Abstract

Introduction

There is a paucity of literature on the comprehensive roles of security guards in healthcare, regardless of day-to-day observations of security guards playing an extensive role in this field. Thus, this review will systematically explore the roles of security guards in healthcare contexts to create a centred body of evidence.

Methods and analysis

The study will systematically review existing quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed literature on security guards in institutional healthcare so as to understand their roles. We will conduct the systematic review on 10 electronic databases: BioMed Central, SocIndex, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, JSTOR, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed. Data extraction will be in the form of a word document. Mendeley software will be used to keep track of references, while the systematic review software, Rayyan, will be used for the screening, inclusion and exclusion of articles. If necessary, reviewer number 3 will conduct a third review should any disputes arise between the two initial reviewers. Quality assessment of the articles will be measured with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for articles in terms of the research aims, methodology used, sample, data analysis, presentation of findings, values of the research, as well as trustworthiness if it is a qualitative study or reflexiveness if it is a quantitative study. Studies dating back 32 years will be incorporated for a comprehensive review.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review will use publicly available peer-reviewed data from electronic databases and will, therefore, not require an ethical review, but rather, an ethics waiver. The systematic review protocol will be submitted for ethics waiver clearance from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee. The findings from this review will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conferences.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42022353653.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, Quality in health care, GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), PSYCHIATRY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

With the aim of providing a comprehensive overview, both quantitative and qualitative studies will be included.

In addition to the multidisciplinary databases, the reference sections of the included studies will be searched to find relevant articles that were missed by the search engines or not listed in the selected databases.

The implementation and reporting of the systematic review will follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses to ensure transparency and accuracy.

Studies which are published in languages other than English will not be included, which can lead to a linguistically caused bias.

This study employs a systematic review method of reviewing data. This approach that is rigorous, transparent and ensures results are trustworthy; however, additional results might be identified by following another design.

Introduction

Background

Many healthcare facilities employ security guards as part of their security strategy.1 Adeniyi and Puzi2 attribute this to violent and aggressive behaviours that are not uncommon in many healthcare institutions, including hospitals and psychiatric and emergency units.3–6 Such behaviours are among the key reasons for the employment of security guards.7 Other reasons include the protection of valuable property held in healthcare facilities, public visitation control and perimeter patrols to protect the privacy and dignity of patients, and the provision of information in large facilities regarding where to find particular wards or units and the rules of visitation and entry. Security guards filter access control and protect the institution through the checking of visitor appointment cards and entry to the correct facility within institutions.8

An important function of security guards is safety intervention when patients threaten to harm themselves, staff or other patients, or when there is a need for physical restraint or de-escalation.1 9 Thus, a key role is to ensure patient and staff safety by managing violent and aggressive behaviour.10–12

Security guards are more likely than healthcare professionals to be injured at work, with many attacks occurring at night. Clearly, they are on the front line, commonly being deployed to reinforce the overall security programme of health facilities and being called in to situations of elevated risk.13 In a study on security guards in Finland, 39% reported at least one incident of verbal aggression against them per month, 19% reported at least one threat of physical aggression per month and 15% experienced at least one act of physical aggression per month.14

In addition to the official tasks that security guards are contracted for, they may also take on other roles, even if informally.15 It is clear, therefore, that security guards take on numerous roles and perform several tasks, including, in some instances, tasks for which they are not adequately trained.16 For instance, security guards may be asked to perform the role of informal interpreters when clinicians are not able to communicate with patients who speak languages which clinicians do not understand.17 18 A study, conducted in South Africa at a psychiatric hospital, investigated the potential consequences for diagnostic assessments mediated by ad hoc interpreters who were employed as healthcare workers and household aides. The study found errors in the interpretations, which consequently affected the goals and outcomes of the clinical sessions, some potentially resulting in incorrect diagnoses of the severity of patient psychiatric illness. Within the context of the current research protocol, security guards may be assigned to carry out informal interpreting in the absence of training and support in interpreting skills, and, in addition, these security guards may be unfamiliar with technical medical and psychiatric terminology.17

Sefalafala and Webster19 note that security guards are often among the lower paid staff members at a healthcare facility. Given these pressures, some studies suggest that security guards may be prone to behavioural problems and mental health problems such as substance abuse, antisocial behaviour, physical aggression and anger.20 Notwithstanding, it appears that little attention has been given to the work of security guards in healthcare despite the fact that security guards are part of the broader healthcare workforce.20

This review seeks to systematically examine and synthesise research on the role of security guards in healthcare. To our knowledge, this will be the first review on this topic. We aim to understand critical processes and outcomes related to the use of security guards in healthcare. It is possible that the review may lead to recommendations for adequate training and support for this cadre of workers, as well as guidelines and policy recommendations.

Methods and analysis

Types of studies

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies on the roles of security guards will be incorporated in this review. Scientific studies published in English will be included. Any studies reporting on the roles of security guards and their experience of these roles will be included. There is no geographical restriction—we will search for studies from high-income, middle-income and low-income countries. All studies included must have been peer-reviewed.

Type of participants

Studies must report on the roles and experiences of security guards but there are no other restrictions, for example, studies on healthcare workers’ perceptions of the roles and experiences of security guards will be included.

Search methods for identification of studies

We will conduct the systematic review on 10 electronic databases: BioMed Central, SocIndex, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, JSTOR, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed. Data extraction will be in the form of a Word document. Mendeley referencing software will be used to manage searched articles, thereafter transferred to the systematic review software, Rayyan, where duplicates will be removed. We have developed a search strategy that will be adapted to different search engines (see table 1). In addition to database search results, reference sections of the included journal articles will be reviewed to identify any relevant articles that were missed by search engines.

Table 1.

Search strings for electronic databases

| Concept A: security guards | Concept B: health care |

| Within Concept A, terms used will include: | Within Concept B, terms used will include: |

| “security guards” OR “security officers” OR “patrol officers” OR “attendant” OR “manhandle” OR “patient watch” OR “supervision” OR “management” OR “hospital safety” OR “policing” OR “security personnel” OR “hospital security” OR “hospital safeguarding” OR “guard” OR “keeper” OR “watchperson” OR “security officers” OR “hospital monitor” Or “security force”. | “hospital” OR “mental health” OR “psychiatric care” OR “inpatient psychiatric units” OR “emergency units” OR “psychiatry” OR “mental health” OR “mental institution” OR “psychiatric hospital” OR “psychiatric ward” OR “mental facility” OR “clinical settings” OR “health” OR “primary care” OR “behavioural unit” OR “clinical settings” OR “health care” OR “health” OR “health service” OR “medical aid” OR “medical assistance” OR “public health care” OR “health care service” OR “health-care” OR “health-related” OR “medical field” OR “clinics” OR “hospitals”. |

Search strategy

The keywords listed in table 1 will guide the searches. These strings will be expanded based on the information retrieved from selected articles.

Time period

Articles reviewed will include those published from 1990 to 2022 to provide a comprehensive examination and synthesisation of the existing research.

Exclusion criteria

This review will exclude grey literature, unpublished articles, opinion pieces, case reports and publications that do not have primary data and a clear description of the methods used. In cases where studies analysing the same data are published in more than one journal, we will include the most recent and complete publication. Any articles, research and data prior to 1990 will be excluded, as will studies in languages other than English. Studies that focus on medical personnel and not on security guards will also be excluded (see table 2).

Table 2.

Overall approach to inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Included | Excluded | |

| Publication type | English peer-reviewed journal articles. | |

| Study design | All study designs. | |

| Study population | All studies conducted on security guards of all ages in high-income, middle-income and low-income countries. | Grey literature, unpublished articles, cases and publications that do not have a clear description of methods used. Any data before 1990. |

| Exposure variables | N/A | |

| Outcome variables | All roles, uses and responsibilities reported by studies. |

N/A, not available.

Inclusion criteria

Studies published in English peer-reviewed journals and open sources accessed from the Stellenbosch University library website will be included. In addition, this study will focus on all age groups and studies reported in English from 1990 to 2022. This will allow for a comprehensive scope in this niche area (see table 2).

Selection of studies to be included in the review

To define the inclusion criteria, most studies use the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome model. This model is used for quantitative clinical research.21 This study, therefore, adopts the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type, which is a suitable framework for the inclusion of qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies22 (see table 3). Screening, inclusion and exclusion of articles will be carried out using Rayyan. The screening process involves title and abstract screening by two independent reviewers, followed by full-text screening by two independent reviewers. Where there are disagreements across the two reviewers, a third reviewer will carry out an independent review to resolve differences.

Table 3.

SPIDER approach for selecting studies

| SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type) | |

| Sample | Security guards working in healthcare and other healthcare providers, any age and gender. The review is not restricted to geographical area, examining data from all over the world, thus including the perspectives of healthcare professionals internationally. |

| Phenomenon of Interest | The role of security guards in healthcare. |

| Design | Peer-reviewed published literature of any research design. |

| Evaluation | Characteristics, views, experiences. |

| Research Type | Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods peer-reviewed studies. |

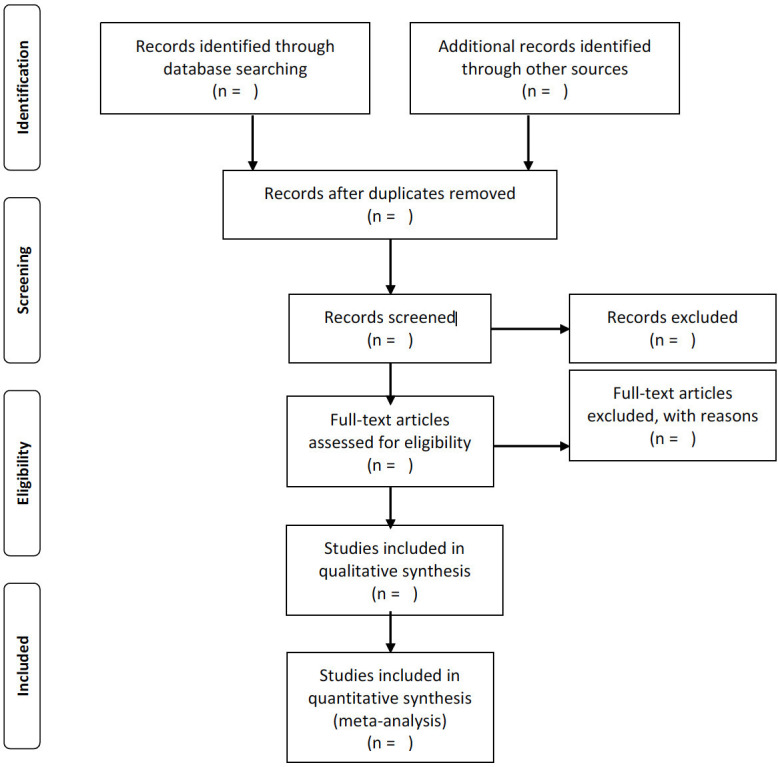

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart will be an additional retrieval strategy to document the search.23 The first step will be screening the literature. A title search will be conducted using the database and the study’s keywords, these being documented on the title extract and abstract search list. Only articles that fulfil the title inclusion criteria will advance to the second level, which is the abstract search. The PRISMA flow chart will account for the number of records identified or removed (see figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram of study selection process.

Quality appraisal and assessment of bias

On selecting articles which fulfil the title and abstract search criteria, articles included will be appraised. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool24 is commonly used,25 and an adapted version of the CASP tool, proposed by Laher and Hassem,26 will be used in this study. This tool consists of six items for theoretical articles, 11 items for quantitative articles and 10 questions for qualitative articles, which will be used as an appraisal tool in terms of the research aims, methodology used, sample, data analysis, presentation of findings, values of the research, as well as trustworthiness if it is a qualitative study and reflexivity if it is a quantitative study.26

The CASP tool itself proposes a cut-off for a study after a few questions/checklists, therefore, any scoring or grading is not recommended for studies being appraised.24 The first few questions on the CASP checklist are screening questions; if the answer to them is ‘yes’, then the study is worth proceeding to the remaining questions. An article must fulfil the full checklist in order to advance to the extraction phase.

Data extraction and management

To extract data, reviewer number 1 will conduct data extraction in Word. Extracted data will be tabularised to include study details (author, year of publication, country of study). In addition to author, year of publication, country of study, information on the roles and responsibilities of security guards in healthcare settings, including the scope of their work, how their roles as perceived by fellow healthcare workers and their impact on their workplace and patients will be extracted.

Data synthesis and analysis

A narrative analysis/synthesis will be conducted to extract text which will then be narrated.21 Popay et al27 outline four elements involved in reporting narratively, namely, (1) developing a theory of how the intervention works, why and for whom; (2) developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies; (3) exploring similarities/relationships in the data and (4) assessing the robustness of the synthesis. For the purpose of this study, only elements 2–4 will be included as the aim is not to develop an intervention, but rather to synthesise the roles of security guards in healthcare. The data will be presented in the form of a qualitative narrative description, in table format. For transparent reporting, the analysis will be guided by the PRISMA statement.

The planned start of the review will be as soon as the protocol has been accepted (probably in March 2023) and is expected to be completed in April 2024.

Patient and public involvement

As this is a systematic review protocol, no patients or public will be involved.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review will use publicly available peer-reviewed data from the 10 identified search engines (BioMed Central, SocIndex, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, JSTOR, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed) and will therefore not require an ethical review, but rather, an ethics waiver. The systematic review protocol will be submitted for ethics waiver clearance from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee. The findings from this review will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and conferences.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LSh, LSw and SH-R conceptualised the study. LSh was responsible for drafting the protocol in close consultation with LSw and SH-R. QC, PS and TR provided significant edits to the protocol. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Muir-Cochrane E, Muller A, Fu Y, et al. Role of security guards in code black events in medical and surgical settings: a retrospective chart audit. Nurs Health Sci 2020;22:758–68. 10.1111/nhs.12725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeniyi OV, Puzi N. Management approach of patients with violent and aggressive behaviour in a district hospital setting in South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract (2004) 2021;63:e1–7. 10.4102/safp.v63i1.5393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.d’Ettorre G, Pellicani V. Workplace violence toward mental healthcare workers employed in psychiatric wards. Saf Health Work 2017;8:337–42. 10.1016/j.shaw.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shannon S, Devitt P, Murphy KC. Increased use of security personnel in Irish psychiatric hospitals: 2008-2012. Ir J Psychol Med 2015;32:319–25. 10.1017/ipm.2015.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, et al. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. PS 1990;41:761–70. 10.1176/ps.41.7.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman A. Mitigating workplace violence via de-escalation training [Ebook]. The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety, 2020. Available: https://iahssf.org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-De-Escalation-Training.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence RE, Perez-Coste MM, Arkow SD, et al. Use of security officers on inpatient psychiatry units. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:777–83. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szuba T. Safeguarding your technology: practical guidelines for electronic education information security. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics (ED), National Postsecondary Education Cooperative, National Forum on Education Statistics, 1998. Available: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED421996.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muir-Cochrane E, Oster C. Chemical restraint: a qualitative synthesis review of adult service user and staff experiences in mental health settings. Nurs Health Sci 2021;23:325–36. 10.1111/nhs.12822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iozzino L, Ferrari C, Large M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of violence by psychiatric acute inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128536. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelto-Piri V, Warg L-E, Kjellin L. Violence and aggression in psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden: a critical incident technique analysis of staff descriptions. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:362. 10.1186/s12913-020-05239-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaducci G, Stubbs B, McNeill A, et al. Violence in mental health settings: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018;27:33–45. 10.1111/inm.12425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gramling JJ. Protecting the protectors: violence-related injuries to hospital security personnel and the use of conducted electrical weapons [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Minnesota, 2017. Available: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/188828 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leino T, Selin R, Summala H, et al. Work-related violence against security guards -- who is most at risk? Ind Health 2011;49:143–50. 10.2486/indhealth.ms1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagan S, Hunt X, kilian S, et al. AD hoc interpreters in South African psychiatric services: service provider perspectives. global health action. 2020;13. 10.1080/16549716.2019.1684072 Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/16549716.2019.1684072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Miller M, et al. Emergency department workers’ perceptions of security officers’ effectiveness during violent events. Work 2012;42:21–7. 10.3233/WOR-2012-1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilian S, Swartz L, Dowling T, et al. The potential consequences of informal interpreting practices for assessment of patients in a South African psychiatric Hospital. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;106:67–159. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith J, Swartz L, Kilian S, et al. Mediating words, mediating worlds: interpreting as hidden care work in a South African psychiatric institution. Transcultural psychiatry. 2013;50:493–514. 10.1177/1363461513494993 Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1363461513494993?casa_token=zudklHMSEMYAAAAA:3FrB7nDLbyMKIbbU4IuS8tH89pbqofM36I57UU8dZtDqYnMEveK2r5TXFA644xRKvALrfvWHGCcsNQ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sefalafala T, Webster E. Working as a security guard: the limits of professionalisation in a low status occupation. S Afr Rev Sociol 2013;44:76–97. 10.1080/21528586.2013.802539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad A, Hazrina Mazlan N. The kind of mental health problems and it association with aggressiveness: a study on security guards. IJPBS 2012;2:237–44. 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120206.07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, et al. Taking account of context in systematic reviews and guidelines considering a complexity perspective. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000840. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the spider tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1435–43. 10.1177/1049732312452938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health Resource Unit . Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. 2018. Available: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf [Accessed 16 Oct 2022].

- 25.Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences 2020;1:31–42. 10.1177/2632084320947559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laher S, Hassem T. Doing systematic reviews in psychology. S Afr J Psychol 2020;50:450–68. 10.1177/0081246320956417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, 1, b92. Lancaster University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.