) |

| Lymphoma subtypes, number (%) | |||

| NOS (not otherwise specified) | 60 (48) | 29 (55) | 31 (44) |

| High-grade BCL (double or triple hits) | 12 (10) | 4 (8) | 8 (11) |

| Primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma | 5 (4) | 2 (4) | 3 (4) |

| Primary DLBCL of the CNS | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) |

| THRLBCL | 10 (8) | 4 (8) | 6 (8) |

| Intravascular large BCL | 6 (5) | 2 (4) | 4 (6) |

| Transformed into DLBCLa | 23 (18) | 9 (17) | 14 (19) |

| Others | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | 4 (6) |

| Stage (Ann-Arbor Classification)b | |||

| I | 7 (6) | 3 (6) | 4 (6) |

| II | 26 (21) | 10 (19) | 16 (23) |

| III | 29 (24) | 13 (25) | 16 (23) |

| IV | 59 (49) | 26 (50) | 33 (48) |

| IPI Risk Score (aaIPI, IPI) c | |||

| low risk | 15 (16) | 4 (12) | 11 (19) |

| low-intermediate risk | 15 (16) | 6 (18) | 9 (15) |

| high-intermediate risk | 35 (38) | 14 (42) | 21 (36) |

| high risk | 27 (29) | 9 (27) | 18 (31) |

| B-symptoms | 44 (35) | 21 (40) | 23 (32) |

| CNS infiltration | 13 (10) | 7 (13) | 6 (8) |

| Infiltration of bone marrow | 27 (22) | 14 (26) | 13 (18) |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; THRLBCL, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; IPI, international prognostic index; CNS, central nervous system.

Transformed into DLBCL from: follicular lymphoma (n=16), CLL (n=5), marginal zone lymphoma (n=1), nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (n=1).

Stage not available in 4 patients (3%).

(Age-adjusted) International prognostic index not available in 33 patients (26%).

Patients were divided into two groups depending on their response to HDCT/ASCT. The first group included patients with r/r disease after ASCT. The second group comprised patients in ongoing remission without relapse of DLBCL. All patients gave written informed consent, and this analysis was approved by the local ethics committee of Bern, Switzerland.

Data source

Clinical data for this study were collected from the local electronic patient information system at the University Hospital Bern. Furthermore, information was obtained from the local Management and Resource System for Stem Cell Transplantation (MARCELL), providing specific information on the stem cell transplantation procedures at the University Hospital Bern.

Methods and Definitions

At first diagnosis, patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor classification,30 and the international prognostic index (IPI) was used for risk stratification.31 Remission status was determined according to the revised response criteria of the international working group for malignant lymphoma before ASCT, 100 days after ASCT, and at annual follow-up.32 Response was classified as complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). CR was defined as complete disappearance of clinical lymphoma evidence and disease-related symptoms. PR was defined as a measurable disease reduction of at least 50% and no occurrence of new lesions. Patients with SD did not fulfill CR/PR or PD criteria. The occurrence of new lesions or the increase of previously reported tumor masses by more than 50% were defined as PD.32,33

The primary endpoints were overall survival and progression-free survival. PFS was defined as the time from ASCT until the first evidence of relapse/progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from ASCT until death from any cause.

Statistical analysis

PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival differences between subgroups were identified by the log-rank test. Univariate analysis was calculated for the factors: age at first diagnosis, transformed lymphoma vs. de novo origin, presence of B-symptoms at first diagnosis, bone marrow infiltration at first diagnosis, radiotherapy administered during first or second-line therapy, the interval between first-line therapy until relapse/progression, the performance of CD34+ cell positive selection, remission status at ASCT, the interval from ASCT to relapse/progression, number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and number of further therapies after post-ASCT relapse. P values of <0.05 were assumed to be statistically significant. All data were conducted with GraphPad Prism, and calculations were done by Excel.

Results

Patient characteristics

This study included 125 consecutive patients with DLBCL who received HDCT/ASCT either as first-line consolidation due to high-risk presentation or as salvage therapy for relapsed DLBCL. Clinical characteristics at first diagnosis are summarized in Table 1. 63% of the patients were male. The median age at first diagnosis was 58 years (range, 23–76 years). DLBCL NOS (not otherwise specified) was the most common lymphoma subtype (48%). B-symptoms at first diagnosis were present in 44 patients (35%), bone marrow infiltration and central nervous system infiltration were observed in 27 (22%) and 13 patients (10%), respectively.

Transformed lymphoma was present in 23 patients, with 16 (70%) being initially diagnosed with follicular lymphoma, five (22%) with CLL, and one patient (4%) each with marginal zone lymphoma or nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. 73% of the patients had advanced-stage disease with Ann Arbor stages III (29 pts; 24%) or IV (59 pts; 49%). IPI for risk stratification at first diagnosis was a high-intermediate risk in 35 patients (38%) and high risk in 27 patients (29%).

As described above, patients were distributed into two groups depending on the disease control (relapse or progression) after HDCT/ASCT. Both cohorts were comparable regarding age, gender, lymphoma subtypes, stages, and IPI at first diagnosis (Table 1).

Previous therapies before ASCT

Details on the treatment given before HDCT/ASCT are presented in Table 2. Patients had a median of two treatment lines before ASCT (range 1–3). Fifty-one patients (41%) received HDCT/ASCT after only one line of therapy due to high-risk presentation, 68 patients (55%) after two, and 6 patients (5%) after three lines of treatment. For first-line treatment, 93% of patients received the CHOP regimen, and 94% of CHOP chemotherapies were combined with rituximab.

Table 2.

Overview on therapies used in one to three previous lines before ASCT.

| Parameter | First line n (%) | Second line n (%) | Third line n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 125 (100) | 74 (59) | 6 (5) |

| Relapsed patients, n (%) | 53 (100) | 40 (75) | 4 (8) |

| Non-relapsed patients, n (%) | 72 (100) | 34 (47) | 2 (3) |

| Chemotherapies | - | ||

| CHOP | 116 (93) | 2 (3) | - |

| DHAP | 6 (5) | 29 (39) | 5 (83) |

| DHAO | 2 (2) | 5 (7) | - |

| ESAP | - | 16 (22) | 1 (17) |

| ICE | 1 (1) | 11 (15) | - |

| EPOCH | 5 (4) | 4 (5) | - |

| MATRIX | 3 (2) | 4 (5) | - |

| Bendamustine | 3 (2) | 2 (3) | - |

| Others a | 6 (5) | 4 (5) | - |

| Combined with antibody treatment | 117 (94) | 70 (95) | 5 (83) |

| Rituximab | 117 | 68 | 5 |

| Others b | 0 | 2 | - |

| Radiotherapy | 19 (15) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

CHOP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, DHAP dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin, DHAO dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, oxaliplatin, ESAP etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, ICE ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide, EPOCH etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophos-phamide, prednisone, MATRIX methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, rituximab.

Other chemotherapies used: First line (n=6): unknown (n=1), VCD bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone (n=1), ABVD doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (n=2), Hyper-CVAD cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone (n=1), CODOX cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin (n=1). Second line (n=4): GDP gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin (n=2), Hyper-CVAD (n=1), CODOX (n=1).

Other adjuvant antibodies used: ofatumumab (n=1), nivolumab (n=1).

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation

HDCT/ASCT was performed after a median interval of 8 months from the initial diagnosis. Conditioning regimens in 93% were either the BeEAM (59%) or BEAM (34%). 7% of patients received either melphalan alone or the combination of carmustine and thiotepa as conditioning treatment. Detailed information on HDCT and ASCT is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with or without relapsed/refractory disease after ASCT.

| Parameter | All patients n (%) | Relapsed patients n (%) | Non-relapsed patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 125 (100) | 53 (42) | 72 (58) |

| Interval first diagnosis – ASCT, months, median (range) | 8 (2–224) | 9 (2–81) | 7 (2–224) |

| CD34+ mobilization regimens | |||

| DHAO | 6 (5) | 6 (11) | 0 (0) |

| DHAP | 33 (26) | 17 (32) | 16 (22) |

| ICE | 11 (9) | 5 (9) | 6 (8) |

| ESAP | 10 (8) | 4 (6) | 6 (8) |

| Vinorelbine | 51 (41) | 16 (30) | 35 (49) |

| Others a | 14 (11) | 5 (9) | 9 (13) |

| Conditioning regimen | |||

| BEAM | 42 (34) | 16 (30) | 26 (36) |

| BeEAM | 74 (59) | 33 (62) | 41 (57) |

| Others b | 9 (7) | 4 (8) | 5 (7) |

| Transplanted stem cells, mean, x106 kg b.w. (range) | 3.83 (1.70–7.45) | 3.59 (1.96–7.00) | 3.99 (1.70–7.45) |

| Stem cell source d | |||

| Peripheral blood | 118 (94) | 51 (96) | 67 (93) |

| Bone marrow | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

ASCT autologous stem cell transplantation, HDCT high-dose chemotherapy, DHAO dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, oxaliplatin, DHAP dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin, ICE ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide, ESAP etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, BEAM carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan, BeEAM bendamustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan.

Others: Gemcitabine (n=7), R-IVAC rituximab, ifosfamide, etoposide, high-dose cytarabine (n=2), MATRIX methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, rituximab (n=1), DA-EPOCH-R dose adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, rituximab (n=1), CHOP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (n=2), cytarabine and methotrexate (n=1).

Other conditioning regimen used: Melphalan (n=1), Carmustine and Thiotepa (n=8).

Source of stem cells unknown in 6 patients (5%).

Salvage therapy at relapse/progression after HDCT/ASCT

Fifty-three patients (42%) developed relapse or progression after a median interval of 3 months from ASCT (range 1 to 145 months). Thirty-one patients - 58% of all patients with relapse/progression, respectively - received further therapies. Twenty-one patients were treated with one therapy line, and ten patients had two to four treatment lines for relapsing disease after ASCT, with a median of one therapy line (range 0 to 4 lines). 22 patients had no further therapy due to poor general condition or by the patient’s wish.

The following further therapies were administered: cytotoxic chemotherapy (25 patients), radiotherapy (five patients), second HDCT/ASCT (three patients), and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (three patients). Three patients received immunotherapy targeting PD-1 (nivolumab: two patients; pidilizumab: one patient), one patient had blinatumomab, five patients were given ibrutinib, and one patient received the antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin, as listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Therapies patients with relapsed or refractory disease received after ASCT.

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients with relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT, n (%) | 53 (100) |

| Lines of treatment, median (range) | 1 (0–4) |

| 0 | 22 |

| 1 | 21 |

| ≥2 | 10 |

| Type of therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 25 |

| GemOx | 5 |

| MATRIX | 2 |

| DHAP | 2 |

| Bendamustine | 8 |

| ICE | 2 |

| Others a | 6 |

| Additional radiotherapy | 6 |

| Additional antibodies b | 24 |

| 2 nd ASCT | 3 |

| Allogeneic SCT | 3 |

| Radiotherapy (Monotherapy) | 5 |

| Immunotherapy (Monotherapy) c | 5 |

| Kinase inhibitor (Ibrutinib) | 5 |

ASCT autologous stem cell transplantation, GemOx gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, MATRIX methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, rituximab, DHAP dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin, ICE ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide.

Other chemotherapies used: GDP gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin (n=2), CHOP cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (n=1), EPOCH etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (n=1), PRIMAIN high-dose methotrexate, rituximab, procarbazine (n=1), MTX methotrexate (n=1).

Adjuvant antibodies used: rituximab (n=21), obinutuzumab (n=1), blinatumomab (n=2).

Immunotherapies: nivolumab (n=2), brentuximab (n=1), pidilizumab (n=1), blinatumomab (n=1).

Outcome

Details on the outcome of the patients after HDCT/ASCT are depicted in Table 5. The median follow-up of the entire patient cohort was 26 months. Forty-four patients (35%) died after a median of six months (range 1–64), 35 (80% of the patients) due to disease progression, six due to therapy-related reasons (in five cases due to HDCT associated toxicities, and in one case related to subsequent allogeneic transplantation) and six from other causes.

Table 5.

Outcome of patients with or without relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT. Median follow up, overall survival, progression-free survival, state of remission, relapse and death.

| Parameter | All patients n (%) | Relapsed patients n (%) | Non-relapsed patients n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients n (%) | 125 (100) | 53 (42) | 72 (58) |

| Follow up, months, median (range) | 26 (1–174) | 9 (1–174) | 38 (3–107) |

| OS, months, median (range) | 26 (1–174) | 9 (1–174) | 38 (3–107) |

| PFS, months, median (range) | 19 (1–145) | 3 (1–145) | 38 (3–107) |

| State of remission prior to ASCT (day 0) | |||

| CR | 35 (28) | 10 (19) | 25 (35) |

| PR | 83 (66) | 39 (74) | 44 (61) |

| SD | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| PD | 5 (4) | 3 (6) | 2 (3) |

| State of remission after ASCT (day +100) | |||

| CR | 79 (63) | 21 (40) | 58 (81) |

| PR | 25 (20) | 11 (21) | 14 (19) |

| SD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| PD | 11 (9) | 11 (21) | 0 (0) |

| State of remission at last follow-up | |||

| CR | 74 (59) | 5 (9) | 69 (96) |

| PR | 3 (2) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| SD | 3 (2) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| PD | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Relapse after ASCT, n (%) | 53 (42) | 53 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Median time ASCT – relapse, months (range) | 3 (1–145) | ||

| Early relapse, n (%) | 43 (81) | ||

| Late relapse, n (%) | 10 (19) | ||

| Death, n (%) | 44 (35) | 41 (77) | 3 (4) |

| Interval from ASCT, months, median (range) | 6 (1–64) | 6 (1–64) | 6 (3–24) |

| Due to progression, n | 35 | 35 | 0 |

| Related to therapy, n | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Other causes, n a | 3 | 0 | 3 |

OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, CR complete remission, PR partial remission, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease.

Other causes: pneumonia (n=1), intracranial hemorrhage (n=1), infection of the CNS (n=1).

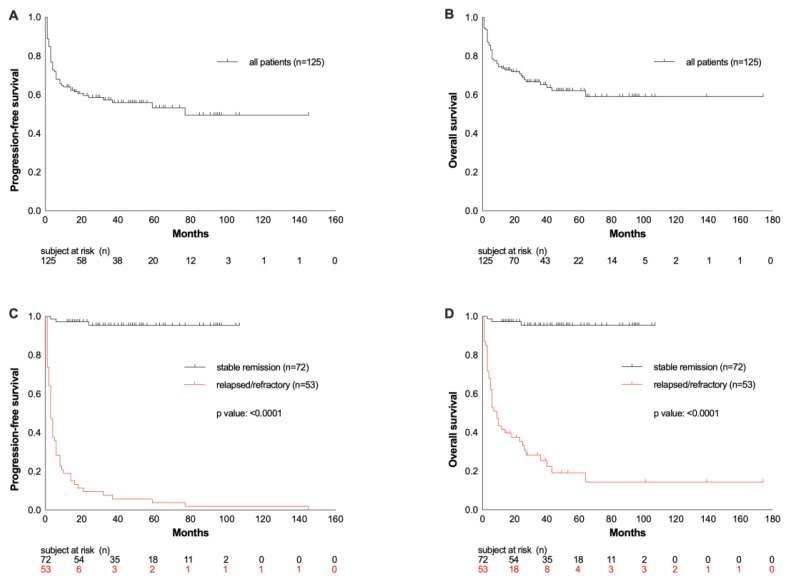

The median OS of the entire population was 26 months, and the OS rate at the last follow-up was 65% (Figure 1C). As expected, patients with r/r disease after ASCT had worse overall survival compared to patients in ongoing remission (OS at last follow-up: 23% vs. 96%; median OS: 9 vs. 38 months; p <0.0001; Figure 1D). Progression-free survival (PFS) of the entire cohort at the last follow-up was 55%, with a median duration of response of 19 months (Figure 1A). Relapsed or refractory disease occurred in 42% of patients after a median interval of 3 months.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from ACST represented as the whole cohort of patients (A and B) and compared according to their response to ASCT (C and D).

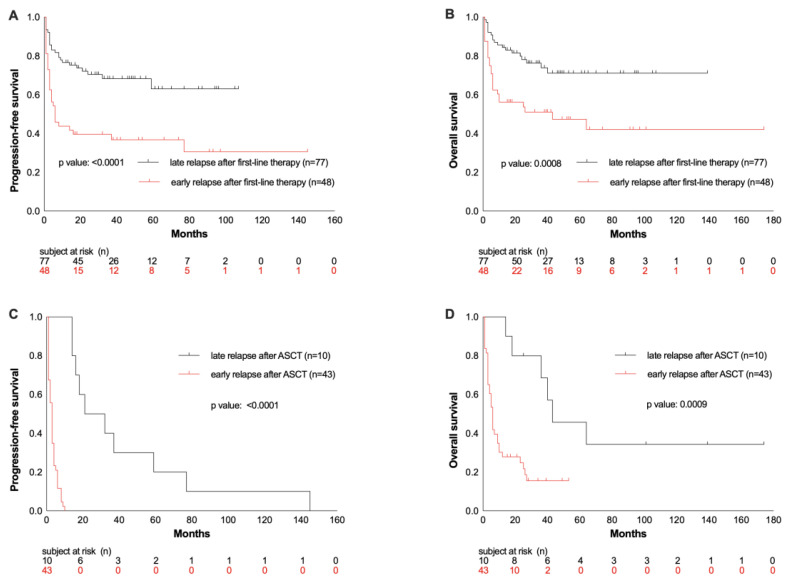

Four factors were identified to be associated with survival rates: interval of relapse from first-line therapy and interval from HDCT/ASCT, number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and the number of treatment lines after post-ASCT relapse. 38% of patients showed an early relapse after first-line therapy, defined as relapsed disease or progression within the first year. These patients had inferior OS and PFS compared to patients who relapsed after 12 months or later (OS rate at 26 months: 48% vs. 75%, p = 0.0008; PFS rate: 33% vs. 69%, p < 0.0001; Figure 3A/B).

Figure 3.

PFS and OS from ASCT depending on the time of relapse after first-line therapy (A and B) or after ASCT (C and D).

When only patients with r/r disease (n=53) following HDCT/ASCT were considered, early relapse or progression within the first 12 months after ASCT occurred in 81% of these patients. 19% of the patients had a late-onset relapse (an occurrence of relapse ≥ 12 months after ASCT). Patients with early relapse or progression had lower OS than patients with late onset of relapse post-ASCT (OS rate at 26 months: 19% vs. 40%, p= 0.0009, Figure 3D).

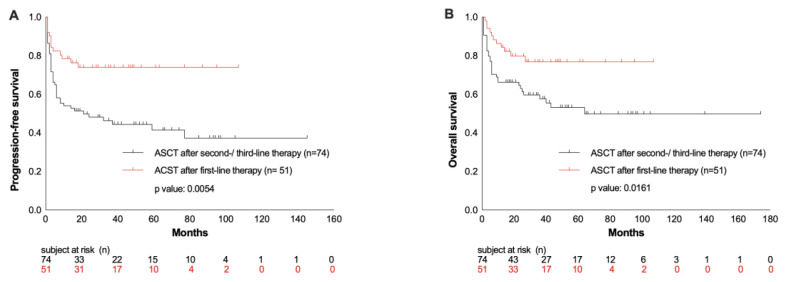

Comparing the patients’ outcome regarding the number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, a significant benefit was observed in those patients who received HDCT/ASCT after the first-line therapy because of high-risk presentation (n= 51), compared to those patients who had two to three lines of treatment prior to HDCT/ASCT (OS rate at 26 months: 78% vs. 55%, p= 0.0161; PFS rate: 75% vs. 42%, p= 0.0054; Figure 4 A/B).

Figure 4.

PFS and OS from ASCT depending on number of therapy lines prior to HDCT/ACST (A and B).

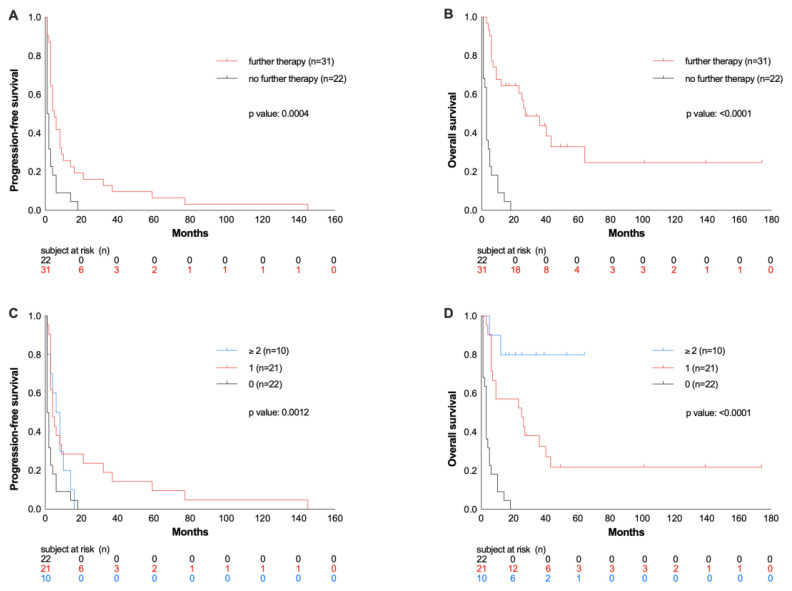

Considering all patients with r/r disease following HDCT/ASCT, the OS rate was only 23% after a median follow-up of 26 months after ASCT. Patients who received no other therapy despite relapse/progression after ASCT due to poor general condition or according to the patient’s wish had an even worse outcome compared to patients with additional treatment line(s) in this situation (OS rate at 26 months 0% vs. 39%, p >0.0001, Figure 2A). 42% of patients received no further therapy, 40% were treated with one, and 19% with two or more therapy lines, corresponding to OS rates of 0% vs. 24% vs. 70% (p> 0.0001; Figure 2B). Thus, in relapsed patients, the OS was longer with an increasing number of therapy lines.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from ASCT in patients with relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT depending on receiving further therapies or not (A and B) and on number on subsequent therapy lines (C and D).

No differences were detected in OS and PFS rates of specific subsets when data were adjusted for the following variables: de novo versus transformed lymphoma (OS p=0.7369; PFS p=0.7909), age higher/lower than 60 years (OS p= 0.3617; PFS p= 0.2655), B-symptoms present at first diagnosis yes/no (OS p=0.9446; PFS p=0.7619), bone marrow infiltration present at first diagnosis yes/no (OS p=0.6139; PFS p=0.3870), radiotherapy administered before ASCT yes/no (OS p=0.4674; PFS p=0.8150), and CR at ASCT yes/no (OS p=0.4271; PFS p=0.1398) (Supplementary material, Figure S1).

Discussion

Considering the introduction of CAR-T cell therapies for aggressive lymphatic malignancies in Europe and elsewhere,24,25 we aimed to further characterize the outcomes of patients with DLBCL with a specific focus on those with failure after HDCT/ASCT. We retrospectively investigated a cohort of 125 patients with DLBCL treated with HDCT/ASCT in a single academic/tertiary center and studied, in particular, the subset of patients who relapsed or developed progression following HDCT/ASCT and who could have benefited from CAR-T therapy, had it then been available.

Confirming reports by others, the present study demonstrates that HDCT, followed by ASCT, provides excellent long-term outcomes in patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL, achieving stable remission after this salvage therapy option.9,34,35 In our analysis comprising 125 recipients of HDCT/ASCT due to relapsed DLBCL or high-risk presentation, the ORR was 61% for the total cohort. That 55% of patients in ongoing remission following HDCT/ASCT showed encouraging OS and PFS of 96% with a median duration of 38 months.

In contrast, the prognosis for patients with r/r disease after HDCT/ASCT is poor, especially in those with characteristics such as high IPI or early relapse within 12 months following ASCT.11,34 In our study, 42% of patients developed relapses or showed progression after HDCT/ASCT. Although 58% of these patients with failure of HDCT/ASCT received other therapeutic approaches, 77% rapidly died after a median interval of 6 months, mostly due to lymphoma progression. Likewise, in the CORAL study, 29% of patients with r/r DLBCL after ASCT had poor survival, with a median OS of 10 months and a 1-year OS of 39.1%.35

We evaluated the impact of various parameters on the outcomes of our HDCT/ASCT cohort. Significant impact on survival could only be verified for the duration of the response to first-line therapy, the duration of response after HDCT/ASCT, the number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and the number of subsequent therapies after post-ASCT relapse. We documented a median interval to progression following ASCT of only 3 months, and 81% of relapses occurred within 12 months after ASCT, demonstrating that DLBCL relapses are associated with rapid kinetics, early manifesting after HDCT/ASCT. Furthermore, the OS rate was only 19% in patients with early relapses (<12 months) post-ASCT, as compared to late relapses (≥12 months after ASCT) with an OS rate of 40%. These results correspond with previous studies demonstrating early relapses following ASCT in 65–80% of patients, associated with a significantly worse OS compared to later time points of relapse.12,36 Other parameters such as the histopathological origin (transformed vs. de novo DLBCL)37–41 and CD34+ selection42–45 had no significant impact on the prognosis of the recipients of HDCT/ASCT in our cohort.

Treatment options for patients with r/r DLBCL following ASCT were so far limited. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation may provide a certain graft versus lymphoma effect.46–48 However, only a few DLBCL patients are, in fact, candidates for this approach due to its high transplant-related mortality and high relapse rates. Only three patients in our cohort received an allogeneic SCT, which is representative of the limited use of this option for r/r DLBCL patients.

CAR-T cell therapies, recently introduced, offer patients with r/r DLBCL a promising new option with CR rates of up to 58%.24,49,50 In several studies, ORR of 52–85% with 40–58% CR rates were achieved by CAR-T cell therapy in patients with r/r DLBCL.21,24–26,51,52 However, long-term outcomes will still be awaited in the next decades.

In addition, novel immunotherapies such as polatuzumab vedotin,53 tafasitamab,54 glofitamab, or mosunetuzumab are additional promising new options for DLBCL patients ineligible for HDCT/ASCT or for those whom CAR-T therapy is no option due to its toxicity, or due to its logistic or financial obstacles.

An obvious limitation of our study is its retrospective single-center design covering a large timespan, including various DLBCL subtypes, heterogeneity in conditioning regimen, and inevitable lack of some data in a few patients. Nevertheless, our study demonstrates the adverse prognosis of DLBCL patients after HDCT/ASCT failure and the limited efficacy of subsequent therapeutic approaches, including a second HDCT/ASCT, allogeneic SCT, radiation, cytotoxic treatment, and traditional monoclonal antibody therapies. Our study emphasizes the urgent need to make CAR-T cell therapies available to all patients with r/r DLBCL following HDCT/ASCT failure.21

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1.Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Österborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):379–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027–5033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilly H, Gomes da Silva M, Vitolo U, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Supplement 5):vii78–vii82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A study by the groupe d’etude des lymphomes de l’adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4117–4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP Chemotherapy plus Rituximab Compared with CHOP Alone in Elderly Patients with Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coiffier B, Sarkozy C. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: R-CHOP failure-what to do? Hematology. 2016;2016(1):366–378. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation as Compared with Salvage Chemotherapy in Relapses of Chemotherapy-Sensitive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;333(23):1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/nejm199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camus V, Tilly H. Managing early failures with R-CHOP in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(12):1047–1055. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2016.1254547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisselbrecht C, Van Den Neste E. How I manage patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(5):633–643. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagle SJ, Woo K, Schuster SJ, et al. Outcomes of patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with progression of lymphoma after autologous stem cell transplantation in the rituximab era. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(10):890–894. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedberg JW. Relapsed / Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Am Soc Hematol. pp. 498–505. Published online 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gilli S, Novak U, Taleghani BM, et al. BeEAM conditioning with bendamustine-replacing BCNU before autologous transplantation is safe and effective in lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(3):421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2900-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prediletto I, Farag SA, Bacher U, et al. High incidence of reversible renal toxicity of dose-intensified bendamustine-based high-dose chemotherapy in lymphoma and myeloma patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(12):1923–1925. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betticher C, Bacher U, Legros M, et al. Prophylactic corticosteroid use prevents engraftment syndrome in patients after autologous stem cell transplantation. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39(1):97–104. doi: 10.1002/hon.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vose JM, Bierman PJ, Anderson JR, et al. Progressive disease after high-dose therapy and autologous transplantation for lymphoid malignancy: clinical course and patient follow-up. Blood. 1992;80(8):2142–2148. doi: 10.1182/blood.V80.8.2142.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson SP, Boumendil A, Finel H, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Efficacy in the rituximab era and comparison to first allogeneic transplants. A report from the EBMT Lymphoma Working Party. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(3):365–371. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eicher F, Mansouri Taleghani B, Schild C, Bacher U, Pabst T. Reduced survival after autologous stem cell transplantation in myeloma and lymphoma patients with low vitamin D serum levels. Hematol Oncol. 2020;38(4):523–530. doi: 10.1002/hon.2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skrabek P, Assouline S, Christofides A, et al. Emerging therapies for the treatment of relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):253–265. doi: 10.3747/co.26.5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sermer D, Brentjens R. CAR T - cell therapy: Full speed ahead. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(S1):95–100. doi: 10.1002/hon.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavez JC, Locke FL. A Possible Cure for Refractory DLBCL: CARs Are Headed in the Right Direction. Mol Ther. 2017;25(10):2241–2243. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lekakis LJ, Moskowitz CH. The Role of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in the Treatment of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma in the Era of CAR-T Cell Therapy. HemaSphere. 2019;3(6) doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;380(1):45–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2531–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. The Lancet. 2020;396(10254):839–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titov A, Petukhov A, Staliarova A, et al. The biological basis and clinical symptoms of CAR-T therapy-associated toxicites. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9) doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0918-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bishop MR, Maziarz RT, Waller EK, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients without measurable disease at infusion. Blood Adv. 2019;3(14):2230–2236. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pabst T, Joncourt R, Shumilov E, et al. Analysis of IL-6 serum levels and CAR T cell-specific digital PCR in the context of cytokine release syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2020;88:7–14.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin’s Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res. 1971;31(11):1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziepert M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, et al. Standard international prognostic index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive CD20 + B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2373–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130(16):1800–1808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Den Neste E, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous stem cell transplantation: An analysis of patients included in the CORAL study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(2):216–221. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González-Barca E, Boumendil A, Blaise D, et al. Outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who relapse after autologous stem cell transplantation and receive active therapy. A retrospective analysis of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation ( Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(2):393–399. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner-Johnston ND, Link BK, Byrtek M, et al. Outcomes of transformed follicular lymphoma in the modern era: a report from the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS) Blood. 2015;126(7):851–857. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-621375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorigue M, Garcia O, Baptista MJ, et al. Similar prognosis of transformed and de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in patients treated with immunochemotherapy. Med Clínica Engl Ed. 2017;148(6):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.medcle.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghesquières H, Berger F, Felman P, et al. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Outcome of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas Presenting With an Associated Low-Grade Component at Diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5234–5241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guirguis HR, Cheung MC, Piliotis E, et al. Survival of patients with transformed lymphoma in the rituximab era. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(6):1007–1014. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1991-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montoto S, Fitzgibbon J. Transformation of Indolent B-Cell Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(14):1827–1834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger MD, Branger G, Leibundgut K, et al. CD34+ selected versus unselected autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with advanced-stage mantle cell and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2015;39(6):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gribben JG, Freedman AS, Neuberg D, et al. Immunologic Purging of Marrow Assessed by PCR before Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation for B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(22):1525–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111283252201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharp JG, Kessinger A, Mann S, et al. Outcome of high-dose therapy and autologous transplantation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma based on the presence of tumor in the marrow or infused hematopoietic harvest. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):214–219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams CD, Goldstone AHRM, Pearce RM, Philip T, Hartmann O, Colombat P, Santini G, Foulard LCGN. Purging of bone marrow in autologous bone marrow transplantation for non-Hodkin’s lymphoma: a case-matches comparsion with unpurged cases by the European Blood and Marrow Transplant Lymphoma Registry. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2454–2464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klyuchnikov E, Bacher U, Kroll T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Who, when and how. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doocey RT, Toze CL, Connors JM, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory aggressive histology non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2005;131(2):223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Kampen RJW, Canals C, Schouten HC, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation as salvage therapy for patients with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma relapsing after an autologous stem-cell transplantation: An analysis of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1342–1348. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abramson JS, Gordon LI, Palomba ML, et al. Updated safety and long term clinical outcomes in TRANSCEND NHL 001, pivotal trial of lisocabtagene maraleucel (JCAR017) in R/R aggressive NHL. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):7505–7505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.7505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kochenderfer JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, et al. Lymphoma Remissions Caused by Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Are Associated With High Serum Interleukin-15 Levels. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1803–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA-1: A Multicenter Study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T Cell Therapy in Refractory Aggressive Lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):155–165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salles G, Duell J, González Barca E, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):978–988. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.