Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this review was to explore the impact of living with undiagnosed ADHD and adult diagnosis on women.

Method:

A systematic literature search was completed using three databases. Eight articles were considered relevant based on strict inclusion criteria. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the results of the articles.

Results:

Four key themes emerged: Impacts on social-emotional wellbeing, Difficult relationships, Lack of control, and Self-acceptance after diagnosis.

Conclusion:

This knowledge can be used to advance the understanding of ADHD in adult women and the implications for late diagnosis in women.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, women, gender, gender gaps, diagnosis

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was once thought to be a male only disorder, leaving women and girls to suffer in silence (Nussbaum, 2012). In childhood, the ratio of boys to girls with ADHD is about 3:1 whereas in adulthood it is closer to 1:1, suggesting that women and girls are underdiagnosed in childhood (Da Silva et al., 2020). ADHD is one of the most common psychiatric disorders in childhood and can result in cognitive difficulties and functional impairments (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Without a diagnosis, women with ADHD often report spending their lives feeling “different,” “stupid,” or “lazy” and blaming themselves for their underachievement (Lynn, 2019). Consequently, receiving a diagnosis of ADHD can be instrumental for a woman’s self-esteem and identity (Waite, 2010). Many women experience diagnosis as a lightbulb moment, giving an external explanation for their struggles and allowing them to accept themselves more fully (Stenner et al., 2019).

ADHD is a manageable condition; early detection and treatment can dramatically change the outcomes for children with ADHD as they continue into adulthood (Quinn, 2004). Early intervention can reduce academic and professional underachievement, relationship difficulties, and psychiatric comorbidities (Sassi, 2010). Research has consistently shown that females are underdiagnosed in childhood (Mowlem et al., 2018; Quinn, 2004; Waite, 2010); however, there is little research looking at the impact of this underdiagnosis. The current review examines adult ADHD diagnosis in women and the impacts of living undiagnosed until adulthood.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD is a developmental disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate and impairing symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (APA, 2013). There are three main presentations of ADHD, dividing symptoms into classifications of inattention, hyperactive-impulsive, or a combination of the two (APA, 2013). Presentations will manifest differently for each individual and will look different from person to person. ADHD is a disorder prevalent in 5% to 10% of school aged children (APA, 2013). It persists into adulthood and affects both men and women (Da Silva et al., 2020), impacting 2% to 6% of the global population (Song et al., 2021).

Gender & ADHD

Societal norms and values play an important role in how people with ADHD perceive themselves and how they are perceived by others, with society’s prevailing norms influencing what is considered appropriate behavior (Holthe, 2013). These norms differ based on gender (i.e., the social meaning attached to biological sex); women and girls are encouraged to display “feminine” behaviors and traits such as empathy, good relationships with others, organization, and obedience (Holthe, 2013). When girls display behaviors consistent with ADHD symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, hyperactivity, and disorganization), they are at a higher risk for social judgment for violations of feminine norms (Holthe, 2013). To avoid social sanctions, many girls with ADHD exert considerable effort to mask symptoms of ADHD (Waite, 2010).

ADHD symptoms present differently in girls and boys (Mowlem et al., 2018; Nussbaum, 2012; Quinn, 2004). Girls are more often diagnosed with ADHD-Inattentive (ADHD-I), exhibiting symptoms such as distraction, disorganization, and forgetfulness (Nussbaum, 2012). Boys more frequently present with ADHD-Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (ADHD-HI), exhibiting greater levels of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and aggression (Waite, 2010). These symptoms are often more disruptive in the classroom setting, leading to higher rates of referral for assessment in boys than girls (Waite, 2010). Mowlem et al. (2018) found that a clinical diagnosis of ADHD was more common in boys than girls; of the children in their study, 72% of those who had a clinical diagnosis of ADHD were boys. An additional 12.9% met the symptom criteria for ADHD but did not have a formal diagnosis. Of these additional undiagnosed participants, 64% were boys and 36% were girls, suggesting gender differences in rates of diagnosis as well as diagnostic criteria. Externalizing behaviors are a stronger predictor of diagnosis in girls than boys. Girls who display significant externalizing behaviors are more likely to receive a diagnosis than those who display internalizing symptoms, suggesting that girls may be more likely to be missed in the diagnostic process unless they have significant externalizing behaviors (Mowlem et al., 2018). Findings suggest that the current diagnostic criteria and/or clinical practice is biased toward the male presentation of ADHD (Mowlem et al., 2018).

Not surprisingly, males are diagnosed with ADHD at higher rates than females (Mowlem et al., 2018). One potential reason for this differential rate of diagnosis is that physicians may lack knowledge of gender differences in ADHD, leading to overlooked or missed diagnoses for women and girls (Quinn, 2008). Many women seeking treatment for mood and emotional problems may have unrecognized ADHD (Quinn, 2008). Higher rates of comorbidities such as depression and eating disorders in females with ADHD may make diagnosis more difficult. As well, physicians may have more difficulty separating ADHD from its comorbidities, potentially clouding ADHD symptoms and leading to delayed diagnosis in females (Quinn, 2008).

Additionally, the reason for referral for ADHD services differs among males and females. Males are more often referred due to behavioral symptomology (e.g., ADHD), whereas females are more often referred due to emotional issues, such as anxiety or depression (Klefsjö et al., 2021). Klefsjö et al. (2021) found that girls had more visits to a psychiatric care facility prior to ADHD diagnosis, were prescribed non-ADHD medications (e.g., anti-depressants) before and after diagnosis at a higher rate, and were older than boys at time of referral and at age of diagnosis. They suggest that this difference may be due to the higher burden of emotional problems required for girls to be referred for treatment. Girls are often less noticed by teachers and parents until symptoms are causing significantly more impairment than required for recognition in boys (Klefsjö et al., 2021).

Mowlem et al. (2018) found that females referred for and diagnosed with ADHD exhibited symptoms that were a significant deviation from their typical behaviors, suggesting that females may have a slightly higher threshold for symptom severity for referral and diagnosis. Females with more externalizing symptoms were also referred more often, suggesting that because externalizing disorders are not in line with what is considered normative for females, they are more easily recognized and referred for assessment than those with internalizing symptoms on their own.

Gender bias not only occurs in clinical settings but also in the perceptions of parents and teachers, which may impact the rate in which males and females are referred for treatment. Ohan and Visser (2009) asked parent and teacher participants to read a vignette describing a child displaying symptoms of ADHD. Vignettes did not differ, other than half of participants read a vignette describing a child with a male name and the other half read a vignette describing a child with a female name. Participants were then asked to rate their likeliness to recommend or seek services for the child described. Both teachers and parents were less likely to seek or recommend services for girls than boys in these vignettes.

There is also gender bias in the research informing diagnostic criteria. Hartung and Widiger (1998) examined 243 empirical studies published in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology over the 6-year period between publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) DSM-III-R (1987) and the publication of the DSM-IV (1994). Seventy of those studies concerned ADHD, with 81% of participants being male and only 19% female. Other studies looked at in this review also found gender bias in participants; of 243 studies that stated participant gender, 71% included both boys and girls and 29% (70 studies) were confined to one sex. Of these 70 single-sex studies, 99.6% were studies of male children.

Diagnosis

ADHD is not the only disorder where women are underdiagnosed. Research on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has found that women are commonly undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. This inaccurate diagnosis may be due to diagnostic criteria being developed primarily on the behavioral presentation of males (Green et al., 2019). Gender influences diagnostic processes in both mental and physical health settings; for example, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for women worldwide yet due to differences in symptom presentation and underrepresentation of females in clinical trials, women are more likely to experience delays in diagnosis, be treated less aggressively, and have worse outcomes than men (DeMarvao et al., 2021). Receiving a diagnosis can be a central part of an individual’s identity. Individuals suffering from mental illness not only experience symptoms, but also interpret their experience of having a diagnosed condition. Assigning meaning to diagnosis can affect hope and self-esteem (Yanos et al., 2010), while receiving a diagnosis provides an individual with a model in which to compare themselves and can help them to form their identity. Diagnosis can help an individual make sense of their past and relieve uncertainty (Schmitz et al., 2003).

Women With ADHD

There are several key characteristics specific to the expression of ADHD in women as compared to men. These characteristics include differences in symptom presentation, decreased self-esteem, more difficulty in peer relationships, increased likelihood of anxiety and other affective disorders, the development of coping strategies that mask symptoms of ADHD, and gender based societal expectations (Quinn & Madhoo, 2014). Women are more likely to present with inattentive symptoms than hyperactive symptoms, which may be less easily noticed and less likely to trigger a referral for diagnosis (Williamson & Johnston, 2015). As well, women are often diagnosed with, and treated for, a comorbid condition before being recognized as having ADHD. Quinn (2005) found that 14% of girls with ADHD were prescribed antidepressants before being treated for ADHD compared to only 5% of boys. Robison et al. (2008) looked at gender differences in ADHD symptoms, psychological functioning, physical symptoms, and treatment response. They found that women were rated as more impaired on every measure of ADHD symptoms. Women were also found to score higher on rating scales for anxiety and depression as well as experienced greater emotional dysregulation compared to men.

Women with ADHD are also at a higher risk of engaging in risky sexual behavior, unplanned pregnancy, and are more likely to be coerced into having sex than women without ADHD (Young et al., 2020). Social stigma around risky sexual behavior, particularly for females, may increase social problems and limit occupational opportunities (Young et al., 2020). Low self-esteem is common among women with ADHD and, in combination with social stigma and risky sexual behaviors, may leave women with ADHD more vulnerable to sexual harassment, exploitation, and abusive or inappropriate relationships (Young et al., 2020). Additionally, societal and cultural expectations often put the bulk of household and parental duties on women and the demands placed on mothers often differ from demands placed on fathers (Young et al., 2020). Increased expectations placed on women and mothers may result in increased impairment and anxiety in women with ADHD. Low self-esteem in combination with these demands may result in dysfunctional beliefs such as perceived failure, guilt, and feelings of inadequacy (Young et al., 2020).

For many women, the process of receiving a diagnosis and treatment for ADHD is not straightforward. Many women begin the process of getting a diagnosis after their child has been diagnosed with ADHD, while others may begin this process by seeking treatment for other comorbid conditions (Stenner et al., 2019). Many women also self-diagnose as having ADHD; this self-identification is another important way in which women come to identify as having ADHD. For many women, ADHD falls under the category of “illnesses you have to fight to get” (Stenner et al., 2019, p. 181). Women often feel they need to prove symptoms for a physician to take them seriously and consider a diagnosis of ADHD (Stenner et al., 2019).

Comorbidities

ADHD in both men and women is often accompanied by one or more comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance use (Quinn, 2004). These comorbidities can often complicate the assessment of ADHD, as physicians tend to treat comorbid conditions first and sometimes overlook the diagnosis of ADHD completely (Quinn, 2004). Comorbidities are often different for females with ADHD compared to males (Quinn, 2008). Rucklidge and Tannock (2001) found that when comparing females with ADHD to males with ADHD, females were more psychosocially impaired than males. Females reported more overall distress, anxiety, and depression, as well as a greater external locus of control. They found that the combination of having ADHD and being a female may put an individual at higher risk for psychological distress. When Fuller-Thomson et al. (2016) compared women aged 20 to 39 years with ADHD to women without ADHD, they found that the women with ADHD had twice the prevalence of substance abuse, current smoking, depressive disorders, severe poverty, and childhood physical abuse as well as triple the prevalence of insomnia, chronic pain, suicidal ideation, childhood sexual abuse, and generalized anxiety disorder compared to women without ADHD. Biederman et al. (2006) compared girls with ADHD to girls without ADHD over a 5-year period. ADHD was associated with a significantly increased lifetime risk of major depression, multiple anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, Tourette’s/tic disorders, enuresis, language disorder, nicotine dependence and drug dependence. Results from this study show that at a mean age of 16 years, girls with ADHD are at a very high risk for antisocial, mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders. Biederman et al. (2006) stress the importance of early intervention and prevention strategies for girls with ADHD considering the high morbidity associated with ADHD in females found in their study.

Current Study

The present study intends to consolidate the literature on adult ADHD diagnosis in women. A systematic review identifying, appraising, and synthesizing the literature on this topic is needed to produce a complete interpretation of the findings. A deeper understanding of the experience of adult diagnosis and its implications in women is needed. Uncovering and identifying broad themes within the literature may provide a narrative of the experiences of adult diagnosis and their associated outcomes for women.

Methods

Literature Search

Using a university digital library, three databases were searched for relevant abstracts: Google Scholar, PsycINFO, and PubMed. Studies were identified using the following search terms across all databases: ADHD (ADHD OR Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) AND women (OR females) AND diagnosis (OR late diagnosis OR adult diagnosis) AND health outcomes (OR psychosocial outcomes) AND adult (in title and abstract) AND mental health, as well as adult ADHD diagnosis (in title and abstract), ADHD diagnosis in girls, adult ADHD diagnosis in women, women with ADHD, specific issues women with ADHD, implications of adult ADHD diagnosis in women, psychosocial outcomes of women diagnosed with ADHD as adults. Literature searches were conducted across the three separate databases and reference lists of included articles were reviewed for additional papers fitting inclusion criteria.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they (1) were published after 1997, (2) were written in the English language, (3) focused on women over the age of 18 who received a diagnosis of ADHD in adulthood, (4) were peer reviewed, and (5) had available full text. Conversely, studies were excluded if they (1) were case studies, (2) included individuals diagnosed with ADHD in childhood, and (3) focused on medication treatment for ADHD. Case studies were excluded as they were not considered to be generalizable to the experience of women with adult ADHD. Studies with participants diagnosed in childhood were excluded as the focus of the review was to understand the impacts of an ADHD diagnosis made in adulthood. Additionally, ADHD treatment was not the focus of the present review.

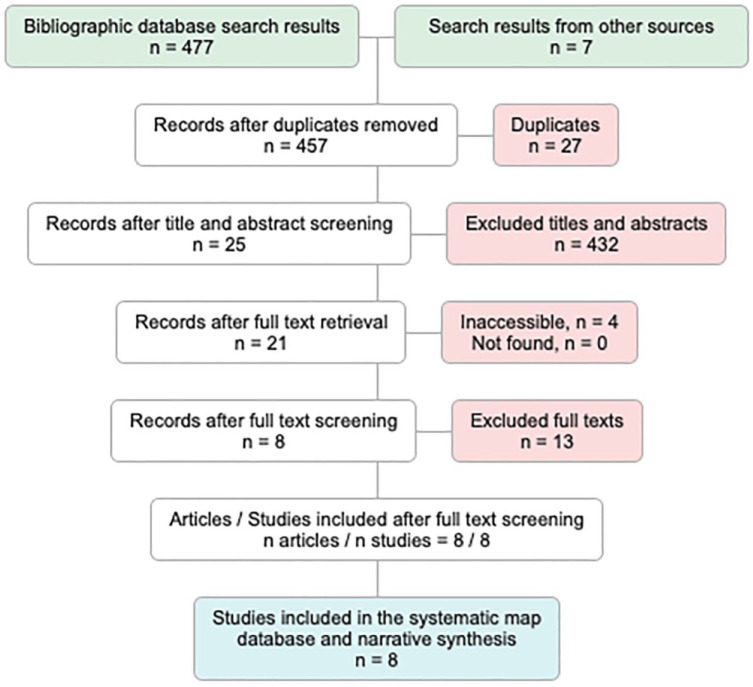

Study Selection

A flow chart created by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) was used to visually track the number of articles at each step in the review process (see Figure 1). The initial search of Google Scholar resulted in 108 results, the search of PsycINFO resulted in 118 results, and the search of PubMed resulted in 251 results. Seven additional articles were included from reference searches through relevant articles. A combined total of 484 articles were found. These records were screened, and 27 duplicates were removed leaving 457 articles. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance leaving 25 articles. Four articles were inaccessible, 21 articles were retrieved for full text screening. After full text screening, 13 articles were excluded for a final total of eight articles (see Appendix A).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Note. From top to bottom, numbers represent articles included after each deduction.

Data Analysis

Using the techniques of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) each study was closely examined to identify significant statements and results, including identifying common significant statements and potential codes. Key words and phrases were identified in the texts as significant if they were repeated by multiple participants and clearly described the experience of receiving a diagnosis of ADHD as an adult woman. Significant statements were compared across studies to compile a list of initial codes (See Appendix B). Studies were then examined with the list of preliminary codes to identify any statements or findings that fit within the codes. Once all articles had been coded with the preliminary coding scheme, codes were grouped by similarities and following, potential themes were identified. The list of codes themes was then reviewed and refined by other members of the research team.

Positionality Statement

In qualitative research, it is important to consider the position of the researcher and any potential bias that may be introduced. There is potential for bias in the process of selecting studies for the final review. To mitigate potential biases in study selection the researcher used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) flow diagram (See Figure 1) to ensure a systematic method of study selection. The first author of this paper identifies as a woman with ADHD; as such, the researcher may have had a priori assumptions about the experiences of women with ADHD diagnosed in adulthood. These assumptions may introduce the potential for bias in the interpretation of results. To reduce the potential for researcher biases to influence interpretation of data, codes and themes, the researcher utilized an inductive approach to coding deriving codes and themes directly from the studies as opposed to using a coding scheme. The researcher also used an iterative coding process reviewing codes and themes multiple times, reviewing these with the project supervisor and revising as needed.

Results & Discussion

This review consolidated the literature to summarize the current understanding of adult ADHD diagnosis in women. Using techniques of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), eight articles were reviewed. The results of each article were broken down into smaller units of meaning (codes), which were then grouped into categories forming themes. Four major themes emerged, focused on the impacts on social emotional wellbeing, difficulty in relationships, feeling out of control, and self-acceptance after diagnosis.

Theme 1: Impacts on Social-Emotional Wellbeing

Negative impacts on social-emotional wellbeing were a main finding of all eight papers in this review. Social-emotional wellbeing affects several aspects of an individual’s life, such as the ability to form close, secure, and meaningful relationships, experience, regulate and express emotions, and explore the environment and learn new skills (Cohen et al., 2005).

These results suggest women with adult ADHD may experience significant difficulties in various aspects of social emotional functioning, such as self-esteem, peer relations, and emotional control (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Rucklidge (1997) noted that women with ADHD reported having more depressive episodes, were treated more times by a mental health professional, had lower self-esteem, higher stress, and higher anxiety than women without ADHD.

Low Self Esteem

Women with undiagnosed ADHD may have notably low self-esteem and self-efficacy (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Undiagnosed ADHD can have profound impacts on self-esteem and feelings of self-worth; for example, when referring to her childhood one woman reported “what I felt was I was actually a bad person. . . I was not an adequate human being.” (Stenner et al., 2019, p. 191). Lacking a better explanation, perceived personal flaws could become the reason for academic, social, and emotional struggles, resulting in self-blame and a negative self-image (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Results suggest women with undiagnosed ADHD often endure childhoods filled with misunderstanding, self-blame, and rejection (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For these women, low self-esteem might be the result of difficulties endured growing up with an undiagnosed disorder that neither they nor those around them understood (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). They can struggle with negative automatic thoughts, feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). They often report negative automatic thoughts such as, “what’s wrong with you,” “you’re a failure,” and “I hate myself and I want to die” (Lynn, 2019, p. 39). They may experience shame and frustration when comparing themselves to their peers and could feel that they are not living up to the expectations they set for themselves or the expectations of society (Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019). Findings indicate that these negative feelings can result in low self-esteem, increased anxiety, and self-loathing. With no external cause to attribute functional impairments to, women in these studies often felt there was something personally wrong with them (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Social Relations and Emotional Control

The studies indicate that women with ADHD had significant difficulties in social relations, emotional control, and identity formation (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Stenner et al., 2019). Studies suggested that women with ADHD lacked value for themselves, had little to no self-worth, experienced feelings of inadequacy and weakness, and felt that their lives were filled with missed opportunities (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Many women in these studies felt “different” and alienated in childhood and expressed difficulties relating to their peers (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Stenner et al., 2019). Holthe (2013) found that women with ADHD had problems picking up on social cues, felt awkward and out of place socially, and struggled with unintentionally saying things that were considered hurtful or inappropriate. These women experienced peer rejection, bullying and difficulty making friends; for example, one participant stated, “I cried all the time, very lonely, very sad, being on my own and almost the voice inside my head was my only friend” (Stenner et al., 2019, p. 190).

Anger issues, poor emotion regulation and a fear of losing self-control were also main findings (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Stenner et al., 2019); one participant stated “there’s a lot to ADHD, like anger. I have a lot of anger issues, and problems controlling emotions. It’s not only problems with concentration and organizational skills” (Holthe, 2013, p. 43). Social difficulties persisted into adulthood for many of these women. Social anxiety and feeling unable to relate to other women were common experiences suggesting that difficulty in social relationships in adulthood may be a result of peer rejection in childhood (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Lynn, 2019).

Maladaptive Coping Strategies

Results may indicate the development of maladaptive behaviors to cope with undiagnosed ADHD (Bartlett et al., 2005; Pinkhardt et al., 2009; Stenner et al., 2019). Rucklidge (1997) found that women with ADHD engaged in less task-oriented coping and in more emotion-oriented coping. Women in these studies often turned to recreational drugs, alcohol, nicotine, and sex to self-medicate for symptoms of undiagnosed ADHD (Bartlett et al., 2005; Pinkhardt et al., 2009; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For example, one woman reported that she started drinking, smoking, and being sexually active by age 10 (Stenner et al., 2019).

Desire for Earlier Diagnosis

Many women expressed regret at the fact that they were not diagnosed and treated earlier in their lives (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Rucklidge (1997) found that 38% of women wished they had been able to change the symptoms of ADHD and those who recalled symptoms as a child viewed symptoms as their fault and largely uncontrollable. These women expressed feeling that an earlier diagnosis would have benefited them growing up (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). One participant stated, “I think that if I had known a little bit earlier, maybe that would have helped me to make sense of why things seemed harder, at an earlier age.” (Holthe, 2013, p. 47).

Results from these eight articles suggest that women who live undiagnosed until adulthood experience significant negative outcomes in the areas of self-esteem, social interaction, and psychosocial wellbeing beginning in childhood and continuing into adulthood. Earlier diagnosis and treatment may help to mediate these negative outcomes.

Theme 2: Difficult Relationships

Difficulty in family and romantic relationships was supported by seven of the eight papers in this review. Relationships with others are an important part of life; high quality close relationships and feeling socially connected to those in one’s life have been associated with decreased mortality and disease morbidity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017). Women with undiagnosed ADHD may have difficulty in relationships with the people in their lives (Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Women in these studies reported worse relationships with teachers, peers and siblings, more abusive homes, more drug and alcohol abuse by their parents, and perceived relationships more negatively than women without ADHD (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Romantic Relationships

Difficulties getting into and maintaining healthy romantic relationships can be a common experience for these women (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019). Findings may indicate women with ADHD can have problematic relationships involving abuse, divorce, and unsatisfactory sexual relationships (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Stenner et al., 2019). Women in these studies had difficulty with emotionally close relationships, intimacy, and the ability to share emotions with others without losing their own identity. They were also found to be more emotionally distant in relationships and have difficulty expressing and or verbalizing their individual needs (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019).

Family Relations

Women with ADHD in these studies often described very difficult childhoods marked by a sense of self-hatred and self-destruction arising from difficulty in familial relationships (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For example, one participant described a long history of feeling resented by family members for her “loudness” (Stenner et al., 2019). These women did not feel unconditionally accepted by their families and often felt very out of place (Bartlett et al., 2005; Stenner et al., 2019). One participant stated, “as a child I actually felt I was living in the wrong family” (Stenner et al., 2019, p. 191).

Findings suggest difficulties in relationships of all kinds were frequent among women with ADHD. Women in these studies often expressed problematic romantic relationships, difficulty expressing themselves to others, and unsupportive family environments (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Findings from these articles suggest that undiagnosed ADHD may have an impact on women’s ability to form and sustain close and meaningful relationships.

Theme 3: Lack of Control

Feeling a sense of control is integral for wellbeing and life satisfaction and has been found to be a protective factor for mental health outcomes (Keeton et al., 2008). A higher sense of control has been found to predict lower levels of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (Keeton et al., 2008). Many women with ADHD may lack this sense of control, which may leave them more vulnerable to psychological distress and lower life satisfaction (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Women with ADHD in these studies often felt little to no control academically, and in relationships with teachers, peers, parents, and siblings (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Results suggest these women viewed negative events as uncontrollable, stable, and global (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Locus of Control

Women with ADHD in these studies had a more external locus of control and felt that chance and powerful others were more controlling over their lives (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). They often attributed successes to external causes (i.e., luck, powerful others etc.) and failures to internal flaws (i.e., lack of intelligence, laziness etc.; Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For example, one woman stated, “ I remember in graduate school, when I got an A or A+, I’d immediately feel like “oh, that was because it was an easy class”, whereas if I did poorly, I’d think “this I’m supposed to be able to do, but still I can’t do it.”” (Holthe, 2013, p. 55). These women felt they had little control over their minds and that they were incapable of making decisions for themselves (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019), leaving them feeling powerless and with little confidence in their ability to cope with everyday life (Bartlett et al., 2005; Burgess, 2000; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Together, these findings suggest that women with undiagnosed ADHD may feel little control over their lives resulting in increased risk for negative psychological outcomes.

Theme 4: Self-Acceptance After Diagnosis

Feelings of relief and self-acceptance after receiving a diagnosis of ADHD as an adult were reported by six of the eight papers in this review. The experience of receiving a diagnosis can be an important moment in the lives of adult women with ADHD. Diagnosis can provide an explanation, relieve feelings of shame and guilt, and allow for increased self-acceptance. These feelings were shared by many women across several articles (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Relief

Many women in these studies experienced a sense of relief after diagnosis and felt that a professional diagnosis served as an external validation of their struggles (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). This relief is exemplified in how one woman described diagnosis as, “a huge sense of relief, this isn’t all my fault. . . the fact that you could see a reason for it and deal with it was tremendously helpful” (Rucklidge, 1997, p. 131). These women often blamed themselves for difficulties they faced growing up and a diagnosis validated their struggles, reduced feelings of self-blame, and provided them with access to various treatment interventions (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Gaining Control

Many women reported that it was only after diagnosis that they were able to feel more in control of their symptoms. Knowing that they had ADHD may have allowed them to view difficult situations from a different perspective; results suggested they now felt they had more control and viewed situations as more changeable (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Statements made by participants reflect this change such as, “I am not lazy – up to that point I was lazy. . . my control really improved, I recognized that what were weaknesses in character were now changeable” (Rucklidge, 1997, p. 130). Women also described a change in their behavior upon discovering they had ADHD, reflected in their relationships with their children, romantic partners, and with themselves (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For example, one woman stated, “ADD has made me feel better – knowledge has helped, I’m more realistic now with my expectation of myself, I can now learn new strategies” (Rucklidge, 1997, p. 130). For many women, diagnosis can provide an external explanation for difficulties previously attributed to personal flaws giving them a greater sense of control over their lives (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Self-Acceptance

Results suggested receiving a diagnosis positively impacted self-esteem and enabled women to begin to view themselves less critically (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019), with women stating, “I feel good about myself now” and “I am more understanding, kinder to myself” (Rucklidge, 1997, p. 131). Findings indicate that prior to diagnosis many women felt that they were bad people; consequently, a diagnosis made it possible for women to reconceptualize some of the feelings of guilt and shame as an external cause (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). Diagnosis can be a form of validation from an external source, enabling women to have more self-compassion (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019). For example, one woman stated “It’s answered a lot of questions . . . I let myself off the hook. . . . I’m healing that little girl inside of me” (Stenner et al., 2019, p. 191).

Results may indicate that overall diagnosis and treatment helped these women develop a sense of self-acceptance and self-awareness. They finally had an explanation for the difficulties they encountered throughout their lives. All participants explained that with diagnosis and treatment for ADHD, they were able to make more sense of their lives and more fully accept themselves. Their shame, anxiety, and depression lessened and was replaced with feelings of pride as they began to view their “disorder” as strength (Bartlett et al., 2005; Henry & Jones, 2011; Holthe, 2013; Lynn, 2019; Rucklidge, 1997; Stenner et al., 2019).

Limitations

Some limitations have been identified for the present review. Many of the studies included in this review relied on subjective measures such as self-report and interviews, which introduces the potential for bias, possibly influencing results. As well, studies relied on self-reports of childhood, which may not accurately reflect childhood experiences due to memory bias. Studies included in this review had relatively small sample sizes; consequently, generalizability may be limited.

While this review may provide summative insight into the experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD as adults, it must be noted that research on this topic is limited and it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions. For example, this review relied on the identification of individuals by individual researchers for each study and was unable to determine the impact of biological sex differences versus the impact of socially constructed gender differences. More research is needed to determine the impact of biological sex versus gender on the experience of being a woman with ADHD.

Implications

The present review has several implications for research and clinical practice in the diagnosis and treatment of women and girls with ADHD. This review may highlight a disparity in early diagnosis and treatment for boys versus girls. There is a general lack of knowledge of ADHD in females both in research and clinical practice. Healthcare professionals, teachers and parents often have limited knowledge of the specifics of ADHD in women and girls (i.e., symptoms, behaviors, and outcomes more commonly found in females), resulting in differences in diagnosis and treatment. Quinn and Wigal (2004) found that 40% of teachers report having more difficulty identifying ADHD symptoms in girls and that 85% of teachers and 57% of parents think girls are more likely to remain undiagnosed. Lynch and Davison (2022) found that teachers and clinicians struggled to identify symptoms of potential ADHD in young women. Despite these young women displaying symptoms of inattention and executive dysfunction both teachers and clinicians did not identify these as being problematic for these young women. They did not view these symptoms as needing further assessment. As such, delayed diagnosis may prevent women from accessing treatment options that could mitigate risk factors associated with ADHD (Da Silva et al., 2020).

Physicians also have difficulty in diagnosing ADHD in adult populations. Research has shown that adults with ADHD often get misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all. For example, Faraone et al. (2004) conducted a medical review of adults with ADHD and reported that only 25% of adult ADHD cases were diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. They also noted that if ADHD was not diagnosed in childhood or adolescence, primary care physicians did not consider making an ADHD diagnosis in adults. These findings may indicate a gap in knowledge of ADHD in adults and females for healthcare providers and teachers which may impede access to appropriate diagnoses and treatment options.

Women and girls continue to be under recognized and misdiagnosed when it comes to ADHD. Findings from this review may indicate that increased education and training is needed to better support women and girls with ADHD and reduce negative outcomes in adulthood. Targeted intervention aimed at educating health professionals, teachers and parents could contribute to closing the gap in diagnosis for girls providing them with increased treatment options at an earlier age.

Future Directions

Literature regarding the impacts of undiagnosed ADHD in women is scarce. As such, further research is needed to gain a more complete picture of the impact of later diagnoses for women. This research should be extended further to compare the impacts of undiagnosed ADHD in both men and women to identify potential gender differences in outcomes as well as explore underlying biases or beliefs that hinder early identification in either gender. Further research including a greater sample and mixed methodologies may have greater explanatory power and contribute to a greater understanding of adult ADHD in women.

Conclusion

Findings from the current review may indicate a need for further research into the topic of adult ADHD diagnosis in women. Living undiagnosed until adulthood can have lasting impacts on social emotional wellbeing, the ability to form and maintain relationships, and feelings of control. Based on these findings, it is apparent that undiagnosed ADHD in childhood can have lasting negative consequences into adulthood. Missed or late diagnosis can be damaging for a woman’s self-esteem, mental health, and overall wellbeing, while accurate and timely diagnosis can profoundly change the lives of women and girls with ADHD, allowing them to stop blaming themselves and begin to lead more fulfilling and satisfying lives. Women and girls are too often suffering in silence, being left out of the ADHD narrative; it is imperative that these women are not forgotten.

Author Biographies

Darby E. Attoe recently graduated with a B.A in psychology from the University of Calgary. Her research interests include, ADHD, gender, and women’s mental health.

Emma A. Climie, PhD, RPsych, is an associate professor in the School and Applied Child Psychology program in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary. She is also the lead researcher- Carlson Family Research Award in ADHD. Her research focuses on understanding children with ADHD from a strengths-based perspective, integrating primary research and intervention in the areas of resilience, stigma and mental health, and cognitive development.

Appendix A

Table 1.

Characteristics of Reviewed Studies.

| Study (country) | Population (N) | Research objectives | Data collection and data sources | Study design | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartlett et al. (2005) (Australia) | Females aged 31–49 years (N = 7) | Explore the experience of self-esteem in adult women with ADHD. | Interviews | Grounded theory | ADHD is associated with low self-esteem. |

| Burgess (2000) (United States) | Females aged 18-50 + years (N = 15) | Address specific issues related to ADHD in adult women using the framework of Erikson’s psychosocial stages. | Measures of Psychosocial Development Inventory (MPD) | Quantitative | Psychosocial development may be impacted by ADHD diagnosis. |

| Henry and Jones (2011) (United States) | Females aged 62–91 years (N = 9) | Explore the experiences of women diagnosed with ADHD in older adulthood. | Semi-Structured In-Depth interviews | Qualitative In-depth interviews | Older adult women’s ADHD symptoms impact relationships, self-esteem, and careers. |

| Holthe (2013) (Norway) | Females aged 32–50 years (N = 5) | How women with ADHD diagnosed in adulthood experience stigma. | Semi-Structured In-Depth interviews | Descriptive/phenomenology | ADHD is associated with social, emotional, and psychological difficulties. Stigma makes it hard for women with ADHD to manage symptoms. |

| Lynn (2019) (United States) Pinkhardt et al. (2009) (Germany) | Females aged 32–59 years (N = 14) Females | Functional impairments in women with ADHD. The link between ADHD, depression and smoking. | Semi-Structured interview Literature review | Phenomenology Hypothesis | Women with ADHD internalize the experience of functional impairments resulting in feelings of shame and self-loathing. Early detection and intervention of ADHD in girls could reduce rates of depression and current smoking. |

| Rucklidge (1997) (Canada) | Females aged 24–59 years (N = 117) | Attributional styles and psychosocial functioning in women with adult ADHD. | Interview Questionnaires Insolvable task Block design and vocabulary subtest of WAIS-R | Mixed Methods | Women with ADHD struggle more psychosocially and have more maladaptive attributional styles than women without ADHD. |

| Stenner et al. (2019) (England) | Females diagnosed in adulthood (N = 16) | Explore the relationship between ADHD and identity formation and life stories. | Interviews | Thematic analysis/decomposition | ADHD diagnosis can formulate a new identity and relieve self-consciousness in women. |

Appendix B

Table 2.

Themes and Codes.

| Theme | Codes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Impacts on Social Emotional Wellbeing | Lack of self-efficacy | “Common for most of the women in this study, are their descriptions of how procrastination, motivational difficulties, and problems with planning and structuring work have presented them with academic as well as psychological challenges. In the absence of a better alternative, perceived personal flaws became the explanation for academic struggles, resulting in self-blame, and over time, to a negative self-image, which has followed several of the women into adulthood” (Holthe, 2013, p. 37). |

| Shame | ||

| Feeling different | ||

| Feeling lazy or stupid | ||

| Discrepancy between who they are and who they want to be | ||

| Discrepancy between potential and achievement | ||

| Negative peer relations | ||

| Social anxiety | ||

| Difficulty relating to others | ||

| Difficulty expressing self | ||

| Isolation | ||

| Withdrawal | ||

| Comparison to others | ||

| Difficult Relationships | Abuse | “This participant had experienced considerable rejection from her family and peers as she was growing up, and had been unable to achieve the academic benchmark set by her family because of her AD/HD” (Bartlett et al., 2005, p. 56). |

| Resentment | ||

| Difficulty in romantic | ||

| relationships | ||

| Poor relationships with teachers | ||

| Not meeting expectations of family | ||

| Poor relationships with parents and siblings | ||

| Lack of Control Self-Acceptance After Diagnosis | External locus of control | “The participants in this study expressed they often felt out of control when it came to managing the internal impact of functional impairments. This lack of control caused the participants to feel discouraged, angry, sad and overwhelmed” (Lynn, 2019, pp. 60–61). |

| Feeling not in control | ||

| Self-blame | ||

| Attributing ADHD symptoms | ||

| to personal flaws | ||

| Frustration | ||

| Guilt | ||

| Negative coping skills | ||

| Feeling relieved | “All participants explained that with diagnosis and treatment for ADHD, they were able to make more sense of their lives and more fully accept themselves. Their shame, anxiety, and depression appeared to lessen, replaced with feelings of pride as they viewed their “disorder” as strength” (Henry & Jones, 2011, p. 258). | |

| Explanation | ||

| External cause for their | ||

| struggles | ||

| Self-acceptance | ||

| New or clearer identity | ||

| Relief from self-blame | ||

| Less shame |

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Darby E. Attoe  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8258-2213

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8258-2213

Emma A. Climie  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0470-1598

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0470-1598

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 [DOI]

- Bartlett L. M., Mackay F., Minichiello V. (2005). The experience of self-esteem in women with attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research University of New England. https://hdl.handle.net/1959.11/18430 [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J., Monuteaux M. C., Mick E., Spencer T., Wilens T. E., Klein K. L., Price J. E., Faraone S. V. (2006). Psychopathology in females with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A controlled, five-year prospective study. Biological Psychiatry, 60(10), 1098–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess E. R. (2000). The effect of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on psychosocial development in women [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Union Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Onunaku N., Clothier S., Poppe J. (2005). Helping young children succeed: strategies to promote early childhood social and emotional development. National Conference of State Legislatures. https://edn.ne.gov/cms/sites/default/files/u1/pdf/se18Helping%20Young%20Children%20Succeed.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva A. G., Malloy-Diniz L. F., Garcia M. S., Rocha R. (2020). Attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder and women. In Renno J., Jr., Valadres G., Cantilino A., Mendes-Ribeiro J., Rocha R., da Silva A. G. (Eds.), Women’s mental health (pp. 215–219). Springer Nature Switzerland. 10.1007/978-3-030-29081-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarvao A., Alexander D., Bucciarelli-Ducci C., Price S. (2021). Heart disease in women: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 76(S4), 118–130. 10.1111/anae.15376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S. V., Spencer T. J., Montano C. B., Biederman J. (2004). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: A survey of current practice in psychiatry and primary care. Archive of Internal Medicine, 164(11), 1221–1226. 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E., Lewis D. A., Agbeyaka S. K. (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder casts a long shadow: Findings from a population-based study of adult women with self-reported ADHD. The Child, 42(6), 918–927. 10.1111/cch.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R. M., Travers A. M., Howe Y., McDougle C. J. (2019). Women and autism spectrum disorder: Diagnosis and implications for treatment of adolescents and adults. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(4), 22. 10.1007/s11920-019-1006-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung C. M., Widiger T. A. (1998). Gender differences in the diagnosis of mental disorders: Conclusions and controversies of the DSM-IV. Psychological Bulletin, 123(3), 260–278. 10.1037/0033-2909.123.3.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry E., Jones S. H. (2011). Experiences of older adult women diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Women & Aging, 23(3), 246–262. 10.1080/08952841.2011.589285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holthe M. E. G. (2013). ADHD in women: Effects on everyday functioning and the role of stigma [Master’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley]. NTNU Open. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Robles T. F., Sbarra D. A. (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton C. P., Perry-Jenkins M., Sayer A. G. (2008). Sense of control predicts depressive and anxious symptoms across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 212–221. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klefsjö U., Kantzer A. K., Gillberg C., Billstedt E. (2021). The road to diagnosis and treatment in girls and boys with ADHD - gender differences in the diagnostic process. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 75(4), 301–305. 10.1080/08039488.2020.1850859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch A., Davison K. (2022). Gendered expectations on the recognition of ADHD in young women and educational implications. Irish Educational Studies. Advance online publication. 10.1080/03323315.2022.2032264 [DOI]

- Lynn N. M. (2019). Women & ADHD functional impairments: beyond the obvious [Master’s thesis, Grand Valley State University]. Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowlem F. D., Rosenqvist M. A., Martin J., Lichtenstein P., Asherson P., Larsson H. (2018). Sex differences in predicting ADHD clinical diagnosis and pharmacological treatment. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 481–489. 10.1007/s00787-018-1211-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum N. L. (2012). ADHD and female specific concerns: A review of the literature and clinical implications. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(2), 87–100. 10.1177/1087054711416909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan J. L., Visser T. A. W. (2009). Why is there a gender gap in children presenting for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder services? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(5), 650–660. 10.1080/15374410903103627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkhardt E. H., Kassubek J., Brummer D., Koelch M., Ludolph A. C., Fegert J. M., Ludolph A. G. (2009). Intensified testing for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in girls should reduce depression and smoking in adult females and the prevalence of ADHD in the long-term. Medical Hypotheses, 72, 409–412. 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P., Wigal S. (2004). Perceptions of girls and ADHD: Results from a national survey. Medscape General Medicine, 6(2), 2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1395774/#__ffn_sectitle [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. O. (2004). ADHD not for ‘boys only’ girls and women are affected. Behavioral Health Management, 24(4), 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. O. (2005). Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender-specific issues. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(5), 579–587. 10.1002/jclp.20121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. O. (2008). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and its comorbidities in women and girls: An evolving picture. Current Psychiatry Reports, 10(5), 419–423. 10.1007/s11920-008-0067-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P. O., Madhoo M. (2014). A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: Uncovering this hidden diagnosis. The Primary Care Companion For CNS Disorders, 16(3), eng1015475322155. 10.4088/PCC.13r01596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison R. J., Reimherr F. W., Marchant B. K., Faraone S. V., Adler L. A., West S. A. (2008). Gender differences in 2 clinical trials of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A retrospective data analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(2), 213–221. 10.4088/jcp.v69n0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge J. J. (1997). Attributional styles and psychopathology in women identified in adulthood with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Calgary].

- Rucklidge J. J., Tannock R. (2001). Psychiatric, psychosocial, and cognitive functioning of female adolescents with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(5), 530–540. 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi R. B. (2010). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and gender. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 29–31. 10.1007/s00737-009-0121-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz M. F., Filippone P., Edelman E. M. (2003). Social representations of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 1988–1997. Culture & Psychology, 9(4), 383–406. 10.1177/1354067x0394004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song P., Zha M., Yang Q., Zhang Y., Li X., Rudan I. (2021). The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health, 11, 04009. 10.7189/jogh.11.04009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P., O’Dell L., Davies A. (2019). Adult women and ADHD: On the temporal dimensions of ADHD identities. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 49, 179–197. 10.1111/jtsb.12198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waite R. (2010). Women with ADHD: It is an explanation, not the excuse du jour. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 46(3), 182–196. 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D., Johnston C. (2015). Gender differences in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A narrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 15–27. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos P. T., Roe D., Lysaker P. H. (2010). The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 13(2), 73–93. 10.1080/15487761003756860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S., Adamo N., Ásgeirsdóttir B. B., Branney P., Beckett M., Colley W., Cubbin S., Deeley Q., Farrag E., Gudjonsson G., Hill P., Hollingdale J., Kilic O., Lloyd T., Mason P., Paliokosta E., Perecherla S., Sedgwick J., Skirrow C., . . . Woodhouse E. (2020). Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 404. 10.1186/s12888-020-02707-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]