Abstract

The underlying mechanisms of plasma metabolite signatures of human aging and age-related diseases are not clear but telomere attrition and dysfunction are central to both. Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is associated with mutations in the telomerase enzyme complex (TERT, TERC, and DKC1) and progressive telomere attrition. We analyzed the effect of telomere attrition on senescence-associated metabolites in fibroblast-conditioned media and DC patient plasma. Samples were analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. We showed extracellular citrate was repressed by canonical telomerase function in vitro and associated with DC leukocyte telomere attrition in vivo, leading to the hypothesis that altered citrate metabolism detects telomere dysfunction. However, elevated citrate and senescence factors only weakly distinguished DC patients from controls, whereas elevated levels of other tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) metabolites, lactate, and especially pyruvate distinguished them with high significance. The DC plasma signature most resembled that of patients with loss of function pyruvate dehydrogenase complex mutations and that of older subjects but significantly not those of type 2 diabetes, lactic acidosis, or elevated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Additionally, our data are consistent with further metabolism of citrate and lactate in the liver and kidneys. Citrate uptake in certain organs modulates age-related disease in mice and our data have similarities with age-related disease signatures in humans. Our results have implications for the role of telomere dysfunction in human aging in addition to its early diagnosis and the monitoring of anti-senescence therapeutics, especially those designed to improve telomere function.

Keywords: Cellular senescence, Citrate, Human aging, Metabolism, Telomeres

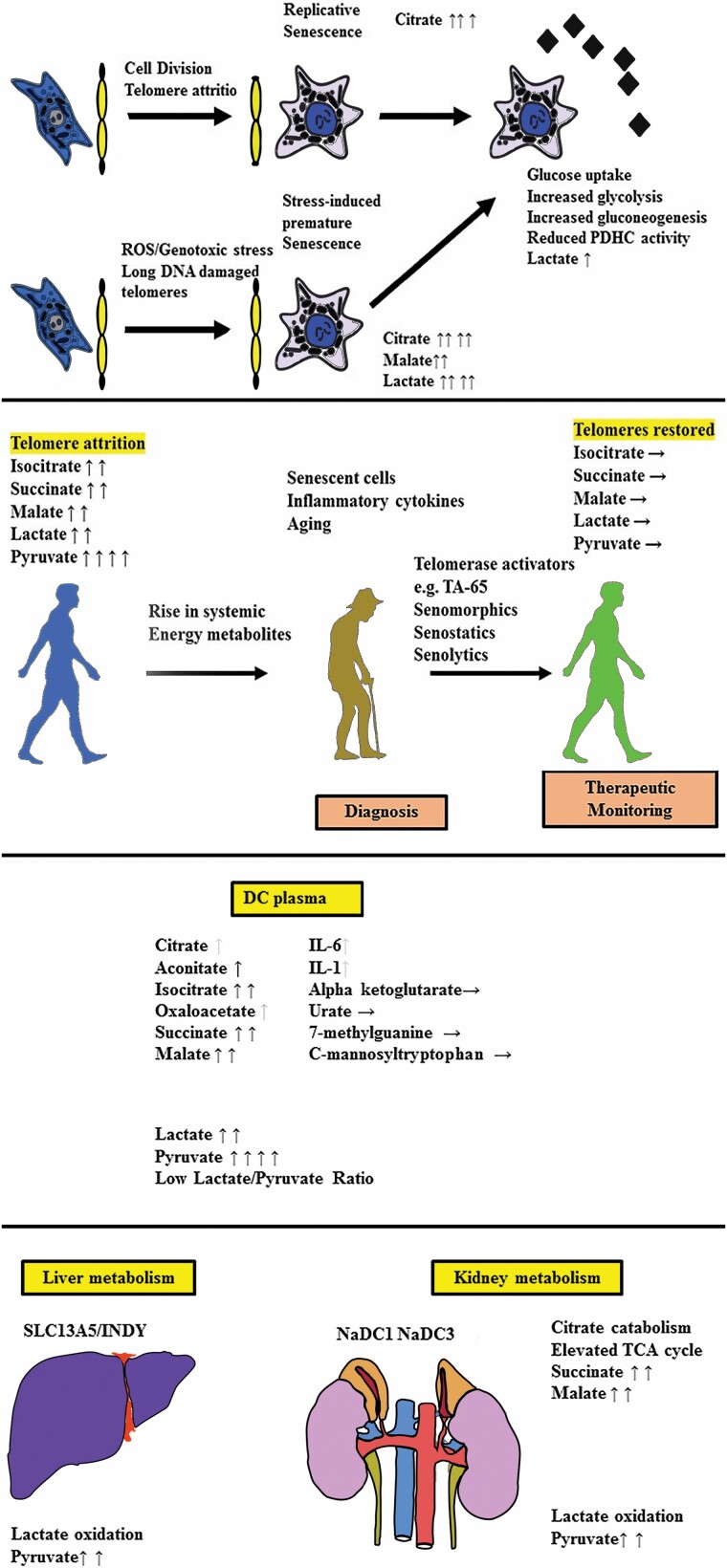

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Cellular senescence is a dynamic process induced by a variety of cellular stresses, including irreparable DNA double-strand breaks (IrrDSBs). IrrDSBs accumulate at telomeres following telomerase deficiency following telomere attrition (1) or in nondividing cells due to inadequate DNA repair (2,3). IrrDSBs are resolved by telomerase in dividing cells (4,5) but not so readily in nondividing cells.

Telomeres shorten in most human tissues with chronological age (6). Additionally, age-adjusted leukocyte telomere length (AALTL) is associated with poor health, especially cardiovascular disease (7), and is reversible upon positive changes in lifestyle (8) or telomerase activators (9).

In mice, telomere dysfunction induced by complete Tert or Terc deletion results in IrrDSBs, impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and function, decreased gluconeogenesis, cardiomyopathy, and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These phenotypes are countered by increased telomerase function (10) and excessively long telomeres (10,11), to benefit life span and health span. However, the extent of telomere attrition in dividing human cells with age is less dramatic than in tert−/− or terc−/− mice.

Telomere dysfunction is associated with senescence in human disease (12) but its influence on human metabolism and, in particular, the plasma biomarkers of age-related diseases, is not clear. To investigate this, we took advantage of dyskeratosis congenita (DC) patient plasma samples. DC patients possess heterozygous (TERT/TERC) or hemizygous (DKC1) rather than homozygous loss of function mutations, and DC is phenotypically closer to the terc+/− mouse than the tert−/− or terc−/− mouse (13).

DC patients display premature aging phenotypes and short telomeres in their tissues in vivo (14,15) and premature senescence in vitro (16). DC patients are a useful study group for the investigation of the effects of telomere dysfunction and senescence on human metabolism because the mechanism of premature senescence is characterized and DC patients do not usually have confounding conditions such as type 2 diabetes (T2D) at an early age, which would affect metabolism.

Telomere dysfunction culminates in cellular senescence, which is accompanied by the accumulation of an array of extracellular proteins and metabolites, known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP (17)) and the extracellular senescence metabolome (ESM (18)), respectively. Some metabolites of the ESM are associated with chronological aging in humans (19,20), but the underlying mechanisms are largely unknown. Several anti-senescence approaches are now being considered to ameliorate age-related diseases, including senolytic drugs (21), which have shown some promise in clinical trials. However, the noninvasive detection of senescent cells and/or telomere attrition in human disease is challenging owing to the small number of senescent cells and/or dysfunctional telomeres. SASP proteins are not generally detectable; their detectability varies in different disease states (22,23) and it is acknowledged that additional plasma biomarkers are needed (reviewed in (21)).

The ESM metabolite citrate is particularly interesting because its uptake has been implicated in aging, caloric restriction, T2D, blood pressure, heart rate, memory, adipocyte inflammation, epigenetic regulation, and cancer (reviewed in (24)), and so we initially investigated this metabolite.

Materials and Methods

Cell Characterization, Senescence Induction by Ionizing Radiation and Collection of Conditioned Medium

The cell culture methods, the senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay, and conditioned medium collection have been described previously (18). Glucose was measured using the Glucose Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), following the manufacturer instructions. BJ and normal human oral fibroblast line 1 (NHOF-1) cells have been described previously (18). BJ cells are normal newborn dermal fibroblasts (25) and NHOF-1 cells are normal oral fibroblasts derived from the buccal mucosa (26). Both BJ and NHOF-1 cells have low levels of p16INK4A (27) and can be immortalized by telomerase (25); see also Figure 1. BJ and NHOF-1 cell-line panels were tested for mycoplasma using a Lonza MycoAlertTM Mycoplasma Detection Kit and found to be negative.

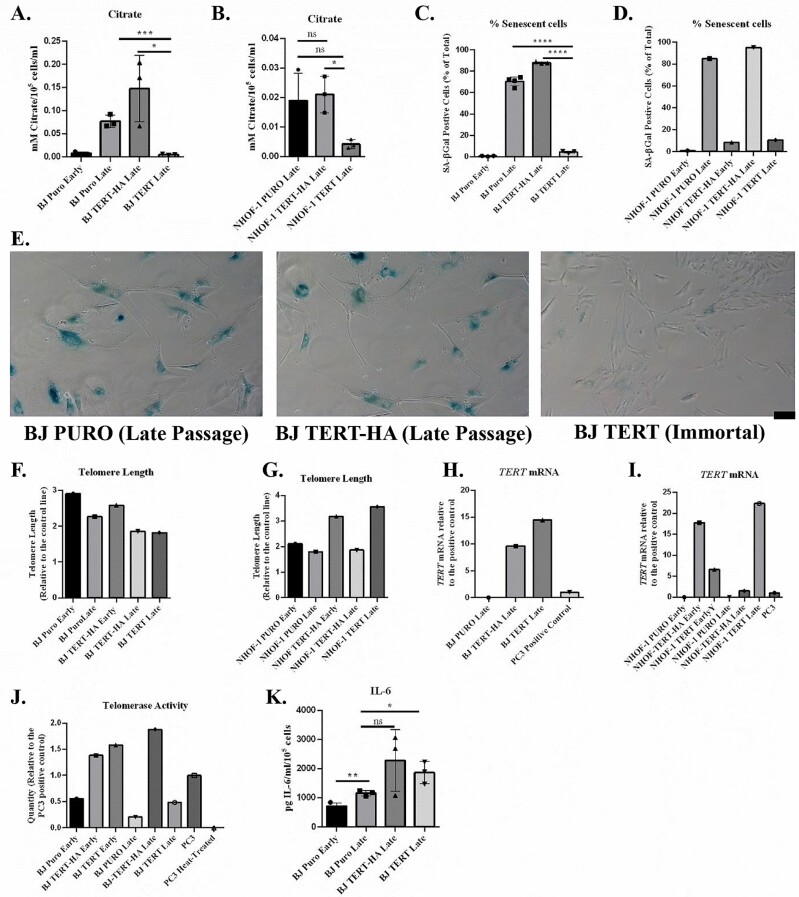

Figure 1.

Ectopic TERT but not TERT-HA expression suppresses extracellular citrate levels in parallel with senescence bypass. (A, B) The effect of ectopic TERT expression on citrate levels in (A) BJ cells and (B) NHOF-1 oral fibroblasts (n = 3). Data are means ± standard deviation. *p < .05; ***p < .001; ****p < .0001. (C, D) The percentage of senescent cells in (A) and (B) as assessed by (C) SA-βGal (n =3) and (D) is derived from 1 experiment. Symbols are the same as for (A) and (B). (E) Typical images of late passage SA-βGal-stained BJ cells transduced with the empty PURO vector, the TERT-HA construct (extrachromosomal TERT functions only), and TERT; black scale bar = 100 μm. (F, G) The telomere lengths of the cells analyzed in (A) and (B) at the point of senescence showing a clear increase in telomere length in NHOF-1 cells expressing TERT. Data are from 2 replicate runs of the same samples. (H, I) TERT mRNA levels in the cells from (A) and (B) at the point of senescence. Showing high levels of TERT and TERT-HA mRNA in both BJ and NHOF-1 cells. PC3 mRNA is the positive control. (J) Telomerase activity in the BJ cells from (A). The data are derived from 1 experiment in (A). PC3 is the positive control and heat-treated PC3 extract is the negative control. (K) IL-6 levels in the BJ cells from (A, n = 3). Data are means ± standard deviation. *p < .05; **p < .01.

Retroviral Infection of BJ and NHOF-1 Cells

pBABE retroviral vectors on the puromycin-resistant backbone expressing TERT and TERT-HA (28) or the empty vector were obtained from Addgene Europe (Teddington, Middlesex, UK). Retroviral particles were produced by the transfection of phoenix A cells and used to infect target cells. Transduced cells were selected with puromycin.

Patients, Normal Subjects, Plasma Collection, and Ethics

Ethical approval for the collection of normal and DC plasma samples and the metabolomics analysis were granted by the London-City and East Research Ethics Committee (certificate number 07/Q0603/5). Blood (2–10 mL) was collected by venipuncture using a 19-gauge butterfly needle into EDTA vacutainers from nonstarved healthy volunteers and DC patients. Within 2 hours, blood was centrifuged at 1 300g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet the blood cells. Following this, the plasma supernatant was transferred to a 1.5-mL Eppendorf centrifuge tube and centrifuged again at 20 600g for 2 minutes at 4°C. Plasma was then transferred to a fresh Eppendorf centrifuge tube and snap frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath for at least 15 minutes before storage at −80°C.

Patient symptoms, white blood cell counts, platelet counts, hemoglobin, and mean red blood cell corpuscular volume were all recorded at the time of diagnosis and in subsequent clinical assessment when samples were collected.

AALTL Measurement

Whole-blood telomere lengths were measured using the monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR (qPCR) method (29).

Telomere Length, hTERT Transcript, and Telomerase Activity Measurement

For the absolute telomere length analysis, a qPCR method was performed as described in (30). Telomerase activity using qPCR was performed using the TRAP protocol (31) and primer sequences as described. The quantification of fully spliced hTERT and GAPDH mRNA was described previously (32). RQ data analysis was initially performed using the SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA) and then plotted as bar charts in Prism.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

To measure the cytokines (interleukin-1 alpha [IL-1α], and interleukin-6 [IL-6]), a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (Quantikine ELISA Immunoassay, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) was employed following the manufacturer’s protocol. The detection limits were 3.9–250 pg/mL IL-1α and 3.13–300 pg/mL for IL-6.

Metabolomic Analysis

Unbiased metabolomic screen

The details of the unbiased metabolic screen have been published previously (18).

Targeted measurement of extracellular citrate by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

The methods for targeted gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis have been described previously (27).

Metabolite extraction and targeted analysis by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

For the analysis of organic acids from plasma, samples stored at −80°C were thawed at room temperature and 100 µL aliquots were treated with methanol (400 µL) to deproteinize the samples. The sample order was randomized before extraction. The samples were vortexed briefly, kept on ice for at least 60 min, then centrifuged (7 378g) for 10 min at 4°C. Multiple aliquots of the supernatant were collected and transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes. For the pooled QC sample, 75 µL of each sample supernatant was mixed in a new tube. Supernatants were dried in a centrifugal vacuum concentrator (Savant Speedvac, Thermo), and kept at −80°C until analysis.

Samples were reconstituted for analysis in 75 µL of a solution containing stable isotope-labeled (SIL) internal standards, made up in liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS) grade water at 1 µg/mL. The SIL standards were L-malic acid-13C4, succinic acid-13C4, sodium lactate-13C3, citric acid (1,5,6-carboxyl-13C3), and L-phenyl-d5-alanine (this last used to monitor the consistency of injection volumes, but not otherwise used to normalize the data). The reconstituted samples were then centrifuged and transferred to LC-MS vials.

The samples were analyzed by ion-pairing chromatography/mass spectrometry, as described fully in (33), with additional transitions added for the SIL standards, as listed in (34), using a XEVO TQ-S tandem mass spectrometer coupled to an Acquity ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) binary solvent manager equipped with a CTC autosampler (Waters Ltd, Wilmslow, UK). Briefly, data were acquired with electrospray ionization in negative mode, and the chromatography used a Waters HSS T3 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) with a binary solvent system of 10 mM tributylamine + 15 mM acetic acid in water (solvent A), and 80% methanol + 20% isopropanol (solvent B) to 100%. The sample run order was randomized. Before analysis, injections of double blanks (water) and single blanks (SIL standard mix) were performed to ensure system stability, and to identify carryover/contaminant peaks. A pooled QC sample was injected at the beginning of the run and then once every 10th injection throughout the run, to assess instrument stability across the entire analytical run. The compounds monitored were pyruvate, lactate, succinate, oxaloacetate, malate, 2-oxoglutarate, 7-methyl guanosine, urate, aconitate, isocitrate, citrate, α-C-mannosyltryptophan, plus the SIL standards as described earlier.

The LC-MS data were processed using Skyline (MacCoss Lab, Seattle, WA (35)). Blanks and QC samples were used to exclude contamination and low-quality samples, with acceptance criteria of <0.3 relative standard deviation for QC samples, and <1% peak area (of QC) in blanks. Metabolite concentrations were expressed as the ratio relative to the values for the SIL internal standards for each metabolite, except for those metabolites without a SIL standard available (pyruvate, isocitrate, α-C-mannosyltryptophan, urate, 7-methylguanosine, oxaloacetate, aconitate), for which relative count data were used.

Statistical Methods

Multivariate analysis

Two-way hierarchical clustering was performed using standardized data and Ward’s method of linkages for the control and DC groups separately. The heat map represents the compound concentrations. Principal components analysis was carried out using auto-scaled and mean-centered data. The first 4 PCs were inspected for associations with disease status, and the first 10 PCs used as input for Fisher’s linear discriminant analysis (LDA).

False discovery rates

False discovery rates (FDRs) of 0.05 were determined using an adaptive linear step-up procedure (36).

Other statistical methods

Cell culture and unbiased metabolomics screen data were analyzed by Student’s unpaired t test. Raw and normalized plasma metabolomics data were analyzed by the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney and Mann–Whitney U tests and corrected in the latter case for FDR. Linear regression analysis was conducted by using the Excel data analysis package and the graphs prepared in Excel.

Results

Citrate Is Regulated by Telomere Function and the Canonical Function of Telomerase, Independently From Inflammatory Cytokines In Vitro

Extracellular citrate (EC) and IL-6 both increased in senescent fibroblasts. The catalytic subunit of telomerase, TERT, reduced levels of EC (Figure 1A and B) in parallel with the frequency of senescence-associated beta galactosidase (Figure 1C and D) in both BJ fibroblasts and NHOF-1 cells, but the empty vector and TERT-HA (extrachromosomal telomerase functions only) did not (see also Figure 1E). The TERT-HA construct was made by Meyerson and colleagues (37) and turned out to be very useful because it does not lengthen telomeres or immortalize cells (28) even when ectopically expressed making it a useful control for TERT overexpression and extrachromosomal (noncanonical) TERT functions (38).

Only the TERT transgene was able to increase telomere length (Figure 1F and G) despite the fact that TERT-HA was expressed (Figure 1H and I) and induced telomerase activity in BJ cells (Figure 1J). These data demonstrate that EC is regulated by the canonical function of telomerase and links telomere function to EC accumulation in senescent fibroblasts. Neither TERT nor TERT-HA reduced IL-6 levels in BJ cells (Figure 1K) under the in vitro conditions described here indicating that EC is regulated independently from the inflammatory cytokines. These in vitro results gave rise to the hypothesis that plasma citrate is upregulated in vivo by telomere attrition.

Citrate, Malate, and Lactate Are Upregulated in Senescent Cells Induced by IrrDSBs

EC is upregulated following replicative senescence of oral fibroblasts (18). However, IrrDSB-induced senescence (IrrDSBsen) also induces telomere dysfunction along with EC, malate and lactate, and a depletion of pyruvate (all extracellular; see Supplementary Figure 1) consistent with a shift of senescent cell metabolism toward glycolysis.

DC Patients

The clinical and genetic characteristics of the DC patients are described in Supplementary Table 1, and the age and gender of all DC and control subjects in Supplementary Table 2.

Upregulation of Plasma Citrate in DC Patients Detected by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry

First, we analyzed the citrate levels of DC samples (n = 28) and controls (n = 12) using the GC-MS platform (Figure 2, top left). There was no significant difference in citrate levels when nonstarved plasma and starved serum samples were compared, suggesting that nutritional status did not affect plasma citrate levels. (Supplementary Figure 2A; p = .60). Plasma citrate levels were resistant to hemolysis (Supplementary Figure 2B) and stable at room temperature for 24 h, so citrate is a highly stable plasma metabolite in healthy controls. Citrate showed a strong trend for upregulation in DC patients when compared to controls (Figure 2, top left) but the effect was of only borderline significance (p = .06) except when only patients with more severe aplastic anemia symptoms were considered (p = .008). Asymptomatic DC patients in this study set were not significantly different from controls (p = .74).

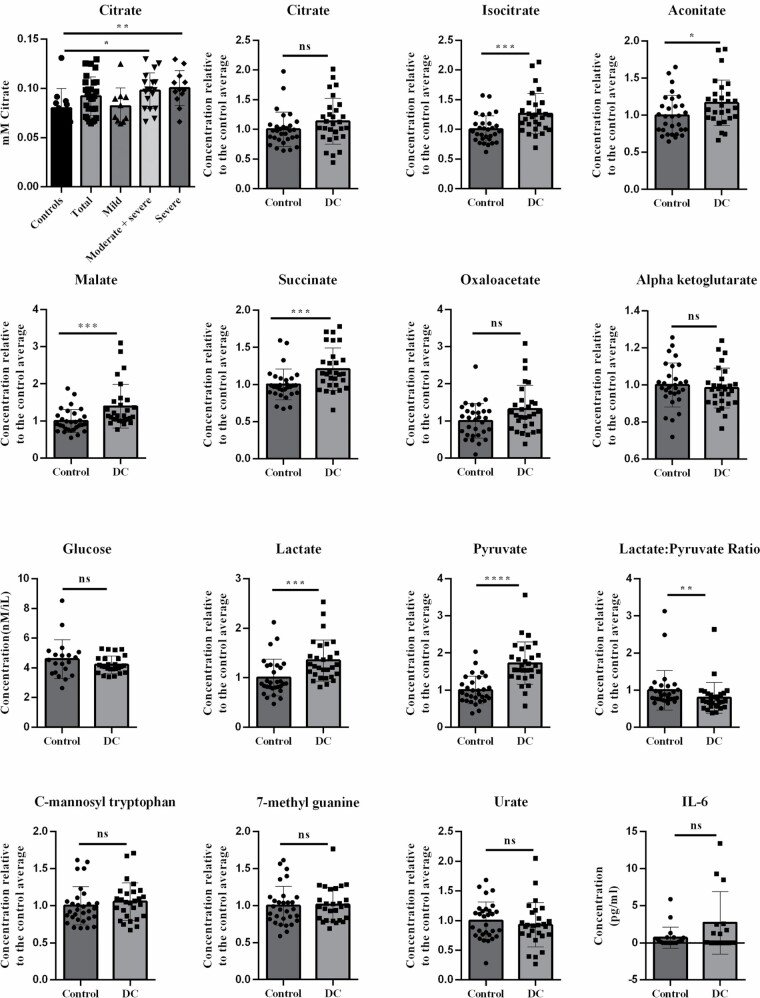

Figure 2.

Citrate, glucose, IL-6, and normalized metabolite levels in DC patient and control subject plasma. The far left-hand panel in the top row shows citrate levels in DC (n = 28) and normal control (n = 12) subjects as assessed by GC-MS. DC patients with mild aplastic anemia (0–1 abnormal clinical indicators n = 10), severe (3–4 clinical indicators, n = 12), or a combination of severe and moderate (2–4 clinical indicators, n = 18) are also shown to assess the effect of aplastic anemia on disease severity. Each point represents the average between 1 and 3 determinations all performed at the same time. Glucose levels are in mM in a subset of the DC patients (n = 26) and control subjects (n = 20). IL-6 levels are in pg/mL in a subset of the DC patients (n = 15) and control subjects (n = 21). All remaining panels show the LC-MS metabolite levels normalized to the average of the control subject levels in DC (n = 29) and control (n = 30). All p values were determined by the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney rank test and/or Welch’s test and both methods gave the similar p values. DC = dyskeratosis congenita; GC-MS = gas chromatography/mass spectrometry; IL-6 = interleukin-6; LC-MS = liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

DC Patients Show Specific Changes in Energy Metabolism

As plasma citrate is tightly regulated in vivo, we considered the possibility that citrate might be further metabolized in vivo to other energy metabolites. We used targeted LC-MS on an overlapping but distinct sample set to measure energy metabolites and a subset of ESM metabolites (18) in DC patient (n = 29) and control (n = 30) plasma (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). The metabolites were selected because they are altered in age-related diseases in vivo (20,39–43).

The TCA cycle metabolites isocitrate (p = .0007), malate (p = .0005), succinate (p = .008); and, to a lesser extent, oxaloacetic acid (p = .06), aconitate (p = .03), and citrate (p = .08) were elevated in DC samples, but other TCA cycle metabolites such as alpha ketoglutarate (AKG: p = .39) were not significantly altered. Lactate (p = .0003) and pyruvate (p = .0000007) levels were consistently elevated in DC patients relative to controls (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3A) and were significant after correction for FDR (Supplementary Figure 3B). Significantly, glucose levels were within the normal range in DC plasma, and the lactate:pyruvate ratio (LPR) was lower than normal (p = .005) arguing against lactic acidosis and T2D.

The DKC1 gene is X-linked and the DC patient set had a preponderance of males. However, all changes remained when only males were considered (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 3), in patient subsets with TERC or TERT mutations/variants, and in the case of pyruvate, DKC1 as well (Supplementary Table 3), arguing against a role for noncanonical functions of TERC and TERT. With the exception of succinate, all changes were significant in weakly symptomatic patients (Supplementary Table 3).

A subset of TCA metabolites, lactate, and pyruvate clearly distinguish DC patients from control subjects with high specificity and selectivity.

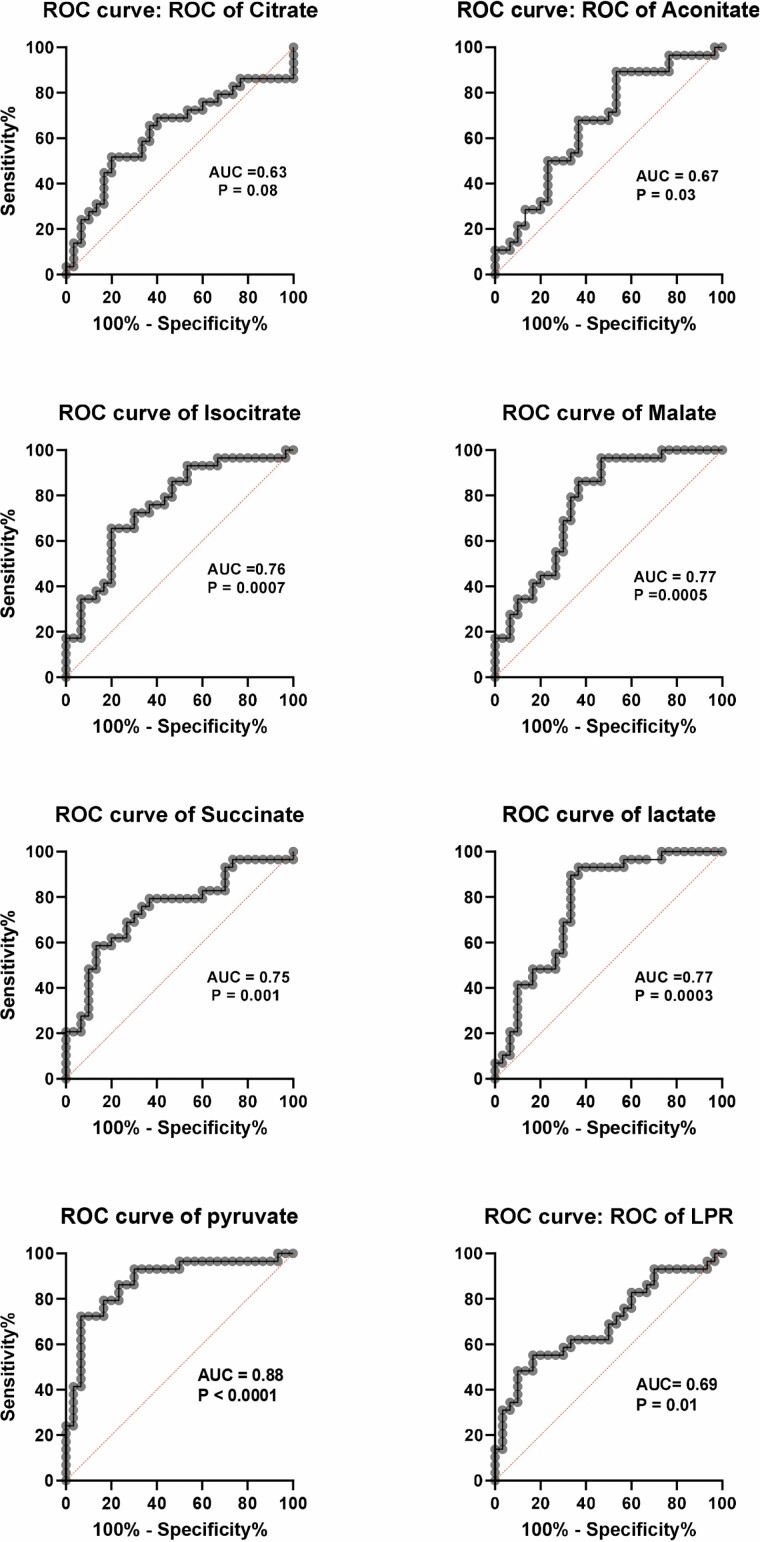

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves are shown in Figure 3 and clearly show the TCA cycle metabolites isocitrate (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.76), malate (AUC = 0.77), succinate (AUC = 0.75), and lactate (AUC = 0.77) gave acceptable discrimination between controls and DC; pyruvate (AUC = 0.88) gave a value that was excellent bordering on outstanding. Thus, high plasma pyruvate alone could indicate systemic telomere attrition.

Figure 3.

ROC curves of TCA metabolites, lactate and pyruvate in DC patient and control subject plasma. The data show ROC curves of the normalized LC-MS metabolite levels shown in Figure 2, but identical data were obtained from non-normalized values. The AUC and p values are given on each graph. An AUC of more than 0.70 is considered good and a value of more than 0.80 is considered excellent. AUC = area under the curve; DC = dyskeratosis congenita; LC-MS = liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry; ROC = receiver operator characteristic.

Relationship of DC Profile to Leukocyte Age-Associated Telomere Loss

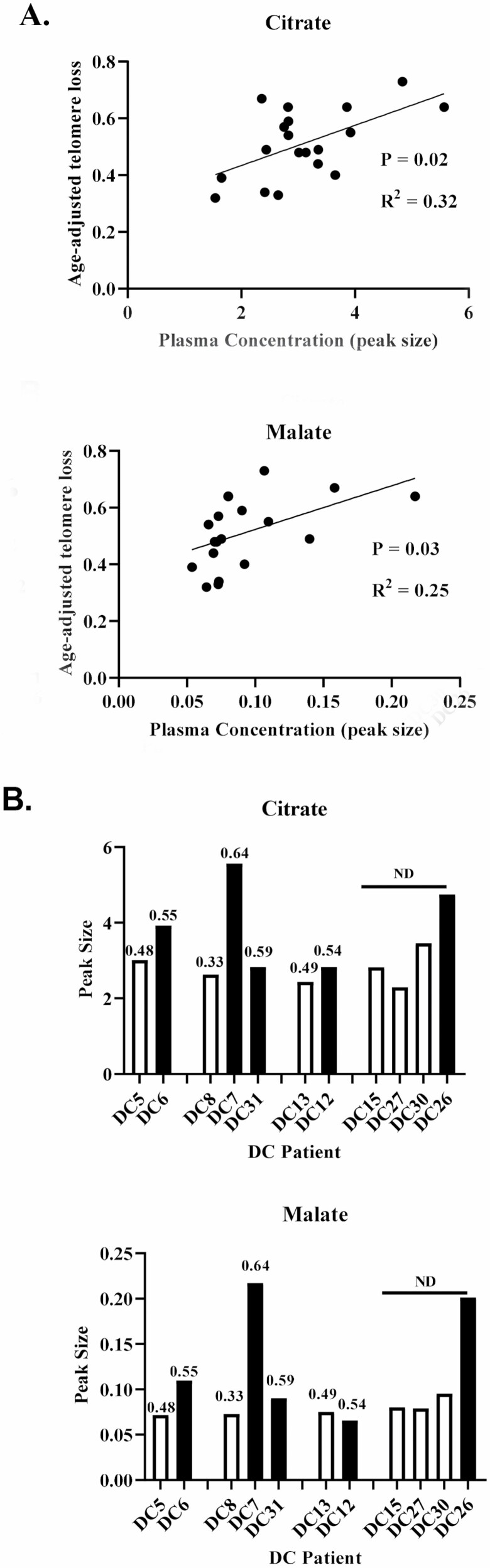

Linear regression analysis (Figure 4A; Supplementary Table 4) showed that only citrate (p = .01) and malate (p = .03) levels correlated with leukocyte age-associated telomere loss (LAATL). In the smaller GC-MS data set, only citrate correlated with LAATL in the DC subgroup with TERC mutations by linear regression analysis (p = .006).

Figure 4.

Citrate is associated with DC leukocyte telomere loss and a shift in systemic energy metabolism. (A) Linear regression analysis showing a statistically significant association between age-adjusted telomere reduction (LAATL) and plasma citrate (upper panel) and malate (lower panel) in DC patients (n = 19). (B) Non-normalized data from 4 DC families showing that DC patients with shorter telomeres than their older relatives carrying the same mutation show a trend for increased plasma citrate (upper panel) and malate (lower panel). The values over the bars indicate the level of age-adjusted telomere reduction. DC = dyskeratosis congenita; LAATL = leukocyte age-associated telomere loss.

In addition, as with telomerase-deficient mice (13), LAATL decreases with each generation (44). We, therefore, examined the DC profile in individual family members from 4 DC families harboring the same TERT or TERC mutation/variant (Figure 4B). Although the numbers were small, in 3 families, the offspring had higher levels of citrate and malate than their parents/aunts. In 2 families, lower LAATLs were also associated with higher IL-6. These data support the inverse relationship between these metabolites and LAATL.

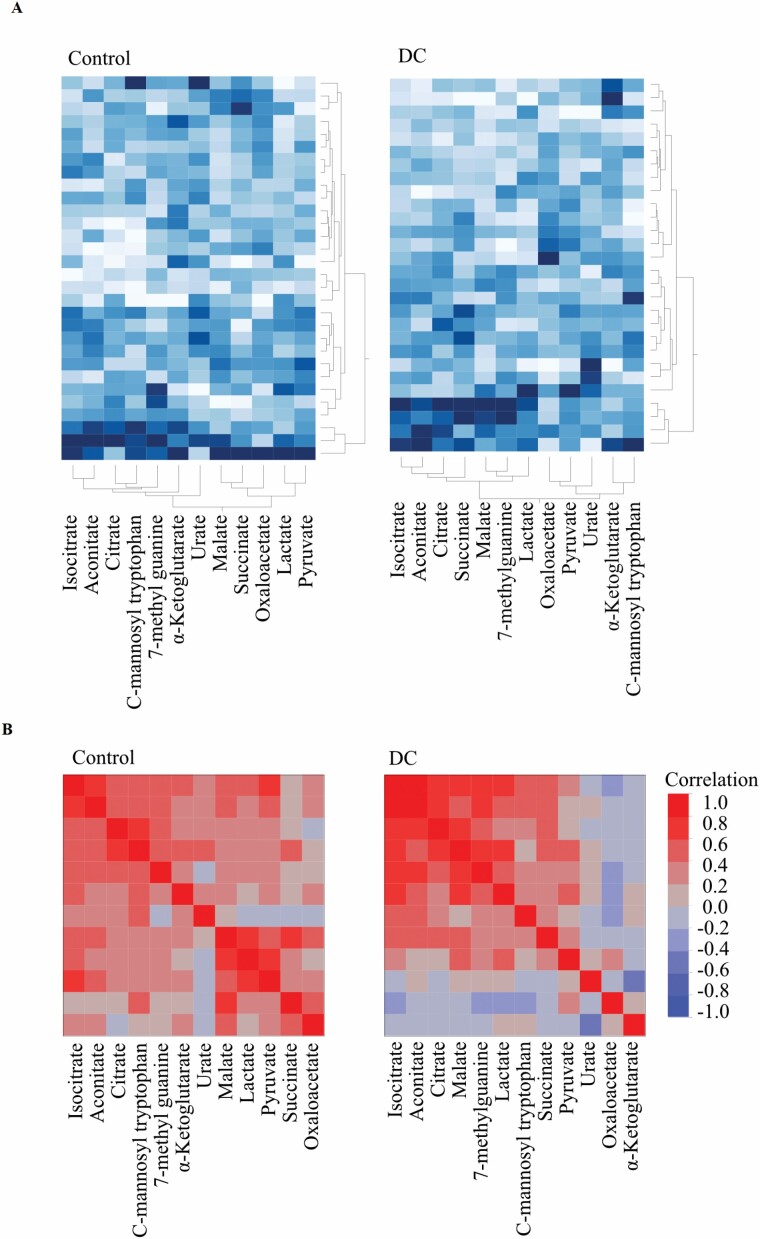

DC Patients Show a Shift in Energy Metabolism Indicative of Increased Citrate Catabolism

Unsupervised multivariate analyses also showed clear differences between the control and DC groups. The 2 groups were largely separated by principal component analysis within the first 2 components (Supplementary Figure 4). There was no association with patient age for the first 4 principal components (p > .05 for all). The between-metabolite correlations were also different in the 2 groups, as showed by both clustered heat-maps of the Pearson correlations (Figure 5A), and 2-way hierarchical clustering of the 2 groups (Figure 5B). Unsurprisingly, plasma TCA metabolites citrate, isocitrate, and aconitate clustered together in normal subjects, whereas lactate, pyruvate, and malate formed a separate cluster. However, in DC plasma, citrate, aconitate, and isocitrate became much more strongly associated with malate and succinate indicating a shift in systemic metabolism in DC patients. In addition, isocitrate and malate became more strongly associated with lactate in DC patient plasma. Linear regression analysis (Supplementary Table 5) and scatter plot matrices (Supplementary Figure 5A and B) further supported these conclusions. Furthermore, supervised LDA correctly classified 24 out of 30 control and 24 out of 28 DC patient samples; however, as the AUC (0.90) was not significantly different from the best single metabolite AUC values (95% confidence intervals: 0.87–0.99, 5 000 bootstraps), we did not explore the use of LDA further.

Figure 5.

Citrate becomes more associated with malate and succinate in DC. (A) Clustered heat map of correlations derived from normalized metabolite levels in normal subjects (left panel) and DC plasma (right panel) showing the relationship of each metabolite to citrate and showing an increased association of citrate with isocitrate, aconitate, and especially malate and succinate. (B) Cluster analysis of the data in (A). DC = dyskeratosis congenita.

DC Patients Show Elevated Levels of Energy Metabolites in the Absence of High Levels of SASP and Other ESM Factors

We did not have access to tissue biopsies of DC patients so to estimate the amount of cellular senescence we measured several SASP and ESM factors. IL-1α and IL-6 levels were measured in some of the samples. IL-6 levels were generally undetectable in control subjects, as expected, but were also very low in most of the DC samples and not significantly different from controls (p = .09). IL-1α levels were below detection limits in all but one of the DC patients (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Table 3A).

In addition, we tested ESM metabolites, previously associated with aging (20), mortality (40,41), and age-related disease (40,41). The plasma concentrations of the ESM metabolites urate, 7-methyl guanine (7-MG), and C-mannosyl tryptophan were not significantly different from controls (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Table 3). The data indicate a low level of cellular senescence in DC patients.

DC Profile and SASP Factors

Only citrate (p = .01 when analyzed by GC-MS), isocitrate (p = .02), and 7-MG (p = .008) correlated with plasma IL-6 levels (Supplementary Table 6), indicating that the energy metabolite changes were largely independent of IL-6.

DC Profile and Clinical Parameters, Age, and Gender

In both the GC-MS and LC-MS data sets, there was no significant relationship between any of the previous changes and any clinical indicators of aplastic anemia, gender, donor age, or different control batches, and with the exception of oxaloacetic acid and urate repeat samples, values varied by less than 25% (1%–22%).In both the GC-MS and LC-MS data sets (Supplementary Tables 7–10). Low-dose Danazol treatment in a small patient subset had no effect on the results, succinate excepted (Supplementary Table 11).

Discussion

The ESM metabolites citrate and malate correlated with LAATL but other metabolites were better at separating DC patients from controls, indicating further, or tissue-specific effects of telomere attrition on metabolism. DC plasma metabolites were not associated with any particular disease phenotype, and so are unlikely to be a consequence of disease. Trivial explanations such as cell lysis and exosome release are inconsistent with the normal levels of the cytoplasmic metabolites urate and AKG in DC plasma.

Significantly, virtually all aspects of the DC profile increase with chronological age and age-related disease (19,20,24,39,45). High isocitrate, aconitate, and malate are associated with frailty, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in humans (39,42,43). Therefore, the plasma energy alterations are not limited to DC. AKG, which extends life span and protects against frailty and inflammaging in mice (46), was not significantly altered, consistent with the recent studies of aged or frail humans (19,39,42,45). However, plasma AKG increases in centenarians (45), and although this may reflect further telomere attrition or age-related disease, it could reflect an adaptive mechanism in long-lived individuals.

Although it is difficult to speculate on the mechanistic details from plasma metabolite levels, the low LPR and normal levels of urate distinguish DC from T2D, most respiratory chain disorders and all forms of acidosis (47–49). The high levels of isocitrate and aconitate in DC are opposite to those in humans deficient in the ROS-sensitive (50) mitochondrial aconitase (ACO2) (51), arguing against an increase in mitochondrial ROS in DC. The DC profile most closely resembles pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency (49) and a shift toward glycolysis.

Only citrate and malate levels correlated with LAATL yet isocitrate, succinate, lactate, and pyruvate were consistently elevated in DC plasma. Telomere attrition may have different direct consequences on metabolism in other cell types such as the liver.

An alternative hypothesis is that elevated plasma citrate in DC patients enters the liver and kidneys to drive the TCA cycle to cause altered metabolism. A recent study conducted on pigs offers some support for this hypothesis. A sampling of arterial and venous blood in pigs showed that citrate taken up by the kidneys contributes to the TCA cycle to produce malate and succinate (52), which accumulate in kidney tissue (52). This could explain the higher plasma levels of these and other TCA metabolites in DC plasma and with chronological age.

Lactate and pyruvate levels are also associated with chronological aging in humans (19,20,45) as well as DC. Lactate is oxidized predominantly in the liver and kidneys to pyruvate (52) to regulate its levels and could produce the low LPR and high pyruvate observed in the DC patient plasma.

Terc-/- and terc-/- mice telomeres often lack detectable telomere DNA and form end-to-end chromosomal fusions reminiscent of crisis and cancer. However, a recent study of a large cohort of DC leukocytes employing Single Telomere Length Analysis showed no evidence of telomere fusions such as those found in cellular crisis or cancer despite the fact that some telomere lengths are very short (53). This suggests that the observed phenotypes in DC are mediated independently of telomere fusions, perhaps by unrepaired DNA double-strand breaks, which are known to occur following telomere attrition and replicative senescence (1).

Regardless of the underlying mechanism, the systemic accumulation of energy metabolites in DC and aging subjects would likely accelerate aging and cellular senescence as caloric restriction does the reverse (54).

The most important aspect of the data described here is that a subset of plasma metabolites (isocitrate, malate, succinate, lactate, and pyruvate) outperformed SASP factors in distinguishing DC patients from controls. Such metabolites may be valuable indicators of telomere dysfunction in humans and consequently therapies designed to reverse it (9,55).

Conclusion

In summary, although mechanistic details are still to be elucidated, plasma metabolomics may have considerable utility in the monitoring of telomere dysfunction in human disease, regenerative medicine, and anti-aging therapies. In addition, combining metabolomics with defined human mutations may shed light on the underlying mechanisms of aging and contribute to the early diagnosis of age-related diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Tom Vulliamy for performing the telomere length analysis of the human leukocytes, Dr. Harriet Allan and Professor Tim Warner for assistance with blood samples from normal volunteers, Dr. Amy Lewis for technical advice, and Mr. Lindsay Parkinson for graphical design. We would also like to thank Dr. Fabian Flores-Borja for valuable discussions regarding the metabolism of citrate and Professors Andrew Silver and Julie Adam (University of Oxford) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Emma Naomi James, Centre for Oral Immunology and Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Dentistry, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Virag Sagi-Kiss, Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Burlington Danes Building, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Mark Bennett, Department of Life Sciences, South Kensington, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Maria Elzbieta Mycielska, Department of Structural Biology, Institute of Biophysics and Physical Biochemistry, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany.

Lee Peng Karen-Ng, Centre for Oral Immunology and Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Dentistry, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Terry Roberts, College of Health, Medical and Life Sciences, Brunel University London, Middlesex, UK.

Sheila Matta, College of Health, Medical and Life Sciences, Brunel University London, Middlesex, UK.

Inderjeet Dokal, Centre for Genomics and Child Health, Blizard Institute, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Jacob Guy Bundy, Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Burlington Danes Building, Imperial College London, London, UK.

Eric Kenneth Parkinson, Centre for Oral Immunology and Regenerative Medicine, Institute of Dentistry, Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK.

Funding

The work was supported by the Dunhill Medical Trust (grant number R452/1115) and Barts and the London Charity (grant number MRD&U0004) and Euorpean Union H2020 (grant number 633589). L.P.K.-N. received a PhD scholarship (Hadiah Latihan Persekutuan) from the Malaysian Ministry of Education.

Conflict of Interest

M.E.M. is a co-inventor on the Patent Application no. EP15767532.3 and US2020/408741 (status patent pending) and US2017/0241981 (patent issued) “The plasma membrane citrate transporter for use in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer” owned by the University Hospital Regensburg. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

E.N.J. and M.B. performed the gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of the conditioned medium and plasma samples; V.S.-K. performed the liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of plasma samples; M.E,M., E.K.P. and J.G.B. performed the statistical analysis of all the data; E.K.P. and J.G.B prepared the figures; L.P.K.-N. performed the ELISA assays; T.R. performed the qPCR analysis of TERT and telomerase on the fibroblast lines; S.M. performed the telomere length analysis. I.D provided the patient samples, the telomere length data, and all the clinical data in addition to obtaining ethical approval for the study; E.K.P. conceived the study, obtained funding, performed most of the in vitro experiments, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. E.K.P., M.E.M., I.D., and J.G.B. analyzed the data and finalized the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1. d’Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fumagalli M, Rossiello F, Clerici M, et al. Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:355–365. doi: 10.1038/ncb2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hewitt G, Jurk D, Marques FD, et al. Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat Commun. 2012;3:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel PL, Suram A, Mirani N, Bischof O, Herbig U. Derepression of hTERT gene expression promotes escape from oncogene-induced cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E5024–E5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suram A, Kaplunov J, Patel PL, et al. Oncogene-induced telomere dysfunction enforces cellular senescence in human cancer precursor lesions. EMBO J. 2012;31:2839–2851. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Demanelis K, Jasmine F, Chen LS, et al. Determinants of telomere length across human tissues. Science. 2020;369:eaaz6876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Q, Zhan Y, Pedersen NL, Fang F, Hagg S. Telomere length and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;48:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sellami M, Bragazzi N, Prince MS, Denham J, Elrayess M. Regular, intense exercise training as a healthy aging lifestyle strategy: preventing DNA damage, telomere shortening and adverse DNA methylation changes over a lifetime. Front Genet. 2021;12:652497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dow CT, Harley CB. Evaluation of an oral telomerase activator for early age-related macular degeneration—a pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chakravarti D, LaBella KA, DePinho RA. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2021;184:306–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Munoz-Lorente MA, Cano-Martin AC, Blasco MA. Mice with hyper-long telomeres show less metabolic aging and longer lifespans. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rossiello F, Jurk D, Passos JF, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Telomere dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:135–147. doi: 10.1038/s41556-022-00842-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, et al. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 2005;123:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadalla SM, Cawthon R, Giri N, Alter BP, Savage SA. Telomere length in blood, buccal cells, and fibroblasts from patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vulliamy TJ, Knight SW, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Very short telomeres in the peripheral blood of patients with X-linked and autosomal dyskeratosis congenita. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:353–357. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun C, Wang K, Stock AJ, et al. Re-equilibration of imbalanced NAD metabolism ameliorates the impact of telomere dysfunction. EMBO J. 2020;39:e103420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e3012853–e3012868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James EL, Michalek RD, Pitiyage GN, et al. Senescent human fibroblasts show increased glycolysis and redox homeostasis with extracellular metabolomes that overlap with those of irreparable DNA damage, aging, and disease. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:1854–1871. doi: 10.1021/pr501221g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Auro K, Joensuu A, Fischer K, et al. A metabolic view on menopause and ageing. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Menni C, Kastenmuller G, Petersen AK, et al. Metabolomic markers reveal novel pathways of ageing and early development in human populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1111–1119. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campisi J, Kapahi P, Lithgow GJ, Melov S, Newman JC, Verdin E. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature. 2019;571:183–192. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1365-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:446–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Justice JN, Nambiar AM, Tchkonia T, et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:554–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mycielska ME, James EN, Parkinson EK. Metabolic alterations in cellular senescence: the role of citrate in ageing and age-related disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, et al. Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pitiyage GN, Slijepcevic P, Gabrani A, et al. Senescent mesenchymal cells accumulate in human fibrosis by a telomere-independent mechanism and ameliorate fibrosis through matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2011;223:604–617. doi: 10.1002/path.2839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. James ENL, Bennett MH, Parkinson EK. The induction of the fibroblast extracellular senescence metabolome is a dynamic process. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Counter CM, Hahn WC, Wei W, et al. Dissociation among in vitro telomerase activity, telomere maintenance, and cellular immortalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14723–14728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e21–e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O’Callaghan NJ, Fenech M. A quantitative PCR method for measuring absolute telomere length. Biol Proced Online. 2011;13:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wege H, Chui MS, Le HT, Tran JM, Zern MA. SYBR green real-time telomeric repeat amplification protocol for the rapid quantification of telomerase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:E3–E3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ducrest AL, Amacker M, Mathieu YD, et al. Regulation of human telomerase activity: repression by normal chromosome 3 abolishes nuclear telomerase reverse transcriptase transcripts but does not affect c-Myc activity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7594–7602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sagi-Kiss V, Li Y, Carey MR, et al. Ion-pairing chromatography and amine derivatization provide complementary approaches for the targeted LC-MS analysis of the polar metabolome. J Proteome Res. 2022;21:1428–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perin G, Fletcher T, Sagi-Kiss V, et al. Calm on the surface, dynamic on the inside: molecular homeostasis of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 nitrogen metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44:1885–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pino LK, Searle BC, Bollinger JG, Nunn B, MacLean B, MacCoss MJ. The skyline ecosystem: informatics for quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2020;39:229–244. doi: 10.1002/mas.21540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Benjamini Y, Krieger AM, Yekutieli D. Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika. 2006;93:491–507. doi: 10.1093/biomet/93.3.491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyerson M, Counter CM, Eaton EN, et al. hEST2, the putative human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, is up-regulated in tumor cells and during immortalization. Cell. 1997;90:785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80538-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart SA, Hahn WC, O’Connor BF, et al. Telomerase contributes to tumorigenesis by a telomere length-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12606–12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cheng S, Larson MG, McCabe EL, et al. Distinct metabolomic signatures are associated with longevity in humans. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hocher B, Adamski J. Metabolomics for clinical use and research in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:269–284. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang J, Weinstein SJ, Moore SC, et al. Serum metabolomic profiling of all-cause mortality: a prospective analysis in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention (ATBC) Study Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187:1721–1732. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marron MM, Harris TB, Boudreau RM, et al. Metabolites associated with vigor to frailty among community-dwelling older Black men. Metabolites. 2019;9:83. doi: 10.3390/metabo9050083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yeri A, Murphy RA, Marron MM, et al. Metabolite profiles of healthy aging index are associated with cardiovascular disease in African Americans: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74:68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Szydlo R, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nat Genet. 2004;36:447–449. doi: 10.1038/ng1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mota-Martorell N, Jove M, Borras C, et al. Methionine transsulfuration pathway is upregulated in long-lived humans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;162:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Asadi Shahmirzadi A, Edgar D, Liao CY, et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate, an endogenous metabolite, extends lifespan and compresses morbidity in aging mice. Cell Metab. 2020;32:447–456.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Robinson BH. Lactic acidemia and mitochondrial disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;89:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shaham O, Slate NG, Goldberger O, et al. A plasma signature of human mitochondrial disease revealed through metabolic profiling of spent media from cultured muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1571–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thompson Legault J, Strittmatter L, Tardif J, et al. A metabolic signature of mitochondrial dysfunction revealed through a monogenic form of Leigh syndrome. Cell Rep. 2015;13:981–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lushchak OV, Piroddi M, Galli F, Lushchak VI. Aconitase post-translational modification as a key in linkage between Krebs cycle, iron homeostasis, redox signaling, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Redox Rep. 2014;19:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Abela L, Spiegel R, Crowther LM, et al. Plasma metabolomics reveals a diagnostic metabolic fingerprint for mitochondrial aconitase (ACO2) deficiency. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jang C, Hui S, Zeng X, et al. Metabolite exchange between mammalian organs quantified in pigs. Cell Metab. 2019;30:594–606 e593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Norris K, Walne AJ, Ponsford MJ, et al. High-throughput STELA provides a rapid test for the diagnosis of telomere biology disorders. Hum Genet. 2021;140:945–955. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02257-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fontana L, Nehme J, Demaria M. Caloric restriction and cellular senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018;176:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bernardes de Jesus B, Schneeberger K, Vera E, Tejera A, Harley CB, Blasco MA. The telomerase activator TA-65 elongates short telomeres and increases health span of adult/old mice without increasing cancer incidence. Aging Cell. 2011;10:604–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.