Key Points

Question

What is the relative cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab vs aflibercept for treatment of macular edema associated with central or hemiretinal vein occlusion?

Findings

In this economic evaluation study of a simulated cohort of 5000 patients, first-line treatment with bevacizumab with the option to change to aflibercept in those who did not respond to the first-line treatment was cost-effective compared with initiating treatment with aflibercept in most patients.

Meaning

As anticipated given the minimal difference in visual acuity outcomes and large cost differences between aflibercept and bevacizumab, first-line treatment of macular edema associated with central or hemiretinal vein occlusion with bevacizumab was cost-effective in this study.

This economic evaluation study evaluates the relative cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab vs aflibercept for treatment of macular edema associated with central or hemiretinal vein occlusion.

Abstract

Importance

Retinal vein occlusion is the second most common retinal vascular disease. Bevacizumab was demonstrated in the Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2) to be noninferior to aflibercept with respect to visual acuity in study participants with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) or hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO) following 6 months of therapy. In this study, the cost-utility of bevacizumab vs aflibercept for treatment of CRVO is evaluated.

Objective

To investigate the relative cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab vs aflibercept for treatment of macular edema associated with CRVO or HRVO.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This economic evaluation study used a microsimulation cohort of patients with clinical and demographic characteristics similar to those of SCORE2 participants and a Markov process. Parameters were estimated and validated using a split-sample approach of the SCORE2 population. The simulated cohort included 5000 patients who were evaluated 100 times, each with a different set of characteristics randomly selected based on the SCORE2 trial. SCORE2 data were collected from September 2014 October 2019, and data were analyzed from October 2019 to July 2021.

Interventions

Bevacizumab (followed by aflibercept among patients with a protocol-defined poor or marginal response to bevacizumab at month 6) vs aflibercept (followed by a dexamethasone implant among patients with a protocol-defined poor or marginal response to aflibercept at month 6).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incremental cost-utility ratio.

Results

The simulation demonstrated that patients treated with aflibercept will have an expected cost $18 127 greater than those treated with bevacizumab in the year following initiation. When coupled with the lack of clinical superiority over bevacizumab (ie, patients treated with bevacizumab had a gain over aflibercept in visual acuity letter score of 4 in the treated eye and 2 in the fellow eye), these results demonstrate that first-line treatment with bevacizumab dominated aflibercept in the simulated cohort of SCORE2 participants. At current price levels, aflibercept would be considered the preferred cost-effective option only if treatment restored the patient to nearly perfect health.

Conclusions and Relevance

While there will be some patients with CRVO-associated or HRVO-associated macular edema who will benefit from first-line treatment with aflibercept rather than bevacizumab, given the minimal differences in visual acuity outcomes and large cost differences for bevacizumab vs aflibercept, first-line treatment with bevacizumab is cost-effective for this condition.

Introduction

After diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the most common retinal vascular disease. Population-based studies estimate a worldwide prevalence of approximately 16 million adults.1 Vision loss in the presence of RVO is most commonly due to macular edema (central retinal swelling)—this has been a therapeutic target of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment. Aflibercept, an anti-VEGF therapy, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for macular edema due to RVO.2 Off-label use of bevacizumab for this indication is widespread due to its cost relative to the other anti-VEGF treatments as well as its efficacy and safety that have been demonstrated for other retinal diseases (age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema).3,4 The Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2) trial was initiated to determine whether bevacizumab was noninferior to aflibercept for treatment of macular edema due to central RVO (CRVO) or hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO).5

In SCORE2, 362 participants were randomized to initiate treatment with 6 months of monthly injections with either bevacizumab or aflibercept. At month 6, protocol-defined good responders were rerandomized to continued monthly dosing or treat-and-extend dosing of their originally assigned study drug, and protocol-defined poor or marginal responders were switched to alternative treatment. The SCORE2 investigators found a mean visual acuity letter score (VALS) increase from baseline to 6 months of 18.6 in the bevacizumab group and 18.9 in the aflibercept group (model-based estimate of mean difference of −0.14, meeting criteria for noninferiority). Despite this finding of noninferiority and the lower cost of bevacizumab, some physicians choose aflibercept as the first-line treatment for RVO due to improved anatomical outcomes, reports of fewer required injections to achieve desired clinical outcomes, and a variety of other factors. However, when setting coverage policies, government and private insurers typically consider all aspects of treatment, including comparative effectiveness, adverse events, and the full cost of the patient journey. The cost of bevacizumab repackaged for intraocular injection is reported by some authorities as less than one-tenth that of aflibercept,6 so this difference in cost must be weighed against these other aspects of treatment. To provide additional perspective, the SCORE2 investigators conducted this economic evaluation of the treatment options for RVO as examined in the SCORE2 trial.

Economic evaluation compares the cost of providing an intervention to the benefit created, in this case measured by quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). While the results of the SCORE2 study, when juxtaposed to the relatively high cost of aflibercept, may make the results of our study self-evident, we conducted this study to gain insights into the nuances of the cost-benefit relationship in treatment of CRVO and HRVO. In particular, we hoped to learn if there were circumstances under which aflibercept might be considered the preferred first-line treatment. To explore this, we incorporated the results of the SCORE2 trial into an economic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of treatment of macular edema secondary to CRVO or HRVO and estimated the incremental cost-utility of aflibercept vs bevacizumab as first-line treatment.

Methods

We constructed an economic model comparing 2 competing treatment approaches: (1) initiate treatment with bevacizumab; if the patient demonstrates a protocol-defined poor or marginal treatment response after 6 monthly injections, switch to aflibercept; or (2) initiate treatment with aflibercept; if the patient demonstrates a poor or marginal response after 6 monthly injections, switch to dexamethasone. To assess the relative cost-effectiveness of these approaches, we constructed a Markov model estimated using a microsimulation process with 5000 patients (simulants) based on SCORE2 data. Costs of treatment with bevacizumab and aflibercept were taken from the literature. Patient-centered effectiveness was measured using QALYs. This economic evaluation was conducted consistent with the guidelines of the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research/Society for Medical Decision Making best practices and the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) reporting guideline.7

SCORE2 Study

The details of SCORE2 are presented elsewhere,5 but we summarize them here. The trial was a multicenter randomized study funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI) and monitored by an NEI-appointed data and safety monitoring committee. Participants had a best-corrected electronic Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) VALS between 19 and 73 letters (approximate Snellen equivalent of 20/400 to 20/40), macular edema with central retinal involvement due to CRVO or HRVO on clinical examination, and a central subfield thickness (CST) of 300 μm or 320 μm or greater, depending on the spectral-domain optical coherence tomography measurement device used. For the results to be as generalizable as possible, eligibility criteria permitted inclusion of study participants with HRVO to a maximum of 25% of the total study sample. A history of intravitreal corticosteroid or anti-VEGF use was allowed if such exposure occurred more than 2 months before randomization.

Study eyes were randomized 1:1 to intravitreal bevacizumab, 1.25 mg, every 4 weeks for 6 months or intravitreal aflibercept, 2.0 mg, every 4 weeks for 6 months. Bevacizumab was purchased with trial funding and repackaged into single-use vials by the University of Pennsylvania Investigational Drug Service. Aflibercept was provided by the manufacturer.

Model Description

For the SCORE2 economic evaluation, we considered 2 treatment options:

1. Initiation of treatment with bevacizumab, switching to aflibercept if the patient was observed to have a protocol-defined poor or marginal response to bevacizumab at 6 months.

2. Initiation of treatment with aflibercept, switching to a dexamethasone implant if the patient was observed to have a protocol-defined poor or marginal response to aflibercept at 6 months.

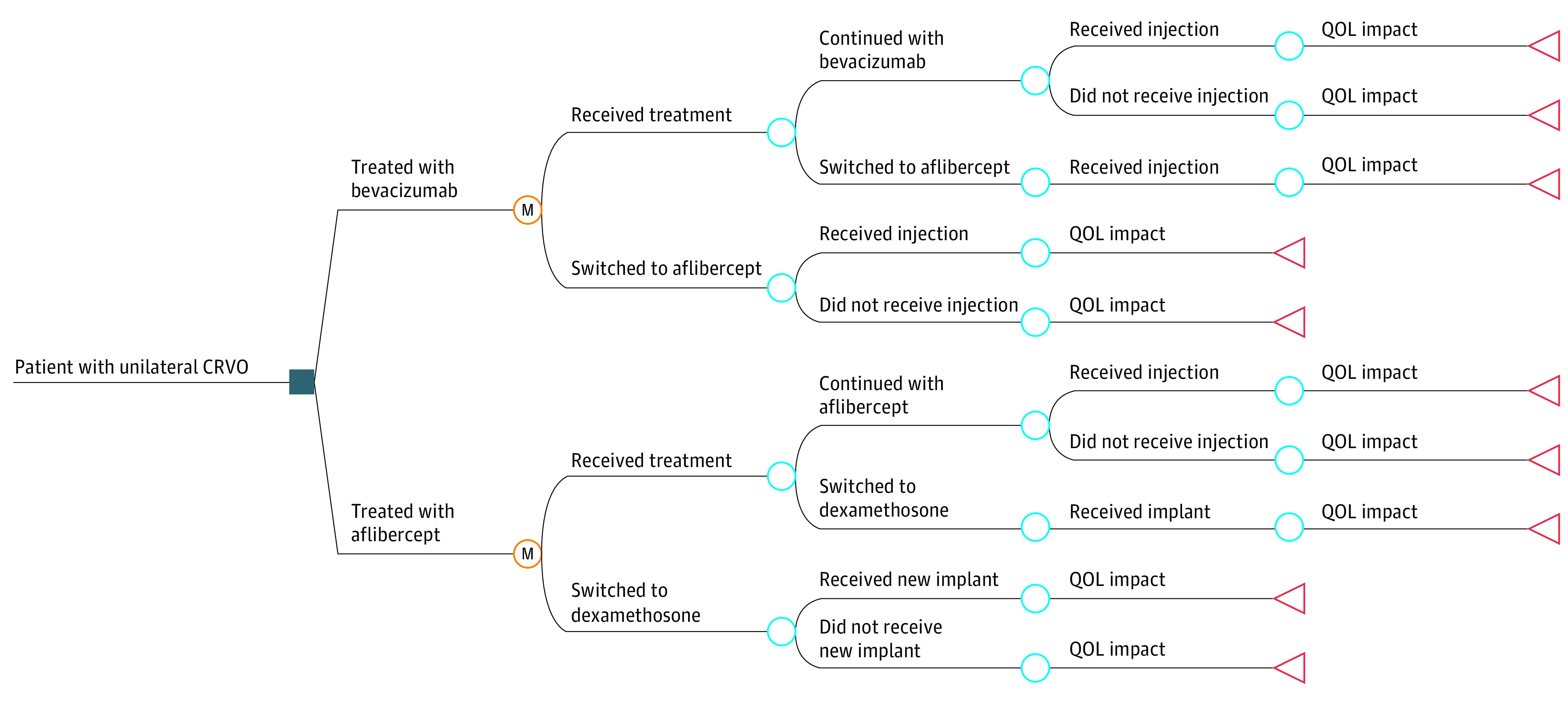

The model was developed in consultation with clinical experts from the SCORE2 Steering Committee (I. U. S., M. S. I., and B. A. B.) along with an expert in model development (S. M. K.). A schematic of the model used for evaluation is provided in the Figure. We simulated 1 year of care for the cohort of patients. Further details on the approach are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Figure. Illustration of Treatment Process Modeled in Economic Evaluation of Treatment of Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO).

M nodes indicate Markov nodes (ie, the beginning of the Markov cycle). QOL indicates quality of life.

The influence of uncertainty on model results was evaluated using both 1-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses to determine for which parameters a change in the base value resulted in a change in the cost-effectiveness decision (ie, if bevacizumab was found to be cost-effective in the base case, the change in the value would result in it not being cost-effective, or vice-versa).8 In 1-way sensitivity analyses, 1 variable at a time is changed, and its impact on cost-effectiveness is examined. In probabilistic sensitivity analysis, all variables in the model are varied simultaneously. For these analyses, a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $150 000 per QALY was used to define of cost-effectiveness. For the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, we tested a range of WTP thresholds up to $200 000 per QALY.

The model was developed taking a health sector perspective as recommended by the Second Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine.9 This approach implies that we will capture both the direct costs of care and the impact on quality of life using QALYs. However, other societal costs, such as productivity loss and family spillover effects, are not considered—even though this burden is likely substantial for the patient, their family, and friends—as payers rarely consider these in their decision-making.

Model Inputs

The variables included in the model are detailed in Table 1. Note that the parameters constitute the probabilities associated with transitions at each decision node. These transition probabilities were identified during the process of model development. The required parameters were provided to the SCORE2 biostatistical team, which estimated the parameters from a random sample of one-half the SCORE2 participants.

Table 1. SCORE2 Variables With Descriptions Included in the Economic Model.

| Variable description | Distribution type | Measure, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of patient, y | Normal | 69 (12) |

| Men, % | β | 55 (5.3) |

| Distribution of White race, % | β | 78 (4.4) |

| Visit with injection, % | ||

| Bevacizumab | β | 94.3 (7.9) |

| Aflibercept | β | 95.5 (2.1) |

| Baseline VALS in the treated eye (Snellen equivalent) | Normal | 50 (15) |

| Snellen equivalent | NA | 20/100 |

| Baseline VALS in the fellow eye | Normal | 81 (16) |

| Snellen equivalent | NA | 20/85 |

| Change in VALS at 1 mo in the bevacizumab arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 10.5 (12.2) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 1.0 (5.5) |

| Change in VALS at 1 mo in the aflibercept arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 14.5 (12.8) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | −0.5 (3.7) |

| Change in VALS at 2 mo in the bevacizumab arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 12.5 (16.0) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 0.8 (6.5) |

| Change in VALS at 2 mo in the aflibercept arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 16.4 (13.8) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 0.7 (4.5) |

| Change in VALS at 3-6 mo in the bevacizumab arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 17.3 (16.5) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 2.4 (6.5) |

| Change in VALS at 3-6 mo in the aflibercept arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 18.4 (16.5) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 0.2 (5.7) |

| Change in VALS at 7-12 mo in the bevacizumab arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 19.7 (18.0) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 3.6 (6.9) |

| Change in VALS at 7-12 mo in the aflibercept arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 19.6 (15.7) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 1.6 (5.4) |

| Change in VALS at 7-12 mo in the dexamethasone arm | ||

| Treated eye | Normal | 11.1 (13.4) |

| Fellow eye | Normal | 2.5 (5.4) |

| Patient taking bevacizumab switching to aflibercept at 6 mo | β | 20.8% (4.2) |

| Patient taking aflibercept switching to dexamethasone implant at 6 mo | β | 9.3% (3.1) |

| Baseline central subfield thickness, μm | ||

| Bevacizumab treatment | Normal | 637 (181) |

| Aflibercept treatment | Normal | 606 (148) |

| Change in central subfield thickness at 1 mo in the treated eye | ||

| Bevacizumab treatment | Normal | 328 (230) |

| Aflibercept treatment | Normal | 378 (198) |

| Change in central subfield thickness at 2-6 mo in the treated eye | ||

| Bevacizumab treatment | Normal | 377 (257) |

| Aflibercept treatment | Normal | 412 (217) |

| Change in central subfield thickness at 7-12 mo in the treated eye | ||

| Bevacizumab treatment | Normal | 415 (258) |

| Aflibercept treatment | Normal | 397 (207) |

| Dexamethasone treatment | Normal | 374 (240) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; VALS, visual acuity letter score.

Given that the SCORE2 trial found no difference in visual acuity outcomes, long-term costs of care were deemed to be irrelevant to the decision to be made. Thus, costs included in the model are limited to those associated with medication and administration. These are $150 per dose for bevacizumab, $1941 per dose for aflibercept, and $1650 per implant for dexamethasone implant. There is no standard cost of these medications or for their administration. Therefore we have relied on estimates provided by the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Society of Retinal Surgeons in an advocacy document concerning the cost of administration.6 While the US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services has announced a project to estimate the cost of these intravitreal medications to the Medicare program, the final report is not due until 2023.10 Given that dexamethasone is associated only with the aflibercept arm and that is already the most expensive medication, we make the conservative assumption that only 1 dexamethasone implant is required.

Parameters of the model were developed using a split-sample approach. The SCORE2 sample was divided in half, selecting SCORE2 participants at random. Parameters were estimated from one-half of SCORE2 participants (referred to as the training sample). After the economic model was estimated, the model estimates of pretreatment and posttreatment visual acuity as well as pretreatment and posttreatment retinal thickness were compared with estimates made from SCORE2 participants who were not included in the training sample (ie, the validation sample) using a t test. A nonsignificant value for this test (ie, P > .05) was considered to indicate a good model fit.

The SCORE2 investigators collected information on adverse events. However, there was no difference in adverse events with respect to cost or visual outcome consequences that would affect the model results, so these were not considered in this evaluation.

Outcomes Measurement

In our investigation, we measured quality of life using utility, which, in contrast to clinical measures, is a preference-based measure that quantifies the person’s perception of the importance of functional limitation. Utility is measured on a scale from 0.0 to 1.0, with 0.0 indicating the value of a state of health comparable with death and 1.0 indicating the value for perfect health. The methods by which utility is measured have been described in detail elsewhere.11 The utility measure is used to calculate a QALY, a measure of a person’s expected life span that is weighted by the quality of life enjoyed during those years. For example, assume that living with congestive heart failure is found to have an associated utility loss of 0.35 (or 35%) for an annual utility of 0.65. Each year, the person would experience a quality of life that is 65% of a year spent in perfect health, or a QALY of 0.65. If they live for 5 years, they would accumulate 3.25 QALYs compared with the 5.0 QALYs of someone living in perfect health.

To calculate utility for the SCORE2 model, we used a 2-stage process. First, baseline utility scores were estimated for all participants from NEI Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) responses of SCORE2 participants, applying an algorithm from Payakachat et al12 in which the investigators mapped the NEI-VFQ to the Euro-QoL 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) quality-of-life instrument. Next, utility scores were regressed against VALS and other candidate factors using a mixed model method. In this modeling, we found that the ETDRS VALS in the best-seeing eye and asymmetry between the 2 eyes provided the best fit for the NEI-VFQ–derived utility scores. The equation used to derive the utility for each Markov cycle is described as Utility = −0.3622 + (0.02168 × Best-Seeing Eye VALS) + (−0.00831 × ΔVALS)+(Age × 0.008496), where ΔVALS is the difference in VALS between the best-seeing eye and fellow eye and age is the participant’s age at baseline. The result is the log of the QALY during that month; thus, it must be converted from the log to make the QALY calculation. Analyses were conducted using TreeAge Pro Healthcare (TreeAge) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The clinical results of our model are described in Table 2. At 1 year, simulated patients who were treated with bevacizumab experienced a VALS improvement of 22 in the treated eye, while those treated with aflibercept experienced a VALS improvement of 18. The comparable VALS improvement in the fellow eye was 3 for bevacizumab and 1 for aflibercept. The change observed in the treated eye was not materially different from the average VALS improvement of 18.6 and 18.9 observed in the SCORE2 trial.5 The simulated decrease in retinal thickness at 12 months (330 μm for bevacizumab and 360 μm for aflibercept) is less than observed in the SCORE2 trial at 6 months (392 μm and 453 μm, respectively). Also, there is a difference in percentage thickness reduction between our model and SCORE2 (in the model, the reduction for bevacizumab is 91% of that seen in aflibercept vs 86% in SCORE2).5 However, retinal thickness does not affect visual acuity outcomes or the treatment process in the model, so the difference did not affect the outcome of the model.

Table 2. Key Clinical Outcomes.

| Outcome | Bevacizumab | Aflibercept | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fellow eye | Treated eye | Fellow eye | Treated eye | |

| VALS | ||||

| Baselinea | 81 | 50 | 81 | 50 |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/25 | 20/100 | 20/25 | 20/100 |

| Ending | 84 | 72 | 82 | 68 |

| Snellen equivalent | 20/20 | 20/40 | 20/25 | 20/50 |

| Central subfield thickness, μm b | ||||

| Baseline | NA | 638 | NA | 606 |

| Ending | NA | 308 | NA | 246 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; VALS, visual acuity letter score.

To ensure balance at baseline between the 2 treatment strategies, baseline visual acuity for each simulated patient was randomly drawn from the same distribution. Thus, this balance was expected.

Central subfield thickness as measured for the treated eye only in SCORE2. For modeling purposes, it did not enter into calculations of economic outcomes, nor was it considered as a predictor of treatment. Thus, it is reported here for information only.

In the split-sample comparison of the SCORE2 validation sample to the simulation, all comparisons were nonsignificant. As such, we felt that the simulation properly represented the experience of the SCORE2 participants.

Our economic modeling findings are detailed in Table 3. Participants who initiated therapy with bevacizumab accrued a cost of $3213 through 1 year of treatment and improved their QALYs from 0.845 to 0.871 (a gain of 0.026 QALYs). In contrast, patients who initiated aflibercept accrued a 12-month cost of $21 340 (an increase of $18 127 vs bevacizumab) and improved their QALYs from 0.845 to 0.865 (a gain of 0.020 QALYs). As bevacizumab is both less expensive and more effective than aflibercept in terms of QALYs, we consider bevacizumab dominant compared with aflibercept for the purpose of this modeling exercise. However, given the exceptionally small difference in QALYs, we are left to assume that the difference is due to random variation in the visual acuity rather than actual differences in effectiveness, and thus we assume that dominance is due to the difference in cost of treatment rather than a difference in effectiveness.

Table 3. Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratio Calculation.

| Outcome | Bevacizumab | Aflibercept | Difference vs bevacizumab |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of treatment, $ | |||

| Baseline | NA | NA | NA |

| Ending | 3213 | 21 340 | 18 127 |

| Difference at 12 mo | 3213 | 21 340 | 18 127 |

| QALYs | |||

| Baselinea | 0.845 | 0.845 | 0 |

| Ending | 0.871 | 0.865 | 0.006 |

| Gain over 12 mo | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.006 |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | NA | NA | Aflibercept dominatedb |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year.

The balance in QALYs at baseline reflect the balance in baseline visual acuity for the 2 strategies.

Dominated indicates that the alternative treatment, bevacizumab, was both less expensive and more effective than aflibercept.

In sensitivity analyses, other than the cost of medication, there were no clinically relevant changes in parameter values that would result in the treatment decision favoring aflibercept as the first-line treatment from a cost-effectiveness perspective. We estimated the difference in effectiveness between aflibercept and bevacizumab that would be required to justify the difference in cost between the 2 treatments. We found that an increase of 0.12 QALY per year favoring aflibercept over the current value of 0.006 per year favoring bevacizumab would be required to justify the pricing difference. This is an improvement in quality of life of 0.126 QALYs per year. To achieve this level of improvement would require that the treated eye become nearly perfect in its vision, something that is clearly not clinically achievable. Similarly, our probabilistic sensitivity analyses found no combination of clinically feasible parameters (exclusive of cost reduction) that would justify use of aflibercept as a first-line treatment at a WTP of up to $200 000 per QALY.

Discussion

The purpose of economic evaluation was to evaluate the optimal use of scarce health care resources in society. There is no question that US health care costs are among the highest in the world, and this spending does not come without consequences.13 We conducted an economic evaluation of treatment of macular edema due to CRVO or HRVO and found that because there was little VALS difference and a large cost differential between aflibercept and bevacizumab, first-line use of aflibercept was unlikely to meet most accepted standards of cost-effectiveness. This finding is not surprising given the cost advantage of bevacizumab and the findings from SCORE2 of equivalent performance between the 2 medications. However, in the absence of a comprehensive evaluation, some commentators might assert that some feature of aflibercept might justify the higher cost. Our simulation and sensitivity analyses have demonstrated that it is not likely that first-line use of aflibercept is justified by safety or other clinical factors.

The SCORE2 team is not the first to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of anti-VEGF medications in people living with retinal disease. The Comparisons of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials, conducted in the early 2000s, found that bevacizumab was noninferior to ranibizumab (an anti-VEGF therapy) in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration.3 More recently, the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network conducted a study comparing panretinal laser photocoagulation with ranibizumab in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Their approach included a preplanned economic evaluation, which found that initiating treatment of patients without center-involving diabetic macular edema with ranibizumab had an incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR) in excess of $600 000 per QALY. When treatment with ranibizumab was limited to patients with center-involving diabetic macular edema, the ICUR was approximately $65 000 per QALY, something that is well within the range of those interventions that might be considered to be cost-effective.8,14 More recently, as we have done here, Hutton et al14 have also conducted an evaluation of aflibercept vs bevacizumab. In contrast to our evaluation of treatment of CRVO and HRVO, Hutton and colleagues14 evaluated treatment of diabetic macular edema. However, they also considered first-line use of aflibercept and found, as we found in this setting, that it would not meet accepted standards of cost-effectiveness without a substantial reduction in price of aflibercept.

None of these investigators has argued for the cessation of the use of ranibizumab in people living with retinal disorders. Neither is our team arguing for the cessation of treatment with aflibercept in patients living with CRVO or HRVO. However, physicians and patients might consider where application of more costly formulations represent the best use of scarce societal resources. It was our finding that starting patients with aflibercept was not cost-effective when bevacizumab is an available option. However, switching patients who do not respond to bevacizumab to aflibercept, something that was explicitly considered in our model, is clearly supported by the SCORE2 trial results as well as by our evaluation. This should not be interpreted to mean that bevacizumab should be used as a first-line treatment for all patients since (1) some patients and physicians may prefer not to use an off-label product, (2) bevacizumab routinely supplied for clinical use by compounding pharmacies may not meet the purity, stability, and shelf life standards of the product used in SCORE2, and (3) some patients may benefit from the anatomic advantages of aflibercept, which are not considered in the current cost-effectiveness analysis. In SCORE2, although bevacizumab was noninferior to aflibercept with respect to visual acuity after 6 months of monthly treatment, aflibercept was associated with a greater reduction in central subfield thickness and a higher proportion of study participants who achieved resolution of macular edema compared with bevacizumab.4 Thus, aflibercept may be preferred for patients with persistent macular edema refractory to other anti-VEGF agents. Also, as retreatment is often guided by the presence of retinal thickening, patients for whom it is particularly important to minimize the number and frequency of intravitreal injections (eg, patients with logistical barriers to returning for office visits or with limited ability to cooperate with the intravitreal injection procedure) might benefit from aflibercept, as its effectiveness in reducing macular edema may lead to fewer injections.

To our knowledge, there have been 2 previous efforts to conduct an economic evaluation of the comparative cost-effectiveness of bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept,15,16 which had similar findings to those reported here. However, these were based on the Lucentis, Eylea, Avastin in Vein Occlusion (LEAVO) trial, a study based in the UK National Health Service that was not able to establish the noninferiority of bevacizumab (due to lack of power), as was done in SCORE2.

A novel feature of our evaluation was use of utilities that were mapped to the EQ-5D using the NEI-VFQ responses of SCORE2 participants. The EQ-5D is a questionnaire designed to quickly and reliably assess the attitudes of study participants regarding the impact of their health state on their quality of life. It is viewed by many national health technology assessment authorities as the reference standard for utility assessment.17 The acceptance of this as a method for utility assessment stands in contrast to methods used by some investigators in ophthalmology who have been criticized as departing from the accepted methods.18 The purpose of the QALY is to provide a common metric for evaluation of outcome of medical treatment, enabling policy makers to make complex decisions regarding distribution of health resources.17 As an outcome measure, the QALY provides 2 important advantages to policy makers: (1) there are accepted standards defining the cost-effectiveness of a therapy based on the cost per QALY measured by the ICUR; and (2) the cost-effectiveness of interventions can be compared among various diseases and treatment goals. This latter issue is important for policy makers attempting to distribute resources across health programs (eg, comparing treating CRVO to treating prostate cancer) or across stage of disease (ie, glaucoma screening vs slowing glaucoma progression). While we use it here, it should be noted that the QALY is not without controversy in assessing vision related interventions,19 but addressing those limitations is beyond the scope of this article.

Limitations

As with any study, our evaluation has a number of limitations. First, we based our model on the SCORE2 trial, which, as is true of any randomized clinical trial (RCT), does not represent real-world conditions for treatment. RCTs are designed to maximize internal validity, and thus they represent optimal treatment conditions, including study participant compliance with treatment regimens, initial study participant work-ups and optimal follow-up in testing. To the extent that differences in real-world practice from RCT conditions might result in superior outcomes for patients treated with aflibercept (ie, the above comments regarding anatomical outcomes and dosing), it might be necessary to reconsider our findings. However, as also noted above, at current pricing differences between the medications, this is likely limited to a small subset of patients. Second, we have limited our simulation to 1 year after treatment was initiated. This was done because the SCORE2 trial, which was the source of our data, was limited to 1 year for the protocol treatment period. But this does mean that some downstream sequelae, such as steroid-induced cataract or decline in visual function, are not considered. However, it should be noted that there is no evidence in the SCORE2 results of a difference in visual function, so there is no reason to assume that this would be different between arms if we extended our modeling beyond the available evidence. Also, while the consequence of steroid use in the aflibercept arm could be different from that of the bevacizumab arm, it would be unlikely for the difference to be large enough among the few who receive steroids to offset the average cost difference among all those treated. Third, while there is some consensus concerning the threshold values used in assessing cost-effectiveness on a population basis in other countries, there is none in the US.18 So, while we used a standard of $150 000 to $200 000 for our base case and sensitivity analyses, it is possible that a decision maker using a more liberal standard for cost-effectiveness might come to a different conclusion. That said, we are aware of no commentator who argues that an ICUR in excess of $1 000 000 per QALY should be considered to represent a good use of societal resources, and in our base case here, we found that aflibercept was dominated. Fourth, we must note that while economic evaluation is conducted on a population basis, decisions for treatment of people living with CRVO or HRVO are made on an individual basis.

Conclusion

We conducted an economic evaluation of treatment with anti-VEGF medications in people treated with bevacizumab or aflibercept for macular edema due to CRVO or HRVO based on the results of the SCORE2 trial. We found that first-line treatment with bevacizumab with the option to change to aflibercept in those who did not respond to the first-line treatment dominated first-line treatment with aflibercept in most patients. This finding was due to the small VALS difference between the treatment arms compared with the large cost differential between simulated patients receiving aflibercept and bevacizumab. While there may be some subgroups of patients who will derive the most benefit from first-line treatment with aflibercept, it is likely a small fraction of those living with CRVO or HRVO. Future studies linking anatomical outcomes, such as retinal thickness, to patient-centered outcomes such as visual acuity or disease progression will assist in better understanding the optimal use of these therapies.

eMethods.

Group Information. SCORE2 Investigator Group

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Song P, Xu Y, Zha M, Zhang Y, Rudan I. Global epidemiology of retinal vein occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. J Glob Health. 2019;9(1):010427. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.010427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eylea (Aflibercept) injection receives FDA approval for the treatment of macular edema following retinal vein occlusion (RVO). News release. Regeneron. October 6, 2014. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/eylear-aflibercept-injection-receives-fda-approval-macular-edema

- 3.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ; CATT Research Group . Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897-1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-1359. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al. ; SCORE2 Investigator Group . Effect of bevacizumab vs aflibercept on visual acuity among patients with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: the SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2072-2087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Ophthalmology; The Retina Society; American Society of Retinal Specialists . Medicare Part B drug payment model could adversely impact treatment options for ophthalmology patients. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.asrs.org/content/documents/talkingpoints.partbdemoissuebrief.aao.asrs.retina_society.pdf

- 7.Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, et al. ; CHEERS 2022 ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force . Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMJ. 2022;376:e067975. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kymes SM. An introduction to decision analysis in the economic evaluation of the prevention and treatment of vision-related diseases. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(2):76-83. doi: 10.1080/09286580801939346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of Inspector General . Review of Medicare Part B claims for intravitreal injections of Eylea and Lucentis. Accessed October 13, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000383.asp

- 11.Kymes SM, Lee BS. Preference-based quality of life measures in people with visual impairment. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(8):809-816. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181337638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payakachat N, Summers KH, Pleil AM, et al. Predicting EQ-5D utility scores from the 25-item National Eye Institute Vision Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ 25) in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):801-813. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9499-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kymes SM, Vollman D. Recognizing the true cost of medical spending-an assessment of ranibizumab for retinal disorders. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(12):1432-1433. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutton DW, Stein JD, Glassman AR, Bressler NM, Jampol LM, Sun JK; DRCR Retina Network . Five-year cost-effectiveness of intravitreous ranibizumab therapy vs panretinal photocoagulation for treating proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(12):1424-1432. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.4284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin J, Gibbons A, Smiddy WE. Cost-utility of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(7):656-663. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennington B, Alshreef A, Flight L, et al. Cost effectiveness of ranibizumab vs aflibercept vs bevacizumab for the treatment of macular oedema due to central retinal vein occlusion: the LEAVO study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(8):913-927. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01026-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: past, present and future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127-137. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee BS, Kymes SM. Re: Brown et al.: cataract surgery cost utility revisited in 2012: a new economic paradigm. (Ophthalmology 2013;120:2367-76). Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):e69-e70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kymes SM. Is it time to move beyond the QALY in vision research? Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21(2):63-65. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2014.895843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

Group Information. SCORE2 Investigator Group

Data Sharing Statement