This randomized clinical trial examines the efficacy of online mindfulness and self-compassion training in addition to usual care in improving the quality of life of adults with atopic dermatitis.

Key Points

Question

Is online group mindfulness and self-compassion training efficacious in improving the quality of life (QOL) of adults with atopic dermatitis (AD)?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 107 adults with AD, mindfulness and self-compassion training in addition to usual care showed significantly greater improvements in patient-reported skin disease–specific QOL compared with a waiting list control at 13-week assessment. There were few dropouts, and the effect size was large.

Meaning

These results suggest that online group mindfulness and self-compassion training improves QOL in synergy with dermatological treatments.

Abstract

Importance

Quality of life (QOL) of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) is reported to be the lowest among skin diseases. To our knowledge, mindfulness and self-compassion training has not been evaluated for adults with AD.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of mindfulness and self-compassion training in improving the QOL for adults with AD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial conducted from March 2019 through October 2022 included adults with AD whose Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score, a skin disease–specific QOL measure, was greater than 6 (corresponding to moderate or greater impairment). Participants were recruited from multiple outpatient institutes in Japan and through the study’s social media outlets and website.

Interventions

Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive eight 90-minute weekly group sessions of online mindfulness and self-compassion training or to a waiting list. Both groups were allowed to receive any dermatologic treatment except dupilumab.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the change in the DLQI score from baseline to week 13. Secondary outcomes included eczema severity, itch- and scratching-related visual analog scales, self-compassion and all of its subscales, mindfulness, psychological symptoms, and participants’ adherence to dermatologist-advised treatments.

Results

The study randomized 107 adults to the intervention group (n = 56) or the waiting list (n = 51). The overall participant mean (SD) age was 36.3 (10.5) years, 85 (79.4%) were women, and the mean (SD) AD duration was 26.6 (11.7) years. Among participants from the intervention group, 55 (98.2%) attended 6 or more of the 8 sessions, and 105 of all participants (98.1%) completed the assessment at 13 weeks. The intervention group demonstrated greater improvement in the DLQI score at 13 weeks (between-group difference estimate, −6.34; 95% CI, −8.27 to −4.41; P < .001). The standardized effect size (Cohen d) at 13 weeks was −1.06 (95% CI, −1.39 to −0.74). All secondary outcomes showed greater improvements in the intervention group than in the waiting list group.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial of adults with AD, integrated online mindfulness and self-compassion training in addition to usual care resulted in greater improvement in skin disease–specific QOL and other patient-reported outcomes, including eczema severity. These findings suggest that mindfulness and self-compassion training is an effective treatment option for adults with AD.

Trial Registration

https://umin.ac.jp/ctr Identifier: UMIN000036277

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory, multifactorial skin disease associated with intense itching.1,2 The prevalence of AD is estimated to be 15% to 30% in children and 2% to 10% in adults, with the incidence increasing in industrialized countries.1,3,4 Sleep difficulties, anxiety, and depression are reported to be common comorbidities of AD. Symptoms of AD are associated with significant effects on patients’ quality of life (QOL).5,6,7 Given its prevalence and effects, AD has the highest disease burden among skin diseases, as measured by disability-adjusted life years.8 Treatment options include medications, skincare, and lifestyle changes. There are new biologic medications that show effectiveness, but they may not be widely available due to high costs, and they need to be investigated for their long-term safety. While previous studies have highlighted the importance of psychological interventions,9,10 they were mostly conducted in pediatric populations,11 were often limited in sample size, were delivered in individual formats, combined psychological interventions with specific physical treatments, and did not examine the effects on QOL.12,13,14,15 A recent review reported that patients with AD would benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy plus dermatologic treatment compared with only receiving the standard-of-care treatment.16

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was introduced in the 1970s for coping with chronic pain17,18 and has been increasingly applied to various clinical disorders.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 Self-compassion is a key factor in mindfulness-based interventions.27,28 Mindful self-compassion (MSC) was developed in 201029 and has been applied to general and clinical populations.30 While MBSR focuses on building a nonjudgmental relationship with stress, MSC emphasizes a compassionate relationship with oneself during a time of suffering. Standard MBSR and MSC courses require 8 weekly interactive sessions, each lasting 150 to 180 minutes; a full-day or half-day silent retreat; and at least 30 to 40 minutes of daily home practice.

One study showed that MBSR resolved symptoms 4 times faster than phototherapy treatments alone among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.31 No studies to our knowledge have examined the efficacy of MBSR or MSC in patients with AD. Thus, clinically relevant programs for AD are needed. We developed an integrated program that adapted and combined elements of MBSR and MSC. We hypothesized that the intervention would improve the skin disease–specific QOL and reduce patient-reported AD severity and other symptoms. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the efficacy of an online group mindfulness and self-compassion–integrated intervention for adults diagnosed with AD.

Methods

Trial Design

The Self-Compassion and Mindfulness Integrated Online Program for People Living With Eczema (SMiLE) study is a randomized clinical trial (UMIN000036277) (trial protocol in Supplement 1). The trial was conducted from March 2019 through October 2022. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki32 on the ethical principles established for research involving human participants and the ethical guidelines for clinical studies published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. All participants provided electronically signed informed consent. Compensation of online gift cards ($8 for 4-week and 9-week assessments and $16 for the 13-week assessment) was provided to both groups. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Participants

Participants were recruited at multiple outpatient academic medical centers and private practices in Japan and through social media posts and the study website between July 2019 and June 2022. Participants were assessed for eligibility and were included in the study if they (1) were aged 18 to 64 years; (2) reported a dermatologist-confirmed AD diagnosis; (3) met self-reported criteria of itchy skin and bilateral symmetric eczema with continuing symptoms for over 6 months; (4) scored greater than 6 points on the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),33,34 indicating moderate to extremely large skin disease–specific QOL changes; (5) could access the internet for the online program; and (6) could attend all sessions and complete home practice. Patients were excluded if they (1) were administered dupilumab treatment, the only newly marketed drug at study commencement; (2) were diagnosed with psychosis, personality disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or acute stress disorder; (3) received psychotherapy during the study; (4) attended other mindfulness or compassion programs; (5) were unable to understand Japanese; (6) were relatives of study researchers; or (7) were deemed ineligible to participate by study researchers.

All applicants were first requested to confirm these criteria in the REDCap database.35 Additional screening interviews and an explanation of the trial took place in an individual, 1-hour online meeting.

Randomization and Blinding

After completing screening and creating a cohort, we randomized participants 1:1 to the mindfulness and self-compassion group or the waiting list group using block randomization with a block size of 4, stratified by sex, age (<30 or ≥30 years), and baseline DLQI score (<11 or ≥11 on a 0 to 30 scale). An independent statistician (T.I.) received the participant list and conducted the randomization remotely. Group allocation was concealed until participants were randomized to their respective group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Participants and the therapist or investigator (S.K.) were not blinded to the treatment allocation because of the nature of the interventions. All outcome assessments were completed electronically by participants. The therapist and the statistician remained blinded to the outcome data until the trial was completed and analyzed.

Interventions

The online, group-based mindfulness and self-compassion intervention was a psychological and behavioral training integrating elements of MBSR and MSC. This involved weekly, 90-minute interactive online sessions over 8 weeks; an optional silent, 5.5-hour meditation retreat; and an optional 120-minute Zoom videoconferencing booster session. All 8 sessions were conducted entirely online weekly on the same day and time of the week. Participants chose between an offline or online format for the optional silent meditation retreat. After the COVID-19 outbreak, this optional retreat was only conducted online.

The first 3 sessions incorporated key elements of MBSR. Sessions 4 to 8 contained key elements of MSC (Table 1). Each session included meditation, informal psychoeducation, inquiry, and a short lecture. As with MBSR or MSC, this hybrid program intentionally was not limited to disease-specific topics but instead focused on a way of living as a whole person, which in this case included experiencing AD, and taking care of oneself wisely and kindly. Participants were not advised about any particular treatment plan, and the therapist respected their dermatologic treatment decisions. Participants were given home practice regimens. Participant instructions were available on the educational technology platform PowerSchool Learning. Participants could watch videos to deepen their understanding. All sessions were video recorded for monitoring facilitation quality and protocol adherence.

Table 1. Outline of Program Sessions.

| Week | Course adaptation | Main theme | Duration, min |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | NA | Orientation | 120 |

| 1 | MBSR | Introduction to mindfulness and awareness of body | 90 |

| 2 | MBSR | Awareness of body and breath | 90 |

| 3 | MBSR | Reactivity and responding to stress | 90 |

| 4 | MSC | Introduction to self-compassion | 90 |

| 5 | MSC | Loving kindness for oneself, inner compassionate voice for self-motivation | 90 |

| 6 | MSC | Meeting with difficult emotions | 90 |

| 7 | MBSR and MSC | Optional 1-d silent meditation retreat | 330 |

| 8 | MSC | Being with shame kindly | 90 |

| 9 | MSC | Self-appreciation, integration for continued practice | 90 |

| 13 | NA | Optional booster session | 120 |

Abbreviations: MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; MSC, mindful self-compassion; NA, not applicable.

Interventions were led by a master’s-level Japanese licensed clinical psychologist (S.K.) with formal MBSR and MSC training and teaching experience as a Japanese certified instructor. The intervention manual was developed by S.K. A codeveloper of MSC (C.G.) affirmed the quality of the program and manual. The control was a waiting list group. Both groups were allowed to receive usual care as determined by individual patients and their physicians. We instructed participants not to begin dupilumab, psychotherapy, or other mindfulness interventions during the trial so the researchers could accurately evaluate the efficacy of the intervention.

Outcomes

Primary Outcome

We administered the skin disease–specific DLQI at baseline, mid-intervention (week 4), postintervention (week 9), and 4 weeks postintervention follow-up (week 13). The primary outcome was the change in the DLQI score from baseline to week 13. The eAppendix in Supplement 2 provides detailed explanations of the study scales.

Secondary Outcomes

We assessed secondary outcomes at baseline, week 9, and week 13. Secondary outcomes included the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, itchiness-related numeric rating scales (intensity of itchiness before sleep, intensity of scratching, and seriousness of being bothered by itchiness), the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory, the Self-Compassion Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the Internalized Shame Scale (consisting of shame and self-esteem), and dermatologic treatment adherence to self-care measuring a patient’s willingness to follow physician advice. Additionally, participants rated their home practice time and frequency and provided descriptive experiential feedback.

Patient and Family Involvement

Patient and family involvement was highly valued in this trial, and a pragmatic framework was used for authentic patient-researcher partnership in clinical research.36,37 A patient-family advisory council was formed for this trial by selecting members from the pilot study. The council collaborated with researchers from the protocol phase to the interpretation of results. For example, elements of self-compassion were increased, and outcomes were finalized based on patient input. This approach helped assure that participants felt safe and comfortable and would stay in the trial.

Data Collection and Sample Size

Study data were collected using REDCap electronic data capture tools35 hosted at the Department of Medical Biostatics, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University. In a single-arm feasibility and acceptability study (UMIN000036277), participants with a baseline DLQI score of 6 or higher showed a mean (SD) DLQI reduction of 3.7 (6.7). Because the target population was adults with long-lasting AD and we expected minimal change while they were on the waiting list, we set the DLQI score difference to be detected at a mean (SD) of 3.7 (6.7) with a 2-sided α at P < .05 and β at 0.20. The required sample size was 105, and assuming a dropout rate of 10%, the target number of participants was set at 58 in each group, for a total of 116 participants.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted the analyses in accordance with the predefined statistical analysis plan on an intention-to-treat basis. For the primary outcome of the baseline DLQI score change, we used mixed model repeated measures (MMRM) including treatment, time, and time-by-treatment interaction adjusted for age, sex, and baseline DLQI score. We estimated the least-squares means and 95% CIs at each time point for within-group DLQI change scores and differences between groups. Treatment efficacy was judged by the group difference in the primary outcome with a 2-sided α level of P < .05. We applied the same model to the secondary outcomes to explore the intervention effects. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons for secondary outcomes, as they were exploratory in nature.

For the DLQI score, we performed 3 additional prespecified analyses. First, percentages of patients with more than 4-point improvements were estimated for each group and time point with 95% CIs by the Clopper-Pearson method. The minimal clinically important difference of the DLQI score is 4 points.38 Second, heterogeneity in treatment efficacy was assessed for the following predefined subgroups: sex, age (divided by the median values at baseline), and baseline DLQI score (divided by the median values at baseline). Third, group differences were evaluated on a per-protocol basis. All statistical analyses of MMRM used the restricted maximum likelihood methods of SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) with a Kenward-Roger correction and an unstructured variance-covariance matrix.39

Results

Participants

Figure 1 displays the CONSORT diagram for the trial. Among 1053 participants assessed for eligibility, 107 were ultimately included and randomized. Recruitment took place between July 2019 and June 2022, and assessment was conducted until October 2022. Of the 107 randomized adults, 2 (1.9%) dropped out from the primary outcome assessment at week 13. As dropout was negligible, recruitment was halted at 107 participants without considering the 10% dropout anticipated in the protocol. Of the 56 participants allocated to the intervention group, 1 (1.8%) attended only 4 sessions and 55 (98.2%) attended 6 or more of the 8 sessions. Among all participants, 105 (98.1%) completed the assessment at 13 weeks, and all were included in the primary intention-to-treat analysis using MMRM. Several new drugs were introduced to the market after the study began, but only 2 participants from the mindfulness and self-compassion group used topical delgocitinib, and 1 participant from the waiting list group used baricitinib.

Table 2 summarizes the participant characteristics at baseline. Among the 107 participants, 3 lived outside Japan (in Belgium, Singapore, and Spain). Participants were mainly aged 30 to 49 years (mean [SD] age, 36.3 [10.5] years), 85 (79.4%) were female, 22 (20.6%) were male, and most were college graduates (63 [58.9%]). Participants experienced AD for over 2 decades (mean [SD] AD duration, 26.6 [11.7] years), and 80 (74.8%) were attending outpatient dermatology clinics.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Groupa.

| Characteristic | Mindfulness and self-compassion group (n = 56) | Waiting list group (n = 51) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 37.2 (10.4) | 35.2 (10.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 46 (82.1) | 39 (76.5) |

| Male | 10 (17.9) | 12 (23.5) |

| Educational levelb | ||

| High school or lower | 8 (14.3) | 3 (5.9) |

| Some college or vocational school | 9 (16.1) | 6 (11.8) |

| College graduate | 35 (62.5) | 28 (54.9) |

| Graduate school | 4 (7.1) | 14 (27.5) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single, never married | 31 (55.4) | 27 (52.9) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 0 | 1 (2.0) |

| Married | 25 (44.6) | 23 (45.1) |

| Living situation | ||

| By oneself | 12 (21.4) | 10 (19.6) |

| With someone | 44 (78.6) | 41 (80.4) |

| Work situationc | ||

| Full time | 26 (51.0) | 26 (57.8) |

| Part time | 15 (29.4) | 7 (15.6) |

| Medical leave | 0 | 6 (13.3) |

| Homemaker | 0 | 0 |

| Student | 5 (9.8) | 6 (13.3) |

| Unemployed | 5 (9.8) | 0 |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), y | 27.6 (12.0) | 25.5 (11.3) |

| Outpatient clinic visitb | ||

| Any | 41 (73.2) | 39 (76.5) |

| Monthly or more | 9 (22.0) | 12 (30.8) |

| Up to once in 3 mo | 21 (51.2) | 21 (53.8) |

| Up to once in 6 mo | 4 (9.8) | 4 (10.3) |

| Less than once in 6 mo | 2 (4.9) | 2 (5.1) |

| Infrequently | 5 (12.2) | 0 |

| Dermatologic treatmentd | ||

| Moisturizer | 43 (76.8) | 39 (76.5) |

| Topical steroid | 36 (64.3) | 31 (60.8) |

| Tacrolimus ointment | 19 (33.9) | 13 (25.5) |

| Antiallergic oral medicatione | 31 (55.4) | 27 (52.9) |

| Cyclosporinef | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.9) |

| Oral steroid | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.8) |

| Phototherapy | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.9) |

Data are reported as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

Question with missing data.

Participants could select multiple treatments.

Anti-itch medication.

Immunosuppressant.

Primary Outcome and Sensitivity Analyses

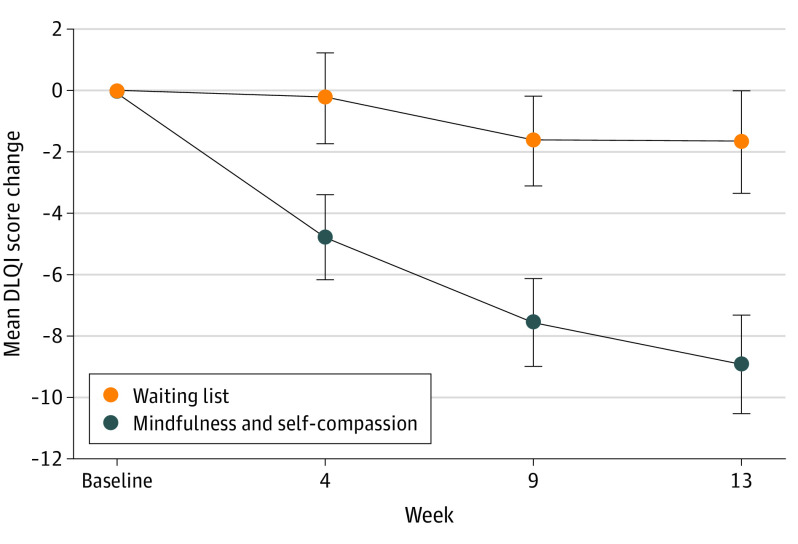

The primary outcome intention-to-treat analysis at 13 weeks showed that the intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvement in DLQI score than the control group (between-group difference estimate, −6.34; 95% CI, −8.27 to −4.41; P < .001). The QOL of the intervention group continued to improve through the intervention and thereafter for up to week 13 (Figure 2). The standardized effect size (Cohen d) at week 13 was −1.06 (95% CI, −1.39 to −0.74) (Table 3).

Figure 2. Changes in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) From Baseline Over Time by Treatment Group.

Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Trial Outcomes by Group.

| Outcome, time point | Mindfulness and self-compassion group | Waiting list group | Difference in LS mean change estimates (95% CI) | P value | Standardized effect size (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, No. | LS mean estimate (95% CI) | Participants, No. | LS mean estimate (95% CI) | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| DLQI score | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 14.75 (13.24 to 16.26) | 51 | 12.75 (11.16 to 14.33) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 4 wk | 55 | 10.02 (8.51 to 11.52) | 51 | 12.51 (10.93 to 14.09) | −3.61 (−5.43 to −1.80) | <.001 | −0.70 (−1.05 to −0.35) | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 7.24 (5.91 to 8.57) | 51 | 11.10 (9.71 to 12.49) | −4.98 (−6.66 to −3.30) | <.001 | −0.95 (−1.27 to −0.63) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 5.89 (4.46 to 7.31) | 51 | 11.10 (9.62 to 12.58) | −6.34 (−8.27 to −4.41) | <.001 | −1.06 (−1.39 to −0.74) | |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| POEM scoreb | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 18.14 (16.65 to 19.64) | 51 | 17.51 (15.94 to 19.08) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 11.58 (9.95 to 13.20) | 51 | 16.37 (14.68 to 18.06) | −5.33 (−7.44 to −3.22) | <.001 | −0.86 (−1.20 to −0.52) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 10.64 (8.94 to 12.35) | 51 | 16.39 (14.63 to 18.16) | −6.28 (−8.54 to −4.01) | <.001 | −0.95 (−1.30 to −0.61) | |

| Intensity of itching before sleep | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 5.27 (4.62 to 5.92) | 51 | 5.54 (4.85 to 6.22) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 3.02 (2.35 to 3.68) | 51 | 4.62 (3.93 to 5.31) | −1.49 (−2.34 to −0.64) | <.001 | −0.60 (−0.94 to −0.26) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 2.47 (1.83 to 3.12) | 51 | 4.72 (4.06 to 5.38) | −2.12 (−2.99 to −1.26) | <.001 | −0.80 (−1.13 to −0.48) | |

| Intensity of scratching | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 5.71 (5.10 to 6.31) | 51 | 5.93 (5.30 to 6.57) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 3.21 (2.60 to 3.82) | 51 | 5.34 (4.71 to 5.98) | −2.01 (−2.76 to −1.25) | <.001 | −0.92 (−1.27 to −0.58) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 3.14 (2.48 to 3.79) | 51 | 5.11 (4.43 to 5.78) | −1.84 (−2.70 to −0.98) | <.001 | −0.73 (−1.07 to −0.39) | |

| Itch bothersomeness | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 5.11 (4.48 to 5.74) | 51 | 5.04 (4.38 to 5.69) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 | 54 | 2.50 (1.90 to 3.10) | 51 | 4.48 (3.85 to 5.10) | −2.06 (−2.82 to −1.30) | <.001 | −0.86 (−1.18 to −0.54) | |

| 13 | 54 | 2.41 (1.77 to 3.06) | 51 | 4.49 (3.83 to 5.15) | −2.16 (−3.04 to −1.28) | <.001 | −0.79 (−1.12 to −0.47) | |

| Self-Compassion Scale | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 2.55 (2.38 to 2.72) | 51 | 2.52 (2.34 to 2.70) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 | 54 | 3.62 (3.46 to 3.78) | 51 | 2.70 (2.54 to 2.87) | 0.91 (0.71 to 1.10) | <.001 | 1.58 (1.24 to1.91) | |

| 13 | 54 | 3.70 (3.53 to 3.86) | 51 | 2.68 (2.55 to 2.85) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.21) | <.001 | 1.52 (1.20 to 1.85) | |

| Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 29.64 (27.75 to 31.54) | 51 | 30.96 (28.97 to 32.95) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 38.98 (37.10 to 40.85) | 51 | 31.00 (29.05 to 32.95) | 8.91 (6.72 to 11.10) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.06 to 1.75) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 39.06 (37.18 to 40.94) | 51 | 31.55 (29.60 to 33.49) | 8.42 (6.08 to 10.76) | <.001 | 1.22 (0.88 to 1.56) | |

| HADS anxiety | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 8.30 (7.19 to 9.41) | 51 | 8.12 (6.96 to 9.28) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 5.76 (4.80 to 6.72) | 51 | 8.78 (7.79 to 9.78) | −3.08 (−4.34 to −1.83) | <.001 | −0.76 (−1.06 to −0.45) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 4.61 (3.55 to 5.66) | 51 | 8.16 (7.07 to 9.24) | −3.62 (−5.00 to −2.24) | <.001 | −0.86 (−1.19 to −0.53) | |

| HADS depression | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 8.29 (7.33 to 9.24) | 51 | 8.31 (7.32 to 9.31) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 4.91 (3.99 to 5.84) | 51 | 7.92 (6.96 to 8.88) | −2.98 (−4.12 to −1.84) | <.001 | −0.85 (−1.18 to −0.53) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 4.69 (3.68 to 5.70) | 51 | 7.69 (6.65 to 8.72) | −2.97 (−4.26 to −1.68) | <.001 | −0.78 (−1.12 to −0.44) | |

| ISS shame | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 47.89 (43.59 to 52.20) | 51 | 51.29 (46.78 to 55.81) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 33.29 (29.16 to 37.42) | 51 | 49.65 (45.34 to 53.96) | −13.76 (−18.03 to −9.48) | <.001 | −1.12 (−1.47 to −0.77) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 31.27 (27.01 to 35.54) | 51 | 49.22 (44.79 to 53.64) | −15.33 (−20.07 to −10.60) | <.001 | −1.13 (−1.47 to −0.78) | |

| ISS self-esteem | ||||||||

| Baseline | 56 | 12.16 (11.01 to 13.31) | 51 | 11.53 (10.32 to 12.74) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 9 wk | 54 | 14.66 (13.50 to 15.82) | 51 | 11.73 (10.52 to 12.93) | 2.46 (1.48 to 3.44) | <.001 | 0.93 (0.56 to 1.30) | |

| 13 wk | 54 | 15.47 (14.26 to 16.69) | 51 | 11.88 (10.62 to 13.15) | 3.12 (1.96 to 4.27) | <.001 | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.40) | |

Abbreviations: DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ISS, Internalized Shame Scale; LS, least-squares; NA, not applicable; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

Cohen d.

The POEM score indicates atopic dermatitis severity.

The percentage of participants showing a minimal clinically important difference in the DLQI score at 13 weeks was 81.5% (95% CI, 68.6%-90.7%) in the mindfulness and self-compassion group and 33.3% (95% CI, 20.8%-47.9%) in the waiting list group (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). No treatment effect heterogeneity among subgroups was confirmed (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 2). The group differences in the per-protocol population were consistent with those of the full analysis set (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Secondary Outcomes

The intention-to-treat analysis showed that all secondary outcomes, including AD symptoms, itch- and scratching-related visual analog scales, self-compassion and all of its subscales (eTable 5 in Supplement 2), mindfulness, internalized shame, anxiety, and depression, showed significant improvement with large effect sizes in the mindfulness and self-compassion group compared with the waiting list group at all time points (Table 3 and eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Dermatologic treatment adherence showed that those in the mindfulness and self-compassion group were more likely to follow medical treatment plans by dermatologists from baseline to week 13, including moisturizer use and topical steroid use (eFigures 2 and 3 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Comments from participants suggested that their feeling of resistance or worry about use of medications decreased, and they applied them early, mindfully, and compassionately rather than automatically.

The majority of participants in the mindfulness and self-compassion group reported that they completed home practice either every day or every other day. The mean (SD) duration of home practice per day was 43.5 (17.1) minutes at week 4, 41.7 (22.2) minutes at week 9, and 32.9 (17.9) minutes at week 13 (eTables 7 and 8 in Supplement 2).

Serious Adverse Events

One serious adverse event was identified. One participant had been diagnosed with uterine fibroids and had undergone surgery prior to her enrollment. Her results came back after starting the program, and early-stage endometrial cancer was diagnosed. Subsequently she underwent surgery and recovered well. We judged this event to be unrelated to the intervention. With approval from the ethics committee at Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, the participant continued to participate in the study.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated the efficacy of integrated online mindfulness and self-compassion for adults with moderate to severe AD. We found that skin disease–specific QOL improved over time with a large effect size. The dropout rate was low.

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to show that group-format mindfulness and self-compassion enhances the QOL for adults with AD. A previous systematic review reported that MBSR had a moderate effect size for QOL for a range of target populations but recommended further research to ensure quality of evidence.40 People with AD experience chronic symptoms, and integrating self-compassion may have contributed to the observed large effect of the intervention. Improved QOL in the present study may also have been due to improved physical well-being.

The study confirmed that mindfulness and self-compassion reduced patient-reported AD symptoms. The mindfulness and self-compassion intervention combined with usual care enabled physiological symptoms to improve. Of importance, participants in the mindfulness and self-compassion group had improved dermatologic treatment adherence. This likely contributed to improved physiological responses. Additionally, multiple psychological and biological factors appeared interconnected. For example, the present findings support previous work that demonstrated that mindfulness meditation was associated with an improved immunological response41 and that self-soothing touch reduces cortisol levels.42

Prior studies reported an association of habit training with improved itch-scratch cycle.43,44,45,46 Patients with AD are often in pain, managing difficult symptoms, and experiencing unnecessary distress due to self-judgment and self-criticism. When an itch arises, mindfulness and self-compassion teaches patients to see that there is a choice to respond mindfully: scratch, apply soothing touch, or simply let go. When one scratches, self-compassion teaches that there is no need for self-blame. There is instead a choice to direct compassion, understanding, and self-care to their skin and themselves. These skills seemed to help break a negative cycle. However, teaching these skills requires extensive training.

The program in the present study was developed and taught by an experienced Japanese licensed clinical psychologist (S.K.) who has a history of AD. The present findings support existing effect sizes in self-compassion, depression, and anxiety with MSC.29 Based on participant comments, the topic of the week 8 session, being with shame kindly, was a highlight, as self-compassion is an antidote to shame. An example of a common participant comment was “I thought me without AD should be the real me, but it’s ok to have AD, ok to be imperfect like all humans. Now I have begun to like myself.”

Strengths and Limitations

One of the trial’s strengths is its high internal validity, including independent random sequence generation, allocation concealment, statistician blinding, full reports of the preplanned analyses, and in particular, the low dropout rate. In a general trial of psychotherapy with adults, a 19.7% dropout rate was reported.47 Completion rates of online mindfulness courses vary depending on the population and completion criteria.48 In a recent online MBSR study, only 67.6% completed at least 6 of 8 classes.49 A study on online, compassion-focused self-help therapy for psoriasis reported a dropout rate of 29%.50 Finally, the online format was highly scalable and accessible, including for participants who were hesitant to go outside due to AD symptoms.

The trial also has limitations. First, external validity may not be high. Only highly motivated and committed Japanese participants applied to this study. However, this may indicate urgency surrounding AD treatment, as nearly all included participants were highly motivated to find a treatment that could ease their symptoms. It is not clear what the results would demonstrate with participants who were less motivated, populations in other countries, or different clinical settings. It is possible that many in the Japanese population are well-suited for mindfulness-based approaches or that care delivery for AD in Japan may be associated with greater acceptability of behavioral health approaches. Further research with other populations and clinical settings is necessary to increase generalizability and transportability of the current findings. Also, participants received conventional treatment rather than newly introduced drugs, as the intention was to accurately evaluate the efficacy of mindfulness and self-compassion. In addition, although the difference was not statistically significant, male patients demonstrated less response than female patients, with differences in the point estimates near the magnitude of the DLQI score minimal clinically important difference. Heterogeneity between the sexes needs further investigation to clarify. Second, using participants on a waiting list as a control group may have led to a larger effect size than using another control condition such as no treatment or placebo psychotherapy.51 Third, there was only 1 therapist due to the lack of resources in Japan. To ensure generalizability and scalability and to establish effectiveness, therapists need to be trained adequately so that the intervention's overall effectiveness can be ascertained. Trials using multiple therapists will allow for process research with therapist factors such as treatment fidelity and the therapeutic alliance. Fourth, mindfulness and self-compassion required 12 hours total for 8-week, online, live group-interactive sessions. Further using information and communication technologies may make the intervention more efficient, such as the internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy used by Hedman-Lagerlöf et al.52 Fifth, no objective outcomes were evaluated. In this trial, the focus was on patient-reported outcomes. While combining patient- and clinician-reported outcomes will be needed in future studies, patients who did not see dermatologists but had dermatologic needs were able to participate in this trial. Sixth, in this study, the intention-to-treat principle was adhered to and the effect of assigning participants to the interventions was examined rather than the effect of adhering to the treatments. We understand the importance of a detailed path analysis for the intervention effect, and this will be within the scope of future studies.

Conclusion

In this randomized clinical trial of patients with AD, online mindfulness and self-compassion training in addition to usual care improved QOL, AD symptoms, and psychological well-being. These findings suggest that mindfulness and self-compassion training is an effective treatment option for adults with AD.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Description of Outcomes

eTable 1. Participants With the Minimal Clinically Important Difference on the Dermatology Life Quality Index

eTable 2. Subgroup Analysis for the Dermatology Life Quality Index Changes from Baseline

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis: P for Treatment Effect Heterogeneity Among Subgroups at 13 Weeks

eTable 4. Results of the Per-Protocol Analysis: Primary Outcome Dermatology Life Quality Index

eTable 5. Self-Compassion Scale: Subscale Results

eFigure 1. Least-Square (LS) Mean Changes from Baseline to Week 13

eFigure 2. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Moisturizer by Groups Over Time

eFigure 3. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Topical Steroid by Groups Over Time

eTable 6. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Descriptive Data of All Treatments Between Groups Over Time

eTable 7. Home Practice Records: Frequency

eTable 8. Home Practice Records: The Average Length of the Time per Day (Minutes)

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1483-1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katoh N, Ohya Y, Ikeda M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis 2018. J Dermatol. 2019;46(12):1053-1101. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. ; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group . Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733-743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73(6):1284-1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girolomoni G, Luger T, Nosbaum A, et al. The economic and psychosocial comorbidity burden among adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in Europe: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(1):117-130. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00459-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340-347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942-949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laughter MR, Maymone MBC, Mashayekhi S, et al. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):304-309. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chida Y, Steptoe A, Hirakawa N, Sudo N, Kubo C. The effects of psychological intervention on atopic dermatitis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;144(1):1-9. doi: 10.1159/000101940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavda AC, Webb TL, Thompson AR. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological interventions for adults with skin conditions. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):970-979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ersser SJ, Cowdell F, Latter S, et al. Psychological and educational interventions for atopic eczema in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(1):CD004054. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004054.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melin L, Frederiksen T, Noren P, Swebilius BG. Behavioural treatment of scratching in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(4):467-474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb06241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehlers A, Stangier U, Gieler U. Treatment of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of psychological and dermatological approaches to relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(4):624-635. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.4.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schut C, Weik U, Tews N, Gieler U, Deinzer R, Kupfer J. Psychophysiological effects of stress management in patients with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(1):57-61. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wollenberg A, et al. ; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Neurodermitisschulung für Erwachsene (ARNE) Study Group . Effects of structured patient education in adults with atopic dermatitis: multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):845-853.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Revankar RR, Revankar NR, Balogh EA, Patel HA, Kaplan SG, Feldman SR. Cognitive behavior therapy as dermatological treatment: a narrative review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2022;8(4):e068. doi: 10.1097/JW9.0000000000000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4(1):33-47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8(2):163-190. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, et al. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(7):936-943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradhan EK, Baumgarten M, Langenberg P, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1134-1142. doi: 10.1002/art.23010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sephton SE, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, et al. Mindfulness meditation alleviates depressive symptoms in women with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):77-85. doi: 10.1002/art.22478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Reilly-Spong M, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction versus pharmacotherapy for chronic primary insomnia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Explore (NY). 2011;7(2):76-87. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann M, Kopf S, Kircher C, et al. Sustained effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction intervention in type 2 diabetic patients: design and first results of a randomized controlled trial (the Heidelberger diabetes and stress-study). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):945-947. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakhshani NM, Amirani A, Amirifard H, Shahrakipoor M. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on perceived pain intensity and quality of life in patients with chronic headache. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(4):142-151. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n4p142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson R, Byrne S, Wood K, Mair FS, Mercer SW. Optimising mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2018;14(2):154-166. doi: 10.1177/1742395317715504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrés-Rodríguez L, Borràs X, Feliu-Soler A, et al. Immune-inflammatory pathways and clinical changes in fibromyalgia patients treated with mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:109-119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuyken W, Watkins E, Holden E, et al. How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(11):1105-1112. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Dam NT, Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, Earleywine M. Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(1):123-130. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(1):28-44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friis AM, Johnson MH, Cutfield RG, Consedine NS. Kindness matters: a randomized controlled trial of a mindful self-compassion intervention improves depression, distress, and HbA1c among patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(11):1963-1971. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, et al. Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA). Psychosom Med. 1998;60(5):625-632. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi N, Suzukamo Y, Nakamura M, et al. ; Acne QOL Questionnaire Development Team . Japanese version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index: validity and reliability in patients with acne. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Browning DM, Comeau M, Kishimoto S, et al. Parents and interprofessional learning in pediatrics: integrating personhood and practice. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(2):152-153. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.505351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fagan MB, Morrison CR, Wong C, Carnie MB, Gabbai-Saldate P. Implementing a pragmatic framework for authentic patient-researcher partnerships in clinical research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(3):297-308. doi: 10.2217/cer-2015-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27-33. doi: 10.1159/000365390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53(3):983-997. doi: 10.2307/2533558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Vibe M, Bjørndal A, Fattah S, Dyrdal GM, Halland E, Tanner-Smith EE. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life and social functioning in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2017;13(1):1-264. doi: 10.4073/csr.2017.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Black DS, Slavich GM. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):13-24. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dreisoerner A, Junker NM, Schlotz W, et al. Self-soothing touch and being hugged reduce cortisol responses to stress: a randomized controlled trial on stress, physical touch, and social identity. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021;8:100091. doi: 10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norén P, Hagströmer L, Alimohammadi M, Melin L. The positive effects of habit reversal treatment of scratching in children with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):665-673. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schut C, Mollanazar NK, Kupfer J, Gieler U, Yosipovitch G. Psychological interventions in the treatment of chronic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(2):157-161. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rinaldi G. The itch-scratch cycle: a review of the mechanisms. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9(2):90-97. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0902a03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rafidi B, Kondapi K, Beestrum M, Basra S, Lio P. Psychological therapies and mind-body techniques in the management of dermatologic diseases: a systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(6):755-773. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00714-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swift JK, Greenberg RP. Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(4):547-559. doi: 10.1037/a0028226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Forder L, Jones F. Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(2):118-129. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riley TD, Roy S, Parascando JA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction live online during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods feasibility study. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28(6):497-506. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2021.0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muftin Z, Gilbert P, Thompson AR. A randomized controlled feasibility trial of online compassion-focused self-help for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(6):955-962. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michopoulos I, Furukawa TA, Noma H, et al. Different control conditions can produce different effect estimates in psychotherapy trials for depression. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;132:59-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Fust J, Axelsson E, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(7):796-804. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Description of Outcomes

eTable 1. Participants With the Minimal Clinically Important Difference on the Dermatology Life Quality Index

eTable 2. Subgroup Analysis for the Dermatology Life Quality Index Changes from Baseline

eTable 3. Subgroup Analysis: P for Treatment Effect Heterogeneity Among Subgroups at 13 Weeks

eTable 4. Results of the Per-Protocol Analysis: Primary Outcome Dermatology Life Quality Index

eTable 5. Self-Compassion Scale: Subscale Results

eFigure 1. Least-Square (LS) Mean Changes from Baseline to Week 13

eFigure 2. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Moisturizer by Groups Over Time

eFigure 3. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Topical Steroid by Groups Over Time

eTable 6. Dermatological Treatment Adherence for Self-Care: Descriptive Data of All Treatments Between Groups Over Time

eTable 7. Home Practice Records: Frequency

eTable 8. Home Practice Records: The Average Length of the Time per Day (Minutes)

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement