Abstract

In the year 2021, there were three new FDA approvals for all leukemia types: asciminib (Scemblix) for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) for relapsed/refractory B cell ALL, and asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi (recombinant)-rywn (Rylaze) for acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). This is down from 2017-2018, when 8 new therapies were approved for AML alone. Despite this decrease from prior years, this does not imply little progress was made in our understanding or treatment of leukemias in 2021. Asciminib and brexucabtagene autoleucel in particular are representative of major developing trends. Asciminib, a targeted therapy, is only one of many drugs in development that are products of a bedside-to-bench approach fueled by new sequencing and other genetic technologies that have greatly increased our understanding of the biology behind hematologic diseases. Brexucabtagene autoleucel, an adoptive cell therapy, is the newest of several similar treatments for B-cell associated neoplasms, and is representative of a massive push to develop novel immunotherapies for a broad range of hematologic malignancies. Herein, we review the development of asciminib and brexucabtagene autoleucel, and describe other major advances in the associated fields of targeted therapy and immunotherapy for leukemias.

Introduction

Despite long periods of stagnation in the 1970s-early 2000s, research efforts over the last 10-20 years have resulted in incredible advances in the types and efficacy of treatment options for many leukemia types. For decades, the mainstay of treatment for AML and ALL remained intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplant, both highly morbid approaches not feasible in many older and frail patients. Only recently, targeted therapies such as ivosidenib and enasidenib for IDH1 and IDH2 mutated AML, gilteritinib for FLT3-muated AML, and immune therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts), inotuzumab-ozogamcin, and the bi-specific T cell engager blinatumomab for B-cell ALL, have become alternatives or adjuncts to the traditional approaches.1-4 Additionally, the bcl2 inhibitor venetoclax, in conjunction with hypomethylating agents, has proven to be an effective and well-tolerated upfront therapy for less robust AML patients, and has modest activity in the relapsed/refractory setting.5 For CML and Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-positive ALL, targeting of BCR-ABL1 remains the mainstay of treatment, with new drugs designed to be effective even in BCR-ABL1 mutants. Asciminib is a new option with approval in 2021 and represents a major advance as discussed below. While the increase in therapy options has been a huge asset to physicians and patients alike, the variety of treatment options adds complexity to treatment algorithms. Our approaches to patient identification, disease assessments, risk stratification and prognostication must evolve at a parallel pace to the accelerated rate of therapy development. Across all leukemia types, and cancers in general, perhaps the most active area of research with great potential is in the territory of immunotherapies, both immune-modulatory drugs and adoptive cell-based approaches, as exemplified by the approval of brexucabtagene autoleucel for B-cell ALL in 2021. In this brief review, we describe the research and clinical studies behind the 2021 approvals for asciminib and brexucabtagene autoleucel. Using these two new treatments as examplars of targeted therapies and immunotherapies respectively, we then highlight other seminal publications from 2021 that illustrate the trajectory each of these arenas will be taking in years to come. It is important to note the third drug approval in 2021, asparaginase erwinia chrysanthemi (recombinant)-rywn, does represent an important option for both adult and pediatric ALL patients with hypersensitivities to E coli-derived asparaginase. However, in this review we have excluded discussion of hypersensitivity and other allergies to drugs and how to prevent them in order to focus on the above two major themes.

Asciminib

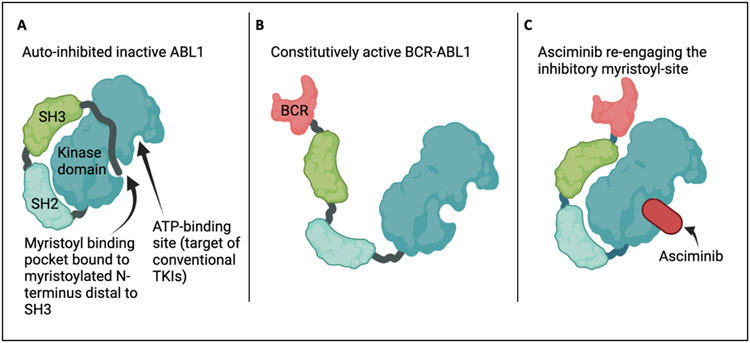

The vast majority of CML is characterized by the fusion of the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene with the non-receptor tyrosine kinase ABL1 resulting in the constitutively active “Philadelphia Chromosome.” All of the conventional first, second, and third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) of BCR-ABL1 bind the catalytic site of the kinase domain.6 As early as 2003, another region of the ABL1 kinase domain was identified that, when not fused to BCR, performed an autoinhibitory function: the myristoylated N-terminus distal to the SH3 domain binds a pocket in the kinase domain, preserving a closed, inactive fold of the protein (Figure 1).7 With BCR fusion, the myristoylated N-terminus is lost along with autoinhibition, resulting in constitutive kinase activity. Asciminib directly binds the allosteric negative-regulatory myristoyl pocket of ABL1 with high specificity and affinity,8 thereby restoring it’s inhibitory function and becoming the first clinically applicable compound of a new drug class: “Specifically Targeting the ABL Myristoyl Pocket” (STAMP). Importantly, in pre-clinical studies, asciminib was tested against all known BCR-ABL1 mutants and inhibits BCR-ABL1-mediated kinase activity and cellular proliferation even in the presence of the T351I mutation that results in resistance to all conventional TKIs other than ponatinib.

Figure 1:

Schematic representation of auto-inhibited ABL1 during normal physiologic conditions with indicated TKIbinding and auto-inhibitory myristoyl sites (Panel A), open-conformation of constitutively active BCR-ABL1 (Panel B), and asciminib binding that restores the myristoyl-mediated inhibition of kinase activity.

Hughes et al. performed the first phase I trial of asciminib in CML patients in 2019, demonstrating a favorable safety profile along with a 92% hematologic complete response (CR) rate in patients who had relapsed after previous lines of therapy, and an 88% hematologic CR rate in patients harboring a T315I mutation.9 This was followed by a phase III randomized study published in 2021 that led to asciminib’s accelerated FDA-approval.10 233 CML patients who had received at least two prior TKIs were randomized 2:1 to receive asciminib vs bosutinib. Asciminib resulted in almost double the major molecular response rate at 24 weeks (25.5% vs 13.2%), and was associated with fewer grade 3 or higher adverse events (although this number was greater than 50% in both treatment groups). Asciminib was approved both in all patients refractory to greater than or equal to 2 TKIs as well as up front in patients harboring the T315I mutation (based on the Hughes trial). This first in class STAMP represents an important resource for patients with refractory CML, and demonstrates the ability of a bedside-to-bench observation of resistance mechanisms to favorably influence drug development. Emerging evidence has shown many patients switch to asciminib from a TKI due to intolerance, and it can be effective, although less-so in patients already pre-treated with ponatinib.11 Furthermore, a pre-clinical study demonstrated synergistic effects of ponatinib when used concurrently with asciminib, suggesting their mechanisms of action could be complementary.12 The optimal incorporation of asciminb into the CML landscape, as an upfront (particularly in T315I patients) vs later-line therapy or in combination with TKIs, will continue to be an area of study, with real-life use significantly influenced by tolerability profiles.

Bench-to-bedside targeted therapy development in the modern era

As demonstrated in the case of asciminib, successful drug development and clinical application could not be possible without improvements in our understanding of disease biology. The increasing availability of various genetic sequencing modalities, such as next generation sequencing (NGS) and whole transcriptome RNA sequencing,13 has exponentially increased the amount of information we have about each leukemia type and the genetic drivers that characterize them. An estimated two thirds of all FDA approved drugs in 2021 were supported by foundational genetic studies, the majority in cancer.14 In addition to the success story of asciminib, many other publications from 2021 highlight ongoing advances in bench-to-bedside research in the realm of leukemias. For example, Cherry et al. identified AML patients harboring RUNX1 mutations had better outcomes when treated with Ven/Aza, while ELN intermediate risk patients had better outcomes with conventional chemotherapy.15 Through a retrospective next-generation sequencing analysis of 1406 patients, PTPN11 was found to co-occur most commonly with FLT3 and IDH1 mutations, and in general was associated with a worse prognosis.16 Tanaka et al demonstrated that the impact of post-remission clonal hematopoiesis was heterogeneous depending on driver mutations,17 and Schlambrock et al. characterized the divergent clonal evolution in FLT3-mutated AML patients treated with midostaurin that allowed for relapse, suggesting the underlying mechanisms of resistance could be used to stratify patients to better choose between subsequent treatment options.18 Measurable residual disease (MRD) testing has become so complex that the ELN MRD working party and a 174-member international CLL group published new consensus recommendations on MRD testing for AML and CLL respectively.19, 20 In the case of NPM1 mutations, even patients with molecular persistence at low copy number (MP-LCN), had longer relapse-free survival when treated preemptively with salvage therapy.21 These are just a few examples of the many advances made in disease characterization and the clinical impact it can have on drug design and implementation. Exactly when and in whom targeted agents will be effective will continue to be a huge area of active research.

Brexucabtagene autoleucel

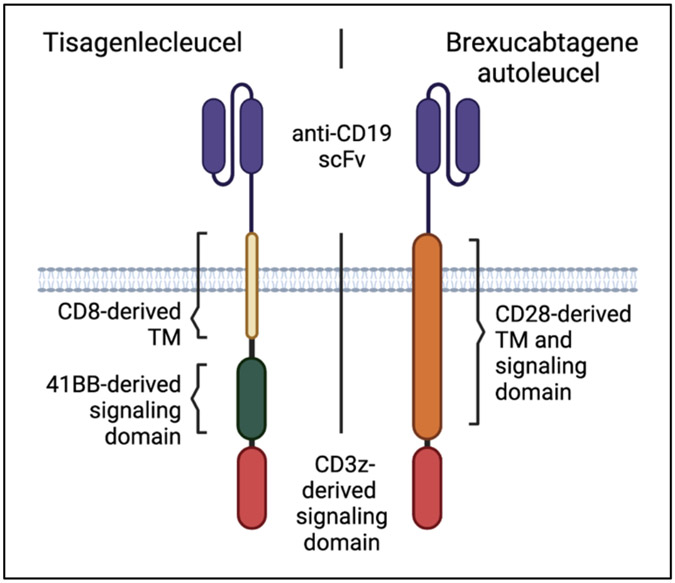

Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) was the first FDA approved CAR-T in the United States (2017), and was initially indicated for patients 25 and under with B-cell precursor ALL.22 It is comprised of an antibody-like CD19-targeting extracellular single chain fragment variable domain (scFv), coupled to a CD8-derived transmembrane domain, and 4-1BB and CD3z-derived signaling domains. As with all CAR-Ts, recognition of the antigen (here CD19, common to the B-cell lineage) on a target cell induces activation and cytotoxicity by a T cell expressing the synthetic CAR receptor. Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) also targets CD19 with a similar scFv, but instead of 4-1BB and CD8, it contains a CD28-derived transmembrane and signaling domain in conjunction with CD3z (Figure 2).23 It was first approved for relapsed/refractory (r/r) mantle cell lymphoma in 2020 based on findings of the ZUMA-2 trial.24 Subsequently, safety and efficacy of Tecartus in ALL patients was reported in the single-arm phase 2 ZUMA-3 trial, with 56% of heavily pre-treated patients achieving complete remission and median overall survival (OS) of 18.2 months.25 The ZUMA-3 trial included patients with primary refractory disease, thus Tecartus can be used in the second line setting. The type of signaling domain is thought to impact CAR-T persistence, potency, and toxicity, with several studies demonstrating a faster but more abbreviated response with CD28 CARs.26, 27 Acknowledging the caveat of cross-trial comparison, response rates and OS were comparable for Kymriah and Tecartus. Tecartus was associated with higher incidence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS, 89% vs 77%) and neurologic events (60 vs 40%) of any grade, but lower incidence of grade 3 or higher CRS (24% vs 46%). A direct comparison of Kymriah and Tecartus to assess differences in toxicity and efficacy has not been performed, but both represent important options for r/r ALL patients, young and old. An important decision point will be when to utilize these CAR-Ts versus blinatumomab and inotuzumab, since all 4 are now approved for similar indications. Studies have shown higher overall CR rates with CAR-T compared to blinatumomab, particularly in patients with higher disease burden and extramedullary disease.28 Limitations for CAR-Ts include time and cost for manufacturing, health of T cells after previous cytotoxic therapies, and their susceptibility to immunosuppressive mechanisms.29 Blinatumomab and/or inotuzumab after CAR-T resulted in 58% CR rates, although duration of remission was short, with median OS of only 7.5 months.30 Patient selection and appropriate sequencing of novel immunotherapies is an ongoing area of research and optimization.

Figure 2:

Schematic representation of the two CARs currently approved for B-cell ALL: Kymriah (2017) and Tecartus (2021). TM = transmembrane domain; scFv = single chain fragment variable domain.

Immunotherapies in development for leukemias

In addition to Tecartus, numerous additional new immunotherapies for various leukemia types are under development, with preliminary results for a variety of exciting strategies published in 2021. Leukemia-specific targets in AML include CD33,31 Siglec-6,32, 33 and CD70.34 In the case of CD13, direct targeting with scFv results in toxicity against normal hematopoietic stem cells, but by using a titratable anti-CD13 antibody with a CAR that then binds this antibody, He et al. were able to mitigate the on-target/off-tumor toxicity while still maintaining anti-leukemic efficacy.35 Similarly, Benmebarek et al. designed a synthetic CAR-like receptor that binds a complimentary synthetic antibody with short half-life and modular specificity, and demonstrated anti-leukemic activity using antibodies for CD33 and CD123.36 Anti-CD7 CAR-T cells have already been tested in a phase I clinical trial for r/r T-cell ALL involving 20 patients, 18 (90%) of whom achieved CR with acceptable rates of toxicity.37 Gene-editing was used to remove CD7 from these CAR-T cells to prevent fratricide, without impairing antigen recognition or cytotoxicity. In the realm of stem cell transplant, Pierini et al. reported reduced GVHD and improved RFS in AML patients using a novel immunotherapy approach in which donor-derived T regulatory cells were infused at day −4 pre-transplant, and conventional T cells were infused at day −1, with no GVHD prophylaxis administered post-transplant.38

Non-cell based immunotherapies are also an area of investigation, such as the use of a ROR1-specific antibody-drug conjugate for ROR1+ leukemias.39 Furthermore, a CD123-directed antibody drug conjugate has shown promise in pre-clinical studies of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) with first clinical experience presented at ASH in 2021 (abstract 616), and is currently in phase Ib/II clinical trial for AML patients (NCT04086264). Finally, blocking the “don’t eat me” signal of SIRPa/CD47 interactions with the antibody magrolimab is one of the first immunotherapies to harness the innate immune system, and was shown to allow specific destruction of leukemic stem cells.40 Several phase II and III trials using magrolimab in leukemias and MDS are ongoing (NCT04778397, NCT04313881, NCT04778410) These examples provide a gestalt of the potential future for immunotherapies in leukemia.

Conclusion

In summary, the year 2021 was productive for leukemia research and treatment, with three new therapies FDA approved. Asciminib is representative of targeted therapies and the technological improvements that have not only improved our ability to design effective therapies, but also helped predict responsive vs refractory patients, improved risk stratification and prognostication, and added nuance to residual disease testing and associated treatment decision making. Brexucabtagene autoleucel is representative of the burgeoning immunotherapy developments occurring in ALL and other leukemias, particularly AML. Both, along with the numerous other publications on their related topics, are harbingers of future advances soon to come.

Bibliography

- 1.Yu J, Jiang PYZ, Sun H, et al. Advances in targeted therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Biomark Res. 2020;8:17. doi: 10.1186/s40364-020-00196-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shang Y, Zhou F. Current Advances in Immunotherapy for Acute Leukemia: An Overview of Antibody, Chimeric Antigen Receptor, Immune Checkpoint, and Natural Killer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:917. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin versus Standard Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. Aug 25 2016;375(8):740–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or Chemotherapy for Relapsed or Refractory FLT3-Mutated AML. N Engl J Med. Oct 31 2019;381(18):1728–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samra B, Konopleva M, Isidori A, Daver N, DiNardo C. Venetoclax-Based Combinations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Front Oncol. 2020;10:562558. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.562558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AB, O'Hare T, Deininger MW. Mechanisms of Resistance to ABL Kinase Inhibition in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia and the Development of Next Generation ABL Kinase Inhibitors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. Aug 2017;31(4):589–612. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoepfer J, Jahnke W, Berellini G, et al. Discovery of Asciminib (ABL001), an Allosteric Inhibitor of the Tyrosine Kinase Activity of BCR-ABL1. J Med Chem. Sep 27 2018;61(18):8120–8135. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wylie AA, Schoepfer J, Jahnke W, et al. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR-ABL1. Nature. Mar 30 2017;543(7647):733–737. doi: 10.1038/nature21702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes TP, Mauro MJ, Cortes JE, et al. Asciminib in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia after ABL Kinase Inhibitor Failure. N Engl J Med. Dec 12 2019;381(24):2315–2326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1902328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rea D, Mauro MJ, Boquimpani C, et al. A phase 3, open-label, randomized study of asciminib, a STAMP inhibitor, vs bosutinib in CML after 2 or more prior TKIs. Blood. Nov 25 2021;138(21):2031–2041. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luna A, Perez-Lamas L, Boque C, et al. Real-life analysis on safety and efficacy of asciminib for ponatinib pretreated patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. Oct 2022;101(10):2263–2270. doi: 10.1007/s00277-022-04932-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleixner KV, Filik Y, Berger D, et al. Asciminib and ponatinib exert synergistic anti-neoplastic effects on CML cells expressing BCR-ABL1 (T315I)-compound mutations. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11(9):4470–4484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arindrarto W, Borras DM, de Groen RAL, et al. Comprehensive diagnostics of acute myeloid leukemia by whole transcriptome RNA sequencing. Leukemia. Jan 2021;35(1):47–61. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0762-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ochoa D, Karim M, Ghoussaini M, Hulcoop DG, McDonagh EM, Dunham I. Human genetics evidence supports two-thirds of the 2021 FDA-approved drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. Jul 8 2022;doi: 10.1038/d41573-022-00120-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherry EM, Abbott D, Amaya M, et al. Venetoclax and azacitidine compared with induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. Dec 28 2021;5(24):5565–5573. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alfayez M, Issa GC, Patel KP, et al. The Clinical impact of PTPN11 mutations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. Mar 2021;35(3):691–700. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0920-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka T, Morita K, Loghavi S, et al. Clonal dynamics and clinical implications of postremission clonal hematopoiesis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. Nov 4 2021;138(18):1733–1739. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020010483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmalbrock LK, Dolnik A, Cocciardi S, et al. Clonal evolution of acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD mutation under treatment with midostaurin. Blood. Jun 3 2021;137(22):3093–3104. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heuser M, Freeman SD, Ossenkoppele GJ, et al. 2021 Update on MRD in acute myeloid leukemia: a consensus document from the European LeukemiaNet MRD Working Party. Blood. Dec 30 2021;138(26):2753–2767. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wierda WG, Rawstron A, Cymbalista F, et al. Measurable residual disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: expert review and consensus recommendations. Leukemia. Nov 2021;35(11):3059–3072. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiong IS, Dillon R, Ivey A, et al. Clinical impact of NPM1-mutant molecular persistence after chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. Dec 14 2021;5(23):5107–5111. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. Feb 1 2018;378(5):439–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson MK, Torosyan A, Halford Z. Brexucabtagene Autoleucel: A Novel Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for the Treatment of Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Ann Pharmacother. May 2022;56(5):609–619. doi: 10.1177/10600280211026338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. Apr 2 2020;382(14):1331–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah BD, Ghobadi A, Oluwole OO, et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet. Aug 7 2021;398(10299):491–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01222-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X, Yang J, Zhang X, et al. Efficacy and Safety of CD28- or 4-1BB-Based CD19 CAR-T Cells in B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Mol Ther Oncolytics. Sep 25 2020;18:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salter AI, Ivey RG, Kennedy JJ, et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis of chimeric antigen receptor signaling reveals kinetic and quantitative differences that affect cell function. Sci Signal. Aug 21 2018;11(544)doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aat6753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina JC, Shah NN. CAR T cells better than BiTEs. Blood Adv. Jan 26 2021;5(2):602–606. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subklewe M. BiTEs better than CAR T cells. Blood Adv. Jan 26 2021;5(2):607–612. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wudhikarn K, Flynn JR, Riviere I, et al. Interventions and outcomes of adult patients with B-ALL progressing after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood. Aug 19 2021;138(7):531–543. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tambaro FP, Singh H, Jones E, et al. Autologous CD33-CAR-T cells for treatment of relapsed/refractory acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. Nov 2021;35(11):3282–3286. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovalovsky D, Yoon JH, Cyr MG, et al. Siglec-6 is a target for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. Sep 2021;35(9):2581–2591. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01188-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jetani H, Navarro-Bailon A, Maucher M, et al. Siglec-6 is a novel target for CAR T-cell therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. Nov 11 2021;138(19):1830–1842. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauer T, Parikh K, Sharma S, et al. CD70-specific CAR T cells have potent activity against acute myeloid leukemia without HSC toxicity. Blood. Jul 29 2021;138(4):318–330. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He X, Feng Z, Ma J, et al. CAR T cells targeting CD13 controllably induce eradication of acute myeloid leukemia with a single domain antibody switch. Leukemia. Nov 2021;35(11):3309–3313. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01208-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benmebarek MR, Cadilha BL, Herrmann M, et al. A modular and controllable T cell therapy platform for acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. Aug 2021;35(8):2243–2257. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-01109-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan J, Tan Y, Wang G, et al. Donor-Derived CD7 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: First-in-Human, Phase I Trial. J Clin Oncol. Oct 20 2021;39(30):3340–3351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierini A, Ruggeri L, Carotti A, et al. Haploidentical age-adapted myeloablative transplant and regulatory and effector T cells for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. Mar 9 2021;5(5):1199–1208. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu EY, Do P, Goswami S, et al. The ROR1 antibody-drug conjugate huXBR1-402-G5-PNU effectively targets ROR1+ leukemia. Blood Adv. Aug 24 2021;5(16):3152–3162. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galkin O, McLeod J, Kennedy JA, et al. SIRPalphaFc treatment targets human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Haematologica. Jan 1 2021;106(1):279–283. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.245167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]