Abstract

Synthetic biology aims to design or assemble existing bioparts or bio-components for useful bioproperties. During the past decades, progresses have been made to build delicate biocircuits, standardized biological building blocks and to develop various genomic/metabolic engineering tools and approaches. Medical and pharmaceutical demands have also pushed the development of synthetic biology, including integration of heterologous pathways into designer cells to efficiently produce medical agents, enhanced yields of natural products in cell growth media to equal or higher than that of the extracts from plants or fungi, constructions of novel genetic circuits for tumor targeting, controllable releases of therapeutic agents in response to specific biomarkers to fight diseases such as diabetes and cancers. Besides, new strategies are developed to treat complex immune diseases, infectious diseases and metabolic disorders that are hard to cure via traditional approaches. In general, synthetic biology brings new capabilities to medical and pharmaceutical researches. This review summarizes the timeline of synthetic biology developments, the past and present of synthetic biology for microbial productions of pharmaceutics, engineered cells equipped with synthetic DNA circuits for diagnosis and therapies, live and auto-assemblied biomaterials for medical treatments, cell-free synthetic biology in medical and pharmaceutical fields, and DNA engineering approaches with potentials for biomedical applications.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Nanobiotechnology

Introduction

The concept of synthetic biology was proposed in 1910s by Stephane Le Duc.1 In this field, research strategies have been changed from the description and analysis of biological events to design and manipulate desired signal/metabolic routes, similar to the already defined organic synthesis. Unlike organic synthesis successfully developed in the early 19th century,2 synthetic biology is restricted by DNA, RNA and protein technology within the complexity of biological systems. Today, synthetic biology has been developed extensively. It becomes a multidisciplinary field aims to develop new biological parts, systems, or even individuals based on existing knowledge. Researchers can apply the engineering paradigm to produce predictable and robust systems with novel functionalities that do not exist in nature. Synthetic biology is tightly connected with many subjects including biotechnology, biomaterials and molecular biology, providing methodology and disciplines to these fields.

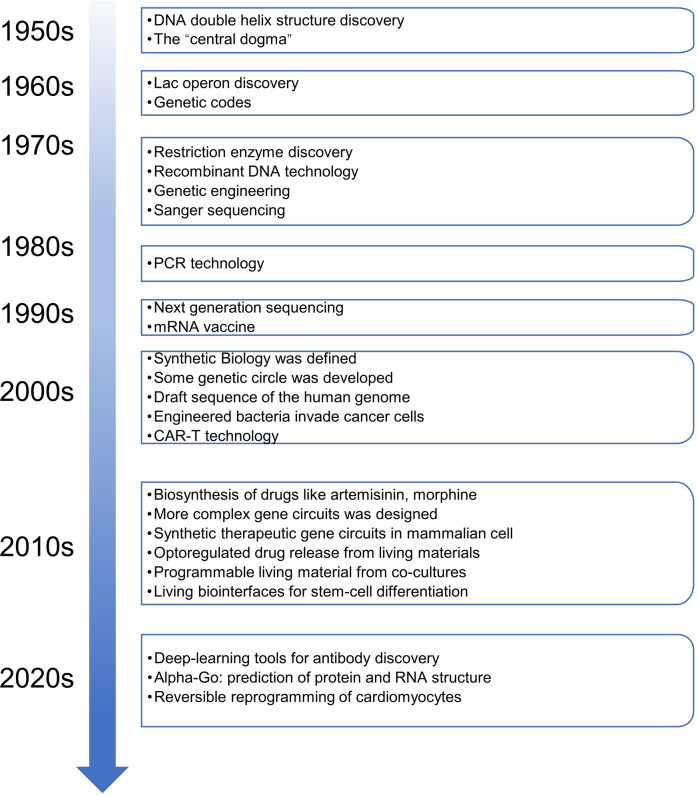

The timeline of synthetic biology developments is summarized here (Fig. 1). In general, the history of synthetic biology can be divided into three stages. The initial stage was found across the 20th century. Although the simplest organisms such as virus particles, bacteria, archaea and fungi were hard to engineer in the 20th century, some achievements were still acquired in the early explorations including the synthesis of crystalline bovine insulin,3 chemical synthesis of DNA and RNA,4 decoding of genetic codes5 and the establishment of central dogma of molecular biology.6 Synthetic biology has been accumulating its strengths in this period, as knowledge of genome biology and molecular biology are developed rapidly at the end of the 20th century (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of major milestones in synthetic biology. The timeline begins at 1950s and expands to 2020s. Important events are listed in the right panels

The development stage begins in the 21st century. In the first decade of the new millennium, synthetic biology is known to every biological researcher to include inventions of bioswitches,7 gene circuits based on quorum sensing signals,8 yeast cell-factory for amorphadiene synthesis9 (Table 1), BioBrick standardized assembly10 and the iGEM conferences11 (Fig. 1). Two principles in synthetic biology designs have been considered in this stage including bottle-up12 and top-down13 ones, referring to the de novo creations of artificial lives by assembling basic biological molecules and engineering natural-existed cells to meet actual demands, respectively. However, most circuits are well-designed but still not enough for producing complex metabolites or sensing multiple signals, especially the applications are not well prepared for medical and pharmaceutical usages. Anyhow, synthetic biology is gradually becoming a most topical area, on the eve of rapid developments.

Table 1.

Applications and yields of biosynthesized pharmaceuticals

| Application | Classification | Production host | Titer (g/L) | Year | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisic acid | A precursor of anti-malarial drug artemisinin | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 25 | 2013 | 23 |

| Thebaine | Pain management and palliative care | Alkaloids | E. coli/Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.1 × 10−3/6.6 × 10−5 | 2016/2015 | 323,324 |

| Hydrocodone | Pain management and palliative care | Alkaloids | E. coli/Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 4 × 10−5/3 × 10−7 | 2016/2015 | 323,324 |

| Codeine | Treat severe pain | Alkaloids | E. coli | 304 µg L−1 OD−1 | 2019 | 396 |

| Sitagliptin | Increased insulin secretion | Amines | In vitro | N.A.a | 2010 | 337 |

| Ginsenoside Rh2 | Cancer prevention and therapy | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.2 | 2019 | 317 |

| Ginsenoside compound K | Increased resistance to stress and aging | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.4 × 10−3 / 1.17/5.0 | 2014/2020/2021 | 318,397,398 |

| Guaia-6,10(14)-diene | A precursor of kidney cancer drug Englerin A | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.8 | 2020 | 399 |

| Taxadiene | A precursor of cancer drug Taxol | Terpenoids | E. coli / Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.0 / 8.7 × 10−3 | 2010/2008 | 315,400 |

| Adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B12) | Vital cofactor for human | Corrinoids | E. coli | 307 µg g−1 DCWb | 2018 | 401 |

| Baicalein | Neuroprotective agent | Flavonoids | E. coli | 0.02 | 2019 | 402 |

| Miltiradiene | A precursor of cardiovascular diseases drug tanshinone | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.3 / 3.5 | 2012/2020 | 403,404 |

| Catharanthine | A precursor of anti-cancer drug vinblastine and vincristine | Alkaloids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.7 × 10−5 | 2022 | 405 |

| Breviscapine | Treat cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases | Flavonoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.2 | 2018 | 406 |

| Scopolamine | Treat neuromuscular disorders | Alkaloids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 6 × 10−2 | 2020 | 407 |

| (S)-tetrahydropalmatine | Use as an analgesic and anxiolytic drug | Alkaloids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 3.6 × 10−6 | 2021 | 328 |

| Cannabigerolic acid | A precursor of various cannabinoids; reduce pain without hallucination | Alkaloids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.1 | 2019 | 327 |

| Triptolide | Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 30.5 μg g−1 | 2020 | 408 |

| Psilocybin | Treatment of addiction, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. | Amino acid derivatives | E. coli / Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1.2 / 0.6 | 2019 / 2020 | 330,331 |

| Monacolin J | A precursor for simvastatin (Zocor), an important drug for treating hypercholesterolemia. | Polyketides | Aspergillus terreus | 4.7 | 2017 | 409 |

| Acarbose | Clinically used to treat patients with type 2 diabetes | oligosaccharide | Actinoplanes sp. | 7.4 | 2020 | 410 |

| α-Tocoterienol | Natural vitamin E, used as a valuable supplementation | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.3 | 2020 | 411 |

| Avermectin B1a | Widely used in the field of animal health, agriculture and human health | Polyketides | Streptomyces avermitilis | 6.4 | 2010 | 412 |

| Carnosic acid | Potent antioxidant and anticancer agents | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1 × 10−3 | 2016 | 413 |

| Noscapine | Anticancer drug | Alkaloids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2.2 × 10−3 | 2018 | 414 |

| Farnesene | Widely used in industry, a precursor of vitamin E | Terpenoids | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 55.4 | 2022 | 415 |

| (−)-Deoxypodophyllotoxin | A precursor to anti-cancer drug etoposide | Alkaloids | Nicotiana benthamiana | 4.3 mg/g dry plant weight | 2019 | 416 |

| Dencichine | Promote aggregation of platelets | Amino acid derivatives | E. coli | 1.29 | 2022 | 334 |

aN.A. not applicable

bDCW the abbreviation of dry cell mass

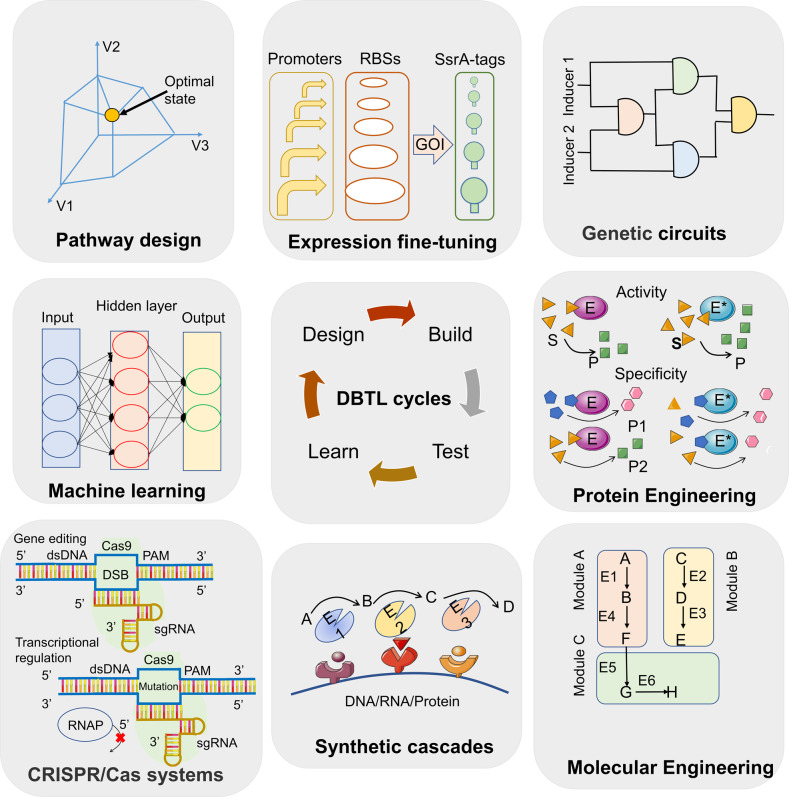

The fast-growing stage begins from the 2010s, the emergences of genome editing technologies especially CRISPR/Cas9,14 low-cost DNA synthesis,15 next-generation DNA sequencing16 and high-throughput screening methods,17 workflows of design-build-test-learn (DBTL)18 and progresses in engineering biology19 (Fig. 1), have allowed synthetic biology to enter a fast-growing period,20 both in the lab-scale discoveries and industry-scale productions. Typically, Venter et al. assembled an artificial chromosome of Mycoplasma mycoides and transplanted it to M. capricolum to create new living cells.21 Besides, new methods have accelerated the discovery and engineering of metabolite biosynthesis pathways, microbial artemisinic acid synthesis has been made possible,22,23 which is the first industrialized plant metabolite produced by microbial cells. To realize the ultimate goal of design bio-systems similar to design electronic or mechanical systems, this is just the beginning. More efforts are needed to generate complex and stable biocircuits for various applications in the present of synthetic biology.

Besides scientists, investors also have realized the potentials in this field. Financial investments help establish synthetic-biology-related companies encouraged by the prediction that the global market of synthetic biology valued 9.5 billion dollars by 2021, including synthetic biology products (e.g., BioBrick parts, synthetic cells, biosynthesized chemicals) and enabling technologies (e.g., DNA synthesis, gene editing),24 they are expected to reach 37 billion dollars by 2026. Most investments focus on medical applications.25 Scientists and capital market are all optimistic about the future.

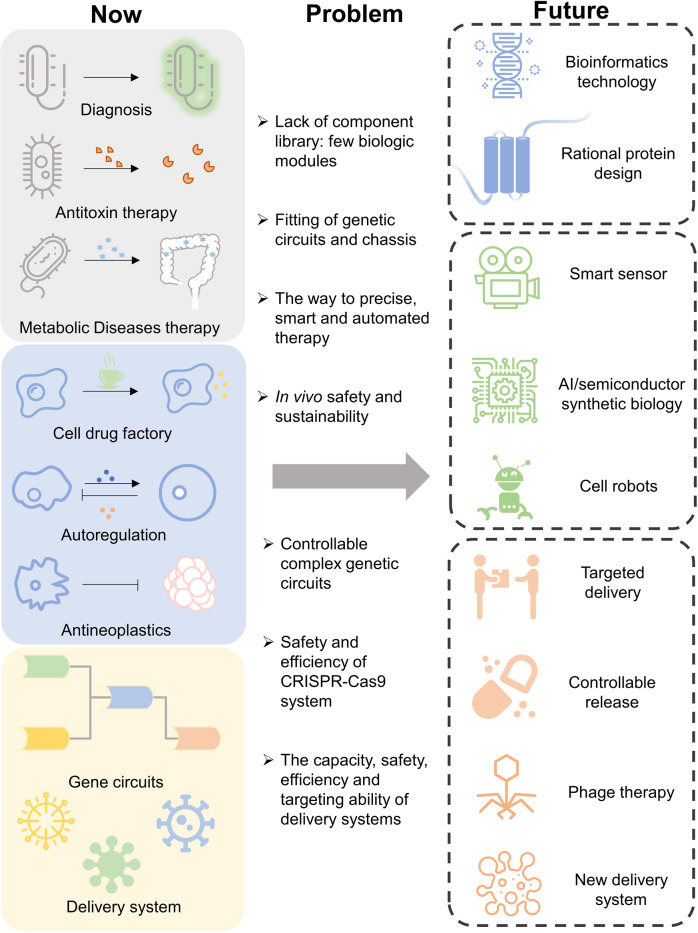

Started from chemical biosynthesis, synthetic biology has been expanded to cover areas in medical treatments, pharmaceutical developments, chemical engineering, food and agriculture, and environmental preservations. This paper focuses on the advances of synthetic biology in medical and pharmaceutical fields, including cell therapies, bacterial live diagnosis and therapeutics, production of therapeutic chemicals, nanotechnology and nanomaterial applications and targeted gene engineering.

Genetic engineering of therapeutic chassis

Engineered mammalian cells for medical applications

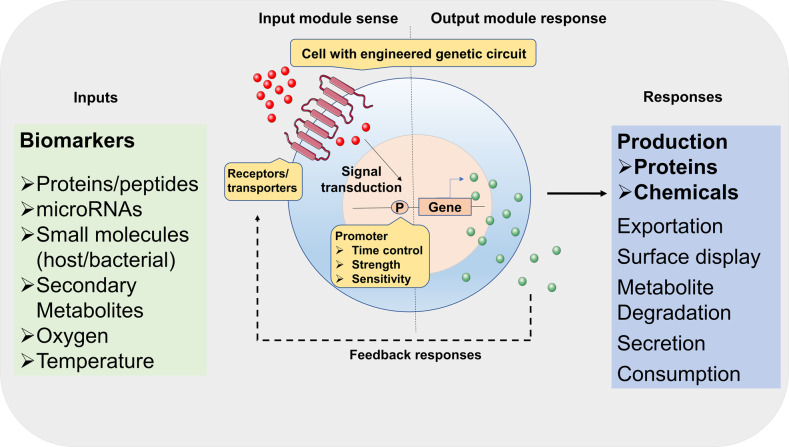

With the advances in synthetic biology, researchers created various novel therapies using living cell chassis rationally designed from existing signaling networks with new constructs for their purposes, including e.g., production of medical biomolecules, synthetic gene networks for sensing or diagnostics, and programmable organisms, to handle mechanisms underlying disease and related organism/individual events (Fig. 2). We highlighted here synthetic biology strategies in mammalian cell engineering for metabolic disorders, tissue engineering and cancer treatments, as well as approaches in cell therapy and the design of gene circuits.

Fig. 2.

Development of smart living cells based on synthetic biology strategies. Smart cells can sense various environmental biomarkers, from chemicals to proteins. External signals are transducted into cells to trigger downstream responses. The products are also in the form of chemicals to proteins for customized demands. The sensing-reponsing system is endowing cells with new or enhanced abilities. P represents promoters

Therapies based on chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells

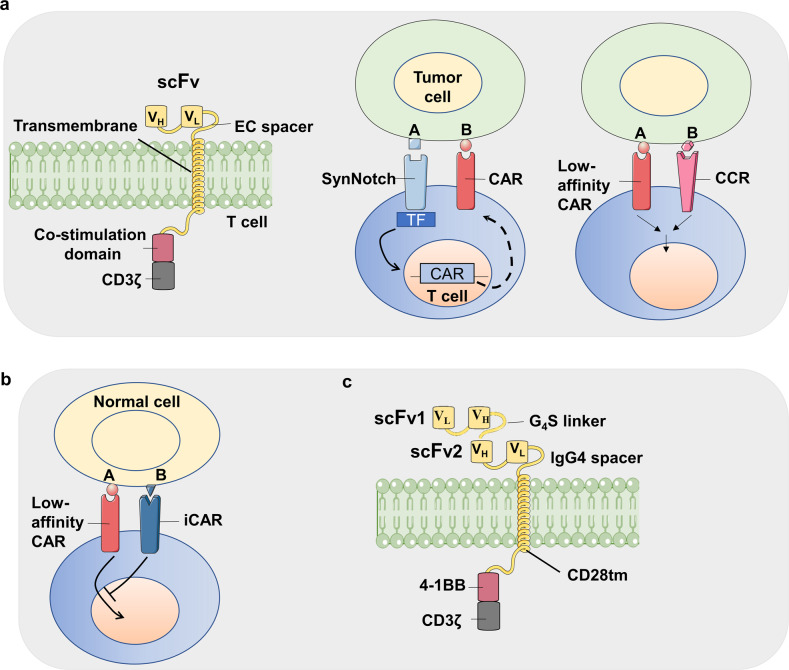

CARs are engineered receptors containing both antigen-binding and T cell-activating domains. T cells are acquired from patients and engineered ex vivo to express a specific CAR, and followed by transferring into the original donor patient, where they eliminate cancer cells that surface-displayed the target antigen.26 CAR-T is a novel cell therapy began from 2000s.27 The first generation of CARs are single-chain variable fragments (scFv) targeting CD19.28 The development of artificial CARs comprises three generations. The first-generation CARs only contain a CD3ζ intracellular domain, while the second-generation CARs also possess a co-stimulatory domain, e.g., 4-1BB or CD3ζ (Fig. 3). Studies with the third-generation chimeric antigen receptors with multiple co-stimulatory signaling domains are also under investigation (Fig. 3).29 Because scFvs have the ability to recognize cell surface proteins, the targeting of tumors mediated via CAR-T cell is neither restricted nor dependent on antigen processing and presentation. CAR-T cells are therefore not limited to tumor escaping from MHC loss. For cancer immunotherapy, the main advantage of employing CAR-based methods is attributed to that the scFv derived from antibodies with affinities several orders of magnitude higher than conventional TCRs.30 In addition, CARs can target glycolipids, abnormal glycosylated proteins and conformational variants that cannot be easily recognized by TCRs. Based on clinical trial results, there is an increasing evidence that CAR-T cells have the ability to deliver powerful anti-tumor therapeutic effects, leading to the recent FDA approval of CAR-T therapies directed against the CD19 protein for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Fig. 3.

Synthetic biology in the designs of chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). a The AND gate used in artificial CARs. Three typical CARs i.e. Costimulation domain-based second-generation CAR, synNotch receptor-assisted CAR with multiple recognization mechanisms and chimeric costimulation receptor (CCR)-based CAR are exhibited from left to right. b The artificial CARs with inhibitory CAR (iCAR) system. The system can prevent recognizing self-antigens on somatic cells. c The artificial CARs sensing different tumor antigens. Two ScFvs recognizing different targets are tandemly fused, the engineered CAR can be triggered by multiple antigens. The figure is inspired by the paper468

In addition, CAR-T applications are stepping into commercialization. The first approved CAR T-cell therapy was Kymriah which is CD19-targeted for treating DLBCL developed by Novartis and University of Pennsylvania.31 DLBCL is a typical form of non-hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) that consist of 40% of total lymphomas.32 The FDA also approved Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) in 2017 for DLBCL treatments.33 In the clinical studies, patients with DLBCL were treated with the CD19-targeted CAR T-cells, with 25% partial responders and more than 50% complete responders.34,35 Durable responses of over two years were observed, indicating the therapeutic effects of the CAR-T cells. However, cytokine storm, an excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, was observed in Yescarta treated patients (13%),36 indicating the safety needs to be improved.

The selection of target antigen is the determinant in CAR-T cell therapies.37–39 If CAR-T cells can recognize protein expressed on non-malignant cells, severe cell toxicities could occur with the off-target activities.40 The optimal target antigen is the one that is consistently expressed on the surface of cancer cells but not on the surface of normal cells.37,41,42 Multiple myeloma is hard to treat via chemicals or stem cell transplantation.43,44 CAR-T cell therapies are effective for multiple myeloma in preclinical studies.45 However, to date, no antigen has been characterized that is strongly and constantly expressed on multiple myeloma cells but not on somatic cells. Among the antigens used so far, a member of the TNF superfamily proteins, B cell maturation antigen (BCMA), is the most favorable candidate for a multiple myeloma cell-directed CAR-T therapy target.42,46,47 BCMA is expressed in cancer cells in almost all multiple myeloma patients, the expression of this antigen on somatic cells is limited to plasma cells and some kinds of B cells.42,48 BCMA was the first antigen for multiple myeloma to be used in a clinical trial via a CAR-T cell approach leading to systematic responses in patients with this cancer.40,42,49 Twelve patients received BCMA CAR-T cells in the dose-gradient clinical trial. Two patients treated with 9 × 106 CAR-T cells/kg body weight were obtained with good remissions, though the treatment had toxicity related to cytokine storms.49 Many clinical trials investigating the safety and/or efficacy of anti-BCMA CAR-T cells are currently ongoing or finished.

Idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma, also abbreviated as Ide-cel) is developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb, uses the anti-BCMA 11D5-3 scFv, the same as the 11D5-3-CD828Z CAR tested at the NCI.49 However, the co-stimulatory domain is different, the CAR used in idecabtagene vicleucel is delivered using a lentivirus vector and has a 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain instead of a CD28 one.50 In a multicenter phase I trial for idecabtagene vicleucel,50,51 the therapy is highly effective for treating multiple myeloma patients. A phase II trial named KarMMa, designed to further evaluate the safety and ability of idecabtagene vicleucel, is undergoing.52 The initial results of KarMMa demonstrates its deep, durable responses in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patients.52 Efficacy and safety were reflected in early reports, supporting a favorable idecabtagene vicleucel clinical benefit-risk profile across the target dose range in primary clinical results.

Receptor engineering in medical therapies

SynNotch receptors are a class of artificially engineered receptors that are used in medical applications (Fig. 3).53 Notch receptors are transmembrane receptors participating in signal transductions,54 comprising an extracellular domain, a transmembrane and an intracellular domain.55 The transmembrane and intracellular domains are usually retained in synNotch architects,56 whereas the signal-input extracellular domain is engineered to sense scFvs and nanobodies,57 providing possibilities of recognizing agents to initiate signaling in living cells.

Also, the modular extracellular sensor architecture (MESA) was developed intending to detect extracellular free ligands54,58 based on the synNotch idea. MESA designs have two membrane proteins each containing an extracellular ligand-binding domain which senses the chemicals or proteins and can be a small molecule-binding domain or antibody based sensing module, a transmembrane domain and either an intracellular transcriptional factor with relasing ability from the complex, protease recognition sequence or a protease. After ligand binding to the extracellular domain, MESA receptors dimerize and induce an intracellular proteolytic cleavage that allows the transcriptional factor dissociate for downstream regulations. The method allows more flexible sensor designs without limiting to Notch receptors. This system has also been remade recently to signal transduction via a split protease59 or split transcriptional factor patterns.60 The synNotch design has been constructed with a series of receptors called synthetic intramembrane proteolysis receptors (SNIPRs) containing domains from other natural receptors other than mouse Notch protein that are also cleavable by endogenous proteases.61 Similiar to synNotch, SNIPRs bind to their antigens and function via dissociating a transcriptional factor to sense cell and immune factors.62 For synNotch, SNIPR and MESA, the choice of ligand-binding domains and transcriptional factor domains enables customization of both sensing (signal input) and function (signal output) steps when using the systems. SNIPR and MESA also enrich the available engineering tools for the artificial receptor-effectors. However, some limitations still remain such as high background signals, off-target effects, the immunogenicity from the murine Notch protein, the large size of artificial receptors and transcriptional regulators.56,61,63 Many efforts are needed to improve the system.

Receptor engineering applications are commonly related to CAR-T therapies. The receptors can be designed to target two specific antigens, one using the synNotch and the other via a traditional CAR. In preclinical models, T-cells engineered for targeting dual-antigen expressing cells are established.64 TEV protease can be fused to MESA receptors, cleaving the transcriptional factor off for functionalization.58 A humanized synthetic construct can reduce immunogenicity and minimize off-target effects. Zhu et al. constructed a framework for human SNIPRs with future applications in CAR-T therapies, preventing CAR-T cells from being activated via non-tumor signals.61 Besides the above synthetic receptors, based on the same idea, Engelowski et al. designed a synthetic cytokine receptor sensing nanobodies by the fusion of GFP/mCherry nanobodies to native IL-23 intracellular domains.65 Another receptor engineering strategy is to rewire receptor-transduced signals to novel effector genes. Using a scFv complementary to VEGF, the engineered receptor senses VEGF and released dCas9 protein, then the IL-2 expression are up-regulated. The system is successfully explored in Jurkat T cells.58

The HEK-β cells used for diabetes treatments

β-cells are existing in pancreatic islets that synthesize and secrete insulin.66 As the only site of insulin synthesis in mammals, β-cells sense blood glucose using a signal transduction pathway that comprises glycolysis and the stimulus-sensing-secretion coupling process.67,68 The secretion of insulin is consisted with the following steps. Blood glucose is transported into β-cells and metabolized via glycolysis inside the cell, resulting in cell membrane depolarization, energy generation and closing of K+ATP channels, which activates the calcium channel Cav1.3 to induce calcium influx with the secretion of insulin granules. The excessive blood-glucose concentration in diabetes patients is from the deficiency of insulin-producing β cells for type 1 diabetes, or from low insulin sensitivity of body cells for type 2 diabetes.69 Using a synthetic biology-based multiple screening approach, Xie et al. engineered human kidney cells HEK-293 to sense blood glucose levels for insulin secretion.70 The design combines automatic diagnosis and treatment in diabetes therapy. The researchers demonstrated that overexpression of Cav1.3 provided the pathway for constructing a β-cell-like glucose-sensing module in somatic cells.70 The combination of Cav1.3-controlled calcium and a synthetic Ca2+-inducible promoter allowed the monitoring of glucose levels using a tuned in vivo transcriptional response. After the construction of artificial HEK-293-β cells, the cell line HEK-293-β for glucose-response insulin production which maintained glucose homeostasis for over 3 weeks, via implanting the cells intraperitoneally to mice, also auto-corrected diabetic hyperglycemia within 3 days in T1D mice in this study.

The advantages of HEK-293-β cells are clear. Compared to primate pancreatic islets, HEK-293-β cells were adequately efficient in stabilizing postprandial glucose metabolism in T1D mice. Moreover, HEK-β cells are more easily for cultivation in vitro. It is expected that the engineered human cells have the prospect to be produced easily, cost-effectively and robustly, following current rules and regulations for pharmaceutical manufacturing, allowing the production of ready-to-use commercials with good properties for product purity, stability and quality. This highly innovative engineered cell raises the possibility that any cell type could be rationally reprogramming to achieve customized abilities such as blood glucose control.

The induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for medical applications

Synthetic biology also helps in generating human stem cells via overexpressing certain de-differentiation-related genes. One of the applications is the induced pluripotent stem cells. iPSCs are pluripotent stem cells generated from somatic cells.71 Pioneered by Yamanaka’s lab, the introduction of four transcriptional factors including Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4, resulted in changing fibroblasts to embryonic stem (ES)-like cells,72 which can re-differentiate into blood cells, bone cells or neurons for possible treatment of damages to various tissues and organs.73 iPSCs are not created using human embryos, circumvented ethical concerns in contrast with ES cells.74 Additionally, autologous somatic cell-derived iPSCs avoid immunological rejections.75

iPSCs are self-renewable with continuous subculture properties.76 The somatic cell samples from patients are induced into iPSCs able to serve as an unlimited repository for medical researches. The iPSC cell lines for Down’s syndrome and polycystic kidney disease are established.77,78 An project termed StemBANCC calls for collections of iPSC cell lines for drug screening.79 Various applications combined with therapeutic chemicals and iPSC cell lines are undergoing high-throughput drug screening and analysis.80,81

iPSCs are aimed to be used for tissue regeneration and therapy developments. Type O red blood cells can be derived from iPSCs to meet demands for blood transfusion.82 When cancer patients require large quantities of NK cells in immunotherapies, the cells can be manufactured using iPSCs to circumvent their low availabilities.83 The anti-aging effects of iPSCs are observed during mouse studies.84 The chemical-induced differentiation of iPSCs to cardiomyocytes has been commonly used.85 These iPSC-cardiomyocytes are recapitulated with genetic codes in patients whom they derived, allowing the establishment of models of long QT syndrome and ischemic heart disease.85,86 Cord-blood cells can be induced into pluripotent stem cells for treating malfunctional mice retina,87 re-differentiated iPSCs are employed to cure brain lesions in mice with their motor abilities regained after the therapy.88

iPSCs are successfully used for organ regeneration, for example, ex vivo cardiomyocytes can be used to regenerate fetal hearts to normal hearts via the Yamanaka’s method.89 Human “liver buds” can be generated from three different cells including iPSCs, endothelial stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells.90 The bio-mimicking processes made the liver buds self-packaging into a complex organ for transplanting into rodents. It functions well for metabolizing drugs.91

Some iPSC applications are advanced to clinical stages. For example, a group in Osaka University made “myocardial sheets” from iPSCs, transplanted them into patients with severe heart failure, the clinical research plan was approved in Japan,92 patients are under recruiting. Additionally, two men in China received iPSC-differentiated cardiomyocytes treatments.93 They were reported to be in good condition although no detailed data are revealed.93 iPSCs derived from skin cells from six patients are reprogrammed to retinal epithelial cells (RPCs) to replace degenerated RPCs in an ongoing phase I clinical trial.94 Similarly, phase I clinical trials are also undergoing for thalassemia treatment using autologous iPSCs differentiated hematopoietic stem cells,95 patients are recruiting. Till now, no Phase III study on stem cell-related therapy has been conducted. The major concern is the safety of iPSCs with the carcinogenic possibilities: teratoma has been observed in iPSCs injected mice,96 low-induction efficiency, incomplete reprogramming of genomes, immunogenicity and vector genomic integrations are also issues of concerns.97,98 More efforts are required for clinical applications.

Synthetic biology in tissue engineering

Tissue engineering aims to repair damaged tissues and restoring their normal functions. The use of synthetic biology in tissue engineering allows control of cell behaviors. Artificial genetic constructs can regulate cell functions by rewiring cellular signals. As engineered cells are building blocks in tissues with special properties to achieve smarter functions, synthetic biology allows complex tissue engineering for new medical studies.

By overexpression of functional genes or transcriptional factors, stem cells can differentiate to generate specific tissue cells successfully.99 This is a simple and common way in stem cell-based tissue engineering. However, the gene overexpression lacks feedback control mechanisms to avoid excess nutrient consumption or cell toxicity.100 For an instance, constitutive overexpression of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 leads to tumorigenesis risks.101,102 CRISPR/dCas9 bioswitches or synthetic mRNAs are found able to solve the problem via time and spatial-specific expression of genes.103,104 Moreover, introductions of genetic circuits sensing small molecules or cell-surface proteins are well studied, especially Tet repressor-based system.105 Gersbach et al. designed a Tet-off system controlling Runx2 factors that can regulate the in vivo osteogenic processes.106 Yao et al. employed a Tet-on system to express Sox9 specifically in engineered rat chondrocytes, Sox9 is a key factor maintaining chondrocyte viability, activating the protein expressions for type II collagen and aggrecan in cartilage tissue engineering.107 Chondrocyte degradation was inhibited after Dox (Tet system inducer) injection in implanted cell scaffolds.107 The Tet-on system is also used for overexpressing interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) gene to modulate inflammatory cytokines during the chondrogenesis processes in cartilage repairs108 (Table 2). Tet-switches have aided elapsed time controllable gene expressions for tissue engineering.

Table 2.

Synthetic biology in mammalian cell-based therapies

| Main features | Cell host /cell type | Genetic manipulations | Applications | Stages | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) | CD19-targeted CAR-T cancer immunotherapy | Patient’s own T-cells | The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) is composed of a murine single‐chain antibody fragment that recognizes CD19, fused to intracellular signaling domains from 4‐1BB and CD3‐ζ. | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma | Approved | 417 |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) | CD19-targeted CAR-T cancer immunotherapy | Patient’s own T-cells | Expressing a CAR comprising an anti‐CD19 single chain variable fragment linked to CD28 and CD3‐ζ costimulatory domains. | Diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma | Approved | 418 |

| Idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma) | B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed CAR-T cell therapy | Patient’s own T-cells | Comprises an anti-BCMA single-chain variable fragment (scFv) fused to a CD8 linker region, the 4-1BB co-stimulatory and the CD3‐ζ signaling domains | Relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma | Approved | 419 |

| SynNotch | An engineered Notch receptor to construct Multi-antigen prime-and-kill recognition circuits to induce effective proteins | Patient’s own T-cells | A synNotch receptor that recognizes EGFRvIII or MOG, induces expression of a CAR. | glioblastoma | Pre-Clinical | 56,420 |

| HEK-β cells | Engineering a synthetic circuit into human cells that can sense the glucose concentration and to correct blood sugar concentration | HEK-293 cells | Ectopic expression of a calcium channel, expression of insulin under control of elements of the calcium-responsive NFAT promoter, expression of both a short version of the glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1), a known insulin secretagogue, and its receptor (GLP1R). | Diabetes mellitus | Pre-Clinical | 70,421 |

| Caffeine-stimulated advanced Regulators (C-STAR) system | Sensing caffeine to produce peptides for treating diabetes | HEK-293T or hMSC-hTERT cells | Overexpression of T2D-treating peptide shGLP-1 under STAT3 promoter | Type 2 diabetes | Pre-Clinical | 422 |

| Guanabenz-controlled genetic circuits | Guanabenz activates the secretion of peptides GLP-1 and leptin. | Hana3A cells | The cTAAR1 signal transduction is rewired to dose-dependently control expression of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and leptin via an IgG-Fc linker under the induction of guanabenz. | The metabolic syndrome | Pre-Clinical | 423 |

| Green tea-triggered genetic control system | Engineering cells to respond to protocatechuic acid (PCA), a metabolite in green tea to treat diabetes in mouse and nonhuman primate models. | HEK-293 cells | Using PCA-ON sensor (artificial KRAB-PcaV fusion repressor) to overproduce insulin and shGLP-1 | Diabetes mellitus | Pre-Clinical | 424 |

| Synthetic optogenetic transcription device | Light-controlled expression of the shGLP-1 peptide to attenuate glycemic excursions in type II diabetic mice | HEK-293 cells | Overexpression of melanopsin; PNFAT-driven expression of shGLP-1 | Type 2 diabetic mice | Pre-Clinical | 425 |

| Red/far-red light-mediated and miniaturized Δphytochrome A (ΔPhyA)-based photoswitch (REDMAP) system | Small and highly sensitive light-inducible switch in mammalian cells | HEK-293 cells | The PhyA interaction domain FHY1 is fused to the VP64 to create a light-dependent transactivator (FHY1-VP64), the DNA-binding domain Gal4 is fused to phytochrome ΔPhyA to create a fusion light sensor domain (ΔPhyA-Gal4), the transactivator can bind to its synthetic promoter P5 × UAS to initiate transgene expression, following exposure to far-red light (730 nm), the transactivator terminates transgene expression. | Type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice and rats | Pre-Clinical | 387 |

| Gene expression by radiowave heating | Heating of iron oxide nanoparticles by radiowaves remotely activated insulin gene expression in cultured cells or mouse models | HEK-293T cells | Heated iron oxide nanoparticles activate TRPV1 channel to pump calcium, the insulin gene is driven by a Ca2+-sensitive promoter. | Lowers blood glucose in mice | Pre-Clinical | 192 |

| Electronic control of designer mammalian cells | Using wireless-powered electrical stimulation of cells to trigger the release of insulin | Human β cells | Coupling ectopic expression of the L-type voltage-gated channel CaV1.2 and the rectifying potassium channel Kir2.1 to the desired output through endogenous calcium signaling, the insulin gene is overexpressed by the system. | Type 1 diabetic mice | Pre-Clinical | 421 |

| Self-sufficient control of urate homeostasis | Senses uric acids levels and triggers dose-dependent derepression of a urate oxidase that eliminates uric acid | HeLa cells | The HucR start codon was modified (GTG→ATG) and fused to a Kozak consensus sequence for maximum expression, fusing it to the C terminus of the KRAB protein, eight tandem hucO modules downstream of the PSV40 promoter to drive the signal peptide-uricase cassette SSIgk-mUox. | Acute hyperuricemia in mice | Pre-Clinical | 426 |

| Dopamine sensors for hypertension control | A synthetic dopamine-sensitive transcription controller to produce the atrial natriuretic peptide to reduce blood pressure under pleasure situations | HEK-293 cells | Rewiring the human dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1) via cAMP to synthetic promoters containing cAMP response element-binding protein 1(CREB1)-specific cAMP-responsive operator modules to express atrial natriuretic peptide | Hypertension in mice | Pre-Clinical | 427 |

| Insulin self-regulation circuit for correcting insulin resistance | A self-adjusting synthetic gene circuit to reverse insulin resistance in diabetes and obesity animal models | HEK-293 cells | Ectopically express the human insulin receptor (IR) via the rewiring of the MAPK pathway, expression of adiponectin transgene (consisting of three tandem adiponectin molecules fused to a human IgG-Fc fragment), regulated by a synthetic promoter specific to the hybrid transcription factor TetR-ELK1 | Insulin resistance in mice | Pre-Clinical | 428 |

| Smartphone-controlled optogenetically engineered cells | Remotely control release of glucose-decreasing proteins by engineered mammalian cells implanted diabetic mice under the control of far-red light | HEK-293 cells | The bacterial light-activated c-di-GMP synthase BphS and the c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase YhjH are designed to regulate drug production according to user-defined glycemic thresholds. | Diabetes mellitus in mice | Pre-Clinical | 186 |

| Modified rapamycin-induced CAR-T cells | Engineered T cell “on” or “off” by administering small molecule rapalog | K562 cells | The part I constructs of the ON-switch are similar to conventional CAR, in addition to the FKBP domain for heterodimerization; part II variants contained the additional DAP10 ectodomain for homodimerization and the CD8α transmembrane domain for membrane anchoring. | Xenografted matched cancer cells | Pre-Clinical | 429 |

| Synthetic RNA regulatory systems for T-cell proliferation | Linking rationally designed circuit to growth cytokine targets to control mouse and primary human T-cell proliferation | CTLL-2 and TCM cells | Using tetracycline-responsive switches to inactivate ribozyme and cell-proliferation associated cytokines that are expressed to promote T-cell growth. | N.A. | N.A. | 430 |

| Nonimmune cell cancer therapies | A new class of synthetic T-cell receptor-like signal-transduction device to kill target cells | HEK-293T and hMSC cells | Employs JAK-STAT signaling mediated by the IL4 and IL13 receptor, with STAT6 as a signaling scaffold, and uses CD45-mimetic molecule upon specific cell contact as an OFF/ON switching mechanism. | N.A. | Pre-Clinical | 431 |

| PD-1 and CTLA-4 based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) | Designed antigen-specific inhibitory receptors to block these unwanted “on-target, off-tumor” responses. | Mice’s own T-cells | The cytoplasmic domain of CTLA-4 or PD-1 was fused to the human prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) transmembrane domain. | Leukemia in mice | Pre-Clinical | 432 |

| Resveratrol-triggered regulation devices in CAR-T cells | Allow precise control over T cell activity through adjustment of resveratrol dosage | Mice’s own T-cells | RESrep device consists of a resveratrol-dependent transactivator ResA3 that fused to a synthetic activator VPR via the C terminus of TtgR, the chimeric transactivator can bind to the resveratrol-dependent promotor PResA1, positioned in front of a promoter PhCMVmin. | Mouse tumor model of B cell leukemia | Pre-Clinical | 433 |

| CAR-transduced natural killer cells (CAR-NT) in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors | CD19-targeted CAR-NK cancer immunotherapy | HLA-mismatched anti-CD19 CAR-NK cells | NK cells were transduced with a retroviral vector expressing genes that encode anti-CD19 CAR, IL-15, and inducible caspase 9 as a safety switch. | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Phase 1 and 2 trial | 434 |

| CAR-macrophages (CAR-M) for solid cancer immunotherapy | CD19-targeted CAR-M cancer immunotherapy | Human macrophage THP-1 cells | First-generation anti-CD19 CAR encoding the CD3ζ intracellular domain, targeting the solid tumor antigens mesothelin or HER2 | Mice bearing SKOV3 lung or peritoneal metastases | Phase 1 | 435 |

| In vivo gene editing to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | CRISPR-Cas9 can correct disease-causing mutations in dog models of DMD. | Systemic delivery in skeletal muscle or vein | Using Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 coupled with a sgRNA to target a region adjacent to the exon 51 splice acceptor site to correct the skipping of exon 51 | Duchenne muscular dystrophy in dog | Phase 1 and 2 trial | 436 |

| In vivo gene editing to treat Leber congenital amaurosis 10 (EDIT-101) | Targeted genomic deletion using the CRISPR/Cas9 system for the treatment of mice and cynomolgus monkeys with LCA10 bearing the CEP290 splice mutation | Subretinal delivered in mice | A combination of specific pairs of sgRNAs and Cas9 to excise the intronic fragment containing the IVS26 splice mutation in CEP290 gene | Leber congenital amaurosis 10 in mice or cynomolgus monkeys | Phase 1 and 2 trial | 437 |

| CRISPR-edited stem cells to treat human diseases | Transplanted CRISPR-edited CCR5-ablated HSPCs into a patient for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with HIV-1 infection | Edited CD34+ cells | Cells were transfected with a ribonucleoprotein complex comprising Cas9 protein and two designed guiding RNAs targeting CCR5. | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient with HIV-1 infection | Clinical | 438 |

| Mammalian synthetic cellular recorders integrating biological events (mSCRIBE) | Recording of molecular events into mammalian cellular genomic DNA | HEK-293T cells | This device consists of a self-targeting guide RNA (stgRNA) that repeatedly directs Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 nuclease activity toward the DNA that encodes the RNA, when cellular sensors regulate the Cas9 activity, the device enabling localized, continuous DNA mutagenesis as a function of stgRNA expression. | N.A. | N.A. | 439 |

| Synthetic gene network for thyroid hormone homeostasis for Graves’ disease | A gene circuit that monitor increased thyroid hormone levels and drive the expression of a validated TSH receptor antagonist. | CHO-K1 cells | This synthetic control device consists of a synthetic thyroid-sensing receptor (TSR), a yeast Gal4 protein/human thyroid receptor-α fusion, which reversibly triggers expression of the TSHAntag gene from TSR-dependent promoters. | Graves’ disease in mouse models | Pre-Clinical | 440 |

| Aroma-triggered pain relief based on synthetic cell engineering | Spearmint (R-carvone) induced analgesic peptide production in mice | Hana 3A cells | Ectopic expression of the R-carvone-responsive olfactory receptor OR1A1 rewired via an artificial G-protein deflector to induce the expression of a secretion-engineered and stabilized huwentoxin-IV variant | Relief chronic pain in mice | Pre-Clinical | 441 |

| Synthetic gene circuit controls human IPSCs differentiation | Using vanillic acid as the inducer for cell-fate gene expressions in the transition of hIPSCs to beta-like cells | hIPSC cells | vanillic acid-triggered expression switches for the transcription factors Ngn3 and Pdx1 with the concomitant induction of MafA | N.A. | Pre-Clinical | 442 |

| Cytokine-induced anti-inflammatory factors to treat experimental psoriasis | Designed and engineered human cells that sequentially detected elevated TNF and IL22 levels from a psoriatic flare and produced therapeutic doses of IL4 and IL10. | HEK-293T cells | Rewired TNFR-signaling through NF-κB to a synthetic NF-κB-responsive promoter that controlled the expression of human IL22 receptor α which enables IL22-mediated activation of the JAK signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT signaling cascade, driving expression of the cytokines IL4 and IL10. | Psoriasis in mice | Pre-Clinical | 443 |

| Designer exosomes to deliver therapeutic cargo into brain (EXOtic devices) | The device enhances exosome biogenesis, packaging of specific RNAs into exosomes, secretion of exosomes, targeting, and delivery of mRNA into the cytosol of target cells to treat Parkinson’s disease. | HEK-293T cells | Overexpressing STEAP3, SDC4, NadB and Cx43 variant S368A, targeting CHRNA7 receptor | Parkinson’s disease in mice | Pre-Clinical | 444 |

| Genetic-code-expanded cell-based therapy for treating diabetes in mice | A genetic code expansion-based therapeutic system, to achieve fast therapeutic protein expression in response to cognate ncAAs at the translational level | HEK-293T cells | A ncAA-triggered therapeutic switch (NATS) system composed of a bacterial aaRS-tRNA pair and an insulin gene carrying an ectopic amber codon | Diabetes in mice | Pre-Clinical | 445 |

| Synthetic mammalian cell-based microbial-control device | Detects microbial chemotactic formyl peptides through a formyl peptide sensor (FPS) and responds by releasing AI-2 to inhibit pathogens | HEK-293T cells | A FPS module that detects formylated peptides by FPR1, the adapter protein Gα16 redirects receptor signaling to the Ca2+ transduction pathway, constitutively expressed 5′-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase MTAN cleaving endogenous SAH and the LuxS under the control of a Ca2+-responsive promoter to produce AI-2. | Inhibit Vibrio harveyi and Candida albicans | Pre-Clinical | 446 |

| Human liver buds | Self-packaging into a complex organ using three stem cells | iPSCs, endothelial stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells | N.A. | Generation of a functional human organ from pluripotent stem cells | Pre-Clinical | 90 |

| Reprogramming of cardiomyocytes drives heart regeneration | Uses of ex vitro cardiomyocytes for regeneration of fetal hearts to normal hearts by the Yamanaka’s method | Patient’s own cardiomyocyte cells | Cardiomyocytes specific expression of OSKM (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) is enabled by administration of doxycycline. | Heart failure in mice | Pre-Clinical | 89 |

N.A. not applicable

The optogenetic induction systems are also used in the control of cell behaviors in tissue engineering. Light inducible proteins are able to respond to UV and far-infrared lights, making light induction applicable.109 Various optogenetic circuits are constructed by fusing light-sensitive motifs to well-characterized transcriptional factors.110,111 Spatial-specific gene activation has been successfully employed to guide the arrangement of cells.112 Sakar et al. used blue light-induced channel rhodopsin-2 to achieve dynamic and region-specific contractions of tissues.113 The optogenetic control of engineered murine-derived muscle cells offers remote gene activation or silencing via the light-sensitive membrane Na+ channel and ion-inducible downstream elements for tissue engineering.

Inspired by successes of CAR-T cells, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are engineered to sense artificial ligands for tissue engineering.114 Park et al. successfully designed and used a GPCR sensing clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) in primary cells for the control of cell migration in response to CNO concentration gradients.115 This technology could make a valuable module for wound healing and cell regeneration. Synthetic biology makes possible to program cells to multicellular structures in a self-assembly manner.116 Toda et al. employed synNotch methods to engineer cell adhesion signals in a population of mouse fibroblasts that were turned into multilayers and polarized according to the synNotch receptor types.117

Besides cells, biomaterials are commonly used in tissue engineering, served as scaffolds and bio-mimicked organs.118 the auto-modulation characteristics of biomaterials in response to stimuli or chemical compounds are useful in biomaterial-based tissue engineering. Baraniak et al. engineered the B16 cell line with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter induced by RheoSwitch Ligand 1 (RSL1), which was coated on poly(ester urethane) films, allowing GFP activation for up to 300 days on the film.119 Deans et al. constructed an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG)-induced Lac-off system in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and IPTG encapsulated in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) scaffolds or PEG beads was released in a sustainable manner. The reporter gene indicated that the induction lasted over 10 days in mouse models implanted subcutaneously into the dorsal region,120 the GFP fluorescence level was observed to be controlled by its locations.121 The spatial-induced gene expression regulation has become a design-of-concept in many applications like cartilage repair and in vivo 3D cell scaffolds.

In summary, expressions of biological circuits could generate functionalized cells for tissue engineering. Multiple synthetic biology designs e.g. time and spatial-dependent gene expression, induction and autoregulation systems and smart biomaterials are available in this field. The state-of-the-art development still remains with many obstacles from moving truly synthetic tissues into clinic, but at least some foundations are settled for future studies.

Engineered bacterial cells for therapeutical applications

Synthetic biology approaches have promoted genetically engineered bacteria for novel live therapeutics (Fig. 2).122 Bacteria containing synthetic gene circuits can control the timing, localization and dosages of bacterial therapeutic activities sensing specific disease biomarkers and thus develop a powerful new method against diseases.123 Synthetic biology-based engineering methods allow to program living bacterial cells with unique therapeutic functions, offering flexibility, sustainability and predictability, providing novel designs and toolkits to conventional therapies.124 Here some advances are presented for engineered bacterial cells harboring gene circuits capable of sensing and transduction of signals derived from intracellular or extracellular biomarkers, also the treatments and diagnosis based on these signaling pathways. The concept of bacterial cell-based live therapeutics and diagnostics are rapidly growing strategies with promises for effective treatments of a wide variety of human diseases.

Engineered bacterial cells in cancer diagnosis and treatments

Some anaerobic/facultative anaerobic bacterial cells are good candidates for tumor treatments. They can target the anaerobic microenvironment of tumors, they also have the tumor lysis-inducing and trigger inflammation abilities useful in fighting against solid tumors.125 Engineered microbes can become suitable tools for cancer in vivo diagnosis. Danino et al. engineered E. coli with LacZ reporter gene, the bacterium produces LacZ when in contact with tumor cells. Subsequently, mice were injected with chemiluminescence substrates for LacZ (Table 3). The luminescence is enriched in the urine to generate red color.126 The method is more sensitive than microscopes as it can detect tumors smaller than 1 cm. Similarly, Royo et al. constructed a salicylic acid-induced circuit converting 5-fluorocytosine to toxic products in attenuated Salmonella enterica for tumor killing.127 Salmonella enterica localized in tumor tissues after the injection, with the additional providing of salicylic acid (inducer) and 5-fluorocytosine (substrate), tumor cells were eliminated via the formation of 5-fluorouracil from the bacterial cells.

Table 3.

Synthetic biology in microbe-based therapies

| Main features | Microorganism type | Genetic manipulations | Applications | Stages | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SYNB1020 | Transform ammonia into L-arginine to treat hyperammonia | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Deleted the gene argR, thyA and integrated the gene argA215, under the control of the fnrS promoter (PfnrS) | Hyperammonia in mice and cynomolgus monkeys | Phase 1b/2a | 150 |

| SYNB1618 | Engineered Escherichia coli Nissle to express genes encoding Phe-metabolizing enzymes to treat phenylketonuria | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Two chromosomally integrated copies of pheP and three copies of stlA under the regulatory control of PfnrS, two additional copies of stlA were placed under the control of the Ptac promoter. | Phenylketonuria | Phase 1/2 | 151 |

| Probiotic-associated therapeutic curli hybrids (PATCH) | Genetically engineer Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) to create fibrous matrices that promote gut epithelial integrity in situ | E. coli Nissle 1917 | CsgA fused to TFF3, under the control of an inducible promoter (PBAD) | Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis in mice | Pre-Clinical | 145 |

| Engineered bacteria for colorectal-cancer chemoprevention | The engineered Escherichia coli bound specifically to colorectal cancer cells and secreted myrosinase to transform small molecule form broccoli to anticancer agents. | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Expressed and secreted YebF-I1 myrosinase catalyzes the glucosinolate hydrolysis to sulforaphane, while the expression of INP-HlpA facilitates bacterial CRC cell binding. | Colorectal-cancer in mice | Pre-Clinical | 447 |

| Bacteria engineered to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease | Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced steatohepatitis | Lactobacillus reuteri | L. reuteri EF-Tu promoter drives murine IL-22 gene. | Ethanol-induced liver disease in mice | Pre-Clinical | 154 |

| Bacteria-mediated tumor therapy triggered via photothermal nanoparticles | Bacteria are coated with nanogold particles (or indocyanine green-loaded nanoparticles) able to receive light for heat generation, inducing therapeutic protein TNF-α in tumor sites. | E. coli MG1655/ attenuated Salmonella typhimurium | A widely used temperature-sensitive plasmid pBV220 containing TcI repression and tandem pR-pL operator-promoter was introduced to express human TNF-α. | Breast tumor in mice | Pre-Clinical | 448,449 |

| Engineered bacteria overexpressing anti-inflammatory cytokines | Therapeutic dose of IL-10 can be reduced by localized delivery of a bacterium genetically engineered to secrete the cytokine. | Lactococcus lactis MG1363 | lactococcal P1 promoter driving usp45 secretion leader fused to the mIL-10 gene. | Murine colitis | Pre-Clinical | 450 |

| Modified bacteria producing peptides to inhibit obesity | Engineered bacteria that express the therapeutic factor N-acylphosphatidylethanolamines (NAPEs) into the gut microbiota | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Overexpressing N-acyltransferase At1g78690 under the intrinsic promoter from Arabidopsis thaliana | Obesity in mice | Pre-Clinical | 149 |

| Synthetic genetic system to eliminate gut pathogens | A gene encoding an anti-biofilm enzyme induced by P. aeruginosa-specific quorum sensing signal | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Genes alr and dadX are deleted, the 3OC12-HSL-inducible promoter drives the expression of DspB and E7. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa gut infection in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice | Pre-Clinical | 146 |

| Bacteria synchronized for drug delivery | Engineer a clinically relevant bacterium to lyse synchronously and routinely at a threshold population density to release genetically encoded cargo | attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | The luxI promoter regulates production of autoinducer (AHL), which binds LuxR and enables it to transcriptionally activate the promoter, negative feedback arises from cell death that is triggered by a bacteriophage lysis gene (φX174 E) which is also under control of the luxI promoter. | Subcutaneous liver metastasis in mice | Pre-Clinical | 451 |

| Engineering bacteria to serve as whole-cell diagnostic biosensors | Sensing abnormal glucose concentrations in human urine samples | E. coli DH5α | Combinatorial of pCpxP and pYeaR promoters driving expression of integrase TP901 and BxB1 | Detection of urine glucose in human samples | Pre-Clinical | 135 |

| Engineered bacteria as live diagnostics of inflammation | Engineered a commensal murine Escherichia coli strain to detect tetrathionate, which is produced during inflammation. | E. coli strain NGF-1 | ttrR/S genes and the PttrBCA promoter from S. typhimurium to drive Cro expression, and inserted it into the genome, containing the phage lambda cI/Cro genetic switch can sense and record environmental perturbations. | Detection of gut inflammations | Pre-Clinical | 452,453 |

| Recording of cellular events over time using engineered bacteria | A multiplexing strategy to simultaneously record the temporal availability of three metabolites (copper, trehalose, and fucose) in the environment of a cell population over time. | E. coli BL21 | The E. coli cas1-cas2 cassette is downstream of the PLTetO-1 promoter, the CopA/GalS or TreR sensors drive RepL. | Recording specific environmental factors surrounding the cells | Pre-Clinical | 454 |

| Ingestible micro-bio-electronic device (IMBED) for in situ biomolecular detection | Heme-sensitive probiotic biosensors demonstrate accurate diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding in swine via miniaturized luminescence readout electronics that wirelessly communicate with an external device. | E. coli Nissle 1917 | The heme biosensor PL(HrtO), overexpressing HrtO and ChuA, luxCDABE was used as the output of the genetic circuit to generate luminescence captured by electronic devices. | Gastrointestinal bleeding in swine | Pre-Clinical | 455 |

| Probiotics detect and suppress cholera | Engineered an L. lactis strain that specifically detects quorum-sensing signals of V. cholerae in the gut and triggers expression of an enzymatic reporter that is readily detected in fecal samples. | L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 | Designed an L. lactis hybrid receptor that combines the transmembrane ligand binding domain of CqsS with the signal transduction domain of NisK, placed the gene tetR downstream of the chimeric repressor-controlled nisA promoter to enable constitutive repression of an engineered Bacillus subtilis xylA-tetO promoter. | Detection of cholera infection in mice | Pre-Clinical | 456 |

| Engineering probiotics for detection of cancer in urine | Orally administered diagnostic that can noninvasively indicate the presence of liver metastasis by producing easily detectable signals in urine. | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Genomic expression of luxCDABE, IPTG-inducible lacZ in plasmid | Indicate the presence of liver metastasis | Pre-Clinical | 126 |

| Underwater adhesives made by bacterial self-assembling multi-protein nanofibers | Fusing mussel foot proteins of Mytilus galloprovincialis with CsgA proteins | E. coli C3016 strain | Overexpression of the fused protein in E. coli | Novel bio-adhesive | N.A. | 248,250 |

| Engineered modularized receptors activated via ligand-induced dimerization (EMeRALD) to detect pathological biomarkers | Build EMeRALD receptor detecting bile salts in E. coli by rewiring bile salt-sensing modules from Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio parahaemolyticus | E. coli strain NEB10β | Synthetic bile acid sensor TcpP-TcpH for taurocholic acid; synthetic bile acid sensor VtrA-VtrC for taurodeoxycholic acid, driving sfGFP as the reporter | Detection of bile acid concentration in serum | Pre-Clinical | 457 |

| Kill tumor cells via salicylic acid-induced circuit | Salmonella spp., carrying an expression module encoding the 5-fluorocytosine-converting enzyme cytosine deaminase in the bacterial chromosome or in a plasmid, to mice with tumors | attenuated Salmonella enterica | Carries an expression module with a gene of interest (cytosine deaminase) under control of the XylS2-dependent Pm promoter | Eliminate xenografted tumor in mice | Pre-Clinical | 127 |

| Ultrasound-controllable engineered bacteria for cancer immunotherapy | Engineer therapeutic bacteria to be controlled by focused ultrasound to release of immune checkpoint inhibitors | E. coli Nissle 1917 | TcI42-containing thermal switch to express αCTLA-4 and αPD-L1 nanobodies in high temperature generated from the ultrasound | Eliminate xenografted tumor in mice | Pre-Clinical | 458 |

| Living bacterial polymer materials in gastrointestinal tract | Auto-lysis bacteria contain self-assembly materials to glue microbes up for stabilizing gut microbiota. | E. coli MC4100Z1 | Cells carrying the ePop circuit produce ELPs fused with either multiple SpyCatcher or SpyTag sequences | Maintain gut microbes under perturbations by antibiotics | Pre-Clinical | 459 |

| Ketone-producing probiotics as a colitis treatment | Develop a sustainable approach to treat chronic colitis using engineered EcN that can sustainably release 3-hydroxybutyrate | E. coli Nissle 1917 | The ldhA gene is knocked-out, phaB, phaA and tesB genes are overexpressed under fnrS promoter in the genome. | Acute colitis in mice | Pre-Clinical | 147 |

| Optotheranostic nanosystem for ulcerative colitis via engineered bacteria | Developed diagnosis and treatment kits containing two parts: the optical diagnosis sensor to smartphone processing and (ii) treatment based on optogenetic probiotics | E. coli Nissle 1917 | A light-responsive EcN strain containing light-inducing promoter pDawn to drive mil-10 gene for IL-10 production | Ulcerative colitis in mice | Pre-Clinical | 389 |

| SYNB1891 | Targets STING-activation to phagocytic antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the tumor and activates complementary innate immune pathways. | E. coli Nissle 1917 | The CDA-producing enzyme DacA from Listeria monocytogenes was expressed in EcN under PfnrS promoter, both dapA and thyA deleted in the genome. | Murine melanoma tumors and A20 B cell lymphoma tumors | Phase 1 | 460 |

| Bacterial flagellin triggered enhanced cancer immunotherapy | Engineered a Salmonella typhimurium producing the flagellin B protein from another bacterium Vibrio vulnificus to induce an effective antitumor immune response | S. typhimurium | relA and spoT genes were deleted in the genome, the pelB leader sequence was fused to the upstream of flaB to guide extracellular secretion, under the control of a PBAD promoter. | Mice colon tumors | Pre-Clinical | 461 |

| Quorum-sensing Salmonella spatial-selectively trigger protein expression within tumors | Integrated Salmonella with a quorum-sensing (QS) switch that only initiates drug expression in the tightly packed colonies present within tumors | attenuated Salmonella enterica | The pluxI promoter controls one operon consisting of genes encoding for proteins LuxR, GFP, and LuxI, LuxI produces the communication molecule 3OC6HSL. | Controlled therapy for mammary cancer in mice | Pre-Clinical | 462 |

| Tumor-specific lysis and releasing anti-cancer agents | Engineered a non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain to specifically lyse within the tumor microenvironment and release an encoded nanobody antagonist of CD47 | E. coli Pir1+ | A stabilized plasmid that drives constitutive expression of a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged variant of CD47nb, the strain overexpresses luxI and lyses at a critical threshold owing to the production of ϕX174E, resulting in bacterial death and therapeutic release. | Eliminating planted melanoma, mammary tumor in mice | Pre-Clinical | 463 |

| Engineered probiotics for regularly self-lysis to release nanobodies | Engineered a probiotic bacteria system to release nanobodies targeting the immune checkpoints | E. coli Nissle 1917 | The PD-L1nb and CTLA-4nb sequences were cloned onto separate plasmids downstream of a strong constitutive tac promoter on a high-copy plasmid, an HA protein tag was added to the 3′ end of the nanobody sequences. | Colorectal cancer and B cell lymphoma in mice | Pre-Clinical | 464 |

| Engineering of symbiont bacteria in mosquitos to control malaria | Serratia AS1 was genetically engineered for secretion of anti-Plasmodium effector proteins, and the recombinant strains inhibit development of Plasmodium falciparum in mosquitoes. | Serratia AS1 | The five effector genes were cloned in a single construct, (MP2)2-scorpine-(EPIP)4-Shiva1-(SM2)2, under the control of a single promoter. | Malaria prevention | N.A. | 465 |

| Engineered bacterial communication prevents Vibrio cholerae virulence | Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 to express the auto inducer molecule cholera autoinducer 1(CAI-1) to increase the mice’s survival in cholera infections | E. coli Nissle 1917 | Express the gene cqsA, under control of the native constitutive promoter PfliC | Prevents Vibrio cholerae virulence | Pre-Clinical | 466 |

| Noninvasive assessment of gut function: Record-seq | A CRISPR-based recording method (Record-seq) to capture the transcriptional changes that occur in Escherichia coli bacteria as they pass through the intestines | E. coli MG1655 | An anhydrotetracycline (aTc)-inducible transcriptional recording plasmid consisted of FsRT-Cas1–Cas2 and CRISPR arrays | N.A. | N.A. | 467 |

N.A. not applicable

To improve the effects of bacteria-based cancer therapies, some studies aim to further enhance bacterial tumor tropism.128 Some bacteria have natural affinity for the anaerobic environment of solid tumors, like E. coli or attenuated Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes.128 However, the affinity is not sufficient for targeted therapies, bacterial cells in vivo are still dispersed in general. They can be augmented by introducing synthetic surface adhesins targeted to bind cancer-specific molecules like neoantigens or other chemicals or proteins that are enriched in cancer cells, not accumulated in somatic cells. Engineering of adhesins are demonstrated to be effective in enhancing bacterial tumor reactions. The adhesins are membrane-displayed proteins with extracellular immunoglobulin domains that can be engineered via library directed evolution screens. Piñero-Lambea et al. constructed a constitutive genetic circuit in E. coli with an artificial adhesin targeting green fluorescent protein (GFP) as the evidence of a proof of concept, it demonstrated the abilities from that binding of the cell membrane-engineered bacteria to GFP-expressing HeLa cells are successful both in vitro and in mice.129 Importantly, the intravenous delivery of this engineered bacteria to mice resulted in effective and efficient colonization in xenografted solid tumors of HeLa cells at a dose 100 times lower than that for a bacterial strain expressing an irrelevant control adhesin, or for the wild-type strain, suggesting that similarly engineered bacteria can be used to carry therapeutic agents to tumors at low doses with marginal potential systemic basal toxicities.130,131 However, few tumor-targeting bacteria have entered clinical stages. The facultative anaerobe Salmonella typhimurium VNP2000, has been engineered for safety with anti-tumor abilities in pre-clinical studies,132 yet it failed in the phase I clinical trial for marginal anti-tumor effects and dose-dependent side effects.133 Some other clinical investigations based on bacteria Clostridia novyi-NT or Bifidobacterium longum APS001F are ongoing or recruited for their phase I trials.134

Engineered bacterial cells for diabetes diagnosis and treatments

Bacteria have been engineered to detect glucose concentrations for diabetes. Courbet et al. described an approach in sensing abnormal glucose concentrations in human urine samples.135 They encapsulated the bacterial sensors in hydrogel beads, glucose in urine will change the color to red in beads. The in vitro bacterial glucometer has found outperforming the detection limit of urinary dipsticks by one order of magnitude.

Some proteins and peptides are biosynthesized in engineered gut bacteria for diabetes treatments. The engineered probiotic L. gasseri ATCC 33323 produced GLP-1 protein, the bacterium is orally delivered to diabetic rats,136 demonstrating a down-regulation of blood glucose levels to 33%. Similarly, engineered L. lactis FI5876 was reconstructed to biosynthesize and deliver incretin hormone GLP-1 to stimulate β-cell insulin secretion under conditions of high glucose concentrations. Results showed the glucose tolerance is improved in high-fat diet mice.137 The probiotic L. paracasei ATCC 27092 is engineered to secret angiotensin (1-7) [Ang-(1-7)], increasing the concentrations of Ang-(1-7) (an anti-inflammatory, vasodilator and angiogenic peptide phamarceutical), and reduced the side effects on retina and kidney in diabetic mice, as the insulin production level is increased after oral administration of the bacteria. Following the design, oral uptake of engineered B. longum HB15 which produces penetratin (a cell-penetrating peptide with the ability of enhancing delivery of insulin), and GLP-1 fusion protein also enhanced the production of GLP-1 in the colorectal tract.138–140 L. paracasei BL23 was also successfully designed to produce monomer GLP-1 analogs displayed to the bacterial membrane via fusing GLP-1 to peptidoglycan-anchor protein PrtP, the engineered bacteria enhanced glycemic control in rats with diabetes. However, the efficacy is still limited and needed further investigations.141 In addition to GLP-1, some other proteins like the immunomodulatory cytokine IL-10 along with human proinsulin were simultaneously introduced to engineered L. lactis MG1363, the combination therapy with low-dose systemic anti-CD3 allowing reversal of irregulated self-autoimmune triggered diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice.142,143 This design could possibly be effective for the treating of type 1 diabetes in human.

Engineered bacterial cells for diagnosis and treatments of gastrointestinal diseases

Probiotics can be used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).144 IBD is chronic inflammation of tissues in the digestive tract, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Patients are suffering from diarrhea, pain and weight loss. Synthetic biology approaches and ideas help bacteria acquire more powerful abilities against gastrointestinal diseases. Praveschotinunt et al. designed an engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) that produces extracellular fibrous matrices to enhance gut mucosal healing abilities for alleviating IBD in mice.145 Curli fibrous proteins (CsgA) were fused with trefoil factor (TFF) domains to promote the reconstruction of cell surface, and the bacterium could produce fibrous matrices via the in situ protein self-assembly of the modified curli fibers. The results revealed that the designed EcN significantly inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, alleviated the weight loss of mice, maintained colon length, demonstrating its anti-inflammation ability in the dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced acute colitis mouse model. The design could be expanded to a general approach for probiotic-based live therapeutics in IBD treatments.

Bacteria are feasible to be engineered to directly eliminate pathogens for preventing infectious diseases in gastrointestinal tracts. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common multidrug-resistant pathogen difficult to treat. Engineered EcN has been employed for the detection, prevention and treatment of gut infections by P. aeruginosa.146 The designed EcN was able to sense the biomarker N-acyl homoserine lactone produced by P. aeruginosa, and autolyzed to release a biofilm degradation enzyme dispersin and pyocin S5 bacteriocin to eliminate the pathogen in the intestine. Moreover, the reprogrammed bacteria displayed long-term (over 15 days) prophylactic abilities against P. aeruginosa and was demonstrated to be more useful than treating a pre-established infection in mouse models. 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3HB) is a component of human ketone bodies with therapeutic effects in colitis. Yan et al. constructed an EcN overexpressing 3HB biosynthesis pathway.147 Compared to wild-type EcN, the engineered E. coli demonstrated better effects on mouse weights, colon lengths, occult blood levels, gut tissue myeloperoxidase activity and proinflammatory cytokine concentrations.147 However, the studies are the preliminary results in mice, they have not reached clinical trials yet. Further efforts are needed to evaluate their applications in human.

Engineered bacterial cells for metabolic disorders

Engineered gut microbes also have been used to target metabolic disorders.148 E. coli was designed to treat obesity synthesizing anorexigenic lipids precursors in mice with high-fat diet.149 Some efforts are made to degrade toxic compounds accumulated in patients via live bacteria. Kurtz et al. engineered an E. coli Nissle 1917 strain for converting ammonia to L-arginine in the intestine and reducing systemic hyperammonemia in both mouse and monkey models.150 Isabella et al. reprogrammed E. coli Nissle 1917 to overexpress phenylalanine degradation pathway to metabolize excess phenylalanine in phenylketonuria (PKU) patients. In the Pahenu2/enu2 PKU mouse model, oral uptake of the engineered bacterium significantly down-regulated blood phenylalanine concentration by 38%.151

Alcoholic liver disease is the major cause of liver disorders, widely risking the health of heavy drinkers.152 The engineered Bacillus subtilis and L. lactis could be employed to express ethanol degradation pathway (alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase) for the detoxification of alcohol and alleviate liver injury from alcohol overconsumption.153 Moreover, the lectin regenerating islet-derived 3 gamma (REG3G) protein is decreased in the gastrointestinal tract during chronic ethanol uptake. L. reuteri was designed to overexpress the interleukin-22 (IL-22) gene, which increased REG3G abundance in the intestine, reduced inflammation and damage in liver using an alcoholic liver disease mouse model.154

Synthetic biology approaches have allowed the construction and design of engineered live biotherapeutics. Many cases are targeting future clinical applications. The examples discussed here indicate that, with the development of circuit designs and understanding in microorganism hosts, researchers can construct live biotherapeutics that function in a precise, systematic, inducible and robust manner. However, many efforts are still needed to weaken bacterial toxicity and increase the controllability in vivo.

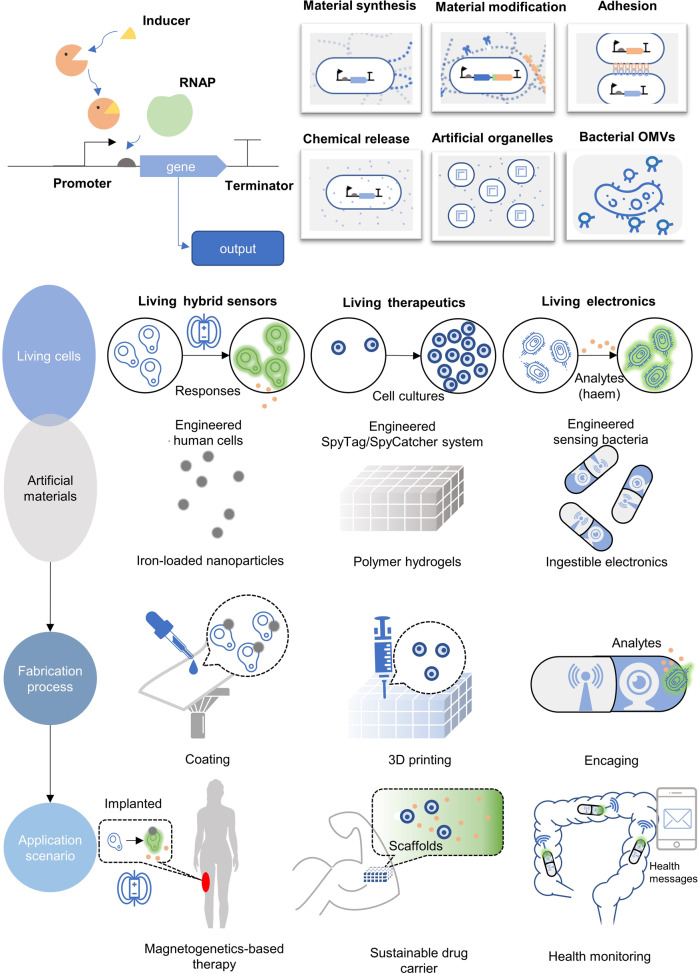

Synthetic biology in the fabrication of emerging therapeutic materials

Besides engineered cells, engineered nanomaterials are also commonly used in medical fields. Nanobiotechnology aims to solve important biological concerns similar to drug delivery, disease diagnosis and treatment based on its unique physical, chemical and biological properties of micro-nano scale materials155,156 (Fig. 4). Nanomaterials possess unique mechanical, magnetic and electronic properties, able to respond to external signals, controlling their downstream circuits.157 However, traditional nanomaterials are generated from physical and chemical processes, the solvents and modifying molecules are frequently causing bio-safety issues.158 Recently, biological nanomaterials have been developed exhibiting their advantages in environmentally friendly, enhanced biocompatibility and bioactivity, and low tissue toxicity under the guidance of synthetic biology.159 Based on synthetic biology concepts and approaches, the genetic engineered bacteria,160 yeast161 and tobacco mosaic virus162 (TMV) can serve as bio-factories for nanomaterials.163 Mammalian cell-derived vesicles and nanoparticles have suitable biocompatibility, also commonly used as nanomedicines.164 Biological materials can be constructed and engineered with the help of synthetic biology, extending their application scenarios in modern disease treatments.

Fig. 4.

The designs and applications in synthetic material biology. Generally, a genetic circuit is constructed to synthesize biological materials or sense environments. The engineered bacteria are endowed with new characteristics like color change and unique surface properties. The applications for cells with excellular matrices are diverse including magnet field induced therapies, development of novel drug carrier or health monitoring via sophiscated biofabrication processes. This figure is partially inspired by the paper469

Synthetic biology in the artificial organelles

Following the principles of synthetic biology, biocatalysis or trigger-sensing modulus nanoparticles can be processed to self-assembly organelles,165,166 which are biomimicry of characteristics of living cells like enzyme reaction compartmentalization and stimuli-responses (Fig. 4). The design also provides new inputs for constructing artificial cells.167 Additionally, combinations of artificial organelles and engineered living cell chassis including CAR-T cells and engineered bacteria, the nano-living hybrid system can exert its dual effects to enhance therapeutic results or more strictly control of artificial systems.

Polymersomes are artificial hollow vesicles made by amphiphilic polymers, using as shells of artificial organelles. van Oppen et al. employed a polymersome-based system that was anchored with cell-penetrating peptides on its outer membrane. The artificial organelles possess inside catalase, allowing degradation of external reactive oxidative molecules, perform as a synthetic organelle, protecting the cells from ROS damages triggered via H2O2, which showed abilities in uptaking by human primary fibroblasts and human embryonic kidney cells.168 A similar design relying on polymersomes equipped with two enzymes and related transmembrane channels, was used to mimic cell peroxisomes. These organelles were able to deal with both H2O2 and superoxide radicals. The results further demonstrated the feasibility of artificial organelle with catalase activity. Based on similar ideas, engineered polymersomes may play a role in treating medical conditions including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, metabolic diseases, cancers and acatalasemia via harboring various therapeutic proteins inside of the artificial organelles.169,170

Moreover, the fusion of nanobiotechnology and synthetic biology may achieve novel functions. First, researchers can create “artificial lives” via assembling nanoparticles following the “bottle-up” principle. The idea can be applied in constructing biological components using inorganic scaffolds and functional nanomaterials with nucleic acids and protein inside of the nanoparticles.171,172 The “top-down” principle, or engineering natural cells for actual demands, can be used as a guidance when using nanomaterials in living cells for chimeric biological systems to increase the robustness, stability and sensitivity in specific medical applications.

Constructing nanoparticle-mediated genetic circuits

Auto-responses can be achieved via internal environmental stimulus to induce genetic switch ON/OFF173 (Fig. 4). However, the irreversible situation of genetic switches is a common and difficult problem.174,175 To circumvent the weakness of genetic constructs, nanoparticles are employed to sense signals for the transductions in vivo. Light, sound, heat and magnet stimuli are easy to respond for nanoparticles, they can be used as inducer systems for solid tumor and diabetes treatments. Yet the spatial-specific induction is hard for physical stimulus.176 Overall, via combining the advantages of genetic sensor and nanoparticles, it is feasible to convert physical stimuli into genetic switch with specified input signals by introducing nanoparticles for signal transduction, and the time-spatial control of gene expressions are realized.177