Abstract

Background:

Informal caregivers of older adults experience a high degree of psychosocial burden and strain. These emotional experiences often stem from stressful tasks associated with caregiving. Caregiving supportive services that provide assistance for stressful tasks are instrumental in alleviating caregiving burden and strain. Research is limited on what types of supportive services caregivers are utilizing by relationship status and their source of information regarding these services. We sought to characterize caregiving supportive services use by caregiver relationship status.

Methods:

We analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2015 National Study of Caregiving limited to caregivers of older adults ≥65 years of age. Caregiver relationship status (i.e., spouse, child, other relative/non-relative) was the independent variable. Type of supportive service and source of information about supportive services were the dependent variables. Bivariate analyses were performed to examine the association with caregiver relationship status and associations between use of caregiving supportive services and caregiver and care recipient characteristics. Among service users, we measured associations between caregiver relationship status, type of supportive services used, and source of information about supportive services.

Results:

Our sample consisted of 1,871 informal caregivers, 30.7% reported using supportive services. By caregiver relationship status, children had the greatest use of supportive services compared to spouses and other relatives/non-relatives (46.5% vs. 27.6% vs. 25.9%, p=<0.01, respectively). Among users of services, there were no differences in type of services used. Spouses primarily received their information about services from a medical provider or social worker (73.8%, p=<0.001).

Conclusion:

Our findings highlight the need to ensure that other caregiving groups, such as spouses and other relatives/non-relatives, have access to important supportive services such as financial support. Medical providers and/or social workers should be leveraged and equipped to provide this information and refer to services accordingly.

INTRODUCTION

Over 40 million caregivers provide informal care to adults 65 years of age and older in the United States (US)1. Informal care consists of unpaid assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily needs such as toileting, medication management, food prep, and shopping and is typically provided by a spouse, child, neighbor, friend, or other family relative. Informal caregivers provide roughly 30 billion hours of care each year to family and friends at an estimated fiscal value of $522 billion annually2. Thus, informal caregivers are the primary source of long-term services and supports for older adults2. While this group provides a lion-share of care for older adults, this is not without its challenges and consequences to the caregivers themselves.

Informal caregivers of aging older adults experience a high degree of psychosocial burden and strain stemming from the stressors of caregiving, including the provision of direct personal services. Consequences may include a drain on physical strength, loss of personal time and family time, challenges to planning for the future,3 and adverse psychological outcomes4. Informal caregivers may lack the knowledge and skills to effectively communicate their caregiving stress despite having a need for increased caregiver assistance3.

Caregiving supportive services—such as respite care—that provide support for stressful tasks may be instrumental in alleviating the caregiving burden. Researchers have identified the association between access to supports (e.g., mindfulness training, group therapy) with lower burden and stress and improved caregiver quality of life (QOL). 5,6 Multicomponent interventions developed specifically for individual circumstances additionally decrease burden. These interventions may include health tools that assist with managing emotional stress, implementing environmental changes within the home, and handling finances.7

However, research is limited on the types of caregiving supportive services caregivers are utilizing by their relationship status to patients and the source of information related to these services8. Because utilization rates can be a helpful indicator for accessibility, filling this gap is critical to better understanding how best to increase equitable access to important supportive services for all caregivers (e.g., spouses, children, relatives/non-relatives). We sought to characterize caregiving supportive services use by caregiver relationship status to better understand who is using what services and how information about these services was made known to the caregiver.

METHODS

We analyzed cross-sectional publicly available data from the 2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and its linked caregiver survey, the 2015 National Study of Caregiving (NSOC). The NHATS began in 2011 and samples from the Medicare enrollment file to describe disability trends in a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older. Interviews are conducted annually. In 2015, the sample was replenished. Participants of NHATS provided names and contact information for caregivers for participation in the NSOC. Up to five caregivers per older adult were interviewed about caregiving activities and related experiences. NHATS and NSOC participants are linked based on the older adult’s ID number. De-identified data does not meet the definition of human subjects research and thus this study did not require institutional review board approval.

Sample

We limited our sample to caregivers providing assistance with routine daily activities to older adults who were living in the community. We excluded caregivers of older adults in residential care and nursing home settings.

Measures

The independent measure of interest was caregiver relationship status (i.e., spouse, child, other relative/non-relative).

The dependent measures of interest were type of caregiving supportive services and source of information about caregiving supportive services. Type of caregiving supportive services included respite, support group/counseling, training, and financial help for care recipient. Source of information about caregiving supportive services included government or community agency, medical care provider or social worker, church or synagogue, self or friend, or other source.

Analysis

Bivariate analyses were performed to examine both the associations between use of caregiving supportive services and caregiver and care recipient characteristics, and, among supportive service users, the associations between caregiver relationship status and type of caregiving supportive services used and source of information about caregiving supportive services. Analyses were performed using STATA.

Results

Our sample consisted of 1,871 informal caregivers. Nearly one-third (27.8%, n=574) of informal caregivers reported using caregiving supportive services. By caregiver relationship status, children had the greatest use of caregiving supportive services compared to other relatives/non-relatives and spouses (60.2% vs. 20.3% vs. 19.9%, p=<0.01, respectively). Caregivers who were African-American or Hispanic and other race or ethnicity, had more education, and cared for older adults receiving assistance with 3 or more self-care or mobility activities, had dementia, or were Medicaid-enrolled were more likely to use supportive services (all p-values <0.05). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Disabilities (2015)

| Characteristics | Caregiver Mean ± SD or n (%) |

P-value | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did Not Use Caregiving Support Services |

Used Caregiving Support Services |

Total | ||

| n (Row %) | n=1297 (72.2%) | n=574 (27.8%) | N=1871 | |

| Weighted (n) | 12,683,313 | 4,877,891 | 17,561,205 | |

| Age, years | 59.0 | 55.7 | <0.01 | 58.1 |

| Gender a | ||||

| Male | 39.4 | 36.3 | 0.44 | 38.5 |

| Female | 60.6 | 63.7 | 61.5 | |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 67.8 | 56.4 | 0.02 | 64.6 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 12.2 | 16.2 | 13.3 | |

| Hispanic and other | 19.9 | 27.4 | 22.0 | |

| Education | ||||

| No degree | 10.8 | 9.8 | <0.01 | 10.5 |

| GED or High school diploma | 49.6 | 44.4 | 48.1 | |

| Two or Four- year college degree | 22.0 | 31.0 | 24.5 | |

| Masters | 9.4 | 10.5 | 9.7 | |

| Professional | 8.2 | 4.4 | 7.1 | |

| Marital statusa | ||||

| Married | 58.8 | 59.8 | 0.81 | 59.1 |

| Has children a | ||||

| Yes | 83.3 | 83.3 | 0.99 | 83.3 |

| No | 16.7 | 16.7 | 16.7 | |

| Number of others living in household | ||||

| No other household members | 5.2 | 5.0 | 0.93 | 5.1 |

| 1 other household member | 11.4 | 10.2 | 11.1 | |

| 2 other household members | 45.9 | 46.3 | 45.9 | |

| 3 or more other household members | 37.6 | 38.6 | 37.9 | |

| Relationship to the care recipient | ||||

| Spouse | 25.9 | 19.5 | <0.01 | 24.1 |

| Wife/Female partner | 50.2 | 51.4 | 0.88 | 50.5 |

| Husband/Male partner | 49.8 | 48.6 | 49.5 | |

| Child | 46.5 | 60.2 | 50.3 | |

| Other relative/non-relative | 27.6 | 20.3 | 25.6 | |

| Care Recipient Characteristics | ||||

| Level of disability | ||||

| Household activities only | 28.5 | 23.0 | <0.001 | 27.0 |

| 1-2 Self-care/mobility activities | 46.8 | 32.6 | 42.8 | |

| 3 or more self-care/mobility activities | 24.8 | 44.4 | 30.2 | |

| Probable dementia | 22.3 | 33.0 | 0.007 | 25.3 |

| Medicaid-enrolled | 17.5 | 35.4 | <0.001 | 22.5 |

1,871 NSOC caregivers providing assistance to older adults living in the community (excluding residential care and nursing homes); Missing n=42 for age, n=17 for marital status, n=46 for has children.

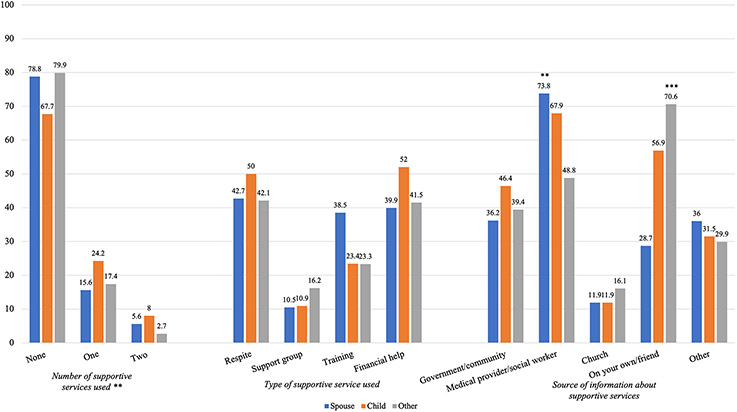

Among users of caregiving supportive services by caregiver relationship status, child caregivers were more likely to use two or more services (Figure 1). There were no differences in type of services used by caregiver relationship status, but respite and financial supportive services were used in the greatest proportions among all caregivers. Regarding source of information about caregiving supportive services, spouses primarily received their information about caregiving supportive services from a medical provider or social worker (73.8%, p=<0.001), and other relative and non-relative caregivers were more likely to find information about caregiving supportive services on their own or from a friend (70.6%, p=<0.001).

Figure 1. Bivariate Analyses of Supportive Service Use among Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Disabilities, by Caregiver Relationship.

Note. 1,871 NSOC caregivers providing assistance to older adults living in the community (excluding residential care and nursing homes). aOther source includes finding information about services from employer due to small cell sizes. Data reflect percentages. **p<0.01; **p<0.001. Spouse n=429 (24.1%); Child n=1021 (50.3%); Other Relative/Non-Relative n=290 (25.6%); weighted n’s = 4,238,904; 8,831,059; 4,491,241, respectively. Caregivers using supportive services: Spouse n=95 (19.5%); Child n=373 (60.2%); Other Relative/Non-Relative n= 106 (20.3%)

DISCUSSION

We sought to understand the utilization of caregiving supportive services for informal caregivers across relationship status. In a nationally representative sample of 1,871 informal caregivers, we found that less than one-third of informal caregivers are using caregiving supportive services. Among those who are, respite and financial help are the most commonly used supportive services and the greatest use of services were by children. To our knowledge, this study is the first nationally representative investigation to examine use of caregiving services by caregiver relationship status and our findings raise important implications for the provision of caregiving supportive services in the US.

Because the greatest use of services was among children, our findings highlight the need to understand any underlying barriers to use that may exist for other caregiving groups like spouses/partners, other relatives, or non-family caregivers. Previous literature has demonstrated that spouses, particularly solo spouses, exhibit high levels of caregiver stress—often greater than that of adult children9. Yet, this study shows that spouses are not utilizing these services at comparable rates to adult children caring for an aging parent, pointing to a potential disparity in how caregiver supportive services are designed, disseminated, and delivered. More research into why this disparity exists, whether they are personal, financial, cultural, geographical, or structural, is imperative as we draft policies and programs to ensure equitable access to these supportive services.

To promote this access to and utilization of these services, it is critical that we are meeting caregivers where they are using mechanisms that are common and customary to them and tailored to a wide range of caregiving groups. For example, children more commonly use digital resources to access information10 related to available caregiving supportive services. Such information can be readily available at the tip of one’s fingers, but only for those who are versed with technology. On the other hand, spouses may rely on receiving information related to caregiving supportive services through medical providers, word of mouth, personal networks, and traditional media11. It is also important to increase access to caregiving supportive services for all social supports in the patient’s life who provide caregiving and may not be from their family of origin. For instance, many sexual and gender minority patients (e.g., LGBTQ+) are supported by chosen families who are intricately involved in the patient’s life, health decision-making, care needs, and social identity12. However, information related to caregiving supportive services is not so commonly disseminated through these mediums and in ways that are easily understood. Healthcare personnel such as clinicians, healthcare providers, and/or social workers should be better leveraged and equipped to provide this information.

In recent years, family caregivers have been prioritized within recommendations adopted in policies such as the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act, Lifespan Respite Care Program, and National Family Caregiver Support Program13,14. These policies and programs support caregivers by providing respite options, service planning support, education, training, and financial security, for example13,15,16. Nearly all state managed long-term services and supports programs also include family caregivers in service planning and care coordination (upon the patient’s consent) and provide some services and supports (such as respite care or caregiver education and training) targeted to members’ family caregivers17. While these current and forthcoming efforts are laudable, their reach is limited if targeted efforts are not implemented to ensure that all caregivers have access to these resources and supports drawing on recommendations provided above. Provision of support to caregivers is additionally important for delaying and preventing unnecessary nursing home placements that are costly to the healthcare system. 14,16

There are limitations in our study design to note. First, because we do not have access to geographic information of the caregivers, we are unsure if the lack of use of supportive services was because of limited availability of caregiving supportive services or lack of knowledge. For example, there might not be a local caregiver support group in some towns, limiting utilization of this service; however, increasing prevalence and referrals to virtual support groups could help address this gap. Second, there is a chance that the needs of caregivers are being met in other areas not captured by the supportive services described herein. Next, we cannot assess factors that might reflect cultural preferences for caregiving supportive service use. Lastly, we did not estimate any regression models, nor did we control for any factors that might be driving or inhibiting use of caregiving supportive services. This was a first step to understanding supportive services use by caregiving relationship type, which future research might examine these issues in more depth. Moreover, taken together, our findings provide important information to improve access and use of supportive services for caregivers.

Conclusion

As care delivery for older adults is evolving to focus on home and community-based systems, an increasing amount of caregiving duties are falling on informal caregivers. Without adequate access to caregiving services, this model for care delivery may not be sustainable. Importantly, caregivers are not a monolith—in which the needs of a spousal caregiver can differ greatly from an adult child. It is imperative that future research works to understand and mitigate any barriers that may limit a caregiver’s access to their support service of choice. Furthermore, as we develop new models to deliver caregiving supportive services, it is critical to not only promote access, but recognize the diversity within the caregiving population and tailor these services to their unique strengths. To ensure high quality care for older adults, we must shift our focus, at all levels of healthcare delivery, to include not only the multifaceted needs of the individual patient, but those of their caregivers as well.

Key Points

Less than one-third of informal caregivers of older adults are using caregiving supportive services

Among informal caregivers using caregiving supportive services, respite and financial help are the most common services accessed.

The greatest proportion of caregiving supportive services were used by adults who serve as caregivers for their parents.

Why does this matter?

Use of support services varies significantly across types of informal caregivers, suggesting the need to better understand associative factors with these differences and subsequently ensure appropriate referrals and education about accessing supportive services in the future. Study findings provide information on caregiver groups in need and suggest ways to best target them for increased supportive service engagement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Harold Amos career development award funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [RWJF; 77872 to J.L.T]. J.L.T is additionally supported by an award from the National Institute on Aging [K76 AG074922-01 to J.L.T]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or the National Institutes of Health. Moreover, the funders had no role in the design and conduct of this study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding:

This work is supported by a Harold Amos career development award funded by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [77872 to JLT]. JLT is supported by an award from the National Institute on Aging [NIA]; K76 AG074922 to JLT). WER acknowledges the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 (PI: C. Thompson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Robert Wood Johnson Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

SPONSOR’S ROLE

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose related to this work

References

- 1.Stepler R. 5 Facts About Family Caregivers. Pew Research Center. 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/11/18/5-facts-about-family-caregivers/#:~:text=There%20are%2040.4%20million%20unpaid,the%20Bureau%20of%20Labor%20Statistics [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray KN, Mehrotra A. The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: new estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Serv Res. Jun 2015;50(3):871–82. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garlo K, O'Leary JR, Van Ness PH, Fried TR. Burden in caregivers of older adults with advanced illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. Dec 2010;58(12):2315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03177.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musich S, Wang SS, Kraemer S, Hawkins K, Wicker E. Caregivers for older adults: Prevalence, characteristics, and health care utilization and expenditures. Geriatr Nurs. Jan - Feb 2017;38(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piersol CV, Canton K, Connor SE, Giller I, Lipman S, Sager S. Effectiveness of Interventions for Caregivers of People With Alzheimer's Disease and Related Major Neurocognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Am J Occup Ther. Sep/Oct 2017;71(5):7105180020p1–7105180020p10. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2017.027581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. Mar 12 2014;311(10):1052–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. Aug 2008;20(8):423–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dionne-Odom JN, Applebaum AJ, Ornstein KA, et al. Participation and interest in support services among family caregivers of older adults with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(3):969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ornstein KA, Wolff JL, Bollens-Lund E, Rahman O-K, Kelley AS. Spousal caregivers are caregiving alone in the last years of life. Health Affairs. 2019;38(6):964–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park E, Kwon M. Health-Related Internet Use by Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. Apr 3 2018;20(4):e120. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs W, Amuta AO, Jeon KC. Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Social Sciences. 2017/January/01 2017;3(1):1302785. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2017.1302785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosa WE, Banerjee SC, Maingi S. Family caregiver inclusion is not a level playing field: toward equity for the chosen families of sexual and gender minority patients. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2022;16:26323524221092459. doi: 10.1177/26323524221092459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Support to Caregivers ∣ ACL Administration for Community Living. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers

- 14.National Family Caregiver Support Program ∣ ACL Administration for Community Living. . Accessed November 14, 2021. https://acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/national-family-caregiver-support-program

- 15.Congress Passes, Trump Signs RAISE Family Caregivers Act “Elevating Caregiving To A Priority.”. Accessed November 14, 2021, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robinseatonjefferson/2018/01/24/congress-passes-trump-signs-raise-family-caregivers-act-elevating-caregiving-to-a-priority/?sh=54c33dd7331f

- 16.RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council ∣ ACL Administration for Community Living. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/raise-family-caregiving-advisory-council

- 17.Kasten J, L E, Lelchook S, Feinberg L, Hado E. Recognition of Family Caregivers in Managed Long-Term Services and Supports. AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]