Abstract

Moraxella catarrhalis strain 25238 detoxified lipooligosaccharide (dLOS)-protein conjugates induced a significant rise of bactericidal anti-LOS antibodies in animals. This study reports the effect of active or passive immunization with the conjugates or their antiserum on pulmonary clearance of M. catarrhalis in an aerosol challenge mouse model. Mice were injected subcutaneously with dLOS-tetanus toxoid (dLOS-TT), dLOS–high-molecular-weight proteins (dLOS-HMP) from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), or nonconjugated materials in Ribi adjuvant and then challenged with M. catarrhalis strain 25238 or O35E or NTHi strain 12. Immunization with dLOS-TT or dLOS-HMP generated a significant rise of serum anti-LOS immunoglobulin G and 68% and 35 to 41% reductions of bacteria in lungs compared with the control (P < 0.01) following challenge with homologous strain 25238 and heterologous strain O35E, respectively. Serum anti-LOS antibody levels correlated with its bactericidal titers against M. catarrhalis and bacterial CFU in lungs. Additionally, immunization with dLOS-HMP generated a 54% reduction of NTHi strain 12 compared with the control (P < 0.01). Passive immunization with a rabbit antiserum against dLOS-TT conferred a significant reduction of strain 25238 CFU in lungs in a dose- and time-dependent pattern compared with preimmune serum-treated mice. Kinetic examination of lung tissue sections demonstrated that antiserum-treated mice initiated and offset inflammatory responses more rapidly than preimmune serum-treated mice. These data indicate that LOS antibodies (whether active or passive) play a major role in the enhancement of pulmonary clearance of different test strains of M. catarrhalis in mice. In addition, dLOS-HMP is a potential candidate for a bivalent vaccine against M. catarrhalis and NTHi infections.

Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis has emerged as a significant human pathogen and may be the cause of more childhood infectious diseases than previously thought (8, 16, 33). The most M. catarrhalis-susceptible populations are very young children and the elderly. In young children, M. catarrhalis is the third-most-common cause of otitis media, associated with 15 to 20% of all cases reported, following Streptococcus pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) (6, 17). More than 70% of children are likely to experience at least one episode of otitis media by the age of 3 years (41). Recurrent or chronic otitis media can lead to hearing and/or speech impairment or to language delay. M. catarrhalis is also a significant cause of sinusitis and persistent cough in young children (2, 25). In the elderly, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases or compromised immune systems, M. catarrhalis can account for lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchitis or pneumonia. Although invasive diseases caused by M. catarrhalis such as bacteremia, meningitis, and endocarditis are less common, they can be fatal (11, 30, 32). Currently, the rate of β-lactamase-producing strains in some areas of the United States has increased to 95% (12), and more clinical isolates are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics (24).

Active immunization with an effective vaccine would be an efficient approach to prevent M. catarrhalis infections. Much research has been performed on the outer membrane protein antigens of M. catarrhalis in an attempt to identify potential vaccination antigens (9, 28, 34, 35). This approach has led to the identification of several outer membrane proteins, such as the ubiquitous surface protein A (UspA), B1, B2, CD, and E. Some of these antigens have been reported to be protective in a murine model of human diseases (9, 34). Currently there is no vaccine available to prevent the diseases caused by M. catarrhalis, largely because the pathogenic mechanism and the host immune response to this pathogen have yet to be clarified.

The lipooligosaccharide (LOS) molecule is a prominent surface component of M. catarrhalis and has been implicated as a virulence factor important in the pathogenesis of this organism (13, 21). Less attention has been paid to M. catarrhalis LOS as a vaccine component due to its toxicity and weak immunogenicity in vivo. However, LOS has several characteristics that make it an attractive vaccine candidate. Serum antibodies to LOS developed in patients with M. catarrhalis infections (36) and the convalescent-phase anti-LOS immunoglobulin G (IgG) demonstrated bactericidal activity against M. catarrhalis (40). In addition, the serological properties of LOS in humans suggest a less variable structure of LOS (36). Only three major antigenic types of M. catarrhalis LOS can be distinguished, and more than 90% of 302 strains expressed one of three LOS serotypes (A, 61%; B, 29%; C, 5%) (44). It is possible that a vaccine candidate including two to three types of LOS would generate anti-LOS antibodies with bactericidal activity against majority of the pathogenic strains of M. catarrhalis.

The LOS molecule is too toxic to be administered to humans in its native form, and detoxified LOS (dLOS; hapten) does not elicit antibodies in vivo. In a previous study, we used M. catarrhalis strain 25238 as a source of LOS (serotype A) and covalently bound the dLOS to a carrier protein, tetanus toxoid (TT), or to a high-molecular-weight protein (HMP) from NTHi strain 12. Both proteins improved the immunogenicity of the dLOS. The results demonstrated that these conjugates were immunogenic and induced bactericidal antibodies against the homologous strain as well as some heterologous strains when these tested in animals (26). In this study we further evaluated the protective effect of these conjugates on the pulmonary clearance of M. catarrhalis homologous strain 25238, heterologous strain O35E, and NTHi strain 12, using an aerosol challenge mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice (5 or 10 weeks of age) were obtained from Taconic Farms Inc. (Germantown, N.Y.). The mice were housed in an animal facility in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines under animal study protocol 850-98.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

M. catarrhalis prototype strain 25238 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). Clinical isolates of M. catarrhalis strain O35E (43) and NTHi strain 12 (3) were provided by E. J. Hansen and S. J. Barenkamp, respectively. These strains were grown on chocolate agar at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 16 h; then three to five clones were transferred to new plates and incubated for 3.5 to 4 h, or until mid-logarithmic phase. Each bacterial suspension was prepared to a desired concentration with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0) containing 0.1% gelatin, 0.15 mM CaCl2, and 0.5 mM MgCl2 and stored on ice until use. The bacterial concentration was determined by a 65% transmission at 540 nm. The final bacterial number was confirmed by counting the CFU after overnight incubation of the plates at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Conjugate vaccines.

Conjugates were obtained and prepared as described previously (26). The toxicity of dLOS before conjugation was only 1 endotoxin unit/μg, which was 20,000-fold lower than that of LOS as determined by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay. The composition of dLOS-TT was 103 μg of dLOS and 266 μg of TT per ml, with a molar ratio of dLOS to TT of 19:1; the composition of dLOS-HMP was 220 μg of dLOS and 280 μg of HMP per ml, with a molar ratio of 31:1.

Active immunization.

A total of 130 5-week-old mice were divided randomly into three challenge groups: homologous M. catarrhalis strain 25238, heterologous M. catarrhalis strain O35E, and NTHi strain 12. Mice were immunized subcutaneously with 5 μg of dLOS-TT or dLOS-HMP (carbohydrate content) in 0.2 ml of normal saline mixed with Ribi-700 adjuvant (containing 50 μg of monophosphoryl lipid A and 50 μg of synthetic trehalose dicorynomycolate) (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc., Hamilton, Mont.) or with 0.2 ml of an estimated 2 × 107 CFU of M. catarrhalis strain 25238, O35E, or NTHi strain 12 fixed in 0.1% formalin. The control mice were injected with 5 μg of dLOS plus 5 μg of HMP from NTHi and/or 5 μg of TT or with 5 μg of HMP alone in 0.2 ml of saline with Ribi-700 adjuvant. All mice (10 for each group) were given a total of three injections at 2-week intervals, with the last injection 1 week before bacterial challenge.

Passive immunization.

Rabbit preimmune serum (preserum) and postimmune serum elicited by dLOS-TT were obtained as described elsewhere (26). Anti-LOS antibody titer in rabbit antiserum was 1:72,900. Sera were diluted to 50, 10, and 2% in saline, and then 1 ml of diluted antiserum or preserum was administered intraperitoneally to each 10-week-old mouse 17 h prior to a bacterial aerosol challenge (10 mice per group).

Bacterial aerosol challenge.

The bacterial aerosol challenges were carried out in an inhalation exposure system (Glas-col, Terre Haute, Ind.) (29). Conditions were as follows: challenge doses of bacteria, 108 to 109 CFU/ml × 10 ml in the nebulizer; nebulizing time, 40 min; vacuum flowmeter, 60 standard ft3/h; and compressed air flowmeter, 10 ft3/h.

Measurement of bacterial clearance from mouse lungs.

Eight mice from each group were euthanized with an overdose inhalation of Metophane (Mallinckrodt Veterinary Inc., Mundelein, Ill.); lungs were removed under sterile conditions for the active immunization protocol at 6 h postchallenge and for the passive immunization protocol at 0, 3, and 6 h postchallenge. Blood samples were also collected, and aliquots of sera were stored at −70°C for later antibody quantification. Lung tissues were homogenized in 5 ml of PBS for 1 min at low speed in a tissue homogenizer (Stomacher Lab System 80, Seward Ltd., London, England). Each homogenate was diluted serially in PBS, and 50-μl aliquots of the homogenate and diluted samples were plated on chocolate agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight, and the bacterial colonies were counted. The minimum number of viable bacteria that could be detected was 100 CFU per lung. The counting error of these determinations was usually less than 40% of the mean.

ELISA.

Serum IgG titers against M. catarrhalis strain 25238 LOS or NTHi strain 12 HMP were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (4, 27). Briefly, 96-well plates (Immuno I) were coated with M. catarrhalis strain 25238 LOS (10 μg/ml) in PBS (pH 7.4) with 10 mM MgCl2 or with NTHi strain 12 HMP (5 μg/ml) in 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 9.8) overnight at 4°C. On the following day, the plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS for 1 h. The diluted sera were added, and the plate was incubated for 3 h. Alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; Sigma) was added during a 2-h incubation. Diluent for sera and conjugates was 1% bovine serum albumin–PBS–0.05% Tween 20. All steps were performed at room temperature, and PBS–0.05% Tween 20 was used for washing five times. After the AP substrate was added, the plate was incubated for 1 h, and the reactions were read with a microplate autoreader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vt.) at A405. A mouse antiserum against M. catarrhalis strain 25238 or NTHi strain 12 and a rabbit antiserum against M. catarrhalis 25238 dLOS-TT were used as positive controls. Negative controls included buffer, AP conjugate, and presera. All negative controls gave optical density readings of less than 0.1. The antibody endpoint titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum giving an A405 twofold greater than that of presera.

Bactericidal assay.

Sera were inactivated at 56°C for 30 min and measured for bactericidal activity against M. catarrhalis strains 25238 and O35E. A complement-mediated bactericidal assay was performed as described previously (27) except that a guinea pig serum (5 μl per well; Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., San Diego, Calif.); was used as a source of complement and the reaction plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min before plating onto agar plates. The bactericidal titer was determined to be the last dilution of serum causing at least 50% killing.

Histological examination.

Two mice from each group were euthanized; their lungs were removed and fixed in 10% formalin with PBS at 0, 3, and 6 h postchallenge for the passive immunization protocol and at 6 h postchallenge for the active immunization protocol. The lung specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical analysis.

The viable bacteria were expressed as the mean CFU of n independent observations ± the standard deviation (SD). Geometric means of bactericidal titers and reciprocal antibody IgG titers were determined. Significance was determined by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Effect of active immunization on bacterial clearance from mice.

An ELISA was used to determine the relative levels of M. catarrhalis strain 25238 LOS-specific and NTHi strain 12 HMP-specific IgG antibodies in the vaccinated mouse sera. The mixture of unconjugated dLOS, HMP, and TT was not immunogenic, judging by LOS antibody level after three injections (Tables 1 and 2). However, both conjugates could elicit an approximately 100-fold increase in the level of LOS antibodies compared with the mixture group. Immunization with whole cells from strains 25238 and O35E seemed to elicit a higher LOS antibody level than the conjugate groups, but no significant difference was observed (P > 0.05). Three injections of dLOS-HMP or HMP resulted in an 80- to 90-fold increase of serum IgG directed against HMP compared to the control animals (Table 3).

TABLE 1.

Effect of active immunization with dLOS-TT and dLOS-HMP on bacterial recovery of homologous strain 25238 in mouse lungsa

| Immunogen | Anti-LOS IgG titerb | Bacterial recoveryc (CFU/lung) | Bacterial reductiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dLOS-TT + Ribi | 1,223 (90–7,290) | (2.3 × 103) ± 0.9e | 68 |

| dLOS-HMP + Ribi | 1,846 (810–7,290) | (2.3 × 103) ± 0.8e | 68 |

| Strain 25238 | 3,198 (810–7,290) | (1.3 × 103) ± 0.3e | 82 |

| dLOS + TT + HMP + Ribi (control) | 12 (10–30) | (7.1 × 103) ± 2.3 | 0 |

Mice were challenged with 108 CFU of M. catarrhalis strain 25238 per ml in a nebulizer, and lungs were collected at 6 h postchallenge.

Levels of serum antibody against strain 25238 LOS, expressed as reciprocal geometric mean (range) of eight mice per group, were detected by ELISA.

Mean ± SD of eight mice.

Compared with the control group.

P < 0.01 compared with the control group.

TABLE 2.

Effect of active immunization with dLOS-TT and dLOS-HMP on bacterial recovery of heterologous strain O35E in mouse lungsa

| Immunogen | Anti-LOS IgG titerb | Bacterial recoveryc (CFU/lung) | Bacterial reductiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dLOS-TT + Ribi | 1,223 (90–7,290) | (4.0 × 104) ± 1.6e | 41 |

| dLOS-HMP + Ribi | 2,430 (90–7,290) | (4.4 × 104) ± 1.3e | 35 |

| Strain O35E | 2,788 (810–7,290) | (4.4 × 104) ± 1.4e | 35 |

| dLOS + TT + HMP + Ribi (control) | 15 (10–30) | (6.8 × 104) ± 1.5 | 0 |

Mice were challenged with 4 × 109 CFU of M. catarrhalis strain O35E per ml in a nebulizer, and lungs were collected at 6 h postchallenge.

Levels of serum antibody against strain 25238 LOS, expressed as reciprocal geometric mean (range) of eight mice per group, were detected by ELISA.

Mean ± SD of eight mice.

Compared with the control group.

P < 0.01 compared with the control group.

TABLE 3.

Effect of active immunization with dLOS-TT and dLOS-HMP on bacterial recovery of NTHi strain 12 in mouse lungsa

| Immunogen | Anti-HMP IgG titerb | Bacterial recoveryc (CFU/lung) | Bacterial reductiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dLOS-TT + Ribi | 13 (10–30) | (1.1 × 105) ± 3.1 | 8 |

| dLOS-HMP + Ribi | 1,066 (90–2,430) | (5.5 × 104) ± 1.4e | 54 |

| Strain 12 | 1,403 (270–7,290) | (4.7 × 104) ± 2.2e | 61 |

| HMP + Ribi | 929 (90–2,430) | (6.2 × 104) ± 2.2e | 48 |

| dLOS + TT + Ribi (control) | 12 (10–30) | (1.2 × 105) ± 3.5 | 0 |

Mice were challenged with 6 × 109 CFU of NTHi strain 12 per ml in a nebulizer, and their lungs were collected at 6 h postchallenge.

Levels of serum antibody against strain NTHi strain 12 HMP, expressed as reciprocal geometric mean (range) of eight mice per group, were detected by ELISA.

Mean ± SD of eight mice.

Compared with the control group.

P < 0.01 compared with the control group.

One week after the final immunization, mice from each group were challenged with M. catarrhalis homologous strain 25238, heterologous strain O35E, or NTHi strain 12. When challenged with strain 25238, the number of bacteria recovered from lungs at 6 h postchallenge was significantly (68%) reduced in both conjugate-immunized groups compared to the control group (P < 0.01) (Table 1). The degree of clearance was similar to that observed in the group immunized with strain 25238 whole cells. As shown in Table 2, when strain O35E was used as the challenge organism, the protective effect of immunization was also significant. The number of bacteria in the lungs from both conjugate-immunized groups decreased from 35 to 41% compared to the control group at 6 h postchallenge (P < 0.01). A similar protective effect was observed in the strain O35E whole-cell-immunized group. When mice were challenged with NTHi strain 12, the bacterial number recovered from the lungs of the dLOS-HMP group, but not the dLOS-TT group, was reduced significantly (54%) compared with the control group (P < 0.01) (Table 3). This reduction rate was similar to that observed in the group immunized with whole cells or HMP.

The relationships between serum anti-LOS antibody levels and bacterial recoveries from the lungs were analyzed. There were inverse correlations between anti-LOS antibody levels and the bacterial recoveries for strains 25238 (Table 1; r = −0.58, P < 0.01) and O35E (Table 2; r = −0.66, p < 0.01).

A bactericidal test showed that all mouse sera from the control groups gave no detectable bactericidal activity. In contrast, 88 or 80% of conjugate-immunized sera showed bactericidal activity against strain 25238 at a mean titer of 1:4.4 or strain O35E at 1:2.3, respectively. There was a positive correlation between serum antibody levels and bactericidal titers for strain 25238 (r = 0.82, P < 0.01) but not for strain O35E.

Effect of passive immunization on bacterial clearance from mouse lung.

The preceding experiments suggested that specific antibody in the systemic circulation enhanced pulmonary clearance in the conjugate-immunized mice. To test this hypothesis, passive immunization experiments were conducted with a specific rabbit antiserum elicited against M. catarrhalis strain 25238 dLOS-TT. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 50% rabbit anti-dLOS-TT or rabbit preserum and challenged with M. catarrhalis strain 25238 17 h later. The bacterial reductions in the lungs from antiserum-treated mice were 33, 49, and 66%, respectively, at 0, 3, and 6 h postchallenge compared to the preserum-treated groups (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) (Table 4). When the time point was set to 6 h postchallenge, the number of bacteria was reduced significantly, by 39 and 67% in the 10 and 50% antiserum-treated groups, respectively, compared to the preserum-treated group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01) (Table 5). No difference in bacterial CFU was observed between the 2% antiserum-treated group and the preserum-treated group. The difference in bacterial CFU was also significant between 10 and 50% antiserum-treated groups (P < 0.01). Serum antibody examination of the antiserum-treated groups showed high IgG titers against strain 25238 LOS compared with the preserum-treated group, which were dependent on the dose of the adoptive antiserum (Table 5). Taken together, passive immunization with the antiserum enhanced the pulmonary clearance of M. catarrhalis in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

TABLE 4.

Effect of passive immunization with rabbit antiserum elicited by dLOS-TT on bacterial recovery of homologous strain 25238 in mouse lungsa

| Time (h) postchallenge | Bacterial recoveryb (CFU/lung)

|

Bacterial reductionc (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preserum | Antiserum | |||

| 0 | (5.4 × 105) ± 1.2 | (3.6 × 105) ± 1.1 | 33 | <0.05 |

| 3 | (1.7 × 105) ± 0.5 | (8.7 × 104) ± 3.6 | 49 | <0.01 |

| 6 | (3.8 × 104) ± 1.1 | (1.3 × 104) ± 0.2 | 66 | <0.01 |

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 50% antiserum or preserum 17 h prior to a bacterial aerosol challenge with 4 × 108 CFU of M. catarrhalis strain 25238 per ml in a nebulizer.

Mean ± SD of eight mice.

Compared with the preserum-treated group.

TABLE 5.

Effect of passive immunization with different doses of antiserum elicited by dLOS-TT on bacterial recovery of the homologous strain in mouse lungsa

| Dose (1 ml/mouse) | Anti-LOS IgG titerb | Bacterial recoveryc (CFU/lung) | Bacterial reductiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50% antiserum | 14,485 (65,610–7,290) | (2.1 × 104) ± 0.9e | 67 |

| 10% antiserum | 4,828 (7,290–2,430) | (4.6 × 104) ± 1.5f | 39 |

| 2% antiserum | 205 (270–90) | (6.7 × 104) ± 2.1 | −5 |

| 50% preserum | <30 | (6.4 × 104) ± 3.1 | 0 |

Mice were challenged with 5 × 108 CFU of M. catarrhalis strain 25238 per ml in a nebulizer, and lungs were collected at 6 h postchallenge.

Levels of serum antibody against M. catarrhalis strain 25238 LOS, expressed as reciprocal geometric mean (range) of eight mice per group, were detected by ELISA.

Mean ± SD of eight mice.

Compared with 50% preserum-treated group.

P < 0.01 compared with any other group.

P < 0.05 compared with 50% preserum-treated group.

Histopathologic lesions of lungs.

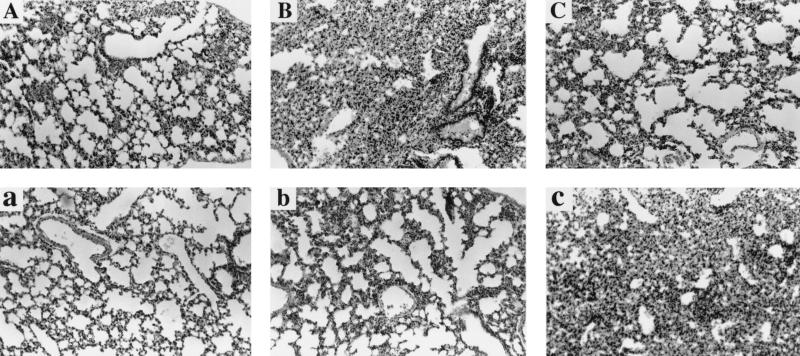

The lungs demonstrated capillary congestion with widened alveolar septa. In the alveolar space there was substantial exudate with focal hemorrhage. The exudate was comprised of macrophages, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, and proteinaceous fluid. These pathological changes existed throughout the course of the 6-h postchallenge in both antiserum-treated and preserum-treated groups. However, the pathological changes in the antiserum-treated group appeared earlier. The peak of the pathological changes was 3 h postchallenge for the antiserum-treated group and 6 h postchallenge for the preserum-treated group (Fig. 1). In the active immunization protocol, the inflammatory changes of lungs in each conjugate-immunized group were decreased at 6 h postchallenge compared with the control group except for the LOS-TT-treated group challenged with NTHi strain 12, in which there were no obvious differences from the control group (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Dynamics in pathological changes of lung tissues at 0, 3, and 6 h postchallenge in antiserum-treated mice (A to C) and preserum-treated mice (a to c) (hematoxylin-eosin stain; magnification, ×100).

DISCUSSION

The active immunization of mice with either of two dLOS-protein conjugates elicited a significant rise of anti-LOS IgG in the sera and resulted in an enhanced clearance of bacteria from the lungs following an aerosol challenge with the homologous strain 25238 or the heterologous strain O35E. Since there was a significant correlation between serum anti-LOS antibody levels and bacterial CFU recovered from the lungs, it is postulated that the accelerated removal of M. catarrhalis from the lungs after active immunization with the conjugates is specifically due to the anti-LOS antibody. To address this question directly, mice were passively immunized with a rabbit antiserum to dLOS-TT, and a remarkable enhancement of strain 25238 clearance was observed in the lungs in a dose- and time-dependent manner. These results suggest that the conjugate-induced serum antibodies played a pivotal role in the observed immunoprotection. In mammals, IgG predominates in the alveolar lining liquid of the normal lungs and increases during acute inflammation (14). It is possible that in the present study the specific IgG antibody contributed to the bacterial clearance by passing from the blood into the lungs before or soon after an aerosol challenge. Increased pulmonary levels of antibody would be expected with the rapid inflammatory response following an aerosol challenge seen in antiserum-treated mice.

Antibody in the serum kills these bacteria, or at least inhibits the amount of bacterial growth, primarily by activation of the complement system and promotion of the opsonophagocytosis of the bacteria (18, 23). In our study, we found that most of the immune sera showed complement-mediated bactericidal activity against M. catarrhalis and the correlation between serum antibody levels and its bactericidal titers was significant, indicating that bactericidal activity of serum anti-LOS antibody takes part in enhancement of bacterial clearance from the lungs.

Histopathological examination of both antiserum-treated and preserum-treated mice showed an acute inflammatory response within the lungs. Both macrophages and neutrophils were found as major components of the exudate within the inflammatory lungs. These two kinds of phagocytic cells are important in the pulmonary clearance of aerosolized bacteria in mice (42). Phagocyte recruitment into the lungs is considered to be the result of chemotaxis due to the challenge bacteria. The chemotaxis may have been enhanced by the anti-LOS IgG-bacterium complex, because this complex may trigger the complement cascade and activate macrophages, which bear receptors for IgG, via the Fc fragment of the IgG (7). Some chemotaxins could result from the activation of complement, such as C5a and C3a (31, 45). Meanwhile, the activated macrophages may secrete many cytokines, including macrophage inflammatory peptides 1 and 2, which are chemotaxins (15). The bacterium-specific antibody in the lungs could increase opsonization and phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils to destroy the bacteria (37, 38). This is partly because these phagocytes are able to adhere to the antibody- or complement component-coated bacteria by virtue of their IgG Fc or complement receptors (1, 10, 20). In this study, the inflammatory response was found to be regulated upward and then downward in antiserum-treated mice earlier than in preserum-treated mice. It is speculated that antiserum treatment primes clearance and also sets the scene for a faster decline of the inflammatory response than in the preserum-treated mice.

TT is a common and useful protein carrier for conjugate vaccines due to its safety, stability, and immunogenicity. However, suppression of the immune response could also occur when many conjugate vaccines containing the same protein component, TT, are administered simultaneously (19, 39). In addition, suppression of the immune response could occur with conjugate vaccines using TT as a carrier when anti-TT antibody preexists from vaccination or passive maternal antibody exchange to the fetus (5). Conjugation to alternative proteins may circumvent these problems. HMPs are a kind of adhesion molecules from NTHi strain 12 which are expressed in 75% of the 125 heterologous NTHi strains tested (4). NTHi is a pathogen with a disease spectrum similar to that of M. catarrhalis (22). In a covalent reaction between dLOS and HMP, there is a risk of destroying or/and modifying essential epitopes of HMP through direct covalent linkage or steric hindrance, resulting in failure of antibody induction against native HMP. However, our study confirmed that dLOS-HMP could elicit antibodies not only to M. catarrhalis LOS but also to native HMP. dLOS-HMP immunization enhanced clearance of NTHi strain 12 similar to the enhancement observed in HMP immunization by itself. These data indicate that HMP could be an effective carrier protein for M. catarrhalis LOS or other LOS and polysaccharides and that such a conjugate could function as a bivalent vaccine, preventing the diseases caused by both M. catarrhalis and NTHi.

In summary, M. catarrhalis LOS is a promising vaccine candidate for the prevention of diseases caused by M. catarrhalis. HMP can be used as an effective protein carrier for conjugate vaccines, and the combination of M. catarrhalis dLOS and NTHi HMP may be a potential bivalent vaccine against diseases caused by both M. catarrhalis and NTHi. Further studies are needed to characterize the protective mechanism for conjugates to enhance the pulmonary clearance of M. catarrhalis, especially the cooperation among B cells, T cells, and antigen-presenting cells in the model. Such studies are also needed to incorporate some M. catarrhalis type B and C dLOS and outer membrane proteins into conjugate vaccines for the purpose of enhancing protection and covering the majority of the pathogenic M. catarrhalis strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. J. Hansen for providing M. catarrhalis strain O35E and S. J. Barenkamp for providing NTHi strain 12 and HMP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aderem A, Underhill D M. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamberger D M. Antimicrobial treatment of sinusitis. Semin Respir Infect. 1991;6:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barenkamp S J, Bodor F F. Development of serum bactericidal activity following nontypable Haemophilus influenzae acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barenkamp S J, Leininger E. Cloning, expression, and DNA sequence analysis of genes encoding nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae high-molecular-weight surface-exposed proteins related to filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1302-1313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barington T, Gyhrs A, Kristensen K, Heilmann C. Opposite effects of actively and passively acquired immunity to the carrier on responses of human infants to a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:9–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.9-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluestone C D. Otitis media and sinusitis in children. Role of Branhamella catarrhalis. Drugs. 1986;31(Suppl. 3):132–141. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198600313-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carayannopoulos L, Capra J D. Immunoglobulin. In: Paul W E, editor. Fundamental immunology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 283–314. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catlin B W. Branhamella catarrhalis: an organism gaining respect as a pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:293–320. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, McMichael J C, VanDerMeid K R, Hahn D, Mininni T, Cowell J, Eldridge J. Evaluation of purified UspA from Moraxella catarrhalis as a vaccine in a murine model after active immunization. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1900–1905. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1900-1905.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper J M, Rowley D. Clearance of bacteria from lungs of mice after opsonising with IgG or IgA. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1979;57:279–285. doi: 10.1038/icb.1979.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daoud A, Abuekteish F, Masaadeh H. Neonatal meningitidis due to Moraxella catarrhalis and review of the literature. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1996;16:199–201. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1996.11747826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Pierce G, Hogan T, Holley H P, Jr, Rauch A. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among 723 outpatient clinical isolates of Moraxella catarrhalis in the United States in 1994 and 1995: results of a 30-center national surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2884–2886. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle W J. Animal models of otitis media: other pathogens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;81(Suppl.):S45–S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dungworth D L. The respiratory system. In: Jubb K V F, Kennedy P C, Palmer N, editors. Pathology of domestic animals. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 413–556. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durum S K, Oppenheim J J. Proinflammatory cytokines and immunity. In: Paul W E, editor. Fundamental immunology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 801–836. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enright M C, McKenzie H. Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis clinical and molecular aspects of a rediscovered pathogen. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:360–371. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-5-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faden H, Harabuchi Y, Hong J J. Epidemiology of Moraxella catarrhalis in children during the first 2 years of life: relationship to otitis media. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1312–1317. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faden H, Hong J J, Pahade N. Immune response to Moraxella catarrhalis in children with otitis media: opsonophagocytosis with antigen-coated latex beads. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:522–524. doi: 10.1177/000348949410300704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fattom A, Cho Y H, Chu C, Fuller S, Fries L, Naso R. Epitopic overload at the site of injection may result in suppression of the immune response to combined capsular polysaccharide conjugate vaccines. Vaccine. 1999;17:126–133. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleit H B, Lane B P. FC gamma receptor mediated phagocytosis by human neutrophil cytoplasts. Inflammation. 1999;23:253–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1020226020062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fomsgaard J S, Fomsgaard A, Hoiby N, Bruun B, Galanos C. Comparative immunochemistry of lipopolysaccharides from Branhamella catarrhalis strains. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3346–3349. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3346-3349.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foxwell A R, Kyd J M, Cripps A W. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:294–308. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.294-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank M M, Joiner K, Hammer C. The function of antibody and complement in the lysis of bacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9(Suppl. 5):S537–S545. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_5.s537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung C P, Yeo S F, Livermore D M. Susceptibility of Moraxella catarrhalis isolates to beta-lactam antibiotics in relation to beta-lactamase pattern. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:215–222. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottfarb P, Brauner A. Children with persistent cough outcome with treatment and role of Moraxella catarrhalis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:545–551. doi: 10.3109/00365549409011812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu X-X, Chen J, Barenkamp S J, Robbins J B, Tsai C M, Lim D J, Battey J. Synthesis and characterization of lipooligosaccharide-based conjugates as vaccine candidates for Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1891–1897. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1891-1897.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu X-X, Tsai C M, Ueyama T, Barenkamp S J, Robbins J B, Lim D J. Synthesis, characterization, and immunologic properties of detoxified lipooligosaccharide from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae conjugated to proteins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4047–4053. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4047-4053.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helminen M E, Maciver I, Latimer J L, Cope L D, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. A major outer membrane protein of Moraxella catarrhalis is a target for antibodies that enhance pulmonary clearance of the pathogen in an animal model. Infect Immun. 1996;61:2003–2010. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2003-2010.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W-G, Chen J, Collins F M, Gu X-X. An aerosol challenge mouse model for Moraxella catarrhalis. Vaccine. 1999;18:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ioannidis J P A, Worthington M, Griffiths J K, Snydman D R. Spectrum and significance of bacteremia due to Moraxella catarrhalis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:390–397. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liszewski M K, Atkinson J P. The complement system. In: Paul W E, editor. Fundamental immunology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 917–940. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer G A, Shope T R, Waecker N J, Jr, Lanningham F H. Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis bacteremia in children. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr. 1995;34:146–150. doi: 10.1177/000992289503400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy T F. Branhamella catarrhalis: epidemiology, surface antigenic structure, and immune response. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:267–279. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.267-279.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy T F, Kyd J M, John A, Kirkham C, Cripps A W. Enhancement of pulmonary clearance of Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis following immunization with outer membrane protein CD in a mouse model. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1667–1675. doi: 10.1086/314501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers L E, Yang Y P, Du R P, Wang Q, Harkness R E, Schryvers A B, Klein M H, Loosmore S M. The transferrin binding protein B of Moraxella catarrhalis elicits bactericidal antibodies and is a potential vaccine antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4183–4192. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4183-4192.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman M, Holme T, Jonsson I, Krook A. Lack of serotype-specific antibody response to lipopolysaccharide antigens of Moraxella catarrhalis during lower respiratory tract infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:297–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02116522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds H Y. Pulmonary host defenses in rabbits after immunization with Pseudomonas antigens: the interaction of bacteria, antibodies, macrophages, and lymphocytes. J Infect Dis. 1974;130(Suppl.):S134–S142. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.supplement.s134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds H Y. Phagocytic defense in the lung. Antibiot Chemother. 1985;36:74–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schutze M P, Leclerc C, Jolivet M, Audibert F, Chedid L. Carrier-induced epitopic suppression, a major issue for future synthetic vaccines. J Immunol. 1985;135:2319–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka H, Oishi K, Sonoda F, Iwagaki A, Nagatake T, Matsumoto K. Biochemical analysis of lipopolysaccharides from respiratory pathogenic Branhamella catarrhalis strains and the role of anti-LPS antibodies in Branhamella respiratory infections. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis. 1992;66:709–715. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.66.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teele D, Klein J, Rosner B the Greater Boston Otitis Media Study Group. Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:83–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toews G B, Gross G N, Pierce A K. The relationship of inoculum size to lung bacterial clearance and phagocytic cell response in mice. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:559–566. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unhanand M, Maciver I, Ramilo O, Arencibia-Mireles O, Argyle J C, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. Pulmonary clearance of Moraxella catarrhalis in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:644–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaneechoutte M, Verschraegen G, Claeys G, Van Den Abeele A M. Serological typing of Branhamella catarrhalis strains on the basis of lipopolysaccharide antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:182–187. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.182-187.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zwirner J, Werfel T, Wilken H C, Theile E, Götze O. Anaphylatoxin C3a but not C3a (desArg) is a chemotaxin for the mouse macrophage cell line J774. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1570–1577. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1570::AID-IMMU1570>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]