Abstract

A novel immunostimulating factor (ISTF) of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29522 was isolated and characterized as inducing proliferation of mouse B cells and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This factor was isolated from the bacterial culture medium and purified by size exclusion chromatography, dye-ligand affinity chromatography, immunoaffinity chromatography using monoclonal antibodies, and preparative electrophoresis. Analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed that the purified ISTF migrated as a single band corresponding to a molecular mass of 13 kDa. ISTF was a proteinaceous material distinct from lipopolysaccharide; it directly induced the proliferation of B lymphocytes but had no effect on the proliferation of T lymphocytes, even in the presence of antigen-presenting cells. A B-lymphocyte-mitogenic activity of ISTF was also shown by flow cytometric analysis of responding cell subpopulations. Immunoblot analysis revealed that ISTF was a component of the outer membranes of bacteria, could exist as a soluble form, and was released by growing and/or lysed bacteria. These results suggest that ISTF produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans may play an important role in immunopathologic changes associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans infections.

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a nonmotile, gram-negative coccobacillus, is associated with several human diseases including endocarditis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, subcutaneous abscesses, and periodontal diseases (2, 8, 20, 24, 30). Although the pathogenic mechanism of A. actinomycetemcomitans is not known, it has been proposed that the impairment of the host immune mechanism by the bacteria-producing virulence factors might contribute to the disease process. Many other studies have described several virulence factors of A. actinomycetemcomitans, which exhibited alterations in immune regulation. Immunosuppressive factor (ISF; 60 kDa) inhibited mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation and immunoglobulin (Ig) production (26, 27). Suppressive factor 1 (SF1; 14 kDa) downregulated T-cell proliferation and cytokine production (13). Leukotoxin (115 kDa) inhibited the responsiveness of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to mitogens and antigens by subverting monocytes (23). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) suppressed antigen- and mitogen-induced human T-cell proliferation by inducing the release of prostaglandin E2 from activated macrophages (5). As all these factors contributed to the suppression of lymphocyte activation, it has been suggested that products of A. actinomycetemcomitans might possess a lymphocyte-activating substance like a superantigen (1, 16, 17, 32). During studies in our laboratory focusing on an understanding of the immunomodulatory activity of the products from A. actinomycetemcomitans, we became intrigued by an indication that immunosuppressing and immunostimulating activities were present simultaneously in the bacterial preparations. A consistent pattern was observed: A. actinomycetemcomitans homogenates induced lymphocyte proliferation when relatively low concentrations were used but evoked suppression of lymphocytes at elevated levels (7). Over the past years, we have established that this bacterium released a proteinaceous lymphocyte-proliferating substance which is distinct from other known virulence factors.

In the present study we have tried to purify the immune-stimulating substance from A. actinomycetemcomitans by several column chromatographies and preparative gel electrophoresis, and we have undertaken some functional approaches. We found that the bacteria produce a novel 13-kDa immunostimulating factor (ISTF), other than LPS, which induces B-lymphocyte proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

BALB/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from the DaeHan laboratory animal research center, Seoul, Korea, and used at the age of 8 to 10 weeks.

Culture of bacteria.

A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29522 was cultured at 37°C in a CO2-enriched atmosphere (10%) using brain heart infusion broth. Cultures were checked visually and by Gram staining for contamination with other bacteria. After 48 h of growth, culture supernatants were separated from cell pellets by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Bacterial cell pellets were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and once in distilled water; then they were immediately stored at −70°C until use. Frozen cells were suspended in 50 mM Tris buffer (TB), pH 7.5, and disrupted with a Fisher 550 sonic dismembrator (10 min, 50% pulse mode, 40% power). Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The insoluble cell wall fractions were then separated from the supernatant containing the soluble fraction by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 20 min.

Partial purification of ISTF from bacterial-culture supernatants.

The 48-h bacterial-culture supernatants were concentrated by precipitation with 4 volumes of absolute alcohol (final concentration, 80%) at −20°C. The precipitate was dissolved in water and dialyzed against PBS. The dialyzed sample was processed on a Sephacryl S-200 column (16 by 100 mm; Pharmacia) equilibrated with PBS. The fractions were assayed for lymphocyte-proliferating activity as described below. The biologically active fraction was further fractionated by Reactive Yellow 3-agarose affinity chromatography (Sigma). The column was equilibrated with 0.01 M TB (pH 8.0), washed with 6 to 8 column volumes of equilibration buffer, and eluted with a stepwise gradient of 0 to 1.5 M NaCl in 0.01 M TB. Fractions which induced lymphocyte proliferation were pooled, dialyzed against distilled water, and concentrated by lyophilization.

Preparation of monoclonal antibodies against ISTF.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg of partially purified ISTF protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma). The mice were boosted intraperitoneally with 50 μg of protein emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant three times at two-week intervals. Three days prior to removal of the spleens, the same amount of the protein suspended in PBS was injected intravenously into the mice. Splenocytes from the immunized mice were fused with cells of the mouse myeloma cell line SP2/0-Ag14. Hybridoma cell culture supernatants were screened against ISTF by a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Costar). Bound antibody was detected with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (Sigma) and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma). Positive clones were recloned by limiting dilution and were screened for immunoreactivity and blocking activity against ISTF by Western blotting and lymphocyte proliferation assay. The class and subclass of each monoclonal antibody was determined by use of a mouse monoclonal subisotyping kit (Sigma). The selected hybridoma was injected into BALB/c mice for growth as ascites, and monoclonal antibodies were purified by Hitrap protein A-agarose affinity chromatography (Pharmacia). Two individual monoclonal antibodies were used in this study.

Immunoblot analysis.

The bacterial-culture supernatants and various fractions of sonic extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The unoccupied binding sites on the membranes were blocked by incubation in TBS-T (20 mM Tris base, 137 mM NaCl [pH 7.6], 0.5% Tween 20) containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with predetermined dilutions of each monoclonal antibody for 3 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed and treated with 1:5,000 diluted rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 1 h. After a wash, the bound antibodies were visualized with the ECL detection system (Amersham).

Immunoaffinity chromatography.

The starting material was applied sequentially to a precolumn and affinity column series. All columns were prepared by coupling 3 ml of CNBr-activated Sepharose with 9 mg of purified protein. The first column was a bovine serum albumin-Sepharose column. Material not bound by the precolumn was then applied to a monoclonal antibody column. The column was washed with PBS, and the bound material was eluted with 0.1 M phosphoric acid, pH 12.5. The eluted material was neutralized with 1/20 volume of 1 M sodium phosphate, pH 6.8, dialyzed against 1 mM Tris-Cl, and then concentrated with a Centriprep concentrator (Amicon).

Preparative electrophoresis.

The purified material from affinity chromatography was further isolated by both native PAGE and SDS-PAGE using a model 491 Prep Cell (Bio-Rad). Samples were mixed either with SDS-reducing buffer or with the same buffer without SDS for the native separation. For the SDS-PAGE, the sample preparation was incubated at 37°C for at least 30 min prior to loading onto the stacking gel and was then loaded onto a 30-ml, 16.5% resolving gel with a 15-ml, 4% stacking gel polymerized in the gel tube (inner diameter [i.d.], 37 mm). Electrophoresis was performed using 0.1 M Tris–0.1 M Tricine–0.1% (wt/vol) SDS (pH 8.25) in the cathode chamber, 0.2 M Tris (pH 8.9) in the anode buffer, and an elution buffer of 1 mM Tris (pH 7.0), and the sample was run at maximum settings of 12 W and 50 mA. For the native separation, the sample was loaded onto a 20-ml, 15% resolving gel with a 5-ml, 4% stacking gel in the gel tube (i.d., 28 mm) and was run at 10 W and 45 mA, by using 50 mM Tris–0.4 M glycine (pH 10.5) in the cathode chamber, 25 mM Tris–0.14 M glycine (pH 6.8) in the anode buffer, and an elution buffer of 1 mM Tris (pH 7.0). Fractions (volume, 6 ml) were collected by using a peristaltic pump set at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Eluted material was continuously monitored for protein content with a UV detector set at 280 nm. Fractions were concentrated by lyophilization, and the protein concentrations were determined after desalting by using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent and albumin standard. The purity and bioactivity of each fraction were analyzed by analytical SDS-PAGE and lymphocyte proliferation assay.

Analytical gel electrophoresis.

The analytical gels consisted of 1-mm-thick 4% stacking gels and 12 or 16.5% separating gels run in a Mini-Protean II system (Bio-Rad) and stained with colloidal Coomassie blue (Sigma) or silver stain reagents (Bio-Rad).

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

Spleens were aseptically removed, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by gently teasing the cells through a sterile stainless steel screen. Erythrocytes were lysed with a NH4Cl solution. A T-cell-enriched fraction was obtained by using a nylon wool column. Splenocytes were added and incubated for 45 min in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator without drying the column. The column was filled and eluted with 37°C RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco). The first 15 ml of the effluent cell suspensions exhibited the best T-cell enrichment. For T-cell depletion, splenocytes were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with a monoclonal antibody to mouse Thy-1.2 (HO-13-4). Cells were centrifuged to remove any unbound antibody and were incubated at 37°C for 45 min in the presence of Low-Tox-M rabbit complement (Cedarlane). The remaining cells were washed, resuspended, and applied to a Sephadex G-10 column (Pharmacia). The first effluent cells were used as a B-cell-enriched fraction. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) were isolated from splenocytes by adherence to 100-mm tissue culture dishes. Adherent cells were recovered by vigorous pipetting following EDTA treatment and were resuspended in tissue culture medium containing 5 μg of mitomycin C (Sigma)/ml to block cellular division, leaving antigen-presenting function. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the cells were washed completely and used as APCs. Human PBMC were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma) density gradient centrifugation. The cells at the interface of the gradient were collected, washed three times to remove the platelets, and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium. Cells were counted in a hemocytometer and prepared at the appropriate concentration of viable cells per milliliter. For assessment of proliferating responses, single cells were suspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml) and dispensed into 96-well flat-bottom microculture plates. After the specified incubation period in a 37°C humidified environment containing 5% CO2, cells were pulsed with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham) during the last 6 h of incubation. Cells were then harvested onto glass fiber filters with an automatic cell harvester (Skatron). The filters were dried, placed in vials with scintillation fluid, and analyzed with a β scintillation counter (Beckman). To determine the subpopulation of proliferating cells, we analyzed the expression of surface molecules. Splenocytes were cultured for 3 days or 2 weeks with or without 2 U of interleukin-2 (IL-2)/ml. After incubation, the cells were resuspended at 4°C in staining buffer (PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide) at 2 × 107 cells/ml, and 50-μl cell suspensions were stained with appropriately diluted labeled antibodies (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]-conjugated anti-CD3ɛ, anti-CD4 (L3T4), anti-CD8a (Ly-2), or anti-CD45R/B220; Pharmingen) for 20 min in an ice bath. The cells were washed twice and resuspended in staining buffer at 4°C. A propidium iodide (PI) solution (50 μg of PI/ml–0.1% [vol/vol] sodium citrate) was added to the cell suspension in order to detect dead cells prior to analysis. The stained cells were analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACScan/Lysis II system by single-color (FITC) analysis with simultaneous live/dead discrimination using PI. Gates were set both by forward and side scatter for lymphocytes and by FL2 for exclusion of dead cells.

RESULTS

Purification of ISTF.

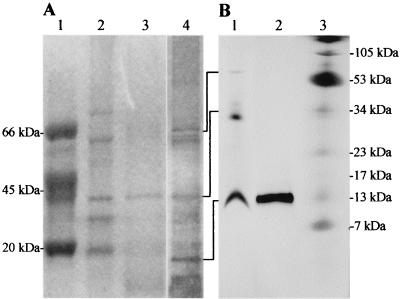

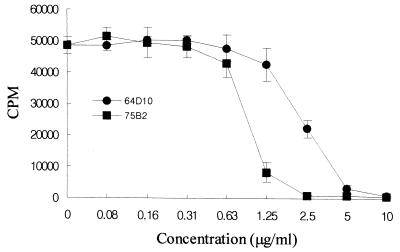

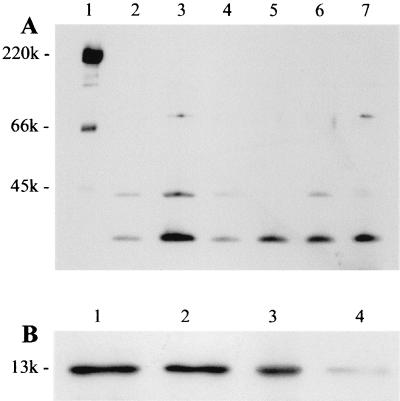

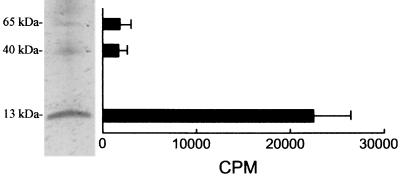

At first, we saw the immunostimulating activity with the alcohol-precipitated culture supernatant of A. actinomycetemcomitans. The concentrated culture supernatant was chromatographed on a Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration column, and fractions which induced lymphocyte-proliferating activity were eluted over a broad range (data not shown). These factions were pooled, concentrated, and further fractionated by several kinds of column chromatography. However, we failed to purify ISTF using Mono Q and Resource Q fast protein liquid chromatography columns. As we made an alternative plan to set up an immunoaffinity chromatography system for the preparation of highly purified ISTF, we tried by a further fractionation step using dye-ligand affinity chromatography to obtain a considerable amount of partially purified ISTF-containing material for use as an antigen for the production of monoclonal antibody. We obtained the best result by using the Reactive Yellow-3 dye affinity column. ISTF was eluted from the column as a small peak during the 0.1 M NaCl wash. Each fractionation step was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel, and bands were stained with Coomassie blue and silver stain reagents. The partially purified material showed three main bands with molecular masses of >60, ∼40, and <20 kDa (Fig. 1A). This material was used for the production of monoclonal antibodies against ISTF. During single-cell cloning, two monoclones designated 64D10 and 75B2 were obtained. The subtypes of monoclonal antibodies 64D10 and 75B2 were IgG1 and IgG2a, respectively. These two antibodies had similar immunoreactivities and neutralizing effects with regard to the partially purified ISTF. The affinity-purified monoclonal antibodies 64D10 and 756B2 completely blocked lymphocyte-proliferating activity at 5 and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). The immunoreactivities of monoclonal antibodies revealed the existence of ISTF in various strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. As shown in Fig. 3A, a 13-kDa substance was present in all strains and other fractions were expressed variably. We then performed further purification of the partially purified material using these monoclonal antibodies. For the setup of immunoaffinity purification, purified monoclonal antibodies were covalently attached to CNBr-activated CL4B. ISTF was eluted in a major peak during a phosphoric acid wash; this material was analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE on a 16.5% gel and stained with silver stain. The purified material included 70-, 40-, and 13-kDa bands (Fig. 1B). The immunoaffinity-purified material was concentrated and applied to a native preparative PAGE gel. The particular conditions in the native PAGE were designed to favor the migration of ISTF, and the material recovered resulted in the similar pattern shown in Fig. 1B. When the material was electroeluted from the gel, protein content was detected only in the fraction containing a 13-kDa band. The same results were shown for the lymphocyte-proliferating activity of equally concentrated electroeluents of three fractions (Fig. 4). Neither protein content nor lymphocyte-proliferating activity was evident in other concentrated fractions. The 13-kDa fraction was further separated by SDS-preparative PAGE in which the denaturation step was carried out at 37°C rather than by boiling in the SDS loading buffer. When the ISTF produced by this final purification was applied to a 16.5% resolving gel, it resulted in a single band corresponding to a molecular mass of 13 kDa (Fig. 1B). To evaluate the presence of 13-kDa ISTF in various fractions of A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29522, immunoblot analysis was carried out. Actually this substance was present mainly in the bacterial lysate and to a slight extent in the culture supernatant (Fig. 3B). We could obtain the purified ISTF from the bacterial lysate using the same procedure (data not shown). The purification procedure is shown in Table 1 and demonstrates a 300-fold enrichment.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified ISTF. (A) The gel was 12% polyacrylamide and was stained with Coomassie blue (lanes 1 to 3) and silver stain reagents (lane 4) to disclose protein bands. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, biologically active fraction eluted from the size exclusion column; lane 3, biologically active fraction eluted from the Reactive Yellow-3 dye affinity column; lane 4, same as lane 3 but silver stained. (B) One microgram of protein was loaded onto a 16.5% polyacrylamide gel that was stained with silver stain reagents. Lane 1, fraction eluted from immunoaffinity column; lane 2, fraction eluted from SDS-gel preparative electrophoresis; lane 3, molecular weight markers.

FIG. 2.

Blocking effects of monoclonal antibodies 64D10 and 75B2 on the lymphoproliferative activity of ISTF. Partially purified ISTF (10 μg/ml) and the monoclonal antibody at an indicated concentration were added to splenocyte cultures from BALB/c mice, and proliferation was measured on day 3 as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Values are means and standard deviations from three different experiments with triplicate samples.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot analysis of ISTF production. (A) Whole fractions of A. actinomycetemcomitans standard strains and clinical isolates. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, clinical isolate J1; lane 3, ATCC 29522; lane 4, ATCC 43717; lane 5, ATCC 43718; lane 6, ATCC 43719; lane 7, clinical isolate J2. (B) Each fraction of A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29522 is shown. Lane 1, whole fraction; lane 2, insoluble fraction; lane 3, soluble fraction; lane 4, culture supernatant. In each lane, 10 μg of protein was loaded onto a 16.5% polyacrylamide gel. Equal protein loading and transfer were verified by Ponceau S staining of filters.

FIG. 4.

Lymphoproliferative activity of fractions that had been separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoaffinity chromatography-purified ISTF was subjected to SDS-PAGE in a 16.5% polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed. Fractions of ISTF were electroeluted from gel sections, equally concentrated, and assayed for their proliferating activity on BALB/c splenocytes at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. Proliferation was measured on day 3 as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Values are means and standard deviations from three different experiments with triplicate samples.

TABLE 1.

Purification of ISTF from the culture supernatant of A. actinomycetemcomitans

| Fraction | Biologic activity (μg/ml)a |

|---|---|

| Concentrated culture supernatant | 3 |

| Sephacryl S-200 column | 1 |

| Reactive Yellow-3 dye affinity column | 0.1 |

| Immunoaffinity column | 0.01 |

| SDS-preparative PAGE | 0.01 |

Splenocytes from BALB/c mice were incubated at a concentration of 2 × 105 per well with sequentially diluted material of each fraction (10, 5, 3, 1, 0.5, 0.3, 0.1, 0.05, 0.03, and 0.01 μg/ml). Biologic activity is defined as the highest concentration resulting in 50% of the maximum spleen cell-proliferating response, which was measured in the 2- or 3-day cultures by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine during the last 16 h.

Lymphocyte-proliferating activity of ISTF.

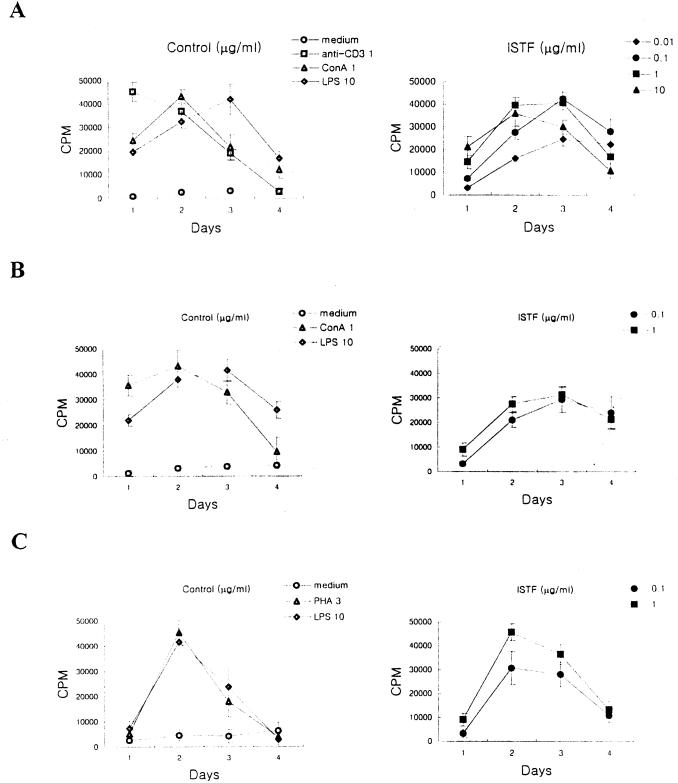

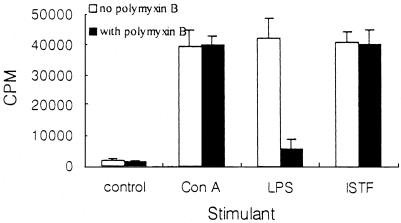

The lymphocyte-proliferating activities of control stimulants (anti-CD3, concanavalin A [ConA], LPS, or phytohemagglutinin [PHA]) and ISTF were tested using mouse splenocytes of two different major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotypes (BALB/c [H-2d] and C57BL/6 [H-2b]) and human PBMC (Fig. 5). The concentrations of ISTF which elicited proliferation of splenocytes from BALB/c mice ranged from 0.01 to 10 μg of protein/ml. Splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice gave a similar profile of response to ISTF, but their responses were lower than those of BALB/c mice. Human PBMC also showed good responses against ISTF. Based on these data, all subsequent experiments to assess the lymphocyte-proliferating activity of ISTF were conducted with splenocytes obtained from 8-week-old BALB/c mice, tested on day 3 after culture initiation. Heat treatment of ISTF demonstrated that ISTF maintained its lymphocyte-proliferating activity at 50°C for 1 h, while treatment for 1 h at 75 and 100°C reduced its activity to 50 and 95%, respectively. The lymphocyte-proliferating activity induced by ISTF was sensitive to proteolytic digestion with proteinase K (data not shown). And the lymphocyte-proliferating activity of ISTF was not blocked by coincubation with polymyxin B, a ligand for the lipid A region of LPS, at 50 U/ml (Fig. 6). An E-Toxate Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Sigma) was used to test endotoxin levels in the purified ISTF and demonstrated that they were lower than 10 pg/ml. These results showed that ISTF was a proteinaceous material and that the preparations for ISTF were not contaminated by LPS, which is the potent bacterial component capable of stimulating lymphocyte proliferation.

FIG. 5.

Lymphoproliferative activity of ISTF. Splenocytes from BALB/c mice (A) or C57BL/6 mice (B), or human PBMC (C), were incubated at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well with control stimulants (anti-CD3, 1 μg/ml; ConA, 1 μg/ml; PHA, 1 μg/ml; LPS, 10 μg/ml) or ISTF (▴, 10 μg/ml; ■, 1 μg/ml; ●, 0.1 μg/ml; ⧫, 0.01 μg/ml). Proliferation was measured in the cultures on the indicated days by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine during the last 16 h. Values are means and standard deviations from three different experiments with triplicate samples.

FIG. 6.

Effect of polymyxin B on the lymphoproliferative activity of ConA (1 μg/ml), LPS (10 μg/ml), or ISTF (1 μg/ml). Polymyxin B (50 U/ml) and a stimulant (filled bars) or the stimulant alone (open bars) was added to splenocyte cultures from BALB/c mice, and proliferation was measured on day 3 as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Values are means and standard deviations from three different experiments with triplicate samples.

Identification of responding cell subpopulation.

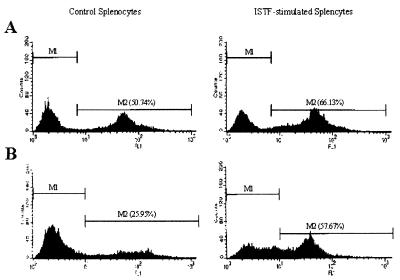

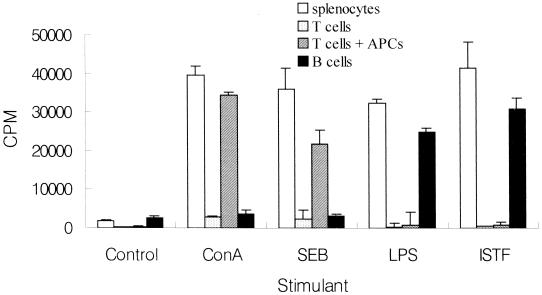

Immunofluorescent analysis for CD3, CD4, CD8, and B220 on the cell surface using flow cytometry was performed to compare lymphocyte subpopulations of ISTF-stimulated splenocytes with those of control cells. There was no significant difference in the frequencies of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells (data not shown). The average frequency of B220+ cells in ISTF-stimulated splenocytes was much higher than that in unstimulated cells. Representative histograms of flow cytometric analysis are shown in Fig. 7. These results suggested that the main proliferating cells responding to ISTF were B220+ cells. The cell types responsible for the observed proliferation stimulated by ISTF were confirmed by cell fractionation experiments (Fig. 8). The cell fractions used as the T and B cells in the present experiments consisted of at least 95% CD3+ and 98% B220+ surface Ig+ cells, respectively. As expected, T cells lost their responses to LPS, ConA, and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), and B cells lost their responses to T-cell mitogens, indicating the effectiveness of T- and B-cell fractionation. Because ConA- or SEB-induced T-cell activation requires the presence of class II MHC-positive APCs, the addition of 5 × 105 mitomycin C-treated APCs, which did not respond to any stimulants, caused significant recovery of the T-cell responses to either ConA or SEB. ISTF did not induce proliferation of T cells, even though APCs were added. However, B cells mounted a good response to ISTF as well as to LPS. These findings demonstrated that the response of splenocytes to ISTF was due to B-cell proliferation.

FIG. 7.

Representative histogram of B220+ cells in ISTF-stimulated splenocytes. Splenocytes from BALB/c mice were cultured with or without ISTF for 3 days (A) or for 2 weeks (B), and the expression of B220 was assayed by flow cytometry. For 2-week cultures, fresh medium supplemented with 1 μg of ISTF/ml and 2 U of IL-2/ml was added every 3 days.

FIG. 8.

Proliferative responses of splenocytes to various stimulants. Unfractionated splenocytes (open bars), T cells (light shaded bars), T cells with APCs (dark shaded bars), or B cells (filled bars) from BALB/c mice were incubated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml), ConA (1 μg/ml), SEB (3 μg/ml), LPS (10 μg/ml), or ISTF (1 μg/ml). Proliferation was measured on day 3 as for the experiment for which results are shown in Fig. 5. Values are means and standard deviations from three different experiments with triplicate samples.

DISCUSSION

In periodontal disease, the most prevalent chronic inflammatory diseases of humans, various gram-negative bacteria accumulate between the tooth and the gum (15). The bacteria implicated in the pathology of the disease do not penetrate the periodontal tissues, and tissue pathology is believed to be largely driven by soluble factors released from the bacteria (25). One organism in particular, A. actinomycetemcomitans, is an important periodontopathogen that has been implicated in juvenile and adult periodontitis (33). Although the pathogenic mechanism of periodontal disease is not well known, it is generally accepted that the immune system plays an important role in bacterial infection and destruction of the periodontal tissues. Human periodontitis lesions are histologically characterized by a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes (19, 20). The role of lymphocytes in these lesions is unclear. However, it can be assumed that there are alterations in the regulatory events that govern immune responsiveness in periodontal disease. These alterations may affect local lymphocyte proliferation and function, and may contribute to increased susceptibility to disease in certain individuals. Many authors have reported that lymphoblastic responses are induced by bacterial antigens in patients with gingivitis and periodontitis (3, 9, 10, 12, 14, 19, 21, 28). In our present studies, we found that A. actinomycetemcomitans produced a proteinaceous ISTF. Several protein purification strategies were devised in an attempt to isolate the active constituent. After size exclusion chromatography, dye-ligand affinity chromatography, immunoaffinity chromatography using monoclonal antibodies, and preparative electrophoresis of bacterial-culture supernatants, only one bioactive band with an apparent molecular mass of 13 kDa was resolved (Fig. 1). For the discontinuous SDS-PAGE, we used Tricine as the trailing ion, which allowed a resolution of small proteins at lower acrylamide concentrations than in glycine-SDS-PAGE systems. Superior resolution, especially in the range between 5 and 20 kDa, was achieved.

Recently, some authors have suggested that the pathogenesis of periodontitis could be explained by superantigen production by periodontopathic bacteria, which induces large-scale T-cell activation, cytokine production, and polyclonal B-cell activation (1, 16, 17, 32). In this study, we have determined whether ISTF had the ability to activate naive T cells in a manner consistent with their activation by a known superantigen, SEB. Our data are clearly at odds with the definition of this substance as a superantigen, since T cells were not responsible for the observed lymphocyte proliferation induced by ISTF, compared with vigorous activation by SEB (Fig. 8). Human T cells, isolated from PBMC using rosetting procedures with neuraminidase-treated sheep red blood cells, also failed to respond to ISTF, even though APCs were added (data not shown). Among the proliferating lymphocytes stimulated by ISTF, the percentages of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells were not changed, but the percentage of B220+ B cells was significantly increased (Fig. 7). Similarly, it has been reported that extracts of periodontopathic bacteria do not have superantigen activity (22), and T-cell responses to these oral bacteria are unlikely to be due to superantigen stimulation (29). As noted, stimulation of T cells by periodontopathic bacteria in vitro appears to result in preferential activation of certain Vβ types, and there is skewing of the Vβ repertoire of T cells isolated from inflamed periodontal tissues. However, it should be emphasized that Vβ perturbation is not per se a compelling argument for superantigen activation, since antigen-specific activation also involves selection of a limited spectrum of αβ T-cell receptor (TCR)-bearing T cells. A study performed to investigate T-cell traffic to periodontal tissues during infection with the periodontal pathogen A. actinomycetemcomitans revealed that the dynamics of cell entry into periodontal lesions vary for activated T lymphocytes with different antigenic specificities, indicating the significance of the antigen in lymphocyte traffic to periodontal tissues (11).

Other studies have described the B-lymphocyte mitogenicity of A. actinomycetemcomitans. Whole A. actinomycetemcomitans bacteria (formalin killed) were reported to induce a vigorous mitogenic effect in rat B cells; this is not a specific immune response, since it is observed in B-cell-containing lymphoid cell cultures from both naive and immunized, normal and nude rats (31). And the strong mitogenic activity of killed A. actinomycetemcomitans bacteria on B cells in culture was reported to be related to the LPS of the bacterial surface (4). An extracellular proteinaceous substance extracted from the supernatant medium in which A. actinomycetemcomitans cells have grown was mentioned to have a mitogenic activity toward murine B cells which was only slightly reduced by the same proportions of polymyxin B (18). Another fraction which exhibited B-cell-mitogenic activity was identified during purification of ISF from the cytoplasmic soluble fraction of A. actinomycetemcomitans (13). In this study, we purified a novel 13-kDa B-cell-proliferating substance distinct from LPS. We did not recognize LPS contaminant in the purified ISTF by sensitive silver staining and colorimetric Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (less than 10 pg/ml). Further, the mitogenic activity of ISTF was not inhibited by polymyxin B, which blocks the lipid A of bacterial LPS and prevents expression of its mitogenic properties toward B cells (Fig. 6), and was evident in spleen cells from the classically LPS-nonresponsive C3H/HeJ mice (data not shown). Additionally, immunoblot analysis revealed that ISTF was a component of bacteria, could exist as a soluble form, and (like LPS) was released by growing and/or lysed bacteria (Fig. 3). These results suggest that released ISTF may play an important role in the pathogenesis associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans infection. The presence of ISTF-producing bacteria in the gingival crevice environment would be expected to induce local B-cell proliferation, independent of any specific immune response to the same bacteria or their products. This may be a factor in the B-cell infiltration seen in the tissues of patients with periodontal disease and A. actinomycetemcomitans infection (6).

In summary, we have purified a novel 13-kDa ISTF that is produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans. This material is distinct from LPS and has B-cell-mitogenic activity, which is more relevant to the explanation of pathologic findings of periodontal lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant HMP-97-M-2-0040 from the Department of Health and Welfare of the Republic of Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berglundh T, Liljenberg B, Tarkowski A, Lindhe J. Local and systemic TCR V gene expression in advanced periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bromley G S, Solender M. Hand infection caused by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Hand Surg. 1986;11:434–436. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson S L, Ranney R R, Burmeister J A, Tew J G. Blastogenic responses by lymphocytes from periodontally healthy populations induced by periodontitis-associated bacteria. J Periodontol. 1982;53:743–751. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.12.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastcott J W, Taubman M A, Smith D J, Holt S C. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans mitogenicity for B cells can be attributed to lipopolysaccharide. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:8–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellner J J, Spagnuolo P J. Suppression of antigen and mitogen induced human T lymphocyte DNA synthesis by bacterial lipopolysaccharide: mediation by monocyte activation and production of prostaglandins. J Immunol. 1979;123:2689–2695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel D. Lymphocyte function in early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:332–336. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3s.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Getka T P, Alexander D C, Parker W B, Miller G A. Immunomodulatory and superantigen activities of bacteria associated with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:909–917. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.9.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofstad T, Stallemo A. Subacute bacterial endocarditis due to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Scand J Infect Dis. 1981;13:78–79. doi: 10.1080/00365548.1981.11690372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton J E, Leiken S, Oppenheim J J. Human lymphoproliferative reaction to saliva and dental plaque deposits: an in vitro correlation with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1972;43:522–527. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.9.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanyi L, Lehner T. Stimulation of lymphocyte transformation by bacterial antigens in patients with periodontal disease. Arch Oral Biol. 1970;15:1089–1096. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(70)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T, Shimauchi H, Eastcott J W, Smith D J, Taubman M A. Antigen direction of specific T-cell clones into gingival tissues. Immunology. 1998;93:11–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiger R D, Wright W H, Creamer H R. The significance of lymphocyte transformation to various microbial stimulants. J Periodontol. 1974;45:780–785. doi: 10.1902/jop.1974.45.11.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurita-Ochiai T, Ochiai K. Immunosuppressive factor from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans down regulates cytokine production. Infect Immun. 1996;64:50–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.50-54.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang N P, Smith F N. Lymphocyte blastogenesis to plaque antigens in human periodontal disease. I. Populations of varying severity of disease. J Periodontal Res. 1977;12:298–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1977.tb00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liakoni H, Barber P, Newman H N. Bacterial penetration of pocket soft tissues in chronic adult and juvenile periodontitis cases. An ultrastructural study. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathur A, Michalowicz B, Yang C, Aeppli D. Influence of periodontal bacteria and disease status on V beta expression in T cells. J Periodontal Res. 1995;30:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakajima T, Yamazaki K, Hara K. Biased T cell receptor V gene usage in tissues with periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishihara T, Koga T, Hamada S. Extracellular proteinaceous substances from Haemophilus actinomycetemcomitans induce mitogenic responses in murine lymphocytes. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osterberg S K, Page R C, Sims T, Wilde G. Blastogenic responsiveness of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from individuals with various forms of periodontitis and effects of treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:72–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel P K, Seitchik M W. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a new cause for granuloma of the parotid gland and buccal space. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patters M R, Genco R J, Reed M J, Mashimo P A. Blastogenic response of human lymphocytes to oral bacterial antigens: comparison of individuals with periodontal disease to normal and edentulous subjects. Infect Immun. 1976;14:1213–1220. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.5.1213-1220.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petit M D, Stashenko P. Extracts of periodontopathic microorganisms lack functional superantigenic activity for murine T cells. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabie G, Lally E T, Shenker B J. Immunosuppressive properties of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1988;56:122–127. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.122-127.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salman R A, Bonk S J, Salman D G, Glickman R S. Submandibular space abscess due to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44:1002–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(86)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scoransky S S, Haffajee A D. Microbial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of destructive periodontal diseases: a critical assessment. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:195–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shenker B J, Vitale L A, Welham D A. Immune suppression induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: effects on immunoglobulin production by human B cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3856–3862. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3856-3862.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenker B J, McArthur W P, Tsai C C. Immune suppression induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. I. Effects on human peripheral blood lymphocyte responses to mitogens and antigens. J Immunol. 1982;128:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith F N, Lang N P. Lymphocyte blastogenesis to plaque antigen in human periodontal disease. II. The relationship to clinical parameters. J Periodontal Res. 1977;12:310–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1977.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassenaar A, Reinhardus C, Thepen T, Abraham-Inpijn L, Kievits F. Cloning, characterization, and antigen specificity of T-lymphocyte subsets extracted from gingival tissue of chronic adult periodontitis patients. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2147–2153. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2147-2153.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weir D M, Blackwell C C. Interaction of bacteria with the immune system. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1983;10:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshie H, Taubman M A, Ebersole J L, Olsen C L, Smith D J, Pappo J. Activation of rat B lymphocytes by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1985;47:264–270. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.264-270.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zadeh H H, Kreutzer D L. Evidence for involvement of superantigens in human periodontal diseases: skewed expression of T cell receptor variable regions by gingival T cells. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zambon J J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zappa U. Histology of the periodontal lesion: implications for diagnosis. Periodontology 2000. 1995;7:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]