Abstract

Objectives

To assess the awareness and predictors of seeing/hearing a drug alert in British Columbia (BC) and subsequent drug use behaviour after seeing/hearing an alert.

Methods

This study analysed the 2021 BC harm reduction client survey (HRCS)—a cross-sectional self-reported survey administered at harm reduction sites throughout the province and completed by participants using the services.

Results

In total, n=537 respondents participated and n=482 (89.8%) responded to the question asking if they saw/heard a drug alert. Of those, n=300 (62.2%) stated that they saw/heard a drug alert and almost half reported hearing from a friend or peer network; the majority (67.4%) reported altering their drug use behaviour to be safer after seeing/hearing a drug alert. The proportion of individuals who saw/heard a drug alert increased with each ascending age category. Among health authorities, there were significant differences in the odds of seeing/hearing an alert. In the past 6 months, the odds of participants who attended harm reduction sites a few times per month seeing/hearing an alert were 2.73 (95% CI: 1.17 to 6.52) times the odds of those who did not. Those who attended more frequently were less likely to report seeing/hearing a drug alert. The odds of those who witnessed an opioid-related overdose in the past 6 months seeing/hearing an alert were 1.96 (95% CI: 0.86 to 4.50) times the odds of those who had not.

Conclusion

We found that drug alerts were mostly disseminated through communication with friends or peers and that most participants altered their drug use behaviour after seeing/hearing a drug alert. Therefore, drug alerts can play a role in reducing harms from substance use and more work is needed to reach diverse populations, such as younger people, those in differing geographical locations, and those who attend harm reduction sites more frequently.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, health policy

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Provides insight into the lived and living experiences of people who use drugs (PWUD).

Identifies strengths and weaknesses in the communication of drug alerts.

Enhances our understanding of the efficacy of drug alerts and the effect on drug use behaviour.

Uses cross-sectional data, thus, preventing establishment of temporal relationships.

Not representative of all PWUD, only those who attend harm reduction sites.

Introduction

More than 100 000 drug overdose deaths were identified in the USA in 2021.1 In Canada, 32 632 opioid toxicity deaths were reported between January 2016 and March 2022.2 During the same time period, 33 493 opioid-related and 14 606 stimulant-related poisoning hospitalisations were reported.3 In addition to the strain put on hospitals, emergency first responders are also challenged to respond to the effects of toxic drug supply. In 2021, there were more than 41 600 Emergency Medical Service responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses in Canada.4

These challenges are not limited to healthcare professionals. The COVID-19 pandemic and public health measures such as physical distancing introduced to prevent virus transmission further exacerbated this complex issue. As harm reduction services became less available and overdoses increased, peers (people with lived experience of substance use who use that experience in their work) took on a greater burden of supporting people who use drugs.5

British Columbia (BC) declared a public health emergency in April 2016 in response to increasing overdoses fuelled by fentanyl.6 BC has the highest rate of opioid-related overdoses of all provinces, in 2021 BC reported 2267 illicit drug toxicity deaths, the highest annual number of deaths ever reported.7 In August 2022, the BC Coroners Service reported reaching the tragic milestone of 10 000 lives lost to the toxic drug supply since the public health emergency was declared.8 Postmortem toxicology in BC has detected fentanyl or its analogues in more than 80% of deaths since 2017.9 The proportion of cases where benzodiazepines were detected in decedents increased from 15% in July 2020 to 52% in January 2022.9 In addition, identification of extreme fentanyl concentrations (>50 mg/L) doubled from 8% of decedents between January 2019 and March 2020 to 16% between November 2021 and August 2022.9 Drug toxicity deaths are preventable, and advocates are calling for improved policies, treatment and harm reduction measures to support and provide resources to people who use drugs (PWUD).5

Initiatives to address the illicit drug toxicity crisis in BC include the implementation and expansion of harm reduction services such as opioid agonist treatment, take-home naloxone kits, supervised consumption and overdose prevention sites and drug checking. Another strategy is the use of drug alerts to warn PWUD, members of the public and service providers about the current risks of the circulating drug supply. In 2020, there were 160 drug alerts issued in BC, a few alerts were province wide but most were disseminated to a specific region or town, with more than half implicating fentanyl as a concern.10 Alerts may be disseminated when harms are identified following the use of an unknown substance, or when analyses of substances identify a particular drug, combination of drugs or drug concentration of concern. Timely identification is often through drug checking services which are increasingly available across BC, such as those provided through and in partnership with the BC Centre on Substance Use and the Vancouver Island Drug Checking Project.11 12 Analysis of enforcement samples and decedent toxicology supplement this information but is usually delayed and thus not appropriate for timely drug alerts.

Drug alerts are distributed through different forms of media, including provincial, regional and harm reduction service websites; social media and social networks; as well as being distributed through outreach activities including posters and word of mouth.13 The content of drug alerts varies from general warnings about drug use to specific details related to a single drug—details may include different names it is being sold under, colour, form and area where it is believed to be circulating. Alerts developed and distributed by BC health authorities are collated by the BC Centre for Disease Control and published on the public website towardtheheart.com.14

Drug alerts provide an opportunity to provide life-saving information quickly and efficiently. BC health authorities and community organisations utilise different methods to distribute drug alerts in order to reach PWUD who use a variety of information sources. There are also important considerations for disseminating drug alerts as well. For example, language matters when issuing information related to the circulating drug supply. Information that may warn individuals about a drug’s potency may lead individuals to seek out this drug because of its stronger effect.15 Furthermore, drug alerts need to focus on maintaining human dignity and respecting a person’s autonomy while being informative and clear.

Notably, drug alerts are intended to reach individuals responsible for manufacturing the substance(s) as well as those using them. In 2012, the BC Drug Overdose and Alert Partnership (DOAP) issued alerts provincially and locally when paramethoxymethamphetamine, a toxic substance, was identified in people who died after using what they believed was ecstasy.16 17 Drug alerts are also being used globally, such as in the Netherlands, where there was an observed association between drug alerts and reduced drug-associated adverse health outcomes, compared with jurisdictions not using drug alerts.18–20

Our study analysed data from the 2021 BC harm reduction client survey (HRCS), which sampled people using harm reduction supply distribution sites around the province. Our aim was to determine the characteristics of who reported seeing/hearing drug alerts, where they saw/heard the alerts and if they reported safer use when they saw/heard an alert in order to improve the alerting process.

Materials and methods

Data source

The 2021 BC HRCS gathered information on substance use patterns, associated harms, stigma and utilisation of harm reduction services to inform harm reduction planning and to evaluate current practices.21 The cross-sectional HRCS was piloted in 2012 and has been administered annually since (except 2016, 2017 and 2020). Each iteration of the survey contains questions relevant to emerging issues and the priorities of stakeholders. Stakeholders, including PWUD, provided input and piloted questions on awareness of drug alerts included in the 2021 HRCS. Locations for data collection were selected from a provincial network of sites that distribute supplies for safer substance use, using two-stage convenience sampling. Harm reduction program coordinators from each regional health authority identified potential sites for participation; sites were then recruited based on willingness to participate and their capacity for recruitment and data collection. In total, 17 harm reduction sites participated in the 2021 HRCS between March 2021 and January 2022. Trained site staff and volunteers recruited participants who received $15 CAD and the sites received $5 CAD per participant recruited. The anonymous paper-based survey took approximately 20 min to complete and participants were informed that they may only complete the survey once.

The eligibility criteria for participants included being 19 years of age or older, having used or currently using any illegal substance(s) other than or in addition to cannabis in the past 6 months, and being able to provide verbal informed consent. Data entry and analysis occurred at the British Columbia Center for Disease Control (BCCDC) in Vancouver, BC. Data collection methods have been described elsewhere.10

Study variables

We assessed who reported recently seeing/hearing a drug alert and associations with demographic and drug use data from responses to the question ‘have you recently seen or heard an alert about recent drug overdoses, toxic drugs found for example, from drug checking/testing and other possible issues with street drugs?’ We thematically analysed responses to the question ‘where did you notice these alerts?’ We assessed if seeing/hearing a drug alert led participants to report using drugs more safely by the response to ‘Do you take any steps to be safer (get drugs checked/tested, use overdose prevention sites, use with a buddy etc.) when you see an alert about drugs you may use?’

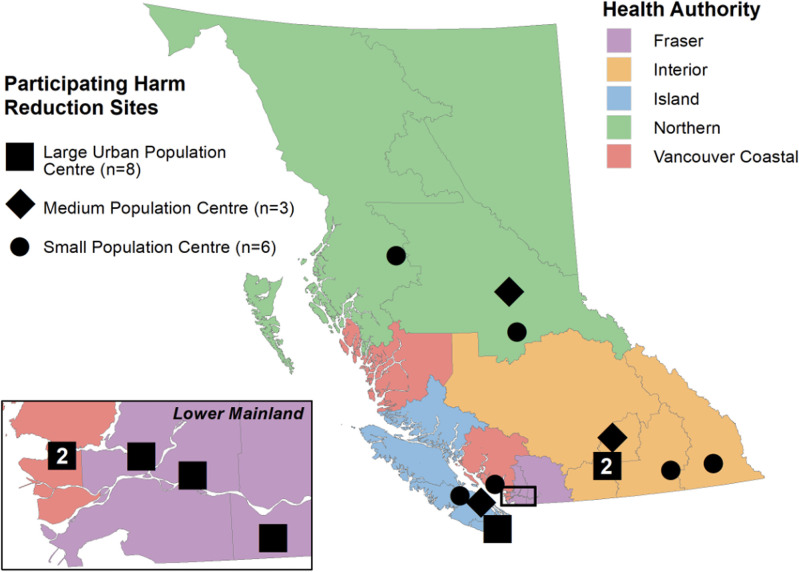

Demographic and drug use variables included BC health authority (Fraser, Interior, Island, Northern and Vancouver Coastal) and urbanicity (large urban, medium urban and small urban population centres) of the site where the survey was administered (see figure 1), age category (≤29, 30–39, 40–49, ≥50, unknown), gender (cis woman, cis man, trans and gender expansive, unknown), self-reported Indigenous identity (First Nations, Métis, Inuit, non-Indigenous, unknown), employment status (employed (working full-time, part-time or paid volunteer), not employed, unknown), housing status (stably housed (living in a private residence or living in another residence—hotel/motel, rooming houses, single room occupancy or social/supportive housing), not stably housed (living in a shelter or having no regular place to stay—homeless, couch surfing, no fixed address), unknown), how frequently the client picked up supplies from a harm reduction site in the last 6 months (never, every day, few times per week, few times per month, once a month or less, unknown), had a cell phone (yes, no, unknown), had a naloxone kit (yes, no, unknown), used an overdose prevention site in the past 6 months (yes, no, unknown), perceived risk of overdose from opioid (yes, no, do not know, unknown), injected any drug in the past 6 months (yes, no, unknown), frequency of drug use in the past month (none, every day, few times per week, few times per month, prefer not to say), witnessed or experienced an opioid overdose in the last 6 months (yes, no, do not know, unknown). Variables that had ‘prefer not to say’ and ‘unknown’ were combined into ‘unknown’. Urbanicity was derived using the Population and Rural Area Classification 2016 system developed from Statistics Canada.

Figure 1.

Map of sites participating in 2021 harm reduction client survey,

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariable analyses with Χ2 tests of independence were conducted for all variables to describe characteristics of PWUD who responded to having seen or heard of a drug alert (table 1). Bivariate logistic regression assessing the relationship between explanatory variables and the outcome variable was conducted for all variables (table 1). A Cochran-Armitage trend test was performed to assess for a trend between age category and the awareness of drug alerts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2021 harm reduction client survey participants who responded to seeing/hearing a drug alert (n=482)

| Characteristics | Saw/heard alert (n=300) n (%) | Did not see/hear alert (n=182) n (%) | Total (n=482) n (%) | Χ2 P value | Bivariable regression P value |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age category | 0.46 | ||||

| ≤29 | 34 (53.1) | 30 (46.9) | 64 (13.3) | Reference | |

| 30–39 | 72 (61.0) | 46 (39.0) | 118 (24.5) | 0.30 | |

| 40–49 | 81 (63.3) | 47 (36.7) | 128 (26.6) | 0.18 | |

| ≥50 | 102 (64.2) | 57 (35.8) | 159 (33.0) | 0.13 | |

| Unknown | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | 13 (2.6) | 0.05 | |

| Gender | 0.059 | ||||

| Cis man | 183 (61.0) | 117 (39.0) | 300 (62.2) | Reference | |

| Cis woman | 104 (62.7) | 62 (37.3) | 166 (34.4) | 0.73 | |

| Trans and gender expansive* | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.9) | 0.98 | |

| Unknown | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (1.5) | 0.84 | |

| Health authority | 0.041 | ||||

| Fraser | 52 (61.2) | 33 (38.8) | 85 (17.6) | 0.61 | |

| Interior | 75 (57.7) | 55 (42.3) | 130 (27.0) | Reference | |

| Island | 81 (70.4) | 34 (29.6) | 115 (23.9) | 0.039 | |

| Northern | 44 (52.4) | 40 (47.6) | 84 (17.4) | 0.45 | |

| Vancouver Coastal | 48 (70.6) | 20 (29.4) | 68 (14.1) | 0.077 | |

| Urbanicity | 0.99 | ||||

| Large urban | 103 (62.0) | 63 (38.0) | 166 (34.4) | Reference | |

| Medium urban | 108 (62.1) | 66 (37.9) | 174 (36.1) | 1.00 | |

| Small urban | 89 (62.7) | 53 (37.3) | 142 (29.5) | 0.91 | |

| Indigenous identity | 0.27 | ||||

| Non-Indigenous | 164 (65.5) | 86 (34.5) | 250 (51.9) | Reference | |

| Indigenous | 117 (57.4) | 87 (42.6) | 204 (42.3) | 0.072 | |

| Unknown | 19 (67.9) | 9 (32.1) | 28 (5.8) | 0.81 | |

| Current employment† | 0.65 | ||||

| Unemployed | 219 (61.3) | 138 (38.7) | 357 (74.1) | Reference | |

| Employed | 67 (64.4) | 37 (35.6) | 104 (21.6) | 0.57 | |

| Unknown | 14 (66.7) | 7 (33.3) | 21 (4.3) | 0.63 | |

| Currently stably housed‡ | 0.88 | ||||

| Yes | 175 (62.7) | 104 (37.3) | 279 (57.9) | Reference | |

| No | 111 (61.3) | 70 (38.7) | 181 (37.6) | 0.76 | |

| Unknown | 14 (63.6) | 8 (34.4) | 22 (4.5) | 0.93 | |

| Harm reduction characteristics | |||||

| Frequency of harm reduction supply pick up in the past 6 months | 0.061 | ||||

| Never | 15 (41.7) | 21 (58.3) | 36 (7.5) | Reference | |

| Every day | 84 (65.6) | 44 (34.4) | 128 (26.6) | 0.011 | |

| Few times a week | 107 (61.1) | 68 (38.9) | 175 (36.3) | 0.034 | |

| Few times a month | 58 (67.4) | 28 (32.6) | 86 (17.8) | 0.0092 | |

| Once a month or less | 25 (69.4) | 11 (30.6) | 36 (7.5) | 0.019 | |

| Unknown | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | 21 (4.3) | 0.44 | |

| Have a cell phone | 0.51 | ||||

| No | 121 (60.2) | 80 (39.8) | 201 (41.7) | Reference | |

| Yes | 161 (63.6) | 92 (36.4) | 253 (52.5) | 0.45 | |

| Unknown | 18 (64.3) | 10 (35.7) | 28 (5.8) | 0.68 | |

| Have a naloxone kit | 0.014 | ||||

| No | 47 (50.5) | 46 (49.5) | 93 (19.3) | Reference | |

| Yes | 242 (65.2) | 130 (34.8) | 372 (77.2) | 0.01 | |

| Unknown | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 17 (3.5) | 0.29 | |

| Used OD prevention site in the last 6 months | 0.011 | ||||

| No | 191 (59.0) | 133 (41.0) | 324 (67.2) | Reference | |

| Yes | 96 (72.2) | 37 (27.8) | 133 (27.6) | 0.0083 | |

| Unknown | 13 (52.0) | 12 (48.0) | 25 (5.2) | 0.50 | |

| Drug use characteristics | |||||

| Perceived risk of opioid OD | 0.0089 | ||||

| No | 164 (58.0) | 119 (42.0) | 283 (58.7) | Reference | |

| Yes | 106 (73.1) | 39 (26.9) | 145 (30.1) | 0.0023 | |

| Do not know | 24 (63.2) | 14 (36.8) | 38 (7.9) | 0.54 | |

| Unknown | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 16 (3.3) | 0.12 | |

| Injected any type of drug in the last 6 months | 0.09 | ||||

| No | 152 (58.7) | 107 (41.3) | 259 (53.7) | Reference | |

| Yes | 135 (66.8) | 67 (33.2) | 202 (41.9) | 0.074 | |

| Unknown | 13 (61.9) | 8 (38.1) | 21 (4.4) | 0.77 | |

| Frequency of use of illicit drugs in the past month | 0.45 | ||||

| Did not use drugs | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 13 (2.7) | Reference | |

| Every day | 198 (61.9) | 122 (38.1) | 320 (66.4) | 0.26 | |

| Few times a week | 57 (67.9) | 27 (32.1) | 84 (17.4) | 0.14 | |

| Few times a month | 18 (60.0) | 12 (40.0) | 30 (6.2) | 0.40 | |

| Unknown | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | 35 (7.3) | 0.39 | |

| Experienced an opioid OD in the past 6 months | 0.29 | ||||

| No | 201 (60.2) | 133 (39.8) | 334 (69.3) | Reference | |

| Yes | 81 (67.5) | 39 (32.5) | 120 (24.9) | 0.16 | |

| Do not know | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (1.7) | 0.56 | |

| Unknown | 14 (70.0) | 6 (30.0) | 20 (4.1) | 0.39 | |

| Witnessed an opioid OD in the past 6 months | 0.000072 | ||||

| No | 68 (47.9) | 74 (52.1) | 142 (29.5) | Reference | |

| Yes | 217 (68.9) | 98 (31.1) | 315 (65.4) | 0.000022 | |

| Do not know | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (1.0) | 0.19 | |

| Unknown | 11 (55.0) | 9 (45.0) | 20 (4.1) | 0.55 | |

*Includes trans man, trans woman, gender non-conforming and other specified gender.

†Employed includes working part-time, full-time or being a paid volunteer.

‡Stably housed includes living in a private residence, living in another residence (hotel/motel, rooming houses, single room occupancy or social/supportive housing). Not stably housed includes living in a shelter or having no regular place to stay (homeless, couch surfing, no fixed address).

OD, overdose.

Based on purposeful model building, all covariates with at least one level with a p value of 0.25 or less in bivariable regression were assessed for inclusion in the final model. In addition, owning a cellphone was included for assessment in the model despite having a p value greater than 0.25 because conceptually it is believed that having regular access to communication and the internet increases the likelihood of seeing a drug alert. After developing the full model, we used backwards selection and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to determine which covariates to include in the final model. Although gender was not statistically significant in the bivariable regression, it was included in the model because of the known effects on health outcomes. We used variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess for collinearity and no VIF was above 4; as such, no further investigation was required, and all covariates of interest remained in the model.

In developing the multivariable logistic regression model, we assessed the following variables as candidates for inclusion in the final model: age category; gender; health authority; urbanicity; owning a cellphone; owning a naloxone kit; Indigenous identity; perceived risk of opioid overdose; injecting any drug in the past 6 months; frequency of substance use in the past month other than or in addition to cannabis, alcohol or tobacco; experiencing an unintentional opioid overdose in the past 6 months; witnessing an accidental opioid overdose in the past 6 months; use of an overdose prevention site in the past 6 months and frequency of harm reduction supply pick up in the last 6 months.

Using backwards selection based on which model resulted in the smaller AIC value, we retained the following variables in the final model: age category, gender, health authority, frequency of harm reduction supply pick up in the past 6 months and witnessing an opioid-related overdose in the past 6 months. Age category and gender were included despite not being selected for using backwards selection because of their conceptual relevance and known differences in health outcomes.

Adjusted ORs and 95% CI were included in the final multivariable logistic regression model. ORs with a p value ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used R version 4.2.0 (22 April 2022) and R Studio version 2022.2.3.492 to conduct all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

To ensure that our analyses represent the realities of PWUD, we consulted the Professionals for Ethical Engagement of Peers (PEEP)—an advisory group of leaders with past or current illicit drug use—on our analyses and interpretations.22 23

Results

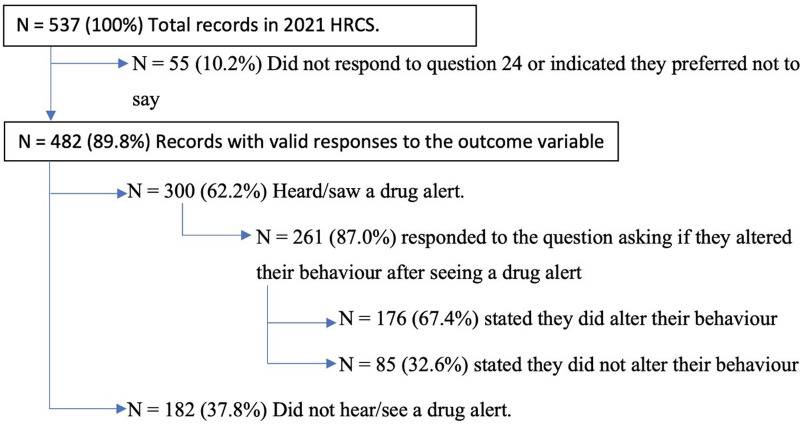

Surveys were completed by 537 eligible participants from across BC and 482 (89.8%) participants had valid responses to the question ‘have you recently seen or heard an alert?’ and were included in our analysis, of these 300 (62.2%) stated they saw/heard an alert (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of responses to the outcome variables of interest. HRCS, harm reduction client survey.

Of the 261 participants who responded to the question asking if they took steps to be safer when using substances after seeing/hearing a drug alert, 176 (67.4%) reported they did subsequently take safer steps (figure 2).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondents. A third of respondents were ≥50 years old and the distribution across urbanicity categories of the site where they participated in the survey were fairly even (29.5% were from small urban centres; 36.1% from medium urban centres and 34.4% from large urban centres). Most respondents were cis men (62.2%), had used an overdose prevention site in the past 6 months (67.2%), did not perceive themselves at risk of an opioid overdose (58.7%), used drugs daily in the past month (66.4%), had not experienced an opioid overdose in the past 6 months (69.3%) and had witnessed an overdose due to opioids in the past 6 months (65.4%). Interior was used as the health authority reference category as it had the largest sample size. With respect to age categories, a Cochran-Armitage trend test indicated that there was an increasing trend with known age and the observation of a drug alert (p<0.03).

Table 2 shows where participants reported seeing/hearing drug alerts. Responses were not mutually exclusive as participants were able to select more than one option on the survey. Almost half (n=143) of the participants reported that they became aware of the alert through a friend or peer.

Table 2.

Where and how participants reported seeing or hearing a drug alert

| Where alerts were noticed | No. of clients* (%)† |

| Heard from a friend or peer network | 143 (48) |

| At a site attended | |

| Harm reduction site (e.g. Supervised consumption site/overdose pevention site or community organisation) | 127 (42) |

| Healthcare provider | 36 (12) |

| Public dissemination | |

| Posters on the street | 70 (23) |

| On the news/media | 61 (20) |

| Through phone or internet | |

| On social media (e.g. Facebook or Twitter) | 47 (16) |

| Received an email or text | 24 (8) |

| Other | 38 (13) |

*Responses are not mutually exclusive.

†% of n=300 who report seeing/hearing a drug alert.

We performed bivariable regression analysis on harm reduction supply pick up frequency and perceived opioid overdose risk; a χ2 test indicated that the two variables are associated (p<0.0000001), suggesting that confounding is likely. Therefore, despite perceived risk of opioid overdose being included in backwards selection, it was removed from the final model because of its potential confounding effects on harm reduction supply pick up frequency. We retained frequency of supply pick up as every level with a known frequency of supply pick up was statistically significant in the bivariable regression and, conceptually, individuals who use harm reduction services more frequently would be more likely to observe a drug alert.

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs are presented in table 3 for the variables included in the final model. The adjusted odds for participants from the Island Health Authority seeing/hearing a drug alert were 2.14 times the odds (95% CI: 1.20 to 3.85) the participants from the Interior Health Authority seeing/hearing a drug alert. In addition, the odds of participants who picked up harm reduction supplies a few times per month in the past 6 months seeing/hearing a drug alert were 2.73 (95% CI: 1.17 to 6.52) times the odds of participants who had not picked up harm reduction supplies in the past 6 months. Interestingly, the adjusted odds of participants who picked up harm reduction supplies more frequently (every day or a few times per week) seeing/hearing a drug alert was not significantly different from those who had not picked up supplies in the past 6 months. Witnessing an opioid-related overdose also provided significant findings—data indicate that the odds of participants who witnessed an opioid-related overdose in the past 6 months seeing/hearing a drug alert were 2.76 (95% CI: 1.76 to 4.36) times the odds of participants who did not witness an opioid-related overdose in the past 6 months.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for variables included in the final model (n=482)

| Characteristics | UOR (95% CI) | P value for UOR | AOR (95% CI) | P value for AOR |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age category | ||||

| ≤29 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 30–39 | 1.38 (0.75 to 2.56) | 0.30 | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.38) | 0.55 |

| 40–49 | 1.52 (0.83 to 2.80) | 0.18 | 1.34 (0.69 to 2.59) | 0.38 |

| ≥50 | 1.58 (0.88 to 2.85) | 0.13 | 1.23 (0.63 to 2.38) | 0.54 |

| Unknown | 4.85 (1.18 to 33.01) | 0.05 | 6.55 (1.41 to 48.14) | 0.029 |

| Gender | ||||

| Cis man | Reference | Reference | ||

| Cis woman | 1.07 (0.73 to 1.59) | 0.73 | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.58) | 0.86 |

| Trans and gender expansive† | 3 680 000 (0.00 to ∞) | 0.98 | 8 500 000 (0.00 to ∞) | 0.98 |

| Unknown | 0.85 (0.18 to 4.39) | 0.84 | 0.44 (0.08 to 2.53) | 0.33 |

| Health authority | ||||

| Interior | Reference | Reference | ||

| Fraser | 1.16 (0.66 to 2.03) | 0.61 | 1.13 (0.62 to 2.07) | 0.68 |

| Island | 1.75 (1.03 to 2.99) | 0.039 | 2.14 (1.20 to 3.85) | 0.01* |

| Northern | 0.81 (0.46 to 1.40) | 0.45 | 0.84 (0.46 to 1.52) | 0.56 |

| Vancouver Coastal | 1.76 (0.95 to 3.34) | 0.077 | 1.88 (0.96 to 3.75) | 0.07 |

| Harm reduction characteristics | ||||

| Frequency of harm reduction supply pick up in the past 6 months | ||||

| Never | Reference | Reference | ||

| Every day | 2.67 (1.26 to 5.78) | 0.011 | 1.96 (0.86 to 4.50) | 0.11 |

| Few times a week | 2.20 (1.07 to 4.64) | 0.034 | 1.79 (0.83 to 3.96) | 0.14 |

| Few times a month | 2.90 (1.31 to 6.57) | 0.0092 | 2.73 (1.17 to 6.52) | 0.021* |

| Once a month or less | 3.18 (1.23 to 8.64) | 0.019 | 2.72 (0.99 to 7.79) | 0.055 |

| Unknown | 1.54 (0.52 to 4.62) | 0.44 | 1.21 (0.36 to 4.11) | 0.76 |

| Drug use characteristics | ||||

| Witnessed an opioid OD in the past 6 months | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.41 (1.61 to 3.63) | 0.000022 | 2.76 (1.76 to 4.36) | 0.00001* |

| Do not know | 4.35 (0.62 to 86.29) | 0.19 | 3.91 (0.47 to 82.13) | 0.25 |

| Unknown | 1.33 (0.52 to 3.49) | 0.55 | 1.68 (0.60 to 4.85) | 0.32 |

Abbreviations: UOR, unadjusted odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Significant at 0.05.

†Includes trans man, trans woman, gender non-conforming and other specified gender.

OD, overdose.

Discussion

In a 2021 cross-sectional survey administered at harm reduction sites across BC, we found over 60% of participants reported seeing/hearing a recent drug alert and more than two-thirds who saw/heard an alert reported changing their substance use behaviour to be safer. We identified associations with seeing/hearing an alert and demographic factors (such as age and geography but not gender), frequency of supply pick up and witnessing an overdose in past 6 months. However, we found no association with substance use factors such as frequency of substance use or injecting drugs.

Like previous studies we found that the most common source of alert information for our participants was from peers or through peer networks.24 Other studies confirm that the source of information is a valuable element in risk assessment when using drugs.25 For instance, participants in one study expressed a high level of trust for their drug dealers, that was based on the length of the relationship, drug supply consistencies and their communication.25 Our study highlights that drug alerts have a role to play in encouraging safer substance use and also the value of peer networks in transmitting information. Therefore, methods of disseminating accurate information through peer networks in order to effectively and timely share critical information should be further explored and enhanced.

A Cochran-Armitage trend test indicated that the proportion of individuals who reported seeing/hearing a drug alert increases with each age category. Individuals from different age groups may have different methods of communication. For example, younger individuals may prefer digital methods, while older age groups may prefer word of mouth and belong to larger networks of people who use drugs.26 Age is an important consideration when disseminating drug alerts to ensure that all individuals receive the message in a timely and accessible manner. It also highlights the need for clear and correct information to be made available to ensure messaging by word of mouth is accurate. Consultation with PEEP also suggested that younger individuals may be less aware of drug alerts for the following reasons: they may feel that they are less at risk when using substances and they may intentionally ignore messaging surrounding drug use because of the stigma associated with it.27

Compared with participants from Interior Health, those from Island Health had significantly higher odds of reporting seeing/hearing a drug alert. The decision to issue a drug alert is generally based on a number of factors including drug toxicity deaths, emergency health service calls, drug checking and community input.7 11 12 However, the availability of these factors may vary by region and therefore make it difficult to directly compare health regions. Resources such as drug checking should be made more consistently available across the province to enable standardisation of the alerting process.

Based on our analysis, those who picked up harm reduction supplies a few times per month (compared with those who did not pick up supplies in the past 6 months) were statistically significantly more likely to report seeing/hearing a drug alert. Paradoxically, we found that individuals who attended harm reduction sites a couple of times a week or daily were not significantly more likely to report seeing/hearing a drug alert. Although posted drug alerts are usually removed after 2 weeks, a person who attends the harm reduction supply site frequently will have been exposed to the same alerts on multiple occasions. Therefore, there may be ‘alert fatigue’, a phenomenon described in healthcare when frequent alerts may desensitise people, and as a result they may ignore or fail to respond appropriately to such warnings.28 Alert fatigue has also been reported in the context of drug alerts; therefore, ways of minimising alert fatigue should be further explored.24 A previous study found that individuals who defined their substance use as a chronic condition expressed that they were desensitised to the risk of overdose.29 During our consultation with PEEP, members suggested that those who attend harm reduction supply sites frequently may only be there for a brief time period, while those who attend sites less frequently may be there for longer as they may collect more supplies. This may partially explain the trend we observed, however, we cannot determine differences in drug use behaviour or time spent at the sites between those who visited harm reduction service sites more and less frequently.

Individuals who witnessed an opioid-related overdose in the past 6 months had more than two and a half times the odds of reporting seeing/hearing a drug alert compared with participants who did not witness an opioid-related overdose. Those who witnessed an overdose have previously been found to change harm reduction behaviours; in a cohort study in BC, witnessing that an overdose was found to be positively associated with using drug checking services.30 Therefore, those who witness an overdose may be more sensitised to information surrounding drug alerts; however, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we are unable to determine causality. In contrast, we found no association with experiencing an overdose in the past 6 months and seeing/hearing a drug alert. This is consistent with previous studies which have identified that people often underestimate their own risk of an overdose. For example, despite a high level of fentanyl risk knowledge, most did not translate this knowledge into a personal risk of having an overdose, and people who used opioids and injected more frequently as well as those who were older were less likely to perceive themselves as being at risk of an overdose.31 32 The implications of our findings and contextual realities should be further explored using qualitative methods.

Limitations

The data used in this study are cross-sectional and as such we cannot make conclusions about temporal relationships. Additionally, generalisability is limited in this study as participants were a convenience sample of PWUD who accessed harm reduction services/sites and thus the findings may not apply to all PWUD in the province. The survey also relied on individuals’ reporting and recollection of their behaviours which introduces recall bias and there is potential for social desirability for example, when asked if they had seen an alert did they take steps to be safer. Data for this study was collected during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, the immediate restrictions and decreased availability of harm reduction services seen in spring 2020 had been addressed and individuals were able to access in-person harm reduction services in 2021.

Conclusions

Drug alerts disseminate important and timely information about the circulating drug supply to enable people to use more safely. Our study found most people using harm reduction services were aware of drug alerts—mainly through hearing about them through a friend or peer, and that two-thirds who became aware of an alert subsequently changed their drug use behaviour to be safer. Considering communication with friends and peers was the most common method of information sharing, developing effective strategies to disseminate critical information related to the drug supply among social networks should be a priority when developing drug alerts. Drug alerts must use a variety of modes to ensure that they are accessible to those who need to know. Further research is needed to ensure that alerts are reaching the appropriate audiences and to identify how to better communicate to younger PWUD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for participants who shared their valuable experiences by completing the harm reduction client survey. We also thank Kristi Papamihali for developing the 2021 harm reduction client survey (HRCS) with input from stakeholders. We are thankful for harm reduction site staff and volunteers, and regional harm reduction coordinators for their implementation and data collection of the 2021 HRCS and for their commitment to supporting the community. We thank the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users for piloting the HRCS. We would like to thank the Professionals for Ethical Engagement of Peers for their contributions and thoughtfulness to the development of the HRCS, for reviewing and interpreting results and for their input to this manuscript. We respectfully acknowledge that this study and work took place on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of 205 First Nations and that we live and work on the lands of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.

Footnotes

Contributors: KD conducted the initial thematic analysis and data analysis. BG led initial data collection and project coordination. Authors MF, LL and JAB provided data interpretation. JAB was the principal investigator and directed data interpretation as well as project coordination. All authors (KD, MF, BG, JL, LL, JL, KL, BG, JM and JAB) provided constructive input into the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission. JAB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The harm reduction client survey (HRCS) was led by principal investigator and author Dr Jane A Buxton. The HRCS was funded by Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (Grant 1819-HQ-000054).

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries there), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The harm reduction client survey, 2021 was approved by the University of British Columbia Office Behavioural Research Ethics (#H07-00570). Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to commencing the survey.

References

- 1.Ahmad F, Cisewski J, Rossen L, et al. Vital statistics rapid release-provisional drug overdose data [online]. 2022. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- 2.Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses . Apparent opioid and stimulant toxicity deaths: Surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/src/doc/SRHD/Update_Deaths_2022-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses . Opioid and stimulant poisoning hospitalizations: Surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/src/doc/SRHD/Update_Hospitalizations_2022-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses . Suspected opioid-related overdoses based on emergency medical services: surveillance of opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022. Available: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olding M, Boyd J, Kerr T, et al. And we just have to keep going: task shifting and the production of burnout among overdose response workers with lived experience. Soc Sci Med 2021;270:113631. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health . Provincial health officer declares public health emergency. 2016. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2016HLTH0026-000568

- 7.BC Coroners . Illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC: January 1, 2012 – August 31, 2022 [online]. Vancouver: Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General, 2022. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Safety and Solicitor General . Ten thousand lives lost to illicit drugs since Declaration of public health emergency. BC Gov News 2022. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PSSG0056-001250 [Google Scholar]

- 9.BC Coroners . Illicit drug toxicity type of drug data: data to August 31, 2022. Vancouver: Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General, 2022. Available: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/birth-adoption-death-marriage-and-divorce/deaths/coroners-service/statistical/illicit-drug-type.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.BCCDC Harm Reduction . Information for alerts and people who use substances. n.d. Available: https://towardtheheart.com/alerts

- 11.BC Centre for Substance Use . Drug checking [online]. n.d. Available: https://www.bccsu.ca/drug-checking/

- 12.University of Victoria . Vancouver island drug checking project [online]. n.d. Available: https://substance.uvic.ca/

- 13.Giné CV, Espinosa IF, Vilamala MV. New psychoactive substances as adulterants of controlled drugs. A worrying phenomenon? Drug Test Anal 2014;6:819–24. 10.1002/dta.1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toward the heart. n.d. Available: https://towardtheheart.com/for-pwus

- 15.Kerr T, Small W, Hyshka E, et al. It's more about the heroin: injection drug users' response to an overdose warning campaign in a Canadian setting. Addiction 2013;108:1270–6. 10.1111/add.12151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton JA, Spearn B, Amlani A, et al. The British Columbia drug overdose and alert partnership: interpreting and sharing timely illicit drug information to reduce harms. Jcswb 2019;4:4. 10.35502/jcswb.92 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicol JJE, Yarema MC, Jones GR, et al. Deaths from exposure to paramethoxymethamphetamine in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada: a case series. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E83–90. 10.9778/cmajo.20140070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smit‐Rigter LA, Van der Gouwe D. The neglected benefits of drug checking for harm reduction. Intern Med J 2020;50:1024. 10.1111/imj.14953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keijsers L, Bossong MG, Waarlo AJ. Participatory evaluation of a Dutch warning campaign for substance-users. Health, Risk & Society 2008;10:283–95. 10.1080/13698570802160913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smit-Rigter LA, Van der D. The drugs information and monitoring system (DIMS): factsheet on drug checking in the Netherlands. 2019. Available: https://www.trimbos.nl/docs/cd3e9e11-9555-4f8c-b851-1806dfb47fd7.pdf

- 21.Kuo M, Shamsian A, Tzemis D, et al. A drug use survey among clients of harm reduction sites across British Columbia, Canada, 2012. Harm Reduct J 2014;11:13. 10.1186/1477-7517-11-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xavier J, Greer A, Pauly B, et al. There are solutions and I think were still working in the problem: the limitations of decriminalization under the good samaritan drug overdose act and lessons from an evaluation in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Drug Policy 2022;105:S0955-3959(22)00133-5. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song K, Buxton JA. Peer engagement in the BCCDC harm reduction program: A narrative summary. Vancouver, BC: BC Centre for Disease Control, 2021. Available: https://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/PubDocs/bcdocs2022/725438/725438_Peer_engagement_in_the_BCCDC_harm_reduction_program.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soukup-Baljak Y, Greer AM, Amlani A, et al. Drug quality assessment practices and communication of drug alerts among people who use drugs. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:1251–7. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardwell G, Boyd J, Arredondo J, et al. Trusting the source: the potential role of drug dealers in reducing drug-related harms via drug checking. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;198:1–6. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loyal J, Buxton JA. Exploring the communication of drug alerts with people who use drugs and service providers. Vancouver, BC: BC Centre for Disease Control, 2021. Available: https://towardtheheart.com/assets/uploads/1637875132V20vRO8kYDO7akKH2KdKTOP5wZtk8P70uMca4lP.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunn CM, Maschke A, Harris M, et al. Age-based preferences for risk communication in the fentanyl era: a lot of people keep seeing other people die and th’t's not enough for them Addiction 2021;116:1495–504. 10.1111/add.15305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality . Patient safety network alert fatigue us department & human services. 2019. Available: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/alert-fatigue#:~:text=The%20term%20alert%20fatigue%20describes,respond%20appropriately%20to%20such%20warnings

- 29.Harris MTH, Bagley SM, Maschke A, et al. Competing risks of women and men who use fentanyl: the number one thing I worry about would be my safety and number two would be overdose. J Subst Abuse Treat 2021;125:S0740-5472(21)00039-8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beaulieu T, Hayashi K, Nosova E, et al. Effect of witnessing an overdose on the use of drug checking services among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2020;46:506–11. 10.1080/00952990.2019.1708087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moallef S, Nosova E, Milloy MJ, et al. Knowledge of fentanyl and perceived risk of overdose among persons who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Public Health Rep 2019;134:423–31. 10.1177/0033354919857084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe C, Santos G-M, Behar E, et al. Correlates of overdose risk perception among illicit opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;159:234–9. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.