Abstract

One of the adverse outcomes of acute inflammatory response is progressing to the chronic stage or transforming into an aggressive process, which can develop rapidly and result in the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The leading role in this process is played by the Systemic Inflammatory Response that is accompanied by the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, acute phase proteins, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

The purpose of this review that highlights both the recent reports and the results of the authors' own research is to encourage scientists to develop new approaches to the differentiated therapy of various SIR manifestations (low- and high-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotypes) by modulating redox-sensitive transcription factors with polyphenols and to evaluate the saturation of the pharmaceutical market with appropriate dosage forms tailored for targeted delivery of these compounds.

Redox-sensitive transcription factors such as NFκB, STAT3, AP1 and Nrf2 have a leading role in mechanisms of the formation of low- and high-grade systemic inflammatory phenotypes as variants of SIR. These phenotypic variants underlie the pathogenesis of the most dangerous diseases of internal organs, endocrine and nervous systems, surgical pathologies, and post-traumatic disorders.

The use of individual chemical compounds of the class of polyphenols, or their combinations can be an effective technology in the therapy of SIR. Administering natural polyphenols in oral dosage forms is very beneficial in the therapy and management of the number of diseases accompanied with low-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype. The therapy of diseases associated with high-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype requires medicinal phenol preparations manufactured for parenteral administration.

Keywords: Polyphenols, Systemic inflammatory response, Transcriptional factors, Chronic low-grade inflammation, Water soluble forms of quercetin, Bioflavonoids, Stilbenes

1. Introduction

One of the adverse outcomes of acute inflammatory response is the progression to the chronic stage or transformation into an aggressive process, which can develop rapidly and result in the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The leading role in this process is played by the Systemic Inflammatory Response (SIR) that is accompanied by the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, acute phase proteins, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS).

The molecular mechanism of the SIR initiation and regulation is triggered by the activation of certain transcription factors (TFs) affecting the expression of dozens or hundreds of genes and encode proteins, which are capable to activate or inhibit this process. A lack of control mechanisms or intensified pathogenic stimulation can change dramatically intracellular signalling pathways, the activity of TFs, and the expression of primary genes that turns SIR into a dysfunctional system, which is devoid of a protective basis for the body.

Surplus activation of such TFs as the Nuclear Factor of the kappa light chain enhancer of B cells (NFκB), Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STAT), and activator protein 1 (AP1) may occur due to their sensitivity to the alterations in the cell redox-potential that is impacted by the ROS/RNS production, the latter, in turn, depends on the functioning of all above mentioned factors. These positive feedback loops form “vicious circles” resulting in the severe nature of SIR-associated diseases. This can also be facilitated by the possibility of the SIR development mediated with redox and oxygen-sensitive TFs that typically occurs under metabolic disorders (insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, etc.) without the primary alteration characteristic of acute inflammation. Thus, SIR-associated diseases can be regarded as highly threatening human diseases. On the one hand, these diseases and conditions are associated with the occurrence of chronic low-grade inflammation (type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis and coronary diseases, metabolic syndrome, stroke, depression and anxiety disorders, neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's disease, steatohepatitis, etc.). On the other, SIR can lead to such life-threatening conditions as Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), “cytokine storming” under COVID-19, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Finding new approaches to increase the efficacy of the SIR therapy has become a multidisciplinary challenge since the current anti-inflammatory therapies target only few effector mechanisms underlying the SIR development and are mainly focused on eliminating the effects produced by inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, leukotrienes, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, ROS/RNS, etc.). The therapies are usually opted to suppress the production of inflammatory mediators and/or to reduce their circulation in the blood and other biological fluids, as well as their reception. It is quite recently, when new medicines targeting TFs and their dependent signalling pathways have been elaborated. However, most synthetic TFs modulators have a number of adverse effects. In this regard, polyphenols are of particular interest, as they are able to suppress the activation of several TFs with a pro-inflammatory effect and/or induce signalling pathways antagonistic to them. Polyphenols, unlike the most of synthetic TFs modulators, are considered as having acceptable safety profile.

The purpose of this review that highlights both the recent reports and the results of the authors' own research, is to encourage scientists to develop new approaches to the differentiated therapy of various SIR manifestations (low- and high-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotypes) by modulating redox-sensitive transcription factors with polyphenols and to determine the saturation of the pharmaceutical market with appropriate dosage forms tailored for targeted delivery of these compounds. An important issue in this regard is to determine ways to overcome the limited bioavailability of most polyphenols in the laboratory animals laboratory animals and human body.

A comprehemsive literature search was conducted across several databases including Medline via PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection and Scopus online databases with the following key terms and phrases: “systemic inflammatory response”; “systemic inflammatory response syndrome”; “cytokine storming”; “chronic low-grade inflammation”; “systemic inflammation”; “meta-inflammation”; “redox-sensitive transcription factors”; “polyphenols” AND “transcription factors”; “polyphenols” OR “phenolic acids” OR “flavonoids” OR “stilbenes” OR “coumarins” OR “tannins” AND “inflammatory response”; “polyphenols” OR “phenolic acids” OR “flavonoids” OR “stilbenes” OR “coumarins” OR “tannins” AND “transcription factors”, etc. All experimental and clinical studies as well as review articles, editorials, and case reports regardless of date, were selected. Special attention was paid to summarizing the knowledge and findings accumulated by Ukrainian researchers.

2. Low- and high-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotypes

Inflammation is defined as the typical pathological processes. Its biological practicability consists in killing, inactivating, or walling off the offending agent (1), and triggering a cascade of events that heal and reconstitute damaged tissues (2) [[1], [2], [3]]. That is, “classic” normergic inflammation (normophlogosis) is a highly regulated protective response with prompt initiation and timely resolution, or, in general, an adequate body response to an abnormal situation (impact of phlogogenic factors such as infections and traumatic injuries).

The situation, when the generalized effect of pathogenic agents overpowers the compensatory capabilities of the anti-inflammatory resistance system, promotes the development of the Systemic Inflammatory Response (SIR) as an uncontrolled or unresolved process, which may cause many acute and chronic diseases. From this point of view, the SIR is seen as a dysfunctional system that neither by itself nor by its separate components provides a sufficient protective basis for the body that ultimately may result in the development of a chronic and/or an aggressive pathological process.

In our opinion, this statement is true for the systemic inflammatory reactions of different intensity, which are, nevertheless, fundamentally different. On the one hand, the SIR can develop gradually over the time (low-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype, LGSIP); on the other, the powerful action of pathogenic factors (high-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype, HGSIP) can rapidly break the system of anti-inflammatory resistance.

2.1. Low-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype

2.1.1. General characteristics of the low-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype and associated diseases

The first variant is characteristic of chronic low-grade inflammation (“subclinical” or “silent” inflammation) [2,[4], [5], [6]], including inflammatory states induced by alterations in the metabolism (“meta-inflammation”) [7], hemocoagulation (“thrombo-inflammation”) [8] and disorders of central and peripheral circadian oscillators [9]. The LGSIP to a greater extent contributes to a long-term inflammation without its complete resolution but with its further transition into a chronic form, and is accompanied by long-term metabolic disorders. In contrast to it, the HGSIP promotes the aggressive, life-threatening nature of the disease that leads to the occurrence of such “resuscitation” syndromes as “cytokine storming” under COVID-19, SIRS, DIC, and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS).

According to hypothesis of the energy-saving “thrifty phenotype”, the LGSIP can start developing even at the prenatal period, and from this perspective it may be considered as evolutionarily advantageous for survival of the fittest in a hungry environment after birth, but the LGSIP increases the risk of developing metabolic syndrome under an obesogenic diet [10]. As a consequence, the following medical conditions and diseases including type 2 diabetes, coronary diseases, stroke, depression and anxiety disorders, neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's disease, steatohepatitis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and other disabilities may develop [11,12]. Other LGSIP causative factors are as follows: persistent infections, dysregulated microbiota and gut permeability, cellular senescence, failure to eliminate waste products, alcohol consumption, etc. [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. The gradual development of systemic inflammation is inherent in certain septic conditions and in systemic consequences of traumatic injuries [[17], [18], [19]].

The mechanisms underlying the LGSIP formation under these conditions can include the following processes: generalized inducible production of cytokines and other bioregulators, oxidative-nitrosative stress, depolymerization of extracellular matrix components, systemic microcirculatory disorders with multiple organ dysfunction [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. In turn, these processes can lead to the secondary systemic alteration and intensify the impact of the number of pathogenic factors including hypoxia, acidosis, secondary endotoxicosis (accumulation of endotoxin from gram-negative bacteria and other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) in the blood when biological barriers are broken), hypovolaemia, accumulation of tissue decomposition byproducts in the blood [20,22,24,25].

2.1.2. Diagnostic criteria of the low-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype

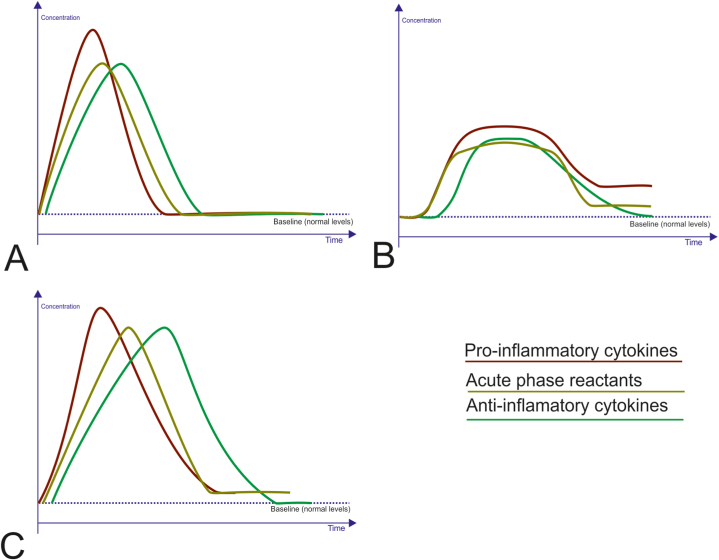

Characteristic features of the LGSIP are a 2- to 4-fold increase in serum levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as acute phase proteins when there are no evident immediate triggers [2,24,26]. This pattern can be seen in Fig. 1B in comparison to concentrational and temporal changes in these compounds under acute inflammation (Fig. 1A) and HGSIP (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Alterations in systemic inflammatory response markers under different inflammatory traits. A. Acute inflammatory reaction. This is a physiological response to phlogogenic factors characterized by a quick elevation in serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, not exceeding a certain reaction norm that enables to avoide signs of severe structural and functional disorders. Some time later (hours) the levels of the acute-phase reactants and anti-inflammatory cytokines increase. Over time, when the response resolves, levels of these compounds gradually return to the baseline (recovering). B. Low-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype is characterized by a prolonged rise in serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute-phase reactants, albeit not to the peak levels obtained during the acute reaction. At the same time concentrations of the anti-inflammatory cytokines can fall below the baseline for a while. C. High-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype. This is a pathological response to a powerful action of extreme harmful stimuli. There is a rapid rise in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, exceeding the highest levels reached during the acute response that amplifies the risk of serious structural and functional disorders. The elevation of serum acute-phase reactants, as well as a compensatory increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines quickly arises. For prolonged period serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute-phase proteins remain elevated, while anti-inflammatory cytokines levels can fall below the baseline due to the dysfunction of the system of anti-inflammatory resistance.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines and their receptors involved in the SIR, also include tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and its soluble receptors 1 and 2 (sTNFR-1, sTNFR-2); interleukins (IL): IL-6, IL-8, and sometimes IL-1, IL-18; interferons (IFN): IFN-α and IFN-γ. Some other inflammatory mediators have already been described in the literature, including acute-phase reactants, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A, ceruloplasmin, and fibrinogen; CC chemokine ligands 2, 3, and 5; and adhesion molecules, such as E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. At the same time, a compensatory increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-4, IL-13) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) may be seen. However, elevated levels of the inflammatory mediators do not achieve to the peak levels typical for the acute inflammation that indicates the SIR as an unresolved, and smoldering inflammatory trait.

2.2. High-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype

2.2.1. General characteristics of the high-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype and associated diseases

Over the HGSIP formation, the stage of “pre-systemic” inflammatory response takes several hours, the time required to involve the inducible gene expression products in the process. In some critical conditions, the primary alteration focus may be either absent at all or its role in the HGSIP formation is extremely insignificant, for example, in fulminant sepsis in humans, or in an experimental endotoxin shock (generalized Shwartzman reaction) in animals, in hemotransfusion and anaphylactic shock, crash syndrome, etc. [24,25].

Moreover, the HGSIP can enhance the effect of multiple organ dysfunction due to the secondary tissue destruction, critical disruption of some homeostasis parameters (acidosis, hypoxia, hypovolaemia, etc.), and entry of the microbial enzymes into the circulation in case when the intestinal epithelium fails to perform its barrier function. Because of the damaging effect caused by the secondary multiple organ failure, the HGSIP can progress that in severe cases results in high mortality despite the intensive clinical care [25].

The chance of this type of the pathology to occur and progress is related to the fact that mammals have an extremely high level of response to the action of pathogenic factors by using the exudative-vascular complex and demonstrate the high sensitivity of vital organs to microcirculatory disorders [27].

2.2.2. Diagnostic criteria of the high-grade systemic inflammatory response phenotype

Classic manifestation of the HGSIP is the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), whose diagnosis criteria were formalized by an American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference, which was held in Northbrook in August 1991 [28]. Objectively, SIRS is defined by the satisfaction of any 2 of the criteria below: body temperature over 38 (100.4 °F) or under 36 °C (96.8 °F), heart rate faster than 90 beats/minute, respiratory rate over 20 breaths/minute or partial pressure of carbon dioxide less than 32 mmHg (4.3 kPa), white blood cells count greater than 12,000 (12 × 109 cells/L) or less than 4000/μL (4 × 109 cells/L) or over 10% immature forms or bands [28]. SIRS can result from insults such as severe inflammatory stimuli, which may be bacterial or nonbacterial (trauma, burns, autoimmune disorders, pancreatitis, etc.).

The identification of SIRS criteria according to some researchers [24] rested on attempts to cope chiefly with the problem of prognosis and early diagnosis of septic complications. For instance, determining SIRS markers was based on applying scales for the general condition assessment, in particular, ARASNE II (“Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II”), which contains 4 indicators of this syndrome. Within this concept, sepsis was defined as SIRS plus a focus of infection. But the sepsis-3 criteria have emphasized the value of a change of two or more points on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), and removed the SIRS criteria from the sepsis definition [29].

To date, the SIRS diagnosis has been regarded as an unfavorable prognostic factor [30,31], but in some cases the SIRS criteria have been proven as insufficiently effective for predicting mortality, for example, in sepsis [28]. There are groups of hospitalized patients, particularly at extremes of age, who do not meet the criteria for SIRS but progress to severe infection, MODS and death [32]. The observational study of over 130,000 septic patients demonstrated that one out of eight patients did not have two or more criteria.

The dynamics of the HGSIP formation proceeds through three distinct stages: 1) the local production of cytokines in response to the trauma or infection; 2) the release of a small amount of cytokines into the systemic circulation; 3) the “generalization” of the inflammatory reaction. The last stage of the HGSIP formation can be divided into two periods taking into account the interaction between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators: 1) the initial stage, which is characterized by the formation of extremely high concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, ROS/RNS; 2) a compensatory anti-inflammatory response associated with the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. The rate of their secretion and concentration in the blood and tissues gradually increases with the simultaneous decrease in the content of inflammatory mediators.

Fig. 1C illustrates concentrational and temporal changes in serum levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as acute phase proteins characteristics for HGSIP when compared with those under acute inflammation (Fig. 1A) and LGSIP (Fig. 1B).

Some researchers do not support the point of view that the compensatory anti-inflammatory response is a reaction to the HGSIP, because some patients due to the genetic determination or the responsiveness altered under the impact of environmental factors can develop an immediate sharp imbalance in cytokines. This phenomenon was named as Compensatory Anti-inflammatory Response Syndrome (CARS) [33,34]. It is characterized by a low level of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ with a considerable increase in the level of anti-inflammatory factors IL-10 and IL-1Ra [33]. Under these conditions, immune deficiency contributes to the deterioration of monocyte activation that is characterized by a marked decrease in the expression of HLA-DR antigen receptors, a loss of antigen presentation properties, and a decline in the capability of these cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to the administration of lipopolysaccharide [35]. All of these can result in immunological insufficiency and accession of secondary infection, sepsis [34].

Recently, there has been described the phenomenon of a kind of immunological dissonance, when both pro-inflammatory hyperactivity (SIRS) and immunosuppression (CARS) occur simultaneously and demonstrate a more marked destructive potential. This phenomenon is called Mixed Antagonist Response Syndrome (MARS) [36,37].

It is clear that SIRS criteria are not specific enough and do not fit into all conditions accompanied by the SIR, starting from “resuscitation” syndromes (septic shock, DIC, MODS) to “low-intensity” manifestations (with metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, etc.). For instance, cytokine storming under COVID-19 is a component of the developed SIR that can vary in terms of the severity from the LGSIP to the HGSIP and shows no signs that enable to establish the diagnosis of the SIRS. COVID-19 is known to deteriorate type II pneumocytes and damage the alveolar immunologic balancing process through the activation of the localized and general inflammatory responses. Due to an aggregation of uncleaved angiotensin II, the stimulated inflammatory cells cause cytokines synthesis and secretion (cytokine storming), leading to widespread tissue injuries [38]. In some cases severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus can form the HGSIP (elevated CRP, fibrinogen, procalcitonin, D-dimer, ferritin, IL-6, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated neutrophils, reduced lymphocytes, low albumin), whose consequences include Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome (MIS) affected children (MIS-C) and adults (MIS-A) with inflammation of a variety of organ systems, including the heart, lungs, brain, kidneys, gastrointestinal system, skin, and eyes [[39], [40], [41]]. However, criterial signs of the SIRS may be absent. Therefore, we should avoid identifying the HGSIP as a manifestation of systemic pathological process with the SIRS.

N. V. Zotova et al. [26] propose the definition of the SIR as a “typical, multi-syndrome, phase-specific pathological process, developing from systemic damage and characterized by the total inflammatory reactivity of endotheliocytes, plasma and blood cell factors, connective tissue and, at the final stage, by microcirculatory disorders in vital organs and tissues”. To diagnose the SIR, the authors offer 2 scales.

-

1)

the reactivity level (RL) scale – from 0 to 5 points (under estimation of elevated concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP in plasma): RL-0 – normal level; RL-5 confirms systemic inflammatory mediator release, and RL-2–4 defines different degrees of event probability;

-

2)

the systemic inflammation scale, considering additional criteria (D-dimers >500 ng/mL, cortisol >1380 or <100 nmol/L, troponin I ≥ 0.2 ng/mL, and/or myoglobin ≥800 ng/mL) along with RL, addresses more integral criteria of SIR: the presence of ≥5 points according to the systemic inflammation scale proves the high probability of the SIR developing.

The authors demonstrated that in only 5 of 78 cases lethality was not confirmed by the presence of the SIR. This process was registered in 100% of cases with septic shock [26].

Additionally, some researchers consider hyperglycaemia [42], elevated procalcitonin and lipopolysaccharide binding protein [43], and indices of oxidative and nitrosative stress [44,45] as SIR markers.

Hence, the literature provides strong arguments in favour of defining the SIR as both a typical pathological process and a dysregulatory pathology accompanied by the loss of the protective basis characteristic of acute inflammation, the generalized involvement of inflammatory mechanisms, which developed phylogenetically only for topical purpose.

3. Role of the redox and oxygen-sensitive transcription factors in the formation of systemic inflammatory response

A key role of the SIR control is at the level of gene transcription. The coordination of the functions in regulating the inflammatory response is provided by four classes of the TFs [46,47].

-

1)

constitutively expressed TFs, such as NFκB, STAT, Interferon Regulatory Factors (IRF), activated by signal-dependent post-translational modifications that affect their activation properties and nuclear localization. For example, cytoplasmic NFκB is rapidly translocated to the nucleus after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, and is involved in the induction of primary genes. Other TFs of this class include latent nuclear AP1, such as c-Jun phosphorylated rapidly after LPS stimulation. Nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) has a vital anti-inflammatory effect;

-

2)

inducible in a stimulus-dependent manner TFs, such as AP1, the CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein (C/EBP), Activating Transcription Factor 3 (ATF3), that need de novo protein synthesis for LPS-dependent stimulation. In addition to inducing secondary late gene expression, these TFs play a role in determining waves of time-dependent levels of gene expression;

-

3)

tissue-restricted and lineage-specifying TFs, such as macrophage-differentiation TFs PU.1 and C/EBPβ, that establish inducible cell-specific responses to stress and inflammation, by generating macrophage-specific chromatin domain modifications;

-

4)

metabolic sensors of the nuclear receptor family, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and liver X receptors (LXR), activated respectively by fatty acids and cholesterol metabolites. These ligand-dependent TFs are anti-inflammatory and link metabolism and tissue inflammation.

Molecular mechanisms of the inflammatory response transcriptional control have already well-described in the literature [47,48].

The strongest candidates of the pro-inflammatory TFs are members of the NFκB and AP1 families. Signalling cascades associated with these TFs are activated by a number of extracellular ligands and membrane-bound receptors, most often represented by members of the super-families of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), TNFR, IL-1R, and antigen receptors. Lately, there have been discovered new signalling pathways, which regulate the activity of NFκB and AP1 in response to changes in the redox potential of cells and intracellular stresses, accompanied by DNA damage, ROS/RNS generation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, the action of intracellular pathogenic factors and are mediated by protein families of RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) [49,50]. It has been shown the NFκB activation by cytokines TNF and IL-1β requires NADPH-dependent ROS production [51,52] and a decrease in the level of reduced glutathione [53].

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLRs, NLRs and RLRs, activate via adaptor molecules downstream kinases – IκB Kinase (IKK) complex, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs), TANK Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1), Receptor Interacting Protein kinase 1 (RIP-1) [54]. This results in the activation of pro-inflammatory TFs (NFκB, AP1, IRF3), which produce effecter pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and pro-oxidant proteins, such as Cyp7b, Cyp2C11, Cyp2E1and gp91 phox, etc. [55,56].

Thus, PRRs-mediated activation of the above mentioned TFs is accompanied by the development of oxidative-nitrosative stress that changes the redox potential of cells and, in addition, activates redox-sensitive TFs. The vicious circle, which occurs in this case, contributes to an even greater formation of pro-oxidant proteins and the production of ROS/RNS that in this way promotes the chronicity and/or aggressive nature of the inflammatory response [21,57].

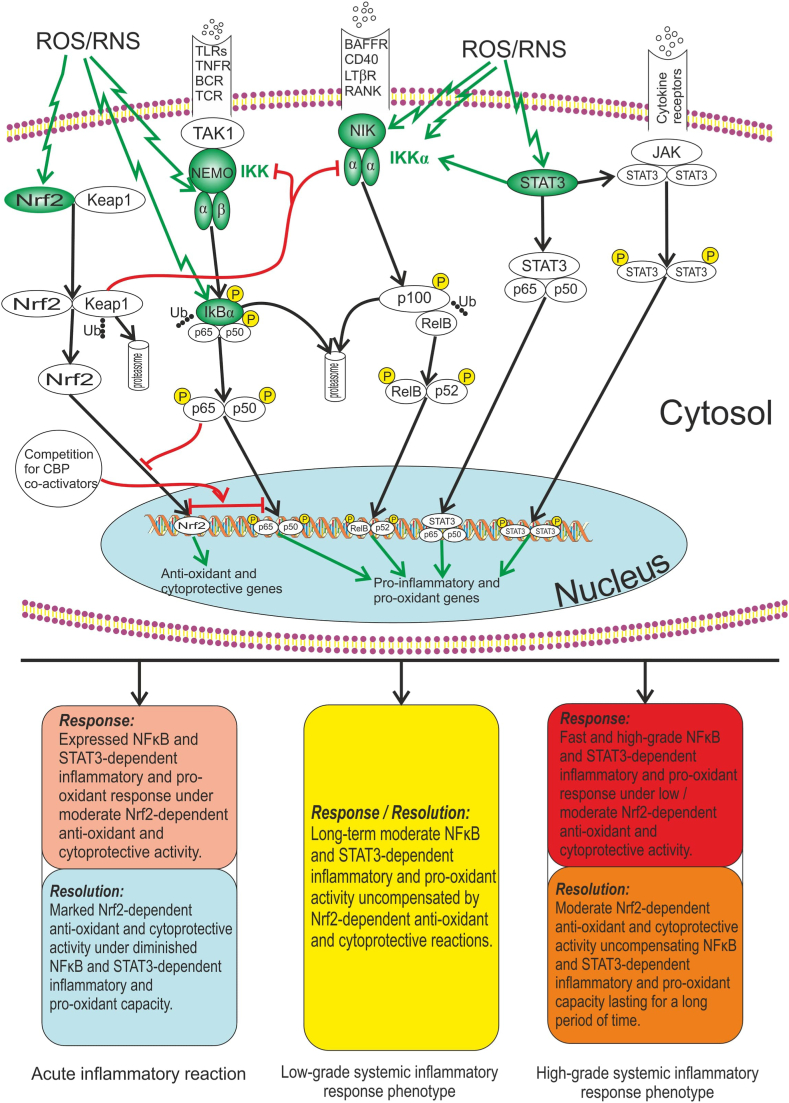

Fig. 2 illustrates the relationship between redox-sensitive TFs (NFκB, STAT3 and Nrf2) and role of the ROS/RNS in the TFs-dependent activation of both pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant genes, and anti-oxidant and cytoprotective genes.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between redox-sensitive TFs (NFκB, STAT3 and Nrf2). ROS/RNS are compounds, which are capable to maintain the long-time activity of redox-sensitive TFs even in the absence of action from other TFs inducers (receptor stimuli). ROS/RNS have been shown to activate canonical and non-canonical NFκB signalling pathways through alternative IκBα phosphorylation and through activating a critical redox-sensitive kinases (IKK, NIK). Nrf2 and STAT3 are also activated by oxidative/nitrosative stress and other stimuli. The Nrf2 repressor Keap1 can prevent NFκB activation by inhibiting the IKK. In addition to this, simultaneous activation of Nrf2 and NFκB results in the competition for CBP co-activators in the nucleus, in consequence of which these TFs suppress each other. In turn, STAT3 is capable to activate NFκB through stabilization of IKKα. Unphosphorylated STAT3 (following the activation of the STAT3 gene in response to ligands such as IL-6) can produce complex STAT3 with unphosphorylated p65/p50 heterodimer that activates promoters that have κB elements. The outcomes of ouoxidative/nitrosative stress may include NFκB and STAT3-dependent pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant genes expression, as well as Nrf2-dependent anti-oxidant and cytoprotective genes expression. It is supposed that every pattern of inflammatory response (acute inflammation, LGSIP, HGSIP) with respect to the phase (response, resolution) can be characterized by different intensity of effects, which depend on the activity of redox-sensitive TFs. Note: Redox-sensitive proteins are shown in green; BAFFR – B-cell Activating Factor Receptor; BCR – B Cell Receptor: CREB – Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding Protein; CBP – CREB Binding Protein; IκB – NFκB Inhibitory Protein; IKK – IκB kinase; JAK – Janus Kinase; Keap1 – Kelch like ECH Associated Protein 1; LPS – Lipopolysaccharide; LTβR – Lymphotoxin β Receptor; NEMO – NFκB Essential Modulator (IKKγ); NFκB – Nuclear Factor κB; NIK – NFκB-Inducing Kinase; Nrf2 – Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2; P – Phosphorylation; RANK – Receptor Activator of NFκB; RANKL – Receptor Activator of NFκB Ligand; ROS – Reactive Oxygen Species; RNS – Reactive Nitrogen Species; STAT3 –Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; TAK1 – Transforming Growth factor-β-Activated Kinase; TCR – T Cell Receptor: TLRs – Toll-Like Receptors; TNFR –Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor; Ub – Ubiquitination. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

ROS also activate the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway through the inhibition of tyrosine phosphatase [58,59]. This process is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines, and in particular by IL-6 [60]. At the same time, STAT3, especially the protein of “non-canonical” (mitochondrial) localization, have been proven to increase ROS production [61].

Notably, STAT3 and NFκB synergistically regulate genes encoding cytokines and chemokines [62]. NFκB family members can interact with STAT3, resulting in transcriptional synergy or repression of NFκB/STAT3-controlled genes [63]. STAT3 is a factor of NFκB positive regulation [64].

Since excessive redox-sensitive TFs activation is closely linked to the SIR formation, the role of new regulators, including polyphenols, in the prevention of over- or unnecessary activation of these factors has been widely studied.

Numerous reports have emphasized an important role of NFκB in the pathogenesis of various diseases that, on the one hand, are followed with the LGSIP development, e. g. metabolic syndrome [65,66], atherosclerosis [67], diabetes mellitus type 2 [68], osteoporosis [69], rheumatoid arthritis [70], inflammatory bowel diseases [71], multiple sclerosis and autoimmune encephalomyelitis [72], asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [73], periodontal disease [62], post-traumatic stress disorder [74], etc. But on the other, researchers point out a role of the NFκB activation in the mechanisms of diseases followed by the HGSIP development, in particular, septic shock [75], DIC [76], traumatic brain injury [77], burn injury [78], cytokine storming under COVID-19 [79].

NFκB-dependent formation of the LGSIP is reported in cases of the disruption of light/dark cycle [80], high-calorie diet [81], exposure to ionizing radiation [82] and toxic factors [21]. There have been identified a number of genetic disorders of the IKK-IKB-NFκB system that can cause autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, malignant tumours, and critical changes in the morphogenesis and regeneration [83].

The state of NFκB- and AP1-associated signalling pathways to some extent depends on the activity of another representative of redox-sensitive TFs – Nrf2. Under oxidative stress, cytoplasmic Nrf2 is released from the inhibitory protein Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription due to its ability to bind to a cis-regulatory enhancer with the nucleotide sequence 5′-A/GTGAC/TnnGCA/G-3′ known as Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) [84].

Studies conducted on Nrf2 knockout animals show the ARE protective role in the processes of inflammation, carcinogenesis, fibrosis, as well as in the protection against various stress effects [85]. Moreover, there has been found out a relationship between the development of inflammation induced by chemical agents and Nrf2 deficiency.

Induction of the Nrf2/ARE system facilitates the termination of acute inflammatory processes, thus preventing their turning into a chronic stage [86]. Specific Nrf2/ARE inducers, for example, dimethyl fumarate, are effective in lowering SIR indicators (TNF-α and CRP levels in the blood serum) under the experimental metabolic syndrome [87].

According to our data, the combination of inhibitors of NFκB- or AP1 activation and Nrf2/ARE inducers appears as more effective means to correct SIR and general metabolic disorders that has been evidenced by an example of the combined use of ammonium pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate and quercetin as NFκB inhibitors and SR 11302 as an AP1 inhibitor, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate as an Nrf2/ARE inducer [88,89]. Due to their combined action, the above compounds prevent the production of secondary byproducts of lipid peroxidation in the blood of rats, enhance the antioxidant potential, correct carbohydrate metabolism disorders (hyperinsulinaemia, insulin resistance), as well as restrain oxidative-nitrosative stress and depolymerization of collagenous and non-collagenous components of the periodontal organic matrix more effectively compared with the separate administration of the compounds.

However, the positive effect of synthetic modulators of transcription factors is clouded by the high risks of adverse reactions. For instance, ammonium pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate, a specific inhibitor of NFκB activation, is known to have geno-, carcinogenic, teratogenic, and neurotoxic effects [90,91]; dimethyl fumarate, a specific Nrf2/ARE inducer can cause severe immunopathological processes and gastrointestinal disorders [92,93].

Therefore, the effectiveness of using non-toxic plant polyphenols, which have a positive effect on several redox-sensitive transcription factors, including functionally antagonistic NFκB and Nrf2, is generating a considerable practical interest.

4. Polyphenols as regulators of transcription factors

4.1. Classification of polyphenols and their origin

Polyphenols are complex organic molecules that contain an aromatic ring and several hydroxyl radicals as substitutes for hydrogen atoms in the aromatic ring in their structure. Polyphenols include a variety of substances that can be classified by their chemical structure, origin, or biological function [94,95]. According to the chemical structure, polyphenols are divided into.

-

1)

Phenolic acids (benzoic acids and cinnamic acids)

-

2)Flavonoids

-

a)Isoflavones, neoflavonoids and chalcones

-

b)Flavones, flavonols, flavanones and flavanonols

-

c)Flavanols and proanthocyanidins

-

d)Anthocyanidins

-

a)

-

3)

Stilbenes

-

4)

Coumarins

-

5)

Tannins

-

6)

Polyphenol amides

-

7)

Other polyphenols

The varied diet that contains plenty of fruits, vegetables, and berries is the main source of polyphenols for the human body. Phenolic acids are found in large quantities in fruits, vegetables, legumes, cereals, and coffee beans. In most cases, phenolic acids found in food are in the form of compounds bound to various sugars and their derivates. Flavones, flavonols and flavanones are abundantly found in plants, especially in citrus fruits, apples, and grapes. The most common representative of the group of polyphenol compounds is quercetin. Flavanols and proanthocyanidins (which include epi (halo)catechins and their gallates) are mainly found in tea, cocoa and chocolate. Anthocyanidins are components of the plant pigments and render the shades of red, yellow, blue, and other colors [96]. Stilbenes, whose most known representative is resveratrol, are found in various berries. Red grapes are considered as extremely rich in resveratrol [97]. Coumarins are common intermediate products of many bacteria, fungi and plants. Plants of the Apiaceae, Asteraceae and Rutaceae families contain the highest concentration of coumarins [98]. Tannins are found in the bark, roots, and leaves of higher plants, and impart a characteristic astringent flavor to solutions used to make certain types of wine, beer and fruit juices [99].

4.2. Structurally determined biological properties of polyphenols

4.2.1. Antioxidant properties of polyphenols

One of the most well-known properties of polyphenols is their ability to break the cascade of oxidative reactions. Due to this ability, polyphenols can be classified as powerful non-enzymatic antioxidants. Phenolic acids have pronounced antioxidant properties, as they have the ability to absorb both simple radicals (superoxide anion radical, hydroxyl radical) and more complex organic radicals (2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl or DPPH-radical, and 3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid or ABTS radical) [7]. Isoflavones genistein and daidzein and their glycated forms genistin and daidzin have a similar mechanism of antioxidant action [100]. Quercetin, as a representative of flavonoids, due to the presence of five phenolic groups in its structure, can act as a powerful acceptor of free radicals. However, unlike phenolic acids and isoflavones, quercetin is capable to produce direct effect on some antioxidant systems of the cell. For example, quercetin can affect the concentration of reduced glutathione (GSH) in the cell by acting as either a hydrogen acceptor or donor, depending on the concentration of quercetin. Also, quercetin can affect the activity of antioxidant enzymes by interacting with metals of variable valence, e.g., manganese [101]. Flavanols, in addition to the common capability of polyphenols to capture free radicals directly, have another important property, viz. To attach (chelate) iron ions (Fe2+). Under Fe2+ deficiency, the Fenton's reaction is difficult or impossible that will reduce the production of such a powerful oxidant as the hydroxyl radical [102]. Anthocyanidins can absorb free radicals by attaching the latter to hydroxyl groups in the B-ring, as well as to the oxonium ion in the C-ring [103]. Resveratrol, as a representative of stilbenes, also has powerful antioxidant properties due to the direct absorption of free radicals such as hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion radical and peroxynitrite [104,105]. Coumarins, in addition to the direct ability to absorb free radicals, are powerful inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase that, in turn, restrain the intensity of lipid peroxidation [106]. Tannins can absorb both molecular oxygen and reactive oxygen species. Moreover, tannins can be reduced by ubiquinones and continue to scavenge oxygen/free radicals [107].

Hence, all chemical compounds belonging to polyphenols are capable to interact directly with oxygen-containing free radicals and then neutralize them. This effect is caused by a large number of functional groups that can act as both electron donors and acceptors.

4.2.2. Antibacterial properties of polyphenols

Isoflavones, having a prenyl group in their structure, show pronounced antibacterial properties against streptococci [108]. However, even synthetic isoflavones that contain additional prenyl groups are not effective enough in relation to S. enterica (NCTC 13349), E. coli (ATCC 25922), and C. albicans (ATCC 90028) [109]. Quercetin shows a bacteriostatic effect on E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. enterica Typhimurium and S. aureus due to the ability to destroy the cell membrane. Quercetin has a greater effect on the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria than on Gram-negative ones [110]. Another mechanism of the bacteriostatic effect of flavonoids is the inhibition of nucleotide biosynthesis processes due to the presence of B-rings in the structure of flavonoids [110]. Proanthocyanidins (epigallocatechin gallate) demonstrate prominent bactericidal properties against various strains of S. aureus, and also prevent the formation of bacterial biofilms [111]. The literature also presents data relating to the inhibitory effect of epigallocatechin gallate on growth of E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. mutans, V. cholerae, H. pylori and Clostridium perfringens [112]. The mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of epigallocatechin gallate on bacterial growth is regarded as a breakage of the structure of proteins involved in the DNA segregation and cell division [113]. Anthocyanidins are known as strong antimicrobials due to their ability to destroy the bacterial cell wall and other biological membranes [103]. The antibacterial properties of resveratrol, as a representative of stilbenes, are associated with its ability to bind to ATP synthase, which affects both the ATP synthesis and hydrolysis [114]. Resveratrol has also been reported to display prominent antifungal properties and the ability to inhibit the formation of bacterial biofilms [114]. Antibacterial properties of stilbenes are largely determined by the functional groups in their structure. There are 3 phenolic groups in the structure of resveratrol. The change of the phenolic group in the 4’ position to a bromine atom significantly enhances the antibacterial properties of stilbene, gives it the property to produce reactive oxygen species in cells, destroy or irreversibly bind to DNA [115]. The strength of the antibacterial effect of coumarins builds upon the presence of the following functional groups in the aryl ring: CH3, –OH or –OMe. At the same time, the presence of halogens (fluorine or bromine) as substitutes for hydrogen atoms in the phenyl ring of coumarins significantly reduces their antibacterial properties. Thus, coumarins modified in a certain way have powerful antibacterial properties against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive microorganisms [116]. In addition, the antibacterial effect of coumarins to some extent depends on their ability to bind to the B-subunit of DNA gyrase in bacteria and inhibit supercoiling of bacterial DNA by blocking ATPase activity and lessen urease activity [117,118]. Introducing the prenyl group to the structure of coumarins, by analogy to isoflavones, considerably enhances the antibacterial properties of coumarins [119]. Tannins extracted from plants and their monomers show high antibacterial properties as they are capable to destroy the cell wall of bacteria [120]. Tannins can also impact the activity of lactoperoxidase, contributing to its reduction following spontaneous oxidation under the excessive accumulation of hydrogen peroxide [121]. Lactoperoxidase (E.C. 1.11.1.7) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide in physiological concentrations can oxidize SCN− to OSCN−, which reacts with thiol groups (-SH) of bacterial proteins, inactivating such proteins as hexokinase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase that determines the antibacterial properties of the enzyme [122]. Hydrogen peroxide in high concentrations can oxidize iron in the active center of lactoperoxidase, thus inactivating the enzyme. Tannins can act as direct electron donors for the reduction of iron in the active center of lactoperoxidase that leads to the growth in the antimicrobial activity of the enzyme [121].

4.2.3. Cytotoxic properties of polyphenols

Phenolic acids demonstrate cytotoxic properties against certain cancer cells. The mechanism of cytotoxic activity of most phenolic acids is mediated through the influence on specific transcription factors or on antioxidant enzymes. Only some of the phenolic acids (Protocatechuic acid, Gentisic acid, p-Coumaric acid) can lead to DNA fragmentation and impact on the redox metabolism of tumour cells [[123], [124], [125]]. Another mechanism underlying the cytotoxic activity of phenolic acids described on the example of Caffeic acid is the ability of this class of compounds to chelate iron ions [126]. Isoflavones genistein and daidzein show a minor cytotoxic effect against MCF-7 and HEK293 cancer cells [100]. Complexes of quercetin with rare earth metals have a strong cytotoxic effect against tumour cells, when compared with chemically pure quercetin [101].

Cytotoxic activity of quercetin increases dramatically when it absorbs reactive aldehydes. Such reaction can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death [127]. Quercetin has a dual effect on reactive oxygen species. Taken in low concentrations, it can act as an electron donor and an antioxidant. However, found in high concentrations in the cell, quercetin acts as a stimulator of the production of reactive oxygen species and can initiate apoptosis [128]. Cyanidin-3-glycoside, a representative of the anthocyanidin group, is capable to prevent the migration and invasion of tumour cells [103]. The cytotoxic activity of stilbenes against cancer cells depends on the type of isomerization (trans- or cis-) and is mediated by the inhibition of tubulin polymerization that destabilizes microtubules in cells. At the same time, trans-isomers (resveratrol) show less activity than cis-isomers [129]. Prenylation of stilbenes or the natural presence of one or more prenyl groups in their structure considerably enhances their cytotoxic properties [130].

Coumarins are also known as having a cytotoxic effect against tumour cells [131,132]. Some coumarins, such as Esculetin, can cause DNA fragmentation in tumour cells [133]. Replacement of the carbonyl group of the lactone function of the classic coumarin framework with cyano-(4-pyridine/pyrimidine)-methylene parts allows coumarins to interact with visible light and affect cell mitochondria, increasing the production of reactive oxygen species from the mitochondrial electron transport chain and leading to tumour cell apoptosis [134]. Tannic acids can induce apoptosis of tumour cells by regulating mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species [135,136].

The cytotoxic effect of most polyphenols is associated with the impact on the production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria and the induction of tumour cell apoptosis. Some polyphenols can cause DNA fragmentation and interfere with tubulin polymerization.

4.2.4. Bioavailability of dietary polyphenols

The bioavailability of most polyphenols despite their relatively high concentrations in foodstuffs is very low. Wheat phenolic acids are easily destroyed during processing and cooking that considerably reduces their final concentration in the finished food product (bread, spaghetti, etc.) [137]. Low water solubility of phenolic acids impedes their absorption in the intestine. However, recent literature data has provided evidence of the capability of intestinal microflora to destroy insoluble bonds in the structure of phenolic acids, thus increasing their bioavailability [138]. The bioavailability of most flavonoids can vary and depends on many factors, such as the chemical nature of the flavonoid, type of food processing, other food components, and the state of the gut microbiota. Flavonoids reduce the absorption of glucose and proteins, but the simultaneous consumption of lipids increases the bioavailability of flavonoids [139]. A certain composition of the intestinal microbiota can either promote the absorption of flavonoids or reduce their absorption [140]. Among flavonoids, anthocyanidins demonstrate the lowest bioavailability as the acidic environment of the stomach is optimal for the absorption of these compounds, while the weak alkaline environment of the intestine results in the formation of insoluble forms of anthocyanidins [141]. Resveratrol, along with other stilbenes, shows a very low water solubility that leads to the low bioavailability when taken with food [142]. However, resveratrol can easily penetrate biological membranes due to its high lipophilicity. Therefore, even a slight modification of its ability to dissolve in water will greatly increase its bioavailability. There are several promising methods to increase the bioavailability of resveratrol, for example: encapsulation in lipid nanocarriers or liposomes, emulsions, micelles, or insertion into polymer nanoparticles, solid dispersions and nanocrystals [143]. Another mode to increase the bioavailability of stilbenes is to introduce additional hydroxyl groups to their structure or replace one or more functional groups with the following radicals as methoxylate, halogens, and others [143]. It is noteworthy that the halogenation of stilbenes is a quite dangerous way of increasing their bioavailability, since the presence of halogens can cause the appearance of pro-oxidant properties in stilbenes [115]. The bioavailability of coumarins, for example, of esculetin, is also low and amounts to approximately 19% when taken orally [144,145]. Scopoletin shows even lower bioavailability (approximately 6%) when taken by mouth [146]. One of effective methods to improve the bioavailability of scopoletin and probably other coumarins is the formation of water-soluble micelles [147]. Tannins have long been considered as antinutrients due to their low bioavailability. However, this opinion has changed once the fact has been proven that tannins are actively converted by the intestinal microbiota into biological compounds with a sufficiently high level of the bioavailability [148]. Notwithstanding, that tannins, which are not processed by the gut microbiota, can reduce the absorption of iron ions, zinc, and proteins, especially when are in high concentrations in the gut [149]. On the other hand, tannins, which are easily hydrolyzed, may even improve the absorption of nutrients in the gut [150].

Researchers are working to achieve higher bioavailability of polyphenols through various means. One promising approach to increase the bioavailability of quercetin is the use of nanophytosomes, because quercetin-loaded nanophytosomes have been found to have a more significant impact on antioxidant enzymes [151]. Similar results have been observed for epigallocatechin-3-gallate [152]. The creation of various nanoparticles, such as nanocrystals, nanoemulsions, or core-shell polymer nanoparticles, with polyphenols has a significant impact on their solubility in water. This, in turn, increases their bioavailability [153,154].

Another approach addressing the issue of low bioavailability of polyphenols is the creation of excipient emulsions with different oils. This technique enables polyphenolic compounds to easily pass through the intestinal barrier and enter the bloodstream [155]. The creation of liposomes loaded with polyphenols and their conjugation with specific proteins can further increase the bioavailability and selectivity of polyphenolic compounds [156]. In addition, the formation of phospholipid-polyphenol complexes can significantly enhance the solubility of polyphenols in water. For instance, the formation of an isorhamnetin phospholipid complex can increase the solubility of isorhamnetin in water in 122 times [157].

Glycosylated polyphenols have higher water-solubility, therefore, increasing the level of glycosylation of polyphenolic compounds artificially can enhance their water solubility [158]. However, certain components of the diet can either increase or decrease the bioavailability of polyphenols. For instance, glucose-containing saccharides interfere with the deglycosylation of quercetin glucosides during intestinal epithelial uptake, thus, lowering the quercetin concentration in the blood during combined intake [159]. On the other hand, a diet rich in fiber can increase the bioavailability of polyphenols [160].

Thus, we can summarize that the bioavailability of most polyphenols is very low due to their low solubility in water (intestinal juice). In order to obtain marked biological effects, either modification of polyphenols with new functional groups or their high concentrations when taken by mouth can be recommended. Some compounds of polyphenol origin (tannins) do not have a direct systemic biological effect on the macroorganism and require preliminary hydrolysis to form systemically active compounds. Promising methods for improving the bioavailability of polyphenols include the elaboration of nanoformulations, oil-based excipient emulsions, phospholipid complexes, and liposomes loaded with polyphenolic compounds. However, further in vivo studies on animals and eventually humans are necessary to confirm that increased bioavailability does not come with adverse effects.

4.3. Effect of polyphenols on specific transcription factors

4.3.1. Effect of phenolic acids on specific transcription

Phenolic acids exert a strong anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the activation of the transcription factor NFκB [150]. They have a strong inhibitory impact on the TLR4/NFκB axis, therefore they can serve as effective anti-inflammatory agents for many bacterial infections or conditions that are accompanied by the TLR4 activation (diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, etc.) [161,162]. The impact on the NFκB/JNK/p38 MAPK axis determines the potent antithrombotic effect of phenolic acids [163]. Phenolic acids, namely salvianolic acids, are powerful blockers of STAT3 activation [164]. They also reduce the activity of the transcription factor AP1 [165]. At the same time, phenolic acids are capable to activate the transcription factor Nrf2, which mediates their indirect antioxidant effect [166]. The effect of phenolic acids on a particular transcriptional cascade may depend on both the chemical nature and the dose. Curcumin always primarily affects the NFκB cascade, and then acts as an Nrf2 activator. At the same time, ferulic acid in low concentrations acts as a pro-oxidant and does not affect NFκB and Nrf2 cascades, while in high concentrations it reduces NFκB activation and stimulates Nrf2 [167]. Some phenolic acids, such as caffeic acid, have a powerful stimulating effect on the activation of cell cycle repressor genes (CDKN1A and CHES1) thus contributing to the activation of apoptosis in tumour cells [168]. The summarized effects of polyphenolic compounds on specific transcriptional factors are given in Table 1. It is also worth noting, that some phenolic acids can inhibit NFκB activation by influencing a non-canonical pathway [169].

Table 1.

Effects of polyphenols on specific transcriptional factors.

| Studied polyphenol | Effect | Authors (year) | Reference # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | |||

| Danshensu, oresbiusin, rosmarinic acid-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, prolithospermic acid, rosmarinic acid, isosalvianolic acid A, lithospermic acid, salvianolic acid, salvianolic acid C | Inhibition of TLR4/NFκB pathway activation | Liu H. et al. (2018) | [150] |

| Qingwenzhike (a compound containing 33 flavonoids, 23 phenolic acids, 3 alkaloids, 3 coumarins, 20 triterpenoids, 5 anthraquinones, and 12 others) | Inhibition of TLR4/NFκB pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome activation | Zhang C. et al. (2021) | [161] |

| Salvianolic acid B, Lithospermic acid | Decrease in the chance of thrombosis by regulating the NFκB/JNK/p38 MAPK signalling pathway activation in response to TNF-α | Zheng X. et al. (2021) | [163] |

| Salvianolic acids | Inhibition of high glucose-dependent phosphorylation of STAT3 | Chen J. et al. (2018) | [164] |

| Tannic acid, chlorogenic acid | Decrease in epidermal growth factor receptor, AP1, and STATs activation | Cichocki M. et al. (2014) | [165] |

| Curcumin, ferulic acid | Curcumin up-regulates Nrf2, downregulates NFκB and STAT3 phosphorylation. Ferulic acid up-regulates Nrf2 phosphorylation. | Paciello F. et al. (2020) | [167] |

| Caffeic acid | Induction of apoptosis by increased expression of two cell cycle repressor genes, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 A and checkpoint suppressor 1 | Feriotto G. et al. (2021) | [168] |

| Salvianolic acid B | Inhibition of non-canonical NFκB activation trough CD40/NFκB axis | Xu S et al. (2017) | [169] |

| Flavonoids | |||

| Baicalin | Inhibitory effect on NFκB activation through modulation of IKKβ | Shen J. et al. (2019) | [170] |

| Fisetin | Inhibition of Src-mediated NFκB p65 and MAPK signalling pathways | Ren Q. et al. (2020) | [171] |

| Myricetin | Enhancement of SIRT1 and inhibition of TNF-α-induced NFκB activation. | Chen M. et al. (2020) | [172] |

| Eriodictyol | Repression of TLR4/NFκB signalling | Hu L.H. et al. (2021) | [173] |

| Baicalin | Inhibition of JAK/STAT pathway and the change of macrophage polarization to anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype | Xu M. et al. (2020) | [174] |

| Luteolin | Inhibition of NFκB, JAK-STAT as well as TLR signalling pathways | Gendrisch F. et al. (2021) | [175] |

| Icariin | Increase in Nrf2 gene expression while decreasing NFκB and cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression | El-Shitany N.A. and Eid B.G. (2019) | [176] |

| Quercetin, fisetin, hesperetin, naringenin, daidzein, kaempferol, genistein, luteolin, apigenin | Activation of Nrf2 and induction of FoxO and PPARγ response | Pallauf K. et al. (2017) | [177] |

| Quercetin | Induction of EB-mediated lysosome activation and increase of ferritin degradation leading to ferroptosis and Bid-involved apoptosis | Wang Z.X. et al. (2021) | [178] |

| Icariin | Impairement of NFκB/EMT pathway activation and upregulation of SIRT6 | Song L. et al. (2020) | [179] |

| Robinin | Inhibition of receptor activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL) activation and RANKL-induced MAPK and NFκB signalling pathways, blockade of NFATc1 signalling and TRAcP expression. | Hong G. et al. (2021) | [180] |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | Activation of Nrf2 cascade | Kanlaya R. et al. (2016), | [181,182] |

| Sun W. et al. (2017) | |||

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | Inhibition of proteasome | Yang H. et al. (2011) | [183] |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | Inhibition of NFκB signalling pathway | Gupta S. et al. (2004), | [184,185] |

| Yang F. et al. (2001) | |||

| Quercetin | Suppression of the NFκB pathway and activation of the Nrf2-dependent HO-1 pathway | Kang C.H. et al. (2013) | [186] |

| Quercetin | Inhibition of NFκB and matrix metalloproteinase-2/-9 signalling pathways | Lai W.W. et al. (2013) | [187] |

| Quercetin | Inhibition of NFκB signalling pathway | Chekalina N. et al. (2018), | [188,189] |

| Min Y.D. et al. (2007) | |||

| Epigallocatechin-gallate | Inhibition of non-canonical NFκB signalling pathway | Varthya S.B. et al. (2021), | [190,191] |

| Xu P. et al. (2020) | |||

| Morin | Inhibition of non-canonical NFκB signalling pathway through Wnt/PKC-α and JAK-2/STAT3 signalling pathways | Soubh A.A. et al. (2021) | [192] |

| Stilbenes | |||

| Resveratrol | Suppression of NFκB and JAK/STAT signalling pathways | Ma C. et al. (2015) | [193] |

| Resveratrol | Activation of SIRT1 signalling | Zhu X. et al. (2011) | [194] |

| Polydatin | Inhibition of NFκB and activation of Nrf2 signalling | Huang B. et al. (2018) | [195] |

| Resveratrol | Inhibition of NFκB signalling through suppression of p65 and IkappaB kinase activities | Ren Z. et al. (2013) | [196] |

| Resveratrol | Inhibition of STAT3 activation | Li X. et al. (2016) | [197] |

| Resveratrol and Piceatannol (in combination) | Enhancement of NFκB signalling leading to increased programmed cell death ligand 1 in tumour cells | Lucas J. et al. (2018) | [198] |

| Isorhapontigenin | Increased expression of Yes-associated protein 1 | Wang P. et al. (2021) | [199] |

| Coumarins | |||

| Wedelolactone | Inhibition of activation and phosphorylation of IκKα, IκBα and NFκB p65 | Zhu M.M. et al. (2019) | [200] |

| Wedelolactone | Inhibition of Akt and activation of AMPK | Peng L. et al. (2017) | [201] |

| Umbelliferone | Activation of Nrf2 and SIRT1/FOXO-3 with simultaneous inhibition of NFκB signalling | Ali F.E.M. et al. (2021) | [202] |

| Notopterol | Inhibition of JAK 2/3-STAT signalling | Wang Q. et al. (2020) | [203] |

| Tannins | |||

| Chebulagic acid, corilagin | Inhibition of NFκB and MAPK signalling pathways | Ekambaram S.P. et al. (2022) | [204] |

| Emblicanin | Binding to NFκB complex resulting in decrease of its activation | Husain I. et al. (2018) | [205] |

| Tannic acid (Gallotannin) | Inhibition of JAK/STAT signalling pathway and NFκB signalling pathway | Youness R.A. et al. (2021) | [206] |

| Punicalagin | Induction of Nrf2-HO-1 signalling through SIRT1 activation | Yu L.M. et al. (2019) | [207] |

| Punicalagin | Reduction of the expression of p-STAT6, Jagged1, and GATA3 protein | Yu L. et al. (2022) | [208] |

4.3.2. Effect of flavonoids on specific transcription factors

Flavonoids have an effect, similar to that of phenolic acids, on the NFκB transcription factor. The literature has reported on the inhibitory effect of baicalin, a glycosylated form of baicalein, on the activation of the NFκB transcriptional cascade by affecting the IKK/IkB/NFκB axis. Moreover, baicalin has a powerful inhibitory impact specifically on p-IkBα/IkBα; at the same time it produces no any statistically significant effect on p-IKKβ/IKKβ [170]. In addition to inhibiting NFκB, some flavonoids (fisetin) can also inhibit the MAPK axis (p38, ERK1/2 and JNK), Src and AKT [171]. Besides of inhibiting NFκB activation by affecting the IKK/IkB/NFκB axis, flavonoids can impact on the activation of the SIRT1 cascade, which blocks NFκB activation (myricetin), or on the NFκB activation through the TLR4 receptor (eriodictyol) [172,173]. Flavonoids are also reported as potent inhibitors of the JAK-STAT transcriptional cascade and activators of the HO-1/Nrf2 cascade [[174], [175], [176]]. Flavonoids are capable to activate the antioxidant response of the cell through PPARγ [177]. Cytotoxic effect of quercetin is mediated by p53-independent stimulation of apoptosis through the activation of transcription factor EB [178]. Flavonoids have an anti-migratory and anti-invasive impact on tumour cells that is mediated by the SIRT6 activation [179]. Robinin, a glycosylated flavonoid, can affect the RANKL cascade and reduce the intensity of osteoclastogenesis in bone tissue [180]. Additionally, flavonoids block the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [209].

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the most active catechin in green tea (Camellia sinensis). It is primarily regarded as an Nrf2 inducer, providing proteolysis of the inhibitory protein Keap1, followed by the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor Nrf2 and ARE activation [181,182]. This pathway enhances the activity of a number of enzymes of phase II biotransformation of xenobiotics (glutathione-S-transferase, NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase, uridine-5-diphosphate-glucuronyltransferase, heme oxygenase-1, etc.), which have antioxidant properties and reduce signs of inflammation [210]. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate can also inhibit a non-canonical pathway of NFκB activation [190,191]. Morin can also inhibit non-canonical NFκB signalling pathway through Wnt/PKC-α and JAK-2/STAT3 signalling pathways [192].

In the laboratory of Q.P. Dou, green tea polyphenols (especially EGCG) were shown to act as potent and specific inhibitors of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26 S proteasome both in vitro and in vivo [183]. This disrupts the uncoupling of the inhibitory protein IκB from NFκB and its ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal proteolysis that prevents NFκB activation. In addition, EGCG can activate caspase-mediated proteolytic cleavage of the NFκB/p65 subunit [184] and inhibits IKKβ activity [185].

It has also been found out that EGCG is able to restrain carcinogenesis in various tissues by inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) and transcription factor AP1 [211].

In the modern view, the antioxidant effect of quercetin, its glycosides and metabolites, known as one of the mechanisms to implement many of its pharmacological properties, is largely related to their capability to inhibit NFκB signalling and activate the transcription factor Nrf2. The recent molecular biological studies have demonstrated that quercetin suppresses the NFκB activation by inhibiting the 26 S proteasome, which promotes ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of the inhibitory protein IκB, and the latter, in turn, forms a complex with dimers of NFκB family proteins [186]. As a consequence, there is no expression of genes encoding the biosynthesis of a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-oxidant proteins. Another study indicates the capability of quercetin to reduce the synthesis of p65, a protein belonging to the NFκB family [187]. The administration of quercetin decreased the expression of the IkBα gene in patients with stable coronary artery disease [188].

It has been shown the inhibitory effect of quercetin on the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α [189] and cardioprotective properties primarily relates to its impact on the transcriptional factors rather than to its direct inhibitory function [212].

4.3.3. Effects of stilbenes on specific transcription factors

The natural phytoalexin resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene) is a derivative of trans-stilbene. It possesses multidirectional biological properties including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antiproliferative, and antioxidant actions [[213], [214], [215], [216], [217]].

The first report on the molecular mechanisms of the resveratrol action was published in 2003 [218]. This work showed that resveratrol can modulate the activity of SIRT1, a critical deacetylase that affects the acetylation status of p53 and DNA repair enzymes.

At present, SIRT1-mediated reactions of deacetylation of proteins, mainly localized in nuclei of various types of cells are considered as the most widely studied [128]. Targets of SIRT1 include transcription factors NFκB, forkhead box protein (FOXO) 1 and 3, STAT3, p53, hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif protein (HEY) 2, PPAR-γ and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC) 1α, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), apurinic/apyrimidine endonuclease 1, angiotensin II type 1 receptor, estrogen receptor-α. Androgen receptor, uncoupling proteins (UCP) 2 and 3, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose-1,6-diphosphatase, glucose-6-phosphatase, histones H1, H3 and H4 [216,217,193].

Resveratrol has been shown to reduce SIRT1-dependent acetylation of the NFκB subunit RelA/p65. This polyphenol can also weaken the phosphorylation of the key regulator of autophagy, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and ribosomal protein S6 in mammals, thus alleviating the course of inflammation. Researchers demonstrate that resveratrol suppresses TNF-α-induced inflammatory markers through SIRT1: this can suggest that SIRT1 is an effective target to regulate inflammation [194].

Resveratrol, like other polyphenols from the stilbene class, reduces the NFκB activity by directly affecting its activation and indirectly by reducing its activation through AKT/GSK3β-Nrf2/NFκB signalling [195]. A more selective effect on IkBβ and a minor effect on IkBα are typical for stilbenes [196]. Stilbenes are also capable to inhibit STAT3 signalling, which mediates their antitumour effects [197]. Another mechanism providing antitumour effects of stilbenes is the stimulation of the expression of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) that is realized by NFκB cascade activation in tumour cells [198]. Stilbenes are also known for cardioprotective effects on doxorubicin-associated cytotoxicity by activating Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) [199].

4.3.4. Effect of coumarins on specific transcription factors

Coumarins are potent inhibitors of the activation of the transcription factor NFκB. This effect is achieved through the IΚK/IκBα/NFκB axis by analogy to phenolic acids [200]. Also, coumarins can inhibit NFκB indirectly through the AKT inhibition or the AMPK activation [201]. Another mode of NFκB-mediated blockade by coumarins is the activation of genes controlled by SIRT1, FOXO-3, PPAR-γ, and Nrf2 [202]. Coumarins are also known as potent STAT3 inhibitors [203].

4.3.5. Effect of tannins on specific transcription factors

Considering the low solubility of natural tannins in water and, accordingly, in intestinal juice, the systemic effect on transcription factors is specific only to those tannins that have a relatively high capacity to undergo hydrolysis. These compounds have an inhibitory effect on NFκB and MAPK cascades [204]. Some tannins (emblicanin) are capable to bind directly to NFκB protein complex [205]. Chestnut tannins demonstrate the capability to increase the phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3, thus modulating the production of IL-6 and contributing to the formation of an immune response against bacteria [219]. On the other hand, the literature provides data on the inhibitory effect of tannic acid on STAT3 [206]. Therefore, the effect on STAT3 largely depends upon the structural peculiarities of tannin when comparing with the effects on NFκB. Following hydrolysis, some tannins (punicalagin) are able to activate the Nrf2 – HO-1 cascade via the modulation of SIRT1-controlled genes [207]. Punicalagin also demonstrates anti-allergic properties by inhibiting STAT6 [208].

The effects of polyphenols on transcription factors can summarized as shown in Fig. 3 (Fig. 3). Most polyphenols have an inhibitory effect on the NFκB and STAT activation that stimulates the Nrf2 activation. This multimodal action mediates the anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic properties of polyphenols.

Fig. 3.

Potential role of polyphenolic compounds in the formation of Systemic Inflammatory Response (SIR). Having entered the alimentary canal, polyphenolic compounds are absorbed into the bloodstream. All phenolic compounds can scavenge reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen (RNS) species due to their structural peculiarities. Thus they can prevent initial influence of ROS and RNS on redox-sensitive transcriptional factors in the cell. Flavonoids, stilbenes, coumarins and tannins exert most of their influence through SIRT1 or SIRT6, thus inhibiting NFκB and STAT signalling, while inducing Nrf2 signalling. Phenolic acids, stilbenes, coumarins and tannins can directly inhibit STAT signalling. All phenolic compounds are potent activators of Nrf2. Flavonoids and phenolic acids additionally inhibit NFκB through IκBα. Some of phenolic acids and flavonoids can also inhibit NFκB activation through non-canonical (NIK) pathway. Note: Pa – phenolic acids; Fl – flavonoids; St – stilbenes; Cu – coumarins; Ta – tannins.

Notably, the combined administration of polyphenols is more effective than their separate use. The experiment on white rats showed that the combined use of EGCG and quercetin in LPS-induced SIR significantly suppressed the development of oxidative-nitrosative stress in the periodontal tissues of rats by reducing the ROS/RNS production that was accompanied by the improvement in the functional state of the periodontium [89]. In the other study, the authors emphasize the role of the combined effect of EGCG and quercetin in restraining depolymerization of periodontal extracellular matrix proteins (collagen, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins) under the conditions of LPS administration [88]. The series of experimental works confirm the expediency of combining water-soluble form of quercetin and SR 11302, an inhibitor of AP1 transcription factor, under LPS-induced SIR [220], as well as with metformin, which is able to suppress the NFκB activation under water avoidance stress [221].

Considering the low natural bioavailability of polyphenols, the studies of Ukrainian scientists aimed at increasing the solubility of these compounds in water and other polar solvents, or facilitating the absorption of polyphenols by introducing carbohydrates, are particularly relevant in that respect. The creation of a medicinal complex with polyvinylpyrrolidone enabled to obtain a water-soluble medicinal form of quercetin, namely Corvitin (0.5 g lyophilisate for injection), for parenteral administration that generally proved as effective means in preventing HGSIP formation by reducing the intensity of the cytokine storm in patients with COVID-19 [222]. Quercetin-containing drug Quertin (chewable tablets of 40 mg) are also present on the pharmaceutical market of Ukraine. Inclusion of carbohydrate-containing components in this medicine enhances the solubility and bioavailability of sparingly soluble flavonoids [223]. The oral dosage form of quercetin enables long-term administration of the drug, for example, in stable coronary heart disease, atherosclerosis, chronic glomerulonephritis, purulent and inflammatory diseases of soft tissues. All these diseases are accompanied by the LGSIP formation.

5. Conclusions

Thus, the current scientific knowledge has convincingly proven the leading role of redox-sensitive transcription factors as mechanisms of formation of low- and high-grade systemic inflammatory phenotypes as variants of systemic inflammatory response. These phenotypic variants underlie the pathogenesis of the most dangerous diseases of internal organs, endocrine and nervous systems, surgical pathologies and post-traumatic disorders.

The use of individual chemical compounds of the class of polyphenols, or their combinations, capable of modulating several transcription factors, including NFκB, STAT3, AP1 and Nrf2, can be an effective technology in the therapy of systemic inflammatory response: this enables to cut down the risks associated with the side effects of artificial specific modulators of transcription factors.

Taking into account the pharmacokinetic peculiarities of most chemical compounds of the polyphenol families, it should be noted that administering natural polyphenols in oral dosage forms is very beneficial in the therapy and management of the number of diseases accompanied with low-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype. At the same time, the therapy of diseases associated with high-grade systemic inflammatory phenotype requires medicinal phenol preparations for parenteral administration. Saturation of the pharmaceutical market with adequate medicinal forms of polyphenols will significantly enrich the arsenal of means for the treatment of diseases associated with systemic inflammatory response.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statment

This research did not receive any specific grant or funding.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Chovatiya R., Medzhitov R. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 2014;54(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y., Liu S., Leng S.X. Chronic low-grade inflammatory phenotype (CLIP) and senescent immune dysregulation. Clin. Therapeut. 2019;41(3):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panigrahy D., Gilligan M.M., Serhan C.N., Kashfi K. Resolution of inflammation: an organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;227 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vulesevic B., Sirois M.G., Allen B.G., de Denus S., White M. Subclinical inflammation in heart failure: a neutrophil perspective. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018;34(6):717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herder C., Hermanns N. Subclinical inflammation and depressive symptoms in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019;41(4):477–489. doi: 10.1007/s00281-019-00730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghazala R.A., El Medney A., Meleis A., Mohie El Dien P., Samir H. Role of anti-inflammatory interventions in high-fat-diet-induced obesity. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2020;34(3) doi: 10.1002/bmc.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge X., Jing L., Zhao K., Su C., Zhang B., Zhang Q., Han L., Yu X., Li W. The phenolic compounds profile, quantitative analysis and antioxidant activity of four naked barley grains with different color. Food Chem. 2021 Jan 15;335 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Páramo J.A. Inflammatory response in relation to COVID-19 and other prothrombotic phenotypes. Reumatol. Clínica. 2022;18(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.reumae.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vieira E., Mirizio G.G., Barin G.R., de Andrade R.V., Nimer N.F.S., La Sala L. Clock genes, inflammation and the immune system-implications for diabetes, obesity and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(24):9743. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh H., Ueda M., Suzuki M., Kohmura-Kobayashi Y. Developmental origins of metaflammation; A bridge to the future between the DOHaD theory and evolutionary biology. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.839436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark K., Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021;18(9):666–682. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]