Abstract

Background And Objectives

Several infections and vaccinations can provoke immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) onset or relapse. Information on ITP epidemiology and management during the Covid-19 pandemic is scarce. In a large monocenter ITP cohort, we assessed the incidence and risk factors for: 1) ITP onset/relapse after Covid19 vaccination/infection; 2) Covid19 infection.

Methods

Information on the date/type of anti-Covid-19 vaccine, platelet count before and within 30 days from the vaccine, and date/grade of Covid-19 was collected via phone call or during hematological visits. ITP relapse was defined as a drop in PLT count within 30 days from vaccination, compared to PLT count before vaccination that required a rescue therapy OR a dose increase of an ongoing therapy OR a PLT count <30 ×109/L with ≥20% decrease from baseline.

Results

Between February 2020 and January 2022, 60 new ITP diagnoses were observed (30% related to Covid-19 infection or vaccination). Younger and older ages were associated with a higher probability of ITP related to Covid19 infection (p=0.02) and vaccination (p=0.04), respectively. Compared to Covid-19-unrelated ITP, Infection- and vaccine-related ITP had lower response rates (p=0.03) and required more prolonged therapy (p=0.04), respectively. Among the 382 patients with known ITP at the pandemic start, 18.1% relapsed; relapse was attributed to Covid-19 infection/vaccine in 52.2%. The risk of relapse was higher in patients with active disease (p<0.001) and previous vaccine-related relapse (p=0.006). Overall, 18.3% of ITP patients acquired Covid19 (severe in 9.9%); risk was higher in unvaccinated patients (p<0.001).

Conclusions

All ITP patients should receive ≥1 vaccine dose and laboratory follow-up after vaccination, with a case-by-case evaluation of completion of the vaccine program if vaccine-related ITP onset/relapse and with tempest initiation of antiviral therapy in unvaccinated patients.

Keywords: Immune Thrombocytopenia, COVID19, vaccine, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

In December 2019, the first case of a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) related to a new virus was described in Wuhan, China.1 The SARS-CoronaVirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus that causes this infection was quickly isolated in Italy.2 The Coronavirus-2019 disease (COVID-19) is characterized by a plethora of symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic forms to flu-like syndromes, severe pneumonia, or intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalizations.3

Soon during the first months of the pandemic, an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and thrombocytopenia was observed.4 The mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 induces thrombocytopenia include direct virus damage to bone marrow hematopoietic cells, drug-induced hematological toxicity, and autoimmune mechanism.5,6 Notably, the platelet count drop during SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with a worse outcome in terms of 28-day, 90-day, and 180-day survival in hospitalized patients.7

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disease characterized by an isolated low platelet count (below 100×109/L).8 It can be triggered by any immunologic stimulus, including infections, drugs, and vaccinations.9 ITP therapy is required when the platelet count drops below 20–30×109/L or, in any case, of increased risk of bleeding. High-dose corticosteroids are the recommended first-line therapy in virtually all patients. Second-line, multiple options are available but require individual evaluation.10,11

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has represented an additional challenge for the management of ITP patients.

To decrease immunosuppression, potentially favoring SARS-CoV-2 infection, the American Society of Hematology panel of experts recommended using front-line corticosteroids at the lowest effective dose to achieve a safe platelet count, with early use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs).12 These indications were also accepted in Italy.13

In January 2021, the worldwide vaccination campaign began. In Italy, four vaccine sera were administered to ITP patients. The mRNA-BNT162b2 (Comirnaty, Pfizer/BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Spikevax, Moderna) vaccines are lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated, nucleoside-modified mRNA-based vaccines that encode the full-length Spike protein and the SARS-CoV-2 S-2P antigen, respectively.14,15 ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Vaxzeria, AstraZeneca) and the Ad26.COV2.S (Jcovden, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson) are viral vector vaccines.16,17

It is acknowledged that several vaccines can rarely induce ITP.18 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been associated with the onset or relapse of ITP.19 In addition, Lee et al. reported that ITP patients treated with >5 lines and/or splenectomy were more prone to relapse after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.20 Similarly, Visser et al. reported a higher risk of ITP relapse in patients with a platelet count <50×109/L and ongoing therapy during the vaccination.21

During the last years, many cases of ITP onset and relapse after SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination have been described.22–33 However, study cohorts on ITP management during the pandemic, both in terms of treatment optimization and risk of ITP occurrence/relapse following SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination, are scarce. In a large monocenter cohort of ITP patients, we aimed to assess: 1) incidence of new cases of ITP following anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and infection, risk factors, and outcomes; 2) incidence of ITP relapses following anti-SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination and risk factors; 3) incidence and risk factors for Covid19.

Material And Methods

Patients and study design

This observational retrospective cohort study (ITP-2011-02) was promoted by the IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy. The ITP-2011-02 study involves 1142 ITP patients diagnosed at our Hematology Center between January 1982 and January 2022. After IRB approval, diagnostic and follow-up information about adult ITP patients was derived from medical files and reported by data input into an electronic database developed to record all study data after de-identifying the patients with an alphanumeric code to protect personal privacy.

Data collected included patient demographics, medications, clinical/laboratory tests at diagnosis and during follow-up, type of ITP therapies and responses, hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications, death, and causes of death. All information about concomitant diseases and drug usage was recorded in each case history and used for this retrospective evaluation thereafter. Any treatment decision was at the physician’s discretion, independently from participation in this study.

All patients were followed until death or to the data cut-off date (July 2022).

For this analysis, specific information about SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations (i.e., date of vaccination, type of vaccine, any adverse events, platelet counts prior to and within 30 days after vaccination), and SARS-CoV-2 infection occurring between February 2020 and July 2022 (date, severity, platelet count during and within 30 days after infection resolution) were collected. The causal link between infection/vaccine and the onset of ITP was based on the time interval between these Covid19-related events and the occurrence/recurrence of ITP. A maximum time interval of 30 days was chosen according to published papers showing that the onset of ITP generally occurs 1–2 weeks after infections/vaccinations, with some cases arising up to 4 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine administration.21–34

Waves of the COVID-19 pandemic were divided into four periods, according to the type of predominant circulating variants in Europe: first (wild-type variant, February–June 2020); second (alpha/beta/gamma variants, July 2020–June 2021); third (delta variant, July 2021–January 2022); fourth (omega variant, since January 2022).35

Definitions

ITP diagnosis and response to treatments were defined according to International Working Group (IWG)-ITP criteria.8

New diagnoses of ITP were defined as inf-ITP or vax-ITP when they occurred within 30 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination, respectively. Relapses from ITP were deemed associated with infection or vaccination if they occurred within 30 days after these events. ITP relapse was defined as a platelet count drop requiring the start of new ITP therapy or a dose increase of the ongoing therapy, or any platelet count drop below 30×109/L and ≥20% from baseline even in the absence of treatment start/modification. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated at the start of the pandemic.36 Active ITP was defined as the presence of a platelet count <100×109/L and/or ongoing therapy for ITP.

Ethical aspects

The ITP-2011-02 study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the IRB of our Institution and the standards of the Helsinki Declaration. All patients provided written informed consent. The promoter of this study was the IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, which obtained approval from the Area Vasta Emilia Centro (AVEC) Ethics Committee (Approval file number: 032/2012/O/Oss). The study has no commercial support.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was carried out at the biostatistics laboratory of the MPN/ITP Unit, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna.

Comparisons of quantitative variables between groups of patients were carried out by the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, and the association between categorical variables was tested by the ÷2 test. The following risk factors related to relapse were investigated: male sex, age, CCI ≥1, autoimmune diseases, active ITP (platelet count <100×109/L and/or ongoing therapy), previous splenectomy, and relapse after previous SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

The following risk factors associated with the occurrence of Covid-19 were studied: male sex, age, CCI ≥1, autoimmune disease, completion of the vaccine course with two doses, and previous splenectomy.

Cumulative incidence of Covid-19 was identified, considering death as a competing risk, from the pandemic start to the first infection/last contact (Fine and Gray model).

Results

Study cohort

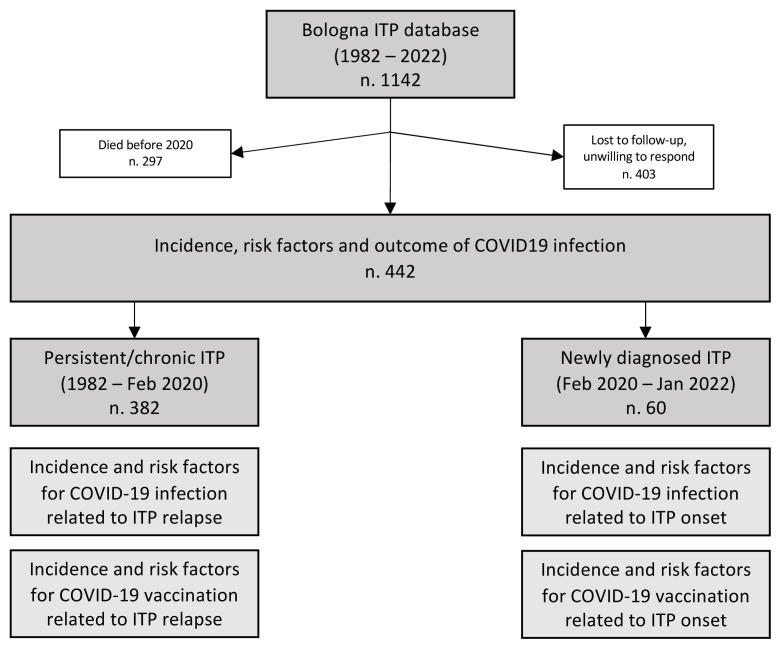

Among the 1142 ITP patients present in the ITP-2011-02 database, 297 patients were excluded because they died before the pandemic (February 2020). Of the remaining 845 patients, the diagnosis of ITP occurred before February 2020 in 785 patients; 403 (51.3%) were untraceable or refused to answer our questions. Therefore, 382 patients with ITP diagnosis before the pandemic onset remained evaluable for the present analysis. Sixty additional patients were diagnosed with ITP during the pandemic (between February 2020 and January 2022) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study cohort and aims.

Incidence and risk factors of newly diagnosed ITP during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

From February 2020 to January 2022, 60 patients received a diagnosis of ITP (28, 46.7%, during the first year of the pandemic). All these 60 patients were followed for at least 6 months after ITP diagnosis.

Five of these diagnoses (8.3%) were attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection (inf-ITP) and 13 (21.7%) to vaccination (vax-ITP): 7 after mRNA-BNT162b2, 3 after mRNA-1273 and 3 after ChAdOx1-S. Four patients were diagnosed with vax-ITP after their first dose of vaccine, 4 after the second and 5 after the first booster dose.

In univariate analysis, only a younger age was associated with a higher risk of inf-ITP, with a median age of 41.9 years versus 70.2 years in patients with ITP unrelated to Sars-CoV-2 infection (p=0.02). The remaining risk factors were not associated with inf-ITP, including male sex (40% of inf-ITP patients versus 45.5%, p=0.6), CCI ≥1 (20% of inf-ITP patients versus 25.5%, p=0.63), other autoimmune diseases (0% of inf-ITP patients versus 12.7%, p=0.52).

Conversely, only older age was associated with a higher risk of vax-ITP (median age 74 versus 55.9, p=0.04). Male sex (OR: 3.48 [0. 85–14.27], p=0.08), CCI ≥1 (OR: 2.3 [0.62–8.64], p=0.21), and presence of other autoimmune diseases (OR: 3.2 [0.62–16.75], p=0.16) were not associated to vax-ITP.

Response to therapy of newly diagnosed ITP according to relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection/vaccination

Among the 60 newly diagnosed ITP patients, 54 (90%) received ITP therapy in the first 6 months from diagnosis. First-line therapy was prednisone in all patients (dosage of 0.5–1 mg/kg for 21 days, with tapering and discontinuation in about 2–4 weeks).

Overall, 36 patients (66.7%) had a complete response, 12 patients (22.2%) had a response, and 6 patients (11.1%) had no response.

Second-line therapy was required in 24 (66.6%) patients, namely TPO-RAs (79.2%) and corticosteroids (20.8%). Seven patients (29.1%) required third-line therapy (71.4% TPO-RAs and 28.6% corticosteroids). A fourth-line therapy was administered to 3 patients (42.8%). The median duration of days spent on therapy was 55.5 days (range 0–180). Six months after diagnosis, 18 patients were still in therapy.

All five inf-ITP patients received first-line therapy with steroids. Compared with other patients diagnosed during the pandemic, the inf-ITP patients achieved less frequently a platelet response to the first line (p=0.03), with comparable rates of complete responses (p= 0.74), the median number of lines of therapy (p=0.75), duration of therapy (p=0.42), patients on therapy after 6 months of disease (p=0.51).

Out of 13 vax-ITP patients, 11 (84.6%) required corticosteroids. Compared with other patients diagnosed during the pandemic, no differences in terms of response to the first line (p=0.19), complete response to the first line (p=0.81), and the number of lines of therapy (p= 0.06) were observed. However, vax-ITP patients required more prolonged therapy (p= 0.04). Also, 63.6% of vax-ITP patients were still on therapy 6 months after diagnosis (p= 0.02) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Responses to front-line corticosteroids and number/duration of treatments during the first 6 months after diagnosis in newly diagnosed ITP patients, according to relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection (upper table) and vaccination (lower table). In all patients who required therapy, corticosteroids were used first-line and started at the same time as the diagnosis of ITP.

| inf-ITP (n.5) | no inf-ITP (n.55) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients receiving front-line corticosteroids, n. (%) | 5/5 (100%) | 49/55 (89.1%) | 0.43 |

| Overall response (CR+R), n. (%) | 3/5 (60.0%) | 45/49 (91.9%) | 0.03 |

| CR, n. (%) | 3/5 (60%) | 33/49 (67.3%) | 0.74 |

| Lines of ITP therapies, median (range), n. | 1 (1–3) | 1 (0–5) | 0.75 |

| Duration of ITP therapies, median (range), days | 45 (31–149) | 56 (0–180) | 0.42 |

| Patients with ongoing ITP therapy after 6 months from therapy start, n. (%) | 1/5 (20%) | 17/49 (34.7%) | 0.51 |

| vax-ITP (n.13) | no vax-ITP (n.47) | p value | |

| Patients receiving front-line corticosteroids, n. (%) | 11/13 (84.6%) | 43/47 (91.5%) | 0.47 |

| Overall response (CR+R), n. (%) | 11/11 (100%) | 37/43 (86.0%) | 0.19 |

| CR, n. (%) | 7/11 (63.5%) | 29/43 (67.4%) | 0.81 |

| Lines of ITP therapies, median (range), n. | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–5) | 0.06 |

| Duration of ITP therapies, median (range), days | 150 (0–180) | 54 (0–180) | 0.04 |

| Patients with ongoing ITP therapy after 6 months from therapy start, n. (%) | 7/11 (63.6%) | 11/43 (25.6%) | 0.02 |

CR: Complete Response; R: Response.

Incidence of relapsed ITP and correlation with SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccine

Overall, 382 patients with an ITP diagnosed before the pandemic onset were evaluable for this analysis, and 69 (18.1%) had at least one relapse between February 2020 and January 2022.

360 (94.2%), 342, and 313 patients received the first, second, and booster dose of the vaccine, respectively. The distribution of vaccine types and tolerability is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of vaccine types and them adverse events presented in at least 1% of ITP patients diagnosed before pandemic.

| Vaccination | Patient, n. (%) | Overall, n. (%) | Arm Pain, n. (%) | Fever, n. (%) | Fatigue, n. (%) | Headache, n. (%) | Arthromyalgia, n. (%) | Gastrointestinal disorders, n. (%) | Lymphoadenomegaly, n. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Vaccine type received at 1° dose | 360 (100) | 113 (31.3) | 52 (14.4) | 35 (9.7) | 22 (6.1) | 11 (3.1) | 7 (1.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| mRNA-BNT162b2 [Pfizer] | 272 (75.6) | 78 (28.6) | 40 (14.7) | 20 (7.3) | 13 (4.8) | 7 (2.6) | 5 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| mRNA-1273 [Moderna] | 50 (13.8) | 21 (42.0) | 9 (18.0) | 8 (16.0) | 7 (14.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ChAdOx1-S [Astra Zeneca] | 33 (9.2) | 14 (42.4) | 3 (9.1) | 7 (21.2) | 2 6.1) | 3 (9.0) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) |

| Ad26-COV2-S [Johnson & Johnson] | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||||||||

| Vaccine type received at 2° dose | 342 (100) | 121 (35.4) | 47 (13.7) | 44 (12.9) | 23 (6.7) | 14 (4.1) | 12 (3.5) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) |

| mRNA-BNT162b2 | 266 (77.8) | 93 (35.0) | 38 (14.3) | 33 (12.4) | 18 (6.8) | 11 (4.1) | 8 (3.0) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) |

| mRNA-1273 | 46 (13.4) | 22 (47.8) | 6 (13.0) | 10 (21.7) | 4 (8.7) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) |

| ChAdOx1-S | 30 (8.8) | 6 (20) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||||||||

| Vaccine type received at booster | 313 (100) | 119 (38.0) | 43 (13.7) | 42 (13.4) | 24 (7.7) | 20 (6.4) | 16 (5.1) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| mRNA-BNT162b2 | 119 (38.0) | 36 (30.2) | 14 (11.7) | 9 (7.6) | 9 (7.6) | 5 (4.2) | 4 (3.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.84) |

| mRNA-1273 | 194 (62.0) | 83 (42.8) | 29 (14.9) | 33 (17.0) | 15 (7.7) | 15 (7.7) | 12 (6.2) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2.1) |

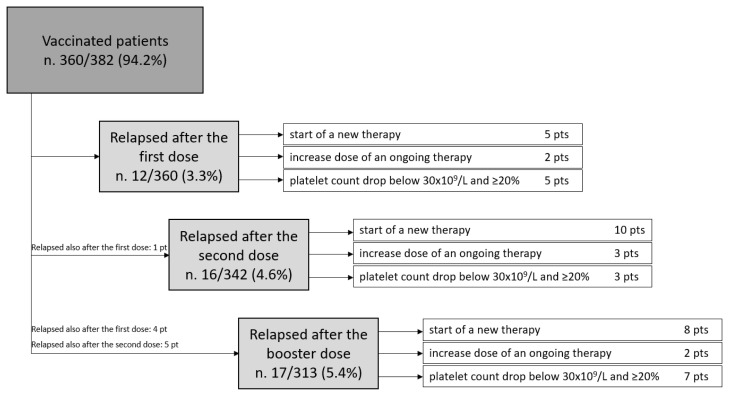

Relapse was attributed to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in 35 patients (50.7%) and to SARS-CoV-2 infection in 1 patient (1.5%). In 33 patients (47.8%), ITP relapse was independent of both conditions.

Out of 35 patients with a vaccine-related relapse, 10 had a second ITP relapse attributed to the vaccine, for a total of 45 observed relapses. Relapses were defined as reduced platelet count requiring the start of a new therapy (n. 23) or a dose increase of an ongoing therapy (n. 7), or platelet count drop below 30×109/L and ≥20% from baseline in the absence of treatment start/modification (n. 15). Only one patient experienced a grade 3 bleeding requiring hospitalization.

Vaccine-related relapses occurred in 12 (3.3%) cases after the first dose, in 16 cases (4.7%) after the second dose, and in 17 cases (5.4%) after the booster (p=0.3) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patients with ITP who experienced a relapse after < 30 days from Sars-CoV-2 vaccination.

After the first and the second dose, the only risk factor associated with relapse was an active disease (first dose: OR 10.81, CI 2.33–16.13, p 0.002; second dose: OR 6.99, CI 2.16–12.85, p=0.001). After the booster dose, the risk factors associated with relapse were active disease (OR 9.9, CI 2.90–16.88, p<0.001) and ITP relapse after a previous dose (OR 5.33, CI 1.84–17.87, p=0.007). These two factors remained associated with relapse in multivariable analysis (OR 17.42, CI 3.8–39.2, p<0.001 and OR 5.9, CI 1.7–21.3, p=0.006).

Incidence and risk factor for COVID-19 in ITP patients

Between February 2020 and July 2022, 81 out of the total cohort of 442 (18.3%) patients contracted the SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic in 16, 19.8%: mild in 47 patients, 58.0%; moderate in 10 patients, 12.3%; severe in 8 patients, 9.9%; no fatal cases).

Infections occurred during the first wave (3 patients, 3.7%; severe in one case), the second wave (25 patients, 30.9%; severe in 5 patients), and the third wave (37 patients, 45.7%; severe in two patients) and fourth wave (16 patients, 19.7%; no severe cases).

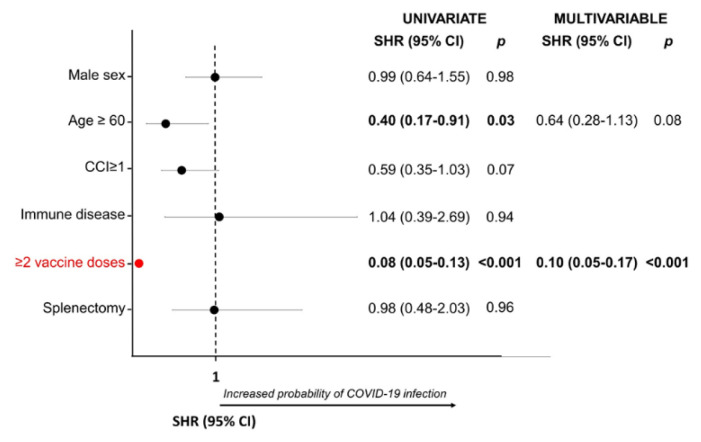

None of the patients who received at least one vaccine dose had a severe infection. Moreover, as the number of doses received increased, the frequency of infections decreased, with an incidence rate of infection of 0.55 per 100 patient-years in patients who did not receive any vaccine dose, 0.25 per 100 patient-years in patients who completed the first vaccine cycle, 0.04 per 100 patient-years in patients who received the booster dose (p <0.001).

In univariate analysis, age ≥60 years and the completion of the vaccine cycle were protective factors against the SARS-CoV-2 infection (SHR 0.4, p= 0.03 and SHR 0.08, p< 0.001, respectively). In multivariate analysis, only vaccine cycle completion was confirmed as a protective factor (SHR 0.1, p< 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk factor for COVID19 in ITP patients.

Discussion

We observed that almost 30% of newly diagnosed ITPs were related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (8.3%) or vaccination (21.3%). These data confirm that Covid-19 may play a role in the development of ITP in a significant, albeit minority, fraction of patients.

Among the risk factors for ITP onset evaluated, only age (younger if post-infection, older if post-vaccine) was shown to be significantly associated with the development of Covid-19-related ITP. In the absence of strong individual predictive factors (e.g., presence of immune disorders, comorbidities, gender), the recommendation to monitor platelet count in the general population only when signs or symptoms attributable to thrombocytopenia appear remains valid.37,38

Notably, during the first 6 months, vaccine-related ITPs required a median of 150 days of therapy compared to Covid-19-unrelated ITPs diagnosed in the same period that required a median time of 54 days, with equal treatment choices. This represents an important caveat about the possible greater management difficulties of such ITPs, which would therefore merit closer hematological monitoring and detailed patient information. Notably, Spike protein serology is often higher after the vaccine than in those infected and not vaccinated[39]. Greater stimulation by vaccination, compared with infection, might explain why patients with vax-ITP, but not those with inf-ITP, showed a shorter duration of response.

Second, we observed that SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was a significant trigger of ITP relapse in patients with persistent or chronic ITP, associated with over 50% of ITP relapses observed between February 2020 and January 2022. This association may be due to the activation of the immune system, mediated by the vaccine’s components. Indeed, the spike protein produced by signal translation, mRNA, excipients, lipid component, or viral capsid can stimulate B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, or complement40–44 and could configure an adjuvant-induced autoimmune syndrome.45,46 Among patients with pre-existing ITP, active disease, and previous vaccine-related relapse were significantly associated with ITP relapse following vaccination. Weekly platelet monitoring for 3–6 weeks is recommended in these patients after every vaccine dose.37 Overall, these results suggest that Covid 19 testing may be relevant in ITP diagnostic workup both for new and relapse.

Finally, we observed that 81 ITP patients had acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of them, about 10% required hospitalization, with two patients admitted to an ICU. As demonstrated in other hematological,47,48 or rheumatological diseases,49,50 although the incidence Covid-19 in ITP patients is not significantly increased compared with the general population,35 a severe infection seems to be more frequent.

This observation reinforces the indication to include patients with ITP among those at risk for Covid-19 infection, prioritizing vaccination and suggesting careful adherence to hygiene norms and timely swab screening if symptoms appear.

Notably, severe/critical Covid-19 infections occurred only in patients who had not yet received even one dose of vaccine. Therefore, these patients should receive immediate antiviral therapy in case of infection.

Limitations of this study are the retrospective nature of the data collection, with possible reduced accuracy of the data entered, the omission of relevant events, and the small cohort. Our results should be validated in larger cohorts.

Some ITP diagnoses and relapses may have escaped our Hematology Center because they were followed up in another center or by the general practitioner. Also, many patients were excluded from this cohort because they were untraceable.

Overall, the pandemic has complicated the management of ITP, both the vaccine and the infection being associated with a more aggressive disease onset but also with an increased risk of relapse, compared with a clear protective effect of the vaccine against severe infections.

While completing the vaccine program in case of previous ITP relapse requires case-by-case evaluation, all ITP patients should be encouraged to receive at least the first vaccine dose and appropriate laboratory follow-up after vaccination, with tempest initiation of antiviral therapy in unvaccinated patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1.Cyranoski D. New virus identified as likely cause of mystery illness in China. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capobianchi MR, Rueca M, Messina F, Giombini E, Carletti F, Colavita F, Castilletti C, Lalle E, Bordi L, Vairo F, Nicastri E, Ippolito G, Gruber CEM, Bartolini B. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 from the first case of COVID-19 in Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:954–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi Z-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:141–54. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahman A, Niloofa R, Jayarajah U, De Mel S, Abeysuriya V, Seneviratne SL. Hematological Abnormalities in COVID-19: A Narrative Review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104:1188–1201. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wool GD, Miller JL. The Impact of COVID-19 Disease on Platelets and Coagulation. Pathobiology. 2021;88:15–27. doi: 10.1159/000512007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu P, Zhou Q, Xu J. Mechanism of thrombocytopenia in COVID-19 patients. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:1205–8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-04019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Liu F, Zhou Q, Peng Z. Association between thrombocytopenia and 180-day prognosis of COVID-19 patients in intensive care units: A two-center observational study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Godeau B, Lechner K, Mazzucconi MG, McMillan R, Sanz MA, Imbach P, Blanchette V, Kühne T, Ruggeri M, George JN. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perricone C, Ceccarelli F, Nesher G, Borella E, Odeh Q, Conti F, Shoenfeld Y, Valesini G. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) associated with vaccinations: a review of reported cases. Immunol Res. 2014;60:226–35. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8597-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Gernsheimer T, Ghanima W, Godeau B, González-López TJ, Grainger J, Hou M, Kruse C, McDonald V, Michel M, Newland AC, Pavord S, Rodeghiero F, Scully M, Tomiyama Y, Wong RS, Zaja F, Kuter DJ. Updated international consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3780–3817. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold DM, Buchanan G, Cines DB, Cooper N, Cuker A, Despotovic JM, George JN, Grace RF, Kühne T, Kuter DJ, Lim W, McCrae KR, Pruitt B, Shimanek H, Vesely SK. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:3829–66. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.COVID-19 and ITP - Hematology.org [Internet] [Last accessed date: 2022 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.hematology.org:443/covid-19/covid-19-and-itp.

- 13.Rodeghiero F, Cantoni S, Carli G, Carpenedo M, Carrai V, Chiurazzi F, De Stefano V, Santoro C, Siragusa S, Zaja F, Vianelli N. Practical Recommendations for the Management of Patients with ITP During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13:e2021032. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2021.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, Perez JL, Pérez Marc G, Moreira ED, Zerbini C, Bailey R, Swanson KA, Roychoudhury S, Koury K, Li P, Kalina WV, Cooper D, Frenck RW, Hammitt LL, Türeci Ö, Nell H, Schaefer A, Ünal S, Tresnan DB, Mather S, Dormitzer PR, Şahin U, Jansen KU, Gruber WC C4591001 Clinical Trial Group. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D, Spector SA, Rouphael N, Creech CB, McGettigan J, Khetan S, Segall N, Solis J, Brosz A, Fierro C, Schwartz H, Neuzil K, Corey L, Gilbert P, Janes H, Follmann D, Marovich M, Mascola J, Polakowski L, Ledgerwood J, Graham BS, Bennett H, Pajon R, Knightly C, Leav B, Deng W, Zhou H, Han S, Ivarsson M, Miller J, Zaks T COVE Study Group. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emary KRW, Golubchik T, Aley PK, Ariani CV, Angus B, Bibi S, Blane B, Bonsall D, Cicconi P, Charlton S, Clutterbuck EA, Collins AM, Cox T, Darton TC, Dold C, Douglas AD, Duncan CJA, Ewer KJ, Flaxman AL, Faust SN, Ferreira DM, Feng S, Finn A, Folegatti PM, Fuskova M, Galiza E, Goodman AL, Green CM, Green CA, Greenland M, Hallis B, Heath PT, Hay J, Hill HC, Jenkin D, Kerridge S, Lazarus R, Libri V, Lillie PJ, Ludden C, Marchevsky NG, Minassian AM, McGregor AC, Mujadidi YF, Phillips DJ, Plested E, Pollock KM, Robinson H, Smith A, Song R, Snape MD, Sutherland RK, Thomson EC, Toshner M, Turner DPJ, Vekemans J, Villafana TL, Williams CJ, Hill AVS, Lambe T, Gilbert SC, Voysey M, Ramasamy MN, Pollard AJ COVID-19 Genomics UK consortium, AMPHEUS Project, Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Trial Group. Efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 20: 2012/01 (B.1.1.7): an exploratory analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1351–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, Goepfert PA, Truyers C, Fennema H, Spiessens B, Offergeld K, Scheper G, Taylor KL, Robb ML, Treanor J, Barouch DH, Stoddard J, Ryser MF, Marovich MA, Neuzil KM, Corey L, Cauwenberghs N, Tanner T, Hardt K, Ruiz-Guiñazú J, Le Gars M, Schuitemaker H, Van Hoof J, Struyf F, Douoguih M ENSEMBLE Study Group. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2187–2201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller E, Waight P, Farrington CP, Andrews N, Stowe J, Taylor B. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and MMR vaccine. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:227–29. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moulis G, Crickx E, Thomas L, Massy N, Mahévas M, Valnet-Rabier MB, Atzenhoffer M, Michel M, Godeau B, Bagheri H, Salvo F. De novo and relapsed immune thrombocytopenia after COVID-19 vaccines: results of French safety monitoring. Blood. 2022;139:2561–65. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee E-J, Beltrami-Moreira M, Al-Samkari H, Cuker A, DiRaimo J, Gernsheimer T, Kruse A, Kessler C, Kruse C, Leavitt AD, Lee AI, Liebman HA, Newland AC, Ray AE, Tarantino MD, Thachil J, Kuter DJ, Cines DB, Bussel JB. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and ITP in patients with de novo or pre-existing ITP. Blood. 2022;139:1564–74. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Visser C, Swinkels M, van Werkhoven ED, Croles FN, Noordzij-Nooteboom HS, Eefting M, Last-Koopmans SM, Idink C, Westerweel PE, Santbergen B, Jobse PA, Baboe F, Te Boekhorst PAW, Leebeek FWG, Levin M-D, Kruip MJHA, Jansen AJG RECOVAC-IR Consortium. COVID-19 vaccination in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2022;6:1637–44. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuter DJ. Exacerbation of immune thrombocytopenia following COVID-19 vaccination. Br J Haematol. 2021;195:365–70. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah SRA, Dolkar S, Mathew J, Vishnu P. COVID-19 vaccination associated severe immune thrombocytopenia. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10:42. doi: 10.1186/s40164-021-00235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsao HS, Chason HM, Fearon DM. Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) in a Pediatric Patient Positive for SARS-CoV-2. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20201419. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jawed M, Khalid A, Rubin M, Shafiq R, Cemalovic N. Acute Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) Following COVID-19 Vaccination in a Patient With Previously Stable ITP. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab343. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santhosh S, Malik B, Kalantary A, Kunadi A. Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) Following Natural COVID-19 Infection. Cureus. 2022;14:e26582. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch M, Fuld S, Middeke JM, Fantana J, von Bonin S, Beyer-Westendorf J. Secondary Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP) Associated with ChAdOx1 Covid-19 Vaccination - A Case Report. TH Open. 2021;5:e315–18. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Ahmad M, Al Rasheed M, Shalaby N, Rodriguez-Bouza T, Altourah L. Immune Thrombocytopenia (ITP): Relapse Versus de novo After COVID-19 Vaccination. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2022;28:10760296211073920. doi: 10.1177/10760296211073920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso-Beato R, Morales-Ortega A, Fernández FJD, la H, Morón AIP, Ríos-Fernández R, Rubio JLC, Centeno NO. Immune thrombocytopenia and COVID-19: Case report and review of literature. Lupus. 2021;30:1515–21. doi: 10.1177/09612033211021161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumura A, Katsuki K, Akimoto M, Sakuma T, Nakajima Y, Miyazaki T, Fujisawa S, Nakajima H. [Immune thrombocytopenia after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2021;62:1639–42. doi: 10.11406/rinketsu.62.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano C, Español I, Cascales A, Moraleda JM. Frequently Relapsing Post-COVID-19 Immune Thrombocytopenia. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021;3:2389–92. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-01019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashraf S, Alsharedi M. COVID-19 induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura: case report. Stem Cell Investig. 2021;8:14. doi: 10.21037/sci-2020-060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujita M, Ureshino H, Sugihara A, Nishioka A, Kimura S. Immune Thrombocytopenia Exacerbation After COVID-19 Vaccination in a Young Woman. Cureus. 2021;13:e17942. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Xu Z, Wang P, Li X-M, Shuai Z-W, Ye D-Q, Pan H-F. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology. 2022;165:386–401. doi: 10.1111/imm.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Infografica web - Dati della Sorveglianza integrata COVID-19 in Italia [Internet] [Last accessed date: 2022 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-dashboard.

- 36.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Stefano V, Marchetti M, Rossi E, Ruggeri M, Zaja F, Santoro C, Barcellini W, Carpenedo M, Palandri F, Risitano A, Vianelli N. Piastrinopenia Immune e vaccinazione anti-SARS-CoV-2: raccomandazioni. GIMEMA - SIE - SISET. 2021. Available from: https://www.gimema.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Piastropenia-immune-e-vaccinazione-anti-COVID-19-Raccomandazioni-GIMEMA-SIE-SISET-22-dec-21.pdf.

- 38.Welsh KJ, Baumblatt J, Chege W, Goud R, Nair N. Thrombocytopenia including immune thrombocytopenia after receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) Vaccine. 2021;39:3329–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tobolowsky FA, Waltenburg MA, Moritz ED, Haile M, DaSilva JC, Schuh AJ, Thornburg NJ, Westbrook A, McKay SL, LaVoie SP, Folster JM, Harcourt JL, Tamin A, Stumpf MM, Mills L, Freeman B, Lester S, Beshearse E, Lecy KD, Brown LG, Fajardo G, Negley J, McDonald LC, Kutty PK, Brown AC CDC Infection Prevention and Control Team. Longitudinal serologic and viral testing post-SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a nursing home cohort-Georgia, October 2020–April 2021. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0275718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portuguese AJ, Sunga C, Kruse-Jarres R, Gernsheimer T, Abkowitz J. Autoimmune- and complement-mediated hematologic condition recrudescence following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Blood Adv. 2021;5:2794–98. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boettler T, Csernalabics B, Salié H, Luxenburger H, Wischer L, Salimi Alizei E, Zoldan K, Krimmel L, Bronsert P, Schwabenland M, Prinz M, Mogler C, Neumann-Haefelin C, Thimme R, Hofmann M, Bengsch B. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can elicit a CD8 T-cell dominant hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:653–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chee YJ, Liew H, Hoi WH, Lee Y, Lim B, Chin HX, Lai RTR, Koh Y, Tham M, Seow CJ, Quek ZH, Chen AW, Quek TPL, Tan AWK, Dalan R. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination and Graves’ Disease: A Report of 12 Cases and Review of the Literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e2324–30. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klomjit N, Alexander MP, Fervenza FC, Zoghby Z, Garg A, Hogan MC, Nasr SH, Minshar MA, Zand L. COVID-19 Vaccination and Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:2969–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sattui SE, Liew JW, Kennedy K, Sirotich E, Putman M, Moni TT, Akpabio A, Alpízar-Rodríguez D, Berenbaum F, Bulina I, Conway R, Singh AD, Duff E, Durrant KL, Gheita TA, Hill CL, Howard RA, Hoyer BF, Hsieh E, El Kibbi L, Kilian A, Kim AH, Liew DFL, Lo C, Miller B, Mingolla S, Nudel M, Palmerlee CA, Singh JA, Singh N, Ugarte-Gil MF, Wallace J, Young KJ, Bhana S, Costello W, Grainger R, Machado PM, Robinson PC, Sufka P, Wallace ZS, Yazdany J, Harrison C, Larché M, Levine M, Foster G, Thabane L, Rider LG, Hausmann JS, Simard JF, Sparks JA. Early experience of COVID-19 vaccination in adults with systemic rheumatic diseases: results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Vaccine Survey. RMD Open. 2021;7:e001814. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoenfeld Y, Agmon-Levin N. “ASIA” - autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jara LJ, Vera-Lastra O, Mahroum N, Pineda C, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmune post-COVID vaccine syndromes: does the spectrum of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome expand? Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41:1603–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06149-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breccia M, Piciocchi A, Messina M, Soddu S, De Stefano V, Bellini M, Iurlo A, Martino B, Siragusa S, Albano F, Mora B, Fazi P, Vignetti M, Guglielmelli P, Palandri F. Covid-19 in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms: a GIMEMA survey on incidence, clinical management and vaccine. Leukemia. 2022;36:2548–50. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01675-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagano L, Salmanton-García J, Marchesi F, Busca A, Corradini P, Hoenigl M, Klimko N, Koehler P, Pagliuca A, Passamonti F, Verga L, Víšek B, Ilhan O, Nadali G, Weinbergerová B, Córdoba-Mascuñano R, Marchetti M, Collins GP, Farina F, Cattaneo C, Cabirta A, Gomes-Silva M, Itri F, van Doesum J, Ledoux M-P, Čerňan M, Jakšić O, Duarte RF, Magliano G, Omrani AS, Fracchiolla NS, Kulasekararaj A, Valković T, Poulsen CB, Machado M, Glenthøj A, Stoma I, Ráčil Z, Piukovics K, Navrátil M, Emarah Z, Sili U, Maertens J, Blennow O, Bergantim R, García-Vidal C, Prezioso L, Guidetti A, Del Principe MI, Popova M, de Jonge N, Ormazabal-Vélez I, Fernández N, Falces-Romero I, Cuccaro A, Meers S, Buquicchio C, Antić D, Al-Khabori M, García-Sanz R, Biernat MM, Tisi MC, Sal E, Rahimli L, Čolović N, Schönlein M, Calbacho M, Tascini C, Miranda-Castillo C, Khanna N, Méndez G-A, Petzer V, Novák J, Besson C, Duléry R, Lamure S, Nucci M, Zambrotta G, Žák P, Seval GC, Bonuomo V, Mayer J, López-García A, Sacchi MV, Booth S, Ciceri F, Oberti M, Salvini M, Izuzquiza M, Nunes-Rodrigues R, Ammatuna E, Obr A, Herbrecht R, Núñez-Martín-Buitrago L, Mancini V, Shwaylia H, Sciumè M, Essame J, Nygaard M, Batinić J, Gonzaga Y, Regalado-Artamendi I, Karlsson LK, Shapetska M, Hanakova M, El-Ashwah S, Borbényi Z, Çolak GM, Nordlander A, Dragonetti G, Maraglino AME, Rinaldi A, De Ramón-Sánchez C, Cornely OA EPICOVIDEHA working group. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European Hematology Association Survey (EPICOVIDEHA) J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:168. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyrich KL, Machado PM. Rheumatic disease and COVID-19: epidemiology and outcomes. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:71–72. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00562-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cordtz R, Lindhardsen J, Soussi BG, Vela J, Uhrenholt L, Westermann R, Kristensen S, Nielsen H, Torp-Pedersen C, Dreyer L. Incidence and severeness of COVID-19 hospitalization in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease: a nationwide cohort study from Denmark. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:SI59–67. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]