Abstract

Epidemiologic and experimental data provide evidence that a critical level of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to the surface polysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 (lipopolysaccharide) and of Vibrio cholerae O139 (capsular polysaccharide [CPS]) is associated with immunity to the homologous pathogen. The immunogenicity of polysaccharides, especially in infants, may be enhanced by their covalent attachment to proteins (conjugates). Two synthetic schemes, involving 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and 1-cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridinium tetrafluoroborate (CDAP) as activating agents, were adapted to prepare four conjugates of V. cholerae O139 CPS with the recombinant diphtheria toxin mutant, CRMH21G. Adipic acid dihydrazide was used as a linker. When injected subcutaneously into young outbred mice by a clinically relevant dose and schedule, these conjugates elicited serum CPS antibodies of the IgG and IgM classes with vibriocidal activity to strains of capsulated V. cholerae O139. Treatment of these sera with 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) reduced, but did not eliminate, their vibriocidal activity. These results indicate that the conjugates elicited IgG with vibriocidal activity. Conjugates also elicited high levels of serum diphtheria toxin IgG. Convalescent sera from 20 cholera patients infected with V. cholerae O139 had vibriocidal titers ranging from 100 to 3,200: absorption with the CPS reduced the vibriocidal titer of all sera to ≤50. Treatment with 2-ME reduced the titers of 17 of 20 patients to ≤50. These data show that, like infection with V. cholerae O1, infection with V. cholerae O139 induces vibriocidal antibodies specific to the surface polysaccharide of this bacterium (CPS) that are mostly of IgM class. Based on these data, clinical trials with the V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with recombinant diphtheria toxin are planned.

It has been proposed that a critical level of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) to the surface polysaccharides of Vibrio cholerae O1 and V. cholerae O139 confers serotype-specific immunity to cholera (3, 7, 17, 24, 25, 28, 29–32, 38, 39, 43, 44). The surface polysaccharide of V. cholerae O1 is a lipopolysaccharide (LPS). V. cholerae O139, in contrast, has a capsular polysaccharide (CPS) composed of a hexasaccharide repeating unit containing a trisaccharide backbone and two branches (3, 4, 8, 10, 12, 16, 17, 19, 26, 28, 30, 31, 35, 38, 42, 43, 45). The repeating unit contains two negatively charged groups: a carboxyl of galactouronic acid and a phosphate cyclic diester. In our preliminary studies we found that CPS did not elicit serum antibodies after three injections in mice (Z. Kossaczka and S. C. Szu, submitted for publication). To improve its immunogenicity, CPS was covalently bound by different synthetic schemes to chicken serum albumin, as a model protein. The resultant conjugates induced serum anti-CPS IgG in mice with vibriocidal activity (Kossaczka and Szu, submitted).

We chose the two most successful schemes to prepare V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with the recombinant diphtheria toxin (rDT) mutant CRMH21G. CRMH21G was prepared by replacing histidine 21 with glycine in the A chain of DT (15). This mutant protein has a 10−4 lower toxicity than DT and is suitable for clinical use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH), 1-cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridinium tetrafluoroborate (CDAP), and agarose were from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.; Sepharose CL-4B and Sephadex G-25 were from Pharmacia AB, Uppsala, Sweden; bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard solution, Coomassie blue protein assay reagent, and triethylamine (TEA) were from Pierce, Rockford, Ill.; nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) chelating agarose was from Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.; acetonitrile was from T. J. Baker, Inc., Philipsburg, N.J.; DT was from List Biological Laboratories, Inc., Campbell, Calif.; equine anti-DT serum from lot 152-5456 R was a gift from the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; rabbit (3 to 4 weeks old) complement was from Pel-Freeze, Brown Deer, Wis.; dialysis membranes (molecular weight cutoff, 6,000 to 8,000) were from Spectra-Por, Laguna Hills, Calif.; ultrafiltration membrane YM100 and Centriprep 30 were from Amicon, Inc., Beverly, Mass.; Limulus amebocyte lysate pyrogen (U.S. license no. 709) was from BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, Md.; tryptic soy broth (TSB) was from Difco Inc., Detroit, Mich. (TSB containing 1% agarose was denoted as TSA). Deionized or pyrogen-free water (PFW) and pyrogen-free saline (PFS) were used in all experiments.

Bacteria.

V. cholerae O139 MDO-12C (8), a heavily capsulated and opaque variant selected from the isolate MDO-12 (Madurai, India), was used for the preparation of CPS and murine hyperimmune serum. V. cholerae O139 SPH1168, a clinical isolate from a Thai patient (Suanphung Hospital, Suanphung, Thailand) (13), was used as the target strain in the vibriocidal assay. Both isolates were stored in 20% glycerol at −70°C.

Purification of V. cholerae O139 CPS.

V. cholerae O139 MDO-12C was propagated from a single colony on TSA to 400 ml and then to 4 liters of TSB for 5 h at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The 4-liter inoculum (A560 ∼ 3.0) was transferred to a 300-liter fermentor containing 150 liters of TSB, 0.1% dextrose, and 0.05 M MgSO4. Fermentation was conducted in 30% dissolved oxygen at 35°C and pH 7.0 (maintained with NH4OH). After 16 h, formalin was added to a final concentration of 2%, and the mixture was stirred slowly for 6 h at room temperature. The suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant concentrated to 1.2 liters by ultrafiltration and stored at −20°C.

A 500-ml aliquot of the concentrated supernatant was mixed with 3 volumes of 95% ethanol and stored overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted, and the slurry was spun down at 10,500 × g at 10°C for 30 min. The pellet (20 g [wet weight]) was washed with 80% ethanol, dissolved in 800 ml of 10% saturated sodium acetate (pH 7.5), and extracted with cold phenol three times (9). The final water phase was dialyzed against H2O for 3 days at 4 to 8°C and freeze-dried. The precipitate was dissolved in 150 ml of 0.1 M CaCl2 and ultracentrifuged at 145,000 × g at 10°C for 5 h. The supernatant was recentrifuged as described above, dialyzed against H2O, freeze-dried (yield, 1.6 g), and stored at −20°C.

This material (unfractionated CPS) was dissolved in PFW (100 mg/50 ml) and passed through an Amicon membrane YM100. The retentate was passed through a 2.5-by-90-cm column of Sepharose CL-4B in PFS. The retentate was eluted from the column as one peak at Kd 0.4: fractions were pooled, dialyzed against PFW, and freeze-dried. This material was denoted CPS and used to prepare conjugates with rDT.

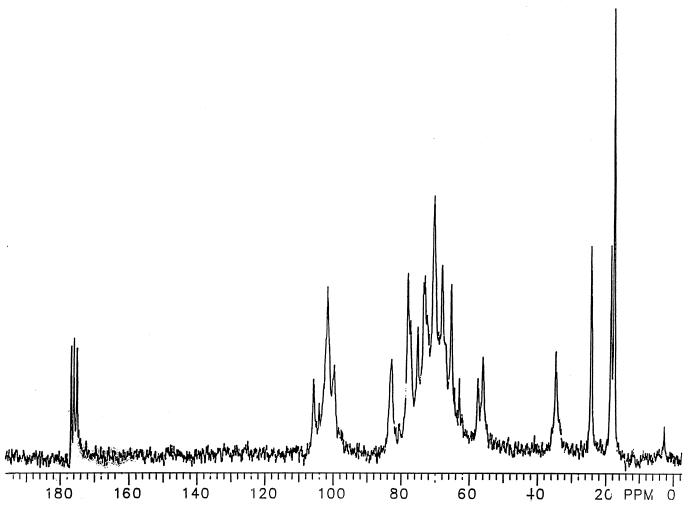

13C NMR spectroscopy.

The 13C NMR spectrum of the CPS (50 mg/ml of D2O) was measured using a Varian XL3000 spectrometer by averaging 50,000 scans with a 10-s decay between acquisition and a 10-μs 90° pulse. Prior to Fourier transformation, a 5-Hz line broadening was applied and zero filled to 32,000 datum points.

Murine hyperimmune V. cholerae O139 serum.

V. cholerae O139 culture was prepared by transferring a single colony from TSA to 50 ml of LB and incubating it at 37°C at 200 rpm for 5 h (A560 ∼1.0). The culture was inactivated with 1% formalin. Thirty 6-week-old female Swiss mice (National Institutes of Health) were injected as follows: (i) three subcutaneous injections of 100 μl 1 day apart; (ii) after 9 days, 3 intraperitoneal injections of 150 μl 1 day apart; and (iii) 9 days later, three intravenous injections of 200 μl 1 day apart. Mice were exsanguinated 7 days after the last injection. All sera showed a precipitin line by double immunodiffusion with CPS: a pool was denoted as murine hyperimmune V. cholerae O139 serum.

Purification of rDT mutant CRMH21G.

The rDT mutant was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis on the A chain, replacing histidine at position 21 with glycine, and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(λDE3) (15). To facilitate purification by use of Ni-NTA, a six-histidine tag was attached to the protein carboxyl terminal. Fermentation of this recombinant strain was performed as described previously (5). The cell paste was suspended in 0.5 M NaCl–0.02 M Tris–0.005 M imidazole (pH 8.0), and the cytoplasm was released by a French press. The supernatant was passed through a 2.5-by-10-cm Ni-NTA column and washed with 0.02 M Tris buffer containing 0.03 M imidazole (pH 8.0). rDT was eluted with 0.02 M Tris buffer containing 0.25 M imidazole (pH 8.0) at 3 to 8°C. The eluate was dialyzed exhaustively against 0.02 M Tris (pH 8.0) at 3 to 8°C (yield, 150 mg of rDT/liter of supernatant). Prior to derivatization, rDT was dialyzed at 3 to 8°C against phosphate-buffered saline with multiple changes of outer fluid, followed by dialysis against 0.2 M NaCl (pH 7.2 to 7.7; adjusted with 1 M NaOH). The protein solution was concentrated to ∼10 mg/ml in an Amicon Centriprep 30.

rDT had the same Rf by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in a 10% polyacrylamide gel and the same circular dichroism spectrum as DT (not shown). A line of identity was formed between rDT and DT when they were reacted against equine anti-DT serum by double immunodiffusion (not shown).

Adipic acid hydrazide (AH) derivatives.

CPS and rDT were treated with ADH in the presence of CDAP (20, 21, 23) and EDC (22, 37), respectively, as activating agents.

AH derivative of CPS (CPSAH).

CDAP activation of CPS was performed as described earlier (21) using a CDAP/CPS ratio of 1:5 (wt/wt). A total of 40 mg of CPS was dissolved in 1.5 ml of H2O (pH 5.0). Then, 80 μl of CDAP in acetonitrile (100 mg/ml) was added, followed in 30 s by adding 80 μl of 0.2 M TEA. After 2 min, the pH was adjusted to 7.8 with 0.1 M HCl. Then, 1.5 ml of 0.8 M ADH in 0.5 M NaHCO3 was added, and the pH was maintained between 8.0 and 8.4 with 0.1 M HCl for 2 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was dialyzed overnight against 6 liters of water with two changes and then passed through a 2.5-by-40-cm column of Sephadex G-25 in PFW. The void volume fractions, denoted CPSAH, were freeze-dried and assayed for AH.

AH derivative of rDT (rDTAH).

The reaction mixture contained 10 mg of protein per ml, 0.2 M ADH, and 0.011 M EDC. The reaction was carried out for 1 h at room temperature, with the pH maintained at 6.2 to 6.4 with 0.1 M HCl. The reaction mixture was dialyzed against 0.2 M NaCl (pH 7.0; adjusted with 1 M NaOH) and passed through a 1.5-by-25-cm column of Sephadex G-25 in the same solution. Void volume fractions, denoted rDTAH, were pooled, concentrated (Amicon Centriprep 30), and assayed for protein and AH.

Conjugates.

Two schemes were used to prepare conjugates: EDC-mediated conjugation of the CPSAH with rDT and CDAP-mediated conjugation of the CPS with rDTAH.

(i) EDC-mediated conjugation of CPSAH with rDT.

Each reaction mixture contained 8 mg of CPSAH and rDT per ml and EDC at 0.05 M (for I:CPSAH-rDT) or 0.02 M (for II:CPSAH-rDT).

CPSAH was dissolved in 0.2 M NaCl, and the pH was adjusted to 6.2 with 0.1 M NaOH. rDT was added, and the volume was adjusted with 0.2 M NaCl. After stirring the mixture for 1 min, the EDC was added. The reaction was carried out for 3 h at room temperature, and the pH was maintained at 6.2 to 6.4 with 0.1 M HCl. The mixture was dialyzed overnight at 3 to 8°C against 0.2 M NaCl–0.005 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and passed through a 1.5-by-90-cm column of Sepharose CL-4B in the same buffer. Fractions were assayed for polysaccharide and protein. The void volume fractions were pooled and denoted I:CPSAH-rDT and II:CPSAH-rDT.

(ii) CDAP-mediated conjugation of CPS with rDTAH.

Each reaction mixture contained 8 mg of CPS and rDTAH per ml: the CDAP/CPS ratio was 4:5 (for I:CPS-rDTAH) or 1:5 (for II:CPS-rDTAH).

CDAP (100 mg/ml of acetonitrile) was added to CPS in 0.2 M NaCl (pH 5.2) and mixed for 30 s. A volume of 0.2 M TEA equal to that of CDAP was added. After 2 min, the pH dropped from 8.5 to 7.2 and rDTAH was added. The pH was raised from 7.2 to 8.3 with 0.1 M NaOH. The reaction was carried out for 2 h at room temperature, during which the pH was stable. The mixture was dialyzed overnight against 0.2 M NaCl–0.005 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and passed through a 1.5-by-90-cm column of Sepharose CL-4B in the same buffer. Fractions were assayed for polysaccharide and protein, and void volume fractions were pooled and denoted I:CPS-rDTAH and II:CPS-rDTAH.

Chemical assays.

Polysaccharide was assayed by measuring 3,6-dideoxyhexose (colitose) with the CPS as the standard (18). Protein was measured by Coomassie blue assay with BSA as the standard (2). The hydrazide content of CPSAH and rDTAH was measured by the TNBS method using ADH as the standard (14). The degree of derivatization was expressed as a percentage of AH and the mole/mole ratio of AH to polysaccharide or to protein.

Limulus amebocyte lysate test.

CPS was assayed for endotoxin by limulus amebocyte lysate test. The FDA Reference Standard Endotoxin (lot EC-5) was used as a reference for the assay. The test conforms with the Food and Drug Administration guideline (41).

Immunodiffusion.

Double immunodiffusion of the conjugates was performed in 1% agarose gel in 0.15 M NaCl with murine hyperimmune cholera O139 serum and equine DT antiserum.

Immunization of mice.

Six-week-old female Swiss albino mice (10 per group) were injected subcutaneously three times at 2-week intervals with 100 μl of immunogen containing 2.5 μg of the CPS alone or as the conjugate. A control group received one injection of 100 μl of saline. Mice were exsanguinated 7 days after each injection, and sera were stored at −20°C.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc-Immuno) were coated with CPS (20 μg/ml of PBS) and kept overnight at room temperature. After a washing with 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1% Brij, and 3 mM sodium azide, plates were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were washed and twofold serial dilutions of sera in 1% BSA–0.1% Brij–PBS were added. Reference serum was assayed in triplicates and samples in duplicates. Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature and washed, and the alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat antibody specific to mouse IgG or IgM was added. After 4 h at room temperature, the plates were washed, and the 4-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (1 mg/ml in 1 M Tris-HCl–3 mM MgCl2 [pH 9.8]) was added. A405 was measured by using an MRX Dynatech reader.

Anti-CPS IgG was measured in all murine sera; anti-CPS IgM was measured only in 11 representative sera from mice injected three times with II:CPSAH-rDT or I:CPS-rDTAH. Murine hyperimmune V. cholerae O139 serum was used as the reference for both anti-CPS IgG and IgM. This serum was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1,000 ELISA units (EU)/ml for IgG and 100 EU/ml for IgM upon the observation that a 1/20,000 dilution of anti-IgG and a 1/100 dilution of anti-IgM gave approximately the same A405.

An analogous ELISA procedure was used to measure anti-DT IgG: plates were coated with DT (5 μg/ml), and a mouse serum with a high titer of anti-DT IgG was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1,000 EU served as the reference.

ELISA results were computed with an ELISA data processing program provided by the Biostatistics and Information Management Branch, Centers for Disease Control, based upon four parameters of logistic-log function using the Taylor Series Linearization Algorithm (34). Anti-CPS IgG and anti-DT IgG levels are expressed as geometric means.

Statistics.

Comparisons of the geometric means were performed with the two-sided Student t test or Wilcoxon analysis.

Vibriocidal assay.

Eleven representative sera from mice injected three times with II:CPSAH-rDT or I:CPS-rDTAH, and twenty convalescent sera from cholera patients infected with V. cholerae O139 (Samutskakorn Hospital, Samutskakorn, Thailand [13]) were assayed for vibriocidal activity before and after treatment with 0.1 M 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) for 30 min at 37°C (10, 27). The patient sera were also tested for vibriocidal activity after absorption with CPS in a vibriocidal antibody inhibition (VAI) assay (6).

Bacteria were prepared by transferring a single colony from TSA into 10 ml of TSB and incubating them for 2 to 3 h at 37°C with shaking at 180 rpm. Then, 100 μl of this inoculum was transferred to 10 ml of TSB and incubated with shaking (180 rpm) at 37°C until the culture reached an A560 of 0.2 to 0.24 (3.0 × 107 to 4.0 × 107 cells/ml). The bacterial suspension was diluted 105-fold in Dulbecco buffer.

VAI assay was performed in sterile nonpyrogenic 24-well cell culture plates (Costar, Corning, N.Y.) by mixing equal volumes of serum, bacteria, and complement. The tested serum was twofold serially diluted in Dulbecco buffer (for VAI assay in 100 mg of CPS/ml of Dulbecco buffer), so that each well contained 100 μl. Next, 100-μl aliquots of the bacteria and of complement were added into each well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with shaking. Two 100-μl aliquots from each well were transferred into empty wells, and 1 ml of TSA (46 to 48°C) was added to all three wells. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the colonies were counted. The vibriocidal titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution showing ≥60% reduction in the number of colonies compared to the control (complement only) (25).

RESULTS

V. cholerae O139 CPS.

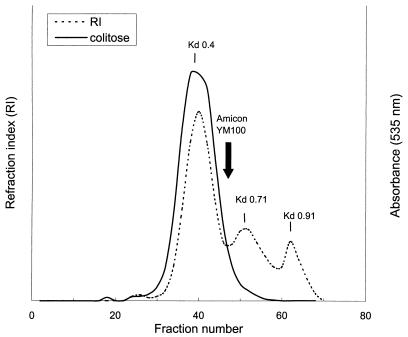

The V. cholerae O139 CPS isolated from culture supernatant (see Materials and Methods) showed three peaks at Kds of 0.4, 0.71, and 0.91 on Sepharose CL-4B with yields of 70, 29, and 1%, respectively (Fig. 1). Colitose, a component of the CPS repeating unit, was detected only in the peak at Kd 0.4. Fast separation of this peak material from the lower-molecular-weight materials (Kds 0.71 and 0.91) was accomplished by diafiltration of the unfractionated CPS through an Amicon ultrafiltration membrane (YM100). To confirm its purity, the retentate was passed through Sepharose CL-4B and only showed a peak of Kd 0.4. The 13C NMR spectrum of the retentate (equivalent to the peak-material of Kd 0.4) (Fig. 2) was identical to a published 13C NMR spectrum of V. cholerae O139 CPS (19, 35). The filtrate spectrum, in contrast, lacked chemical shifts for colitose, quinovosamine, GluNAc, and d-galactouronic acid (not shown). The retentate gave strong reaction with the murine V. cholerae O139 hyperimmune serum by Western blot and double immunodiffusion (not shown). The retentate, denoted CPS, showed only <0.5 endotoxin units/μg as measured by the Limulus amebocyte lysate test.

FIG. 1.

Sepharose CL-4B gel filtration profile of the unfractionated V. cholerae O139 CPS. The refractive index response is indicated by a broken line; the colitose-containing fractions are indicated by a solid line. A point of separation between the retentate and the filtrate by diafiltration (Amicon YM100) of the unfractionated CPS (arrow) is also noted. Distribution coefficients (Kd) are depicted at the top of each peak.

FIG. 2.

13C NMR spectrum of V. cholerae O139 CPS. The 13C NMR spectrum of the CPS (50 mg/ml of D2O) was measured using a Varian XL3000 spectrometer by averaging 50,000 scans with a 10-s decay between acquisition and a 10-μs 90° pulse. Prior to Fourier transformation, a 5-Hz line broadening was applied and zero filled to 32,000 datum points.

AH derivatives of CPS (CPSAH) and of rDT (rDTAH).

CPSAH contained 3.4% of AH, which represents ∼1 AH per five CPS-repeating units (Table 1). CPSAH and CPS formed a line of identity when reacted with murine hyperimmune V. cholerae O139 serum by double immunodiffusion (not shown).

TABLE 1.

ADH derivatives (AH) of V. cholerae O139 CPS and of rDT

| Derivative | Activating agent | AH content

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % | mol/mola | ||

| CPSAH | CDAP | 3.44 | 0.21 |

| rDTAH | EDC | 1.90 | 7.12 |

CPS repeating unit, Mr 1,053; rDT, Mr ∼67,000.

rDTAH contained 7.2 mol of AH per mol of protein and formed a line of identity with rDT when reacted with equine DT antiserum by double immunodiffusion (not shown).

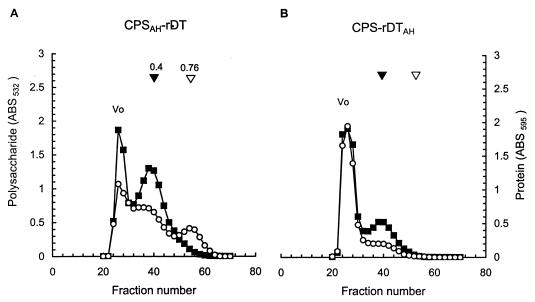

Conjugates. (i) EDC-mediated synthesis of CPSAH-rDT conjugates.

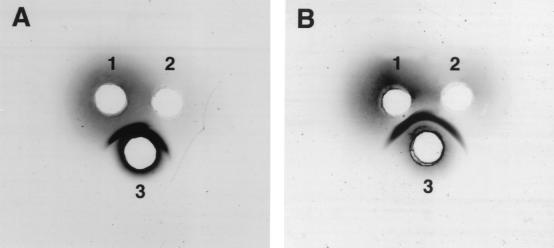

Identical reaction conditions, except for the concentration of EDC, were used to prepare I:CPSAH-rDT (0.05 M EDC) and II:CPSAH-rDT (0.02 M EDC). Gel filtration of either conjugate on Sepharose CL-4B yielded three peaks at V0, Kd 0.4, and Kd 0.76 (Fig. 3A). Two peaks, at V0 and Kd 0.4, consisted of both polysaccharide and protein, while the peak at Kd 0.76 contained only protein. Since the Kds of the free CPS and rDT on Sepharose CL-4B are 0.4 and 0.76, respectively, the presence of unreacted CPS and/or rDT within the range of Kd 0.4 to 0.76 could not be excluded (Table 2). Accordingly, only the void volume fractions were pooled and are denoted I:CPSAH-rDT and II:CPSAH-rDT. I:CPSAH-rDT had a lower polysaccharide/protein (wt/wt) ratio than did II:CPSAH-rDT (0.46 < 0.76). The yields of both conjugates were about 20% based upon the recovery of polysaccharide. Double immunodiffusion of either conjugate against murine V. cholerae O139 and equine DT toxin hyperimmune sera showed a single precipitin line (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 3.

Sepharose CL-4B gel filtration profiles of V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with rDT. A representative chromatograph of the CPSAH-rDT conjugates prepared by EDC-mediated synthesis (A) or of CPS-rDTAH conjugates prepared by CDAP-mediated synthesis (B) is shown. Symbols: ■, polysaccharide; ○, protein; ▾, Kd of CPS; ▿, Kd of rDT.

TABLE 2.

Composition of V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with rDT

| Conjugate | Conjugation method | PS/PR ratio (wt/wt) | % Yielda |

|---|---|---|---|

| I:CPSAH-rDT | EDC (0.05 M) | 0.46 | 28.0 |

| II:CPSAH-rDT | EDC (0.02 M) | 0.78 | 20.1 |

| I:CPS-rDTAH | CDAP-CPS (4:5) | 0.90 | 45.0 |

| II:CPS-rDTAH | CDAP-CPS (1:5) | 0.99 | – |

Yield was determined based on the amount of polysaccharide in the conjugate. –, the accidental loss of some material prevented accurate determination of the yield.

FIG. 4.

Double immunodiffusion of V. cholerae O139 conjugates with murine hyperimmune cholera O139 and equine DT antisera. (A) Representative pattern for CPSAH-rDT conjugates. (B) Representative pattern for CPS-rDTAH conjugates. Numbers: 1, murine hyperimmune cholera O139 antiserum, 3 μl; 2, equine DT antiserum, 5 μl; 3, conjugate (PS, 1 to 4 μg; PR, 1 to 8 μg).

(ii) CDAP-mediated synthesis of CPS-rDTAH conjugates.

I:CPS-rDTAH and II:CPS-rDTAH were prepared under the same conditions except the CDAP/CPS ratios (wt/wt) were 4:5 and 1:5, respectively. Gel filtration of either conjugate on Sepharose CL-4B showed two peaks (V0 and Kd 0.4), both containing polysaccharide and protein (Fig. 3B). The void volume fractions were pooled and are denoted as conjugates I:CPS-rDTAH and II:CPS-rDTAH: their polysaccharide/protein ratios were 0.90 and 0.99, respectively. The yield of I:CPS-rDTAH was 45%. The yield of II:CPS-rDTAH could not be determined because of an accidental loss of some material. Both conjugates formed a single precipitin line when reacted with murine V. cholerae O139 and equine DT hyperimmune sera by double immunodiffusion (Fig. 4B).

Serum antibody responses elicited by conjugates. (i) Anti-CPS IgG.

CPS alone did not elicit a significantly different antibody response compared to saline (0.22 versus 0.19) (Table 3). None of the conjugates elicited a statistically significant antibody response after the first dose. All four conjugates elicited significant rises of anti-CPS IgG after the second dose (P < 0.006). However, only three, II:CPSAH-rDT, I:CPS-rDTAH, and II:CPS-rDTAH, elicited a booster response following the third dose compared to the second one (P < 0.003). There were no significant differences between the post-third levels elicited by these three conjugates (10.3 versus 11.5 versus 4.21): all were significantly higher than those elicited by I:CPSAH-rDT (10.3, 11.5, and 4.21 versus 0.43; P < 0.0001).

TABLE 3.

Serum IgG response specific to CPS and DT elicited in mice (n = 10/group) by V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with rDTa

| Conjugate | Dose no. | EU/ml (25–75 centiles)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CPS IgGb | Anti-DT IgGc | ||

| I:CPSAH-rDT | 1 | 0.13 (0.11–0.17) | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) |

| 2 | 0.35 (0.24–0.5) | 52.8 (33.8–87.4) | |

| 3 | 0.43 (0.28–0.58) | 254 (121–376) | |

| II:CPSAH-rDT | 1 | 0.23 (0.16–0.28) | 0.60 (0.2–2.6) |

| 2 | 1.04 (0.35–0.68) | 186 (155–233) | |

| 3 | 10.3 (1.67–12.2) | 1050 (715–1210) | |

| I:CPS-rDTAH | 1 | 0.11 (0.11–0.14) | 0.70 (0.37–1.3) |

| 2 | 0.89 (0.39–1.14) | 81.1 (52.3–128) | |

| 3 | 11.5 (4.99–29.7) | 255 (128–548) | |

| II:CPS-rDTAH | 1 | 0.22 (0.18–0.27) | 0.80 (0.34–2.8) |

| 2 | 0.49 (0.35–0.68) | 146 (90–214) | |

| 3 | 4.21 (1.67–12.2) | 279 (175–388) | |

CPS alone after three injections did not elicit anti-CPS IgG to a significantly different extent compared to saline (0.21 EU versus 0.19 EU).

All four conjugates elicited a significant rise of anti-Cls Ig after the second injection (P < 0.006). Only II:CPSAH-rDT, I:CPS-rDTAH, and II:CPS-rDTAH elicited a booster after the third injection (P < 0.003).

All four conjugates elicited significant rises of anti-DT IgG after the second and third injections. After the third injection, II:CPSAH-rDT elicited the highest and most statistically significantly different level compared to the other conjugates (P < 0.0007).

(ii) Anti-DT IgG.

All conjugates elicited significant rises of anti-DT IgG after the second and third injections compared to the first injection (P < 0.0001). II:CPSAH-rDT induced the highest level of anti-DT IgG of all conjugates; however, only the post-third injection level was statistically significantly higher (1,050 versus 245, 255, and 279; P < 0.0007).

Vibriocidal activity of murine sera.

Eleven representative sera from mice injected three times with II:CPSAH-rDT or I:CPS-rDTAH were tested for vibriocidal activity (Table 4). Their titers ranged from 1,600 to 6,400: II:CPSAH-rDT induced slightly higher titers (3,200 to 6,400) than did I:CPS-rDTAH (1,600 to 3,200). These two groups of sera showed a similar range of anti-CPS IgG levels, while the anti-CPS IgM levels were slightly higher in mice injected with II:CPSAH-rDT than in mice injected with I:CPS-rDTAH. Similar vibriocidal results were demonstrated with the heavily capsulated V. cholerae O139 MDO12C variant (the strain which was used for purification of the CPS) and other clinical isolates as the target strains (not shown).

TABLE 4.

Vibriocidal activity of representative sera from mice injected three times with the conjugates of V. cholerae O139 CPS and rDTa

| Conjugate | Amt of anti-CPS (EU)

|

Vibriocidal titer

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | Untreated serum | Treated with 2-ME | |

| II:CPSAH-rDT | 13.2 | 5.43 | 3,200 | 400 |

| 17.5 | 3.64 | 1,600 | 400 | |

| 42.2 | 6.94 | 3,200 | 800 | |

| 54.5 | 9.11 | 6,400 | 1,600 | |

| 180.8 | 10.5 | >6,400 | 1,600 | |

| I:CPS-rDTAH | 15.5 | 4.02 | 1,600 | 400 |

| 18.9 | 1.45 | 1,600 | 800 | |

| 27.2 | 2.05 | 1,600 | 200 | |

| 29.7 | 2.38 | 1,600 | 400 | |

| 36.3 | 2.54 | 3,200 | 800 | |

| 68.5 | 2.32 | 3,200 | 800 | |

Serum anti-CPS IgG and IgM levels are expressed in EU/ml compared to a murine hyperimmune cholera O139 serum arbitrarily assigned 1,000 EU for anti-CPS IgG and 100 EU for anti-CPS IgM. The vibriocidal assay was performed with V. cholerae O139 isolate SPH1168 as the target strain and twofold serially diluted sera starting from a 1:50 dilution. The vibriocidal titer is defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that caused a ≥60% reduction in the number of bacteria compared to the complement control. Sera from mice injected with saline or CPS had vibriocidal titer of <50.

Following treatment with 2-ME, the vibriocidal titers of most sera declined about fourfold; however, all retained significant levels of vibriocidal activity.

Vibriocidal activity in convalescent sera of cholera patients infected with V. cholerae O139.

Vibriocidal titers of 20 patient sera ranged from 100 to 6,400 (Table 5). After absorption with CPS, titers of all sera declined to ≤50 (baseline for the assay).

TABLE 5.

Serum vibriocidal titers of convalescent sera from patients infected with V. cholerae O139 measured before and after absorption with CPS or treatment with 2-ME

| Patient | Vibriocidal titera

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | CPS absorbed | 2-ME treated | |

| SK 391-2 | 3,200 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 395-2 | 1,600 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 428-2 | 800 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 456-2 | 400 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 458-2 | 3,200 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 494-2 | 100 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 504-2 | 400 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 522-2 | 1,600 | <50 | 50 |

| SK 577-2 | 1,600 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 591-2 | 1,600 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 597-2 | 800 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 599-2 | 3,200 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 622-2 | 400 | <50 | 50 |

| SK 639-2 | 400 | <50 | 400 |

| SK 646-2 | 3,200 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 720-2 | 1,600 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 741-2 | 800 | <50 | <50 |

| SK 749-2 | >6,400 | 50 | 100 |

| SK 755-2 | 1,600 | <50 | 200 |

| SK 760-2 | 1,600 | <50 | 50 |

Each vibriocidal assay was performed with twofold serially diluted tested serum starting from a 1:50 dilution and using V. cholerae O139 SPH1168 as the target strain.

Treatment with 2-ME reduced the vibriocidal activity to ≤50 in 17 of 20 sera. The vibriocidal titer of SK 639-2 remained at the same level (i.e., 400) as was found in the untreated serum.

DISCUSSION

Probably because of its complex structure (19, 35) and relatively tight folded conformation (10), the development of synthetic schemes for preparation of V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugate vaccine was laborious and required using a readily available protein carrier such as chicken serum albumin (Kossaczka and Szu, submitted). Slight modifications of the two most successful synthetic schemes were used to prepare conjugates with the medically useful rDT. Both synthetic schemes involved ADH as the linker and two different activating agents (CDAP or EDC): (i) CDAP was used to prepare the AH derivative of CPS (CPSAH) and EDC for rDTAH and (ii) conjugation of CPSAH with rDT (CPSAH-rDT) was mediated by EDC, while CPS-rDTAH conjugates were prepared by binding rDTAH with CDAP-activated CPS. The resultant conjugates elicited serum anti-CPS IgG after the second injection and a booster response after the third injection when administered to mice by a clinically relevant method and route. Similar to the immunologic properties of the V. cholerae O1 Inaba O-specific polysaccharide conjugates with cholera toxin (11) and V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with chicken serum albumin (unpublished data), the V. cholerae O139 CPS-rDT conjugates elicited high titers of serum vibriocidal antibodies in mice. Treatment with 2-ME reduced (∼4-fold) but did not eliminate their vibriocidal activity, indicating that much of this activity was mediated by anti-CPS IgG.

I:CPS-rDTAH elicited the highest level of anti-CPS IgG after the third injection (11.4 EU), but this was not statistically different from the levels elicited by II:CPSAH-rDT (10.3 EU) or II:CPS-rDTAH (4.21 EU). On the basis of these data, we plan to clinically evaluate I:CPS-rDTAH and II:CPSAH-rDT.

All four conjugates elicited significant rises of anti-DT IgG after the second and third injections. II:CPSAH-rDT elicited the highest post-third injection level of anti-DT IgG that was significantly different from those of the other three conjugates (P < 0.0007).

I:CPSAH-rDT, prepared by synthesis of CPSAH with rDT at the higher concentration of EDC (0.05 M), elicited the lowest level of anti-CPS IgG. The level of anti-DT IgG induced by this conjugate was comparable to those elicited by both of CPS-rDTAH, indicating that there was no correlation between the antibodies elicited to the CPS and those elicited to the protein carrier.

There is some confusion about the vibriocidal activity of convalescent sera from patients infected with V. cholerae O139 (3, 17, 25, 28, 40). We found that patient sera convalescent from cholera O139 were uniformly vibriocidal. The data variation among laboratories may be explained by the different complement dilutions used for the vibriocidal assays. We found that highly diluted complement, used in the vibriocidal assay for V. cholerae O1, is not sufficient to mediate killing of V. cholerae O139 which has a capsule. We showed that the undiluted baby rabbit serum, as the source of complement, is a reliable reagent for demonstrating antibody-initiated lysis of V. cholerae O139.

Similar to the serologic response of humans to the V. cholerae O1 infection (1, 24, 29, 32), our results showed that vibriocidal activity of sera from patients infected with serotype O139 was mostly specific to its surface polysaccharide (CPS) and mediated by IgM. This is also true for parenterally administered killed whole-cell cholera O1 vaccine or orally administered attenuated cholera O1 strains (7, 27, 44). In contrast, parenterally administered polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines elicit, in addition to IgM, high levels of serum anti-polysaccharide IgG (i.e., 2-ME resistant) (11, 38). We proposed that it is IgG that penetrates the intestinal epithelium and initiates complement-mediated lysis of the bacterial inoculum and that measurement of the conjugate-induced serum IgG specific to the surface polysaccharides of both V. cholerae O1 and O139 should provide a reliable method for standardization of these vaccine candidates (36, 39).

Diafiltration through YM100 allowed a rapid separation of the low-molecular-weight impurities from V. cholerae O139 CPS. When the material eluted at Kd 0.91 from Sepharose CL-4B, representing only 1% (by weight) of the unfractionated CPS, was concentrated 100 times and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot with murine hyperimmune cholera O139 antiserum, it showed two fast-moving bands (unpublished data), a finding similar to that reported for LPS of V. cholerae O139 (4, 45). Our results indicate that diafiltration could be adapted for rapid separation of LPS from other medically useful polysaccharides.

In summary, V. cholerae O139 CPS conjugates with rDT elicited high levels of serum anti-CPS IgG in mice with vibriocidal activity. The vibriocidal activity of convalescent sera from patients infected with V. cholerae O139 was mediated mostly by anti-CPS IgM. To verify whether a critical level of anti-CPS IgG will confer immunity to V. cholerae O139, clinical trials of the two most immunogenic CPS-rDT conjugates are planned.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dolores A. Bryla for performing statistical analysis, Steven Hunt for skillful assistance, Ladaporn Bodhidatta for providing V. cholerae isolates and patients' sera, and Rachel Schneerson for comments and suggestions regarding the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benenson A S, Saad A, Mosley W H. Serological studies in cholera. 2. The vibriocidal antibody response of cholera patients determined by a microtechnique. Bull W H O. 1968;38:277–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coster T S, Killeen K P, Waldor M K, Beattie D T, Spriggs D R, Kenna J R, Trofa A, Sadoff J C, Mekalanos J J, Taylor D N. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of live attenuated Vibrio cholerae O139 vaccine prototype. Lancet. 1995;345:949–952. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox A D, Brisson J-R, Varma V, Perry M B. Structural analysis of the lipopolysaccharide from Vibrio cholerae O139. Carbohydr Res. 1996;290:43–58. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fass R, van de Walle M, Shiloach A, Joslyn A, Kaufman J, Shiloach J. Use of high-density cultures of Escherichia coli for high-level production of recombinant Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;36:65–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00164700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finkelstein R A. Vibriocidal antibody inhibition (VAI) analysis: a technique for the identification of the predominant vibriocidal antibodies in serum and for the detection and identification of Vibrio cholerae antigens. J Immunol. 1962;89:264–271. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein R A. Cholera. In: Germanier R, editor. Bacterial vaccines. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein R A, Boesman-Finkelstein M, Sengupta D K, Page W J, Stanley C M, Phillips T E. Colonial opacity variations among the choleragenic vibrios. Microbiology. 1997;13:23–24. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotschlich E C, Rey M, Sanborn W R, Triau R, Cvjetanovic B. The immunological responses observed in field studies in Africa with group A meningococcal vaccines. Prog Immunobiol Stand. 1972;129:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunawardena A, Fiore C R, Johnson J A, Bush C A. Conformation of a rigid tetrasaccharide epitope in the capsular polysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O139. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12062–12071. doi: 10.1021/bi9910272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R K, Taylor D N, Bryla D A, Robbins J B, Szu S C. Phase 1 evaluation of Vibrio cholerae O1, serotype Inaba, polysaccharide-cholera toxin conjugates in adult volunteers. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3095–3099. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3095-3099.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall R H, Khambaty F M, Kothary M H, Keasler S P, Tall B D. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 serogroup associated with cholera gravis genetically and physiologically resembles O1 El Tor cholera strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3859–3863. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3859-3863.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoge C W, Bodhidatta L, Echeverria P, Deesuwan M, Kitporka P. Epidemiologic study of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 in Thailand: at the advancing edge of the eighth pandemic. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:263–268. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inman J K, Dintzis H M. The derivatization of cross-linked polyacrylamide beads. Controlled induction of functional groups for the purpose of special biochemical absorbents. J Biochem. 1969;4:4074–4080. doi: 10.1021/bi00838a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson V G, Nicholls P J. Histidine 21 does not play a major role in diphtheria toxin catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4349–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson J A, Joseph A, Morris J G., Jr Capsular polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines against Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1995;93:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonson G, Osek J, Svennerholm A M, Holmgren J. Immune mechanisms and protective antigens of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139 as a basis for vaccine development. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3778–3786. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3778-3785.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keleti G, Lederer W. Handbook of micromethods for the biological sciences: 3,6-dideoxyhexoses. New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company; 1974. pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knirel Y A, Paredes L, Jansson P-E, Weintraub A, Widmal G, Albert M J. Structure of the capsular polysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O139 synonym Bengal containing d-galactose-4,5-cyclophosphate. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.391zz.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohn J, Wilchek M. 1-Cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridinium tetrafluoroborate as a cyanylating agent for the covalent attachment of ligand to polysaccharide resins. FEBS Lett. 1983;154:209–210. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konadu E, Shiloach J, Bryla D A, Robbins J B, Szu S C. Synthesis, characterization, and immunological properties in mice of conjugates composed of detoxified lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella paratyphi A bound to tetanus toxoid, with emphasis on the role of O-acetyls. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2709–2715. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2709-2715.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kossaczka Z, Bystricky S, Bryla D A, Shiloach J, Robbins J B, Szu S C. Synthesis and immunological properties of Vi and Di-O-acetyl pectin protein conjugates with adipic acid dihydrazide as the linker. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2088–2093. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2088-2093.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lees A, Nelson B L, Mond J J. Activation of soluble polysaccharides with 1-cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridium tetrafluoroborate for use in protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccines and immunological reagents. Vaccine. 1996;14:190–198. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine M M, Nalin D R, Craig J P, Hoover D, Bergquist E J, Waterman D, Holley H P, Hornick R B, Pierce N P, Libonati J P. Immunity of cholera in man: relative role of antibacterial versus antitoxic immunity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:3–9. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Losonsky G A, Lim Y, Motamedi P, Comstock L, Johnson J A, Morris J G, Jr, Tacket C O, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Vibriocidal antibody responses in North American volunteers exposed to wild-type or vaccine Vibrio cholerae O139: specificity and relevance to immunity. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:264–269. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.3.264-269.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meno Y, Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J, Amako K. Morphological and physical characterization of the capsular layer of Vibrio cholerae O139. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:339–344. doi: 10.1007/s002030050651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merritt C B, Sack R B. Sensitivity of agglutinating and vibriocidal antibodies to 2-mercaptoethanol in human cholera. J Infect Dis. 1970;121:S25–S30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.supplement.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris J G, Losonsky G E, Johnson J A, Tacket C O, Nataro J P, Panigrahi P, Levine M M. Clinical and immunologic characteristics of Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal infection in North American volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:903–908. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosley W H. The role of immunity in cholera. A review of epidemiological and serological studies. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1969;27(Suppl. 1):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandy R K, Albert M J, Ghose A C. Serum antibacterial and antitoxin responses in clinical cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal and evaluation of their importance in protection. Vaccine. 1996;14:1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(96)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nandy R K, Mukhopadhyay S, Ghosh A N, Ghose A C. Antibodies to the truncated (short) form of “O” polysaccharides (TFOP) of Vibrio cholerae O139 lipopolysaccharides protect mice against experimental cholera and such protection is mediated by inhibition of intestinal colonization of vibrios. Vaccine. 1999;17:2844–2852. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neoh S H, Rowley D. The antigens of Vibrio cholerae involved in the vibriocidal action of antibody and complement. J Infect Dis. 1980;121:505–513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/121.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pike R M, Chandler C H. Serological properties of γG and γM antibodies to the somatic antigen of Vibrio cholerae during the course of immunization of rabbits. Infect Immun. 1971;6:803–809. doi: 10.1128/iai.3.6.803-809.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plikaytis B D, Holder P F, Carlone G M. Program ELISA for Windows: User's manual 12, version 1.00. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preston L M, Xu Q, Johnson J A, Joseph A, Maneval D R, Jr, Hussain K, Reddy G P, Bush C A, Morris J G., Jr Preliminary structure determination of the capsular polysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal A11837. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:835–838. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.835-838.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Szu S C. Perspective. Hypothesis: serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1387–1398. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneerson R, Barrera O, Sutton A, Robbins J B. Preparation, characterization and immunogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Exp Med. 1980;152:361–376. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sengupta D K, Boesman-Finkelstein M, Finkelstein R A. Antibody against the capsule of Vibrio cholerae O139 protects against experimental challenge. Infect Immun. 1996;64:343–345. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.343-345.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szu S C, Gupta R, Robbins J B. Induction of serum vibriocidal antibodies by O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines for prevention of cholera. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik O, editors. Vibrio cholerae. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tacket C O, Losonsky G E, Nataro J P, Comstock L, Michalski J, Edelman R, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Initial clinical studies of CVD 112 Vibrio cholerae O139 live oral vaccine: safety and efficacy against experimental challenge. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:883–886. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guideline on validation of the Limulus amebocyte lysate test as an end-product endotoxin test for human and animal parenteral drugs, biological products, and medical devices. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. Emergence of a new cholera pandemic: molecular analysis of virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae O139 and development of a live vaccine prototype. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:278–283. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldor M K, Colwell R, Mekalanos J J. The Vibrio cholerae O139 serogroup antigen includes an O-antigen capsular and lipopolysaccharide virulence determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11388–11392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wasserman S G, Losonsky G A, Noriega F, Tacket C O, Castaneda E, Levine M M. Kinetics of the vibriocidal antibody response to live oral cholera vaccines. Vaccine. 1994;11:1000–1003. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weintraub A, Widmalm G, Jansson P-E, Jansson M, Hultenby K, Albert M J. Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal possesses a capsular polysaccharide which may confer increased virulence. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:235–241. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]