Abstract

This meta-analysis examined the associations between five-factor personality model traits and problem gambling. To be eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies had to provide effect size data that quantified the magnitude of the association between all five personality traits and problem gambling. Studies also had to use psychometrically sound measures. The meta-analysis included 20 separate samples from 19 studies and 32,222 total participants. The results showed that problem gambling was significantly correlated with the five-factor model of personality. The strongest personality correlate of problem gambling was neuroticism r = .31, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [0.17, 0.44], followed by conscientiousness r = − .28, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.38,-0.17] ), agreeableness r = − .22, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.34, − 0.10], openness r = − .17, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.22,-0.12], and extraversion r = − .11, p = .024, 95% CI [-0.20,-0.01]. These results suggest problem gamblers tend to share a common personality profile – one that could provide clues as to the most effective ways to prevent and to treat problem gambling.

The Association between the five-factor model of personality and Problem Gambling: a Meta-analysis

Problem gambling, also termed gambling disorder and pathological gambling, is a behavioral addiction characterized by persistent gambling behavior despite significant negative consequences that can include financial hardship, legal problems, relationship and occupational dysfunction, and significant emotional distress (Blanco & Bernadi, 2014); Brunborg et al., 2016). The diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders − 5 (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) includes additional elements, such as restlessness or irritability when reducing or attempting to stop gambling, a preoccupation with gambling, and a tendency for gambling to occur when feeling distressed.

Problem gambling is associated with stress, depression and anxiety, feelings of shame and worthlessness (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2010), along with suicide ideation and attempts (Gray et al., 2021; Wardle & McManus, 2021).

Problem gambling is not rare. Worldwide prevalence is estimated to range from 0.5 to 7.6% (Williams et al., 2012). A recent analysis estimated the societal costs of problem gambling in Sweden alone to be about $2 billion (Hofmarcher et al., 1921).

Researchers have considered various factors that might contribute to problem gambling pathogenesis and have suggested a multi-factorial model consisting of biopsychosocial factors (Shaffer et al., 2004). Researchers view personality as playing an influential role in the development, manifestation, severity, and maintenance of gambling disorder (Bagby et al., 2007; Mackinnon et al., 2016; Takada & Yukawa, 2019).

Personality traits are enduring characteristics that are consistent and stable across time and situation (Gregory, 2011). Personality is immensely complex. The most prominent and psychometrically supported model of personality in psychology is Costa and McCrae’s (1997) five-factor model of personality (Baranczuk, 2019). According to the five-factor model of personality, there are five broad personality domains that can describe between-person differences in human personality: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (McCrae & Costa, 1997). Openness is the tendency to be imaginative, curious, and have an open-mind; conscientiousness is the tendency to be well organized, goal oriented, and self-disciplined; extraversion is the tendency to be assertive, energetic, and sociable; agreeableness is the tendency to be affectionate, cooperative, helpful, and trusting; neuroticism is the tendency to feel anxious, irritable, depressed, and insecure (Mackinnon et al., 2016; Shum et al., 2013).

In studies examining the five-factor model and problem gambling, researchers have used various psychometric instruments to assess problem gambling. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987), which measures the severity of disordered gambling behaviors, consists of 20 items including: (1) Did you ever gamble more than you intended to? and (2) When you gamble, how often do you go back another day to win back money you have lost? A score of five or more indicates probable problem gambling. The 9-item Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris & Wynne, 2001) assesses behaviors and consequences associated with problem gambling. Responses are based on the frequency of the behaviors. Items include: (1) Have you borrowed money or sold anything to gamble? and (2) Has gambling caused you any health problems, including stress or anxiety?

In these studies, researchers have used various instruments that measure the five-factor model of personality. The NEO (Costa & McCrae, 1992) set of personality inventories consists of items that measure all five traits. Other standardized psychometric instruments that measure the five-factor model of personality include the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John et al., 1991), the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling, et al., 2003), and the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg et al., 2006).

Some studies have found a common personality profile of problem gamblers (Mann et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2013; Quilty et al., 2021). However, not all studies have replicated these findings; for example, some studies have found that gambling disorder is associated with high neuroticism but not with the other five-factor domains (MacLaren et al., 2015; Kaare et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2012).

Prior meta-analyses have examined the relationship between the five-factor model of personality and various types of psychological problems, including symptoms of clinical disorders of various types (Malouff et al., 2005), smoking (Malouff et al., 2006), excessive drinking (Malouff et al., 2007), and the dramatic and emotional cluster (cluster B) of personality disorders (Samuel & Widiger, 2008). In each meta-analysis, there were significant associations between multiple five-factor traits and the psychological problem. For instance, Malouff et al. (2005) found that all of the five-factor traits except openness were related to symptoms of clinical disorders. Samuel and Widiger found significant associations between all of the five traits except openness and multiple personality disorders.

The relationship between personality and problem gambling is not yet clear. Where the overall pattern of findings among related studies is not clear, a meta-analysis can be useful, so we set out to complete a meta-analysis of the association between the five-factor model of personality and problem gambling. We focused on studies using the five-factor model because we wanted to use an empirically supported model and because studies using the model provide an opportunity to assess each five-factor trait against the others in the same sample of participants. Because there have been numerous studies of the five-factor model and problem gambling, it is clear that researchers consider the relationship important. What is missing is an aggregation of the findings in a meta-analysis.

Aims of the meta-analysis

The purpose of the present meta-analysis was to examine the association between the five-factor model of personality and problem gambling. We hypothesized that high neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and low agreeableness would be associated with problem gambling, because these personality traits have been found to be associated with other types of addictive behavior involving alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and Internet gaming (Dash & Slutske, 2019; Malouff et al., 2005; Müller et al., 2014).

Method

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to meet three criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis: (1) The related report had to include effect sizes for the association between each of the five-factor personality traits and problem gambling, (2) the report had to state the number of participants, and (3) the study had to use psychometrically sound measures.

Search strategy

A protocol for this meta-analysis was published in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number: CRD42021237773, in February 2021. In March 2021, two researchers systematically searched the following databases: EBSCO, EBSCO Open Dissertations, Google Scholar, ProQuest, and PubMed. Keywords used were five factor or big five, and gambl*. No date or language parameters were set for the electronic search. To reduce the search results in the Proquest database from 6283 to 112, we added quotation marks to the search terms “five-factor” and “big 5.” In August 2021, we repeated the electronic database search and included a date parameter set to 2021–2022 to find any recently published studies. We also examined reference lists of included articles and emailed corresponding authors of included studies requesting unpublished data. No unpublished studies were found.

Data extraction and coding

One researcher manually extracted data from the included studies and recorded it on an electronic spreadsheet. Data extracted to calculate the effect sizes included correlations, and independent group means and standard deviations of problem gambling and healthy control groups. Coded descriptive data included: (1) study authors and publication date, (2) number of participants, (3) mean age, (4) percentage female, (5) five-factor model of personality measure used, (6) problem gambling measure used, (7) study design (correlational or between groups), (8) evidence of validity and reliability of the measures used, and (8) sample type. Then a second researcher checked data entries, and a third researcher independently coded entries needed to calculate effect sizes. Inter-rater reliability between the first two coders and the independent coder was 93%. Consensus between coders resolved all disagreements.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (CMA Version 3.3.070; Borenstein et al., 2014). A composite score was computed for studies reporting multiple outcomes for a single trait based on the same participants. Effect sizes were calculated using a meta-analysis analogue of Pearson’s r. For the 13 studies that reported means and standard deviations for groups of problem gamblers and others, Hedge’s g (Hedges, 1982) was calculated and then converted to r.

We used a random-effects model because it recognizes within-study and between-study variance and assumes that the true effect size differs among studies (Borenstein et al., 2009). To measure heterogeneity, both the I² statistic and Cochran’s Q were calculated. The I2 statistic quantifies the level of heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2003). I2 is the proportion of variance across studies that is due to true effects rather than sampling error. The Cochran’s Q statistic was computed to examine whether all studies in the present meta-analysis assessed the same effect (Higgins et al., 2003).

Quality assessment

Assessment of study quality involved evaluating the validity and reliability of all measures used in studies included in this meta-analysis.

Results

Study selection

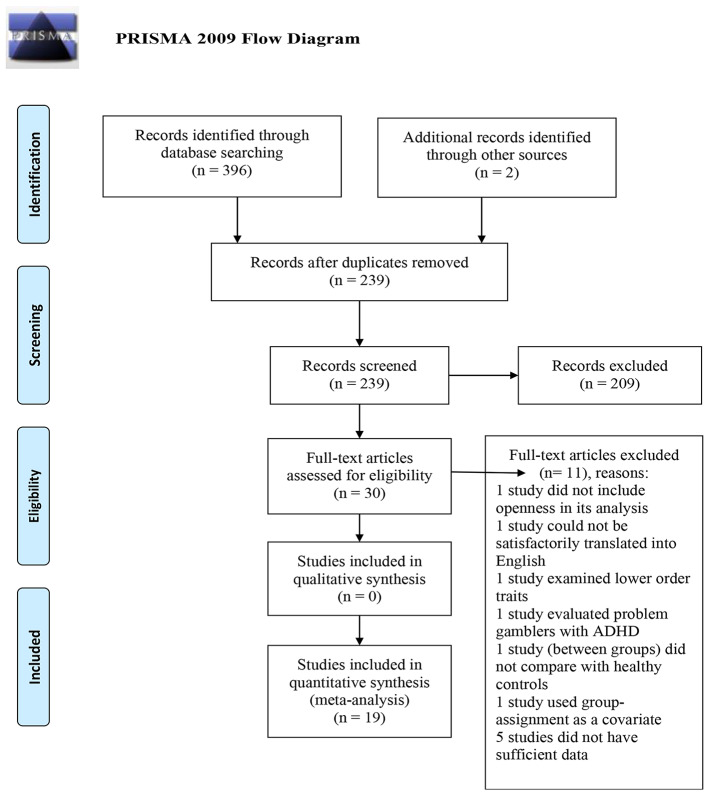

Following the removal of 159 duplicates, 239 records were retained for screening. Of the 239 records, 20 studies seemed to meet the inclusion criteria. Out of these 20 studies, one was removed because group-assignment in a treatment study was treated as a covariate in the key reported results. Hence, 19 studies were included in the meta-analysis. One study had two independent samples, leading to a total of 20 samples to analyze. Figure 1 presents a PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al., 2009) containing information about the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows key study characteristics. The meta-analysis included 20 samples, with a total of 32,222 participants and produced 100 effect sizes (20 effect sizes for each of the five personality factors). The most common problem gambling scale used was the SOGS, and 12 studies used a version of the NEO to measure the five-factor model of personality. The data file is at https://rune.une.edu.au/web/handle/1959.11/31788.

Table 1.

Descriptive information about studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Country | N | % Female | Problem gambling measure | FFM of personality measure | Study design | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bagby et al., 2007 | Canada | 283 | 52 | SDA DSM-IV | NEO PI-R | M | Community |

| Brunborg et al., 2016 | Norway | 9111 | 52 | PGSI | Mini-IPIP | M | Community |

| Buckle et al., 2013 | Canada | 212 | 71 | SOGS | NEO FFI | r | Convenience |

| Carlotta et al., 2015 | Italy | 110 | 49 | Lie Bet | BFI | M | Community |

| Cerasa et al., 2018 | Italy | 200 | 7 | SOGS | NEO PI-R | r | In treatment for gambling |

| Crossman, 2007 | USA | 206 | 53 | CPGI | IPIP-NEO-PI | M | University students |

| Dash et al., 2019 | Australia, USA | 3785 | 64 | NODS | NEO PI-R | r | Australian Twin Registry |

| Gong & Zhu, 2019 | Australia | 4100 | 49 | CPGI | HILDA Big-Five | M | Representative |

| Hwang et al., 2012 | Korea | 48 | 0 | SOGS | NEO PI-R | M | Clinical & community |

| Kaare et al., 2009 | Estonia | 69 | 11 | SOGS | EPIP- NEO | M | Clinical & community |

| Mann et al., 2017 | Germany | 113 | 0 | SOGS | NEO FFI | M | Clinical & community |

| Miller et al., 2013 | USA | 354 | 22 | SCI-PG | BFI | r | Frequent gamblers |

| Müller et al., 2014 | Germany | 215 | 0 | BIG | NEO FFI | M | Clinical & community |

| Myrseth et al., 2009 | Norway | 156 | 27 | SOGS | NEO FFI | M | Diagnosed & community |

| Quilty et al., 2021 | Canada | 134 | 50 | CPGI, SOGS | NEO PI-R, SIFFM | M | Diagnosed & community |

| Tabri et al., 2017 | Canada, USA | 197 | 44 | PGSI | TIPI | r | Community |

| Von der Heiden & Egloff, 2021 | Germany | 12,556 | 54 | PGSI | 36-item Big Five | r | Community HILDA |

| Whiting et al., 2019 | USA | 248 | 35 | SOGS | NEO PI-R | M | Community |

| Zilberman et al., 2018 | Israel | 125 | 46 | SOGS | BFI | M | Community problem gamblers |

Note. N = sample size; % female = percentage of females in sample; M = comparison of between group means; r = correlation design. Abbreviations: SDA DSM-IV Structured diagnostic assessment DSM-IV; CPGI, Canadian Problem Gambling Index; NODS, The National Opinion Research Center DSM Screen for Gambling Problems; SCI-PG, structured clinical interview for pathological gambling; BIG, Berlin Inventory of Gambling Behavior; NEO PI-R, NEO Personality Inventory-Revised; Mini IPIP, International Personality Item Pool; NEO FFI, NEO Five-Factor Inventory; EPIP NEO, Estonian Personality Item Pool- NEO; and SIFFM, Structured Interview for the Five-Factor Model of Personality

Quality Assessment

All measures used in studies included in the present meta-analysis demonstrated reliability (see Table 2). All measures used in the present meta-analysis also had evidence of validity.

Table 2.

Reliability of measures used in the meta-analysis

| Measure | Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) |

|---|---|

| BIG | a = 0.96 (Wejbera et al., 2017) |

| CPGI | a = 0.92 (Arthur et al., 2008); a = 0.89 (Back et al., 2015) |

| Lie Bet | α = 0.60 (Wieczorek et al., 2021) |

| NODS | a = 0.84 (Back et al., 2015); a = 0.86 (Wulfert et al., 2005); a = 0.79 (Hodgins, 2004) |

| PGSI |

a = 0.90 (Orford et al., 2010); a = 0.90 (Brunborg et al., 2016); a = 0.84 (Ferris & Wynne, 2001) α = 0.84 ((Wieczorek et al., 2021) |

| SCI-PG | a = 0.73 (Walker et al., 2006) |

| SDA DSM-IV | a = 0.92 (Stinchfield et al., 2005) |

| SOGS |

a = 0.86 (gambling treatment), a = 0.69 (community) (Stinchfield, 2002) a = 0.83 (Arthur et al., 2008); a = 0.85 (Wulfert et al., 2005); a = 0.78 (Hodgins, 2004) |

| BFI | a = 0.72 − 0.81 (Carlotta et al., 2015); a = 0.73 − 0.82 (Miller et al., 2013) |

| EPIP NEO | a = 0.89 − 0.95 (Mõttus et al., 2006) |

| IPIP NEO PI | a = 0.87 − 0.94 (Sleep et al., 2021); a = 0.91 − 0.94 (Maples-Keller et al., 2019) |

| MINI IPIP | a = 0.67 − 0.78 (Brunborg et al., 2016); a = 0.82 − 0.87 (Sleep et al., 2021) |

| NEO FFI |

a = 0.66 − 0.90 (Myrseth et al., 2009); a = 0.67 − 0.81 (Miller et al., 2013) a = 0.76 − 0.85 (Maples-Keller et al., 2019) |

| NEO PI-R | a = 0.83 − 0.90 (Mõttus et al., 2006); a = 0.90 − 0.93 (Maples-Keller et al., 2019) |

| SIFFM | a = 0.72 − 0.89 (Trull et al., 1998) |

| HILDA Big-Five | a = 0.74-0.81 (Losoncz, 2009) |

| TIPI | a = 0.52 − 0.70 (Ehrhart et al., 2009); a = 0.51 − 0.83 (Sleep et al., 2021) |

| 36-item Big Five | a = 0.66 − 0.79 (Wortman et al., 2012; Lucas & Donnellan, 2009) |

Studies showed concurrent validity across six of the problem gambling measures: CPGI and SOGS (r = .83, Stevens & Young, 2008); NODS and SOGS (r = .71, Wulfert et al., 2005); SCI-PG and SOGS (r = .78, Grant et al., 2004); PGSI and SOGS (r = .83, Ferris & Wynne, 2001); PGSI and DSM-IV criteria for gambling disorder (r = .82, Orford, 2010); and SOGS and DSM-IV criteria for gambling disorder (r = .66, Goodie et al., 2013; r = .72 Tang et al., 2010). Sensitivity and specificity of the Lie Bet questionnaire was 92% and 96%, respectively (Götestam et al., 2004), and Grant et al. reported 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the SCI-PG (2004). Wejbera et al. reported discriminant validity of the BIG (2017). Lastly, the structured diagnostic assessment demonstrated convergent validity with the SOGS (r = .59, Beaudoin & Cox, 1999; r = .81, Cox et al., 2004).

Studies demonstrated evidence of convergent validity across all eight five-factor model of personality measures: BFI and NEO PI-R (mean r = .78, Rammstedt & John, 2007); EPIP NEO and NEO PI-R (r = .73, Kaare et al., 2009); IPIP NEO PI and NEO FFI (mean r = .80, Maples-Keller et al., 2019); NEO PI-R and SIFFM (r = .65 − .84, Trull et al., 1998); SDA DSM-IV and SOGS (r = .90, Stinchfield et al., 2005); and TIPI and BFI (r = .65 − .87, Gosling et al., 2003). Further, the Saucier (1994) scale showed convergent validity with the 36-item Big Five and Goldberg’s (1992) five-factor model of personality adjectives (1994). The MINI IPIP exhibited criterion validity (Baldasaro et al., 2013), and a factor analysis supports construct validity of the HILDA Big-Five measure (Losoncz, 2009).

Main results

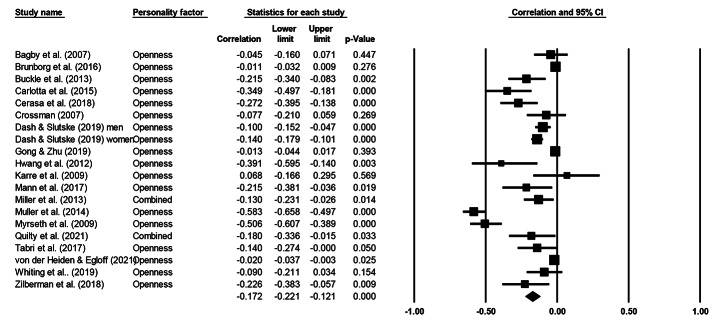

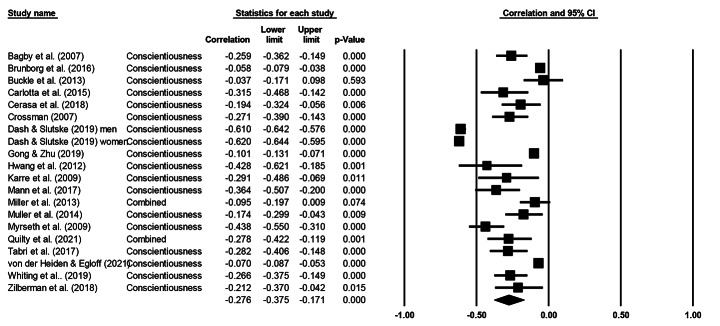

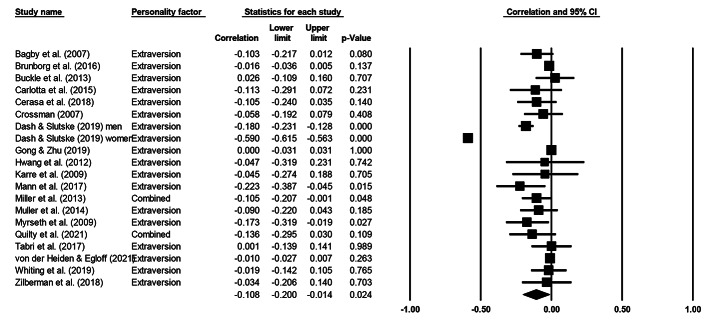

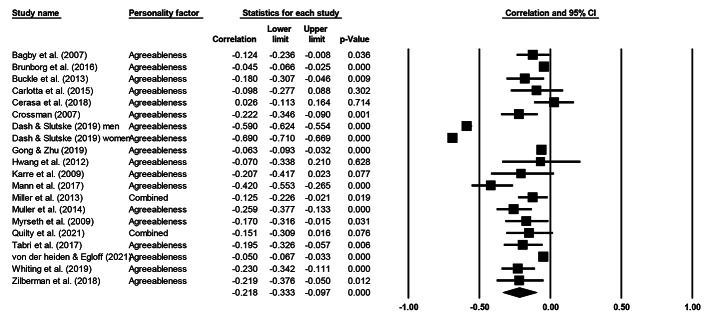

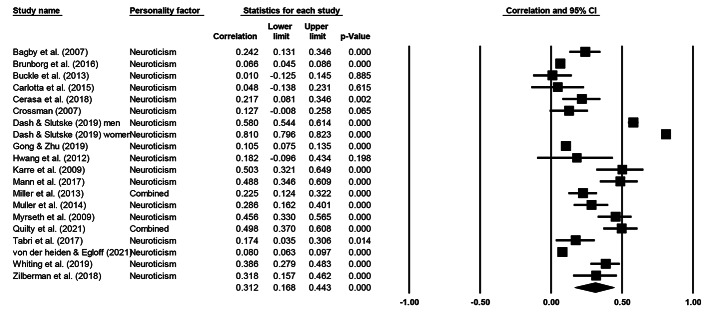

Neuroticism had a moderate positive relationship with problem gambling r = .31, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.44]. Conscientiousness showed a small negative correlation with problem gambling, r = − .28, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.37,-0.17]. Similarly, agreeableness (r = − .22, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.34, − 0.10]), openness (r = − .17, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.22,-0.12]), and extraversion (r = − .10, p = .047, 95% CI[-0.19,-0.00]) all showed small negative correlations with problem gambling. Neuroticism and conscientiousness accounted for 9.6% and 7.8% of the variance in problem gambling scores, respectively. Agreeableness, openness, and extraversion explained 4.8%, 2.9%, and 1.2% of variance in problem gambling scores, respectively.

Cochran’s Q statistic was significant across all five personality factors, indicating heterogeneity and supporting the use of a random effects model. Table 3 presents meta-analytical summary statistics for the association between the five-factor model of personality and gambling for all 20 samples. Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 illustrate the analyses of each individual personality factor and its association with problem gambling for the 20 samples included in the meta-analysis.

Table 3.

Summary statistics for the meta-analysis of the association between pathological gambling and the five-factor model of personality

| Analysis | N | Openness | Conscientiousness | Extraversion | Agreeableness | Neuroticism | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(95% CI) | p | r(95% CI) | p | r(95% CI) | p | r(95% CI) | p | r(95% CI) | p | ||

| Bagby et al., 2007 | 283 | − 0.05(-0.16,0.07) | 0.447 | − 0.26(-0.36,-0.15) | < 0.001 | − 0.10(-0.22,0.01) | 0.080 | − 0.12(-0.24,-0.01) | 0.036 | 0.24(0.13,0.35) | < 0.001 |

| Brunborg et al., 2016 | 9111 | − 0.01(-0.03,0.01) | 0.276 | − 0.06(-0.08,-0.04) | < 0.001 | − 0.02(-0.04,0.00) | 0.137 | − 0.05(-0.07,-0.02) | 0.000 | 0.07(0.05,0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Buckle et al., 2013a | 212 | − 0.22(-0.34,-0.08) | 0.002 | − 0.04(-0.17,0.10) | 0.593 | 0.03(-0.11,0.16) | 0.707 | − 0.18(-0.31,-0.05) | 0.009 | 0.01(-0.12,0.14) | 0.885 |

| Carlotta et al., 2015 | 110 | − 0.35(-0.50,-0.18) | < 0.001 | − 0.31(-0.47,-0.14) | 0.000 | − 0.11(-0.29,0.07) | 0.231 | − 0.10(-0.28,0.09) | 0.302 | 0.05(-0.14,0.23) | 0.615 |

| Cerasa et al., 2018 | 200 | − 0.27(-0.40,-0.14) | < 0.001 | − 0.19(-0.32,-0.06) | 0.006 | − 0.10(-0.24,0.03) | 0.140 | 0.03(-0.11,0.16) | 0.714 | 0.22(0.08,0.35) | 0.002 |

| Crossman, 2007 | 206 | − 0.08(-0.21,0.06) | 0.269 | − 0.27(-0.39,-0.14) | < 0.001 | − 0.06(-0.19,0.08) | 0.408 | − 0.22(-0.35,-0.09) | 0.001 | 0.13(-0.01,0.26) | 0.065 |

| Dash et al., 2019 menb | 1365 | − 0.10(-0.15,-0.05) | < 0.001 | − 0.61(-0.64,-0.58) | < 0.001 | − 0.18(-0.23,-0.13) | < 0.001 | − 0.59(-0.62,-0.55) | < 0.001 | 0.58(0.54,0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Dash et al., 2019 womenb | 2420 | − 0.14(-0.18,-0.10) | < 0.001 | − 0.62(-0.64,-0.59) | < 0.001 | − 0.59 (-0.62,-0.56) | < 0.001 | − 0.69(-0.71,-0.67) | < 0.001 | 0.81(0.80,0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Gong & Zhu, 2019 | 4100 | − 0.01(-0.04,0.02) | 0.393 | − 0.10(-0.13,-0.07) | < 0.001 | 0.00(-0.03,0.03) | 1.000 | − 0.06(-0.09,-0.03) | < 0.001 | 0.11(0.07,0.14) | < 0.001 |

| Hwang et al., 2012 | 48 | − 0.39(-0.59,-0.14) | 0.003 | − 0.43(-0.62,-0.19) | < 0.001 | − 0.05(-0.32,0.23) | 0.742 | − 0.07(-0.34,0.21) | 0.628 | 0.18(-0.10,0.43) | 0.198 |

| Kaare et al., 2009 | 69 | 0.07(-0.17,0.30) | 0.569 | − 0.29(-0.49,-0.07) | 0.011 | − 0.05(-0.27,0.19) | 0.705 | − 0.21(-0.42,0.02) | 0.077 | 0.50(0.32,0.65) | < 0.001 |

| Mann et al., 2017c | 113 | − 0.22(-0.38,-0.04) | 0.019 | − 0.36(-0.51,-0.20) | < 0.001 | − 0.22,(-0.39,-0.04) | 0.015 | − 0.42(-0.55,-0.26) | < 0.001 | 0.49(0.35,0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Miller et al., 2013 | 354 | − 0.13(-0.23,-0.03) | 0.014 | − 0.10(-0.20,0.01) | 0.074 | − 0.11(-0.21,0.00) | 0.048 | − 0.13(-0.23,-0.02) | 0.019 | 0.23(0.12,0.32) | < 0.001 |

| Müller et al., 2014 | 215 | − 0.58(-0.66,-0.50) | < 0.001 | − 0.17(-0.30,-0.04) | 0.009 | − 0.09(-0.22,0.04) | 0.185 | − 0.26(-0.38,-0.13) | 0.000 | 0.29(0.16,0.40) | < 0.001 |

| Myrseth et al., 2009 | 156 | − 0.51(-0.61,-0.39) | < 0.001 | − 0.44(-0.55,-0.31) | < 0.001 | − 0.17(-0.32,-0.02) | 0.027 | − 0.17(-0.32,-0.02) | 0.031 | 0.46(0.33,0.57) | < 0.001 |

| Quilty et al., 2021 | 134 | − 0.18(-0.34,-0.01) | 0.033 | − 0.28(-0.42,-0.12) | 0.001 | − 0.14(-0.30,0.03) | 0.109 | − 0.15(-0.31,0.02) | 0.076 | 0.50(0.37,0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Tabri et al., 2017 | 197 | − 0.14(-0.27,0.00) | 0.050 | − 0.28(-0.41,-0.15) | < 0.001 | 0.00(-0.14,0.14) | 0.989 | − 0.20(-0.33,-0.06) | 0.006 | 0.17(0.04,0.31) | 0.014 |

| Von der Heiden & Egloff, 2021 | 12,556 | − 0.02(-0.04,0.00) | 0.025 | − 0.07(-0.09,-0.05) | < 0.001 | − 0.01(-0.03,0.01) | 0.263 | − 0.05(-0.07,-0.03) | < 0.001 | 0.08(0.06,0.10) | < 0.001 |

| Whiting et al., 2019 | 248 | − 0.09(-0.21,0.03) | 0.154 | − 0.27(-0.38,-0.15) | < 0.001 | − 0.02(-0.14,0.11) | 0.765 | − 0.23(-0.34,-0.11) | < 0.001 | 0.39(0.28,0.48) | < 0.001 |

| Zilberman et al., 2018 | 125 | − 0.23(-0.38,-0.06) | 0.009 | − 0.21(-0.37,-0.04) | 0.015 | − 0.03(-0.21,0.14) | 0.703 | − 0.22(-0.38,-0.05) | 0.012 | 0.32(0.16,0.46) | < 0.001 |

Note. N = number of participants in sample

a In the study of Buckle et al. (2013) we used the square root of r squared as the effect size

b For the samples of Dash et al. (2019) we used the results for at least 4 symptoms, to match the standards of DSM-5

c We used the sub-sample of non-comorbid pathological gamblers found in Table 3 of the study of Mann et al. (2017)

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis on the association between openness and problem gambling

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis on the association between conscientiousness and problem gambling

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis on the association between extraversion and problem gambling

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis on the association between agreeableness and problem gambling

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis on the association between neuroticism and problem gambling

Synthesis of results

Table 4 shows the overall effect size for each personality factor, based on a total of 32,222 participants from 20 samples within 19 studies.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis summary: Random effects model statistics for the association between problem gambling and the five-factor model of personality

| Personality factor | N | Point estimate (CI 95%) | p-value | Heterogeneity analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | df | p | I-squared | ||||

| Openness | 20 | − 0.17(-0.22,-0.12) | < 0.001 | 248.18 | 19 | < 0.001 | 92.34 |

| Conscientiousness | 20 | − 0.28(-0.38,-0.17) | < 0.001 | 1443.36 | 19 | < 0.001 | 98.68 |

| Extraversion | 20 | − 0.11(-0.20,-0.01) | 0.02 | 1011.8 | 19 | < 0.001 | 98.12 |

| Agreeableness | 20 | − 0.22(-0.34,-0.10) | < 0.001 | 1840.20 | 19 | < 0.001 | 98.97 |

| Neuroticism | 20 | 0.31(0.17,0.44) | < 0.001 | 2835.68 | 19 | < 0.001 | 99.33 |

Note. N = number of observed samples

Publication bias

Funnel plots for all five personality traits show a symmetric distribution. Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill method did not suggest trimming any studies. These results suggest an absence of small-study effects. Table 5 shows the classic fail-safe N and Orwin’s fail-safe N analyses for each personality factor.

Table 5.

Fail-safe N analyses

| Personality factor | N | Classic fail-safe N | Orwin’s fail-safe N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | 20 | 957 | n/a |

| Conscientiousness | 20 | 4514 | 13 |

| Extraversion | 20 | 869 | n/a |

| Agreeableness | 20 | 3471 | 10 |

| Neuroticism | 20 | 6541 | 20 |

Note. N = number of observed samples; n/a = not applicable because the small correlation set as the standard for Orwin’s fail-safe (-0.10) exceeds correlation in observed studies

Discussion

The present meta-analysis provided a statistical review of the association between the five-factor model of personality and problem gambling. The findings from the 20 samples supported the hypothesis that gambling disorder was significantly associated with higher scores on neuroticism, and lower scores on conscientiousness and agreeableness. The results also showed problem gambling was significantly associated with lower scores on both openness and extraversion.

Cohen (1988) suggested that r be interpreted as a small effect when r = .10, a medium effect when r = .30, and a large effect when r = .50. The effect size for neuroticism, 0.31, was a medium effect, and the effect size for conscientiousness, − 0.28, was nearly medium. The other effect sizes were small.

Because the findings are correlational, they do not provide evidence that the traits cause problem gambling. However, the findings are consistent with possible causes of problem gambling. The implications of the findings vary from trait to trait, as described below.

Individuals scoring high on neuroticism tend to be worrisome, anxious, self-conscious, and depressed. Hence, some individuals may use gambling to escape these negative feelings, at least for a short while (Mackinnon et al., 2016).

Low conscientiousness involves apathy, impulsivity and a disregard of social norms. Impulsivity could play a factor in problem gambling by its focus on the extreme short-term over the longer term (Ioannidis et al., 2019).

Low agreeableness is characterized by a tendency to be unsocial, inconsiderate, and competitive. Disagreeable behavior may be an antecedent to relationship and occupational dysfunction, consequences that are characteristic of gambling disorder (Widinghoff et al., 2019). The competitive element of this trait could lead individuals to continue gambling despite losses (Parke et al., 2004).

Individuals low in openness tend to avoid change, to be closed-minded, and to prefer routine. The change-avoidant characteristic could contribute to persistent gambling by keeping a person repeating the behavior that is causing problems (Myrseth et al., 2009). The relationship between extraversion and problem gambling was the lowest in magnitude among the five personality factors. Low extraversion involves low engagement with others and is typically associated with maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (Baranczuk, 2019). Low extraversion could help keep some individuals gambling because of a perceived lack of other social sources of excitement, and because of low mood that can be briefly improved by the excitement of gambling.

The meta-analysis showed that all the five-factor personality traits are related to problem gambling in specific ways. However, those same, seemingly undesirable traits might have adaptive value in certain situations. For instance, low agreeableness might help a person avoid being swindled by a new romantic partner.

The personality characteristics associated with problem gambling tend to be associated with other addictive disorders, including alcohol, cannabis, and nicotine use disorders (Dash & Slutske, 2019; Malouff et al., 2005; Müller et al., 2014). Studies have shown that the same personality profile is associated with various psychological problems (Malouff et al., 2005) and with the dramatic and emotional cluster (cluster B) of personality disorders (Samuel & Widiger, 2008; Quilty et al., 2021). It is therefore not surprising that problem gamblers are highly comorbid with nicotine dependence, substance use disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders (Lorains et al., 2011), and cluster B personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder (Brown et al., 2015). It could be that personality factors help push a person toward addictive behavior.

The main limitations of the present meta-analysis are that the findings (a) are correlational, (b) are entirely based on self-report, (c) combine problems relating to various types of gambling, and (d) are based on mainly English-speaking participants. The correlational findings do not show the direction of the causal relationship between personality and problem gambling. Personality may cause problem gambling, problem gambling may lead to certain personality traits, the relationship may be bidirectional, or some third variable, such as specific genes, may lead to both certain personality traits and problem gambling. Self-report measures rely on a person’s insight and honesty, making them vulnerable to biases. Individuals problematically engaging in different types of gambling activities, e.g., betting on horse races and playing slot machines, may differ in important ways. Individuals who are problem gamblers in different cultures might show a different pattern of personality. It is unknown whether the findings of this meta-analysis could be generalised to every type of gambling and every culture.

The present meta-analysis has advantages over the results of any single study in that the meta-analysis included results from different sets of researchers examining individuals in different countries, used different measures, and analyzed a very large overall group of participants. Aggregating findings across many different studies helps increase the generalizability of findings.

If problem gambling results from attempts to reduce the negative affect of neuroticism, implementing treatment strategies that reduce negative affect may prove helpful in managing problem gambling. Clinicians could devise treatment plans to focus on identifying and implementing ways to improve an individual’s overall affective state. Additionally, clinicians may need to consider the possible influence of personality on treatment processes. The personality profile associated with gambling disorder, including low conscientiousness and low agreeableness, may make it challenging to successfully treat individuals for problem gambling. A person with the personality of low conscientiousness and low agreeableness may not consistently attend appointments or undertake therapeutic assignments. Clinicians may need to make special efforts to overcome these client tendencies. In this regard, Ramos-Grille et al. (2014) found problem gamblers with low scores on conscientiousness had higher rates of treatment failure and relapse.

Clinicians who help problem gamblers could consider personality-focused strategies that have shown success with other addictive disorders; for instance, the Preventure Programme delivers brief interventions targeting personality risk factors associated with substance abuse. The interventions include psychoeducation, motivational enhancement therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy (Edalati & Conrod, 2019).

Future research on personality and problem gambling could explore whether the findings of the meta-analysis apply to problems with specific types of gambling and apply in cultures not examined so far. Studies could examine whether personality-focused preventive efforts and treatments are effective. Studies could also examine whether different types of treatment for problem gambling change specific personality traits.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- *Asterisk indicates study was included in the meta-analysis.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, & Author (2013). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Australian Government Productivity Commission (2010). Gambling. Productivity commission inquiry report volume 1. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/gambling-2010/report/gambling-report-volume1.pdf

- Back KJ, Williams RJ, Lee CK. Reliability and validity of three instruments (DSM-IV, CPGI, and PPGM) in the assessment of problem gambling in South Korea. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015;31:775–786. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Vachon DD, Bulmash EL, Toneatto T, Quilty LC, Costa PT. Pathological gambling and the five-factor model of personality. Personality & Individual Differences. 2007;43(4):873–880. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baranczuk U. The five factor model of personality and emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;139:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin CM, Cox BJ. Characteristics of problem gambling in a Canadian context: A preliminary study using a DSM-IV-based questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;44(5):483–487. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, C., & Bernardi, S. (2014). Gambling Disorder. In Gabbard, G. O. (Ed), Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 10.1176/appi.books.9781585625048.gg62

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. West Sussex: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis version 3.3.07. Biostat

- Brown M, Allen JS, Dowling NA. The application of an etiological model of personality disorders to problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015;31(4):1179–1199. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunborg GS, Hanss D, Mentzoni RA, Molde H, Pallesen S. Problem gambling and the five-factor model of personality: a large population-based study. Addiction. 2016;111(8):1428–1435. doi: 10.1111/add.13388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle JL, Dwyer SC, Duffy J, Brown KL, Pickett ND. Personality factors associated with problem gambling behavior in university students. Journal of Gambling Issues. 2013;28:1–17. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2013.28.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlotta D, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Borroni S, Frera F, Somma A, Fossati A. Adaptive and Maladaptive Personality Traits in High-Risk Gamblers. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2015;29(3):378–392. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerasa A, Lofaro D, Cavedini P, Martino I, Bruni A, Sarica A, Quattrone A. Personality biomarkers of pathological gambling: A machine learning study [Article] Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2018;294:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Academic Press

- Cox BJ, Enns MW, Michaud V. Comparisons between the South Oaks Gambling Screen and a DSM-IV—based interview in a community survey of problem gambling. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;49(4):258–264. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Crossman, E. W. (2007). Gambling behavior and the Five factor model of personality (Publication Number 1443743). http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.une.edu.au/dissertations-theses/gambling-behavior-five-factor-model-personality/docview/304760022/se-2?accountid=17227

- Dash GF, Slutske WS, Martin NG, Statham DJ, Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Big Five personality traits and alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and gambling disorder comorbidity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2019;33(4):420–429. doi: 10.1037/adb0000468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edalati H, Conrod PJ. A review of personality-targeted interventions for prevention of substance misuse and related harm in community samples of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;9:770. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, M. G., Ehrhart, K. H., Roesch, S. C., Chung-Herrera, B., Nadler, K., & Bradshaw, K. (2009). Testing the latent factor structure and construct validity of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8) (2009), pp. 900–905, 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.012

- Ferris J, Wynne HJ. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index. Final report. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR, Gough HG. The international personality item pool and the future of public domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Zhu R. Cognitive abilities, non-cognitive skills, and gambling behaviors. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2019;165:51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2019.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodie A, MacKillop J, Miller J, Fortune E, Maples-Keller J, Lance C, Campbell WK. Evaluating the South Oaks Gambling Screen with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: Results from a diverse community sample of gamblers. Assessment. 2013;20(5):523–531. doi: 10.1177/1073191113500522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götestam KG, Johansson A, Wenzel HG, Simonsen IE. Validation of the Lie/Bet Screen for Pathological Gambling on two normal population data sets. Psychological Reports. 2004;95(3):1009–1013. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.3.1009-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality. 2003;37(6):504–528. doi: 10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Steinberg MA, Kim SW, Rounsaville BJ, Potenza MN. Preliminary validity and reliability testing of a structured clinical interview for pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research. 2004;128(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H. M., Edson, T. C., Nelson, S. E., Grossman, A. B., & LaPlante, D. A. (2021). Association between gambling and self-harm: a scoping review. Addiction Research & Theory, 29(3), 183–195. 10.1080/16066359.2020.1784881

- Gregory, R. J. (2011). Psychological testing: History, principles, and applications (6th ed.). Allyn & Bacon

- Hedges LV. Estimation of effect size from a series of independent experiments. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92(2):490–499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.92.2.490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC. Using the NORC DSM Screen for Gambling Problems as an outcome measure for pathological gambling: psychometric evaluation. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(8):1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmarcher, T., Romild, U., Spångberg, J., Persson, U., & Håkansson, A. (1921). The societal costs of problem gambling in Sweden. BMC Public Health, 20, 10.1186/s12889-020-10008-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hwang J, Shin YC, Lim SW, Park H, Shin N, Jang J, Kwon J. Multidimensional Comparison of Personality Characteristics of the Big Five Model, Impulsiveness, and Affect in Pathological Gambling and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2012;28(3):351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10899-011-9269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Hook R, Wickham K, Grant JE, Chamberlain SR. Impulsivity in gambling disorder and problem gambling: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(8):1354–1361. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0393-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). Big Five Inventory (BFI). APA PsycTests. 10.1037/t07550-000

- Kaare PR, Mõttus R, Konstabel K. Pathological gambling in Estonia: relationships with personality, self-esteem, emotional states and cognitive ability. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2009;25(3):377–390. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(9):1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorains FK, Cowlishaw S, Thomas SA. Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction. 2011;106(3):490–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losoncz I. Personality traits in HILDA: [Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia.] Australian Social Policy (Canberra, A.C.T.) 2009;8:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Age differences in personality: Evidence from a nationally representative Australian sample. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1353–1363. doi: 10.1037/a0013914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, S. P., Lambe, L., & Stewart, S. H. (2016). Relations of five-factor personality domains to gambling motives in emerging adult gamblers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Gambling Issues, 34. 10.4309/jgi.2016.34.10

- MacLaren V, Ellery M, Knoll T. Personality, gambling motives and cognitive distortions in electronic gambling machine players. Personality & Individual Differences. 2015;73:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Rooke SE, Schutte NS. Alcohol involvement and the five-factor model of personality: A meta-analysis. Journal of drug education. 2007;37(3):277–294. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The relationship between the five-factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27(2):101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, Schutte NS. The five-factor model of personality and smoking: A meta-analysis. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36(1):47–58. doi: 10.2190/9EP8-17P8-EKG7-66AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Lemenager T, Zois E, Hoffmann S, Nakovics H, Beutel M, Fauth-Bühler M. Comorbidity, family history and personality traits in pathological gamblers compared with healthy controls. European Psychiatry. 2017;42:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maples-Keller JL, Williamson RL, Sleep CE, Carter NT, Campbell WK, Miller JD. Using Item Response Theory to Develop a 60-Item Representation of the NEO PI-R Using the International Personality Item Pool: Development of the IPIP-NEO-60. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2019;101(1):4–15. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2017.1381968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality Trait Structure as a Human Universal. The American Psychologist. 1997;52(5):509–516. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, MacKillop J, Fortune EE, Maples J, Lance CE, Campbell K, Goodie AS. Personality correlates of pathological gambling derived from Big Three and Big Five personality models [Article] Psychiatry Research. 2013;206(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mõttus R, Pullmann H, Allik J. Toward More Readable Big Five Personality Inventories. European Journal of Psychological Assessment: Official Organ of the European Association of Psychological Assessment. 2006;22(3):149–157. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller KW, Beutel ME, Egloff B, Wölfling K. Investigating Risk Factors for Internet Gaming Disorder: A Comparison of Patients with Addictive Gaming, Pathological Gamblers and Healthy Controls regarding the Big Five Personality Traits. European Addiction Research. 2014;20(3):129–136. doi: 10.1159/000355832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrseth H, Pallesen S, Molde H, Johnsen BH, Lorvik IM. Personality factors as predictors of pathological gambling. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:933–937. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Wardle H, Griffiths M, Sproston K, Erens B. PGSI and DSM-IV in the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey: reliability, item response, factor structure and inter-scale agreement. International Gambling Studies. 2010;10(1):31–44. doi: 10.1080/14459790903567132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parke A, Griffiths M, Irwing P. Personality traits in pathological gambling: Sensation seeking, deferment of gratification and competitiveness as risk factors. Addiction Research & Theory. 2004;12(3):201–212. doi: 10.1080/1606635310001634500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quilty LC, Otis E, Haefner SA, Bagby RM. A multi-method investigation of normative and pathological personality across the spectrum of gambling involvement. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(1):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Grille I, Gomà-i-Freixanet M, Aragay N, Valero S, Vallès V. Predicting treatment failure in pathological gambling: The role of personality traits. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;43:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(8):1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucier G. Mini-Markers: A Brief Version of Goldberg’s Unipolar Big-Five Markers. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;63(3):506–516. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R., Donato, A., & Stanton, M. (2004). Toward a syndrome model of addiction: Multiple expressions, common etiology. Harvard review of psychiatry 12, 367 – 74. 10.1080/10673220490905705 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shum, D., O’Gorman, J., Creed, P., & Myors, B. (2013). Psychological testing and assessment (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press

- Sleep CE, Lynam DR, Miller JD. A Comparison of the validity of very brief measures of the big five/five-factor model of personality. Assessment. 2021;28(3):739–758. doi: 10.1177/1073191120939160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M, Young M. Gambling screens and problem gambling estimates: A parallel psychometric assessment of the South Oaks Gambling Screen and the Canadian Problem Gambling Index. Gambling Research: Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies (Australia) 2008;20(1):13–36. doi: 10.3316/informit.397453630931695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R. Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R, Govoni R, Frisch R. DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling: Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy. The American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14(1):73–82. doi: 10.1080/10550490590899871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabri N, Wohl MJA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Me, myself and money: Having a financially focused self-concept and its consequences for disordered gambling. International Gambling Studies. 2017;17(1):30–50. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2016.1252414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takada T, Yukawa S. Relationships between Gambling Disorder and the Big Five Personality Traits among Japanese Adults. Personality Research [Personality Kenkyu] 2019;28(3):260–262. doi: 10.2132/personality.28.3.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CS, Wu AMS, Tang JYC, Yan ECW. Reliability, Validity, and Cut Scores of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) for Chinese. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2010;26:145–158. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Useda JD, Holcomb J, Doan BT, Axelrod SR, Gershuny BS. A structured interview for the assessment of the five-factor model of personality. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(3):229–240. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.3.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von der Heiden JM, Egloff B. Associations of the Big Five and locus of control with problem gambling in a large Australian sample. PloS One. 2021;16(6):e0253046–e0253046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M, Anjoul F, Milton S, Shannon K. A Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling. Gambling Research Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies Australia. 2006;18(1):39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, H., & McManus, S. (2021). Suicidality and gambling among young adults in Great Britain: results from a cross-sectional online survey. The Lancet Public Health, 6(1), e39–e49. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, L., Biechowska, D., Dabrowska, K., & Sieroslawski, J. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Polish version of two screening tests for gambling disorders: the Problem Gambling Severity Index and Lie/Bet Questionnaire. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 1–14. 10.1080/13218719.2020.1821824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wejbera M, Müller KW, Becker J, Beutel ME. The Berlin Inventory of Gambling behavior – Screening (BIG-S): Validation using a clinical sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:188. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widinghoff C, Berge J, Wallinius M, Billstedt E, Hofvander B, Håkansson A. Gambling disorder in male violent offenders in the prison system: Psychiatric and substance-related comorbidity. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019;35(2):485–500. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9785-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. J., Volberg, R., A., & Stevens, R. M. (2012). The Population Prevalence of Problem Gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. http://hdl.handle.net/10133/3068

- Whiting SW, Hoff RA, Balodis IM, Potenza MN. An exploratory study of relationships among five-factor personality measures and forms of gambling in adults with and without probable pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019;35(3):915–928. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortman J, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB. Stability and change in the Big Five personality domains: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Australians. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27(4):867–874. doi: 10.1037/a0029322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfert E, Hartley J, Lee M, Wang N, Franco C, Sodano R. Gambling screens: Does shortening the time frame affect their psychometric properties? Journal of Gambling Studies. 2005;21:521–536. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-5561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman N, Yadid G, Efrati Y, Neumark Y, Rassovsky Y. Personality profiles of substance and behavioral addictions. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;82:07. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]