Abstract

In the human gut, the growth of the pathogen Clostridioides difficile is impacted by a complex web of interspecies interactions with members of human gut microbiota. We investigate the contribution of interspecies interactions on the antibiotic response of C. difficile to clinically relevant antibiotics using bottom-up assembly of human gut communities. We identify 2 classes of microbial interactions that alter C. difficile’s antibiotic susceptibility: interactions resulting in increased ability of C. difficile to grow at high antibiotic concentrations (rare) and interactions resulting in C. difficile growth enhancement at low antibiotic concentrations (common). Based on genome-wide transcriptional profiling data, we demonstrate that metal sequestration due to hydrogen sulfide production by the prevalent gut species Desulfovibrio piger increases the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of metronidazole for C. difficile. Competition with species that display higher sensitivity to the antibiotic than C. difficile leads to enhanced growth of C. difficile at low antibiotic concentrations due to competitive release. A dynamic computational model identifies the ecological principles driving this effect. Our results provide a deeper understanding of ecological and molecular principles shaping C. difficile’s response to antibiotics, which could inform therapeutic interventions.

This study examines how interactions between constituent members of the human gut microbiome influence the pathogen C. difficile’s response to clinically relevant antibiotics, providing key insights into ecological principles and molecular mechanisms that influence antibiotic susceptibility in this health-relevant system.

Introduction

The bacterial pathogen Clostridioides difficile can infect the human gastrointestinal tract, an environment teeming with a dense microbiota. Gut microbiota can inhibit C. difficile’s growth and ability to persist over time in the human gut, a phenomenon known as colonization resistance [1]. The key role of colonization resistance is illustrated by the increased risk of C. difficile infection after treatment with antibiotics that decimate the microbiota [2] and by the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplants from healthy human donors in eliminating recurrent C. difficile infections [3]. Previous studies have provided a deeper understanding of interactions between gut microbiota and C. difficile. For example, interspecies interactions between individual gut microbes and C. difficile have been studied in vitro and analyses of human microbiome data have identified gut microbes whose presence or absence is associated with altered outcomes of C. difficile infection [4–6]. Multiple mechanisms of interaction have been determined, such as inhibition of C. difficile germination by Clostridium scindens via production of secondary bile acids [6] and promotion of C. difficile growth by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron via succinate cross-feeding [7]. While much is known about how the microbiota impacts C. difficile growth, how the microbiota impacts C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility is largely unknown.

Similar to other pathogens, C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility has been studied using in vitro experiments of monoculture growth. However, monoculture experiments do not consider how interactions with resident community members can modify the antibiotic susceptibility of a pathogen. For example, monospecies antibiotic susceptibility of the pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa did not always correlate with the efficacy of treatment for polymicrobial infections [8]. If microbial interactions substantially decrease the pathogen’s antibiotic susceptibility, treatments based on monoculture susceptibility to antibiotics may not be effective in eradicating the pathogen. Alternatively, if communities increase the pathogen’s antibiotic susceptibility, the standard antibiotic dosage may exceed the dose needed to eradicate the pathogen, yielding unnecessary and avoidable disruption to the native microbiota. Understanding how constituent members of microbiota alter a pathogen’s susceptibility to an antibiotic could be used to guide the design of treatments to eradicate the pathogen.

Previous studies have shown that interspecies interactions can alter a given microbe’s response to antibiotics by increasing or decreasing susceptibility compared to monoculture [9]. One example is exposure protection, where susceptible microbes are protected from an antibiotic by species that degrade the antibiotic [10]. In addition, a previous study showed that an increase in antibiotic susceptibility occurred when the growth of a resistant microbe depended on cross-feeding with another organism that was susceptible to the antibiotic [11].

While previous studies have identified specific types of interspecies interactions that impact antibiotic susceptibility, the prevalence of susceptibility-altering microbial interactions across different microbial communities is not well understood. In a human urinary tract infection community, around a third of total interactions between species were estimated to yield a change in the susceptibility to 2 different antibiotics based on spent media experiments [12]. Studies of a fruit fly microbiome, a multispecies wound infection biofilm, and a multispecies brewery biofilm each identified a change in antibiotic susceptibility of a given species in the community compared to monospecies [13–15]. By contrast, no significant changes in antibiotic susceptibility were observed for 15 characterized species in a community of human gut microbes or an Escherichia coli pathogen introduced into a porcine microbiome [16,17]. Based on this observed variation in the contribution of interspecies interactions to antibiotic susceptibility across different systems, it is not known whether microbial interactions can impact C. difficile’s antibiotic susceptibility.

We used a diverse human gut community [4] to study the impact of microbial interactions on C. difficile’s antibiotic susceptibility. We focused on 2 antibiotics, vancomycin and metronidazole, that are used to treat C. difficile infections. Vancomycin is a glycopeptide that inhibits cell wall synthesis whose activity is specific to gram-positive bacteria [18]. Metronidazole is a DNA-damaging agent that is effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Metronidazole is a prodrug which is inactive until its nitro group is reduced to nitroso radicals in the cytoplasm of anaerobic bacteria [19]. The proposed mechanism of metronidazole reduction is due to the cofactors ferredoxin and/or flavodoxin in reactions catalyzed by multiple enzymes including reductases, hydrogenases, and pyruvate ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) [20–22]. Metronidazole, previously a recommended first-line treatment, is now only recommended in rare cases due to an observed decrease in its clinical effectiveness [23,24].

Using a bottom-up approach, we perform a detailed and quantitative characterization of how human gut microbes impact C. difficile’s response to these antibiotics. We show that gut microbes infrequently alter C. difficile’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), but gut microbes frequently impact C. difficile’s response to subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. In communities with antibiotic-sensitive species that also compete with C. difficile, we observe that C. difficile’s growth is enhanced in the presence of low concentrations of antibiotics due to competitive release. A dynamic ecological model representing the antibiotic recapitulates these trends. In addition, we demonstrate that Desulfovibrio piger substantially increases C. difficile’s MIC for metronidazole. We investigate the mechanism determining the increased MIC of C. difficile using transcriptional profiling and media perturbations. Our data suggest D. piger’s impact on the environment induces a metal starvation transcriptional response in C. difficile, leading to down-regulation of enzymes required to reduce metronidazole to its active form. In sum, biotic interactions shape C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility at both subinhibitory and minimal inhibitory concentration regimes via distinct mechanisms. These results highlight the need to consider biotic interactions in the design of future therapeutic treatments to eradicate pathogens.

Results

The minimum inhibitory concentration of C. difficile to metronidazole or vancomycin is modified by a subset of gut microbes in pairwise communities

C. difficile infections occur in the context of complex resident gut communities. However, antibiotic treatments to eliminate C. difficile infection are designed based on the susceptibility of C. difficile in monoculture, which neglect the role of interspecies interactions in shaping antibiotic susceptibility. Understanding how the gut microbiota alters C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility could inform the treatment of C. difficile by antibiotics. To investigate this question, we evaluated C. difficile’s response to antibiotics in the presence of synthetic communities of gut microbes (Fig 1A). The 13-member human gut community was designed to span the phylogenetic diversity of the human gut microbiome. The interactions between these gut microbes and C. difficile have been deciphered in the absence of antibiotics [4] (Fig 1B). We selected the antibiotics metronidazole and vancomycin for their clinical relevance in the treatment of C. difficile infections and for the differences in their activity spectra. Metronidazole has broad spectrum activity against the 13 gut microbes, whereas the activity of vancomycin is specific for gram-positive species. To determine how C. difficile would respond to both low and high antibiotic concentrations in the human gut, we characterized C. difficile’s MIC and its growth in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations across a range of ecological contexts (Fig 1C).

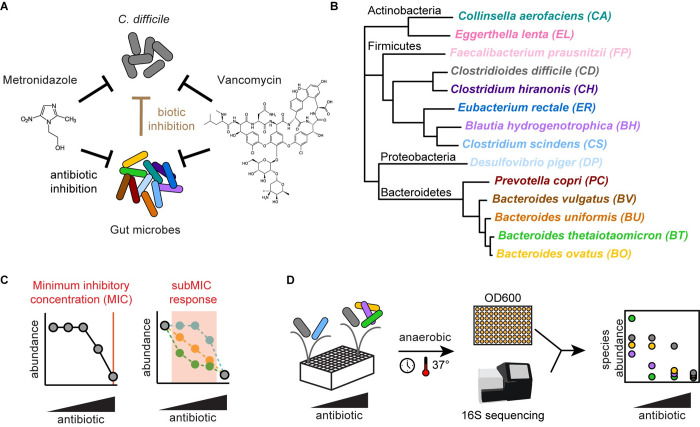

Fig 1. Investigating the effects of interspecies interactions on the clinically relevant antibiotic response of C. difficile in human gut communities.

(A) Schematic of factors affecting C. difficile growth in synthetic gut communities in the presence of antibiotics metronidazole or vancomycin. The DNA-damaging antibiotic metronidazole and the cell wall inhibitor vancomycin can inhibit C. difficile and gut microbes (black arrows). Biotic inhibition by gut microbes (brown arrow) inhibits C. difficile. (B) Phylogenetic tree of 14-member human gut community, spanning 4 major phyla of gut microbiota and pathogen C. difficile. Black text indicates phylum name. Colored text indicates species name. Phylogeny based on a concatenated alignment of 37 marker genes [25]. (C) Schematic of 2 aspects of the response of a microbial population to antibiotics: the MIC and the subMIC response. (D) Schematic of methods to determine the antibiotic susceptibility of multispecies communities. Communities are incubated anaerobically in microtiter plates. Absolute abundance is determined by multiplying optical density (OD600) by relative abundance based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; subMIC, sub-minimum inhibitory concentration.

To determine the antibiotic susceptibility of C. difficile in communities, we used a broth dilution method based on the clinical method detailed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [26] (Methods). We inoculated communities in liquid culture containing a 2-fold dilution series of antibiotics. After incubation, we determined the absolute abundance of each species in the communities at a fixed time point (48 h) by multiplying the community optical density at 600 nm (OD600) by its relative abundance determined via 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Fig 1D). The MIC for each species in the community was determined as the lowest antibiotic concentration where growth at 48 h was below a threshold (Methods).

Using this method, we determined the MIC of each species in monoculture (Fig 2A) and in each pairwise community containing C. difficile (Fig 2B and 2C). Consistent with the mechanism of the antibiotics, all species were susceptible to metronidazole in the range of antibiotics tested, whereas gram-negative species (Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria phyla, Fig 1D) were not susceptible to vancomycin (Figs 2A and S1A and S1B).

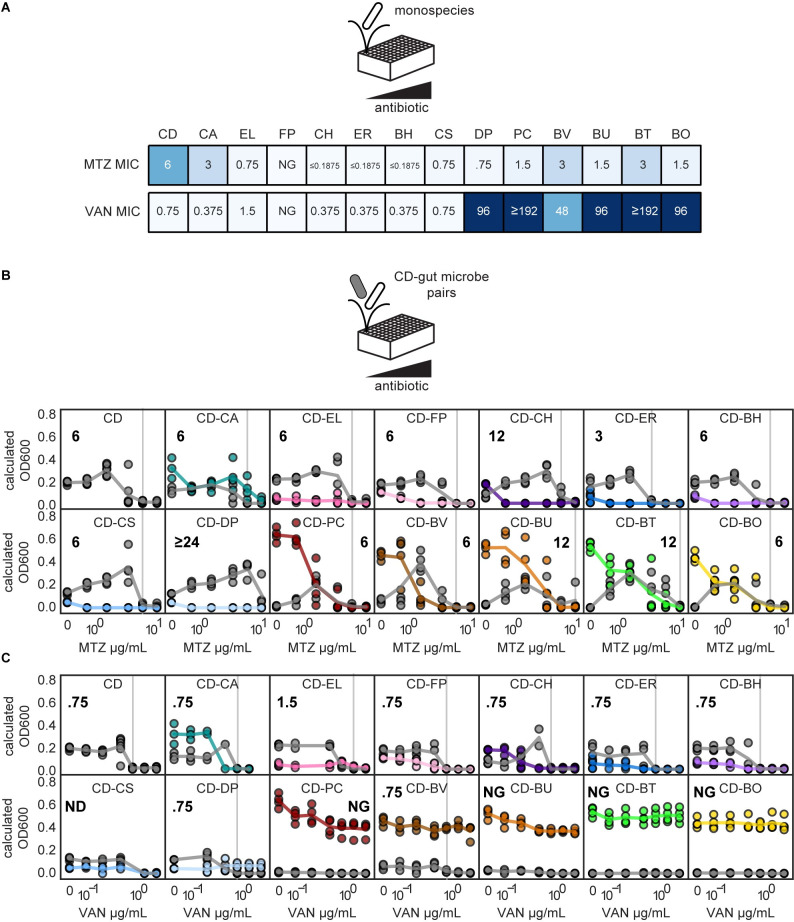

Fig 2. C. difficile response to metronidazole or vancomycin is modified in specific pairwise communities.

(A) Heatmaps of MIC of monocultures in the presence of metronidazole (MTZ) or vancomycin (VAN). Species indicated by 2-letter species code (Fig 1B). (B, C) Line plots of species absolute abundance at 48 h as a function of antibiotic concentration for C. difficile in monoculture or C. difficile in pairwise communities. Each x-axis is semi-log scale. The values on the y-axis are calculated OD600 (OD600 multiplied by relative abundance from 16S rRNA gene sequencing). Data points indicate individual biological replicates. Lines indicate the average of n = 1 to n = 8 biological replicates. Vertical gray line and bold number indicate MIC of C. difficile in each condition. Color indicates species (Fig 1B). The data underlying all panels in this figure can be found in DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7626486. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

In most pairwise communities, the metronidazole and vancomycin MICs of C. difficile were unchanged compared to monoculture. Across metronidazole and vancomycin conditions, the MIC of C. difficile was unchanged in 15 pairwise communities and displayed a moderate difference (2-fold) in 5 pairwise communities compared to monospecies (Fig 2B and 2C). However, C. difficile had a large change in MIC (≥4-fold) in coculture with D. piger (metronidazole MIC increased from 6 μg/mL to greater than or equal to 24 μg/mL) (Fig 2B). In the remaining 4 pairwise communities, C. difficile’s growth was strongly inhibited in all concentrations and no MIC could be calculated (Fig 2C, indicated as “NG”). In sum, the MIC of C. difficile was infrequently impacted by pairwise interspecies interactions in the human gut community.

For select pairwise communities, we quantified C. difficile abundance using both OD600 multiplied by 16S rRNA gene sequencing relative abundance and count of colony-forming units (CFUs) on C. difficile selective agar plates to validate the OD600-based absolute abundance method (S2A Fig). Our results showed that CFU counting and the OD600-based absolute abundance method yielded the same MIC value in 11 out of 12 conditions (S2B and S2C Fig). In 1 condition, C. difficile’s growth was strongly inhibited below the MIC threshold for all concentrations. Therefore, an MIC could not be determined using the OD600-based method, although an MIC could be revealed using the CFU method. Overall, these trends demonstrate that the OD600-based absolute abundance method is a reliable way to measure C. difficile MIC, although the 2 methods can vary in sensitivity.

Enhancement of C. difficile abundance in pairwise communities in the presence of low antibiotic concentrations

Pathogens may encounter antibiotic concentrations lower than the MIC during antibiotic treatments. If the pathogen has gained resistance to the antibiotic, the entire dose regimen could be subinhibitory. Alternatively, even if the target dose is greater than the MIC, sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (subMICs) can occur at the beginning and end of dosing regimens and between daily dosages [27]. Therefore, we investigated the role of microbial interactions on C. difficile’s response to subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations (concentrations lower than C. difficile’s MIC or subMICs).

In many pairwise communities, C. difficile’s abundance was similar or reduced in the subMIC range than in the absence of antibiotic (Fig 2B and 2C). However, in a subset of pairwise communities, C. difficile’s abundance in the subMIC range was enhanced compared to the absence of antibiotic (Fig 2B and 2C). For example, C. difficile monospecies abundance was similar in the presence of 0.75 μg/mL metronidazole and the absence of antibiotic. However, in the presence of B. thetaiotaomicron, the abundance of C. difficile was significantly higher in the presence of 0.75 μg/mL metronidazole than in the absence of antibiotic (Fig 2B). To provide further insights, we computed the subMIC fold change at each subMIC, defined as the species absolute abundance at the given subMIC divided by the species absolute abundance in the absence of antibiotic (Fig 3A). Using this metric, C. difficile’s growth was enhanced for at least 1 subMIC in 1 pairwise community in the presence of vancomycin and 11 pairwise communities in the presence of metronidazole (Figs 3B and S3A and S3B). In 7 pairwise communities, the growth enhancement of C. difficile in the presence of metronidazole was significantly greater than the enhancement observed for the C. difficile monoculture in the presence of metronidazole (Fig 3B). In sum, our results illustrate that approximately half of the species altered C. difficile’s response to low concentrations of metronidazole.

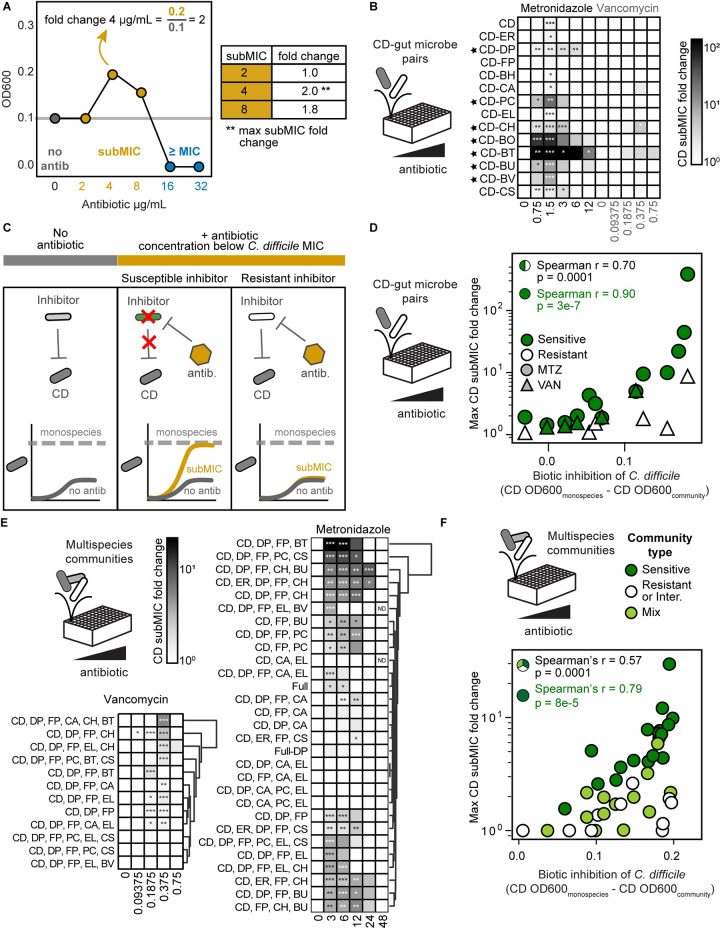

Fig 3. C. difficile growth is enhanced in communities with antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitors in the presence of antibiotic concentrations lower than the MIC.

(A) Schematic of subMIC fold change metric using example data. The x-axis is semi-log scale. Table indicates subMIC fold changes for the 3 subMICs (2, 4, and 8 μg/mL) in this example. Maximum subMIC fold change (indicated by **) is defined as the largest fold change across all subMICs. (B) Heatmap of subMIC fold changes for C. difficile in pairwise communities at each concentration at a 48 h. Shading indicates subMIC fold change. SubMIC fold change is calculated as the average C. difficile absolute abundance at the subMIC divided by the average C. difficile absolute abundance in the absence of antibiotic, where the average is of n = 1 to n = 8 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) between C. difficile OD600 at subMIC and C. difficile OD600 in the absence of antibiotic according to an unpaired t test. Black stars indicate pairs with a maximum subMIC fold change significantly greater than the maximum subMIC fold change of C. difficile monospecies (p < 0.05 based on an unpaired t test). (C) Schematic of C. difficile growth in the presence of antibiotic sensitive and resistant inhibitors. (D) Scatterplot of maximum C. difficile subMIC fold change in pairwise communities as a function of the degree of biotic inhibition of C. difficile in pairwise communities for metronidazole (MTZ, circles) and vancomycin (VAN, triangles). Biotic inhibition of C. difficile (x-axis) is defined as the average C. difficile OD600 in monospecies minus the average C. difficile OD600 in the pairwise community in no antibiotic conditions. The maximum C. difficile subMIC fold change (y-axis) is the maximum of the C. difficile subMIC fold change across all subMICs at 48 h. The subMIC fold change is calculated as in panel B, with n = 1 to n = 8 biological replicates. Species are classified as sensitive if the species monospecies MIC was less than the monospecies MIC of C. difficile and resistant if the species monospecies MIC was greater than or equal to the monospecies MIC of C. difficile. Each point represents 1 pairwise community in metronidazole or vancomycin. The Spearman correlation is annotated for all data points (black) and for pairwise communities with sensitive gut microbes only (green). (E) Heatmap of subMIC fold changes for C. difficile in multispecies communities at each concentration of metronidazole and vancomycin at 48 h. Shading indicates subMIC fold change. SubMIC fold change is calculated as in panel B, with n = 1 to n = 4 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) between C. difficile OD600 at subMIC and C. difficile OD600 in the absence of antibiotic according to an unpaired t test. Communities clustered by subMIC fold change using Euclidean distance hierarchical clustering. “Full” indicates 14-member community, “Full-DP” indicates 13-member community containing all species except DP. (F) Scatterplot of maximum C. difficile subMIC fold change in multispecies communities as a function of the degree of biotic inhibition of C. difficile in multispecies communities for metronidazole (circles) and vancomycin (triangles). Biotic inhibition of C. difficile (x-axis) is calculated as in panel D. The maximum C. difficile subMIC fold change (y-axis) is calculated as in panel B, with n = 1 to n = 4 biological replicates. Community type is sensitive (“Sens.”) if all species excluding C. difficile are sensitive inhibitors. Community type is resistant or intermediate (“Resis. or Intermed.”) if all species excluding C. difficile are either intermediate-inhibitors or resistant-inhibitors. Community type is considered “mix” if the given community contains both sensitive inhibitors and resistant- or intermediate-inhibitors. Species are categorized as biotic inhibitors if the absolute abundance of C. difficile in the presence of this species was significantly lower than the absolute abundance of C. difficile in monospecies, in the absence of antibiotics, as determined by an unpaired t test. Species are classified as sensitive and resistant as in panel D. C. aerofaciens was classified as intermediate (see text). Each point represents 1 community in the presence of metronidazole or vancomycin. The Spearman correlation is annotated for all data points (black) and for sensitive communities only (green). The data underlying panels BDEF in this figure can be found in DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7626486. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; subMIC, sub-minimum inhibitory concentration.

In monoculture, C. difficile’s growth was moderately enhanced in the presence of a single subMIC (1.5 μg/mL metronidazole, subMIC fold change of 1.6, S3A Fig). Time-series OD600 measurements of C. difficile monoculture revealed that this moderate growth enhancement was due to a difference in growth phase in the presence and absence of the antibiotic at the measured time point (48 h) (S3C and S3D Fig). By contrast, C. difficile’s growth was enhanced in 2 pairwise communities in the presence of subMICs compared to no treatment over multiple time points that was not due to differences in growth phase (S3E and S3F Fig). Thus, while differences in monoculture growth phases yielded a modest enhancement of C. difficile in response to a single subMIC, a different mechanism determined the observed larger and sustained growth enhancements in pairwise communities.

We hypothesized the action of the antibiotic in certain pairwise communities relieved the biotic inhibition of C. difficile, which would in turn enhanced C. difficile growth, representing competitive release [28,29]. This competitive release would occur in pairwise communities with competitors (i.e., biotic inhibitors) with a higher susceptibility to the antibiotic than C. difficile. By contrast, if a biotic inhibitor displayed a higher resistance to the antibiotic than C. difficile, the degree of biotic inhibition would remain unchanged at subMICs, and thus, C. difficile’s growth would not change substantially compared to its growth in absence of the antibiotic (Fig 3C). Supporting this hypothesis, the maximum subMIC fold change of C. difficile displayed a strong positive correlation with the degree of biotic inhibition in the presence of the coculture partner (Fig 3D). In addition, the correlation was enhanced in pairwise communities containing gut microbes that were sensitive to the antibiotic (Fig 3D). In the presence of both individual antibiotics, the maximum subMIC fold change of C. difficile was significantly higher when paired with biotic inhibitors with higher sensitivity to the antibiotic than C. difficile (S3G Fig). In sum, antibiotic induced inhibition of susceptible biotic inhibitors enhanced C. difficile’s growth in response to subMICs. This suggests that C. difficile’s growth in the gut could be enhanced in the subMIC regime if patients harbor antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitors.

We investigated whether the C. difficile subMIC growth enhancements measured using the OD600-based absolute abundance method were due to increases in C. difficile abundance as opposed to other factors such as changes in cell morphology. To this end, we determined the subMIC fold changes of C. difficile in select pairwise communities that were characterized using CFU counting (S2B and S2C Fig). Our results showed that the CFU method and OD600-based absolute abundance method identified a significant subMIC fold change in the C. difficile-B. thetaiotaomicron and C. difficile-D. piger pairs in presence of metronidazole (S2D Fig). The methods also agreed in detecting no significant subMIC fold changes in 10 other pairwise communities in metronidazole or vancomycin (S2D Fig). However, the CFU method did not detect significant subMIC fold changes in 3 pairwise communities for which the OD600-based method detected significant fold changes (C. difficile-C. hiranonis vancomycin and metronidazole conditions and C. difficile-C. scindens metronidazole condition, S2D Fig). These discrepancies may be due to differences in sensitivities of the 2 methods, as the spot dilution CFU method (Methods) cannot distinguish small fold changes (average variation of technical replicates is 2-fold).

To determine if subMIC fold changes could be resolved using the lower sensitive CFU method, we increased the resolution of subinhibitory concentrations tested. The finer resolution may capture subMICs with larger fold changes that are large enough to be detectable by the CFU method. Additionally, the finer resolution may result in multiple subMICs with significant fold changes, increasing confidence in the results. We used the CFU method with a finer resolution of antibiotic concentrations to measure growth enhancement in the C. difficile-B. vulgatus pairwise community in the presence of metronidazole, which exhibited a significant C. difficile growth enhancement using the OD600-based method (Fig 3B). Our results demonstrated a significant C. difficile subMIC fold change at multiple concentrations in the pairwise community, while no significant fold changes were observed in the C. difficile monoculture (S4 Fig). This demonstrates that the observed C. difficile growth enhancement using the OD600-based method (Fig 3B) was consistent with CFU counting. Overall, our results demonstrate that C. difficile subMIC growth enhancements can also be detected by the CFU-based absolute abundance method.

Enhancement of C. difficile abundance in multispecies communities in the presence of low antibiotic concentrations

We investigated if the OD600-based absolute abundance trends observed in pairwise communities persisted in multispecies communities that are more representative of human gut microbiota. The communities consisted of 2- and 3-member core communities (CC) predicted to display minimal biotic inhibition of C. difficile guided by a previously developed dynamic computational model of our system [4] (CC-2: D. piger and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. CC-3: D. piger, F. prausnitzii, and Eggerthella lenta). In addition to this core community, we introduced at least 1 antibiotic-sensitive inhibitor, antibiotic-resistant inhibitor, or a combination of species in these 2 groups, creating 10 communities for metronidazole and 12 communities for vancomycin (3- to 6-members). To further explore the behavior of communities in response to antibiotic perturbations, we characterized the response of 3-, 4-, 5-, 13-, or 14-member communities (19 total) with no consistent core members to metronidazole.

In 6 of 29 communities characterized in the presence of metronidazole, C. difficile’s MIC was 4-fold greater than in monoculture, increasing from 6 μg/mL to 24 μg/mL. The remaining communities displayed moderate (2-fold, 14 communities) or no change (9 communities) (S5A Fig, S1 Table). In 4 of 12 communities examined in the presence of vancomycin, C. difficile’s growth was strongly inhibited at all concentrations and no MIC could be calculated (S5B Fig, S2 Table, indicated as “NG”). The remaining 8 communities displayed either a moderate increase in MIC (2-fold, 2 communities) or no change (6 communities) (S5B Fig, S2 Table). Consistent with the pairwise community data, C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC was altered in certain communities, but C. difficile’s vancomycin MIC was not substantially altered in any of the characterized communities.

We tested if the multispecies communities containing antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitors displayed an enhancement in C. difficile’s growth at subMICs. In response to metronidazole or vancomycin, C. difficile’s growth was enhanced in response to at least 1 subMIC in most communities (21 of 29 communities for metronidazole, 9 of 12 communities for vancomycin, Figs 3E and S6). Consistent with the pairwise community data, the degree of biotic inhibition of C. difficile was positively correlated with the magnitude of the maximum subMIC fold change (Fig 3F). In addition, the correlation was stronger for communities composed of only antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitors (Fig 3F). Consistent with these trends, the number of sensitive inhibitors in the community and the absolute abundance of sensitive inhibitors displayed a positive correlation with the maximum subMIC fold change (S7A Fig). Communities containing antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitors had a significantly higher average subMIC fold change than communities containing only resistant inhibitors or a mix of both inhibitor types (S7B Fig).

Communities containing a mix of antibiotic sensitive and resistant inhibitors, mirroring the makeup of the gut microbiota, displayed low subMIC fold changes similar in magnitude to resistant biotic inhibitor communities (S7B Fig). In communities with a non-zero abundance of resistant biotic inhibitors, the correlation between the growth enhancement of C. difficile and the number of sensitive inhibitors or abundance of sensitive inhibitors vanished (S7A Fig). These data suggest that resistant biotic inhibitors can suppress the C. difficile growth enhancement caused by sensitive biotic inhibitors. We analyzed if the growth enhancement of C. difficile in multispecies communities could be predicted based on the sum of the growth enhancements of C. difficile in pairwise communities. While the relationship displayed a moderate correlation, it was not additive (S7C and S7D Fig). This demonstrates that community effects, such as interspecies interactions between constituent community members and growth enhancement suppression by resistant inhibitors, play key roles in determining the magnitude of growth enhancement of C. difficile at subMICs. Overall, these results demonstrate that C. difficile growth enhancement at subMICs can occur in multispecies communities, suggesting this response may occur in the human gut microbiome.

A dynamic ecological model representing pairwise interactions and monospecies antibiotic susceptibilities can capture the response of C. difficile to subMICs

We hypothesized that a model capturing the dynamics of species growth, interspecies interactions, and monospecies antibiotic susceptibilities could recapitulate the observed trends in C. difficile growth enhancement at subMICs. We assumed that inferred interspecies interactions in the absence of antibiotics contributed to the community response to antibiotics. We tested whether a model that neglects complex antibiotic-dependent interspecies interactions could predict the qualitative trends of C. difficile growth at subMICs.

The gLV model is a system of coupled ordinary differential equations that captures individual species’ growth rate and pairwise interactions with each community member. We use an expansion of the generalized Lotka–Volterra model (gLV) that captures antibiotic perturbations [30] (Fig 4A). In this expanded model, the growth of each species is modified by an antibiotic term consisting of the concentration of antibiotic and the susceptibility of each species (Bi) (Methods, Fig 4A).

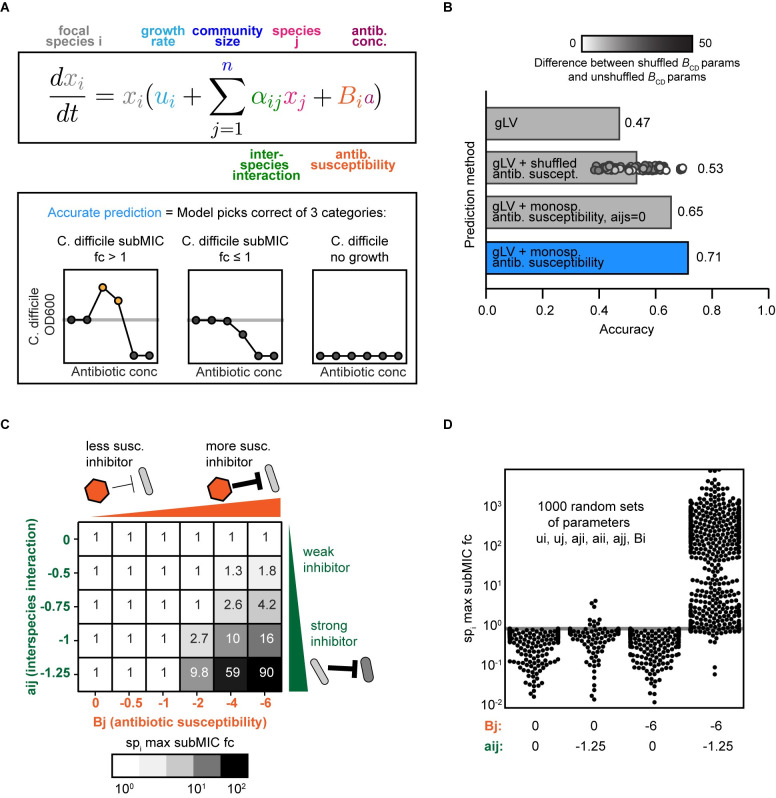

Fig 4. A modified generalized Lotka–Volterra model of community dynamics in response to antibiotics captures trends in antibiotic concentrations lower than the MIC in the presence of antibiotic sensitive biotic inhibitors.

(A) Top: Schematic of the antibiotic expansion of the gLV model. Bottom: Schematic of accuracy metric used in panel B. (B) Qualitative accuracy of multiple models for pairwise and multispecies communities. Models include (1) standard gLV model lacking an antibiotic term; (2) gLV model with randomly shuffled antibiotic susceptibility parameters (average of 100 permutations), and 100 shuffled values shown as points, shaded according to the absolute value of the difference between the shuffled C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility parameter and the original C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility parameter; (3) gLV model with antibiotic susceptibility terms inferred from monospecies with all interaction parameters set to zero (aij = 0, where i! = j); (4) full gLV model with antibiotic susceptibility terms inferred from monospecies data. (C) Simulated maximum subMIC fold changes for a focal species in a pairwise community for 48 h for a representative parameter set. Growth rates of the 2 species are equal (ui = uj = 0.25), intraspecies interactions are equal (aii = ajj = −0.8), and initial ODs are equal (xi(0) = xj(0) = 0.0022). The interspecies interaction coefficients aji are set to 0 and Bi is set to −2. (D) Simulated max subMIC fold change for a focal species in a pairwise community for 1,000 randomly sampled parameter sets. Parameters Bj and aij are set to constant values of 0 or −6 and 0 or −1.25, respectively. Other parameters were randomly sampled between upper and lower bounds. The lower and upper bounds on each parameter value are aji (−1.25, 1.25), growth rates (0, 1), intraspecies interactions (−1.25, 0), Bi (−6, 0). Gray horizontal line at y = 1 indicates no change in growth compared to the no antibiotic condition. The data and modeling scripts underlying panels BCD in this figure can be found in DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7726490. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; subMIC, sub-minimum inhibitory concentration.

The monospecies antibiotic susceptibility parameters were inferred from measurements of individual species growth in the presence of a range of antibiotic concentrations (2-fold dilutions) (Methods, S1 Fig). We used growth rate and interspecies interaction parameters that were previously inferred based on absolute abundance measurements of 159 monospecies and communities (2- to 14-member) in the absence of antibiotics [4].

We evaluated whether this model could qualitatively predict the trends in growth enhancement of C. difficile in the subMIC range (S8 and S9 Figs). C. difficile’s response to each antibiotic concentration was classified into 3 categories (C. difficile subMIC fold-change > 1, C. difficile subMIC fold-change ≤ 1, or no growth of C. difficile, Fig 4A). The expanded gLV model correctly predicts C. difficile’s qualitative response to 71% of antibiotic conditions (Figs 4B and S10A). We designed a set of null models to evaluate the contribution of different terms of the expanded gLV model to model performance. The full model displays higher accuracy than a null model that lacked antibiotic susceptibility terms or has randomly shuffled antibiotic susceptibility parameters (47% and 53% accuracy, Fig 4C). These data highlight that the fitted monospecies susceptibilities play a major role in the model’s predictive performance. The full model also outperforms a null model that lacks interspecies interaction terms (65%, Fig 4C), indicating that the inferred interspecies interactions contribute to the growth enhancement of C. difficile in response to subMICs. Taken together, these findings indicate that biotic inhibition and monospecies antibiotic susceptibility are major variables determining the growth of C. difficile in response to subMICs in microbial communities.

We explored model simulations to determine if the enhancement of C. difficile growth at subMICs required a sensitive biotic inhibitor in a wide variety of communities, beyond those that were experimentally characterized. To this end, we simulated 1,000 pairwise communities with a wide range of growth rates, interspecies interactions, and antibiotic susceptibilities. When paired with a sensitive biotic inhibitor, growth is enhanced at subMICs, consistent with the trends observed in our experiments (Fig 4D). By contrast, growth enhancements are not observed in simulated communities that lack an antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibitor of the focal species (Fig 4D). This trend is also present in larger communities (S10B Fig). The focal species’ growth enhancement at subMICs increases with biotic inhibition and antibiotic susceptibility of the inhibitor species (Fig 4E). Overall, these model simulations suggest that the antibiotic sensitive inhibitor trend we observe with C. difficile in human gut communities is generalizable to other species and communities with variable richness, interaction networks, and antibiotic susceptibilities.

D. piger substantially increases C. difficile’s minimum inhibitory concentration to metronidazole

Changes in antibiotic susceptibility of a pathogen due to significant microbial interactions could reduce the efficacy of antibiotic treatments. In the presence of D. piger, we observed a substantial increase in C. difficile MIC, in addition to a moderate growth enhancement of C. difficile at subMICs (Fig 2B). Consistent with the proposed antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibition mechanism, D. piger was a weak biotic inhibitor of C. difficile and was more sensitive to metronidazole than C. difficile (Figs 2A and 3C). However, the substantial increase in C. difficile MIC in the presence versus absence of D. piger (≥24 μg/mL compared to 6 μg/mL) was not explained by the proposed antibiotic-sensitive biotic inhibition mechanism and the expanded gLV antibiotic model failed to predict this trend (S8A Fig). While competitive interactions (i.e., resource competition or biological warfare) contributed to the observed subMIC growth response, the mechanism of increased metronidazole MIC in the presence of D. piger was unknown.

We investigated the robustness of this trend across different environmental conditions and for different C. difficile isolates. C. difficile displayed an increased MIC in coculture with D. piger and in monoculture in D. piger’s spent media (≥8-fold increase in MIC) (Fig 5A). These data indicate that the increase in C. difficile metronidazole MIC was not dependent on cell-to-cell contact with D. piger or prior exposure of D. piger to metronidazole. C. difficile displayed a higher metronidazole MIC in D. piger spent media harvested at late exponential phase/early stationary phase than in spent media harvested at earlier time points in exponential phase (S11A and S11B Fig). Further, multiple C. difficile clinical isolates had an increased MIC in D. piger spent media (S11C Fig). Finally, C. difficile exhibited a higher metronidazole MIC in coculture with D. piger in a different chemically defined growth medium (S11D Fig). These data demonstrate that the protective effect of D. piger on C. difficile’s response to metronidazole was robust to variations in C. difficile’s strain background, media composition, and the growth phase of D. piger.

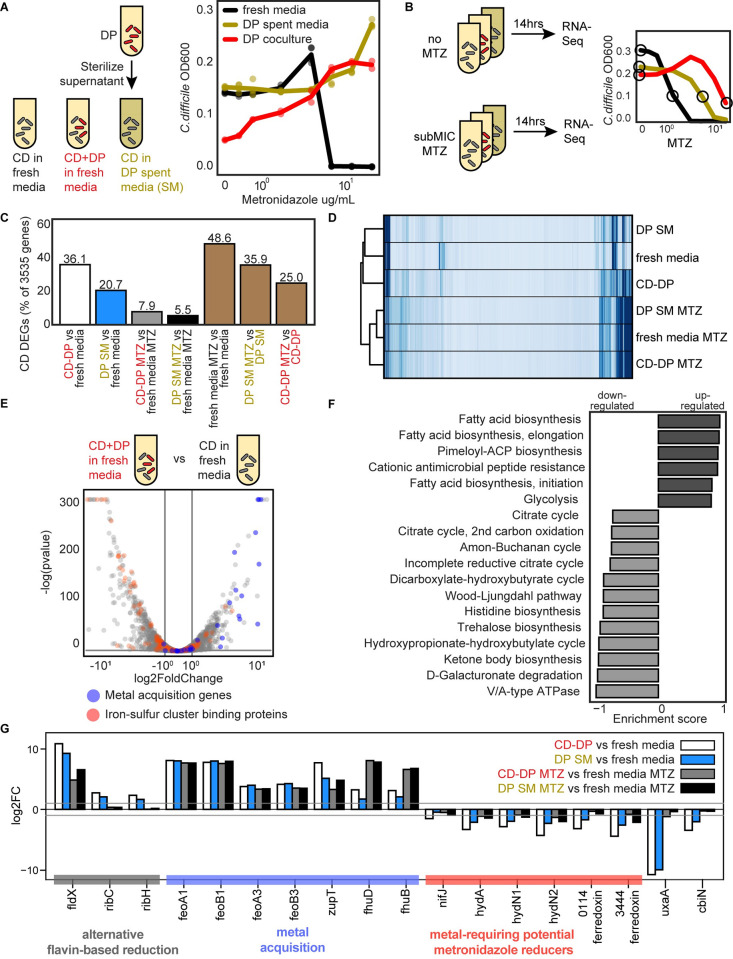

Fig 5. D. piger increases the metronidazole MIC of C. difficile and induces metal starvation genome-wide transcriptional response.

(A) Abundance of C. difficile at 41 h in response to different metronidazole concentrations. The OD600 value for C. difficile in the presence of D. piger is calculated OD600 (OD600 multiplied by relative abundance from 16S rRNA gene sequencing). The x-axis is semi-log scale. Data points represent biological replicates. Lines indicate average of n = 2 to n = 4 biological replicates. (B) Schematic of genome-wide transcriptional profiling experiment. The x-axis is semi-log scale of metronidazole (MTZ) concentration. Lines indicate average C. difficile OD600 at 14 h for n = 4 biological replicates. Circles indicate conditions sampled for RNA-Seq. (C) C. difficile DEGs between culture conditions. DEGs are defined as genes that displayed greater than 2-fold change and a p-value less than 0.05. (D) Clustered heatmap of RPKM for each gene (rows) and in each sample (columns) for C. difficile. Each column represents the average of n = 2 biological replicates. Hierarchical clustering was performed based on Euclidean distance using the single linkage method of the Python SciPy clustering package. (E) Volcano plot of log transformed transcriptional fold changes for C. difficile in the presence of D. piger. Gray vertical lines indicate 2-fold change and the gray horizontal line indicates the statistical significance threshold (p = 0.05). Blue indicates genes annotated to be involved in metal import. Red indicates genes predicted to contain iron-sulfur clusters by MetalPredator [31]. (F) Enriched gene sets in C. difficile grown in the presence of D. piger compared to C. difficile grown in fresh media. All gene sets with significant enrichment scores from GSEA are shown. Gene sets are defined using modules from the KEGG. (G) Bar plot of the log transformed fold changes of a set of genes across different conditions. Gray horizontal lines indicate 2-fold change. The data underlying panels AB in this figure can be found in DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7626486 and the data underlying panels CDEFG in this figure can be found in DOI 10.5281/zenodo.7049035 and 10.5281/zenodo.7049027 and S3 and S4 Tables. DEG, differentially expressed gene; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; RPKM, reads per kilobase million.

D. piger could alter C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC via a direct chemical interaction with metronidazole which reduces its efficacy (e.g., degradation or sequestration) or an indirect effect that modifies the activities of C. difficile’s intracellular networks which in turn yields an increase in metronidazole MIC. To test for a direct chemical interaction, we incubated metronidazole in either D. piger spent media or fresh media and characterized C. difficile’s growth response to each of these conditions in fresh media. C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC was equal in these conditions, indicating that compounds present in D. piger’s spent media do not directly interact with metronidazole to reduce its activity (S11E Fig).

C. difficile displays a genome-wide transcriptional signature of metal limitation in response to D. piger

We considered indirect effects of D. piger on C. difficile’s intracellular network activities which in turn could alter C. difficile’s response to metronidazole. We first considered resource competition as a possible indirect effect because resource competition is a common mechanism driving interspecies interactions in microbial communities. C. difficile’s abundance was not substantially lower in D. piger’s spent media than monoculture (Fig 5A), suggesting that resource competition was not a major driver of the increased MIC. In addition, supplementing concentrated fresh media into the D. piger spent media, which would alleviate any resource competition, did not alter C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC (S11F Fig). Therefore, these data suggest that D. piger did not affect the metronidazole MIC of C. difficile via resource competition.

We considered if D. piger affected the metronidazole MIC of C. difficile by altering patterns in gene expression. We performed genome-wide transcriptomic profiling of C. difficile in late exponential phase in the following environments: (1) monoculture in fresh media; (2) monoculture in D. piger spent media; and (3) coculture with D. piger. Each of these cultures was exposed to a subMIC of metronidazole that reduced growth by approximately 50% or no treatment was applied (Fig 5B). The antibiotic concentration was chosen to allow sufficient growth for transcriptional profiling.

C. difficile’s gene expression profile in D. piger conditions (i.e., D. piger spent media and coculture with D. piger) was significantly altered compared to C. difficile monoculture (Tables 1 and S3). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as genes with >2-fold change and a p-value less than 0.05. In the absence of antibiotics, 36% and 21% of C. difficile’s 3,535 genes were differentially expressed in the D. piger coculture and spent media, respectively, compared to the C. difficile monoculture in fresh media (Fig 5C, white and blue bars). Of these genes, 72 in the D. piger coculture and 47 in the D. piger spent media exhibited >8-fold change, demonstrating that the presence of D. piger had a large impact on C. difficile’s gene expression profile. In the presence of metronidazole, a smaller percentage of genes were differentially expressed between the D. piger and fresh media conditions (8% and 6%, Fig 5C, gray and black bars). Large shifts in C. difficile gene expression occurred due to the addition of metronidazole, with 25% to 49% of genes differentially expressed (Fig 5C, brown bars). The 3 metronidazole conditions clustered closely together, indicating that the antibiotic induced similar changes in gene expression regardless of the media condition or ecological context (Fig 5D).

Table 1. C. difficile gene expression in D. piger conditions compared to fresh media for genes with >16-fold differential expression.

| D. piger coculture vs. fresh media | D. piger spent media vs. fresh media | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus_tag | Gene name | log2 FC | padj | log2 FC | padj | |

| CDR20291_1925 | fldX | flavodoxin | 10.86 | 0.0E+00 | 9.27 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_2391 | none | hypothetical protein | 9.54 | 0.0E+00 | 8.57 | 9.0E-197 |

| CDR20291_0517 | none | putative membrane protein | 8.73 | 0.0E+00 | 8.87 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_0516 | none | putative cation transporting ATPase | 8.10 | 0.0E+00 | 8.36 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_1327 | feoA1 | putative ferrous iron transport protein A | 8.09 | 9.0E-167 | 8.03 | 3.0E-140 |

| CDR20291_1328 | feoB1 | ferrous iron transport protein B | 7.79 | 0.0E+00 | 8.00 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_0946 | zupT | zinc transporter | 7.71 | 1.0E-51 | 5.14 | 3.0E-20 |

| CDR20291_1329 | none | putative exported protein | 7.60 | 1.0E-105 | 7.49 | 1.0E-81 |

| CDR20291_1326 | none | putative ferrous iron transport protein | 7.12 | 2.0E-227 | 6.96 | 2.0E-157 |

| CDR20291_2009 | none | putative Na(+)/H(+) antiporter | 5.46 | 5.7E-221 | 3.93 | 1.0E-87 |

| CDR20291_2825 | none | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 5.30 | 1.6E-136 | 3.81 | 5.0E-51 |

| CDR20291_2826 | none | putative ABC transporter, permease protein | 5.14 | 3.4E-130 | 3.58 | 4.0E-45 |

| CDR20291_2827 | none | hypothetical protein | 4.91 | 7.4E-126 | 3.52 | 1.0E-44 |

| CDR20291_0455 | none | putative membrane protein | 4.84 | 2.0E-54 | 1.94 | 5.0E-06 |

| CDR20291_1545 | none | putative iron compound ABC transporter, permease protein | 4.66 | 9.0E-106 | 3.59 | 3.0E-46 |

| CDR20291_1546 | none | putative iron compound ABC transporter, permease protein | 4.52 | 5.0E-61 | 3.40 | 4.0E-28 |

| CDR20291_1547 | none | putative iron compound ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 4.46 | 4.0E-67 | 3.03 | 2.0E-23 |

| CDR20291_0687 | plfB | formate acetyltransferase | 4.38 | 5.0E-203 | 2.51 | 5.0E-46 |

| CDR20291_1021 | acpP | acyl carrier protein | 4.30 | 9.0E-101 | 2.00 | 9.0E-16 |

| CDR20291_1548 | none | putative iron compound ABC transporter, substrate-binding protein | 4.23 | 8.0E-117 | 2.77 | 3.0E-28 |

| CDR20291_2437 | none | putative sugar transporter, substrate-binding lipoprotein | 4.20 | 1.1E-165 | 2.16 | 3.0E-28 |

| CDR20291_3135 | feoB3 | putative ferrous iron transport protein B | 4.14 | 1.9E-189 | 4.26 | 2.0E-148 |

| CDR20291_2824 | none | ABC transporter, substrate-binding protein | 4.11 | 9.9E-129 | 2.83 | 4.0E-40 |

| CDR20291_1022 | fabF | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase II | 4.00 | 1.0E-121 | 1.58 | 2.0E-16 |

| CDR20291_0363 | none | Radical SAM-superfamily protein | −4.00 | 2.0E-134 | −3.26 | 9.0E-71 |

| CDR20291_0368 | hadB | subunit of oxygen-sensitive 2-hydroxyisocaproyl-CoA dehydratase | −4.01 | 3.0E-183 | −1.72 | 5.0E-25 |

| CDR20291_2064 | gabT | 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase | −4.04 | 3.0E-89 | −3.07 | 4.0E-41 |

| CDR20291_0364 | none | putative membrane protein | −4.09 | 6.0E-164 | −3.50 | 2.0E-78 |

| CDR20291_3178 | fdhD | formate dehydrogenase accessory protein | −4.09 | 8.0E-127 | −2.45 | 4.0E-37 |

| CDR20291_0523 | cotJC1 | putative spore-coat protein | −4.11 | 5.0E-107 | −1.18 | 2.0E-09 |

| CDR20291_0755 | rbr | rubrerythrin | −4.11 | 2.0E-155 | −2.40 | 2.0E-29 |

| CDR20291_2227 | abfH | NAD-dependent 4-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase | −4.12 | 3.9E-181 | −2.00 | 4.0E-30 |

| CDR20291_2509 | none | putative membrane protein | −4.14 | 1.8E-164 | −0.67 | 2.0E-04 |

| CDR20291_0731 | crt1 | 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (crotonase) | −4.20 | 1.0E-08 | −2.81 | 1.0E-05 |

| CDR20291_2794 | ntpI | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit I | −4.27 | 3.2E-174 | −1.79 | 8.0E-27 |

| CDR20291_0177 | none | putative oxidoreductase, NAD/FAD binding subunit | −4.29 | 1.0E-147 | −3.29 | 2.0E-66 |

| CDR20291_1478 | none | hypothetical protein | −4.30 | 8.0E-122 | −2.80 | 2.0E-39 |

| CDR20291_3176 | hydN2 | electron transport protein | −4.31 | 2.7E-160 | −2.32 | 4.0E-41 |

| CDR20291_2566 | ctfB | butyrate—acetoacetate CoA-transferase subunit B | −4.32 | 5.2E-11 | −2.31 | 2.0E-05 |

| CDR20291_0011 | none | putative translation elongation factor | −4.33 | 2.0E-135 | −1.72 | 1.0E-16 |

| CDR20291_1511 | none | hypothetical protein | −4.33 | 5.0E-128 | −1.88 | 7.0E-22 |

| CDR20291_0175 | none | putative oxidoreductase, acetyl-CoA synthase subunit | −4.39 | 2.0E-183 | −3.02 | 1.0E-59 |

| CDR20291_2416 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −4.41 | 5.7E-102 | −3.53 | 5.0E-59 |

| CDR20291_2787 | ntpD | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit D | −4.41 | 3.9E-158 | −2.18 | 1.0E-31 |

| CDR20291_2228 | abfT | 4-hydroxybutyrate CoA transferase | −4.41 | 5.6E-189 | −2.08 | 1.0E-32 |

| CDR20291_0176 | none | putative oxidoreductase, electron transfer subunit | −4.42 | 1.0E-181 | −3.37 | 6.0E-61 |

| CDR20291_3444 | none | ferredoxin | −4.45 | 7.0E-182 | −2.61 | 4.0E-25 |

| CDR20291_2132 | asrA | anaerobic sulfite reductase subunit A | −4.51 | 1.7E-10 | −2.81 | 3.0E-06 |

| CDR20291_1905 | none | putative transcriptional regulator | −4.51 | 4.1E-52 | −1.29 | 3.0E-07 |

| CDR20291_2788 | ntpB | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit B | −4.56 | 5.8E-199 | −1.91 | 1.0E-26 |

| CDR20291_2800 | adhE | aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase | −4.69 | 9.4E-15 | −3.76 | 1.0E-09 |

| CDR20291_0521 | none | hypothetical protein | −4.71 | 6.0E-93 | −1.15 | 5.0E-07 |

| CDR20291_3177 | none | hypothetical protein | −4.71 | 5.1E-59 | −2.74 | 2.0E-25 |

| CDR20291_2492 | none | adp-ribosyltransferase binding component | −4.75 | 3.0E-208 | −1.78 | 2.0E-20 |

| CDR20291_2789 | ntpA | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit A | −4.75 | 1.4E-213 | −2.15 | 3.0E-36 |

| CDR20291_2491 | none | cdta (adp-ribosyltransferase enzymatic component) | −4.79 | 9.4E-219 | −1.66 | 5.0E-20 |

| CDR20291_2792 | ntpE | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit E | −4.80 | 6.0E-145 | −1.81 | 7.0E-23 |

| CDR20291_1008 | etfB3 | electron transfer flavoprotein beta-subunit | −4.81 | 2.0E-92 | −4.13 | 5.0E-60 |

| CDR20291_0522 | cotJB1 | putative spore-coat protein | −4.83 | 4.0E-107 | −1.38 | 3.0E-09 |

| CDR20291_0728 | none | putative hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase | −4.83 | 7.0E-14 | −3.85 | 2.0E-10 |

| CDR20291_2793 | ntpK | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit K | −4.91 | 1.2E-184 | −1.78 | 4.0E-24 |

| CDR20291_2790 | ntpG | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit G | −4.93 | 8.4E-144 | −1.92 | 2.0E-21 |

| CDR20291_2230 | abfD | gamma-aminobutyrate metabolism dehydratase/isomerase | −4.96 | 4.5E-250 | −2.15 | 4.0E-33 |

| CDR20291_0709 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −4.99 | 2.0E-251 | −3.38 | 1.0E-65 |

| CDR20291_1007 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −5.03 | 2.0E-118 | −4.47 | 1.0E-69 |

| CDR20291_2229 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −5.09 | 9.9E-189 | −2.74 | 3.0E-27 |

| CDR20291_2791 | ntpC | V-type sodium ATP synthase subunit C | −5.10 | 2.4E-183 | −2.03 | 2.0E-27 |

| CDR20291_0706 | none | putative membrane protein | −5.20 | 9.0E-267 | −3.43 | 4.0E-68 |

| CDR20291_0191 | none | putative membrane protein | −5.26 | 3.0E-254 | −4.21 | 4.0E-127 |

| CDR20291_0708 | none | putative amidohydrolase | −5.32 | 2.0E-226 | −3.72 | 2.0E-63 |

| CDR20291_0707 | none | putative membrane protein | −5.64 | 1.0E-286 | −3.77 | 3.0E-87 |

| CDR20291_0760 | none | putative membrane protein | −5.72 | 3.0E-291 | −4.08 | 2.0E-113 |

| CDR20291_3092 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −6.15 | 0.0E+00 | −4.44 | 4.0E-77 |

| CDR20291_1689 | none | hypothetical protein | −6.48 | 1.0E-39 | −4.14 | 6.0E-31 |

| CDR20291_2074 | hcp | hydroxylamine reductase | −6.92 | 0.0E+00 | −0.87 | 7.0E-06 |

| CDR20291_2417 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −7.27 | 0.0E+00 | −7.54 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_1690 | none | conserved hypothetical protein | −7.84 | 2.0E-158 | −3.50 | 5.0E-68 |

| CDR20291_2075 | none | iron-sulfur binding protein | −8.29 | 0.0E+00 | −1.62 | 7.0E-14 |

| CDR20291_2419 | none | putative aminotransferase | −9.21 | 0.0E+00 | −8.46 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_2418 | none | putative membrane protein | −9.43 | 0.0E+00 | −8.94 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_2766 | kdgT | 2-keto-3-deoxygluconate permease | −10.13 | 0.0E+00 | −9.66 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_2768 | uxaA | putative altronate hydrolase | −10.81 | 0.0E+00 | −10.01 | 0.0E+00 |

| CDR20291_1692 | none | putative pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase | −11.08 | 0.0E+00 | −2.96 | 9.0E-67 |

| CDR20291_2767 | uxaA’ | altronate hydrolase (N-terminus) | −11.44 | 3.4E-41 | −15.26 | 3.0E-21 |

| CDR20291_1691 | none | putative nitrite and sulfite reductase subunit | −12.01 | 0.0E+00 | −3.97 | 9.0E-67 |

To provide deeper insights into specific genes that varied across conditions, we analyzed the genes with the largest expression changes in D. piger conditions. Many of the genes up-regulated in D. piger and D. piger antibiotic conditions compared to fresh media had annotated roles in metal acquisition (blue points in Figs 5E and S12). To acquire iron, C. difficile uses iron permeases to import free ferrous iron into the cell [32,33]. We observed >10-fold up-regulation in 2 ferrous transporters (feoAB1, feoAB3) in D. piger and D. piger metronidazole conditions (Table 1, Fig 5G). Alternative transporters were also up-regulated, such as uptake genes for ferrichrome siderophores (fhuB, fhuD) and catecholate siderophores (CDR20291_1545–1548, orthologs of yclNOPQ in CD630) as well as a zinc transporter gene (zupT). These genes (feo, fhu, ycl, and zupT) are regulated by the iron regulator fur [32] and have been shown to be up-regulated in response to iron starvation and zinc starvation [34–36], suggesting that metal limitation in D. piger conditions was responsible for the observed changes. Consistent with the metal limitation signature, ferrous transporters that were not up-regulated (feoAB2) have been documented as unresponsive to iron limitation [32,34].

In addition to genes directly related to metal transport, many of the DEGs in C. difficile were linked to iron metabolism. Flavodoxin (fldX) was the most up-regulated gene in the D. piger conditions (Table 1, Fig 5G). Flavodoxin can replace iron-requiring electron transfer proteins (such as ferredoxin) in iron-limiting conditions [37]. Flavodoxin uses a nonmetal cofactor, flavin, whose biosynthesis genes (ribACH) were up-regulated in D. piger conditions (Table 1). Previous studies have shown that flavodoxin was regulated by fur and de-repressed in iron-limiting and zinc-limiting conditions [32,34–36], and riboflavin biosynthesis genes were up-regulated in iron-limiting conditions [35]. Iron-containing proteins have been shown to be down-regulated in iron-limited conditions [35]. Using a bioinformatic analysis, we found that 9% of C. difficile’s down-regulated genes (62 of 678 genes) in the D. piger coculture condition were predicted to contain iron-sulfur clusters (red points in Fig 5E, S4 Table). In sum, genes for the metal-independent flavodoxin were up-regulated, whereas transcripts for iron-requiring proteins were down-regulated, consistent with a metal-limited environment for C. difficile created by D. piger.

To identify other biological pathways that were significantly altered in D. piger conditions, we performed a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) modules (Figs 5F and S12). Many of the identified pathways could be connected to metals. For example, many of the enzymes in the down-regulated Wood–Ljungdahl pathway have iron-sulfur clusters, namely carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (cooCS, CDR20291_0653, CDR20291_0655) and formate dehydrogenase H (fdhF) [38–40]. In addition, the [NiFe] hydrogenase (hydAN1N2) in the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway contains a nickel-iron cluster. These enzymes have been shown to be down-regulated under iron-limited conditions [35]. Pathways for cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance and fatty acid biosynthesis were up-regulated, which has been previously attributed to iron limitation [35]. Similarly, the down-regulation of pathways for V-type ATPases, D-galacturonate degradation, and trehalose biosynthesis has been connected to iron limitation (Fig 5F) [35]. D. piger also affected the expression of C. difficile toxins (tcdA, tcdB, and binary toxin genes CDR20291_2491 and CDR20291_2492) that were down-regulated between 4- and 27-fold in the D. piger conditions (S3 Table).

To provide further insights into the contribution of iron limitation on the patterns of gene expression in C. difficile, we evaluated the relationship between gene expression changes in C. difficile in the presence of D. piger and gene expression changes in C. difficile in iron-limited media previously characterized in a separate study [35]. For all DEGs, we compared the log2 fold changes between C. difficile in the D. piger coculture and C. difficile in monoculture in the absence of metronidazole with the log2 fold changes observed between C. difficile in iron-limited and iron-rich media in the previous study. These fold changes displayed an informative relationship and were qualitatively consistent for 89% of genes between the 2 studies (S13A Fig, Pearson r = 0.61, p = 8*10−54). Similarly, the fold changes of C. difficile cultured in D. piger spent media showed 87% qualitative agreement with the fold changes in the C. difficile iron-limitation study (S13B Fig). The informative relationship between these datasets suggests that the shifts in gene expression for the majority of C. difficile’s genes in the D. piger conditions can be explained by metal limitation.

Overall, these data suggest that D. piger created a metal-limited environment for C. difficile, as metal acquisition and alternative genes involved in flavin metabolism were up-regulated, whereas transcripts for metal-requiring proteins were down-regulated (Fig 5G). These trends were observed in both D. piger coculture and D. piger spent media and were also consistent with the trends in the D. piger conditions with metronidazole (Fig 5G).

Differentially expressed genes in C. difficile in the presence of D. piger are linked to metronidazole resistance

Since the majority of C. difficile’s DEGs could be explained by metal limitation, we investigated the connection between metal limitation and C. difficile metronidazole MIC. To identify potential connections, we compared the set of DEGs in the presence of D. piger to genes previously shown to play a role in metronidazole resistance in C. difficile.

In 2 studies of metronidazole-resistant C. difficile mutants, iron-related genes were implicated in metronidazole resistance. In a study of C. difficile strain ATCC 700057, multiple mutants with increased metronidazole resistance acquired a truncation in feoB1, which resulted in reduced intracellular iron and a shift to flavodoxin [41]. Similarly, in a metronidazole-resistant mutant of a NAP1 strain, iron-uptake genes were down-regulated and a shift to flavodoxin was observed [42]. In each of these studies, the proposed mechanism of metronidazole resistance was attributed to down-regulation of enzymes predicted to reduce metronidazole to its active form. In the D. piger conditions, enzymes hypothesized to reduce metronidazole were also down-regulated, namely ferredoxin genes (fdxA, CDR20291_0114, CDR20291_3444), pyruvate-ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR) (nifJ), and hydrogenases (hydA, hydN1, hydN2) (Table 1, Fig 5G) [20,21]. Down-regulation of these enzymes in D. piger conditions may reduce the rate of conversion of metronidazole into its active form, thus increasing the tolerance of C. difficile. The down-regulated enzymes are each predicted to contain iron clusters (S4 Table), and hydrogenases are known to contain nickel cofactors [39], suggesting that their down-regulation and the subsequent decrease in metronidazole susceptibility could be attributed to metal limitation.

This mechanism of resistance has been proposed in other species beyond C. difficile. For example, Bacteroides fragilis metronidazole-resistant mutants displayed reduced PFOR expression [21]. Therefore, if this mechanism was responsible for the increase in C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC by D. piger, Bacteroides species should also display a higher MIC. Indeed, B. thetaiotaomicron displayed a higher metronidazole MIC in D. piger spent media compared to fresh media (S14 Fig).

We also identified that cbiN, a putative cobalt transporter that was down-regulated in the D. piger conditions (Table 1, Fig 5G) and in iron-limited media [35] has been previously implicated in metronidazole resistance. A single SNP present in cbiN distinguished a metronidazole-resistant R010 isolate of C. difficile from a metronidazole sensitive R010 isolate isolated from the same patient [43]. In our data, cbiN was down-regulated by 10-fold in the D. piger coculture and 4-fold in D. piger spent media.

Another enzyme that was down-regulated in the D. piger conditions, altronate hydrolase (uxaA), has potential connections with metronidazole resistance. Notably, altronate hydrolase was substantially down-regulated in the coculture with D. piger, where the magnitude of this decrease in transcript abundance was the second largest in the transcriptome (>1,000-fold reduction, Table 1, Fig 5G). Altronate hydrolase catalyzes the dehydration of the six-carbon altronate as part of galacturonate degradation [44]. One of the 17 mutations that distinguished a metronidazole-resistant NAP1 C. difficile strain from the metronidazole sensitive C. difficile reference strain occurred in the altronate hydrolase gene. The mutation in altronate hydrolase was one of 3 frameshift mutations in the mutant and likely rendered altronate hydrolase nonfunctional [45]. Studies in E. coli have demonstrated that this enzyme requires iron or manganese for its catalytic activity [46], consistent with its strong down-regulation in metal-limited media [35].

The mutations in cbiN and uxaA in metronidazole-resistant C. difficile isolates suggests that the observed down-regulation of cbiN and uxaA in response to metal limitation may contribute to C. difficile’s increased metronidazole MIC. These genes are potential links between metal limitation and metronidazole susceptibility, in addition to the down-regulation of metal-containing oxidoreductases, hydrogenases, and ferredoxins predicted to convert metronidazole into its active form.

Hydrogen sulfide production by D. piger promotes metal sequestration

The global changes in C. difficile’s gene expression profile suggest that D. piger created a metal-limited environment. We hypothesized that these metal limitations could have been caused by hydrogen sulfide produced by D. piger [47]. In D. piger cultures, we observed a characteristic black precipitate (ferrous sulfide) that forms when iron combines with produced hydrogen sulfide [48]. Other divalent metals can precipitate with sulfide as well [49,50] and may be precipitating in addition to ferrous sulfide in the presence of D. piger.

To estimate how much metal is precipitated by D. piger produced sulfide, we quantified the amount of sulfide in a monoculture of D. piger over time (Methods). The amount of sulfide peaked in late exponential phase at 1.4 mM (Fig 6A). Hydrogen sulfide is volatile and escapes during growth. Therefore, the total amount of produced hydrogen sulfide was likely higher than the measured concentration. While C. difficile also produces a small amount of hydrogen sulfide, the amount of hydrogen sulfide in the C. difficile and D. piger coculture was similar to the amount in the D. piger monoculture (S15A Fig). The produced hydrogen sulfide in the D. piger spent media and D. piger coculture (>1.4 mM) was in excess of the total divalent metal concentration in the media (1.2 mM iron and micromolar concentrations of other metals, S15B Fig). Therefore, the produced hydrogen sulfide could precipitate all divalent metals in the media, creating a metal-limited environment for C. difficile. This would explain the metal-limited signature in C. difficile’s gene expression profile. Supporting this hypothesis, iron depletion due to the precipitation with excess sulfide has been previously shown to induce Fur-regulated genes in C. difficile [51].

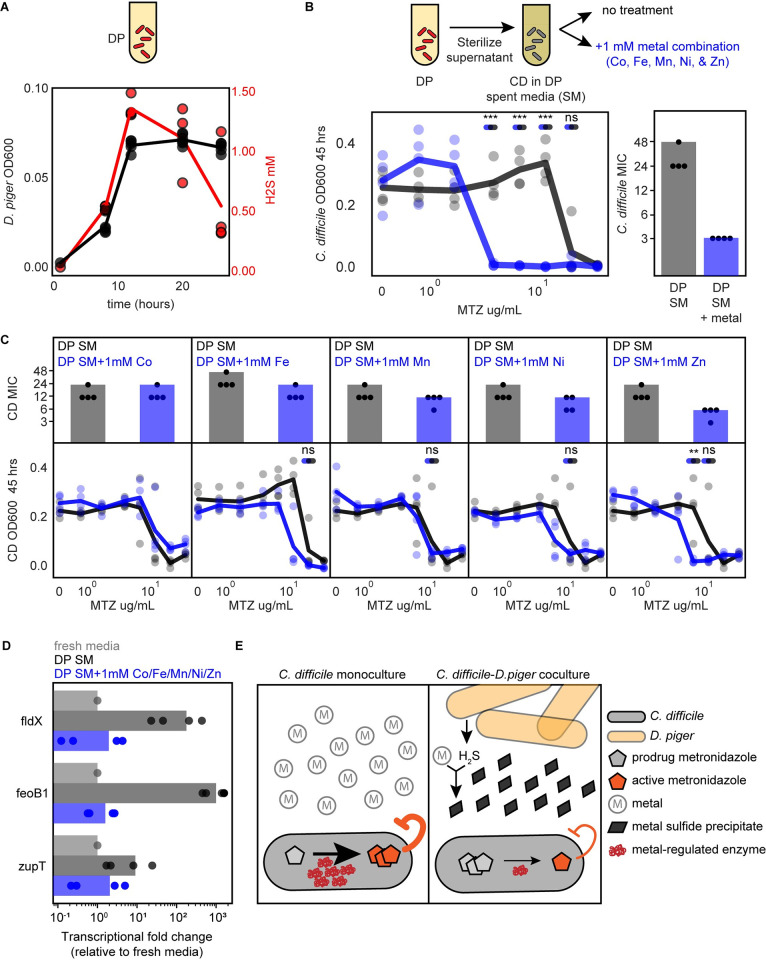

Fig 6. Supplementation of D. piger spent media with metals eliminates the protective effect on C. difficile in the presence of metronidazole.

(A) Line plot of absolute abundance (black) and hydrogen sulfide production (red) of D. piger in monoculture. Data points represent biological replicates. Each biological replicate is the average of 2 technical replicates. Line indicates average of n = 4 biological replicates. (B) Line plot and bar plot of C. difficile metronidazole (MTZ) susceptibility in D. piger spent media (SM) with and without metal supplementation at 48 h. Metal supplementation condition contained 1 mM of Co, Mn, Ni, Zn, and Fe. The x-axis is semi-log scale (line plot). Data points represent biological replicates. Lines indicate average of n = 4 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference between conditions with and without metal supplementation (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) according to an unpaired t test, “ns” indicates not significant. Statistical significance was performed at the lower of the 2 MICs and concentrations between the MICs of the 2 conditions. Bar plot displays MIC of data shown in line plot. Data points represent the MIC of n = 4 biological replicates. Bar represents the MIC determined based on average OD600 of n = 4 biological replicates. (C) Line plots and bar plots of C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility in D. piger spent media (SM) with and without supplementation of individual metals at 48 h. Each x-axis is semi-log scale. Data points represent biological replicates. Lines indicate the average of n = 4 biological replicates. Bar plot displays MIC of data shown in line plot. Data points represent MIC of n = 4 biological replicates. Bar represents the MIC determined based on an average OD600 of n = 4 biological replicates. Statistical significance as described in panel B. For metals with a change in MIC between the 2 conditions, statistical significance was tested at the lower of the 2 MICs and any concentrations between the MICs of the 2 conditions. (D) Bar plot of relative gene expression of 3 genes in C. difficile grown in fresh media, D. piger spent media (DP SM), and D. piger spent media with metal supplementation as detected by qRT-PCR. Fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Methods). Data points represent biological replicates, with each point calculated as the average of 3 technical replicates. Bar indicates the average of n = 4 biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined based on ΔCt values (S15 Fig). (E) Schematic of proposed mechanism for D. piger alteration of C. difficile metronidazole susceptibility. (Left) In monoculture, metals are available in the environment, and metal containing enzymes in C. difficile are expressed and reduce the prodrug metronidazole to its active form. (Right) In coculture with D. piger, hydrogen sulfide produced by D. piger sequesters metals, which forms metal sulfide precipitates. In response to metal limitation, the expression of metal binding proteins in C. difficile that reduce the conversion of metronidazole from prodrug to its active form is reduced. This in turn reduces the rate of conversion of metronidazole from its inactive to active form and increases the tolerance of C. difficile. The data underlying panels ABCD in this figure can be found in DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7626486. MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

Supplementation of D. piger spent media with combination of metals eliminates the protective effect of C. difficile from metronidazole

Based on the hypothesis that metal precipitation by hydrogen sulfide leads to an increase in C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC, we tested whether removing hydrogen sulfide from D. piger spent media eliminates this protective effect. The majority of hydrogen sulfide was eliminated from D. piger spent media by purging with nitrogen gas for 15 min (S16A Fig). We visually observed that nitrogen-purged spent media formed less ferrous sulfide precipitate than the untreated spent media (S16B Fig). Consistent with the proposed mechanism, the metronidazole MIC of C. difficile was reduced in the nitrogen-purged spent media compared to the untreated spent media (S16C and S16D Fig). This suggests that hydrogen sulfide contributed to the increase in C. difficile metronidazole MIC via metal precipitation.

Additionally, we hypothesized that supplementing D. piger spent media with metals that have precipitated would reduce the protective effect on C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC. We characterized C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC in media supplemented with cobalt, iron, manganese, nickel, and zinc since multiple divalent metals can form sulfide precipitates [49,50] and limitation of multiple divalent metals can lead to similar gene expression changes in C. difficile [35,36]. We introduced these metals in high concentrations (millimolar range) into the D. piger spent media to account for unreacted hydrogen sulfide that could precipitate the supplemented metals. Our results showed that C. difficile’s metronidazole MIC was substantially reduced in D. piger spent media supplemented with the five-metal combination compared to D. piger spent media without this addition (MIC decreased from 48 μg/mL to 3 μg/mL, Fig 6B). By contrast, C. difficile’s antibiotic MIC was not altered in fresh media supplemented with the five-metal combination, demonstrating that this effect was dependent on environmental modification by D. piger (S17A Fig). Supplementation of D. piger spent media with individual metals revealed that none of the individual metals decreased metronidazole MIC as substantially as the combination of metals (Fig 6C).

Consistent with these results, the expression of 3 genes that indicate metal limitation (fldX, feoB1, and zupT) was significantly reduced in C. difficile cultured in D. piger spent media supplemented with the metal combination compared to the spent media without metal supplementation (Figs 6D and S17B). Overall, this data suggests that metal limitation in D. piger spent media caused a global shift in C. difficile’s transcriptome and substantially reduced metronidazole susceptibility. Notably, both of these effects were eliminated by metal supplementation. Combining our data together, we propose a biological mechanism for the effect of D. piger on C. difficile’s metronidazole susceptibility (Fig 6E). In this proposed mechanism, hydrogen sulfide produced by D. piger sequesters divalent metals in the media. This in turn creates a metal limited environment for C. difficile, which leads to down-regulation of enzymes requiring metal cofactors for their activities. The down-regulated genes include enzymes that perform redox reactions that reduce metronidazole to its active form. Therefore, in coculture with D. piger, the activated concentration of metronidazole is reduced, yielding a substantially higher antibiotic MIC as a consequence of a reduction in DNA damage.

Discussion

A fundamental question is uncovering the role of biotic interactions in shaping antibiotic susceptibility in microbiomes. In particular, understanding how microbial interactions alter the antibiotic susceptibility of major human pathogens such as C. difficile could enable tailored antibiotic treatments informed by ecological context. This understanding could inform new microbiome interventions that selectively eradicate human pathogens while minimizing disruption of healthy gut microbiota and minimize the acquisition of antibiotic resistance. We investigated the contribution of interspecies interactions to the antibiotic susceptibility of a major human gut pathogen C. difficile. We observed 2 types of alterations in C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility: changes in C. difficile MIC and changes in C. difficile abundance at subinhibitory concentrations. Substantial changes in C. difficile MIC were rare in our conditions, only occurring in a small fraction of communities (S18A Fig). By contrast, enhancements in the abundance of C. difficile at subMICs were more frequently observed, occurring in 52% of characterized communities (S18B Fig). Our work demonstrates that pathogen growth can be altered by interspecies interactions across a wide range of antibiotic concentrations, which should be considered in the design of antibiotic treatments.

We observed a ≥4-fold increase in C. difficile’s MIC compared to monospecies in 4% of pairwise communities (Fig 2) and 16% of multispecies communities in response to single antibiotics (S1 and S2 Tables). This is qualitatively consistent with the small fraction of interspecies interactions shown to modify susceptibility in other microbial communities [12–15]. While we focused on antibiotics used to treat C. difficile, future work could apply our approach to study the impact of gut microbes on the response of C. difficile to antibiotics that are risk factors for initiating C. difficile infections such as clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones [52].

The observed increase in C. difficile metronidazole MIC in the presence of specific gut may contribute to the ineffectiveness of metronidazole in treating C. difficile infections in the human colon. Due to the low achieved metronidazole concentration in the human colon [53], even modest increases in C. difficile metronidazole MIC could allow the pathogen to survive. Based on our results, future testing of C. difficile antibiotic susceptibility could include conditions of C. difficile cultured with physiologically relevant microbial communities. For example, C. difficile could be cultured with a panel of resuspended fecal samples from multiple donors with disparate human gut microbiome compositions. Antibiotic treatments could be scored by balancing minimization of the disruption of healthy gut microbiota with minimization of the variability of C. difficile’s MIC across donor samples.

We propose a mechanism wherein D. piger depletes bioavailable divalent metals in the environment, resulting in transcriptional down-regulation of enzymes in C. difficile requiring metal cofactors. These enzymes are proposed to reduce metronidazole to its active form. This implies that a lower expression level of these enzymes protects C. difficile from the action of the antibiotic (Fig 6E). Iron limitation has been shown to increase microbial resistance to antibiotics with proton motive force (PMF)-dependent uptake due to the decrease in iron-sulfur containing complexes crucial for generating the PMF [54]. Because metronidazole passively diffuses into the cell independent of PMF [55], iron limitation likely impacts not the initial uptake rate of metronidazole but instead the conversion rate from prodrug to activated inhibitor. Our results are supported by previous studies that have identified a link between diminished intracellular iron levels and C. difficile metronidazole resistance [41,42]. Interestingly, heme limitation has previously been shown to sensitize C. difficile to metronidazole [56]. This is in contrast to the metal limitation induced metronidazole protection we observed here, suggesting a complex relationship between heme and non-heme iron and metronidazole susceptibility.

In our metal supplementation experiments, the cocktail of 5 metals caused a substantial decrease in C. difficile MIC, whereas the addition of individual metals, including iron alone, did not have this effect. We hypothesize that multiple metal cofactors are required for the enzymatic activities that contribute to metronidazole reduction. While some enzymes proposed to contribute to metronidazole reduction, such as PFOR, only require iron cofactors, others such as hydrogenase require both iron and nickel cofactors, supporting this hypothesis [20,21,39,57]. An alternative hypothesis is that iron is the major cofactor needed by enzymes that reduce metronidazole, but both iron and non-iron divalent metals are involved in the transcriptional regulation of these enzymes due to cross-regulation of iron and other divalent metals. A cross-regulation of the zinc and iron starvation responses has been demonstrated in Staphylococcus aureus [58].

Our proposed mechanism of metronidazole protection has implications beyond D. piger and C. difficile. There are multiple commensal species in addition to D. piger that can produce hydrogen sulfide [59]. These species may increase C. difficile metronidazole MIC through a similar mechanism. Beyond C. difficile, metronidazole is a widely used antibiotic to treat anaerobic bacterial infections [19], suggesting hydrogen sulfide producing bacteria could protect other pathogens from the action of metronidazole via divalent metal sequestration (S14 Fig).