Abstract

Background

Loneliness and social isolation usually increase the risk of mental disorders. However, this association among Chinese medical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear.

Methods

This study was conducted in September 2022; 1,338 medical residents from three hospitals in Northeastern China were included in the final analysis. The data were collected via online self-administered questionnaires. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were determined for adjusting for potential confounders by binary logistic regression.

Results

Among the 1,338 participants, 12.93% (173), 9.94% (133), and 9.72% (130) had experienced major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation, respectively. Further, 24.40% (327) and 44.50% (596) of the total participants had experienced loneliness and social isolation. Loneliness increased the risk of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation (all p<0.001); Compared with the lowest quartile, the odds ratios of the highest quartile were 4.81, 4.63, and 5.34. The same result was obtained in relation to social isolation (all p<0.001).

Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed a considerable prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, and mental disorders among Chinese medical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both loneliness and social isolation increased the risk of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Loneliness, social isolation, mental disorders, medical residents, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Anxiety and depression are common mental disorders (Liu et al., 2020; Stein and Sareen, 2015). Anxiety is characterized by chronic and persistent feelings of uncertainty, dread, and fearfulness, while persistent anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure) is characteristic of major depression (Association, A. P., 2013). Both are global health threats, increasing the risk of mental and physical impairment and drug consumption, leading to suicidal ideation and even excess mortality (Cuijpers et al., 2013; Lasserre et al., 2016; Sareen et al., 2006; Robinson et al., 2011). According to the World Health Organization 2016, depression accounts for 10% of the total non-fatal disease burden and is the leading cause of disability worldwide (GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2018). In America, about 10% of the general population experiences depression in their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2003), and the current global incidence of anxiety disorders is 7.3% (Baxter et al., 2013). Since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, in addition to physical health, the mental health impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic is also serious. The cases of major depressive disorders and the cases of anxiety disorders globally during the COVID-19 pandemic increased 27.6% and 25.6%, respectively (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators). The rate of suicidal ideations during the COVID-19 pandemic is also higher than prior to the pandemic (Farooq et al., 2021). Previous studies have reported that healthcare professionals are at a higher risk of mental illness, including depression and anxiety, than the general population (Harvey et al., 2021; Mata et al., 2015). Among Chinese physicians, the incidence of depression has been reported as high as 48.28–57.2% (Chang et al., 2021; Fang et al., 2018). A high prevalence of depression (65.8%) and anxiety symptoms (58.3%) during the COVID-19 pandemic was also found among medical residents trained in KSA (Alawad, H. S. et al., 2022). A high prevalence of depression (65.8%) and anxiety symptoms (58.3%) during the COVID-19 pandemic was also found among medical residents trained in KSA (Alawad, H. S. et al., 2022). Poor mental health results in significant psychosocial impairment and even excess mortality among affected physicians (Lasserre et al., 2016) and leads to low-quality patient care and medical errors (Fahrenkopf et al., 2008; West et al., 2006; Shanafelt et al., 2005).

Loneliness is a subjective experience of perceiving a discrepancy between one's own actual and desired levels of social relating (Peplau and Perlman, 1982). It is now being highlighted as a public health problem (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2018; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017), with millions of people suffering daily (Steffick, 2000). Social isolation is reflected by situational factors such as a small network structure (e.g., infrequent interaction) or lack of participation in social activities and groups (Santini et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, multifaceted public health interventions have been taken, such as social distancing, and home quarantine which may therefore increase the incidence of loneliness (Pai and Vella, 2021; Bu et al.,2020). Physicians are not immune to loneliness and social isolation. A study in the Harvard Business Review found that workers with professional degrees, such as in medicine, have the highest rates of loneliness among all professional workers (Achor et al., 2018). In addition, previous research on samples of physicians also illustrated that loneliness was prevalent in almost half of the respondents (Ofei-Dodoo et al., 2021, 2020).

Given the strong overlap between the component of depression and loneliness items, loneliness strongly correlates with symptoms of depression and anxiety (Cacioppo, 2015). Another plausible reason used to explain the effect of loneliness on depression is feeling a sense of belonging alone (Erzen E, 2018), which may indirectly trigger depression. For instance, people who distance from daily life, are more likely to experience depression. Previous studies also found that loneliness and social isolation are detrimental to mental health, contributing to diseases such as depression and anxiety in middle-aged and older adults (Santini et al., 2020; Beutel et al., 2017; Stickley and Koyanagi, 2016; Cacioppo et al., 2010; Steptoe et al., 2004). However, there is no research concerning loneliness and its association with mental disorders among medical residents, who are commonly young adults susceptible to loneliness (Matthews et al., 2019; Yang and Victor, 2011). In 2014, the State Health and Family Planning Commission in China launched a standardized residency training program to guarantee the quality of medical care as a national strategy. China imposed a “five plus three” model to become a qualified physician (five-year medical education program in university plus three-year standardized training in hospitals for residents). This initially established standardized residency training program faces many challenges and needs improvements.

China has the largest population worldwide and a lower ratio of doctors to patients than western countries (Fu et al., 2018). Furthermore, Chinese medical residents usually suffer due to overwork, poor doctor-patient relationships, workplace violence, low incomes, and high academic stress (Shan et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2014; Ma, 2014), which may easily induce psychological disorders. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to the mental health of Chinese medical residents. We aimed to explore the relationship between loneliness and mental disorders among medical residents in China based on a large multi-center cross-sectional study by adjusting extensive confounding factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This multi-center cross-sectional study was conducted in September 2022 by the department of postgraduate administration without sampling method; 1,533 medical residents from three hospitals in Liaoning province were enrolled in the present study. A set of online anonymous self-administered questionnaires was adopted. The average questionnaire took 15 to 20 min. Reminders were sent every 48–72 hours through WeChat to increase a high feedback rate.

Ethical approval (2022PS993K) was provided by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of the Shengjing Hospital Affiliated China Medical University. All centers were in accordance with this ethical standards. Informed consent from all eligible subjects were obtained. The clinical research registry UIN is ChiCTR1900027707. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

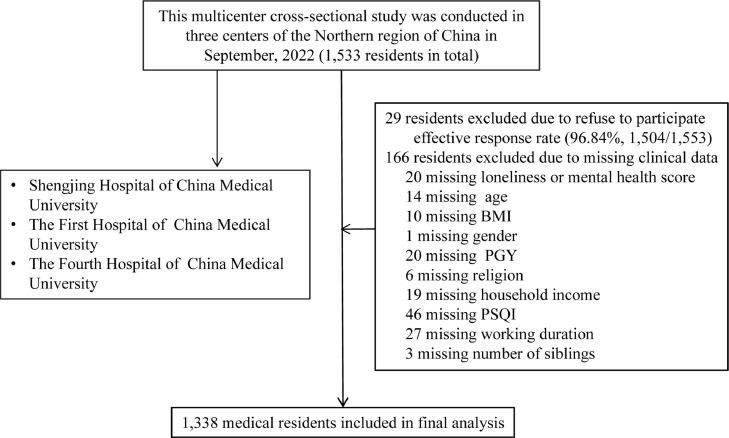

The inclusion criteria were as follows: occupationally active medical residents employed in hospitals. The following exclusion criteria were used: medical residents who had participated in work for less than three months and did not provide a complete psychological questionnaire were excluded. Finally, effective responses were obtained from 1,338 individuals (effective response rate: 87.28%). A flow chart illustrating the process is detailed in Fig. 1

Figure 1.

Flowchart of this study Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; PGY, Post graduation year.

2.3. Measurement of characteristics

In this study, demographic characteristics included age, gender, and BMI (kg/m2). Dietary habits included smoking status (current vs. never vs. former), alcohol habit (current vs. never vs. former), coffee habit (current vs. never vs. former); Life-related factors included sleep quality (PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index scores), physical activity (IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire, Mets × hour/week), have religions (yes vs. no), marital status (single/divorced/separation/widow vs. married/cohabitation), have siblings (yes vs. no), household income monthly (RMB, yuan) was categorized as,< 5,000, ≧5,000, < 10,000 and ≧10,000, experienced major life events (yes vs. no), history of chronic disease (yes vs. no), visiting friend constantly (yes vs. no).

Work-related factors include post-graduation year (1st year vs. 2nd year vs. 3rd year), specialty (surgery vs. internal medicine and others vs obstetrics and gynecology vs. pediatrics), working duration (≤ 40 hours/week vs. 40-60 hours/week vs. ≥ 60 hours/week), and night shifts (times/month). Smoking habit was categorized as a current smoker (≧ 1 cigarette per day and last ≧ 6 months), former smoker (stop smoking ≧ 6 months), and never smoker. Alcohol habits and coffee habits as categorized as a current drinker (≧ 1 time per day and last ≧ 6 months), former drinker (stop drinking ≧ 6 months), and never a drinker.

Physical activity (PA) in the most recent week was assessed using the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Craig et al., 2003). The questionnaire asked whether subjects had performed any activities from the following categories during the previous week: walking; moderate activity (household activity or child care); vigorous activity (running, swimming, or other sports activities). Metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per week were calculated using corresponding MET coefficients (3.3, 4.0, and 8.0, respectively) according to the following formula: MET coefficient of activity × duration (h) × frequency (days). Total PA levels were assessed by combining separate scores for different activities.

Sleep quality was measured by the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) developed by Buysse et al. (Buysse et al., 1989). It is a self-report on subjective sleep quality over the last 4 weeks with 18 questions. The first four questions enquire about times (bed time, number of minutes it took for the participant to fall asleep, get up time, and hours of sleep per night). The next 10 questions ask how often the participant had trouble sleeping because of different reasons (e.g. woke up in the middle of the night, need to go to the bathroom, cough, and bad dreams). Each of these questions must be answered on a 4-point scale ranging from “never” to “three times or more a week.” Additional questions include a subjective rating of theparticipants’ sleep quality (4-point scale from “very good” to “very bad”), the use of sleep medication, and trouble staying awake during the day (4-point scale ranging from “never” to “three times or more a week”). The final question asks if it has been a problem for the participant to keep up enough enthusiasm for getting things done (4-point scale ranging from “no problem at all” to “a very big problem”). The 18 items of the PSQI form seven-component score ranging from 0 to 3 (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction) that can be summed up to a general score. Higher scores represent worse sleep quality. Poor sleep quality is indicated by total score of 6 or greater.

Experienced major life events included separation/divorce, death or severe illness of close family members, serious injury/traffic accident, violence, unemployment, natural disasters, death or severe illness of partner, serious conflict with family, medical disputes, or income decrease/debt. History of physical illness was evaluated based on response (“Yes” or “No”) to questions concerning a history of diseases (including systemic lupus erythematosus, nasosinusitis, rhinitis, gallbladder stone, polycystic ovary syndrome, Guillain Barre syndrome, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic glomerulonephritis, chronic gastritis, facial neuritis, synovitis of joint, arrhythmia. and pulmonary tuberculosis) and physician-diagnosed diseases (including diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome).

2.4. Measurement of organization support

The Chinese version of the Perceived Organization Support Questionnaire (POS) was utilized to measure the level of organization support (Eisenberger, 2011). The POS has good reliability and validity among various Chinese (Bai, S et al., 2022). There were nine items, The score of each item is given on a 7-point Likert-type scale in accordance with the residents' personal experiences, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The total score ranges from 9 to 63, with a higher score indicating higher social support. In the present study, the Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.802.

2.5. Measurement of anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were measured with the Chinese version of the GAD07. The GAD07 consists of 7 items, and each item is answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale responses ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). A higher score means more severe anxiety symptoms. The presence of major anxiety was defined as a GAD07 standardized score ≧ 10 ( Spitzer et al., 2006 ). The Chinese GAD07 version has been extensively applied and validated among Chinese patients (Bai, S et al., 2021). In this study, the Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.913.

2.6. Measurement of depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured by clinically validated scales for PHQ09. The presence of major depression was defined as a PHQ09 score ≧ 10. Suicidal ideation was defined as the ninth-question score of PH09 (thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way) ≧1. The Chinese PHQ09 scale has been widely used in previous studies (Kroenke et al., 2001). The Cronbach's α coefficient for this study was 0.917 in the present study.

2.7. Measurement of loneliness

We measured loneliness with the three-item short form of the Revised UCLA loneliness scale (Hughes et al., 2004). The cutoff point for loneliness was ≥6, in line with previous studies (Domènech-Abella et al., 2017). Social isolation was defined as the third question score of the Three-Item Loneliness Scale (How often do you feel isolated from others?) ≧2. The Cronbach's α coefficient for this study was 0.937.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as the median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were reported as the number (percentage). To compare the means of two continuous normally distributed variables, the independent-samples Student's t-test was utilized. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two continuous non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variable was provided as number (percentage). The chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were employed to compare categorical variables.

Quartiles were categorized across the scores of loneliness (≤ 3, 4, 5, and ≥ 6) based on the distribution for all participants and used for further analysis. Relationships between loneliness scores and mental disorders (major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation) were examined using binary unconditional logistic regression analysis. Mental disorders were used as dependent variables, and loneliness scores were used as independent variables. Similarly, relationships between social isolation and mental disorders (major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation) were also examined using binary unconditional logistic regression analysis. Mental disorders were used as dependent variables, and social isolation was used as the independent variable. Model 1 was used to calculate the crude OR, and Model 2 additionally adjusted for age, gender, and BMI. Model 3 additionally adjusted for baseline variables considered clinically relevant or had a p-value < 0.10 in the univariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were determined after adjusting for potential confounders by binary unconditional logistic regression. A linear trend across increasing quartiles was tested using the median value of each quartile as a continuous variable. All P values were two-tailed, and the difference was significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

Among the 1,338 participants enrolled in the final analyses, the median age was 26.00 years, and the BMI was 21.48 kg/m2; most participants were female (68.20%, 912/1338). There were 12.93% (173/1,338) medical residents experienced major depression, 9.72% (130/1,338) experienced suicidal ideation, and 9.94% (133/1,338) experienced major anxiety. The participants who experienced loneliness and social isolation were 24.40% (327/1,338) and 44.5% (596/1,338); see details in Table 1 . and 2 .

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of the risk factors for major depression and major anxiety of Chinese medical residents.

| Variables | Total | Major depression | No major depression | P | Major anxiety | No major anxiety | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | 1,338 (100) | 173 (12.93) | 1,165 (87.07) | 133 (9.94) | 1,205 (90.06) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 26.00 (24.00, 27.00) | 25.00 (25.00, 27.00) | 26.00 (24.00, 27.00) | 0.857 | 25.00 (24.00, 27.00) | 26.00 (24.00, 27.00) | 0.053 |

| Gender (male vs.female) | 426 (31.80)/912 (68.20) | 53 (30.60)/120 (69.40) | 373 (32.00)/792 (68.00) | 0.716 | 40 (30.10)/93 (69.90) | 386 (32.00)/819 (68.00) | 0.646 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.48 (19.71, 23.89) | 22.34 (19.98, 24.22) | 21.48 (19.68, 23.88) | 0.037 | 22.19 (19.98, 23.84) | 21.48 (19.65, 23.89) | 0.607 |

| Dietary habits | |||||||

| Smoking habit | 0.849 | 0.273 | |||||

| Current | 52 (3.90) | 7 (4.00) | 45 (3.90) | 5 (3.80) | 47 (3.90) | ||

| Never | 1,254 (93.70) | 161 (93.10) | 1,093 (93.80) | 122 (91.70) | 1,132 (93.90) | ||

| Former | 32 (2.40) | 5 (2.90) | 27 (2.30) | 6 (4.50) | 26 (2.20) | ||

| Alcohol habit | 0.328 | 0.874 | |||||

| Current | 678 (50.70) | 96 (55.50) | 582 (50.00) | 69 (51.90) | 609 (50.50) | ||

| Never | 645 (48.20) | 73 (42.20) | 572 (49.10) | 60 (45.10) | 585 (48.50) | ||

| Former | 15 (1.10) | 4 (2.30) | 11 (0.90) | 4 (3.00) | 11 (0.90) | ||

| Coffee habit | 0.457 | 0.900 | |||||

| Current | 987 (73.80) | 132 (76.30) | 855 (73.40) | 98 (73.70) | 889 (73.80) | ||

| Never | 292(21.80) | 34 (19.70) | 258 (22.10) | 30 (22.60) | 262 (21.70) | ||

| Former | 59 (4.40) | 7 (4.00) | 52 (4.50) | 5 (3.80) | 54 (4.50) | ||

| Life related factors | |||||||

| Sleep quality (PSQI scores) | 5.00 (3.00, 7.00) | 7.00 (6.00, 10.00) | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | < 0.001 | 8.00 (6.00, 10.00) | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity (IPAQ Mets × hour/week) | 16.00 (9.90, 33.55) | 13.20(9.70, 26.33) | 16.00 (10.10, 33.63) | 0.586 | 13.70 (9.70, 32.20) | 16.00 (9.95, 33.55) | 0.159 |

| Have religions (yes) | 51 (3.80) | 12 (6.90) | 39 (3.30) | 0.024 | 13 (9.80) | 38 (3.20) | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | 0.512 | 0.422 | |||||

| Single/divorce/separation/widow | 1,146 (85.70) | 151 (87.30) | 995 (85.40) | 117 (88.00) | 1,029 (85.40) | ||

| Married/cohabitation | 192 (14.30) | 22 (12.70) | 170 (14.60) | 16 (12.00) | 176 (14.60) | ||

| Have siblings (yes) | 99 (7.40) | 10 (5.80) | 89 (7.60) | 0.385 | 7 (5.30) | 92 (7.60) | 0.324 |

| Household income (Yuan/month) | 0.159 | 0.468 | |||||

| < 5,000 | 118 (8.80) | 19 (11.00) | 99 (8.50) | 14 (10.50) | 104 (8.60) | ||

| ≧5,000, <10,000 | 266 (19.90) | 38 (22.00) | 228 (19.60) | 27 (20.30) | 239 (19.80) | ||

| ≧10,000 | 954 (71.30) | 116 (67.10) | 838 (71.90) | 92 (69.20) | 862 (71.50) | ||

| Experienced major events (yes) | 397 (29.70) | 74 (42.80) | 323 (27.70) | < 0.001 | 56 (42.10) | 341 (28.30) | 0.001 |

| History of chronic disease (yes) | 129 (9.60) | 30 (17.30) | 99 (8.50) | < 0.001 | 26 (19.50) | 103 (8.50) | < 0.001 |

| Work related factors | |||||||

| Post graduation year | 0.762 | 0.557 | |||||

| PGY1 | 402 (30.00) | 48 (27.70) | 354 (30.40) | 42 (31.60) | 360 (29.90) | ||

| PGY2 | 472 (35.30) | 66 (38.20) | 406 (34.80) | 48 (36.10) | 424 (35.20) | ||

| PGY3 | 464 (34.70) | 59 (34.10) | 405 (34.80) | 43 (32.30) | 421 (34.90) | ||

| Speciality | 0.231 | 0.949 | |||||

| Surgery | 263 (19.70) | 35 (20.20) | 228 (19.60) | 26 (19.50) | 237 (19.70) | ||

| Internal medicine and others | 911 (68.10) | 111 (64.20) | 800 (68.70) | 91 (68.40) | 820 (68.00) | ||

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 90 (6.70) | 12 (6.90) | 78 (6.70) | 8 (6.00) | 82 (6.80) | ||

| Pediatrics | 74 (5.50) | 15 (8.70) | 59 (5.10) | 8 (6.00) | 66 (5.50) | ||

| Working duration (hours/week) | 0.001 | 0.132 | |||||

| ≤ 40 hours | 353 (26.40) | 35 (20.20) | 318 (27.30) | 25 (18.80) | 328 (27.20) | ||

| 41-60 hours | 583 (43.60) | 64 (37.00) | 519 (44.50) | 56 (42.10) | 527 (43.70) | ||

| ≥ 61 hours | 402 (30.00) | 74 (42.80) | 328 (28.20) | 52 (39.10) | 350 (29.00) | ||

| Night shifts (times/month) | 4.00 (0.00, 7.00) | 4.00 (0.00. 8.00) | 4.00 (0.00. 6.00) | 0.002 | 4.00 (0.00. 8.00) | 4.00 (0.00. 6.00) | 0.011 |

| Psychological characteristics | |||||||

| POS (scores) | 43.00 (37.00, 49.00) | 38.00 (31.00, 43.00) | 43.00 (38.00, 49.00) | < 0.001 | 39.00 (32.00, 44.50) | 43.00 (37.00, 49.00) | < 0.001 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 327 (24.40) | 102 (59.00) | 225 (19.30) | < 0.001 | 78 (58.60) | 249 (20.70) | < 0.001 |

| Social isolation (yes) | 596 (44.50) | 129 (74.60) | 467 (40.10) | < 0.001 | 103 (77.40) | 493 (40.90) | < 0.001 |

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range); categorical variables were reported as number (percentage). To compare the means of two continuous normally distributed variables, the independent-samples Student's t-test was utilized. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two continuous non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variable was provided as number (percentage). The chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were employed to compare categorical variables.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; PGY, Post graduation year; POS, Perceived Organization Support.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the risk factors for suicidal ideation of Chinese medical residents.

| Variables | Suicidal ideation | No suicidal ideation | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | 130 (9.72) | 1,208 (90.28) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 25.00 (25.00, 27.00) | 26.00 (24.00, 27.00) | 0.602 |

| Gender (male vs.female) | 46 (35.40)/84 (64.60) | 380 (31.50)/828 (68.50) | 0.362 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.19 (19.80, 24.22) | 21.48 (19.71, 23.88) | 0.340 |

| Dietary habits | |||

| Smoking habit | 0.983 | ||

| Current | 5 (3.80) | 47 (3.90) | |

| Never | 122 (93.80) | 1,132 (93.70) | |

| Former | 3 (2.30) | 29 (2.40) | |

| Alcohol habit | 0.041 | ||

| Current | 79 (60.80) | 599 (49.60) | |

| Never | 48 (36.90) | 597 (49.40) | |

| Former | 3 (2.30) | 12 (1.00) | |

| Coffee habit | 0.757 | ||

| Current | 94 (72.30) | 893 (73.90) | |

| Never | 34 (26.20) | 258 (21.40) | |

| Former | 2 (1.50) | 57 (4.70) | |

| Life related factors | |||

| Sleep quality (PSQI scores) | 7.00 (5.00, 8.25) | 5.00 (3.00, 7.00) | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity (IPAQ Mets × hour/week) | 17.55 (6.24, 35.79) | 15.95 (10.28, 33.00) | 0.631 |

| Have religions (yes) | 9 (6.90) | 42 (3.50) | 0.056 |

| Marital status | 0.723 | ||

| Single/divorce/separation/widow | 110 (84.60) | 1,036 (85.80) | |

| Married/cohabitation | 20 (15.40) | 173 (14.20) | |

| Have siblings (yes) | 8 (6.20) | 91 (7.50) | 0.569 |

| Household income (Yuan/month) | 0.058 | ||

| < 5,000 | 17 (13.10) | 101 (8.40) | |

| ≧5,000, <10,000 | 28 (21.50) | 238 (19.70) | |

| ≧10,000 | 85 (65.40) | 869 (71.90) | |

| Experienced major events (yes) | 47 (36.20) | 350 (29.00) | 0.090 |

| History of chronic disease (yes) | 15 (11.50) | 114 (9.40) | 0.441 |

| Work related factors | |||

| Post graduation year | 0.208 | ||

| PGY1 | 31 (23.80) | 371 (30.70) | |

| PGY2 | 51 (39.20) | 421 (34.90) | |

| PGY3 | 48 (36.90) | 416 (34.40) | |

| Speciality | 0.835 | ||

| Surgery | 29 (22.30) | 234 (19.40) | |

| Internal medicine and others | 84 (64.60) | 827 (68.50) | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 9 (6.90) | 81 (6.70) | |

| Pediatrics | 8 (6.20) | 66 (5.50) | |

| Working duration (hours/week) | 0.044 | ||

| ≤ 40 hours | 29 (22.30) | 324 (26.80) | |

| 41-60 hours | 50 (38.50) | 533 (44.10) | |

| ≥ 61 hours | 51 (39.20) | 351 (29.10) | |

| Night shifts (times/month) | 4.00 (0.00. 8.00) | 4.00 (0.00. 6.00) | 0.017 |

| Psychological characteristics | |||

| POS (scores) | 41.00 (35.00, 48.25) | 43.00 (37.00, 49.00) | 0.209 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 78 (60.00) | 249 (20.60) | < 0.001 |

| Social isolation (yes) | 91 (70.00) | 505 (41.80) | < 0.001 |

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range); categorical variables were reported as number (percentage). To compare the means of two continuous normally distributed variables, the independent-samples Student's t-test was utilized. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two continuous non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variable was provided as number (percentage). The chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were employed to compare categorical variables.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; PGY, Post graduation year; POS, Perceived Organization Support;

The medical residents with major depression tended to have higher BMI and POS scores, longer working duration and more frequent night shifts, and poor sleep quality. They had a high prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, religious belief, experience of major events, history of chronic disease, and visiting friends rarely. The medical residents with major anxiety tended to be younger, have a longer working duration and more frequent night shifts, poor sleep quality, higher scores of POS, and had a high prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, religious belief, experience of major events, history of chronic disease and visiting friends rarely. Participants with suicidal ideation tended to intake more alcohol, have a longer working duration and more frequent night shifts, have poor sleep quality, have less household income, and had a high prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, religious belief, and experience of major events. As shown in Table 1.and 2. All the characteristics mentioned above were statistically different in univariate analysis and then were included in multivariate analysis.

Quartiles were categorized across the scores of the loneliness scale (≤ 3, 4, 5, and ≥ 6) based on the distribution for all participants and used for multiple logistic regression analysis. After multiple adjustments, we found that loneliness (p for trend < 0.001) was associated with a higher risk of mental disorders (major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation). The ORs and 95 % CI for the extreme quartile were 4.81 (3.03–7.65), 4.63 (2.72–7.87), and 5.34 (3.31–8.61). As shown in Table 3 . Moreover, this trend was also detected in social isolation (p for trend < 0.001), the ORs and 95 % CI of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation were 2.95 (1.99–4.36), 3.08 (1.96–4.82) and 2.58 (1.72–3.86), respectively. As shown in Table 4 .

Table 3.

Association between loneliness scores level and mental disorders in the cohort analysis (n = 1,338)

| Quartiles of loneliness scores level (range, n = 1,338) | P for trend a | per 1 score | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness scores level | Level 1 (≤3) | Level 2 (4) | Level 3 (5) | Level 4 (≥6) | |||

| No. of participants | 628 | 221 | 162 | 327 | 1,338 | ||

| No. of major depression | 31 | 17 | 23 | 102 | 173 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 1.61 (0.87, 2.96) | 3.19 (1.80, 5.64) | 8.73 (5.68, 13.42) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.66, 2.06) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 1.58 (0.85, 2.91) | 3.16 (1.78, 5.59) | 8.73 (5.67, 13.44) | < 0.001 | 1.87 (1.68, 2.09) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 d | Reference | 1.26 (0.66, 2.40) | 1.94 (1.06, 3.55) | 4.81 (3.03, 7.65) | < 0.001 | 1.60 (1.41, 1.81) | < 0.001 |

| No. of suicidal ideation | 27 | 10 | 15 | 78 | 130 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 1.06 (0.50, 2.22) | 2.27 (1.18, 4.38) | 6.97 (4.39, 11.07) | < 0.001 | 1.73 (1.54, 1.93) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 1.07 (0.51, 2.25) | 2.28 (1.18, 4.40) | 6.97 (4.39,11.07) | < 0.001 | 1.73 (1.55, 1.94) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 e | Reference | 0.94 (0.45, 1.99) | 1.83 (0.94, 3.57) | 5.34 (3.31, 8.61) | < 0.001 | 1.60 (1.42, 1.80) | < 0.001 |

| No. of major anxiety | 22 | 19 | 14 | 78 | 133 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 2.59 (1.37, 4.89) | 2.61 (1.30, 5.21) | 8.63 (5.26, 14.16) | < 0.001 | 1.84 (1.64, 2.06) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 2.51 (1.33, 4.75) | 2.57 (1.28, 5.14) | 8.61 (5.24, 14.14) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.65, 2.08) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 f | Reference | 1.95 (1.01, 3.77) | 1.53 (0.74, 3.17) | 4.63 (2.72, 7.87) | < 0.001 | 1.60 (1.41, 1.82) | < 0.001 |

Multiple Logistic regression analysis.

b Odd ratio (95% confidence interval).

Adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index.

Additionally adjusted for sleep quality, having religions, experienced major events, history of chronic disease, working duration, night shifts and POS based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 284.406, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 7.179, P = 0.517.

Additionally adjusted for alcohol habit, sleep quality, having religions, household income, experienced major events, working duration and night shifts based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 114.555, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 6.733, P = 0.566.

Additionally adjusted for sleep quality, having religions, experienced major events, history of chronic disease, night shifts and POS based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 198.796, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 13.102, P = 0.108.

Table 4.

Association between social isolation and mental disorders in the cohort analysis (n =1,338).

| No social isolation | Social isolation | P for trend a | per 1 score | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 742 | 596 | 1,338 | ||

| No. of major depression | 44 | 129 | 173 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 4.38 (3.05, 6.29) | < 0.001 | 4.26 (3.24, 5.60) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 4.36 (3.03, 6.26) | < 0.001 | 4.27 (3.24, 5.62) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 g | Reference | 2.95 (1.99, 4.36) | < 0.001 | 2.71 (1.99, 3.69) | < 0.001 |

| No. of suicidal ideation | 39 | 91 | 130 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 3.25 (2.19, 4.81) | < 0.001 | 2.49 (1.46, 3.36) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 3.26 (2.20, 4.82) | < 0.001 | 2.40 (1.46, 3.38) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 h | Reference | 2.58 (1.72, 3.86) | < 0.001 | 1.88 (1.32, 2.35) | < 0.001 |

| No. of major anxiety | 30 | 103 | 133 | ||

| Crude model | Reference | 4.96 (3.25, 7.57) | < 0.001 | 3.69 (2.76, 4.95) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 1 c | Reference | 4.90 (3.21, 7.48) | < 0.001 | 3.67 (2.74, 4.93) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted model 2 i | Reference | 3.08 (1.96, 4.82) | < 0.001 | 2.34 (1.69, 3.24) | < 0.001 |

Multiple Logistic regression analysis.

b Odd ratio (95% confidence interval)

Adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index.

Additionally adjusted for sleep quality, having religions, experienced major events, history of chronic disease, working duration, night shifts and POS based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 265.092, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 3.487, P = 0.900.

Additionally adjusted for alcohol habit, sleep quality, having religions, household income, experienced major events, working duration and night shifts based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 127.214, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 6.010, P = 0.646.

Additionally adjusted for age, sleep quality, having religions, experienced major events, history of chronic disease, night shifts and POS based on Model 1; Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients statistic = 181.553, P < 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow Test statistic = 6.616, P = 0.579.

4. Discussion

The association between loneliness and mental disorders among middle-aged and older adults has been extensively explored (Santini et al., 2020; Beutel et al., 2017; Stickley and Koyanagi, 2016; Cacioppo et al., 2010; Steptoe et al., 2004). However, fewer studies have examined this association in young adults, who have also been identified as a high-risk group for loneliness (Matthews et al., 2019; Yang and Victor, 2011), because youngsters' transition to adulthood is the time when they undertake identity explorations, a search for independence and physical separation from family, and enter the workforce (Arnett, 2014). Worse still, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in Chinese government implementing disease containment measures which curtail their social contacts with their friends, families, and community networks. Some studies have found an increase in loneliness in the general adult population during COVID-19 (Pai and Vella, 2021; Bu et al.,2020), specially among young people (Li and Wang, 2020). This is the first multi-center study to explore the association of loneliness and social isolation with mental disorders among Chinese medical residents based on a large population in the COVID-19 context and it revealed a considerable prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, and poor mental health. Both loneliness and social isolation increased the risk of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

We found that the prevalence of major depression among Chinese medical residents was 12.9%. A previous meta-analysis of 54 observational studies (including 17,560 individuals and excluding mainland China) estimated that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 28.8% (ranging from 20.9% to 43.2%) among medical residents (Mata et al., 2015). The discrepancy in the prevalence may be attributed to variations in the cutoff values of the questionnaire and assessment instruments used. We also found that the prevalence of suicidal ideation among Chinese medical residents was 9.72%, which is its first time being reported; this was slightly higher than that among the general population, which has been reported at 9.2% based on cross-national data on 84,850 adults from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey (Nock et al., 2008). The prevalence of major anxiety in our study was 9.9%, which was slightly higher than that among the general population. A meta-analysis that included 84 observational studies across 44 countries estimated that the current global prevalence of anxiety disorders was around 7.3% (4.8–10.9%) (Baxter et al., 2013).

We also found the prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among Chinese medical residents was 24.40% and 44.50%, respectively, which is the first time they are being reported, and these rates are much higher compared to the general population. A large and representative German adult sample (N= 15,010, aged 35–74 years) demonstrated that 10.5% of participants reported loneliness (Beutel et al., 2017). A study in the Harvard Business Review found that doctors have the highest rates of loneliness among all workers (Achor et al., 2018). Low income (Theeke, 2010), overwork, small social networks, and occupational stress may contribute to this situation (Hawkley et al., 2008).

This study revealed that both loneliness and isolation were positively associated with the incidence of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation. In line with this, a recent cross-sectional study that used self-reported data of 19,890 participants in Denmark suggested that loneliness and social isolation were associated with depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults (Christiansen et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis of 114 identified studies including young adults revealed that loneliness had adverse effects on mental health (i.e., depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation) (Park et al., 2020). Additionally, another study that analyzed 741 college students at Tianjin Medical University found that social isolation and loneliness were associated with depressive symptoms among females; however, in males, isolation rather than loneliness can predict depressive symptoms (Liu et al., 2020). A study that collected data from 564 young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that the aggravation of loneliness accounted for much of the increase in the number of cases of depression, but did not lead to major anxiety (Lee et al., 2020). The differences in participants’ professions and regions may contribute to the discrepant results.

Previous studies have provided evidences of a stable relationship between loneliness and depression across the lifespan (Victor and Yang et al., 2012), with longitudinal studies showing that loneliness is a unique predictor of depressive symptom (Santini et al., 2020) and depression also predicting loneliness over time (Dom`enech-Abella et al., 2017), they could interact as both cause and effect. The relationship between loneliness and anxiety is less well understood. However, as with depression, the link between loneliness and anxiety seems to be also bidirectional (Beutel et al., 2017).

The mechanisms underlying this association are unknown; a previous experimental study in healthy adults showed that loneliness is closely related to increased inflammatory gene expression (Jaremka et al., 2013), affecting the brain and leading to mental disorders (Dantzer et al., 2008). Some experimental studies in animals demonstrated that isolation could induce change in myelination of the prefrontal cortex (Liu et al., 2012), concentrations of neurosteroids (Nin et al., 2011), growth factors (Matsumoto et al., 2012), and activity of cellular transcription factors (Barrot et al., 2005), which may cause anxiety and depressive behavior (Cacioppo et al., 2014).

At present, there have been a number of attempts to mitigate loneliness. Such interventions include increased social recreation, enhanced social support, focused on gaining social skills, and addressed maladaptive social cognition (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy). Among these approaches, interventions designed to address maladaptive social cognition were associated with the largest effect size (Cacioppo, et al., 2015). In addition, there is also increasing evidence for the potential efficacy of integrated interventions that combine social cognitive behavioral therapy with short-term adjunctive pharmacological treatments (Cacioppo, et al., 2015). For medical residents, these interventions should be oriented both toward the individual and the community of social networks. More specific, we should aim to provide psychological assistance promoting changes in their social behaviour and to increase their chances of establishing satisfactory social contacts.

There are some limitations to this study. First, reverse causation could not be excluded because of the cross-sectional study design. Second, loneliness and mental disorders were assessed by online self-administered questionnaires instead of clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, this is the first large multi-center cross-sectional study to explore the association of loneliness and social isolation with mental disorders among Chinese medical residents in the COVID-19 context. A prospective study after long-term follow-up is needed to confirm our findings.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study revealed a considerable prevalence of loneliness, social isolation, and mental disorders among Chinese medical residents. Both loneliness and social isolation increased the risk of major depression, major anxiety, and suicidal ideation. These findings enrich the existing literature on mental health among medical residents and demonstrate a critical need for policy changes or interventions to address loneliness, which could improve the mental health of medical residents.

Uncited References

Beutel et al., 2017, Cacioppo et al., 2015, Liu et al., 2020, Santini et al., 2020

Ethical statement

Ethical approval (Ethical Committee No.2022PS993K) was offered by the Ethics Committee of Shengjing hospital Affiliated China Medical University in Shenyang, China. All informed consent of these patients in this study has been obtained.

Author statements

Song Bai had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Song Bai: Protocol/project development

Yingliang Wei, Jun Tang, Jiajian Liang, Jianzhu Zhao, Zhiyuan Li, and Song Bai: Data collection or management

Yingliang Wei, Jun Tang, Jiajian Liang, Jianzhu Zhao, Zhiyuan Li, and Song Bai: Data analysis

Yingliang Wei, Jun Tang, Jiajian Liang, Jianzhu Zhao, Zhiyuan Li, and Song Bai: Manuscript writing-Original draft preparation

Yingliang Wei, Jun Tang, Jiajian Liang, and Jianzhu Zhao, and Song Bai: Manuscript revision.

Funding

This study was financially supported by The 345 Talent Project of Shengjing Hospital, Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Science and Technology Department (grant number 2020-BS-093), and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Education Department (grant number QN2019013).

Consent for publication

Informed consent from all eligible patients was obtained.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Declaration of Competing Interest

Yingliang Wei, Jun Tang, Jiajian Liang, Jianzhu Zhao, Zhiyuan Li, and Song Bai declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We give special thanks to all the colleagues at Shengjing Hospital for their help and support. We thank International Science Editing (http://www.internationalscienceediting.com) for editing this manuscript. The authors would like to thank all of the study participants.

References

- Achor S., Kellerman GR., Reece A., et al. America's loneliest workers, according to research. Harvard Business Review. 2018 https://hbr.org/2018/03/americas-loneliest-workers-according-to-research accessed July 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alawad H.S., Amin H.S., Alfaris E.A., Ahmed A.M., Alosaimi F.D., BaHammam A.S. Anxiety and depression symptoms among medical residents in KSA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2022;17(2):192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J.J. Oxford University Press; 2014. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A. P., 2013. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th Ed., Arlington, VA.

- Bai S., Chang Q., Yao D., Zhang Y., Wu B., Zhao Y. Anxiety in Residents in China: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Multicenter Study. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2021;96(5):718–727. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S., Chang Q., Yao D., Zhang Y., Wu B., Shan L. The prevalence and risk factors for major depression and suicidal ideation in medical residents based on a large multi-center cross-sectional study using the propensity score-matched method. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2022;57(11):2279–2291. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, Reiner I, Jünger C, Michal M, Wiltink J, Wild PS, Münzel T, Lackner KJ, Tibubos AN. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x. Mar 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F., 3rd, Monk T.H., et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health. 2020;186:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrot M., Wallace D.L., Bolaños C.A., et al. Regulation of anxiety and initiation of sexual behavior by CREB in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8357–8362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500587102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A.J., Scott K.M., Vos T., et al. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2013;43:897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel M.E., Klein E.M., Brähler E., et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:97. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig C.L., Marshall A.L., Sjöström M., et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S., Capitanio J.P., Cacioppo J.T. Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1464–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0037618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. Mar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Vogelzangs N., Twisk J., et al. Differential mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: meta-analysis of studies that measured both. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:22–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Pan Y., Yao Q., et al. Publication pressure on Chinese doctors–another view. Lancet. 2014;384:956. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q., Xia Y., Bai S., et al. Association Between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Resident Physicians. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.564815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen J., Qualter P., Friis K., et al. Associations of loneliness and social isolation with physical and mental health among adolescents and young adults. Perspect Public Health. 2021;141:226–236. doi: 10.1177/17579139211016077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (London, England) 2021;398(10312):1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O'Connor J.C., Freund G.G., et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domènech-Abella J., Lara E., Rubio-Valera M., et al. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: the role of social network. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: Fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;71:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(5):427–435. doi: 10.1177/0020764018776349. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkopf A.M., Sectish T.C., Barger L.K., et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. Bmj. 2008;336:488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Zhao X., Yang H., et al. Depressive symptoms and workplace-violence-related risk factors among otorhinolaryngology nurses and physicians in Northern China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S., Tunmore J., Wajid Ali M., et al. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry research. 2021;306 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Schwebel D.C., Hu G. Physicians' Workloads in China: 1998⁻2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Hawkley L.C., et al. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Res Aging. 2004;26:655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L.C., Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., et al. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:S375–S384. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Robles T.F., Sbarra D.A. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol. 2017;72:517–530. doi: 10.1037/amp0000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S.B., Epstein R.M., Glozier N., et al. Mental illness and suicide among physicians. Lancet. 2021;398:920–930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01596-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaremka L.M., Fagundes C.P., Peng J., et al. Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychol Sci. 2013;24:1089–1097. doi: 10.1177/0956797612464059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Jama. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Dietz K., DeLoyht J.M., et al. Impaired adult myelination in the prefrontal cortex of socially isolated mice. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1621–1623. doi: 10.1038/nn.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasserre A.M., Marti-Soler H., Strippoli M.P., et al. Clinical and course characteristics of depression and all-cause mortality: A prospective population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.M., Cadigan J.M., Rhew I.C. Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association With Increases in Mental Health Problems. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang M., Yang Q., et al. Gender differences in the influence of social isolation and loneliness on depressive symptoms in college students: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., He H., Yang J., et al. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.Z., Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry research. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Ono K., Ouchi H., et al. Social isolation stress down-regulates cortical early growth response 1 (Egr-1) expression in mice. Neurosci Res. 2012;73:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. An Analysis of the Causes of Frequent Cases of Violent Injuries. National Medical Journal of China. 2014;94:1368–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Mata D.A., Ramos M.A., Bansal N., et al. Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms Among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jama. 2015;314:2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews T., Danese A., Caspi A., et al. Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychol Med. 2019;49:268–277. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M.K., Borges G., Bromet E.J., et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin M.S., Martinez L.A., Pibiri F., et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:73. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofei-Dodoo S., Ebberwein C., Kellerman R. Assessing Loneliness and Other Types of Emotional Distress among Practicing Physicians. Kans J Med. 2020;13:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofei-Dodoo S., Mullen R., Pasternak A., et al. Loneliness, Burnout, and Other Types of Emotional Distress Among Family Medicine Physicians: Results From a National Survey. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:531–541. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA., Perlman D. In: Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Pep-lau LA., Perlman D., editors. Wiley; New York: 1982. Perspective on loneliness; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Park C., Majeed A., Gill H., et al. The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai N., Vella S.L. COVID-19 and loneliness: A rapid systematic review. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2021;55(12):1144–1156. doi: 10.1177/00048674211031489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Sareen J., Cox B.J., et al. Role of self-medication in the development of comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders: a longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:800–807. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Madsen KR, Koushede V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffick D.E. University of Michigan, Survey Research Center; Ann Arbor, MI: 2000. Documentation on affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Owen N., Kunz-Ebrecht S.R., et al. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:593–611. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T.D., West C., Zhao X., et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:559–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J., Jacobi F., Cox B.J., et al. Disability and poor quality of life associated with comorbid anxiety disorders and physical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2109–2116. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M.B., Sareen J. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2059–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1502514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickley A., Koyanagi A. Loneliness, common mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from a general population survey. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan H.P., Yang X.H., Zhan X.L., et al. Overwork is a silent killer of Chinese doctors: a review of Karoshi in China 2013-2015. Public Health. 2017;147:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini Z.I., Jose P.E., York Cornwell E., et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theeke L.A. Sociodemographic and health-related risks for loneliness and outcome differences by loneliness status in a sample of U.S. older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3:113–125. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20091103-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J Psychol. 2012;146(1-2):85–104. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.613875. Jan-Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C.P., Huschka M.M., Novotny P.J., et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. Jama. 2006;296:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Victor C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing and Society. 2011;31:1368–1388. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable