Abstract

Hypothesis:

Microneedle-mediated intracochlear injection through the round window membrane (RWM) will facilitate intracochlear delivery, not affect hearing, and allow for full reconstitution of the RWM within 48 hours.

Background:

We have developed polymeric microneedles that allow for in vivo perforation of the guinea pig RWM and aspiration of perilymph for diagnostic analysis, with full reconstitution of the RWM within 48–72 hours. In this study, we investigate the ability of microneedles to deliver precise volumes of therapeutics into the cochlea and assess the subsequent consequences on hearing.

Methods

Volumes of 1.0 μL, 2.5 μL, or 5.0 μL of artificial perilymph were injected into the cochlea at a rate of 1 μL/min. Compound action potential (CAP) and distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) were performed to assess for hearing loss (HL), and confocal microscopy was used to evaluate the RWM for residual scarring or inflammation. To evaluate the distribution of agents within the cochlea following microneedle-mediated injection, 1.0 μL of FM 1–43 FX was injected into the cochlea, followed by whole mount cochlear dissection and confocal microscopy.

Results

Direct intracochlear injection of 1.0 μL of artificial perilymph in vivo, corresponding to about 20% of the scala tympani volume, was safe and did not result in HL. However, injection of 2.5 μL or 5.0 μL of artificial perilymph into the cochlea produced statistically significant high-frequency HL persisting 48 hours post-perforation. Assessment of RWMs 48 hours after perforation revealed no inflammatory changes or residual scarring. FM 1–43 FX injection resulted in distribution of the agent predominantly in the basal and middle turns.

Conclusion

Microneedle-mediated intracochlear delivery of small volumes relative to the volume of the scala tympani is feasible, safe, and does not cause HL in guinea pigs; however, injection of large volumes induces high-frequency HL. Injection of small volumes of a fluorescent agent across the RWM resulted in significant distribution within the basal turn, less distribution in the middle turn, and almost none in the apical turn. Microneedle-mediated intracochlear injection, along with our previously developed intracochlear aspiration, opens the pathway for precision inner ear medicine.

Keywords: microneedle, round window membrane, intracochlear delivery, precision medicine

Introduction

As the only non-ossified portal into the cochlea, the RWM has been the target for many methods of intracochlear access1,2. In mammalian models, drug-eluting cochlear implants containing dexamethasone or growth factors have been shown to be neuroprotective following implant insertion3–5; biodegradable PLGA implants have also been used to allow for resorption of implants over time6. Additionally, RWM implants such as the Hybrid Ear Cube can be used for treatment of inner ear disorders requiring long-term dosing of therapeutics7. Though implants are effective and reliable for intracochlear access, they are often permanent and require significant lifestyle modification for long-term maintenance. Direct intracochlear injection through the RWM is a more transient means of drug administration to the cochlea, and studies have demonstrated greater concentrations compared to intratympanic injections8,9; in fact, direct injection of triamcinolone has been utilized to reduce impedances immediately prior to cochlear implantation10. However, current methods of intracochlear injection involve significant trauma to the RWM, and often produce hearing loss and perilymphatic leakage through the resultant perforation. A methodology for minimally traumatic RWM perforation and intracochlear injection is thus highly warranted.

Our laboratory has designed ultrasharp microneedles capable of reliably perforating the RWM with minimal effects on hearing and RWM anatomy11–13. Specifically, we used two-photon polymerization lithography (2PP) to direct-write microneedles with varying length, sharpness, taper angle, diameter, and cross-sectional design. Puncture of the guinea pig RWM with 100 μm diameter ultrasharp microneedles, with a tip radius of curvature of 500 nm, resulted in oval, lens-shaped perforations with a mean major axis of 95.9 μm and mean minor axis of 25.4 μm11; perforations healed completely within 48–72 hours with no notable shifts in hearing thresholds12. Importantly, incorporation of a 35 μm hollow lumen in the 100 μm microneedle allowed for aspiration of 1 μL of perilymph from the cochlea without changes in hearing; LC-MS proteomic characterization of the aspirate identified 620 guinea pig proteins, including the inner ear protein cochlin14. In fact, proteomic characterization of microneedle-mediated aspirate was precise enough to identify changes in the proteome following corticosteroid administration, with the nerve growth factor VGF significantly upregulated after both intraperitoneal (IP) and intratympanic (IT) dexamethasone administration15.

We have demonstrated that microneedle-mediated perforation of the RWM ex vivo significantly enhances diffusion of rhodamine into the cochlea16; however, to date we have not attempted direct intracochlear injection in vivo. The purpose of this study is to evaluate hollow microneedles for direct intracochlear injection of agents. To assess the safety of microneedle-mediated intracochlear injection, we inject varying volumes (1.0–5.0 μL) of artificial perilymph into the cochlea in vivo; to test the distribution of agents in the cochlea following microneedle-mediated injection, we use the fluorescent marker FM 1–43 FX, which is taken up by a variety of cell types, including hair cells, in vivo via receptor-mediated endocytosis17,18.

Materials and Methods

Microneedle design and synthesis

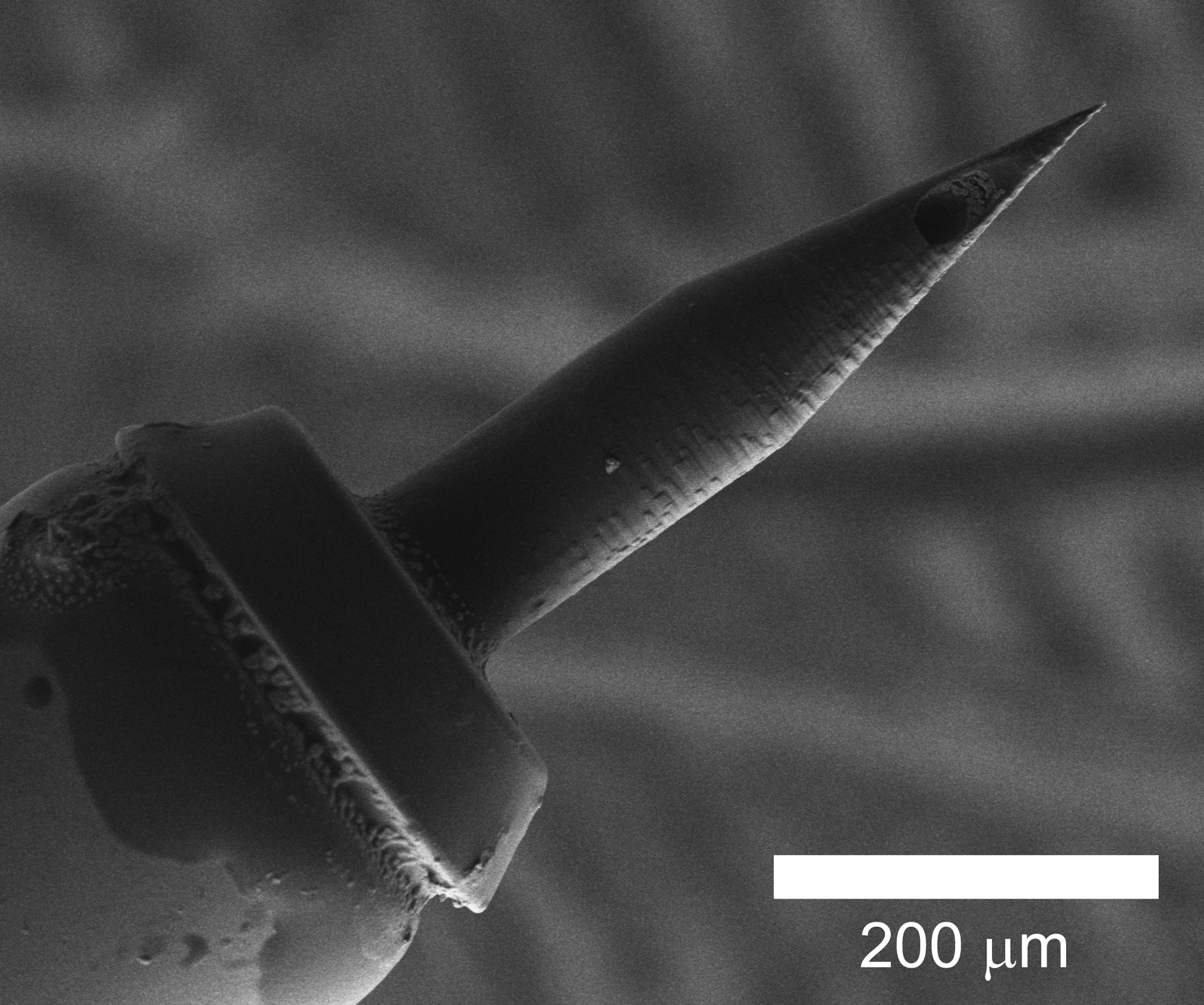

Microneedles were designed with SolidWorks software (Dassault Systems SolidWorks Corporation, Concord, NH) and stereolithography files were constructed using Describe software (Nanoscribe GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) at a slicing distance of 1 μm and laser intensity of 80%. Microneedles were then synthesized with the Photonic Professional GT 2PP system using photoresist IP-S (Nanoscribe GmbH). The outer diameter of the needle was set to 100 μm with inner diameter 35 μm and a tip radius of curvature of 500 nm. The inner lumen was placed centrally with curvature near the needle tip such that the lumen opened at the side of the needle tip (Figure 1). Additionally, the outer diameter at the base of the needle was increased to 139 μm with inner diameter 95 μm so to decrease overall fluid resistance. Details of hollow microneedle design and scanning electron microscopy of microneedles have been reported previously14,15. In contrast, current medically approved 34-gauge needles have nominal inner diameter of 51 μm and nominal outer diameter of 159 μm19,20. Our microneedles are significantly smaller with 35 μm and 100 μm inner and outer diameter, respectively. In addition, our microneedles are ultrasharp (i.e. with tip radius of curvature < 1 μm), allowing for RWM perforation in a minimally traumatic manner. Lastly, the significant design freedom of our construct allows us to tailor our microneedles to the specific needs of the clinician or surgeon.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscope image of a single-lumen hollow microneedle. A 200 μm scale bar is displayed for reference.

Direct intracochlear injection

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). A total of 20 Hartley guinea pigs weighing 200–300 g was obtained from a commercial vendor (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA); 15 were used for artificial perilymph injection, 4 were used for FM 1–43 FX distribution assessment, and 1 was used as control. For artificial perilymph injections, animals were divided into 3 groups each receiving 1.0 μL, 2.5 μL, or 5.0 μL of artificial perilymph (each with n = 5). For FM 1–43 FX experiments, 4 animals received 1.0 μL of FM 1–43 FX and 1 was used for comparison. All procedures were completed on the right ear. Guinea pigs were anesthetized with isoflurane gas (3.0% for induction, 1.0–3.0% for maintenance) and administered buprenorphine sustained release (0.1 mg/kg) and meloxicam (0.5 mg/kg) for analgesia. Lidocaine was also injected in the post-auricular area for local anesthesia. To reduce head movements from deep breaths, the head was fixed with a modular 3D-printed head holder consisting of two screws placed anterior to the external auditory meatus and posterior to the orbit21; lidocaine was injected at the screw fixation sites for local anesthesia.

A 1 cm post-auricular incision was made with a scalpel blade, and blunt dissection was used to expose the tympanic bulla and the facial nerve emerging from bone. A Stryker S2 πDrive drill (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) with a 1 mm drill tip was used to open the bulla, and fine forceps were used to remove bone and form a 2–3 mm opening into the middle ear space (Supplementary Figure 1). A hollow microneedle, mounted on a 2 inch, 30 gauge, blunt, small hub removable needle (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV), was attached to a 10 μL Gastight Hamilton syringe (Model 1701 RN, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV); the syringe in turn was secured to a UMP3 UltraMicroPump (World Precise Instruments, Sarasota, FL), which was fixed to a micromanipulator. Using the micromanipulator, the hollow microneedle was advanced into the middle ear space and the RWM was perforated. Downward RWM displacement with initial microneedle contact was noted, followed by upward deflection of the RWM upon microneedle entry into the inner ear space. For animals receiving artificial perilymph (NaCl 120 mM, KCl 3.5 mM, CaCl2 1.5 mM, glucose 5.5 mM, HEPES 20 mM, NaOH to pH = 7.5), 1.0 μL, 2.5 μL, or 5.0 μL of artificial perilymph was injected into the inner ear space with a rate of 1 μL/min. For animals receiving FM 1–43 FX (FM 1–43 FX, fixable analog of FM 1–43 membrane stain, Thermo Fischer Scientific), 1.0 μL of 70 μM FM 1–43 FX in artificial perilymph was injected into the cochlea at a rate of 1 μL/min. Upon retraction of the microneedle from the RWM, the lens-shaped perforation on the RWM was visualized as confirmation.

Guinea pigs were euthanized with phenytoin/pentobarbital overdose 48 hours after RWM perforation in the artificial perilymph group and 1 hour after perforation in the FM 1–43 FX group. For animals receiving artificial perilymph injection, simple interrupted sutures were used to close the postauricular incision, and guinea pigs were returned to the animal facility for recovery. Cochleae were harvested 48 hours after artificial perilymph injection and stained with 1 mM rhodamine B, a fluorescent stain for elastic tissue, for 5 minutes and rinsed with PBS. For animals receiving FM 1–43 FX, cochleae were harvested, fixed for 24 hours in 4% formalin injected into the cochlea through the RWM, washed with PBS, and decalcified for 7–10 days in 0.15 M EDTA. Decalcified cochleae were subsequently dissected into three pieces representing the basal, middle, and apical turns and mounted on glass slides using VECTASHIELD antifade mounting medium.

Audiometric tests

Compound action potential (CAP) and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) were used to evaluate hearing for animals receiving artificial perilymph, as described previously12,14,15,22,23. CAP was measured immediately prior to perforation, while DPOAE was measured prior to perforation and 1 hour following perforation. Both CAP and DPOAE were measured 48 hours following injection. All hearing tests were completed under anesthesia.

CAP measurements summate individual action potentials at the cochlear base following sound stimulation, thereby measuring the activity of the cochlear nerve. Tone pips generated with a Tucker Davis Technologies (TDT) system (Tucker Davis Technologies Inc., Alachua, Florida) in a closed-field configuration were played to the right ear through an ear tube speaker. A silver electrode was used to measure electrical activity at the cochlear base; a reference electrode was placed in nearby fascia and a ground electrode was inserted in the skin by the scapular ridge. CAP responses were measured for a total of 18 frequencies ranging from 0.5 kHz to 40 kHz. Tone intensities were increased at 5 dB SPL increments, and the lowest amplitude to produce a discernable response curve was identified as the hearing threshold. Experimenters were blinded to all previous threshold measurements to reduce bias. Two-tailed paired t-tests with a significance level of 0.05 were used to evaluate for significant changes.

DPOAE measurements are responses produced by cochlear outer hair cells upon stimulation by two pure tone frequencies played simultaneously. Thus, DPOAE measurements assess the health of outer hair cells as a proxy for potential hearing loss. An ear tube containing a speaker and a low-noise Sokolich ultrasonic probe microphone was placed in the external auditory canal, and simultaneous sound stimuli were generated at 70 and 80 dB SPL using the TDT system described above. Stimuli had a fixed frequency ratio of f2/f1 = 1.2 with f1 ranging from 1 kHz to 32 kHz at 1 kHz increments. Distortion products were detected by the microphone, and DPOAE measurements with 2f1 – f2 = 3 dB above the noise floor level were identified as positive responses. Repeated measures ANOVA tests, followed by pairwise two-tailed paired t-tests with a significance level of 0.05, were used to evaluate for significant changes.

Confocal imaging and quantification

Confocal microscopy was used to assess RWM healing following artificial perilymph injection and hair cell distribution following FM 1–43 FX injection. A Nikon A1R laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) was used to acquire z-stack images through RWMs and basal, middle, and apical turns of the cochlea. For RWMs, images were obtained using a Nikon 10x Plan Apo VC (0.45 NA) objective with 1.0 optical zoom, with pixel size 1.2 × 1.2 μm and 5 μm step size. Samples were scanned with a 561 nm laser line with a pixel dwell time of 1.1 μs, and emitted light at 570–620 nm was allowed into the detector. Maximum intensity projection images were generated from z-stacks using NIS-Elements (Nikon) to visualize RWMs and examine for residual scarring or inflammation. For cochlear turns, images were obtained using the same objective with pixel size 1.2 × 1.2 μm and 1 μm step size. Samples were scanned with a 478 nm laser line with a pixel dwell time of 1.1 μs, and emitted light at 570–620 nm was allowed into the detector. Maximum intensity projection images with 20 μm depth were generated from z-stacks using NIS-Elements (Nikon) and Fiji (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Results

Microneedle-mediated intracochlear injection of artificial perilymph

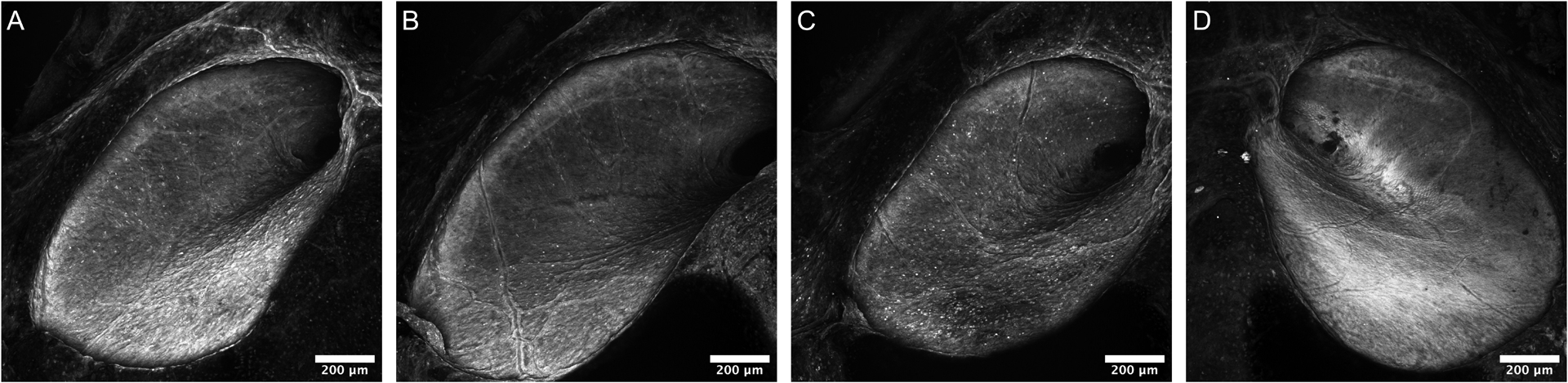

CAP and DPOAE data were obtained for all 15 animals undergoing microneedle-mediated injection of artificial perilymph. Perforations were well-visualized under light microscopy for all 15 animals immediately following microneedle-mediated injection; self-limiting perilymph efflux from the perforation site was also noted for all 15 animals. Confocal imaging of RWMs harvested 48 hours following injection revealed full reconstitution with no residual perforation, inflammation, or scarring. Examples of healed RWMs are displayed in Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c, for 1.0 μL, 2.5 μL, and 5.0 μL injections, respectively. An unperforated RWM is shown in Figure 2d for comparison.

Figure 2.

Confocal images of RWMs 48 hours after microneedle-mediated injection of 1.0 μL (A), 2.5 μL (B), and 5.0 μL (C) of artificial perilymph, 100x magnification. A confocal image of an unperforated RWM is displayed for comparison (D). A 200 μm scale bar is displayed for reference. No residual perforation, inflammation, or scarring is noted in any of the images.

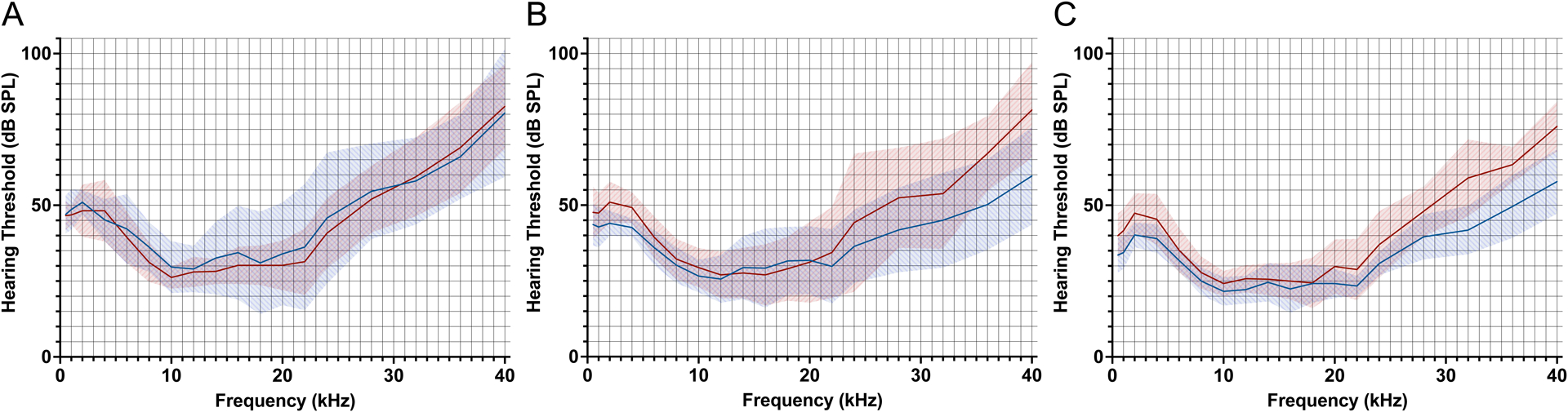

Figure 3.

Mean CAP thresholds immediately preceding microneedle-mediated injection of artificial perilymph (blue line) and 48 hours following injection (red line), for 1.0 μL (A), 2.5 μL (B), and 5.0 μL (C) injections. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. No threshold shifts are observed for 1.0 μL injection; predominantly high-frequency threshold shifts are observed for 2.5 μL and 5.0 μL injections.

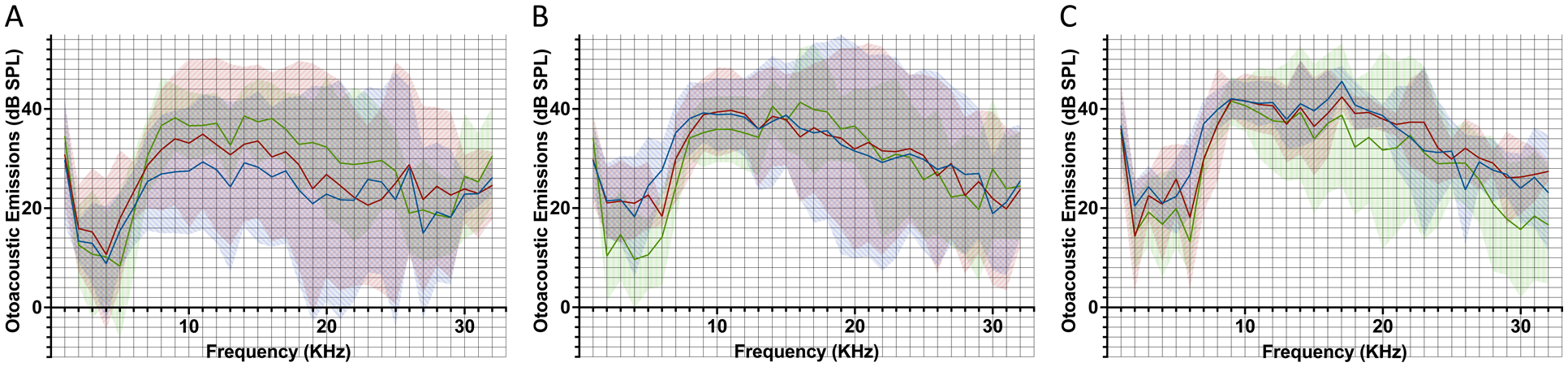

For animals receiving 1.0 μL of artificial perilymph, there were no significant CAP threshold shifts at any tested frequencies 48 hours following perforation (Figure 3a), with p > 0.05 at all tested frequencies (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, DPOAEs remained above the noise floor for all tested frequencies (Figure 4a). There was one significant change in DPOAE at 28 kHz (p = 0.012), with pairwise t-testing revealing higher DPOAE 1 hour post-perforation compared to pre-perforation (p = 0.0096); all other tested frequencies revealed no significant differences in DPOAEs obtained pre-perforation, 1 hour post-perforation, and 48 hours post-perforation (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 4.

Mean DPOAEs immediately preceding microneedle-mediated injection of artificial perilymph (blue line), 1 hour following injection (red line), and 48 hours following injection (green line), for 1.0 μL (A), 2.5 μL (B), and 5.0 μL (C) injections. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. All DPOAEs remain above the noise level and no significant differences are noted for any of the presented frequencies.

For animals receiving 2.5 μL of artificial perilymph, there were significant CAP threshold shifts at 2 kHz (7 dB, p = 0.031), 36 kHz (16.8 dB, p = 0.025), and 40 kHz (21.8 dB, p = 0.033) 48 hours following perforation (Figure 3b) (Supplementary Table 1). DPOAEs remained above the noise floor for all tested frequencies (Figure 4b). There were no significant differences in DPOAEs obtained pre-perforation, 1 hour post-perforation, and 48 hours post-perforation, for all tested frequencies (Supplementary Table 2).

For animals receiving 5.0 μL of artificial perilymph, there were significant CAP threshold shifts at 0.5 kHz (6.4 dB, p = 0.025), 1 kHz (7.2 dB, p = 0.010), 2 kHz (7.2 dB, p = 0.015), 12 kHz (3.6 dB, p = 0.0061), 32 kHz (17.2 dB, p = 0.0039), 36 kHz (13.8 dB, p = 0.0054), and 40 kHz (18.2 dB, p = 0.00036) 48 hours following perforation (Figure 3c) (Supplementary Table 1). DPOAEs remained above the noise floor for all tested frequencies (Figure 4c). There was one significant change in DPOAE at 30 kHz (p = 0.012), with pairwise t-testing revealing no significant differences; all other tested frequencies did not reveal significant differences in DPOAEs obtained pre-perforation, 1 hour post-perforation, and 48 hours post-perforation (Supplementary Table 2).

Microneedle-mediated intracochlear injection of FM 1–43 FX

A safe injection volume of 1.0 μL was chosen based on the artificial perilymph studies described above. Following microneedle-mediated injection, the RWM perforation was well-visualized under light microscopy; self-limiting perilymph efflux from the perforation site was also noted. Confocal imaging of dissected cochleae fixed 1 hour following FM 1–43 FX injection revealed fluorescence throughout the basal and middle turns (Figure 5d–e), with definition of outer hair cells, inner hair cells, and neurons in the basal turn and variable fluorescence of outer and inner hair cells in the middle turn. In contrast, little fluorescence was noted in the apical turn (Figure 5f), and no significant fluorescence above background was noted in the comparison cochlea (Figures 5a–c).

Figure 5.

(A-C) Confocal images of the basal (A), middle (B), and apical (C) turns of a non-injected cochlea vs. the basal (D), middle (E), and apical (F) turns of a cochlea injected with 1.0 μL of 70 μM FM 1–43 FX, 100x magnification. Samples were fixed 1 hour following FM 1–43 FX injection. A 100 μm scale bar is displayed for reference. Following FM 1–43 FX injection, fluorescence of outer hair cells, inner hair cells, and neurons is observed in the basal turn; fluorescence of outer and inner hair cells is observed in the middle turn; little fluorescence is observed in the apical turn. No significant fluorescence above background is noted in the comparison cochlea.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that microneedle-mediated injection of up to 1.0 μL of injectate is safe and effective for intracochlear delivery of agents. Injection of 1.0 μL of artificial perilymph does not impair hearing and allows for full reconstitution of the RWM; additionally, injection of 1.0 μL of FM 1–43 FX produces fluorescence in the basal and middle turns of the cochlea. These results support the use of microneedles for intracochlear drug delivery, most notably for precision therapeutics like gene therapy. A reliable and innocuous means of accessing the cochlea will thus promote the advancement of new therapies for hearing disorders, many of which are nearly impossible to treat due to the inaccessibility of the inner ear.

Although 1.0 μL of artificial perilymph may be injected without anatomic or physiologic consequences on the inner ear, injection of 2.5 μL or 5.0 μL results in moderate hearing loss in the high frequencies (32–40 kHz range) and mild hearing loss in the low frequencies (0.5 kHz to 2 kHz range) based on CAP. For all injections, confocal imaging of the RWM revealed no residual perforation, scarring, or inflammation, indicating that loss of RWM integrity was not the cause of hearing loss for higher volume injections. Given that the total volume of the guinea pig scala tympani (ST) is close to 5 μL24, we suggest that injection of 2.5 μL to 5 μL, or 50% to 100% of the ST volume, increases pressure in the inner ear to an intolerable level, leading to damage of critical structures within the cochlea. Interestingly, DPOAEs for all three injection volumes were relatively unremarkable, suggesting that hair cell health was preserved despite increases in pressure. An additional histological analysis of hair cells, sensory neurons, basilar membrane, and tectorial membrane following intracochlear injection would have provided information on the structures potentially injured in large-volume injections.

In guinea pigs, the cochlear aqueduct is typically patent and plays some role in transmitting excessive pressure buildup to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space25; however, at volumes exceeding 50% of the total ST volume, this pressure relief is likely insufficient to prevent damage to hearing structures. In humans, the cochlear aqueduct is typically closed26, which implies that the human inner ear is likely more sensitive to pressure changes than the guinea pig inner ear. However, future studies on human cochleae are required to confirm this hypothesis. A cochleostomy in the cochlear apex may be introduced to relieve the buildup of pressure following microneedle-mediated injection, but the authors do not believe that this technique is safe for translation into human subjects.

We find that an injection volume of 1.0 μL is sufficient to produce distribution of FM 1–43 FX within the cochlea. Notably, we observe the greatest degree of fluorescence in the basal turn, with somewhat less fluorescence in the middle turn and relatively little fluorescence in the apical turn, which is consistent with previous studies reporting a strong basal-apical gradient17,18. In a comparable experiment by Ayoob et al., a cochleostomy near the RWM was performed and 2.0 μL of 35 μM FM 1–43 FX was infused at a rate of 1 μL/min, producing a basal-apical gradient that persisted for 72 hours17. In this experiment, we injected 1.0 μL of 70 μM FM 1–43 FX directly through the RWM, at a rate of 1 μL/min. We thus demonstrate that a smaller volume injection through the RWM is sufficient to produce a similar distribution within the cochlea. We would also expect this gradient to persist at the 72 hour timepoint, as persistence of fluorescence occurs through FM 1–43 FX transduction into the scala media through local pathways, but future experiments are necessary to confirm this hypothesis17.

Following FM 1–43 FX injection, we observe notable fluorescence of inner hair cells, pillar cells, and outer hair cells in the basal turn, but variable fluorescence of the outer and inner hair cells in the middle turn, which may result from the greater concentration of fluorescent agent reaching the basal turn compared to the middle turn. Thus, drug delivery through the RWM would preferentially target the basal turn, with moderate activity in the middle turn and little activity in the apical turn. The basal-apical gradient seen in this study, and previous studies, may be attributable to loss of agent through the cochlear aqueduct, or inadequate volume of agent in the intracochlear injectate. Future iterations of our microneedle technology may allow us to overcome the volume limitation inherent to intracochlear injection, which would potentially allow for greater distribution throughout the apical turn. Additionally, confocal imaging of brainstem slices may be a methodology for quantification of the amount of agent lost to the CSF space.

In other studies, cochleostomy was sealed following FM 1–43 FX delivery, often with a permanent cement (i.e. Durelon carboxylate cement); in our study, no such sealing agent was applied to the RWM following perforation. Thus, following injection, efflux of perilymph from the perforation site occurred as expected for all animals, though this efflux was self-limiting. Importantly, despite perilymph efflux, delivery of FM 1–43 FX via microneedle-mediated perforation of the RWM allowed for significant distribution throughout the basal and middle turns, indicating that the majority of the FM 1–43 FX injected through the RWM traversed the inner ear rather than escaping into the middle ear.

Our polymeric microneedle design was a major strength in that our microneedles were durable enough to sustain both RWM perforation and fluid injection while maintaining their ultrasharp structure to prevent excessive RWM trauma. Additionally, the polymeric material used to construct our microneedles has been shown to be biocompatible according to ISO 10993–5 and thus has the potential to be translated for human trials27. We have also developed a methodology called two-photon templated electrodeposition (2PTE) to synthesize ultrasharp, gold-coated copper microneedles, which are, in principle, biocompatible and have greater strength than our polymeric microneedles28. Although our microneedle designs have not yet been approved for human use, we have extensively demonstrated their safety in guinea pigs, in this study and in previous studies. Given the versatility of our microneedle designs, our microneedles will likely be compatible with a variety of injection agents, including conventional therapies (aminoglycosides29, corticosteroids30), genetic therapies (therapeutic RNAs31,32, viral vectors33,34), and cellular therapies (growth factors4, stem cells5). Future experiments with these agents and iterative changes to our microneedle design will help to maximize compatibility between our technology and various injectable agents.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Surgical view of the right tympanic bulla under dissecting microscope, 25x magnification. RWM: round window membrane. VII: facial nerve. ISJ: incudostapedial joint. TM: tympanic membrane annulus. BT: basal turn of cochlea. BM: basilar membrane. A 1 mm scale bar is displayed for reference.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: Co-authors Anil K. Lalwani, Aykut Aksit and Jeffrey W. Kysar have co-founded a company called Haystack Medical, Inc., with the intention to commercialize microneedles to treat hearing and balance disorders.

References

- 1.Szeto B, Chiang H, Valentini C, Yu M, Kysar JW, Lalwani AK. Inner ear delivery: Challenges and opportunities. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(1):122–131. doi: 10.1002/lio2.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salt AN, Hirose K. Communication pathways to and from the inner ear and their contributions to drug delivery. Hear Res. 2018;362:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang J, Kim JY, Kim YC, et al. A 3D Microscaffold Cochlear Electrode Array for Steroid Elution. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(20):e1900379. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bas E, Anwar MR, Goncalves S, et al. Laminin-coated electrodes improve cochlear implant function and post-insertion neuronal survival. Neuroscience. 2019;410:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.04.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheper V, Hoffmann A, Gepp MM, et al. Stem Cell Based Drug Delivery for Protection of Auditory Neurons in a Guinea Pig Model of Cochlear Implantation. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13. Accessed March 19, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fncel.2019.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehner E, Menzel M, Gündel D, et al. Microimaging of a novel intracochlear drug delivery device in combination with cochlear implants in the human inner ear. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(1):257–266. doi: 10.1007/s13346-021-00914-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehrke M, Verin J, Gnansia D, et al. Hybrid Ear Cubes for local controlled dexamethasone delivery to the inner ear. Eur J Pharm Sci Off J Eur Fed Pharm Sci. 2019;126:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salt AN, Sirjani DB, Hartsock JJ, Gill RM, Plontke SK. Marker retention in the cochlea following injections through the round window membrane. Hear Res. 2007;232(1–2):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plontke SK, Hartsock JJ, Gill RM, Salt AN. Intracochlear Drug Injections through the Round Window Membrane: Measures to Improve Drug Retention. Audiol Neurotol. 2016;21(2):72–79. doi: 10.1159/000442514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prenzler NK, Salcher R, Lenarz T, Gaertner L, Warnecke A. Dose-Dependent Transient Decrease of Impedances by Deep Intracochlear Injection of Triamcinolone With a Cochlear Catheter Prior to Cochlear Implantation–1 Year Data. Front Neurol. 2020;11:258. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aksit A, Arteaga DN, Arriaga M, et al. In-vitro perforation of the round window membrane via direct 3-D printed microneedles. Biomed Microdevices. 2018;20(2):47. doi: 10.1007/s10544-018-0287-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu M, Arteaga DN, Aksit A, et al. Anatomical and Functional Consequences of Microneedle Perforation of Round Window Membrane. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2020;41(2):e280–e287. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang H, Yu M, Aksit A, et al. 3D-Printed Microneedles Create Precise Perforations in Human Round Window Membrane in Situ. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2020;41(2):277–284. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szeto B, Aksit A, Valentini C, et al. Novel 3D-printed hollow microneedles facilitate safe, reliable, and informative sampling of perilymph from guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2021;400:108141. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2020.108141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szeto B, Valentini C, Aksit A, et al. Impact of Systemic versus Intratympanic Dexamethasone Administration on the Perilymph Proteome. J Proteome Res. 2021;20(8):4001–4009. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelso CM, Watanabe H, Wazen JM, et al. Microperforations significantly enhance diffusion across round window membrane. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(4):694–700. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayoob AM, Peppi M, Tandon V, Langer R, Borenstein JT. A fluorescence-based imaging approach to pharmacokinetic analysis of intracochlear drug delivery. Hear Res. 2018;368:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayoob AM, Peppi M, Tandon V, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Intracochlear drug delivery: Fluorescent tracer evaluation for quantification of distribution in the cochlear partition. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;126:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton Needle Point Style Guide | Hamilton Company. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.hamiltoncompany.com/laboratory-products/needles-knowledge/needle-point-style#point-styles

- 20.Needle Gauge Chart | Syringe Needle Gauge Chart | Hamilton. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.hamiltoncompany.com/laboratory-products/needles-knowledge/needle-gauge-chart

- 21.Valentini C, Ryu YJ, Szeto B, Yu M, Lalwani AK, Kysar J. A Novel 3D-Printed Head Holder for Guinea Pig Ear Surgery. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2021;42(9):e1197–e1202. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000003255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Olson ES. Cochlear perfusion with a viscous fluid. Hear Res. 2016;337:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallah E, Strimbu CE, Olson ES. Nonlinearity and Amplification in Cochlear Responses to Single and Multi-Tone Stimuli. Hear Res. 2019;377:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinomori Y, Jones D d., Spack DS, Kimura RS. Volumetric and Dimensional Analysis of the Guinea Pig Inner Ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110(1):91–98. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofman R, Segenhout JM, Albers FWJ, Wit HP. The relationship of the round window membrane to the cochlear aqueduct shown in three-dimensional imaging. Hear Res. 2005;209(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciuman RR. Communication routes between intracranial spaces and inner ear: function, pathophysiologic importance and relations with inner ear diseases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(3):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moussi K, Bukhamsin A, Hidalgo T, Kosel J. Biocompatible 3D Printed Microneedles for Transdermal, Intradermal, and Percutaneous Applications. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(2):1901358. doi: 10.1002/adem.201901358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aksit A, Rastogi S, Nadal ML, et al. Drug delivery device for the inner ear: ultra-sharp fully metallic microneedles. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021;11(1):214–226. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00782-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bremer HG, van Rooy I, Pullens B, et al. Intratympanic gentamicin treatment for Ménière’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on dose efficacy - results of a prematurely ended study. Trials. 2014;15:328. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauch SD, Halpin CF, Antonelli PJ, et al. Oral vs Intratympanic Corticosteroid Therapy for Idiopathic Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2011;305(20):2071–2079. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybak LP, Mukherjea D, Jajoo S, Kaur T, Ramkumar V. siRNA-mediated knock-down of NOX3: therapy for hearing loss? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(14):2429–2434. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1016-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rousset F, Carnesecchi S, Senn P, Krause KH. NOX3-TARGETED THERAPIES FOR INNER EAR PATHOLOGIES. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(41):5977–5987. doi: 10.2174/1381612821666151029112421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landegger LD, Pan B, Askew C, et al. A synthetic AAV vector enables safe and efficient gene transfer to the mammalian inner ear. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(3):280–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan F, Chu C, Qi J, et al. AAV-ie enables safe and efficient gene transfer to inner ear cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3733. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11687-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Surgical view of the right tympanic bulla under dissecting microscope, 25x magnification. RWM: round window membrane. VII: facial nerve. ISJ: incudostapedial joint. TM: tympanic membrane annulus. BT: basal turn of cochlea. BM: basilar membrane. A 1 mm scale bar is displayed for reference.